waterproofs firmly in place. By lunchtime they were excitedly sharing their experiences and crafted items. A choice of two soups was served from the campfire and then the delegates headed off for afternoon workshops with a rainbow greeting them on their way. On Saturday afternoon Kev and Bracken ran a workshop called ‘Cooking Using Dutch Ovens’, which then provided an outstanding evening meal of ground oven roasted pork or nut roast, haybox braised cabbage and new potatoes, followed by creamy rice pudding. Fully content, we then headed inside for the keynote talk from Naomi Allsworth - ‘Embracing the Wild: Thriving as a Woman in the Outdoor and Bushcraft Industry’. Inspirational, thought-provoking and moving were just some of the words that delegates used to describe Naomi’s presentation. We finished the evening with our non-monetary raffle of items crafted or collated by delegates - there were some amazing prizes.

After a very cold night for those who were camping, the delegates embarked on their final full-length workshops with the sun shining down on them. The lunch menu was Moroccanthemed and cooked with limited use of utensils - much of it on or over the embers - a final foodie-flourish from Bracken and Kev. To round off the event, we ran the popular express workshops, which were five lots of ten-minute workshops with delegates moving from base-to-base at the sound of a whistle. Afterwards we met together indoors one last time to thank everyone for their participation and enthusiasm, and we

Outdoor Learning Voice at Westminster

By Andy Robinson Outdoor Advisory Board (formally known

Where are we now?

as the Outdoor Council)

By 2023, the outdoor learning community in the UK had come a long way in achieving recognition amongst Members of Parliament (MPs) at Westminster. This was not the case only a few years prior, when dialogue between stakeholders in the outdoor learning community and those charged with developing policy, funding and legislation was quite limited. One of the key catalysts in driving change was restrictions imposed by Westminster during the Covid-19 pandemic. The subsequent formation of a UK All Party Parliamentary Group (APPG) demonstrated a desire by MPs to protect the outdoor learning sector from potential damage. Whilst MPs and representatives from the sector grappled with the implications of those Covid-19 restrictions, a longer-term vision on how the APPG could address broader sector issues once the threat from Covid-19 had passed began to take shape. By the end of 2023, the APPG had met a number of times, had attracted new members and developed a map to help MP’s identify outdoor learning providers in their constituency, quite a change from four years prior!

Changes at Westminster Changes to APPG rules in 2023 prompted a new way of maintaining dialogue with MPs. Maintaining an APPG with a minimum of 20 MPs is challenging, especially when MPs

were overwhelmed by the positive feedback. Everyone pulled together to take down the bases and cracked on with the clearing up.

The delegates left the site looking enthused and thoughtful (and slightly muddier than when they’d arrived…), ready to put into practice the new skills and knowledge that they’d acquired over the weekend.

Now for a few weeks off before starting to plan the autumn conference...p

describe themselves as ‘broadly supportive but not committed’. There is a significant difference for many MPs between the threats of 2020/2021 and aspirations of the outdoor learning sector in 2024, especially with the short-term focus of re-election. The outdoor learning sector is changing its forum from an APPG to a Member of Parliament Support Group (MPSG). This formal structure has lighter requirements than an APPG though does have less official recognition. It provides an engagement forum and a pathway to re-establish an APPG when the issue at stake leads to MPs moving from ‘broadly supportive’ to ‘committed’.

Plans

Check out the outdoor learning map by scanning the QR code or following this link:

qrco.de/MPSG-Outdoors

The immediate plan for the MPSG is to review the outcomes of a sector survey scheduled for mid-2024. The survey outcomes will be formed into a report supported by the MPSG and presented to the main parties at Westminster. Look out for the opportunity to participate in the survey which will lead the way for an annual ‘state of the nation’ report. Updates and resources are being developed on the IOL website for UK and Home Nation Government engagement (outdoor-learning. org/voice/government-engagement.html). If you wish to support the work of the IOL with engagement with UK and/or Home Nation Governments, please contact the IOL by email: governmentengagement@outdoor-learning.org.

Contact your MP

With this being a general election year, if you have not yet contacted your MP to encourage them to engage with outdoor learning, please do. Use the UK Outdoor Learning Digital Map 2023-24 (linked above) to find contact details of your local MP. If you would like to be added (this is free of charge) you just need to email institute@outdoor-learning.org p

5

SCANNING THE HORIZON

Photos by Sam Longhust. Photographer retains copyright.

Global Outdoor Learning Day takes place on the 21st of November every year and celebrates the powerful impact of the outdoors on education and personal development.

Organised by the Institute for Outdoor Learning, Global Outdoor Learning Day brings together educators, organisations, and individuals globally to acknowledge and promote the benefits of outdoor learning. It promotes the belief that learning in natural environments contributes significantly to physical wellbeing, mental health, and a deeper understanding of the world around us.

Global Outdoor Learning Day is an opportunity to showcase diverse outdoor learning activities, share best practices, and inspire a love for the natural world in learners of all ages. #Globaloutdoorlearningday

Global Outdoor Learning Day

21.11.24

7

SCANNING THE HORIZON

PPE Inspection Courses for

Adventure Activities

Including ‘Competent Person’

Develop knowledge, learn up-to-date inspection, maintenance techniques and legislation

Covers equipment for mountaineering, climbing, caving and water activities.

Gain an understanding of the effects of wear and damage on lifetime, strength, function and continued use.

Counts towards CPD points for AMI & MTA members.

Lyon Equipment Limited

www.lyon.co.uk

info@lyon.co.uk

+44 (0) 15396 24040

Web:

Email:

Tel:

9629-Lyon W&R ads v4.indd 2 11/08/2022 14:27

2. Using the National Outdoor Learning Award (NOLA) to work on character education concepts and taking responsibility for self and others (ensuring a strong, healthy and just society).

• For example, on a low-ropes course a group might be working specifically on the NOLA competency of “I helped with kind actions”. During the activity, the focus may be on their group as a micro unit of society. They may only be seeing the impact of their behaviour in a small and local way, but the concept of being responsible for another person can help to make the wider link to the ways in which our actions impact others in other parts of the world.

• Questions to pose: How does it make you feel when others help you with that problem? Are you able to do things that you couldn’t have achieved alone?

“ What impact can you have on wider society?

”

3. Discussing the impact that leaving rubbish has when you stop for a snack or participating in activities to improve the local environment such as a park litter-pick or two-minute beach clean (living within environmental limits).

• Whenever I take a group out for a day on Dartmoor we inevitably find litter, whether it is our own or the result of other land users. The simple act of picking it up and taking it home with me is noticed by the group, even if I do not make it a particular teaching moment. As we are walking along, it generates conversations and natural moments of reflection on the places familiar to the participants and how they interact with them.

• Questions to pose: Do you see litter in your local area or special places? Do you see people caring for those places? How does it make you feel to see them treated in a particular way?

“ How would you like people to behave in those places?

”

Conclusions

When provided with both knowledge and experience of the natural world “people will care about it, want to know more and want to do something about it” (5). As outdoor educators we are the front-line of reaching the heart of the issue and facilitating a more sustainable future. It is my intention that each group I interact with is given the opportunity to connect with the natural environment and their role and responsibilities in it. To take a moment to stop and appreciate it in some way, or perhaps even contribute to improving it. For me, that is more than just moving through a space, or using it for an activity. It is my hope that when they leave that environment, they will have a greater respect for it, what makes it unique, the animals, insects, plants or birds that call it their home, and how it feels to be there. Perhaps they have had an opportunity to consider their choices around governance, finances and economy, or where they fit into society.

One of the locations I love to use with groups is an abandoned medieval village. In it we get to explore how people have lived in the past and often play a game role-playing trade and daily life in the village. What is fascinating to watch is the way in which the participants are often less interested in the fairness of those trades and are out for whatever they can get, until we review the activity. Suddenly, with some space to reflect, they realise how unsustainable it would be trying to cheat and rip off their neighbours while living side by side over the long term. They start to realise that things they might get away with once would hurt them over the course of time when no-one trusts or will interact with them. And while some still walk back home bragging about the time they managed to trade a whole pig for six jugs of milk, I usually also overhear brilliant conversations about the trades that were fair, the ways in which they drew the imagined community together planning weddings or facing hardships, and how much they felt a sense of pride and ownership of the house that they had been allocated. Walking out of the village, I no longer need to remind even the most enthusiastic participants to use the doorways or avoid climbing on the walls because they now see it as a ‘place’ not just a collection of stones. If I can help someone to care, even just a little, about the space that they have been in, then I believe that can make a difference to their values and, thus, their current and future behaviour p

References

1. Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, 2005. Securing the Future: Delivering UK sustainable development strategy.

2. Orr, D., 1992. Ecological Literacy: Education and the Transition to a Postmodern World. New York: State University of New York Press.

3. Education International, 2017. Sustainable Development Goals. [Online] Available at: https://ei-ie.org/en/detail_page/4918/ sustainable-development-goals [Accessed January 2018].

4. Nicol, R., 2014. Fostering environmental action through outdoor education. Educational Action Research, 22(1), pp. 39-56.

5. John Muir Trust, 2015. John Muir Award Information Handbook, Pitlochry: John Muir Trust.

Some images have been provided with permissions by the author. Author retains copyright.

12

SUSTAINABLE FUTURES

TAKING AWAY TECH TAKING AWAY TECH

Dr Jack Reed discusses the latest guidance from the UK Government on banning phones in English schools and what impact this might have for outdoor education

Author profile

Dr Jack Reed is a Postdoctoral Researcher on the ESRC-funded Nature Recovery and Regional Development (NaRReD) project at the University of Exeter. His previous research has focussed on young people’s constructions of nature through networked spaces in residential outdoor education contexts.

The place and use of young people’s mobile technologies and social media in outdoor education environments has seen increased interest over recent years. In February 2024, a new special issue in the Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning was published on the topic (1), and we are beginning to see consideration placed on the impacts of social media, the metaverse and artificial intelligence on outdoor education globally.

Looking at education more broadly for a moment, the UK government has just published guidance for schools in England on banning mobile phones. The guidance states “that all schools should prohibit the use of mobile phones throughout the school day – not only during lessons but break and lunchtimes as well” (2). This means that schools in England will be phone-free environments. Interestingly, the guidance also makes mention of residential trips, stating that schools “should determine how they wish to manage the use of mobile phones by pupils on residential trips or trips outside of the normal school day. Schools should ensure that pupils’ educational experience on a school trip is not disrupted by the presence of mobile phones and should consider prohibiting or restricting their use” (2). Guidance essentially applies the in-school phone-banning guidance to away-from-school educational visits, including outdoor education.

In response to this guidance, I have just published a critical article with colleagues that draws on the United Nations (UN) Convention on the Rights of the Child, and specifically on young people’s rights in relation to the digital environment. The UN state that young people have the right to access information through technology and “that the exercise of that right is restricted only when it is provided by law” (3). Given the UK government’s stance on banning phones in schools does not constitute legally binding statutory guidance, this raises important questions for all education providers considering banning young people’s phones. In particular, does the removal of a young person’s phone breach their protected human rights as stipulated by the UN?

The stance in our paper encourages caution on the part of outdoor educators, educators more broadly and policy makers, especially in relation to young people’s right to access digital information and their right to culture, leisure, and play. These factors are clearly outlined in UN human rights documentation and suggest that all those involved in decision making around young people’s mobile phones consider how banning phones could breach young people’s protected human rights. This could be particularly relevant in any outdoor education context where removing young people’s phones is considered either standard or desirable practice. Our full article on this topic is freely available to read (4) p

References

1. Reed, J., van Kraalingen, I., & Hills, D. (2024). Special issue: Digital technology and networked spaces in outdoor learning. Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning, 24(1), 1-6.

2. Department for Education. (2024). Mobile phones in schools: How schools can prohibit the use of mobile phones throughout the school day.

3. United Nations. (2021). General Comment No. 25 (2021) on Children’s Rights in Relation to the Digital Environment.

4. Reed, J., & Dunn, C. (2024). Postdigital young people’s rights: A critical perspective on the UK Government’s guidance to ban phones in England’s schools. Postdigital Science and Education, 1-10.

FOREST SCHOOL FORWARD

Author profile

Dr Sara Knight worked for over twenty years as a teacher in early years classes and with children with particular needs. She then moved into further and higher education establishments, retiring as a Course Group Leader from Anglia Ruskin University. She trained as a Forest School leader and trainer starting in 1997, and was the first Deputy Chair of the Forest School Association (FSA). She has authored research papers, books and chapters relating to Forest School and is still research-active. She is an ambassador for the FSA and on the academic board for the FSA Research Symposium 2024.

Horizons Magazine has published two articles by Jon Cree and Mel McCree (1) in the past that cover the origins of Forest School in the UK and its development up to the formation of the Forest School Association (FSA) in 2012. In 2022, I was asked to follow this up by pulling together a display covering the years 2012 to 2022 in time for the 2022 Forest School Association National Conference. Being aware of the traps lying in wait for anyone who thinks that they know the whole story, I chose to leave spaces in the display and invite attendees to add their thoughts and memories to the timeline. Ahead of the first Forest School Research Symposium, to be held at the University of Liverpool in June 2024, I am sharing what we gathered together on and after the 2022 conference.

The story so far

The Forest School National Governing Body produced an online survey in 2010 (2), to which there were 928 respondents, of which 79% were female and 21% were male. Their distribution across the UK were as follows:

England West Midlands: 24%, East of England: 15%, Wales 15%, South-East England 13%, South-West England 9%, Scotland 9%, North-West England 7%, England East Midlands 5%, North-East England 1%, London 1%, Yorkshire and Humberside 1%, Northern Ireland 0%, Outside the UK 0%.

This sample only captured a partial view, so it should be seen as representative of the Forest School National Governing Body at that time rather than of the entire Forest School movement. However, it does give a sense of how far Forest School had developed by this stage. Of the respondents, 2% were trained trainers, 62% had a level 3 qualification and 26% were unqualified.

As of February 2024, the FSA has a membership of almost 2000. With Forest School in England, Scotland and Wales receiving support from their regional assemblies (3), each nation has moved in slightly different directions, and currently most FSA members are English. Northern Ireland has not developed as quickly as England nor, indeed, as fast as the Republic of Ireland which has its own thriving Forest School Association. There are 17 regional FSA groups active in different ways across England. There have been submissions to the FSA 2024 Research Symposium in Liverpool (as mentioned above) from across the UK, but also from the Republic of Ireland, France, Italy, Spain, Israel, the United Arab Emirates, the USA, Australia, and Singapore. In addition, FSA trainers have run courses in South Korea, China, Canada and Turkey. What follows are some of the steps in the journey of the last 10 years.

14

A potted history – growing interest in the Forest School Association

The following notes are drawn from the information collected in 2022, plus some more recent developments. I am therefore confining myself to the FSA as the professional body for Forest School, rather than the wider Forest School picture. There will have been other events that have not been recorded here, but these notes give a sense of the growing interest in Forest School.

In 2013, the 2nd FSA National Conference was held at the Derwent Hill Outdoor Education and Training Centre in Keswick. Here, the FSA website was also launched, with extensive ‘knowledge’ documents added in the members sections. The Open College Network (OCN) Forest School training at Levels 1-3 were accepted as national awards on the English Qualifications Framework. In Wales, training was and is awarded through Agored. Six academic papers and two books about Forest School were published in the UK in 2012/13. There was also an advice leaflet from Ofsted, ‘Using a Forest Environment for Preschool Children’, in 2012 (4).

Between 2014 and 2023, the FSA held a conference almost every year in venues such as the Essex Outdoors Centre in Danbury, Condover Hall in Shropshire, Bradmoor Woods, Norfolk and High Ashurst Outdoor Education Centre, Surrey. There were also regional Forest School conferences in Devon, Cornwall, Shropshire and Cambridgeshire. The Forest School Trainers’ Network was established, as was a searchable database of level 3 qualified Forest School leaders on the FSA website. Jon Cree and Sara Knight visited the South Korean Forest Kindergarten Association. Sara Knight, followed by Huathe, delivered training and speaking engagements in China. Jon Cree helped establish the Canadian Forest School Association. The FSA Recognised Forest School Provider scheme opened in February 2017, and the FSA set up a forum for awarding organisations to ensure that all regulated Forest School qualifications are aligned to national professional standards (5).

15

How has the plan been received by disabled people?

As with any government initiative, there has been a mixed response from the people the plan is aimed to serve. Whilst many people feel that ‘some progress is better than none’, there are others that believe “the actions set out in the plan are ‘weak’, and too many of the proposed ‘short-term’ actions are not short-term at all – introducing reviews or proposals for 2025, after the general election where no action can be guaranteed” (1). Furthermore, whilst the UK Government suggests there has been significant engagement with disabled people, this has been seen as superficial. There remains the concern that disability initiatives continue to be driven by non-disabled people, which sits uncomfortably with many in the disabled community.

The plan has also been criticised due to a lack of commitment and accountability. Many of the actions are unmeasurable, there is no target date for completion and there are no named individuals responsible for achieving them. The UK Government also uses phrases such as ‘we will explore’ or ‘we will work to’ which leaves little confidence that action will be taken. Only time will tell whether this will be the case.

So, what can we take from it?

Despite opinion that the plan is perhaps falling short of what is needed, here are the things I believe the outdoor education sector can take from the new DAP:

Ensuring good representation

As the government is working to support disabled people into public office, the outdoor sector too should ensure there is adequate disability representation across the various levels of organisations and national governing bodies. Despite criticism to the contrary, the government say they are engaging with disabled people to develop the plan and will look to include them as part of their ongoing developments. Outdoor providers should be looking to do the same by having staff, volunteers, governors or advisers with lived experience of disability, which is important when trying to create a more inclusive provision. The commonly used phrase ‘nothing about me, without me’ comes to mind - this articulates the idea that disabled people should be included in the decision-making process when it comes to inclusive practices. Otherwise, how do we know we’re getting it right?

Ensuring services are more accessible

Disabled people were more likely to report finding access to services in person difficult compared with non-disabled people (51.5% compared with 25.2%)(2) ”

In recent years we have seen a drive towards ensuring services are more accessible to disabled people, and this is reflected in the DAP. As ‘retrofitting’ is incredibly challenging and costly, considering accessibility in any new developments would be sensible, if not essential. Having said this, anything outdoor providers can do to improve access to existing facilities would be welcomed. Access does not simply apply to buildings and grounds. UK Government are committing to making their publications and communications more accessible as well as providing more resources for disabled people and their families. Outdoor providers could take a lead from this and consider all areas of the ‘customer journey’, from first contact on a website or through social media, to improved communications and resources whilst accessing the services onsite. Expectations around this, quite rightly, are increasing, so this is something we should all be working to improve.

18

“ DISABILITY ACTION PLAN

MY JOURNEY TO TAKING THERAPY OUTDOORS

Author profile

Joshua Anderson is currently working to become an Adventure Therapist. Joshua brings his range of experience and qualifications from leading people outdoors in the UK and overseas and hopes to combine this with his love for seeing people change and grow in the therapeutic space.

The long journey to taking therapy outdoors

Whatever term you use, adventure therapy, outdoor based coaching or occupational therapy in the woods, outdoor therapeutic practices are complex in both form and function. A lot of other people have written about outdoor therapeutic practices in publications, in books and at conferences, and there are many definitions to choose from. This article is simply my journey into the field (namely adventure therapy) and how I am still scratching the surface in my understanding of how it works.

From what I can tell, there is no direct pathway into the field of outdoor therapeutic practice and it remains largely unregulated as a field. The way I understand it, those wanting to work in the field will need to combine the therapeutic discipline with the outdoor discipline (or possibly multiple outdoor disciplines), for example: a walking group leader will also need to be a qualified psychotherapist to take their clients on therapeutic walks in the hills.

My outdoor pathway

The outdoors holds a special place in my heart. For me, I came to enjoy outdoor activities in my teens through an outdoor education class in school; I undertook the Duke of Edinburgh award and participated in the air cadets. These activities all taught me what I could be capable of and that, with hard work, I could make my own luck. Alongside these activities, I was studying chemistry, sport, media studies and drama. At that time, media studies and drama was the combination of subjects that I was hoping to make a career out of through further study. With decisions looming over me as I was about to leave sixth form, I decided after much debate that I had fallen out of love with the subjects that I wanted to do, so I needed to re-examine what I was good at. So, I decided to take a dive back into what I loved the most –the outdoors.

I got into university and studied a degree in outdoor leadership and management, which gave me foundational skills and experience in the sector. I knew I needed to gain experience from the people around me and take whatever opportunities I could in order to advance my skills further. One of the freelance instructors from my degree course reshaped how I thought about people and showed me the deeper impact that the outdoors could have psychologically and what my role could be as part of that process. In the following years, I continued to learn from this instructor and took my experience into centre work and freelancing. It was during this work that I began to realise I didn’t want an outdoor instructor career where I would only ever see an individual once or engage with them on a taster activity. That’s not to say that a career of this kind wouldn’t be enriching or impactful, but I knew that I wanted to engage with individuals who would regularly want guiding to change their life and their circumstance over a long period of time. Subsequently, I have been able to achieve this longer-term engagement through leading expeditions with schools in both the UK and Dubai. These expeditions involve a month away helping communities of people as well as an adventure week. This is where I felt a rush - seeing change in students within an environment that was far removed from what they were used to.

20

My therapeutic pathway

Covid happened and, like for many, my life was changed. My trajectory generally remained the same, however, and many new doors opened themselves to me. During this time, I was introduced to several people who significantly influenced my journey and showed me the practical and theoretical considerations that aided me on my pathway to becoming an adventure therapist – for example, how to maintain the client’s dignity, refute coercive practices and know what moments to step back and let the individual be present in the outdoors. I realised that this combination of outdoor professional and therapist was what I wanted, so I looked at how I could combine the two disciplines. There were no clear pathways and still there are divided opinions amongst professionals as to what you need to do to call yourself an adventure therapist, but what was clear to me was that I had no therapeutic training. I contacted several people, as many as I could find, practitioners across the globe, psychotherapists that might let me shadow their sessions, universities and organisations to try to figure out a pathway and how I could become qualified.

To get the therapeutic training I was missing, I undertook a psychotherapy and counselling intensive certificate, which focused on being integrative with the various models and theories. I found the theories and history of many of the founders of the therapeutic models to be incredibly interesting such as Carl Jung’s thoughts on the collective unconscious as well as Irvin Yalom’s four existential givens. However, it is all well and good to grasp the theoretical side of theories and models, but seeing what a therapeutic experience can look like in practical terms is the key ingredient that I urge all aspiring practitioners to engage with before they start working with clients. In the end, theory cannot be without practice and vice versa, however seeing how to combine the two in practice is powerful. I also came into contact with the IOL’s therapeutic outdoor group which contains many like-minded people who are wanting to open up the conversation around outdoor therapy and to create a culture of sharing ideas.

Where am I now?

In order to apply the skills I have been developing over the last number of years, I have been working in a range of occupations and different sectors such as the care industry, education as a teaching assistant in alternative provision, as a behavioural support officer in a college and a listening volunteer for Samaritans. All these different positions are working in capacities that require therapeutic skills, care, compassion, hope and empathy that can be learned through training, experience and being curious and open around people.

As I continue on my journey towards adventure therapy, my pathway has taken a few twists and turns. Since completing my psychotherapy and counselling intensive certificate, I have gone on to complete a master’s degree in psychology which will allow me to undertake a doctorate in counselling psychology. This will enable me to open my own private practice and fully combine my outdoor and psychology background. The benefit of being able to fully utilise my experience within a private practice is that I can have a greater understanding of how to operate in different environments safely while being guided by the ethical guidelines of professional bodies.

All in all, I believe that you can make your own pathway, there is no right and wrong as long as you are maintaining ethical standards and the necessary accreditations with the professional bodies that you operate under. As long as you are transparent and reflexive around what you can and cannot do, then embedding therapeutic practices in the outdoors is possible for anyone p

21

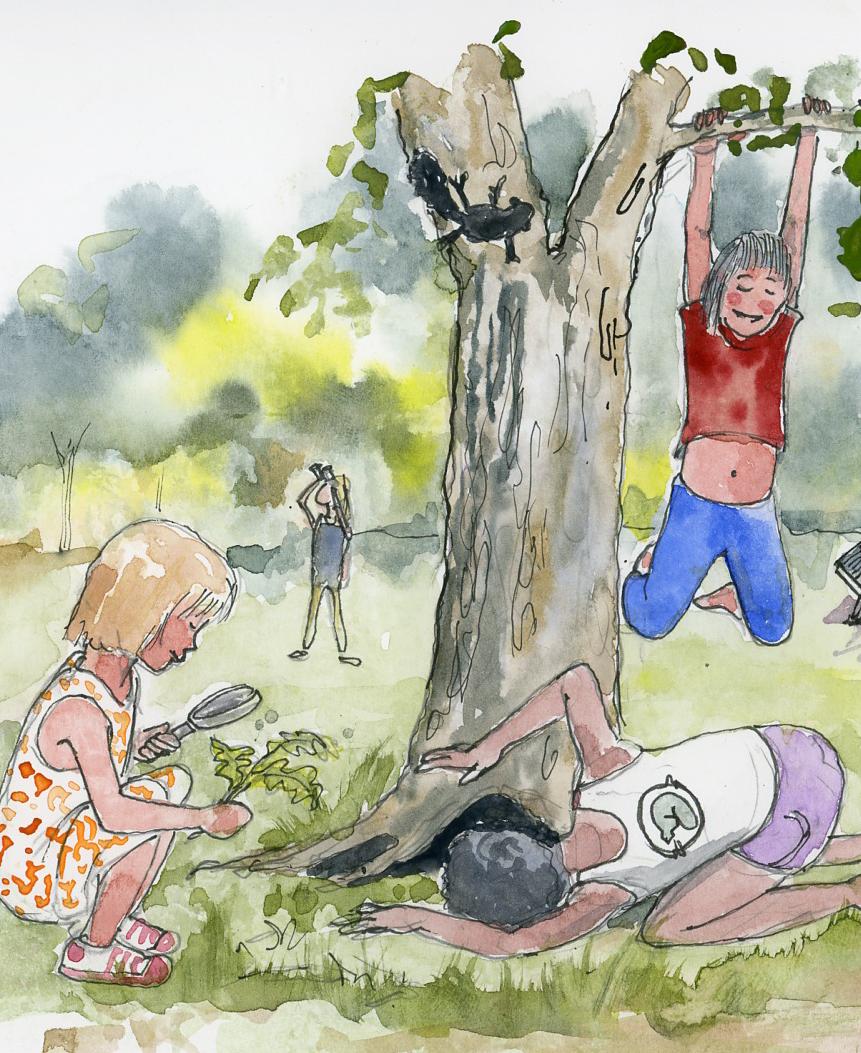

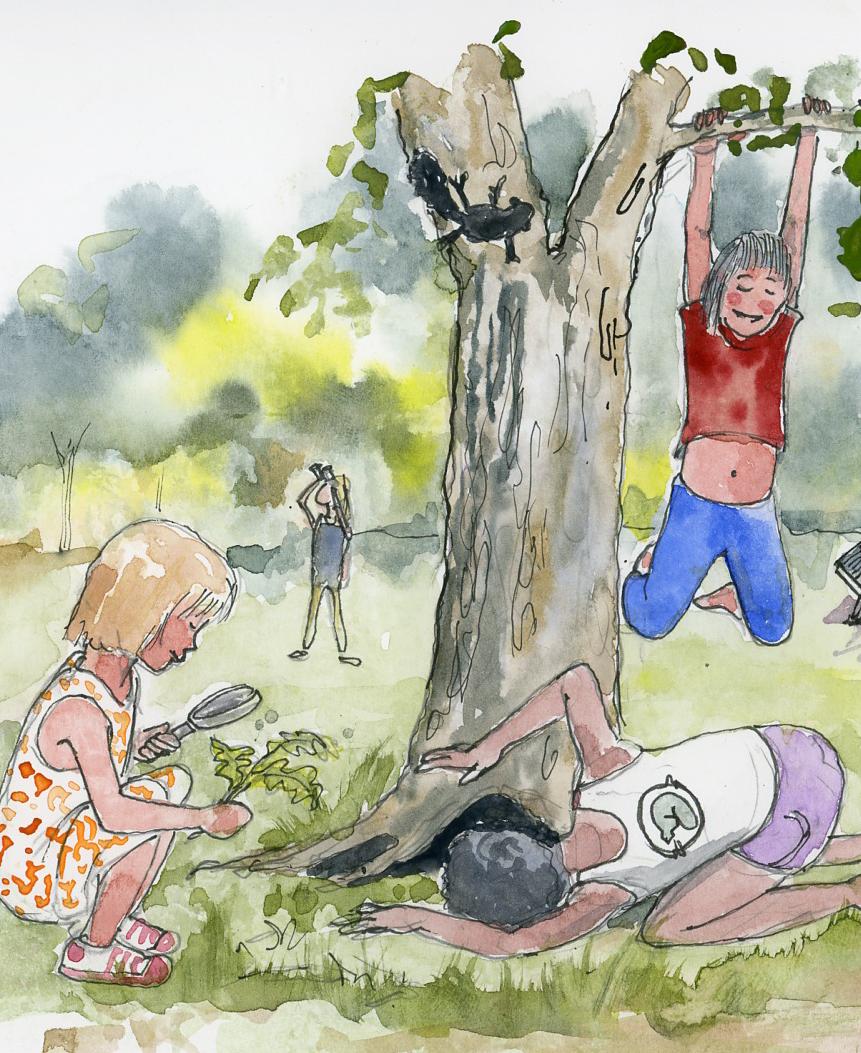

WOODLAND WELLNESS CLIMBING TREES

Tim Chamberlain continues his series on Woodland Wellness by taking a closer look at climbing trees. In this article, Tim considers how climbing trees might make us better thinkers and might develop better risk evaluation skills in young people as they develop

Author profile

Tim Chamberlain has worked with children, students and scientists for 15 years. He is chief instructor for Canopy Access with Operation Wallacea using rigging and risk management skills gained as an outdoor instructor and tree climbing expert. Qualified as a zoologist and sculptor he holds industry qualifications relating to safety, rope access, advanced canopy access techniques and rescue. As an active volunteer he is a Verifier for the Woodland Trust’s Ancient Tree Inventory and also works on rare raptors in partnership with Forestry England as a member of the Dorset Raptor Study Group.

PART 2

Being in and around nature helps us to become better thinkers. As a child I grew up playing in and exploring the local woods, scrambling up the nearby hill and cycling to the riverside. From a young age my friends and I wanted to explore trees using our hands, feet and bodies, feeling the importance of getting up close and personal with trees and connecting with nature. Now, as parents and guardians, we sometimes overlook our childhood learning as we worry about our children’s safety as they climb, clamber and do ‘dangerous’ things in outdoor environments. And yet it turns out that overprotecting children has risks too. In this article I will examine the importance of risky play in childhood and how exposure to ‘risk’ helps set us up for life by developing our ability to assess situations. I’ll then look at how tree climbing provides risky play and a learning zone for a riskaware approach to the outdoors. Finally, I will consider what extra things we can do to keep safe while we go adventuring in trees.

The importance of risky play in childhood

We face risk daily throughout our lives and how we manage it is often dictated by our experience of risk, as it can help us understand what to do in specific situations (1). Risk-based learning in children is instinctive and children’s desire for “challenging play” naturally involves aspects of risk-taking in the outdoors (2). Risk is often defined as the possibility or threat of something bad happening. Yet, children tend to engage in outdoor play in a way that helps them learn to identify, assess and judge the risks involved. This can occur in a guided and assisted environment, for example in a Forest School setting where children on a tree climbing activity are encouraged and supervised by specially trained teachers to clamber no higher than a previously risk-assessed level which is delineated with ribbon or tape.

“Risk is a fundamental part of life

The value of such risky play is an important factor for childhood development of life skills and enhances wellbeing (4). Sometimes called ‘adventurous play’ to remove the stigma of perceived threat (5), such play presents novel situations through which children can explore and discover their own capabilities and limits, empowering them to “make informed decisions about the risks that they take” (6).

Maybe surprisingly, it is not all about success; in an article titled “why risk-taking is essential for child development” (3) child clinical psychologist Dr Tali Shenfield recognised the importance of failure in facilitating learning from which children can acquire long-lasting skills. Learned moments such as a slip on a wet branch or a moment of feeling scared offers children the opportunity to assess situations carefully for risk. The process of learning how to assess risk is a necessary life skill and can help to avoid poor risk judgement further down the line. Evidence for this has been observed, with younger cohorts less exposed to these risks now less able to calculate and manage physical risks in the workplace (7).

How tree climbing provides risky play

Tree climbing is an activity that brings children closer to nature and ten years of guiding children up into the canopy has shown me how it can encourage a deeper appreciation for the natural world around us. For me, tree climbing is all about connecting with nature and is the perfect antidote to our increasingly digital world. Being in nature is now properly recognised as beneficial for our mental health (8) and just “being in a tree can calm kids down” (6).

23

(3)

”

As well as offering higher rewards, tree climbing can involve bigger risks than other outdoor play. It is through a better understanding of risk and risk control measures that it is possible to reduce or minimise the chances of serious harm and tree climbing teaches these very skills with young people learning to take measured and calculated risks. As one of the Forest School Association’s higher risk activities, tree climbing remains very much on the curriculum as it is “one of the most memorable and rewarding parts of the experience” (6). Tree climbing can, of course, seem daunting with all kinds of hazards such as height, slippery branches, dead limbs and rocky ground. The process of tree climbing necessarily involves a consideration of these things all at once with simultaneous planes of learning that include “testing muscles and strength, improving hand-eye coordination, building confidence, assessing and taking risks, facing fears, learning about gravity (and) problem solving...” (9).

In a recent survey, parents spoke of children learning “perseverance, sharing, empowerment and self-awareness” from tree climbing (10) and additional benefits included building self-esteem, problem solving and learning patience - clearly trees stimulate our senses (3, 4). A large study in the U.S. reported that parents considered that the benefits of tree climbing outweigh the risks (98.04% of 1403 people) (4). However, it is important to note that minor injuries can occur when climbing trees and most often these are small scrapes, bumps or bruises or sometimes small fractures. More serious incidents and fatalities are incredibly rare with data showing its relative safety as an activity for children (4).

UK tree climbing companies offer a supervised tree climbing experience where young children can climb taller trees with more complex structures. These trees are sometimes hundreds of years old and notable within the landscape. This offers a special connection with nature as they experience the view from near the top of the canopy and interact with different kinds of nature such as birds and insects. It also uses a different skillset and lets children and young people further develop their risk assessment skills as they need to listen to safety instructions, learn to use rope systems and navigate the trees in a new way. In this way, risky play and risk evaluation skills can be further developed, sometimes allowing kids (and adults too!) to carry on climbing beyond the age that they might have stopped climbing trees in the park as their social interactions move away from physical play.

Tips for tree climbing safely

Do a risk assessment: This is basically a consideration of what potential hazards there are and what you can reasonably do to prevent harm to people. Thoroughly looking around for things is half the battle and it’s a useful skill and a good habit to get into as some things, such as spotting a wild honeybee nest, can take a bit of noticing. For businesses, risk assessments will protect those in your care as well as your workers, your business, and help you to comply with law. Check out the Health & Safety Executive’s guide to managing risks and risk assessment at work (11) and the Royal Society for the Prevention of Accidents’ what is a risk assessment? (12).

Communication: Always ensure good communication to make sure the child understands you and can make sense of the risks associated with the activity. You can do this by talking them through an activity or, even better, helping them to talk you through it. You can do this both during the activity and when you get home to allow a deeper understanding of the potential risks. Do a simple appraisal of which branches are safe and why as this will help the child to understand more about the importance of tree health - and don’t forget the species of tree as some can be more brittle than others, especially any dead bits! Discuss how other factors such as wet weather can change the risks associated with moving in the trees, for example, making branches more hazardous, especially smooth barked trees like beech.

Techniques: Look at good ways of moving, e.g. always keeping three of your limbs on the tree for better control and stability. Stand back to give the child space to concentrate and focus on their climbing whilst you observe any potential hazards. Dr Sasha Petrova (13) advises approaching the activity initially at lower levels of difficulty and working up to a challenge in stages, ensuring children are experiencing risks that are best suited to their age and personal ability. You could, for example, begin by assisting a child to explore familiar playground climbing frames before moving on to low-lying tree limbs. As mentioned above, climb no higher than a previously risk-assessed level, delineated with ribbon or tape. The risk of falling can be further minimised through the selection of specific, easy to navigate trees (i.e. they have an interesting structure whilst they also have lots of low limbs and plenty of handholds) and in areas with relatively hazard-free, and soft, landing zones (6). Younger children usually require additional adult supervision, whereas older ones often need fewer restrictions.

24

WOODLAND WELLNESS

Conclusion

Tree climbing really is a fantastic activity and these vertical adventures encourage exploration of the natural world in which young people learn to take measured and calculated risks where “the benefits of tree climbing can make the risks worthwhile” (2). Far from seeking to encourage reckless behaviour, it is the overprotection of children and the attempted removal of all risk which “ultimately leaves them in harm’s way” (7). Therefore, by assessing the risks and looking after our children’s safety it means that the young climber can fully concentrate on their immersive experience. This leads to great benefits that we can observe during a morning or even a single hour. In that short time a participant can break through pre-conceived ideas of their own abilities to gain a real feeling of achievement and boost in confidence, even overcoming a fear of heights or discovering joy in the sharing of an adventure. Importantly, they can also develop a lifelong risk-analysis skillset to keep them safe! Check out the first part of this Woodlands Wellness series in Horizons #104 for more benefits of being in woodland (14) p

Images 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 supplied by the author with thanks to L Kinsman-Chauvet, G Lundy & K Kershaw. Author retains copyright.

All tree climbing activities are undertaken at the participant’s own risk.

References

1. Newman, L. & Higginbottom, K. 2017. Toddler risky play: how we got up the research project and what we found.

28/8/2017. EduResearch Matters. https://blog.aare.edu.au/ toddler-risky-play-how-we-got-up-the-research-project-and-what-we-found/

2. Little, H. (2010). Finding the balance: early childhood practitioners’ views on risk, challenge and safety in outdoor play settings. Australian Association for Research in Education Conference (AARE) 2010 Conference

3. Shenfield, Dr. T. 2020. Why Risk-Taking Is Essential For Child Development, Advanced Psycology, December 23, 2020. https://www.psy-ed.com/wpblog/ risk-taking-children

4. Gull, C., Goldstein, S. L. & Rosengarten T. 2017. Benefits and Risks of Tree Climbing on Child Development and Resiliency. International Journal of Early Childhood Environmental Education. v5 n2 p10-29 Spr 2018.

5. FitzGibbon, L. & Dodd, H. 2023. The State of Play in Scotland. Play Scotland. 6. Davies, G. 2017. Climbing Trees (and rocks). Forest School Association. https:// forestschoolassociation.org/climbing-trees-and-rocks/

7. Anderson, G (2018) Climb a tree and give three cheers for skinned knees!, Woodland Trust Scotland. Blog 01 Aug 2018. Anderson, G. 2018.

8. Mental Health Foundation. 2021. Nature. How connecting with nature benefits our mental health.

9. Holmes, L. 2016. Wild Kids Rock – 11 Reasons to Get Outdoors Into Nature NOW, Kids of the Wild. blog: October 19, 2016 https://kidsofthewild.co.uk/2016/10/19/ why-nature-benefits-scientific-evidence/

10. Newman, K. & Leggett, N. 2019. Five ways parents can help their kids take risks – and why it’s good for them. The Conversation website: Published November 21. https://theconversation.com/ five-ways-parents-can-help-their-kids-take-risks-and-why-its-good-for-them-120576 11. HSE 2024: Managing risks and risk assessment at work. Health & Safety Executive.

12. The Royal Society for the Prevention of Accidents https://www.rospa.com/ workplace-health-and-safety/what-is-a-risk-assessment

13. Petrova, S. 2019. Should I let my kid climb trees? We asked five experts. The Conversation. Oct 27. https://theconversation.com/ should-i-let-my-kid-climb-trees-we-asked-five-experts-125871

14. Chamberlain, T. 2024. Woodlands Wellness. HORIZONS The Outdoor Learning Magazine. Issue 104: WINTER pp20-22

25

WOODLAND WELLNESS

WHATEVER HAPPENED STREETWORK?

Geoff worked as a teacher, a teacher trainer and for the Peak National Park before developing Wigan Council’s two residential outdoor centres in the Lake District. His particular interests are in the links and shared values between outdoor, environmental and global education.

Over 84% of the UK’s population lives in urban areas, including inner cities, suburbs and towns. During the 21st century there have been considerable changes to the physical, social and economic fabric of our cities. Some urban areas have suffered from decaying old industrial zones with poor housing and few leisure and community facilities, whilst other parts of the city have been upgraded through commercial investment in retail outlets, office blocks, expensive housing and a range of amenities. Our cities have many issues related to traffic, air pollution, waste management, poverty and homelessness. They are also places with rich histories, distinctive architecture and cultural diversity. Do we, in outdoor learning, spend enough time engaging with city life or are we still more concerned with getting young people away from their city roots and into the countryside? This article considers one aspect of outdoor learning, ‘streetwork’, as a means of exploring and investigating local urban environments.

Streetwork

Whereas fieldwork, related to the school curriculum, was a well-established form of outdoor learning from as early as the 1940s there was no equivalent exploration of urban environments. The breakthrough came in the 1970s from an unusual source, an educational service set up by the Town and Country Planning Association (TCPA) following the government’s Skeffington Report, “People and Planning”, that recommended that planning be taught in schools. Colin Ward and Anthony Fyson, coming from architecture and planning backgrounds, were two leading lights of the TCPA. They promoted urban studies in schools and colleges through the Bulletin of Environmental Education and coined the term “streetwork” to make it distinct from rural-based fieldwork. Unlike fieldwork where the emphasis was on observation,

“

“If you learn to know your so doing learn to love it more, understand and appreciate sympathise with their problems"

recording and analysis, streetwork adopted an issuebased approach. Students were encouraged to view their neighbourhoods with a critical eye, identifying local issues that affected their lives and strive to take action.

A further development was the setting up of urban study centres to provide information, resources and support for teachers on aspects of urban life, such as transport, housing, industry and recreation. The Council for Urban Studies Centres was established in 1973 and there were over thirty, mainly nonresidential, centres by the early 1980s. A common method of exploring the urban environment was the town trail - a directed walk with statistics and illustrations, which introduced young people to issues and raised questions on how decisions were made that influenced life in the city. The emphasis throughout this form of outdoor learning in urban areas was on critical inquiry to encourage participation and to sow the seeds for active citizenship.

At around this time I was teaching geography and outdoor activities at a secondary modern school in Ellesmere Port. The school had adopted an innovative project called ‘Geography for the Young School Leaver’, which allowed teachers to develop their own content and methods. Together with a colleague, I took groups out into the local environment to explore issues such as urban decay, facilities for play and recreation, public transport and water quality. We used kayaks and narrow boats on the local canal to explore the little viewed parts of the town. We photographed buildings and industries related to former times and were surprised by the variety of wildlife close to oil refineries, a car factory and a ship canal.

There is little evidence of this pioneering urban-based outdoor education today. The education world changed dramatically

26

Geoff Cooper takes a look at an innovative

Author profile

HAPPENED TO STREETWORK?

innovative approach to urban outdoor learning

your own place well, and in more, it will help you to appreciate other places, and to problems" (Patrick

Geddes)

”

with the introduction of the National Curriculum in 1988, as it seemed to constrain educational initiatives and introduced a culture of attainment targets and graded tests. In addition, the Local Management of Schools (LMS) took finance and influence away from local authorities. This led to a narrowing of opportunities to support outdoor provision as part of formal education. Urban study centres gradually disappeared and with them these issue-based approaches to outdoor learning.

Forward to the 21st Century

There are still examples of outdoor studies taking place in urban areas from schools. Most of these, however, are related to using and exploring green spaces in our towns and cities. Many Forest School groups operate from urban schools using local parks and patches of woodland. City farms attract nearby primary schools and have developed educational programmes linked to the school curriculum. But these facilities and resources tend to be deliberately divorced from the built environment. They offer opportunities for the many educational and health benefits of experiencing more natural spaces. They may lead to discussions on such topics as recycling, pollution and biodiversity, but the methodology is unlikely to be issue-based employment of critical thinking.

For the last twenty years place-based education has been a growing area of interest in outdoor learning. Wattchow and Brown present strong arguments for outdoor education to move away from using the environment as an arena for personal and group challenges to a more relevant consideration of the rich cultural and natural elements of our local places and those we journey through (1). Mannion and Lynch argue the importance of place-responsive outdoor education as a means of understanding our life in the world

(2). They propose a manifesto for teaching about and through place. Research and practice in place-based education and its links to outdoor learning continue to flourish, but there are few references to how it can be used in an urban context. Much of the writing is nature-based and related to history, geography, traditions, stories, and literature of a place.

David Gruenwald, an early proponent of place-based education, writes “in recent literature, educators claiming place as a guiding construct associate a place-based approach with outdoor, environmental, and rural education. Place-based education is frequently discussed at a distance from the urban, multi-cultural arena” (3). He argues that the concept of place should tell the stories of the diverse communities living in cities and not ignore the many political and economic decisions that impact local areas and shape human life. He presents a strong case for a more socially critical approach to the communities in which people live, play and work.

Streetwork introduced young people to a form of experiential outdoor learning that was relevant to their lives. Through investigating and critically thinking about local issues they could appreciate the interconnections between political and economic decisions and their impact on communities and the environment. These methods and ways of thinking could then be applied to wider national and global issues. Over recent years, there has been excellent research and practice in place-based education. I believe it is time for this expertise to address the stories and issues of our rapidly changing urban areas and re-ignite a form of outdoor learning of great value and relevance p

References

1. Wattchow, B., & Brown, M. (2011) A pedagogy of place: Outdoor education for a changing world. Monash University Publishing

2. Mannion, G. & Lynch, J. (2016) The primacy of place in education in outdoor settings. In Barbara Humberstone, Heather Prince, Karla A. Henderson (Eds) International Handbook of Outdoor Studies. Routledge (pp 85-94)

3. Gruenewald, D. A. (2003). The best of both worlds: A critical pedagogy of place. Educational Researcher, 32(4), 3–12.

27

RETHINKING LEARNING SPACES

Once schools have established their ‘why’, the process continues with supporting schools to create a clear vision for outdoor learning linked to the school development plan. Included in this vision is a commitment to provide ongoing support and training for all staff members. So often we see outdoor leaders sent on courses and then having little time to implement the changes needed. When senior leaders truly value outdoor learning and provide dedicated time for the whole school to implement change, the impact is more significant. It’s essential to recognise that this is not a tick-box exercise and there is no quick fix. Schools understand this is a 3-5 year commitment, meaning they can cultivate a culture where outdoor learning is valued, sustained, and truly embedded into everyday practice.

Another crucial factor in the Teach Outdoors Whole School Approach is the network of support that we establish both within a school and within the wider community. We fully recognise that being an outdoor leader in a school can be a lonely role - yet, outdoor learning needs to be a whole school responsibility.

Being an outdoor leader and striving for whole school change is not a one-person job. In schools where this happens it is often unsustainable, and, in our experience, if the member of staff leaves the whole provision goes with them. Building a whole school community is about looking at who is going to support the development towards achieving the vision and how. For example, the English lead may already be looking at raising levels in boys’ writing, so how can outdoor learning support this? Making as many links with the whole school development is key to successful implementation, e.g., attendance, well-being, teacher retention - how will outdoor learning and access to outdoor spaces impact all of these aspects?

As many of our outdoor leaders know, there are always those members of staff who are more reluctant and may need more persuasion and support to take learning outdoors. To address this, we devised a package of monthly interactive online training sessions for staff, to aid their own professional development, but also to equip them with the skills to feel confident taking those with additional needs into outdoor environments. We also offer staff regular bitesize research updates. Teach Outdoors is keen to work with schools to contribute to the broader body of knowledge surrounding the benefits of outdoor learning. Led by our research partner Gemma Goldenberg, we are currently investigating the correlation between outdoor curriculum time and key indicators such as attendance, well-being (both for teachers and students) and nature connectedness. One of our flagship Teach Outdoors schools is actively participating in this research, providing valuable data that will inform our understanding of the relationship between outdoor education and student outcomes.

Impact of the Whole School Approach

A case study from Stanwick Primary Academy showcases the transformative impact of implementing the Whole School Approach to outdoor learning. With nearly 200 students and a dedicated staff team of thirty, the school community prioritises student engagement and active learning experiences. Recognising the value of outdoor spaces as valuable learning tools, Stanwick Primary aims to ensure that children are actively engaged in their education and avoid becoming passive learners. The school emphasises that outdoor learning can occur in any space, regardless of size or resources. Through innovative approaches and creative use of materials, such as chalk and natural elements, teachers at Stanwick foster creativity and imagination while delivering curriculum content. The support provided by the outdoor learning leader, Kirsty, has been instrumental in empowering teachers to embrace outdoor education and collaborate with like-minded educators. The Whole School Approach has helped foster a sense of community among staff members, enabling them to share ideas and best practices for implementing outdoor learning initiatives.

30

Teachers at Stanwick Primary have eagerly embraced outdoor learning as a way to enhance student engagement and address diverse learning needs. From incorporating outdoor activities into subject leadership training for staff and facilitating walking meetings, educators are exploring new ways to integrate outdoor learning into daily instruction. Through initiatives like a coastal erosion project and outdoor science experiments, students are actively involved in their learning and able to apply theoretical knowledge in practical contexts. Outdoor learning has proven particularly beneficial for children with ADHD, autism, and other special educational needs, providing a sensory-rich environment that promotes focus and reduces sensory overload. The impact of outdoor learning is evident in students’ increased motivation, deeper understanding of concepts, and improved well-being. Research conducted at Stanwick revealed noteworthy insights into the benefits of outdoor learning. Utilising the Leuven Scale for well-being and involvement, the school observed increased well-being and involvement among children outdoors compared to indoors. Moreover, the process of teachers stepping back and observing children outdoors prompted reflections on teaching practices and interactions, leading to valuable insights for the teaching staff.

Challenges

Despite these successes, Stanwick Primary faces ongoing challenges. Clothing and footwear issues are particularly evident during wet and muddy weather. Efforts like termly welly boot swaps have been implemented to address this concern. Moreover, sustaining staff momentum during colder weather remains a challenge, compounded by pressures of the curriculum, especially in core subjects like english and maths. Teach Outdoors has recognised this and included elements of the Whole School Approach training targeted specifically at core subject leads, considering how to take the existing curriculum outdoors. Funding, unsurprisingly in the given climate, also remains an issue, with Stanwick Primary seeking additional sponsorship for the programme. The school has made use of the Teach Outdoor fundraising pack in order to approach local businesses to secure funding for the remainder of the programme. As Stanwick continues to prioritise engagement, well-being, and academic progress, outdoor learning remains a cornerstone of their holistic approach to education.

Conclusion

For Teach Outdoors, the goal is clear: to challenge traditional mindsets about learning environments and make outdoor learning a norm in education. It’s about recognising that teaching outdoors doesn’t require extreme outdoor skills, but rather a shift in perspective and educational culture towards active, engaging learning experiences.

Want to find out more? Head to our website or find us at an upcoming event: teachoutdoors.co.uk p

References

1. Coe, R., Aloisi, C., Higgins, S. and Elliot Major, L. (2014) ‘What makes great teaching? Review of the underpinning research’. Sutton Trust.

2. Coe, R., Rauch, C.J., Kime, S. and Singleton, D. (2020) Great Teaching Toolkit: Evidence Review. Evidence Based Education, in partnership with Cambridge.

3. Park JH, Moon JH, Kim HJ, Kong MH, Oh YH. (2020) Sedentary Lifestyle: Overview of Updated Evidence of Potential Health Risks. Korean J Fam Med.

4. Newlove-Delgado T, Marcheselli F, Williams T, Mandalia D, Dennes M, McManus S, Savic M, Treloar W, Croft K, Ford T. (2023) Mental Health of Children and Young People in England, 2023. NHS England, Leeds.

5. NHS England. (2023) National Child Measurement Programme, England, 2022/23 School Year.

6.Hunt (2016) Monitor of Engagement with the Natural Environment: a pilot to develop an indicator of visits to the natural environment by children. Natural England.

31

RETHINKING LEARNING SPACES

Author profile

Christian is the Head of Outdoor Learning at Manor Lodge School, an independent prep school in Hertfordshire. Outside of work, he is a scout leader and enjoys spending time with his family outdoors.

I am currently Head of Outdoor Learning at a 3-11 prep school in Hertfordshire. We are lucky to have a great amount of varied outdoor space that we can use for our outdoor learning lessons. The children at our school have timetabled outdoor learning lessons for one hour a week throughout the whole year with me or one of our outdoor learning team. In addition to this, teachers of other subjects will take their lessons outdoors as frequently as possible. We have a very supportive Headteacher and Governors who allow us to be ambitious with our outdoor learning curriculum.

The problem

I was recently at the IOL North-West conference which was a fascinating and very enjoyable way to spend a wet Friday in January! While I was there, I attended a workshop led by Chris Loynes who shared insights from his fifty plus years of experience in the industry. A common theme that ran through his talk was that parents and guardians are steadily becoming more risk averse with their children, which has a knock-on impact for both participation levels and the types of experiences that we can offer children and young people. One of the clearest examples of risk aversion that Chris offered was the distance children are allowed to roam away from home unsupervised by adults and at what age. A survey conducted in 2020 (1) found that children were afforded the ability to play outside the home unsupervised almost two and a half years later than their parents and guardians were. Chris also stated that in 1970 children were allowed to travel on average 20 miles from their homes without any adult supervision, by 1990 this had dropped to 10 miles, and the latest data available shows the average 11 year old in the UK is allowed just 100 metres away from home unsupervised (2). In my own experience, I feel that this aversion to unsupervised play and adventure can develop into an aversion or wariness of organised outdoor activities and adventure, which is the antithesis of what we as

BACK TO

Christian Kitley gives us his opinion on outdoor learning

32

SCHOOL

on how to secure parental support for learning in schools

practitioners are trying to encourage. In this article, I will set out what I consider to be the problem of parental support for outdoor education and offer solutions that may help to address this issue.

Learning from the past

In the UK there have been notable incidents in the outdoor sector that, understandably, have prompted concern from parents and guardians in the past. The 1993 Lyme Bay canoeing incident springs to mind as a tragic event that resulted in the death of four teenagers and shook the confidence of outdoor providers. In more recent times, the death of an Explorer Scout in 2018 while hiking in North Wales brought the potential risks of the outdoors sharply back into public consciousness. In the wake of such incidents, major changes were made to how outdoor education centres and activities were run and how instructors were assessed for competence. While no activity can be completely risk-free, outdoor education is arguably the safest it has ever been in the UK due to lessons learned from previous tragic events.

Another reason that I feel parents and guardians are less willing to support outdoor education, and perhaps the easiest to address, is a simple lack of understanding or information. One of the most common questions I get asked by parents is ‘what do you do in outdoor learning?’, which, after my explanation, is normally followed by something like ‘wow okay, I wish they did that when I was at school!’. To me, these brief exchanges highlight the simplest way we can engage parents to get them on board with outdoor learning - we must look at how we communicate with them. Importantly, they will want to understand what outdoor learning is, what it can offer their child, how we keep their child safe and what qualifications we might have that demonstrate competence – simple stuff which, in my situation, I feel we do not yet effectively or cohesively communicate.

The solution

All this got me thinking about how we engage parents and guardians at my school with outdoor learning and how, by involving them and communicating with them more effectively, we have managed to achieve improved parental support for what we do. We already run a Friday morning parent allotment session every week, but we wanted to try something different in addition.

As part of our efforts to engage our school community more generally this year, a variety of subject areas have been inviting parents and guardians into school for group activities either with their children or as adults only. As the outdoor learning team, we ran one session each term with a different theme for each day. The sessions ran between 8:30 and 12:30 and included a range of activities depending on the theme of the day. We also included cooking a 3-course lunch as a core part of each day, mainly for fun, but also to allow the parents time to talk and connect with each other.

33

OPINION

Our three session themes were:

1. Tool work, fire-lighting and cooking - teaching parents to use saws, billhooks and axes to chop and split wood. We taught them different fire-lighting methods, which they used to build fires for cooking lunch. They harvested food from the allotments which were incorporated into their lunch.

2. Upcycling and nature - making a bird box out of a wooden pallet, researching different native birds, cooking lunch.

3. Mindfulness and natural art - using the woodland for mindfulness and meditation alongside making natural dyes and creating artwork.

The sessions were well attended with around seventy parents and guardians signing up for the first session! Unfortunately, we couldn’t take everyone, but we did invite twenty-five for the day. The number of keen adults showed us that the idea held interest for them and was worth pursuing. We had similar numbers of signups for the following two sessions, although the second session was held on a freezing January day which resulted in a few dropping out on the day. This prompted an interesting discussion point, however, as we later explained that their children still came out, happily, for their outdoor learning lessons in the same weather!

The sessions themselves were enjoyed by both parents and guardians and the staff leading them. I am lucky to have a fantastic outdoor learning team at school and we each bring different but complementary expertise to the table. These sessions were a great way to ‘show off’ our skills, which I believe has helped parents see more value in outdoor learning at our school.

One of the most surprising elements of the days for the parents was when we revealed at the end that all the activities and meals were taken from lessons that we currently teach their children from Reception up to Year 6. I think this really helped change the mindset that outdoor learning is just ‘playing in the woods’ and showed the range of soft and hard skills that outdoor learning develops.

Outcomes and conclusions

Since we started running the sessions for parents and guardians, there has been a noticeable change in attitudes towards our outdoor learning programme at school, and not just from those who attended the sessions. This change has manifested in a whole range of ways, for example in parents asking what we are doing in outdoor learning this week when they see me in the playground after school. At other times they or their children find me to tell me what ‘outdoorsy’ activities they have been up to at the weekend or during the holidays. Whether that is a change in behaviour or simply them telling me more I don’t know, but either way it shows the profile of outdoor learning being raised throughout the school and community. The number of parents and guardians wanting to see me at parents evening has jumped markedly since starting

the parent sessions and they are taking a real interest in what we are teaching their children. We have noticed a general increase in the number of adults coming along on a Friday to help out at the allotments, which is in itself another initiative to engage our school community in what we do.

In conclusion, the profile of outdoor learning and the buy-in from parents and guardians has increased a lot since starting these parent sessions and I believe it shows the power of engaging with parents on a practical level. As well as building relationships with the parents and guardians of the children we work with, the sessions have also allowed us to spread our philosophy of outdoor learning throughout the school community. We plan to continue running these sessions three times a year with changing themes as they have clearly been effective in increasing parental trust and buy-in. Hopefully, with an enhanced sense of trust and favourable perceptions of what outdoor learning (in all its guises) can offer, we will be able to introduce ever more ambitious elements into our curriculum.

Here are some of my top tips for engaging parents and guardians in outdoor learning: communicate effectively and regularly; invite them into your setting and give them a taste of what you do; be confident about your provision and the benefits to children and young people; be prepared to answer questions and concerns with positive examples of benefits for participants; and keep your provision fresh and updated so there is always something new to shout about! p

References

1. Dodd et al (2021) Children’s play and independent mobility in 2020 Results from the British Children’s Play Survey. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18(8)

2. Telegraph Reporters (2013) The decline of children’s right to roam - https://www. telegraph.co.uk/education/primaryeducation/9798930/The-decline-of-childrensright-to-roam-just-one-in-four-primary-school-pupils-are-allowed-to-walk-homealone.html

BACK TO SCHOOL 34

SPRING FORAGING

In Lizzy Maskey’s latest article, she explores what’s

around during spring

Author profile

Lizzy Maskey runs Pippin & Gile a bushcraft school based in the South-East established in 2018. Lizzy has been teaching outdoor eduction since 2013 and moved to formalise and extend her bushcraft knowledge in 2016. Lizzy launched Pippin & Gile after returning from cycling 9000km to Kazakhstan unsupported. When not cycling or teaching, Lizzy is always looking to learn and develop and can be found exploring hedgerows and muddy puddles across the UK and around the world.

Spring is a time when it feels like the world is waking up and that life is full of possibilities. The birds start to sing, the alarm goes off after dawn and sunset is the right side of dinner time.

It’s a great time to be outside and to spot the everchanging patterns of the seasons. I spent February out of the country and feel like I’m playing catch up now with springtime - especially as it seems that things are out earlier this year. As spring marches forward, we will start to see many more edible delights coming through in our woodlands, hedgerows and edges.

The ‘forgotten wastelands’ at the side of roads, buildings and the strips at the edges of woodlands that are not viable to grow crops on as it’s too dark - these are all great places to find a myriad of different plants, including many edibles.

We are seeing the joys of fresh nettle (Urtica dioica & Urtica urens) tops, and soon the constant social media posts about wild garlic will take over our feeds. Find an area near you that

used to be habited, or maybe still is and keep an eye out for ground elder (Aegopodium podagraria). This plant has a beautiful taste when fresh, soft, young and bright green, and grows in profusion. Ground elder can be treated like spinach or any other green leafy vegetable. I often sauté it with some onions or add it to scrambled egg. Do check if it’s on someone’s land that they haven’t added any herbicides to it though. Gardeners do not like this plant as it’s incredibly successful at growing anywhere and everywhere, and will smother the vast majority of other small plants. The timing of its introduction to the UK is disputed. It was either by medieval monks for its medicinal properties (predominantly for gout), or by Romans as a pot herb, however what is rarely in dispute is that it escaped the pot and has since become a nuisance weed for many gardeners. It can be found growing

in a wide selection of habitats, often associated with older dwellings. So, if you do find a patch not in a garden, do a bit of sleuthing and you’ll often find that it was the site of an old garden.

and

35

A slope of scrub land beside a rural road with a wonderful mix of edible and useful plants.

Wild garlic (Allium ursinum)

English bluebells (Hyacinthoides non-scripta) in an ancient woodland.

Ground elder (Aegopodium podagraria) grows rampantly wherever it is found, usually in association with habitation.

Late spring bounties

After the bounty of April, May can always feel like a bleaker month for foraging, as many of the early spring greens are starting to grow tough and stringy. But fear not, there are some foraging bounties still to be had before the summer comes along. Often with foraging we think of small green plants and fungi, but don’t forget the trees. A huge number of our native and naturalised trees can be foraged for a range of materials, many of which are edible and (most importantly) incredibly tasty! As the sap starts to rise, before the first hints of green become visible, the buds will swell and tinge the tips of the trees with a beautiful palette of colours, mostly pinks and purples.

I love seeing the light from the canopy close over and the long thin strips from beech (Fagus sylvatica) buds drifting to the ground, as it signals to me that two weeks of incredible foraging are about to start. Whilst the beech leaves are incredibly soft and their edges are still slightly downy you can eat these leaves as they are. They’ve got a delicate, slightly sweet flavour, that makes an excellent base for a wild salad – in my house, we often serve them with a sprinkling of wild-flowerpower petals on top, including dandelions (Taraxacum sp.), primroses (Primula vulgaris), sweet violets (Alliara riviniana), hawthorn (Crataegus monogyna) blossom and white dead nettle (Lamium album). One of the many joys of the beech leaf and leaf harvests in general is the sheer volume that you can collect without making a significant impact on each individual tree.

Whilst foraging on our courses we talk about the rule of 1/7th (which encourages foragers to pick no more than one seventh of what is on offer), but this can often be misinterpreted and sometimes leads to lots of number crunching. I tend to encourage people to pick in a way that, should an observant walker pass by after you’ve left, they would not notice that you had been there. Of course, the next forager is likely to spot a few missing growing tips of some plants and other signs, but the casual observer should not be able to see your foraging progress.

Lovely lime

After the beech leaf extravaganza is nearing its end, don’t worry the lime (Tilia sp) leaves are on their way. Lime is a wonderful tree, if you have ever done cordage work you will most likely have come across the joys of working with the inner bark of the lime tree. Again, you get about two weeks where these leaves are at their best and can be used shredded or cut into strips in a salad. Once the

leaves are fully out it’s the perfect time to coppice the lime for its inner bark, or bast. The sap has risen, which means that stripping the bark and inner bark from the tree is a much easier job. Though still one that will get your heart rate up and muscles aching the next day. Bundle the stripped bark up and chuck it into a stream or river to rot down, this is a controlled rotting process. You’ll know it’s ready when the layers start to delaminate. The lime bast has many uses now, from coil basketry to cordage and rope making. Any fibres that don’t make the grade make for incredible tinder.

We have honeybees near

36

Young fresh beech (Fagus sylvatcia) leaves are incredibly soft, an almost iridescent green and their edges are still slightly downy.

Lime (Tilia sp.) in leaf. These trees were planted as a short avenue in front of a local large house.

SPRING FORAGING

Dolmades – with foraged ingredients

Ingredients

For the dolmades

• 1 cup of rice

• ½ cup of olive oil

• 2 cups of water

• 2 large fistfuls of water mint (or any other mint), finely chopped

• 1 large fistful of wild marjoram or oregano, finely chopped

• 1 handful of wild fennel, finely chopped

• 3 tomatoes, chopped

• 50-100g of lamb mince (optional)

• 50 lime leaves (look for large, bright leaves without any nibble marks on them)