Recalculating Myanmar and Thailand

History: The ‘Broom’ That Saved Yangon

Festive February in Mandalay

French Food in a Fabulous Setting

Recalculating Myanmar and Thailand

History: The ‘Broom’ That Saved Yangon

Festive February in Mandalay

French Food in a Fabulous Setting

February 2014

FEATURE: HPAKANT’S DEADLY DESCENT

BUSINESS: BANKING OUTLOOK

TRAVEL: TREKKING TO INLE

The Irrawaddy magazine has covered Myanmar, its neighbors and Southeast Asia since 1993.

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF: Aung Zaw

EDITOR (English Edition): Kyaw Zwa Moe

ASSOCIATE EDITOR: Sandy Barron

COPY DESK: Neil Lawrence, Paul Vrieze, Samantha Michaels, Andrew D. Kaspar, Simon Lewis

CONTRIBUTORS to this issue: Aung Zaw; Marwaan Macan-Markar; Saw Yan Naing; Bertil Lintner; Paul Vrieze; Kyaw Hsu Mon; David I.Steinberg; Simon Lewis; Simon Roughneen; Kyaw Phyo Tha; Virginia Henderson; Kavi Chongkittavorn; William Boot

PHOTOGRAPHERS: JPaing; Steve Tickner; Sai Zaw; Teza Hlaing

LAYOUT DESIGNER: Banjong Banriankit

SENIOR MANAGER: Win Thu (Regional Office)

MANAGER: Phyo Thu Htet (Yangon Bureau)

REGIONAL HEADQUARTERS MAILING ADDRESS: The Irrawaddy, P.O. Box 242, CMU Post Office, Chiang Mai 50200, Thailand.

YANGON BUREAU : No. 197, 2nd Floor, 32nd Street (Upper Block), Pabedan Township, Yangon, Myanmar. TEL: 01 388521, 01 389762

EMAIL: editors@irrawaddy.org

SALES&ADVERTISING: advertising@irrawaddy.org

SUBSCRIPTIONS: subscriptions@irrawaddy.org

PRINTER: Chotana Printing (Chiang Mai, Thailand)

PUBLISHER LICENSE : 13215047701213

16 | Society: The ‘Broom’ that Saved Yangon

A key player in a decisive battle that changed the course of Myanmar’s history recalls his role and reflects on what might have happened

18 |

Special Report: From Jade Land to a Wasteland

Two decades of “peace” in Hpakant have reduced it to an environmental and social disaster area

24 | Profile: After a ‘Family Coup,’ a Reporter Earns Her Own Greatness

Myanmar’s best-known female journalist proves she’s her father’s daughter—and more

26 |

Feature: A Tribute to Maung Thaw Ka

Remembering one of the heroes of Myanmar’s democracy movement, who died a political prisoner—and a true patriot

28 |

COVER Dawei Awaits Its Destiny

The planned mega-project in the far south has stalled, but many residents in the region still fear what’s coming

36 | Real Estate: Out of Reach

The widening chasm between supply and demand has sent real estate prices in Yangon soaring to new heights

38 |

Interview: Banking on Myanmar’s Future

42 |

Economy: Where the Dealmakers Meet

A glut of conferences will give plenty of opportunity for would-be investors to rub shoulders with local business people and officials

44 |

Roundup: Secret Deal to Build Hydro Dams in Kachin State Revealed

For decades, Myanmar’s struggle against HIV/AIDS was held back by the former junta’s reluctance to acknowledge the scale of the crisis facing the country. As a leading expert on the disease since the 1990s, Dr. Chris Beyrer of the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, in the US city of Baltimore, has long been at the forefront of efforts to raise the alarm in Myanmar, which he warned in 2005 faced an explosion of HIV comparable to that of the worst-hit parts of Africa.

Dr. Beyrer recently spoke with reporter Marwaan Macan-Markar about the current state of Myanmar’s HIV crisis in the wake of recent political reforms. Although many things have improved, he says, the country still has vast unmet health-care needs, with 220,000 people living with HIV and only around half of the estimated 120,000 patients requiring anti-retroviral (ARV) therapy receiving it—and most of those in Yangon and Mandalay, the two largest cities.

Still, says Dr. Beyrer, the country’s newfound openness could have a dramatic impact on how well it can contain the spread of the deadly disease. But, he adds, much remains to be learned about how deeply rural regions have been affected by decades of neglect.

volume of increased funding and increased treatment. This is going to be a real challenge.

The backbone of the public health system in Myanmar is midwives and nurses, particularly in rural areas. There will have to be a lot of what is called “task shifting,” with many more healthcare workers being able to support people with HIV.

What shift in policies is required to make the access to 50,000 new treatment slots for people with HIV meaningful?

Until now, the government’s treatment program had been accessible to people with HIV when it is very late. The levels of the CD4 [the white blood cell that targets the virus] count calculations had been so low that people have full-blown AIDS before they are started on therapy. And that is not good. It is much better to start earlier, when their immune system could recover and they can benefit from the treatment. And that is what MSF [humanitarian aid organization Médecins Sans Frontières] was trying to do during all these years, since it has been a major treatment player. About half the people being treated were treated through MSF.

It is now nearly three years since President U Thein Sein paved the way for political liberalization in Myanmar. Has this opening made a difference to the tens of thousands of people living with HIV and those vulnerable to being infected in the country?

There is much more freedom of information now. And I think the single biggest change has been the end of censorship and the opening the media for greater and more open discussions. That, of course, has very great implications for HIV and the people with HIV. It has also marked the end of isolation for HIV professionals,

and there has been a large increase in international donor engagement. And what we understand is there will be 50,000 new treatment slots in the pipeline [for people with HIV to gain access to ARVs].

How are the country’s public health professionals coping with this shift?

What the people in the Health Ministry and in the national AIDS program say is that, earlier, they were waiting for resources to come, but now that they are coming, there is a big challenge to strengthen the absorptive capacity. They have to be able to handle that

But even this expansion of treatment and care seems to be concentrated in urban areas, as before. How worrying is it that HIV-related care is still limited in large stretches of the country, in ethnic areas shattered by conflicts?

[The problem is] not just in the conflict zones, but also in the less medically served rural areas, where we still do not have a good handle on what the HIV prevalence rate is. For example, if you look at India, the states with the highest HIV rates are Nagaland and Manipur [on the MyanmarIndia border]. And if you look at the [Myanmar] side of Nagaland, there is no HIV care program. And we know that if it is high on the Indian side, it

is certainly as high on the [Myanmar] side. There is no treatment capacity there, no laboratory capacity, so you know there are whole parts of the country that have not been reached for HIV testing.

So I think one of the things we hope for in this new period of openness and transparency, and as the medical information and health system improves, is that we will start to get a better assessment of HIV prevalence rates. I don’t think anybody knows what the exact figure is. But what they are reporting now is a low prevalence rate.

The HIV prevalence rates were a very politically sensitive issue

when the country was under the junta. What was it like for your contacts in the Health Ministry during military rule?

It was terrible for them. They were isolated. They knew the country had a very severe epidemic, but people in the ministry were under pressure. A very senior official in the ministry told me he was once ordered by a general to lower the HIV rates, because [Myanmar] had to have a lower infection rate than Cambodia.

What year was that?

It could have been either 2003, ’04 or ’05.

How about you? Your research on HIV was also not well received by the military regime.

Yes. We had done an assessment of the epidemic in 2000, and our estimates were vigorously attacked by the government. And then, since the political liberalization, one of the people involved in that attack came to see me in Baltimore—he came to my office out of the blue. I didn’t know who he was, but he said he was visiting the US as a scholar. And he came to apologize. He told me he was sorry and that I was right, but they had been ordered to attack me. It was nice to be right, but it didn’t help all those people with HIV in the country.

PHOTO: COURTESY JEANNE HALLACYMind your step.

—Sally Thompson of the Thailand Border Consortium, speaking about recent fires at camps for refugees along the Thailand-Myanmar border and refugees’ fears that they are being pressured to return to Myanmar.

Kyaw Tin Aung of the United Karenni State Youth group, commenting in mid-January on the lack of success of opium eradication measures in Kayah State.

—US Ambassador to Myanmar Derek Mitchell, commenting in January on Article 59 of the 2008 Constitution, which states that a president’s spouse or children cannot be citizens of a foreign country.

‘‘This provision, this fear, seems a relic of the past.”

“People here make more money from opium. That’s why they have focused on it.”

“When you get things like the fire, the reduction in services… it puts pressure and anxiety on refugees.”

Myanmar’s leading student activist group staged a sit-in in central Yangon on Jan. 5 to demand that the government abolish and amend restrictive laws, including

those that make it difficult to organize protests. It was the first time since leaders of the 88 Generation students group were released from prison in early 2012

that they had organized such a large public demonstration. At least a thousand protesters, including members of Parliament, students, farmers and leaders of civil society organizations, gathered near Sule Pagoda for the protest. However, the Ministry for Home Affairs rejected calls to amend the country’s Peaceful Assembly Law, under which government permission must be granted before protests can be held. A day earlier, a separate protest called on lawmakers to amend provisions in the Constitution that currently prevent opposition leader Daw Aung San Suu Kyi from becoming president.

her calls to amend the Constitution, which bars her from becoming president because she has two foreignborn sons. She stayed in the region from Jan 6-10, attracting huge crowds in a demonstration of her enduring popularity there despite her long absence. The last time she visited this corner of the country, she narrowly escaped an attack by pro-junta thugs who killed as many as 70 of her supporters in an incident known as the Depayin massacre.

at the Ban Mai Nai Soi camp in Mae Hong Son Province. According to the UN refugee agency UNHCR, a total of 165 homes were destroyed. Another fire in March of last year at Ban Mae Surin camp, also in Mae Hong Son, killed over 30 people and left 2,000 homeless.

A refugee puts out a fire at the Mae La refugee camp in Thailand on Dec. 27, 2013.

Two year-end fires at camps for Myanmar refugees in Thailand left one person dead and directly affected more than 850 others, according to aid agencies. The first blaze broke out on Dec. 27 at the Mae La camp in Tak Province, which houses more than 40,000 refugees, making it the largest of nine officially recognized camps in Thailand. The second fire occurred the following day

The South Korean government is planning to erect a monument to the victims of a bombing carried out by North Korean agents in Myanmar more than 30 years ago, according to Chosen Ilbo, a Seoulbased daily. The monument, commemorating the murder of 21 people, including three senior South Korean politicians and three

Myanmar journalists, will be erected at the Aung San National Cemetery sometime within the next three months, the newspaper said. On Oct. 9, 1983, a bomb targeting South Korean President Chun Doo-hwan exploded at the Martyrs’ Mausoleum in Yangon, killing 17 South Koreans and four Myanmar nationals. Chun, whose arrival was delayed by traffic, survived the attack.

Tens of thousands of supporters came out to greet opposition leader Daw Aung San Suu Kyi during her first visit to Chin State in more than 10 years. The trip, which also included stops in western Sagaing Region, aimed to gain support for

Japan’s government will provide 10 billion yen (US$96 million) in aid to improve living conditions in ethnic minority areas of Myanmar over the next five years, the country’s ambassador to Myanmar, Mikio Numata, announced on Jan. 6. At a press conference in Yangon cohosted by Yohei Sasakawa, the chairman of the Nippon Foundation, the ambassador said the aid, which will be mostly in the form of grants, would be used to improve living standards in ethnic areas affected by decades of conflict. Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe has pledged to provide a total of more than 150 billion yen ($1.4 billion) in loans and grants to Myanmar

Bid to Liquidate Myanmar Times Fails

The Myanmar Times made by the majority shareholder of the newspaper’s publisher, Myanmar Consolidated Media (MCM). Dr. Tin Tun Oo, the 51 percent shareholder in MCM, filed the application last August because of a dispute with managing director Ross Dunkley, an Australian who represents the owners of the remaining 49 percent of the company. On Dec. 31, the Pyi Myanmar daily newspaper, owned by Dr. Tin Tun Oo, carried a public notice demanding that MCM cease printing all its titles on Jan. 1. However, in a

public notice published in the English edition of the Myanmar Times on Jan. 6, MCM reassured readers that “business continues as usual.”

Six Govt Soldiers Killed in ‘Friendly Fire’ Incident

Four men died on the spot and two died later from their injuries. Hpakant, an area famed for its jade mines, is also a major flashpoint in the ongoing conflict between the government army and the KIA.

A small-scale jade miner works in Hpakant Township, Kachin State.

Myanmar Says Ready to Mediate on South China Sea

Hlaing

inhabitants clashed with police who had attempted to confiscate their mobile phones. According to the Arakan Project, a Thailand-based rights PHOTO: NLD

An armed policeman observes a scene at an unofficial camp for displaced Muslims in Sittwe Township in May 2013.

group with an extensive network of contacts in Rakhine State, possibly dozens of Muslim women and children were killed in the attack.

9 February 2014 TheIrrawaddy

A Taang National Liberation Army (TNLA) soldier looks on during celebrations to mark the 51st anniversary of the Taang National Resistance Day at Homain in northern Shan State’s Nansan Township on Jan. 13, 2014. The TNLA also marked the occasion by burning opium, production of which increased by 23 percent in Myanmar in 2013, according to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime.

for many of the country’s citizens, and precious little has been done to improve the situation.

There are many examples of “development” in Myanmar turning into unmitigated disaster, but none is worse than what has happened in Hpakant over the past 20 years. Famous for its high-quality jade, this region of Kachin State has been reduced to a wasteland since a ceasefire agreement was signed by the government army and the ethnic Kachin Independence Organization in 1994, paving the way for an all-out assault on its jade-studded mountains.

Fueled by Chinese demand (and largely controlled by Chinese business interests), the rape of Hpakant has left it deeply scarred. Entire mountains have been leveled and whole new lakes—filled with polluted water—have been formed, all to enrich “investors” and corrupt officials.

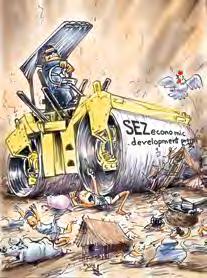

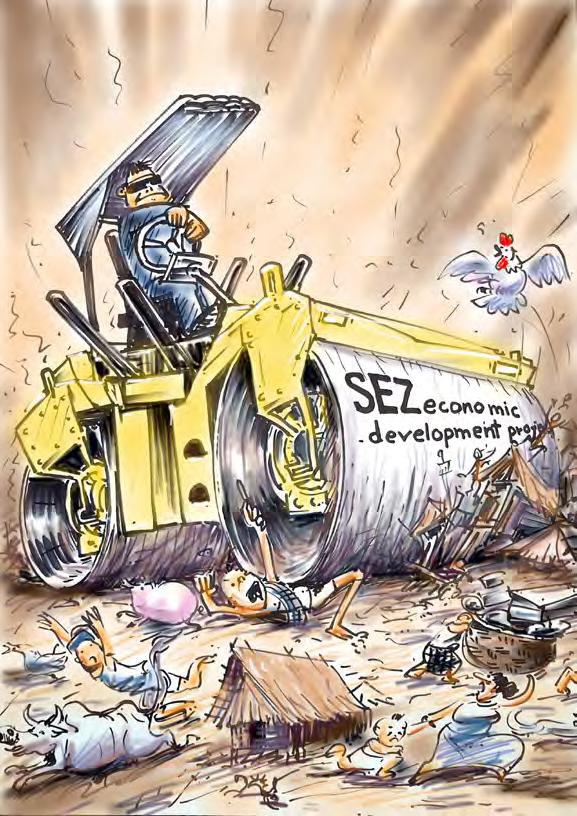

By AUNG ZAWIn Myanmar, there are few things people dread more than the sudden appearance of rich businessmen in their town or village.

Ever since the country’s military rulers abandoned socialism in the wake of the 1988 pro-democracy uprising, well-connected cronies and other business partners of the allpowerful generals have been almost as feared as the men in uniform themselves. To stay in power, the hated regime put the whole country up for grabs, and if someone with money or influence wanted the land your family had lived on for generations, it was theirs for the taking.

Many things have changed in Myanmar over the past few years, but unfortunately, this isn’t one of them. Land grabs and forced displacement are still an inescapable fact of life

In exchange for the wealth beneath their feet, the people of Hpakant have received nothing—except rampant crime and drug abuse, which rot their communities the way that unregulated mining has eaten away at the region’s landscape.

There is more than one guilty party in this sordid tale of social and environmental degradation, but the chief player is the Union of Myanmar Economic Holdings Ltd. (UMEHL), a military-run conglomerate that still dominates large parts of the national economy, despite the transition to quasicivilian rule nearly three years ago.

Needless to say, the people of Myanmar will never see any benefit from this wholesale theft of national treasure. Once it is extracted from the ground, much of Hpakant’s jade is smuggled across the country’s northern border, while the revenues that remain in the country end up in private hands or are used to finance a deadly conflict that further victimizes the powerless people of Kachin State.

In some ways, Dawei, in Myanmar’s far south, is a very different story. Instead of natural resources, its chief asset is its geography: Located some 350 km west of Bangkok and

Peace and prosperity will only come to Myanmar when its economy is based on something other than the ruthless exploitation of its people and resources

possessing a deep-sea port, it seems ideally situated to become a major transport hub for the region.

To realize this dream, billions of dollars will have to be poured into Dawei (whereas in Hpakant, billions have been extracted). Most of that money may be set to come from Thailand, which also hopes to attract Japanese investment in the planned Dawei Special Economic Zone (SEZ). The Myanmar government has boasted that the project will not only transform a coastal backwater into an economic powerhouse employing thousands of people, but will also become an engine for the national economy.

The trouble is that none of this can be done without exacting huge social and environmental costs, and the signs so far are that the government has learned little from the travesties of the past about how to mitigate the negative impact of large-scale economic development.

In Dawei, as in Hpakant, people have been forced to leave their homes, often with inadequate compensation. Fears of massive damage to the environment from the construction of an industrial zone that will spew toxic chemicals have never been properly addressed. And a hasty ceasefire agreement with former adversaries active in the area (the 4th Brigade of the Karen National Liberation Army) offers as yet no real promise of lasting peace.

Strangely, the “experts” and “analysts” who have been flocking to Naypyitaw to applaud the government’s economic reforms have been silent on these issues, as if they assume that the “new and improved Myanmar” won’t repeat the mistakes of the past. But what is to prevent Dawei becoming another kind of developmental blackspot, like Hpakant? Certainly there are no laws in place to protect people’s right to their land, or the land itself from the ravages of blind greed.

President U Thein Sein, who won praise for suspending the Myitsone hydropower dam in Kachin State—

another megaproject designed to benefit a neighboring country at the expense of local people—has also acted as if he sees no need to seriously examine the impact of large-scale foreign investment in Myanmar’s economy. It’s unlikely that he is unaware of the problems, so we can only conclude that he doesn’t care enough about them to exert any political will to find solutions.

Since the opening of Myanmar, everyone, including Western governments, has talked about the country’s rich natural resources and its vast economic potential. There is no doubt that as Asia’s last frontier, Myanmar is ripe for development in many sectors, including energy, mining, tourism, and agriculture. But to realize its true potential, the country will need to radically change the way it does business, away from practices that benefit the powerful while imposing huge burdens on ordinary people.

Myanmar has long been the poorest country in a fast-growing region, weakened by a predatory state and vulnerable to exploitation by better-off neighbors. So changing the way Myanmar develops its economy is not just about doing right by its citizens—it is also about building a stronger nation.

Aung Zaw is the founding editorin-chief of The Irrawaddy. PHOTO: JPAING / THE IRRAWADDYAfter decades as the underdog, does Myanmar’s future now look brighter than that of its hitherto more fortunate neighbor?

By DAVID I. STEINBERG / WASHINGTON, D.C.Thailand’s future had long been considered both stable and optimistic. In spite of the numerous coups since the abolition of absolute monarchy in 1932 and the continuing unrest in the Muslim south, the social and hierarchical order of Thai society has until recently been maintained, and economic development has markedly progressed.

The profound current social and political upheaval that is now evident in that state, however—exemplified by the color-coded red and yellow factions and the military, coupled with the problems associated with the future of the palace—is now a cause for great

concern. Whatever one’s definition of democracy, the political prospects of the Thai state are in question. The gaps between the people and the middle and upper classes, together with the military establishment and the palace, have sporadically spilled into the streets for almost a decade.

Myanmar, in contrast to Thailand, has long been on the minus side of any political or economic equation. For half a century, economic autarky and decline, authoritarian rule directly or indirectly by the military, minority insurrections, arbitrary and ineffective leadership, and international isolation have sapped whatever strength that multicultural society had on independence. Any bets

on the future of either state would have been heavily, indeed overwhelmingly, weighted in favor of Thailand; the odds against Myanmar would have been astronomical. And so they were—until recently. Developments in both states have altered the odds.

Events in Thailand and Myanmar should cause cautious recalibration of such assessments. Such reconsiderations are not simply based on the major and widespread reforms carried out since 2011 by the government of President U Thein Sein. Although these positive changes grow ever less fragile as they are continuously implemented, a number of fundamental issues still need attention. Massive problems with the minorities and virulent anti-Muslim prejudice persist, and conceptions of democracy are still as rudimentary as they are among segments of the Thai elite. Myanmar’s democracy is still far from complete.

More basic are the social differences between the two states in spite of

their shared Buddhist heritages. The majority Burman society is far more egalitarian. Observers may comment on the ubiquitous role of the military in Myanmar, compared to Thailand, and its past control over all avenues of social mobility in that society. This is a situation unique in the history of the region, and is reflected in cabinet appointments when both regimes were militarily controlled. In Myanmar about 95 percent of such positions were given to the military, whereas in Thailand only 25 percent went to military officers. But the essential difference between the two states lies in the social hierarchy. Thailand has been and remains essentially hierarchical and events of the past decade or so have illustrated that this structure has

started to become politically undone. Myanmar is quite different. The majority Burman areas of Myanmar had become perhaps the most mobile of societies in Southeast Asia in the post-colonial era. The reintroduction of the monarchy was never seriously considered on independence, and a hereditary royal elite was not perpetuated. Civilian and later military elites in Myanmar have sprung from the people, and social classes among Burmans became far more permeable and fluid than in Thailand. Since for some 50 years the private sector in Myanmar was abhorred under a socialist economy, keeping economic class distinctions in check was not until recently an issue, although it is likely to be exacerbated over time.

How Thailand will resolve its present crisis is unclear. And the future role of the monarchy is a matter of some question. Years ago it was possible to write that Myanmar would have been better off with a monarch who by his very presence and prestige could adjudicate political squabbling and rivalries—as when two disputatious Thai military leaders had to sit on the floor while His Majesty, in a chair, essentially told them to get their acts together. Those days are, perhaps, over in Thailand but that such a hierarchy has not existed in modern independent Myanmar may be a long-term advantage even if had been a shorter-term detriment to political stability. Although military-civilian mistrust in Myanmar is evident among Burmans, class cleavages are minimal in comparison with Thailand.

The reintegration of military and civilian strands of at least Burman society is far more likely over time and also more easily accomplished than the equivalent in Thailand. The Myanmar military was, so they say, once taught, “This uniform comes from the people. This gun comes from the people…” The present armed forces may have forgotten that dictum in their thrust for power, prestige, and privilege, resulting in their isolation from much of the populace, but they will be more easily be reconciled with the newly emerging civilian elite than in the more socially disparate Thailand, with its far more rigid class structure.

Myanmar must deal fairly and effectively with its minorities, integrating them into a nationhood without cultural assimilation. Then, the social future of Myanmar would indeed look bright. Observers would be wise to keep their minds open to the potentials of these two contiguous states. Too often we have taken the past as predicting the future.

David I Steinberg is Visiting Scholar at SAIS, Johns Hopkins University and Distinguished Professor of Asian Studies Emeritus, Georgetown University.

Above: Democracy in turmoil: Anti-government supporters on a stage in Bangkok in midJanuary, when the People’s Democratic Reform Committee sought to shut down the Thai capital and replace the administration of PM Yingluck Shinawatra with an unelected “people’s council.”

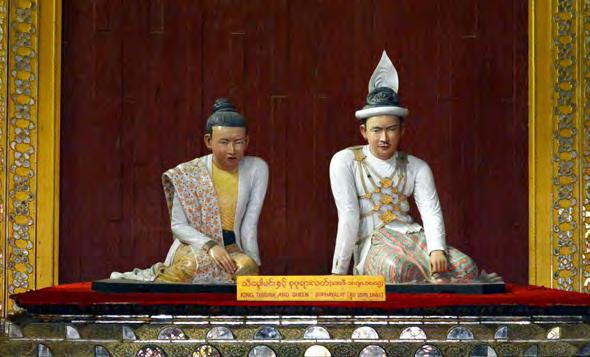

Previous page: Images of Myanmar’s last reigning monarchs, King Thibaw and Queen Supayalat, on display in Mandalay Palace. After gaining independence, Myanmar never seriously considered reintroducing the monarchy.

Above: Democracy in turmoil: Anti-government supporters on a stage in Bangkok in midJanuary, when the People’s Democratic Reform Committee sought to shut down the Thai capital and replace the administration of PM Yingluck Shinawatra with an unelected “people’s council.”

Previous page: Images of Myanmar’s last reigning monarchs, King Thibaw and Queen Supayalat, on display in Mandalay Palace. After gaining independence, Myanmar never seriously considered reintroducing the monarchy.

UKyaw Thein Lwin, who prefers to be called “Uncle K.T.,” is an exuberant, talkative person. When asked about Dha-Byet-See (“The Broom”), he rolls his eyes and smiles as he prepares to tell a story about his days as a young navy officer and his role in the famous Battle of Insein.

A year after Myanmar regained its independence, civil war threatened to tear the country apart. An ethnic Kayin rebellion had started and Kayin soldiers in the national army had mounted a mutiny. In early February 1949, Kayin rebels overran the Air Force Ordnance Depot in Yangon’s Mingaladon Township and seized ammunition and guns, which they used to take over neighboring Insein Township.

The Kayin rebels decided to seize control of Insein because of a series of arson attacks that appeared to target the area’s large Kayin community. Some, including U Kyaw Thein Lwin, later came to believe that Gen. Ne Win, one of the legendary “Thirty Comrades” who fought against the British during WWII, was behind the attacks, which succeeded in agitating local Kayin civilians and forcing a showdown with the Kayin rebels.

Soon after the Kayin seized Insein, the two highest-ranking ethnic Kayin serving in the armed forces— Commander-in-chief Gen. Smith Dun and wing commander Saw Shi So—were dismissed, and Gen. Ne Win

was given control of the army. Now firmly in charge, the country’s future dictator ordered an airlift of battlehardened veterans from the 5th Burma Rifles stationed in Rakhine State to the capital.

A key player in a decisive battle that changed the course of Myanmar’s history recalls his role and reflects on what might have happened

Top of page: Dha-Byet-See (“The Broom”), the 40-mm Bofors gun that helped save Yangon

Above: U Kyaw Thein Lwin in his office during his days as a young navy officer.

Left:

Believing that time was not on their side, the Kayin rebels appealed to fellow Kayin in the Second Karen Rifles stationed in Pyay—“the bestequipped battalion of our army at that time,” according to U Kyaw Thein

Lwin—to rush down to help them in Insein. They answered the call of their ethnic brethren, and it fell to U Kyaw Thein Lwin and his comrades to stop them.

U Kyaw Thein Lwin, who at the time was a young, British-trained navy officer, was assigned to defend the city with two Bofors guns, including one nicknamed “The Broom” because of the efficiency with which it swept away any hostile force in its path.

It was at Wetkaw, in Bago Region, that then Capt. Kyaw Thein Lwin used

the Bofors guns to cut down the Kayin troops coming down from Pyay. The guns were mounted on wheels and were capable of firing 40-mm shells at 120 rounds per minute. He opened fire point-blank at 500 yards, knocking out advancing armored personnel carriers.

Halted in their tracks, the Kayin mutineers were unable to join the rebels in Insein and were forced to flee to the Bago Yoma mountain range. After 112 days of fierce fighting, the Battle of Insein ended in a victory for the government side, and the landscape of the ethnic struggle changed forever.

“We were very close to the complete fall of the government,” U Kyaw Thein Lwin, who is now in his mid-80s, recalled. “Every day, we had situation meetings [in the War Office] where British officers advised us.”

Ironically, after a hard day fighting with Kayin soldiers, he would often spend his evenings in the company of Kayin girls, taking them to see American movies in Yangon. Needless to say, he didn’t discuss what he was doing in Insein and beyond.

U Kyaw Thein Lwin came away from the experience of fighting the Kayin with real respect for his adversaries. “I defended the city as a soldier. It was never about race or nationalism,” he insisted. Later, while studying in London in the 1950s, he had to leave the navy because he was suspected of sympathizing with the Kayin.

What if things had turned out differently? U Kyaw Thein Lwin said that even if the Kayin had succeeded in their bid to seize control of Yangon, they wouldn’t have been able to form a government, because they simply weren’t ready to do it on their own.

“They would have had to form an alliance with the Burmans. Then there would probably have been a decent government,” he said.

Yan Pai contributed to this article. A full account of U Kyaw Thein Lwin’s involvement in the Battle of Insein is available in his book, “Dha-ByetSee: The Gun that Saved Rangoon” (published under his pen name Myoma-Lwin).

“They eat up the hills like they’re devouring cakes.

Hills three or four hundred feet high are completely flattened, or even turned into holes 300 feet deep. Where there used to be mountains, now there are lakes,” said U Cho, a resident of Hpakant, the town in Kachin State famed for its jade mines.

Like many others in the area, U Cho is a jade dealer. But even he struggles to comprehend the scale of the destruction wrought by the jade mines here.

“They use dynamite to blast away whole mountains. The mountains collapse just like the World Trade Center on 9/11. With modern technology, a mountain can be reduced to flat land within one month,” he said.

Located about 220 miles (350 km) north of Mandalay, Hpakant is the source of the world’s highestquality jade. Surrounded by hills and mountains that produce jade and gold, the area is so rich in mineral wealth that residents say that they used to be able to find jade even when they were building house foundations or digging wells.

Two decades of “peace” in Hpakant have reduced the center of Myanmar’s jade industry to an environmental and social disaster area

But the extraction of the region’s earth-bound riches has utterly transformed the landscape, leaving devastation in its wake. Around the villages of Lonekin, Ma Mot and Sai Taung, for instance, the mountains have been replaced with massive tailings piles, and effluent from a muddy artificial lake pollutes the U Ru stream that runs right through the heart of Hpakant town.

“In the past, you could see the rocks at the bottom of the U Ru stream, it was so clean. Now the water is murky and toxic because of the jade mining. It is dying,” said U Maung Than, another Hpakant resident.

Mung Myit, a local jade merchant, jumped into the conversation. “When we were young, our grandparents told us that the hill and mountains here were full of big trees,” he said. “They even heard tigers at night, and the air was so cool that you had to use a blanket when you went to bed, even in the hot season.”

Although those days are long past, things didn’t really begin to heat up in Hpakant until 20 years ago, when the Kachin Independence Organization (KIO), an ethnic armed group, signed a ceasefire agreement with the then ruling military junta, opening up the region to large-scale exploitation.

Since then, at least 500 companies have registered to mine in Hpakant. In addition to a combined workforce in the hundreds of thousands, the new operators brought heavy machines with them to make the job of tearing down mountains that much easier.

One of the biggest players in this enormous enterprise is the Union of Myanmar Economic Holdings Ltd. (UMEHL), a military-run conglomerate that dominates many sectors of the country’s economy. Some generals or their families are also believed to be privately involved; for instance, locals say that Daw Kyaing Kyaing, wife of ex-dictator Snr-Gen Than Shwe, has a company here. But Chinese businessmen, working though local proxy companies or in partnership with state-owned businesses, are widely

seen as the ones in control of the jade trade.

That should come as no surprise: China has been importing jadeite, or hard jade, from Myanmar since the 13th century. Today, about 90 percent of the world’s jadeite is mined in the Hpakant area, and most of it is sold to China, Hong Kong and Taiwan. As a symbol of virtue and excellence, it was much in demand for use in products commemorating the 2008 Beijing Olympics.

Despite its enormous value, however, only a fraction of the money spent on Myanmar’s jade ever gets recorded. In September of last year, Reuters reported that the country produced more than 43 million kg of jade in the 2011/12 fiscal year, but generated only US$34 million through official exports—a far cry from the $8 billion that it was worth, according to a report by the Harvard Ash Center cited by Reuters.

Under the terms of the 1994 ceasefire agreement, the government and the KIO shared control of Hpakant equally—an arrangement that paved the way for a full-scale assault on the region’s mineral wealth, but did little to

lay the groundwork for a lasting peace.

At a time when many now engaged in peacemaking efforts are arguing that increased investment in ethnic minority areas will help to ease tensions, it is interesting to note that since 1988, an estimated 65 percent of all foreign direct investment (FDI) in

Myanmar has been poured into three of the country’s most conflict-ridden states. According to a report published by the Netherlands-based think tank Transnational Institute in February 2013, Kachin State ranked first, receiving $8.3 billion, or 25 percent, of the FDI in Myanmar over this 25-year

period, followed by Rakhine State ($7.5 billion) and Shan State ($6.6 billion).

In the case of Kachin State, the impact of this investment has been largely detrimental, not only to the environment, but also to the prospects for a lasting peace.

“There are many reasons for going

to war, and we can say that business interests are one of them,” said Maj.Gen. Gun Maw, the deputy chief of staff of the KIO’s armed wing, the Kachin Independence Army (KIA), explaining what led to the collapse of the Kachin ceasefire in June 2011.

Since fighting resumed in the state, the KIO has lost much of its influence in Hpakant, where large-scale mining has been suspended as a result of the ongoing conflict. However, local residents say that the town is still full of both KIA and government spies and is regarded as a “brown zone,” where clashes between the two sides could break out at any time.

While the government and the KIO were dividing the spoils of a lucrative industry that both profited from through concession fees and taxes, local people lost far more than they gained. As elsewhere in the country, many were forced off their land to make way for big companies, often with little or no compensation.

“Many inhabitants of this area have very painful feelings, but they can’t do anything about it because the companies coming in all have permission from the government,” said Sutdu Yup Zau Hkawng, the head of the Jade Land Company, one of the leading mining companies in Hpakant.

Despite the fact that companies operating here are required to pay three types of tax (10 percent of a winning bid on a concession; 10 percent of the value of any jade discovered; and 10 percent of earnings from sales at government jade emporiums), little if any of this government revenue is ever used to improve the lives of people living in the region.

Located about 48 miles (77 km) from the state capital of Myitkyina and accessible only by four-wheel drive vehicles during the rainy season, Hpakant looks more like a small, isolated village than the center of a multi-billion dollar industry. Even the phone lines here don’t work much of the time.

“Hpakant is a place where people go to make money and bring it elsewhere.

Top of page: Local jade miners take significant risks to search for jade on unstable mountain faces, despite periodic crackdowns by the Myanmar military.

Above: Small-scale miners work hard for rewards.

Top of page: Local jade miners take significant risks to search for jade on unstable mountain faces, despite periodic crackdowns by the Myanmar military.

Above: Small-scale miners work hard for rewards.

Not even the local authorities are interested in developing the place,” said veteran journalist Bertil Lintner, author of many books on Myanmar, including “Land of Jade: A Journey from India through Northern Burma to China.”

According to economist Sean Turnell, a long-time observer of Myanmar’s economy, jade was the country’s largest source of foreign earnings two years ago and likely remains a close second to natural gas now that the Shwe gas fields have come on line via a newly built pipeline to China’s Yunnan Province. He noted, however, that the nature of jade as a resource made the jade-mining industry even less transparent than Myanmar’s notoriously opaque energy sector.

“Jade is an important asset via which wealth can be effectively stored and transferred across borders. Along the way, tax is easily avoided. In a sense, it is an underground financial market, which exists largely because [Myanmar] still lacks a more formal and effective one,” he said.

Ironically, the collapse of the ceasefire and the suspension of fullscale mining operations have given local prospectors and other smalltime operators a chance to profit from an industry that under normal circumstances excludes them. Using primitive hand tools, they scour mountains stripped bare by heavy

machines, searching for the precious green stones.

But this kind of mining isn’t just difficult, dangerous work; it is also illegal and subject to regular crackdowns. Like everything else in this lawless town, however, that doesn’t prevent anyone from doing it.

“When the government soldiers come, we just flee,” said Khaing Maung Doe, an ethnic Rakhine jade prospector. “They usually come twice a day, so we just stop what we’re doing and run. If we don’t we’ll be arrested and charged.”

Those unlucky enough to get caught aren’t long getting back into the game, however. All they have to do is pay a “fine” of about 50,000 to 100,000 kyat ($50-100)—usually paid directly to the arresting guard—and they’re back in business.

Even in a country where corruption is pretty much the norm, Hpakant stands out for the sheer amount of

heroin addicts can openly shoot up.

“Hpakant is the second Hong Kong,” said U Win Htun Htun, a local jade dealer. “You can get everything you want here—girls, methamphetamines, heroin. Half the people here are drug addicts.”

U Shwe Thein, the chairman of a local branch of the opposition National League for Democracy, said he had made proposals for tackling Hpakant’s drug problem, but they fell on deaf ears.

“I proposed a campaign to eliminate drugs, but the authorities said they could only try to reduce drug use,” he said. “Even though heroin and other drugs are sold by individuals, I feel the authorities are behind the sale, as they are the ones running the town.”

He added that this situation has left local people feeling completely powerless. “They are like children without parents. They don’t know who to turn to when they are abused.”

graft that goes on here. Crime—from theft, prostitution and gambling to drug trafficking and murder—is rampant, but even when reported, the local authorities rarely if ever take action.

Massage parlors and gambling dens line the main road of Ma Mot, a village just west of Hpakant, while in Sai Taung, located on the other side of the U Ru stream, there’s a place where

Worst of all, he said, the rest of the country seems oblivious to what’s happening in Hpakant.

“It’s worse here than in Letpadaung,” he said, referring to the site of a controversial Chinese-backed coppermining project in Sagaing Region that has attracted nationwide attention. “We’ve lost our mountains one by one, but nobody seems to care.”

A man prepares to cut into a raw green stone, hoping to find quality jade.

By KYAW PHYO THA / YANGON

By KYAW PHYO THA / YANGON

On the night of July 28, 1988, when the people of Myanmar had taken to the streets in an attempt to topple a one-party dictatorship, the Associated Press (AP) bureau in Bangkok received a telex. It read: “Daddy has been taken away. He won’t be available to answer your queries.”

It was a message from the daughter-cum-apprentice of local reporter U Sein Win, who had been working inside Myanmar for the American wire service. It informed her father’s employers of his arrest by the authorities for his coverage of the mounting protests that year. She had already been helping her father to cover the frenetic events of the uprising, but the writer of the telex would soon file stories for the newswire herself.

“It was all I could do as I was not, at that time, their official reporter,” said Daw Aye Aye Win as she recalled the message she sent over 25 years ago.

One year later, in 1989, she joined AP herself. Then aged 36, she was the only female journalist in Myanmar at that time, letting the world know what was happening inside the country. After the protests were violently put down, the repressive military held on

to power and retained strict control over information in Myanmar. Eleven journalists remained in jail until 2011.

“I’m a journalist by choice, not by accident,” said the slender woman, who at 60 can still hold her own at a press conference, firing off questions even among fellow reporters young enough to be her grandchildren.

So far, she is the only living woman journalist in Myanmar to win four international journalism awards. In 2013 she received her most recent prize, the Honor Medal for Distinguished Service in Journalism from the Missouri School of Journalism, awarded for her “life-long dedication to honest and courageous journalism, often at the risk of personal safety,” according to the school’s website.

During the 25 years of her AP career, Daw Aye Aye Win has covered every one of Myanmar’s ups and downs— from the monk-led revolt in 2007, to Cyclone Nargis, which killed more than 130,000 people in 2008, to the advent of a quasi-civilian government in 2011.

“She has always covered with distinction and sometimes with physical courage,” said Denis D. Gray, who oversaw Myanmar coverage as the AP bureau chief in neighboring Thailand from 1976 to 2011.

The former bureau chief told The Irrawaddy that even though his reporter sometimes seemed “reckless in her opinions and sometimes in actions,” she is made of the same toughness, stubbornness, pride in the profession and intelligence as her father, U Sein Win, who worked for AP for 20 years. The late veteran journalist, who passed away in October, was famous for his efforts for press freedom in Myanmar, enduring three stints in prison as he chronicled several decades of his country’s turbulent history.

Daw Aye Aye Win has also been harassed numerous times by the authorities. Her phone line was tapped and she was on the government’s watch list as she worked for a foreign news agency. She was once branded “the axe-handle of the foreign press” by Myanmar’s state-run media.

These days, the government takes a very different view of her efforts. Deputy Minister of Information U Ye Htut, who is also the spokesperson for

the President’s Office, said he sees her “a smart woman who really wants to work as a professional journalist.”

“Of course, we sometimes have different points of view,” he told The Irrawaddy. “But I have rarely seen inaccuracies in her reporting and noticed that she has never failed to raise questions bravely whenever she needed to ask, not only to government officials, but to some prominent politicians whom some local journalists are reluctant to shoot.”

Though she was fortunate not to be jailed like some other journalists, in 1997 and 1998 Daw Aye Aye Win was interrogated by Myanmar’s dreaded Military Intelligence about her attendance at anti-government protests as a reporter.

Once she was asked to explain why she missed a Revolutionary Day state dinner, instead attending an opposition National League for Democracy (NLD) event.

“At first, my heart was racing, but

a sense of righteousness overwhelmed me. So I replied to them that ‘the NLD makes news but the dinner doesn’t,’” she said, recounting the interrogation session. “They mistakenly thought that they could intimidate journalists. It’s not the case for me.”

Maybe she inherits that indomitable spirit from her father.

“Daddy told me we must never give up against anyone who persecutes us,” she said. “He said: ‘They can’t put our spirit in prison. As long as we refuse to bow to our persecutors, we win.’ That’s one of the things I learnt from my Dad, my hero.”

Since her formative years, Daw Aye Aye Win has been familiar with the life of a journalist. She remembers

her father returning home late at night and heading out early in the morning when he was the editor and publisher of The Guardian in the late 1950s. She witnessed how he gathered news, grabbed scoops and faced his arrests. He told her she mustn’t smile at her captors.

But when she declared that she wanted to be a journalist, it was U Sein Win who was most opposed to her choice of career.

“Maybe he feared that I would be jailed like him,” Daw Aye Aye Win explained. “Finally, he promised to teach me journalism, but there was no job offer.”

In 1989, after grooming her for 10 years, U Sein Win finally surrendered his AP job to Daw Aye Aye Win—she called it “a family coup.” He moved to a Japanese news agency.

Though she has won international awards for her work, Daw Aye Aye Win thinks she is still far behind the footsteps of prominent Myanmar woman journalists of the past— like Ludu Daw Amar—who fought colonialism and injustice with their pens.

Despite her modesty, she has rarely enjoyed favoritism as a woman. Instead, said Daw Aye Aye Win, she earned scorn.

“Our Asian society doesn’t think highly of women’s role. People thought I got the job thanks to my Dad and they underestimated me, saying I wouldn’t make it,” she recalled.

“So I’ve vowed to myself to prove to them I could be a journalist, and I found out it’s not a big deal as long as you have interest, responsibility and perseverance.”

Asked her reaction to winning prizes, Daw Aye Aye Win said it’s nice to be recognized, but really, awards are for movie stars. “Journalists don’t need such a high profile,” she added.

‘She has always covered with distinction…’

–Denis Gray, former AP bureau chiefDaw Aye Aye Win at her home in Yangon. PHOTO: JPAING / THE IRRAWADDY

It is generally assumed that Daw Aung San Suu Kyi’s first public appearance was at the Shwedagon Pagoda on Aug. 26, 1988, when hundreds of thousands of people came to hear her speak. But she had actually appeared in public two days before that historic event. On Aug. 24, she stood on a makeshift platform outside Yangon General Hospital, made a brief speech and announced that a rally would be held at the Shwedagon. A photograph taken at the time shows her with a microphone in hand, some curious nurses looking out through a window in the hospital—and a tall man in a striped shirt and with a slightly bent back standing behind her. Beside her is a young woman, the famous film actress Khin Thida Htun.

The man in the striped shirt was Maung Thaw Ka, a well-known writer who, together with the journalist and editor U Win Tin and film director U Moe Thu, had persuaded Daw Aung San Suu Kyi to become involved in the movement for democracy. After the military had gunned down thousands of demonstrators on Aug. 8-10, the movement needed a leader, a voice that everyone could rally behind. Maung Thaw Ka, U Win Tin and U Moe Thu went to see Daw Aung San Suu Kyi. They knew Gen. Aung San’s daughter was in town because they had seen her picture in the paper, laying a wreath on her father’s grave on Martyrs’ Day, July 19. They were not sure, however, that she could speak Myanmar. She had been abroad for many years and, in her native

country, few outside the immediate family knew her.

But it was worth a try and the three intellectuals ventured over to her house on University Avenue. It soon became clear to them that her spoken Myanmar was excellent. But she was not interested. She had come back only to nurse her ailing mother, Gen. Aung San’s widow Daw Khin Kyi, she said. The trio persisted and paid a second visit to University Avenue. This time she agreed. She realized that as her father’s daughter, she could not remain silent when the country was in upheaval. The rest is history.

U Win Tin is still active, writing, making speeches and giving interviews to journalists despite his advanced age. He will turn 85 on March 12. U Moe Thu is making a movie about Gen. Aung San together with Zagarnar. But Maung Thaw Ka passed away on June 11, 1991, shortly before his 63rd birthday. He was a dear friend of mine and I met him in Yangon when I was there in February 1989, my last visit to the country until my name was taken off the blacklist in 2012.

In the late 1980s, he had a small photo shop near the Sule Pagoda in downtown Yangon, where he sold film and people could have Photostat copies made. We spent a couple of days together, and he gave me a vivid account of the massive demonstrations that had shaken Yangon less than half a year before. And he took me around Yangon in his car, a small pickup truck, to see the places where the killings had taken place.

We became good friends, and without Maung Thaw Ka’s help I would never have been able to write my account of the uprising, “Outrage: Burma’s Struggle for Democracy.”

Maung Thaw Ka was actually his penname. He was born Ba Thaw in 1928 in Shwebo. His other name was Nur Marmed. He and his family were Muslims, and that was not an issue when he, U Win Tin and U Moe Thu, two Buddhists, went to see Daw Aung San Suu Kyi in August 1988. It was before some fanatics began to try to drive wedges between people of different faiths.

In 1947, a year before independence, he joined the navy as a cadet. He was later promoted to commander of the Myanmar Navy’s ship 103. That was going to change his life forever. While patrolling the southeastern coastline of Myanmar in November 1956, the ship sank. Lieutenant Ba Thaw, as he was then known, and 26 of his crew escaped in two rubber life rafts. One of those with nine men onboard was never seen again. The others were rescued by a passing Japanese ship 12 days later. By then, seven of the 18 men in Ba Thaw’s raft were dead, and another died on the Japanese ship.

After that tragedy, Lt. Ba Thaw left the navy and became Maung Thaw Ka the writer. The first book he authored was called “Taikyeyin 103,” or “Battleship 103.” It was a gripping account of the shipwreck and the crew’s struggle to survive on the open sea. He wrote short stories and poems and translated Shakespeare, John Donne and Percy Bysshe Shelley into Myanmar. He was also the translator of William Cowper’s “The Solitude of Alexander Selkirk,” verses about the Scottish seaman who was shipwrecked on an island in the Pacific, and on whose life Daniel Defoe based his famous novel Robinson Crusoe.

Apart from his poetry, Maung Thaw Ka was best known for his satirical wit. He had a wonderful sense of humor and, although he became the

editor of Forward, a government-run monthly in Myanmar and English, he never ceased poking fun at people in power. And even under the harsh rule of the Burma Socialist Programme Party, he got away with it. He was after all a national hero because of his background in the navy and then, of course, Battleship 103. Some of his satires were collected as “Ya Ma Kar Lu Lin,” or “The Alcoholic.” What appeared to be the ranting of a drunkard were, in reality, biting criticism of the corrupt, established order. Sometimes he was blunter. In her “Letters from Burma,” Daw Aung San Suu Kyi recalls: “On being told that a fellow writer believed in ghosts, Hsaya [teacher] Maung Thaw Ka riposted: ‘He believes in anything, he even believes in the Burma Socialist Programme Party!’”

Maung Thaw Ka became one of the members of the Central Executive Committee of the National League for Democracy when it was set up on Sept. 27, 1988. And like all the other pro-democracy leaders, he was arrested when intelligence chief Gen. Khin Nyunt cracked down on the movement in July 1989. He was sentenced to 20 years’ imprisonment with hard labor. His “crime”? He had tried to “split the armed forces,” the judge said. He had actually written a letter to his old friends in the navy asking for their support and urging them not to take part in the killings of unarmed demonstrators.

Maung Thaw Ka was badly beaten during his interrogation, which made his rather frail physical condition worse. He already suffered from spondylitis, or inflammation of the vertebra, which he had contracted while drifting around in that life raft in 1956 and had left him with a bent spine.

According to the official version, Maung Thaw Ka became “unwell” and was transferred to hospital, where he died. But one of his former fellow inmates in Insein Jail tells a different story. Maung Thaw Ka was already dead when his body was taken to hospital. He had been kept in a barren cell without food following his support for a hunger strike among the political prisoners in Insein. It would have looked very bad if a well-respected person like him had died on the concrete floor in his cell, so the authorities had to come up with a blatant lie. Maung Thaw Ka was, in fact, murdered.

Maung Thaw Ka was laid to rest in the Sunni cemetery in Yangon, beside his brother Ba Zaw, or Gholan Marmed, a captain in the infantry who had died from natural causes in 1980. The cemetery was swarming with military intelligence agents when Maung Thaw Ka’s coffin was brought there in 1991. During my last visit to Myanmar, I went to Maung Thaw Ka’s grave to pay my respects to him, a dear friend, a brilliant mind—and a true Myanmar patriot.

Apart from his poetry, Maung Thaw Ka was best known for his satirical wit.Left: Maung Thaw Ka standing beside Daw Aung San Suu Kyi when she gave her first public speech on a makeshift platform at Yangon General Hospital on Aug. 24, 1988. The famous actress Khin Thida Htun is standing on the far right. Above: Maung Thaw Ka’s grave (beside his brother’s grave) in the Sunni cemetery in Yangon. PHOTO: U SONNY NYEIN PHOTO: BERTIL LINTNER

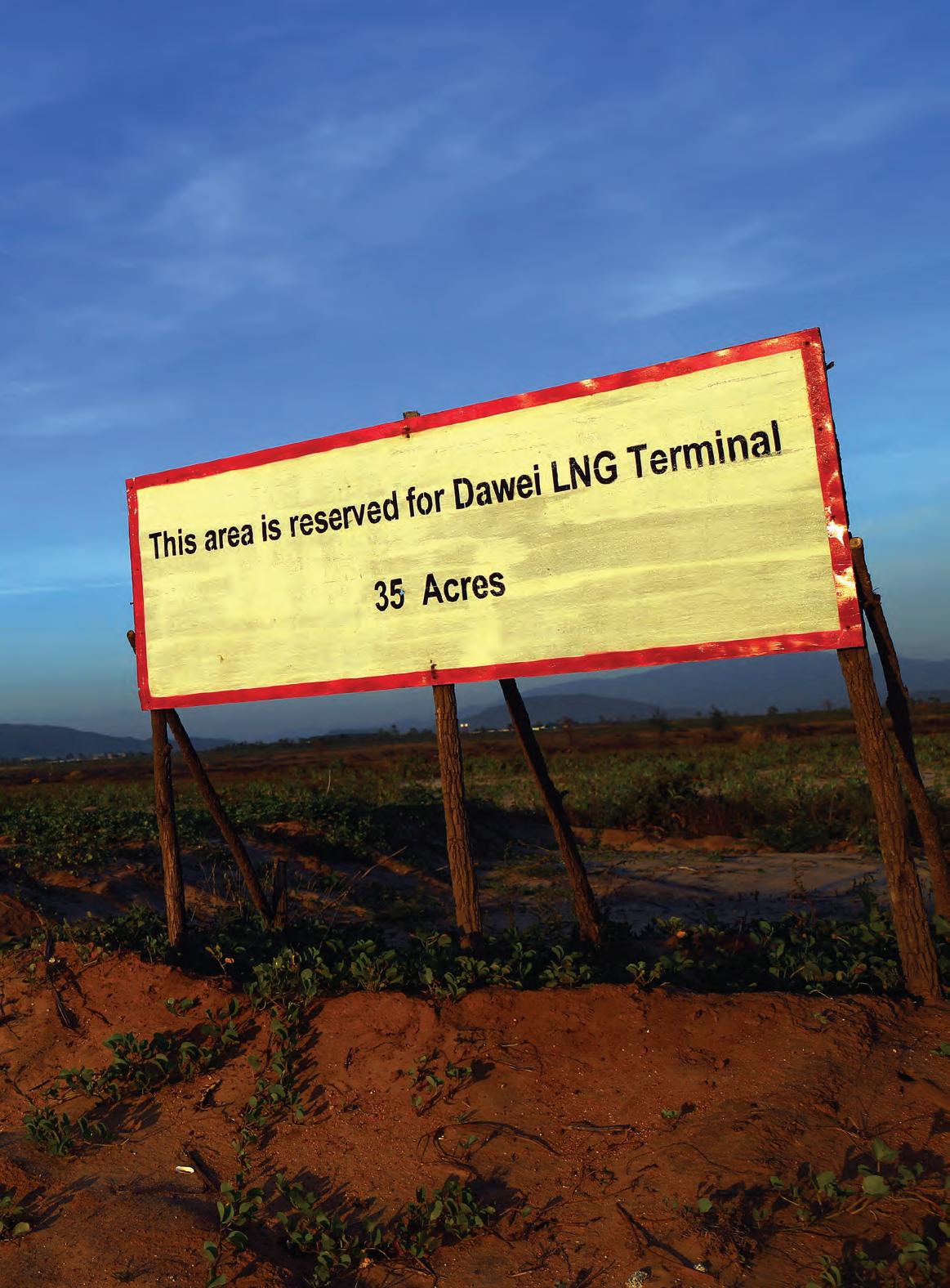

The planned mega-project in the far south has stalled, but many residents in the region still fear what’s coming

By PAUL VRIEZE & HTET NAING ZAW / MAUNGMAGAN, Tanintharyi Region

A signpost for a planned new gas terminal near the shoreline at the Dawei SEZ.

PHOTO: JPAING / THE IRRAWADDY

A signpost for a planned new gas terminal near the shoreline at the Dawei SEZ.

PHOTO: JPAING / THE IRRAWADDY

UAung Myint, a community leader from Mudu village, stands next to a meter-long, gold-colored footprint with 108 Buddhist signs that was carved on a large boulder many centuries ago. “We believe that the Buddha visited here and that this is his left footprint,” he said. The relic housed in a pagoda is part of the heritage and lore of the ethnic Dawei people, who have lived in the southern Tanintharyi Region since around the 8th century. The ancient artifact gave the cluster of villages on this remote coastal plain its local name: Nabule, which means left foot in the Pali language, said U Aung Myint.

The area known on most maps as northern Maungmagan is located some 20 km northwest of Dawei city, and it is here that Southeast Asia’s biggest industrial estate is being planned: the Dawei Special Economic Zone (SEZ).

The creation of a multi-billion dollar “new global gateway of Indochina” at the site of secluded, ancient villages underscores the dramatic changes that this long-isolated coastal region will experience if the project is realized.

The Myanmar government has said it considers the Dawei SEZ a potential economic engine for the impoverished country and officials boast of the region’s future as an industrial hub.

Many Dawei residents and activists, however, continue to fear that they will bear the costs, rather than the benefits, of the sweeping changes that the massive project looks set to bring. They complain of heavy environmental impacts, forced eviction from the SEZ without adequate compensation, and a region-wide surge in land grabs.

Although their pagodas will not be knocked down, many in Nabule oppose leaving their ancestral villages for fear of losing their Dawei heritage. “Our forefathers lived here for more than 1,000 years,” said U

Above: U Aung Myint of Mudu village fears the SEZ will herald the decline of an ancient culture.

Right: Construction is underway at a section of the SEZ. Far right: A woman walks past a fenced-off area of the development zone.

Below: Children at play at a farm growing watermelons near Dawei.

Aung Myint. “I am certain that the more the project will be developed, the more our culture will decline.”

In 2008, Myanmar’s former military government and Thailand signed a deal to develop the SEZ, which was envisaged to include a huge industrial estate, a deep-sea port for supertankers, and highway, railroad and oil pipeline routes to Bangkok, some 350 km to the east. International firms were expected to bid for heavy industries such as a massive coal-fired plant, a steel plant, oil refineries and a chemical fertilizer plant.

Billed as Myanmar’s largest export industry zone and a regional trade hub, the project’s strategic location would allow companies from Thailand, Vietnam, Cambodia and China to send goods overland to the Bay of Bengal and bypass the busy Strait of Malacca shipping lane.

Government officials, such as U Aung Tun Thet of the Myanmar

Investment Commission, presented glowing plans to “transform Dawei into a newly opened investment destination and logistic hub of the region” valued at US$50 billion, which would “generate a very large amount of employment.”

Italian-Thai Development Public Company Ltd (ITD) won the project concession and sought to attract $8 billion in investment to develop the zone’s infrastructure.

However, ITD failed to attract investors and the project has encountered numerous delays. In November 2013, Myanmar and Thailand took ITD off the project and called for the involvement of Japan’s government and Japanese firms. Tokyo has since shown some interest in reviving the plan. On Nov. 21 Mitsubishi announced it would work with ITD and the Thai government to develop a 7,000-megawatt coal plant.

In early 2014, though the future shape of the SEZ remains uncertain, many locals continue to fear what lies ahead.

Since 2010, the project and its current and future effects have come to dominate much of life and conversation in the one-time bucolic backwater. By that year, ITD had begun land demarcation and very limited construction at the SEZ. It had also started constructing a water reservoir and a two-lane access road to Thailand. The company’s plans envisaged the resettlement of 12,000 people from six ethnic Dawei villages in Maungmagan, while thousands of ethnic Kayin (Karen) villagers in the Tanintharyi Yoma mountain range would lose farmland.

In Nabule, a coastal plain dotted with villages growing rubber, betel nut and cashew nut, hundreds of farmers have already seen their land confiscated for the project, which has been planned to cover 200 square kilometers of untouched beaches and farmland.

Villagers and the Dawei Development Association (DDA), a local NGO monitoring the SEZ, said authorities and ITD had pressured

farmers to give up land without proper consultation, while compensation procedures had been inconsistent. Future resettlement sites, they claim, lack arable farmland.

In Mudu village about 70 farmers have lost 198 acres (80 hectares) of land. “Sometimes [ITD] offered [compensation] money and then they occupied the land. Other times they first occupied the land and then they offered money,” said U Aung Myint, adding that about 30 farmers received no compensation as they refused to give up their land ownership.

Affected farmers said they were offered compensation amounts ranging from $500 to $3,000 per acre. Although the latter amount is a fairly high, residents often demanded more, as land prices around the SEZ have surged to between $5,000 and $10,000 per acre.

U Aung Myint lost 10 acres (4 hectares) of betel nut trees and like many farmers he is anxious about his future livelihood at one of three planned relocation sites. “I have no idea what I’m going to do, I have no land left,” he said, adding that only migrant workers had been offered jobs at the SEZ project.

DDA said ITD’s project implementation methods had violated villagers’ human rights. “Most people rely on plantation farming, but the

government cannot move them and guarantee their future livelihoods,” said DDA coordinator U Thant Zin.

U Zaw Thura, a local activist and Dawei University scholar, expressed concern over the industrial zone’s expected environmental pollution. “We are worried about the northwest monsoon, it will blow all the exhaust fumes of the coal plant and other industries inland and over Dawei city,” he said, adding that ITD had refused to release the project’s environmental impact assessment (EIA).

Although work started in 2010, little has yet been achieved. The proposed SEZ remains a largely empty area, with a small port, dirt roads, a few simple office build-

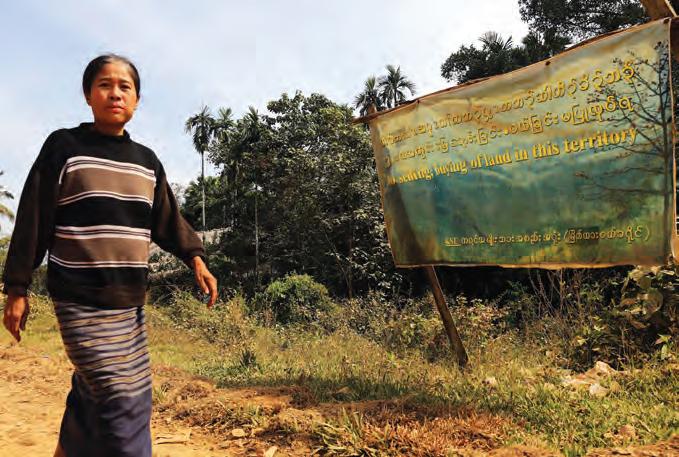

Left: Daw Eimal of impoverished Kablee Hnit Pin village is furious that villagers have lost access to mangrove forests that were once a precious source of food and firewood. Below: A resident of Thapyu Chaung, village in the Tanintharyi hills, walks by a sign erected by the Karen National Union that reads “No selling, buying of land in this territory.”

ings and barren living quarters for workers.

In November, just before ITD’s concession to run the project was revoked, managers at its Dawei support office were reluctant to talk to reporters. EIA reports by Bangkok’s Chulanglokorn University on display in a glass showcase could not be made available because staff had “no key.”

Since then, a high-ranking Myanmar official involved in the planning of the SEZ said in a phone call that the government was “trying very hard to mitigate” the project’s local impacts, adding that farmers directly affected were “being properly compensated.”

The official, who spoke on condition of anonymity, said Naypyitaw was confident that a Japanese consortium would help to resume project work in mid-2014.

However, some economists question whether the SEZ will ever attract industrial investment, or offer any benefits to Myanmar.

“Successful SEZs have an underlying economic need and rationality first, and proceed from there. Here we seem to have an idea akin

A local man walks along pipes on a beachfront in the Dawei SEZ area as the sun goes down.

PHOTO: J PAING / THE IRRAWADDY

A local man walks along pipes on a beachfront in the Dawei SEZ area as the sun goes down.

PHOTO: J PAING / THE IRRAWADDY

to ‘build it and they will come,’” said Sean Turnell, a professor at Macquarie University in Sydney, Australia, who advises opposition leader Daw Aung San Suu Kyi.

Any economic benefits of the project, he said, “will accrue to Thailand rather than Myanmar. Dawei in no way opens up the Myanmar hinterland to trade.”

For decades, Dawei was an isolated region, located in Myanmar’s deep south and cut off from nearby Thailand by a Karen National Union (KNU) insurgency in the forested Tanintharyi Yoma mountain range that runs along the border.

The planned SEZ, a 2012 government-KNU ceasefire and economic reforms by President U Thein Sein’s quasi-civilian government have changed all that and Dawei’s days as an inaccessible backwater now seem over.

In October, ITD completed a 132-km gravel access road running from the SEZ through the KNUcontrolled mountain range to the Thai border. Some 30 minibuses from Thailand, carrying tourists and business visitors, now reportedly arrive in Dawei every day.

Land prices have surged throughout Dawei District, as local and Thai business people move to buy up land for investment in tourism projects, real estate, plantation farming and mining in the newly unlocked region.

Among local communities, concerns continue to grow. Near Dawei city and around the SEZ numerous investment projects have sprung up, as have controversies over land ownership.

One of the biggest local investors is Dawei Development Public Company Ltd (DDPC), which was set up by a group of Dawei businessmen in 2011 with a view to gaining a stake in the region’s expected, rapid economic development, managing director U Ye Htut Naing said.

DDPC is chaired by local tycoon

U Khin Soe, whose Anawar Hlwam Company controls much of southern Myanmar’s highly productive coastal fishing industry. The firm’s website boasts of $50 million in registered capital and 47 fishing vessels. U Khin Soe also owns Apex gas stations, the 55-room Apex Hotel in Naypyitaw and has announced plans to launch Apex Airline.

DDPC plans to build a cement factory and a mine, and has begun constructing a $3 million shopping mall near Dawei town and a tourist resort on a 475-acre (190-hectare) pristine beach-front just south of the SEZ. The resort is planned to include a $14-million luxury hotel, bungalows and apartments, a golf course and an “ethnic races village” supposedly representing Dawei’s peoples.

“We already collected the [investment] money,” said U Ye Htut Naing. “We expect an increase in business and tourist visitors. There are no sleeping facilities at the SEZ; we want businessmen to sleep in our bungalows.”

At the sprawling project site a dozen bungalows have already been built on the white sandy beaches overlooking the azure waters of the Andaman Sea. A billboard shows an artistic rendition of the future resort extending far inland, into an area currently covered with mangrove forest and cashew nut trees.

About half a kilometer away, at the edge of the forest, lies Kablee Hnit Pin village. Here, some 130 impoverished families reside in rickety huts built along a litter-strewn dirt

road. They live hand-to-mouth, working as day laborers and collecting food from the forest.

In October, however, the DDPC obtained the mangrove area from the Forest Department, and workers began cutting down trees and erecting fencing. The villagers have since grown desperate and complain that they have been deprived of a crucial food and income source that they have used for decades.

“Before the company came we found everything we needed there: fish, crabs, fruit, and firewood. Now we struggle to get food,” said Daw Hla, a 43-year-old mother of nine. “We heard that they will take our village land too!” fumed Daw Eimal, a mother of five children.

Emotions ran high among the roughly 100 villagers who gathered to

speak with reporters, and when several Special Branch officers in plain clothes showed up to take photographs, some confronted the thuggish-looking men.

“We want this area back, we received no money in compensation!” shouted Daw Hla. “Our future generation is lost, we planted many fruit trees in this area but the company took it all.”

U Ye Htut Naing dismissed the complaints and said his firm had received the forest land “for free” because DDPC Chairman “U Khin Soe is close to the [Tanintharyi Region] chief minister” and had convinced him of the project’s positive economic impacts. The poor villagers, he said, would simply have to be patient because “after the local economy develops there will be new

fected by ITD’s projects.

During a visit to Thapyu Chaung, a small village of thatchedroofed and wooden huts located in a lush mountain valley some 30 km east of Dawei town, impoverished Kayin villagers complained that road construction waste had polluted a local stream.

“This river is now destroyed, the fish and crabs are all gone,” Naw Pa Lay Zar, 74, said in perfect English. “We only have one clean stream that we can use for drinking water in the [dry season]. It doesn’t flow very well and we have to go very far to the upper part of the river to get water.”

During the interview, two pickup trucks, including a gleaming new Toyota Hilux SUV with a Myanmar license plate, pulled up carrying a

when they don’t own it—this creates a lot of problems. That’s why the KNU banned land sales,” he said, referring to a KNU notification placed along roads in the area that reads: “No selling, buying of land in this territory.”

U Thant Zin of DDA said the sudden influx of business people looking to buy—or grab—land was having a disruptive effect on the long-suffering Kayin communities and causing tensions in the area, which is still awash with weapons after decades of conflict.

In the Tanintharyi mountains, meanwhile, several thousand Kayin villagers have lost land to ITD’s construction of a 2,970-acre (1,200-hectare) water reservoir and the new road to Thailand, which is set to eventually become a four-lane highway.

The angered villagers have complained of poor compensation and appealed to the KNU for help. In September, they blocked the road for three weeks at a site some 50 km west of the SEZ. All along the road, meanwhile, business people are buying up land and complaints of land-grabbing have surged, according to the DDA, which warns that tens of thousands of Kayin villagers will be directly and indirectly af-

dozen fighters of Karen National Liberation Army Brigade 4. A KNLA captain inquired about the reporters’ visit, but discussions quickly turned to the surge in land disputes.

“The buying and selling of land is a very big problem here,” said the officer, who declined to be identified. “Many businessmen come here now that the roads are becoming better. They came with licenses obtained in Naypyitaw, showing that they can buy the land.”

“The KNU never approved these sales, and some people sell land

“In some villages, the bulldozers are parked [to begin work] and the people are so worried that they wait with guns to guard their land,” he said, adding that the KNU had also cut business deals that affected communities, such as in southern Dawei District, where it has allowed Thailand’s East Star Company and local firm Mayflower to operate a coal-mining concession.

U Thant Zin warned that the rise in land sales and disputes threatens donor-backed government plans to return Kayin refugees from Thailand in coming years.

“This is also related to the peace process. So many Kayin refugees [from the Dawei region] live across the border in the camp near Kanchanaburi. How can they return when there is no access to land?” he asked.

For most people living in Myanmar’s largest city, starting a business or buying a home is becoming an increasingly unattainable dream, as strong demand—and a crony stranglehold on the local real estate market—continue to drive property prices ever higher.

In some parts of the city, the cost of buying land has increased tenfold over the past five years. In downtown Yangon, for instance, prices reach as high as US$1,500 per square foot on Sule Pagoda Road in Kyauktada Township. Property values in residential areas along Inya Lake have also spiked.

Even before 2011, when Myanmar introduced economic and political reforms that ushered in an influx of foreign investment, Yangon’s property values were on an upward trend. In 2007, property taxes were cut from 50 to 15 percent, spurring the first surge in demand. (In 2012, they were raised again to 37 percent in a bid to cool off an overheated market, but to no avail.)

But even as properties were changing hands, little in the way of development was taking place in the country’s largest city. When the then ruling military regime moved the capital to Naypyitaw in 2005, most of the largest developers followed, leaving Yangon to languish in neglect.

“Developers close to the previous government got a lot of new construction projects in Naypyitaw, so they moved there,” said U Khun Htoo, a spokesperson for the Naing Group Construction Co., Ltd. “Many projects were left unfinished, some of which still

haven’t been completed.”

The smaller companies that did stay behind managed to increase their market share, but faced renewed pressure from the big-time players after 2010, when the regime started privatizing public assets. In a frenzy of deals that took place behind closed doors, government-owned buildings and factories were sold off to close business associates of the ruling generals—few of whom, according to U Khun Htoo, had any interest in developing them.

“In this privatization process, the winners were not real property developers,” he said, giving the example of the Padonma Theater in Sanchaung Township, which was sold for 15 billion kyat (US$15 million) to a consortium of five investors, including Dr Ko Ko Gyi, the chairman of Capital Diamond Star Group, whose real estate development portfolio is currently limited to two shopping centers, one in Yangon and another in Naypyitaw.

“The location of the old Padonma Theater is very good, and if it had been sold to a developer, it could have been used to build residential properties or office towers to meet market demand,” said U Khun Htoo.

“All the best locations ended up in the hands of cronies, who are holding onto the land because they know it will increase in value as time passes,” he added.

In recent years, the number of new residential units has increased by a mere 20,000 per year—roughly a third of the number needed to accommodate the city’s growing population. The primary reason for the slow pace of growth, say developers, is the excessive cost of purchasing land.

“The actual construction costs involved in building a condominium are about 40-50,000 kyat per square foot,” said a director of the Shine Construction Co., Ltd., who asked not to be identified. “At that rate, condos should sell for around 150,000 kyat per square foot. But because of the cost of land, the price is more like 500,000 kyat per square foot.”

This is bad news for would-be homebuyers, many of whom say they’ve given up on the idea of buying a place of their own.

“I can’t even imagine owning a condo in Yangon,” said U Ko Ko Zaw, who works for a car rental agency in the city. He said he couldn’t even afford a modest downtown apartment selling for 70 million to 200 million kyat ($70-200,000), much less a luxury unit going for 800 million kyat.

Under the current circumstances— rapidly rising property prices and stagnant wages—developers remain reluctant to begin work on new projects until consumers’ purchasing power catches up with their ownership ambitions.