“ While they were eating, Jesus took a loaf of bread, and after blessing it he broke it, gave it to the disciples, and said, ‘Take, eat; this is my body.’ ”

(MATTHEW 26:26)

hese words are well known to anyone who is familiar with the Catholic eucharistic liturgy. Whatever our beliefs about the precise theological meaning of these morsels of bread, we have probably set this ceremonial meal into a category all its own, separated from the ordinary meals we eat to satisfy our hunger and sustain our bodies.

But let’s imagine for a moment that we are one of the disciples, hearing Jesus speak these familiar words for the first time. When he said, “Take, eat,” he meant it quite literally. A meal was laid out on the table, and he and his friends had gathered to share it. Basically, Jesus was saying, “Bon Appetit! Enjoy!”

But then his next words changed everything: “This is my body.” If you’re sitting at the table with Jesus, what is your reaction to those words? I suspect you may have barely noticed them at the time; your mouth was full of bread and olives and cheese. You probably wouldn’t have thought you were suddenly munching on the flesh of your friend. It was only afterward, looking back, that you and your friends would try to make sense of Jesus’ odd words and actions.

I believe Jesus was saying that food—all food—tells us something about divine love. The very essence of Jesus—the selfsurrender that brings life and growth—is expressed by the physical nutrition we take in.

Food is important in American culture, as it is in most cultures, but our relationship with it has often become complicated, sometimes even unhealthy. We forget that food links us to

the Earth, to all life, to one another, and ultimately to God. We overlook the fact that we are nourished by the deaths of countless plants and animals; we don’t remember that with each bite, we are eating sunlight and rain, soil and minerals; and we don’t see the many human hands that farmed and tended the land, that harvested and packed, that shipped and processed, creating those seemingly ready-made foods that show up on our grocery store’s shelves.

In my birthland of Haiti, it’s easier to see the connections that food expresses. We see the farms where our food grows, and the distance between table and field is narrow. Food is the focal point of our family and community lives. It is how we

express love to one another, celebrate together, and share and comfort one another during sorrowful times.

Let me introduce you to one of my family’s favorite foods: soup joumou. It’s made from beef and winter squash, but its broth is also rich with celery, leeks, radishes, garlic, parsley, carrots, onions, cabbage, and potatoes. We eat it with bread, dipping chunks into the soup. It’s delicious, and my mouth waters just thinking about it. It is a food so vital to Haitian

HAITI“The very essence of Jesus—the self-surrender that brings life and growth—is expressed by the physical nutrition we take in.”

identity that in 2021 UNESCO added it to the organization’s Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.1

But there is far more to soup joumou than its wonderful flavor and the satisfying warmth it gives the belly. For my family—and for all Haitians—soup joumou tastes of freedom. It nourishes us with the savor of equality and justice.

Long ago, when Haiti was colonized by France, the European plantation owners were the ones who enjoyed the soup joumou prepared by my enslaved ancestors. Meanwhile, my enslaved ancestors made do with whatever scraps the white colonizers deemed inedible. Black people were forbidden to eat the rich dish the white landowners enjoyed.

And so, in 1804, when Haiti became the world’s first and only independent nation to be built by formerly enslaved people, as well as the world’s first free Black republic, we made the thickest, tastiest soup joumou ever. And then we sat our Black selves down and ate it all, every drop.

January 1st is the anniversary of Haiti’s liberation, and so soup joumou is now the traditional Haitian New Year’s Day meal. When I was growing up, every room in our house smelled like soup joumou the entire first week of January. But that wasn’t the only time we ate it. My mother and grandmother also made soup joumou for other celebrations. As my fellow Haitian author, Jenna Chrisphonte, writes, eating soup joumou is an “act of perpetual restoration, communion and hope . . . encouraging people to remember the past while also welcoming the future.” 2

Is that not what Jesus was hoping to do as well, when he claimed bread as his own identity? With each eucharistic meal, we consume a God who works for justice, harmony, and equality; a God whose very nature is love. In doing so, we claim as our own the centuries of sacramental meals that stretch all the way back to the first meal with Jesus and his friends in the Upper Room. Strengthened by that long history, we face the future with new hope, new fortitude. We remember we are part of an ongoing story that began long, long ago but continues on as we work together, sharing resources and friendship, for what sometimes seems impossible: a future of freedom, equality, well-being, and respect for all.

Soup joumou reassures me and my people that even in the darkest of times—when our island is shaken by earthquakes and hurricanes, gang violence, and disease—there is always hope. The impossible is possible. Together, with God’s help, we can do amazing things. We remember this on January 1st, our Independence Day, and we also remember it every time we prepare and eat soup joumou throughout the year.

1 “Joumou soup,” UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage, accessed Jan 3, 2023, https://ich.unesco.org/en/RL/joumou-soup-01853.

2 Jenna Chrisphonte, “Soupe joumou, a symbol of freedom and hope, is a New Year’s Day tradition for Haitians everywhere,” Washington Post, December 22, 2020.

What if we prepared and ate bread with the intention of a fellowship that leads to justice? I’m saying nothing to detract from the Eucharist, the most beloved of sacraments. Pope Benedict compared the Eucharist to nuclear fission, “which penetrates to the heart of all being, a change meant to set off a process which transforms reality, a process leading ultimately to the transfiguration of the entire world.”3

I believe in that with all my heart. But I also believe we need not confine the reminders of Jesus only to those brief, sacramental moments. The first Eucharist was an informal meal, friends sitting around a table together, sharing conversations, bread, and wine. How might our lives change if each bite of bread we took, each sip of wine, each occasion of fellowship with good friends and family all served to prompt us to work harder for the unity, justice, and compassion to which we are called? Just as soup joumou is a witness to Haitians’ dignity, strength, and potential, each ordinary loaf of bread carries within it an intentional message that is both a challenge and an inspiration. It says to us: “You live because the sun shines and the Earth bears fruit.

Your life depends on the divine, self-giving grace of plants, animals, and other humans. And you are blessed to have this nourishment when so many do not have enough.”

What if every time we bit into a piece of bread, we heard Jesus’ voice saying, “Take, eat. This is my body”? I suspect each bite of bread might become a statement against exclusion and discrimination, as well as a call to solidarity and sharing. In a world poisoned by poverty, racism, and greed, each loaf would be like soup joumou: a reminder of the past that nourishes us and strengthens us to build a better future.

Patrick Saint-Jean, S.J. is a native of Haiti and a member of the Midwest Province of the Society of Jesus. He currently teaches psychology at Creighton University in Omaha. He is the author of Home-Going: The Journey from Racism and Death to Community and Hope (Anamchara Books).

3 Pope Benedict XVI, Apostolic Exhortation Sacramentum Caritatis (2007), accessed January 3, 2023, https://www.vatican.va/content/ benedict-xvi/en/apost_exhortations/documents/hf_ben-xvi_ exh_20070222_sacramentum-caritatis.html

“How might our lives change if each bite of bread we took, each sip of wine, each occasion of fellowship with good friends and family all served to prompt us to work harder for the unity, justice, and compassion to which we are called?”

1 lb beef stew meat

1 lb beef bones

Juice of 3 limes, divided

1 onion, chopped

1/2 green bell pepper, chopped

1 bunch scallions, chopped

1 head garlic, peeled and cloves separated

1/4 cup fresh parsley, chopped

1 tablespoon olive oil

12 cups + 1 tablespoon water, divided, plus more as needed

1 teaspoon kosher salt

2 tablespoons Creole or Cajun seasoning

1 kabocha squash

3 medium potatoes, diced

3 medium carrots, chopped

3 ribs celery, chopped

1 turnip, diced

1 large leek, halved lengthwise and sliced thinly

1 Scotch bonnet pepper, left uncut (optional)

1 extra-large chicken bouillon cube

10 sprigs fresh thyme, tied with twine, plus more for garnish

1 small head green cabbage, cut into 1- to 2-inch ribbons

3/4 cup penne or other similar pasta

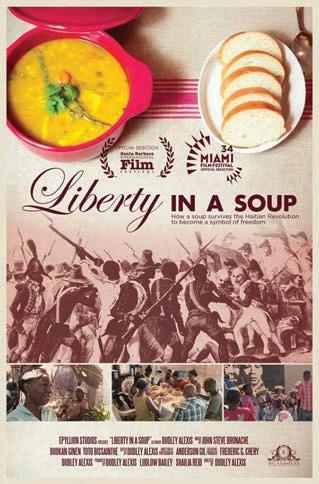

For more on the significance of soup joumou within the context of the Haitian revolution, watch Liberty in a Soup (Dudley Alexis, 2016).

In a large bowl, combine the meat and bones with about 4 tablespoons of lime juice and let sit for 10 minutes. Rinse thoroughly.

In a food processor, combine the onion, bell pepper, scallions, garlic, parsley, olive oil, 1 tablespoon of water, and salt. In a large stockpot, combine the meat, bones, and herb paste. Add the Creole or Cajun seasoning, stir to combine, and let marinate for at least 10 minutes and up to 24 hours.

Without peeling, cut the squash in half, then scoop out and discard the seeds. Cut the flesh into 4–6 wedges and place on top of the meat. Add 6 cups of water and bring to a boil. Cover and cook until the squash is tender, 15 to 20 minutes. Transfer squash to a large bowl and let cool slightly. Using a spoon, scoop out the flesh and transfer to food processor. Add 2 cups of water and blend until smooth. Pour into the stockpot and stir to combine. Add the potatoes, carrots, celery, turnip, leek, and Scotch bonnet pepper, followed by 4 cups of water and the bouillon cube. Add the thyme bouquet and stir. Bring to a boil, then simmer for 20 minutes. Stir in the remaining lime juice. Add the cabbage and pasta, stir to combine, and simmer until the pasta is cooked and the cabbage is tender, an additional 15 to 20 minutes. Garnish with fresh thyme and serve hot.

Source: Jenna Chrisphonte, https://www. washingtonpost.com/food/2020/12/22/ haitian-soupe-joumou-recipe/