TheIrrawaddy

TALKING PEACE, THINKING WAR

WHO ARE THE WA?

MOJO: HOT BY NIGHT, DAYTIME COOL

TRAVELLERS’ REST: SAGAING HILL

TALKING PEACE, THINKING WAR

WHO ARE THE WA?

MOJO: HOT BY NIGHT, DAYTIME COOL

TRAVELLERS’ REST: SAGAING HILL

The Irrawaddy magazine has covered Myanmar, its neighbors and Southeast Asia since 1993.

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF: Aung Zaw

EDITOR (English Edition): Kyaw Zwa Moe

ASSOCIATE EDITOR: Sandy Barron

COPY DESK: Neil Lawrence, Paul Vrieze, Samantha Michaels, Andrew D. Kaspar, Simon Lewis

CONTRIBUTORS to this issue: Aung Zaw; Saw Yan Naing; Kyaw Phyo Tha; Simon Lewis; Bertil Lintner; Zarni Mann; Kyaw Hsu Mon; Oliver Gruen; Marwaan Macan-Markar; Sanay Lin; Virginia Henderson.

PHOTOGRAPHERS : JPaing; Sai Zaw, Aue Mon.

LAYOUT DESIGNER: Banjong Banriankit

SENIOR MANAGER : Win Thu (Regional Office)

MANAGER: Phyo Thu Htet (Yangon Bureau)

REGIONAL HEADQUARTERS MAILING ADDRESS: The Irrawaddy, P.O. Box 242, CMU Post Office, Chiang Mai 50200, Thailand.

YANGON BUREAU : No. 197, 2nd Floor, 32nd Street (Upper Block), Pabedan Township, Yangon, Myanmar. TEL: 01 388521, 01 389762

EMAIL: editors@irrawaddy.org

SALES&ADVERTISING: advertising@irrawaddy.org

SUBSCRIPTIONS: subscriptions@irrawaddy.org

PRINTER: Chotana Printing (Chiang Mai, Thailand)

PUBLISHER LICENSE : 13215047701213

4

Jokowi: “People like to see leaders

WANTED: HAPPY ENDING FOR MOVIE INDUSTRY

12

Reforms for Who?

LIFESTYLE

47

Travel: Above It All

Looking for a break from the mundane? Head to Sagaing Hill

50

Culture: A Purr-Fect Pedigree

Burmese cats receive the royal treatment they know they deserve

54

Destinations: Serene Sangkhlaburi

A little-known border town is full of understated allure

58

City Life: Pedal Power

Yangon’s rickshaws offer a unique way to see the city

62

Food: Hot Nights and Daytime

Cool

MOJO gets the mix right for Yangon's nightowls

64

Backpage: Fairy Tales From Afar

Stories for children by Václav Havel are now available in the Myanmar language, with illustrations by U Min Ko Naing

36 |

38 |

14 | Politics: Talking Peace, Thinking War

Myanmar’s vaunted “peace process” is in danger of collapsing, as the beating of war drums begins to drown out the sound of talks

18 |

Politics: Who Are the Wa?

Feared and poorly understood, the Wa have always shunned central control but play a key role in Myanmar’s tense border politics

24 |

Society: Black Gold Rush

Oil fields abandoned by Myanmar’s state-owned oil company have turned into a lawless arena

28 |

COVER Wanted: Happy Ending

Myanmar’s film industry struggles to find its way after decades of decline

Interview: Philip Maung, Sushi Success Story

Aviation: Will Private-Public Partnerships Fly?

Myanmar’s bid to upgrade its airports with investment from the private sector runs up against some economic realities

42 | Signposts: Corruption Tops Concerns

44 |

Bottlenecks on the Road to the AEC

As the Asean Economic Community comes closer to becoming a reality, efforts step up to remove border snags

JAKARTA – For Indonesia’s presidential front-runner, a campaign to alleviate poverty in the Indonesian capital is largely personal, stemming in part from his own experiences as a child.

Joko Widodo, better known by his nickname Jokowi, is the governor of Jakarta and the top contender for the Indonesian presidency to be decided on July 9, but he traces his roots back to the small Central Java city of Solo,

where he grew up as the son of a furniture maker and lived with his family in a rented shack.

He later earned an engineering degree and entered the family furniture business, before shifting to politics and making a name for himself as mayor of Solo from 2005 to 2012.

“When I was a small boy, I was not part of the elite, not from a rich family,” Jokowi said recently during a roundtable discussion with reporters in

Jakarta. “Around my house there was garbage, and there was no water, there was no well. This is my story.”

As mayor in Solo he focused on making health care and education more accessible to low-income families, while also building low-cost apartments.

“Now I’m here, as if by accident,” he said with a laugh, referring to his climb in 2012 to become the governor of Jakarta, where he is employing many of the same strategies to help low-income families in the chaotic metropolis of some 10 million people.

But many political observers say his success was far from accidental and can be credited in part to his hands-on approach.

“Many people have said that I’m different because the other governors, they like to stay at the office. For me, I stay at the office only a maximum of one hour [per day],” Jokowi said. “Mostly, I go to see people on the ground, in the markets, and I ask people what they want and what they need.”

As a result, Jokowi has won the hearts of many voters in Jakarta and far beyond in this archipelagic nation. His popularity led his party to announce in mid-March that he would be its candidate for the presidency.

Inspiring hope for change in a country that has long been plagued by corrupt officials, he has been compared with the 2008 version of US President Barack Obama, who championed the slogan of “change we can believe in.” Jokowi’s victory for the Jakarta gov-

ernorship in 2012 was widely seen as reflecting popular voter support for “new” or “clean” leaders rather than the “old” style of politics in Indonesia. During legislative elections this month, posters with his portrait could be seen in public areas of downtown Jakarta, while buskers with guitars sang songs calling him their “life and hope.”

As part of his poverty alleviation efforts in the capital, Jokowi has focused on making health care more affordable. To do this, he has delivered “Jakarta health cards” to 3.5 million people in the city. With the cards, he said, “they can go to public clinics, they can go to the hospitals, totally free of charge. I worked out this program because people asked me for this when I met them.”

Access to education is another major concern. Ms. Nining, a 40-year-old bookseller in Jakarta, said she could not afford to attend university when she was younger. “Education costs are very expensive in Indonesia. I think the government hasn’t done enough for the people,” she told The Irrawaddy.

Jokowi said his administration was working on that.

“We also have what we call ‘Jakarta smart cards.’ This is for education,” he said. “When I would go to see the people and I asked about education, they asked the government to cover the cost of school uniforms, school vans,

boots [and] shoes for the poor,” he said.

He added that Jakarta’s annual budget had increased from 41 trillion rupiah (US $3.5 billion) last year to 72 trillion rupiah this year.

The Indonesian presidency will be decided in July by direct election. Candidates will be nominated by parties that hold at least 20 percent of seats in the legislature, or parties which have formed a coalition representing that percentage of seats, or those that took 25 percent of seats in the previous election.

Jokowi’s party, the Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle (PDI-P), only won 19 percent of seats in the legislative elections on April 9. Since then it has started forming coalitions with other parties, including the National Democrat Party and most recently the National Awakening Party.

Despite earning popular support on the coattails of Jokowi, the PDI-P is not immune to the negative voter sentiment that has affected many of the established political parties in a country where corruption stories are a regular feature of newspapers’ front-pages.

But Jokowi hopes he can continue earning voters’ trust.

“When I see people protest, I invite them to my office. We discuss, and sometimes I go directly to the demonstration places,” Jokowi said. “I have opened city hall, and now people like to come here because they can meet with me and tell me their complaints.”

“People want to see their leaders working,” he said. “If we build a good system for them, people will trust the government.”

President U Thein Sein’s handing of national excellence awards to several tycoons raised eyebrows last month. Some citizens and environmentalists were particularly upset over the National Best Social Welfare Team award, which went to the Htoo Foundation established by U Tay Za, chairman of the Htoo Trading Group.

The US-sanctioned Htoo Company made much of its fortune by cutting deals with former military regime. Since the 1990s, the company expanded from agribusiness into large-scale logging of natural forests, before moving into mining, construction and hotels, airlines and banking businesses.

—Brig.-Gen. Tin San, head of army representatives in the lower house, speaking in mid-May

—Singapore’s Prime Minister Lee Hsein Loong on a tour of Pyinmana during the 24th Summit of Asean Leaders in mid-May

“Her view of the army is wrong. Our history shows that we serve the people, which is why army representatives make up 25 percent of Parliament.’’

‘‘I want to tell all military men that their active involvement in charter amendments is what the people want.’’

—Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, at a rally in MayILLUSTRATION: ATH

‘‘It looked and felt like Singapore or Penang in the 1950s and 1960s, except that many of the residents were taking pictures of us with smartphones!”

standoff over a Chinese fishing boat seized by the Philippines off the disputed Spratly Islands, set the backdrop for the gathering in Naypyitaw.

In a joint statement released on May 10, Myanmar Foreign Minister U Wunna Maung Lwin and his regional counterparts urged all parties to act in accordance with international law and “avoid actions which could undermine peace and stability in the area.”

In the wake of yet another fatal crash on the main Yangon-Naypyitaw-Mandalay highway, Myanmar’s government has put the blame for the country’s poor road safety record squarely on the shoulders of reckless drivers.

Escalating tensions in the South China Sea were high on the agenda as Myanmar hosted its first ever summit of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (Asean) on May 10-11.

Anger over China’s decision to station a giant oil rig in Vietnamclaimed waters on May 1, and a

Anxiety over China’s growing assertiveness in the region has threatened to undermine Asean unity, as some member states seek to avoid harming relations with Beijing.

However, President’s Office spokesperson U Ye Htut denied that Myanmar was under pressure from its northern neighbor to act in its favor. “China has not tried to influence us on this issue,” he said.—Kyaw Hsu Mon

Citing a government study on the causes of most accidents on Myanmar’s roads and highways, U Soe Tin, the deputy minister of construction, said that driver error was the chief culprit, followed by vehicle failure.

Only 1 percent of accidents were due to poor road quality, he told the staterun newspaper The Mirror.

Fourteen people were killed, and 20 injured, when a passenger bus skidded off a bridge as it was traveling from Naypyitaw to Yangon on May 12. At least 80 people have been killed on Myanmar’s main highway so far this year.—The Irrawaddy

Myanmar civil society organizations that object to a proposed law to “protect women” from marriage to Muslim men are “traitors,” according to leaders of a Buddhist nationalist group.

The group, known as the 969 movement, or the Association for the Protection of Race and Religion, has hired lawyers to draft an intermarriage bill that would require Buddhist women to get permission from their parents and government officials before marrying Muslim men.

It claims that 4 million people have signed a petition in support of the bill, which will

be publicly released in early June.

In a statement released in early May, the group said it “condemns those critics, who are backed by foreign groups, for raising human rights issues and not working for the benefit of the public and not being loyal to the state.”

U Wirathu, a prominent Mandalay-based monk who is widely seen as the leader of the 969 movement, told The Irrawaddy that the legislation “does not violate the rights of women,” but declined to respond to the concerns of rights groups.—Nyein Nyein and Nang Seng Hom

The Kachin Independence Army (KIA) released 21 villagers on May 16, days after dozens of people protested in the Kachin State capital Myitkyina alleging that the group had forcibly recruited young family members.

The protest by local ethnic Shan people took place on May 13 at the liaison office of the Kachin Independence Organization (KIO), the political wing of the KIA. It came as a delegation from the rebel group was in Myitkyina for talks with government representatives.

Many of the protesters identified themselves as mothers of children who were, they say, taken away to serve in the KIA after fighting in the current war with Myanmar’s government army intensified in 2012.

Meanwhile, hundreds of ethnic Kachin supporters gathered to welcome the KIA delegation and pray for peace in the strife-torn region.—Lawi Weng

Military men serving in Myanmar’s Parliament are not pleased with opposition leader Daw Aung San Suu Kyi’s recent remarks that the army is responsible for constitutional amendments.

During a rally in early May to garner public support for changes to the charter, the National League for Democracy (NLD) leader told supporters in Ayeyarwady Region that army MPs have an obligation to participate more in the constitutional reform process.

Brig-Gen Tin San, head of army representatives in the Lower House, slammed her comments.

“She has a hidden agenda. Her focus is only on fixing Article 436 to make way for her presidency,” he said, referring to a constitutional ban on anyone with family ties to foreign nationals becoming president.

As Myanmar prepares for national elections next year, the NLD and other opposition forces are stepping up efforts to amend sections of the Constitution they regard as undemocratic, including a provision that guarantees the military 25 percent of seats.

The ruling Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP), which consists largely of former servicemen, was similarly critical of Daw Aung San Suu Kyi’s views.

“In my opinion, our people right now are interested in making a proper living, not in fixing the charter,” said retired colonel U Min Swe, a USDP MP.—Sanay Lin

Leader of the 88 Generation Peace and Open Society U Min Ko Naing and National League for Democracy leader Daw Aung San Suu Kyi during a rally calling for amendment of the 2008 Constitution at Bo Sein Man Stadium in Yangon on May 17.

still poor today—maybe even poorer, because even if the standard of living hasn’t risen, the cost of living certainly has.

Perhaps these are early days, and things really will pick up dramatically in the long run. But if you were to listen to many of Myanmar’s newfound foreign friends, you would think that the country has already taken great strides, and that the Golden Land gold rush can only continue apace.

For many, resource-rich Myanmar, with its vast pool of cheap labor and seemingly unlimited potential for development, is simply too good to pass up. Add to this the fact that it occupies a strategically important corner of Asia, at the crossroads of India, China and Southeast Asia, and you can soon understand why foreigners are so keen to increase their influence here.

Even when it was a pariah to much of the rest of the world, Myanmar was an attractive place for investors and governments from neighboring nations. Now, however, it’s not just a handful of countries vying for a piece of the action, but a whole world of well-wishers with dollar signs in their eyes, looking to pull Myanmar into their orbits.

More than three years have passed since Myanmar embarked on a series of reforms that many foreign observers hailed as the start of a new democratic era. For most people inside the country, however, the signs of change have been far less dramatic.

Ask the average person in Yangon or any other part of the country if their life has improved since the current quasi-civilian government came to power in 2011, and their response will likely be ambivalent at best.

Yes, they might say, there are more newspapers for sale now. But if you read them, what will you find? War still raging in the north, sectarian violence on the rise, journalists and protesters getting locked up—the same old story.

How about the economy? Doesn’t that look more promising than before?

Yes, if you were rich to begin with. But if you were poor before, you are

It was the United States that opened the floodgates when, in November 2011, President Barack Obama sent his secretary of state, Hillary Clinton, for a historic visit that signaled the end of Myanmar’s long era of isolation from the West. But even before then, some countries—notably Norway and several European Union nations—were moving closer to engagement with a regime that many critics considered beyond redemption after decades of human rights abuses and disastrous mismanagement of the economy.

Norway always seemed an unlikely advocate for closer relations with the junta, given its history of supporting the pro-democracy movement. By bestowing the Nobel Peace Prize upon Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, the figurehead of the movement, the Norwegian Nobel Committee raised her stature to that of an international icon. And by funding and hosting the Democratic Voice of Burma, Oslo put itself firmly on the side

of those seeking democratic reforms inside Myanmar.

All of this began to change in the late 2000s, when Oslo decided it was time to change its tack and begin putting more emphasis on economic engagement and stop urging Norwegian companies to refrain from trade and investment in Myanmar.

In due course, Norway’s controversial gamble on engagement paid off, both in terms of reforms (which one Norwegian diplomat haughtily informed me Oslo had “foreseen”) and

in terms of lucrative contracts with Myanmar’s self-styled “reformist” government (including a license for Norwegian multinational Telenor to develop Asia’s last frontier in mobile and Internet expansion, and another for Norwegian state-owned firm Statoil to explore one of Myanmar’s most promising offshore oil and gas blocks).

Now Norway and many other countries—from Australia to the United States, and Germany to Japan—are so heavily invested in this reform success story that nobody wants to hear that it

is still far from clear whether Myanmar is really moving in the right direction.

Perhaps from a distance, such doubts seem unwarranted. But until the people of Myanmar can begin to feel that they are the true beneficiaries of their country’s supposed “reforms,” foreigners who have done well off of the government’s newfound openness should probably keep their selfcongratulations to themselves.

More than three years after Myanmar’s quasicivilian government assumed power and made plans for a nationwide ceasefire a centerpiece of its bid for international acceptance, the country is no closer to peace, and could soon descend once again into civil war.

This grim assessment of the situation in Myanmar’s border regions, where ethnic armed groups have long fought central control, is supported by

evidence that both government and rebel forces are girding for war, even as they continue to engage in talks that are moving no closer to a compromise acceptable to the opposing sides.

While international stakeholders remain hopeful and largely oblivious to the tensions on the ground, those with the most at stake—the people who live in areas that would be thrown into turmoil by a resumption of war—are growing ever more pessimistic.

After decades of war, ethnic armed groups and local civilians say they want peace, but don’t believe the government is really interested in finding a solution that would permanently end conflict.

“We all want peace, but we want a kind of peace real enough that we can sleep at night and not worry about our physical and cultural extinction in the morning,” said Gen. Baw Kyaw Heh, the vice commander-in-chief of the Karen National Liberation Army (KNLA).

The KNLA’s political wing, the Karen National Union (KNU), began its struggle for ethnic Kayin autonomy in 1949, and has never come closer to ending its struggle with Myanmar’s government than it is today. But as negotiations with the administration of President U Thein Sein fail to reach a lasting settlement, its faith in the peace process is fading fast.

“The way the government is trying to secure peace with the ethnic minorities is not sustainable in the long term. It can break down anytime, and when it does, it will even be worse,” said Gen. Baw Kyaw Heh.

“The government will also face a much worse situation,” he added,

warning that Naypyitaw also has a great deal to lose if it doesn’t live up to the expectations raised by promises of peace.

As the U Thein Sein administration continues to talk up the peace talks, both the government army and the ethnic armed groups appear to be betting that it is only a matter of time before they are back on a war footing. While their leaders meet across the negotiating table, all parties have been busy beefing up their military positions and recruiting new foot soldiers.

Myanmar’s military leaders have been especially keen to demonstrate their battle-readiness. In late February, they staged a well-publicized livefire military exercise dubbed the “Anawrahta war games,” after the founder of the 11th-century Bagan Empire.

British security analyst Anthony Davis, writing in Asia Times Online, noted that the games “involved a panoply of military power centered on mechanized infantry of the Magwaybased 88th Light Infantry Division using indigenously produced Ukrainian armored personnel carriers and Chinese infantry fighting vehicles.”

According to Mr. Davis, “The infantry was supported by intense firepower from main battle tanks, a range of artillery systems including

Gen. Baw Kyaw Heh was commander of KNLA Brigade 5 until his promotion to vice commander-in-chief of the KNLA in December of last year. PHOTO: SAW YAN NAING PHOTO: SAW YAN NAINGmultiple launch rocket systems (MLRS), 105mm and 155mm howitzers, and close air support in the shape of rocket-firing Mi-35 helicopter gunships and low-flying MiG-29 air superiority fighters.”

Asked what he thought of this show of military might, the KNLA’s Gen. Baw Kyaw Heh dismissed the government’s insistence that it was primarily concerned with “external threats.”

“The actual threat is very much domestic. The problems are domestic and institutional. In fact, they [the government] want to show off their military capacity to ethnic groups. It is a sort of threat to ethnic armed groups,” he said.

While the international community hails the current round of ceasefire talks as a major step toward long-term stability, many inside the country fear that any peace achieved will be temporary at best.

One reason that hope seems so elusive is that Myanmar has been here before. In the 1990s, the country’s then military rulers succeeded in bringing several armed groups “into the legal fold”—most notably, the Kachin Independence Army (KIA), which signed a deal to stop fighting in 1994. But while this agreement brought some relief to local civilian populations caught in the crossfire, it left many

issues unresolved, and in 2011, the ceasefire collapsed completely and quickly turned into a brutal conflict that continues to this day.

Ashley South, a longtime observer of Myanmar’s ethnic conflicts who works as a consultant for the Myanmar Peace Support Initiative, a Norwegian government-backed international peace advocacy group, acknowledged that the current offensives against the KIA, as well as the government army’s apparent unwillingness to accept ethnic armed groups’ key demands, are a major concern.

“I do not believe the peace process can be sustainable unless there is a political settlement which includes ethnic demands for a renegotiation of state-society relations, along federal lines,” he said.

He added that there was also a danger that “international donors and aid agencies are increasingly working in conflict-affected areas, in ways which promote the government agenda, without adequately consulting local communities, civil society actors and ethnic armed groups.”

Despite these concerns, however, Mr. South said he believed the international community should continue to support “the existing ceasefires and emerging peace process.”

If civil war does break out again, ethnic observers warn that it won’t be

confined to remote ethnic areas, and could be even worse than anything the country has seen to date. Growing unity among the armed groups, they say, would mean a nationwide conflict that would not spare Myanmar’s cities.

Meanwhile, the KNLA and other armed groups say they are bracing for a government army offensive that could come at any time—perhaps as soon as this summer, or early next year, ahead of elections whose outcome could be determined in large part by the government’s success in reaching a nationwide ceasefire agreement.

As the ethnic armed groups step up their recruitment efforts, military training and exchanges with each other, the government army is planning offensives against the KNLA’s Brigades 5 and 2, according to intelligence intercepted by the KNLA from satellite networks.

Like the offensive against the KIA stronghold of Laiza in late 2012 and early 2013, the assault on the “hardline” KNLA brigades (which have resisted a ceasefire agreement) will involve airpower, KNLA sources say. The government army has set up helicopter landing pads and stockpiled rocket launchers and artillery shells at frontline bases in northern Kayin State

near where Brigade 5 and 2 are based. Similar activities by the government army have also been reported in Kachin State and Shan State.

According to a wide range of ethnic sources from Kachin State in the north to Kayin State in the south, both ethnic and government forces are on high alert. In the case of the ethnic armed groups, that means maintaining regular contact with each other and preparing to fight if any of them come under attack.

While Myanmar’s ethnic armed groups band together in anticipation of resumed fighting, many now see the United Wa State Army (UWSA), the most heavily armed among them, as an example worth emulating.

The UWSA is not just the most formidable fighting force in the country outside of the government army; it also controls an autonomous region that

functions like a totally independent state, complete with its own civil administration and police force.

More importantly, perhaps, it has its own weapons factories, producing mostly AK47 rifles that it is happy to supply to other armed groups. It has also taught the smaller groups how to make weapons of their own and helped them purchase arms on the black market.

All of this is necessary, the ethnic armed groups believe, because government troops continue to reinforce their positions in ethnic areas despite repeated calls for their withdrawal as a condition for agreeing to a ceasefire. For most, this is a clear sign that the talks now taking place are little more than a stalling tactic.

“We must be ready for anything,” said Saw Der Lwe, a KNLA soldier. “Even if there is a ceasefire, we don’t know how long it will last. They [the government army] could do anything, suddenly and without warning.”

It seems very likely that the United Wa State Army (UWSA) will become the next target of the Myanmar government’s efforts to bring the country under its control. But that does not necessarily mean that the army will launch an all-out offensive against the country’s most heavily armed ethnic army. A more likely scenario, insiders say, would be for the Myanmar military to capitalize on internal divisions within the UWSA first, play one faction against another— and attack only when the group has been considerably weakened.

But would that work? And who, exactly, are the Wa? In the Myanmar media, they are often portrayed as some kind of Chinese group, and it has even been suggested that the UWSA may follow the secessionist example set by Crimea, which recently held a referendum and joined Russia. In a similar fashion, the UWSA could hold a referendum in the area under its control, and then decide to merge it with China.

This scenario is extremely unlikely, however, because China would never accept such a move, as it would antagonize the whole of Southeast Asia and most of the rest of the world. And, needless to say, the Wa are not a “Chinese people.” They are a MonKhmer-speaking tribe whose closest ethnic relatives in Myanmar would be the Palaung and, much more distantly,

the Mon. (There are ethnic Wa across the border in China as well, where they number about 400 000, but they are an ethnic minority in Yunnan and not related to the majority Han Chinese.)

But one also has to remember that the Wa Hills of northeastern Shan State have never been ruled by any central Myanmar authority. What the Wa want their future to be is, therefore, a major concern that cannot be ignored.

Even during the British colonial era, governmental presence in the Wa Hills was limited to annual flag marches up to the Chinese border. The Wa were headhunters and feared by the plainspeople, and the British troops that carried their flag up to the border were always heavily armed.

The Wa Hills were first surveyed by outsiders in 1935-36, when the Iselin Commission began to more firmly demarcate the border between the Wa Hills and China, which was finally agreed upon by the British and the Chinese in 1941. Even so, the Wa Hills were never fully explored and were only nominally under British and later Myanmar sovereignty. The first road in the area was built in 1941, from Kunlong near the Thanlwin River and into the northern fringes of the Wa Hills.

The British-initiated Frontier Areas

of Enquiry—set up to ascertain the views of Myanmar’s many minority peoples just before independence—reported in 1947 that the Wa Hills “pay no contribution to central revenue… there are no post offices…and the only medical facilities are those provided by the Frontier Constabulary outposts… and by [non-certified] Chinese practitioners.”

The Wa did, however, send three representatives from their “states,” as their fiefdoms were called, to the com-

Feared and poorly understood, the Wa have always shunned central control but play a key role in Myanmar’s tense border politics

mittee’s hearings in Pyin Oo Lwin—and those talks revealed the gap between the Wa way of looking at life and the committee’s perception of it: Do you want any sort of association with other people?

Hkun Sai [for the Wa]: We do not want to join anybody because in the past we have been very independent.

Sao Naw Hseng [for the Wa]: Wa are Wa and Shans are Shans. We would not like to go into the Federated Shan States.

What do you want the future to be in the Wa states?

Sao Maha [for the Wa]: We have not thought about that because we are very wild people. We never thought of the administrative future. We think only about ourselves.

Don’t you want education, clothing, good food, good houses, hospitals?

Sao Maha: We are very wild people and don’t appreciate all these things.

In retrospect, this exchange of views may appear almost farcical, but

it nevertheless shows that the Wa did not think of themselves as citizens of Myanmar—and that was not going to change after independence in 1948.

In the 1950s, most of the Wa Hills were occupied by renegade Nationalist Chinese Kuomintang forces that retreated across the border into Myanmar following their defeat by Mao Zedong’s

Communists in the Chinese civil war. The Kuomintang established bases in the Wa Hills and in the mountains north and south of Kengtung, from where they tried on no less than seven occasions between 1950 and 1952 to invade Yunnan, but were repeatedly driven back to the Myanmar side of the border. The parts of the Wa Hills where the Kuomintang was not present were controlled by various local warlords.

The Kuomintang’s presence in northeastern Myanmar was a major reason why China decided to support the Communist Party of Burma (CPB) in the early 1960s. Myanmar Communists in exile in China began surveying the border as early as 1963 to identify possible infiltration routes. On Jan. 1, 1968, the CPB—and the Chinese—made their move. The old Kuomintang bases were some of the first targets. And while the political commissars were Myanmar Communists, the foot soldiers were almost exclusively “volunteers” from China.

It was only when the CPB had captured the Wa Hills in the early 1970s that its “people’s army” began to consist of recruits from Myanmar. Before long, the bulk of the CPB’s fighting force was predominantly Wa. But China was still supplying the CPB troops with all their weapons and other equipment, which made them the most formidable rebel army in Myanmar.

By the mid-1970s, the CPB had established control over more than 20,000 square kilometers of territory in northeastern and eastern Shan State. Myanmar’s central authorities were as remote and alien as they had always been in regards to the Wa Hills. But it was also clear that there were severe frictions between the CPB’s ageing Bamar leadership and its mostly hilltribe troops, who had little or no sympathy for communist ideals.

In 1989, the tribesmen rose in mutiny and drove the old leaders into exile in China. But there is every reason to believe that the Chinese had a hand in the mutiny as well. Just a few months before it broke out, the CPB’s politburo had held a meeting and the

then-chairman Thakin Ba Thein Tin, read out a message from the Chinese authorities. The entire CPB leadership had been offered retirement in China. It was clear that China no longer was interested in exporting revolution to Myanmar, but wanted to open the border for trade and exploit the natural resources in the frontier areas.

Thakin Ba Thein Tin was furious. “We have no desire to become revisionists,” he said, indicating that he considered the post-Mao leadership in China to be revisionist—which was enough for the Chinese to encourage the rankand-file of the CPB to rise up in mutiny.

And so the UWSA was born. Almost immediately, the newly formed group

entered into a ceasefire agreement with the Myanmar government, which allowed it to retain control of its area and its weaponry in exchange for not fighting the government’s army.

This led to the formation of the UWSA’s current territory, which it claims consists of 13,514 square miles (35,000 square kilometers), including new areas along the Thai border that were captured in the early 1990s. With a population of 400,000 and its own local administration, schools, hospitals and even a bank, this “mini-state” is almost unique in recent Asian history. The closest comparison would be to the parts of Sri Lanka that were ruled by the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam

(LTTE) until it was wiped out by a massive government offensive in 2009.

The currency used in the UWSA’s area is the Chinese yuan, and mobile telephones are connected to Chinese networks. Chinese is much more widely spoken than Myanmar. With Chinese assistance, the UWSA has also managed to build up an army that is both stronger and better equipped than the CPB ever was. Its arsenal includes Man-portable air-defense systems (MANPADS), a wide range of mortars and rocket launchers, and even light tanks and a few helicopters.

Recently, a helipad has been constructed at the UWSA’s Panghsang headquarters, with a sign outside saying, in Chinese, feijichang, or airport. Even more worrying, on Oct. 30 of last year, the local Myanmar intelligence office in the garrison town of Tang-yan sent a message to the regional command headquarters in Lashio saying that the UWSA was constructing a “radar and missile base” in its area.

The first location was supposed to be Mong Mau in the northern Wa Hills, but when the government found out about it, U Thein Zaw, the vice chairman of the Union Peace Working Committee, was sent to Panghsang to tell the Wa not to go ahead with their missile project. The UWSA leaders said that they wouldn’t—and changed the location to Wing Gao, closer to Panghsang.

The new facility is going to be built in partnership with a Chinese company called Liao Lian and equipment will be bought from China, Taiwan and Pakistan, the report asserts. It is not clear, however, what kind of missile it is, but given the fact that radars will be installed at the base, it is plausible to assume that it would be something more powerful than what the UWSA has

With a population of 400,000 and its own local administration, schools, hospitals and even a bank, this “mini-state” is almost unique in recent Asian history.

in its current arsenal. The Myanmarlanguage report uses the term taweipyetonggyi, or “long-distance missile.”

So it is abundantly clear that the Wa have no intention of submitting to the authority of a country that they feel that they have never been part of. The Wa Hills have gone from being ruled by nobody to being occupied by the Kuomintang and then the CPB, and are now administered by the UWSA.

But what are the Chinese up to and why are they making sure the UWSA is

armed to the teeth? The simple answer is that China does not actually want the UWSA to fight the Myanmar army, but would like to see it strong enough to deter any attack against it.

For China, the UWSA is a useful bargaining chip when Beijing wants to put pressure on the Myanmar government not to stray too close to the West, or to protect Chinese investment in the country. The latter concern became especially important after President U Thein Sein’s government decided in September 2011 to suspend the US$3.6 billion Myitsone hydroelectric dam project in Kachin State. China also has

to deal with ongoing protests against a copper mine project in Letpadaung, which is a joint venture between the Chinese Wanbao Mining Copper company and the Union of Myanmar Economic Holdings.

In other words, any military action against the UWSA would pit the Myanmar army against China. The Wa leaders are always accompanied by Chinese intelligence officers, and it is no exaggeration to say the UWSA is an extension of China’s People’s Liberation Army.

So would the Myanmar army risk a conflict with the UWSA? Sri Lanka’s offensive against the LTTE was successful because the Tamil militants had nowhere to retreat to when they came under attack, whereas an attack on the UWSA would force tens of thousands of refugees into China, causing further frictions between Myanmar and its powerful northern neighbor. The UWSA’s MANPADS would also enable it to shoot down airplanes and helicopters.

At the same time, however, no government in Myanmar can tolerate a continuation of the present situation in northeastern Shan State: a pocket-state with its own army. But if the present government wants to succeed where all its predecessors have failed—to convince the Wa that their hills are indeed part of Myanmar—a different approach than the military option may be needed.

A divide-and-rule scheme, which seems to be what is in the offing, may also cause resentment and divisions that could result in an even messier situation than what we have now.

But before the end of the year, some action is bound to take place in the Wa Hills. And whatever shape it takes, it will be a much more serious challenge than any of the other ethnic conflicts that have been plaguing Myanmar for decades. It will involve an area never before controlled by any Myanmar government—and China.

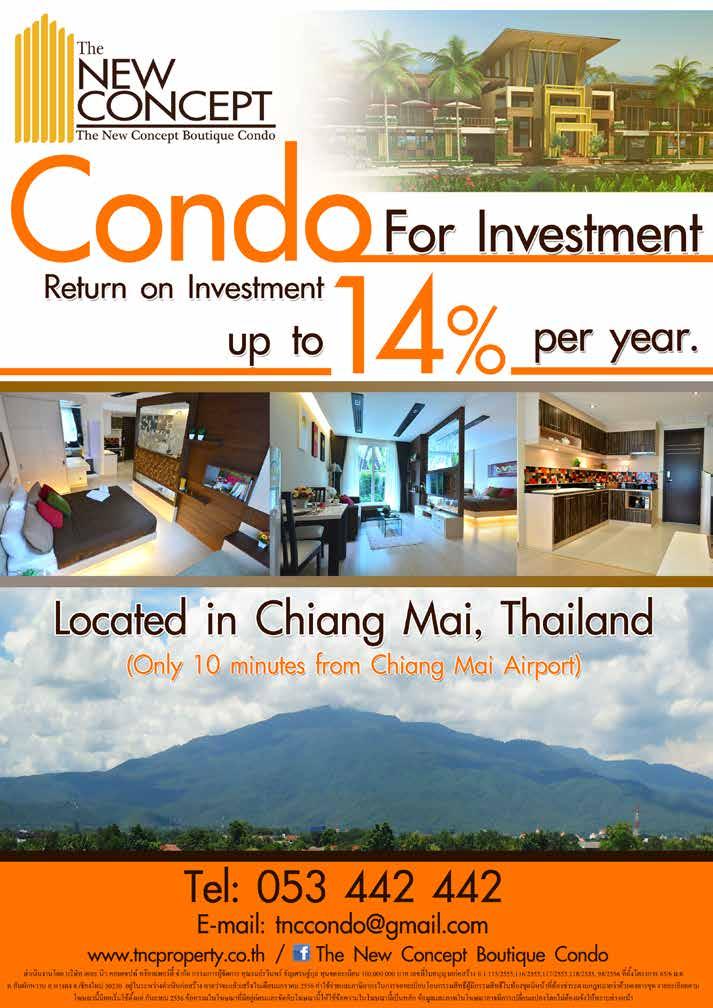

Feel the benefits of superior boutique-style living, blending modern and Asian culture. Enjoy the peaceful and charming atmosphere in the heart of Chiang Mai, at Sirimangkalajarn Road, Soi 1, close to the shopping, art, food and cultural district of Nimmanhaemin Road. A perfect choice for a convenient lifestyle. Lose yourself in our facilities, including swimming pool with salt chlorinated system, fitness and green area.

By SANAY LIN / MINHLA TOWNSHIP, Magway Region

By SANAY LIN / MINHLA TOWNSHIP, Magway Region

It’s been more than a year since the farmers of Htankai and Dahatpin, two villages in southern Magway Region, regained control of land that was taken away from them nearly two decades ago, but so far, their fields are still far from green.

In April of last year, in a rare reversal of the rampant land-grabbing that marked Myanmar’s era of military rule, the government instructed the stateowned Myanmar Oil and Gas Enterprise (MOGE) to return land that it had seized in 1996 to form a joint venture with private firms.

Since then, however, the only thing that has been growing in the affected 25-mile (40-km) wide tract of land is the number of oil wells run by small-scale operators looking to soak up some of

the black gold that MOGE left behind.

“There were two oil fields, Htankai and Dahatpin, under our supervision, but now the joint venture is gone and we’re not working there anymore,” said an MOGE engineer who asked not to be identified. “Now it’s being explored illegally.”

By some counts, there are now more than 55,000 wells covering the bleak, blackened stretch of ground that the government wants turned back into productive farmland. Of those, more than 20,000 appeared after the MOGE decided last June to abandon its efforts to enforce an end to drilling in the area—one of the conditions under which it agreed to return the land.

Although many farmers said they intended to honor their promise to bring

Scenes from southern Magway's oil rush, where the work is hard and rewards are uncertain.

the land back under cultivation, the influx of outsiders who came to exploit the region’s resources made it difficult for them to grow their crops.

“When the farms were given back to us, we weren’t allowed to drill and we didn’t receive any money from the other oil drillers. As they continued drilling, we couldn’t grow any crops and life got much harder for us,” said U Aung Moe Hein, a resident of Htankai.

“To be frank, if other people are taking crude oil, we’d like to do it too,” he added.

What most local landowners are doing, however, is charging for the right to sink small wells on their land, for a fee of anywhere from 100,000 kyat to 1.5 million kyat (US $100-1,500) per well, depending on the yield.

While this has brought some welcome income into the region, it has also come with a serious drawback: a dramatic rise in crime, as unregulated drilling and a push for quick profits at all costs breed a general climate of lawlessness.

With yields varying from three gallons to 25 barrels per day, the competition for the best wells is fierce. Add to this the fuel of alcohol, illegal drugs and prostitution, and relations among drillers soon turn truly combustible.

“There are lots of problems here. When tensions arise between rivals, they often lead to knife fights,” said U Thaw Zin, an oil driller in Htankai. “But if you mind your own business, it’s not so bad.”

For most, in fact, the money to be made here is not worth fighting over. “Drillers like us only make an average of 10,000 kyat [$10] a day. The only ones who are getting really rich from this business are the owners of the buying centers,” said U Min Latt, a driller from neighboring Mandalay Region.

With a daily output of at least 100 barrels, there certainly is money to be made by those who trade in the contraband crude, which is shipped by highway or waterway to the refineries of Monywa, Sagaing Region.

Fortunately for the petrol smugglers, there doesn’t seem to be much interest

in cracking down on their activities. Trucks carrying oil drive right past the MOGE office in Htankai en route to Monywa, but are rarely if ever stopped.

“We see them every day, but we don’t have the right to arrest them. That’s the job of law enforcement,” said one MOGE official in Htankai, speaking on condition of anonymity.

The drillers, however, have not been so lucky in their dealings with the authorities.

“About 70 policemen came and shouted at us to get out of the field,” said U Aye Chan, an oil driller, recalling a recent incident. “They said we face up to five years in prison if we don’t stop. But we have invested a lot to do this— some of us have even sold our farms and houses so we could do business here. Our lives would be ruined if we couldn’t work here.”

Although appeals to higher authorities, including the president and the chief minister of Magway Region, have enabled the drillers to continue, the precariousness of the situation—and diminishing yields—have convinced many that they’re better off elsewhere.

“Oil production has significantly dropped, so some drillers are now leaving the area,” confirmed U Htun Myint, a resident of Htankai.

Meanwhile, just a few dozen miles away, the MOGE has licensed a private company to explore another oilfield where the long-term outlook is very different.

Drillers who want to work the Ya Naung Mone field can do so by making a deal with the landowners, and the oil company buys the crude at close to market value. According to one trader, this arrangement works far better than the free-for-all at Htankai, even if it does mean that drillers and traders have to pay taxes.

“To be honest, we’d rather pay taxes than give bribes all the time,” he said. “It’s better to drill legally than to keep wasting money on corruption.”

Helping Myanmar to bridge distance

Network Design

• Network Architecture, Optimum path from 2G/3G to LTE

• RF Planning

• Spectrum Re-farming

• RAN Network Design, Capacity Planning, Network Dimensioning

• Core Network Design

Network Optimization

• LTE Optimization

• 2G/3G Optimization / Cluster Optimization

• End-to-end Optimization

Consulting Services

• We provide business consulting services, Network Architecture options analysis, migration towards new technologies (LTE, IMS), optimized path from 2G/3G to LTE We provide consulting engineering servies

Network Performance Management

System Integration

Test Activities

Network Troubleshooting

Network Tracing

• We provide turnkey engineering services (design, optimization)

Tools

• SPT Telecommunication is versatile in the use of multiple tools, or tools that fits customer’s preference.

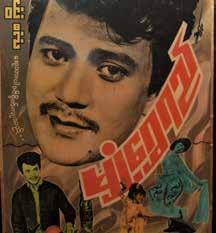

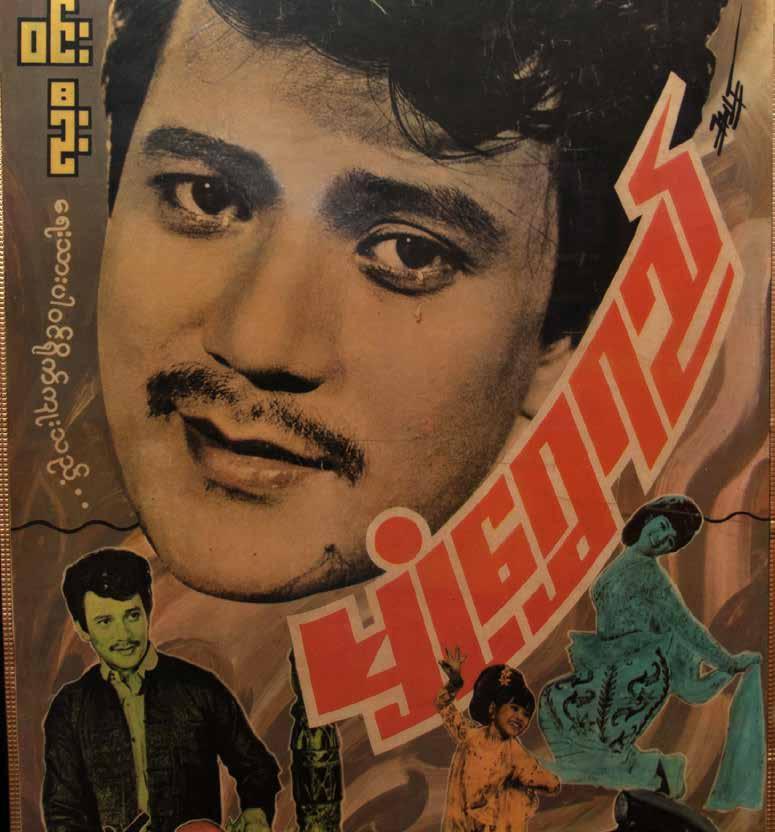

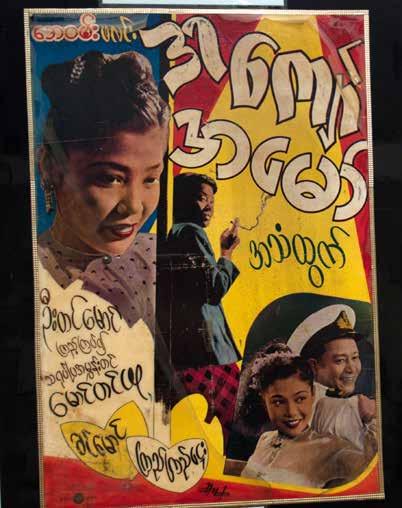

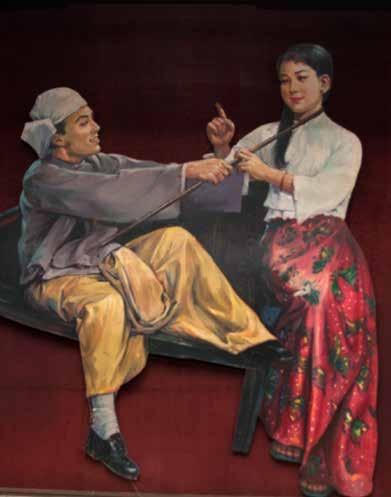

Movie star Winnie, center, with Kyaw Pe and Ye Myint in a 1950s movie directed by U Aung Gyi which clearly looked to Hollyood for inspiration.

Movie star Winnie, center, with Kyaw Pe and Ye Myint in a 1950s movie directed by U Aung Gyi which clearly looked to Hollyood for inspiration.

More than 80 years after the funeral of a leading politician of the pre-independence era became the subject of Myanmar’s first foray into the world of the cinema, the country’s once illustrious film industry is dying a slow death of its own, say industry insiders.

Captured with a second-hand camera, the footage of the funeral of U Tun Shein, an early campaigner for Myanmar’s independence from British colonial rule, set the stage for a proud cinematic tradition that survived both the political upheavals of the twenties and thirties and the devastation of WWII, but never quite recovered from the policies of the socialist era.

The golden age of Myanmar cinema lasted from the 1950s to the 1970s, when local filmmakers produced more than 80 movies a year. But as poverty and political repression deepened in the decades that followed, the number of films that were made declined steadily. Today, despite some improvement in the political and economic climate, the country produces barely a dozen films each year.

Meanwhile, movie theaters are disappearing fast. Many once-famous cinemas in Yangon are now construction sites, while elsewhere in the country, would-be moviegoers have long since lost the venues that in the past offered them an escape from their everyday lives.

“According to our data, there are only around 20 cinemas left in the country,” said U Lu Min, the chairman of the Myanmar Motion Picture Organization (MMPO). “In my hometown of Aungban, in southern Shan State, there is no cinema now.”

Until the 1980s, there were hundreds of movie theaters in Myanmar. But the nationalization in the mid-1960s of all forms of media, including movie production, eventually began to take its toll on the country’s filmmakers, who were increasingly pressed into service as propagandists. Like the movie houses that screened them, movies had become state property.

Although Myanmar officially abandoned socialism in 1988, the military regime that seized power that year continued to exercise strict control over the media and retained ownership of state properties such as movie theaters. Before it handed over power to the current quasi-civilian government in 2011, it sold off some of this property to cronies, but even now, most of the remaining movie theaters are publicly owned.

As the owner of most of the country’s cinemas, the government has until recently shown little interest in making them more attractive to investors.

“For the past 10 years, the government limited leases on cinemas to one year,” said U Lu Min. “But that wasn’t long enough for businessmen to recover their initial investment, so now it has been extended to five years.”

But while this move has helped the established theater operators—notably the Mingalar Group, which runs three of the most famous cinemas in Yangon, the Thamada, Mingalar and Thwin—it has so far not brought in any new investment.

Meanwhile, as technology changes, the cost of transforming one of Yangon’s old-school cinemas into a modern movie theater has become prohibitively expensive. According to U Lu Min, who says the MMPO and the government have both urged cinema operators to switch from analogue to digital projection systems, bringing in new equipment would cost at least 300 million kyat (US$300,000).

“When cinema operators do a cost-benefit analysis, they just decide it’s not worth it. That’s why most are shutting down,” said U Lu Min. “In Southeast Asia, Myanmar now has fewer movie theaters than any other country. Thailand alone has more than 800.”

This dearth of theaters means that new films now have to wait at least a year before being screened, dampening filmmakers’ enthusiasm for taking on new projects.

• 1920: The first silent film, “Myitta Nit Thuyar” (“Love and Liquor”), is shown at Yangon’s Cinema de Paris.

• 1932: “Ngwe Pay Lo Maya” (“It Can’t Be Paid with Money”), the first “talky,” is directed by Toke Kyi in Bombay, India, and shown in Myanmar (then Burma).

• Early 1930s: Movie director Sunny, also known as “Parrot U Sunny,” made films that highlighted social issues such as gambling and police corruption. British authorities censored his movies.

• 1936: Sonny’s “Dou Daung Lan” (“Our Peacock Flag”) is banned.

• 1937: Director Tin Maung of the A1 studio makes “Aung Thapyay” (“The Triumph of Thapy-

“On average, it costs about 100 million kyat [US$100,000] to make a movie here, or double that if we shoot on location overseas. But with audiences shrinking the way they are, we can barely break even, much less make a profit,” said film producer Daw Aye Aye Win, whose Lucky Seven Film and Video Production Company accounts for nearly half of Myanmar’s current cinematic output.

“As a rule, movies are screened for just three weeks here. How can we recover our investment in such a short time? This is why so few movies are being made these days,” she added.

“If the film doesn’t attract big audiences, it may not even get three weeks—it could be dropped and replaced with a foreign film.”

Ironically, the production companies’ efforts to hold onto audiences may only be making matters worse. Critics say that by relying too heavily on tried-and-true formulas and popular genres such as comedies—which account for two-thirds of the movies now made in Myanmar—the local industry has lost much of its appeal.

“It’s no mystery why this industry is declining. People are just not that interested in comedies

ay”), which dealt with the final days of King Thibaw, Myanmar’s last monarch. The colonial government did not allow the movie to play at theaters.

• 1937: Student leader U Nu, who later became prime minister, codirects “Boycott,” a film about the student-led struggle for independence. Another student leader, Aung San, acted in some scenes.

• Post-1948: After the country regained independence in 1948, filmmaking found a new range of themes. With Yangon on the defensive from a communist insurgency and various ethnic rebellions, the industry and its stars were asked to play a role in unifying the nation.

• 1949: When Yangon was under siege by Kayin rebels, directors

POSTER IMAGE FROM THE MYANMAR MOTION PICTURE MUSEUM.

PHOTO: SAI SAW / THE IRRAWADDY PHOTO: SAI SAW / THE IRRAWADDY

POSTER IMAGE FROM THE MYANMAR MOTION PICTURE MUSEUM.

PHOTO: SAI SAW / THE IRRAWADDY PHOTO: SAI SAW / THE IRRAWADDY

these days. The stories are almost all the same, the acting is bad and production values are really poor,” said Daw Ei Phyu Aung, the chief editor of the entertainment journal Sunday.

Foreign films offer much better value for money, she added.

“If you want to go see a movie these days, it will cost you about 10,000 kyat per person by the time you pay for a ticket, transportation and snacks. For that kind of money, most people would rather watch a Korean film.”

Even U Lu Min conceded that quality is an issue that needs to be addressed if the Myanmar film industry is to turn itself around.

“I agree that the quality of Myanmar films is falling,” he said. “There are many reasons for this, including the lack of cinemas, producers cutting costs, people having other options for entertainment. Poor film quality isn’t the only reason the industry is in decline.”

Despite the steady pressure on the film industry, however, U Lu Min said he expects this year and next to buck the trend toward fewer movies (only 15 were produced in 2013, down from 17 the year before).

Although he was not specific about what he based his confidence on, he did offer one source of hope: “I want our president to promote our industry as Obama has supported Hollywood.”

rushed to document the battle for Insein. On the propaganda front, famous movie stars prepared refreshments and hauled rations for the troops.

• 1950s: The rise of communism and the Cold War in the region impacts Myanmar’s film industry. Following the Chinese Kuomintang invasion of northeastern Myanmar in the 1950s, “Pa Le Myat Ye” (“Tear of Pearl”) is produced. The movie denounced imperialism and called for unity within the country. It also stressed the importance of the Tatmadaw, or armed forces.

• 1950s: Love stories, historical films, thrillers and stories dealing with the occult and the supernatural were popular during this period, which became the heyday of mov-

iemaking in the country. Perhaps 80 movies were released each year between 1950 and 1960.

• 1952: Myanmar inaugurates its own Academy Awards ceremony, modeled on the Hollywood version.

• 1962: After Ne Win’s coup, the motion picture industry was told to “march to the Burmese Way to Socialism.” The cinema halls and production houses were nationalized. Scripts were intensely scrutinized by censors before production was even approved. Movies were required to emphasize the struggles of workers and peasants much more strongly. The movie sector, as with the economy in general, went into reverse.

• 1989: From this year, a new government economic policy aimed

at opening up the economy was gradually implemented. Cinemas were sold off to the private sector while new film production houses opened for business.

• Mid-1990s: During this period a private company, Mingalar Ltd, took over operation of most of Yangon’s and Mandalay’s best cinemas. Films continued to be heavily censored and support was given to junta favorites while others were excluded from working in the industry.

• 2011: Pre-censorship ended, but freedom has not brought quality –yet.

Timeline adapted in part from a story titled “Celluloid Disillusions,” by Aung Zaw (available online).

Myanmar’s long isolation means it probably still has more original, stand-alone movie theaters than its immediate neighbors in Southeast Asia.

Many of these buildings that have provided a home for popular culture for decades could be worth preserving.

The Yangon Heritage Trust has singled out the Waziya theater in downtown Yangon as especially worthy of conservation. It is working with the Myanmar Motion Picture Organization (MMPO) to look into preserving the building’s architecture and finding viable new entertainment uses for the space.

Interesting old theaters are still found around the country in locations from Mandalay to Taunggyi to Bago and Pyay. Some have been documented by Phil Joblan in a fascinating blog called the Southeast Asian Theater Project (seatheaterblogspot.com)

The Thwin Theater on Bogyoke Aung San Street in Yangon

The Thwin Theater on Bogyoke Aung San Street in Yangon

The mainstream movie business may be in the doldrums right now, but history says that there is always a market for good stories that are well told.

It’s likely just a matter of time in Myanmar before ways are found to get quality productions made that match rising audience expectations.

Signs of fresh energy to make films offering substantial fare are already emerging aplenty.

So far, perhaps unsurprisingly, many of the most interesting ideas appear to be coming from outside the mainstream.

Just one recent example is Myanmar-born director Midi, who has generated international attention with his 2014 movie “Ice Poison,” about a young farmer in Shan State who becomes involved in drugs.

The film has shown in at least eight festivals internationally since it was made, but will reportedly only be seen in this country on DVD or online, as the director did not have a permit to shoot it.

Taiwan-based Midi plans to follow it up next year with a love story, “The Road to Mandalay,” which will be shot in a border refugee camp and Bangkok.

Another director tackling substantive themes is Aung Ko Latt, who garnered attention last year for his movie “Kayan Beauties,” which also explores vulnerable lives in Myanmar’s ethnic areas.

“Kayan Beauties” won a Special Jury Award at the Asean International Film Festival in Malaysia last year, and is still gaining new audiences; this May, it showed at the Soho International Festival in New York City.

“For 27 years I’ve been trying to show off our Burmese films and movies to the world. Now, that dream has come true. I’ll try my best to produce more Burmese films and movies reflecting the beauty of our country, traditions and cultures,” the director told The Irrawaddy last year.

Documentary-making in particular is experiencing a resurgence in the post-censorship era, boosted in part by

events like the Wathann annual film festival in Yangon, which started in 2011.

And documentary-makers too are increasingly reaching audiences abroad as well as at home.

In May, for example, the Yangon Film School announced that U Aung Nwai Htway’s personal, behind-the-scenes story of his famous movie-star parents, “Behind the Screen,” will show at the International Documentary Film Festival in Hanoi this month.

The film won Best Asean Documentary at the Salaya International Documentary Film Festival in Salaya, Thailand, in March.

Also in May, a selection of films from last year’s Wathann festival showed in Shanghai, China.

Perhaps, after years of repression, Myanmar’s creative film-makers are just starting to hit their stride again; if so, that happy ending for the country’s long love affair with movies may be within reach.

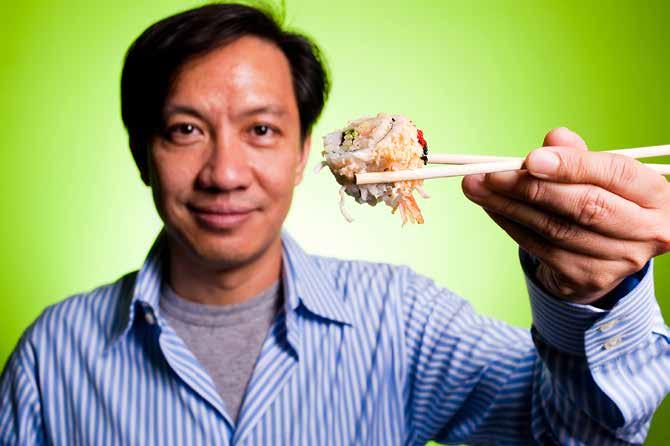

A scene from 'Ice Poison' shot in LashioIn 1989, Philip Maung arrived in the United States from Myanmar with just $13 in his pocket and a dream of making a new life. Today, he is the CEO of Hissho Sushi, a leading company in the US supermarket sushi industry. After spending years learning every facet of the sushi business, he and his wife took the plunge in 1998, pooling their finances to found the business in their family dining room. The Irrawaddy’s Kyaw Hsu Mon spoke with him recently about his company’s history and where he plans to take it from here.

What did you do in Myanmar before you left for the United States?

I was a student and helping out with my parents' business.

Where and when did you start your sushi business? And what is the meaning of the name?

We started out in Charlotte, North Carolina, in April 1998. “Hissho” is a Japanese word that means “certain victory.”

What did you study in Myanmar?

I went to medical school first and later somehow ended up as a chemistry major. However, I dropped out of chemistry in my final year. I guess it wasn’t my destiny to become a doctor. I’ve always wanted to help people, and now I can help many by providing jobs. Most of my employees and franchise owners are Burmese.

How many sushi shops do you have now, and how many people do they employ?

Hissho currently has over 500 locations in 34 states. Since we are a franchise company, not everyone [who works for

Hissho] is our employee. But of those that are, the total is approximately 500.

What is the hardest part of this business? And why did you decide to start a sushi company?

Starting a business is always difficult if you’re trying to do it without sufficient capital. I could not get any bank loans because I had no collateral, and no track record. Maintaining cash flow is always a challenge, but at least I can say now that the banks come to me. I opened up Hissho because I learned how the business operated and truly believed I could do it better.

How much did you have to start off with?

Hissho was started on a shoestring with money borrowed from credit cards, my meager savings, and loans from my family. I started with virtually nothing, and we’ll make more than US$60 million in revenue this year.

How has sushi culture developed in the US?

The sushi culture continues to grow with innovative and delicious “Westernized” creations and we are constantly doing research and development to find new ideas. The public is becoming more familiar with it and the young children are our target market. They love the colors, the textures, and healthy products. The kids are the ones that often drag their parents to buy sushi for them, and in turn learning more about it themselves. But educating the public is an ongoing process as many still think sushi is raw fish.

Who are your biggest customers?

We have recently started opening businesses on college and university campuses and have enjoyed tremendous success, and have plans to open even more.

Who are your major competitors?

We have many competitors, some large, some small, but since we believe

in consistency of product and service, and are always striving to improve, and believe that every single customer should be a friend for life, we continue to grow at a steady pace. We are interested in quality, not quantity.

How do you maintain the quality of your sushi?

We continue to use the very best ingredients available on the market with emphasis on sustainability. We train our chefs at our headquarters in Charlotte, and maintain very high standards of customer service, innovative sushi rolls, hot bars, new concepts, and always put the customer first.

Please tell me about your meeting with US President Obama.

I was invited by First Lady Michelle Obama to visit the White House, and to attend the President’s Address

to Congress. President Obama was touting the success of small businesses and how it was these entities that were helping America get back on its feet after the recession of 2008.

The impact of my being there, and even being seated on the first row of the Gallery next to the First Lady, resound even to this day. The effect was immediate in that I was interviewed by all the major media concerns in the US, and from the media all over Asia.

The attention was something I’d never experienced before, and is humbling for me. Growing up poor in Burma does not prepare anyone to one day be in the presence of the President and First Lady of the United States.

Do you have plans to expand your business to Myanmar?

There are no plans to do so at this time,

but hopefully, one day, this will become a reality.

What do you think are the main challenges facing foreign businesspeople interested in investing in Myanmar?

The infrastructure is the biggest obstacle, and lack of skilled workers is a big challenge. Logistics would also be a challenge that ties into infrastructure.

Have you ever thought about what your life might have been like if you hadn’t left Myanmar?

Of course I’ve thought about this, but I didn’t dwell on it because of my entrepreneurial spirit. I can’t imagine how I would’ve ended up if I hadn’t come to the US. Maybe I would be selling something on the street, or in Yuzana Plaza, or opening fashion shops.

Myanmar’s government is planning to offer up contracts to expand and operate some 39 regional airports in the country later this year, but some doubt whether the private sector will bring the help needed to update the country’s crumbling smaller airstrips.

When a major aviation conference was held in Yangon in March, officials

from the Department of Civil Aviation (DCA) told interested businesspeople that they have a plan—the details of which were sparse—that will return Myanmar to its once-proud place as a regional aviation hub.

The Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) is currently working on a “survey,” which will feed into a government transport master plan, but a JICA spokesperson declined to

go into detail about the plan. Japan last year initiated a US$12 million project to upgrade safety at the country’s six biggest airports with new communications and navigation equipment.

But in terms of tangible policy, it is clear only that Myanmar will continue offering up parts of the sector in competitive tenders. According to the DCA, as the clouds disperse at the end of the current rainy season,

the latest tender will go out asking for companies to invest in improving airports and operate them as publicprivate partnerships.

The airports include those serving growing tourist destinations, like Heho near Inle Lake, Nyaung-U at Bagan, and Thandwe near Ngapali beach, but also planned economic hubs like Kyaukphyu and Dawei.

The aim is to modernize and improve the safety record of the large network of airports as it deals with rising passenger numbers. That should facilitate business and tourist travel across Myanmar’s vast distances, which would in theory help spread economic growth around.

Henrich Dahm, a Yangonbased analyst who specializes in the tourism sector, told The Irrawaddy that developing some of the regional airports was needed for the tourism industry to handle the increasing numbers of visitors wanting to see more than just the major cities.

It was only in 2012 that Myanmar surpassed 1 million tourists per year, but President U Thein Sein has predicted that the country could get 5 million foreign visitors next year.

“The development of regional airports is important to ease the overstretched tourism infrastructure and address the lack of airport capacity in Yangon,” Mr. Dahm said.

“More tourists need to [be able to] fly directly to Bagan, Inle, Mandalay, Myeik, etc., to promote new destinations in the country.”

The tender follows the awarding of deals to operate the Yangon International Airport and Mandalay’s airport, given to a subsidiary of Myanmar-owned company Asia World and Japan’s Mitsubishi Corporation, respectively.

The model of private operators taking over airports has had success elsewhere, and has been useful for governments short on capital who wish to expand their aviation infrastructure.

However, the private sector is not always willing to stump up all the cash for such projects, as the government has discovered with the tender to build a new airport serving Yangon. A new tender had to be issued for the Hanthawaddy airport project after South Korea’s Incheon and the DCA could not agree on how it would be funded. The government eventually agreed to guarantee development loans for half of the project cost—estimated at between $1.4 and $1.5 billion.

In other sectors, the government has had considerable success bringing in private money to pay for upgrades in infrastructure.

Peter Brimble, the Asian Development Bank’s (ADB) principal country specialist based in Yangon, said the tender for telecommunications licenses last year was widely seen as competitive and fair and secured promises of large upfront capital investment.

The ADB has just begun a program in

the energy sector to help the government develop a robust tendering process to make sure future deals get the best outcome for Myanmar. “It’s not just to go through the process of tendering, it’s also to think about the national needs— whether that means using a publicprivate partnership or the government’s own money or a partnership [with donors],” said Mr. Brimble.

The government’s preferred choice, though, as demonstrated by the stumbling Hanthawaddy project, has been to ask private firms to take the entire hit, in exchange for rewards later as long-term operators.

“There’s a tendency to try to raise funds however you can,” Mr. Brimble said.

The DCA appears confident that there is enough private-sector interest, and the department’s director general U Tin Naing Tun told The Irrawaddy in April that “many” companies had come forward to register their interest.

However, he said that much of

that interest was from local firms, and it is unclear whether the investment necessary to revamp the domestic aviation market will be forthcoming.

A 2012 report by Business Monitor International, looking ahead to the development of Myanmar aviation, threw cold water on the idea that the sector offered attractive investment opportunities.

“We do not see a lot of financially viable opportunities in the construction and management of airports in Myanmar over the next decade,” the report said.

Noting that Myanmar already has a large number of airports in operation—69 in total—the report warned that “even though Myanmar is keen on private investment…the rewards from this sector are very uncertain for the next decade and would depend on several long-term factors such as a general rise in incomes within Myanmar and the development of a vibrant tourism sector.”

Economist and country specialist Sean Turnell said the airports at tourist destinations had potential, particularly considering the growth of low-cost carriers in the region, which could take advantage of “secondary” airports that are cheaper for airlines to fly into.

“Many others will not be attractive, though—too out of the way, no viable tourist traffic and no reservoir of middleclass travelers or business activity to sustain them,” Mr. Turnell said.

“The sort of returns these airports could generate would not be sufficient for the relatively high capital outlays creating a modern airport would require.

“Of course, on top of the possibility of low and variable returns, you have that fundamental problem in Myanmar of the absence of secure property rights. Investing in an airport will be a long-term proposition, with all the insecurities such decision-making may involve,” Mr. Turnell added.

Corruption, access to skilled labor and technology are the biggest concerns for businesses operating in Myanmar, according to the results of a UN-led survey released in May.

The survey— conducted by the United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development and the Union of Myanmar Federation of Chambers of Commerce and Industry—questioned more than 3,000 firms about the problems associated with doing business in a reforming Myanmar.

“[T]he survey suggests the reforms have thus far had only a limited impact on corruption,” the report said, explaining that about 20 percent of the companies said corruption was a “very severe obstacle.”

“Access to skilled labor and technology were identified as the second and third biggest obstacles,” it said. “Sixty percent of the firms surveyed said they had to pay bribes for registration, licenses or permits. About half the firms said they paid $500 in extra fees while about a dozen said extra fees exceeded $10,000.”

The Myanmar government passed an anti-corruption law last year, and a new anti-graft commission was established in February. But the measures, aimed at tackling the endemic corruption that grew over years of secretive military rule, do not appear to have begun taking effect, and the new commission has already faced criticism since it is made up overwhelmingly of former soldiers.

Transparency International’s latest Corruption Perceptions Index, published in December, ranked Myanmar 157 out of 177 countries, a marked improvement on the ranking of 172 out of 176 in 2012. –

Simon LewisA new government agency has been created to promote Myanmar’s exports.

Known as MyanTrade, the body will operate under the wing of the Ministry of Commerce, according to Commerce Minister U Win Myint.

Much of Myanmar’s export trade has in recent years been raw agricultural produce such

Hong Kong clothing manufacturers will move their factory production to Myanmar because wages here are only 20 percent of rates in China, an industry report said.

More than 10 Hong Kong-based firms are planning to relocate to the Thilawa Special Economic Zone because costs have become too high in China.

“Hong Kong clothing firms participating in the apparel park aim to benefit from the low cost of production in [Myanmar] as the cost of labor is only about 20 percent of the wages in China,” said the website fibre2fashion.

“Hong Kong entrepreneurs also expect to benefit from the duty-free access enjoyed by Myanmar while exporting to the [European Union].”

The Thilawa factories could be operational by the end of 2015 and employ up to 30,000 people, said the Associated Press.

Myanmar has “immense potential” to regain its former glory as a leading international garment producer and exporter, Business Monitor International (BMI) said in April.

But a revival will be from a low base, it said, because other countries such as Vietnam and Cambodia had attracted investment during Myanmar’s years of isolation. Myanmar garment exports in 2012 were valued at US$909 million but that was only 1.5 percent of GDP, said BMI. –William

Bootas rice, pulses, timber and fish, plus natural gas, but as more investment goes into manufacturing MyanTrade will help guide products into the export market, the report said. Although exports have grown in the last two years, Myanmar imports more goods than it sends abroad. –William

BootLeading UK-based law firm Allen & Overy (A&O) has become the latest international law firm to set up an office in Myanmar.

As the Myanmar government undertakes political and economic reforms, and foreign investors are invited in, a number of law firms have moved into the commercial capital, Yangon, to advise companies doing business in the country.

According to thelawyer. com, a British website for legal professionals, A&O has had lawyers based in Myanmar for some time, but has only recently opened an office in Yangon.

“A&O’s Yangon office provides international legal services and will not practice Myanmar law,” the report said.

“The new office is managed by Bangkok managing partner Simon Makinson and currently has two associates and two support staff.”

It said A&O—which is one of the “magic circle” of top London law firms—has already worked with Telenor, the Norwegian telecommunications firm.

A number of foreign law firms, including Singapore’s Kelvin Chia Partnership, American firm Herzfeld, Rubin, Meyer & Rose, DFDL and VDB-Loi are already operating in Yangon. US-based Baker & McKenzie opened its Yangon office in February and Duane Morris, also from the US, announced in September last year it had moved into the city.

–Simon LewisMassive cement firm Semen Indonesia has agreed to buy a stake in a Myanmarbased cement company, according to the Jakarta Globe newspaper.

A news report on May 7 said the company was taking the minority share in an unnamed Myanmar company. Semen Indonesia has previously said it plans to spend US$200 million in Myanmar.

The report quoted Semen’s President Director Dwi Soetjipto saying the company would take a 30 percent stake in the Myanmar company.

“The deal is valued at roughly $30 million,’’ Dwi added.

In March, Thailand’s Siam Cement Group said it was investing $400 million in a cement plant in Myanmar, set to be operationak in 2016. –Simon Lewis

An over 620-mile journey that begins in Thailand, cuts through Cambodia and ends in Ho Chi Minh City has become, for obvious reasons, the route of choice for Thai truckers shipping cargo to that city in southern Vietnam. But despite the ostensible convenience of this overland run, Thai transport companies are not tooting their praises for improvements in road conditions in neighboring countries; nor are they expressing much enthusiasm for the prospect of increased regional connectivity and cross-border trade.