FEATURE:

WORKERS WAIT FOR A BREAK

ECONOMY: POLICY CHANGE –TOO FAST OR TOO SLOW?

TIME OUT: YANGON RIVER CRUISE

FEATURE:

WORKERS WAIT FOR A BREAK

ECONOMY: POLICY CHANGE –TOO FAST OR TOO SLOW?

TIME OUT: YANGON RIVER CRUISE

The Irrawaddy magazine has covered Myanmar, its neighbors and Southeast Asia since 1993.

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Aung Zaw

EDITOR (English Edition): Kyaw Zwa Moe

ASSOCIATE EDITOR: Sandy Barron

COPY DESK: Neil Lawrence, Paul Vrieze, Samantha Michaels, Andrew D. Kaspar, Simon Lewis

CONTRIBUTORS to this issue: Kyaw Zwa Moe; Aung Zaw; Samantha Michaels; Simon Lewis; Simon Roughneen; Neil Lawrence; Nyein Nyein; Kyaw Phyo Tha; William Boot; Zarni Mann; San Yamin Aung; Grace Harrison; Kyaw Kha.

PHOTOGRAPHERS : JPaing; Steve Tickner

LAYOUT DESIGNER: Banjong Banriankit

SENIOR MANAGER: Win Thu (Regional Office)

MANAGER: Phyo Thu Htet (Yangon Bureau)

REGIONAL HEADQUARTERS MAILING ADDRESS: The Irrawaddy, P.O. Box 242, CMU Post Office, Chiang Mai 50200, Thailand.

YANGON BUREAU : No. 197, 2nd Floor, 32nd Street (Upper Block), Pabedan Township, Yangon, Myanmar. TEL: 01 388521, 01 389762

EMAIL: editors@irrawaddy.org

SALES&ADVERTISING: advertising@irrawaddy.org

SUBSCRIPTIONS: subscriptions@irrawaddy.org

PRINTER: Chotana Printing (Chiang Mai, Thailand)

PUBLISHER LICENSE : 13215047701213

20 | Society: Myanmar Workers in Thailand Still Toiling in the Shadows

Exploitation remains a fact of life for many

24 |

Politics: Myanmar, North Korea and Unintended Consequences

Myanmar’s rulers have released a torrent of reform that can’t be reversed, says a respected expert on the country

26 |

Culture: Hsipaw Haw: Final Abode of a Tragic Shan Prince

A long-neglected palace in Shan State stands as a monument to one of the first, and most illustrious, victims of military rule in Myanmar

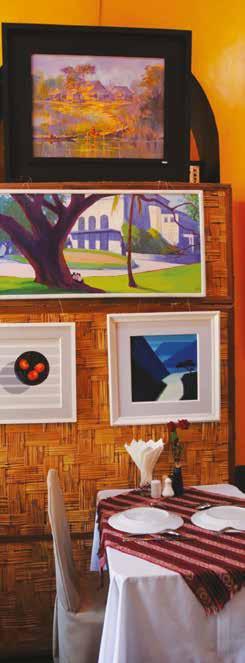

30 | Society: Bon Appétit!

Yangon’s street food can be a real treat, but much on offer isn’t particularly safe to eat

|

As Myanmar opens up, a spotlight shines on the need to address the shortage of women in public life

50 | COVER For Progress on Peace, Women Are Key BUSINESS

32 |

Economy: ‘What’s the Rush?’

36 |

Reforms: ‘Go Easy on Us’

Myanmar officials ask for patience from would-be investors, as the pace of reforms continues to disappoint

40 | Roundup: UK Freight Firm Backs New Search for ‘Buried’ Spitfires

Over the past two and a half years, Myanmar has made unprecedented progress toward ending its long history of civil conflict. During the same period, however, fighting has resumed between the government army, or Tatmadaw, and the armed wing of the Kachin Independence Organization (KIO), demonstrating that a permanent peace is far from assured.

Recently, The Irrawaddy’s Lin Thant had a chance to speak to Maj-Gen Gun Maw, the deputy chief of the Kachin Independence Army and a key negotiator in talks with the government and Tatmadaw, about what the country’s ethnic armed groups hope to achieve in the ongoing peace process—including their vision of a more inclusive federal armed forces, which many see as central to ending endemic armed conflict in Myanmar.

China has been very involved in the peace process, especially in matters related to ethnic armed groups based along the MyanmarChina border. What role does China play between the KIO and the Myanmar government?

Kachin State and the Kachin people have always had strong ties with China, because there are Kachin people on both sides of the border, and this is something that can’t be changed. There are also things that bring Myanmar and China together, including border trade, so they can’t be separated either, since they are neighbors. However, Beijing’s relationship with the KIO is very different from its ties to the Myanmar government. It doesn’t communicate with or provide assistance to the KIO directly. Nor has it pressured the KIO, so far.

But didn’t China push the KIO to engage in ceasefire talks with the Myanmar government?

The KIO and other ethnic groups say they want to transform the Tatmadaw into a federal army. How do you propose to do that?

We haven’t reached the “how” stage yet. What we want is a Tatmadaw that includes all nationalities, because we all live in this country together. That’s why we are calling for a Federal Union Army. But how to transform the current Tatmadaw is something that we have to discuss with everyone concerned.

The role of the Tatmadaw is very important and we can’t eradicate its history, which began with Myanmar’s independence struggle. The structure of the future federal Tatmadaw will be different from that of the existing one, but that doesn’t mean that we are going to destroy it and replace it with something new. The main thing is how we will transform and participate in it.

The government has called on the KIO to submit a list of all its members, as well as figures detailing how many weapons it has and how much ammunition. It also wants you to stop building new camps and recruiting new soldiers. What is your response to this?

It depends on the code of conduct, which both the government and the ethnic armed groups have to adhere to. For example, if the government tells the ethnic armed groups not to recruit new soldiers, it also has to create conditions under which they will not need to do so.

It will be impossible for us to stop recruiting if fighting continues and we are still under repression. We have to prepare for coming battles. But if the government created conditions conducive to improving the situation, we are ready to do our part.

A ceasefire is important for China’s interests because clashes between the KIO and government troops mainly take place in border areas adjacent to China. So whenever fighting breaks out on our side of the border, it causes problems on their side. Consequently, China asked the KIO not to engage in battles in these areas. But we have also heard that they made the same request to the government. So I don’t think we can consider such acts as pressure.

What do you think of the peace process in Myanmar today?

We see it in a positive light. Before, it was difficult for both parties to meet in person, but now we can meet often and build up greater understanding. The government and ethnic armed groups have been able to share their positions on each other, which is a good sign.

Many Kachin people have been critical of Daw Aung San Suu Kyi. What is your opinion, or the KIO’s opinion, of her?

Kachin people started criticizing Daw Aung San Suu Kyi after armed clashes erupted again in our land in June 2011. Before that, all Kachin people spoke of her in very positive terms. They also put a great deal of hope in her, so when, because of the political situation she was in, she didn’t show as much sympathy for them as they had expected, they were very disappointed.

The leaders of the KIO have always regarded Daw Aung San Suu Kyi as a capable and competent leader. When we get to the point that we start talking about issues related to the whole nation, she needs to be included. Other prominent individuals have to be there as well. Some people within the country and in the international community seem to think that she will be able to resolve all ethnic issues, but I would say that the ethnic nationalities won’t entrust their fate to her. Instead, they will join hands with her in finding solutions.

What do you think about the role of U Tay Za (chairman of Htoo Companies) in Kachin State, where he is said to have acquired a large amount of land for businesses ranging from mining to resorts?

I recently met him in Yangon, where I asked him to provide information about his business activities in Kachin State. He said he would. When we know more about how these activities will affect our people, we can discuss this with him. We welcome businesspeople who can contribute to the well-being of our people. But we have to speak out against anything that hurts their interests.

As far as we know, U Tay Za is currently engaged in mining, including gold excavation and small-scale copper mining, and logging in our land. We’ve heard that he has acquired a lot of land in the Putao area. When we asked him about this, he said that while doing business there, he will also focus on environmental conservation. So we need to know if he will keep his word on this.

What is the KIO’s position on the Chinese-backed Myitsone Dam project, which the government suspended in September 2011?

We wrote an official letter to both Snr-Gen Than Shwe and the Chinese government rejecting the construction of the Myitsone Dam after the project was first reported. The Myitsone area is historically important for local people, and is also the life line of the whole country. That’s why we opposed it. We still hold that position.

Some have accused President U Thein Sein and the Myanmar

You’ve noted that the Tatmadaw has played a central role in Myanmar since the days of the country’s independence struggle. At the same time, it has been accused of committing countless human rights violations over the years. How can these two—the Tatmadaw as a central institution, and the Tatmadaw as a serial violator of human rights—be reconciled?

From the time of the independence struggle until state power was seized by Gen Ne Win’s Revolutionary Council, there were Kachin, Kayin, Kayah, Chin,

Peace Center (MPC) of engaging not in a peace process but in a “peace business” that seeks to exploit ethnic groups. What are your thoughts on this?

There may be problems with the way the process is being implemented, but we don’t interpret these problems in the way that you described. There are several peace-making committees involved in this process, but to be frank, from the KIO’s point of view, the MPC is the body that is really working.

Mon, Rakhine and Shan people in the Tatmadaw. So we can say that historically, the Tatmadaw was a product of the efforts of all ethnic nationalities.

However, the role of non-Burman ethnic groups gradually declined after the Revolutionary Council took over. After this, members of ethnic minorities couldn’t even reach the level of mid-ranking officers. In the future, the Tatmadaw shouldn’t be like this. If it is reformed, its positive role can be restored.

PHOTO: JPAING / THE IRRAWADDYOnward march

—Former political prisoner Min Zayar of the 88 Generation Students group, calling on government leaders to take responsibility for past rights abuses, to help avoid any repetition in future.

—U Soe Win, a descendant of the last reigning Myanmar monarch, King Thibaw, on the family’s desire to restore parts of the Mandalay Palace.

“I’m concerned our military-to-military [engagement] is moving too quickly, because they feed off this prestige.”

—US Democratic Rep. Joe Crowley of New York, speaking at a hearing of a House panel that oversees United States foreign policy toward East Asia.

“As royal family members, we should maintain the Golden Palace… some parts are in really terrible condition.”

“An apology must be made to all citizens.”

Another New Year is upon us, and now that we have just ended our first full year of operations in Myanmar, the moment seems right to express our gratitude to all of you for your support in these exciting and challenging times.

Since we opened our office in downtown Yangon in late 2012, we have been busy settling in with the help of our colleagues, both old and new. But we wouldn’t have been able to make it this far without our steadily expanding readership. Your interest and encouragement are crucial to our efforts to help establish a strong foundation for independent, reliable journalism in Myanmar.

Over the past year, we have received many visitors at our office, all of whom have expressed real satisfaction at seeing us here after so many years abroad. For more than two decades, we have worked to produce quality reporting on Myanmar, and the fact that we can now do so inside the country has been hailed by many as a sign of how far we as a nation have come.

Since The Irrawaddy was established in 1993, we’ve been fortunate to have a strong following among a disparate audience that includes the Myanmar diaspora, business and political leaders in Southeast Asia, legislators and policy makers in the West, and anyone else with a strong interest in Myanmar affairs.

Until very recently, however, there was one audience beyond our reach: readers inside Myanmar.

There were a few exceptions, of course. One leading Myanmar businessman involved in the energy sector told me that he used to smuggle

copies of the magazine into the country to share with his colleagues. This was, he noted, at a time when possession of the magazine would have landed him in prison.

“But now I can subscribe! It’s legal!” he said with a broad smile, waving a copy of the latest issue.

My sense now, after many meetings with government officials, ethnic politicians, military generals, lawmakers and activists, is that they all welcome us as a credible voice on what is happening in Myanmar today, whether they agree with our editorial stance or not.

My personal take on Myanmar’s ongoing transition is that, while clearly limited in scope and very much a topdown process, there is greater potential today for genuine reform than at any other time in our country’s recent history. It makes sense to remain wary, but at the same time, we have to grasp this opportunity to build a better future for all our citizens, free from oppression, war and poverty.

Wedged between the world’s two most populous nations, Myanmar is of great strategic interest to many powerful countries. As we strive to take our place in the community of nations, we must show that we have strengths of our own, which derive not from the use of military force or the exploitation of resources, but from the vast potential of our people.

This year, for the first time in many decades, Myanmar will assume a position of leadership on the international stage as chairman of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations. This will be our chance to demonstrate not only our ability to work together with other countries, both East

and West, but also to formulate an independent foreign policy that serves our own interests, in harmony with those of others.

As a media organization, The Irrawaddy is proud to play an important role in monitoring Myanmar’s emergence as a modern nation, so that our fellow citizens can better understand, and ultimately influence, the direction that we take into the future.

As we begin another year, we sincerely hope that 2014 will bring Myanmar closer to its longcherished goals of peace, prosperity and democracy. And with you as our partners, we believe that all of these things are well within reach.

Happy New Year to you all!

Last year got off to an unpromising start, suggesting that 2013 would be an unlucky year for Myanmar, indeed. The simmering conflict in Kachin State intensified late in 2012 and came to a boil early in the New Year. No sooner had that died down than communal violence that had begun in Rakhine State the previous year flared up again, this time spreading to other parts of the country. Meanwhile, opposition to a controversial mining project in Sagaing Region continued, despite Daw Aung San Suu Kyi’s efforts to assuage the concerns of those affected.

In the middle of the year, Myanmar’s quasi-civilian government hosted its largest international gathering to date: the World Economic Forum on East Asia. A few

The year began as the previous year had ended— with conflict in Kachin State, where government forces continued an offensive against Kachin rebels that started on Christmas Day 2012.

On Jan. 19, the Tatmadaw, or government armed forces, unexpectedly declared an end to air strikes against Laiza, headquarters of the Kachin Independence Organization (KIO), after securing control of a nearby army outpost. However, the fighting showed no signs of abating, even as the government was hosting a major meeting in Naypyitaw with international donors, including Western governments, the United Nations, and the World Bank. On Jan. 29, two more civilians were killed by Tatmadaw artillery fire in the village of Mayang, adding to the three killed by an attack on Laiza on Jan. 14.

By early February, the worst of the fighting had died down, but subsequent talks held through the year failed to result in a ceasefire agreement. By the end of 2013, there were estimated to be around 100,000 Kachin civilians displaced by the conflict that began in June 2011, most sheltering in KIOcontrolled areas.

A bloodied K11 assault rifle leans against the wall of a trench dug by Kachin rebels defending an outpost against a Myanmar army offensive on Jan. 20, 2013.

months later, the country took another step toward national reconciliation, with the first major public commemoration of the pro-democracy uprising of 1988, held on the 25th anniversary of that turning point in modern Myanmar history. On the ethnic conflict front, progress was slower in coming, but late in the year, another milestone was marked with multilateral talks held in Myitkyina, capital of Kachin State.

The year ended on a high note, as Myanmar played host to the SEA Games for the first time since 1969. With a difficult year over, the country was now ready to face its greatest challenge since returning as a key player on the regional and international stage: its chairmanship of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations in 2014.

Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, the leader of the opposition National League for Democracy, faced unprecedented criticism in 2013 for her handling of a number of contentious issues.

Already losing popularity among ethnic minorities for her silence on the intensifying Kachin conflict, her reputation as a rights defender took a further beating in March after a commission led by the democracy icon recommended that the controversial Chinese-backed Letpadaung copper mine in Sagaing Region be allowed to go ahead despite local opposition.

Internationally, critics faulted her for not speaking out against the persecution of Rohingya Muslims in Rakhine State—although an interview with the BBC in October, in which she emphasized that Buddhists in the state also lived in fear of communal clashes, gave her a boost back home.

Despite these controversies, however, she continued to collect accolades around the world, and in late March sat in the front row at an Armed Forces Day ceremony, signaling her greater acceptance by the generals who were once her jailers.

Violence between Buddhists and Muslims, with the latter bearing the brunt of attacks, continued in 2013, following the outbreak of deadly communal clashes in Rakhine State that began in June 2012.

Unlike the earlier violence, which involved Rohingya Muslims, a group regarded as non-citizens under Myanmar’s 1982 Citizenship Law, the riots that broke out in 2013 were more broadly directed at Muslims in areas across the country.

The first incident occurred in Meikhtila, in central Myanmar, on March 20. An altercation between a Muslim shopkeeper and a Buddhist customer angered local Buddhists, who were further outraged after a Buddhist monk was doused in petrol and burnt alive by Muslim youths. In the end, 40 people were counted among the dead, including 32 students and four teachers at an Islamic school.

Anti-Muslim riots soon spread to Bago Region, and over the ensuing months, separate incidents claimed lives and left many homeless in Okkan, Yangon Division; Lashio, Shan State; Kanbalu, Sagaing Region; and Thandwe, Rakhine State.

The spread of the violence coincided with the rise of the Buddhist nationalist 969 movement, whose most outspoken leader, U Wirathu, earned notoriety as the “Face of Buddhist Terror” on the cover of Time magazine.

Two years into its transition to quasi-civilian rule, Myanmar had a chance in 2013 to showcase its reforms as host of the World Economic Forum on East Asia. Although the official theme of the forum was “Courageous Transformation for Inclusion and Integration” and President U Thein Sein shared the stage with the prime ministers of Laos and Vietnam at the opening ceremony on June 6, the focus was very much on the host country.

The event attracted business leaders and policy makers from around the world, and the mood was generally upbeat a month after consulting group McKinsey & Company released a report predicting that Myanmar’s economy could more than quadruple in size by 2030, to US$200 billion. However, other observers also noted more sobering realities: “It’s a country where still 26 percent of the population live in poverty [and] 37 percent are unemployed,” said Sushant Palakurthi Rao, head of Asia for the World Economic Forum, adding that much improvement was needed in education, health care and job training.

Opposition leader Daw Aung San Suu Kyi echoed these sentiments, saying after the forum concluded that job creation should be the country’s top economic priority. She also warned that the lack of rule of law in Myanmar might also discourage investors from coming to the country.

President U Thein Sein sits between Vietnam’s Prime Minister Nguyen Tan Dung, left, and Laos’ Prime Minister Thongsing Thammavong during the opening ceremony of the World Economic Forum on East Asia in Naypyitaw on June 6, 2013. PHOTO: REUTERS Nationalist Buddhist monk U Wirathu is greeted at a monks’ conference in Yangon in June 2013.Twenty-five years after the people of Myanmar rose up in massive nationwide protests against military rule, the former student leaders of the nascent pro-democracy movement that took shape on Aug. 8, 1988, held their first large-scale public commemoration the events of that tumultuous year. For three days, 88 Generation activists and others, including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, ethnic Shan leader Khun Htun Oo, President’s Office Minister U Aung Min and U Htay Oo of the ruling military-backed Union Solidarity and Development Party, gathered to remember the estimated 3,000 people killed and many others who suffered in the struggle to restore democracy in Myanmar.

In his monthly radio address on Sept. 1, President U Thein Sein hailed the event as a major step toward healing the wounds of the past. “The 88 people’s movement Silver Jubilee held early last month commemorates an important movement in our political history,” he said. “The fact that we can celebrate this event together shows us that we are moving toward a new political culture where those who ‘agree to disagree’ can still work together.” Later that month, he met the 88 Generation leaders for the first time.

His message was marred, however, by the fact that on Aug. 9, charges were laid against the leaders of an unauthorized march through three townships in downtown Yangon.

It was an important moment in Myanmar’s long history of civil conflict, but in the end, a meeting between representatives of the government and armed forces and many of the country’s ethnic armed groups in the Kachin State capital of Myitkyina failed to achieve a breakthrough. In a joint statement released on Nov. 5, the two sides said that they shared the goal of reaching a nationwide ceasefire and engaging in a political dialogue, but their draft proposals for continuing talks made clear that irreconcilable difference remained. While the government army, or Tatmadaw, called on the ethnic militias to end their armed struggle, the armed groups said they wanted to see the formation of a “federal army” that better reflected Myanmar’s ethnic makeup.

The meeting in Myitkyina came immediately after a gathering of ethnic leaders in the Kachin Independence Organization (KIO) stronghold of Laiza, where they sought to work out their own common stance for negotiations with the government. Much of the debate centered on whether the priority should be to reach a nationwide ceasefire or hold a political dialogue. All parties generally agreed, however, that they favored a form of federalism— something the Tatmadaw has long opposed.

The SEA Games, which bring together the best athletes from around Southeast Asia, were held in Myanmar for the first time in 44 years from Dec. 11-22. Although the event was hailed as another important step in the country’s return to normalcy after decades of international isolation, it was not without controversy. Even before the games started, some participants complained that the host had selected sports that played to the strengths of local athletes, including some that were little known elsewhere.

The opening of the games also stirred mixed emotions, with many taking genuine pride in the spectacle, while others criticized what National League for Democracy MP U Min Thu described as a “Beijing-ized ceremony” reminiscent of the Olympic opener held in the Chinese capital on Aug. 8, 2008. China’s oversized involvement in the games, which included sending 700 coaches, managers, stage designers, technicians and other experts, and US$33 million in financial support, was seen by many as Beijing’s way of enhancing its soft power in Myanmar, where resentment of Chinese-backed megaprojects remains strong.

Despite these controversies, however, the successful completion of the games provided a much-needed boost to the country’s self-image, and set the stage for the even greater challenges Myanmar is expected to face in the future, as it raises its international profile.

Questions were raised about Myanmar’s readiness to chair the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (Asean) in 2014 after anti-Muslim violence broke out again in Rakhine State while President U Thein Sein was attending a meeting of the regional grouping in Brunei in October. Despite this incident, however, the chairmanship was officially handed over to Myanmar at the conclusion of the meeting, marking the first time that the country would lead the bloc since joining in 1997.

Besides concerns about ongoing human rights issues in the country, many observers expressed doubts about Myanmar’s capacity to host some 1,100 meetings during its term as chair, given its well-known lack of basic infrastructure. At the meeting in Brunei, Foreign Minister U Wunna Maung Lwin sought to dispel those doubts. “We’ve been preparing for this chairmanship for quite a while,” he said. “It will not be a struggle for us.”

His regional colleagues also seemed optimistic, not only about Myanmar’s ability to deal with the logistical challenges of assuming a leadership role, but also the impact this role would have on the country’s transition to a more democratic form of governance.

“I am convinced that the Myanmar chairmanship of Asean will provide additional momentum to lock in the reform efforts that are already underway,” Indonesian Foreign Minister Natelagawa told The Irrawaddy.

The opening ceremony for the 27th Southeast Asian Games in Naypyitaw on Dec. 11, 2013. PHOTO: JPAING / THE IRRAWADDY President U Thein Sein receives the Asean Gavel from Brunei’s Sultan Hassanal Bolkiah during the closing ceremony of the 23rd Asean Summit in Bandar Seri Begawan on Oct. 10, 2013.

Myanmar sports fans and athletes were in high spirits as the country hosted the SEA Games in late 2013. The last time Myanmar hosted an Asian sports meet was in 1969, too long ago to be remembered by most of those attending last month’s event. For many attending their first-ever regional games meet, the occasion also signalled hope for a brighter, more open future. Here, fans of Myanmar’s men’s football team cheer on their team at Yangon’s Thuwanna Stadium, where they beat Cambodia 3-0.

that resulted in decades-long prison sentences. Both military and civilian courts were forced to do the bidding of the DDSI.

MI units infiltrated almost every organization in the country and maintained networks of spies in almost every neighborhood. Their agents were placed in customs, immigration and police departments, and MI officers even monitored other senior military officials, including top generals.

By KYAW ZWA MOEWho should I apologize to?” This was the question that U Khin Nyunt, Myanmar’s former spy chief, barked at a reporter who asked him if he was responsible for the treatment of thousands of dissidents by units of his Military Intelligence (MI) after the armed forces seized power in 1988. Rather than countenance any suggestion that he was guilty of crimes against Myanmar’s citizens, the ex-general insisted that the real criminals were those opposed to military rule. “They were guilty and that’s why they were punished according to the law at that time,” he said.

Who, then, should answer for all those thousands of political activists who spent years languishing behind bars? Who was responsible for their torture in interrogation centers and the deaths of so many who succumbed to mistreatment and neglect in Myanmar’s primitive prisons? Who

was it that created and controlled a vast information-gathering apparatus that made every citizen feel like a prisoner?

Of course, the whole system that was in place during the long years of military rule was oppressive. But if we confine ourselves to answering just these few questions, the number of people who can be held culpable will be relatively small.

Dozens of MI units harassed, intimidated and detained opposition activists and others regarded with suspicion by the former junta. All of these units reported directly to the Directorate of Defense Services Intelligence (DDSI). And the head of this feared organization was Gen Khin Nyunt, who rapidly rose to prominence after the 1988 coup, becoming the third-most powerful member of the ruling military council.

From 1988 until his purge in 2004, Gen Khin Nyunt oversaw the arrest of around 10,000 people. Many were subjected to torture and farcical trials

But the main targets of the police state within a state that Gen Khin Nyunt created were the country’s dissidents. “Lt-Gen Khin Nyunt was trying to destroy the [National League for Democracy] by having local authorities intimidate party members, harass their families, and incarcerate those who refused to resign. The intention was to isolate Aung San Suu Kyi and reduce her party’s legitimacy,” anthropologist Christina Fink wrote in her book “Living Silence,” published in 2001.

Now a civilian who regards himself as a victim of the former regime—he was sentenced to house arrest after his ouster in October 2004, and released in January 2012—U Khin Nyunt continues to downplay his former role.

Last October, respected dissident U Win Tin met the former general who was once his jailer. “Let bygones be bygones,” U Khin Nyunt told the NLD cofounder, who spent nearly 20 years behind bars for advocating a peaceful return to democratic rule.

Recently, I had a chance to speak with U Win Tin about his experiences in prison. He told me that when he was interrogated in July 1989, his captors put a hood over his head and punched him repeatedly in the face. Even after almost all of his teeth fell out and he had trouble eating, he was denied treatment.

“Those guys went overboard,” said the 84-year-old, who is still active as a senior member of the NLD.

Asked what he thought about U Khin Nyunt’s provocative question, he had no trouble providing an answer: “I’ll tell you who he should apologize to. He should apologize to former political prisoners, their families and the whole country.”

Since 1988, at least 160 political detainees have died in custody in Myanmar, including 10 who died while being interrogated, according to the Assistance Association for Political Prisoners. Among the dead are wellknown writer U Thaw Ka, veteran politicians U Sein Win and NLD MPelect U Tin Maung Win, and student activist Ko Thet Win Aung.

U Khin Nyunt’s refusal to acknowledge his central role in these and other abuses has complicated efforts

“Building the Tatmadaw: Myanmar Armed Forces Since 1948.”

One incident in particular demonstrated the extent of his power: the forced retirement of then regime leader Snr-Gen Saw Maung on April 23, 1992, a move that “strengthened [Gen Khin Nyunt’s] position significantly,” according to Maung Aung Myoe. Although Snr-Gen Than Shwe assumed the leadership of the regime at that time, he still wielded relatively little actual influence.

When he was in power, Gen Khin Nyunt was incorrectly regarded by some foreign observers and diplomats as a “moderate,” and when he was eventually sacked, this was seen as confirmation that he was a “softliner.” Nothing, however, could have been further from the truth.

he was just following orders. As U Win Tin noted, Snr-Gen Than Shwe, the leader of the former ruling junta, was not solely responsible for the many abuses committed under military rule. “Khin Nyunt and his people were more responsible [for the treatment of dissidents],” he said. “It was their intention to let us die.”

Indeed, some have argued that U Khin Nyunt was the most powerful member of the ruling regime, at least in the years immediately after it seized power.

“As a protégé of U Ne Win, [Gen Khin Nyunt] came out as the most influential figure in the regime,” wrote Maung Aung Myoe in his book,

Over time, Gen Khin Nyunt sought to increase his power behind the scenes by using his position as spy chief to keep the other generals in check. Under his leadership, officers in the MI were feared by those in the infantry, and the normal hierarchy was subverted. “A captain in the intelligence corps never cared about a colonel in the infantry. The commanding officer of a local intelligence battalion, a major, behaved as if he was of equal power as the regional commander, a majorgeneral, in that region,” wrote Maung Aung Myoe.

The reality was that he had spread his tentacles into every corner of the regime’s affairs, and was a central player in all of its often brutal activities. He victimized not only dissidents of the years when his protégé, Gen Khin Nyunt, still wore a uniform.

For all he has done, U Khin Nyunt and his key subordinates deserve to face justice. Unfortunately, under the current delicate political circumstances in Myanmar, that is unlikely to happen. But until he makes amends to all those whose lives he has ruined, U Khin Nyunt will never find the peace he seeks through meditation and donations to pagodas. If justice doesn’t extract its due, karma certainly will.

Kyaw Zwa Moe is the editor of the English-language edition of The Irrawaddy. PHOTO: JPAING / THE IRRAWADDY By NYEIN NYEIN / MAE SOT, Thailand

By NYEIN NYEIN / MAE SOT, Thailand

For decades, Myanmar has made two enormous contributions to the economy of its much more prosperous neighbor to the east: vast quantities of natural gas, and millions of workers.

Of these, the latter has arguably been the more important. As Thai workers use their political clout to push for higher wages, poorly paid migrants help to keep down production costs, enabling Thailand to maintain its global competitive edge.

But this boon to Thailand’s economy has come at a considerable human cost. Most Myanmar workers, desperate to escape poverty at home, have poured over the border without going through official channels, leaving them vulnerable to exploitation.

Despite efforts to grant them legal recognition, exploitation remains a fact of life for many Myanmar nationals working in Thailand

This was all supposed to change in 2009, when the governments of Myanmar and Thailand finally decided to implement a system that would grant Myanmar workers legal recognition.

To some extent, it has worked. In the nearly five years since it was first introduced, the Nationality Verification (NV) system has seen some 1.7 million workers from Myanmar register. As a result, many are now better paid and more secure in their employment than ever before.

But the bigger picture is much less encouraging. Despite the strides made since 2009, another 1.3 million Myanmar migrants in Thailand—nearly half of the estimated three million in the country—remain unregistered.

The reason, say those familiar with the NV system, is that it is too expensive, too complicated, and too prone to corruption.

Even since 2010, when Myanmar and Thailand signed a Memorandum of

Understanding (MoU) that would allow Myanmar workers to line up work and proper documentation before entering Thailand, many still opt to simply cross the two countries’ porous border in search of work rather than apply for a temporary Myanmar passport and two-year Thai visas and work permits.

For many, the chief beneficiaries of the current system are the legions of “agents” who act as middlemen between workers, employers and the often corrupt bureaucracies of both countries.

“All this system has done is fuel an industry that takes advantage of migrants,” said U Kyaw Thaung, the head of the Bangkok-based Myanmar Association in Thailand, which deals with workers’ rights issues.

According to official figures, there are more than 60 labor agencies in Myanmar licensed to help their clients find work abroad. But this is just a small part of this burgeoning industry, which includes dozens of unregistered agencies operating in border towns and countless freelancers familiar enough with the system to know how to work around it.

“We’re the ones who know how to get things done—how to get approval from the Thai Department of Employment by paying money under the table,” said U Kyaw Kyaw (not his real name), an agent working in the Thai border town of Mae Sot, one of the main entry points for Myanmar workers seeking employment in Thailand. “Without us, the workers and employers couldn’t do anything.”

But this help doesn’t come cheaply. Under the terms of the 2010 MoU, agents can charge no more than 100,000 kyat (US $103) for services rendered in Myanmar, or 10,000 baht ($320) in Thailand. In practice, however, brokers and labor-rights activists say that these services often cost as much as 700,000 kyat ($720) and 28,000 baht ($900), respectively.

Family members of migrant workers from Myanmar spend time together at their collective housing near Mae Sot.One reason for these exorbitant fees, which are far beyond the means of most migrant workers, is that officials often demand bribes to speed up the process of issuing the relevant documents. Again, while the law states one thing—that the entire process should not take more than two weeks to complete—the reality is that it can take months to procure all the necessary papers, unless you’re prepared to pay extra for the cooperation of the issuing authorities.

The entire process could hardly be more daunting for many wouldbe migrant workers. In order to get a temporary passport under the 2010 MoU scheme, applicants must first show their national ID cards—something that many in rural areas don’t possess. In addition, they must have proof of a prospective employer, provided by licensed employment agencies in both Myanmar and Thailand.

Once they have their Myanmar documents in hand, workers can then apply for the Thai papers they need. But even when they have these, many report that they are still subjected to

further shakedowns by Thai police as they make their way to their new jobs.

Despite such obstacles, however, continuing stagnation in Myanmar’s job market means that many still see Thailand as their best hope for making a living. According to official figures, some 800,000 Myanmar nationals entered Thailand under the MoU scheme in the six months between March and August 2013.

Clearly, though, the system provides few safeguards against exploitation. According to U Kyaw Kyaw, the freelance agent in Mae Sot, officials have issued passports to children as young as 13 for bribes of 1,500 to 2,000 baht—money presumably paid by employers or providers of cheap, underage labor.

The MoU system also puts workers at the mercy of employers by requiring them to complete their contracts before they can seek work elsewhere in Thailand. Those who leave their jobs before the end of the agreedupon period are often forced to go through the whole application process again, at great expense. In such cases,

many simply choose to take their chances with working illegally.

Far more common, however, are the many who never go through the process in the first place. In Mae Sot, where factory workers make as little as 2,500 baht ($80) a month, with most earning no more than 4,000 baht ($128), many simply can’t afford to change their legal status.

“I’ve been in Thailand for three years, but my employer has never said anything about legal documents,” said Ma Ei, a 35-year-old garment factory worker in Mae Sot who uses her 3,000 baht ($100) salary to support her three children back home in Pyay, Bago Region. “When the police come, we just run and hide.”

It isn’t difficult to see why many balk at paying the high fees demanded by agents and corrupt officials. Most of the estimated 150,000 Myanmar nationals working in some 700 factories in Mae Sot earn 80 baht or less for an eight-hour shift. But a typical workday is twice that long, with 10 baht paid for each hour of overtime. Even then, a day’s pay is roughly half the minimum wage of 300 baht prescribed by Thai law.

Workers with passports can make more, but are still paid less than the minimum. And they still have to pay bribes when they’re stopped by the police, because their employers usually hold on to their passports, only allowing them to carry photocopies.

It’s little wonder, then, that many Myanmar workers in Thailand feel that not much has changed since the introduction of the NV system in 2009. Indeed, for most, there’s a fine line between “agents” and human traffickers—and in many cases, they have good reason to suspect that neither has their best interests at heart.

More than three years after Myanmar’s military junta held the flawed elections that brought in the administration of President U Thein Sein, economic reforms are continuing apace, the government’s grip on the media has been loosened and the political opposition can criticize the quasi-civilian government in Parliament.

And while there are still doubts about how far the reforms will go, there remains no definitive answer to the question: What brought the regime out of its shell in the first place?

Swedish journalist Bertil Lintner, who has been writing about the country since his first visit in 1977, shed some light on the machinations behind the so-called opening up during a recent visit to The Irrawaddy’s office in Yangon.

“The Chinese influence was becoming too strong. And the leadership of the military wanted to open up to the West to get some independence from China. But in order to do that, they had to make certain concessions,” he said.

One key concession was allowing a political opposition. And so, days after the election in November 2010, democracy icon Daw Aung San Suu Kyi was released from house arrest, and President U Thein Sein, who came to office the following March, began the staggered release of hundreds of political prisoners. But those were not the only things the United States was interested in, said Mr. Lintner.

“We should not fool ourselves and believe that the two main guiding principles of America’s foreign policy are democracy and human rights. I don’t believe that for one second,” he said.

He pointed to Myanmar’s strategic significance and the little-discussed

issue of the generals’ friendly stance toward East Asia’s most feared rogue state.

“America’s interests are geopolitical,” he said, before stating what he considered to be the two major factors behind Washington new Myanmar policy: “First, China; Chinese influence is ‘very bad.’ And second, North Korea.”

Mr. Lintner was the first to write about the reestablishment of a Myanmar-North Korea connection in 2003, when the countries had begun working together again quietly after a long rift caused by the deadly 1983 bombing of a South Korean government delegation in Yangon by North Korean agents.

Ties grew stronger over the next decade and North Korean engineers reportedly constructed a series of tunnels near the new capital, Naypyitaw. In 2008, a highlevel Myanmar delegation visited Pyongyang, with reports emerging of

Whatever their reasons for opening up, Myanmar’s rulers have released a torrent of reform that can’t be reversed, says a respected expert on the country

radar and missile deals—as well as the possibility of nuclear cooperation— raising the stakes.

Mr. Lintner said that in late 2010, shortly before Myanmar’s elections, he was invited to Washington to talk at a conference on Myanmar-North Korean relations. The conference, he said, was riddled with men from “threeletter” American government agencies discussing how Myanmar could be brought into the Western fold and away from North Korea.

“We have to do something, we have to change our policy,” was the consensus forming in US diplomatic circles, he said.

Mr. Lintner also said the South Korean government played an important role in opening up channels of communication between the Americans and Myanmar’s ruling generals. “They [the US] came to a conclusion at that time that, ‘Well, the Burmese military hate us so much, we cannot talk to them directly, we have

to engage the South Koreans as an intermediary.’”

He noted that when US Secretary of State Hilary Clinton visited Myanmar in late 2011, in what was seen as one of the watershed moments early in the transition, she flew via Seoul after some meetings with South Korean officials.

But not everyone agrees that the shift in US policy on Myanmar was essentially about countering Chinese and North Korean influence.

In an article on US-China-Myanmar relations for the US-based East-West

Center in late November, seasoned Myanmar watcher and academic David Steinberg wrote that it was widely believed in China that the United States’ new willingness to talk to the Myanmar government “was predicated as anti-Chinese.”

“The evidence, however, for that motivation is lacking,” wrote Mr. Steinberg, who is the Distinguished Professor of Asian Studies Emeritus at Georgetown University.

“Rather, rapprochement was probably prompted by the clear failure of the isolation and sanctions policies of the previous US administrations, signals from the Burmese that improved relations were in their own interests, the possibility of a US foreign policy ‘success’ in East Asia, and the necessity to work with Myanmar if the United States was to have any significant interaction and role in [the Association of Southeast Asian Nations].”

Whatever ends up in the history books as the trigger for Myanmar’s transition, Mr. Lintner said the country’s generals no longer have the option of rolling back reforms.

In the past, hopes of a genuine opening up had been dashed before they could become irreversible, as in 2004, when a purge within the military saw hardliners resume control. This time, though, the toothpaste is out of the tube, and it can’t be put back in, said Mr. Lintner.

“The bottom line is that once you start to change a very rigid political system, it is very difficult to stop,” he said, recalling the experience of former Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev, who began the country’s “Perestroika,” or restructuring, in the mid 1980s but never intended reforms to lead to the breakup of the Soviet Union.

“Even cosmetic changes can have unintended consequences,” Mr. Linter said.

“Even cosmetic changes can have unintended consquences.”

-Bertil LintnerLeft: North Korean leader Kim Jong Un (front row center) attends a meeting of the ruling Workers' Party politburo in Pyongyang in an undated photo released by North Korea's Korean Central News Agency on Dec. 9, 2013. Far left: Journalist Bertil Lintner

The Hsipaw Haw, or Hsipaw Palace, is a treasure hidden in the woods of Shan State, guarded by tall tamarind trees. Foreign tourists visit here to enjoy the atmosphere and to hear the sad story of Sao Kya Hseng, a young Shan prince who disappeared shortly after the military staged a coup in March 1962.

In 2012, I went up to Lashio in northern Shan State and decided to stop in en route at Hsipaw (or Thibaw) to visit the residence of the famed prince, whom I had read about in “Twilight Over Burma,” a book written by his wife, Inge Eberhard.

After dropping the names of a few prominent Shan people I know living in northern Thailand, a young man wearing the region’s traditional loose trousers and carrying a Shan sword finally opened the gate, flanked by a dozen canine bodyguards.

His caution was understandable, as his great-uncle had been arrested just a few years earlier on “tourism charges”. The old man has only recently been released, and now his great-nephew knows better than to trust strangers.

Sao Kya Seng’s palace (which is also known simply as “East Haw”) is in a sad state, but with a little careful restoration, it could be a great place to learn about the history of Hsipaw and the tragic fate of its royal family.

Indeed, there are several palaces in Shan State that were either neglected or demolished by Myanmar’s former military rulers, who claimed to serve the country’s multi-ethnic “Union Spirit”, but who generally treated the cultural legacy of ethnic minorities with disdain.

If we restored those elegant palaces and reopened them as museums, foreign and domestic tourists would surely flock to them to learn about their history and appreciate the beauty of their architecture. Most importantly, young citizens of our country could rediscover its ethnic diversity and gain an understanding of how our cultural wealth has been squandered through decades of misrule.

Of course, the story of Hsipaw Palace could not be told without an account of what happened to its last royal inhabitant.

Sao Kya Hseng was last seen in

March 1962, when he was arrested in the state capital Taunggyi while visiting his ailing sister. He was blissfully unaware of what had taken place in Yangon at the time: a coup by Gen Ne Win that put the military at the head of state power.

The prince was arrested on his way to Heho Airport to catch a flight back to Hsipaw. He was last seen being taken to an unknown place of detention by armed soldiers.

Born in 1924, Sao Kya Hseng was educated at schools at Darjeeling, India, and went to study engineering at the Colorado School of Mines in Denver, Colorado, in the United States, where he married his Austrian bride.

It was true love. The new bride decided to follow her husband to live in Myanmar—a country she had never

visited before—despite having no idea that the man she had married was a Shan saopha, or prince, and the ruler of Hsipaw.

Only when their ship arrived in Yangon and she saw hundreds of people playing music and carrying flowers to welcome someone who was obviously very important did she learn about her husband’s identity. When she asked him who everyone was there to greet, he told her she had married a Shan prince, and that she—who would later take the name Sao Nang Thusandi—was the Mahadevi, or celestial princess, of Hsipaw.

It may have been like a fairytale come true at the time, but these days, the luster on the royal household has dimmed. Our young guide took us inside East Haw, where Sao Kya

Hseng and Sao Thusandi lived with their children and servants. We saw the family tree and living room as well as photos of the prince and his family.

When I walked into the inside Haw, my young guide, a relative of the late prince, was proud to show how his ancestor built the palace and brought in an old tractor still parked by the portico. He also explained how Sao Kya Hseng introduced new ideas regarding the state’s age-old feudal system.

In the foreword of “Twilight over Burma”, Swedish Journalist Bertil Linter wrote: “Perhaps the most radical idea was to give all the princely family’s paddy fields to the farmers who cultivated them. In addition, [Sao Kya Hseng] bought tractors and agricultural implements that the farmers used free of charge, cleared land to experiment

with new crops, and began mineral exploration in the resource-rich valley.”

Sao Kya Hseng was undoubtedly more than just a privileged landowner. He was an MP for Myanmar’s House of Nationalities, a member of the Shan State Council and the secretary of the Association of Shan Princes. He remained in politics while many Shan saophas gave up their positions. But then in the 1950s, a cloud descended onto Shan State.

In 1958, government troops arrived to drive out a Chinese Kuomintang incursion and quell a rising resistance movement that sought Shan State’s secession from the Union. Shan rebels and sympathetic villagers were arrested, tortured and disappeared.

Amid this turmoil, it is uncertain how Gen Ne Win and his loyal military

officers viewed Sao Kya Hseng as they prepared to seize power in a coup.

In her book, Sao Thusandi said that the Shan who desired an independent Shan State wanted Sao Kya Hseng to lead the revolt, but the young prince was reluctant. On the other hand, pro-Union advocates suspected him of being a secessionist due to his open criticism of Myanmar politics and army misconduct.

Indeed, Gen Ne Win and Sao Kya Hseng did not get along well. When Gen Ne Win, who was then army chief, was passing through Hsipaw, the prince wanted to invite him for lunch at East Haw, where high-ranking Myanmar ministers and politicians often visited for dinner reception and tea.

In her book, Sao Thusandi said that one of Gen Ne Win’s officers declined on his behalf and instead asked the prince to wait by the roadside for the general’s motorcade. Shocked to hear such a disrespectful suggestion, the ruler of Hsipaw declined.

Sao Kya Hseng’s supporters insisted that Gen Ne Win and his military intelligence chief Col. Lwin— also known as “Moustache Lwin”—must have had knowledge of what became of the prince after his detention.

However, Gen Ne Win’s regime denied any role in his disappearance and made several contradictory statements about it. In fact, Sao Thusandi received a short letter from her husband that said he had been detained in Ba Htoo—a garrison town in Shan State—and he was “still OK”. Still, the authorities never officially admitted apprehending the prince.

Sao Thusandi went to meet Daw Khin May Than, Gen Ne Win’s wife, in Austria in 1966, when the general was there to receive medical treatment. The dictator often went to Europe, where he would meet Prof. Hans Hoff of the Psychiatric and Neurological University Hospital of Vienna. It was suggested that the general suffered from bipolar disorder and other mental illnesses.

Subsequently, Prof. Hoff was involved in the case, too. He had earlier written a letter to Sao Thusandi in Yangon that stated her husband was in detention. Gen Ne Win assured his doctor that the Shan prince was well and that two orderlies had been assigned to take care of his every need.

Prof. Hoff then wrote: “The physician who looks after Sao [Kya Hseng] was introduced to me, and he testified that Sao is in good shape, both physically and emotionally.” Yet that same day Sao Thusandi received a letter from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs saying that the government had never detained the Shan prince.

Was Gen Ne Win trying to deceive his psychiatrist for some reason? He and his henchmen were probably

Facing uncertainty up in the Shan Hills, Sao Thusandi finally moved down to Yangon. One day, a prominent guest walked into her residence—Bo Setkya, a member of the legendary “Thirty Comrades”. Gen Ne Win had also belonged to this group, which received military training in Japan to liberate Myanmar from British occupation.

Bo Setkya, who must have had supporters and his own intelligence sources in the army, came to meet the princess and told her that her husband had died. Sao Kya Hseng was killed near Ba Htoo several weeks after his arrest, he said. Sao Thusandi and her family finally left Myanmar in 1964.

It is not known what actually happened to the prince, although Gen Ne Win and his top officers must have been well aware of his fate. One theory was that Sao Kya Hseng died during interrogation, while another said that he was killed trying to escape—army officers were given “shoot to kill” orders at the time.

The last theory was that he was caught alive and when young officers asked a superior what to do, they were simply ordered to execute him. Those involved then maintained a cowardly silence after they realized the magnitude of what had taken place.

telling lies to everyone—Sao Thusandi, Prof. Hoff, and the European diplomats who were trying to help locate the prince.

Meanwhile, several associates of Sao Thusandi told her that the prince was no longer alive. I suspect they were probably correct. The prince was no longer alive, but Gen Ne Win and his officers kept pumping out their deceits. That was the character of the late general. There were a few sympathetic officers who had guarded the prince secretly, and who reassured Sao Thusandi that he was still alive, but they were quickly removed and probably had no idea what ultimately happened to him.

The rain began to pour as I listened to the story of the palace and the Shan prince. I walked towards a wooden building far from East Haw surrounded by spirit houses and was told that this was where the late prince like to pray and read. The building, if restored, would be an elegant addition to Myanmar’s ethnic cultural heritage, but unfortunately it has already almost collapsed.

From the day Gen Ne Win staged his coup, Sao Kya Hseng was prevented from ever seeing East Haw again. One can only hope that his soul somehow managed to return to his royal abode, and that dignity of this place will one day be restored. Only then, perhaps, will the true story of what befell the tragic Shan prince be told.

By ZARNI MANN / YANGON

By ZARNI MANN / YANGON

As the sun sets on the skyline of Myanmar’s former capital, small trucks and trolleys loaded with cooking pots big and small flock into the city’s busiest areas from all directions. The streets and sidewalks, crowded with cars and pedestrians during the day, are taken over by large stoves and small tables and chairs.

The voices of street vendors calling customers rise with the smoke and mouth-watering smells. Their stalls serve everything from Myanmar’s signature dishes—mohinga (noodles in fish broth), ohn no khauk swe (noodles in a curried coconut-milk broth) and laphet thoke (pickled tea-leaf salad)—to Chinese dim sum, Japanese sushi and Korean-style barbecue.

For many a Yangonite, these stalls are places to sit and chat with friends after a stressful day’s work. The price of most dishes—between 500 and 1,500 kyat—is low enough to dispel any misgivings they may have about the safety of the food.

“I don’t have much time to cook after work, so I’m glad to have somewhere to eat that doesn’t cost too much money,” said one saleswoman from a downtown electrical goods store. “The food tastes good and it’s served hot, so I’m not too worried about cleanliness.”

Every night, crowds flock to Chinatown, the area around City Hall, and the Hledan and Myaynigone junctions to get their fill of cheap eats. Amid the hustle and bustle, it’s easy

not to notice just how dirty some stalls can be. But take a closer look and you’ll soon see why health experts—if not ordinary customers—are concerned.

At one recently observed mohinga stall, for instance, a girl tended to a pile of dirty dishes in a messy corner by dipping each one into a small

plastic bowl filled with soapy water and reddish-yellow oil and giving it a quick swipe with a grimy sponge. After a final dive into another plastic bowl filled with more opaque water, the dishes were ready to serve their duty again.

Think takeaway might be a better option? Think again. At the same stall,

the proprietor prepared an order to go by placing noodles into small polythene bags with her bare fingers, moments after receiving torn, grubby bills from her customer. She then poured hot soup into another bag.

“We were told that using polythene bags to carry hot stuff is not healthy, but

we have no choice. Paper containers are too expensive,” the shopkeeper said, adding that she always tried to sell healthy food and maintain good hygiene.

Since low prices are the key to success in this business, many street food vendors skimp on quality and hygiene, often at the expense of food safety, according to the Yangon-based Consumer Protection Association (CPA).

“They can’t invest much in their products, so they usually use cheap ingredients such as palm oil and a lot of artificial flavors,” says Daw Soe Kalyar Htike, secretary of the CPA’s information department. “Also, they have limited access to water, so they can’t use a lot to clean dishes. And the food is not well covered from dust, flies and fumes from cars.”

In a recent survey of more than 1,000 street food stalls in central Yangon, CPA found that more than 80 percent were selling unhealthy, unhygienic food.

“Both consumers and vendors need to be educated about the need for better hygiene and healthier foods,” says Daw Soe Kalyar Htike, adding that this isn’t just the job of the government, but also of NGOs. For its part, the CPA has started an education program for schools to teach children about food safety.

The Myanmar Restaurant Association (MRA) is another group spearheading efforts to promote better

food preparation practices among street vendors. According to its general secretary, U Kyaw Myat Moe, the MRA is now working on a project to choose 12 street-side stalls to hold up as models of good hygiene.

“What we have found is that many street vendors are too focused on their earnings, because of economic hardships,” he told The Irrawaddy. “For example, they may reuse disposable kitchenware rather than throw it away, which could harm the health of consumers.”

To change the way vendors and consumers view issues of food safety, the MRA is advocating the introduction of licensed stalls in City Hall-approved areas, providing vendors with disposable caps and gloves for free, while educating vendors about hygienic food preparation.

“If the stalls become neat and tidy and good examples of healthy and hygienic foods for everyone, consumers will be satisfied and have healthy food,” said U Kyaw Myat Moe. “We believe that the street food vendors will also benefit and profit by selling healthy food.”

Above left: A food stall near City Hall in Yangon Above right: A stall sells fried chicken on downtown Yangon’s Shwebontha Street. Far left: People enjoy a meal of pork stew, fried tofu and meatballs at a food stall near the Central Fire Station in downtown Yangon.

Lex Rieffel is a former staff economist in the US Treasury Department who has worked with the Brookings Institution since 2002. Currently teaching a seminar on Myanmar at the School for Advanced International Studies at Johns Hopkins University in Washington, DC, he has visited the country more than a dozen times since 1967. In this interview with The Irrawaddy’s William Boot, he discusses his observations from his latest visit, and warns that too much, rather than too little, investment could be the greatest danger to the country’s economy at this stage.

What changes for the better— or perhaps for the worse—did you notice on your last visit to Myanmar compared with earlier tours?

In January 2010, I began visiting Myanmar every six months for at least two weeks each time. My last visit was in July-August 2013. From an economic development perspective, I have witnessed steady and remarkable and positive changes from one visit to the next. I hope the pace of positive change will continue for the next 30 years with no significant interruptions, as it did in China.

I have been most impressed by the government of Myanmar’s decision to move to a market-based exchangerate system on April 1, 2012, by the debt-relief operation in January 2013, and by the award of two mobile-phone licenses through a competitive process in June 2013. I have been pleasantly surprised by how rapidly the private banks in Myanmar have been raising their game.

My biggest worry is that the 70 percent of the population that lives in rural areas and depends on agriculture is being left behind because of inadequate agriculturesector policies. Another big worry is

that Myanmar is being smothered with love: too many non-Myanmar people are coming to Myanmar to “make a difference.” They all want to meet with the top policymakers and as a consequence these policymakers are not giving enough attention to the crucial tasks of policy formulation and implementation.

Beyond these short-term concerns, of course, are the existential challenges of establishing peace and overcoming the country’s resource curse.

Processing key investments often seems bogged down in bureaucracy. For example, offshore oil and gas development: Despite international interest for more than one year, it will be first quarter 2014 before any of 30 new blocks on offer are awarded. Is this due to inexperience by government departments, and if so how can it be improved?

What’s the rush? I share the view of many others that Myanmar suffers from a resource curse, part of which derives from excessive ongoing extraction of resources. I pointed out back in May 2010 that an economic case can be made for declaring a fiveyear moratorium on new resource extraction projects.

Myanmar’s resources are unlikely to be widely perceived as a blessing until the government of Myanmar is able to negotiate transparent contracts with resource-extracting companies that maximize revenue to the national treasury, and to create financial systems that visibly channel this revenue to projects and programs that benefit the population as a whole.

I believe the government of Myanmar does not have the ability to do this now, and it could easily take five years to develop the ability. In the meantime, the government of Myanmar should be able to obtain all the foreign exchange it needs to foster rapid economic growth and rising living standards from existing resource extraction projects (in some cases on the basis of renegotiated contracts), from FDI in the manufacturing and service sectors, from foreign aid, and from remittances sent by Myanmar people residing in other countries.

Do you think that Myanmar’s vague laws, continuing lack of transparency and fragile financial system still deter some major investors?

Yes, there can be no doubt about these obstacles, which deter small investors as well as “major” investors. At the same time, it is important to

have realistic expectations about the pace of improvement in Myanmar’s business climate. Look how long it has taken China to create an attractive environment for investment.

Many experts would say that China still does not have one. One lesson from China’s experience is that political stability, including a negligible level of internal conflict, is more important than well-crafted laws, above-average transparency and a sound financial system.

It is not easy to assess the views of investors because there are so many factors that go into their investment decisions. There seem to be plenty of major investors gearing up to operate in Myanmar. From an economic development perspective, I see more risks from Myanmar getting too much foreign investment in the near term than getting too little.

Myanmar’s economy is expanding quickly in some areas, notably in property and tourism, but foreign investment in infrastructure such as electricity supply remains sluggish. Is there a danger of lopsided economic growth?

There is always danger in lopsided economic growth, but there is just as much danger in trying to force balanced growth in a low-income, late-starting country like Myanmar.

A market economy is a complex system with many “non-linearities.” This means that when an input is increased, the output does not necessarily increase; it will increase more at some moments and less at others, depending on what is happening elsewhere in the system. Growth is an “emergent” phenomenon. This means it is fundamentally unpredictable.

I believe that the single most important key to satisfactory, sustainable growth in a country like Myanmar is selecting good ministers, deputy ministers, and director generals. These are the people who decide which policies

to adopt and then ensure that these policies are well implemented. Putting the right women and men into these positions today is more important than building effective institutions because the policies will affect people immediately while building effective institutions can easily take more than one generation. And if the right people are chosen, they will get the process of institution building off to a good start.

Myanmar might perhaps look to Thailand as an example of economic development, but a centralized system there has focused much national wealth in Greater Bangkok while rural poverty remains elsewhere. What can Naypyitaw do to avoid that negative trend? Is a federal system the answer?

I’m an economist, not a political scientist. The question reminds me of a quotation attributed to [the late Chinese leader] Deng Xiaoping: It doesn’t matter if a cat is black or white, so long as it catches mice. It seems to me it doesn’t matter what kind of political system Myanmar chooses as long as it leads to internal peace and releases the energy that exists in the Myanmar population to build a prosperous society.

Why would Myanmar look to Thailand for an example of economic development? I see a lot of unhappy people in Thailand. Why would Myanmar want to consider any other country to be a model for its development?

The world will not benefit from having a Myanmar that looks like a clone of Thailand or Vietnam or Singapore. It will benefit from a Myanmar that finds better solutions to the problems that diminish the quality of life in these countries and many others. I hope the government and people of Myanmar aspire to developing their economy better than other countries have done and thus become a model for others.

By SIMON ROUGHNEEN / YANGON

By SIMON ROUGHNEEN / YANGON

Mitsubishi might be among the Japanese brand names lining up to invest in Myanmar, with deals done for revamping Mandalay’s airport and building a power plant at the proposed Dawei Special Economic Zone in Myanmar’s far south, but that didn’t stop a senior company representative from telling it

like it is to some Naypyitaw government representatives.

“There are too many laws, frankly speaking. We have to study so much to enter into the country,” said regional Asia and Oceania CEO Toru Moriyama, speaking at a business seminar in Yangon hosted by Nikkei, the Japanese media conglomerate.

While Myanmar has passed several

new codes aimed at attracting investors and pepping up economic reforms, such as the 2012 Foreign Investment Law, some outdated laws remain in place, such as the 1914 Companies Law and, even older, the 1872 Evidence Act.

A century and more might have passed since some of these laws were enacted, but Dr. Aung Tun Thet, an economic advisor to Myanmar President U Thein Sein, said that investors should be patient, reminding them that Myanmar is a mere 30 months into a reform process initiated by the president’s civilian-run but army-backed government.

The progress made during that time—or rather, the perceived lack thereof—has drawn fire from many in the country. Opposition leader Daw Aung San Suu Kyi has said reforms are moving too slowly, and Union Parliament Speaker U Shwe Mann, a party colleague of the president, has also questioned how Myanmar’s political and economic reforms are

going. In late October, he even revealed that former junta head Snr-Gen Than Shwe was “concerned” about the country’s direction since he yielded power nearly three years ago.

But it is the assessment of outsiders that Dr. Aung Tun Thet takes greatest issue with. “Your expectations are sometimes quite unrealistic,” he said, referring to both foreign governments and companies. “Some people say we are moving too fast, others say too slow. I think that means we must be doing something right.”

While the Myanmar government hopes for a quadrupling of the country’s economy by 2030, such expansion, if it comes about, will be off the back of decades of sclerosis.

Myanmar’s US$53 billion economy is but one-seventh that of neighbor Thailand, which has a similar-sized population, Vietnam, which undertook a similar opening in the 1990s, has an economy nearly three times the size of Myanmar’s.

The signs of Myanmar’s ossification are everywhere to be seen—from the on-off access to electricity to the country’s continued reliance on cash for almost all transactions, in an economy dominated by well-connected “cronies” with ties to the still dominant armed forces.

But Dr. Aung Tun Thet is quick to remind critics of what the government is up against. “You have to remember, we haven’t had a proper business system here for 60 years,” he said.

Among the major hurdles for wouldbe investors are Myanmar’s electricity and infrastructure shortcomings, as well as a lack of skilled workers. Less than 30 percent of the population, mostly people in cities, are connected to the grid, while Internet and mobile phone access is thought to be around the 10 percent mark. And change will be slow in coming. Telenor, one of the two foreign companies granted licenses to set up mobile phone networks in Myanmar, said in November that it would be at least August 2014 before its network in the country would be launched.

Foreign investment into Myanmar increased from $1.9 billion in 2011-12 to $2.7 billion in 2012-13, according to the World Bank, which predicted growth of 6.8 percent for the current fiscal year ending in March 2014.

Sustaining that momentum—and pulling in job-intensive investment as opposed to companies interested in harvesting Myanmar’s oil and gas resources, work that typically doesn’t generate much local employment— will require further reforms from Parliament, whose members are now moving into election mode as the government passes the midway point of its five-year term in office.

U Win Aung, president of Myanmar’s main business representative group, the Union of Myanmar Federation of Chambers of Commerce and Industry (UMFCCI), said that the country’s companies and the government want

whatever outside help they can get to address such deficits.

“We are optimistic and confident that with the kind help and guidance of our partners, we will overcome these difficulties,” he said.

The past year has seen a revival of interest in Myanmar’s garment-making sector, with Korean companies drawn by Southeast Asia’s lowest wages and setting up or pledging to set up shop— deals that will create thousands of jobs for Myanmar women.

But in a country wracked by harsh rural poverty and emigration, more factories are needed to soak up some of the estimated 37 percent of the potential workforce without jobs.

Getting those investments means not only doing something about the power shortages and poor communications that wipe out the cost benefits of cheap labor, but changing Myanmar’s laws so the likes of Mitsubishi have less to complain about.

Dr. Aung Tun Thet pointed out that Myanmar has recently signed up to the New York arbitration convention, affording foreign investors some legal protection in the event of a dispute with a local partner and undercutting at least some worries about corruption, an opaque legal system and cozy ties between politicians, army and business.

Dr. Khin San Yee, the deputy minister for national planning and economic development, also said that Myanmar is trying to cut red tape and rein in “unnecessary procedures” to “improve our business environment.”

Such changes are needed. The World Bank recently outlined that starting a business in Myanmar involves 11 different procedures, takes 72 days and costs nearly $1,500, in addition to a deposit of more than $58,000 that must be paid to get the final go-ahead to set up shop, all of which slows entrepreneurship.

But even as she acknowledged Myanmar’s poor standing in the World Bank’s latest Doing Business global survey, which ranked the country a lowly 182 out of 189 nations, Dr. Khin San Yee did her tongue-in-cheek best to put a positive spin on the situation.

“At least we are on the list now,” she joked.

being developed between the city and the airport.

The Novotel Inle Lake Myat Min, with 121 rooms, will be the first of the three to open, during 2014, said TTR Weekly.

but Chinese influence will remain, according to a senior academic in neighboring Yunnan Province.

A British freight handling company with offices in Yangon is giving financial backing for a resumption of the search for a World War II Spitfire planes believed to be buried in Myanmar.

The Claridon Group, a worldwide freight logistics business, said it will fund the search by Briton David Cundall, which was called off earlier this year when a previous sponsor withdrew support.

Claridon said it was inspired to help Mr. Cundall after he unearthed new evidence to support an unproven story that 30 or more unused and crated Spitfires were buried at sites in Myanmar at the end of WWII.

“Due to a lack of sponsorship earlier this year the project looked doomed. After hearing about David’s situation, Claridon stepped in to provide the funding to allow the project to continue,” the company said, without adding how much money it will provide or how long the search will continue.

Claridon, which has an office close to Yangon port, says it is “working in partnership with the UK Government Trade and Investment body to promote Myanmar business opportunities to British industry.”

The French international hotels operator Accor Group is to take over the management of three more new hotels in Myanmar, raising its portfolio to six. Two of the three hotels, all still under construction, are in Yangon and the third is beside Inle Lake in Shan State.

“Accor is proud to announce the signing of three hotels with our new partner,

Myat Min Co. Ltd., making this one of the largest hospitality partnerships in Myanmar,” said Accor’s senior vice president for the region, Patrick Basset.