www.irrawaddy.org TheIrrawaddy January 2015 Screen Star ‘Grace’ Talks Acting And Activism Dockside Dining At Port Autonomy Vintage Rail Ride Sets Out From Bagan Muse Trade Zone To Boost Growth DOLPHINS NEED A LIFELINE THE KOLA IN CAMBODIA

M Y

C

|||

Woman’s Lifestyle Day

Main sponsor & organiser Shangri-La Spa

Co-sponsors -

Topics Covered:

• Importance of healthy skin

• Basic skin types and specific skin conditions

• Skincare routine to achieve good skin

• Why Dermalogica?

Wine Appreciation Workshop

31st January 2015, Saturday 2.00pm – 5.00pm

Taw Win Garden Hotel, Grand Ballroom

Tea reception will be held

Ticket price: 45,000ks

Shangri-La Spa members are entitled to one complimentary ticket

Topics Covered:

• Discovery of grape varieties

• Learning about wine tasting

• Food & wine pairing

• Health benefits of drinking wine

For ticket enquiry, please contact Shangri-La Spa at 09 3155 1844 or 09 2532 42440

3 January 2015 TheIrrawaddy

Skin Health Talk by Ms Khine Cindy Soe (Education and Communication Manager, Dermalogica Myanmar)

by Ms Melanie Grillon (Co-founder of MWS, MWS Beverage Academy)

TheIrrawaddy

The Irrawaddy magazine has covered Myanmar, its neighbors and Southeast Asia since 1993.

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF: Aung Zaw

EDITOR (English Edition): Kyaw Zwa Moe

ASSOCIATE EDITOR: Sandy Barron

COPY DESK: Paul Vrieze; Andrew D. Kaspar; David Kay; Feliz Solomon; Sean Gleeson

CONTRIBUTORS to this issue: Aung Zaw; Kyaw Phyo Tha; Zarni Mann; Nyein Nyein; Kyaw Hsu Mon; Kyaw Kha; Bertil Lintner; Virginia Henderson; Lawi Weng; Simon Lewis; Phorn Bopha; Sean Gleeson; Edith Mirante; Oliver Gruen; William Boot; Brennan O'Connor; Thuzar; Nan Lwin Hnin Pwint; Nobel Zaw; Pu Pu

PHOTOGRAPHERS: JPaing; Sai Zaw; Hein Htet; Teza Hlaing; Steve Tickner

LAYOUT DESIGNER: Banjong Banriankit

SENIOR MANAGER : Win Thu (Regional Office)

MANAGER: Phyo Thu Htet (Yangon Bureau)

REGIONAL HEADQUARTERS MAILING ADDRESS: The Irrawaddy, P.O. Box 242, CMU Post Office, Chiang Mai 50200, Thailand.

YANGON BUREAU : Building No 170/175, Room No

806, MGW Tower, Bo Aung Kyaw Street (Middle Block), Botataung Township, Yangon, Myanmar.

TEL: 01 388521, 01 389762

EMAIL: editors@irrawaddy.org

SALES&ADVERTISING: advertising@irrawaddy.org

SUBSCRIPTIONS: subscriptions@irrawaddy.org

PRINTER: Chotana Printing (Chiang Mai, Thailand)

PUBLISHER LICENSE : 13215047701213

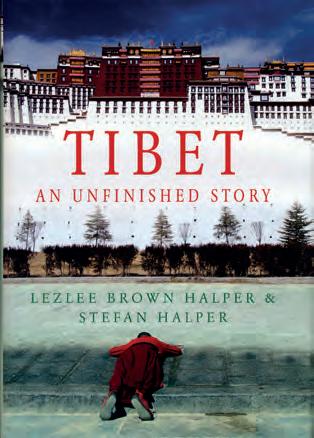

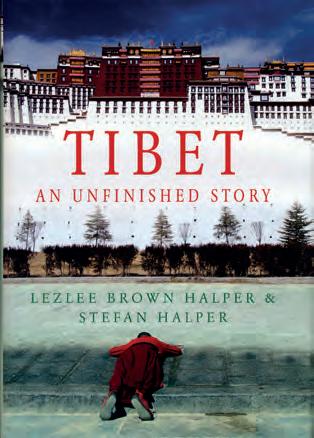

6 TheIrrawaddy January 2015 Contents 8 | In Person Screen Star Talks Acting And Activism 10 | Quotes and Cartoon 12 | News Highlights 14 | In Focus 16 | Viewpoint LIFESTYLE 41 | COVER Dolphins Need A Lifeline Irrawaddy dolphins are under threat, but tourism may help 46 | Vintage Rail Ride An old steam train takes passengers from Bagan to near Mount Popa 48 | Juggling For Joy Performers will channel the spirit of chinlone at a Yangon festival 50 | A Barber and a Bus Conductor Yangon Film School graduates impress with minimal yet poignant portraits 52 | Restaurant: Dockside Dining Worlds collide agreeably at this modern diner on the Yangon riverfront 54 | Book: Myth and Meaning in Tibet Scholars probe the history of the territory known as the ‘roof of the world’ 56 | Backpage: Brave New World A locale-hopping cyber fantasy is attracting rave reviews

Vol.22 No.1

COVER PHOTO : Teza Hlaing / The Irrawaddy

www.irrawaddy.org TheIrrawaddy January 2015 Screen Star ‘Grace’ Talks Acting And Activism Dockside Dining At Port Autonomy Vintage Rail Ride Sets Out From Bagan Muse Trade Zone To Boost Growth

THE KOLA IN CAMBODIA

DOLPHINS NEED A LIFELINE

FEATURES

18 |

History: The Kola of Cambodia

A Buddhist pagoda and an elderly woman are among the last traces of mysterious Myanmar migrants

22 | Borders: Brides for Bachelors

Lured by false promises, women and girls from Myanmar continue to be trafficked to China

24 |

Society: Rewards and Risks

Young men from poor villages in Shan State earn a living as sex workers in gay “show bars”

REGIONAL

26 |

Japan: Hiroshima Survivor Still Searching For Victims

A-bomb survivor and local historian Shigeaki Mori continues search for details of POWs killed in the atomic bombings in Hiroshima and Nagasaki

BUSINESS

31 | Interview: Going for Growth

The UMFCCI's vice chairman talks about economic prospects and pitfalls

34 | Enterprise: Hurdles and Wins

Survey confirmed issues facing new firms but said “spectacular sales growth” awaits if reforms continue

36 |

Trade: Muse Zone to Boost Trade

Expansion moves ahead despite some locals’ complaints

38 | Signposts: ADB to Loan $100m to Yoma

7 January 2015 TheIrrawaddy

P-18

P-26

P-31

P-46

Former Screen Star Talks Acting And Activism

After more than two decades in the film industry, former Myanmar actress Daw Swe Zin Htike, also known as Grace, embarked on a new career in the nonprofit sector. She was Population Services International (PSI) Program Director from 1999 to 2013 and now devotes much of her time to educational projects, while continuing to promote Myanmar’s film industry. The 61-year-old award-winning former actress spoke with The Irrawaddy’s Kyaw Hsu Mon about her wide-ranging work, including in health and education, and her push to encourage more female film directors.

in Myanmar. That’s why I wanted to do more in the education sector and worked for initiatives like the Myanmar Mobile Education Project (myME).

What challenges did you face in transitioning from a successful acting career to the NGO field?

When did your acting career begin?

I worked in the film industry from 1971 to 1993. I acted in more than 200 films in that period and won a Myanmar Academy Award in 1977. I was also nominated on four occasions.

What is your educational background?

My undergraduate degree was a Bachelor of Commerce. I have also studied accountancy, French and the Abhidhamma and received a media fellowship in the United States in 2002.

What did you do after moving on from the film industry?

From 1993, I worked for the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) in Myanmar as a consultant producing advocacy materials. I then moved to Population Services International (PSI) in 1999 and worked there until June 2013. After retiring, I focused on my own company, Communication Services Group (CSG), which I helped found in 2000. At CSG, we provide three kinds of services. Translation services for TV content; education services including a mobile education project [providing non-formal education via mobile classrooms

to children compelled to work in teashops to support their families]; and production services [for short films and documentaries].

[In the past], the government refused to acknowledge that there were HIV/AIDS patients in Myanmar. But people were dying of AIDS. I saw it. I was especially close with many gay people in the film industry. Many of them died without knowing what they were suffering from. I felt that I needed to educate them on what was happening and how to help prevent it. I understood that I couldn’t work alone on this issue. I needed to work under an umbrella. That’s why I decided to work for PSI which had resources and funding. I started as a project coordinator earning US$450 per month. I could earn more than this in the film industry, so I wasn’t working at PSI for the money. I could learn a great deal working there.

I was criticized by one former senior government official who asked: why are you involved in this issue [raising awareness of HIV/AIDS], you are not a doctor, just an actress. But I did my best. In 2000, [annual] condom sales were just 20,000 for the entire country. By 2004, sales reached one million nationwide. I was happy with this change.

Beyond 2011, I realized that health is not the only essential issue

Even when I was working in the film industry, I wanted to gain new experiences. That’s why I studied at the same time as I was working. I became involved in making short educational films and pamphlets for health education programs with UNICEF. During these years [working in the NGO field], I was satisfied with some programs but not with others. Working with limited human resources was sometimes difficult. I met many kinds of people, including some with different mindsets to mine. But doing something is better than nothing.

In 2002, I went to the United States and met with Myanmar communities there. I asked if they would come back to Myanmar to work for NGOs and help people. Some did come back later.

What is your ongoing involvement with the film industry?

In 2012, I decided to help promote and develop the Myanmar movie industry by organizing the international relations department in the Myanmar Motion Picture Organization (MMPO). I then became secretary of the MMPO’s international relations committee. After assuming this position, some outsiders didn’t think I would be up to the task. We were not on the same page and they just worked for their own interests. I work for the people’s interests.

When I was young, I wondered why the movie industry was so commercialized and why people couldn’t work for each other. But later I realized that the film industry is totally dependent on the market and investment. In recent times, mainstream Myanmar movies haven’t been able to impact the international market. So how can we encourage independent film makers?

IN PERSON

8 TheIrrawaddy January 2015

PHOTO: STEVE TICKNER / THE IRRAWADDY

MMPO has no budget for the international relations committee. So I provide the budget myself in order for some movies to be shown in international film festivals. I define my achievements by what I have done to support the film industry in this country. I would like to encourage women to become creative directors and to try their best.

Why do you think there are now just a few female film makers?

There were some female film makers in the past. In 1940, there was Daw Khin Nyunt, then Parrot Daw Mya Mya, and following them, Daw Thin Thin Yu and Daw Wah Wah Win Shwe. The number of female film directors is small due to a lack of trust. Even in today’s environment, female directors are not trusted with the responsibility. Some [in the industry] don’t want women

to become decision makers. The majority of people working in film distribution are also men, so how can we compete with other male film makers and get our films distributed? I think some men unconsciously discriminate against their female competitors. But Myanmar women have good stamina and we prove that by working hard.

How is the MMPO working to support the emergence of more female film directors in the future?

I am encouraging women to attend script writing and directing classes which recently opened at the MMPO. I’m urging them to study seriously to become successful directors. Most actresses are just recognized as sex symbols—and the younger, the better. But if the role of women behind the camera is also recognized

and promoted, we can improve [perceptions and attitudes]. We also need mutual understanding. We need to demonstrate our abilities even as people are trying to test us.

Do you think the majority of actresses are discriminated against in terms of their earnings? For example, actors often receive more than actresses even when the latter are in leading roles.

In the 1950s, some actresses actually earned more than their male counterparts, for example, Daw Kyi Kyi Htay, Daw Wah Wah Win Shwe and Daw Moh Moh Myint Aung.

There are two things to mention. Actresses should be paid according to their abilities. They shouldn’t be satisfied with smaller wages. If women were able to produce films with their own money, there would be more female lead actors.

9 January 2015 TheIrrawaddy

Thanlwin: A River Overlooked

–Daw Aung San Suu Kyi on a proposal for 12-party talks. Speaking in mid-December, she said she supported sixparty talks.

–Daw Aye Kyaing, a resident of the Gaw Wein riverbank community that was turfed out during a visit by the King and Queen of Norway in December, speaking about how she expects the community to continue to be treated whenever VIPs arrive.

ILLUSTRATION: ATH CARTOON 10 TheIrrawaddy January 2015

QUOTES

“Mon State will become more developed as a lot of foreign visitors are expected to visit this historic place.’’

–U Naing Lwin, general manager of Tala Mon Company Limited, on the plan to create a museum and tourist facilities at the “Death Railway” site at Thanbyuzat.

“We will be shooed away like stray dogs.”

“We don’t want talks for show at all.”

Election Chief Under Fire For Coup Comments

Yangon, in which he also defended the Myanmar Army’s continued role in politics, U Tin Aye said the military would seize power in the event of political or ethnic turmoil in the country. He added that such an outcome would not be desirable.

Members of opposition and ethnic political parties responded by saying the comments were inappropriate, coming from the UEC chairman at a time when the prospect of constitutional reform is stirring considerable debate.

Senior members of political parties slammed Union Election Commission (UEC) chairman U Tin Aye for comments he made in midDecember signaling the possibility of another military coup if “instability” threatened the nation.

During remarks at a meeting with artists at the Micasa Hotel in

“He should not have said so as the UEC chairman,” said Sai Nyunt Lwin, general secretary of the Shan Nationalities League for Democracy. “The country is still in abject poverty even as the international community is giving assistance and rebuilding economic links with the country. Things will go from bad to worse if [the army] launches a coup because

of instability. He clearly intends to threaten the people by saying so.”

Any instability, according to U Aye Tha Aung of the Arakan National Party, could be handled by the country’s politicians and civil society.

“The country has deteriorated in every way because of army coups,” he said. “[He] should not say to the people that [the army] could stage a coup again. He intends to impede the progress of the country by saying so.”

Daw Phyu Phyu Thin, a Lower House lawmaker with the National League for Democracy, called on President U Thein Sein to reprimand U Tin Aye for his comments.

U Hla Swe, an Upper House lawmaker with the USDP, echoed U Tin Aye, saying the army would need to seize power if the country descended into chaos.—Nan Lwin Hnin Pwint & Pu Pu

NEWS HIGHLIGHTS 12 TheIrrawaddy January 2015

U Tin Aye, chairman of the Union Election Commission

PHOTO: JPAING/THE IRRAWADDY

ADVERTISEMENT

U Aye Ne Win Courts Controversy

he told assembled media. “What happened two or three weeks ago, it’s quite shameful.”

Govt Delays Aid to Kachin

The grandson of former head of state Gen. Ne Win courted controversy with comments he made during a memorial service for fallen Myanmar Army soldiers in Yangon on Dec. 7.

Following the service, U Aye Ne Win offered his thoughts on the prospects for a durable nationwide ceasefire agreement, laying blame squarely at the feet of ethnic armed groups.

“We still don’t have peace because the other parties [ethnic armed groups] really don’t keep their promises and act in an undignified manner,”

U Aye Ne Win told The Irrawaddy that the attack on a Kachin Independence Army (KIA) training center near Laiza in November, in which 23 cadets from armed groups allied with the KIA were killed, was evidence that ethnic armies had reneged on their promise not to increase their size.

“They have army cadets under training. That simply shows they are expanding their forces and breaking their promise,” he said. His comments were rejected by Karen National Union Secretary Padoh Saw Kwe Htoo Win.

“What he said is not true… The civil war and the conflict are due to the governments both old and new using armed power to suppress ethnic groups’ demands for their rights.” —

Kyaw Phyo Tha &

As winter approached in Kachin State, some 27,500 internally displaced persons (IDPs), including 12,000 children, were without necessary assistance such as blankets and clothes, according to the United Nations.

In a monthly aid bulletin, the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) said that the “volatile security situation and bureaucratic delays” had prevented UN convoys from being authorized to travel into rebel territory, where they regularly deliver aid to IDPs.

OCHA said that some 50,000 were still displaced in areas that were not under government control. Those unreachable communities are located near Kachin Independence Army headquarters in Laiza and east of Bhamo.

Pierre Péron, a spokesperson for OCHA, told The Irrawaddy on Dec. 17 that some aid from local organizations was reaching the IDPs, but there had been no UN cross-line missions since September. The latest UN data estimates that 98,000 people remain displaced in parts of Kachin and northern Shan states.

Lawi Weng

NLD Leader Denounces 12-party Talks

Opposition leader Daw Aung San Suu Kyi rejected a proposal for 12-party talks on constitutional reform, which was put forward in December and passed by the Yangon Region parliament.

Speaking at the fourth meeting of the National League for Democracy (NLD)’s Central Executive Committee in mid-December, the NLD leader reiterated opposition to the multiparty dialogue.

“We utterly object the steps trying to derail fruitful talks. It is important that genuine talks are held. We don’t want talks for show at all,” she said.

“If there are too many participants [in the talks], it will be hard to

understand their views clearly. We demand four-party talks, not because we don’t want the participation of many players, not because we want to restrict [dialogue], but because we want talks to be effective and pragmatic.”

The opposition leader said she would support the six-party talks proposed and passed by the Union Parliament, putting her in the same camp as the national legislature, which unanimously passed that proposal on Nov. 25.

Those talks would bring together President U Thein Sein, Myanmar Army commander in chief Sr.-Gen. Min Aung Hlaing, the speakers of

both houses of Parliament, the NLD leader and an ethnic representative.

13 January 2015 TheIrrawaddy

Nyein Nyein

Daw Aung San Suu Kyi

Gen. Ne Win’s grandson’s U Aye Ne Win (second from left) and U Kyaw Win (second from right) stand with former LtGen Tun Kyi (right) at a service for fallen soldiers in Yangon.

A camp for internally displaced persons in Kachin State.

PHOTO: J PAING/ THE IRRAWADDY

PHOTO: J PAING

/ THE IRRAWADDY

Thuzar & Nan Lwin Hnin Pwint

PHOTO: JPAING / THE IRRAWADDY

14 TheIrrawaddy January 2015

Life After Tsunami

A son of a migrant fisherman from Myanmar rests in a hammock at a former shrimp warehouse where his family lives in Ban Nam Khem, a small fishing village on Thailand's Andaman Sea coast. The village lost nearly half of its 5,000 population in the Asian Tsunami that killed at least 226,000 people in 13 Asian countries and Africa in late December 2004. Ten years later, Ban Nam Khem is home to a large migrant workers' community, most of whom are from Myanmar.

IN FOCUS

15 January 2015 TheIrrawaddy

PHOTO: REUTERS

Light at the End of the Tunnel?

There is no shortcut to a free and prosperous country

By AUNG ZAW

People are saying that it is difficult, these days, to stay optimistic about the immediate future. My friends who are Buddhists say nothing is permanent, and so they wait patiently for things to change.

Sure, change will happen, but how and when? Since reforms began in 2011, it has often been hard not to feel as though one were watching a badly produced Hollywood movie, with a flawed plot, a poorly written script and a cast of incongruous characters.

In the long run, I keep telling myself, things must get better. But meanwhile, many of my friends feel that our generation will not see what we wish for: a free, prosperous and united Myanmar with a federal system, governed by the people. The kind of Myanmar envisaged by independence leader Gen. Aung San all those many decades ago.

So what hope is there for the year ahead? According to a nationwide public survey conducted by The Asia Foundation in Myanmar, 62 percent of respondents are generally positive about the direction the country is heading in, while 77 percent believe

that planned democratic elections will bring about positive change.

The non-profit organization carried out interviews with more than 3,000 respondents in the regions and states, asking a wide range of questions concerning government, democracy, and the political, social and economic values of people from various ethnic and religious backgrounds.

“The survey results show that in the early stages of Myanmar’s transition to democracy, people are generally hopeful about the future, though that optimism is tempered by a number of challenges,” The Asia Foundation said.

My blood flowed a little more freely after reading this, though doubts lingered. As the Foundation points out, a number of challenges do indeed remain. Signs of government backtracking include renewed fighting in ethnic regions; a clampdown on independent media; the unchecked rise of religious extremism and tension between Buddhist and Muslim communities; and the military’s ongoing role in politics.

As I mentioned in a recent speech in New York to accept an International Press Freedom Award from the

Committee to Protect Journalists, Myanmar is a land of green. I was not referring to its beautiful forests and trees. Rather, I meant that those in uniform continue to rule the country.

In November, a colleague in his early fifties, who works at an international organization in Yangon, told me, “We have the potential to grow, but it is being squandered [by leaders].” The optimism we felt over the past few years has slowly been fading away.

In reality, many people feel that they have no power to institute the change they want. This is the real problem. Moreover, fear of the unknown is still pervasive. This fear can be found among top leaders, who are afraid of

VIEWPOINT

16 TheIrrawaddy January 2015

PHOTO: SAI ZAW / THE IRRAWADDY

losing political and economic power. It is also present among ordinary people who fear that the status quo will endure.

Amid the growing concerns over the reform process, Myanmar continues to attract investment and international recognition. On his trip to the country in November for the ASEAN and East Asia Summits, US President Barack Obama said that the democratization process was “real.” The US has also opened the door to small-scale military to military engagement.

Other donor countries continue to pledge more aid and investment. The European Union recently announced it would send US$900 million in aid

to Myanmar over the next seven years. Many international actors seem convinced that the situation in Myanmar is, inexorably, improving. A colleague who has worked in various aid agencies told me that within the international community, “Everyone is drinking the Kool-aid. They try hard to convince themselves that they are working for solutions in the country.”

Notwithstanding The Asia Foundation’s survey results indicating that the majority of respondents feel positive about the country’s prospects, it is my experience that many people feel the immediate future looks bleak.

After the ups and downs of 2014, we still hold out hope for fundamental

change. There are small glimmers of light amid the darkness. As the survey found, although fears of expressing political views in public continue to linger following decades of military rule, 93 percent of respondents said they would vote in the upcoming elections.

So what will 2015 bring? There will be no overnight miracle or shortcut to a free and prosperous country. We continue to tell ourselves to remain cautiously optimistic, but this is really only a defense against deep disappointment.

17 January 2015 TheIrrawaddy

Aung Zaw is the founding editor-inchief of The Irrawaddy.

A child walks by posters of Myanmar independence leader General Aung San at an event at Maha Bandoola Park in Yangon in midDecember. The year 2015 marks the centennial of the birth of the national hero.

The Kola of Cambodia

A Buddhist pagoda and an elderly woman are among the last traces of a group of mysterious Myanmar migrants

By SIMON LEWIS & PHORN BOPHA / PAILIN PROVINCE, CAMBODIA

“When I was growing up, everyone around here was Kola,” said Chhoeum Davy, sitting beneath the Buddhist pagoda of Wat Phnom Yat.

The golden tower is in the style of those found all over Myanmar, but it sits atop a hill overlooking Pailin in northwest Cambodia. It is almost all that’s left here of the Kola, the group of migrants from Myanmar who built it.

The precise origins of the people and their name, sometimes spelt Kula, are unclear. They are thought to have journeyed here in caravans from somewhere in Shan State and came to control the local gem-mining industry. Cambodian accounts suggest they first

arrived in 1876, while the area was part of Siam.

“They were very rich. They had bowls full of gold and gems,” said Ms. Davy, a 59-year-old Khmer woman who looks after the pagoda. Kola middlemen would carry a bell to ring as they were coming around the villages, telling gem miners to bring out their wares, she recalled.

At Wat Phnom Yat, statues depict Kola men wearing a garment like a longyi, hinting at the group’s ancestral homeland.

“The men dressed like Khmer men, but they wore sarongs. The women had a traditional double-breasted blouse, with platinum or gems for buttons, and beautifully embroidered sleeves,”

said Ms. Davy. “They used umbrellas, chewed betel nut and kept their hair very long.”

Among the painted names identifying those who have donated to the pagoda and a nearby monastery are Myanmar names, since some have come to see Wat Phnom Yat as a site of pilgrimage. Brand-new gold plating and gold leaf for the pagoda were donated by people from Myanmar last year, Ms. Davy said.

Around the pagoda are gruesome scenes from Buddhist purgatory, a tall standing Buddha, and—attracting the most Cambodian visitors—statues of a Kola woman, Yeay Yat, after whom the hill and the pagoda are named.

Her story is recorded in a Khmerlanguage collection of folk tales compiled by the country’s Institut

January 2015

FEATURE

Scenes from Buddhist purgatory are depicted at Wat Phnom Yat

Bouddhique. It recounts that Grandmother and Grandfather Yat— Yeay Yat and Ta Yat—were gemstone traders in Pailin.

Due to the lucrative gem business in the area, the story goes, many locals had firearms to protect their property. But they also used the guns to hunt animals in the then-thick forests surrounding the town of Pailin—a practice which scared local spirits.

One day, the most powerful spirit in the area visited Yeay Yat and Ta Yat and offered them a bargain: If they got the people to stop hunting, the spirit would see to it that the people would find more gemstones. The hunting ceased and the people grew richer, repaying the spirit by donating generously to build Wat Phnom Yat and performing a “peacock dance” atop the hill for the spirit.

Local people now believe that Yeay Yat’s spirit can grant wishes in return for offerings. The spirit of Yeay Yat is known to possess people in Pailin from time to time, said Ms. Davy, who sells laminated images of the Kola matriarch at the pagoda. “Whenever her spirit enters somebody’s body, they speak in Kola [language],” she said.

Like most of the precious gemstones and forests that once enriched this area, the Kola fell victim to the Khmer Rouge, the ultra-Maoist group that ravaged Cambodia from 1975-79. After fleeing Phnom Penh, the Khmer Rouge retreated to Pailin and other redoubts near the Thai border to wage an insurgency that lasted through to

19 January 2015 TheIrrawaddy

“At Wat Phnom Yat, statues depict Kola men wearing a garment like a longyi, hinting at the group’s ancestral homeland.”

Images of the storied Kola matriarch Yeay Yat

ALL PHOTOS: SIMON LEWIS

the late 1990s, largely funded by sales of gems and timber to Thai merchants.

While in power, the Khmer Rouge abolished money and confiscated all property for the state, forcing the Cambodian people into collective work camps and especially victimizing those who were considered wealthy or educated. More than 1.7 million people are thought to have died in just over three years before a Vietnamese invasion ousted the regime.

But among the reams of literature about the country’s killing fields, little mention is given to the fate of the Kola. “They tried to run away to Thailand, but I don’t think many made it,” said Ms. Davy.

The pre-civil war population of Kola in Pailin would have been tens of thousands, she said, but it now stands at just one, an elderly woman widely known as Yeay Kola. The frail 77-yearold, whose real name is Sein Tin, visits

the pagoda most days. “Whatever you ask from Yeay Yat, you will get it. She was a woman who took care of the people,” Sein Tin told The Irrawaddy at her home, only meters from Wat Phnom Yat.

“All were Kola around here,” Sein Tin said sadly, indicating the hilly surrounds and the monastery opposite, built in the Myanmar style using wood with metal roofing. “The Khmer Rouge kicked all the Kola out… They mistreated them. They had to exchange all their property for rice, so they were poor. Then, if they stole, they were killed.”

Sein Tin fled the area and hid in the nearby town of Battambang, returning later to find that all the Kola had gone. “I survived only by luck. But I am the only one left here,” she said.

Local officials in Pailin are almost all former Khmer Rouge soldiers, since Pailin was only carved out as an administrative area, for the benefit of former cadres, in 1996 after a massive defection that presaged the group’s demise.

Sao Sarat, the deputy governor of the province and a former Khmer Rouge fighter, denied that any Kola had been killed by the communist army.

“The war came and they ran away,” said Mr. Sarat, insisting that the entire former population of the area was safely living in Thailand. “Some of them have even come back to visit.”

The Khmer Rouge Tribunal in Phnom Penh is now trying two former regime leaders for crimes that include genocide against the Muslim Cham and the Vietnamese minority in Cambodia. Youk Chhang, executive director of the Documentation Center of Cambodia, said that it did not appear the Kola were specifically targeted by the Khmer Rouge, as were the Cham and the Vietnamese.

As well as settling across the border in Thailand, he said, some were known to have migrated to Phnom Penh and to the United States. However, others likely died from starvation, overwork or during the purges that wracked Cambodia during the Khmer Rouge era.

“They [Kola] look like Khmers, so many probably died along with everyone else,” Mr. Chhang said.

20 TheIrrawaddy January 2015

The last of the Kola living in Pailin, 77-yearold Sein Tin Chhoeum Davy, 59, looks after Wat Phnom Yat and sells laminated images of Yeay Yat

FEATURE

The gold-plated pagoda at Wat Phnom Yat

January 2015 Irrawaddy

Brides for Bachelors

Lured by false promises of employment, women and girls from Myanmar, including ethnic Ta’ang, continue to be trafficked to China

By BRENNAN O’CONNOR / LASHIO, SHAN STATE

Lway Mai cradles her head in her lap. She looks exhausted after a bumpy ride from the border town of Muse to Lashio in northern Shan State.

Her uncle is sitting nearby, talking to several male friends of their family. A major crisis has been averted. There is finally time to reflect on what just happened, and how much worse it could have been.

Hours earlier, the 18-year-old ethnic Ta’ang teenager and her friend Lway Nway, 16, were being held in a hotel room in Muse. The pair had traveled from their village several hours away with a woman who promised them work in China.

At the Muse hotel, they became scared. One of the young women found a way to call her parents, who in turn contacted the Ta’ang Students and Youth Organization (TSYO). It then helped the teenagers to get from Muse to Lashio, where the organization has an office.

Mai Naww Hment of the TSYO suspected the girls had just had a lucky escape from traffickers who planned to sell them as brides to bachelors in China.

China’s skewed male-to-female ratio, exacerbated by the one-child policy and a traditional preference for male children, has meant that millions of Chinese men cannot find partners. Chinese bachelors often wind up paying marriage brokers to do it for

them. Some of these entice women and girls from neighboring countries with false promises of employment in China.

In this instance the brokers lured the two teenagers away without informing their parents. The young people trusted the older woman, and why wouldn’t they? She was originally from their village. Her mother still lived there.

It is not uncommon for human trafficking rings to hire brokers from the same village as their victims, said Mai Naww Hment, in between juggling phone calls to the girls’ anxious parents and discussing plans to get them home with their uncle.

The coordinator for TSYO’s Information and Human Rights Documentation project said that this strategy had arisen after villagers began distrusting strangers as girls began disappearing.

“Now the traffickers are trying to use people from the villages who have good contacts,” Mai Naww Hment said.

The young women probably thought it was

“very attractive” when the well-dressed woman arrived in their village offering them work in China, he added. “They thought that if they followed her, they would get good pay.”

In Mai Naww Hment’s own village in Kutkai Township, three women are missing.

This happened, he said, after a local man had returned from China promising work to a group of youngsters. Six youths followed him to a hotel in Muse. When they arrived he put the boys and girls into different rooms. When the boys woke up the next morning the man and the girls were gone, presumably across the border. That was at least four months ago and the families still haven’t had any contact with their daughters.

The UN Inter-Agency Project on Human Trafficking estimated that 70 percent of Myanmar’s reported trafficking cases in 2010 involved women and girls being sold as brides to Chinese men. More recent reports from Myanmar’s police force provide an even higher figure, at 80 percent of all trafficking cases.

FEATURE

22 TheIrrawaddy January 2015

Loss of Livelihood

The Ta’ang, also known as the Palaung, have traditionally derived the bulk of their income from cultivating tea. But around five years ago, Chinese companies began flooding the local market with cheaper tea. Prices have plunged to levels so low that it has essentially destroyed the livelihood of the Ta’ang who are unable to compete with the larger Chinese firms.

As tea prices dropped, opium cultivation skyrocketed. In many regions where Ta’ang people live, governmentbacked militias encouraged the switch to poppy-growing.

The drug lords who run these militias often encourage workers to become addicted to yaba, supposedly because it makes them work harder and longer. Once workers are addicts, it’s much cheaper to simply pay them in drugs, Mai Naww Hment said.

As a result, drug addiction rates among Ta’ang men are spiraling out of control. A Palaung Women’s Organization report entitled “Poisoned Hills,” found that in one village

surveyed in Mantong, the percentage of men aged 15 and older who were addicted to opium increased from 57 percent in 2007 to 85 percent in 2009.

To make matters worse, many Ta’ang communities have been attacked by government forces because the Ta’ang National Liberation Army has allied itself with the Kachin Independence Army, an ethnic armed group engaged in renewed conflict with the Myanmar Army since June 2011. The fighting has devastated many villages in Kachin and northern Shan states and displaced around 100,000 people—mostly women and children— leaving them “highly vulnerable to forced labor and sex trafficking,” according to the US State Department’s 2014 Trafficking in Persons (TIP) report.

Lack of Government Action

The Myanmar and Chinese governments have vowed to work to combat the growing crisis of human trafficking and they recently signed a memorandum of understanding recognizing human trafficking for purposes of marriage as a major concern.

China has created an Anti-Trafficking Office under the Ministry of Public Security. Along with other ministries and NGOs it now provides temporary relief for trafficking victims at several key points along trafficking routes. However, only females and underage males are eligible for protection. Adult males aren’t recognized as trafficking victims under the office’s criteria. Eligible victims are provided with financial support and a border pass to ensure their safe return to Myanmar.

In Myanmar, the government launched a five-year National Action

Plan to Combat Human Trafficking in 2012 with an annual operating budget of US$780,000—covered mostly by international NGOs. As part of the plan, Myanmar created an Anti-Trafficking in Persons Division (ATIPD) within the country’s police force that was designed to coordinate the activities of Myanmar’s Anti-Trafficking in Persons Unit, established in 2004, as well as 26 Anti-Trafficking Task Forces based in trafficking hot spots.

There are now over 1,000 antitrafficking police officials either working on trafficking cases within Myanmar or stationed overseas as antitrafficking attachés, according to the Global Slavery Index 2013. However, the 2014 TIP report noted that pervasive corruption and a general lack of accountability in Myanmar affected the enforcement of trafficking laws and that police “limited investigations when well-connected individuals were alleged to be involved, including in forced labor or sex trafficking cases.”

The report said that there were still “isolated reports” of Myanmar government officials complicit in the trafficking of women to China. In two cases, the report states, the International Labor Organization reported the alleged involvement of the wives of military officials in a human trafficking ring. But “No action was taken to prosecute the suspected offenders,” it noted.

Mai Naww Hment and his fellow TSYO members aren’t holding their breath for the government to improve the situation for Ta’ang communities. His team has organized public awareness campaigns on human trafficking and mobilized anti-human trafficking teams that can be called upon in cases like that of the two Ta’ang teenagers.

Last year, the TSYO also opened a new boarding school in Lashio for impoverished Ta’ang youth. Mai Naww Hment hopes that in the future a solid education will give Ta’ang youths like Lway Mai and Lway Nway the confidence and life skills they need to avoid being duped by human traffickers.

—T he names of the women in this article have been changed.

A woman looks over the view at a remote Ta'ang village. There are few opportunities for young people in many ethnic Ta'ang villages

23 January 2015 TheIrrawaddy

PHOTO: JPAING / THE IRRAWADDY

Rewards and Risks for Bar Dancers

Young men from poor villages in Shan State earn a living as sex workers in gay

“show bars” in northern Thailand’s largest city

By KYAW KHA / CHIANG MAI, THAILAND

In the backstreets of Chiang Mai near a roadside bar, a man in a dark suit discreetly pointed us to a door dimly lit up by a red light. As we entered we were welcomed by upbeat disco beats.

On a small stage, around 20 young men in tight white briefs were dancing under disco lights. They were good looking and appeared young. The oldest were perhaps 25 years of age, while others looked like they could be teenagers.

Dozens of customers, mostly Western men, sat at tables around the stage, drinking, smoking and reveling in the lively maneuvers of the dancers.

During a break, four dancers joined our table—all from neighboring Myanmar. Their heavy accents quickly revealed their Shan background and the young men said they came from Shan State’s Panglong, Loilem and Mong Nai townships.

“The boss [of the club] is English. All the dancer boys are from Myanmar. Most of them are Shan and some are ethnic Lisu, Lahu and Akha,” said one of the dancers, adding that all had come to Thailand and entered the gay bar scene in order to support their families in their impoverished native villages.

Thailand is home to between 2 million and 3 million Myanmar migrant workers, and northern Thailand has long been a destination for many

seeking to leave Shan State. Migrant workers often perform low paid, unskilled labor in sectors such as construction, manufacturing, tourism and fishing. Many risk running afoul of the law because they lack proper legal documentation and working permits.

The dancers in Chiang Mai’s gay “show bars”—of which there are four, according to one guidebook—are at constant risk of arrest by police as their work is illegal under Thai law.

Cheers from the crowd focused our attention on the stage, where a wellbuilt, tall dancer going by the show name Ai Long was doing a naked solo dance to a slow melody.

A little later, he came to our table. The 23-year-old said he grew up in Loilem Township in an area under the control of ethnic Shan rebels. When he was about 14 years old, his parents feared that he might be conscripted by the rebels and they sent him to live with a relative in Chiang Mai.

Five years ago his financial situation became dire and he entered into sex work at the bar. “I’ve been here for a long time and no one here speaks the Myanmar language. As time passes, I’ve begun to forget some words,” he said.

For the Family

Ai Long said he is the top earner among the dancers and popular among

the bar’s Western visitors due to his physical characteristics and good looks. He said he earns a monthly salary for his act of around US$1,500.

The other dancers earn between $600 and $1,200 per month, while many earn more from selling sex, for which they charge around $100 per night, according to Ai Long, who said that the owner of the club also earns a $10 fee for such services.

Later in the conversation Ai Long revealed that he is married and has a wife and a four-year-old son in Loilem. Like most of the Shan men at the club, he says that he is not gay but does the work because it pays well and allows him to send money to his family, adding that five of the club’s 20 dancers are married.

Ai Long said he and many of the dancers do enjoy the work but are not

FEATURE

24 TheIrrawaddy January 2015

proud of it—he has told his family and friends that he works as a waiter in Chiang Mai.

“Uneducated people like me can find no way to lead a decent life, even if we work very, very hard. When I have capital to start a business, I will go back to Loilem and live with my family,” Ai Long said.

He held up a photo on his smartphone showing a picture of his wife and son. “I will send my son to

the school in Loilem. I will make him an educated person; I don’t want my son to lead a hard life like me,” he said, holding back tears.

Health Risks

The sex work is not only a difficult job; it also exposes the young men to serious health risks, such as sexually transmitted diseases (STD) and drug abuse. Some of the men use cheap

methamphetamine tablets, also known as yaba, to help them stay awake during the night time dancing or sex work.

“Most customers do not like quick sex and don’t want to give money and won’t call you next time if they are not satisfied. If customers are satisfied, they give tip money. So, some [sex workers] use yaba to last longer,” said Ai Long, adding that it was common practice.

The dancers said most customers will have protected sex, but it’s not unusual for customers to try and force the dancers to have unsafe sex, exposing them to the risk of contracting STDs.

Sai Han said he contracted unspecified STDs on four occasions, twice from having unprotected sex with male customers during nights of heavy yaba use, while he also contracted STDs twice while paying for sex himself with female prostitutes. “Now, I always use condoms, either when having sex with male customers or female sex workers, and I rarely use yaba now,” he said.

The dancers said they knew of no case where a fellow male sex worker had been infected with HIV/AIDS, although infection with other STDs was common.

Mplus, a Chiang Mai-based organization working for the rights of same-sex couples and raising HIV/ AIDS awareness, often visits the gay show bars to educate sex workers about the health risks.

A staff member at the NGO said HIV/AIDS infection had occurred in the past among workers, but no case had been reported in the past year or so, possibly as a result of the expanding awareness-raising programs.

The NGO worker, who asked not to be named, said he was conducting a survey among male sex workers to research health issues. He had found that many of the young men who became infected failed to seek proper health treatment.

“Male sex workers are too shy and fear having their occupation exposed, so are reluctant to go to a clinic when infected with sexually transmitted diseases. Everyone says they are not infected with HIV/AIDS, but no one wants to have their blood tested,” he said.

Ai Long, a top dancer, says he earns up to $1,500 a month for his act. This allows him to send money home to his family.

A young dancer in a Chiang Mai 'show bar'

25 January 2015 TheIrrawaddy

PHOTO: THE IRRAWADDY

Hiroshima Survivor Still Searching For Victims

A-bomb survivor and keen local historian

By THIN LEI WIN / HIROSHIMA, JAPAN

Every weekend for more than 20 years, Shigeaki Mori sat in the hallway of his compact two-storey home making calls to people in the United States, asking, “Do you have a family member who died as a prisoner of war in Japan?”

He was searching for the families of 12 American POWs who died on Aug. 6, 1945, when the United States dropped an atomic bomb on the Japanese city of Hiroshima.

It was not until the 1970s that declassified US documents indicated the presence of the POWs in Hiroshima on that day. In the 1980s, Satoru Ubuki, a local university professor, found their names and passed them on to Mori, a keen local historian.

An A-bomb survivor himself, Mori was determined to inform the families of what happened to their kin—many were not told the exact nature of the deaths— and he believed that the soul of the dead should be respected and remembered.

It was an arduous process—and one that is not over yet as Mori is now tracking down the details of British and Dutch POWs he believes also died in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, which was bombed three days later.

To find the American families he only had the surnames to go by so rang everyone he could find with that name, one by one.

“I had a map from Seattle to Texas ... It took me about three years [to find one family],” Mori, 77, said via a translator in the cluttered living room of his home in a Hiroshima suburb, sitting ramrod straight, hands on his lap.

With his limited English he prepared a questionnaire and, if he found the person had something to do with the POW, he asked the telephone operator to help, he recounted, laughing.

“It took me over 20 years... I cannot remember how many I called,” said Mori, a retired securities broker.

It was also costly. He would rack up monthly phone bills of 60,000 or 70,000 yen (around US$250 to $300 in the 1980s).

Yet his tenacity paid off. He successfully contacted 11 families and registered the POWs with the city authority.

Their pictures in the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Hall among a sea of Japanese victims are a stark reminder of the bomb’s indiscriminate nature, a message Mori wanted to convey.

Mori, of slight build, serious and the epitome of Japanese stoicism, wears the achievement lightly on his sleeve.

“What I did was just what the families had to do but they had no clue

Shigeaki Mori continues his painstaking search for the details of POWs killed in the atomic bombings in Hiroshima and Nagasaki

26 TheIrrawaddy January 2015 REGIONAL

A video frame grab shows Shigeaki Mori, 77, at his home in Hiroshima.

how. They say they really appreciated me contacting them. I was really glad to hear their words,” he said.

“I’m now researching about Dutch and British POWs, not just in Hiroshima but also Nagasaki.”

Hibakusha Tales

Mori says the whole process was cathartic for him too.

Eight-year-old Mori was on his way to summer classes when the world’s first nuclear attack occurred.

“As I was walking on [a] bridge, suddenly I felt a massive shockwave and a blast from above. I was blown off the bridge and fell into the river,” he recalled.

Luckily the river was shallow and plants broke his fall but two other people on the bridge were burnt badly and one died. After he regained consciousness, the morning was black.

“I couldn’t even see the 10 fingers on my hands,” he said, raising his palms for

emphasis. He crawled out of the river and saw a woman walking towards him.

“She was swaying ... and holding something white. I realized she was holding the contents of her stomach.”

The sounds of B-29 bombers filled the air and Mori, thinking another bomb was on the way, ran, stumbling over corpses. He spent that night in an air raid shelter next to his former primary school, hungry, thirsty and terrified.

“That night was like hell ... Many people were in the schoolyard yelling in agony. There was nothing to eat or drink.”

The death toll from the blast was estimated at about 140,000 by the end of the year, out of the total of 350,000 who lived in Hiroshima, 700 km (435 miles) southwest of Tokyo, at the time.

The bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki remain the only use of nuclear weapons in war.

The survivors, called hibakusha , continue to suffer the effects of radiation.

Mori’s family struggled with bad health throughout their lives. Mori himself has problems with his kidney, liver and heart that prevent him from long-haul air travel.

The hibakusha were criticized as being lazy—chronic fatigue is another consequence of radiation—and discrimination was rampant. Young women and men feared identifying themselves as they would have no suitors.

Mori’s wife, a classically trained pianist and singer, is also a hibakusha They have two grown-up children.

Forgiveness

The shadow of the bomb still looms large in modern-day Hiroshima, a thriving, bustling city crisscrossed by six rivers.

The peace park covers a large portion of the town centre and includes a cenotaph with the inscription: “Let all the souls here rest in peace, for we shall not repeat the evil.”

Mori, who published a book in 2011 about the American POWs, is a pacifist like many hibakusha and worries the world is far from achieving peace.

“We should learn from the loss of lives in Hiroshima... If war continues, people will suffer,” he said.

The feelings of revenge against the United States have largely dissipated, Mori said, mainly because the US occupying forces provided muchneeded food when the survivors were hungry.

“I have complex feelings about it but it was so difficult for us to survive at the time. We appreciated American help.”

In 2012, Mori met Clifton Truman Daniel, grandson of Harry Truman, the US president who ordered the attack on Hiroshima.

“I felt like I was in a dream. I’m a victim of the atomic bombing and while he is not the person directly involved in it, he’s the grandson of the man who ordered [it],” he said.

“Now we shook hands, smiled and laughed. I cannot describe how moved I was. This is peace, I told myself.” — Thomson Reuters Foundation

A child pays respect at the cenotaph at Hiroshima Peace Park in November.

27 January 2015 TheIrrawaddy

ALL PHOTOS: REUTERS

Magyizin Village, Inle Lake, Shan State, Myanmar Tel & Fax: +(95-81) 209055/ 209364/ 209365/ 209412 Mobile : (95-9) 525 1407, 525 1232 A restful retreat to nature on Inle Lake surrounded by Shan Hills Preserving our heritage to transmit to the future generation as received from ancestors Inpawkhon Village, Inle Lake, Shan State, Myanmar. Reservation: +95 - 9 4931 2970 Mobile: +95 - 9 528 1035 Email: intharheritage@gmail.com ADVERTISEMENT 30 TheIrrawaddy January 2015

Business

GOING FOR GROWTH

The UMFCCI's vice chairman talks about economic prospects and pitfalls

PHOTO: STEVE TICKNER / THE IRRAWADDY

INTERVIEW ENTERPRISE SURVEY SIGNPOSTS ECONOMY: Enterprise survey provides insights

Despite much vaunted economic reforms since 2011, some observers have noted that Myanmar’s economy is underperforming. In the lead up to national elections slated for late 2015, economists and business leaders have also voiced concerns that possible political instability could hamper economic progress. Dr. Maung Maung Lay, the vice chairman of the Union of Myanmar Federation of Chambers of Commerce and Industry (UMFCCI), spoke with The Irrawaddy’s Kyaw Hsu Mon on the prospects for growth in a crucial year ahead.

Last January, President U Thein Sein said the country was targeting 9.1 percent GDP growth for 2014-15. Do you think this is likely?

President U Thein Sein’s statement was optimistic. The facts and figures which he referred to are more favorable than I’ve seen. [Even] the president’s economic advisor U Myint recently said that this economic data might be incorrect. As you know, the government has often politicized data. That’s why the government’s Central Statistical Organization has now been reconstructed in order to gather quality data. Past data might be incorrect because it was not systematically collected through township offices. If the data collection process is poor, the resultant facts and figures will also be incorrect. We need accurate figures. At the moment, the data collection system is improving and is not so different from that of other organizations like the World Bank or the Asian Development Bank.

When do you expect Myanmar will graduate from least developed country (LDC) status?

We can count the countries that have graduated from LDC status. Some observers have indicated that Myanmar has many requirements to fulfill before it can graduate from LDC status, and that will take time. Some expect it may take at least 5-10 years. If we try our best, dreams will come true. But it’s not possible to simply move from LDC status at once.

Are factors such as the tax rate, the trade deficit and other aspects of trade policy a major barrier to this?

It is due to all these factors. We need to improve across all sectors. We still need to improve on a micro and macroeconomic level in our country to develop the economy.

Is the UMFCCI acting as an independent body?

We’re now elected by members so it is independent. In the past, we were advocating for the government. Now we not only advocate, we also make claims to the government on what our members want and on the requirements of international standards. We’re trying to upgrade our members’ capacity and closely follow international economic trends.

How do you collaborate with the different government ministries?

UMFCCI is currently working with all sectors. Collaboration with government ministries is getting better. They’re listening to the UMFCCI’s input and suggestions in order to help solve problems. We have a good mutual understanding and are working well together.

What do you think of the claim that high tax rates are making it difficult for some businesses to compete with regional competitors?

The government has recently decreased some taxes for local businesses to encourage production. According to international guidelines the government shouldn’t always protect local businesses, but here, the government is protecting some small businesses. It’s true that commercial tax rates are still high. People are criticizing the 5 percent commercial tax

rate for consumers and manufacturers. However, the government collects less tax compared to other countries. How will the country’s infrastructure improve [without higher taxes]? People need to know the advantages of paying tax to the government.

Why is Myanmar’s trade deficit on the increase?

Many countries have this kind of trade deficit, but the amount is different. [In Myanmar] imports are higher than exports. We need to negotiate gradually to reduce the trade deficit. But the country is still surviving despite this

32 TheIrrawaddy January 2015 BUSINESS INTERVIEW

issue. It’s only about a US$2 billion deficit in Myanmar. It’s not a serious problem, but some have said so because the country has never reached this level of deficit before.

How will the economy fare this year when the ASEAN Economic Community (AEC) begins, since there will be more tax-free imported goods flowing into the country?

The trade deficit will increase this year. The government needs to encourage local entrepreneurs but not provide trade protections that

are against World Trade Organization rules. It’s difficult to balance exports and imports. Government ministries will have to work together. The AEC should actually mark the end of the beginning for us. Not the beginning of the end. I’ve warned that it should not be seen as negative for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). More than 80 percent of our businesses are SMEs. What’s needed is good corporate governance. Otherwise, we will be overwhelmed by our competitors. The government should also control the rate of inflation next year. We need comprehensive policies.

Have the UMFCCI and the militaryowned Myanmar Economic Corporation collaborated?

No we haven’t. They are an independent entity. We have invited them for some workshops and business discussions with foreign trading partners, but they rarely attend.

Do you agree that Myanmar’s Central Bank is not standing up for local businesses? What is your personal opinion?

The Central Bank has been working under the Ministry of Finance for a long time. Now they are trying to emerge from its shadow. The bank’s leading officials are good people. We aren’t too critical of them. They are relatively independent compared with the past. I hope [the Central Bank] will gradually improve.

Some people are concerned that Myanmar’s economy may be impacted by political uncertainty this year. What’s your view?

I don’t think it will be impacted by the political situation. People will be trying to win over voters by campaigning hard but they will be more focused on political rather than business issues. Some will pledge to do more in order to be reelected. Almost all countries in the world tend to move cautiously in election years.

Whether or not we’re ready for the AEC may become a political issue. The next government may face problems [concerning the AEC]. Some officials have indicated they’re prepared for the AEC but it will be hard to implement. Even Thailand is still trying to prepare for it. We will have to do more, practically and mentally.

33 January 2015 TheIrrawaddy

U Set Aung, Myanmar's deputy central bank governor, speaks to the media during a news conference at the Central Bank in Naypyitaw on Oct. 1.

PHOTO: REUTERS

Hurdles and Wins for Emerging Business

World Bank data revealed significant issues facing new firms in Myanmar but said “spectacular sales growth” awaits if economic reforms continue

By WILLIAM BOOT / YANGON

Lack of finance and access to land; poor infrastructure support including access to electricity; corruption; and a poorly educated workforce are among the biggest hurdles in trying to establish a business in Myanmar.

These issues were highlighted in the latest Enterprise Survey data published by the World Bank and underline the concerns voiced by many observers over the country’s economic and social development. Enterprise Surveys provide comprehensive company-level data on the business environment in developing economies around the world.

The World Bank interviewed representatives from 632 firms between February and April 2014, asking for feedback on 15 issues, ranging from finance to social disorder, taxation, political stability, legal matters and bureaucratic red tape.

“Among 15 areas of the business environment, firms in Myanmar are more likely to rate access to finance to be the biggest obstacle to their daily operations, followed by access to land, electricity, and then poorly educated workers,” the survey concluded.

Lack of finance for new businesses is one of the biggest challenges to growth. Myanmar rates as one of the poorest in financial services across the entire AsiaPacific region, the survey said.

“The proportion of firms with a checking or savings account is 30 percent which is less than half the average for low income countries.

Access to credit through banks is worse still. Only 7 percent of firms report having a bank loan which is one-fifth the level for [regional] or low income countries,” the survey said. “Less than 2 percent of investments are financed

from banks, slightly over a tenth of the [regional] average.”

The survey found that corruption was much more prevalent in Myanmar than in other countries of the East Asia and Pacific regions surveyed.

34 TheIrrawaddy January 2015 BUSINESS ENTERPRISE DATA

A worker at the Yangon port

“Almost one out of two Myanmar firms experience at least one bribe payment request across six transactions dealing with utilities access, permits, licenses, and taxes,” the World Bank said. “The private sector experiences almost twice the incidence compared to other [regional] countries.”

Fifty-six percent of firms reported being expected to give gifts or payment to get an electrical connection and 53 percent reported the same to get an import license.

The survey “more or less formalises what is widely understood on the ground,” Australian economist and

much of the fundamentals—the soft and hard infrastructure that determines the business and economic ecosystem— remain insufficiently reformed,” said Dr. Turnell, a professor at Macquarie University in Sydney.

“These fundamentals include access to finance, the ease or otherwise of securing ‘permissions’ for business activity, the reliability of electricity and energy, access to skilled labor, and so on.

“Of course, this is also the hard stuff that takes a long time to fix. Five decades of neglect in these areas is not easy to turn around. What’s important is that these fundamentals are addressed, and not simply the window dressing.”

Consult-Myanmar, a Yangon based Singapore-owned business advisory company, describes Myanmar along with Cambodia and Laos as frontier markets that “lack the regulatory and financial institutions found in other more economically developed destinations in the region such as Malaysia and Thailand.”

It said the findings of another recently published World Bank study, Doing Business 2015, “make abundantly clear” that business problems abound in many parts of Southeast Asia.

“While Singapore continues to rank No. 1 in the world for ease of doing business, many of the region’s so-called frontier economies continue to be characterised by pervasive corruption, and weak governance and rule of law.”

Nevertheless, Consult-Myanmar, founded by Singapore businessman Andrew Tan, believes foreign investors are attracted to Myanmar by its “young demographic base, growing middle class, and strategic location.”

about the consequences of violating anti-graft laws; understand and address the challenges of corruption’s close cousin, cronyism; and don’t be afraid of walking away from a deal if it doesn’t look right.

Global business risk assessor Business Monitor International said in a recent assessment that a “lack of information and timely economic data on Myanmar remains a key factor preventing foreign investors from assessing the true potential of the economy.”

“Uncertainties as to the government’s direction on economic policies pose additional risks to business investment in Myanmar,” the UK-based firm said.

The World Bank Enterprise Survey also found that domestic and foreign firms are reluctant to invest in training employees.

“Only 15 percent of firms do so, almost one-third of the average for East Asia and Pacific, and close to half the average for low income economies. However, among firms that do offer training, about the same proportion of workers are trained compared to other low income countries,” the survey said.

But despite the difficulties impeding the establishment of successful businesses, the World Bank remains upbeat about Myanmar’s progress— provided reforms continue.

“Private sector firms in Myanmar have reported spectacular sales growth since the onset of a series of government-initiated policy reforms in 2011,” the survey said.

“Myanmar remains a very difficult place in which to undertake and perhaps above all start a business. To some extent too, [the survey] highlights that

The company suggests that wouldbe investors in Myanmar should follow a set of basic rules: adopt a realistic timeline for development; leverage local talent; educate local partners

“A 24 percent real annual sales growth rate puts Myanmar in the fastest growing private sectors as measured by Enterprise Surveys… Importantly, this remarkable sales growth took place despite great hurdles, which is suggestive of continued growth that could be unlocked by further reforms.”

PHOTO: STEVE TICKNER / THE IRRAWADDY

Enterprise survey is upbeat on progress, provided that reforms continue

Myanmar specialist Sean Turnell told The Irrawaddy.

35 January 2015 TheIrrawaddy

Muse Zone to Boost Trade

Expansion moves ahead despite some locals’ complaints

By KYAW HSU MON/ MUSE, SHAN STATE

MUSE, Shan State —

The Muse Central Economic Zone project, spearheaded by the Shan State government and a local private venture, is moving forward in an effort to boost commerce along the Chinese border, despite land grievances from some local residents.

Located on the banks of the Shweli River in Muse, a major trading hub on the Sino-Myanmar border, the nearly 300-acre space allotted for the economic zone has been undergoing development since 2012. The project aims to establish six zones that will include residential areas, shop houses, hotels, shopping areas, a jade market and other businessrelated infrastructure, according to U Ngwe Soe, the project director of the New Star Light Company, which is implementing the project jointly with the Shan State government.

Muse is the largest trading point between Myanmar and China, and has long served as the conduit through which Myanmar exports and Chinese imports pass. Proponents of the economic zone say the plan will be a major boon for cross-border commerce.

The project covers about 295 acres, with investment by the Mandalay-based New Star Light expected at 94 billion kyats (US$94 million).

Developers are aiming to complete the project by 2017, after opening a Zone 1 phase in May. The 89-acre Zone 1 will include condominiums, shop houses, a jade bazaar, hotels and an Ocean supermarket.

“We plan to open Zone 1 this year. Eighty percent of construction is finished,” U Ngwe Soe said.

However, beginning in 2009, residents living on the allocated economic zone land have been forced to relocate in exchange for compensation from New Star Light. Like many development projects in Myanmar, the economic zone has provoked a backlash from some affected landholders who claim the compensation that they have been offered is inadequate.

Sai Ike, 58, has yet to be paid for his one acre of land, which he said the company “grabbed” from him.

“My parents had been cultivating paddy on their land since I was young. I was continuing to do that, but the company grabbed my land to develop

this area. Although I don’t have an official land ownership record issued by the government, I have some receipts showing that I paid [land] taxes to the government,” he said.

“My little land plot was grabbed by the company during the harvest season. There’s nothing left, everything has been destroyed by the company.”

New Star Light says it has compensated those relocated using a four category system based on how the land was used by its owners. Project director U Ngwe Soe said the company paid compensation in accordance with the four-tier system, as well as a sum deemed equivalent to the value of any crops cultivated by the compensated party.

“There are only 17 acres remaining that have yet to be compensated, the rest of the landowners have already received compensation,” U Ngwe Soe said.

“Except for these remaining landowners, the rest of the people agreed to take compensation for their lands.”

He defended the compensation scheme, saying the company was offering at minimum more than double

36 TheIrrawaddy January 2015 BUSINESS TRADE

A cyclist travels on a road within the Muse Central Economic Zone in northern Shan State.

PHOTO: KYAW HSU MON / THE IRRAWADDY

the government’s fixed price of 3 million kyat per acre, even for landholders who lack official land ownership records.

“The district and township authorities collaborated with us when dispensing compensation. Even if they don’t have ownership records, if they have receipts from dealings with the government for crops, we have paid them,” U Ngwe Soe said.

Some former landowners, however, claim that the compensation amounts, which they say they were effectively forced to take, were well below current market rates.

Ma Ei Phyu, a holdout who has not taken the compensation offered, spoke to The Irrawaddy from seven acres of land within the project area that is increasingly surrounded by development.

“They offered me 80 million kyats for seven acres of land. I have not taken it to date. I won’t give my land up for this project because the market land prices in this area are rising. It has reached 700 million to 1 billion [kyats] for one acre

on the market,” she said.

Ko Hlaing Han Pha, who was relocated, said his parents had owned seven acres of land in the project area that they were forced to give up when the project was first put forward in 2009.

“One of New Star Light’s subcontractors, Great Haokham Company’s MD [managing director] Sai Ohn Myint, told us to sell our lands, but we refused. Then, without our knowledge, he changed our land to his name in the government’s land records department,” he said.

“We’ve been offered 3 million kyats for each acre as compensation by him. He said if we don’t accept this amount,

we will not get more money and will lose our land. … Now, we just want our land back,” Ko Hlaing Han Pha said.

Development projects including the Thilawa and Dawei special economic zones (SEZs) and smaller-scale private ventures have faced similar difficulties as Myanmar’s government seeks to spur growth in the long-isolated economy.

The Muse Central Economic Zone was initiated by Vice President Sai Mauk Kham, who is a Muse native. During his second visit to Muse as vice president last October, he urged the project team to negotiate with former landowners to resolve the compensation issue.

For those holdouts still residing on the 17 acres of as yet uncompensated land, Ho Saung village may serve as an inspiration, after its inhabitants’ recalcitrance forced project developers to redraw their plans.

“We’ve extended our project beyond the original map because we can’t take seven acres, which are owned by one group [in Ho Saung],” U Ngwe Soe said.

37 January 2015 TheIrrawaddy ADVERTISEMENT

Condos, shop houses, a jade bazaar and hotels are planned

ADB to Loan $100m to Yoma

Myanmar Wired up to Yunnan

The Chinese state-owned telecommunications firm China Unicom has finished building a 1,500-kilometer (932-mile) long optical cable route through Myanmar.

The cable links China’s neighboring Yunnan Province with the Bay of Bengal coast, and improves communications between Mandalay, Yangon and Ruili on the Chinese side of the border.

“The optical cable line will improve south China’s telecommunication quality with Southeast Asia and nurture outsourcing industries like call centers,” said Myanmar Business Today, quoting China Unicom.

YANGON–The Asian Development Bank (ADB) will provide a loan of up to US$100 million to local conglomerate Yoma Strategic Holdings to improve infrastructure connectivity in Myanmar, according to Christopher Thieme, director of ADB’s private sector operations department.

The loan will be dispersed in two tranches, with the first used to build telecommunication towers, develop cold storage logistics and modernize vehicle fleet leasing. The second tranche will fund subprojects in transportation, distribution, logistics and other sectors.

“Investment in connectivity infrastructure is a key factor in creating better access to economic opportunities, reducing costs, promoting trade, and attracting private investment into diverse geographic areas and sectors,” said Thieme, at a loan signing ceremony in Yangon.

“It is a privilege to be chosen by ADB as a partner to work on improving Myanmar’s infrastructure,” said Serge Pun, executive chairman of Yoma.

“ADB’s loan will help support our goal of improving the country’s connectivity, which in turn will strengthen local markets, boost productivity, and create jobs,” he added.

The terms of the loan were not disclosed. Pun said the loan would be used to help fund ongoing projects.

“For example, building towers: we have agreed to build 1,280 towers around the country. About 800 towers are already built, so these loans will be used for ongoing projects,” Mr. Pun said.

An ADB statement said the projects would support sustainable economic growth in Myanmar, a global laggard in terms of connectivity metrics such as mobile penetration and road density.

The loan would help offset the fact that “private sector financing for much-needed infrastructure projects to boost connectivity remains a challenge due to an underdeveloped banking sector and capital market, and a lack of alternative funding sources,” the ADB said.

Yoma has property, agriculture, tourism, automotive, and retail businesses in Myanmar. Its market capitalization was $692 million, as of Dec. 2, 2014.–Kyaw Hsu Mon

“The project, designed to improve regional connectivity, cost about US$50 million.”–William Boot

Tower Share

YANGON—Keppel Land, a Singapore company that is part of one of the world’s biggest offshore oil services businesses, is paying over US$47 million for a share in a new office construction in Yangon.

Keppel will buy a 40 percent share in the City Square Office development in Pabedan Township, Myanmar Business Today has reported.

Other partners in the tower block project, which covers 2.4 hectares (six acres), are Myanmar businesses Shwe Taung Junction City Development and City Square Development. The overall cost of the development will be $118 million, Keppel reportedly said.

Singapore companies are among the biggest foreign investors in Myanmar, especially in real estate.

“Foreign investment goes mainly into the hotel and real estate business and Singapore and Hong Kong come first,” U Aung Naing Oo, the secretary of Myanmar Investment Commission, was quoted by Eleven Media as saying.–William Boot

38 TheIrrawaddy January 2015

Christopher Thieme, left, of the Asian Development Bank, at a loan signing ceremony with Serge Pun, executive chairman of Yoma Strategic Holdings, in Yangon.

BUSINESS SIGNPOSTS

PHOTO: STEVE TICKNER / THE IRRAWADDY

Speculators to be Targeted

YANGON — In a move targeting speculators, the Yangon Region government will require idle landholders in the region’s industrial zones to present a detailed business plan for how they will use the real estate or see it seized.

The regional Industrial Zones Management Committee, under Yangon’s Department of Human Settlement and Housing Development, announced that the owners of idle industrial plots were required to submit their business plans by Dec. 15.

“As we’ve discussed, the land owners who are not running businesses on their land will have to submit a detailed business plan. If not, or if the proposal seems like nonsense, those [lands] all will be taken back by the government,” said U Myat Thin Aung, chairman of the Hlaing Tharyar Industrial Zone’s management committee, whose members met with their division-level counterparts on the matter.

“[The government] has been trying to take action on these lands. If owners are not intending to run a business, they will have to give back the lands to the government and they will get a land price that is fixed by the government,” he said.

According to U Myat Thin Aung, there are more than 2,400 acres of idle land in Yangon’s industrial zones.

Though the Hlaing Tharyar Industrial Zone, Yangon’s biggest, is believed to be operating at full capacity, an excess of idle properties bedevils smaller industrial zones.

–Kyaw Hsu Mon

–Kyaw Hsu Mon

‘Hidden’ Investors Face Crackdown

YANGON — Foreign investors who seek to bypass laws by registering businesses under the names of Myanmar citizens are facing a “crackdown” by the Myanmar Investment Commission, a report said.

The problem is most pronounced in Myanmar’s rapidly growing garment industry, commission secretary U Aung Naing Oo said.