15 minute read

A Place Apart

BY LLOYD GORMAN

Advertisement

Woodman Point in Coogee, about five miles south of Fremantle, has a long history of dealing with pandemics and contagions. It was built as a quarantine station at the waterside Munster location in 1886 to isolate people with or at risk of diseases such as leprosy, bubonic plaque smallpox. It was used to help contain the spread of the Spanish Flu towards the end of World War I, and for some time afterwards. From about mid 1918, returning servicemen and women from the war were held at the centre for a full seven days before they were able to go back into the wider community.

An isolated incident? Western Australia’s only Irish-born holder of a Victoria Cross medal, Martin O’Meara [who single-handedly and at great personal risk brought some twenty five wounded Australian soldiers and officers from no-man’s land on the Western Front to the safety of their own trenches] was one of the many diggers quarantined at Woodman Point. As it happens, O’Meara’s time there coincided with an historic moment in world history and one that also proved to be a tragic turning point in his life. Thanks to the book about O’Meara “The Most Fearless And Gallant Soldier I Have Ever Seen”, by Perth man Ian Loftus, we know that O’Meara left for Australia from Liverpool onboard the troopship Arawa in September 1918. It also shows that while on board the Irishman filled out a registration form with the Australian Government’s Repatriation Department, in which he indicated he wanted to return to his job as a railway cutter, or as a farmer, after his discharge from the Australian Imperial Force. “Importantly, the form did not indicate that O’Meara had any health problem,” Loftus writes. On its journey to Australia, the Aruwa sailed off the coast of Africa and reached Cape Town in October. While fresh supplies were taken onboard, the ship’s passengers were not allowed to disembark because of a ‘pneumonic influenza’ outbreak in the city. Their next port of call was Fremantle, where they arrived on the morning of November 6, 1918 - which just happened to be O’Meara’s birthday, he had just turned 33. There had been cases of flu on the voyage but these were quickly stamped. “The men were quarantined despite the AIF medical officers onboard the Aruwa advising that there were no longer any cases of influenza aboard,” Loftus writes. “Five men were admitted to the quarantine station’s hospital - one suspect case of influenza and four ‘other complaints’ - on November 7, but two days later at least some of them had been discharged.” On November 8, the West Australian published an article based on an interview with O’Meara, probably conducted the previous day by telephone. As a Victoria Cross recipient - and certainly the only one who was on the Aruwa - O’Meara would have a certain Top: Woodman Point in Coogee. Above: Martin O’Meara

status in Australian society, and his arrival would have been newsworthy. [Two local civic receptions were organised for the Victoria Cross holder - attention O’Meara would not have been uncomfortable with.] The article - published here in full - is significant for another reason. It offers a precious and rare glimpse into his state of mind at what was a critical time for him.

November 8

BACK IN WESTERN AUSTRALIA

AN INTERVIEW BY ‘PHONE Acting-Sergeant Martin O’Meara, one of Western Australia’s Victoria Cross winners, has returned home after an absence of over two years on service. He is at present in isolation at Woodman Point where he is spending seven days as a precautionary measure to keep Spanish influenza out of the State. Yesterday through the courtesy of Mr. T. Bucknell, officer in charge of the quarantine station, a representative of the ‘West Australian’ was permitted to interview Sergeant O’Meara over the telephone, the result being the following interesting story of the hero’s war experiences. “I was born in Tipperary 34 years ago this month,” he said, “and I came out here in 1911 like a lot of other young Irishmen had done before me, to try my luck in Australia. I spent a couple of years in South Australia, but in 1914 came to the West and settled in the bush about 34 miles out from Collie. Yes, I was sleeper cutting. In August 1915, I got into khaki and in December of the same year I left with the 12th reinforcements of the 16th Battalion, and in the following August went into action at Mouquet Farm. That was my first experience of war, and it was pretty hot, too, I can tell you. We were carrying up ammunition under heavy shell fire—a sort of fatigue party—and of course a lot of fellows were wounded. I went out to do what I could for the poor chaps that were lying all around waiting for the stretcher bearers and helped a lot of them to get in out of danger. I went down to the cookers and got some hot tea and went out again with a stretcher and brought in more. Then I got a slight stomach wound, and they told me I was recommended for the Victoria Cross for something that had happened during the time from the 8th of August until the 12th. I suppose it was for fetching in those wounded officers and ‘diggers.’ You see, after the first day’s fighting and while I was out on my own, the battalion was relieved, so I just stayed there by myself doing this little job. “After I got hit I walked back to the dressing station and, to cut things short, soon got over to Blighty. I had about four months in hospital and then went out to France again and had put in about seven months when I was sent to London on special duty, and then the King gave me the Cross. That was on July 21, 1917. Then after I had a look round the place I went back to France and was only there a couple of days when in the fight at Messines I ‘went out’ to a wound on the hip and was sent back to England to be patched up and here I am in quarantine. “Where is my home? Why, I haven’t one. Under any old gum tree I suppose is the best way to describe it. No, I’m not married, and this place’ll do me ‘for the duration.’ We are quite comfortable and happy, and I don’t care when the doctor sees me.”

THE IRISH SCENE | 15 While we cannot know the mood or spirit O’Meara was in at the time of the interview, his answers to the journalist do not at least on the face of it suggest this was a man with a tortured soul or a wounded mind. “Martin O’Meara had some sort of serious mental breakdown, at Woodman Point between 8-13 November 1918,” Loftus writes. “A lack of surviving records and a broad media ‘silence’ on mental health issues at the time made it difficult to accurately determine what actually happened. The Calland WA Sportsman reported that, without being specific about the nature of his illness: Continued on page 16

“After being released from quarantine at Woodman Point, Martin O’Meara V.C. was so unwell that he was detained for treatment at another hospital. We understand his case will require careful consideration from specialists for some considerable time.” O’Meara never recovered. He spent the rest of his life between various local mental institutions and hospitals until he died in 1935. When it became known this decorated war hero had spent 17 years in a straitjacket, a parliamentary inquiry was launched, but was of no help or benefit to O’Meara. He died just before Christmas in Claremont Mental Hospital and was buried in a Catholic plot at Karrakatta Cemetery with full military honours. His coffin was carried by three other VC’s and his funeral was given by a Fr. John Fahey, another native of Tipperary. The fact that O’Meara’s sudden mental decline occurred almost simultaneously with the official end of World War I, on November 11, Armistice

Martin’s VC will linger longer in Ireland In what was a first for any Australian Victoria Cross - new legislation had to be put in place to facilitate it - Martin O’Meara’s medal was allowed to leave the country on loan to the National Museum of Ireland. The loan was originally meant to last for 12 months, after which his VC was to return to its permanent home at the Army Museum of Western Australia, in Fremantle around the end of July. But the museum has confirmed the loan to Martin’s native country will have to be extended as a result of the panemdic. With the Collins Barracks museum closed for the foreseeable future however, the medal will be displayed in the isolation of silence.

Day (now called Remembrance Day) makes an already distressing story even more poignant.

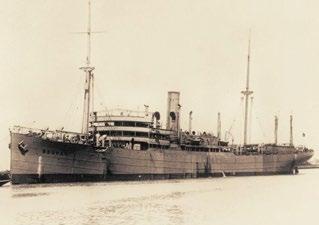

Crisis point at Woodman Point Just weeks after O’Meara was discharged from Woodman Point, the quarantine station was thrust into the heart of a remarkable row that has echoes of today’s controversary around unwanted cruise liners in Fremantle and Sydney. The Boonah, the last Australian troop ship, left Fremantle in October 1918. She carried about 1,200 soldiers destined for the conflict in the Middle East. Expecting to stock up with supplies, the Boonah arrived into Durban, South Africa but found that just three days earlier the war had ended with the signing of the Armistice. The ship turned around almost immediately to return home to Australia, stopping only to take on fresh supplies. The problem however, was that the local dockers who loaded the Boonah also brought the Spanish Flu onto the ship with them. When it reached Fremantle on December 12, more than 300 cases of flu had been reported. Perhaps fearing the station would be overwhelmed by such numbers, authorities refused permission for the soldiers to disembark. After a stand-off, the ship was allowed to anchor in Gage Roads - an area in the outer harbour area of Fremantle Harbour - where the 300 sickest men were then taken to Woodman Point. Three of them died on the first day. Extra help with the large numbers of sick soldiers and sailors came from another Australian troop ship that had just returned just ahead of them. “The troopship Boonah was two days behind us and we picked up her wireless messages nightly, detailing the daily increasing number of men suffering from pneumonia influenza,” commanding officer, P.M. McFarlane of the Wyreema wrote. “The Western Australian Commandant asked me to land twenty

nursing sisters at the Quarantine Station. Volunteers were called for and there was not only a ready response but so many offered that it was necessary to place the names in a hat and draw the twenty required. They knew perfectly well the enormous risk they were taking. Yet they were eager to undertake the work and those whose names were not drawn were disappointed.” In all, 27 servicemen from the Boonah and four of the twenty nurses who were infected - army staff nurses Rosa O’Kane, Doris Ridgway and Ada Thompson, and civilian nurse Hilda Williams - from the Wyreema died as a result of influenza at Woodman Point during the crisis. Another fascinating aspect of this crisis was the fact that the rest of the passengers and crew were left languishing onboard the Boonah. To prevent the spread of further cases the ship was put into lockdown, which would not be lifted until seven days had passed with no new infections. But of course the cramped and close living conditions were a perfect breeding ground for disease, and infections continued, leaving the men trapped in a never ending hell. As more men became sick the situation worsened, there was public outrage but the state and federal authorities bickered for nine days about what to do. Tensions increased to the point where the Returned Service League threatend to storm the ship and release the men by force if necessary. Eventually the Boonah was allowed to carry on to another facility, similar to Woodman Point, the Torrens Island Quarantine Station, north of Adelaide, with 17 more cases confirmed on the way, but no new deaths. The troubled troopship Boonah

Most of the facilities and buildings at the Quarantine Station were built after World War I, but the place still has at least one reminder of that episode. The address of the station is 74 O’Kane Court, Munster. It is named after Sister Rosa O’Kane, one of the four nurses who lost their lives at that time and who is buried on the grounds, where a monument was also erected in her honour. Not long after she volunteered to look after the sick Second Lieutenant, Sister Rosa O’Kane died. She was just 28 when she passed away on December 21. She had set out on her war service just eight weeks earlier. Most of the dead - including the nurses - were buried in a bush grave site at Woodman Point at the time, but in 1958 most of the service personnel were exhumed and re-interred at the Perth War Cemetery in Nedlands. Only the remains of O’Kane and Williams remain at Woodman Point. Rosa’s mother Jeanie O’Kane in Charters Towers did not want her daughter’s remains disturbed and refused to give consent for her to be moved. Her mother described her daughter as “a fine type of Australian girl, of marked ability and a girl of great possibilities had God spared her life.” We know from Jeanie’s obituary in the local newspaper (The Northern Miner) in Charters Towers, Queensland, in July 7, 1936, aged 77, that: “Mrs. O’Kane was a native of Balleymoney, Antrim, Ireland, where she was born in 1859. Together with a Citizen O’Kane

Sister Rosa O’Kane

sister and a brother, she made the voyage to Australia to join another brother, who, years before, had successfully settled at Maryborough. Educational qualifications she had acquired in Ireland earned her an early appointment to the Queensland Educational Department staff, and it was as a schoolteacher that she came from Maryborough to Charters Towers Continued on page 18

in the course of 1879, when the goldfleld was in a very early stage of development. In less than two years she had met and married her namesake, Mr. J. G. O’Kane, and together they found happiness and prosperity in the pursuit of journalism. “She gave two of her three only children, Mr. Frank and the late Sister Rosa O’Kane, to Australia in the last war, on the return from which her daughter sacrificed her own life in humanitarian nursing service at Woodman Point, West Australia. The death of Rosa was, perhaps, the greatest swordthrust of sorrow that the old lady ever bore. From that moment in 1919 until the day of her death, Mrs. O’Kane idolised the memory of the fine daughter who gave her life for her country. Mrs. O’Kane was in every respect a “war mother,” and no cause was ever so dear to her as that of the digger or the nursing sister. As each year passed she was an outstanding personality among those who organise the annual dinner in honor of soldiers on Anzac Day, and the aim or unanimity in public commemoration of Anzac Day was an objectlve for which she was an unceasing champion.” For many years afterwards, nurses and others would meet at the bush grave in Woodman Point on Anzac Day to remember Rosa. The monument there was commissioned and paid for by the people of Charter Towers. Sister O’Kane also had Irish heritage on her father’s side as well. Her grandfather was Thadeus O’Kane, a fascinating firebrand newspaper man with a colourful past and career, which merits a story of its own in another Irish Scene, or certainly worth a quick Google. Thadeus was born Timothy Joseph O’Kane in January 1820 in Dingle, Co. Kerry. He had two daughters and a son, who followed in his father’s footsteps and ran the Daily Northern Miner newspaper. Rosa was born the same year her grandfather died, but considering what a strong character this proud Irish man and Republican was that it is unlikely his legacy was not passed down through his son, Rosa’s dad, and onto her.

Splendid isolation Woodman Point ceased to be a quarantine station in 1979, when it became a holiday camp for groups, which is still run today by the Department of Local Government, Sport and Cultural Industries. Tours and other activities are organised by the Friends of Woodman Point - a not for profit group of dedicated volunteers who are passionate about promoting the heritage facility’s unique history. They also work to preserve it. Last August the group helped coordinate repairs to Army Nurse Rosa O’Kane’s grave and headstone. Families with a connection to Woodman Point sometimes call in. In October 2019 Stephen O’Kane, a great nephew of Sister O’Kane, and his wife paid their respect at her graveside. The great-nephew of Sister Ada Thompson, who died there during the Boonah crisis, also visited in December. In January a Dr Glenn Davies, from Queensland, and his wife, who is considering writing a biography about Rosa O’Kane, visited and around that time too a headstone for Nurse Hilda Williams - who also died during the Boonah crisis - was erected at her grave, 101 years after her death. A recently installed model replica of the Boonah, a busy bee to spruce the place up and newly acquired artefacts from that era had all been completed when COVID-19 hit. On March 14, Friends of Woodman Point Recreation Camp announced heritage tours at the site would

A tribute to the nurses of Woodman Point

be suspended until further notice. “This is due to the current situation in relation to the Coronavirus problem,” the group said on its Facebook page. “This suspension is in line with the Heritage Council who have done the same, to protect the public and also their volunteers. We will advise when tours will start up. Thank you.” Stephen O’Kane shared his thoughts on the issue on the Facebook site of the Friends of Woodman Point. “Then as now, our doctors, nurses and emergency services protected Australia,” he said. “A big shout out to all essential services workers, especially Coles and Woolies workers, continuing the legacy of the past.”