The Irrawaddy magazine has covered Myanmar, its neighbors and Southeast Asia since 1993.

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF: Aung Zaw

EDITOR (English Edition): Kyaw Zwa Moe

ASSOCIATE EDITOR: Sandy Barron

COPY DESK: Paul Vrieze; Andrew D. Kaspar; David Kay; Feliz Solomon; Sean Gleeson

CONTRIBUTORS to this issue: Aung Zaw; Kyaw Zwa Moe; Kyaw Phyo Tha; Zarni Mann; Nyein Nyein; Kyaw Hsu Mon; Yen Snaing; Kyaw Kha; Lawi Weng; William Boot; Sanay Lin; Nobel Zaw; Claudia Sosa; Naing Swann; Saw Yan Naing; Bone Myat; May Sitt Paing; Feliz Solomon; Tamas Wells

PHOTOGRAPHERS: JPaing; Sai Zaw; Hein Htet; Teza Hlaing; Steve Tickner

LAYOUT DESIGNER: Banjong Banriankit

SENIOR MANAGER : Win Thu (Regional Office)

MANAGER: Phyo Thu Htet (Yangon Bureau)

REGIONAL HEADQUARTERS MAILING ADDRESS: The Irrawaddy, P.O. Box 242, CMU Post Office, Chiang Mai 50200, Thailand.

YANGON BUREAU : Building No 170/175, Room No

806, MGW Tower, Bo Aung Kyaw Street (Middle Block), Botataung Township, Yangon, Myanmar.

TEL: 01 388521, 01 389762

EMAIL: editors@irrawaddy.org

SALES&ADVERTISING: advertising@irrawaddy.org

SUBSCRIPTIONS: subscriptions@irrawaddy.org

PRINTER: Chotana Printing (Chiang Mai, Thailand)

PUBLISHER LICENSE : 13215047701213

16 | Land Row: Fields of Fire

As officials trade blame, local opposition to the controversial Letpadaung copper mine simmers on

20 | Guest Column: Quality Talk?

Developers and donors are big on “community consultation”–but are they sincere?

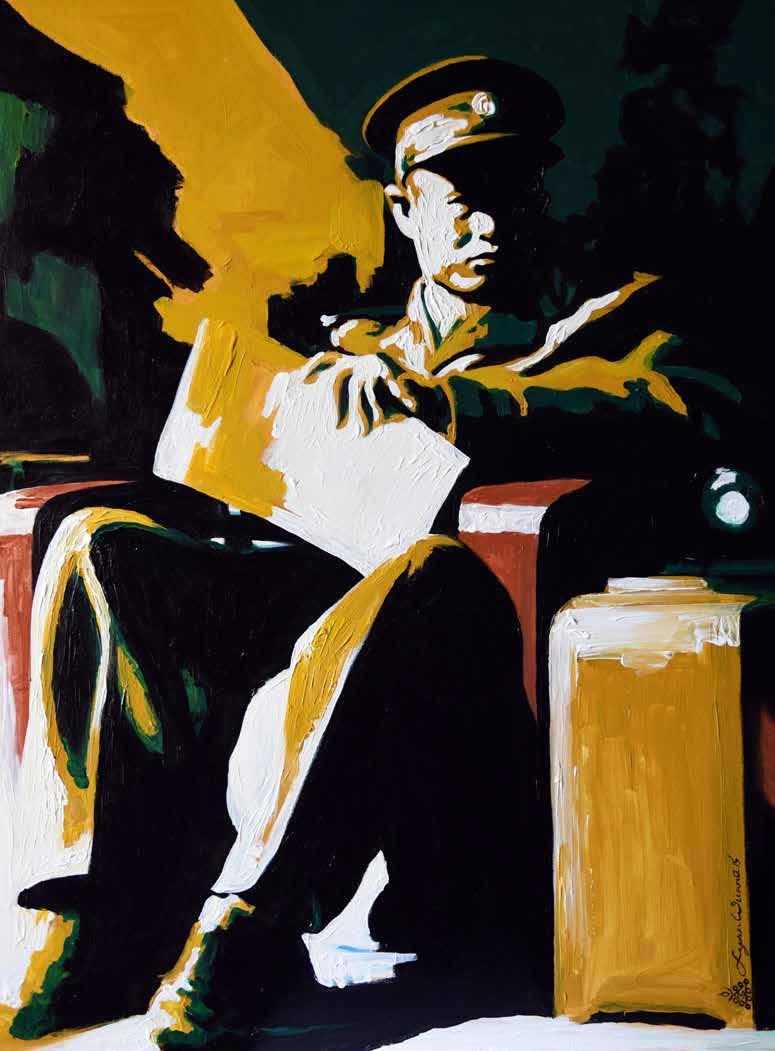

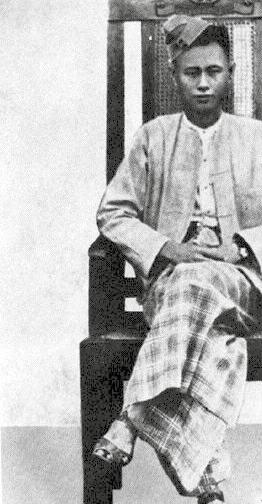

22 | COVER A Legacy Unfulfilled

100 years since his birth, Aung San’s aspirations for a unified and democratic Myanmar are yet to be realized

30 | In the North: Birds ‘Sold for Snacks’ Wildlife enthusiasts raise alarm over Paleik Lake

34 | Feature: Me and My Language

Why mother tongues matter

39 | Interview: Books ‘Have a Future’

42 | Trade: Crackdown on Smugglers

Official teams seizing illegal gemstones, timber, wildlife

44 | Extractive Industries: Miners Weigh Risks

Uncertainties holding investors back

46 | Signposts: FDI Exceeds Forecast

REGIONAL

48 | Garment Industry Feels Strain

Small garment factories in Bangladesh are struggling to survive

Dr. Thaung Htun is director of the Institute for Peace and Social Justice in Myanmar and a leading advocate for fair land use policies and farmer’s rights.

A former member of the All Burma Students Democratic Front and UN representative for the National Coalition Government of the Union of Burma, he returned to the country in 2013 to help strengthen civil society and share skills and knowledge for a democratic transition.

The government introduced two new land laws in 2012—the Farmland Law and the Vacant, Fallow, and Virgin Lands Management Law—but Dr. Thaung Htun discusses with The Irrawaddy’s Yen Snaing how these have not solved ongoing issues and why he is still working for land policy and law reform.

is what is needed. Myanmar is behind Thailand and Vietnam in agricultural productivity.

What is your organization doing in relation to advocacy on the existing laws?

What can be achieved is limited. Existing laws include the Farmland Law and the Vacant, Fallow, and Virgin Lands Law. The bylaw for the Protecting Rights and Enhancing Welfare of Farmers Law is not finished yet. But these laws cannot fully solve current land ownership disputes and land confiscation issues.

With what expectations and aims did you come back to Myanmar?

I came back to the country in December 2012 with the aim of taking part in strengthening political parties and civil society and to help facilitate discussions on much-needed policy reform in the country. Since 2013, the Institute for Peace and Social Justice (IPSJ) has been helping with capacity building for political parties and civil society groups, and holding policy discussion workshops. We have focused on agricultural reform and land rights. Currently, we are working on the new draft land-use laws, together with international and local experts. In addition to this, IPSJ has facilitated discussions on rule of law, mining law, the conservation of rivers, sustainable community fishery and alternative energy options. We are also providing technical help to assist in forming farmer’s organizations.

Why did you focus primarily on the agricultural sector?

My parents come from a farming family and I wanted to contribute something back to poor farmers. And 70 percent of Myanmar’s population are farmers. The president has said his priority is to reduce poverty. Without legitimizing

land tenure security for small farmers, addressing the issue of landlessness and [prioritizing] rural development, poverty reduction can’t succeed.

Micro-finance alone is not enough. There are other needs like upgrading agricultural knowledge, financial management skills, market stability for agricultural products and infrastructure in the agricultural sector. Transportation is also key for sending goods to the market. So is electrification.

But most important is “social capital”—the culture of collective decision making and implementation in village-level development issues, and rural values like honesty, restricting alcohol consumption and gambling, and neighborly help… Checks and balances within society were ruined under authoritarian rule. People lost self-confidence under poverty.

Millions have left for Thailand and Malaysia as undocumented migrant workers. That led to a scarcity of farm workers. Climate change also has an impact. The monsoon comes 15 days late and is gone 15 days earlier. We have seen unusual rain fall due to cyclones in harvesting season. Farmers, individually, cannot resolve all this; it needs to be addressed collectively.

Skills and knowledge for farmers, as well as agricultural policy reform

Within limits, farmers can attempt to have their grievances addressed within the framework of the above mentioned laws. To respond to these issues, parliament formed the Farmland Investigation Commission in August 2012. That commission has produced four reports so far which have investigated land confiscation related to: (1) the expansion of urban development; (2) the development of industrial zones; (3) the expansion of military cantonments; (4) national projects such as railways, highways, airports; (5) the building of state factories and plants; (6) the inclusion of existing farmlands in the allocation of land to private agriculture and livestock enterprises.

But the administration is working quite slowly in response to the commission’s suggestions. Among 6,559 complaint letters to the commission, they could only solve 307 cases—only 4.68 percent. Most of the current land issues arose between 1989 and 2010. Land issues arising after 2010 are quite rare, although they exist.

Problems also arise due to weaknesses in the independence of the judiciary and the rule of law. And there are weaknesses in the bureaucracy relating to land records.

There are some cases where

lands have been acquired but the farmers don’t receive fair compensation or land substitutes. Is this another weakness?

The chapter on land acquisition in the draft National Land Use Policy needs to be more detailed in outlining international best practices. We should take a look at international standards. For example, in India, the land acquisition act enacted during British rule was amended in 2013. They called it The Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement Act. It included the right to compensation, prenotification and negotiation, and transparency in land acquisition and resettlement plans in accordance with current living standards.

Some [project owners] have said they have compensated farmers 30 lakh [3,000,000 kyat] for an acre of land. But farmers only know how to farm and have no idea how to invest in a business. That money will quickly run out.

There are also many problems concerning land valuation and the policy framework needs to be more specific here too. The most important thing is having a pro-poor land use policy framework and amending existing laws: the Farmland Law; the Vacant, Fallow and Virgin Land Law; the Forest Law; investment laws; the Mining Law; environmental laws and the Land Acquisition Law in line with that policy framework.

Indonesia and Cambodia have included land redistribution in their recent land policy frameworks in addition to land administration and land management. Industrial countries like Japan, South Korea and Taiwan rebuilt their economies with an emphasis on land reform, land redistribution and legitimizing

land tenure security for small farmers. These reform initiatives motivated small farmers to work hard on their land to improve agricultural output. They believed in farming and their governments lent money and helped improve techniques. From there, they started small and medium sized agro-based industries in rural areas. Production increased in rural areas and the accumulation of capital and business management experience helped create a strong foundation

are no youths anymore. How can we handle this?

How are we going to handle unused land? How can the government distribute vacant land and turn it into farmland? What is happening now is that vacant land is given to those who have money. Look at land around Hlaing Thar Yar and Shwe Pyi Thar, which used to be farmland. It is neither used for agriculture or industry now. Why? Because a minority holds on to that land, to sell on the market as a commodity.

for these countries to transform into industrialized countries.

It depends on the political will of those in power. According to some statistics, around 46 percent of the population is landless. We need to create land for them. Their way out now is to go to Yangon and work at Hlaing Thar Yar Industrial Zone, or go to Malaysia and Thailand. In some rural areas, there

Our land costs are the highest in Southeast Asia. When garment industries come here from abroad, let’s say if they bring US$500,000, they have to spend 80 percent of it on renting land; how can they do business? Without punishing land speculation and land monopolies according to the law, there will be lots of problems in industrial growth, agricultural development and poverty reduction. Current land policy cannot stop this. Policy change is the way forward.

—Tar Aik Bong, chairman of the Ta’ang National Liberation Army which celebrated ‘Revolution Day’ in January with a show of force. He blamed the group’s bullish stance on the Myanmar Army's failure to address political rights for the Palaung.

“More and more people are coming to join our troops.”

“Burma is still a long way from being a rights-respecting democracy.”

—Samantha Power, US representative to the United Nations

“When I sniff glue, I close my eyes and in my dreams I go to nightclubs and have fun.”

—Ko Min, 15, who ekes out a living scavenging through trash on Yangon's back streets, speaking to Associated Press.

The president also looked ahead to elections later this year that he said would be “a remarkable milestone in the history of Myanmar,” and emphasized the importance of signing a nationwide ceasefire with Myanmar’s many ethnic armed groups.

Fighting flared between government troops and the Kachin Independence Army (KIA) on Jan. 15, forcing about 1,000 people to flee their homes in northern Myanmar’s Hpakant Township.

President U Thein Sein summoned 48 political, military and ethnic representatives to Naypyitaw on Jan. 12 for a meeting later described by the opposition National League for Democracy (NLD) as “hardly a fruitful one.”

In a transcript of U Thein Sein’s opening remarks, the state-run New Light of Myanmar newspaper quoted the president as saying, “Constitutional amendment will be based on the results of political dialogues and [the] peace process in line with the 2008 State Constitution.”

Among attendees at the meeting, held at the presidential palace, were Myanmar Army Commander-in-Chief Snr.Gen. Min Aung Hlaing, vice presidents Sai Mauk Kham and U Nyan Tun, NLD leader Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, parliamentary speaker Thura Shwe Mann and 28 ethnic affairs ministers, as well as leaders of ethnic political parties.

Following the meeting, Daw Aung San Suu Kyi accused the president of ignoring proposals for a limited dialogue between herself and a handful of senior government leaders and politicians to discuss constitutional reform. — May Sitt Paing

Participants at an international conference to provide policy recommendations on the future of Yangon called for government coordination to realize the economic, social and physical benefits of heritage conservation in Myanmar’s largest city.

“Given all these opportunities, Yangon could serve as a model not only for Myanmar but cities around the region and across the globe,” said Erica Avrami of the World Monuments Fund, which cohosted “Building the Future: The Role of Heritage in the Sustainable Development of Yangon Forum,” along with the Yangon Heritage Trust.

While summarizing the issues

discussed during the three-day conference, held in Yangon on Jan 15-17, Ms. Avrami said there was a limited institutional framework to facilitate heritage research and activities, with only a handful of NGOs, universities and other organizations doing the work, as well as limited government mandates.

“This interest in heritage has not yet translated into government policy, and there is a lack of coordination among the relevant government agencies,” Ms. Avrami said.

The forum released five priority areas intended to protect heritage, manage heritage processes and promote heritage investment, including official recognition of a downtown conservation area

The fighting took place near Aung Bar Lay and Tagaung village in the jade-rich region in Kachin State about 50 miles northwest of Myitkyina, the state capital. Gunfire began at 6 am, forcing local villagers including about 200 students and some 20 schoolteachers to flee.

The KIA’s Battalion 6 and Myanmar Army troops from Light Infantry Division 22 were the units involved in the fighting, according to Kachin rebel sources.

“Fighting broke out early this morning and it is ongoing,” Du Hka of the KIA’s political wing, the Kachin Independence Organization, told The Irrawaddy by telephone on Jan. 15. “Heavy weapons and artillery shells were fired nonstop. Fighting is escalating as Myanmar troops are entering our territories.”

According to local sources, about 1,000 residents from more than 400 households were affected and sought refuge at local churches. —Saw Yan Naing & Kyaw Kha

and zoning plan; facilitation of conservation and heritage investment; and development of downtown infrastructure, especially projects aimed at enhancing walkability, the city’s waterfront and open spaces. —Kyaw Phyo Tha

Irrawaddy. The office of the Yangon Region government declined to comment when asked about the message.

Yangon police moved to charge distributors and seize copies of satirical comedy film “The Interview,” which depicts an assassination plot against North Korean leader Kim Jong-un, following pressure from the North Korean Embassy.

After a meeting between Yangon Region Chief Minister U Myint Swe and North Korean ambassador Mr. Kim Sok Chol on Jan. 11, the embassy sent a facsimile to the regional government requesting “proper action immediately to stop the copying, distributing and selling” of “The Interview” in Yangon, according to a document seen by The

Two movie stores in Botahtaung and Latha townships were named in the document as distributors of the film, including the M2M Shop on Latha Bounkyi Street, which was raided on Jan. 12 by township police officers who seized over 180 copies of foreign films.

“The seizure is part of the regular crackdown on uncensored films, and ‘The Interview’ was among the foreign films seized,” said Latha Township deputy police chief U Kyaw Kyaw Aung. “The owner of the shop has now been charged under the Video Act.”

The junta-era 1996 Television and Video Act prevents the illegal copying of films and the distribution of films contrary to censorship directives, with a maximum penalty of three years imprisonment or a fine of 100,000 kyat (US$97). — Bone

MyatA high-level delegation of US officials concluded a two-day US-Myanmar Human Rights Dialogue on Jan. 15, the second iteration of what could become a regular affair between the US State Department and the Myanmar government.

Speaking to reporters in Yangon on Jan. 16, US Assistant Secretary of State for Democracy, Human Rights and Labor Tom Malinowski said that while the discussions were “extremely constructive,” issues such as ethnic and religious intolerance pose an urgent threat to creating a stable democracy in Myanmar.

“The use of religion in particular to divide people, whether it is done for political or other purposes, is incredibly dangerous,” Mr. Malinowski warned, emphasizing that religious extremism could have severe consequences particularly in an election year.

Mr. Malinowski led the senior delegation, which included Lt.-Gen. Anthony Crutchfield, deputy commander of the US Pacific Command, and envoys representing departments of religious and refugee affairs.

Following a visit to the Kachin State capital Myitkyina and workshops with rights activists in Yangon, the delegation headed to Naypyitaw for closed-door talks with Union ministers about the nation’s most pressing human rights concerns, including land policy, the rights of ethnic minorities and the role of the military. —Feliz Solomon

About 1,000 farmers, students, laborers, Buddhist monks and community leaders gathered in Mandalay on Jan. 16 to call for better protection of land rights, democratic reforms and abolishment of the military-drafted Constitution.

At a five-hour rally next to U Pwar Pagoda, senior monks, farmers’ representatives and student leaders took turns to give speeches demanding broad political reforms from President U Thein Sein’s nominally civilian government.

The groups said they were sending their demands to Parliament, the

president and foreign embassies. They also called for greater public involvement in their cause and said more rallies would be held in the near future.

“We want to urge the government to listen to the voices of its people and take action to fulfill the needs of the country and citizens,” said Sayadaw U Thawbita, a Mandalay-based member of the Saffron Revolution Buddhist Monks Network.

A particular focus of the activists’ anger was the China-backed Letpadaung copper mine, where recent farmers’ protests against land

seizures led to a violent confrontation with police, who shot and killed local farmer Daw Khin Win. —Zarni Mann

A Naga man carries a fish between his teeth after it was stunned by dynamite which fishermen threw in a creek near Lahe Township, in the Naga Self-Administered Zone in northwest Myanmar, in December 2014. The Naga, a group of tribes historically known as warriors, live on Myanmar's mountainous frontier with India.

After we had paid our respects, the teachers, who were in their 70s and 80s, began to head home. I chased down a teacher who had taught me economics and whose classes had partly involved learning the benefits of Gen. Ne Win’s socialist economic policy, even as we students could see its failures plainly outside the classroom!

I remembered she had always asked certain pupils, including myself, to carry her traditional rattan basket filled with teaching materials and lunch containers. To be allowed to carry the basket had been a special honor; it meant you were one of her favorites.

She was still energetic and she looked at me with a wide smile. I joked, “I became a rebel after taking your class! Thank you!” She giggled and walked on to her car.

Some of the teachers seemed more guarded and weary. They seemed uncertain, even sad; I speculated whether they were perhaps missing students who had never come home after dying on the streets.

Ithought of them often when I was in exile, and they sometimes came to my dreams. After my immediate family members, friends and teachers from my high school days were the people I missed most as the years away rolled on.

Recently I was glad to be able to attend our high school reunion. I wanted to pay respects to the teachers I had not seen in more than 25 years. I was excited to go, but I wasn’t sure quite what to expect.

To my relief, many of the teachers who had taught me subjects like geography, math, history, economics and English were still alive. One arrived in a wheelchair. Others used walking sticks and were aided by assistants. They were in high spirits, though some shed a discreet tear.

“Where have you been?” one teacher asked me. After finishing school, I had disappeared for decades. For a long

time, it had seemed that I would never come home.

The teachers accepted donations and presents from their former students and in return they offered us their best wishes. It was all a little emotional. In Myanmar style, there was a bit of warm commotion amid talk filled with memory and laughing. It was a time to reflect back, and to share tentative hopes. Looking around me, at a time when religious intolerance is increasingly evident, I felt grateful to have had teachers of many religious backgrounds—Christian, Buddhist and Muslim.

I looked for, but did not find, an old friend from sixth grade who was a Karen, like most of our English teachers. To my surprise, the last time I bumped into him was on the ThaiMyanmar border where he had become a soldier. I believe he later moved to the United States.

One of my favorite teachers, who taught math in ninth grade, was in a wheelchair. My schoolmates told me she had often asked about me after I left Myanmar following the political turmoil in 1988. Now in her 80s, she looked at me with tears in her eyes and said, “You finally came home!”

I was thrilled to see that teachers of her age were still with us, and keeping themselves strong and healthy.

A former headmaster in his late 80s did not recognize me at first, but when I mentioned my grandparents’ names, his jaw dropped. “They were my friends. Your grandfather and I played football together!” he said. I made sure to take his picture to show my grandmother who lives with me back home.

A history teacher who followed the news closely was more forthcoming. In quiet tones she confided that she thought the current political opening in Myanmar was significant. But “we have to move gingerly, slowly,” she said, as if warning me not to expect too much in the immediate future.

I asked her about the history we had learned in class, particularly about the ethnic regions and civil conflict. “You

know,’’ she said, ‘‘we taught what the government told us to teach.” It came home to me that just as we were taught not to ask critical questions, but to obey and extend respect, our teachers were under similar pressures.

A friend told me that our former physical training (PT) teacher had recently passed away. We had always enjoyed his class in which we could roam around outside in the fresh air.

I remember he was tall and handsome and had sold snacks to students to earn some extra income. He was a police sergeant in active service, but he would come to school in casual wear. Some students wondered if he was a spy assigned to watch over us. But he was friendly and one of our favorites.

In those days teachers were afraid to discuss political matters. Other subjects, such as sex, were also taboo— we were supposed to be polite! Of course in the school bathrooms you could find indecent writing scrawled on the walls, as well as anti-government slogans.

When I reached the ninth grade, I started skipping classes in favor of sitting in tea shops where I began to catch onto other matters: mainly smoking and politics. Tea shops were a learning ground for dreamers and planners. The young me felt I was among intellectuals, people who thought big in ways that stirred the mind, people who were more imaginative and progressive than our school teachers. The tea shops were the kind of places that nurtured revolutionaries and radicals, where strategies were debated that could change the ruling order.

Many of my female friends remained dutifully in the classroom, hoping to go on to become doctors or engineers. Few considered journalism as a career. But those female students

were also our messengers. They would bring us gossip, as well as inform us of our teachers’ reaction to our absence.

Later on in Yangon I bumped into yet another former teacher, who is now in her 60s. Her husband was a wellknown literature guru and a former political prisoner who spent years behind bars.

days, we shared similar thinking with these figures; namely, the view that we were governed by a bunch of uneducated dictators who were adept at manipulation, repression and guns. We felt as though we were going to hell if we didn’t revolt. And then the time to say “no” came in the form of the 1988 uprising, and many of the friends and

“It’s lucky that you are back here, but I must tell you this,” she warned. “Never get involved in politics because you will always suffer. You will never win. They are not kind-hearted people and they show no humanity!’’

I felt she must offer the same kind of thoughts to her older husband who was resting at home. He was a poet who taught us to be more critical, and a bit more rebellious. He encouraged us to read literature such as Dostoyevsky’s “The Brothers Karamazov,” John Steinbeck’s “Tortilla Flat,” and Jack London’s “The Sea Wolf.” And he steered us towards poetry, including the works of W.B. Yeats

When we finally made it to college, we were exposed to other young and progressive professors and tutors who were bookworms and politicallyminded. Unlike in the high school

teachers I knew ended up serving long jail sentences.

Those teachers, friends and mentors from school, college and the teashops helped shape the person I have become.

Today the dilapidated buildings and classrooms of my former high school in a Yangon suburb appear much the same as they did 25 years ago.

But at the school, amid our reunion, I also sensed a new spirit and a feeling of anticipation. Some young students came up to me and talked and posed for pictures. They mentioned my writings and my TV programs covering political matters. And as I looked back to the 1980s, and I looked at them, I could not but hope for a more promising future.

By KYAW PHYO THA / YANGON

By KYAW PHYO THA / YANGON

When a bulldozer rolled onto her ancestral farmland stretching under the shadow of Letpadaung mountain on a December morning last year, Ma Win Mar was among dozens of farmers who tried to stop it.

But as rubber bullets, fired from cordons of police standing behind the roaring yellow machine, whistled past their ears, all the villagers could do was retreat.

As she helplessly watched the broad steel blade of the machine

uproot a swath of sesame, sunflower and bean crops on her seven-acre land, the 30-year-old woman broke down in tears.

“Why did they do it to me? All we have is our land,” Ma Win Mar said of the day she lost her farmland to one of the biggest Chinese investment projects in the country—the Letpadaung copper mine.

The project is a joint venture between China’s Wanbao mining company—a subsidiary of Norinco, a weapons manufacturer—and the Myanmar military-owned conglomerate Union

of Myanmar Economic Holdings Ltd (UMEHL).

One day before Ma Win Mar lost her land, on Dec. 22, a woman in her 50s was shot dead by police during a clash with villagers at the project site while company employees tried to fence off farmland unlawfully claimed by the company.

It was the latest flashpoint between security forces and local villagers who refused to take compensation from the company for the expansion of the project, from which 100,000 tons of copper is slated to be extracted annually starting from 2015.

The death of Daw Khin Win, who was shot in the head, came just over two years since another violent government crackdown on Letpadaung protestors in November 2012. During the early morning raid,

police used smoke bombs containing white phosphorus to disperse protestors, injuring over 100 people, the majority of them Buddhist monks.

Situated on the western bank of the Chindwin River in Sagaing Region, the Letpadaung copper mine near Monywa in upper Myanmar has been a source of public outcry since 2012.

Myanmar Wanbao Mining Copper Ltd signed a joint venture with UMEHL in mid-2010 and a 60-year land grant for the project was acquired from the Ministry of Home Affairs in August 2012. Since then, just over 7,867 acres of land in the Letpadaung region have been confiscated to make way for the US$997 million expansion of the copper mine.

Following the November 2012 crackdown, the government formed an investigation commission led by Daw Aung San Suu Kyi to determine whether the project should go ahead.

In its report, issued in March 2013, the commission suggested the project should proceed, but only after outstanding concerns affecting “the interests of the country, local people and younger generations” were addressed.

It provided 42 recommendations that included urging stakeholders to devise a new contract that was more beneficial for the country, pay land compensation to local people at the market price and carry out a more comprehensive Environmental and Social Impact Assessment (ESIA).

Myanmar Wanbao Mining Ltd welcomed the decision of the report

The project site was being further secured by fences and the installation of watchtowers in December 2014.

and pledged to heed its call to listen to the needs of the local community. The company, the government and the UMEHL signed a new contract in July 2013 that provided for the government to keep 51 percent of profits from the venture.

Immediately following the report’s release, President U Thein Sein formed a 15-member committee, supervised by a President’s Office minister and including directors from UMEHL and Wanbao as members, to implement the findings of the inquiry commission.

However, none of these official moves managed to quell local opposition to the project arising from loss of farmland, inadequate compensation, the project’s environmental impact and the destruction of sacred religious structures.

Over the past two years, confrontations between villagers and security forces have continued as the mine’s operators attempted to extend the project’s operating area. Four villages have been forced to relocate for the mine so far and land around 32 other farming villages, inhabited by more than 25,000 people, is also being acquired.

Many villagers are reluctant to take compensation after growing up in families that have tilled the surrounding farmlands for generations. For them, their land is their livelihood and the only inheritance they can hand

down to the next generation in their family.

“We are just farmers,” said 38-yearold Hse Tae villager Daw Yee Win, whose 14 acres of land were confiscated last year. “All we know is how to farm. I just want my land back as I am not sure the compensation they pay will guarantee our livelihood. We firmly believe that as long as we can work on our land, we will not go hungry.”

In the wake of the fatal shooting last December, Daw Aung San Suu Kyi said the committee formed by the government to implement her report’s recommendations had failed to act.

“The committee did carry out some recommendations, but it has not fully implemented [them]… It has not followed the recommendations to the letter,” she told the media in December.

In response, U Tin Myint, the secretary of the implementation committee, claimed that 29 out of 42 recommendations had been carried out and an amended ESIA draft was underway, the state-run paper The Mirror reported on Jan. 9.

U Tin Myint said that since 2011, farmland surrounding the mine project area was seized in accordance with land acquisition bylaws and that the committee had paid more than 11 billion

kyat in total for land compensation, at market prices, as suggested by the report.

He added that, although some locals refused to accept compensation for their land, the land could still be confiscated under section 16 of the Land Acquisition Law that, according to the secretary, “permits a district administrator to seize land for a state project without any interference.”

U Tin Myint blamed “outside organizations and networks” for conspiring to destroy the project, a sentiment that faintly echoed a statement issued by Wanbao on Dec. 30 in which the Chinese company referred to political organizations and activists that were seeking to “make political gains.”

The company defended its record in implementing the inquiry commission’s recommendations and claimed it had the “overwhelming support” of local communities. However, it also asserted that issues of land use and resettlement were the responsibility

of the government and the UMEHL.

Daw Khin San Hlaing, a Lower House parliamentarian from Sagaing Region and a member of the investigation commission, said local people had lost faith in the implementation committee as it had failed to carry out most of the recommendations.

“The most evident failure is that the project still doesn’t have an Environmental and Social Impact Assessment. Without the assessment, the company is now trying to expand the project by fencing farmland without

owners’ approval,” she said.

“As a committee endorsed by the president, they should be honest as to why they have failed to implement the recommendations [and indicate] what else is left to be done rather than scapegoating other people.”

The lawmaker said if the committee failed to implement the recommendations of the report, the government should abolish it and form a new one.

She also warned Wanbao that if it couldn’t follow the recommendations,

it should shut down the project, as the mounting issues facing the copper mine could deter potential foreign investment in Myanmar.

Ma Thwe Thwe Win, a Hse Tae villager, said that local people accept the recommendations of the report but feel betrayed that the committee has failed to implement them.

She said that many locals had lost faith in the project given the problems they have faced over the last two years.

“Apart from the promise that [project developers] would strictly follow the recommendations [of the report], local people should have a voice in whether the project should go ahead,” she said.

For Ma Win Khaing, the daughter of Daw Khin Win, who was shot dead by police in the Dec. 22 clash, only the complete cancellation of the project would do.

“If the project still exists, we’re afraid there will be more cases like my mother’s,” she said.

—Zarni Mann contributed to this report

it

The unexpected suspension of the Myitsone dam project in late 2011 raised the hopes of many Myanmar people that a new approach to infrastructure planning may be on the horizon.

The previous military government had been characterized by opaque deals and projects that gave little regard to their impact on local communities. But under President U Thein Sein’s administration—and with the engagement of a new set of donors and companies—a new emphasis on “international standards” in infrastructure projects has emerged.

With expectations of community dialogue and consent, this is potentially a positive shift in broadening the benefits of development projects to meet community, as well as corporate, interests.

Yet there is growing evidence that the uptake of international standards may not be as much of a step forward as was hoped—even in flagship infrastructure projects such as the Thilawa and Dawei special economic zones. The days of “bulldozer consultation” may be over, but there has not necessarily been any real change in corporate accountability.

A recent survey by the Dawei Development Association in the area of the Dawei Special Economic Zone (SEZ) project in southern Myanmar found that many people who attended consultation meetings—organized by the main construction company Italian Thai Development (ITD)—felt intimidated. Their concerns were not even heard, let alone addressed.

“The only thing they told us was that the companies were on the way. We were not allowed to say what we would

like to say,” said a resident of Hsin Phyu Tine village near Dawei.

Of particular concern was the way ITD sought to portray widespread community support for the project, especially from religious leaders. Local communities complained that promotional materials in the project’s visitor center displayed—allegedly without consent—photos of ITD staff “consulting” with local monks at village meetings. To avoid future misrepresentation of their position, some local community members held up signs and banners at their next meeting stating their disapproval of the project.

In Mon State last year, Thai engineering and construction company Toya-Thai held a set of consultation meetings about a proposed coal-fired power plant in Ye Township. Yet residents of Andin village, which is close to the project site, sent a complaint letter to Toya-Thai claiming that the meetings had not provided them with sufficient information and that the company had failed to answer key questions on environmental and health issues. Even more worryingly, villagers claimed that at their most recent meeting in December, organizers bused in a group of outsiders to take part while those living closest to the project site were excluded.

Similar concerns have been raised by communities affected by the Thilawa SEZ project on the outskirts of Yangon. Last year a formal complaint was submitted to the project’s primary donor, the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA)—Japan’s development agency—on behalf of communities affected by initial project phases in Alwan Sot and Thilawa Kone Than villages. Displaced communities felt that they were pressured into signing inadequate compensation

agreements and cited poor housing and living standards, loss of income and lack of education opportunities at the relocation site.

Yet curiously, the JICA investigation into the complaint found the resettlement process had not breached any JICA principles. The complaint over insufficient compensation was dismissed because it had been negotiated through consultation meetings—a process that the community stressed was deeply flawed.

The message from JICA seemed to be that community grievances wouldn’t be considered a breach of standards as long as there was nominal consultation.

Of course new infrastructure projects can never please everyone. Even the most meaningful, inclusive and responsive engagement with communities may not yield universal consent. Yet even when projects go ahead against the wishes of some, local communities should, as a minimum, be given a say in their future—for example through input into the conditions of relocation, or reducing the health or environmental risks of projects.

Communities should also not be portrayed as being uniformly opposed to infrastructure development. It is

not always a zero-sum game between corporate and community interests. For example, while there may be vocal opposition to the coal-fired power plant project in Ye Township, communities in Dawei and Thilawa are generally open to certain elements of the planned special economic zones.

The core issue is that in all of these examples, despite there being scope for genuine dialogue, consultations were perceived by communities to be largely meaningless.

But what of other donors, such as the World Bank? With their explicit goal of poverty reduction, surely they set an example of meaningful consultation? Could they provide a

By TAMASmodel for companies and other donors in Myanmar?

Sadly the answer remains unclear. The World Bank’s US$86 million National Community Driven Development Project, approved in November 2012, has been plagued by accusations of insufficient consultation and inflexibility—especially worrying for a project with “Community Driven” in the title. And the Bank’s record in other countries in the region is patchy. So issues over consultation clearly run beyond companies such as ITD and Toya-Thai, with multilaterals and Western actors also likely falling short.

The raw use of corporate (and government) power in the planning of infrastructure projects like the Myitsone dam was plain to see. There was never any expectation of local consultation or consent and communities were forced to accept whatever compensation was offered.

The new emphasis on community consultation presents a different vocabulary and holds out a vision of “international standards” where the benefits of development may be shared more widely. Yet underneath the new clothing of international standards, the experience of many communities is not as different as we might think. Corporate and donor power—as shown in Dawei, Andin and Thilawa—can still be wielded in unaccountable ways.

Spreading the benefits of development projects so that all interests are served is crucial. Yet this will require donors and companies to do more than just tick the box of “consultation.”

Tamas Wells is editor of the Paung Ku Forum, which hosts lively conversations about development and aid in Myanmar at www.facebook. com/Paungku.

Developers and donors are big on “community consultation” ahead of large projects—but are the touted listening exercises really sincere?

WELLS

Since the 32-year-old Aung San was killed in 1947, Myanmar has suffered from a crisis of leadership. The architect of national independence left a giant hole that no one has been able to fill over the past nearly 70 years.

Even now, as the country tries to scale back from the abyss after decades of military rule, it continues to struggle in the absence of strong and visionary leadership. Myanmar seriously needs another Aung San, but there is no one close to the widely revered general.

Myanmar people still remember him as a selfless leader with integrity, whose shrewd dealings with both the British and the Japanese in the mid20th century helped Myanmar break free of imperialism and achieve independence.

Jan. 4, 1948, failed to build unity with the various ethnic groups. A coup was launched in 1962 and the military has since ruled, in various guises, without pause.

In January 1946, General Aung San said in a public speech that “No man, however great, can alone set the wheels of history in motion, unless he has the active support and co-operation of a whole people. No doubt individuals have played brilliant roles in history, but then it is evident that history is not made by a few individuals only.”

This reflected the value he placed on the participation of individual citizens in

relieved when it comes to Burma’s fate. Even in my dreams, I cry and am angry for my country as it is not independent.” If he were still alive today to witness the oppression and disunity in Myanmar, he would undoubtedly shed even more tears.

Aung San urged politicians to work for unity among all citizens, including ethnic nationalities. Otherwise, the General said, Myanmar “won’t be able to fully enjoy the essence of independence.”

He was absolutely right. Aung San always underscored the importance of unity and this led to the signing of the Panglong Agreement that enshrined equal rights and political autonomy for ethnic nationalities in 1947. But successive leaders failed to build on this legacy and Myanmar descended into civil war.

Sixty-eight years since he was assassinated by a political rival, General Aung San remains an unrivaled political figure in modern Myanmar. As his centennial birthday approaches on Feb. 13, the country will embrace grand commemorative celebrations mainly organized by the opposition National League for Democracy (NLD) party and its leader, the General’s daughter, Daw Aung San Suu Kyi.

The martyred Aung San is regarded as the father of modern Myanmar and the founder of the Myanmar Army. He is lovingly called “Bogyoke,” meaning “General” in Myanmar language.

Aung San worked for unity, equality, democracy and prosperity in Myanmar—goals that are yet to be fulfilled. Myanmar people still long for these ideals and believe that if the General had survived, the country would have evolved along this path.

His immediate successor, U Nu, the most senior member of the AntiFascist People’s Freedom League and Myanmar’s first prime minister after the country gained independence on

By KYAW ZWA MOEthe building of the country. But it was an ideal that failed to materialize. In Myanmar since independence, only a handful of individuals “made” history— the military leaders that consistently ruled the country without the consent of ordinary citizens. When individuals strived to overturn the military’s influence, they were systematically defeated. Myanmar became a failed state.

Those new generations that fought for democracy were in fact struggling to achieve General Aung San’s own aspirations. Even now, whenever protestors stage demonstrations, images of the General are frequently held aloft. When demonstrations were crushed, so too were General Aung San’s photos scattered across the streets.

Aung San once said, “I am never

Aung San said, “When we build an independent Burma, ethnic people and Bamar [Burman] must have equality without discrimination.” One of his favorite quotes, applicable for all ethnic people, was: “If Bamar get one kyat [Myanmar currency], Shan and Kachin must get one kyat respectively.”

The military leaders who ruled the country with an iron fist after 1962 failed to honor Aung San’s pledge. They undercut unity, not only with ethnic people, but also pro-democracy groups and all those who spoke out against oppression.

Aung San may be long dead but the aspirations he articulated are still as relevant as ever. If Myanmar is to realize the General’s hopes—of peace, democracy and prosperity—current leaders must create an atmosphere of collaboration with all stakeholders, including opposition parties and ethnic groups.

To work towards this, all that’s needed is the genuine political will. Otherwise the country will remain in crisis.

100 years since his birth, Aung San’s aspirations for a unified and democratic Myanmar are yet to be realized

General Aung San was a good citizen and a good leader. He was one in a million.

When I joined the army in 1944, he was already the war minister and commander-in-chief of the Burma Defence Army (later renamed the Burma National Army).

To paraphrase, he said that: there are no bad soldiers in my army, only bad captains. He meant that if leaders are bad, their followers will also be bad. If leaders are good and competent, their followers will also be good and competent.

In the past, [military men] were very unwilling to take from people. In the early days, they were told to make a request to home owners if they wished to enter a house. So people loved them and gave them food. The military then thought only about the country. Now, they seek self-interest.

The general’s death brought dark days to the country. If he had survived, our country would not have ended up as it has. He could have negotiated an agreement with his comrades.

His speeches are still relevant in the current age. When I think of General Aung San, I see clearly in my mind an honest, blunt, selfless person with moral courage.

For example, the general was not hesitant in making friends with bitter enemies.

He also said that armed organizations should not be involved in politics. He himself resigned from the military to chair the Anti-Fascist People’s Freedom League.

In the army, he offered senior positions to ethnic soldiers such as Kachin, Karen and Chin.

He set up Kachin, Karen, and Chin battalions.

Later on, battalions were formed of different ethnicities, yet most of them were comprised of Burmans. Ethnic soldiers felt their proportion of representation was very small. This undermined trust. These kinds of things should be considered again today. But if I said this in front of army leaders now I would be accused of breaking up the military.

Kyaw Phyo Tha

‘HePHOTO: JPAING / THE IRRAWADDY

General Aung San said that [Burmans] would claim back independence together with ethnic people. And he promised that we would not be enslaved by the Burmans. But later leaders did not fulfill his promises.

It is more than 60 years now since independence and we still do not have equality and self-determination. That’s why we ethnic people are fighting for a federal Union, democratic rights, equality and selfdetermination.

Successive governments did not give us a chance to solve the country’s fundamental political problems. We had no option but to resort to taking up arms as the [government] used guns to suppress our demands, rights and voices.

General Aung San’s words suggested that he had goodwill. He laid down basic political principles, but they were not applied.

Successive governments after him did not talk about solving political problems. But President U Thein Sein’s government seems willing to solve fundamental political problems, through political dialogue. This government says it intends to hold a Union-level conference like Panglong, but this has still not happened.

Internal peace is essential. Though there is a willingness to solve political problems, if fighting emerges from one side, doubts will continue to grow. It is difficult to reach a nationwide ceasefire accord as both sides’ past experiences make them doubt one another.

—Saw Yan Naing

General Aung San had qualities of a good leader; he was humble, considerate and sympathetic. On this 100th centenary, our youth should be aware that we are writing our own history and we should try to write it like the General would, or better.

He was altruistic. I admire him very much; he is someone who can give moral strength to the youth.

As an ethnic man, I respect General Aung San. Former Arakan leaders also respected him.

If he had not died, our country would have been built as he had promised. Ethnic peoples signed the Panglong Agreement because they trusted him. The 1947 Constitution emerged as a result of pledges in that agreement. However, after he passed away, provisions in the Constitution were not realized. In the view of ethnic people, Burman [Myanmar] leaders oppressed them without honoring the promises made by General Aung San.

If he had survived, he would have fulfilled his promises and our country would not have ended up like this.

The army as established by General Aung San would be one that respects people, doesn’t discriminate and gives positions to ethnicities. There are now no ethnic persons in high positions in the army.

The most important thing is the military should not intervene in politics. The military is ideally meant for national security and national defense.

Rather than organizing ceremonies to mark the 100th birthday of General Aung San, current leaders should try to build a genuine federal Union. Only by ensuring equality for all ethnicities in politics, the economy, social status and so on, can the promises made by General Aung San to ethnic people be fulfilled.

On the anniversary of General Aung San’s birth, the army should pay due respect to what he said and focus its attention on serving the interests of the people. It should be a federal army inclusive of all ethnicities. It should transform itself into one that protects diverse ethnicities from one that oppresses and kills its own national brethren.

Zarni Mann

Zarni Mann

U Pandavunsa

Buddhist monk and leading figure in the 2007 Saffron Revolution

Ialways thank General Aung San for his efforts to make our nation independent. His name has become virtually synonymous with Myanmar independence. It’s very important for all Myanmar people to remember it. Given the speeches he made in the 1940s, I have to admit that he was a visionary leader. What he said back then, about not disguising politics as religion, is still relevant today. In 1946, the General told monks that using religion purely in your own interests was a dirty tactic, and he urged the Buddhist clergy to promote lovingkindness by preaching freedom of religion. If we Myanmar people took what he said seriously, we would not have had the kind of religious problems we experienced in the past few years.

—Kyaw Phyo Tha‘His

General Aung San talked about the importance of values such as equality and mutual respect. We should think about how to realize these values today.

There was quite strong trust between General Aung San and other ethnic leaders.

They trusted him personally, and both sides had a great deal of common ground as regards the political landscape. However, as time went by, views have grown further and further apart.

Therefore, it is important that the principles that General Aung San articulated be applied now. We need to negotiate to rebuild understanding and find common ground.

I believe General Aung San would have kept his promises. That’s why we repeatedly mention the Panglong Agreement. Otherwise, we wouldn’t talk about it.

—NyeinHis history was eradicated for about 40 years and most young people don’t know his exact story. There is no one who has his exemplary morals, the morals that are very important to rebuilding our country. If he had not died early, the number of amoral people would not be as abundant as now.

He is my hero and now we live in an independent country because of his sacrifices. We are very thankful, we are proud of him and admire him.

It was only after I had engaged in politics for some time that I came to understand more deeply why General Aung San engaged in politics at a young age, why he made sacrifices and why he became the national leader.

The more I understand him, the more I respect him. He had only one aim—to claim back independence for his country. What I like about him most was when he joined hands with Japan to establish the Burmese army and then later he re-established relations with the British. It is not easy to rebuild relations with a country you’ve fought against. When the British asked whether he had joined them because they were gaining the upper hand, he bluntly replied “yes.”

It seems almost impossible that Myanmar will see a political leader like him again; one who is pragmatic, astute and has his eyes firmly fixed on his goal.

Politicians are meant to unify people and provide leadership. A politician has to show the right way when the public is wrong. If he joins the majority, though he knows that the majority is wrong, then, as the General said, he is an opportunist.

Our country is a multi-faith country. If we are to build national reconciliation, we have to unify all its elements out of love for the country. No element can be left out.

The General knew and understood this well. So not only Buddhists, but also Christians, Hindus and Muslims had a good impression of him. Whenever he spoke about different races and religions, he never spoke of good or bad. He only spoke about patriotism. That’s why all people pine for him. He never discriminated religiously. That’s what we want. That’s democracy. As a politician, I respect him, and as a Muslim, I hold him in esteem. He set an example.

Kyaw Phyo Tha

One of General Aung San’s attributes that I most respect is his long-term vision. I wish he had not been assassinated and could have provided leadership for the country.

He knew that none of the ethnic groups could be left out in rebuilding the country. He honestly thought that equality was a must. That is why he gained the support of the ethnicities and why he could reclaim independence.

His long-term vision was associated with honesty and moral courage. In our country, which is a very diverse one, honesty is a must to ensure peaceful coexistence.

We will never again see a leader like him.

He said: “You need to change your bad habits.” His words are still perfectly correct now. He knew the real situation of the country’s citizens. He foresaw what the challenges would be. He wanted to build a society in which people march in unity toward the same goal. The unity that those in power are now creating is a forced unity, which comes from the barrel of a gun and [would be] totally against the General’s desire. Therefore, we have a long way to go.

—Kyaw Phyo ThaEven as the period of history involving General Aung San is fading, elders tell the younger people about him as a bedtime story. Our country possesses many heroes like him. If we can identify these heroes, I believe it will give strength to youth.

Whenever I see his photos and read his speeches, a feeling of adoration emerges. He gave us independence. Had he not died so early, the country would be more prosperous.

In the December issue of the magazine the photo on page 38 accompanying an interview with Mi Kun Chan Non of the Mon Women’s Organization was incorrect. The correct image appears in the online version of the story, 'Movers and Shakers.' The Irrawaddy apologizes for the inadvertent error.

Birdwatchers have reported a stunning decline in wildlife at the Paleik Lake in Mandalay Region, with some suggesting that the animals are poisoned and sold in local markets.

Local avian enthusiasts said that the lake is a wintering ground for more than 20 species of migratory birds, including a rare species of wild swan. But not everyone, they said, comes to the lake to enjoy the extraordinary view.

U Thein Aung, vice-chairman of the Mandalay Birdwatchers Association, said local authorities are doing little to educate people about conservation, while low incomes are driving up incentives for illegal bird-catching.

Villagers sometimes come to the

lake to hunt for birds and then sell them as deep-fried snacks at nearby tourist attractions, such as U Bein Bridge, he said.

“Fried birds are being sold and people are still not aware that they shouldn’t eat them. Even owls are sold at U Bein Bridge,” U Thein Aung said, lamenting that the practice “affects the image of the country.”

A wildlife photographer known by his online alias, Solo Mdy, has documented some of the damage. He wrote recently on social media sites that he had seen moorhens he believed were killed by sodium cyanide, a toxic salt most commonly used in gold extraction. The poison is sometimes used to kill fish and other animals because of its high toxicity.

Solo Mdy wrote that a “boat owner showed us a bird whose neck was cut. He said that it died from sodium cyanide, locally known as ‘neck cutter’ because it cuts off the throat veins when consumed.”

Following pleas from conservationists to enforce wildlife protection measures, police and local administrators recently inspected local markets around the lake in search of illegal bird products. Officer U Zaw Win Kyaw of the Paleik Township Police told The Irrawaddy that inspectors did not find any bird meat.

U Zaw Win Kyaw added that birdwatchers themselves ought to take more preventative action by educating hunters, vendors and consumers about conservation.

“We can’t decide whether [poisoning birds] is a police issue or not. So far, we haven’t taken any action against bird hunters,” he said.

U Zay Maung Thein, a local bird watcher and nature enthusiast, said the problem is too big to be handled by people like himself, without the help of law enforcement.

“All we can do is give talks and put up posters,” said U Zaw Maung Thein. “It is simply not enough. There are wildlife protection laws and authorities have to make sure they are followed. So far, I haven’t seen them do anything to stop it.”

Iam very comfortable talking in the Myanmar language—but don’t ask me to do so with my mom. It just doesn’t feel right unless we speak in Mon, which is after all, my mother tongue.

When I’m in the company of my 86-year-old grandmother, there is no choice. My grandma speaks only Mon.

In many ways it was she I have to thank for the rewarding if complicated feelings that I—like many speakers of minority languages—have about language today.

As a very young child growing up in

Thanbyuzayat, my home town in Mon State, I spoke only Mon with my family. But by the time I reached preschool I had picked up some Myanmar from neighbors. Thanbyuzayat was originally a Mon town, but the Myanmar language was all around us. The administrative officials and school teachers were mainly ethnic Bamar, and a growing population of Myanmar-speaking migrants was arriving from the upper part of the country.

Perhaps the rising use of the Myanmar language around us was one reason my grandmother arranged

for me to attend summer courses at a nearby monastery to learn Mon reading and writing, which she had never learned herself. My grandma cannot read Mon and can write just a tiny bit of Myanmar script.

“I want you to read me the sutras in Mon,” she used to say, telling me this would help her memorize the old texts. There was always a certain atmosphere around our Mon classes. The monks told us that teaching the language was restricted, and that our classes were “unofficial,” whatever that

meant. We children just knew we were not supposed to talk about the classes openly. We could also see that there was barely any budget for the course and that the monks had to find the money somehow for our free text books.

Eventually the course, and my writing instruction, ended when I was aged 10, due to lack of support from an abbot. By then I had studied just three text books. I had started to become interested in the Mon script, but there was no more opportunity to learn.

I had also realized very early on that

I would have to focus on the Myanmar language if I wanted to communicate more widely. At school, all the teachers spoke Myanmar. I can still chant the nursery rhymes I learned there.

As I grew older, I haunted the local book rental stores, devouring cartoon books, weekly journals, illustrated stories and translated stories from the West, all in the Myanmar language.

I still had my fluent Mon, but even within my family, it was being used less. Some of my cousins had a Myanmar-speaking parent and

I just think we should value the beauty and depth of all our ethnic cultures.

Myanmar-speaking nannies. Most of them, and their children, now speak only in Myanmar. My mom says that if my siblings and I had not grown up speaking Mon as toddlers, we too would not be able to speak the language now.

That seems true, and I am happy that I learned Mon from an early age—but now I am also feeling a bit ashamed that I can’t read or write it. In some ways, in this Internet age, I am orphaned from my mother tongue.

As I began to make my way in adult life, for a time in Thailand and now in Yangon where I speak and work mainly in Myanmar and English (which I began to learn at around age 11), I found myself trying to fill in what increasingly looked like gaps in my knowledge.

I realized that from my school textbooks I had learned about neither my culture nor my history. Mon stories did not feature in my school life—how come?

I did learn that the ethnic Bamar won every war they fought with ethnicities like the Shan, the Mon, and China-based groups.

And I learned about Myanmar’s fight for independence from the British. But where were the Mon freedom fighters who were a part of that struggle? They were not in the books, or if they were, they were not identified as Mon.

As an adult, I felt I had to unlearn much of the prejudiced or partial history I had learned from the textbooks, and teach myself from other sources.

I found pride in learning that the Mon were almost certainly the first nationality in this country to believe in Buddhism and were among the first ‘‘civilizations’’ in Southeast Asia. You could say that Bagan would likely not be full of pagodas were it not for the Mon, and that the country today would likely not be majority Buddhist had the Thaton kingdom not existed.

Scholars still debate much of our country’s history and we all have a lot to learn.

But today so much of old Mon

culture and tradition has become blended into mainstream Bamar culture that even the Bamar don’t realize it.

Take Yangon’s famous Sule Pagoda. In Mon, Sule is pronounced “Jule,” a Mon word meaning “place of rest.” The pagoda reputedly got its name after the legendary Mon King Okalappa stopped there on the way to what is now the site of the Shwedagon Pagoda, where he was bringing relics of the Buddha. There are many places with names that have a meaning in Mon but not in Myanmar.

Nai Ngwe Thein, a former state education officer, told me that university students doing graduate Myanmar-language study have to study Mon in order to read the country’s old stone inscriptions. “In a sense if you don’t know the Mon language, you don’t know all the Myanmar language,” he said.

Living in Yangon now, I feel lucky to be a Mon speaker. Thanks to friends I have made at a Mon conversation

club, I have found a space where I can practice and use the language again. I feel proud to speak Mon and wear Mon traditional dress within the Bamar-dominant society in which I now live. And I feel proud of my Mon name, which is something I have to try to live up to; it means cultured, or well-mannered.

I feel there is something special about being a Mon and speaking my own language with its long history and which has meanings that don’t exist in any other language.

One gripe—I don’t like when Bamar people make fun of Mon people speaking the Myanmar language in a Mon accent. I know that speakers of dominant languages around the world often act in this way toward those with “regional” or “country” accents or tongues. But I sometimes wonder if Bamar are not just jealous that we speak an extra language!

I have never felt animosity toward Myanmar people over the imbalances that exist in relation to this country’s history, languages and cultures. I don’t want to accuse anyone of anything.

But a bit of rebalancing and

recognition would be appreciated. I am sure that people from other ethnicities feel similarly. I just think we should value the beauty, richness and historical depth of all our ethnic cultures and languages.

Many people in Mon State are now afraid that their children will not value the language, or be able to speak it, given the huge exposure they have to

Myanmar, which many young people also see as more useful. Even my sister has to make an effort to speak Mon to her one-year-old child as they are surrounded by Myanmar-speakers.

I am not sure how many Mon speakers we have within the roughly two-million population of the state. I do know we have very few people who can write the language well, and most of those are monks.

Myanmar is the language of governance and official life in the state. Most signposts are in Myanmar, though there are now a few in Mon also. Public announcements are generally in Myanmar. Even when people go about on the weekly request for religious donations, fewer now use Mon.

But it has been inspiring to find out that language and education experts both here and around the world have shown the great benefits of children learning first through their home language or mother tongue—and that this viewpoint is now dominant.

Kimmo Kosonen, a Finnish senior language consultant at Payap University and SIL International said

that educators now understand that children who do not learn in their home language often struggle to reach their full potential.

U Harry Htin Zaw, a researcher with the Shalom Foundation, said children should be allowed to learn in their first language. “If we don’t recognize their language, we might be giving a message to the child that ‘your language is not important.’ The child might feel belittled,” he said.

Ethnic children who have to learn in Myanmar have extra difficulties, U Htin Zaw said. “A Bamar child may struggle with a subject when she or he starts school, while an ethnic child may have subject and language difficulties.”

Nai Ngwe Thein, a former state education officer, told me that when he worked in Kachin State in the mid1990s, there was a high school dropout rate due to children not understanding lessons in the Myanmar language.

Myanmar’s education system is now undergoing reforms, but as yet there is very little implementation of mother tongue-based multilingual education. I hope this changes soon, because I think this is one way to ensure equal treatment and opportunities for all citizens and cultures.

That’s my dream; in my mind’s eye I see a time when every ethnic child will be able to come home from school and read their own culture’s nursery rhymes, poetry and stories to their parents.

I dream that I may read the Buddhist sutras in Mon to my grandma before she dies. I fear I cannot really make this happen. But even if it doesn’t, I know that she and I both treasure our talks together in our own language, in what little time we have.

I might speak English at the office and Myanmar on the streets, but when I want to truly express the person I really am, only Mon will do.

International Mother Language Day on February 21 promotes linguistic and cultural diversity and multilingualism. It was first announced by UNESCO in 1999.

Many people are now afraid that their children will not value the language.Mon books on display during Mon National Day celebrations in Yangon last year Irrawaddy

TRADE: Crackdown against smugglers

By KYAW HSU MON / YANGON

By KYAW HSU MON / YANGON

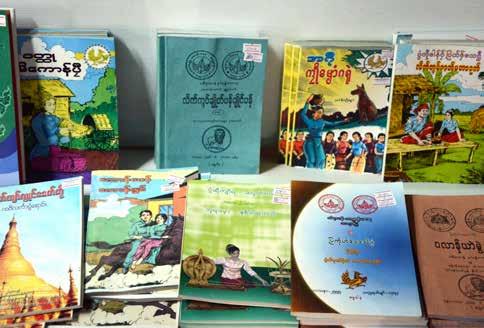

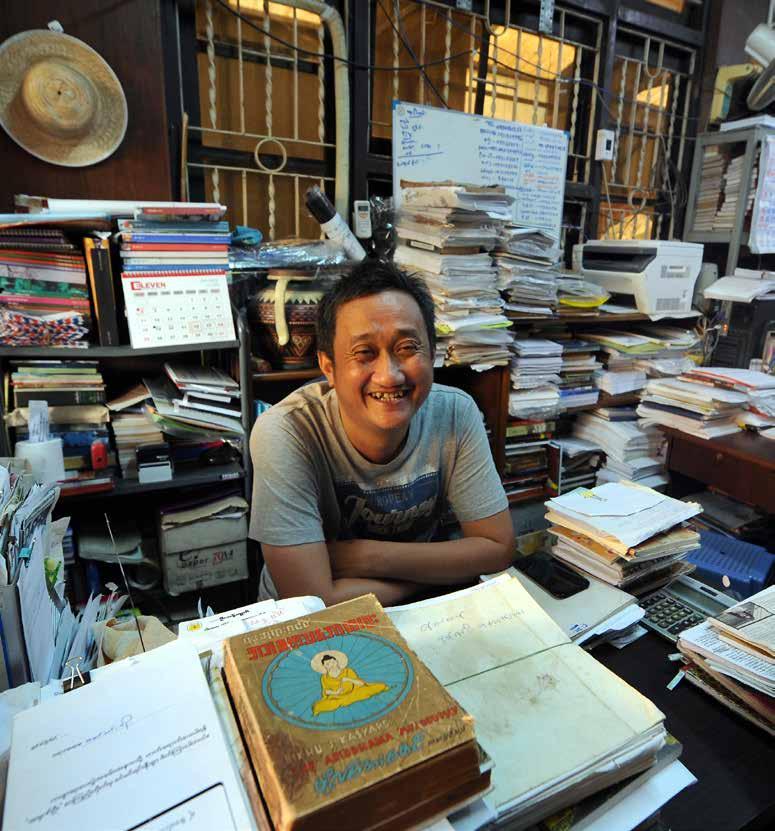

In a changing media landscape, book publishers in Myanmar are trying to stay ahead of the curve. Although overall book sales in the country have declined in recent years, an appetite for reading remains strong. U San Oo, the owner of Seikku Cho Cho publishing house, spoke with The Irrawaddy’s Kyaw Hsu Mon on all things books—from best-sellers to translations and why e-books are a welcome development.

When did you start your publishing house and what kind of books did you publish at that time?

Our first book was published in 1999. I came to Yangon a year earlier after I had finished working in my native town. Some of my friends were publishing journals and magazines in Yangon and I contacted them. I first worked as a designer at Tet Lan sports journal. At that time, there were no designers because there were no computer design systems, so I worked by hand. I was also a member of the editorial team. After saving some money, I decided to start publishing books. The first book published was by the economist Khin Mg Nyo. It was a small book of business quotations. Since then, I have published popular books which make money, as well as literature. Now my publishing house business has grown and found a place in the market.

To be honest, I didn’t really understand the book market in the early stages. But I decided to publish classic books, not out of business interest, but because I wanted these books to be available on the market. Some books have made good profits while some have not. Sometimes stock has remained in the warehouse.

The Forever Media group contacted me in 2000 and asked me to open bookshops with them. They wanted to create a new e-books market through these bookshops. So I worked as a publisher and at a bookshop at the same time. I got the chance to know what books people like and what I needed to publish for them. After that, I was able to publish many books that people liked and the business grew.

Which category of books are best sellers at the moment? Fiction? Political books?

Many of our published books are not immediately popular on the market. But I always choose titles that will be useful for readers. The recent bestselling categories are political books, about, for example, the experience of political prisoners, as well as books about well-known people—with either a good or bad image—in the political field. Then there is Myanmar literature, for example the author Juu. Her book sales are still strong. But for those kinds of books, most of them are selfpublished.

What percentage of recent book sales are political books?

It is hard to say exactly as we don’t have an accurate survey at the moment. But I think at least 30 percent of total book sales recently [have been political books].

How is Seikku Cho Cho performing at the moment?

I don’t have a market survey to compare with other publishers. But we are wellplaced in the market and continue to publish many books. Normally we publish about 20 books per month.

What is the current situation for translated books?

There is a good market for translations, but the number of new translators is not increasing. Therefore it has been hard to introduce new translations to the readers. That’s why old translations of books, written by old authors, are still among the best-sellers. This is not only the case in our country, it has happened in other countries also; classics are always on the book shelves. The sales

are always good. Authors’ associations are considering the issue of a lack of new translators. The main requirement is to nurture new and talented translators here.

Who are the best sellers in the classics category?

The top classic books are by Mya Than Tint, Mg Tun Thu, Dagon Shwe Myar, Shwe Ou Daung, then Mg Moe Thu, Tin Nwe Maung and Soe Thein. Their masterpieces are still performing strongly.

How would you assess the publishing market over the last 20 years?

There are many ways to evaluate the market. Lately, sales are declining. In

the past, publishers could publish at least 3,000 to 5,000 copies of a first edition of literature or other books, and all stocks could be sold within one month with nothing left in the warehouse. But now, we start by publishing only 500 to 1,000 copies of new books, and even if they sell out we don’t dare to consider publishing them again. We have to seriously consider whether to publish certain books. From this point of view, the market is declining, but on the other hand, there were not so many different categories of books in the past. There are many now, including technical books. In that regard, the situation has improved.

I think 20 percent of sales are due to a good cover design […] That’s why in

the international book market, you will see various kinds of appealing cover designs available. They are seriously focused on the overall book design as well. That’s what the market wants. But locally, we publishers are still facing a lot of difficulties. If we can’t get the best quality paper, we can’t produce the best quality books. So we haven’t been able to produce as many quality books as we would have liked in recent times.

How have e-books affected the hardcopy market?

The number of e-book readers grew after 2013 because more young people are using smart phones, tablets and other electronic devices. They read books on these devices. It is a threat to hardcopy publishers here, but what

we believe is that Myanmar people need to read more books, in any way. Though it might become a major threat to us one day, we welcome people reading books in any form. In other countries, people are reading books on their electronic devices on their way to or from the office […] and at the same time, our people are also [starting to] read on e-devices. It’s an improvement.

How do you see the future of the publishing industry over the next 20 years?

I can accept whatever happens in the future as a publisher. But as a book lover, I believe the book market will not disappear quickly. If people acquire the taste for reading books, they will not let it go.

Official teams are seizing everything from illegal gemstones to timber and wildlife, but ineffective laws, weak enforcement and corruption mean underground trade flows still flourish

By KYAW HSU MON / MUSE, SHAN STATEMobile government teams tasked with curbing smuggling along the Myanmar-China border near Muse have seized illicit goods, including gemstones, timber, wildlife and precursor chemicals, with an estimated total value of US$27 million in the past two years, according to Ministry of Commerce officials.

U Yan Naing Tun, deputy director general of the ministry’s commerce and consumer affairs department, said mobile teams had set up checkpoints and conducted surprise checks on the road to the Muse-Jiegao border crossing and other known smuggling routes in northern Shan State to seize unregistered goods on cargo trucks on their way to and from the MyanmarChina border.

“Smuggled jade and jewels are the largest number [of goods] that we have seized in the past two years. These are going to China via Muse border areas, but smugglers weren’t going through the border checkpoints, they used other ways around the checkpoints,” he told The Irrawaddy.

U Yan Naing Tun said 600 officials had formed several teams—comprising officials from the ministry, the Customs Department and police officers—that seized smuggled jade and rubies worth $3.8 million.

He said illegal timber, forest

products and wildlife were also being smuggled out of Myanmar on a large scale, with officials seizing various kinds of hardwood and luxury timber. Goods smuggled from China into Myanmar included textiles, tobacco, alcohol, electrical appliances such as mobile handsets, and precursor chemicals used in illegal drug production in Shan State.

“More than 10,000 logs of various kinds of timber have been seized within two years,” said U Yan Naing Tun, adding that 11,000 kilograms of precursor chemicals were confiscated on their way from China into Myanmar. Seized goods were later auctioned by the ministries involved in the antismuggling operations.

He added that the mobile teams inspected cargo on trucks while police teams conducted the search for illicit drugs, such as opium, heroin and methamphetamine, being trafficked from Myanmar to China.