The Irrawaddy magazine has covered Myanmar, its neighbors and Southeast Asia since 1993.

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF: Aung Zaw

EDITOR (English Edition): Kyaw Zwa Moe

ASSOCIATE EDITOR: Sandy Barron

COPY DESK: Andrew D. Kaspar; David Kay; Feliz Solomon; Sean Gleeson

CONTRIBUTORS to this issue: Aung Zaw; Ye Ni; Nyein Nyein; Kyaw Hsu Mon; Lawi Weng; Kyaw Phyo Tha; Bertil Lintner; Yan Pai; Zarni Mann; San Yamin Aung; Yen Snaing; Simon Lewis; Claudia Sosa

PHOTOGRAPHERS: JPaing; Sai Zaw; Hein Htet; Teza Hlaing; Steve Tickner; Timo Jaworr

LAYOUT DESIGNER: Banjong Banriankit

SENIOR MANAGER : Win Thu (Regional Office)

MANAGER: Phyo Thu Htet (Yangon Bureau)

EMAIL: editors@irrawaddy.org

SALES&ADVERTISING: advertising@irrawaddy.org

SUBSCRIPTIONS: subscriptions@irrawaddy.org

PRINTER: Chotana Printing (Chiang Mai, Thailand)

PUBLISHER NAME : U Thaung Win

PUBLISHER LICENSE : 00706

YANGON BUREAU : Building No 170/175, Room No 806, MGW Tower, Bo Aung Kyaw Street (Middle Block), Botataung Township, Yangon, Myanmar. TEL: 01 388521, 01 389762

REGIONAL HEADQUARTERS MAILING ADDRESS: The Irrawaddy, P.O. Box 242, CMU Post Office, Chiang Mai 50200, Thailand.

54

58

12 | COVER Viewpoint: Beijing Goes Courting

14 | COVER China: Same Game, Different Tactics

Policy on Myanmar is being tweaked, not changed

20 | Politics: Mann with a Mission Union parliament speaker U Shwe Mann is growing more confident in his bid for the nation’s top job

22 |

Development: Doing Aid Better

Lahpai Seng Raw on how improvements are needed in the relationship between local and international aid partners

26 |

Development: A Step Toward Transparency

Billions of aid money is being spent in Myanmar, but where exactly is it going? A new website aims to shed some light

28 |

Education: Monk With a Vision

Sayadaw U Nayaka’s achievements on monastic schools

34 |

Politics: Peace Deal Set to Take Longer

Optimism over the immediate future of a draft nationwide ceasefire agreement appears to have been misplaced

37 |

Women: Forging the Future

Ma Nang Lai Kham of the Kanbawza group of companies

42 |

40 |

Transport: A Taxing Trip Reporter encounters nine checkpoints on 90-minute journey

Industry: Lawmakers Seek Answers on Stalled SEZ

Kyaukphyu plan is beset by delays

44 | Signposts: Insurers to Offer Health Coverage

46 |

REGIONAL

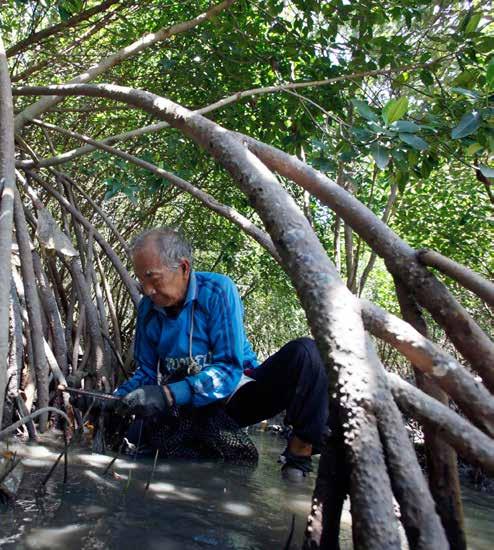

Environment: Sri Lanka’s Mangrove Protection Plan

When did you start EcoDev and what areas did you focus on at the time?

I started to engage in social welfare activities when I arrived back in Myanmar in 1994. At that time, civil society organizations had a limited role to play and we therefore had to cooperate with concerned UN agencies. We primarily helped locals claim the timber [from forests] which they had conserved from generation to generation, but that the government claimed.

After 2000, we engaged in work on the rule of law. For example, it is public knowledge that cutting down a tree is punishable by three years’ jail, although the Forestry Law does not carry that penalty. In some cases, villagers were imprisoned for cutting down a tree inside their own fence. We could help them get acquitted by appealing to the Supreme Court. Gradually, our focus has shifted from social development to the rule of law and environmental justice. We also took a lead role in protests against the Myitsone Dam. The 88 Generation Students group joined our efforts and it therefore became a massive protest movement.

Then again in 2012, we engaged in a program called “Ensuring Clean Air,” focused on handling the fumes emitted by coalfired power plants. We have been constantly engaged in campaigns against this. At present, we are working with concerned organizations

The Economically Progressive Ecosystem Development group (EcoDev) is a prominent local NGO campaigning and educating on resource rights and good environmental governance in Myanmar. Its director and co-founder, U Win Myo Thu, spoke with The Irrawaddy’s Kyaw Hsu Mon on combating deforestation and defending the rights and livelihoods of local communities in this resourcerich country.

to address environmental issues in urban Yangon. Mainly, we protect the rights of grassroots [communities]. We have labs where air and water quality can be examined and we present the results to concerned government departments and push for action.

From your experience, what environmental issues need to be addressed as a priority?

We view deforestation as the most pressing issue and the biggest threat to the environment. It is the major factor behind environmental deterioration and has many consequences. However, people tend to care more about other, more immediate problems. When we conducted a survey in over 60 townships in Kachin State and Sagaing and Tanintharyi regions, [respondents] mainly talked about water shortages and water pollution. That is very realistic because they use water every day. I had previously thought that only some areas were facing this problem of poor water quality, but then the survey suggested that it was a widespread problem and I was quite worried.

How strong is the public’s awareness of environmental issues at present?

Roughly speaking, they have [good] general knowledge about environmental conservation. They know that deforestation will lead to climate change and water scarcity. But they don’t know

about biodiversity because it is a difficult subject. It is fair to say that they have enough awareness to link causes and effects.

To what extent have forests depleted in Myanmar and what are the consequences?

According to the government’s forestry department and the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations forest cover is 46 percent [of the country’s land area]. They estimate that one percent of Myanmar’s forested area is lost on average annually. This rate is very high. The government takes both dense and sparse forests into account regarding the rate of deforestation. Recently, in cooperation with a foreign university, we studied the country’s deforestation using satellite images and found that almost one percent of very thick forests in Kachin State and Sagaing and Tanintharyi regions have been lost.

Deforestation of dense forests is particularly worrying. [The government] should issue an honest statement on current deforestation rates and the remaining forest coverage. It is terrifying that the deforestation rate is one percent. It can be argued that it is the highest rate in the world. Although the current percentage of forested area is not bad compared to other countries, we can’t be satisfied with this. If this amount decreased, it would be very difficult for grassroots [communities] to sustain their livelihoods.

People may receive help during times of disaster, but help is always limited. It is the environment that helps people sustain their livelihoods. How can they survive without this? If both social capital and natural resources are depleted, people will not be able to face environmental challenges. It is important that we conserve the environment now. According to a study, there are around 20 million people living within a fivemile radius of forests and around six million people living along rivers [in Myanmar]. These people will suffer if the water and forests they rely on are depleted.

human activities. Natural causes only account for around one percent of deforestation.

Do civil society organizations like EcoDev lobby the government on combatting the illegal timber trade? What recommendations has EcoDev offered on this issue?

After studying illegal logging, there are three main factors behind it: firstly, because of greed; secondly, because of livelihood; and thirdly, because of weak bureaucratic processes… Illegal logging at the border is either directly or indirectly linked with armed groups

a [small] bunch of wood are imprisoned while those who steal logs in trucks act with impunity. The Forestry Department has difficulty in enforcing the forestry law. In some cases, they are even killed. We civil society organizations want the government to adopt national level policies on illegal logging. It needs to develop plans and organize awareness training.

Another problem is awarding licenses for seized logs. It is called License 8. [The government] imposes a fine for smuggled logs seized and then gives the logs back to smugglers officially. So they log illegally before the eyes of the public and allow themselves to get arrested. They can then take logs out of the country legally after paying the fine. [The government] does not usually give out logging licenses. These issues need to be addressed.

There are natural causes like forest fires, but mainly it is

who do so for their survival. Even if they are arrested, they may not be punished legally because of the peace process. As villagers have said, there are cases in which those who steal

So far, only export regulations for the EU market have been discussed… I want the government to draw up plans to eliminate illegal logging. While a certain proportion of logs are exported to the EU market systematically, illegal logging is still rampant in the country. It is important that people are aware. Again, the government is only focusing on exports. We want the government to focus on local use. Poor people have to use wood for their houses as well as for agricultural implements. I would like wood to be available for the poor and for priority to be given to locals. But there may be different views.

An estimated one percent of Myanmar’s forested area is lost on average annually. That rate is very high.

‘‘We do meet sometimes. When we do, he would give us necessary guidance. To tell the truth, the armed forces became modern due to his endeavors. He also put Myanmar on the path to democracy.’’

—Myanmar Army Commander-inChief Snr.-Gen. Min Aung Hlaing speaking to Japanese newspaper Mainichi about former junta supremo Snr.-Gen. Than Shwe.

So near and yet so far

‘‘We will keep moving ahead against the construction of any projects, including Dagon City, near the Shwedagon.’’

–The Society to Protect the Shwedagon, a group of monks, speaking to The Irrawaddy.

‘‘We do worry that the reforms will turn out to be a total illusion, and we think that we need more concrete steps to ensure that the democratization process is what it was meant to be.’’

–Daw Aung San Suu Kyi speakingto

the Washington Post.

be elected lawmakers; and shifting the power to appoint state and regional chief ministers from the president to regional legislatures.

Local humanitarian organizations providing aid to displaced populations in Kachin and northern Shan states said they were facing a severe funding shortage from international donor groups this year.

A constitutional amendment bill submitted to Parliament on June 10 proposes granting greater political power to regional legislatures and would reduce the threshold of votes needed to make further changes to the charter.

The bill, which required the support of at least 20 percent of lawmakers in order to go before Parliament, was published in state-run newspapers on June 11.

Its proposals include reducing, from more than 75 percent to at least 70 percent, the number of votes needed to change most parts of the Constitution; requiring that presidential candidates

The bill also suggests amending the controversial provision that bars opposition leader Daw Aung San Suu Kyi from the presidency, though she would remain ineligible for the post despite the change. The proposed amendment to Article 59(f) would remove a ban for those whose children’s spouses are foreigners, but a prohibition on having given birth to children who are foreign nationals would remain in place.

U Tun Tun Hein of the National League for Democracy (NLD) told The Irrawaddy that the proposed changes were inadequate, with the NLD having suggested amendments to 168 clauses in total. —

Nyein NyeinFive humanitarian organizations within the nine that comprise the local relief network said they have only secured US$8 million, less than 45 percent of the estimated $19 million of funding needed for 2015.

The groups have called for donors to increase financial support in order to meet urgent humanitarian needs until IDPs can safely return to their homes.

The 2015 Humanitarian Response Plan by the United Nations Office for the Coordination of

Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) estimates that more than $71 million is needed to assist 120,000 people in need of humanitarian aid in Kachin and northern Shan States.

“Humanitarian donors globally are currently stretched and we are very concerned that the humanitarian response in Myanmar will suffer from underfunding,” Pierre Péron, spokesperson for OCHA Myanmar, told The Irrawaddy.

In Kachin and northern Shan states, Mr. Péron said, “Temporary shelters, sanitation and other facilities require renovation or replacement. Some relief items distributed early on need to be replaced.”

June 9 marked the fourth anniversary of the restart of fighting between the Kachin Independence Army and the Myanmar Army after the breakdown of a 17year ceasefire. Over 100,000 people remain displaced by the conflict. —Yen Snaing

Myanmar’s Union Election Commission (UEC) responded to claims by the National League for Democracy (NLD) that up to 80 percent of eligible voter lists compiled by the electoral body were inaccurate, with the commission chairman acknowledging numerous errors but insisting the necessary measures were in place to resolve the issue.

The NLD said in an open letter made public in June that its own

“voter list reviewing committee” had determined that between 30 percent and 80 percent of the listings were inaccurate, after scrutinizing the rosters in the 32 townships in Naypyitaw and Yangon that had been made public at the time. The errors ranged from incorrect dates of birth to the erroneous listing of people who lack identity documents, the letter said.

The UEC chairman, however, said the NLD was “exaggerating a bit.”

“From the beginning, we knew the preliminary lists would include many errors,” U Tin Aye told reporters.

“Since we were compiling the voter lists based on two outdated lists—ward-level population lists and household registration lists—the voter lists will contain many errors and thus we urged voters to check the list to correct the errors in the preliminary lists.” —San Yamin Aung

Myanmar rejected assertions that Indian armed forces entered the country in pursuit of separatists last month, saying foreign fighters would never be allowed to use Myanmar territory to stage attacks.

India’s junior minister for information and broadcasting, Rajyavardhan Singh Rathore, said India’s army attacked rebels just over the border with Myanmar on June 9, underlining New Delhi’s resolve to fight terrorism beyond the country’s borders.

However a statement from the President’s Office in Myanmar, citing information from troops in the northwest border region, said fighting had only broken out on the Indian side.

The strike was carried out in response to the killing of 20 Indian soldiers in an ambush in Manipur in

early June.

The India army said in a statement that it received intelligence that rebel forces were plotting more attacks.

The statement from the President’s Office denied that any outside forces were using Myanmar as a staging ground for attacks.

“Myanmar will never accept any foreign rebels using its territory and border area as a base,” it said. “Myanmar is willing to negotiate and cooperate with the Indian government to handle the problem.”

The statement said that India’s

ambassador to Myanmar had met with the deputy minister of foreign affairs on June 9 to “explain the situation,” but gave no further details. —Reuters

There was color, noise and passion on the streets of Yangon and throughout Myanmar in June as football fans came out in force to watch the SEA Games under-23 football final between Myanmar and Thailand.

Starting out as tournament underdogs, the Myanmar team capped a stellar tournament with its first finals appearance since 2007.

In Yangon's teashops, bars and other public spaces such as Mahabandoola Park where these fans (pictured) gathered on June 15 to cheer on their team in the final, the football fever was infectious.

The heavily favored Thais ultimately wore down their spirited opponents with a 3-0 victory, leaving local fans with little choice but to look ahead with hope for the team’s next shot at the title in 2017.

PHOTO: REUTERS PHOTO: REUTERS

The country’s most revered Buddhist shrine is currently making headlines as civic and religious campaigners raise concerns that the pagoda’s environs would be undermined by nearby development projects.

By AUNG ZAW

By AUNG ZAW

Beijing’s recent courting of Daw Aung San Suu Kyi was deliberate and wellcalculated. At a time when the political maneuvering in Myanmar is heating up ahead of elections later this year, “The Lady” flew to Beijing in June to meet Chinese president Xi Jinping in the Great Hall of the People. Should her visit surprise anyone?

In the minds of Chinese leaders, Daw Aung San Suu Kyi’s invitation letter was effectively penned after she made visits to the White House and other Western capitals in 2012. Beijing could not simply sit back and watch the influential opposition leader be subsumed exclusively into the Western orbit.

The government invited senior members of the National League for Democracy (NLD) to China for discussions over the last two years, laying the groundwork for last month’s high-level meeting.

On Daw Aung San Suu Kyi’s part, she sent a signal of appeasement to China in 2013 when she led a commission that green-lighted the controversial Letpadaung copper mine project despite significant local opposition.

“We have to get along with the neighboring country, whether we like

it or not,” she said amid the wave of ensuing criticism.

Once dubbed the “darling of the West,” Daw Aung San Suu Kyi recently accused the US and others of complacency on Myanmar policy. “The United States and the West in general are too optimistic and a bit of healthy skepticism would help everybody a great deal,” she said.

While the US and its allies have seemingly become more tolerant of the Myanmar government, the relationship between Naypyitaw and Beijing has soured since the 2011 suspension of the US$3.6 billion China-backed Myitsone hydropower project in northern Kachin State. Needless to say, China was not happy with the decision and has sought to have the project revived.

Tensions have also recently arisen over conflict in the Kokang Special Region along the Sino-Myanmar border which has spilled over into Yunnan, leaving several Chinese villagers dead or injured. China’s People’s Liberation Army carried out a live-fire drill along the border last month which was widely viewed as a warning to the Myanmar government.

Interestingly, the day after Daw Aung San Suu Kyi’s plane landed in Beijing, the Kokang group that has been battling the Myanmar Army

since February declared a unilateral ceasefire. Yang Houlan, China’s outgoing ambassador to Myanmar, told Snr.-Gen. Min Aung Hlaing that the Chinese government had contacted Kokang leaders to stop military operations and solve problems through political means. Was the timing a coincidence?

Despite friction, China remains Myanmar’s largest investor, accounting for about US$14.6 billion in cumulative investments—nearly a third of all FDI. The country has invested in just about every sector of Myanmar’s budding economy, with a particularly strong foothold in hydropower, gas and oil and with grand plans, such as a railway line linking Yunnan and Rakhine State, still in the offing.

China views Myanmar as crucial to securing strategic access to the Indian

Ocean. But seeing the rise of Western influence in the country once dubbed a Chinese “client state,” has given Beijing pause.

What if Western companies ramp up their investment in Myanmar, where resentment toward Chinese firms runs deep? What if US-Myanmar relations continue to improve? Chinese leaders realize the country could lose the advantage it once had when Myanmar was internationally ostracized and cut off from Western investment.

Beijing knew that inviting Daw Aung San Suu Kyi to China, with its history of support for Myanmar’s previous military junta, was complicated, but could also win the hearts and minds of many Myanmar citizens. In reaching out to the NLD leader, China was bypassing the Myanmar generals, whom it senses harbor a degree of antiChinese sentiment.

The visit also sent a signal to the West that China remains a key player

in Myanmar affairs, even as the US, the EU and others step up their engagement with the once pariah nation.

In an English-language editorial, the state-run Xinhua News Agency said Daw Aung San Suu Kyi’s visit was a sign that the Communist Party not only communicates with parties with “the same ideology, but also those with a different political vision.”

“China welcomes anyone with friendly intentions and it bears no grudge for past unpleasantness,” the editorial said.

In fact, China has been courting four potential post-election leaders in Myanmar. President Xi Jinping has separately hosted President U Thein Sein, Myanmar Army chief Snr.-Gen. Min Aung Hlaing and Union Parliament Speaker U Shwe Mann in Beijing.

Many are curious to know what the Chinese president and the Myanmar opposition leader spoke about during

their meeting in Beijing. Daw Aung San Suu Kyi has been tightlipped about the visit, telling the Washington Post only that it was “a good discussion” and that “We all understand neighbors have to live in peace and harmony.”

Many activists called on the NLD leader to speak up for imprisoned Chinese dissident, writer and fellow Nobel Peace prize winner Liu Xiaobo during her meetings in China. Sadly, this was always wishful thinking.

Like other seasoned politicians around the world, Daw Aung San Suu Kyi is guided by pragmatism; she is no longer an icon of democracy and human rights. China knows this and hence felt comfortable inviting her to Beijing.

Daw Aung San Suu Kyi’s shrewd political pragmatism may come from her father, Gen. Aung San, who led an alliance with the Japanese in order to drive out the British colonialists. He later switched sides, back to the British, in order to dislodge the Japanese. In the view of many Myanmar, Gen. Aung San is respected as a leader willing to cut a deal with either friends or enemies to achieve his goal: the nation’s independence.

Beijing may view Daw Aung San Suu Kyi as the best chance of securing its stake in the country. She is bound to be an influential political player after the elections and, if properly courted, might be willing to endorse Chinese investments and calm rising anti-China sentiment among the public.

Whether supporting China-backed development projects and large-scale investment is in the best interests of the nation is, however, an open question.

This is a new ball game, where China has decided to make a move with one eye on the November poll. The invitation to Myanmar’s opposition leader may hint that China has already placed a first bet on where political influence will lie in Myanmar’s postelection landscape.

Although it would publically state the exact opposite, for Beijing, the coming election in its troubled neighbor is much more than an “internal affair.”

China’s President Xi Jinping shakes hands with National League for Democracy leader Daw Aung San Suu Kyi during their meeting at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing, China, on June 11. By BERTIL LINTNER

By BERTIL LINTNER

Former junta leader Snr.Gen. Than Shwe meets China’s then Communist Party Chief Hu Jintao in Beijing in January 2013.

Former junta leader Snr.Gen. Than Shwe meets China’s then Communist Party Chief Hu Jintao in Beijing in January 2013.

Much has been said and written about Daw Aung San Suu Kyi’s recent visit to China, and some commentators have even suggested that it may signal a shift in Beijing’s policy towards Myanmar— away from the government and towards a more favorable view of the prodemocracy opposition.

It would be more accurate, however, to say that China’s long-term strategic and geopolitical interests in Myanmar remain the same while its tactics vary, depending on the political climate in its troubled neighbor.

This became clear to me when, in June 2002, I had lunch with a senior adviser to Hu Jintao, the leader who later that year became Chinese president. It was a private meeting, so it would be unethical to mention his name, but I can relate the gist of our conversation without violating any trust or confidence.

I wanted to hear his opinion on my theory about Beijing’s interests in Myanmar: that China’s landlocked provinces needed an outlet for exports through Myanmar territory in order for these regions to catch up with the then-rapidly developing coastal areas.

Rail and road links to China’s own ports were too long, and those ports would in any case be clogged

with export items produced in the coastal provinces. Disparity in the development between the coast and the vast hinterland could threaten China’s national security and internal stability.

This was not a wild guess on my part. In fact, China made its intentions clear as early as 1985. In an article published in the official newsmagazine “Beijing Review” on September 2 of that year, Pan Qi, a former vice minister of communications, outlined the possibilities of finding such an outlet from Yunnan and Sichuan through Myanmar down to the Indian Ocean.

The article mentioned the Myanmar railheads of Myitkyina and Lashio in the north and northeast, and the Ayeyarwaddy River, which flows through almost the entire length of the country, as possible conduits for Chinese exports. Therefore, I surmised, China was keen to maintain the status quo in Myanmar—friendly relations with the military junta.

To my surprise, the Chinese official answered without hesitation: “Absolutely. Those are our interests in Myanmar, we do not want to see any regime change. And Myanmar is not only a potential outlet for us but also an inlet.” A strange choice of words and I asked, “an inlet for what?”

His reply startled me: “We are no longer self-sufficient in oil… Most of our imported oil comes from the Middle East, and in case of a future conflict with the United States, they can block the Straits of Malacca. Therefore, we are going to build another pipeline, through Myanmar to Yunnan.”

He didn’t specify what kind of potential conflict he was envisioning with the Americans, but it could have been an invasion of Taiwan. The United States is treaty-bound to defend Taiwan—also known as the Republic of China—but not even the most hardline hawks in the Pentagon would, in such an eventuality, consider lobbing missiles into Shanghai or Beijing.

But blocking the Straits of Malacca to cut vital oil supplies to China would be an option. And he was right about

Former Communist Party of Burma chairman Thakin Ba Thein Tin PHOTO: HSENG NOUNG LINTNERthe pipeline. In November 2008, China and Myanmar agreed to build a US$1.5 billion oil pipeline and a $1.04 billion natural gas pipeline along exactly the route this official had mentioned to me several years before.

Our conversation took place shortly after East Timor had become independent, a prospect that few could have predicted 10 years before. In the spirit of this unexpected outcome, I asked: “What would you do if Daw Aung San Suu Kyi became the president of Myanmar?” (This, of course, was before the implementation of the 2008 constitution, which bars her from assuming the presidency).

He gave me another amazing reply: “But we admire Daw Aung San Suu Kyi! We think she is a fantastic woman!” The conclusion was obvious: Beijing would

not want to see any drastic changes in Myanmar, but if they occurred, the Chinese would adjust accordingly to protect their long-term interests. And that is exactly what is happening today.

The Chinese do not want to put all their eggs in one basket. The government in Myanmar may or may not survive in its present shape and form, but the Chinese are prepared for all eventualities. This is not by any stretch of the imagination a policy shift.

With its strategic location between South and Southeast Asia, and between the Chinese hinterland and the Bay of Bengal, Myanmar has long been important to China. Forget about empty Chinese talk about “non-interference” and “respect for Myanmar’s sovereignty.” That is pure nonsense.

China has always interfered in Myanmar’s internal affairs and most probably always will. In the past it was to export world revolution; today it is trade and commerce. With a different emphasis, “the Myanmar corridor” remains of utmost importance to China’s policy makers.

During the decade 1968-78, the Chinese poured more aid into the Communist Party of Burma (CPB) than into any other communist movement outside Indochina. A new 20,000 square kilometre base area was established along the Chinese border in Myanmar’s northeast.

Unlike the old CPB units, then mainly in the Bago Yoma mountains north of Yangon, these new troops were equipped with modern Chinese assault rifles, machine-guns, anti-aircraft guns and mortars. Radio equipment, jeeps, trucks, petrol and even rice and other foodstuffs, cooking oil and kitchen utensils were sent across the frontier.

The Chinese also built two small hydroelectric power stations inside the CPB’s new northeast base. A clandestine radio station, “The People’s Voice of Burma,” began transmitting from the Yunnan side of the border in April 1971. It was later moved to the CPB’s headquarters at Panghsang inside Myanmar—now also the headquarters

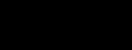

A CPB meeting at Pangshang in 1987, under portraits of old Communist icons.China has always interfered in Myanmar’s internal affairs and probably always will.

of its successor, the United Wa State Army (UWSA).

Among the items China sent to the CPB was a truckload of newly printed, detailed contour maps of Myanmar. The plan was to push down from the northeast to the Bago Yoma mountain range, and eventually capture Yangon. That failed, however, as government forces launched a major offensive against the CPB in the Bago Yoma in 1975.

After the loss of other central base areas in the mid-1970s, the CPB became isolated in the northeast, far away from the Myanmar heartland, and nominated a new chairman, Thakin Ba Thein Tin, who had spent years in exile in China in the 1950s and 1960s. The area under its control was almost exclusively populated by various ethnic minorities such as the Wa, Kokang Chinese, Kachin, Akha and Lahu. Only the top leadership and most of the political commissars came from central Myanmar.

Most Western scholars have suggested that China’s post-1968 support for the CPB was prompted by anti-Chinese riots in Yangon in June 1967. But it was not a knee-jerk reaction to those events. Preparations for the push into Myanmar began shortly after the military takeover in 1962.

China had enjoyed cordial relations with the government that was overthrown, led by U Nu, and had little confidence in the new regime led by Gen. Ne Win. China also had grander plans for the entire region. It was going to export revolution to Southeast Asia, and the CPB was a vital link in that strategy. The CPB was, in turn, expected to link up with communist parties in Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia and as far away as Australia.

The 1967 anti-Chinese riots were merely an excuse for implementing a plan that had been drawn up years before by China’s intelligence chief, Kang Sheng, a master strategist who worked closely with Thakin Ba Thein Tin and other Southeast Asian communist leaders as well as Ted Hill, the chairman of a tiny pro-Chinese communist party in Australia.

In March and April 1989, the hilltribe rank-and-file of the CPB’s

army, tired of fighting for an ideology of which they understood very little, rose in mutiny against the party’s ageing Bamar leadership. Thakin Ba Thein Tin and the other party veterans fled across the border to China, where they were allowed to settle and retire—and eventually died.

After the 1989 mutiny, the CPB broke up into four different armies, all based along ethnic lines. Of these, the UWSA was by far the most numerous and powerful. The 1989 mutiny actually suited China’s interests, and there are strong suggestions that China’s clandestine services actually encouraged the Wa and others to rise up against their Bamar bosses.

Following the death of Mao Zedong in 1976 and Deng Xiaoping’s return to the political fold, China changed its policy towards the region. Now, the emphasis was on trade and economic expansion, not Maoist-style world revolution.

The CPB’s leaders were aware of China’s new policies and in internal party documents dated before the mutiny and seen by this contributor, Thakin Ba Thein Tin

accused the Chinese of having become “revisionists.”

In a desperate last attempt to save the party, Thakin Ba Thein Tin had in early 1989 decided to send a leading cadre to Laos, a Soviet ally, to contact Moscow. That was pure lunacy since the Soviet Union was then ruled by Mikhail Gorbachev, a reformer who would have no interest whatsoever in lending support to the CPB. In any event, the mutiny broke out before the CPB emissary could reach Laos, so even he had to escape to China.

But Beijing was not going to give up the secure position it had cultivated inside Myanmar since the late 1960s. In May 1989, the UWSA entered into a ceasefire agreement with the Myanmar government, which, on the one hand, suited China’s new commercial interests. But it was also imperative to strengthen the UWSA.

As China sees it, it cannot afford to “lose” Myanmar to the West. A strong UWSA provides China with a strategic advantage and a bargaining chip.

After all, the Chinese had had a longstanding relationship with most of the leaders of the UWSA, dating back to their CPB days.

Thus, the UWSA was able to purchase vast quantities of weapons from China and, according to the April 26, 2013 issue of the prestigious military affairs journal “Jane’s Defence Weekly,” even armed transport helicopters:

“The acquisition of helicopters marks the latest step in a significant upgrade for the UWSA, which has emerged as the largest and bestequipped non-state military force in Asia and, arguably, the world,” the journal wrote.

In the second half of 2012, the UWSA had acquired armored vehicles for the first time. These included both Chinese PTL-02 6x6 wheeled “tank destroyers” and an armored combat

vehicle that IHS Jane’s identified as the Chinese 4x4 ZFB-05. Furthermore, the UWSA has obtained from China huge quantities of small-arms and ammunition—and around 100 HN-5 series man-portable air defense systems (MANPADS), a Chinese version of the first-generation Russian Strela-2 (SA-7 “Grail”) system.

The UWSA today is better armed than the CPB ever was. It can field at least 20,000 well-equipped troops apart from thousands of village militiamen and other supportive forces. Moreover, the top leaders of the UWSA are usually accompanied by Chinese intelligence officers who provide advice and guidance.

So what is China up to? Why this arming of a non-state military force at the same time as Beijing has had cordial relations with the Myanmar government since it abandoned its

policy of supporting communist insurrections in the region?

It is no doubt a way of putting pressure on Myanmar at a time when its relations with the United States are improving. As China sees it, it cannot afford to “lose” Myanmar to the West. A strong UWSA provides China with a strategic advantage and is also a bargaining chip in negotiations with Naypyitaw.

When President’s Office Minister U Aung Min visited Monywa in November 2012 to meet local people protesting a controversial Chinese-backed copper mining project, he openly admitted: “We are afraid of China… we don’t dare to have a row with [them]. If they feel annoyed with the shutdown of their projects and resume their support to the communists, the economy in border areas would backslide.”

By “the communists” he clearly meant the UWSA and its allies, among them the Myanmar National Democratic Army (MNDAA) in Kokang, another former CPB force, which resorted to armed struggle in February this year. China, predictably, has denied any involvement in that conflict, but the fact remains that most of the MNDAA’s weaponry and vast quantities of ammunition have been supplied by the UWSA.

According to one well-placed source, China is indirectly “teaching the Myanmar government a lesson in Kokang: move too much to the West, and this can happen.” At the same time, China is playing another “softer” card by being actively involved in so-called “peace talks” between the Myanmar government and the country’s multitude of ethnic rebel armies.

Whether China wants to export revolution or expand and protect commercial interests, it apparently feels that it needs to have a solid foothold inside Myanmar. There is no better and more loyal ally in this regard than the UWSA and its affiliates.

Inviting Daw Aung San Suu Kyi to China essentially serves the same purpose: to put pressure on the government in Naypyitaw and keep its options open for the future—all with the aim of securing the vital “Myanmar corridor.”

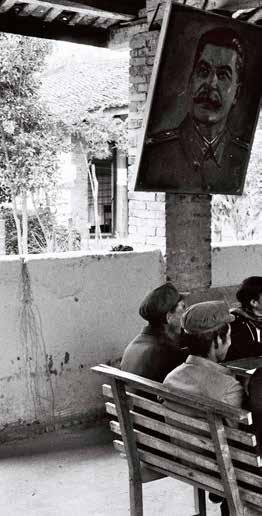

With Myanmar’s national elections less than six months away, the million dollar question is: who will be the next leader of the country?

At the fourth central committee meeting of the Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP) held in Naypyitaw in May, it was announced that Union Parliament speaker U Shwe Mann would remain at the helm as chairman, leading the party into the elections slated for November.

It seems that U Shwe Mann, who has openly declared his interest in the presidency, has grown in confidence after visits to the US and China in April. What strategies will the third most powerful general of the former regime employ in his bid for the presidency? We will have to wait and see.

The political intentions of incumbent president U Thein Sein remain a mystery. Although he has not stated whether he would seek a second term, in his monthly radio address in May, in reference to the peace process, the president said his administration intended to leave a strong foundation for the next government to build upon.

Does this imply he won’t run for reelection? If so, it could signal an end to the internal tug of war between the president and the parliamentary speaker, paving the way for the latter to run for the country’s top job.

But the road to the presidency is far from straightforward for U Shwe Mann, with the majority of political pundits predicting that the USDP is heading for

a humiliating defeat if the forthcoming elections are free and fair.

The forerunner of the USDP, the Union Solidarity and Development Association (USDA), was founded in 1993 on the instructions of former Snr.-Gen. Than Shwe. The USDA engaged in activities suppressing the pro-democracy movement of which Daw Aung San Suu Kyi was the most recognizable face since 1988.

In 1997, she branded USDA members thugs. Six years later, her motorcade was attacked by a pro-junta armed group, including members of the USDA and hired heavies from Swan Arshin, at Depayin in Sagaing Region.

The reputation of the USDA went from bad to worse when its members were again implicated in the regime’s violent crackdown on Saffron Revolution protesters in 2007. The organization then transformed itself into a political party—the USDP—in 2010 to contest that year’s general elections.

After the country’s main opposition party, the National League for Democracy (NLD), boycotted the polls, the USDP won in a landslide—a result discredited by reports of widespread electoral irregularities.

Despite some important reforms, the ruling USDP and the quasi-civilian executive have protected the common interests of the army and their cronies while students, activists, farmers and workers continue to be imprisoned

simply for peacefully expressing dissent.

But even with a tainted image, the USDP does retain some electoral advantages. The party is financially strong and its network stretches across the country. It is familiar with the bureaucracy and can lay claim to a degree of “experience” in governance, in contrast to the NLD.

However, whether this translates to a U Shwe Mann-presidency depends greatly on opposition leader Daw Aung San Suu Kyi.

U Shwe Mann maintained a healthy political relationship with Daw Aung San Suu Kyi throughout 2014 and has been smoothing the way for an unlikely coalition between the two major parties. During his recent visit to the US, the parliamentary speaker said he was willing to cooperate with the NLD leader.

Under Article 59(f) of the 2008 Constitution, Daw Aung San Suu Kyi is barred from the presidency, even if the

Union

marking the anniversary of Martyrs’ Day at the Martyrs’ Mausoleum in Yangon last year.

persuade the NLD or many ethnic political parties in regions subject to decades of human rights abuses at the hands of the Myanmar Army.

Could he win the backing of the USDP?

The once-accepted unity between the USDP and the military is on the wane. The USDP under U Shwe Mann appears to be edging away from the army and is transforming itself into a more independent political party. It no longer wishes to be identified as a party stacked with generals-turned-MPs.

“We won’t just field army men,” said USDP General Secretary U Thein Swe at a press conference on May 31. “We’ll field those who have the potential for victory in [constituencies] where we can win. It is up to us whether or not to accept [candidates], no matter how many the army sends us.”

NLD wins the elections. On this highly contentious issue, U Shwe Mann has sent mixed messages.

In 2014, he said the charter should be amended to allow the NLD leader to run for the country’s highest office. However, he has since spoken of the impossibility of amending the constitution before the election.

For her part, Daw Aung San Suu Kyi refused to rule out boycotting the elections in an apparent attempt to pressure the government on constitutional change. However, this would seem an unlikely move given the opposition leader would still wield significant influence in the legislative chamber if the NLD claimed an expected electoral majority.

If so, Daw Aung San Suu Kyi may be willing to countenance a U Shwe Mann presidency.

While detractors may view her support of a former general as disloyal to supporters of the NLD and the broader democracy movement, others could see such a compromise as paving the way for constitutional change at a later date, including Article 59(f).

Myanmar Army chief, Snr.-Gen. Min Aung Hlaing, has urged for loyalty to the 2008 Constitution in its current form. This is a solid indication that the military will not easily relinquish its formidable political role.

The Defense, Home Affairs and Border Affairs ministers are all army appointees and 25 percent of parliamentary seats are reserved for the military.

Snr.-Gen. Min Aung Hlaing, who is said to be a confidante of Snr.-Gen. Than Shwe, is due to retire soon and rumors have swirled that he may throw his hat in the ring for the country’s presidency.

If so, he would likely enjoy the backing of those military representatives constitutionally enshrined in the new post-elections parliament. However, these votes alone would not be enough. He would also need the support of other lawmakers, including from ethnic political parties.

Before the election, the commanderin-chief may need to form a political alliance. It is doubtful that he could

While the USDP may profess to keep its distance from the military, its leadership, ex-generals themselves, understands the army’s concerns and will be careful to manage any tensions.

On a recent visit to meet wounded Myanmar Army soldiers in a military hospital in Shan State’s Lashio, U Shwe Mann threw his support behind the army, describing their fight against Kokang rebels as “a fight for justice.”

U Shwe Mann, who was the former chief of staff of the army, navy and air force, seems convinced he can keep the military onside while pushing ahead with reforms in cooperation with the NLD, ethnic and other lawmakers through the coming elections.

Critics point out that a U Shwe Mann presidency would be a victory for the status quo, where a handful of cronies and military associates enjoy government protection and rewards.

However he is viewed, with Daw Aung San Suu Kyi currently ineligible for the country’s presidency, U Shwe Mann may have one hand on the top job.

Parliament Speaker U Shwe Mann (center) with Vice-President Sai Mauk Kham (left) and Upper House Speaker U Khin Aung Myint at an eventAround the world, the way foreign aid works is coming under wider scrutiny. Criticisms of an increasingly privatized international aid “industry” include claims that many of its approaches are too top-down, inflexible and ineffective.

Reformers also question the relationships between large international aid organizations and their local “partners.” Who decides how aid money is spent? With whom does the power lie? Often, the big decisions about local aid are not made by locals.

Magsaysay award-winner Lahpai Seng Raw, one of Myanmar’s leading civil society voices, echoes growing international calls to “do aid differently,” in an email conversation with reporter Nyein Nyein.

Myanmar has received a large influx of aid since 2011. What is your view of the current aid system?

Years of mismanagement by successive authoritarian governments and unabated armed conflicts have paralyzed it.

There is no shortcut to reverse this. But the fact remains: getting civilians to make their own choices, and getting civilian voices back, are the deciding factors in bringing about lasting peace in our country.

The way we—local NGOs, community-based organizations and international donors—respond to community needs will determine whether or not we can help regenerate them.

Sadly, since 2011, there is less and less room for local agendas to determine eventual programming.

Too often local NGOs and community-based organizations are approached by big donors to implement their own pre-formulated programs according to their own agendas and foreign policies. These practices effectively exclude the local organization and undercut local initiatives.

This means a big gap arises between donor requirements and

real development needs. For us, development needs are about people’s lives, and social processes—they are not about a project “market” and its related administrative bureaucracy.

It is ironic that now that the country has become more open and more money is flowing in, civil society is facing more challenges.

I have seen that international agencies have become either very project-focused or sector-oriented, and that talk of strengthening civil society is meaningless.

Why do international agencies support Myanmar civil society? Is it because they need to disburse lots of money and are not allowed to give it to the government? Is it because community organizations have access to places that the UN and INGOs do not?

These reasons for working with community organizations are not helpful. That’s because as soon as circumstances change, their support will revert to others—the government, the UN, international NGOs, etc.

This is already happening right now.

I want to see all our donors continue to support civil society for the right reason. That reason is about recognizing that civil society is a critical

actor with a critical role in Myanmar’s future.

Reinforcing and building a strong civil society should be the aim, not using civil society as a transitional instrument to deliver aid.

Also, it still happens that calls go out [for local and international NGOs to apply for] proposals on projects that are not fully funded. In reality, this gives

an advantage to international NGOs to be the legal holders of those projects.

The worst part is that funds are given to international NGOs and UN agencies that we are then to partner with.

I strongly believe this is too topdown. Local applicants must be given preference, and we must have a choice about with whom we want to partner.

“It is time for international agencies to acknowledge the local NGOs and work hand in hand with them on joint strategies and in mutual recognition.”PHOTO: STEVE TICKNER / THE IRRAWADDY

We definitely need and want to continue working with our international partners. Frankly, as a person from an ethnic minority group, I never thought that we would have to fight for equality with our international donors, when, after all, they are the champions of democracy.

We must find a way to resolve these problems.

Do you have suggestions for improvement in the approaches taken by international organizations?

We would like to urge them to be considerate in the strategic design of their funding mechanisms; to design systems and formats in local languages; and to avoid complex blueprints and mechanisms that preclude supporting the communities’ own efforts.

It is also essential to recognize that local NGOs need core funds for direct or indirect support of their activities. For example, maintaining and enhancing professional standards, including good financial control and accountability, good prioritization of aid, and with the right quality and independence, to name a few aspects of local organizations’ work.

We need to have enough funds to retain our staff… or otherwise, however committed our staff are, they leave for better conditions.

Without core funds, we also lose continuity for strategic planning after a project period ends.

It’s also important to realize that before any proposal is produced, we carry out assessments and discussions with all levels of stakeholders, from the grassroots to policymakers, leading to several planning workshops.

What I am trying to say is that this involves sowing social commitment. We are obliged then to meet the expectations of all involved. So for example, when the European Commission puts out calls [for applications for large aid projects] it must recognize the above sequence of inputs and communication.

Donor organizations don’t expect to survive themselves

without core funding, yet local organizations are expected to do so. Are there any signs the donors are starting to see this problem from the local perspective?

I am afraid it is getting worse as more big donors come in and set up more offices across the nation.

Internal organizational changes in some of our international partners also result in changes in how they work

with us. Sometimes these reasons cause them to adjust their costs at the local partners’ expense.

The challenges of not having adequate, reasonable core funding is no small matter for local organizations. Revitalizing communities will be more difficult if the local NGOs themselves have become paralyzed.

There seems to be a reluctance among international agencies

“Too often big donors impose their own agendas, undercutting local initiatives.”

to accept local leadership in development programs. What do you think are the reasons for this?

Some international agencies are very close to the UN and donors’ agendas. Others are closer to the reality and are supporting local actors. It is time for the international agencies to acknowledge the local NGOs and work hand in hand with them on

joint strategies, and with mutual recognition.

You made a statement in a number of places last year that “armies can sign ceasefires, but only the people can create a peace.” Do you see signs that this is better understood now?

Yes, I have been emphasising repeatedly the need to recognize the difference between ceasefires and peace.

“Peace” is a social state and cannot be developed by military men, and cannot be developed without the leadership and will of the people—they must build it and live it.

That is why I talk about a unified front. All ethnic nationals within the Union must come together to resolve the root causes that led to the present conflict. We need to break the cycle of armed conflict, militarization, human rights violations, displacement, resettlement, poverty, illegal migration, low wages, human trafficking, illicit drugs and corruption—the list could go on— or it will never be broken and continue to drag down the next government, which will be unable to stop exporting its own difficulties and crises to the whole region.

Encouragingly, there are processes taking place now and the civil society network is better than at any time in our country’s history.

The current ceasefire process is looking uncertain. What are your views on this?

The turmoil that Myanmar has witnessed during the last four years could be doubled or even tripled in 2015 if efforts towards peace and reform do not succeed. I am, therefore, gravely

concerned about the recent situation and believe in building a robust civil society as the most effective response to the challenges that we are facing.

Whatever happens, even if national institutions in government and politics become weakened, with a strong civil society we can surely overcome this and rebuild. I have been saying all along that, in the Myanmar context, strengthening civil society and building peace are interdependent.

All efforts should be made to ensure that the future to come will be built from today onwards: by providing quality education, dignified sustainable livelihoods, and respect and promotion of the rich cultures that define our identities across the different ethnic nationals that compose the mosaic of the Union of Myanmar.

What is the main focus of your work these days?

The central purpose of my life will always be to support people’s processes to build a strong and sustainable civil society, in peace, and with full entitlement to their rights; that is true justice.

I have been advocating aid agencies’ need to continually assess their capacity to follow their mandate and to reflect on the current humanitarian system in Myanmar.

I have used the US$50,000 prize money that came with the 2013 Ramon Magsaysay award as a seed fund to launch a new initiative that will ensure that the Ayeyarwaddy River continues to flow far into the future, and that just as the mighty river connects all diverse ethnic nationals, it will inspire us to come together in unity in striving for the peace and prosperity of our nation.

“It is essential to recognize that local organizations need core funds.”Local aid: An HIV positive man puts on thanaka paste in front of a mirror at an HIV/AIDS hospice, founded by a member of the National League for Democracy party, in the suburbs of Yangon in December 2012. PHOTO: REUTERS

Since 2011, Myanmar has become the recipient of a huge amount of new development aid. That means large amounts of money are now committed to health, education, humanitarian aid, infrastructure, services and many other sectors of society in which improvements are desperately needed. So how can the public find out more about what is being done, and where?

Myanmar signed up last year to the International Aid Transparency Initiative (IATI), a voluntary aid transparency measure, and now a new website has become accessible online that gives preliminary information on aid commitments in the country since 2011.

Around 80 percent of overseas development aid has been recorded on the site which is under the auspices of the Ministry of National Planning and Economic Development, according to the European Union Delegation to Myanmar, which funds the initiative.

According to the mohinga.info website, which is still in the beta stage, $US5.31 billion in aid has been committed by development partners in Myanmar within the date range of January 2011 to December 2015, as reported by them to the mohinga.info system.

The website provides graphs showing the amounts allocated to the different states and regions, as well as the origin of the money being spent, and the amounts committed to different sectors.

According to the EU delegation, the site is still “very much” a work in progress and its compilers struggled to overcome some hurdles getting it to this point.

Though the site was supposed to be able to import data directly from the IATI, it was found that “many development partners weren’t yet reporting accurately or in detail (or

indeed at all)” to the international standards group, according to the delegation writing in a blog in February.

That meant that the Myanmar team had to input data manually instead. Recording multi-donor trust funds accurately without double-counting was also a headache.

Global development organizations preach the importance of transparency to the governments and community organizations with whom they work. Yet in practice it is often extremely difficult for citizens and media to access useful information about projects and work being undertaken by the aid donors and organizations themselves.

That makes the new site a welcome beginning for increased aid transparency in Myanmar, where for decades almost all forms of data was unavailable to the public.

The delegation said there was a plan to publicize the site widely to ensure that more people could access and use it.

Meanwhile, the information currently available makes for useful, and at times intriguing, reading. As is the case with most data, the information raises as many questions as it answers.

Japan is by far the biggest aid donor to Myanmar, committing over US$2 billion from 2011-15.

The allocation of aid across different parts of the country is also interesting. Why does Chin State receive three times more aid than Rakhine State? How come tiny Kayah State receives more than twice as much aid as its much larger neighbor, Kayin State?

It is to be hoped that answers to questions such as these and many others will emerge as the mohinga.info site develops and is used more by the public, the media and others. Time to start browsing. —The Irrawaddy

*The US$5.31 billion figure represents the total volume of commitments made thus far for the date range between January 2011 and December 2015, as reported to the mohingya.info system. The system is currently presented with a disclaimer explaining that the data depends on donor partners voluntarily submitting information on a continual basis, and that it is a workin-progress. Because some donors report aid as “nationwide” rather than by state or region, the figures for each territory do not align fully with the total aid figure.

Billions of aid money is being spent in Myanmar, but where exactly is it going? A new website aims to shed some light.

JAPAN

WB EU

UNIDENTIFIED

USAID

DFID (UK)

• Yangon Region with 14.3% of the population is receiving around 20% of the total aid to the country.

• Chin State with 0.9% of the total population is receiving three times more aid than neighboring Rakhine State with 6.2% of the population.

• Kayah State with 0.6% of the population is receiving well over twice the aid to neighboring Kayin State with 3.1% of the population.

• Naypyitaw with 2.3% of the population is receiving US$149.43m; much more than either Kayin, Rakhine or Mon States, and Tanintharyi Region.

• Shan State with 11.3% of the population is receiving more than one third of all aid to all the states. Rakhine, Kachin, Mon, Kayin, Kayah and Chin states combined, with 18.1% of the population, are receiving $771.70m.

*'Data-Points to Ponder' was compiled by The Irrawaddy based on information on mohinga.info and the recent census.

DFAT (AUSTRALIA)

ADB

INDIA

GOV.GERMANY

SDC (SWITZERLAND)

UNICEF-RR

SIDA (SWEDEN)

UNICEF

GOV.ITALY

MULTI

DANIDA

KOICA (SOUTH KOREA)

Sayadaw U Nayaka’s achievements on free and progressive education are matched by his determination to accomplish even more

By ZARNI MANN / MANDALAY

By ZARNI MANN / MANDALAY

About 25 young schoolchildren in white and green uniforms stand face to face in the classroom. They point at each other enthusiastically as they practice the personal pronouns “You” and “I” while their teacher patiently provides corrections and encouragement.

In another classroom for thirdgraders, some 20 students practice maths, brainstorming in English with their teacher. In another, children in small groups are playing a game with

cards bearing pictures of animals, fruits, vegetables and colors.

These are everyday classroom scenes at the Phaung Daw Oo Monastic School, located east of Myanmar’s second-biggest city of Mandalay, where in some classes, young Buddhist novices, nuns and other children all learn together.

The school began with a simple idea—“A free education for everyone”— and each year, students from near and far enroll, from kindergarten to

high school level, learning the same curriculum as other local government and private schools.

One of the defining features of the Phaung Daw Oo school is its “child centered approach” to education, led by school principal and the Abbot of Phaung Daw Oo Monastery, Sayadaw U Nayaka, who has also sought to deemphasize traditional practices of rote learning.

“It was around 1967, when I was about 20, that my younger brother Zawtika and I saw a huge Christian missionary school in Hinthada, Ayeyarwady Region, which was then a government school,” U Nayaka said. “We later found out about

missionary schools and their idea of free education inspired me to run a monastic school.”

For centuries, monastic schools were the only source of education for Myanmar’s youth until missionary and private schools were established during the British colonial period. Following the military coup in 1962, the popularity of monastic education dropped significantly in cities and towns across the country.

In order to achieve his dream of educating others, U Nayaka first had to educate himself. At the age of 24, he left the monastery in Mandalay to pursue a secondary education in a government school in Pyaw Bwe, Mandalay Region.

“To teach others, I had to learn the modern education [system]. I was the oldest person in the class. However, I was never disappointed to learn,” he said.

He remained in the monkhood throughout his secondary schooling and went on to study chemistry at Mandalay University, graduating in 1981.

In the early 1990s monastic schools regained popularity, particularly among children whose families could not afford regular school fees.

After being appointed as an abbot at Phaung Daw Oo monastery, U Nayaka and his brother U Zawtika, established the free monastic school for primary school children in 1993, registered under the Ministry of Religious Affairs.

In the beginning, teaching methods at the new school mirrored those of other government-run schools.

“As the years went by, I felt like something was still missing,” U Nayaka said. “Around the year 2000, when I learned about the child centered approach, I decided to change the teaching methods in my school.”

With the help of donors, U Nayaka sought foreign educators to help train local teachers. His emphasis on a child centered approach was quickly embraced by students, while parents initially remained skeptical.

“We received several complaints from parents that their children were getting very inquisitive, did no homework, [and that there were] fewer lessons in their notebooks than [students] in government schools,” U Nayaka said.

“We had to explain the child centered approach to them, which is not a ‘parrot learning’ method, and that the idea is to learn, not just writing notes.”

The school later expanded to incorporate a high school and in recent years has had around 6,0007,000 students enrolled each year, including orphans, ethnic children and children affected by Cyclone Nargis.

Around 300 local volunteer teachers are on hand each year, including foreign teachers from countries including Germany, the United States, Australia and the United Kingdom.

But it has not always been smooth sailing for Phaung Daw Oo’s students, some of whom have found their exam results don’t always stack up against students in government schools.

Jasmine, who attended the Phaung Daw Oo school since kindergarten, recently received the results of her matriculation exams.

“I received no distinctions and was quite disappointed. From a young age, what we learn here is based on creative thinking and critical thinking. We never learn the lessons by heart; we rewrite it or present it in our own words,” she told The Irrawaddy.

“But for matriculation exams, we can’t do that. We have to learn everything from A to Z, by heart, and have to write it down [exactly] as it is,” she added.

U Nayaka said a governmentled focus on rigid examinations discourages many students like Jasmine who are not familiar with the rote learning system—or, memorization based on repetition.

Only 30 percent of students from the monastic school passed the matriculation exams in the 2014-15 academic year, and only 185 students obtained distinctions.

After passing their final exams, students still face an uphill battle to gain entry into university, with places usually awarded according to examination marks.

“Since the total scores of our students are not comparable to the students who passed under the [rote learning] approach, most of them can’t usually study [subjects] like medicine, engineering or IT which require very high total scores,” a teacher at the school explained.

U Nayaka has his own possible solution: He dreams of opening a private, international-standard university offering free education.

“I think: what will these students do after they graduate from our high school? Most of them came here because they can’t afford tuition fees. Some of them can’t go to those universities because of their marks, but they are smart enough to become professionals,” he said.

U Nayaka’s plans stalled however, after the female donor of 400 acres of land for the site of the planned university in Mandalay Region’s Patheingyi Township was jailed in relation to the donation.

The Abbot’s vision has shifted

slightly to other forms of higher education.

“Currently, we are planning to open a pre-college class for the students and teachers who will go abroad for further study. Now we are testing the class, first with the students who graduate from our high school, and then we will allow outsiders later,” he said.

In Myanmar, monastic schools are the most popular option for poor or disadvantaged students. According to official figures for 2014, there are an estimated 7,000 teachers and more than 260,000 students enrolled in some 1,579 monastic schools nationwide.

The Phaung Daw Oo Monastic school motto is clear and simple: “Free and better education for everyone.” It takes pride in an inclusive approach, without prejudice based on gender, race or religion.

“Education is just education. We can’t mix it up with religion. In our school, we teach no students to be racists,” U Nayaka said.

“Our education system has been spoiled for many years so that our children can’t catch up to international levels. My belief is that with better education, with smart and welleducated people, we can create a better community, a better country.”

The government’s hopes of finalizing a nationwide ceasefire agreement before this year’s election appear to have shrunk considerably, after last month’s ethnic summit in Law Khee Lar in Kayin State voted to cede negotiating power to a new “hardline” committee.

From the perspective of government peace negotiators, two problems have arisen from the June 2-9 Law Khee Lar summit. First, ethnic leaders have refused to endorse the draft ceasefire text, demanding fresh negotiations over 15 amendments. Second, the new negotiating committee, which will assume the responsibilities of the Nationwide Ceasefire Coordination Team (NCCT), is comprised of people likely to be much less receptive to government overtures.

“We prefer to deal with the NCCT instead of a new committee,” said U Hla Maung Shwe, a director of the Myanmar Peace Center. “The NCCT members have become friendly with us already. But now they have formed a new committee and replaced the leaders. This could be a problem with our government as it will take time to build rapport, and the people leading the new committee are hardliners.”

The government has positioned the successful conclusion of a nationwide ceasefire agreement as one of the most important ambitions of President U Thein Sein’s tenure, but ethnic armed groups remain aloof, cautious of committing themselves to an accord

that would impede their push for a federal reform of the Constitution.

“Of course, the president wants to pass his exam,” said NCCT chief Nai Hong Sar. “He would be credited for being able to bring a ceasefire agreement during his term. But for us, we are worried that we will be trapped by the government after the agreement is signed.”

The formation of a new negotiating coalition is indicative of majority opinion at the Law Khee Lar summit. Ethnic leaders believe that the government has not made enough concessions to warrant signing the

ceasefire accord as it stands. For that reason, the new committee will be headed by Naw Zipporah Sein, the vice-chair of the Karen National Union (KNU), with Dr. Laja of the Kachin Independence Organization (KIO) as her deputy. Both spent time on the central executive committee of the United Nationalities Federal Council ethnic coalition, and both are representatives of factions less amenable to compromises with the government within their respective organizations.

On the sidelines of the Law Khee Lar summit, ethnic leaders appeared to be rankled by what they saw as pressure from the international community to sign an accord sooner. KNU member Naw May Oo Mutraw reportedly lashed out at UN envoy Vijay Nambiar, claiming that the international community did not understand the reality of the situation faced by ethnic armed groups in Myanmar.

Sources close to the organizations said that both the KIO and KNU, the political wings of two of the most powerful ethnic armed groups, had decided to withhold any agreement to sign the nationwide ceasefire deal until the general election expected later this year is demonstrated to be free and fair, and would not yield to any international pressure to expedite the process.

At the same time, the international community may prove to be a sticking point in future negotiations for very different reasons. Ethnic leaders want international observers present to witness the signing of the nationwide ceasefire agreement, while the government has rejected calls for their oversight, saying that a ceasefire accord is a purely domestic affair. The issue came up during previous negotiations between the government and the NCCT, before it was struck from the draft text of the ceasefire agreement unveiled on March 31.

Other exceptions to the draft text also emerged at the summit. Ethnic leaders resolved to have provisions relating to a federal army included

in any ceasefire agreement. As with other issues, this was excluded from the draft text after negotiations in the expectation that a settlement would be reached after the accord was signed.

Some leaders at Law Khee Lar criticized the draft text for lacking strong guarantees of political rights for ethnic groups, and said an agreement could not be signed without more explicit commitments on this front from the government’s Union Peacemaking Working Committee (UPWC).

Khun Okkar, a member of the NCCT, said he was skeptical of the new committee’s ability to secure more concessions from the government, but said the previous negotiators would abide by the summit’s decision.

“Some leaders thought that they could push for more rights, and this is why they told us to step down and let others talk to the UPWC,” he said. “We worked the best we could and it took a year and a half. Let them try, they may understand afterwards that it is not easy to talk with the military.”

He noted, however, that some of the ethnic leaders at the summit wanted to sign the nationwide ceasefire agreement as it stood, without waiting for three armed groups that had been excluded from negotiations by the government.

U Hla Maung Shwe warned that the government might not be willing to accept either a new negotiating bloc or a new discussion on amending the ceasefire text, noting that a date and time for further negotiations had not yet been set.

“They should have proposed [the amendments] before, why are they just proposing them now?” he asked. “This could be a problem. I feel the government might not accept this.”

Though his own position will eventually become redundant if the new committee proceeds, Nai Hong Sar said that the decision was in the hands of ethnic leaders and not negotiators.

“[The NCCT] cannot do anything,” he said. “Even if the government cannot accept the new committee or sign our draft text, this was the majority decision made by ethnic leaders.”

negotiating bloc.

A TAXING TRIP: Nine checkpoints on a 90-minute journey

Women are “a force for national development” says Ma Nang Lai Kham of the Kanbawza group of companies

Founded in 1994 by U Aung Ko Win, the Kanbawza (KBZ) Group of Companies manages a diverse set of business interests, including in mining, banking, real estate, aviation and insurance. The eldest daughter of the firm’s founder, Ma Nang Lai Kham, cut her teeth working at KBZ Bank, one of the largest private financial institutions in Myanmar, with nearly 200 branches across the country and with 113 billion kyat (US$101.9 million) in capital as of 2014. She has risen to become the chairwoman of Brighter Future Foundation, Air KBZ, KBZ Bank and Kempinski Hotel Nay Pyi Taw under the KBZ group of Companies. Ma Nang Lai Kham spoke with The Irrawaddy’s Kyaw Hsu Mon about the role of women at Kanbawza, promoting women business leaders and encouraging women’s participation in all sectors of the economy.

Women are playing a greater role in Myanmar’s economic life. What challenges do they face?

As the country has developed more and more and connected with the international community, people’s horizons have expanded. There are lots of opportunities for everyone now. Women account for 51.8 percent of the national population. Previously, women were stereotyped as housewives once they were married. But now, a certain number of women are leading businesses shoulder to shoulder with their male counterparts. Women now play an important role in the economic development of Myanmar and they are a force for national development.

What policies should companies adopt to enhance the role of women in the workplace?

I would like to talk about an empowering culture rather than a policy. I would encourage every staffer, regardless of their age and gender, to exercise discretion and take responsibility rather than adopting an overall policy for an entire company. On a level playing field, we award and give promotions to female staffers depending on

their competence, performance and expertise. In Kanbawza, we nurture a culture that provides equality and nondiscrimination on the ground of gender.

I believe that a large number of Kanbawza staff are women. Can you tell us about this?

Women account for 85 percent of staff in our Kanbawza Insurance Co. and about 53 percent for Kanbawza Bank. Women share senior positions with men in our company.

Married female staffers are entitled to maternity leave, fixed health allowances, plus leave to take care of their newborn babies if necessary. In addition, we assign duties that are appropriate for them when they return to work. We don’t transfer them to places far from their families.

We also provide training and do not discriminate on the ground of gender in providing training. We award staffers depending on their performance and expertise. Interestingly, 35 percent of customers who take loans from Kanbawza Bank are businesses that involve or are led by women.

How important is parental support to women who want to become successful businesswomen?

The guidance and support of parents are fundamentally important for a child to have success in life. On the other hand, a child who gets support from her parents needs to have interest in the business and devote tireless efforts. And she also needs to have big ambitions.

What do you expect will be the challenges as a young woman in relation to inheriting your family’s businesses?

Challenges exist everywhere, especially in Myanmar which is developing fast. We need to hand down a great deal of knowledge from generation to generation and systematize our companies for further development.

I, together with my sisters, had to work almost daily at the bank branches to be familiar with the job since we were young. To make sure there is no generation gap, we coordinate with our parents. For our business to last long and succeed, we need new ideas for each business. As the first generation has established the business, the second generation has to maintain the success and should have entrepreneurial skills.

We have joined the Business Families Institute in Singapore and have adopted strategies for the greater success of our company. We also attend and take part in discussions at the World Economic Forum’s New Champions.

What is your educational background?