Right Relations

THE VIEW FROM THE SHORE • THE RIVER IN OUR BONES SACRED SALMON • CHOOSE SOLIDARITY, NOT GUILT • AN ETHICS OF ACCOUNTABILITY

From the Editor

Many Catholics are familiar with the doctrine of discovery—15th-century papal bulls that provided European nations with the legal and religious authority to invade and possess non-Christian lands. By planting its flag on this “new” land, the doctrines said, Christian European nations acquired not only sovereign rights over that land, but also the right to govern any non-Christian people on it.1

What many white U.S. Catholics are only beginning to grapple with, however, is the fact that the legacy of the doctrine of discovery is alive and well. It is codified into U.S. property law: The 1823 Supreme Court case Johnson v. Mcintosh effectively ruled that Native people did not have the right to own property.2 That case was quoted as recently as 2005, in Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsberg’s majority opinion writing in City of Sherrill v. Oneida Indian Nation of New York.3

As JoDe Goudy, former chairman of the Yakima Tribal Council and the founder and owner of Redthought, points out in this issue of A Matter of Spirit, “This system of domination used by the Roman Catholic Church centuries ago to justify their dominion is still being used by the U.S. Supreme Court today. This is the legal foundation from which the United States has continuously asserted its claimed right of domination over all the land, territories, waters, animals, plants, and those they deem to be heathens and infidels.”

The articles in this issue grapple with the lasting legacy of the doctrine of discovery—both in U.S. society at large and in the U.S. Catholic Church. First, both Goudy and Ione Jones, in their articles, tell the story of the doctrine of discovery and its impacts “from the shore,” as Goudy puts it. “I am standing next to my ancestors in 1491, looking at the ships coming toward us, as I understand the totality of the impact this way of thought has had,” he tells me in an interview. One way Catholics can work to make reparations for these centuries of domination and the breakdown of right relationships with both the land and other people

1 Sal Sahme, “Lies of Discovery,” Oregon Humanities, April 27, 2021, https://oregonhumanities.org/rll/magazine/possession-spring-2021/ lies-of-discovery/.

2 “1823: Supreme Court rules American Indians do not own land,” Native Voices, National Institutes of Health, Accessed June 24, 2024, https://www.nlm.nih.gov/nativevoices/timeline/271.html.

3 Dana Lloyd, “City of Sherrill v. Oneida Indian Nation of New York,” Doctrine of Discovery, October 19, 2022, https://doctrineofdiscovery. org/sherrill-v-oneida-opinion-of-the-court/.

“ In practice, land justice means centering people and communities who have historically been deprived of their right to land and territory.”

that Goudy talks about in his interview is through involvement in movements for land justice and Indigenous sovereignty.

As Jones writes, “Indigenous sovereignty is more than a legal or political concept; it is a way of life rooted in Indigenous knowledge, values, and relationships with the land.” In practice, land justice means centering people and communities who have historically been deprived of their right to land and territory. It can mean taking part in a canoe journey with Jones’ organization, KHIMSTONIK; supporting IPJC’s Sacred Salmon campaign (see pages 8–9); making monetary reparations to Indigenous tribes through a program like Real Rent Duwamish4; or otherwise working to build an ethic of repair in our relationships with Native peoples.

The other writers in this issue explore how Catholics are wrestling with the lasting impacts of the doctrine of discovery and their own relationship to U.S. land and what the beginning steps to righting relationships might look like. In “An Ethics of Accountability,” Elisha Chi places movements for land justice within the context of Catholic social teaching and offers some suggestions for communities that already acknowledge their place on Indigenous land but seek to go further. In “Choose Solidarity, Not Guilt,” Tess Gallagher Clancy wrestles with her own complicity in the destruction of Native communities and offers a model for how to both love the land where your ancestors have lived and died while working toward restoring right relationships with those who originally lived there.

The articles in this issue ask readers to acknowledge their own involvement in the doctrine of discovery and colonization and provide suggestions for how to start doing the work of righting the relationships that have been broken for centuries. I hope that everyone is both challenged and inspired to deepen their involvement in, as Goudy says, “[overcoming] the greatest system of domination that’s ever existed and [creating] something better.”

—Emily Sanna, Editor

4 Real Rent Duwamish. Accessed June 24, 2024, http://www. casadecalexico.com/band.https://www.realrentduwamish.org/.

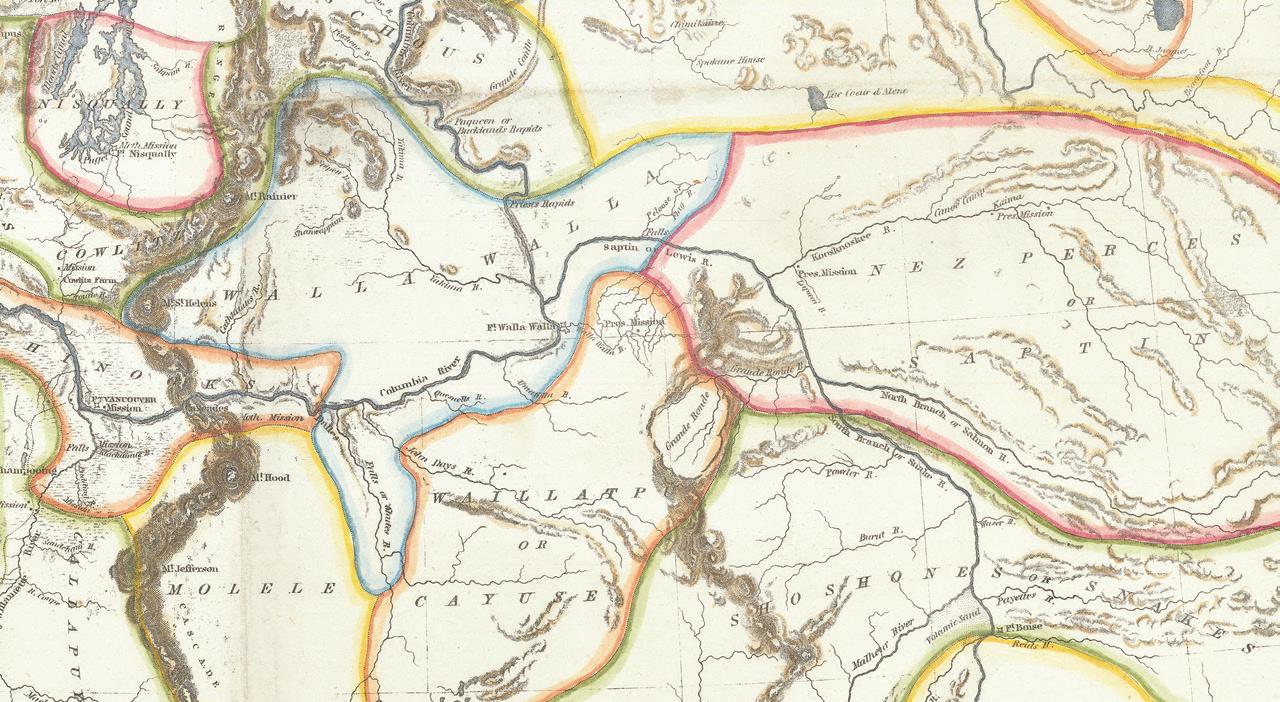

Palouse Falls, Snake River, WA

The View from the Shore

JoDe Goudy is a former chairman of the Yakama Tribal Council and the founder and owner of Redthought, a Nativeled organization that seeks to educate and advocate around the legacy of the doctrine of Christian discovery. A Matter of Spirit editor Emily Sanna spoke to Goudy about movements for land justice and the enduring legacy of the doctrine of Christian discovery. What follows is a shortened version of their conversation. To read the full conversation visit the digital version: https://bit.ly/a-view-from-the-shore

When we talk about Indigenous sovereignty, what does that mean and what does that look like?

You have to be careful with the words you utilize: Oftentimes words like Indigenous and sovereignty are accepted as positive. But I always tell people, “Don’t call me Indigenous” because of the etymology and the forums by which certain entities and organizations use the word.

Most people are aware of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. The UN defines the word Indigenous as a people whose land was taken by other people. It means a conquered person. Sovereignty is another unique word when you look at the etymology. For the most part, it is interpreted as a positive term. But when you attach the word to its political and legal history, sovereignty is actually a euphemism for or a different way of saying “dominated.” So, I’m not Indigenous and I’m not really sovereign.

Steve Newcomb is a Shawnee-Lenape scholar who has been studying and writing about the ways a system of domination has manifested and sustained itself throughout time. He has always helped me remain extremely mindful of what type of words I utilize to communicate. Instead of Indigenous, he prefers the term Original Free Nations. This term reflects how our peoples collectively existed from 1491 going back in time to our creation. This perspective is quite different than the narrative that so-called “discovery” happened, all these visitors arrived, and then all of a sudden we’re in today’s time.

It’s easy for people to attach themselves to expressions or words without delving deeper into what exactly they are saying. I just ask any of your readers to be mindful that if you use a word to identify someone, you should take it upon yourself to understand the meaning of the words you are using.

That’s a challenge for everybody. Most Native people, Original Free Nations, or Indigenous people—whatever name they go by—feel that being “Indigenous” is an honorable thing. If someone says they want to uphold their sovereignty, they say, “Well, that’s valid and I appreciate that.” But the work I do delves into the details and nuances with regard to how reality manifests through thoughts and language.

It’s both really challenging and important to recognize that this history of European colonization is so wrapped up in even the very well-meaning language we use to talk about land justice. This brings me to our next question, which is that you mentioned the doctrine of Christian discovery. Can you define what that is?

The doctrine of Christian discovery can be dated back to 15thand 16th-century popes who issued specific papal bulls or edicts that were, I guess you could say, the holy marching orders to justify the so-called “discovery” that was happening throughout the world.

These edicts included some very detrimental and terrible language regarding European people’s rights to invade, conquer, diminish, and subdue lands that were deemed “new” or, as they specifically list in the edicts, not ruled by any Christian prince.

Even though our ancestors lived on the land, and various Native and Original Free Nations existed in every part of the

JoDe Goudy, Yakama Na tion and Vice-Chair of Se’Si’Le

world where these acts of discovery had happened, these edicts justified their conquest by deeming them to be heathens, infidels, and subhuman because they were not Christian. There was this holy justification for exerting these acts of discovery.

The founding fathers were well aware of this type of thought when they wrote the Declaration of Independence and formed the United States. And in 1823, the Supreme Court took it upon itself to enshrine this doctrine into U.S. law. There was a dispute over who had ultimate jurisdiction over land that might be considered as belonging to the Original Free Nations. Justice John Marshall essentially said that the United States had inherited the doctrine of Christian discovery as a holy right to exert dominion upon all lands.

It’s easy to look back today and say, “OK, did that really happen?” The first time I read it, I thought it was fake or some sort of mock case. But this case is reality, and it is the foundation of property law in the United States. It also becomes the foundation of what is identified as federal Indian law. This system of domination used by the Roman Catholic Church centuries ago to justify their dominion is still being used by the U.S. Supreme Court today. This is the legal foundation from which the United States has continuously asserted its claimed right of domination over all the land, territories, waters, animals, plants, and those they deem to be heathens and infidels. It’s never been overturned: The United States still identifies myself and all other Original Free Nations people as heathens, as infidels.

I would encourage your readers to seek out and learn about the doctrine of Christian discovery from other Original Free Nations people: Our uniqueness is that our viewpoint is from the shore. I am standing next to my ancestors in 1491, looking at the ships coming toward us, as I understand the totality of the impact this way of thought has had. Others who try to identify the doctrine of Christian discovery are on the ships.

You mentioned your advocacy work. Can you talk a little bit about what that looks like for you?

I’ve always been an advocate of our people, our ways of life, and our physical, mental, and spiritual well-being and tried to manifest more right and respectful outcomes in our relationship with the natural world. I served as an elected official for the Yakama Nation for a few years.

Then I became aware of all the work surrounding awareness of the doctrine of Christian discovery and advocated with our council to help all our membership become aware of this history and what to do about it.

I believe that understanding the legacy of the doctrine of Christian discovery is one of the most foundational issues when it comes to fighting the good fight. It implicates everybody— every Christian, every Muslim, every Original Free Nations person. This system continues to manifest in detrimental outcomes that affect the overall world.

This issue is very important, but I also have my own foundational relationship with the Creator, which is grounded in my

traditional and ceremonial following of my people’s way of life. And because I carry this foundation, in my advocacy I try to do my work in a spirit of love and light and to advocate free, independent, and coherent thought.

“ I am standing next to my ancestors in 1491, looking at the ships coming toward us, as I understand the totality of the impact this way of thought has had.”

When I left the Council, I asked myself where I could have a right and respectful discussion grounded in integrity. I didn’t know anywhere in this world I could do that. That’s one of the reasons why I founded Redthought. Redthought is a forum where Native and Original Free Nations people do historical analysis on the doctrine of Christian discovery and highlight points in time throughout history to peel back the layers that make it hard for people to see that this is a system of domination.

What do you want Catholics to know about the legacy of the doctrine of Christian discovery?

I actually interacted with Pope Francis myself as part of a delegation in 2016; I called out the history of the doctrines of Christian discovery and asked the pope and Vatican to formally and ceremonially revoke the historical documents in question. And, of course, last year the Vatican did release a two-page statement repudiating the doctrines of discovery. But a repudiation and words are one thing; we still have the foundational documents by which nations manifest their continued claims to domination. The collective expression from the Vatican has been a song and dance of smoke and mirrors.

Obviously, it’s very complicated. But at the end of the day, it’s also very simple: How in the name of Jesus Christ can you advocate for this type of system? How can Christians allow it to exist? If you weren’t aware that it existed, but now you have learned, how can you do nothing about it? Those are my questions to every Christian who becomes aware of this history leading up to our present moment.

In my work, we try to use the context of right and respectful relations to talk about this type of advocacy. We ask people simple questions of identity that perhaps have very complicated answers: Who are you? Where do you come from? Where are you going? What is? What isn’t? And why?

We utilize these questions as tools to have people become aware of their identity and then hopefully guide them to engage in respectful conversations with others. Because when we talk about the doctrine of Christian discovery, we’re not talking about something small. If you interpret it from the perspective

of myself and others standing next to our ancestors on the shore, we are looking at the greatest system of domination that’s every existed in the known history of humanity—not only the domination of Original Free Nations throughout the world, but of the natural world as well. The only way you can even begin to think about this is if integrity is guiding you, if the intent is to build right and respectful relations.

Very few members of society, no matter who they are, what faith they are, what type of life they have, agree with how the doctrine of Christian discovery has become so interwoven with our laws and practices today.

I hear you saying that this isn’t just a matter of legal advocacy—it’s a spiritual issue that reflects your relationship with God and creation. Do you think Catholics often recognize how much these are intertwined?

We all generally understand that there’s a significant amount of darkness in the world’s history. But when you bring that awareness forward, it can challenge people’s understanding of practical reality. People can have a trauma response—where they either want to fight against the truth, run from it, or shut down. When this history affects the foundational questions of your identity, then it can become hard to navigate through it, to develop a right and respectful relationship with yourself.

When I asked my Christian brothers and sisters that first question—“Who are you?”—they often tell me something like, “I am a child of God.” That’s beautiful. When they ask me the same question, my answer is, “I am of creation.” That becomes the foundation for how we identify with one another.

If you identify yourself as a child of God, what are the divine instructions that can give you guidance for how to navigate the pathway of this history—how your identity has been, whether knowingly or unknowingly, attached to this history? How can your relationship with God help you figure out what to do about

the legacy of this system of domination now that you know about it?

This is one of the biggest challenges for the future—figuring out where to go from here. We don’t have a playbook to look for that somehow teaches humanity how to overcome the greatest system of domination that’s ever existed and create something better. We literally have to develop the thoughts and outcomes through communication and navigating these issues ourselves. And that requires acting with integrity and in the pursuit of right and respectful relationships.

If other Christians become aware of the ongoing work, hopefully this creates a foundational base that become a beacon, continually expressing to other Christians the right and respectful way to navigate this legacy.

If we want a better future, we have to answer these questions. Because they affect not just Native or Original Free Nations people who are still struggling to exist today; they affect everyone, of all walks of life, all backgrounds, all faiths. If we don’t correct this, then our future generations and sustained existence is going to face some very great challenges. If society wants a preview of what’s coming for everybody, take a look at the Native nations and what we have endured. Everyone will be affected; we are just further along in interacting with this system.

Is there anything else you want to make sure our readers know about the legacy of the doctrine of Christian discovery and how to work toward a more just paradigm?

I’ve worked with faith groups and churches where the reaction has kind of been, “Thank you very much for bringing this to our attention. We’ve got it from here. This is ours to fix. Oh, and by the way, it’s time for you to heal, so you have our permission to do that. Thank you.”

This reaction is very disheartening and disrespectful. And so, if there are Catholic groups that begin to take proactive steps in the spirit of right and respectful relations, such a mindset does a great disservice to the spiritual, physical, and mental well-being of our people. The Native nations are the collective original victims of this system of domination, and we need to be part of the ongoing conversations about identity formation. I would ask that there be a pathway toward fixing this ongoing system of domination that begins with righting the extremely wrong and disrespectful relationship between the United States and Native nations.

We never say that a relationship is over. People ask me where all this work is going. And there are points of reference that people might try to identify as destinations, but the work is the journey. The journey is the work. The continued pursuit of identifying what is right and respectful and then manifesting this into the physical world is the work.

JoDe Goudy speaks with Pope Francis during a 2016 visit to Rome to discuss the doctrine of Christian discovery and its legacy.

The River in Our Bones:

THE STORY OF THE LOWER SNAKE RIVER PALOUSE

BY IONE JONES

My name is ILL-LAH-WAH-LITZ-TUN-MYE, which translates to “Lady who does tasks quickly.” I am an enrolled member of the Confederated Tribes and Bands of Yakama Nation and a lineal descendant of the WOW-YICK-MA NAH-KHEE-UM NU-SHWA, the People from Lower Snake River Palouse. Our villages were vast and wide along the rivers known as Wawáwi, Alamótin, Palús, Wawyuk’má, and Samyúya. Horses ran freely from both sides of the Snake River northward and across the Horse Heaven Hills to Wáwnashee (Priest Rapids).

As the executive director and president of KHIMSTONIK, a nonprofit organization named after my kuthla (my grandmother Mary Jim Chapman), I am deeply committed to understanding and addressing the ongoing disparities arising from centuries of cultural appropriation and land thefts.

Colonialism has left an indelible mark on all Indigenous communities, including my own family. Generations of trauma stemming from displacement, dispossession, and systemic marginalization have shaped our collective history. As I reflect on what it means to be of the WOW-YICK-MA NAH-KHEE-UM NU-SHWA, I am compelled to share some of our stories about how colonialism has impacted my family and articulate what Indigenous sovereignty means to me.

The Palouse People, a distinct band of Sahaptin-speaking people, have long inhabited the confluence of Oregon, Washington, and Idaho. Our family’s land claims differ to others in the area due to our relatives CHO-WAWA-TYET (Indian Jim), XHAL-UCH WACH-OM-KYE (Wolf Necklace),

“Our photos sit on book covers, and our testimony serve politicians, but our true experience is still made invisible.”

AL-LI-LUYA (Thomas Jim), and XUMTU-ST’-AKI (Harry Jim), all of whom received land patents under the Homestead Act of 1862. However, in 1959 the U.S. Army Corps instituted eminent domain, forcing our family off our ancestral lands and flooding our cemeteries to build the Lower Snake River Dams, a loss that severed cultural and spiritual ties to the land and that echoes through subsequent generations.

My family has continued to maintain a deep relationship to this land. We have also been historically willing to help those who are interested in our knowledge and the essential information we have about the land and our history. We have collaborated with people for centuries, but the result has not been visibility and empowerment. Instead, over and over our history and expertise has been buried in citations and footnotes for research and development by educational and governmental representatives. Our photos sit on book covers, and our testimony serve politicians, but our true experience is still made invisible. That’s how best to describe the existence of our people, who have survived and persisted despite the continuing adversity and fundamental injuries we have suffered through colonialism.

Nevertheless, our people’s story is one of resistance and renewal. In 2023, KHIMSTONIK hosted its inaugural healing canoe journey along the Lower Snake River, reconnecting descendants and others in the community with the cultural and environmental heritage of the Lower Snake River Palouse.

This journey, centered around canoes, planting medicines and foods, and fostering connections with the Snake River, is a vital component of reclaiming Indigenous sovereignty. We pass down songs, language, and roles to younger generations, ensuring the preservation of Indigenous knowledge and traditions.

Photo © Gloria Pancrazi

Moreover, it empowers communities to address challenges collectively, fostering solidarity among Indigenous and nonIndigenous allies striving for Indigenous sovereignty.

In 2024, we organized planting activities, plant walks, and shared cultural and traditional knowledge during our journey from Perry to Paige, Washington, in collaboration with nonIndigenous allies and neighboring sovereign tribal communities, including the Caretakers of the Lands from the Wallulla village, Kalispel Canoe Family, the Spokane Canoe Family, Puyallup Tribal Canoe Family, and members of the Wanapum Village.

All this work is to reclaim our stories and way of life. Our objective is to use our deep knowledge to support resilience in our environment, health, and cultural efforts. Strengthening our ties with tribes along the rivers and basins is integral to our decolonization mission, undoing the damage caused by invasive species left behind by those who sought to disrupt human and ecological relations. By planting seeds that stabilize riverbanks and eventually nourish salmon populations struggling upstream, we contribute to the restoration of both land and culture. Our unique position allows us to facilitate a deeper understanding of original cultures, lands, waters, and communities, fostering a commitment to tribal individuals living outside reservation boundaries through land restoration initiatives. We unwind the tactics and false narratives that the U.S. government has used to fracture our experience and our relationships to each other and the land.

In addition to the canoe journeys, we are also currently collaborating with the descendants of the Original Peoples from surrounding tribal communities in southeast Washington. We advocate for tribal members residing outside federally recognized reservations, whose sovereign territories are just

beyond these boundaries. Our aim is to offer educational opportunities to the wider community, especially to underserved tribal villages and individuals who have transitioned away from reservation life (either by force or choice).

Our collaboration extends to dedicated non-Indigenous community members and organizations to deepen our work within the state and federal government, ensuring the vital input of the Original People is acknowledged. Our vision extends beyond our current efforts; we aim to broaden our impact nationwide, focusing on regions that are Indigenous homelands but have since been overrun by forced development, lacking the crucial input of the Original Peoples.

Indigenous sovereignty is more than a legal or political concept; it is a way of life rooted in Indigenous knowledge, values, and relationships with the land. It honors the interconnectedness of all living beings and recognizes our responsibilities as stewards of the Earth. Our story underscores the ongoing struggle for Indigenous sovereignty, as we confront the challenges of the present and strive towards a more just and equitable future. Through our commitment to protecting our lands and ways of life, we offer a powerful example to others hoping to reclaim their rightful place as stewards of the land. As we stand in solidarity for collective liberation, let us draw strength from the stories of the land and work towards a future built on respect for all.

Ione Jones is an enrolled member of the Confederated Tribes and Bands of Yakama Nation and lineal descendant of WOW-YICK-MA NAH-KHEE-UM NU-SHWA, the Fishhook Bend Snake River Renegade Palouse. She is an accountant and real estate broker (inactive) with years of experience in working for tribal governments.

Above: 1842 Oregon Territory map by U.S. Ex. Charles Wilkes illustrates how populated the region was before Europeans and Americans came up the Columbia River. Page 6: Planting native plants. Right: Ione Jones

CAMPAIGN

“Our bodies are made of the elements of the Earth.

PURPOSE: Gather the faith community to stand alongside Indigenous communities of the Northwest to protect Indigenous sovereignty, amplify tribal-led land return and ecosystem restoration, Native cultural revitalization, and active decolonization of land, water, and air resources, in the hope to restore and honor Indigenous wisdoms and environmental expertise.

VISION: IPJC envisions creating a network of faith-based leaders that support Indigenous tribal leaders as co-managers of natural resources, per federal treaties, and parishioners and youth in being in right relationship with all of Creation. All of this is inspired and modeled according to the concrete expertise regarding salmon, ecosystem recovery, and dam removal that Indigenous communities hold, as well as a rightful sharing of the historical environmental legacy in our region.

Goals:

1. As a covenant people, restore and protect treaty rights particularly as they relate to access to salmon and traditional fishing grounds.

2. Honestly and authentically name the harmful impact that the Catholic Church and colonial settlers have had, and continue to have, on Indigenous communities, including specific examination of the impact of the 16th-century doctrine of discovery and papal bulls.

3. Amplify regional tribal voices that seek Indigenous cultural revitalization, ecosystem restoration, river pollution monitoring to ensure salmon survival, and collective respect of Native land and burial grounds alongside Lower Snake River.

4. Provide concrete actionable pathways for Catholics to live out Laduato Si’ & Laudete Deum by learning about and supporting environmental justice initiatives led by Indigenous neighbors in their region.

5. Co-design active conciliation process that invites Catholics to witness and foster localized community action that addresses Indigenous land dispossession, soil, air, and water pollution and its impact on Indigenous populations, and the dismissal

6. Pass the Columbia Basin River Initiative, which includes removal of the four Lower Snake River dams.

Values:

• Subsidiarity – the folks that are closest to the pain and harm hold the solutions for how to move forward, in this case we believe that those communities are the Salmon People of the Northwest.

• Encounter – through spending time with the land, water, plants, animals, and people connected to it, each of us can restore our connection and heal broken relationships, creating new life and possibilities.

• Reciprocity – in recognition that we are only able to move forward together for the common good it is through generative sharing of co-responsibility in the healing of creation with a focus on the health of the Columbia and Lower Snake Rivers and the species that inhabit its nearby ecosystems on land, water, and air.

Laudato Si’ and Laudate Deum

The following themes and connected topics emerge in both of Pope Francis’ encyclicals on the environment. These among others connect to this campaign informing and shaping the connections between our faith and this issue.

Cultural erasure due to environmental degradation – Indigenous communities are inextricably related to the physical places they inhabit, and as those places are destroyed so are their culture and existence.

Endangered species and biodiversity –The extinction of many species creates great urgency, as it ultimately weakens environments and risks our livelihood.

Technocratic paradigm – There is an overreliance on technical and market-based solutions for healing our common home.

“ Many intensive forms of environmental exploitation and degradation not only exhaust the resources which provide local communities with their livelihood, but also undo the social structures which, for a long time, shaped cultural identity and their sense of the meaning of life and community. The disappearance of a culture can be just as serious, or even more serious, than the disappearance of a species of plant or animal.”

—(LAUDATO SI’145)

Campaign Highlights

Sacred Salmon – A Matter of Spirit Fall 2023 –Read it here!

bit.ly/3xHYOLn

All Our Relations Campaign –Fall 2023

Over two weeks, the art piece (pictured right) “All Our Relations,” created by Lummi tribal member Cyaltsa Finkbonner, traveled to seven different places in the Northwest in order to depict what a free-flowing river might look like and the interconnected world we inhabit together. Centered around storytelling and prayer, the community learned about the cultural significance of salmon to the Salish Seas People and how salmon is integral to the livelihood and health of the entire Pacific Northwest.

Sacred Salmon Town Hall – Spring 2024

Over 150 folks gathered at Seattle University for the culminating event of the Northwest Ignatian Advocacy Summit. High school and college students led a town hall with staff members from Representative Pramila Jayapal and Kim Schrier’s offices, sharing why salmon recovery, dam removal, and tribal rights are important and vital for our community.

How to get involved:

Palouse Tribal Gathering and Canoe Healing Journey –Spring 2024

IPJC staff attended a Palouse Tribe gathering on April 19 at the confluence of the Snake and Columbia Rivers, commemorating the painful history of their community being stripped of its land through eminent domain laws when Ice Bridge Harbor Dam was built, flooding sacred sites and burial grounds. Connected to this gathering, a few weeks later, the community gathered for a multi-day healing canoe journey down part of the Snake River. Both events featured powerful truth telling, planting native species to heal the land and each of us, and were a great source of relationship and trust building. Our team has been honored to witness such beautiful and important moments, and we are grateful for the ongoing partnership grounding all of our Sacred Salmon work.

• Complete IPJC’s Action Alert promoting the Columbia Basin River Initiative: https://bit.ly/help-us-care

• Access our Sacred Salmon Toolkit to gather people in your community to meet with your legislators: https://bit.ly/Sacred-Salmon-Campaign-Toolkit

• Host a screening of Covenant of the Salmon People, available for free on PBS: KBTC Documentaries | Covenant of The Salmon People | PBS

• Join IPJC’s Sacred Salmon Campaign Organizing Team: https://bit.ly/Sacred-Salmon-Organizing-Team

All Our Relations, Olympia stop Sacred Salmon Town Hall participant Gonzaga Prep-Sacred Salmon Town Hall

An Ethics of Accountability

BY ELISHA CHI

“ God of hosts, are you not Creator of all that is good? Do you not dwell here too, on Coast Salish territory, where we so often acknowledge the land with words alone yet meet Indigenous death with silence? Where families are born on the frontline, births bruised by colonial blow, where we say ‘unceded’ but not ‘occupied’ for that would make us the occupiers: How do we partake in our portion of rage?” 1

When I was growing up, my dad (a conservative Irish/ British descendent Catholic) gifted me a story about the nature of relationship and accountability. It went like this: Some kids were playing baseball one day, when one of them batted the ball in the wrong direction, careening it into a neighbor’s window. My dad explained that while it was important for the kids to ’fess up and apologize for the broken window, the window also needed to be fixed.

Was this a story from his own childhood the Haller Lake neighborhood on stolen Duwamish lands in Seattle? I don’t remember. I do know he was primarily explaining the need for penance in the Catholic sacrament of confession. But his story gifted me with a crucial understanding of accountability that transcends the individuality of Catholic confession. Apologies are good, but what is necessary when something is broken is to repair the harm.

In a similar, though different vein, many institutions recognize that there are problems with our connections to

1 Benjamin Hertwig from Benjamin Hertwig and Céline Chuang, “Lament on Coast Salish Land,” in Unsettling the Word: Biblical Experiments in Decolonization, ed. Steve Heinrichs (New York: Maryknoll, 2018), 133–138, 20.

Photo © Sheila, Moonducks, Flickr

Land2 in the United States. Many know that the United States is, at heart, a settler colonial nation-state. But understanding these problems and terminology varies zby institution and individual. Some conflate settler colonialism and genocide, seeing Indigenous-settler history as a series of brief and terrible moments of annihilation.3 Others may understand that for most Indigenous communities on our continent, the genocide attempt was unsuccessful, but the cultural destruction and land dispossession were not.4 However, scholars have illustrated that settler colonialism is not a past event, although it includes those genocidal moments, but an ongoing structure that continues to dispossess Indigenous peoples from their Lands today.5 In other words, most of our homes and institutions were “legally” stolen on tribal lands from peoples who are still here. An ongoing theft. An ongoing wounding.

And of course, the Catholic Church is integral to this history. As Catholic Yakama scholar Michelle Jacob writes, “The Church, as a settler colonial institution, is deeply implicated in the dispossession of Indigenous peoples.” 6

However, regardless of how we understand our shared history, non-Indigenous communities are developing a sense that our national past is not pretty. Certainly, as Jacob explains, Indigenous communities and Catholic leaders, “despite their often radically different training and approaches to understanding the natural world, share similar conclusions about the current state of Mother Earth: Humans need to return to ways that treat Mother Earth respectfully.”7

Part of this respect involves approaching the relationship with Indigenous peoples through the frame of my dad’s story: To live your life on stolen land is to inescapably be in relationship with the people whose land is continuously

2 I capitalize the word “Land” when referring to Indigenous Lands because for Indigenous people, Land is not mere property, or land.

As Max Liboiron says: “when I capitalize Land I am referring to the unique entity that is the combined living spirit of plants, animals, air, water, humans, histories, and events recognized by many Indigenous communities. When land is not capitalized, I am referring to the concept from a colonial worldview whereby landscapes are common, universal, and everywhere, even with great variation.” Max Liboiron, Pollution Is Colonialism (Durham: Duke University Press, 2021), page 6, footnote 19.

3 Such as the Sand Creek Massacre. See: “Believing Is Seeing,” in Embracing Hopelessness, by Miguel A. De la Torre (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2017), 39–68.

4 This is true for the Unangax̂ people for example. See: Larry Merculieff, Wisdom Keeper: One Man’s Journey to Honor the Untold History of the Unangan People (Berkeley, California: North Atlantic Books, 2016).

5 Patrick Wolfe, “Settler Colonialism and the Elimination of the Native,” Journal of Genocide Research 8, no. 4 (December 2006): 387–409, https://doi.org/10.1080/14623520601056240.

61 Michelle M. Jacob, Indian Pilgrims: Indigenous Journeys of Activism and Healing with Saint Kateri Tekakwitha, Critical Issues in Indigenous Studies (Tucson: The University of Arizona Press, 2016), 36.

7 Jacob, Indian Pilgrims, 43.

being stolen. 8 This relationship is fundamental and intrinsic. It is present at every moment.

One way I see individuals and institutions attempting to rectify this is through Indigenous land acknowledgments. As Native journalist Kevin Abourezk explains, “A land acknowledgment is a traditional custom dating back centuries for many tribes. Tribes practiced this custom as a way to honor their ancestors and pay their respects to neighboring tribes they were visiting.”9

This raises a question for me: As an Indigenous custom, what went into such acknowledgments? While each international Indigenous relationship is unique, thinking about how borders function for Indigenous peoples is helpful. For example, Nishnaabeg scholar Leanne B. Simpson writes that “borders for indigenous nations are not rigid lines on a map but areas of increased diplomacy, ceremony, and sharing.”10

Indigenous people have noted the disappointingly performative nature of many (perhaps most) land acknowledgments, writing that “after acknowledging that an institution sits on another’s land, plans are almost never made to give the land back.”11 This illustrates a key difference to the relationality present in Indigenous histories of land acknowledgment and their contemporary use by non-Indigenous communities: accountability.

Accountability is needed to craft a meaningful relationship between settler people and institutions, the Indigenous nations we are still dispossessing, and the Indigenous Lands we occupy. As this relationship of settlement and occupation is a given, all that can be chosen is our ethics in the relationship. How will we hold ourselves accountable—in our families, communities, and institutions—to this relationship founded on broken, unrepaired windows?

Now, to be clear, when I use the term accountability, I am not talking about individual culpability in a strict sense. The reality is that those of us who individually find a place to live, work at a job, have a church to worship in, or a space where we acquire food, are benefitting because an Indigenous family, community, tribe, or nation is not. This matters. And yet, all of us also participate in institutions that have extensive ability to impact

8 I am highlighting theft here as continuous, because Indigenous peoples do not view Land as mere property but with a variety of attributes that can include property but all center on relationality. See: Dana Lloyd, Land Is Kin: Sovereignty, Religious Freedom, and Indigenous Sacred Sites (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2024).

9 Kevin Abourezk, “Is It Time to Move beyond Land Acknowledgements? Native Nonprofit Leaders Call for Making Reparations to Tribes and Returning Tribal Homelands,” Indian Country Today, November 20, 2023, https://ictnews.org/news/is-ittime-to-move-beyond-land-acknowledgements.

10 Leanne Betasamosake Simpson, “The Place Where We All Live and Work Together: A Gendered Analysis of ‘Sovereignty,’” in Native Studies Keywords, ed. Stephanie N Teves, Andrea Smith, and Michelle H Raheja, Critical Issues in Indigenous Studies (University of Arizona Press, 2015), 18–24, 19.

11 Michael C. Lambert, Elisa J. Sobo, and Valarie L. Lambert, “Rethinking Land Acknowledgments,” Anthropology News, December 20, 2021, Truth and Responsibility edition, https:// www.anthropology-news.org/articles/rethinking-landacknowledgments/#citation

the lives of marginalized peoples—institutions that thrive at the expense of Indigenous life.

In the frame of my Dad’s story: Even if we have not individually broken a window via attempted genocide, child separation, violent assimilation, or outright land theft, we settlers and members of settler institutions such as the Catholic Church continuously glean life from the window’s lack of repair, and we do so at the expense of the homeowner. What other options are there? As the Native Governance Center writes, “Instead of spending time on a land acknowledgment statement, we recommend creating an action plan highlighting the concrete steps you plan to take to support Indigenous communities into the future.”12 At the institutional level this support must honestly engage with the possibility of land return. At all levels, we must choose accountability and an ethic that seeks to repair the broken windows of genocide and Indigenous land dispossession.

An ethic of repair may mean institutional or individual land return, wealth redistribution, and/or participation in land protection and land back movements. As Potawatomi writer Katilin Curtice explains, “The wake-up call to use our voices, whether we are Native or not, is one we cannot ignore.”13 Listening to this call with an ethic of repair does not mean, in the words of Pope Francis, a type of “doing good without expecting anything in return.”14 There is no need for this kind of mercy: Indigenous peoples not only know what is best for our Land, but also have plenty to offer the world, including the church. As Curtice says, “Perhaps the church should consider that Indigenous people have more to teach the church than the church has to teach Indigenous people.” 15

What Indigenous nations want from settler members of this ongoing relationship of land occupation is accountability. We want partners to struggle with us to protect our Land. We want partners in the ongoing quest for decolonization: a quest that ultimately aims to return Indigenous Lands back to Indigenous nations. This is what land acknowledgments, or action plans, should be all about.

Dr. Elisha Chi is a registered descendant of the Bering Straits Native Corporation and a descendant of Irish/British Catholics, raised on Duwamish lands in the antifeminist radical traditionalist Catholic community of Seattle. Her interdisciplinary work seeks to articulate anticolonial academic methods and pedagogical practices that pursue Indigenous land return.

12 Native Governance Center, “Beyond Land Acknowledgement: A Guide,” September 21, 2021, https://nativegov.org/news/beyondland-acknowledgment-guide/.

13 Kaitlin B. Curtice, Native: Identity, Belonging, and Rediscovering God (Grand Rapids, Michigan: Brazos Press, a division of Baker Publishing Group, 2020), 115.

14 Pope Francis, “General Audience” (Saint Peter’s Square, Vatican City, September 10, 2014), https://www.vatican.va/ content/francesco/en/audiences/2014/documents/papafrancesco_20140910_udienza-generale.html

15 Curtice, Native, 123.

Choose Solidarity, Not Guilt

BY TESS GALLAGHER CLANCY

Igrew up in a middle class, Irish American family in Montana; this place is the home of my parents, grandparents, and great-grandparents. I love this land, and I feel my ancestors’ presence here. And yet, my love for this land is complicated. At some point I became aware of its history, which I had only really understood in a vague way before: the many dishonestly forged, broken treaties between the emerging U.S. government and the tribes; the encroachment of often violent and belligerent settlers into Native lands; the impoverishment and forced removal of tribes from their lands; the greedy capitalists lobbying the government to annex more and more land so they could pillage and sell the bounties; the ongoing oppression of Native communities at the hands of our government, extractive businesses, and our capitalist economy.

If you grew up white, or of European descent in the United States, perhaps you came to a similar knowledge about the land where you and your forebears grew up. Maybe you experienced the same feeling of having the rug pulled out from underneath your reality as I did. It’s difficult to realize that a brutal and devastating campaign of destruction is ultimately responsible for our presence on this land.

These are the realities we live with. To individualize this reality of great, ongoing injustice, casting blame on each of us as individuals, does little to move toward justice. However, if we believe in right-relationship with the land, one another, and the people who have come before us, this reality is now our own, and it is our responsibility to decide what to do with it.

I want to talk about land, guilt, and responsibility, and how we can navigate these topics to have richer lives—lives that aren’t mired in guilt but that are in relationship and reciprocity to the people, creatures, and places around us. When it comes to white Americans’ duty to support movements for Indigenous sovereignty responsibility isn’t a punishing accusation, but something we can choose because we care about our neighbors and we believe in solidarity with those around us.

A narrative that I’ve heard in social justice environments over the past few years is that perhaps the descendants of settlers shouldn’t talk about the connections they have to land and place. People imply that these connections are paltry, anemic, or even false.

The truth is that this kind of thinking denies reality. The difficulty of a process such as settler colonization, which settles new people on a land at the expense of those already there, is that once people are in a place, they will develop relationships with it. The Earth is our home, our natural environment, and we all belong to it. The relationships that the descendants of colonial settlers have to a place won’t be the same as the relationships that Indigenous people have, but that does not mean they are inevitably flawed and bankrupt.

I want people to come to social movements because they want to be there. I want people to raise their hands for Indigenous sovereignty and seriously engage with what returning land to Indigenous people means, and I want people to do those things because they actually feel their own liberation on the line in this struggle.

Settlers can begin to recognize our own stake in decolonization when we understand that the colonization that landed us here came from the same brutal systems that dominated Europe, where capitalism developed. The brutality that colonizers were quick to use had often been first tested out on their own populations closer to home. It’s in understanding the roots of our own struggles in this corrupt, exploitative economic system that we can connect our struggles with others’.

For people who are the descendants of settlers and colonizers in this land, we’re faced with this twofold reality: that many of our families have experienced great violence from colonial systems and that empires and kings used our families’ lives to gain control over other people’s lands, sending our ancestors to steal and settle it and allowing some of us to share in that prosperity.

For many of us, our initial response is guilt for the privileges that we may now experience, and for the destruction that our families’ presence is built on. However, the guilt and shame we often use to rally people to social justice causes can do the opposite. Instead of solidarity, we often win ourselves timid allies and bitter enemies.

One of Christianity’s legacies is this very behavior toward many of us: most of us know what it feels like to have had enough of this kind of treatment. Neither guilt nor shame helps us address injustice in the long term, and they don’t promote communities or movements that are really founded on rightrelationship. Going through my own process of feeling guilt and shame at my whiteness and my settler-ness, I’ve found that I’m much more willing to accept poor treatment from others, and I disrespect my own well-being and autonomy. Guilt and shame aren’t feelings from which I can sustainably invest in movements, organizing, and change-making. From this

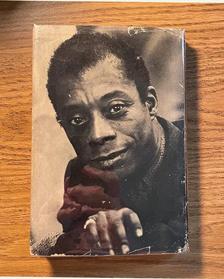

“ One is responsible to life: It is the small beacon in that terrifying darkness from which we come and to which we shall return. One must negotiate this passage as nobly as possible, for the sake of those who are coming after us.”

— JAMES BALDWIN, “THE FIRE NEXT TIME”

understanding, and my love of the life and rhythms of the land and people around me, I have been able to reengage not from a feeling of fear, coercion, and guilt but from a place of respect for myself and others, and a felt sense that what hurts those around me hurts me as well.

James Baldwin wrote in his essay “The Fire Next Time”: “One is responsible to life: It is the small beacon in that terrifying darkness from which we come and to which we shall return. One must negotiate this passage as nobly as possible, for the sake of those who are coming after us.”

Baldwin is saying that being responsible to our own lives means being both responsive to what has come before us, and looking out for who comes next. Those before, us now, those to come—we deserve a lot more than the guilty weight of generations, and a broken world in which the average person has very little power. I think being responsible to the generations of people who have cycled across this land means being serious about what can actually change the present and the future: Organizing ourselves in solidarity with one another’s struggles so that we can collectively exert real power for the kind of world we want to live in. Through solidarity, not guilt, we will be responsible to life.

Tess Gallagher Clancy was born and raised in western Montana on Salish land, in an Irish American family. She thinks a lot about land, place, belonging, and labor, and writes a newsletter at spiritofsolidarity.substack.com.

Reflection

BEYOND LAND ACKNOWLEDGMENT

What is an Indigenous land acknowledgment?

A land acknowledgment is an effort to recognize the Indigenous past, present, and future of a particular location and to understand our own place within that relationship.

Why can land acknowledgments be problematic?

When crafting land acknowledgment statements, non-Indigenous folks ask Indigenous people and communities to do free emotional labor. In addition to normal employment and family obligations, Indigenous people are working to heal their traumas, learn their languages, and support their nations. They don’t want to spend their free time working as unpaid land acknowledgment consultants.

If you’ve done all you can on your own and decide to ask for help on a land acknowledgment, offer fair compensation, be prepared to be told “no.” Aside from the emotional labor, land acknowledgments can have unintended negative consequences. Every moment spent agonizing over land acknowledgment wording is time that could be used to actually support Indigenous people.

It’s easy for land acknowledgments to become yet another form of optical allyship. They often lack a call to action and next steps. Without these components, land acknowledgments are just empty words.

What does it mean to go beyond land acknowledgment?

Instead of spending time on a land acknowledgment statement, we recommend creating an action plan highlighting the concrete steps you plan to take to support Indigenous communities into the future. Similar to a land acknowledgment, your plan will include information and research on the land you occupy, but it will primarily focus on action.

Some questions to consider when creating this action plan:

1. Do you or your community ever appropriate Native culture?

2. Do you respect sovereignty and sacred sites when you travel? For more information, visit Native Governance Center’s Sovereignty and Outdoor Spaces guide at nativegov.org.

3. What resources can you or your community provide to support Indigenous people and nations? Can you set aside money each month for a recurring donation to an Indigenous organization? Do you have time to show up to an Indigenous-led protest or help create a voluntary land tax program in your area? Do you have land that you want to return to Indigenous people, either now or in the future?

4. Research what’s happening in your area and how you can help. What is the Indigenous history of the land you occupy? What Native nation is located closest to you? What projects is the nation working on? Who are their elected leaders? What Native-led organizations and nonprofits operate in my area? Are there Native-led demonstrations happening near me to protest Treaty Rights violations or projects threatening Native lands and lifeways?

Reflection and questions adapted from the Native Governance Center’s “Beyond Land Acknowledgment: A Guide.” You can find more details and guidance for creating your own action plan on their website: nativegov.org

A LOOK BACK

IPJC Staff Traveled to Palouse Tribe Gathering

IPJC’s staff was invited to witness and participate in a powerful gathering hosted by Khimstonik, an Indigenous-led nonprofit committed to responsible land development guided by Indigenous wisdom. Our staff witnessed insightful testimonies and ritual, participated in a First Foods ceremonial meal, and planted native species to heal the land.

Top: Planting native plants

Below: Viewing of the Ice Harbor Dam salmon ladder with Julian Matthews of Nimiipuu Protecting the Environment

Youth Action Team Internship News

The year ended with a powerful encounter between the Youth Action Team interns and the superintendent of Catholic schools for the Archdiocese of Seattle. The students shared their community’s struggle with mental health and offered possible solutions for Catholic schools to implement.

Empowered Leaders for Change

Over the last few months, IPJC has embarked on a project to accompany St. Leo’s parish in Tacoma and the South Seattle Parish family in community organizing, leadership development, and listening campaigns. These have been a source of beautiful encounter: Stay tuned to hear how things develop over the coming months.

Tacoma Dominicans honored at the IPJC Spring Benefit

We had a beautiful gathering of the community to celebrate IPJC's work and honor the prophetic charism and ministry of the Tacoma Dominicans (pictured above). Due to the generosity of the community, we raised over $114,000 to support the mission of the center. Thank you to all who attended and gave generously!

UPCOMING Ignite 2024

IPJC is excited to host over 30 highschool students from five different states during the week of July 15 in collaboration with the Agape Service Project! We are grateful to walk with the farmworking community and the student delegations throughout the week.

Donations

IN HONOR OF All Who Work for Justice, Judy Byron, OP Mother Francis Clare, CSJP founder IPJC's 40th Anniversary Jubilarians of the Sisters of St. Francis of Philadelphia Sr. Alexandra Kovats, CSJP

IN MEMORY OF Fr. Kenneth Haydock, Mary Pat Murphy, OP Peg Murphy, OP, Sr. Lousie McDonald, CSJ, Bill Tobin

IPJC community gather at Seattle University, Piggot Auditorium foyer

Ignite 2023 participants

Intercommunity Peace & Justice Center

1216 NE 65th St Seattle, WA 98115-6724

SPONSORING COMMUNITIES

Adrian Dominican Sisters

Congregation of the Sisters of St. Joseph of Peace

Jesuits West

Sisters of the Holy Names of Jesus and Mary, U.S.-Ontario Province

Sisters of Providence, Mother Joseph Province

Sisters of St. Francis of Philadelphia

Tacoma Dominicans

AFFILIATE COMMUNITIES

Benedictine Sisters of Cottonwood, Idaho

Benedictine Sisters of Lacey Benedictine Sisters of Mt. Angel

Dominican Sisters of Mission San Jose Dominican Sisters of Racine

Dominican Sisters of San Rafael Sinsinawa Dominicans

Sisters of Charity of the Blessed Virgin Mary Sisters of St. Francis of Redwood City

Sisters of St. Joseph of Carondelet Sisters of St. Mary of Oregon

Society of the Holy Child Jesus Sisters of the Holy Family Sisters of the Presentation, San Francisco Society of Helpers

Society of the Sacred Heart Ursuline Sisters of the Roman Union

EDITORIAL BOARD

Don Clemmer

Kelly Hickman

Nick Mele

Andrea Mendoza Will Rutt

Editor: Emily Sanna

Copy Editor: Elizabeth Bayardi, Carl Elsik

Design: Sheila Edwards

A Matter of Spirit is a quarterly publication of the Intercommunity Peace & Justice Center, a 501(c)3 nonprofit organization, Federal Tax ID# 94-3083964. All donations are tax-deductible within the guidelines of U.S. law. To make a matching corporate gift, a gift of stocks, bonds, or other securities please call (206) 223-1138. Printed on FSC® certified paper made from 30% post-consumer waste.

Front Cover: Photo © Megan C. Mack, The Snake River at Hells Canyon, Oregon, participants of the All Our Relations 14-day journey across the NW in support of the treaty rights in the Columbia River basin and the health of the Salish Sea bio-region.

Back Cover: Photo © Annie Spratt, unsplash. Photos © IPJC unless noted. ipjc@ipjc.org • ipjc.org

Prayer of Reconciliation

We gather with a hunger for reconciliation. What is done cannot be undone. What is done next must now be done with care.

We gather because we are hopeful, Because we have visions and dreams of a brighter future. That there may be more than vision in this room, These are the wounds we must heal together— Grief and anger for all that has been lost, Guilt or fear in the reliving, Pain that has gone without sufficient comfort, Mistrust that was earned, that continues burning still, Every injury we may have named, and yet still carry, Those we haven’t, can’t, or dare not speak aloud, Those we are not ready to make public, Those still not recognized, accepted, understood.

These are the wounds that seek replacement— Not cancellation or denial, Wounds we will tend cautiously, Applying the salve of understanding, Forming scars that mark our history, Without disfiguring the future we might share.

This is not a time of quick solutions, fancy talking. This is a slow precision. This is a prayer for peace.

We are new at this endeavor. New at listening, new at hearing. New at taking enough time to honestly receive one another’s stories.

What is done cannot be undone. What is done next must now be done with care.

We gather because we are hopeful, Because we have visions and dreams of a brighter future.

May the strength of this time together help us to walk forward. May the wisdom of this experience help us to know our path. May we have the courage to return, as often as necessary, until our way is clear.

May we have the perseverance, together, to see it through.

May we cause it to be so.

—Anne Barker, from To Wake, To Rise (Skinner House Books)