The Power of Food

A Global Crisis

Body and Soul

The Gospel in Action

The Power of Food

A Global Crisis

Body and Soul

The Gospel in Action

When new or future parents think about growing their families, some people think about planning out their nursery. Others might get excited about introducing the new baby to favorite music, activities, or the family pet. For me, I was the most excited about introducing a new, tiny human to food.

Years before I found out I was pregnant—before my husband and I even thought about having kids—I followed child nutritionists on Instagram and researched the best ways to feed infants. When Robin, my now-toddler, arrived I waited semipatiently for him to hit 6 months old so that he could join us during mealtimes. There was no baby cereal or apple sauce for this kid: Among his first foods were a quartered tomato, whole strawberries, and a chicken wing.

I’m not sure whether this immersion approach to the world of food has affected Robin’s food preferences at all. Now, a year later, he seems to have a fairly typical toddler palette—he has never met a carb he didn’t like but will immediately throw any offending green vegetable off his highchair tray. But I’ve come to realize that my excitement wasn’t about eating the food, exactly—it was more about teaching him to join in this communal experience that is so important to me, that I feel joins me with my family, the Earth, and with God.

On one hand, that connection is quite literal—for the first several months of Robin’s life, my husband or I would often have to scarf down dinner in shifts so the other person could hold the baby. At other times I’d eat one-handed on the couch while nursing Robin or while he slept curled in my arms. Now we have family dinners. We laugh as Robin figures out how to use silverware or at his funny faces while he stuffs his mouth, afraid of missing a bite. He steals bites from our plates and chatters to us in words that are slowly starting to make more and more sense. His first word was “all done!”

But the connections fostered by food go far beyond family dinners. Every time I cook a family recipe or use my grandma’s old measuring cups or juice glasses, I think of how much my grandparents would have loved meeting Robin, and I am glad

Robin is connected to the generations of people who come before him through food. Every time we go to the farmers’ market and Robin helps pick out the fruit and vegetables we cook with that week, I think of how food connects us to our local community. Every time we go to church and break bread together—whether at Communion or during coffee hour afterward—I think of how Robin is part of a global faith community. None of this might mean a lot to him now, but maybe next year, or the year after that, he will start to see how food serves as the ties that bind all of creation together.

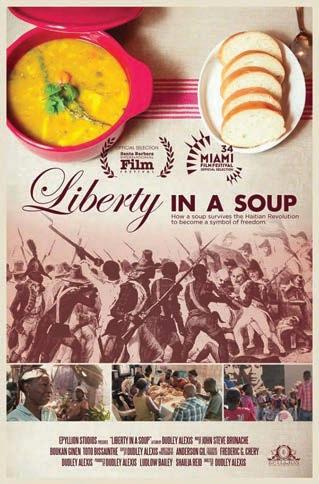

The articles throughout this issue tell similar stories about how food drives relationships across ethnicities, citizenship, gender, generation, and social location. In “The Power of Food,” Patrick Saint-Jean, S.J. tells a story about soup joumou, both a beloved family dish and a symbol of Haitian independence from colonialism, and how a simple meal can be a symbol of communion that calls us to work for justice. In “A Global Crisis,” Carlos Barrio writes about the work of Catholic Relief Services in Somalia and describes how global food systems are all interconnected—from the Ukraine to Somalia to us here in the United States. Kelsey Harrington takes this interconnection one step further and, in “Body and Soul,” asks readers to remember not only where their physical food comes from, but their spiritual food as well. “When Catholics take Communion, we are not eating raw wheat and raw grapes; we are consuming a handmade creation, harvested by human hands,” she writes. And, finally, in “The Gospel in Action” José Ortiz tells how his grandparents taught him to live the gospel and drove his vocation to work for farmworkers and their families.

All these writers come from different corners of the globe and from very different backgrounds. But their underlying message is the same: Food is what connects us. It is a way to show love to one another. It teaches us that we cannot exist without one another. At its core, this is the message I hope to pass on through family meals, trips to the farmers’ market, and cooking dinner together.

—Emily Sanna“ While they were eating, Jesus took a loaf of bread, and after blessing it he broke it, gave it to the disciples, and said, ‘Take, eat; this is my body.’ ”

(MATTHEW 26:26)

hese words are well known to anyone who is familiar with the Catholic eucharistic liturgy. Whatever our beliefs about the precise theological meaning of these morsels of bread, we have probably set this ceremonial meal into a category all its own, separated from the ordinary meals we eat to satisfy our hunger and sustain our bodies.

But let’s imagine for a moment that we are one of the disciples, hearing Jesus speak these familiar words for the first time. When he said, “Take, eat,” he meant it quite literally. A meal was laid out on the table, and he and his friends had gathered to share it. Basically, Jesus was saying, “Bon Appetit! Enjoy!”

But then his next words changed everything: “This is my body.” If you’re sitting at the table with Jesus, what is your reaction to those words? I suspect you may have barely noticed them at the time; your mouth was full of bread and olives and cheese. You probably wouldn’t have thought you were suddenly munching on the flesh of your friend. It was only afterward, looking back, that you and your friends would try to make sense of Jesus’ odd words and actions.

I believe Jesus was saying that food—all food—tells us something about divine love. The very essence of Jesus—the selfsurrender that brings life and growth—is expressed by the physical nutrition we take in.

Food is important in American culture, as it is in most cultures, but our relationship with it has often become complicated, sometimes even unhealthy. We forget that food links us to

the Earth, to all life, to one another, and ultimately to God. We overlook the fact that we are nourished by the deaths of countless plants and animals; we don’t remember that with each bite, we are eating sunlight and rain, soil and minerals; and we don’t see the many human hands that farmed and tended the land, that harvested and packed, that shipped and processed, creating those seemingly ready-made foods that show up on our grocery store’s shelves.

In my birthland of Haiti, it’s easier to see the connections that food expresses. We see the farms where our food grows, and the distance between table and field is narrow. Food is the focal point of our family and community lives. It is how we

express love to one another, celebrate together, and share and comfort one another during sorrowful times.

Let me introduce you to one of my family’s favorite foods: soup joumou. It’s made from beef and winter squash, but its broth is also rich with celery, leeks, radishes, garlic, parsley, carrots, onions, cabbage, and potatoes. We eat it with bread, dipping chunks into the soup. It’s delicious, and my mouth waters just thinking about it. It is a food so vital to Haitian

HAITI“The very essence of Jesus—the self-surrender that brings life and growth—is expressed by the physical nutrition we take in.”

identity that in 2021 UNESCO added it to the organization’s Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.1

But there is far more to soup joumou than its wonderful flavor and the satisfying warmth it gives the belly. For my family—and for all Haitians—soup joumou tastes of freedom. It nourishes us with the savor of equality and justice.

Long ago, when Haiti was colonized by France, the European plantation owners were the ones who enjoyed the soup joumou prepared by my enslaved ancestors. Meanwhile, my enslaved ancestors made do with whatever scraps the white colonizers deemed inedible. Black people were forbidden to eat the rich dish the white landowners enjoyed.

And so, in 1804, when Haiti became the world’s first and only independent nation to be built by formerly enslaved people, as well as the world’s first free Black republic, we made the thickest, tastiest soup joumou ever. And then we sat our Black selves down and ate it all, every drop.

January 1st is the anniversary of Haiti’s liberation, and so soup joumou is now the traditional Haitian New Year’s Day meal. When I was growing up, every room in our house smelled like soup joumou the entire first week of January. But that wasn’t the only time we ate it. My mother and grandmother also made soup joumou for other celebrations. As my fellow Haitian author, Jenna Chrisphonte, writes, eating soup joumou is an “act of perpetual restoration, communion and hope . . . encouraging people to remember the past while also welcoming the future.” 2

Is that not what Jesus was hoping to do as well, when he claimed bread as his own identity? With each eucharistic meal, we consume a God who works for justice, harmony, and equality; a God whose very nature is love. In doing so, we claim as our own the centuries of sacramental meals that stretch all the way back to the first meal with Jesus and his friends in the Upper Room. Strengthened by that long history, we face the future with new hope, new fortitude. We remember we are part of an ongoing story that began long, long ago but continues on as we work together, sharing resources and friendship, for what sometimes seems impossible: a future of freedom, equality, well-being, and respect for all.

Soup joumou reassures me and my people that even in the darkest of times—when our island is shaken by earthquakes and hurricanes, gang violence, and disease—there is always hope. The impossible is possible. Together, with God’s help, we can do amazing things. We remember this on January 1st, our Independence Day, and we also remember it every time we prepare and eat soup joumou throughout the year.

1 “Joumou soup,” UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage, accessed Jan 3, 2023, https://ich.unesco.org/en/RL/joumou-soup-01853.

2 Jenna Chrisphonte, “Soupe joumou, a symbol of freedom and hope, is a New Year’s Day tradition for Haitians everywhere,” Washington Post, December 22, 2020.

What if we prepared and ate bread with the intention of a fellowship that leads to justice? I’m saying nothing to detract from the Eucharist, the most beloved of sacraments. Pope Benedict compared the Eucharist to nuclear fission, “which penetrates to the heart of all being, a change meant to set off a process which transforms reality, a process leading ultimately to the transfiguration of the entire world.”3

I believe in that with all my heart. But I also believe we need not confine the reminders of Jesus only to those brief, sacramental moments. The first Eucharist was an informal meal, friends sitting around a table together, sharing conversations, bread, and wine. How might our lives change if each bite of bread we took, each sip of wine, each occasion of fellowship with good friends and family all served to prompt us to work harder for the unity, justice, and compassion to which we are called? Just as soup joumou is a witness to Haitians’ dignity, strength, and potential, each ordinary loaf of bread carries within it an intentional message that is both a challenge and an inspiration. It says to us: “You live because the sun shines and the Earth bears fruit.

Your life depends on the divine, self-giving grace of plants, animals, and other humans. And you are blessed to have this nourishment when so many do not have enough.”

What if every time we bit into a piece of bread, we heard Jesus’ voice saying, “Take, eat. This is my body”? I suspect each bite of bread might become a statement against exclusion and discrimination, as well as a call to solidarity and sharing. In a world poisoned by poverty, racism, and greed, each loaf would be like soup joumou: a reminder of the past that nourishes us and strengthens us to build a better future.

Patrick Saint-Jean, S.J. is a native of Haiti and a member of the Midwest Province of the Society of Jesus. He currently teaches psychology at Creighton University in Omaha. He is the author of Home-Going: The Journey from Racism and Death to Community and Hope (Anamchara Books).

3 Pope Benedict XVI, Apostolic Exhortation Sacramentum Caritatis (2007), accessed January 3, 2023, https://www.vatican.va/content/ benedict-xvi/en/apost_exhortations/documents/hf_ben-xvi_ exh_20070222_sacramentum-caritatis.html

“How might our lives change if each bite of bread we took, each sip of wine, each occasion of fellowship with good friends and family all served to prompt us to work harder for the unity, justice, and compassion to which we are called?”

1 lb beef stew meat

1 lb beef bones

Juice of 3 limes, divided

1 onion, chopped

1/2 green bell pepper, chopped

1 bunch scallions, chopped

1 head garlic, peeled and cloves separated

1/4 cup fresh parsley, chopped

1 tablespoon olive oil

12 cups + 1 tablespoon water, divided, plus more as needed

1 teaspoon kosher salt

2 tablespoons Creole or Cajun seasoning

1 kabocha squash

3 medium potatoes, diced

3 medium carrots, chopped

3 ribs celery, chopped

1 turnip, diced

1 large leek, halved lengthwise and sliced thinly

1 Scotch bonnet pepper, left uncut (optional)

1 extra-large chicken bouillon cube

10 sprigs fresh thyme, tied with twine, plus more for garnish

1 small head green cabbage, cut into 1- to 2-inch ribbons

3/4 cup penne or other similar pasta

For more on the significance of soup joumou within the context of the Haitian revolution, watch Liberty in a Soup (Dudley Alexis, 2016).

In a large bowl, combine the meat and bones with about 4 tablespoons of lime juice and let sit for 10 minutes. Rinse thoroughly.

In a food processor, combine the onion, bell pepper, scallions, garlic, parsley, olive oil, 1 tablespoon of water, and salt. In a large stockpot, combine the meat, bones, and herb paste. Add the Creole or Cajun seasoning, stir to combine, and let marinate for at least 10 minutes and up to 24 hours.

Without peeling, cut the squash in half, then scoop out and discard the seeds. Cut the flesh into 4–6 wedges and place on top of the meat. Add 6 cups of water and bring to a boil. Cover and cook until the squash is tender, 15 to 20 minutes. Transfer squash to a large bowl and let cool slightly. Using a spoon, scoop out the flesh and transfer to food processor. Add 2 cups of water and blend until smooth. Pour into the stockpot and stir to combine. Add the potatoes, carrots, celery, turnip, leek, and Scotch bonnet pepper, followed by 4 cups of water and the bouillon cube. Add the thyme bouquet and stir. Bring to a boil, then simmer for 20 minutes. Stir in the remaining lime juice. Add the cabbage and pasta, stir to combine, and simmer until the pasta is cooked and the cabbage is tender, an additional 15 to 20 minutes. Garnish with fresh thyme and serve hot.

Source: Jenna Chrisphonte, https://www. washingtonpost.com/food/2020/12/22/ haitian-soupe-joumou-recipe/

two-year-long drought— combined with conflict, inflation, COVID-19, and the war in Ukraine’s impact on the global food system—has pushed Somalia into a state of severe crisis. Nearly 3 million people have been displaced, and nearly half of Somalia’s 15 million people need humanitarian assistance. An estimated 1.4 million children under the age of 5 face severe malnutrition as southern Somalia has experienced a drastic rise in child and adult deaths.

Fadumo Hudow Ibrahim fled southwest Somalia after she lost her farm and livestock to the drought. “We did not receive rain for a long time. All our animals were wiped out, and we cannot even grow crops. All these tragedies forced us to move here,” she says. After traveling three days to reach the outskirts of Mogadishu, she and her family now live in a makeshift shelter.

Thousands of camps for those who have been displaced have sprung up as families like Fadumo’s are forced to move, but they are often overcrowded and have poor water systems, making the camps prone to diseases like measles and cholera.

“The situation is grim,” says Angela Muathe, a communications manager for Catholic Relief Services (CRS) in Kenya and Somalia. “There is a need for a huge response to provide food, cash, water, and sanitation services. Catholic Relief Services is already working to provide water, sanitation, and hygiene services, but the needs are immense. Displaced people are coming into camps every day, and there is so much more needed.” Somalia, where most people earn a living from agriculture and

livestock herding, has experienced four consecutive failed rainy seasons— with a fifth underway.

Along with this forced migration, some families are making the heart-wrenching decision to marry off their young daughters for food, and young men are leaving to join armed groups in hopes of having consistent meals.

On top of this devastating drought, the war in Ukraine and the impacts of COVID-19 on the global supply chain have made getting food items into the country difficult and costly. Wheat, flour, chicken, eggs, and cooking oil are just some of the vital items that Somalia imports from Ukraine every year. Since the outbreak of the war, these items have been harder to come by, making the hunger crisis caused by the drought even worse.

According to the most recent assessment by the United Nations, at least 40 percent of Somalia’s population will experience severe food insecurity before the end of the year. If lifesaving aid is not critically ramped up, famine could be declared in several districts within the next few months.

The stark reality of ongoing hunger can be seen in the Baidoa District Hospital, where mothers wait in line holding their children and waiting for them to be examined.

“The drought has taken a toll on us,” says Faiza Abdi Siyad, a mother with a severely malnourished child. “I brought [my daughter] here for treatment and medicine, and food was provided to her, and she has improved tremendously, and I thank them for that. She is now taking therapeutic food and medicine, and I thank God for the improvement.”

Children such as Siyad’s daughter could carry the health impact of these early childhood deficits for their entire lives. According to UNICEF, at least 330,000 children in Somalia need life-saving treatment for severe wasting, the deadliest form of malnutrition.

At the Baidoa District Hospital, where CRS helps run a nutrition project, new admissions of malnourished children have multiplied since May 2022. Muathe reports real benefits for those who can get treatment.

“I met two children in the hospital who had been undergoing follow-up treatment from illnesses related to malnutrition and the hospital staff told me they were improving,” she says. Adults are also responding to treatment.

“At Baidoa hospital, I met a lady who was around 60,” Muathe says. “She said the treatment had saved her life. She was extremely grateful to the medical staff. Without that treatment, she could not survive. The treatment provided to these people literally saves their lives.”

As drought ravages communities in Somalia, CRS has supported 70,000 people affected by the crisis with health care, nutrition services, cash assistance, clean water, and hygiene supplies. It recognizes the urgent need to avert famine and the devastation of livelihoods while prioritizing localized cooperative approaches that enhance social cohesion and a community’s ability to respond to future crises.

The crisis in Somalia is evidence that the growing global food crisis is getting worse, and more and more communities across the world are experiencing life-threatening levels of hunger and malnutrition on an unprecedented scale.

We are called to care for our sisters and brothers around the world. Matthew 25:40 says, “Whatever you did for one of these least brothers of mine, you did for me.” In Somalia—and so many other parts of the world—the hunger crisis continues because of forces largely out of our individual control, but our faith calls us to act, whether that is through prayer, fundraising, or advocacy.

From 2013–2018 the world spent 630 billion dollars a year to support the global food and agricultural sector. Although most of this support went to individual farmers, aid is still not reaching many farmers. In addition, these subsidies— especially in low-income countries—often target staple foods, dairy, and other animal products such as rice, sugar, corn, and meats instead of healthy fruits and vegetables. Such a narrow focus leads to environmental degradation and often prevents people from accessing nutritious food.

In addition, efforts to eliminate hunger and malnutrition stalled during the COVID-19 pandemic. The war in Ukraine, inflation, and increasing extreme weather due to climate change exacerbated the problems.

One attempt to solve some of these issues is Congress’ 2022 Global Food Security Reauthorization Act. Initiated in 2010, first authorized in 2016, and reauthorized in 2018, this act relies on a whole government approach to combat international hunger. The 2022 Act extends the USAID “Feed the Future” and “Emergency Food Security” programs through 2028, which seek to address the root causes of hunger by focusing on agriculture, nutrition, and education. This new act also improves previous versions of the bill by emphasizing sustainable agriculture and increasing the spending authorization.

While this is an important step in combatting global hunger, there is more work to be done. People can continue to advocate for global food security through prioritizing the following initiatives:

• Improving nutrition through taxing processed and sugary foods while subsidizing fruits and vegetables

• Protecting children from harmful/unhealthy food advertising

• Implementing clear, standardized nutritional labeling

• Developing a global child nutritional program

As climate change, conflict, the COVID-19 pandemic, and rising costs put millions of our sisters and brothers at risk of hunger, we are called to take action and ensure our global family members can access nutritious food to thrive.

Carlos Barrio is the East Africa Regional Communications Officer for Catholic Relief Services. Adapted from a Catholic Relief Services article: https://www.crs.org/stories/somalis-face-widespread-food-crisis

• Reallocating food and agricultural support to target fruits and vegetables in countries/regions where the recommended levels of healthy diets are not being met

“The hunger crisis continues because of forces largely out of our individual control, but our faith calls us to act, whether that is through prayer, fundraising, or advocacy.”BY KELSEY HARRINGTON

few summers ago, in the parking lot of our drivethrough food bank, a guest of our food bank brought a meal to share with our staff and volunteers. They took the food we had given them and gave it back in a meal of pure Christ-like love: giving without counting the cost, without fear of not having enough for themselves.

Agape Service Project’s food bank caters to the farm-worker community of Whatcom County in Washington. It is deeply humbling to play a role in increasing food access for the individuals who are responsible for feeding us all. It is a stark reality to offer produce to the hands that harvested mine. It is a daily reminder that food connects us all—in sacred, beautiful ways and sometimes in ways that also spark righteous anger.

An estimated 2-2.5 million people make up the farmworker population in the United States.1 This community is responsible for planting, picking, and packing almost all of the fruits and veggies that are grown in our country. They also make up the bulk of the workforce in our dairies, nurseries, and feedlots. These highly skilled men, women, and children are our

https://www.wilsoncenter.org/article/us-

neighbors who have touched our food and, therefore, have touched our lives.

Despite their dignified and essential work, these individuals and families face many injustices and frequently encounter barriers to accessing services. “Most dramatically of all,” according to Representative Joaquin Castro in America magazine, “farmworkers too often struggle with food insecurity, meaning the workers who feed America too often cannot feed their own family.” 2 Our farmworkers earn an income far below the national poverty line while working in one of the most hazardous occupations in the United States, an employment situation ripe for abuse. In addition, they are often housed in conditions that should be illegal, and many live in constant fear of deportation; these are just some of the many injustices they regularly face.

Our understanding and appreciation of supply chains drastically increased during COVID-19. For a while, in what I believe was a silver-lining to the pandemic, everyday consumers reflected on the many lives and hands that went into their ability to function: the seafarer, the grocery store employee, the mail

2 Joaquin Castro, “Rep. Joaquin Castro: It’s time for a Latino secretary of agriculture.” America Magazine, December 3, 2020, https://www. americamagazine.org/politics-society/2020/12/03/joaquin-castrobiden-latino-cabinet-agriculture-farmworkers-covid

carrier. Roles in our society that are often invisible suddenly became “essential.” But then I think many of us, myself included, unfortunately returned to life as “normal,” once again forgetting all the lives that make it possible for our items to be shipped, our food to be in the store, or our mailbox to be full.

While I am deeply familiar—and connect regularly—with the very beginning of the food chain via the agricultural system in the United States, I too fall into the robotic system that leaves me blind to the many lives that make my life possible. In a space of immense privilege, I don’t have to worry about where I access my food. This non-worry can also lead to non-intention. Do I consider the amount of plastic used to package my spinach?

Cavanagh Altar Bread, a family-owned company in Rhode Island, bakes over 850 million wafers annually, shipping nationally and internationally. Producing for the Catholic, Episcopal, Lutheran, and Southern Baptist churches, Cavanagh bakes about 80 percent of the communion bread in the United States.

Three of the largest altar wine companies in the United States are Cribari Bulk Wines, Mont La Salle Altar Wines (formally Christian Brothers), and La Salle Altar Wine (owned by Catholic Supply Company). All of these companies own or purchase from vineyards in Napa Valley. It is good to see many vineyards, especially in Napa, are moving to employment practices that honor the person who tends the vine: switching to hourly wage

Do I purchase vegetables with intention from a Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) box or farmers market? In my premeal prayers, do I give thanks to the farmworkers while giving thanks to God?

As a Catholic, I consider the Eucharist the source and summit of my faith. It is the space where I encounter and receive God as the Lover of Souls, the Dawn of Justice, the Pattern of Patience. I then go forward as a living tabernacle to infuse our hurting and hopeful Earth, communities, and families with that love, justice, and patience.

I rarely, however, stop to think about the supply chain of the Eucharist. And yet, in the same analysis and appreciation of the hands that have touched our physical food, we need to think about the hands and lives who have touched and provided our spiritual food. Is our Bread of Life produced on a supply chain of justice? Are living wages paid to each person who touches the Fruit of the Vine, from seed to altar? Are pesticides and toxic chemicals used in the industrialized growth of our Heavenly Nourishment?

When it comes to the bread and wine Catholics consume during the Eucharist, what used to be produced by brothers and nuns is now made by small and large business enterprises.

rates vs. per pound; providing child care, especially as the workforce increasingly becomes more female; offering health and wellness services and benefits; and providing more flexible work hours. Are these practices that are present in some of the smaller, high-end vineyards consistent in the bulk wine industry, as well? We need to work to ensure all vineyards in the United States are upholding the dignity of their workers, but it must come with the understanding from consumers that there is a higher cost to products produced justly.

Maybe it’s a lofty hope, but imagine the impact on the bulk wine and wheat industry if the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops asked the leader in communion hosts and top altar wine companies to uphold the teachings of dignity of work, rights of workers, and care for creation in the production of the source and summit of our faith. We have an incredible collective capacity to flip the table and infuse this small aspect of the agriculture system with Catholic social teaching.

“ Blessed are you, Lord God of all creation, for through your goodness we have received the bread we offer you; fruit of the earth and work of human hands, it will become for us the bread of life.”

“In the same analysis and appreciation of the hands that have touched our physical food, we need to think about the hands and lives who have touched and provided our spiritual food.”

In Laudato Si’, Pope Francis reminds us of the interwoven nature of all of creation: “Creatures tend towards God, and in turn it is proper to every living being to tend towards other things, so that throughout the universe we can find any number of constant and secretly interwoven relationships. This leads us not only to marvel at the manifold connections existing among creatures, but also to discover a key to our own fulfilment. The human person grows more, matures more and is sanctified more to the extent that he or she enters into relationships, going out from themselves to live in communion with God, with others and with all creatures.” 2

Food supply chains are tangible reminders that reveal our sometimes-invisible interwoven physicality, namely the Earth and its fruit, farmworkers, truck drivers, grocery store employees, and everyone else in between creation and ourselves. We are all connected through our food. The Eucharist is the

pinnacle of this interwoven experience, this interwoven spirituality. Ultimately, it is the fruit of the Earth, the work of human hands, and the divine working of God.

Christ does everything with intentionality and intentionally chose for us to receive God in the form of a human creation: bread and wine. When Catholics take Communion, we are not eating raw wheat and raw grapes; we are consuming a hand-made creation, harvested by human hands. The Earth produces, humans harvest and create, and then God performs a miracle, the totality of which lands with peaceful gravity into our hands and bodies.

Farmworkers feed us—body and soul.

Kelsey Harrington is a lifelong Pacific Northwest Catholic and finds immense beauty in that intersection. As the Director of Agape Service Project, she is humbled to encounter our farmworker brothers and sisters of Whatcom County and youth and young adults from around the Archdiocese of Seattle.

Page 10 © Katie Kolbrick Photography; Page 11 © Cornelia Schutz“Food supply chains are tangible reminders that reveal our sometimesinvisible interwoven physicality, namely the Earth and its fruit, farmworkers, truck drivers, grocery store employees, and everyone else in between creation and ourselves.”

In 2023, Congress will start negotiating a new Farm Bill. First enacted after the Great Depression, the Farm Bill was created to bring stability to U.S. food and agriculture producers, as well as protect and sustain vital natural resources. The modern-day Farm Bill is a vast spending package that is renewed every five years and addresses nutrition, forestry management, rural development, renewable energy, and more. It includes programs such as:

• Disaster assistance for farmers of major crops such as soybean, corn, sugar, wheat, dairy, rice, and peanuts

• Support for environmental stewardship and improved management of farmlands

• Nutrition assistance for low-income households internationally and in the United States through programs such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP)

• Support for rural housing and communities

• Agricultural research and forestry management

• Renewable energy grants

The current Farm Bill is set to expire in September of this year and requires bipartisan support in order to ensure the continuation of these vital programs, including SNAP, which provides aid to over 42 million households a year.

“What is the Farm Bill?” (https://sgp.fas.org/crs/misc/ RS22131.pdf)

USCCB letters and resources on previous versions of the Farm Bill (https://www.usccb.org/issues-and-action/ human-life-and-dignity/agriculture-nutrition-rural-issues/ farm-bill#tab--background-information)

Catholic Rural Life on the Farm Bill and Catholic teaching (https://catholicrurallife.org/farm-bill/)

My grandpa was one of the hardest working men I’ve ever met. When I was a child, my family moved often, both within Mexico and throughout the United States. One move I remember vividly is when we moved to Tijuana. Financially, we were dirt poor: My whole family worked in the dumps of Tijuana. We walked the streets, looking through garbage piles for cans, bottles, or anything we could sell to survive. But we were rich with happiness. I was surrounded by family, friends, and other migrants who arrived on a regular basis to cross the U.S. border in search of the “American dream.”

Every morning, I would walk holding my grandpa’s hand, and he would buy me a small carton of milk y un pan dulce, and to work we would go.

My grandpa never went to school, but he knew Bible stories and sayings that had been passed down from one generation to the next. He wasn’t a person who prayed often, but I learned so much from watching him in action. He would give away everything he owned so his loved ones could have some special moments. From him I learned that God has many ways to teach us. The question is: Are we willing to listen and live out what others teach us through action?

I remember one day, my brother Juan (Banano) was crying, because he was hungry. I saw the tears in my grandma Micaela’s eyes, as she explained to my brother that she didn’t have any food or money to buy food. He continued to cry, and I watched my grandma take off her earrings, which were made out of Canadian silver dimes. She broke off the dimes, gave them to my brother, and sent him into the store to use the dimes to buy a piece of meat.

Later, I moved with my mom to different towns in California, Oregon, and Washington to be closer to our relatives. We moved often, looking for work and a better life—it was not easy. My mom was a single mother, and she held many different jobs. Often she would work in the field during the day and at other jobs in the evening. During the summer, my brothers and sisters and I all worked in the fields. We put our money together to help Mom pay bills, and we saved money so we could survive the rest of the year. But even though we were poor, we didn’t realize it at the time. My mom was always finding other migrant workers living in their cars or in parks. I remember one night, while we

were living in a one-bedroom apartment with our large family, she showed up with 10 other kids and their parents. They lived with us for a few months until we were all kicked out.

From my grandpa, grandma, mom, and the rest of my family, I learned the truth of Matthew 25:31-46. In that passage, Jesus tells us, “As you did it to one of the least of these brothers and sisters of mine, you did it to me.” It is not hard to remember Bible verses, but it is hard to apply them to our lives if we haven’t learned them by watching others’ actions along the way.

I’ve had the privilege of having many unsung heroes, role models, and friends who have taught me how to live the gospel and held me accountable. A priest at my local parish, Padre Miguel, was one of these role models. He adopted my family and took us in like we were part of his own. He brought us food, money to help my mom pay the bills, and Christmas toys. One day, he asked if I could join him to visit the families in the migrant camps.

Today, my work has taken me to see migrant families on the move from our borders to the Seattle Archdiocese and Skagit Valley. I’ve seen children without food, clothing, or housing. I’ve become closer with God, not only because I learned more about our faith but also because of the actions of Padre Miguel and others I’ve met.

One day, at the end of a retreat, I found myself in tears while praying to God. I asked God, “If you are real, come down from the cross and hold my hand. Guide me. I don’t know how to follow you or do your work here on Earth.” I didn’t realize that God had been guiding me since I was born through my family, friends, and great heroes. I have learned my faith through prayer and action. The challenge is not to only learn about injustice or see the needs of the world; it is to apply what we have learned.

“It is not hard to remember Bible verses, but it is hard to apply them to our lives if we haven’t learned them by watching others’ actions along the way.”

Established in 1981, the Youth Migrant Project (YMP) is based out of St. Charles Catholic Parish in the Skagit River Valley in Burlington, Washington. St. Charles runs the tri-parish food bank as well as a lunch program for children of migrant farm workers, which provides food to more than 400 families each week and delivers lunches to more than 100 kids each day. Middle- and high-school students spend a week supporting the food bank in the summer by making deliveries, working in community gardens, and building relationships with the farmworker community.

A social ministry of the Archdiocese of Seattle, Agape Service Project encounters the farmworker community of Whatcom County, facilitates week-long middle- and high-school service-immersion, and empowers young adults to be servant leaders. Through service-learning experiences, participants learn about human dignity, issues affecting farmworkers, and how Catholics are called to serve. In 2022, Agape increased access to culturally appropriate foods for an average of 439 families weekly through their seasonal mobile food distribution and food bank. Through the food bank, community support, and time spent with the migrant families, Agape aims to build personal relationships with our brothers and sisters in Christ.

IPJC is excited to announce a new collaboration with the Youth Migrant Project and Agape Service Project. In 2019, seven educators from Jesuits West came together to create a summer youth organizing seminar, Ignite. After two years of meeting online and a pause last summer to discern the future of the program, IPJC is honored to take on the program in a new way. In July 2023, we will welcome 80 high school juniors and seniors and 20 adults from 10 Catholic schools from across the West Coast to the Skagit Valley and Whatcom County. During their time here, students will build community, encounter the farmworker reality, learn about the farmworker movement, and develop faith-based community organizing skills to grow in their capacity as social justice leaders in their schools and community. We are humbled to walk with and learn from the farmworker community!

Registration for Ignite will open soon, subscribe to our email list to receive more information: https://ipjc.org/signup-for-our-e-newsletter/

The divine Persons are subsistent relations, and the world, created according to the divine model, is a web of relationships. Creatures tend towards God, and in turn it is proper to every living being to tend towards other things, so that throughout the universe we can find any number of constant and secretly interwoven relationships. This leads us not only to marvel at the manifold connections existing among creatures, but also to discover a key to our own fulfilment. The human person grows more, matures more and is sanctified more to the extent that he or she enters into relationships, going out from themselves to live in communion with God, with others and with all creatures. In this way, they make their own that trinitarian dynamism which God imprinted in them when they were created. Everything is interconnected, and this invites us to develop a spirituality of that global solidarity which flows from the mystery of the Trinity.

(POPE FRANCIS, LAUDATO SI’ )The articles in this issue are a reminder that while everyone’s experience of food is deeply personal and influenced by their unique family heritage and social location, food is also what connects us to other humans across the globe, to creation, and to God. As you read these articles, reflect on the following:

n Is there a food that is important to you? What memories or feelings does this food evoke? Why is it so significant?

n What does the word communion mean to you?

n Can you think of a meal or eating experience where you felt truly connected—where you have felt drawn into the relationships Pope Francis talks about in the quote above?

n Do you know where your food comes from? When you think about the people who grew, harvested, baked, butchered, or otherwise produced your food, does that change how you think about it? Will you make different choices around food because of these people? How so?

n Do the stories in this issue call you to any sort of action? What might that look like in your life?

The Youth Action Team interns completed the fall semester of their internship in mid-December. During the fall, the interns expanded their relational, listening, and communication skills through workshops and community outreach. In October, the interns hosted an event that allowed them to practice one-to-one relational skills with Seattle-area community organizers. It was an inspiring event that allowed the interns to realize their collective power. In October and November, the interns gathered experiential data from and built relationship with the community by inviting roughly 80 diverse individuals to participate in one-to-one conversations.

In October, the interns hosted an event that allowed them to practice one-to-one relational skills with Seattle-area community organizers.

Data gathered from these one-to-ones was utilized in December for the interns’ discernment process in selecting a justice issue to build a movement around during the spring semester.

Follow IPJC on Facebook and Instagram (@IPJCseattle) to see profiles on each intern and get updates on their work!

When we were not working diligently towards justice, we built relationship and had fun together! The interns and co-facilitators enjoyed an adventure to an escape room to celebrate the completion of one-to-ones and the Thanksgiving holiday.

Season three of the Justice Rising Podcast concluded in December. Justice Rising’s host, Cecilia Flores, brilliantly interviewed guests while creating brave spaces where guests were able to vulnerably share their diverse identities and visions for justice in the church and world. The podcast will continue in the spring and focus on the principles of community organizing. Listen as Cecilia invites community organizers to share their wisdom of the organizing cycle and experience from the field!

Catch up on season three, concentrated on cultural identities and justice, at ipjc.org/ justice-rising-podcast/.

During the 2023 Proxy Season, NWCRI members filed 45 shareholder resolutions and engaged in 27 dialogues with company executives. Areas of focus for the proxies include: impact of patents on access to medicines, racial equity audits, ending child labor in cocoa, child safety on mobile media apps, worker wages and health and safety, and methane emissions and financing of fossil fuels.

On September 17th, IPJC’s Justice for Women program, guided by their Leadership Advisory Team, organized Semillas de Cambio, a gathering of current and former Circle facilitators and participants. As a result of this gathering, the Justice for Women Facilitator Network was formed. On January 24th, the network had its first meeting cofacilitated by the Justice for Women Advisory Team. The network, with 22 Latinas from 18 cities, will meet quarterly. During this first meeting, the facilitators will have the

On September 27th, leaders from the South Seattle Deanery’s Racial Committee, members of the South Seattle parishes, and leadership from the North Seattle Deanery Racial Solidarity Network—of which IPJC is a member–convener—gathered at Immaculate Conception Catholic Church for a workshop titled, “Introduction to the Racial Sobriety Approach.” Deacon Alfred Adams, Sr. from Baton Rouge guided participants through self-reflection and group discussion and provided an opportunity for honest conversation about race and racism. This workshop is one way the South Seattle Deanery is living out its commitment to racial solidarity and dismantling the history of racism in the Catholic Church.

opportunity to form relationship, build a brave and trusting space, create and define the vision of the network, and begin setting short and long term goals for the network. Members of the network will have the opportunity to receive leadership training, strengthen bonds of fellowship and sisterhood, and amplify the voices of the communities they serve.

NW Ignatian Advocacy Summit

IPJC, in partnership with Jesuits West and Gonzaga University, will host the Northwest Ignatian Advocacy Summit from April 13th to 15th at Gonzaga University in Spokane. This conference offers the opportunity for Northwest area high school and college aged students to learn advocacy practices, participate in legislative meetings, and collaborate with the broader Spokane faith community for an action day. Learnings from this

summit will set the foundation for participants to return to their communities and continue justice and advocacy work!

SAVE THE DATE!

IN HONOR OF Judy Byron, OP Diane Desmarais

Damon Desmarais

Sr. Sharon Park

Adrian and Tacoma Dominicans

IN MEMORY OF Leslie Grace

Sr. Virginia Pearson

Joan Trunk

Intercommunity Peace & Justice Center

1216 NE 65th St Seattle, WA 98115-6724

SPONSORING COMMUNITIES

Adrian Dominican Sisters

Congregation of the Sisters of St. Joseph of Peace

Jesuits West

Sisters of the Holy Names of Jesus and Mary, U.S.-Ontario Province

Sisters of Providence, Mother Joseph Province

Sisters of St. Francis of Philadelphia

Tacoma Dominicans

AFFILIATE COMMUNITIES

Benedictine Sisters of Cottonwood, Idaho

Benedictine Sisters of Lacey

Benedictine Sisters of Mt. Angel

Dominican Sisters of Mission San Jose

Dominican Sisters of Racine

Dominican Sisters of San Rafael

Sinsinawa Dominicans

Sisters of Charity of the Blessed Virgin Mary

Sisters of St. Francis of Redwood City

Sisters of St. Joseph of Carondelet

Sisters of St. Mary of Oregon

Society of the Holy Child Jesus

Sisters of the Holy Family

Sisters of the Presentation, San Francisco

Society of Helpers

Society of the Sacred Heart

Ursuline Sisters of the Roman Union

EDITORIAL BOARD

Gretchen Gundrum

Vince Herberholt

Kelly Hickman

Tricia Hoyt

Nick Mele

Catherine Punsalan-Manlimos

Will Rutt

Editor: Emily Sanna

Copy Editor: Gretchen Gundrum, Elizabeth Bayardi

Design: Sheila Edwards

A Matter of Spirit is a quarterly publication of the Intercommunity Peace & Justice Center, a 501(c)3 nonprofit organization, Federal Tax ID# 94-3083964. All donations are tax-deductible within the guidelines of U.S. law. To make a matching corporate gift, a gift of stocks, bonds, or other securities please call (206) 223-1138. Printed on FSC® certified paper made from 30% postconsumer waste.

Cover: © Katie Kolbrick Photography, details see Page 8; Back Cover: freevectormaps.com

ipjc@ipjc.org • ipjc.org

We are hungry. We are eating our daily bread and bowing our heads and yet we are hungry. We are thanking the farmer and the farm worker and yet we are hungry.

We are speaking in spaces for food that is healthy and still we are hungry.

We are tiring of slogans that say Feed the Children and mean feed the children leftovers.

We are hungry for something that feeds more than bodies. We are hungry for help.

Help us oh you who apportion the funds. Find in your hearts the child who you were who would share with a friend free and friendly. Lead us not into meanness. For we are the hungry. We want the loaves and the fishes the water and the wine of sweet justice for all. We are hungry.

BY DEBRA SMITHSOURCE: https://www uua.org/worship/words/meditation/prayer-addressing-all-hungers