F-I-N-E

LESLIE PIETRZYK

F-I-N-E LESLIE PIETRZYK

The Long Story 2024

Cover Vector Art: Igogosh

Cover Design: Leslie Jill Patterson

Associate Editors:

Editor-in-Chief

Leslie Jill Patterson

Fiction Editor

Marcus Burke

Nonfiction Editor

Elena Passarello

Managing Editors

Emma Aylor

Jennessa Hester

Joshua Luckenbach

Bibiana Ossai

TIMILEHIN ALAKE, NANA BOATENG, CALEB BRAUN, WILLIAM BROWN, COLLIN CALLAHAN, JACKIE CHICALESE, WILL DENNIS, WILL DURHAM, JO ANNA GAONA, MEGHAN GILES, VICTORIA HUDSON, AMELIE LANGLAND, MARCOS DAMIÁN LEÓN, NIKKI LYSSY, KAMRYN PITCHER, DUSTI K. SMITH, GRAYSON TREAT, AND BRIA WINFREE

Copyright © 2024 Iron Horse Literary Review. All rights reserved. Iron Horse Literary Review is a national journal of fiction, poetry, and creative nonfiction. IHLR publishes three print issues and three electronic issues per year, at Texas Tech University, through the support of the TTU President’s Office, Provost’s Office, Graduate College, College of Arts & Sciences, and English Department. For more information, visit www.ironhorsereview.com.

F-I-N-E

They only know me as mo-om, as mo-ther-oh-puh-lease; or the little ones still chirping maaaah-mmy. I’ve never been anyone else to these children, won’t be. My tombstone will spell M-O-M, carved large. But tonight, here I am, like someone who is—I don’t know what—maybe a dramatic movie star or a woman in a cold cream commercial, staring into a dark bathroom mirror after waking up to pee. It’s the strangest thing. I don’t know who or what I really am, who or what I used to be or might have been instead. I’m a void. I’m a little green Martian or a woman from an imagined land, a TV place like Mayberry or Oz. I’m not someone who thinks about things, but here I am, thinking. I love my perfect children, my five girls—Kim, Suzanne, Tracy, Kelly, Jenny— I really do, and so, really, does J.P., my husband and their father. Nineteen years married and he’s the only man I’ve loved, a good man trying his best to be a better man. There’s no boy in our family, but whose law says there must be a boy? Can I wonder, right now, in this darkness, what’s so great about boys?

Aren’t there more than enough moments to look at the world and think: not one thing is great about boys and men. They get us in trouble and make messes someone else cleans up. I should be ashamed to think such things, and I am. Jesus was a man and God is—not a man, but a capital H He. Things are as they are because everything started with Him creating the world just the way He wanted, reining in the wilderness, taming Adam’s and Eve’s raging hearts until they—until she—no capital S—messed it up. If He didn’t want the snake, why did He put it there? I know we shouldn’t think that, but it’s hard not to, right? Here in the dark? Alone?

Oh, yes, you bet: everything’s been set up exactly for His pleasure.

This mirror, this darkness. Four AM, me and the cats awake. Here’s that rare moment when a mom gets space to think things she shouldn’t. Like, wouldn’t it be pleasant if Paul Newman took off his shirt more often? I flip the light switch and squint until my eyes ease; then I stare straight into that mirror.

I’m someone with a secret.

I’m someone with a baby growing inside me.

I’m someone hearing that snake’s whisper. Nights like this drenched with silence, two cats peering wide-eyed and hungry, eager for the can opener and early breakfast. J.P. out late, skipping dinner, for the third night in a row, or fourth. Wait long enough and this decision is made without you. That snake’s insistent hiss: Fix. This. Fixxxx. Thissss.

The right time to tell my husband J.P . is after the hopefulness of Thursday’s family night dinner. Attendance mandatory. Yes, Kim, mandatory for you, my cagey, secretive showboat of a teenager, lost in a solar system of friends. Yes, J.P., you too can spare an hour to eat food I’ve cooked and listen to the chatter of your children. “For our family,” I explain. His favorite meal—T-bones and fried potatoes—will draw suspicion in a way meatloaf and baked potatoes won’t. Open a fresh bottle of Wish-Bone Italian for the salad. Turn the potatoes special with sour cream and Bac-Os. Apple crisp and Cool Whip for dessert. Finesse and luck are required. I have to catch him before his car keys jingle, before he’s out the door to meet “the guys”; tuck this afternoon’s Press-Citizen deep in the garbage, covered with coffee grounds; hope and pray it’s a night the kids control the TV with shows that bore him.

And my hugest hope and prayer: that he agrees with my decision, that he listens to my plan. I’ll handle the details, I’ll assure him, and no one will find out. I’ll even cook dinner that night; nothing changes. I always find a way, don’t I? I’ll say, whether it’s teaching Suzanne fractions so she finally gets them or clipping coupons and working sales to save twenty dollars at Hy-Vee. We don’t have to talk about risks or the church or “against the law.” I also don’t have to tell him my instinct screamed, Do it and don’t tell him, because here I am, telling him— instead of silently taking care of everything by myself, like usual (definitely don’t say that).

I won’t imagine we’ll resolve this in one night, in one conversation, and I won’t let on it’s already resolved one hundred or ninety-five or ninety percent in my mind. I won’t make him feel bad that I worry about money and paying for one more wedding or college and how we need a new station wagon and that everyone’s growing out of snow boots and and and—because we know he works hard and it’s not his fault his boss hates him. I won’t mention his late and later nights because he’s right: he’s allowed the freedom to have friends, to have some fun, and buying a drink or two is no sin, not a Ten-Commandments sin anyway, and I won’t wonder if other things he’s doing on these nights are Ten-Commandment

sins, and I definitely won’t say that because what I propose doing to my body, to this body inside me, is.

I won’t catch him looking at the clock, and I won’t imagine him thinking about beer. I won’t ask for the money I’ll need, because he doesn’t know about the secret stash my mother told me always to sock away under my pantyhose. I won’t give him any choice while making him believe he’s choosing.

I won’t cry. He hates that.

I won’t say blessing or baby or your son. Unexpected situation is what I’ll admit to.

And I know him. He won’t say those words either. Every choice here is impossible, and a choice can be impossible yet still the right one. Let him see how that feels.

Of course, I won’t say that to him either. All he’ll hear is, I’ll handle this unexpected situation.

At dinner, everyone shares something that made them happy today. Mine is my beloved family eating together at the table with the TV off, everyone home, everyone healthy. Kim got a B+ on a pop quiz about The Scarlet Letter; Suzanne and Tracy both liked the cafeteria pizza at lunch; the two little ones are happy about playing with the neighbor’s kittens. J.P . says, “Happy news? Not much of that around these days, with this damn election and—”

“Daddy swore! No swearing,” the little ones chant.

“Just one tiny little happy thing,” I say.

“I’m extremely happy I’m not the cow who got turned into this meatloaf,” he says.

The girls groan and squeal, and Kim says, “I’m telling Mom constantly we should go vegetarian.” She shares dramatic facts about baby cows and lambs, and she’s so graphic I’m sure animal-loving Tracy and the little ones will start sobbing and derail my plan, but thankfully I distract everyone with apple crisp.

I won’t tell him I’m bothered he can’t find one thing about us that makes him happy.

Thursday night means The Waltons, which means the kids control the TV for at least an hour. Talking about something serious while they’re awake may not be what Dear Abby recommends, but she doesn’t know my husband. She doesn’t see his itchy glances at the clock, that casual sidle to the bedroom to grab his keys before hurrying down the hallway, his dismissive shout, “Back later,” like that’s a complete sentence. She doesn’t hear the car grinding alive, screeching like a pent-up monster as it leaves the driveway, doesn’t see the kids pretending to ignore it all.

Starting this talk now in the kitchen, while the TV’s blathering, will make words move quickly, without yelling and crying. Information will be presented, decisions made.

He’s suspicious when I call him over. “I’m looking for the newspaper,” he says.

“I have to tell you something,” I say.

He looms in the doorway, arms extended between the two sides of the door. He wears his jacket from his day at the bank, which is how I know he’s planning

to go out. He likes showing up at the Robin Hood Room—a cocktail lounge at the mall—looking like a million bucks, which is what he used to say to me: “You look like a million bucks, Mary-Margaret.” I sure did, back then. Dressed up or naked. “Stop,” I’d say: shy protest, hair toss. Then one day he did stop. (I won’t bring this up.)

He says, “You’re getting on me about going out tonight? Because I don’t want to hear it. I was at dinner like you said.”

I smile. “Let’s sit at the table,” I say, which I’ve just wiped down. The dishes soak in the sink; I excused Suzanne and Tracy from doing them. “Why not?” Tracy asked. “A treat,” I told her. (I won’t mention I’m killing her sibling.)

He goes to the head of the table, his usual spot. I sit to his left, Kim’s chair. He drums his fingers on the table. There’s his wedding ring, and I resist the urge to thank him, though I wear mine without thanks.

Suddenly: what can I bear hearing out loud, in actual words?

“Is everything okay?” he asks. “Something wrong with one of the kids?”

I suck in breath but forget to let it out. Something uncomfortable feels stuck; my mouth opens and closes, and I’m as clammy as a dead fish. His fingers go motionless. Air finally gusts free. “I’m sorry,” I say. “Kids are fine. But I found out something. I thought I could just say it.” There’s no air anywhere right now. From the living room, a commercial plays, the kids all shouting, “Please don’t squeeze the Charmin,” and I wrap my arms around myself because I’m the worst mother on Earth. All I want is for him to talk me out of it.

“Oh my God,” he says. “How’d you find out?”

This next moment lasts almost forever.

“Who told you?” he asks. “It’s a misunderstanding, swear to God. Whatever they said, they were wrong. You can’t listen to bullshit.” His voice is quiet but insistent, words tumbling like they’ve rolled over in his mind, polished to perfection—like the rock tumbler Santa brought Suzanne and Tracy last year.

A relief to know what to say: “Language,” I scold. “Don’t swear.”

He says, “It was one time. You have to believe me.”

I watch his mouth move as he talks. Watch him twist his wedding ring. Watch him talk and talk. When my brain catches up to his words, he’s saying, “Maybe this is for the best. I’ve been in torment, feeling like such a heel.” He lifts my hand. His hand’s warm, but mine doesn’t seem connected to my body. “You’re who I love,” he says. “You and the girls.”

I can’t feel my fingers. “What are you saying?”

“That I love you,” he says. “Please forgive me. For the kids. For the family.”

Can’t feel my hand, my arm, my chest. My head’s Easter-Bunny hollow. It shouldn’t be possible to know something yet be surprised when the words are spoken.

“If you knew how sorry I am,” he says. “It meant nothing to me.”

It meant nothing to him. Yet there’s a week of talking. Rather, him talking. To save time, I cut to the end and forgive him. I won’t, I remind myself, mention that maybe other people have secrets too—and know how to keep them.

After it’s over, I still need a phone number. Finding that should be easier than it is. But remember the Garden of Eden. Nothing He gives Eve is easy.

In the middle of all this is still the world going on. Tracy, my middle girl, my sweetie, the dreamy, drifty one I’d worry about if I had time, is in her first year of middle school, hating it. “They’re making me take woodshop,” she wailed when she came home back on that first day. “Like I’m a dumb boy.” That didn’t sound right because Tracy’s easily muddled, getting things topsy-turvy and inside out, this daughter who needs two sharp eyes always on her. I’m sure the school knows its business better than I possibly could, but she was so upset I promised to call over and straighten out her schedule. When I did, the surprise was discovering she was right: the whole seventh grade—girls and boys—now take woodshop. Required. In eighth grade, it’s Home Ec—cooking and sewing— for girls and boys. Required. I must have sounded astonished, or maybe mine wasn’t the first phone call, because the secretary said, “Boys eat too. Knowing how to fry an egg won’t hurt them.”

I thought of my Tracy grabbing saws and drills. Honestly, she shouldn’t be frying eggs in a hot pan just yet. But I thanked the secretary and hung up, figuring the school made up its mind.

Now, four weeks in, parents can’t stop fussing, everybody suddenly with something to say. The rumor is that a girl went to the nurse for a tourniquet and got taped up with rolls of gauze. Tracy tells me she’s supposed to make a lamp. Required. “The shop teacher hates us,” she whines. “The boys get to make fancy birdhouses for purple martins, with three floors and a roof, and girls are making dumb lamps. It’s unfair. He likes boys better for no reason. One girl, a cheerleader, called him a male chauvinist pig and got six detentions. When she cried, he gave her two more, and one for her friend who hugged her. What if I’m next?”

It’s not a good day, this day I find all this out, because of other things I’m finding out, and really, can I just please hug my Tracy and cry right along with her? I was terrified of detentions, too, afraid of mean teachers. What I could tell her, but probably won’t, is that all along the way, wherever she is, at a doctor’s office or bank or school—anywhere she can think of, anywhere she’ll be—boys are the favorite, and a girl just has to know this. Something we live with, I could say.

Without, maybe, ever truly getting used to it, I could add.

The Saturday after that—time moving so fast I’m certain the clock’s hands sweep away entire calendar days, not mere minutes, and me still pretending I can wait another week—I’m in the kitchen, like usual, though I don’t feel usual. I’m immersed in dumping lunch’s uneaten bread crusts and orange rinds into the garbage under the sink. Something smells—sour milk? dead mouse?—and suddenly what I’m thinking about is focusing my entire everything on pushing back waves of bitter bile surging straight up my throat. Kids don’t like moms throwing up.

“Mo-om, phone for you,” Tracy calls as she drifts into the kitchen, silent on bare feet though it’s October. (My floors are clean.) “Didn’t you hear me?” She’s at the fridge, opening it without purpose, that way she has. Think! anyone would want to scream at a girl like that. Suzanne, older by one year, comes up behind Tracy, and together they stare into the lit shelves. My visceral sense of annoyance and anger—swallow that, too.

“I’ll go to the store later,” I apologize. In my head is a vision of lying in bed and sleeping away the rest of today and tomorrow and forever.

“I said, Holly’s mom’s on the phone, waiting,” Tracy says.

“Tracy told her you were here, so you have to answer,” Suzanne adds.

“You said to never tell a lie,” Tracy says. “Thou shalt not bear false witness against thy neighbor. Number nine.”

“Glad someone’s paying attention in catechism.” I force a brittle smile. “There’s no need to lie. I’m delighted to talk to—” I pause, “—Holly’s mom.” Anyone else, I’d say Mrs. whoever, but Holly’s mom—Carly—isn’t Mrs. or Miss. “To Ms. Patterson,” I say with fake confidence. These two are mesmerized by the interior of the refrigerator, not listening. I gulp down more annoying sickness and fixate on the kitchen ceiling—stare, stare, stare. That crack isn’t new, though J.P . doesn’t want to hear about it again. Finally, I’m fine. “Lying’s a sin,” I announce, “like not honoring thy mother,” and it’s off to the living room, where I grab the phone receiver Tracy left on the table next to the sofa.

I sit, then—why not?—lie down. You know how sometimes you can fall asleep in four seconds? I pull in a big breath before pushing out perky: “Hi, Carly.”

LESLIE PIETRZYK

“You’ve heard what they’re doing, right?” Carly’s fury barrels at me along a piece of string stretched a thousand miles. Whatever she’s angry about, I know I’m not going to care as much as she does, not with my vastness of problems.

Carly’s younger than I am, fresher. Shinier hair, skin that glows versus skin scraped by sandpaper. Polished fingernails instead of my bitten-down nubs. I’m a comfy stuffed cat with a chewed ear that five kids have drooled on, and she’s Malibu Barbie in a dune buggy. It does no good to pretend she’s not pretty, because she is, but it’s a bristly kind of pretty, like it’s smart to approach cautiously. Some neighbors whisper and steer clear because she’s a cocktail waitress at the Robin Hood Room. Not my business. She and her daughter came here from Chicago last December—to visit, we thought, but it turned out to move into her father’s house two doors down. Her schedule’s askew—late shifts, sleep till noon—and we moms don’t see much of her, though maybe the kids play together, or did.

“Mo-om,” Suzanne shouts. “I’m hungry.”

I shield the bottom of the receiver with my palm and shout: “I’m on the phone.”

“These people,” Carly says, and because I think she means my kids or all kids, I agree, but discover I’m wrong. “I mean,” Carly adds, “don’t you love girls being in woodshop? Let them be union carpenters making good money. And boys cooking. These are strides forward, not something for nasty petitions.”

I say, “Jesus was a carpenter.” I’m an idiot. I’m always an idiot around someone with strong opinions. Still, the safe image of blue-eyed, suffering Jesus soothes me. I’d trade problems with many people right now, but not Jesus.

“I bet your daughter’s thrilled to be taking shop.” Carly’s words sound angular, not quite fitting into my ears. “That’s why I’m calling: your girl’s affected. I wish Holly wasn’t a year older, stuck in Home Ec.”

“I don’t know,” I say. “Tracy has to make a lamp.”

“Exactly!” Carly says. “That’s what I mean.”

“What?” I say. I hear kitchen cupboards opening and closing. Honestly, I fed everyone lunch an hour ago. Or were those yesterday’s bread crusts I cleaned

up? I notice I have no idea what time it is. Though it’s definitely Saturday because last night J.P . made a big deal about being home on Friday, playing Clue with the kids.

“So, I can count on you at Monday’s PTA meeting?” Her voice is a drill, spinning, whining, relentless. Easy to imagine her pushing drinks on people, on men, on my husband, night after night: One more? How about one more? and J.P . saying, Yes, yes, sure, yes. Yes to it all.

I don’t like Carly.

Still: “Yes,” I say, which happily means this call’s over. Easy. Maybe I shouldn’t blame J.P . for saying the word.

PIETRZYK

Carly drives me to the PTA meeting. “I insist,” she insisted when she made the offer. Now, she says, “I’m losing a shift for this. That’s how important speaking up is. That’s what I want my kid to understand. Sacrifice. The fight’s for others, not only ourselves.”

I don’t need to say much in the car because she’s a lava flow of conviction, because she trusts I share every angle of every view she spouts. I’m not not on her side. Maybe Tracy can build a birdhouse that’s as good as any boy’s. I nod, nod, nod. Each nod reminds me of this ticking clock I’ve got going. Carly’s a bomb two ticks from explosion.

The parking lot’s three-quarters full. I’ve been to PTA meetings at the elementary school, where the same handful of people complain about the same handful of things: some teacher everyone wants fired, some teacher they want to give an award to, the upcoming bake sale. I’m always stuck on the bake sale committee, volunteered for Scotcheroos in baggies, two for a quarter.

The lighting in the school auditorium is harsh, as if its purpose is to expose all of us attending, to allow everyone present a clear view of our deepest interiors, down to the bone, down all the way to the guts of every secret we carry.

Carly insists on first-row seats—“so those old ladies who think they run everything see who they’re up against.” When we walk in, she beelines to the sign-up sheet for speakers and writes her name, then mine, without asking. I’m expected to speak for three minutes. And say what? All Carly’s fire, and still her daughter, Holly, is abrasive and lonely and too smart for her own good. When they moved here, instantly Carly got her daughter bumped up a grade. “These schools,” she said. “Come on.” Fast and decisive. I should admire that.

I’m in a Sunday church dress, freshly ironed, and Carly looks like she rooted through the closet of my oldest, Kim. It’s the PTA, and Carly’s wearing patched jeans, a gauzy blouse, heavy black boots with laces up to her knees, and an armload of bracelets that tinkle and click as she talks and talks until the gavel bangs us into order and the meeting begins. I’m probably not even ten years older than she is, but there’s a century between us, or at least a lifetime. Impossible to

imagine what she cooks for dinner for her daughter and her father: Curry? Wontons? Snails? I brought a neighborly tuna casserole over early on and never got my CorningWare back or a thank you. Who’s too fancy for potato chip topping?

I asked Tracy and Suzanne about Holly, and they said, “She’s fine,” and Tracy said, “I worry about her, but secretly. She’d hate knowing someone worried about her.” I asked why, and Suzanne said, “Duh—there’s no dad.” I know this—but it’s easy to forget because Carly’s so consuming, as if all that energy and feeling make her mother and father, grandparents and aunt.

Old business. No one cares. We’re here to express our opinion on why girls should or shouldn’t take shop and why boys should or shouldn’t take home economics, and the meeting quickly whisks us there, to new business.

Sherry Calhoun, PTA president, waves the clipboard holding the sign-up sheet and warns us to be respectful and orderly; she explains they’ll listen to testimony and make an official recommendation to the school board. Sherry’s voice is deep and slow: an obsolete foghorn. She reminds me of every bitter, secretly enraged nun who ran a class in Catholic school. I don’t know who her kids are, but I don’t imagine her relinquishing her kitchen to boys baking cakes for homework. The principal sits next to her, his face and body clenched.

The room’s divided: for the change, against, against, for, for, against. Might be quicker to line us up against two walls, those in favor on one side, those opposed opposite. “It’s against nature for boys to bake cookies,” a man in a flannel shirt says. Another man tugs his striped necktie and wonders, “Who’s going to marry my daughter after she chops off her fingers in shop class?” A bake sale buddy pleads for equality: “Women can do anything men can, usually better,” she says. “Give us the chance to show you.” Carly and some others applaud, ignoring Sherry Calhoun’s repeated threats against outbursts and the eager thump of her gavel. Some people like power a little too much, if you ask me.

My head aches; the room compresses. Time ticking in three-minute increments creates an eternity. Decide! Words ricochet through my head.

LESLIE PIETRZYK

If I have another baby. Diapers, bottles, potty training, PTA meetings, and a million more Scotcheroos in baggies. My stomach roils. I can’t remember when I ate. Surely I made dinner?

If I don’t? I want the decision to be simple, but if it is, I’m terrified. What beckons is sweet emptiness, a problem resolved. What beckons is a truth I’ll never speak: I love my five (five!) children, but not this one, and maybe not its father. Am I punishing a child for what’s my fault?

The flames of Hell catch me, and I sweat into my dress.

Carly’s name gets called—the Ms. stretching into a string of zzzzz—and she jumps up, brushing both palms along her thighs. Her footsteps to the podium are quick, clipped, and efficient, a woman who balances trays of drinks filled to the brim.

I’ve worked out the math—we all have—and she would’ve had Holly when she was seventeen. Prom-night baby is the rumor. I don’t usually listen to things like that unless there’s that grain of truth. I imagine Carly’s mom advising, “Every baby’s a blessing,” then warning, “No way I’m letting some back-alley butcher near my daughter.” All the pat words and angles I rehearse in my head when Kim talks about boyfriends.

Carly’s at the podium, gazing at us as her three minutes tick. Some men who spoke had notes on paper. Many women started, “My husband and I. . . .” Every person up there picked a side, like they’d been promised by someone that life was always straightforward. She says, “I know you all know I don’t have a husband and that I’m a cocktail waitress.” Tittering behind me. “I’m not ashamed of what I do to put food on the table, but I’ll tell you, it’s a hard life. Maybe you don’t know, or maybe you do. What I want most is for girls today to have chances to make something of themselves, to get jobs that pay well and don’t give them varicose veins, to truly be equal to men. Honestly, I want my daughter to be more than someone’s wife and someone’s mom.”

Oh, no one likes that. A couple of hisses, a boo, then shouting: “What’s wrong with being a mom?” and “Man-hater.”

The gavel bangs. Sherry Calhoun says, “That’s three minutes.”

Carly’s mouth hangs open. “No way that’s three minutes.”

“Next,” Sherry says, and there’s my good wife and good mother name thundering into the auditorium, granted space because I carefully waited for marriage, I dutifully drive my five girls to mass on Sundays, I lovingly forgave my husband for drinking all over town and more—and because I’m keeping my secret.

“Mrs. J.P . Riley,” Sherry Calhoun booms again.

That barely sounds like me.

Carly’s still up there, and she shouts into the squealing microphone, “You people are horrible.” Immediate boos, some applause, and more shouting.

Another threatening gavel bang, like next time your head’s getting cracked.

My stomach twists and bends, and hellfire’s sweat drenches me. No one knows my plan to murder an innocent baby. I’ve been so, so careful every last minute of my entire life, following every terrible, shifting rule that came at me.

“Give her my spot,” I call. I scramble out of my seat, up the aisle, hurrying to the auditorium lobby, where there’s got to be a ladies’ room. Sounds like everyone’s booing me along the way.

The bathroom’s too far, so I grab onto the edge of an empty folding table (probably from some bake sale) and lean over to hide my face and vomit everything onto the floor, barely missing my shoes. Frozen corn for dinner, I think. Sloppy Joes. I can’t even be sick without being shown I’m someone’s mother. The smell is wretched, and I breathe it in anyway because I did this to myself.

“Are you okay?” It’s Carly, one hand touching my back, the other reaching for my forehead. “You’re warm.”

“Just the flu,” I say. “All I need is paper towels.”

“You were fine earlier.”

“You should be speaking right now, giving them heck,” I say.

“Those Neanderthals,” she says. “Let’s get you home.”

“The paper towels,” I say.

She says, “Someone else can do that. You don’t have to clean up every mess, do you?”

I cover my face with both hands, so she won’t see me. My body shakes. I can’t breathe. I stink. I’m an embarrassment in every possible way. I wait for her to say so. When she doesn’t, I say it myself: “I’m so embarrassed. I’m sorry.”

“I work in a bar, remember?” she says. “The stories I could tell.” She laughs. Not me. She’s my neighbor, I remind myself, my little-bit-crazy neighbor spilling her big opinions everywhere, my neighbor who wears a ye olde England miniskirt and serves beer to and knows embarrassing stories about my embarrassing husband.

I’m not like this. I let my hands fall away from my face, straighten up, find a spot across the room to stare at. Giving up starts here. I say, “I’m pregnant.”

I brace for it: squeals, clapping, and promises of a shower with the neighborhood ladies. I wait for her to remind me every baby’s a blessing as she stumbles out reassurances that six kids is a round half dozen and that she’ll pray we get the boy we want. She’ll guide me to a chair, saying, “Think of the baby,” cracking jokes about eating for two. In the end, the impossible choice is impossible for me. I guess I’ll probably learn to love this baby and that man.

Carly says, “What are you thinking?” Her face has zero expression, seems willing to move in any direction.

The moment is fragile. How do you learn love?

I ask, “Do you maybe . . . know someone?”

Nobody’s world collapses upon me as she nods, as she whispers, “Yes,” as she scribbles a phone number on a deposit slip torn out of her checkbook that I silently slide into the zippered pocket of my purse. She tells me she’ll drive me, she’ll take care of me, everything will be fine.

The PTA meeting probably rages on, but Carly’s car is quiet, and the shadowy, empty streets are restful. I’m sorry when we pull into her driveway, but she says, “Let’s sit out back. They think we’re at the meeting, so here’s twenty minutes of freedom.”

She leads me around the side of the house to the brick patio and a couple of folding chairs. The patio light is low-watt yellow, with a bulb that repels bugs. There’s an afghan on one chair, which she hands me as she drags the chairs outside the yellow light. The blanket smells musty, but I politely drape it over my lap. “I smoke out here,” she says. “Ever the naughty teenager.” She sits, stretching her legs, flexing her booted feet. “If we lose on shop class, we’ll win on something else, something bigger. Things can’t go on like this.”

The blanket’s chilled with night air. My grandmother crocheted similar blankets, but I never learned how. Looking left, there’s my own backyard, with its rusty jungle gym and tattered vegetable garden. Here, straight ahead, is a large oak, its trunk wide enough to be hundreds of years old.

“They’ll blindfold you,” Carly says. “Take you somewhere for the procedure. An apartment or a motel room. I can’t go, but I’ll wait and bring you home. It might be a little rough right after, just so you know. Cramps. I mean, you won’t have to make beds or vacuum, right? You can have a headache or something? Be left alone?”

Five children, I think, but I say, “There’s dinner.”

“I’ll bring it,” she says. “Macaroni and cheese. Salad.”

“They only eat Italian dressing,” I say.

Carly’s voice tightens. “So I’ll buy Italian dressing. Wish-Bone? Or Kraft?”

I think she thinks she’s joking, but I whisper, “Wish-Bone.” How’d my head get jammed with stupid knowledge?

She says, “I hate that—” She stops, lights a cigarette, snapping the lighter into flares several times. Finally, she says, “Never mind.”

I crunch my fingers through the crocheted holes of the blanket, clench my fists. “I’m not telling him. He doesn’t believe in . . . it.”

She sucks hard at her cigarette, blows out three symmetrical smoke rings, says, “I learned that in high school. Practiced secretly for weeks, then popped one out for my boyfriend, like magic. He bought it. Idiot. Men don’t have to know everything, right?”

This darkness is a comfortable cloak, and now is when to say anything. “You know him, right?” I ask. “J.P . My husband.”

“I think,” she says. “He’s around the bar now and then, maybe?”

“Actually, I know you know him,” I say. “He’s there all the time.”

“It’s a friendly place,” she says. “Guys shooting the breeze. You know. Like us right now. That’s all.”

I stare at the crooked oak branches. All that remains are questions with impossible answers.

Carly blows another smoke ring. “My tips get better when I do this,” she says. “Or tie cherry stems into knots with my tongue. Isn’t that crazy? The things we’re rewarded for?”

“Crazy,” I agree.

Carly shifts, the chair scraping brick. “People’s voices sound different in the dark. Is that scientific? I remember in high school asking the biology teacher if he thought. . . .” On she goes, like she’s been waiting ages for an audience. Time ticks away.

I interrupt: “Are you helping me because you . . . um, had your daughter . . . early?”

She drops her cigarette onto the patio and leans forward to crush it with her boot, twisting hard. “People still talk about that?” she says.

My cheeks heat with embarrassment. “I just mean,” I say. “You barely know me.”

“There was this girl at City High,” she says. “A year older, but we were in the same group. The whole school talked about her being knocked up without once talking to her. People were nasty. One day she was gone. The rumor was, she went somewhere to have the baby. Only she never came back.”

LESLIE PIETRZYK

“Maybe she—”

“That next year, I couldn’t stand not knowing, so I drove to her parents’ house. The curtains were closed, and mail crammed the box, but I rang the bell and pounded the door till her little brother opened it. Oh god. One of those pale, runty kids with hair practically as white as his skin, those kids people forget need attention. I asked was his sister dead, and he pushed the door, but I shoved in my foot and then both arms, and I wrestled inside like I was Superman, and he ran upstairs, shouting, ‘Mom!’ I stood there, breathing a mile a minute, and I remember how the family photos in the living room, on the walls and the fireplace mantel, all had black Magic Marker blotches where my friend’s face should be. I got out fast.”

“Maybe she was okay,” I say. “Maybe—”

“Her ghost haunts the school, roaming the hallway, mostly early mornings, carrying her bloody baby. The janitor saw her, football players in at six for twoa-days, wrestlers pumping iron to make weight. I caught her slipping through the third-floor bathroom’s closed door, and when I followed, a toilet flushed with no one there. And no yearbook picture. Not even that. They made her disappear. That’s why I’m helping you. I promise the number I gave you is safe. Not some creep.”

The next question feels obvious. I won’t ask it. I don’t have to know.

She answers anyway: “A few weeks ago. Don’t tell anyone. I’d be fired for being pregnant, but also they’d probably fire me if they knew I had an abortion. Isn’t that funny?”

Neither of us laughs.

“I’m sorry,” I say.

“No, it was a relief,” she says. “Honestly, nothing about it meant anything to me. Not the man or the group of cells invading my body. I’m fine. F-I-N-E. You will be too.”

It’s easiest to believe her. Still, I reach out and rest one hand on her arm, as if she’s a child. She sighs gently, lets me do this, but—I suspect—no more.

“Don’t tell my daughter,” she says.

“Never,” I say. All I can offer as comfort is this lie: “My girls really like Holly.”

“Good,” she says. “Holly’s sensitive, has a tough time making real friends. I worry about her.”

“I worry about mine,” I say. “Can’t help it, right?”

She moves away from my hand to light up again, and oddly the night feels blacker with the red tip of her cigarette slipping through it. Time feels absent as we sit in silence. I don’t think I’m thinking anything, but I must be until something shifts.

Carly says, “Sometimes I’m so mad about everything. Aren’t you so mad?”

She can’t see me in this dark, so I lie again: “Sure.” Anger’s a luxury I leave for others.

“I’m mad all the time, at everything,” she continues. “What kind of world are we leaving for our girls? Do you ever think about that?”

Doesn’t matter what I think. Look at the PTA, who knew from the start what they’d listen to, and whom. “I said I was mad,” I say.

“Damn right,” she says. “You should be. Your husband—” Her cigarette moves to her lips, pauses there. “What do you know?”

She’s heaved that rock. Nothing’s comfortable now. My body’s tight, the jar lid no one can budge. My house is two doors down. I can walk away. I speak carefully: “I forgive him for all that nonsense.”

She sighs. “Remember my friend, the one who died? Or whatever? Whose parents disowned her? Whenever I tell that story, no one asks what happened to the guy.”

“Because everyone knows,” I say. “Nothing.”

“He ended up marrying the girl’s best friend. They own the Dairy Queen on Muscatine Avenue.”

“Where kids get free dipped cones on their birthday.”

“That’s one reason of a million why I’m absolutely, constantly furious,” she says.

What we’re talking about has nothing to do with shop class or her friend or Dairy Queen or how voices sound in the dark or even unexpected situations. I say, “I should go.”

“Stay,” she says. “Didn’t you ever once in your life burn so mad you had to do something, even knowing it’s something crazy? That’s the why of my entire life: why I went to the meeting tonight, why I stormed into that girl’s house, why I’m always getting myself into trouble, why I wouldn’t let anyone steal my baby who was supposed to love me after my mother died. Why I run off again and again. Why I can’t shut up when I should.” She jumps up, her dim figure seeming to double in size. “Come on,” she says. “Let’s TP the whole neighborhood.”

“What? Why?”

“You know, toss rolls of toilet paper over tree branches,” she says. “Like olden days. Have fun sneaking around, doing something no one expects. I did it all the time growing up around here. Didn’t you?”

“But we’re moms now,” I say.

“I can’t just sit here going crazy,” she says. “Maybe you can.” She grabs my hand, tugs me out of the folding chair. The blanket drops to the ground. “Come on.”

I yank away my hand and bend to pick up the blanket, now warm with my body heat. I fold it, flop it on the chair. I think of what I say to my daughter Kim: If everyone else jumps off a bridge, would you? And what Kim snaps back: You bet I would. How much have I missed by being who I am? Tears press, though I don’t want to cry.

Carly says, “I know there’s something making you mad. Like—well, you know.”

“You were going to say, ‘like your husband,’” I say.

“Mary-Margaret,” she says. “You know I’m so sorry.”

I smile nervously. “Please stop,” I say. “He’s not a bad man.”

Immediately she says, “I’m going inside for toilet paper. Be right back.”

The night tightens with her gone. Tossing around toilet paper will prove nothing, will be a mess to clean up. I got what I wanted: that number hidden in my

LESLIE PIETRZYK

purse. Now, I’ll walk home, tiptoe through the front door, check that the little kids are asleep, check that Tracy and Suzanne are reading in their bunk bed or doing homework. I’ll wonder where Kim has got to, but I won’t worry. I’ll feed the cats because no one remembered to, put away the pots drying on the rack, wipe down—

I grab the blanket, shake it out and refold it, trying to match its edges evenly in the dark. What’s so great about being angry? I sling my purse over my shoulder. I could leave right now.

The glass door behind me slides open, and I half expect Carly’s father barging out, yelling, but it’s Carly, laughing, her arms juggling columns of toilet paper. “Oh, great,” she says. “You’re still here. Every roll in the house. Someone will have to get more from Hy-Vee tomorrow, but so what?” Her voice sounds lighter, the way it did earlier when we were revving up to take on the PTA. I try to imagine her waiting, or hoping, or praying, or running long conversations about God in her head. I can’t even imagine her feeding a cat, which seems so unfair, right, that here we both are anyway.

“Who was it?” I ask.

“Who was what?”

I can tell she thinks she knows what I mean. But which who, exactly, do I mean?

“Don’t do this,” she says.

“You know something about my husband, so say it,” I say. “He swore it meant nothing to him. I forgave him.”

She laughs, a harsh bark. “Just go home.”

I’m still holding the blanket, so I set it on the chair. Then I kick at the chair, sliding it askew. Immediately I shove it, knocking it into the other chair, and I push both all the way over in a big clattery commotion, but quickly set them right again, draping the blanket on top.

“You’re so sad,” she says. “I hate all of this for you.”

I say, “You’re the one with no husband.”

She says, “He’s the one who got me the phone number.”

I don’t breathe. I’m fine, I think, fine. Fine, fine.

Carly says, “And a hundred bucks.”

I’m fine, fine, fine, fine. “I’m fine,” I say. I sound foolish. I am foolish.

“For me,” she says.

“I get it,” I snap.

“If it helps, I feel awful about everything and having this secret.”

“You’re helping me because you feel guilty,” I say.

“Both of us,” she says. “Just look. It’s like we’re forever dumb seventeen-yearolds desperate for some worthless man to love us.”

I grab at the rolls of toilet paper she’s holding, jostling four into my arms, and run toward the oak tree. I heave a roll high, but of course not high enough. That tree’s huge. The roll unspools flat along the expanse of grass and fallen brown leaves. An exact picture of the uselessness of anger.

“Honestly, I’m sorry,” she calls.

I run across the Johnsons’ backyard in my nice church shoes, cutting to my own yard, with its rusty jungle gym and crummy crabgrass with the dried-up circle where the cheap, inflatable wading pool sat all summer. The family with too many kids—that’s how people think of us—the family where the dad can’t just stop, where the mom’s always making another baby, like the one thinking it’s safely settled into my body right now.

I circle to the front of the house, where the porch light’s burning because I’m careful to turn it on when J.P. or anyone’s out at night. This toilet paper I’m clutching feels softly luxurious, a better brand than my usual. “Please don’t squeeze the Charmin,” that annoying Mr. Whipple bosses the poor housewife in the commercial.

I detour to the two bushy crabapple trees we planted a few years ago, wanting clouds of pink flowers every spring. Mostly it’s cursing about the endless sour crabapples littering the lawn. These branches are reachable, chest-level, and I weave in toilet paper, methodically walking round and round, wrapping

this tree like a mummy. One roll, another, stretching on tiptoe to layer tissue as high as I can.

Is this anger? I’m so calm.

I take care of the second tree, coating it with every last square, sorry there’s not more. I pause, wondering if I should grab our cheap toilet paper, and when I glance toward the house, there’s Tracy standing framed in her lit bedroom window. She’s wearing a pale nightgown, standing perfectly still like she’s a painting of a child, not a real child. I’m certain I’m hidden within this darkness. I’m certain she can’t see me. But she lifts one hand and waves. I can’t stop myself: I wave back, then turn away.

This ridiculous night. Watch it rain later and make this mess worse. The neighbors will see my shame tomorrow morning.

Nothing to do but slink through the front door, flip the porch light off because electricity’s not free, and walk down the hall. When I get to Tracy and Suzanne’s bedroom, the crack under the door is dark, so I pass by, into my bedroom, and tuck myself neatly into my side of the bed. J.P.’s asleep or fake-asleep, and I wait for him to say something, but it’s only snores. Maybe this is how decisions get made.

J.P.’s off early to a Chamber of Commerce meeting, so I’m excused from frying eggs and bacon. That makes breakfast before school a dull commotion over peanut butter toast and cereal. Kim’s wailing about the soggy toilet paper in the front yard, how someone at school hates her and who could it be, how her life’s ruined because she’ll never make winter cheerleader now: “What’s the point of anything?” Her words overflow. The little kids fidget nervously, ducking their heads low over their cereal bowls, shoveling in every last bit instead of fussing about who has more pink marshmallows. Suzanne and Tracy sit side by side on the bench, Suzanne tracing pictures in her peanut butter toast with a knife, smoothing it out and starting again. Tracy’s staring into space, food forgotten, cereal soggy—she’ll waste away if I don’t stop her—and I know she saw me last night, but she’s silent this morning, a glimmer of a smile as if there’s a joke rattling in her head that she knows none of us will understand.

Kim waves a spoon and shrieks, “Who? Who hates me so much? Who TPs me? I’m popular! What does this mean?”

I interrupt: “Kim. Pipe down and clean it up. Probably no one’s even seen it yet. You’ll be FINE!” I don’t think I’m shouting, but then I definitely am: “Clean every last bit up now!”

Her mouth hangs open. I’ll let her too-much lipstick go this once. “Mo-om!” She’s shocked; everyone’s shocked. This table of girls stares at me with burning eyes. “Oh, puh-lease. Mom?” Kim’s tone is off, and instead of her usual sneer, she’s begging.

“Right now,” I say. “Do you want your friends to see?” “Me?”

“It’ll take ten minutes.”

“Will not,” she whines. “Have you ever cleaned up TP mess? It’s gross.”

I shake my head, uninterested. “I’ve cleaned up plenty,” I say, “and I’m just not cleaning this. Guess sloppy toilet paper will stay in our trees until the end of time.”

Kim huffs and howls. But it’s Tracy I’m studying now, because she’s studying me, giving me that look of knowing something. Her eyes narrow.

I smile brightly. “You look like maybe you have a secret,” I say pleasantly.

She shakes her head.

“Good girl,” I say. “Secrets are for snakes.”

“I like every animal,” she says. “Even snakes.”

“My little loving angel,” I say. “All you girls. You’re all my precious angels.”

Eye-rolling. Laughter. Embarrassment. But I’m glad to tell them something nice today before they head off to school. There are all kinds of ways to learn, right, and who’s to say a mother can’t teach better than a hateful man who won’t let girls build birdhouses?

When the house is empty, when the dishes are done, when the floor’s swept, when the hamburger’s out of the freezer defrosting, when I clean the cats’ litterbox, I pick up the phone, imagining all the men in all the offices calling people all day long like that’s so normal.

Imagine living like a man, coming and going and doing exactly as he pleases, a man who wants his eggs every day over easy, brought exactly to where he sits, along with a mug of coffee, someone remembering it should be black. My husband doesn’t think about me when he drinks beer and shoots the breeze with his friends, when he whatevers with whomever, when he watches Carly in her miniskirt blowing smoke rings, when he says, Yes. Imagine living a life in secret. Imagine.

“My friend Jane gave me this number,” I say when someone picks up, and the rest is as easy. I imagine I’m that first woman making her first gigantic decision, biting that apple, thinking, Delicious, thinking, What if I keep this all to myself?

Leslie Pietrzyk’s collection of linked stories set in DC, Admit This to No One, was published in 2021 by Unnamed Press. Her first collection of stories, This Angel on My Chest, won the 2015 Drue Heinz Literature Prize. Her short fiction and essays have appeared in Ploughshares, Story Magazine, Hudson Review, The Southern Review, Gettysburg Review, The Iowa Review, The Sun, Cincinnati Review, and The Washington Post Magazine, among others. Her awards include a Pushcart Prize in 2020. She is a member of the core faculty in Converse University’s low-residency MFA program, teaching fiction and creative nonfiction.

Leslie Pietrzyk

About her story “F-I-N-E,” Pietrzyk writes, “I’ve been working on a number of stories set in the same 1970s Midwestern neighborhood. Initially, the stories revolved around a group of girls exploring how the dynamics of their friendships change when one of them goes missing. The girls mentioned in this story— Tracy, Holly, Suzanne—are among that group. It wasn’t long before the questions in my head about these girls led to questions about their mothers. ‘F-I-N-E’ is the first story in this set that I attempted from a mother’s point of view.

“While my story is fictional, it was informed by my discovery as an adult that my own mother’s best friend from college became an early member of Jane, an underground collective of badass, upper-middle-class Chicago women who learned to perform abortions and then—before Roe v. Wade secretly and as safely as possible provided this service, at low cost, with compassion and no judgment. Some of the women, including my mother’s friend, were arrested, and everyone involved took great personal risk to address the problem of unwanted pregnancies. Ads read: PREGNANT? DON’T WANT TO BE? CALL JANE.

“To learn more, I read The Story of Jane: The Legendary Underground Feminist Abortion Service by Laura Kaplan. Notable to me was that among the

many women Jane served were mothers with children, like my characters MaryMargaret and Carly, who knew the impossibility of taking on one more child. For some, the decision to safely terminate a pregnancy was gut-wrenching, though for many it was a relief. After reading this book, I saw I wasn’t the writer who could fictionalize the Jane collective itself, but I figured I could ask the hard questions about what it would be like to be pregnant in 1971 and not want to be.

“Writing the story challenged me. I ended up with nineteen separate files on my computer, due to constant cutting-and-pasting, adding scenes and deleting others, rethinking each character’s responses. My story grew and grew, and I tried to ignore the difficulty of placing a long manuscript because I wanted to do the story justice. Writing about abortion is tricky, as is writing about abortion in 1971, because attitudes may not translate to a modern reader. I finally felt locked in when Mary-Margaret’s voice sharpened with a snarky remark I didn’t expect, and I saw that she was no victim.

“I often write to open-ended, one-word prompts, and this story started in a fiction workshop I led at the Converse University low-residency MFA program. Some of the words that sent my story moving early on were innocuous: alien, wilderness, lamp, telephone, and string. Another section was written in my monthly prompt group, to the words harsh and wall. My favorite thing about prompts is not knowing where the writing will flow to, just trusting it will get somewhere, that the parameters of a prompt will shake something loose.

“Finally, a tiny personal note: I was in the first group of girls required to take shop class at Southeast Junior High in Iowa City. At the time, I was relieved we didn’t have to make lamps like poor Tracy; we got off easy with cutting boards shaped like apples or pears, and we spent most of our time rubbing sandpaper along rough edges. Now I see the insult.

“My gratitude to Iron Horse Literary Review and the editors for selecting my story for this honor and for giving long stories such a gorgeous home. Sometimes a story needs room.”

Acknowledgments

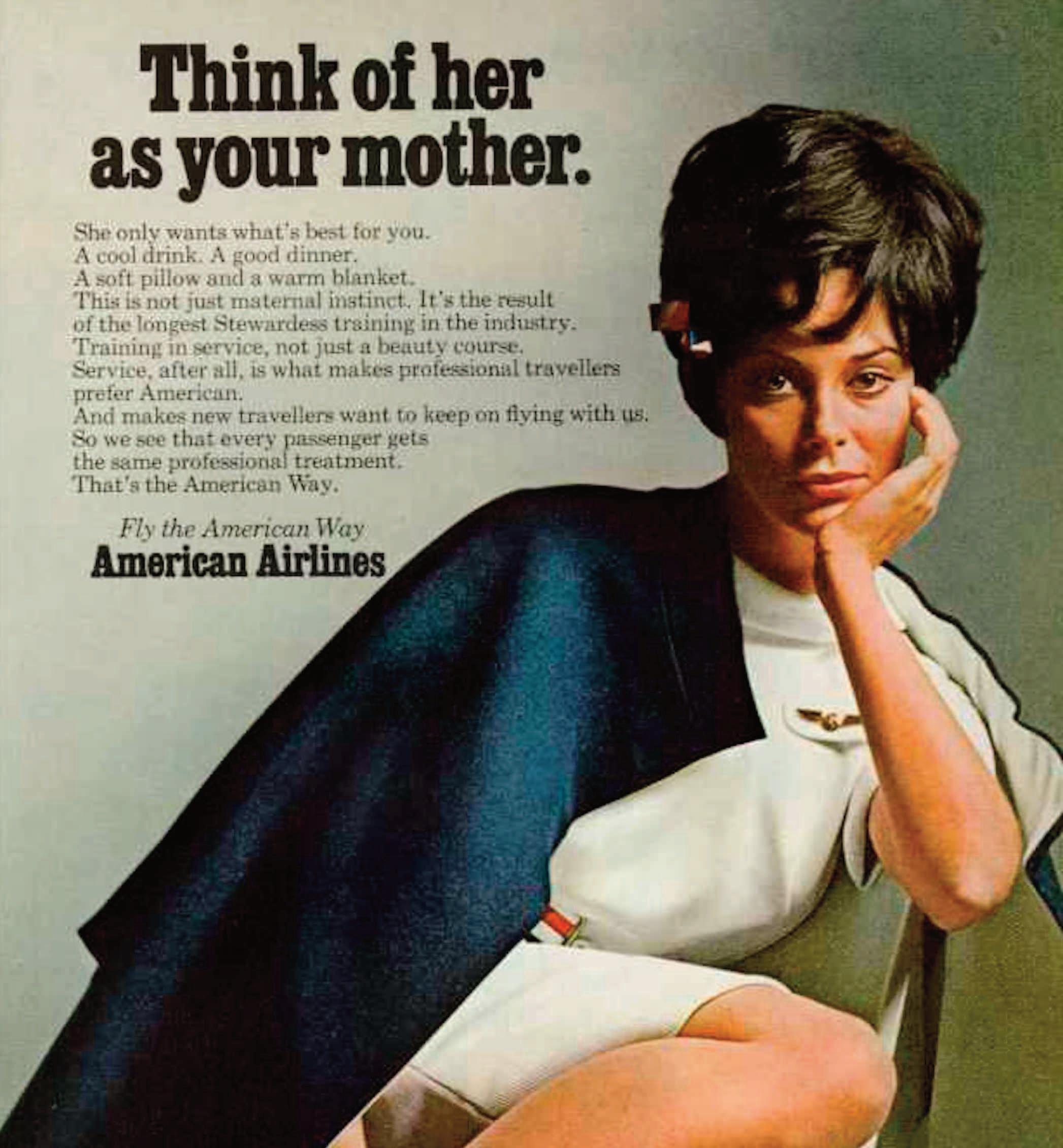

page 3: American Airlines, 1968. Source: Kirstin Butler. “The Golden Age of Flight Wasn’t So Golden for Flight Attendants.” PBS.org (7 February 2024): https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/ features/fly-with-me-golden-age-advertisements/.

page 6: Tipalet, Muriel Cigar Company, 1969. Source: Harrison Jacobs and Jim Edwards. “26 Sexist Ads of the Mad Men Era That Companies Wish We’d Forget.” Business Insider (4 April 2015): https://www.businessinsider.com/26-sexist-ads-of-the-mad-men-era-2015-4.

page 10: Weyenberg Shoe Mfg. Co., 1974. Source: Megan Garber. “‘You’ve Come a Long Way, Baby’: The Lag Between Advertising and Feminism.” The Atlantic Monthly (15 June 2015): https://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2015/06/advertising-1970s-womens-movement/395897/.

page 15: Brown, 1973. Source: Harrison Jacobs and Jim Edwards. “26 Sexist Ads of the Mad Men Era That Companies Wish We’d Forget.” Business Insider (4 April 2015): https://www.businessinsider.com/26-sexist-ads-of-the-mad-men-era-2015-4.

page 16: Clairol, 1971. Source: Yeoman Lowbrow. “Vintage Hair Adverts: 1960s-70s Products, Styles, and Tragic Cuts.” Flashbak.com (2 January 2015): https://flashbak.com/vintage-hair-adverts-1960s-70s-products-styles-and-tragic-cuts-28499/.

page 20: Virginia Slims, Philip Morris International, 1969. Source: George Heymont. “Big Girls Don’t Cry.” Huffington Post (19 July 2015): https://www.huffpost.com/entry/big-girls-dont-cry_b_7828154.

page 23: Mini, Volkswagen, 1971. Source: Ashley Mosaic. “These Vintage Ads Illustrate Why the World Needs Feminism.” Medium (20 January 2016): https://medium.com/human-development-project/thesevintage-ads-illustrate-why-the-world-needs-feminism-b8549a3edffa.

page 24: Jell-O, 1970. Source: Harrison Jacobs and Jim Edwards. “26 Sexist Ads of the Mad Men Era That Companies Wish We’d Forget.” Business Insider (4 April 2015): https://www.businessinsider.com/26-sexist-ads-of-the-mad-men-era-2015-4.

page 29: Hazel Bishop, 1967. Source: Unnamed Author. “Comestics and Skin: Hazel Bishop.” Cosmetics and Skin (4 November 2022): https://www.cosmeticsandskin.com/companies/hazel-bishop.php.

page 34: Total, General Mills, 1970. Source: Ashley Mosaic. “These Vintage Ads Illustrate Why the World Needs Feminism.” Medium (20 January 2016): https://medium.com/human-development-project/thesevintage-ads-illustrate-why-the-world-needs-feminism-b8549a3edffa.

page 37: Virginia Slims, Philip Morris, 1970. Source: Wikimedia Commons: https://en.wikipedia.org/ wiki/File:Virginia_slims_ad_1970.jpg.

Iron Horse Literary Review would like to thank its supporters, without whose generous help we could not publish Iron Horse successfully. In particular, we would like to thank our benefactors and equestrian donors. If you would like to join our network of friends, please contact us at ihlr.mail@gmail.com for information on the various levels of support.

Benefactors ($300)

Wendell Aycock

Lon and Carol Baugh

Beverly and George Cox

Sam Dragga

Madonne Miner in memory of Charles Patterson

Gordon Weaver

Equestrian ($3,000 and above)

TTU English Department, Chair Brian Still

TTU College of Arts & Sciences, Dean Michael San Francisco

TTU Graduate School, Dean Mark Sheridan

TTU Provost’s Office, Provost Michael Galyean

TTU President’s Office, President Lawrence Schovanec