GOING, GROWING, GONE: THE PUBLIC SECTOR IN A ‘NEW’ NEW ZEALAND

MAKING IT REAL: HOW TO IMPLEMENT AI IN THE PUBLIC SECTOR FROM THE CLASSROOM TO THE PUBLIC SECTOR: THE DIFFERENCE CIVICS EDUCATION CAN MAKE

GOING, GROWING, GONE: THE PUBLIC SECTOR IN A ‘NEW’ NEW ZEALAND

MAKING IT REAL: HOW TO IMPLEMENT AI IN THE PUBLIC SECTOR FROM THE CLASSROOM TO THE PUBLIC SECTOR: THE DIFFERENCE CIVICS EDUCATION CAN MAKE

When building a team, it’s important to get three things right: People, Skills and Dynamics.

The Johnson Group has worked across the public sector since 2005. A member of the All of Government Recruitment Panel and regarded for our expertise in public sector recruitment, our consultants are specialists who understand the very specific skill sets required of public sector professionals as well as the intricacies of the Wellington market

We know our candidates well - from what drives or interests them to how they fit into your team to deliver excellent outcomes

Whether you’re seeking a change in 2024 or need assistance in growing your team, we’re here to help.

PUBLISHER

The Institute of Public Administration New Zealand

PO Box 5032, Wellington, New Zealand

Phone: +64 4 463 6940

Email: admin@ipanz.org.nz

Website: www.ipanz.org.nz

ISSN 0110-5191 (Print)

ISSN 1176-9831 (Online)

The whole of the literary matter of Public Sector is copyright. Please contact the editor if you are interested in reproducing any Public Sector content.

EDITOR

Kathy Catton: editor@ipanz.org.nz

CONTRIBUTORS

Stephen Clarke

Claire Finlayson

Chelsea Grootveld

Elena Higgison

Liz MacPherson

Jim McAloon

Zaira Najam

Kara Nepe-Apatu

James Picker

Taylah Shuker

Paul Spoonley

Deb Te Kawa

JOURNAL ADVISORY GROUP

Barbara Allen

Kay Booth

Kathy Catton

Liz MacPherson

Liam Russell

ADVERTISING

Phone: +64 4 463 6940

Email: admin@ipanz.org.nz

CONTRIBUTIONS

Public Sector welcomes contributions to each issue from readers.

Please contact the editor for more information.

SUBSCRIPTIONS

IPANZ welcomes both corporate and individual membership and journal subscriptions. Please email admin@ipanz.org.nz, phone +64 4 463 6940 or visit www.ipanz.org.nz to register online.

DISCLAIMER

Opinions expressed in Public Sector are those of various authors and do not necessarily represent those of the editor, the journal advisory group, or IPANZ. Every effort is made to provide accurate and factual content. The publishers and editorial staff, however, cannot accept responsibility for any inadvertent errors or omissions that may occur.

Public Sector is printed on environmentally responsible paper produced using ECF, third-party certified pulp from responsible sources and manufactured under the ISO14001 Environmental Management System.

Inside this issue

2 PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE

3 LEAD STORY

Going, growing, gone: The public sector in a ‘new’ New Zealand Distinguished Professor Emeritus Paul Spoonley outlines the main changes projected for Aotearoa New Zealand's demography and the impact of these changes on our public services.

8 REFLECTIONS

Spirit, trust, and change

Public Sector talks to Taylah Shuker, winner of the 2023 IPANZ Public Administration Prize and finds out more about her love for the ‘spirit’ of service.

10 INVESTIGATION

Making it real: How to implement AI in the public sector

In the second in the series of articles about AI in the public sector, Stephen Clarke offers practical suggestions for implementing AI in the public sector. Please note this article has been updated and supersedes the original version.

14 INSIGHTS

Te Rau Hihiri: Nurturing Māori in the public sector

We find out more about Te Rau Hihiri, the charitable trust empowering and advocating for Māori working in and with the public sector.

16 ANALYSIS

More heat than light: IPANZ contributions to the free and frank advice discussion Deb Te Kawa highlights IPANZ’s critical contributions to the free and frank advice discussion and links interested readers to the relevant material.

18 INVESTIGATION

From the classroom to the public sector: The difference civics education can make Writer Claire Finlayson explores the current state of civics education in Aotearoa New Zealand and asks how students, public servants, and all citizens can benefit from strengthening their knowledge on this subject.

22 HISTORY OF THE PUBLIC SECTOR

History of the Ministry of Works

Jim McAloon, Professor of History at Te Herenga Waka – Victoria University of Wellington, provides a summary of the history of the Ministry of Works, once described as the country’s first super-department.

24 INSIGHTS

Public governance: Iti Kōpara steps up Chelsea Grootveld, Deputy Chair and Board Trustee at Iti Kōpara, talks about public governance and recent developments to address gaps.

26 INSIGHTS

Ombudsman launches free online learning about official information

The Ombudsman has created a new online learning platform for people in the public sector who deal with official information or want to know more about it.

27 BOOK AND PODCAST REVIEW

IPANZ New Professionals’ Network Member Zaira Najam reviews a Westminster Tradition podcast episode and the recently published book Towards a Grammar of Race edited by Arcia Tecun, Lana Lopesi, and Anisha Sankar.

28 DID YOU KNOW?

How Parliament’s budget cycle works

We uncover some fascinating facts about the Parliamentary Budget cycle.

I was intending to write about demography. About how, just like a slow slip earthquake, the shifts in our population structure were transforming the shape of Aotearoa New Zealand. About how in ten years, almost a quarter of the population will be over 65, and most will be Pākehā. About how around 50 per cent of school leavers will be Māori, Pasifika, or from one of the many Asian communities. Young people with vastly different lived experiences than those they will replace in the workforce, in business, in the public service, and in government. I was pondering the kind of leadership needed to help us transform to meet the needs and aspirations of this super-diverse demographic tsunami.

Then, like a seismic shock, came the news of the sudden passing of one such leader – Fa’anānā Efeso Collins, and I had my answer. A man who only a few days earlier had made his maiden speech in the House, a speech that would also serve to be his valedictory. A man who declared, “I’ve come to this House to help. Helping is a deliberate act. I’m here to help this government govern for all of New Zealand, and I’m here to open the door, enabling our communities to connect better with this House.” A man who said of his legacy, “If I was to inspire anyone by getting to this House

… I hope that it’s the square pegs, the misfits, the forgotten, the unloved, the invisible – it’s the dreamers who want more, expect more, are impatient for change, and have this uncanny ability to stretch us further.”

Today as I write, New Zealand flags will be at half-mast out of respect for the passing of a beloved leader who was able to cross boundaries – politics, ethnicity, community, business, government. A man who led with empathy and with courage. Who was able to bring people together, use humour to disperse tension, and create space to focus on the things that matter. Who never, no matter how high his profile got, lost touch with his community. Whose pathway to leadership was one of service. A man whose life will bring courage and inspiration to an up-and-coming generation of dreamers and servant leaders. The leaders our new New Zealand needs.

Ia manuia lau malaga, Fa’anānā

E te rangatira, moe mai rā, moe mai rā, moe mai rā.

Paul Spoonley

outlines the projected changes for Aotearoa New Zealand's demography and the impact of these changes on our public services.

This decade (2020–2030) is going to prove transformative for Aotearoa New Zealand as the demography of the country changes. As the 2030s unfold, the demographic profile of the country and of particular regions and centres will have changed significantly with implications for the way in which the public sector interacts with – and responds to – this new demography.

The shape of this ‘new’ New Zealand has been obvious for some time. However, certain shocks – notably the Global Financial Crises (GFC) (2008–2012) and the crisis period of the Covid-19 pandemic (2020–2021) – have altered the speed and impacts of demographic change. The somewhat puzzling aspect of public understanding is that there is seldom an appreciation of the various moving parts or the size of the implications.

An old-age-dominant society

That said, there appears to be a growing appreciation that the ageing of Aotearoa New Zealand is an important factor as we think about the provision of services and the costs of those services. The size of the Baby Boomer generation, born between 1945 and 1964, is now reconfiguring the population profile of the country. New Zealand saw one of the most prolonged spikes in fertility of any high-income country, with 4.7 births per female. We now measure the impact of that period by those reaching the age of 65 (please note that this is no longer the age of retirement for many), which began for the Baby Boomers in 2010 and will continue through to 2029.

In 1981, the over-65-year-olds made up 7 per cent of the population. By 2033, [this group] will constitute 21 per cent of all New Zealanders.

Demographers talk about the numerical and the structural impacts of ageing. Both have considerable implications for the provision of services and, of course, paying for them. For example, the increase in the Long-Term Care (LTC) beds required will exceed GDP growth over the coming decades. Who pays for this and where should the care be provided?

In 1981, the over-65-year-olds made up 7 per cent of the population while 0–14-year-olds comprised 27 per cent.

By 2033, the over-65-year-olds will constitute 21 per cent of all New Zealanders and 0–14-year-olds now 16 per cent (StatsNZ projections, 2022 base, median figures). This gap continues to widen further through the 2030s and 2040s.

The ageing of society is compounded by the decline in fertility. The Total Fertility Rate required to replace an existing population is 2.1 births per woman. At the end of the GFC, New Zealand’s rate was still at replacement level but a year later, in 2014, it had dropped to 1.92 and then by last year, was down at 1.58 births per woman.

This means that natural increase (the number of births minus the number of deaths) is less of a factor in terms of population growth. In 2023, New Zealand grew by 105,900 people, but most of this came from net migration, with natural increase contributing 19,100. It also means fewer births: 64,341 in 2008 compared to 58,887 in 2022. That is why the Ministry of Education is forecasting 30,000 fewer in the compulsory education sector by 2030.

What is transforming New Zealand, both in terms of ethnic and faith diversity as well as where people live, is immigration. More than 80 per cent of New Zealand’s population growth now comes from net migration. What should be noted is that the immigrant arrivals, along with departures (we are currently seeing a return to the net loss of New Zealand citizens at very high levels) and net migration gains fluctuate a lot. The most recent comparison is between the Covid-19 years: in the year to February 2021, total immigrant arrivals numbered 60,524 (so not a completely closed border then) with a net gain of 9,489 compared to November 2023 when arrivals numbered a historic high of 249,504 with a net gain of 127,400.

Given that the three most common source countries for these recent arrivals are India, the Philippines, and China (in that order), there are major current and future impacts on cultural diversity, especially for the school and workingage populations. Add in the still high population growth of Māori, and young New Zealand looks very different over the coming decades. By 2043, StatsNZ (September 2022) estimated that 21 per cent of the population would identify

as Māori, 24 per cent with one of the Asian communities, and 11 per cent with one of the Pasifika communities. But what is interesting is that the 0–14 age groups would now be 33 per cent Māori, 25 per cent Asian, and 19 per cent Pasifika.

The final element is where New Zealanders will live. We have long been forecasting either population stagnation (no or little population growth) for many Territorial Authorities or population decline (depopulation) for some. In contrast, a significant proportion of future population growth will occur in the top half of the North Island.

Given that Auckland tends to be the main beneficiary of immigrant arrivals and settlement, we should anticipate that the city will see growth of another 500,000 to 700,000 over the next two decades, and it is possible that 40 per cent of New Zealand’s population will be Auckland residents by the late 2030s. This could change, but will it?

The question now becomes how does the public service adjust to these new demographics? As a recent Goldman Sachs report made clear, the ageing of societies and workforces, combined with declining fertility and a reliance on immigration, all reshape the macro-economic and public investment landscape.

By 2043, StatsNZ (September 2022)

estimated that 21 per cent of the population would identify as Māori, 24 per cent with one of the Asian communities, and 11 per cent with one of the Pasifika communities.

implications

As a long-term judge for the Diversity Awards, it is rewarding to see many parts of the public sector thinking about what they need to do to adjust policies and practices given the ever-growing diversity of the country. As an author of annual surveys of employers for Diversity Works (up until recently), I would note that public service managers and leaders have led the private sector in terms of gender, ability, ethnicity, and tangata whenua recognition. But there are significant gaps and a lot more to do if community and national diversity is to be fully recognised and incorporated into the public sector.

There are particular gaps and tensions. The journey to more adequate recognition of Te Tiriti o Waitangi and the significance of tangata whenua in this future Aotearoa

New Zealand appears to have produced what can only be labelled as ‘white anxiety’ and a political reaction. Politicians and the public sector seem to have either misread or failed to adequately address issues such as the reasons for co-governance or the incorporation of Te Tiriti or te Reo in what they do – or plan to do. The recent emergence of a much more assertive denial politics might have underestimated how embedded some of the changes of the last 40 years have become or how important the future demography and economy of tangata whenua will be to Aotearoa New Zealand.

(b) Ageing

A second gap concerns ageing. The size and longevity of New Zealand’s older population is going to put new fiscal stresses on the state as well as significantly shift a range of economic dynamics. Think of the dependency ratio (those in work compared to those who are not in paid work and are beneficiaries of state support) or the entry/exit ratios (those entering the workforce compared to those exiting). How the state generates income, how it distributes that income, and what it prioritises will all fundamentally change.

It is possible that 40 per cent of New Zealand’s population will be Auckland residents by the late 2030s.

The issue is often political – a reluctance to factor in median and long-term considerations given the exigencies of a three-year political cycle or the willingness to consider and respond to good-quality data. But there is also the fact that a number of employers, including those in the public sector, acknowledge that ageing is an issue but then do not develop workplace and delivery policies to address the issues.

(c) Ethnic diversity

Thirdly, there is the superdiversity that continues to change communities. We should expect that about one in five of us will self-identify as tangata whenua, a similar proportion as a member of one of New Zealand’s Asian communities, and another 10–11 per cent as Pasifika. All these percentages increase by quite some margin if we are talking about the percentages of indigenous and ethnic groups in our education system, certain parts of the country, or in relation to the workforce. What sort of investments and policies address growing diversity and enhance social cohesion?

The nature and extent of New Zealand’s demographic changes are such that many of our existing policies and approaches will simply not work.

Finally (and there are many other matters to consider, such as generational differences in wealth accumulation, and debt or labour market opportunities) there is the vexed question of the demographic trajectories of different regions and centres. Many New Zealanders (especially local politicians) seem unwilling to confront the possibility that their part of the country will face significant ageing (possibly hyper-ageing) or that they will experience population stagnation or depopulation.

The nature and extent of New Zealand’s demographic changes are such that many of our existing policies and approaches will simply not work. But how do we have the discussion about what will work? And where will the innovative policy and political leadership come from? How do we renegotiate existing social contracts to reflect these new demographics?

I also want to echo former New Zealand Statistician (1992–2000) Len Cook’s concerns that we need to have a robust population data collection system – which is in some danger at the moment – and we need to develop a better understanding of the medium- and long-term implications of population change and what this means for public service investments.

Distinguished Professor Emeritus Paul Spoonley was Pro ViceChancellor of the College of Humanities and Social Sciences at Massey University. He was one of the lead researchers in the Capturing the Diversity Dividend of Aotearoa New Zealand research programme. Recently, he has been Co-Director of He Whenua Taurikura (National Centre for Countering Violent Extremism) and part of a panel advising the Police Commissioner. He Co-Chairs Metropolis International, the largest global network of immigration and diversity specialists. He is the author or editor of 29 books, including The New New Zealand: Facing Demographic Disruption, published by Massey University Press, Auckland.

Public Sector journal is always happy to receive contributions from readers.

If you’re working on an interesting project in the public sector or have something relevant to say about a particular issue, think about sending us a short article on the subject.

Contact the editor Kathy Catton at editor@ipanz.org.nz

But with a right fit fleet it could save some.

Let Brother optimise your print solution, making sure you have everything you need and nothing you don’t, helping reduce costs, so you can invest the savings into other areas of your organisation.

Get a quote today and make the change to Brother. brother.co.nz/government

It just works.

Taylah Shuker (Ngāti Pākehā) is the recipient of the 2023 IPANZ Public Administration Prize for the top student in PUBL 311 Emerging Perspectives in Public Management at Te Herenga Waka – Victoria University of Wellington School of Government. In this article, Taylah discusses her love for the ‘spirit’ of service, while also shedding light on the challenges posed by eroding trust.

Imoved to Pōneke from Waimea to study a Bachelor of Laws and a Bachelor of Arts majoring in Japanese and Public Policy.

I am passionate about building a sense of community, making sustainable change, and translating complex thinking into accessible resources. My background is in social impact measurement, community organising, and law. I am currently employed at Deloitte in the Artificial Intelligence and Data team. I work with various clients to understand how technology can be leveraged to tackle complex problems, while ensuring good governance, risk management, and equity.

What do you love about the public sector?

Throughout my study of public policy, I have realised how much I appreciate the emphasis on the sector’s collective identity through the notion of the ‘spirit’ of service. Its codification in the Public Service Act 2020 not only underscores its symbolic significance, but it also provides certainty to, and accountability for, the public service about their identity. Moreover, the importance of a collective identity will grow as policy issues become more complex and require greater cross-sector collaboration. Thus, the ‘spirit’ of service will serve as a unifying force across the public sector, to drive effective policymaking and increase trust in public management.

do you see as some of the challenges facing the public sector?

One of the most significant challenges facing the public sector

is the erosion of trust. Although the causes of eroding trust are multi-faceted, there are two in particular which I find most notable.

First, within our diverse society, trust is eroded by polarising voices drowning out constructive dialogue. This is arguably leading to disenfranchisement and disengagement across various communities. The impact of eroding trust may culminate in progress paralysis. Progress paralysis ensues when decision-makers, fearing backlash or failure, opt for inaction. This is problematic as it can exacerbate existing policy challenges and perpetuate the perception of public sector inefficacy.

The

‘spirit’ of service

will serve as a unifying force across the public sector.

To address this, the public sector will need to ensure proactive measures are used to drive transparency, accountability, and collaboration. By embracing approaches like networked governance, the impact of polarising voices can be overcome. This is because greater community engagement and stakeholder collaboration reinforce good decision-making processes which, in turn, increase trust.

Secondly, the considerations around accountability and transparency when adopting new technologies, such as AI, are not always being effectively communicated which is causing distrust. This is particularly notable for issues relating to data privacy, governance, and Māori data sovereignty. The impact of ineffective communication is leading to a failure to adapt to, and take advantage of, technological advancements. If this continues, we will see the public sector being left behind and unable to harness the potential of data and AI to effectively address society’s needs.

By addressing the underlying causes of distrust and implementing proactive strategies to foster transparency and collaboration, we can mitigate its impacts and move towards a more resilient and responsive public sector.

From a technological perspective, trust can be increased through transparent communication, alongside supporting legal frameworks and policies that govern the ethical use of technology. Greater communication will help alleviate technology concerns, work towards successful adoption, and improve user trust.

Finally, as mentioned earlier, the ‘spirit’ of service will lend itself to increasing trust. This is because communities will be more likely to perceive the public sector as a unified front that collaborates for progress, and upholds cross-sector technological standards. Additionally, a strong collective identity will encourage innovation within the public sector, leading to better policy outcomes, more responsive governance, and pragmatic applications of technology. Overall, the erosion of trust in Aotearoa New Zealand’s public sector demands concerted efforts to navigate polarising discourse and embrace technological change. By addressing the underlying causes of distrust and implementing proactive strategies to foster transparency and collaboration, we can mitigate its impacts and move towards a more resilient and responsive public sector.

One of the most significant challenges facing the public sector is the erosion of trust.

Finally, I am incredibly grateful to be a recipient of the 2023 IPANZ Public Administration prize. Thank you to the incredible staff at Te Herenga Waka – Victoria University of Wellington School of Government, including the brilliant public policy lecturers, and IPANZ for this honour. I look forward to continuing to grapple with challenges relating to the public sector and exploring how AI and data can be leveraged to enable sound policymaking.

With our public sector focused squarely on their savings numbers we are seeing recruitment freezes and internal resource reallocations becoming common place. The media is dining out on morning teas becoming ‘BYO plate’ and the possibility of public servants dossing down at a friend’s place while traveling for work if they are not already meeting virtually instead.

Cost is king but what’s next? We are anticipating that May will bring more than just budget certainty to the agencies. It should also bring a sense of direction, consolidate future work programs and refocus agencies from what they needed to stop to what they need to start to deliver new initiatives. A degree of stability will return as structural changes are completed.

If you want to discuss what is going to happen in the market, feel free to reach out to Shane Mackay or Naomi Brennan on 04 4999471 or Email: shane.mackay@h2r.co.nz or naomi.brennan@h2r.co.nz

In the second of a series of articles for Public Sector, Stephen Clarke, Digital and Information/ Data Management Consultant, and former Chief Archivist, offers suggestions for implementing artificial intelligence (AI) in the public sector.

The integration of AI holds the promise of transformative benefits within the public sector. Yet moving from experimental phases to full-scale implementation demands a thoughtful strategy that confronts challenges head-on while harnessing existing resources to seize the opportunities at hand. This article seeks to offer a step-by-step approach as to how implementation and delivery might be achieved, including an overview of the barriers and opportunities to AI public service delivery.

Understanding the public sector landscape

Within the landscape of the public sector, distinct considerations shape the pathway towards AI integration.

Unlike the private sector, the public sector operates under

heightened user expectations, deeply rooted in regulatory accountability. Any deployment of AI must match these values while also recognising the complexities of risk-averse leadership, dynamic political priorities, and multifaceted policy objectives.

There are, of course, a spectrum of challenges involved in implementing AI in the public sector. From navigating stringent data privacy regulations to operating within antiquated IT infrastructures, public agencies grapple with complexities that are more than just technical. The potential lack of in-house expertise exacerbates the reliance on external talent, a move not always welcomed within political realms. Ethical considerations loom large, compelling agencies to anchor their AI endeavours in principles of accountability and fairness. Resource constraints, both financial and procedural, pose barriers to scaling AI initiatives within bureaucratic frameworks, often relegating

them to short-lived projects rather than sustainable solutions.

Amidst these challenges, opportunities do exist for those willing to navigate the terrain. Embracing local partnerships can foster co-creation, ensuring that AI solutions resonate with the nuanced needs of communities. Also, engaging in global knowledge-sharing platforms means public agencies can learn from international best practices. Collaborating with academic institutions not only nurtures research endeavours but also cultivates talent and explores innovative AI applications tailored to public service. Additionally, forging public-private partnerships offers avenues for co-investment and risk-sharing, leading to AI solutions that not only benefit citizens but also uphold principles of accountability and transparency in their implementation.

Moving from experimentation to delivery: Establish the foundations and run a pilot Firstly, strategic alignment is crucial from the outset. It’s imperative to ensure that AI initiatives resonate with organisational objectives, priorities, and stakeholder needs. This alignment ensures that the efforts put into AI development are not only innovative but also directly contribute to the overarching goals of the institution.

Capacity building emerges as another crucial aspect. While investing in AI and nurturing data-literate talent is essential, it’s equally important to leverage existing skills within the organisation. Conducting a thorough skills audit will likely reveal latent technical expertise among staff members who may not have AI-related titles but possess valuable insights and capabilities.

Infrastructure and technology play pivotal roles. Rather than waiting for new solutions, it’s well worth using existing resources. Many vendors already offer AI stacks (framework of tools and technologies) that can be readily implemented, and internal systems may hold untapped potential. Collaborating with vendors and exploring internal capabilities can expedite the implementation process.

Governance and compliance form the bedrock of ethical and responsible AI deployment. Establishing clear governance frameworks from the outset ensures trust and transparency in AI operations. However, it’s vital to strike a balance between governance and innovation, avoiding excessive bureaucratic processes that stifle progress.

Continuous improvement is inherent in successful AI deployment. Monitoring KPIs, gathering user feedback, and analysing any operational metrics enable organisations to

refine AI models and workflows iteratively. This iterative approach ensures that AI solutions evolve in tandem with emerging trends and user requirements.

Lastly, establishing a robust use case matrix (a methodology to identify system requirements) is paramount. By carefully assessing and selecting AI use cases that align with critical criteria, organisations can streamline their pilot phases and focus resources on initiatives with the highest potential for success. Pilot phases are highly valuable and certainly considered best practice.

Moving from experimentation to delivery: From pilot to operational delivery

Transitioning an AI use case from a pilot or proof of concept (POC) to operational delivery is critical in realising its potential. This process requires careful consideration of technical, ethical, and organisational factors to ensure that

the deployment is both practical and responsible. Set the foundational guiderails at the beginning.

• Evaluation and learning: Before scaling up an AI use case, it’s essential to conduct a comprehensive review of the pilot or POC. Assess the performance, accuracy, and reliability of the AI model against predefined metrics and benchmarks. Leverage insights from the evaluation process to refine and optimise the AI model, data pipelines, and deployment workflows.

• Scalability and infrastructure: Evaluate the scalability and infrastructure requirements needed to support operational deployment. Assess the hardware resources, storage capacity, and bandwidth needed to accommodate increased data volume and processing demands. Leverage cloud-based infrastructure and scalable AI platforms to support dynamic scaling and resource provisioning.

• Data governance and quality: Establish foundational robust data governance frameworks to ensure the integrity, privacy, and security of the data used by the AI model. Define clear policies and procedures for data collection, storage, access, and sharing. Implement data quality assurance measures to mitigate biases, errors, and inaccuracies that may impact the performance and fairness of the AI model.

• Ethical considerations: Conduct ethical impact assessments to evaluate the societal, cultural, and equity implications of the AI deployment at the beginning as a go/no go gate. Ensure that the AI model adheres to principles of fairness, transparency, accountability, and inclusivity. Engage early with diverse stakeholders, including impacted communities and civil society organisations, to solicit feedback and address ethical concerns.

• Regulatory compliance: Collaborate with legal experts and regulatory authorities early to assess regulatory risks and ensure adherence to compliance obligations. Document and maintain comprehensive records of compliance efforts and risk mitigation strategies.

• Training and capacity building: Bring your people on the journey and include those running service as BAU early, making the transition seamless. They will already know the issues from previous experience with users.

• Monitoring and evaluation: Establish key performance indicators (KPIs) and metrics to measure the effectiveness, efficiency, and equity of the AI deployment. Monitor in real-time, iterate, and optimise.

• AI services sustainability: Establish long-term sustainable funding models. Short-term thinking and products that don’t have longevity considerations built into the design, eg, minimum viable products do not have long-term sustainable service delivery in mind. This is both wasteful and frustrating for service users.

AI presents a profound opportunity to enhance operational efficiency and unlock the latent value within public sector data. As governments navigate the complexities of integrating AI into service delivery, an often overlooked aspect is the potential for commercialisation of public sector data.

At the heart of AI-driven innovation lies data – the lifeblood of digital transformation. The public sector accumulates vast repositories of data across various domains, ranging from healthcare and transportation to education and urban planning. However, the true potential of this data remains

largely untapped. By harnessing AI algorithms, governments can derive actionable insights, identify patterns, and predict trends, thereby transforming raw data into valuable assets.

AI-powered analytics enable governments to monetise public sector data through various channels. From insights-as-a-service models to data licensing agreements, governments can explore diverse revenue streams while ensuring equitable access to valuable data assets. By leveraging AI algorithms for predictive analytics, demand forecasting, and trend analysis, governments can unlock new market opportunities, stimulate economic growth, and create sustainable revenue streams.

In conclusion, the integration of AI in the public sector holds immense promise for transformative benefits, but it requires a strategic and thoughtful approach. Firstly, strategic alignment with organisational objectives is paramount, followed by capacity building, infrastructure utilisation, governance establishment, and continuous improvement.

Transitioning from pilot to operational delivery involves evaluation, scalability assessment, data governance, ethical considerations, regulatory compliance, training, monitoring, and sustainability planning.

Public sector data is immense and AI offers opportunities for sustainable innovation and revenue generation through careful use of this data. By unlocking the value of data and leveraging AI-powered analytics, government agencies can create new market opportunities, stimulate economic growth, and ensure equitable access to valuable data assets.

In essence, implementing AI in the public sector requires a holistic approach that balances innovation with ethical considerations, regulatory compliance, and sustainability. By embracing this approach, government agencies can harness the full potential of AI to improve service delivery, enhance operational efficiency, and foster societal wellbeing.

Stephen is a Virtual CDO and Information/Data Management Consultant. Originally from the United Kingdom, Stephen has worked in senior information and data management roles across the New Zealand public sector for the last 15 years. His most recent role was as Chief Archivist, after moving on from his role as Chief Data Officer at the NZ Transport Agency. Stephen has undertaken similar roles in IRD, DIA, Office of the Auditor-General, the Office of the Ombudsman, and Transpower. Internationally, Stephen is known as a standards expert, having developed standards for information management for Australia and New Zealand and internationally for ISO. As an anthropologist Stephen understands human systems, and as a technical expert he understands information systems. Using technology to connect these two systems to get the right information, to the right people at the right time, ethically, is his professional goal.

Te Rau Hihiri is a charitable trust empowering and advocating for Māori working in and with the public sector. This article highlights key events in its history and its future focus.

In the age of social media, a seemingly simple post sparked a viral conversation among Māori public servants: “Public servant vs Māori public servant”. This post resonated with over 70,000 people, transcending borders and prompting discussions within indigenous communities globally. The dialogue underscored the need for conversations about the indigenous experience within the public sector and, in response, Te Rau Hihiri emerged as a catalyst for empowerment and advocacy.

Te Rau Hihiri stands on a mission to empower and advocate for Māori working in and with the public sector. The organisation achieves this by creating events and opportunities for Māori public servants to connect both

online and offline; share mātauranga (knowledge); receive recognition; access leadership opportunities; and contribute to a thriving, interconnected hapori. Rooted in values of culture, connection, creativity, and calibre, Te Rau Hihiri embarked on its journey in 2021, driven by a pivotal moment experienced by Chair Kara Nepe-Apatu.

Kara’s moment of realisation occurred during a conference in 2021, where she witnessed mispronunciations of Māori words and a lack of substantive discussion on vital topics. This experience propelled her to challenge the status quo and call for events created by, for, and with Māori. Te Rau Hihiri was subsequently formed with five wāhine Māori trustees, drawing inspiration from the oriori (lullaby) by Tuteremoana. The name ‘hihiri’ emphasises dynamism, diligence, and determination, while ‘rau’ embodies the collective mana of the takitini (collective/many).

In March 2022, Te Rau Hihiri organised its inaugural event, Poipoia te Manawa Māui, an online conference attended by 300 Māori public servants. The event featured candid discussions and ‘gnarly’ kaupapa presented by Māori leaders from the public service and iwi. “Our kaikōrero didn’t hold back,” shares Te Rau Hihiri trustee Elena

Higgison. “They shared insights on moving beyond good intentions to good practice, upholding the integrity of mātauranga Māori in non-Māori spaces, and reimagining the public service for a better tomorrow.”

Responding to the call for more connection and action, Te Rau Hihiri launched its Kai Whai Hua event series in late 2022. These events strengthen whanaungatanga over kai, focusing on ‘real talk’ kaupapa. Themes to date include strategies to reindigenise ways of working, translating mana ki te mana relationships to the mahi level, and strengthening tuakana teina relationships. To date, Te Rau Hihiri has hosted eight Kai Whai Hua events, attracting over 400 participants from various agencies.

The name ‘hihiri’ emphasises dynamism, diligence, and determination, while ‘rau’ embodies the collective mana of the takitini.

Recognising the need to extend their impact beyond Wellington, Te Rau Hihiri took Kai Whai Hua on the road,

organising their first regional event in Hamilton in late 2023. These events provide a safe space for Māori public servants to share challenges and aspirations, addressing issues such as feeling culturally unsafe and the undervaluing of expertise. “Now more than ever, we need spaces to come together to manaaki each other and share strategies on navigating change,” says Kara.

Te Rau Hihiri has received strong support from mana whenua Te Āti Awa and Ngāti Toa Rangatira from the outset. The organisation actively participates in initiatives supporting Māori public servants, including a recent hui hosted by Te Āti Awa in Waiwhetu, where over 200 Māori public servants gathered to build whanaungatanga and cocreate solutions focused on manaakitanga.

Looking ahead, Te Rau Hihiri is focused on supporting the development of Māori leadership and nurturing a pipeline of young Māori talent within the public service. In the face of changes within the public service, including the new coalition government’s 100-day plan, Te Rau Hihiri has launched its own 100-day plan on social media, featuring daily messages of optimism, hope, and wisdom from tūpuna.

As 2024 unfolds, Te Rau Hihiri remains dedicated to ensuring the Māori public service stays connected, celebrates calibre, shares creativity, and upholds Māori culture. With more events on the horizon, this rōpū continues to navigate change with a long-term perspective and an unwavering commitment to shaping a more empowered and connected Māori public sector for Aotearoa New Zealand.

Elena Higgison Ngāpuhi Trustee, Te Rau Hihiri

Elena has 20 years’ experience working across the government sector, leading policy and strategy development, and then driving execution. Elena’s passion and focus is the Māori economy. She specialises within the nexus of te ao Māori, technology, and government. It has meant she has gained a unique ability to act as a cultural translator and conduit between the government and a wide range of stakeholders.

Kara Nepe-Apatu

Ngāti Porou, Ngāi Tai Chair & Trustee, Te Rau Hihiri

Kara is a seasoned public servant with over 17 years’ experience predominantly focused on policy analysis, strategy development through to implementation, and cultural intelligence. She has a passion for imagining our future from a Māori lens and on the daily focuses of supporting the Māori economy, Māori Crown Relations, and exemplary application of He Ara Waiora.

Deb Te Kawa highlights IPANZ’s critical contributions to the free and frank advice discussion and links interested readers to the relevant material.

There has been considerable commentary and academic criticism about how public officials offer advice and whether they provide free and frank advice.

Some commentators claim the officials lack the incentives to offer truth to power. Others point to a golden age when administrative courage was apparently abundant. A few commentators point to the contested nature of ‘truthiness’, particularly the problem of poor-quality policy advice and the rareness of operational research and evaluative activity. Similarly, some academics point to the uneasy and contested space between the political authorising environment and the administrative branch. They call our attention to the potential politicisation of the public service.

They contend the defining feature of free and frank advice is that it is non-partisan: public servants serve ministers loyally and competently, irrespective of politics.

It is a real puzzle that there has been a lack of empirical work in Aotearoa New Zealand to define free and frank advice, its origins, and what institutions enable it. What is apparent, however, is the vital role the Institute of Public Administration New Zealand (IPANZ) has been playing in trying to shape this discourse for the past decade.

In 2012, IPANZ and the Institute for Governance and Policy Studies, as part of the Public Service Act 1912 centenary, invited Professor Emeritus Richard Mulgan to speak at a roundtable on the importance of free and frank advice.

Professor Mulgan covered the importance of free and frank advice in the public service as well as its challenges. He highlighted the role of public servants in providing impartial and transparent advice to ministers and the need for this advice to be based on factual accuracy and balanced judgement. He also highlighted the possible decline in the policy advisory functions within government bureaucracies and the increasing influence of ministerial advisers and media management. He called attention to the importance of protecting the role of senior public servants as trusted insiders and the crucial need for confidentiality in developing policy advice. He concluded that the primary challenge for free and frank advice in Aotearoa New Zealand is striking the balance between openness and confidentiality

to maintain the integrity and effectiveness of public service advice.

In covering the discussion roundtable, John Martin (2012), on behalf of IPANZ, highlighted the challenges faced by the public service in providing quality policy advice, the role of external sources of advice, the impact of the Official Information Act (OIA) on policy advice, the need for proactive advice, the tension between short-term and longterm policy considerations, and the stewardship role of the public service.

In 2015, IPANZ used John’s summary to design a free and frank advice seminar. Sir Michael Cullen opened the seminar. He reminded the participants that free and frank advice is part of a democracy and both a right and duty of the public service and needs to be done with common sense and respect.

Andrew Kibblewhite, the then Chief Executive of the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet, said in his presentation that trust between ministers and advisers created the space for free and frank advice. He also made it clear he did not think there had been an erosion or that there had been a golden age.

Dr Chris Eichbaum, the then Reader in Government at Victoria University of Wellington, gave an overview of free and frank advice and its role in Aotearoa New Zealand’s Westminster system of governance. He called for an inquiry into the current state of free and frank advice.

In her presentation, Dame Karen Poutasi, the former Chief Executive of the New Zealand Qualifications Authority and Director-General of Health, suggested officials needed to be mindful of context and be able to suit their style of giving free and frank advice to suit the particular needs of ministers.

In 2023, IPANZ and BusinessDesk surveyed public servants on the principles of public service, including free and frank advice. The survey found that most public servants believe they understand the concept of political neutrality and believe senior officials work hard to prevent partisan or politically inappropriate advice. It also found that most public servants believe that their senior leaders model the practice of giving free and frank advice. They also believe they provide their best advice without worrying about whether it is “popular or not”. But there is a split opinion on whether political advisers encourage free and frank advice or whether they are a barrier to providing the full range of options to ministers.

The last point has since been followed up by Dr Chris Eichbaum and Professor Richard Shaw in this journal’s June 2023 winter issue. In that article, Eichbaum and Shaw discussed the politicisation in the public service. They dug

deep into the survey, particularly regarding free and frank advice. They noted the concerns about providing free and frank advice and ministerial advisers’ influence on the public service’s neutrality. But they also noted the data suggests that in addition to political pressures, politicisation is also bubbling within public service departments and agencies. They highlight the importance of ongoing discussions about politicisation and the need for more empirical information to inform these discussions.

This article ends where it began. There is more heat than light in the discourse about free and frank advice. IPANZ has played an important leadership role in contributing to the discourse. But as Mulgan suggested in 2012 and Eichbaum and Shaw confirmed in 2023, there are some difficult conversations ahead.

Deb Te Kawa, Ngāti Porou, is a former public servant. She now runs her own consultancy while finishing her PhD on free and frank advice. Deb also lectures on public policy, public administration, and institutional performance at the Te Whare Wānanga o Waitaha | University of Canterbury. She also holds several governance roles, including on Te Rōpua Tapu i te Tika | Aotearoa Research Ethics Committee. Deb lives in Ōtautahi, Aotearoa New Zealand.

FURTHER READING AND IPANZ RESOURCES: www.ipanz.org.nz

Mulgan, Richard (2012). What future for free and frank advice? Address to IPANZ as part of centennial commemorations of the Public Service Act of 1912. Held 30 May 2012.

Martin, J (2012). Round Table on ‘Free and Frank Advice’ Summary of Discussion. Policy Quarterly, Vol 8, Issue 4, Page 11–15.

Kibblewhite, Andrew (2015). Free, frank and other fwords: Learning the policy road code. Speech notes for presentation to the IPANZ seminar held 12 August 2015.

Kibblewhite, Andrew and Boshier, Peter (2018). Free and Frank Advice and the Official Information Act: Balancing competing principles of good government. Policy Quarterly, Vol 14, Issue 2, Page 3–9.

Eichbaum, Chris (2015). Free and Frank Policy Advice: Some initial observations. PowerPoint presentation to the IPANZ seminar held 12 August 2015.

Poutasi, Karen (2015). Free and Frank Policy Advice Seminar. PowerPoint presentation to the IPANZ seminar held 12 August 2015.

Gill, Derek (2023). The state of the core state – Is the glass mainly full or partly empty? Public Sector, Vol 46, Issue 1, Pages 3–8.

Shaw, Richard and Eichbaum, Chris (2023). Politicisation in the New Zealand public service. Public Sector, Vol 46, Issue 2, Pages 3–7.

Finlayson explores the current state of affairs with civics education in Aotearoa New Zealand and asks how students, public servants, and all citizens can benefit from strengthening their knowledge on this subject.

The prospect of 16-year-old New Zealanders learning about civics at school and being able to vote does not thrill ACT Party leader David Seymour. In January, he said, “Combine voting at 16 with civics delivered by left-wing teacher unionists and you’ve got a recipe for cultural revolution, pitting indoctrinated socialist youth against the parents and taxpayers who pay their bills.”

Comments like this show the fault lines lurking beneath the seemingly benign topic of civics education in this country. That a strong civics education begets a robust democracy is a no-brainer. It’s the matter of how civics is delivered that seems to cause the most debate.

Civics advocacy: the Bronwyns

It’s worth noting here that what some refer to as ‘civics’ (and we’ll do so too for readerly ease) has two strands within the New Zealand Curriculum: ‘civics education’ covers civic processes (such as voting) and a citizen’s rights and duties; ‘citizenship education’ focuses on developing ‘active citizens’ who participate in society and understand how to effect change democratically.

Among those who have called for civics education to be better supported in this country are two distinguished Bronwyns: Dr Bronwyn Wood and Professor Bronwyn Hayward. Bronwyn Hayward is based in the Department of Political Science and International Relations, University of Canterbury. She’s also Convenor of the Civics, Citizenship & Political Literacy Working Group – an impressive crossdisciplinary range of thinkers gathered under the umbrella of the New Zealand Political Studies Association.

This working group seeks to support civics education for all students, find ways for political scientists to help the professional development of educators, and inform national conversations around these ideas. The discussion paper they presented to Parliament in 2018 (called Our Civic Future) helped galvanise the development of a new Civics and Citizenship Education resource, launched in 2021 within the Ministry of Education’s School Leavers’ Toolkit.

The other Bronwyn, Dr Wood, is Associate Professor of the School of Education, Te Herenga Waka –Victoria University of Wellington. She has spent many years researching best practice for teaching civics, is an adviser on the aforementioned working group, contributed to the School Leavers’ Toolkit resource, and was involved in the rewrite of the Social Sciences Curriculum. These Bronywns know their civic onions.

“Without citizenship education, the idea of a democratic government being of the people by the people and for the people just can’t be sustained.”

Some believe civics ought to be a compulsory subject in New Zealand schools. Bronwyn Wood says it’s not that it’s been absent from our curriculum – more that it’s dispersed and not neon-signposted. “In countries that do a formal civics curriculum, like Singapore and America, it’s easier to itemise. But what we do here within Social Studies is actually quite comparable; there’s also a bit in P.E., Health, and Science – the citizen science stuff – so it’s kind of scattered.”

Whether or not that content finds leverage within a given school or class is a moot point. “That’s the risk – it relies on the inspired teacher. We have one of the most open, unprescribed curriculums in the world, alongside countries like Scotland, Wales, Israel, and the Netherlands. We don’t know exactly what’s being taught because teachers have so much autonomy.”

A compulsory model is no guarantee of civics excellence, though. Bronwyn Wood says, “The countries which have a civics curriculum tend to do it in a deadly boring way that doesn’t engage kids.” She cites Singapore where students have to do 40 hours of community participation and

volunteering. “That can become very tokenistic rather than something holistic that’s embedded within the schooling experience.”

Our New Zealand model, says Bronwyn Wood, is more aspirational. “What we have is the potential to do civics in a really exciting way that’s highly engaging and memorable and might last a whole lifetime.”

Bronwyn Hayward has witnessed this sort of deep learning through a research project (funded by The Deep South) that she and others are conducting in Canterbury. Called Mana Rangatahi, it’s focused on growing indigenous youth participation in climate change decision-making. “When you work with students from a position of the strengths they bring from their communities you can really accelerate effective civic engagement.”

It’s the matter of how civics is delivered that seems to cause the most debate.

The problem with opt-in civics education is that some students fall through the gaps. This was evident the last time New Zealand took part in the International Citizenship and Civics Study in 2009. As well as achieving some of the highest scores for civics knowledge, many of our students also scored some of the lowest. No other country had

such a wide distribution of results. Some call this the ‘civic empowerment gap’. Bronwyn Hayward explains: “This gap happens when wealthy students learn to take advantage of all the democratic levers citizens have to make changes, while low income students are left further and further behind.”

The new Social Sciences Curriculum (Te Ao Tangata) only came out in full at the beginning of 2023 in draft form as part of Te Mātaiaho/the refreshed New Zealand Curriculum. There’s now a strong focus on social action and participation, structures of government, and comparisons with other countries. Bronwyn Wood says, “The new curriculum refresh is trying to provide more structured and intentional learning.” She adds that this refreshed curriculum has now gone back for review with the new government so, once again, there’s a period of flux.

The other issue is curriculum crowding. Bronwyn Wood says there’s so much good new history content that one of the unexpected casualties has been civics: “Teachers are scrambling to upskill on the new Aotearoa New Zealand histories and that’s meant that some of the civics learning has been dislodged. So now we have some schools only teaching the history and not the civics.”

Bronwyn Hayward hopes civics will get more traction once the history knowledge has bedded in. “I don’t think they’re either/ors. I think understanding the history of this place and its constitutional evolution is really essential for also understanding relationships between the Crown and Māori and the implications for all citizens of New Zealand.”

“What we have [in New Zealand] is the potential to do civics in a really exciting way that’s highly engaging and memorable and might last a whole lifetime.”

Bronwyn Wood thinks the call for more civics is generally concerned with political literacy. “It isn’t taught very well. That results in really patchy levels of knowledge. We see it in the students coming through university – some have no idea how MMP works or how you present a bill to Parliament.”

Add to this the fact that educators feel at risk talking about political issues in class and you have a perfect storm. “Teachers are often accused of lobbying for one particular party,” says Bronwyn Wood. “That’s when it gets a bit hairy. Those who aren’t particularly wired for teaching civics and citizenship will opt to teach something else.”

“Supporting teachers in how to have difficult conversations and scaffold the students’ learning is really important,” says Bronwyn Hayward. “Finding ways to increase professional development for teachers is as much of a priority as providing opportunities for civics and citizenship education and resources in schools.”

Bronwyn Wood says the Aotearoa Social Studies Educators’ Network has stepped up and done some of the work required to encourage teachers to put a bigger focus on citizenship. “But it’s asking a lot of teachers who primarily run that group to be the ones innovating.”

External groups have stepped into the breach to offer up some good teacher-buttressing. Bronwyn Hayward rates the efforts of the Electoral Commisson, which has put together an excellent resource called Your Voice, Your Choice to help teachers navigate the topic of voting and its associated terrain. “It reduces the risk for teachers because it gives them a neutral platform.”

Then there’s the likes of Generation Vote, a charitable trust founded by a group of University of Otago students in 2018. They say: “There is a growing recognition that civics needs to fit into the school curriculum. However,

this means teachers are required to develop new specialty knowledge – alongside all the other pressures of modern teaching environments.” Their mission is to alleviate some of that pressure by offering a “high-quality, non-partisan, and engaging” programme of workshops that they deliver in schools.

“I think lifelong civics learning for all of us would be really good.”

In an increasingly polarised society with its social media echo chambers and rampant disinformation, civics and citizenship education is vital, and not just for school students. Bronwyn Hayward says, “It’s important that we provide citizens of all ages with opportunities to practise democratic skills for engagement, listening, and effecting change. Without citizenship education, the idea of a democratic government being of the people by the people and for the people just can’t be sustained.”

Bronwyn Wood thinks we could all do with levelling up on our civics. “I take my teachers in training to Parliament and we have a session learning about parliamentary processes from the education team. I learn something new every time.

That kind of lesson could be pitched at new public servants without any shame.” (IPANZ is aware of this and offers a one-day Parliament in Practice course. This is aimed at people new to the public sector. In addition, IPANZ’s Public Sector 101 is an online self-directed learning course. Other webinars, seminars, networking opportunities and events on a range of topics relevant for public sector professionals are also available throughout the year. Visit the IPANZ website for more information on these.)

Efforts to nurture civics literacy both inside the classroom and beyond will safeguard and strengthen our democracy. “We can all keep learning here,” says Bronwyn Wood. “I think lifelong civics learning for all of us would be really good.”

Editor’s note: Representatives from the Ministry of Education Te Tāhuhu o te Mātauranga were approached for inclusion in this article, but no response was gained.

Based on Dunedin’s Otago Peninsula, Claire Finlayson has been a freelance writer for the last two decades. During that time she's written for a wide variety of publications, covering everything from forensic dentists to chocolatiers, cardiologists to spud farmers, Kombi-obsessives to crime writers. She was once Assistant Curator of Pictures at the Hocken Collections, wrote a book on self-portraits by New Zealand artists, did a stint as Programme Director for Dunedin Writers & Readers Festival, judged the fiction category of the 2021 Ockham New Zealand Book Awards, and produced a couple of kids.

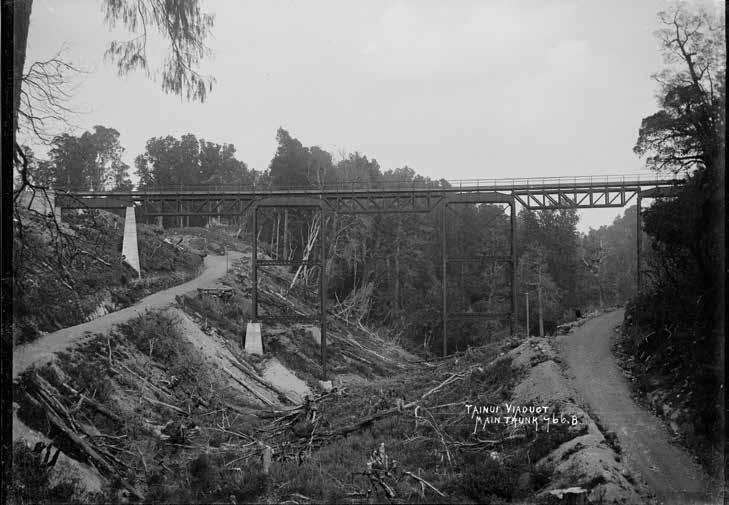

Jim McAloon, Professor of History at Te Herenga Waka –Victoria University of Wellington, provides a summary of the history of the Ministry of Works, once described as the country’s first super-department.

Infrastructure is much discussed, whether it be water, rail, ferries, or roads. Apart from the problems of funding, what is needed and what is desirable, appropriate ways of organising and managing infrastructure are debated. There are sometimes calls to ‘bring back the Ministry of Works’, which planned, designed, and built public infrastructure for over a century from 1870. It could be described as this country’s first super-department.

From each to their own to mass expansion

Before 1870 the governments of each province were responsible for their own public works. As the provinces varied in their resources, so did what they could afford. This was one reason why, in 1870, a centralised Department of Public Works was established. The dominant politician of the decade, Julius Vogel, believed that centralisation meant efficiency and rational prioritisation. It also meant that the central government would be better placed to borrow the large sums needed for development – private capital being inadequate for the task. Vogel had another agenda, too: rapid infrastructure development would mean a rapid increase in the settler population and the marginalisation of Māori without continuing warfare.

The 1870s were a spectacular decade for settler New Zealand. The railway from Christchurch to Invercargill was built in a decade, although railway construction in the North Island was slower, depending on the slow erosion of Māori landholding. Roads and harbours expanded, as did settler farming and trade. The settler population doubled to half a million, while poverty and land loss took their toll on Māori. Arguably the decade was the foundation of a New Zealand that lasted for a long time.

Recession and austerity slowed the process in the 1880s, but in the mid-1890s the Liberal government returned

to borrowing for development. Completing the North Island Main Trunk Line was a priority. The plaque that commemorates the final spike, in 1908, is a monument to settler expansion as much as to engineering excellence. Other projects also progressed. The period was notable for many fine public buildings, a monument to the self-confidence of the state. Official predilections for state-funded and directed projects were reinforced by the failure of the private sector to deliver South Island railway expansion, from Nelson and across the Alps from Christchurch to Greymouth. Government took over such projects.

Not that the Public Works Department always had a charmed life. Especially in times of economic downturn, some business and conservative lobbyists advocated that it be closed, or much reduced in its functions. While the years after 1918 saw the beginning of hydroelectric power, the Great Depression and savage cuts to public spending severely compromised the state’s infrastructure capacity.

The first Labour government (1935–49) was committed to restoring public infrastructure. This met several objectives, especially economic modernisation and maintaining demand and employment by increased investment. World War Two interrupted progress, and by the late 1940s there was a large backlog. Housing shortages were notorious. Electricity supply was so constrained that blackouts were frequent. Moreover, government was committed to increasing population both by immigration and by encouraging family formation; that, in turn, required new schools, new hospitals, and so on.

From 1949, National governments broadly agreed with commitments to extensive public investment. Through the 1950s and 1960s the Ministry of Works achieved international recognition for its engineering expertise, not least in major hydro projects along the Waikato, Clutha, and Waitaki watersheds (a Cook Strait cable was for a long time unproven). By the early 1970s the Ministry of Works and Development (as it became) was apparently at the height of its powers.

Beneath the surface, though, there were challenges. In the late 1950s a Labour government entered into plans to construct a hydroelectricity plant at Lake Manapouri, to power a proposed aluminium smelter at Bluff. Manapouri is often seen as the beginning of a modern environmental

movement, which increasingly challenged developmental assumptions. After the Middle East War in October 1973 and the first oil shock, economic recession became the order of the day, and public finances were constrained in an inflationary environment. Population growth had slowed, and by the end of the decade there was talk of an ‘electricity surplus’.

That ‘surplus’, and the second oil shock in 1979, were the background to the Muldoon government’s ‘Think Big’ plans. The intention was to use electricity and natural gas to support energy-intensive export, or import-substituting industries. It was controversial then and since. Perhaps the most balanced assessment is that some of the projects were worthwhile, but that too much was done too quickly, with inadequate preparation, and – unfortunately for Muldoon –just as the cost of borrowing soared due to the United States central bank’s monetary policy.

Think Big reinforced an emerging scepticism among a

younger generation of economists, politicians, and public servants, about the activist, developmental state that had prevailed since 1935 (indeed, in some incarnations, since 1870). New directions in economic thought emphasised deregulation, private enterprise, and market-led policies. The Ministry of Works was susceptible to both this line of thinking and to environmental critiques, as well as to increasing awareness of the consequences for Māori of development policies over many decades. The fourth Labour government abolished it in 1988, as part of its comprehensive restructuring of the state services.

Whether the 1870–1988 model can be resurrected is an open question, and there are many debates about how to provide infrastructure into the future – not least about funding. Aside from that, the Ministry’s impact on New Zealand society, economy, and landscape was profound.

Jim McAloon is a professor of history at Te Herenga Waka – Victoria University of Wellington. He acknowledges the work of two recent MA graduates, Michael Hall and Gillian Tompsett, whose theses dealt with aspects of the Ministry’s history.

Chelsea Grootveld, Deputy Chair and Board Trustee at Iti Kōpara, talks about public governance and recent developments to address gaps.

Public governance in Aotearoa New Zealand refers to the system by which the government manages and regulates public affairs to serve the interests of its citizens. It encompasses a set of principles, processes, and institutions designed to ensure transparency, accountability, and efficiency in decision-making and service delivery. New Zealand’s approach to public governance is characterised by its commitment to democratic values, including citizen participation, rule of law, and respect for human rights.

While public governance is generally characterised by transparency and accountability, some areas still require attention. One notable aspect is the need for greater leadership skills and greater diversity and inclusion in decision-making processes, ensuring that voices from tangata whenua and all segments of society are heard. Strengthening leadership to uphold integrity standards can only serve to enhance public trust.

WHY IS SOMETHING DIFFERENT NEEDED?

Being a director on a Crown entity board requires a unique skillset and understanding. The Crown entity governance context differs from commercial, non-government, and voluntary sectors.

There appears to be a gap in Crown entity-specific governance training for aspiring, new, and experienced Crown entity directors in Aotearoa. Existing governance courses offered by the Institute of Directors, Governance Aotearoa, and Community Governance Aotearoa place a particular focus on the Crown entity context. Iti Kōpara aims to focus on leaders and directors by offering quality compentency development and refresher training for public sector governance boards.

Created in 2023, Iti Kōpara – Public Governance Aotearoa – is an independent registered charitable trust, established by a group of experienced public sector directors, with support from Tangata Whenua, Te Kawa Mataaho: Public Service Commission, New Zealand Government ministries and agencies, philanthropists, and Te Herenga Waka – Victoria University of Wellington. We support Crown entity directors to thrive as leaders and decision-makers in this important and dynamic environment. We are proud of the hundreds of thousands of public servants who work hard every day to deliver programmes and services to communities across Aotearoa.

Our kaupapa is the pursuit of public governance excellence. Iti Kōpara aims to achieve this through supporting

boards of directors to reflect the diversity of society and be equipped to respond to a changing and increasingly complex operating environment. We do this through the development and delivery of quality competency development and refresher training for public sector governance boards.

Our vision is reflected in the whakataukī “He iti kōpara pioi ana te tihi o te kahikatea” – “the small bell bird who aspires to reach the topmost branch of the kahikatea tree will set it swaying”.

“He iti kōpara pioi ana te tihi o te kahikatea” – “the small bell bird who aspires to reach the topmost branch of the kahikatea tree will set it swaying”.

The whakataukī is about striving for the uppermost reaches of one’s potential. It speaks to perseverance and capability. This is what the Trust is endeavouring to instil in current and aspiring public sector governors for the benefit of all Aotearoa New Zealand.

The course we have designed – “Mā te kahukura ka rere te manu” – refers to adorning the bird with contemporary governance knowledge and enabling it to fly to the highest peaks. In this context, ‘kahukura’ refers to the pursuit of governance excellence through sharing purposeful governance knowledge, creating new knowledge and building relationships between course facilitators, experienced guest practitioners, and participants.

Delivered over four days, the 2023 pilot courses received overwhelmingly positive feedback from participants who enjoyed the quality and calibre of practitioners and facilitators. These included current and former Crown entity directors and chairs, iwi leaders, ministers of the Crown, chief executives, deputy secretaries, the Controller and Auditor General, and professors.

The opportunity to connect with guest practitioners is a special feature of the course. Through this, participants learn practical tips, hear strategic insights, and discuss complex Crown entity governance issues. Our guest practitioners share what it takes to be a purposeful leader and director on a contemporary Crown entity board and the personal and professional benefits of working in a complex, nuanced, and exciting environment.

We support participants in identifying the defining characteristics of governance in the public sector,

particularly the machinery of government and the specific challenges and practical realities for boards operating in this context, while maintaining quality and responsive relationships that best serve the public.

The topics covered in our course include financial and performance accountability, Board culture, strategic risks and opportunities, Māori-Crown relationships, health and safety, climate change, and demographic disruption. The content is revised and refreshed in response to the changing political and social realities to ensure relevancy.

We encourage experienced, new, and aspiring directors to apply for our courses and aim for a 70:20:10 (experienced: new: aspiring) split of participants to ensure there is a balance of tuakana-teina (older-younger) in each cohort.

More information about the guest practitioners and others involved in the course creation can be found on our website. You can also register your interest to attend the Mā te kahukura ka rere te manu course at this website.

Chelsea (Ngai Tai, Ngāti Porou, Whānau-a-Apanui, Whakatōhea, Te Arawa) has an extensive background in education research, policy, and evaluation. She completed her doctoral studies in 2013, gaining a PhD in Education, at Te Herenga Waka – Victoria University of Wellington and started her own indigenous research and evaluation company.

Chelsea joined the High Performance Sport New Zealand Board in 2019. She is a member of the Institute of Directors and Governance New Zealand, Director of CORE Education Limited, Chair of JR McKenzie Trust, Board member of International Funders For Indigenous Peoples, former Chair of Hato Pāora College Board of Trustees, and former Future Director of the Sport New Zealand Board. Chelsea was a Women in Governance award winner in 2019.

• July – 15, 16, 30 & 31 Te Whanganui-a-Tara Wellington

• September/October – 16, 17, 30 & 1 Te Whanganui-aTara Wellington

The Ombudsman has created a new online learning platform for people in the public sector who deal with official information or want to know more about it.

Chief Ombudsman Peter Boshier says the main aim of the platform – Te Puna Mātauranga – is to help staff at councils and other public sector agencies develop their official information practice skills.

“I’ve been talking to agencies for some time about brushing up on their understanding of the Official Information Act [OIA] and Local Government Official Information and Meetings Act [LGOIMA]. I thought I’d do something practical to help.”

Peter says there are staff and managers from around 4,000 organisations, including central government, local councils, and school boards, who can make good use of Te Puna Mātauranga.

“There are no course fees or subscriptions. You will just need to head to our website and click on the link which will take you through to Te Puna Mātauranga.”

The platform is designed to be easy to use and allows learners to work at their own pace.

There are three courses available, The OIA for Ministers and Agencies, The LGOIMA for Local Government Agencies, and Managing Unreasonable Complainant Conduct.

“Each course is divided into several online modules so you don’t have to do everything at once.”

The OIA and LGOIMA courses offer an overview of the legislation and what agencies need to do when they’re managing official information requests.

Peter says the Unreasonable Complainant Conduct course is being offered due to demand.

“Agencies often ask me about dealing with complainants who behave in a challenging way. This course provides some guiding principles and strategies to help handle this behaviour.

“After finishing each course, you can download a Certificate of Completion. It’s proof of a job well done.”

Peter says while three courses are offered now, more courses will be added in the future.

“We provide a survey at the end of each course for people to provide their feedback.”

Peter says Te Puna Mātauranga offers a solid foundation but if agencies want to learn more about OIA or LGOIMA practice, they can reach out to the Ombudsman for targeted learning.

“I have a dedicated Learning and Agency Development Team. They offer training in person or provide online workshops. The team is also available to give general advice on official information issues.”

Zaira Najam reviews a Westminster Tradition podcast episode and the book Towards a Grammar of Race edited by Arcia Tecun, Lana Lopesi, and Anisha Sankar.

The podcast episode “Mr Bates v Post Office – shades of Robodebt?” by The Westminster Tradition (hosted by Caroline Croser-Barlow) highlights challenges in large government organisations, emphasising the inherent inertia that fosters inhuman and self-protective structures. Using the United Kingdom’s Post Office fiasco as a case study, the podcast underscores the impact of system failures persisting for over 20 years, penalising postmasters due to a technical error during the shift to digital recording of financial transactions. This lapse in accountability, monitoring, transparency, and ownership erodes public trust.

A crucial recommendation is realigning government performance metrics with the primary objective of serving people, irrespective of class, creed, race, ethnicity, or origin. This people-centric approach prioritises fairness, justice, and inclusivity in policies and systems.

Addressing these challenges involves eliminating aggressive legislative tactics, mitigating cultural biases, and establishing ongoing scrutiny mechanisms. Proactive monitoring and evaluation play a crucial role in identifying and rectifying issues before escalation, fostering a more accountable and responsive government.