The Irrawaddy magazine has covered Myanmar, its neighbors and Southeast Asia since 1993.

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF: Aung Zaw

EDITOR (English Edition): Kyaw Zwa Moe

ASSOCIATE EDITOR: Sandy Barron

COPY DESK: Neil Lawrence, Paul Vrieze, Samantha Michaels, Andrew D. Kaspar, Simon Lewis

CONTRIBUTORS to this issue: Aung Zaw; Kyaw Phyo Tha; Yan Pai; Simon Lewis; Bertil Lintner; Nyein Nyein; Dani Patteran; Kyaw Hsu Mon; Grace Harrison; Zarni Mann; Marwaan Macan-Markar; Thit Nay Moe; Seamu Martov.

PHOTOGRAPHERS : JPaing; Sai Zaw.

LAYOUT DESIGNER: Banjong Banriankit

SENIOR MANAGER : Win Thu (Regional Office)

MANAGER: Phyo Thu Htet (Yangon Bureau)

REGIONAL HEADQUARTERS MAILING ADDRESS: The Irrawaddy, P.O. Box 242, CMU Post Office, Chiang Mai 50200, Thailand.

YANGON BUREAU : No. 197, 2nd Floor, 32nd Street (Upper Block), Pabedan Township, Yangon, Myanmar. TEL: 01 388521, 01 389762

EMAIL: editors@irrawaddy.org

SALES&ADVERTISING: advertising@irrawaddy.org

SUBSCRIPTIONS: subscriptions@irrawaddy.org

PRINTER: Chotana Printing (Chiang Mai, Thailand)

PUBLISHER LICENSE : 13215047701213

16 | Culture: Forgotten, but Not Gone

Half a millennium after the Portuguese first set foot in Myanmar, their legacy lives on in a remote corner of the country’s north

20 | History: Making Opium (and the Past) Go Away

A peculiar little museum in a remote corner of Shan State shows how to eradicate drugs—and erase history

22 | Politics: Whose Army?

Despite what his daughter says, today’s Tatmadaw was not Gen. Aung San’s creation

27 | COVER Yangon Switches On New gas-fred power plants raise hopes that the annual hot-season power drought may soon be a thing of the past

34 | Interview: A Developer’s Dream: Housing for All

38 | Timber: India Leads the Pack in Timber-Processing

As the ban on exporting raw timber goes into effect this month, India has emerged as the largest investor in the processing industry

40 | Small Business: Local Enterprise with a Big Reach

The parasols of Pathein combine tradition with innovation and prove a hit in the hot season

42 | Signposts: Taxing times

44 | In Thai Peace Talks, a Challenge to Military Dominance

In the internal struggle over who’s in charge of ending a decade-old insurgency in Thailand’s south, the powerful army appears to be losing out

Though Naypyitaw has made significant progress in recent years’ peace talks with Myanmar’s numerous ethnic rebel groups, clashes between government troops and Kachin fighters continue, stymieing efforts to bring an end to the country’s long-running civil war.

As both sides gear up for negotiations this month aimed at reaching a nationwide ceasefire agreement, The Irrawaddy sat down with La Nan, spokesman and joint secretary of the Kachin Independence Organization (KIO), at the rebels’ stronghold in Laiza on the Sino-Burmese border.

Speaking from the KIO office—a building that once operated as a casino—La Nan talks to Irrawaddy reporters Nang Seng Nom and Yen Snaing about the ongoing fighting between the KIO’s armed wing (the Kachin Independence Army) and the Myanmar military, as well as discusses peace process prospects and China’s role in Myanmar’s national reconciliation.

have already given the draft to them and they brought it to Naypyitaw. When they discussed it, we heard that the army was quite pessimistic about it.

They take issue with the fact that they are being asked to accept a plan drawn up by revolutionary groups. They say, “Shouldn’t the Union Peacemaking Working Committee draft the plan and negotiate with the ethnic armed groups from there?”

They also say that once a ceasefire agreement is signed, all groups are effectively agreeing to accept the 2008 Constitution, meaning all political discussions would proceed in accordance with what is said in the Constitution. We have heard that the army is of this view.

In March, U Aung Min and ethnic groups will meet again, but there is not much hope because the current peace process is not adequate. As we have always said, we are urging a political dialogue led by the UNFC [United Nationalities Federal Council, an alliance of 11 ethnic armed groups].

When will the KIO sign a ceasefire? Will it be only under the terms of the draft agreement submitted to the government?

What is the current situation regarding armed hostilities between the KIA and the Myanmar army?

We can say that the battles are now fewer. Whenever we talk with the Union Peace Working Committee, we discuss ways to reduce the number of battles occurring, but we can’t yet say completely that there is no fighting anymore.

The type of battles occurring has changed. Instead of direct offensives like before, it has become surprise attacks against our posts. They [the Myanmar military] occupy some places for a week or two and then step back. They make it look as though it is not a war about occupying territories.

What is the KIO’s view of the current peace talks between ethnic armed groups and the central government?

What we have always pushed for is a political dialogue, together with all ethnic armed groups. That’s why we have held two ethnic armed groups’ conferences at Laiza and Law Khee Lar, in KNU [Karen National Union] territory.

What we discussed in Law Khee Lar was drafting the text of a nationwide ceasefire agreement to be discussed with the Union Peacemaking Working Committee. But what we heard back was that the Ministry of Defense disagreed with what [President’s Office Minister] U Aung Min was doing. We

We are asking for political dialogue. When political problems are solved, there will be no more battles. The ceasefire will happen then, not because a piece of paper has been signed.

We have seen the signing of many ceasefire agreements before. Nothing came into force. They let us open a liaison office, that’s it. No political discussion. What we believe is that when the political problems are solved, the ceasefire will happen.

Before a nationwide ceasefire agreement is made, we need a framework that will guide us in how we are going to arrive at political discussions after the ceasefire agreement—how long after. It’s like a roadmap. If both sides can agree on

that political framework, we will sign a nationwide ceasefire agreement.

What is your opinion of Armed Forces Commander-in-Chief Snr.-Gen. Min Aung Hlaing’s involvement in the peace talks?

We are not dictating who we will or will not talk to. We have our representatives, the government has its representatives. What we understand is that the government’s group is being led by U Aung Min and a state-level committee assigned by President U Thein Sein. Their words represent the state’s. If they want to include the commander-in-chief, that’s fine. Whoever is involved, we are ready to talk with them.

What do you think of President U Thein Sein’s push to sign a nationwide ceasefire agreement this year?

We haven’t seen the will to solve the political problems. We haven’t seen the government’s true intentions vis-à-vis ethnic armed groups. They used to talk about this in their speeches, but there has been no practical implementation up until now. Dry season military offensives continue, and there will be more battles in 2014 if the KIO does not show restraint.

The year 2012 has passed. They were saying that the ceasefire could be done by that time. When U Thein Sein began his term as president, he said that in a speech, and also a number of times in 2013. He will continue to say it. But the signing is on a piece of paper of no value. If the signing happens, the government will reap more benefits internationally. But in our ethnic areas, nothing will have changed. To make it a real ceasefire, they should reduce their military operations.

What is China’s role in the peace process?

They put a lot of pressure on us. When there are severe battles, they put pressure on us in Laiza to come

to a ceasefire quickly. They don’t understand that the battles happening are part of a political and civil war. They think in terms of stability on China’s border. They can trade when the situation is stable. I think they see the battles in terms of business. When the fighting is fierce, instead of telling the government to stop, they tell us to sign a ceasefire. So, we can say China’s government is in some way involved in the peace process. Whenever we say there should be international witnesses to our discussions, they send their Asian affairs officer.

But as their general foreign policy, they do not meddle in other countries’ affairs. Their only intention is to prevent battles on China’s borders. They do not seem to have any deep concern about whether the problems get solved or not. We accept China because we have to deal with them,

but due to pressure from the Chinese government, we have suffered more. They talk and pressure us to do what the Myanmar government wants, but they do not intervene to solve the ethnic armed groups’ grievances. They just want a ceasefire agreement signed quickly.

How long do you think this peace process will take?

If the form of the ruling government changes, this problem will be solved quickly. But it will not happen with the current ruling party, the Union Solidarity and Development Party. We don’t know how long it will take. It might get worse than the current situation. If the situation reaches a point that ethnic armed groups cannot tolerate, civil war could flare up again. The civil war is not over yet, so we cannot guess how long it will take.

PHOTO: SAI ZAW / THE IRRAWADDY—European Union Trade Commissioner Karel De Gucht, speaking in Vietnam in March.

—Marang Kawnt, 65, a Kachin grandmother speaking at a refugee camp at Border Post 6 in northern Kachin State.

—U Tun Lwin, a former director-general of the Department of Meteorology and Hydrology and now chief executive at Myanmar Climate Change Watch, warning about rising levels of UV radiation during the hot season.

“It’s at a dangerous level. It’s better not to go outside during the day, and…wear clothes that fully cover the body.’’

“My life started with war, and now it will end with war.”

“Our investors must be protected and it’s important to Myanmar because if the investments aren’t protected, they simply won’t happen.”

Myanmar’s moves toward ending decades of ethnic conflict are in danger of being derailed by recent clashes in the country’s north, a senior

ethnic leader warned. Khun Okkar, the jointsecretary of the United Nationalities Federal Council, an alliance of 12 ethnic armed groups, said

that the fighting in Kachin and Shan states could undo gains made over the past two years. “I am worried that [Myanmar] is going to have civil war again,” he said at a press conference in Yangon at the conclusion of the twoday Civil Society Forum for Peace, held March 3-4. Ethnic Kachin, Shan and Palaung armed groups say they have all come under attack from Myanmar’s government army since late February. However, Lt.-Gen. Myint Soe, commander of the Bureau of Special Operations-1, which oversees military operations in Kachin State, denied that the army had launched new offensives.

All squatters living in Myanmar’s largest city face eviction from the end of March, U Than Aung, the secretary for the Yangon Region government, said at a press conference in late February. “All illegal squatter houses will be demolished” because the city can’t continue to accommodate them, he said. Col. Win Tin, the division’s minister for border affairs, called the plan “inevitable,” but added that no provisions

had been made to resettle the displaced squatters.

Myanmar is still buying conventional weapons from North Korea, the US Defense Department said in a report to Congress released on March 5. The report said that Pyongyang uses a worldwide network to facilitate arms sales to a core but dwindling group of recipient countries, including Iran, Syria and Myanmar. The US has pressed the Myanmar government to stop buying from North Korea, also previously suspected of supplying Myanmar with missile technology. In December, the US blacklisted a Myanmar military officer and companies for continued

weapons trading with North Korea. Myanmar denies violating UN sanctions that prohibit such weapons purchases.

The European Council on Tourism and Trade (ECTT), a non-governmental organization based in Bucharest, Romania, will hand Myanmar its “World Best Tourist Destination Award” for 2014, according to the Ministry of Hotels and Tourism. The award is given to “countries that are embracing tourism as a resource for cultural and social development, who respect ethics of human relations and preserve cultural and natural heritage. As the receivers, cities and countries must prove their commitment

towards sustainable development, fair tourism and historical preservation,” the ECTT states on its website. Previous winners include Turkey, the UAE, Syria and Laos.

Myanmar President U Thein Sein has ordered a new commission and the country’s highest court to draft a “protection of race and religion” law, which could include measures to restrict interfaith marriage,

Two new laws governing Myanmar’s media went into effect in March, officially ending the era of the draconian 1962 Printers and Publishers Registration Act. The Press Law, drafted by the Interim Press Council, a body consisting mostly of journalists formed in 2012 to regulate Myanmar’s media industry and propose reforms, was approved by the country’s Union Parliament and signed into law by President U Thein Sein in the third week of March. At the same time, however, another law submitted by the Ministry of Information, the Printers and Publishers Registration Law, also went

into effect. Journalists criticized the latter law for being too restrictive, noting that it gives the ministry the power to withhold or revoke pub-

lishing licenses for breaching vaguely defined bans on reporting that could “incite unrest,” “insult religion” or “violate the Constitution.”

according to lawmakers. The move comes after a petition with 1.3 million signatures was submitted to the president urging him to pass into law a version of a bill drafted by lawyers on behalf of leading monks in the Buddhist nationalist 969 movement. If enacted without amendment, the bill would require Buddhist women to get permission from their parents and local government officials before marrying a man from another faith. It also includes restrictions on converting to another religion, a limit to the number of children people can have, and measures to stop polygamy.

Tomás Ojea Quintana, the outgoing United Nations special rapporteur on human rights in Myanmar, noted “significant changes” for the better in the country’s overall rights situation in his final report to the UN Human Rights Council on March 17. Mr. Quintana made his last trip to Myanmar in mid-February, traveling to the Rakhine State capital Sittwe, the Kachin rebel stronghold of Laiza, and two sites of alleged land grabs—the Letpadaung copper mine in Sagaing Region and the Thilawa Special Economic Zone in Yangon Region. In his report, he also urged the world body to get involved in an investigation into allegations that dozens of Rohingya Muslims were killed in a mob attack in January, citing the government’s failure to conduct a credible investigation on its own.

PHOTO: JPAING / THE IRRAWADDY A woman sells newspapers in Yangon. The temples of Bagan are one of Myanmar’s main tourist draws.

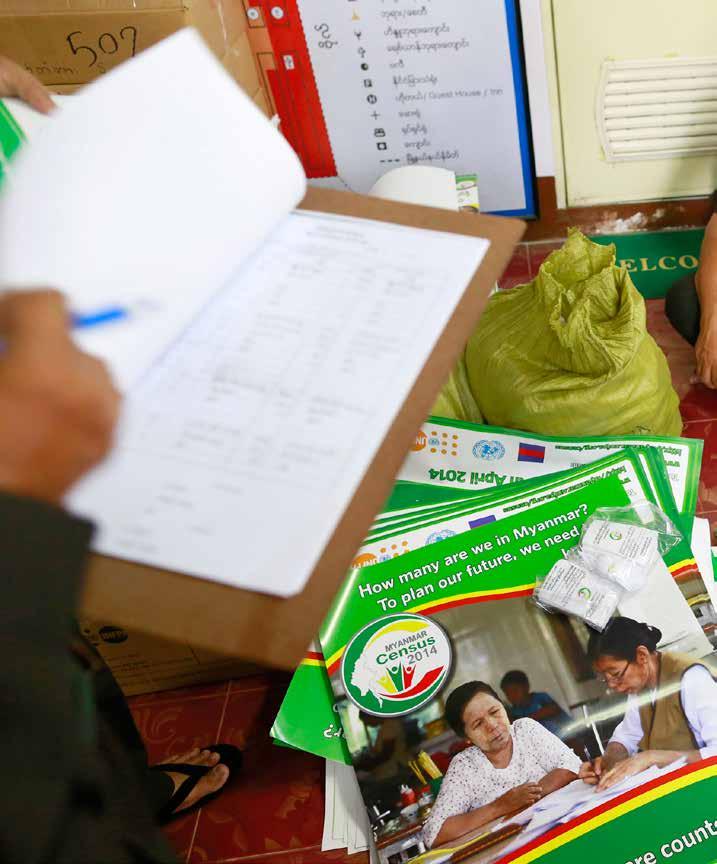

Immigration officers check forms in Kyauktada immigration office in Yangon as they prepare for the Myanmar 2014 census. During April, enumerators are set to fan out over a vast swathe of the country for the first census in over 30 years. The controversial survey takes place amid wide criticism that it could revive historic ethnic divisions.

When Malaysian Airlines Flight 370 disappeared on March 8, one of the many serious issues it raised about the safety of international travel is the fact that there is a thriving worldwide trade in stolen passports.

As investigators started trying to determine the cause of the incident, one of the first things they discovered was that two of the passengers were Iranian nationals traveling with EU passports that had been stolen in Thailand. Although it turned out that the two men were not terrorists, the ease with which they were able to pass through airport security with their fake identities was unsettling for many.

It is even more disturbing to learn that the world is awash in false documents. According to a senior member of Thailand’s National Security Council who spoke to the Londonbased newspaper The Independent, around 10,000 passports are lost or stolen in the country each year, many of which end up in the hands of foreign forgers.

By AUNG ZAW

By AUNG ZAW

Thailand’s huge fake-document market undoubtedly caters to criminals of every description, from mafia types to human traffickers and terrorists. But among those who have used the services of these passport forgers are many individuals whose only goal is to escape poverty or repression in their home countries.

For many years, Myanmar was one of the world’s leading sources of such people. And among the millions who fled in search of work or freedom, there were countless thousands who needed to assume new identities.

In the early 1990s, as an exile living in Thailand, I witnessed the operations of a passport mill working out of a small apartment in Bangkok. A small machine was used to press photos, visa stamps and stickers into blank passports. Everything was scattered all over the room, as the workers in this “passport-making factory” cranked out one fake passport after another to meet demand from Myanmar nationals who

For many Myanmar dissidents living in exile, forged travel documents were the only thing standing between them and prison

needed to extend their stay in Thailand or who planned to take their chances in Japan or some other country that offered a shot at a better life.

In those days, Myanmar exiles had one of two choices: stay in the jungle along the Thai-Myanmar border, or venture into Thailand’s cities to try to make contact with foreign governments and organizations that wanted to know more about what was happening in the military-ruled hermit state that had suddenly and unexpectedly exploded in 1988.

For those of us who took the latter course, a passport was indispensable. Since there was certainly no chance that the government would issue documents to “destructive elements” like us, the only option was a fake passport.

For around US$500 (a fee that rose steadily over the years, as the quality of the passports improved), agents could provide you with a Myanmar passport complete with a Thai visa, delivered within one month. It was a lucrative business, and one that provided a measure of security for those without any legal documentation.

That isn’t to say, however, that it was without risks. There were more than a few unlucky holders of these fake passports who landed in Bangkok’s infamous Immigration Detention Center. Even in Thailand, with its vast false-documents industry, traveling with a fake passport is considered a serious crime.

I know well how nerve-wracking it can be to go through immigration with a passport bearing a name and personal details that were not my own. Every time I entered or left Thailand or another country, my heartbeat and my mind raced as I tried to think of what I should say if the immigration officer challenged me. Of course, I could always produce the invitation letters that I had received from whichever institution or government had asked me to attend or speak at some event abroad, but I was still always acutely aware of the fact that technically, I was breaking the law and could face severe

punishment if caught.

These days, like many other long-time exiles, I hold a legal travel document from a country sympathetic to the plight of Myanmar’s political dissidents. There are several countries, mostly in the West, that have issued such documents to help those of us who until recently could not return to Myanmar to do our work.

Ironically, these documents now serve as an obstacle to former exiles who want to return to their country, as the Myanmar government regards such document-holders as foreign nationals who must get visas to travel to the country of their birth. From the government’s point of view, it would have been better if we had remained undocumented or continued to risk using fake passports until such time as the country’s rulers saw fit to invite us back to participate in their muchvaunted reforms.

Meanwhile, demand for fake Myanmar passports has declined, but not died out entirely. As long as there are many who remain dissatisfied with the pace and direction of change in the

country, the trade will likely continue.

After decades of serving as an important lifeline for dissidents, however, there is now a danger that forged Myanmar passports could come to be used for more nefarious purposes. It would be all too easy, for example, for a terrorist to acquire and travel with a Myanmar passport to conceal his true identity.

We can only hope, then, that Myanmar—a country that is increasingly on the radar of extremist groups because of its mistreatment of Muslims—doesn’t suffer yet another tragedy before it has even had a chance to recover from the years of abuse that it suffered at the hands of its rulers.

Sadly, as the fate of Malaysian Airlines Flight 370 reveals, there are few certainties in this world. But one thing we do know is that the legacy of brutal misrule is not something that disappears overnight, especially when the work of ending it has barely begun.

Aung Zaw is the founding editor-inchief of The Irrawaddy. PHOTO: REUTERSMyanmar has a long and complicated history, full of footnotes that could take up whole chapters. One episode that still stands out, even though precious little remains to remind us of it today, came in the early 17th century, when Portuguese adventurers held the fate of kingdoms in their hands.

The Portuguese first started arriving on Myanmar’s shores some 500 years ago, but it was not until 1599, when the mercenary Filipe de Brito e Nicote wrested control of Thanlyin (Syriam)

away from the powerful Taungoo dynasty, that they gained a foothold in the country.

De Brito (known in Myanmar as Nga Zinga) was subsequently named governor of this strategically important port on the Bago River opposite Yangon (then called Dagon) by the Rakhine king Min Razagyi, in whose service he had captured it. But his true loyalties soon revealed themselves when, in 1603, he claimed Thanlyin for Portugal.

Once in power, de Brito quickly earned a permanent place in Myanmar’s annals of infamy by plundering

U Ba Htay, 89, is from the village of Monhla, home to around 170 Bayingyi households.Buddhist temples for their bells, which he had recast as cannons. His reign was short-lived, however: In 1613, King Anaukpetlun reclaimed Thanlyin for the Taungoo dynasty, and had de Brito impaled for desecrating Buddhist holy sites.

For most in Myanmar, that is where the story ends. What few realize, however, is that in a remote corner of Sagaing Region some 93 miles (150 km) northwest of Mandalay, the legacy of de Brito’s brief foray onto the stage of Myanmar history lives on to this day.

After de Brito was executed, most of the 5,000 Portuguese soldiers who had served under him were transported to Innwa (Ava), then the Taungoo capital, as prisoners of war. Some were recruited to serve as military advisers, but the bulk, it was decided, were best resettled somewhere else, at a safe distance from the seat of power.

That is how the Bayingyi, as these former Portuguese mercenaries and their descendants are known, came to inhabit a handful of villages in the dry, inhospitable region between the Mu and Chindwin rivers.

Today, in villages like Monhla and Chanthar in the valley of the Mu River, the surviving Bayingyi eke out a modest living as farmers or traders, and are almost indistinguishable from their

Left: The Church of the Assumption in Chanthar villageBuddhist neighbors apart from certain features, such as their long, straight noses and light-colored eyes.

“My parents told me that we were descended from the Portuguese, but really, we are all mixed up,” says U Ba Htay, 89, from the village of Monhla, located about 14 miles (22.5 km) west of the town of Khin-U.

households, and despite its modest size, is graced with an impressive Catholic church, St. Michael’s, built in the Gothic style to accommodate the tombs of Barnabite priests from Italy who came to minister to the Portuguese banished to this area. Among those interred here is Father Giovanni Maria Percoto, who played a major role in bringing Western

still feel that because of my heredity, I should support the Portuguese team when they’re playing football,” says Father Paul Thet Khing from Chanthar, a village in Ye-U Township that is home to more than 1,100 Bayingyi.

Despite their ties to a foreign land, in the centuries that followed their forced resettlement here, the Bayingyi fought bravely alongside Myanmar troops to defend the country from outsiders, helping to defeat the Chinese during the war of 1765-1769, and suffering great losses in the First AngloMyanmar War of 1824-1826.

Despite his piercing grey eyes and tall stature, U Ba Htay is in most respects a typical man of Anyar, as this region is known: He has the distinctive sense of humor of the local people of this region, and speaks with a strong Anyar accent as he puffs away on a cheroot rolled up in a corn husk.

Monhla has around 170 Bayingyi

learning to pre-colonial Myanmar in the late 18th century.

These days, most of the priests serving local congregations are natives of the area. Despite this, however, many still profess loyalties to a distant land that few have ever visited.

“Many generations have passed since our ancestors came here, but I

Sadly, however, their unique identity has long since been erased. Apart from their religious affiliation, nothing survives of the culture of their forebears, and since the socialist era (1962-1988), they have been required to identify themselves as ethnic Bamar rather than as Bayingyi.

“After 400 years of intermarriage, there is nothing left of our Portuguese culture for us to preserve,” concedes another priest, Father Alphonse U Ko Lay. “All that remains now is our faith, and the only thing we can do to keep that alive is practice our freedom of worship.”

Above: Daw Mar Di, from Chanthar, and, below, her son“My parents told me that we were descended from the Portuguese, but really, we are all mixed up.”

—U Ba Htay

Mong La’s opium museum has to be one of the more interesting institutions created during the days of Myanmar’s State Law and Restoration Council (SLORC). Located in Shan State’s Special Region No. 4, an almost completely autonomous corner of northeastern Myanmar, the museum was founded by Lin Mingxian (also known as Sai Lin or Sai Leun), a former rebel commander in the Communist Party of Burma (CPB) and long-time

leader of his own 5,000-strong militia, the National Democratic Alliance Army (NDAA). During the 1990s, Lin and his group were alleged by US authorities to be heavily involved in the drug trade.

Lin, who is of mixed Chinese and Shan heritage, has ruled over his 1,900-square-mile (4,950-square-km) Golden Triangle fiefdom ever since 1989, when he and his fellow ethnic comrades rebelled against the CPB’s overwhelmingly Burman politburo and reached verbal ceasefires with the

SLORC that split the CPB’s territory and its massive cache of weapons four different ways.

Built at the base of a hill close to Mong La’s standing Buddha, the museum offers an interesting alternative to the NDAA region’s other attractions—namely, its casinos, brothels and stores selling tiger skins and ivory. It is especially likely to appeal to those adverse to large crowds: On a recent visit, this correspondent found the museum devoid of any other visitors, or, indeed, of any staff.

One of the museum’s more memorable attractions is a life-size diorama portraying a drug addict’s journey to recovery. Unfortunately, however, the glass case was caked in so much dust that it was rather difficult to see inside. But you can still see enough to get the general idea. The first scene shows two young men injecting heroin. Besides the telltale hypodermic needle, you can tell they are addicts because they are sporting long hair, jeans and matching “Bad to the Bone” T-shirts. In the next scene, one of the duo is lying dead with a needle protruding from his arm while the other is being led away in handcuffs. The survivor is then seen in

a hospital bed being well looked after. In the last scene, the survivor is clearly a changed man: Not only has he kicked drugs, he’s also gotten a haircut and put on a longyi.

Much of the rest of the museum is made up of faded propaganda photos from the military’s anti-narcotics drives and similarly themed murals. Another section has a series of pictures from the SLORC regime’s negotiations with various factions that broke away from the CPB. Unmentioned in the captions is the presence of the late Lo Hsing Han in several of the photos. Dubbed the “godfather of heroin” by US authorities, Lo was an ethnic Kokang Chinese drug lord turned tycoon who served as a key mediator during SLORC’s talks with the ex-CPB groups.

Although Snr-Gen. Than Shwe officially stepped down as Myanmar’s head of state nearly three years ago, a large portrait of him still hangs next to the front entrance, with an awkwardly worded quote of his in English. “The drug abuse control because it is related to all the people of the entire world is a very huge and difficult task. We are willing to warmly welcome sincere participation by anybody. Even if there is no assistance whatsoever, we will do our utmost with whatever resources and capability we have in our hands to fight this.” The same quote is also featured in the Yangon drug museum, which opened in 2001 and was apparently modelled after the one in Mong La.

One thing you won’t find here are any reminders of another former SLORC leader who played an even bigger role in bringing the region’s drug lords “into the legal fold,” to use the old SLORC-speak. The numerous photos previously on display of the NDAA’s long-time ally, deposed Military Intelligence Chief Gen. Khin Nyunt, were removed long ago. Prior to his fall from power in 2004, the notorious spy chief inaugurated the museum’s opening and frequently attended Mong La drug-burning ceremonies.

When the museum was officially opened in April 1997, Lin and his NDAA were making regular appearances in the US State Department’s annual International Narcotics Control Strategy Reports. The reports accused Lin of being heavily involved in the drug trade, alongside his former CPB comrades in the United Wa State Army (UWSA) and the Kokang-based Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army (MNDAA), led at the time by Lin’s father-in-law, Pheung Kya-shin.

Apparently Lin didn’t appreciate his annual denunciation by the US government. “I don’t think I need to defend myself at all. It’s not worth refuting what the United States has alleged about me,” Lin told international reporters during a stage-managed antidrug event held in Mong La in 1999 on the 10th anniversary of his group’s ceasefire with the government. The comments reported by Reuters appear to be one of the few times anyone

from the NDAA has ever spoken to international media.

The official opening of the opium museum coincided with Lin declaring his little kingdom opium-free—a move that appears to have impressed US authorities enough that in 2000, the US State Department described Lin as having “successfully rid his area of opium cultivation.”

Although he was no longer appearing in their annual narcotics reports, US diplomatic cables continued to describe Lin as a “drug trafficker” who oversaw what one embassy official described in 2005 as a “James Bondian private police force.”

Like the NDAA, the UWSA and the MNDAA have also implemented opium bans. The shift away from opium saw all three groups establish large-scale rubber plantations across their respective territories. But not everyone is celebrating. According to a February 2012 report published by the Amsterdam-based Transnational Institute (TNI), these plantations, financed by Chinese government cropsubstitution programs, have benefited Yunnan-based business interests, but pay former opium farmers far less than they could earn in the past.

But if anyone is complaining, Beijing doesn’t seem to be listening: In a report cited by TNI, the Chinese government said it was “a blessing for mankind that Yunnan has helped the 4th Special Zone of Myanmar.”

Apart from working on huge rubber plantations or migrating, farmers who used to grow opium are left with few options. “Development interventions by international NGOs and UN agencies to provide farmers with sustainable, alternative livelihood options to offset the impact of opium bans have been grossly insufficient, and are merely emergency responses to prevent a humanitarian crisis,” write TNI researchers Tom Kramer and Martin Jelsma in an article published shortly after their report was released.

Of course, none of this makes it into Lin’s museum, where unpleasant aspects of the present—like the embarrassing facts of the past—are treated like things sometimes best forgotten.

By BERTIL

By BERTIL

Daw Aung San Suu Kyi shocked many of her supporters and admirers when, in a BBC interview in January of last year, she expressed support for the Tatmadaw, saying: “The truth is that I am very fond of the army, because I always thought of it as my father’s army.”

She also admitted that “there are many who have criticized me for being what they call a poster girl for the army.” But as if to reinforce that impression, last year, on March 27, she attended the Armed Forces Day parade in Naypyitaw and watched soldiers marching in perfect formation past the grandstand where she sat, tanks thundering past, helicopters buzzing and fighting jets flying overhead.

While it is understandable that she does not want to antagonize the military, which is still the key to any fundamental change in Myanmar’s political power structure, her references to “my father’s army” have been questioned by many. Although her father, Aung San, did form the Burma Independence Army (BIA) under Japanese auspices in Bangkok in December 1941, little of that force remained when Myanmar became independent in 1948.

Ironically, there have actually been more veterans from the Second World War in various insurgent organizations than in the government’s army since independence. Almost the entire People’s Volunteer Organization (PVO), a paramilitary force made up of thousands of veterans from the BIA and its successors—the Burma Defense Army, the Burma National Army and the Patriotic Burmese Forces— went underground at independence. Other Myanmar regiments in the government’s army mutinied, formed the Revolutionary Burma Army, or joined the insurgent Communist Party of Burma (CPB). The Kayin battalions went underground as well, while ethnic Kachin units remained loyal to the government—at least for a while.

Of the legendary Thirty Comrades, who went to Japan for military training before the Japanese invasion of Myanmar in 1942, two—Bo La Yaung and Bo Taya—commanded the PVO rebellion. Three—Bo Zeya, Bo Ye Htut and Bo Yan Aung—joined the CPB when the communist insurrection broke out shortly after independence. Of the Thirty Comrades, only Brig. Kyaw Zaw, Gen. Ne Win and Maj. Bo Bala remained in the army in the 1950s. Four of the others—Bo Let

to as “the Fourth Burifs Government.” Number two in the RC, Brig. Aung Gyi, came from this regiment, as did the two other most prominent members of the post-1962 junta, Brigadiers Tin Pe and Kyaw Soe.

More ex-4th Burma riflemen rose to power in the 1970s and 1980s as other officers were gradually weeded out of the top military leadership: U Sein Lwin, who served as president during the stormy events of August 1988; stalwart Col. Aye Ko of the only legally permitted political party from 1962 to 1988, the Burma Socialist Program Party (BSPP); Gen. Kyaw Htin, who served as chief of staff of the army from 1976 to 1985, and defense minister from 1976 to 1988; and U Tun Tin, deputy prime minister and finance minister from 1981 to 1988.

army, i.e., that the military has to play a role in a country’s social and political development, as well as its defense. The Myanmar and Indonesian armies are the only armies in non-communist Asia that have developed their own ideologies.

Today, almost all those who served with the 4th Burifs have passed away, but the legacy remains. Gen. Ne Win created an army that was predominantly Myanmar rather than multi-ethnic—and a financially strong and ideologically motivated military machine over which civilian, or even pseudo-civilian, governments have virtually no control.

Ya, Bo Yan Naing, Bohmu Aung and Bo Setkya—rallied behind the rightwing resistance, which former Prime Minister U Nu organized on the Thai border in the 1960s. And, in late 1976, Brig. Kyaw Zaw, once the most popular commander in the army who had been pushed out by Gen. Ne Win in 1957, went underground and joined the CPB.

On Sept. 6, 1988, nine out of the 11 survivors of the Thirty Comrades denounced Gen. Ne Win and called on the army to join the pro-democracy uprising of that year. Only Brig. Kyaw Zaw, who then was still with the CPB, was unable to join the appeal against their erstwhile comrade-in-arms, Gen. Ne Win. Later, Brig. Kyaw Zaw also expressed his support for the prodemocracy movement.

The power base of the military regime that seized power in 1962 was actually a very narrow one. It consisted mainly of officers from Gen. Ne Win’s old regiment, the 4th Burma Rifles, and nearly all officers who became prominent in the 1960s came from this particular unit. When the Revolutionary Council (RC) was set up in 1962, it was popularly referred

When socialism was discarded after the one-party system was abolished in 1988, the BSPP was renamed the National Unity Party (NUP), with U Tha Gyaw, also a former 4th Burma rifleman, as its first chairman. Even Gen. Ne Win’s personal cook, an ethnic Indian called Raju, had served in the same capacity in the 4th Burma Rifles.

It is fair to say, then, that the economically and politically powerful military machine that emerged in the 1950s and, especially, after 1962, was in terms of organization as well as personalities entirely different from the army that Bogyoke Aung San had founded during World War Two.

Dr. Maung Maung, Myanmar’s official historian during the pre-1988 regime, estimated that there were maybe 2,000 soldiers at Gen. Ne Win’s disposal when he took over as commander-in-chief in 1949, but they were all scattered in decimated, weak battalions and companies. The army that was rebuilt after independence was not Bogyoke Aung San’s army, but Gen. Ne Win’s army, with the 4th Burifs at its core.

In October 1958, officers from across the country met in Meiktila, and, for the first time, the army formulated its own policy. A document entitled “The National Ideology of the Defense Services” strongly resembles the old dwifungsi concept of the Indonesian

Even the 2008 Constitution stipulates that “all the armed forces in the Union shall be under the command of the Defense Services”—making them, in effect, autonomous and not answerable to any non-military authority—and that the Tatmadaw shall also “lead in safeguarding the Union against all internal and external dangers.”

Chapter One of the 2008 Constitution enables “the Defense Services to be able to participate in the National political leadership of the State”—a principle far from that envisaged by Bogyoke Aung San when he led the struggle for independence. In a speech in Yangon on May 23, 1947, he said “the defense of a free Burma is a national responsibility entrusted to the State. The State alone will shoulder this responsibility.” The highest organs of the state, of course, would be the elected Parliament and the government. The 1947 Constitution stated very clearly that “the right to raise and maintain military, naval and air forces is vested exclusively in the Parliament.”

It remains to be seen whether Myanmar can shake off the legacy of the 4th Burifs and the authoritarian system that was introduced by its erstwhile commander, Gen. Ne Win. But let us be very clear: Aung San’s army disintegrated after the Second World War. And the new Tatmadaw that emerged after independence, and, especially, after the 1962 coup, is an entirely different entity.

Maung, official historian during the pre1988 regime, estimated that there were maybe 2,000 soldiers at Gen. Ne Win’s disposal in 1949.

New gas-fired power plants raise hopes that the annual hot-season power drought will soon be a thing of the past

By SIMON LEWIS & KYAW HSU MON / YANGON

By SIMON LEWIS & KYAW HSU MON / YANGON

On the industrial outskirts of Yangon, a rusted chimney exhales wisps of white smoke as a three-decade-old gas-fired power station chunters on.

Just meters away on the same compound in Thaketa Township, a low mumble, but nothing in the way of visible emissions, is coming from a row of 16 boxed-up gasfueled engines—Austrian-produced Jenbacher machines from US firm General Electric.

With new technology like this, there are signs Myanmar is gaining ground in its struggle against the chronic energy crisis that held back its people, and its economy, for years. Less than a quarter of the estimated 60 million population has access to electricity, and those businesses brave enough to set up here despite an unreliable power supply are forced to buy and run their own generators.

The new 50-megawatt power plant is run by Maxpower Thaketa—a local subsidiary of Indonesia-based Navigat.

“You can see that the engine color is green, so you can see we are environmentally friendly,” jokes U Henry Zaw Tun, Maxpower Thaketa’s business development manager, on a visit to the plant in March.

The machines are state of the art. Their vital signs are watched over on a single computer monitor. To catch problems in their workings before they occur, engineers in blue jumpsuits peer at the screen of a small digital camera, which projects an image from an endoscope inside one of the engines’ bowels.

To produce about the same amount of power as the new plant, the old Thaketa plant, a gaspowered turbine generator run by the state-owned Myanmar Electric Power Enterprise, burns twice as much gas, U Henry Zaw Tun says. “And we only use 10,000 gallons of water per year for cooling. They use 300,000 to 400,000 gallons per day!” he says.

With an investment of US$35 million, work was completed in August 2013. In February, Maxpower was rewarded with a powerpurchasing agreement under which the Myanmar government provides the gas and buys back the power produced.

The build-operate-transfer agreement, the specific details of which have not been disclosed, will see the site handed over to the government in 30 years. Earlier reports said the contract was drawn up with the help of the Asian Development Bank (ADB), but it

was in fact drawn up bilaterally with the government, although it meets World Bank standards, according to Maxpower.

In a statement to The Irrawaddy, the company said the contract terms had been approved by President U Thein Sein’s cabinet and that the government planned to use it as a “template for future power projects” as a new generation of power plants arrives.

Yangon currently sucks up about half of the country’s total supply of about 1,850 MW of energy, and demand in the former capital is met by a mixture of hydropower and existing gas generation. In the hot and dry months from March to July, however, demand is driven up by airconditioners, and supply is shorter as lower water levels mean hydropower can contribute less energy to the grid.

While the government in the long run is looking to exploit the country’s huge river network for more

hydropower to fuel development, those projects are politically sensitive and take a long time to get online. Two years ago, when the hot season caused widespread blackouts in the country’s commercial capital— sparking candle-lit demonstrations— the government put out an open invitation for companies to come forward with fast-track solutions to meet fast-rising energy demand.

Alongside the new Thaketa plant, a new 240-MW gas plant is about to begin producing power at Ywama, with turbines donated by the Thai government.

According to Yangon’s state-run provider, the Yangon Electricity Supply Board (YESB), gas generators—one at Ywama in Insein Township, one run by ToyoThai Corporation Plc in Ahlone, and another at Hlawga in Mingaladon—

are at present producing about 230 MW of power combined. Nationwide, gas accounts for about 550 MW, compared to 930 MW from hydropower, according to the YESB.

But gas is set to contribute more to Myanmar’s energy mix, especially as the amount of gas coming onshore increases.

Although existing projects controversially send the majority of the gas extracted from Myanmar’s seabed abroad, a proportion stays in Myanmar. The government has promised to keep more of the gas from future developments for domestic use.

The Yangon gas generators are being fueled by Total’s Yadana project in the Andaman Sea. The Shwe field in the Bay of Bengal is also now sending gas ashore, and the Zawtika field, developed by Thailand’s PTTEP, was expected to start producing this hot season.

The World Bank is funding the upgrade of an aging gas power plant in Thaton, Mon State, which is expected to reach 106 MW. Also in Mon State, Singaporean company Asiatech Energy has announced it has secured funding for a 230-MW gas-fired plant in the state capital,

Mawlamyine, to be completed in late 2015.

Also on the horizon is a shortterm power-supply project that will see Florida-based company APR Energy install a 100-MW gaspowered plant in Kyaukse, Mandalay Region, to burn gas from the Shwe project. The company lauded its deal to bring a “turn-key” power plant—beginning sometime between April and June and running to late 2015—as a “bridging solution for the medium term while the country develops its long-term power generation infrastructure.”

Both APR and Maxpower told The Irrawaddy they were looking to take on more power supply projects in Myanmar.

“We would like to invest further in Myanmar,” said Clive Turton, APR Energy’s head of business development for the Asia-Pacific region, declining to give details of “several” other projects the company was looking at.

Demand for power is rising nationwide by 12 percent per year, said Mr. Turton, who said he believes natural gas will be an important tool as the country’s energy demand grows.

“I absolutely think [natural gas] should be a major part of the solution,” said Mr. Turton.

Alongside natural gas developments, the government has numerous hydropower and coal plans, but it is a challenging task to meet rising demand, which could reach 5,000 MW by 2020, according to a 2012 energy sector assessment conducted by the ADB.

U Maung Maung Latt, the vice chairman of YESB, said that despite an expected annual increase in demand of 15 percent, the city would not this year see the rolling power cuts residents are used to. As of early March, infrequent power cuts had begun in downtown Yangon, but not on the scale seen in previous years.

“This summer, both the production rate and the consumption rate will be up in Yangon. Normally consumption is about 800 MW, but in this dry season it could rise to 1,000 MW in Yangon alone,” he said. “But the recent situation is that production and consumption are balancing.”

Unsurprisingly, given the protests of the past, YESB makes sure residential power demand is met before sending power out to industrial zones. U Maung Maung Latt was hopeful, however, that the city’s factory districts would see some benefit from the city’s newly bolstered power supply.

“For certain, it won’t go back to zero hours of power for industrial zones, like last year,” he said. “I can say this year there will be more electricity not only in residential areas, but also in industrial zones. We are receiving more power from gas turbines and dams are saving water through new technology. Also, we’re upgrading the national grid and other related power lines.”

He said industrial zones would get at least 18 hours of power a day—with power cuts timed during the peak evening hours. That is good news for manufacturers, whose alternative is to run diesel generators.

U Myat Thin Aung, the chairman of Hlaing Tharyar Industrial Zone, which houses almost 600 factories in western Yangon, said using generators was more than four times as expensive as the state-subsidized power from the grid—costing just 75 kyat ($0.08) per kilowatt hour.

When cheap power is not available, some factories simply close their doors, he said. “If production costs increase, sales profits go down. Eventually, factories have to shut.”

Hlaing Tharyar is one of 20 mostly small industrial zones in Yangon that altogether demand about 165 MW of power.

Myanmar’s planned large special economic zone projects in Thilawa, Dawei and Kyaukphyu will have their own off-grid power sources. U Myat Thin Aung said some factories were keen to run their own gasfired power generation, but the government had not come forward with a reliable source of cheap gas for this.

The country’s low-cost labor partly offsets the high cost of powering a factory and other

infrastructure bottlenecks. Investment in simple, labor-intensive garment factories is reportedly rising, with investment coming from China, Taiwan and Hong Kong. But investment in heavy industry is yet to take off.

“The electricity shortage in Myanmar is one of the biggest challenges for foreign heavy industry to invest here,” said U Myat Thin Aung. “[Heavy industry investment] will stay away as long as the government can’t supply enough electricity for local industrial zones.”

Since Western countries began embracing Myanmar and its reformist government, the country’s power shortage—in the face of abundant resources—has become a favorite cause for foreign donors.

In January, the visiting World Bank President Jim Yong Kim pledged $1 billion in aid and investment over a number of years to help expand electricity provision. Japan’s international aid agency, JICA, is developing a nationwide master plan for power in Myanmar.

“All the development agencies spent the large part of 2013 talking to the government about areas of support. They have divided up all the areas that the government asked for help with,” said Grant Hauber, the ADB’s principal public-private partnership specialist for the AsiaPacific region.

Donors were setting up as many as 25 projects on power in Myanmar as part of a “divide and conquer” approach to tackling the numerous problems in the power sector, he said.

“A lot of the projects are going to be implemented simultaneously so there will be a fairly significant uptick in grid capacity,” he added.

There is also work underway by the ADB and others on improving the national grid to reduce power losses, and to upgrade the national grid’s “backbone” to a 500-kilovolt line that can transfer power without losses between Myanmar’s north—where the larger hydropower projects will be—and the south—where thermal generation is planned.

This work “will reduce power losses by tens of megawatts,” said Mr. Hauber. “It’s like getting a new power plant.”

angon is a city abuzz with economic activity, as the world rediscovers one of the region’s most promising frontier markets after decades of isolation. With this, however, comes a growing housing crisis, as the city seeks to accommodate its rapidly expanding labor force.

Government plans to build 30,000 new low-cost public housing units next year may bring some relief, but the real answer, argues Taw Win Family Construction Chairman U Ko Ko Htwe, is private-sector investment. In this interview with The Irrawaddy’s Kyaw Hsu Mon, one of the country’s top property developers outlines the challenges facing his industry, and discusses how the government could make it easier to turn Yangon into a city of homeowners.

What are the most pressing problems for the construction sector in Yangon right now?

The biggest one is that we lack the latest technology, although that is improving. Still, we can’t compare with what foreign investors have at their disposal. Besides this, we face a shortage of human resources. In the past, a lot of technicians left the country because they could make more money overseas, and even now that the country is opening up, they’re in no hurry to come back. Because the demand for skilled workers outstrips the supply, the cost of labor is more than we can afford.

The price of land is also a huge problem. Prices here are almost the same as Singapore, but very few people can afford to pay them. Building materials are also expensive here, so we can’t use the best quality.

Finally, I would say that there is a great deal of inefficiency here, due to the way the economy is run. We end up wasting time, wasting money and wasting materials because of this. Interest rates are also too high—I believe Myanmar’s rates are the highest among the Asean countries.

Why do you think interest rates are so high?

The problem is with the thinking of key people at the Central Bank. Even though the president has made the bank independent of the Ministry of Finance, it still has the same governor. Because he doesn’t really understand the nature of business or the financial system, nothing has really changed.

Local businesses have recently called on the Central Bank to reduce interest rates from their current level (13 percent) within a year. How did the bank respond?

We—local businessmen—made that proposal at a meeting with the president on Feb. 22. It’s not just the construction sector that wants this to happen, it’s almost everyone. Foreign banks are starting to come to Myanmar, and they can offer loans at much lower rates, and charge smaller transaction fees. But it’s up to the Central Bank to control the country’s financial situation. Unless it does, the economy will suffer.

It’s important to get the country’s capital in circulation. Unless the financial system is working properly, that won’t happen. The Central Bank also has to manage the floating exchange rate. If the bank isn’t able to do these things, and can’t make flexible interest rates for us, we don’t

dare make a move, even though the country is opening up.

Yangon’s population is growing fast. How many new residential units need to be built to keep up with this growth?

We won’t really know the population until the census is completed, and in terms of demand, these days we are seeing some people who are buying two or more properties. That makes it difficult to calculate how many new units we can build. Generally, the supply of condominiums and the demand are balanced. The problem

is that while there are some people out there who can buy, there are lots of others who can’t. People on lower incomes are struggling just to pay rent. That’s why developers need to build more low-cost housing, as a kind of poverty reduction. I’m sure that if we built 100,000 low-cost units, we could easily sell them all.

How can you be sure that they would be bought by their intended market, and not by speculators?

Well, last year, we sold out more than 3,000 low-cost units for 16.5 million kyat (US$16,500) each, and

now they’re selling for 70 million kyat ($70,000). The trouble is we can’t control the prices once we’ve sold the properties. Sometimes it’s the consumers themselves who are playing the market. If we could build a lot more of these units, that wouldn’t happen. But that would take a lot of developers building affordable housing, not just me. If the government gave us access to some of the available land (there’s lots of it) we could build enough housing for 10 million people.

Which areas do you have in mind?

You don’t even have to go as far as North

rate, and to free

or South Dagon or Hlaing Tharyar to find suitable land. Within Mingaladon, Insein, Mayangone, South and North Okkalapa, Thaketa, Bahan, Hlaing and Kamaryut townships, there’s lots of space left in Yangon.

So you’re saying that there is still a lot of space for developers to work in, within the area administered by the Yangon City Development Committee?

Yes, even if we work within this area, we could build enough housing for 10 million people. All we need is better city planning.

Above: A shortage of low-cost housing and poor living conditions in the current housing stock are among the challenges Yangon faces as it develops. Left: “If the government asked me to build 20,000 units right now, I could do it,” says U Ko Ko Htwe.

Why haven’t other developers shown much interest in low-cost housing? Is it because it doesn’t make much of a profit?

With better management, the right technical resources and goodwill, it would work. If the government asked me to build 20,000 units right now, I could do it, because I already have a system for building low-cost housing. With five more people like me, we could create a lively market.

So what would the government have to do to make it happen?

Well, the government controls a lot of vacant land, including land owned by the regional government and the army. If it freed up that land, it would benefit everyone. Even if the profit was just 300,000 kyat ($300) per unit, with 20,000 units, that would come to 6 billion kyat ($6 million). Of that amount, about 1.5 billion kyat ($1.5 million) would go back to the government in taxes.

How many units have you already built in Yangon?

We built 1,600 units at the first Mudita

housing project in Thamine and 1,700 in Insein Township, so a total of 3,300 units. We’re not sure about starting a third project, because we need a big space to build a low-cost housing project, about 30 or 40 acres. That would include a hospital, school and other facilities, too.

If the government made the land available, we could pay the normal price. We wouldn’t expect to get it for nothing. I would build nine-story buildings with elevators. Each unit would be 600 square feet, with two rooms.

What about the issue of squatters in Yangon? How do you think this problem can be solved?

As I said before, if the government gave developers access to land, we could create very low-cost housing for them. They could buy new homes on installment plans, which they could pay off in five to 10 years. We could sell them for 4.4 million kyat ($4,400) per unit. If the government offered subsidies, it could be theirs in five years if they pay just 50,000 kyat ($50) a month. If not, they can have their own home in Yangon after just 10 years.

as logs before, but not anymore. So, businessmen there have no choice but to come and do business inside our country,” he told The Irrawaddy.

Myanmar is one of the last countries in the world that still allows for the export of unprocessed logs, and raw timber makes up the majority of its wood export. As a result, the country has failed to build up a wood-processing industry that can add value to the vast quantity of timber that Myanmar produces.

In an effort to reduce deforestation and the outflow of unprocessed timber, the government has banned the export of raw logs from April 1 and only sawn wood is allowed to be exported.

By THIT NAY MOE / YANGON

By THIT NAY MOE / YANGON

Foreign investment in Myanmar’s timber industry reached US$51 million last year, with six Indian projects accounting for more than half of the total, government figures show.

According to statistics from the Directorate of Investment and Company Administration, which is under the Ministry of National Planning and Economic Development, eight timberprocessing licenses were granted to foreign firms in the fiscal year 2013-

14, of which India had acquired five, Singapore two and Korea one.

The figures indicate that India invested $26.04 million in the industry, while Singapore and South Korea invested $24.26 million and $0.93 million, respectively.

Minister of Environmental Conservation and Forestry U Win Htun said that Myanmar’s log export ban had prompted an increase in foreign investment in timber processing.

“We usually exported wood to India

India, China and Thailand are the biggest importers of Myanmar timber, which is estimated to have a total worth of more than $1 billion per year, according to US-based research group Forest Trends, which estimates that about half of all timber is exported to India.

Myanmar’s timber industry has long been dogged by unsustainable practices and corruption, and is largely controlled by tycoons with connections to the former military regime. The unregulated cross-border timber trade to southern China passes through conflict-torn northern Myanmar and is being taxed by ethnic insurgent groups and units of the Myanmar military.

Consequently, Myanmar has suffered from high rates of deforestation, while a recent increase in agro-industry investment—such as rubber and palm oil plantations—is driving further forest losses, Forest Trends has warned.

Last year, the European Union lifted trade restrictions on Myanmar, but the country would need to reform its timber sector in order to gain access to the EU export market.

Myanmar’s government has shown an interest in such reforms and is in discussions with the EU about the joint implementation of a Forest Law Enforcement Governance and Trade action plan.

The Myanmar Timber Association, a government body in charge of regulating the timber industry, has said that an increase in trade in high-quality timber with the EU would be a boon for Myanmar’s timber industry.

As the ban on exporting raw timber goes into effect this month, India has emerged as the largest investor in the processing industryLogs are piled up at Thilawa port in 2013 awaiting shipment abroad. PHOTO: JPAING / THE IRRAWADDY

The hot season has well and truly arrived, and while many are sweating it out as a result, it’s good news for makers of the famed Patheinhtee (Pathein parasol), who are reaping the benefits of high demand from shadeseekers.

The parasols of Pathein, the capital city of Ayeyarwady Region, are an internationally recognized part of Myanmar’s iconography. It is an industry, made up primarily of smallscale workshops, that has been turning out the colorful creations for more than 100 years.

U Thein Oo, owner of the Nay Nat Thar Pathein Htee workshop in Pathein, said demand this summer, as in years past, has risen significantly. At his homebased factory, employees can produce 250 parasols per day, and the enterprise has been selling out its stock nearly every day as temperatures have climbed. Prior to the summer season, his workers produced less than 200 parasols per day.

“We’re distributing to all cities nationwide, especially in Mandalay, Bago and Mawlamyine,” he said.

Using a division of labor process, each step in the production of Pathein parasols is assigned to an individual. Most parts, except for the wooden finials that are set atop the parasols’ canopies, are handmade.

U Thein Oo said that in the past, the parasols’ canopies were made from paper, but over the years the Pathein craftsmen have flexed their creative muscles, and now produce parasols with canopies of cotton, silk and satin as well,

wall hangings or lampshades.

In the production process, the parasol’s main shaft is made of a wood known as ma u shwe war . The ribs and stretchers are made from a type of bamboo called taragu, which grows around Pathein city.

“All parts of the parasol are from around the Pathein area, except silk and cotton canopies, which are bought from Yangon,” U Thein Oo said.

“There are three sizes we’re producing right now: The biggest one is for garden use, and two [smaller] sizes are for ladies’ use,” he said.

U Thein Oo’s business employs 15 workers, some of whom operate rudimentary machinery used for some of the woodwork.

U Maung Kyi, a craftsman in the workshop, said that he earns just 8 kyat (less than 1 US cent) for each wooden finial that he produces. In an average day, he says, he makes about 100 finials.

Workers bind the main shaft, ribs and stretchers together, and stretch the parasol’s canopy across this frame.

In the last steps, the cloth is dyed and coated with tayae (natural fruit juices) to help the canopy maintain its vibrant coloring. Workers varnish and polish the wood before leaving the parasols to dry in the sun. The painting of designs on the cloth serves as the final touch on a Pathein parasol.

After attaching the canopy to the wooden frame, the parasol undergoes strength testing to ensure its durability.

in attractive floral-pattern designs.

“In the past, we used a paper that was made in Shan State. Now, we’ve created new silk and cotton canopies. We dye them to be colorful and then glue them to make them stronger and more attractive to customers,” he said.

These re-envisioned Pathein parasols have helped fuel sales among local buyers, who are largely women. Pathein parasols are also highly sought after by the growing number foreign visitors, who purchase them as souvenirs, or for interior decoration as

“We’re distributing at 2,000 kyat [$2] for a large ladies’ use parasol as a wholesale price, but in retail shops, prices are almost double,” U Thein Oo said. The production cost of a parasol is 1,000 to 1,200 kyat, depending on the size.

Although Pathein parasols have traditionally been known for their practical purpose and as a fashion accessory, they are increasingly deployed to serve decorative purposes in home interiors, gardens, hotels and restaurants.

“It bothered me,” said U Myint Zaw, managing director of the Mahar Shwe Yadanar Myay Company, after his palm oil importing company was one of 2,500 firms mistakenly named by the government as tax evaders.

The Internal Revenue Department (IRD) on March 6 published a list of 10,670 companies that it said had failed to pay taxes for the 2012-13 fiscal year, which ended in March 2013. But after receiving many complaints from companies wrongly included on the list, a new list was posted that included only 8,220 companies.

Among the wrongly identified tax evaders were AGD Bank, Yoma Bank, the Small & Medium Industrial Development Bank, A-1 Garment Company, Korea Development Bank, the Dagon Group of Companies, Ayeyar Hinthar Trading Company and Mahar Shwe Yadanar Myay Company.

U Myint Zaw said the IRD had quickly responded to the company’s complaint about being wrongly named, but said the department’s mistake could cause misunderstandings among the company’s shareholders and management.

Myanmar’s government is making the country more attractive to foreign businesses but the improvement and enforcement of regulations which reassure investors is “slow and lacks sufficient transparency,” a study said.

The country’s adoption of the international Convention on the Recognition and Enforcement of Foreign Arbitral Awards is a positive step, but fitting it into Myanmar’s “complex and ill-developed legal framework will be a major challenge,” said the January-March Country Risk Report by UK business analysts Maplecroft.

“Investors will find that the business environment is skewed in favor of local conglomerates such as the Myanmar Economic Corporation,” the study said. “These businesses have strong ties to the military, and have a dominant market position in sectors ranging from fuel distribution to real estate.”

It also warned that foreign investors partnering local businesses “face very high risks of corruption and mismanagement.”

However, on the positive side Maplecroft said there was little risk of the state nationalizing investor assets. -William Boot

“We have never failed to pay taxes every year. IRD should be more careful in future,” he said.

U Tin Htun Naing of the IRD said, “We released the list with the good intention of collecting overdue taxes, but that the list was incorrect was a shock to us all. We admit our error and apologize for that.” -San Yamin Aung

Yoma Strategic Holdings Ltd plans to set up what it says could become the biggest coffee plantation in Myanmar, hoping the frontier economy has the potential to develop a strong coffee industry.

The Myanmar-focused property conglomerate, led by chairman U Serge Pun, said in March it has signed a deal to set up a joint venture to establish a coffee business with ED&F Man, a global agricultural trader, according to Reuters.

Yoma will hold an 85 percent stake in the venture, which is expected to require up to US$20 million of investment over four years, the agency reported. Its target will be to plant 3,700 acres of coffee.

Myanmar is geographically well situated to become a coffee producer, though its coffee industry is in its early days, with a number of small plantations.

In 2012, it produced about 8,000 tons of coffee beans on 12,000 hectares (29,652 acres) of land, according to estimates of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. In 2011, the country exported under 100 tons of coffee.

Yoma also announced it had signed an agreement with the Myanmar government to set up a dairy plant to supply milk to schoolchildren, as well as a cold storage and logistics business with Japan’s Kokubu & Co., Ltd.

-Reuters

Japanese retailer Aeon Group is reportedly planning to promote its Topvalu and Jusco brand products in Myanmar.

Aeon will open offices in Yangon soon as part of investment plans to develop retail outlets in the country, according to the Japanese news agency Kyodo.

Aeon has been expanding in Southeast Asia and now operates shopping malls in Vietnam, Malaysia and Thailand, and is planning ventures in Indonesia and Cambodia.

Aeon plans that its new office in Yangon will “lay the groundwork for launching a shopping mall in the country’s former capital and largest city by 2016,” said Kyodo.

The Myanmar Investment Commission expects that foreign direct investment will reach between US$4 billion and $5 billion in the coming 2014-15 fiscal year, with the telecommunications sector seen as a rising star.

U Aung Naing Oo, directorgeneral of the Directorate of Investment and Company Administration and a member of the Myanmar Investment Commission (MIC), said that the telecoms sector offered significant potential for foreign investment in the coming year.

“[Telcoms companies] Telenor and Ooredoo have received licenses as service providers, but they can’t implement everything themselves. We need other companies that can help their projects—for example, building fiber optic lines and towers around the nation—so we expect that some related

foreign companies that can help them will be coming in the next year,” he said.

“I do expect that a full 20 percent of foreign investment will go to the telecoms sector this year, [and] more in the year after. It may become the number one investment in Myanmar.”

According to MIC figures, the top draw for FDI was the country’s laborintensive manufacturing sector, at $1.7 billion accounting for nearly half of the total $3.5 billion invested so far in the 2013-14 financial year. -Kyaw Hsu Mon

At a recent event to mark the first anniversary of a landmark peace dialogue in Thailand’s troubled south, the mood was more uncertain than celebratory. The conflicting views of the main parties at the talks—the National Security Council (NSC), heading the Thai government’s delegation, and exiled members of the Barisan Revolusi Nasional-Coordinate (BRN-C), speaking on behalf of the strongest Malay-Muslim insurgent movement in Thailand’s southernmost provinces—were one obvious source of this unease. But beyond this, there were also worries rooted in the attitude of Thailand’s powerful military toward such a dialogue.

The words of Maj.-Gen. Nakrob Boonbuathong, a ranking member of the Internal Security Operation Command (ISOC), an influential branch of the military, went some way toward allaying these concerns. “The security community supports the peace process and for the dialogue to find a solution,” he told a panel discussion held in a packed lecture room at Pattani’s Prince of Songkhla University.

Such words from a general known to be a hawk were not lost on analysts of the insurgency that has bloodied the provinces of Pattani, Yala and Narathiwat, home to predominantly Buddhist Thailand’s largest minority, the Malay-Muslims. “It is a good

sign, at least verbally,” remarked one Pattani-based analyst. “The military seems to have accepted that this process will go ahead and it wants to have a role.”

Yet, even such analysts prefer to be guarded, given the military’s dominant role in combatting the BRN-C-led insurgency and the sway it enjoyed during four previous efforts at peace talks since this latest cycle of violence erupted in January 2004. The latest talks have exposed the manner in which the military has wrested control from other arms of the Thai state to determine the political agenda in this region along the Thai-Malaysian border, making the question of whether it is on board with the current peace process the focus of much fraught speculation.

The turf war over who sets the agenda in the south has come increasingly out into the open since the signing of the “General Consensus on the Peace Dialogue Process” on Feb. 28, 2013, between Lt.-Gen. Paradorn Pattanatabut, head of the NSC, and Hassan Taib, an exiled political representative of the BRN-C. According to Rungrawee Chalermsripinyorat, the author of reports about the insurgency for the Brussels-based International Crisis Group from 20082012, “The military sent a message to the government not to sign the Feb. 28 ‘General Consensus’ with the

BRN-C. Gen. Nakrob often said that the army was being kept at a distance by Paradorn and [other allies] of the government.”

The extent of this tussle was

exposed by a security establishment insider nearly two months after the pact for talks was signed. His timing lent weight to his words, coming as they did just before Paradorn and Taib met for the second round in Kuala Lumpur in April of last year.

In an interview with a local newspaper, Thawil Pliensri, Paradorn’s predecessor, decried the lack of a consensus among Thai state actors that matter— the NSC, the Foreign Ministry, the National Intelligence Agency, ISOC, the Justice Ministry and the armed forces.

“All state organizations must be united and adopt the same stance before negotiations,” he said. “We have seen that [the] insurgents have made demands about prosecutions

That questions over the military’s willingness to sustain Prime Minister Yingluck Shinawatra’s peace gambit still continue is hardly surprising. It was marginalized by Yingluck’s elder brother, former Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra, who, despite living in self-imposed exile after his elected government was overthrown in a September 2006 military coup, continues to advise his sibling from abroad. For peace in the south, the elder Shinawatra turned to his allies within the civilian arm of the security establishment and the police to launch the peace dialogue with the BRN-C. This move challenged the military’s preeminent political role in solving the ethno-nationalist conflict in the south.

BRN-C was elevated to the status of equality with Bangkok. That dealt a blow to a goal long held by the hawks in the military: to deny the BRN-C or other Malay-Muslim insurgent groups the status of equality with the Thai government. The latter strategy had resulted in the military dealing with the militants in “informal dialogues,” often with the aim of reducing violence being a key driver.

Equally significant was the Thai government’s public affirmation in the February 2013 pact as to who its armed forces was locked in a battle with, and who Bangkok should negotiate with: the BRN-C, a well-armed insurgent movement that had a political agenda. This broke the wall of silence that the military had maintained to determine the nature of the conflict that, currently, has accounted for 6,000 deaths and 10,700 people injured.

“The past year has offered clear evidence of the existence of a MalayMuslim rebel movement,” a Bangkokbased diplomat told The Irrawaddy. “The narrative of the conflict that the army controlled—about attacks by ninjas, drug networks, criminal groups and unknown militants—has been blown apart.”

Such a turn of events marks a rare institutional setback for the most powerful pillar of the Thai state. The military’s influence here is not limited to protecting this Kingdom’s international boundaries and being on hand when national security is threatened. It also wields power in shaping Thailand’s foreign policy towards neighboring Myanmar, Laos, Cambodia and Malaysia.

and arrest warrants but Army Chief Gen. Prayuth Chan-ocha has dismissed them. This reflects disunity on our side. Such an issue rattles the confidence of negotiators.”

Two significant benchmarks emerged after Paradorn met the goateesporting Hassan in Malaysia, chosen to fill the role of an international facilitator. The first was that the

“Thailand lacks civilian control over its armed forces. During the Cold War, the military became the strongest political institution in Thai politics,” said Thitinan Pongsudhirak, director of the Institute of Security and International Studies at Bangkok’s Chulalongkorn University. “The friction between the military and elected governments is entrenched. Because democratic institutions are weak, the military in recent years has assertively retaken policy reins in key areas, particularly border conflicts and the Malay-Muslim insurgency.”

As Myanmar gears up for this year’s Thingyan festivities, some lament that traditional celebrations are being drowned out by raucous revelry

By NYEIN NYEIN / YANGON

By NYEIN NYEIN / YANGON