Helpless Intruders in a Strange World Heather Altfeld

Helpless Intruders in a Strange World Heather Altfeld

Editor-in-Chief

Leslie Jill Patterson Nonfiction Editor

Elena Passarello Poetry Editor

Camille Dungy Fiction Editor

Katie Cortese

Literary Review Fiction Trifecta

2016

Managing Editors

Joe Dornich Sarah Viren Chen Chen

Associate Editors: Chad Abushanab, Kathleen Blackburn, Margaret Emma Brandl, Rachel DeLeon, Nancy Dinan, Allison Donahue, Mag Gabbert, Jo Anna Gaona, Colleen Harrison, Micah Heatwole, Brian Larsen, Essence London, Beth McKinney, Scott Morris, Katrina Prow, MacKenzie Regier, Kate Simonian, Jessica Smith, Amber Tayama, Robby Taylor, Jeremy Tow, and Mary White. Copyright © 2017 Iron Horse Literary Review. All rights reserved. Iron Horse Literary Review is a national journal of fiction, poetry, and creative nonfiction. It is published six times a year at Texas Tech University, Lubbock, Texas, through the support of the TTU President’s Office, Provost’s Office, Graduate College, College of Arts & Sciences, and English Department. Photography: Byron Wolfe Sculpture: Sheri Simons

Helpless Intruders in a Strange World

These things I remember as I pour out my heart. —Psalm 42

Did you come by photograph or train? —John Berger

I. The object of sadness is always closer than it appears.

II. Seven years ago, in the tundra of Siberia, a reindeer hunter found the small body of a mammoth—mamont, in Nenet— frozen in ice, pickled in her own breath, sleeping in the black permafrost for 41,000 years— even her eyelashes were still there, her milk-tusk, the gentle fine fur of her small ears prickling at the sound of human song. She sledged through the ice and fell prey to the bluffs, to the wet earth, to snowmelt, her belly still shard-full of frozen mother’s milk. They named her Lyuba—love, in Russian— to honor her small form, the terrible helpless wail her mother must have sounded as her baby became a blink, drowning slowly in the underworld.

III. Folded miles of a map and sixty years away, a little man who liked cakes wandered the tundra of Vladivostock transit camp, Eastern Siberia, picking through the garbage, composing poems to the black stars sleeping in their dark nests. Emptiness, I accept your strange and sickly world. On the other side of the tundra, his widow wept and sang, wept and sang his songs. Each execution, sweet as a berry, Mandelstam wrote of Stalin’s delicate manners, even in matters of death. At find-a-grave.com, there is a search box for names, and a “find a grave store” link on the left-hand side of the page. Mandelstam’s body, it tells us, was reportedly lost or destroyed. Like a package en route from one destination to another.

IV. Here is the shadow that walks behind us. Here is the one who walks ahead. Here is the one who walks beside us, holding our hands in grief.

V. Each one of us has a tiny harp inside our ear. First tuned with the heart, then with chants, then with pipes made of deer bones and bear bones, then with the mimicry of birdsong. In Papua New Guinea, the Kaluli sing gisalo, a type of poem in which the singer tonally imitates weeping. He sings until his song hardens into the likeness of a bird. He sings until he moves his audience to tears. He sings until finally he becomes a bird. He is one who walks beside us.

VI. The first recordings of sound were undulations traced on blackened paper and glass with pig bristle, the oldest of which, still audible, is described as a lively song from a comic opera, entitled Vole, petite abeille. “Fly, little bee.� Soot transmitted voice, but could not yet return it to our ears. How, then, did melody get transported from one world to the next? In the mouths of the living, or the pockets of the dead? There are still songs to be sung on the other side of mankind, wrote Celan, years after his mother was shot in the head in a labor camp and just a bit of time before he threw himself into the Seine. In the end, he wrote this: language remained, not lost, in spite of everything, but it had to pass through its own answerlessness, through the thousand darknesses . . . it passed through and gave back no words for that which happened; passed through, and yet it could come to light again. As though he, too, could resurface, bobbing in the river’s light, buoyed by the watery leap.

VII. Goodbye, little bee.

VIII.

Antiphanes tells the story of a country where the winters were so harsh that w heard. As warm weather arrived, the people found out what had been said m his wife in the loud winds of mid-December. “The fur you gave to me last Au her pocket. When summertime arrives, these endearances find their ears, and returned to the air, like kites.

words spoken during the coldest months froze in mid-air before they could be onths ago. “I love you as much as I love cherry-blossom tea,� shouts a man to ugust is full of burrowing mice,� says his wife in late winter, pulling a tail from they pack to go visit the sea. Their sounds and their songs recorded by air, and

IX. Modern nostalgia, Svetlana Boyd tells us, is the mourning for the impossibility of mythic return. This is what walks behind us. During the three years he spent living at the Hearst Museum, almost a hundred thousand visitors came to watch Ishi, the “world’s least civilized man,” drill fires and hone wood for a bow and arrow. A handful of his stories were recorded on wax cylinders, spoken in the lost tongue of Yahi, a language no one else alive still spoke. Recordings can be purchased at wildstore.wildsanctuary.com, where there is a note that reads: NOTE! This is an archival recording—over 100 years old! Many of the unwanted surface noises, clicks, and distortions of the original, century-old recordings have been reduced; what breaks through is Ishi’s own remarkable voice—emerging, like an echo, from the past.

X. When he went to the jail to see Ishi for the first time— listed in the jail log as “Indian, Wild,” Waterman wrote to Kroeber: This man is undoubtedly wild. . . . And phonetically, he has some of the prettiest cracked consonants I have ever heard in my life. They brought him to Berkeley on a train— the first Ishi had ever seen—from the depot in Oroville, now a shit-bar on the wrong side of the tracks, serving nachos and cheap beer. Our minds cannot unwind the songs he sang to himself in those years of silence.

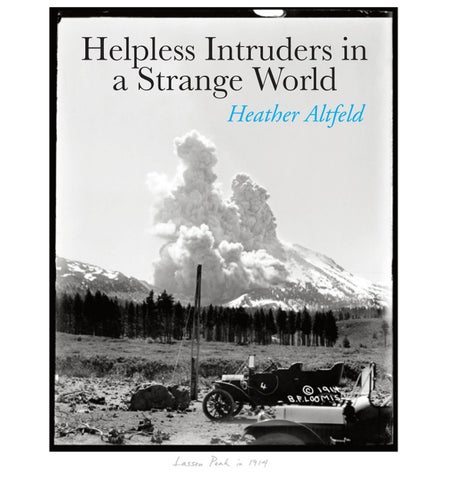

XI. Did you come by photograph or train? John Berger asks one of his dreams in A Seventh Man. This poem arrived by train, late in the night, rattling the tracks. This dream arrived by photograph: A man watching Mt. Lassen begin to bloom snaps a photograph with the sky leaning in the backdrop. The mountain and the sky and the man are all on the verge of explosion. A hundred years later, the man stops by and snaps another photo, only this time the photo is mountainless; a thick and querulous pine has obscured the view. It is the same man with the same footsteps and a different eye in his camera. A hundred years from now, he will stop by again, but there will be no sign of the pine, only the artifact of the tree, shaped as a puddle of ash and the vault of the mountain, looking almost as it did before the photo that arrived in a dream. Often the object of sadness is actually closer than it appears.

XII. Nostalgia, writes historian Michael Kammen, is history without guilt. It is the pleasure and delight of snow without the labor camps lining the Siberian front. It is the fine workmanship of a salmon spear without the silence endured for three years alone in the wilderness. It is the soft ear of the baby mammoth without the startled cry as she is sucked into the muck of the beyond. We cannot unwind the sorts of prayers that must come from such silence. What we hold dear is the sobering news of Before and the elegant expanse we imagine will be After. All that walks ahead holds our hands with such sweet and endearing pleas.

XIII.

Remember the long, brave flight Amelia Earhart took solo over the Atlantic? books. She is very tall. Please know I am aware of the hazards, she assured citize to hear the sound of her plane as it disappeared into yesterday, the panicked s ning on line, north and south, she called out. We must be on you, but we cannot se as the plane trembled into the long nothing; rainshowers eluded the celestial na land. There is no official position on her very last transmission. We can’t be sure transcript of her distress, the demarcation of her disappearance. The website C at Night displays a cenotaph of her in Pacific Grove, located in the Portal of t confident in her impending aviation, in the steadiness of flight.

Her photo smiles at us from the history textens of earth prior to departure. It is impossible soundless sound of her vanishing. We are runee you. Gas is running low. The black stars slept avigation of Howland Island where she was to e. Earnest historians attempt to reconstruct the Celebrity Burials: Where the Stars Don’t Come Out the Folded Wings. She is beautiful and bronzy,

XIV. Scientists tell us that the world beneath this one— the internal biomass, the innards, the Verne-land —might be bloated with as much life as the one we can see on the surface of the earth. We cannot stop looking for what we cannot see. A group of students found the molar of a Columbian mammoth just one sleep from the spot where Ishi lived on Deer Creek. As they dusted and cleaned the find, it disappeared right in their hands, right on the table in front of them—vanished into the stainless steel, a crumbled puddle of dust. Imagine it, that tooth beneath your hand, turning to ash. Like the life that came before that you can never find, like the agony going on beneath us, shuddering under our shoes. Tundra, song, flight. Ice floes and a steady diet of elephant seals. In the end, we are just a long endurance of wits.

XV. In his memoirs, Ernest Shackleton writes, We were helpless intruders in a strange world, our lives dependent upon the play of grim elementary forces that made a mock of our puny efforts. This was after The Endurance drifted and slipped, drifted and slipped, until it was entirely beneath them, and the sixty-nine dogs they brought with them became the quiet fluff of glacial meringue. Beneath the silvery clouds, locked in the madness of ice, the men stayed sane with songs and skits and the dream of a book, even when the ink froze during etchings and the paper was dusted with soot. The Shackleton Way is a now an internationally recognized trademark. It bears the insignia of leadership required to resonate with executives in today’s business world. Specifically, an energy company in his name aims to extract ice from the moon. Should other volatiles, like ammonia or methane be discovered, they, too, will be processed into fuel, fertilizer, and other useful products.

XVI. It is such a long journey, my sweet dreamer. It is all still so much farther away than we imagined when we first departed. There is still such sadness ahead in the eaves, so much flight to be found in the sky, such longing still trapped in the permafrost. How can anyone be sleepy when the world is melting? my daughter asked when Elizabeth Kolbert spoke to us late in the night of ice caps and antifreeze and the paralysis of apathy. There is still so much to remember that our puny hearts grow weary of pouring themselves out by day and refilling with tremors by night.

XVII. Perhaps it is time to rest for a while.

XVIII. So sleep, sleep, sleep, little bee. Sleep, and wake a hundred million years from now, from beneath the blanket of cement or the plot of ice where your bones lay exposed, pocked by the constant rains. Let them caress your ears and measure the distance between your teeth. Let them find the shards of mother’s milk in your belly, and the cemetery of your memories, the ones you lived and swallowed, the ones you photographed or wore on the train with your pearls. Let them hear the songs you dreamed or thought you dreamed, the ones you sang like a chickadee or a wood thrush, the songs that hardened you into a bird, singing from a single pine that stands at the base of an invisible mountain, bringing us all to our knees with tears.

Heather Altfeld’s first book, The Disappearing Theatre, won the Poets at Work Book Prize, selected by Stephen Dunn. Her poems have appeared in Narrative Magazine, Pleiades, ZYZZYVA, Poetry Northwest, and others. She won the 2015 Pablo Neruda Prize for Poetry with Nimrod International Magazine of Poetry and Prose. Her current research and areas of interest include children’s literature, anthropology and poetry, and things that have vanished. She lives in Northern California and teaches in the English Department and the Honors Program at California State University, Chico, and is a longtime member of the Community of Writers at Squaw Valley. Helpless Intruders in a Strange World, she says, was “an effort to capture and connect the spindly threads of conversation that had been happening between myself and the group I have been a part of for the last five years. We call ourselves: ‘Vanished’ and the subtitle of our project is, ‘A Chronicle of Loss and Discovery Over Half a Million Years.’ I have been working with Byron Wolfe (photographer), Troy Jollimore (philosopher/poet), Sheri Simons (sculptor), Rachel Teasdale (volcanologist), and Oliver Hutton (graphic designer) for the last five years, creating art, essays, and poetry around these questions, these little discoveries of things that are gone. The project began as a look at four iconic disappearances in Northern California—the Wooly Mammoth; Ishi, the last of the Yahi Indians; the Hooker Oak Tree (once reputed to be the largest tree in the world); and Mt. Tehama. But for me, the project took on an incredible life beyond these four, as it seemed that all things disappeared must somehow know each other and be speaking to each other, that Amelia Earhart and Ishi and even the mammoth were trapped somewhere beneath us or in some kind of invisible ether, in some life we cannot see or understand. Thinking for so long about things that vanished made me really curious about sound, because once sound disappears, where does it go? So part of Helpless Intruders is an attempt to understand the evolution of how we think about sound, and how we listen, especially to things we can no longer hear.”

Heather Altfeld

Iron Horse Literary Review would like to thank its supporters, without whose generous help we could not publish Iron Horse successfully. In particular, we would like to thank our benefactors and equestrian donors. If you would like to join our network of friends, please contact us at ihlr.mail@gmail.com for information on the various levels of support. Benefactors ($300) Wendell Aycock Lon and Carol Baugh Beverly and George Cox Sam Dragga Madonne Miner Charles and Patricia Patterson Gordon Weaver Equestrian ($3,000 and above) TTU English Department, Chair Brian Still TTU College of Arts & Sciences, Dean Brent Lindquist TTU Graduate School, Dean Mark Sheridan TTU Provost’s Office, Provost Rob Stewart TTU President’s Office, President Lawrence Schovanec