TheIrrawaddy

A landmark international exhibition showcases art of exceptional beauty from Myanmar and Southeast Asia

The Irrawaddy magazine has covered Myanmar, its neighbors and Southeast Asia since 1993.

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF: Aung Zaw

EDITOR (English Edition): Kyaw Zwa Moe

ASSOCIATE EDITOR: Sandy Barron

COPY DESK: Neil Lawrence, Paul Vrieze, Samantha Michaels, Andrew D. Kaspar, Simon Lewis

CONTRIBUTORS to this issue: Aung Zaw; Kyaw Zwa Moe; Kyaw Phyo Tha; Simon Lewis; Bertil Lintner; Zarni Mann; Dani Patteran; Kyaw Hsu Mon; Grace Harrison; Marwaan Macan-Markar; Nora Swe; Sanay Lin.

PHOTOGRAPHERS : JPaing; Sai Zaw.

LAYOUT DESIGNER: Banjong Banriankit

SENIOR MANAGER : Win Thu (Regional Office)

MANAGER: Phyo Thu Htet (Yangon Bureau)

REGIONAL HEADQUARTERS MAILING ADDRESS: The Irrawaddy, P.O. Box 242, CMU Post Office, Chiang Mai 50200, Thailand.

YANGON BUREAU : No. 197, 2nd Floor, 32nd Street (Upper Block), Pabedan Township, Yangon, Myanmar. TEL: 01 388521, 01 389762

EMAIL: editors@irrawaddy.org

SALES&ADVERTISING: advertising@irrawaddy.org

SUBSCRIPTIONS: subscriptions@irrawaddy.org

PRINTER: Chotana Printing (Chiang Mai, Thailand)

PUBLISHER LICENSE : 13215047701213

16 | Culture: A Murky Story

The legend of the lost Dhammazedi Bell has long chimed with dreamers and schemers alike

20 | Politics: A ‘Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement’–for What?

Is Myanmar’s military laying the groundwork for peace, or setting the stage for an assault on its most formidable enemy?

22 | COVER Myanmar's Moment

Ancient treasures travel to New York for a cultural ‘coming out’

31 | Interview: Ready for a Rice Renaissance?

34 | Border Trade: From Smugglers’ Paradise to Free Trade Gateway

Myawaddy gets ready to shed its image as a backdoor into Myanmar’s black markets and become a regional trade hub

38 | Interview: US Ex-Im Bank's Patricia Loui

40 | Signposts: Growth Forecast

42 | Lao Dam Troubles Mekong Waters

Regional efforts to protect Southeast Asia’s most important waterway suffer a blow

What is The Elders’ role in Myanmar’s peace process?

Gro Harlem Bruntland (former Norwegian prime minister): Our impression is that they, both the government and the leadership across the border, are willing to meet us, which is important. We are grateful for that, which is why we can come back and continue a dialogue and discussion with them. We are not mediators. We want to have a supporting role, getting to know key people in the process and encourage the process.

How would you evaluate your meeting with President U Thein Sein and the military’s commander-in-chief, Snr.-Gen. Min Aung Hlaing, in Naypyitaw?

GHB: The main points are they are working to promote the peace, to get ceasefires and to start the political dialogue and to deal with the constitutional questions. They are expressing this in a positive way as their intentions, as you can imagine. We hear all the voices when we meet the number of other groups who are experiencing conflicts, who are not happy, who feel things are too slow and who don’t trust.

We get the picture there are considerable distances between different parties to this conflict, that there are problems to be overcome. Also compared to their intentions and their hopes we heard half a year ago, things are going slowly, as you know. The chief peace negotiator [Minister U Aung Min], who we also met twice, [hoped for a quick peace process], which has not been fulfilled. We can observe there is much to be overcome and a lot of issues that need to be addressed in the political dialogue, because there are no clear solutions to many of the issues.

The Elders, a group of independent world leaders, have traveled to Myanmar twice in less than a year. On their latest trip, two members of the group talked to reporters Nyein Nyein and Lin Thant about prospects for peace.

Martti Ahtisaari (former president of Finland and Nobel Peace laureate): We have been involved with conflicts all over the world. I don’t think the conflict in Myanmar is any different from those in a sense. There is enormous mistrust. Yet it is a natural thing and it takes a long time before people can overcome mistrust. You sit and you talk, and the dialogue hopefully is inclusive in a [way] that people can feel they have a chance to express what they think. Perhaps some of their views can be taken into consideration in the peace process. But the important thing is to encourage people to move forward now.

Myanmar’s military is a key player in the peace process, but in reality, it is still fighting in Shan and Kachin states, and in other areas. Did you discuss this issue with Snr.-Gen. Min Aung Hlaing?

GHB: We have asked questions. In fact there still are conflicts going on. He [Snr.-Gen. Min Aung Hlaing] explained [that there was less fighting in March] than in January and February. Again, it may be moving in the right direction, although there is no stopping of every conflict yet. And there is not really a fully agreed ceasefire, either. So it illustrates the need to get to the point of ceasefire, so that people can get peace and feel confident in their own areas. It is not easy to have political dialogue when shooting is happening. This is

again an argument: It is important to get to a ceasefire so we can avoid these kinds of incidents, which create uncertainty, fear in the people.

You also visited a camp for internally displaced persons in Myitkyina, Kachin State, and a refugee camp on the MyanmarThai border. How would you describe the situation in these places, and what should the international community be doing about it?

GHB: We will urge and encourage a more inclusive process, to listen to the different groups. [It is also important to] think about the importance of expertise and training in health and education in the border areas, so that that the capacity there does not get lost, but is used and incorporated into a future peace situation. As the chief minister in Kachin State explained, health and education are crucial. [There is also] conflict about the use of natural resources and human rights issues. But development means [that] you invest in the people of your country, so they are healthy and educated.

MA: We have both visited many camps in our lifetimes, and we were impressed by both camps we visited [on this trip]. They were well run and people were very professional and hardworking. You can always tell when you see children;

they cannot act. It is always nice when you walk around and see smiles on their faces. We felt very comfortable with the sort of professionalism we saw there. It is important that we encourage the international community to continue its assistance, because the conflict is not yet over.

GHB: It illustrates also that there is human capacity built in those clinics [like the Mae Tao clinic in Mae Sot, Thailand] and those camps. They are valuable to the future of Myanmar and should be taken care of, should be used.

What would be your suggestion to solve Myanmar’s conflicts and the problems it is facing in its transition to democracy?

GHB: I think, as I said before, more inclusiveness, listening to all the different ethnic and other groups in such a way that political dialogue can be real and include all the needs and points of view. Inclusiveness is necessary.

MA: There has not been that much dialogue, as conflict has been raging for decades. So it is not easy to move from that to an inclusive process. We know from all over the world that [inclusiveness] is the best medicine at this stage, but it is very demanding and not an easy process, because people—governments particularly— were not inclusive in the past. They have different behaviors and patterns. To change that it is a challenge. We need wisdom, both wise men and women, now on all sides; common wisdom in the society. We have met some very wise individuals. It is our task to help them and try to encourage them and recognize them at the same time. To overcome the mistrust, it takes time.

—Shawn Crispin of the Committee to Protect Journalists, speaking on the recent jailing of reporters in Myanmar

—The China Business News, on the plunge in Chinese investment in Myanmar in 2013 to just 5 percent of the figure for the previous year

—Actor Colin Firth talking about his role in the upcoming movie "The Railway Man" about the infamous Death Railway built between Thailand and Myanmar during WWII.

“Every so often you’re called to interpret a story which is very, very precious.”

“The rules of the game in [Myanmar] have changed.”

“Let’s restrain our speech not to spread hate among people.”

—The slogan for the “Panzagar” (flower speech) movement, a new campaign against hate speech led by blogger Nay Phone Latt

“The [government’s] once-promising democratic reform program is rapidly being reversed.”

In late April, Myanmar’s democracy movement began a period of mourning over the loss of one of its greatest leaders.

U Win Tin, a prominent journalist who became Myanmar's longest-serving political prisoner after challenging military rule by co-founding the National League for Democracy (NLD), died of renal failure on April 21 at the age of 85.

A feisty former newspaper editor, U Win Tin was a close aide to opposition leader Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, another founder in 1988 of the prodemocracy party. In 1989, she was put under house arrest and U Win Tin was

sent to prison for his political activities.

Freed after 19 years behind bars in 2008, he continued working with the NLD through the country’s transition from military rule to an elected— though army-dominated— government in 2011.

He also started a foundation to give assistance to current and former political prisoners.

As his supporters in Myanmar and abroad heard the news of his passing, many spoke of U Win Tin as a man of extraordinary courage and integrity whose steadfast adherence to his principles inspired countless others.

May he rest in peace.

Protesting Myanmar migrant workers in Mae Sot, Thailand, returned to work on April 3 at the Yuan Jiao Garment factory after successful negotiations ended a more than weeklong strike. More than 500 workers had walked off the job demanding a wage increase and better benefits, including more time off and a sick leave allowance. Under the agreement, the workers, who got only one day off a month, will now be allowed to rest every Sunday and can take a maximum of 30 days sick leave annually. However, wage increases fell short of the workers’ demands,

rising by just 15-20 Thai baht (US$0.50-$0.65) per day from the current level of around 175 baht ($5.50).

A commission established by the Myanmar government to investigate mob attacks on the premises of international aid groups in Sittwe in late March criticized the Rakhine State authorities for their weak response to the incident. The commission also concluded that a foreign aid worker had not mishandled a Buddhist flag, despite rumors to the contrary that sparked large-scale riots on March 26-27, resulting in

destruction of property and the death of a 13-yearold girl. The violence also forced aid groups to leave the volatile state, amid accusations among ethnic Rakhine Buddhists that they had favored Rohingya Muslims in recent tensions between the two communities.

Several private newspapers printed black front pages on April 11 in protest over the sentencing of a reporter to one year in prison for trespassing and interfering with the duties of a civil servant. A court in Magway Region handed down the sentence against Democratic Voice of Burma video

reporter U Zaw Pe on April 7 in connection with an attempt he made to interview an education official in 2012. The sentence was seen by many Myanmar journalists as just the latest sign that the authorities are seeking to rein in press freedom ahead of elections to be held next year. Since the end of last year, at least six journalists have been arrested on criminal charges, such as violating the state secrets act or trespassing. Two have been sentenced to jail while others are in custody awaiting trial.

Myanmar completed its first census since 1983 on April 10 amid fears that the nationwide count of the country’s population would stoke ethnic and religious tensions. Around 100,000 schoolteachers were recruited for the task, with police and military personnel accompanying them in areas where tensions between the authorities and local people were high.

Some ethnic groups objected to the use of an official list of 135 ethnicities in the census, saying that it contained inaccuracies and was unnecessarily divisive. In some cases, armed groups refused to allow enumerators into their territory because of worries that the census would be used for political purposes. There was also international criticism of the government’s decision to bar the use of the term “Rohingya” to designate a Muslim minority living in northern Rakhine State. The census was supported by United Nations Population Fund.

Around 160 villagers who were forcibly evicted from their homes on the outskirts of Yangon were resettled in rebelheld territory in eastern Kayin State in early April, despite attempts by local authorities to prevent the group from relocating there. The displaced families had moved to a village called Kyauk Khet, located in an area controlled by the Democratic Karen Benevolent Army (formerly the Democratic Karen Buddhist Army) near the border town of Myawaddy. In February, about 200 ethnic Kayin villagers from Thameegalay, Innpatee and Pawkali villages in Hlegu Township, Yangon Region, were evicted and their homes were bulldozed by local authorities, who claimed that the impoverished families had been illegally occupying military-owned land.

PHOTO: REUTERS Police officers and national census enumerators walk in a Rohingya village.

Petitioners wait outside the Yangon home of Daw Aung San Suu Kyi on April 5, 2014. According to local media, the petitioners wanted the opposition leader’s help in settling land disputes. They left after waiting for Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, who did not appear, for three hours.

the mid-2000s, her father, Ngun Peng Siakhel, was arrested and sentenced to a week in prison for allowing an unregistered visitor to stay in his home overnight. He was released on bail, but decided then and there that he had had enough of Myanmar’s restrictive and repressive rules.

Deciding that it was time to leave the country for the sake of his family’s future, he travelled to Malaysia. Three years later, when she was six years old, Van Sui Chin and her mother and younger sister were smuggled out of the country to join him.

In 2010, after three years of living in Kuala Lumpur as refugees, the family was resettled in the Czech Republic. Despite the many hardships they had experienced in their young lives, Van Sui Chin and her sister, Sarah Mang Cin Tial, soon distinguished themselves as top students.

By KYAW ZWA MOE / PRAGUE, Czech RepublicTheir story is one shared by hundreds of thousands of families in Myanmar. Driven out of their homeland by poverty, oppressive laws, human rights abuses and discrimination against ethnic minorities, they have been forced to make new lives in foreign countries.

This vast diaspora—the product of half a century of brutal military misrule—has seen millions of Myanmar nationals flee to neighboring countries such as Thailand and India, as well as to other countries around the region and the world.

Van Sui Chin, a teenage girl living in the Czech town of Stara Boleslav, just outside the capital Prague, is an exceptional student. At the middle school where she studies, the 15-yearold consistently comes at the top of her class in almost every subject. She has received several academic awards, and for two consecutive years has been chosen to travel to Italy on excursions with two other very gifted students.

But Van Sui Chin is not Czech. Her family is from Hakha, the capital of Myanmar’s impoverished Chin State.

The story of how she ended up in the Czech Republic is a familiar one. In

Among them, there may be thousands or tens of thousands of students like Van Sui Chin who have benefited from a better education than they could ever dream of receiving at home. This is great for them, but a tragedy for our country, because it means that we have lost so much of our enormous potential to the neglect and misguided policies of the past.

Soon after President U Thein Sein assumed power in 2011 and began introducing reforms, he invited Myanmar citizens living abroad to return and help rebuild the country. Many, including political exiles and well-educated professionals, did come back to see for themselves how much had changed. Most were unimpressed.

The most common complaint I’ve

The government needs to radically rethink its policies on education if it wants the country’s best and brightest to help it build a better future

heard from many of these returnees is that the government continues to exclude them from the reform process. Instead of sugar-coated words, they say, they want to be able to play a clear role in shaping the country’s future.

Unfortunately, it seems that old mindsets among the former military rulers die hard. Rather than embrace well-educated returnees, the authorities prefer to keep them at arm’s length.

This is, no doubt, a legacy of the days when students were seen by the ruling generals as adversaries. Since 1962, when the armed forces first seized power, students have been at the forefront of efforts to restore civilian rule. After 1988, when a nationwide, student-led pro-democracy uprising nearly toppled the former dictatorship, this animosity became even more intense, resulting in the closure of colleges and universities across the country. They were reopened only after new campuses were built far from the city centers.

It seems that at least some in the current government—which consists largely of former generals, including some who were directly or indirectly involved in cracking down on student demonstrations—still regard students and the university-educated with suspicion. This is a shame, because the country desperately needs all the help it can get from its best-qualified citizens.

If U Thein Sein is indeed a reformist, he must do more to eliminate such thinking within his government. And the best place to begin is by seeking out and seriously listening to some muchneeded input on education reform.

Despite calls from academics for bottom-up reforms, the Ministry of Education continues to believe that it must remain firmly in control of any future changes to the education system. But this top-down approach is at odds with what the country really needs—a reform process that includes a variety of stakeholders working together to achieve a greater degree of autonomy in the country’s institutions of learning.

One group that is actively pursuing such changes is the National Network for Education Reform (NNER), which brings together leading voices on

education, including teachers unions, ethnic education groups, independent educational organizations, the 88 Generation Students group, the opposition National League for Democracy’s education network, and Buddhist monks and Christian churches.

The NNER has conducted dozens of seminars across the country since it was formed in 2012, and in June of last year, it held a national conference attended by 1,200 participants. That gathering produced a report with recommendations on how to create an inclusive education system that was submitted to Parliament and a committee overseeing the government’s Comprehensive Education Sector Review.

Despite meeting with Education Ministry officials three times last year, however, the NNER says that the government has so far shown little interest in its ideas on reform.

The problem, according to two active members of the NNER—Dr. Arkar Moe Thu, chairman of the Dagon University Teachers’ Association, and Jimmy Rezar Boi, a director of MustardSeed Myanmar—is that the two sides have fundamentally different ideologies. While the NNER’s

philosophy is to cultivate free thinking, the ministry believes its goal is to produce “right-thinking” students.

“When they talk about ‘right thinking,’ we need to ask how they decide what’s right and what’s wrong,” Jimmy Rezar Boi told me when I met with him and Dr. Arkar Moe Thu recently.

“What we want is an education system that allows academics, teachers and students to think freely on their own and allows them to choose what they want. That is their right,” he added.

When opposition leader Daw Aung San Suu Kyi visited the Czech Republic late last year, she met some Myanmar nationals here, including Van Sui Chin and her sister. The democracy icon told them to study hard so they could contribute to the development of their homeland in the future.

But until the government learns to stop seeing students as a threat, and instead recognizes them as individuals whose minds are the nation’s greatest treasure, Myanmar’s future may not be much better than its past.

Kyaw Zwa Moe is the editor of the English-language edition of The Irrawaddy.

PHOTO: JPAING / THE IRRAWADDY

Kyaw Zwa Moe is the editor of the English-language edition of The Irrawaddy.

PHOTO: JPAING / THE IRRAWADDY

By THE IRRAWADDY

By THE IRRAWADDY

of the armed forces, Snr.-Gen. Min Aung Hlaing, who is due to retire soon. His possible successor, Deputy Snr.-Gen. Soe Win, is also a regular visitor. Two other favorites of the exgeneralissimo who frequently drop by are Gen. Hla Htay Win, the chief of the general staff (army, navy and air force), and Lt.-Gen. Myat Htun Oo; both are also in line for promotion.

The third group includes Union Parliament Speaker U Shwe Mann and Upper House Speaker U Khin Aung Myint. U Shwe Mann, a leading member of the former junta who was pegged to become president in 2011, reportedly had a lengthy conversation with his former boss after President U Thein Sein got the job instead.

In addition to these visitors, there are also others—including the president—who visit during traditional holidays, when it is customary for subordinates to pay their respects to their elders.

To many observers, this steady stream of visitors indicates that the man who once ruled with an iron fist still wields considerable power behind the scenes. His influence is believed to be especially strong with the military, particularly in matters related to promotions and reshuffles.

But there are also those who believe that he is the reason that reforms introduced since 2011 appear to have stalled. He has, they say, decided to slow the pace of change ahead of next year’s election to ensure that the military retains its preeminent position in political affairs.

If there was ever any doubt that Snr.-Gen. Than Shwe, Myanmar’s ex-dictator, is still a force behind the scenes, they can now be put to rest. As sources close to the former junta leadership have confirmed, the retired strongman is as influential as ever, and is likely to remain so until he dies.

According to these sources, three groups regularly visit the aging military patriarch at his palatial residence in Naypyitaw.

The first is led by U Thaung, the former minister for science and technology, and U Aung Thaung, the former industry minister who now plays a leading role in the ruling Union Solidarity and Development Party. Dr. Kyaw Myint, the former health minister, and Dr. Chan Nyein, the former education minister, also belong to this group.

The second group consists of senior military figures, including the current commander-in-chief

Of course, there are some who insist that he and his wife Daw Kyaing Kyaing spend their days watching soap operas and leading “a boring lifestyle” (to quote one source) at their massive residence near the Water Fountain Park in Naypyitaw.

Boring? Perhaps. But make no mistake: This is a man who knows that he can’t afford to get too bored with the shifting sands of power in Myanmar politics. He may have stepped out of public view, but his exit strategy is still a work in progress.

Multi-beam Echo Sounding Survey.”

“3D Seismic Survey.”

“GPR–Ground Penetrating Radar.”

The language in an official method statement proposing the recovery of Myanmar’s famed Dhammazedi Bell owes everything to technology and science.

But this is a story in which star billing goes not to science but to superstition, and a supporting cast of dreamers, schemers and assorted would-be heroes.

Superstitious government leaders are just some of those who believe that the discovery of a bell said to have sunk to the bottom of the Yangon River off Monkey Point more than 400 years ago could be the key to the country’s rise from its current status as one of Asia’s poorest nations.

Believers’ romantic desires to tie the Dhammazedi Bell with the national destiny has resulted in several failed missions over recent decades to reclaim the bell, believed to be one of the biggest in the world.

Hollywood star Richard Gere’s purported interest in the bell was never more than a rumor. But over the years a motley crew of individuals and companies from the United States, Australia, Japan and Singapore has expressed interest in joining a search that for Myanmar Buddhists would be the equivalent of a quest for the Holy Grail.

Non-believers, including former political dissidents, once thundered that any attempt to salvage the bell (reckoned to lie in the mud under 40 feet of water in a strong current),

would only serve to legitimize an illegal military regime.

The former junta, for its part, decreed that only citizens of the country had the right to search for the bell because finding it was a “national issue.”

Why such a frenzy? For answers, we need to look at the bell’s fabled history.

The bell was named after King Dhammazedi, who ruled the Monspeaking Hanthawaddy Kingdom from 1471 to 1492. A devout Buddhist, Dhammazedi had the bell cast in 1490 as a donation to Shwedagon Pagoda, Myanmar’s most sacred shrine. Made from more than 290 tons of copper, gold, silver and tin alloy, it is said to have been more than twice as heavy as the Bell of Good Luck, a Chinese temple bell that at 116 metric tons has held the world record since it was cast in 2000.

The bell remained at its intended home until 1608, when the ruler of Thanlyin, on the opposite shore of the Yangon River from Yangon (then called Dagon), decided he had a better use for all that metal.

At the time, Thanlyin (or Syriam) was under the control of Filipe de Brito e Nicote, a Portuguese mercenary who in 1599 had led a Rakhine force that had sacked Thanlyin and Bago, then the capital of Lower Myanmar. De Brito (better known in Myanmar as Nga Zinga) had already earned the ire of local people by melting down several bells to forge cannons. But it was his decision to steal the Dhammazedi Bell for this purpose that ensured his infamy in this country for centuries to come.

Using elephants and forced labor, he had the bell moved to the Yangon River, where it was placed on a raft for transport to Thanlyin. However, much to the satisfaction of onlookers, de Brito’s plan to turn a sacred object into weapons of war failed when the raft fell apart and deposited the bell far below the river’s surface.

Five years after this episode, King Anaukpetlun of the Taungoo dynasty recaptured Thanlyin and had de Brito impaled on a stake—a punishment reserved for defilers of Buddhist temples. But 400 years after the Portuguese governor of Thanlyin met his ignominious end, the story of how he tried, and failed, to steal the Dhammazedi Bell continues to resonate in the imaginations of Myanmar citizens and foreigners alike.

Since then, there have been many attempts to retrieve the bell, but poor visibility, silting, nearby shipwrecks and four centuries of shifting currents have so far made the task impossible.

But everybody “knows” that it is still there—as late as the 19th century, some claimed that it was visible at low tide— and so the search continues.

Some who have tried and failed, including tycoons and powerful generals, now say the quest is cursed. Jim Blunt, an American diver from California, was told as much when he made his own attempt in 1995 with the cooperation of the Myanmar authorities.

“Several divers had already died looking for the great bell, including two Myanmar Navy divers who became trapped inside a wreck and died horribly. Consequently, the search [began] for outside expertise,” Mr. Blunt told the London-based newspaper The Independent.

Mr. Blunt carried out 116 dives over a period of two years. In a documentary film about his experiences, he claimed that he banged his fist on the bell and was rewarded by a metallic sound.

Historian U Chit San Win has made it his mission in life to relocate this lost artifact of Myanmar’s past. Since 1987, he has led a number of searches, including one in 1996 that was

supported by then Military Intelligence chief Gen. Khin Nyunt.

During one attempt in the 1990s, U Chit San Win lost a son to rabies. However, when asked what he thought about the curse that many believe is on the bell, he declined to give a direct answer.

Others have been less reticent about their concerns. At a recent meeting between U Chit San Win and a government minister that was observed by a senior member of The Irrawaddy’s staff, the minister attentively listened to a detailed method statement and proposal to launch another search, but in the end declined to back the project because, he said, he feared for the safety of his family.

Despite such misgivings, some remain determined to find the bell that they believe will save the nation.

In October, U Khin Shwe, a leading Myanmar businessman and politician, announced a plan to fund another hunt for the bell, saying that he would spend more than US$10 million if necessary to return it to the glittering Shwedagon Pagoda.

“We’ve already hired big ships to salvage the bell. If we succeed, we will put it on display at Shwedagon,” he told The Irrawaddy. “One foreign expert predicted that the whole operation would cost between $5 million and $10 million. Whatever the cost, I’m ready to spend it.”

Some suspect U Khin Shwe’s agenda. As a powerful member of the ruling Union Solidarity and Development Party sitting in the Amyotha Hluttaw, or Upper House of Parliament, he is regarded as a controversial figure. Both he and his Zaykabar Company, a conglomerate with interests in the construction and telecommunications industries, have been on the US sanctions list since 2007, and more recently he was involved in a highly publicized land rights dispute with farmers on the northern fringes of Yangon.

U Khin Shwe first came to the attention of policy makers in the West in the 1990s, when he paid the Washington, D.C.-based public relations firm Bain

and Associates more than $20,000 a month to help burnish the image of Myanmar’s military junta. To return the favor, state media proudly proclaimed him to be a “doctor” with an honorary Ph.D. from “Washington University of the United States,” which turned out to be an unaccredited degree-mill incorporated in Hawaii but operating from a post office box in Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania.

Never one to miss a chance to improve his public image, U Khin Shwe (who is related to powerful Pyidaungsu

But as a veteran of the quest, U Chit San has more practical advice: Go high-tech.

“I don’t believe the bell can be recovered without the use of the latest technology, because according to my experience, using local technology won’t work,” he told The Irrawaddy last year.

Nearly two years ago, it looked like U Chit San Win’s dream might finally come true. At a seminar held in Yangon in June 2012, a Singapore-based trading company, SD Mark International LLP Co., said it was willing to spend up to $10 million to finance a non-profit project to find the bell and convey it back to Shwedagon.

The search was expected to take 18 months to complete. But since it was first announced, nothing has come of it. According to a source familiar with the project, it was quietly shut down by the Ministry of Culture, which had planned to participate, because of concerns about a lack of funding.

U Chit San Win said he has no intention of giving up. “It has to be out there somewhere,” he said.

Hluttaw, or Union Parliament, Speaker U Shwe Mann through his son’s marriage to the daughter of the former top general) has more recently joined other junta cronies in attempting to cozy up to opposition leader and Nobel laureate Daw Aung San Suu Kyi.

Many suspect, then, that his highprofile plans to find the Dhammazedi Bell are little more than just another PR exercise designed to enhance his personal status.

In any case, if he is serious about finding the bell, he has no shortage of people willing to offer words of encouragement.

One well-known monk from Mon State has suggested that his mystical powers could ensure the success of the mission.

Even as he said these words, however, he looked somber, as if he were reflecting on his past failures and on the loss of his son. Now in his late sixties, he seemed resigned to the possibility that he might not be around to witness the day the bell is restored to its former glory.

One hurdle, he acknowledged, is that many in the country don’t want the bell to be found by foreigners. That’s why he supports U Khin Shwe’s mission, he said.

The bell, he says, is a beacon of hope. “Our country is so poor and plagued with conflict. Many people believe that if the bell is found, it will bring us peace and prosperity,” he said.

But will the spirits that many believe saved the Dhammazedi Bell from being turned into cannons now allow it to fall into the hands of shady businessmen?

Many might argue that if that is to be its fate, perhaps it is better off where it is—submerged in mud, far from the grasp of mortal men and their schemes and dreams.

Is Myanmar’s military laying the groundwork for peace, or setting the stage for an assault on its most formidable enemy?

By BERTIL LINTNERIf blogs that normally reflect the strategic thinking of Myanmar’s military leadership are to be believed, the hitherto peaceful Wa Hills may become a battlefield when this year’s rainy season is over.

Military action against the United Wa State Army (UWSA) would no doubt be popular among the Myanmar public at large, which sees the group as a stooge of China. Even the international community would most likely be sympathetic to a campaign to clip the wings of the UWSA. Unlike other armed groups in Myanmar, the UWSA is perceived internationally as a drug-trafficking organization, not a group fighting for ethnic rights or some political ideal. Several of its top leaders have been indicted on drug trafficking charges by a US court.

But the plan to attack the UWSA could also explain why the government wants to see a nationwide ceasefire agreement signed with all other ethnic groups no later than August. Political talks can be held later, the government says.

If the blogs are correct, what they are saying actually casts doubt on the government’s overall policy towards the ethnics: Is it meant to find a lasting

solution to Myanmar’s decades-long ethnic strife, or is it just a clever divideand-rule strategy to defeat the other groups by a variety of means, including wearing them down at the negotiating table?

For there is nothing to indicate that the military is prepared to give in to the demands of, for instance, the Kachin Independence Army (KIA) and other more genuine ethnic groups that seek a return to the federal system of government that Myanmar had before the 1962 military takeover.

In his speech to mark this year’s Armed Forces Day on March 27, Commander-in-Chief Snr.-Gen. Min Aung Hlaing held the ethnic groups responsible for the violence in the country’s ethnic areas and said: “We made peace agreements, but that doesn’t mean we are afraid to fight. We are afraid of no one. There is no insurgent group we cannot fight or dare not to fight.”

Exactly two years earlier, on Armed Forces Day 2012, Snr.-Gen. Min Aung Hlaing also made it clear that there was little room for negotiation on fundamental political issues, saying, “The military has an obligation to defend the Constitution and will

continue to take part in politics as it has done in the past.”

In February of this year, the Tatmadaw, or Myanmar armed forces, conducted a massive military exercise in a central part of the country codenamed “Anawrahta” after the founder of the first Myanmar Empire, who reigned from Bagan from 1044 to 1077 and is one of Myanmar’s celebrated warrior kings.

According to Hla Oo’s Blog, a promilitary website, the war game consisted of “a combined Infantry-AirforceTanks-Missiles-Artillery assault on an enemy’s fixed position” like the UWSA’s headquarters at Panghsang on the Chinese border. The blog pointed out that a similar war game took place in March 2012 and was “then followed by a large-scale ground and aerial assault on KIA’s Laiza Headquarters in December 2012.”

This time, “the large-scale assault will be short but brutally decisive” as the Tatmadaw now has “massive firepower” including “short-range tactical missiles and heavy artillery.” The aim would be to “smash” the UWSA and drive “the Chinese Wa,” as they are referred to, “back into China.” If successful, Myanmar’s military would emerge stronger and perhaps also more popular than before—which could increase the chances of the military-backed Union Solidarity and Development Party doing well in the 2015 general election.

Military observers note that the government signed a ceasefire agreement with the KIA in February 1994—and then attacked the Karen National Union (KNU), capturing its Manerplaw headquarters in January 1995. In January 2012, the government signed a ceasefire agreement with the KNU—and later that year launched a massive attack against Laiza. Even if there may be little sympathy for the UWSA among other ethnic armies in Myanmar, agreeing to a ceasefire in August would nevertheless neutralize them and make it easier to attack Panghsang before the end of the year.

If it did decide to mount a decisive assault on the UWSA, however, the Tatmadaw would have to be prepared to face the armed group’s Man-Portable

Air Defense Systems, or MANPADS, and other sophisticated military equipment it has obtained from China over the past few decades. No other rebel army in Myanmar is as heavily armed and militarily as strong as the UWSA.

So far, little or no attention has been paid to the Myanmar military’s strategic thinking in regards to the so-called “peace process.” Discussions have centered on “a nationwide ceasefire,” after which a “political dialogue” may be held. The government’s own outfit, the Myanmar Peace Center, has received massive funding from the European Union and other international donors, while a cabal of foreign “peacemakers” and “reconciliation experts” are flocking to the country to get their share of the pie.

The problem is that few if any of those “foreign experts” have a very deep understanding of the complexities of Myanmar’s ethnic problems. And, as critics are also eager to point out, these “experts” are paid more in one month than an ordinary Myanmar worker can earn in five years or more. “Peacemaking” has become a very lucrative industry in Myanmar—at least for the foreign experts and their organizations. And so far, no one has discovered that it is, in fact, a very shrewd strategy designed to outmaneuver and neutralize the nonBamar ethnic groups without giving in to any of their demands.

While the leaders of the ethnic armies are being bribed with carimport licenses and other economic incentives, many of their followers are unhappy with those arrangements. The result is discord and even splits within those groups and between the various

ethnic armies, making this an effective divide-and-conquer game to defeat the ethnic resistance.

In most other peace processes, talks are held first and agreements are signed when a consensus has been reached. No signatures are required for the preceding ceasefire that could be agreed upon verbally. But in Myanmar, the government and the foreign peacemakers are putting the cart before the horse, asking for an agreement to be signed first and then vague promises of talks later.

The model for that kind of strategy would be a somewhat similar peace process in the Indian state of Nagaland. In 1997, the insurgent National Socialist Council of Nagaland (NSCN; the Isaac and Muivah faction) signed a ceasefire agreement with the Indian

government. Today, 17 years later, no less than 80 rounds of talks have been held in what clearly amounts to delaying tactics on the part of the Indian government. Meanwhile, the NSCN’s fighters are getting used to a comfortable life in socalled “peace camps”—and the Naga public is turning against them. They continue to demand “taxes” from the public while the leaders are becoming corrupt, spending the money they have collected on new houses and cars.

A similar development could be seen in Kachin State between the KIA’s signing of a ceasefire agreement in 1994 and when the government decided to break it in 2011. During those 17 years, the KIA lost much of the popular support it had preciously enjoyed—while the government’s attacks over the past two and a half years have galvanized the Kachin nation and made the rebels heroes in the eyes of most Kachins.

The KIA is not likely to repeat the mistake it made in 1994—nor would the “Naga model” work in Myanmar. The NSCN is only one group and it wants to separate Nagaland from India. Myanmar has more than a dozen ethnic armies, and they want federalism, a far more reasonable and realistic demand.

So will killing Myanmar’s ethnic groups with sugar-coated bullets and military action against the UWSA work? One has to consider why the ethnic rebels took up arms in the first place. A nationwide ceasefire agreement will only freeze the problem, not solve it.

And if the offensive against the heavily armed UWSA fails, the Myanmar military is in serious trouble. Whatever the outcome, the foreign peacemakers can always carry on to another conflict zone on the globe—and leave a mess behind in Myanmar.

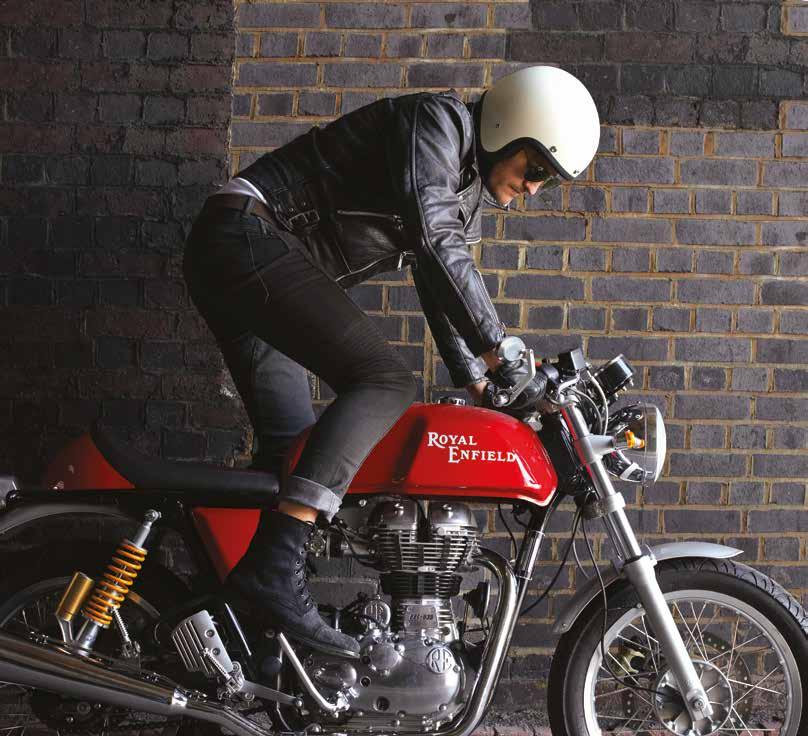

A landmark international exhibition showcases art of exceptional beauty from Myanmar and Southeast Asia

By THE IRRAWADDY / YANGON

By THE IRRAWADDY / YANGON

Previous page, main image: Iconography, which appears to be of Vaishnava (Vishnu), on a 5-ft sandstone throne stele from Sri Ksetra, ca, 4th century. Lent by the National Museum of Myanmar, Yangon.

Previous page, below: Pyu coins. Central Myanmar, 6th - 8th century. Discovered in Myingmu Township, Sagaing Region. Lent by the Department of Archaeology and Museums, Yangon.

Above: Buddha Preaching. Silver. Central Myanmar, 6th century. Lent by the National Museum of Myanmar.

Magazine cover image: The Khin Ba Relic Chamber Cover. Sandstone. Central Myanmar, 6th century. Lent by the Thiri Khittaya (Sri Ksetra) Archaeological Museum.

Far left: Ganesha. Sandstone. Central Vietnam, late 7th-8th century. Lent by the Museum of Sculpture, Da Nang, Vietnam.

Left: Devi, probably Uma. Sandstone. Eastern Cambodia, Pre-Angkor Period. Lent by the National Museum of Cambodia, Phnom Penh.

Above: Yaksha. Sandstone. Central Vietnam, early 6th century. Lent by the Museum of Cham Sculpture, Da Nang, Vietnam.

The religious and sculptural traditions of former kingdoms of Myanmar and Southeast Asia have gone on display in a landmark exhibition in New York City, in the first of two watershed shows set to mark Myanmar’s cultural “coming out” to international audiences.

“Lost Kingdoms: Hindu-Buddhist Sculpture of Early Southeast Asia, 5th to 8th Century,” opened at the New York Metropolitan Museum on April 17.

In 2015 the New York-based Asia Society is due to present another groundbreaking exhibition

of early Buddhist art from Myanmar.

The “Lost Kingdoms” exhibition showcases ancient polities that are still emerging from the shadows as scholars and archaeologists uncover new clues and offer fresh interpretations of entities long hidden in history’s mists.

The exhibition includes treasures from the Pyu civilization, which flourished in Myanmar before it was absorbed by the Bagan Empire, as well as from the Funan, Zhenla, Champa, Dvāravatī, Kedah and Śrīvijaya civilizations in neighboring countries.

The show includes some 160 sculptures of singular aesthetic

accomplishment in stone, gold, silver, terracotta and stucco from Myanmar, Thailand, Cambodia, Vietnam and Malaysia.

More than 20 items from Myanmar are on display.

Together the collection illuminates through art and imagery the emergence of the early kingdoms in the region in the first millennium, and how these embraced many influences from early Buddhism and Hinduism (Brahmanism), grafting the new ideas on to older animistic belief systems based on the worship of nature.

At the center of a display called “Arrival of Buddhism” are a silver Buddha, warrior plaques, miniature silver stupas and a spectacular stone slab from the oldest undisturbed Buddhist relic chamber in Southeast Asia, the Khin Ba stupa mound at the Pyu city of Sri Ksetra, dating from the late 5th to 6th century.

The longest Sanskrit inscription known from ancient Myanmar can also be seen. The Sri Ksetra exhibits also include a 4th century sandstone stele with imagery from both Hinduism and Buddhism on either side.

A section called “State Art” focuses on the patronage of the Mon rulers of the Dvāravatī Kingdom of central Thailand and includes some of the most monumental works in the exhibition: several large-scale sandstone standing Buddhas, sacred wheels of the Buddha’s Law, and steles depicting stories from the present and past lives of the Buddha.

Other masterpieces of exceptional beauty include an ascetic Ganesha from the 8th century religious sanctuary of My Son in central Vietnam and a spectacular Krishna Holding Mt. Govardhana from the hill shrine of Phnom Da, in southern Cambodia.

“Lost Kingdoms” marks the first time the Myanmar government has

loaned national treasures for an international loans exhibition. The government will also loan items to the Asia Society event next year. In return, the American institutions will assist with training Myanmar conservators.

This month the Metropolitan Museum will host a day-long symposium on the exhibition, including two talks relating to the Pyu in Myanmar.

On May 17 scholar Janice Stargadt of Cambridge University will present a paper on “The Great Silver Reliquary of Sri Ksetra: Where Early Epigraphy and Buddhist Art Meet.”

Robert Brown of the University of California, Los Angeles, will discuss “What Was the Impact of Indian Art and Culture in Southeast Asia? Pyu and Mon Art Under the Looking Glass.”

The latest spotlight on the Pyu comes as Myanmar is seeking to gain World Heritage List status from Unesco in mid-2014 for three Pyu sites: Sri Ksetra, Beikthano and Hanlin.

“Lost Kingdoms” is open to visitors until July 27.

There is also a 336-page hardback catalog for the exhibition, featuring contributions from prominent scholars, photography shot on location, maps and a glossary of place names.

It is co-published in this region by River Books in Bangkok, with Yale University Press, and costs around $70.

Helping Myanmar to bridge distance

Network Design

• Network Architecture, Optimum path from 2G/3G to LTE

• RF Planning

• Spectrum Re-farming

• RAN Network Design, Capacity Planning, Network Dimensioning

• Core Network Design

Network Optimization

• LTE Optimization

• 2G/3G Optimization / Cluster Optimization

• End-to-end Optimization

Consulting Services

• We provide business consulting services, Network Architecture options analysis, migration towards new technologies (LTE, IMS), optimized path from 2G/3G to LTE We provide consulting engineering servies

Network Performance Management

System Integration

Test Activities

Network Troubleshooting

Network Tracing

Network Tracing

• We provide turnkey engineering services (design, optimization)

Tools

• SPT Telecommunication is versatile in the use of multiple tools, or tools that fits customer’s preference.

BORDER TRADE: Myawaddy on journey from smugglers' paradise to free trade gateway

U Chit Khine of the Myanmar Rice Federation on what's needed to improve the prospects of the rice industry

Since Myanmar’s current government took power three years ago, the country’s rice exports have steadily increased. Now no longer confined to markets in Asia and Africa, Myanmar’s rice is increasingly finding its way to the West, including the United States and the European Union. Recently, The Irrawaddy’s Kyaw Hsu Mon had a chance to speak with U Chit Khine, the chairman of the Myanmar Rice Federation, about the outlook for an industry in which Myanmar was once a key international player.

What is your role as the chairman of the Myanmar Rice Federation?

As chairman of the Myanmar Rice Federation, and also as head of Mapco [the Myanmar Agribusiness Public Corporation], my role is to do whatever I can to improve Myanmar’s rice industry.

What is Myanmar’s ranking among rice-exporting countries?

Myanmar is still behind Thailand, Vietnam and India as an exporter of rice. Last year, we exported just 1.5 million tons, and this year will probably be less, because we need to rebuild our rice-cultivation system and improve our milling system. Those are challenges for us.

Myanmar’s advantage is that we

have GSP [Generalized System of Preferences, a preferential tariff system that provides for formal exemption from the more general rules of the World Trade Organization] status for export products. This means that we are in a good position to compete if we can improve the quality of our rice. At present, our main market is southern Africa, but demand there is decreasing, so we need to find new markets. That means we have to change our entire process of producing and exporting rice. Since 2009, many ricerelated companies have been involved in helping to improve the industry. The federation is also teaching farmers about the different kinds of seed. Even if we improve the milling process, the quality will still suffer if the rice we are growing is not very good.

Until now, we’ve only had lowquality rice to sell, but we’re looking to change that. Last year, we exported 5,000 tons to Japan, and this year we will increase that to 6,000 tons. This is just a first step toward winning the trust of markets in other developed countries.

Many farmers in Myanmar are struggling financially. What can be done about this?

First we need to get their debts under control by offering insurance to reduce risk. We also offer awareness training. Another problem they face is a shortage of workers in the paddy fields, so we make mechanized farming equipment available to them on a rental basis. We are also collecting data about how many rice mills there are in Myanmar, so we can assess their needs. The government could also help, for example by enacting a land law.

What kinds of problems do rice traders face?

Transport costs are a major problem

that cuts into the profitability of ricetrading. For example, even if we sell rice for US$400 a ton, we will earn 20 percent less than a rice trader in another country [selling for the same price] because of high shipping costs here. The reason for that is the long waiting time at ports in Myanmar, especially during the rainy season. To address this problem, we need to improve port facilities. That’s why Mapco is building a grain terminal at Thilawa port, which will be completed in late 2015.

What are the major international markets for Myanmar’s rice?

Until recently, we relied mostly on markets in southern Africa, but these days we are expanding to other areas, such as Russia, the EU, Singapore and Japan.

What is the current situation with regard to exports to the EU and US?

We are just starting to export there, but we need to upgrade our rice mills to improve the quality of the rice. The EU market now welcomes our rice exports and will import more in the coming season.

What are the main rice-producing areas in Myanmar?

Ayeyarwady Region is still the top rice producer. Bago Region and Mon State are also important rice-producing areas, and Sagaing Region has the potential to become one in the future.

Why is there still very little interest among foreign investors in Myanmar’s agriculture sector?

Some investors are starting to take an interest, but they are learning that there are a number of problems affecting this sector, such as the lack of transportation and power infrastructure, and land disputes.

President U Thein Sein has called for the cultivation of the new Pearl Thwe paddy seeds for the export market, but so far with little success. Why is that?

It’s a complicated issue. There have been demonstrations of hybrid paddy cultivation in Naypyitaw, but for farmers, it’s all new. So there needs to be awareness training for the farmers, and also financial and other support. Because the cultivation cost is much higher, it would be good if the government provided loans.

What else can the government do to assist the agriculture industry?

Parliament has recently approved laws that will protect farmers’ interests, such as rules and regulations affecting land mortgages, credit loads and longand short-term credit. If it also passed laws on agriculture insurance, it would benefit farmers greatly.

By KYAW HSU MON / MYAWADDY, Kayin State

By KYAW HSU MON / MYAWADDY, Kayin State

As the largest of five official checkpoints for overland trade between Myanmar and Thailand, Myawaddy has long been associated with commerce—often of the illegal kind. These days, however, its reputation as a hub for smuggling is changing, as the town assumes new importance as a future gateway of the Asean Economic Community (AEC), set to be launched in 2015.

Located opposite the Thai town of Mae Sot on the Moei River, Myawaddy established itself as a major conduit for contraband during Myanmar’s socialist era, when it was one of the few places where foreign-made goods could make their way into the country.

“It was a very popular city for smuggling in the 1980s, when the Burma Socialist Program Party banned imports,” recalled U Aung Myo Shein,

the manager for corporate social responsibility at the Parami Energy Group of Companies, during a forum on the AEC held in Myawaddy in early April.

“There were a lot of people involved in bringing goods from Myawaddy to other cities, especially Yangon, in those days. Now, of course, most of this trading is done legally,” he added.

Even after the collapse of the socialist regime in 1988, however, smuggling remained a way of life in Myawaddy, with ethnic armed groups such as the Karen National Union and the Democratic Karen Buddhist Army playing a major role. Only recently, with the return to quasi-civilian rule in 2011 and subsequent efforts to end conflict in the country’s border regions, has the growth of legal trade begun to outpace smuggling.

Official trade figures show that crossborder trade with Thailand increased by more than 20 percent over the past year, from US$3.7 billion in 2012-13 to $4.46 billion in 2013-14, with exports making up $2.7 billion of the total in the fiscal year that ended in March.

Myawaddy’s growth has been a more modest but still significant rise of nearly

9 percent, according to officials at the forum, which was hosted by Parami Energy.

“When the AEC is established next year and goods begin to flow freely across the border, Kayin State will become a major gateway. That’s why we decided that traders in Myawaddy needed to learn more about it, and start preparing for the challenges it will present,” said U Aung Myo Shein.

Myawaddy is not the only border town to get a crash course on what the AEC is likely to bring. Parami Energy has organized 12 similar events at various locations, including at the border crossing of Htee Khee (linking the deep-sea port and special economic zone of Dawei to the Thai border) and at Muse-Shwe Li (Ruili) on the Chinese border.

Once it is in place, the AEC will transform the 10 member states of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (Asean) into a region where goods, services, investment, skilled labor and, to a lesser extent, capital can flow freely across borders. Following a master plan laid out in the Asean Economic Blueprint adopted in Singapore on Nov. 20, 2007, the AEC will have a major impact on trade throughout the region.

As a first step toward economic integration, the Asean countries have been reducing import duties on goods

from fellow members to between zero and five percent since 2008.

As relative newcomers to the regional bloc, the CLMV countries (Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar and Vietnam) will be allowed to continue imposing tariffs on some products for three years after the AEC is established. However, even these countries have already begun lowering trade barriers in line with the movement toward open borders.

“Myanmar is one of the CLMV countries, so we have been given until 2018 to eliminate obstacles to the flow of goods, but we have already reduced import taxes on some home appliances and marine products,” said Daw Tin Tin Htwe, a senior consultant with Parami Energy and former director of the Ministry of National Planning and Economic Development.

“The Thai government has been supporting their traders to prepare for the AEC, so we must do the same,” she added.

But Myanmar’s business community will need more than just helpful advice if it is to be able to compete successfully in an increasingly open marketplace. The country’s severe lack of energy and transportation infrastructure could also prevent local businesses from entering the AEC with a running start.

To help address this problem, the Asian Development Bank has funded

construction of a section of the Asian Highway Network from Myawaddy to Kawkareik, also in Kayin State. According to Kayin State Chief Minister U Zaw Min, the new highway, which connects Myawaddy and Yangon, is due to be completed by the end of the year.

“Trade will increase more after the construction of the Asian Highway, which runs through Kawkareik and Myawaddy, and will link us up to other Asean highways,” he said, adding that some parts the road had already been finished by a Thai construction company and Myanmar’s Ministry of Construction.

Regarding his state’s readiness for the AEC, U Zaw Min expressed cautious optimism.

“If you ask me if we’re ready right now, I would have to say no. But we’re not that far behind, and I’m sure we can manage it, just like other countries,” he said.

“Challenges should not be something to worry about. If we know about the latest technology, knowledge and processes, we can turn challenges into opportunities. That’s why we’re training businesspeople to understand the trading process here,” he added.

To some extent, however, it will be up to Myanmar’s businesspeople to learn for themselves what they need to know in order to survive under the new rules. And in many cases, that will be largely a matter of common sense.

“If we want to do more business with the Thais, we’ll need to speak Thai,” said Daw Thin Thin Myat, chairwoman of the Myawaddy Border Traders Association.

“Most agricultural equipment and electronic products are imported from Thailand. If we can’t speak Thai when dealing with Thai traders, negotiating with them will be harder. Even when we’re selling thanakha, we have to use Thai.”

Meanwhile, workers also profess only the dimmest awareness of what the AEC will mean for them.

“All I care about is whether it will mean more business for Myawaddy,” said Ma Swezin Htet, a salesperson in a local shop. “As long as I can earn more money to support my family, I’m happy.”

The Export-Import Bank of the United States (Ex-Im Bank), a government-owned bank that provides loans to aid American exporters, announced in February that it would return to Myanmar after 27 years away, reflecting improving ties between the government and the United States.

Initially, in terms that are subject to regular review, Ex-Im Bank can only give out short- and medium-term loans and only for so-called sovereign projects that have the backing of the Myanmar government. The move is a clear signal, however, that the United States is keen not to be left behind as Myanmar’s market opens up to more foreign goods, and as infrastructure is developed.

In March, Patricia Loui, a member of Ex-Im Bank's board of directors, visited Myanmar, meeting with government officials and US businesses working in the country. She also sat down with a group of reporters, including The Irrawaddy’s Simon Lewis, at the US embassy in Yangon, discussing the bank’s re-entry into the country, and the impact it will have.

We have long roots here. In 1934, we financed the Burma Road, specifically [Ex-Im Bank] financed a loan of about US$25 million and it was for the acquisition of US trucks from General Motors and Ford that were used in the construction process.

Our last transaction here was in 1987, so it’s been almost 30 years and we’re very pleased with the progress that this country has made in terms of opening the economy and the move towards a more open government and democratization. The macroeconomic environment is such that we were able to open on Feb. 6.

[When entering a country,] we

do a country risk assessment. That country risk assessment takes into consideration both the ability to repay as well as the willingness to repay. Our economist was here last fall, analyzing the macroeconomic conditions, as well as conducting assessments of the infrastructure, the transparency, the rule of law, and the conditions that really business looks for in making investments in a country, and that combination of factors, as well as the political opening of the county, has made us forward leaning.

What services are you offering in Myanmar?

We are open for sovereign lending for both the short and medium term, so up to five years amortization, in bank guarantees, insurance, credit insurance as well as direct loans.

We’ve been working both with the US Chamber of Commerce, as well as with the US-Asean Business Council, and their memberships, in assessing potential opportunities that US exporters see in [Myanmar], and some of the areas that are high on the list are: opportunities in the energy sector, both oil and gas as well as in renewable energy; also in the health facilities and health equipment sectors—General Electric has already had a couple of transactions in this area—and there’s also a strong interest by US exporters, and we believe a market demand, for telecommunications infrastructure. These are just some of the top sectors, but we are certainly open to working with the government of this country in terms of bringing American technology and American quality and American innovation to help the broader economic development.

Is there a limit to how much you can loan out for companies wanting to export to Myanmar?

Ex-Im does not have country limits in terms of its authorizations or its exposures and we also do not have sector limits. So really we go and we meet demands for export financing from the US where there are gaps between what the exporter is seeking

and what the commercial markets are willing to offer.

We go where there is this gap. And we did find there that there was very strong interest. Ex-Im’s mission is to provide financing support for US exporters. So, as the forwardleaning US exporters began entering this market, there was more and more interest in our ability to help them finance the exports, whether it’s through guarantees or direct loans, or through credit insurance. So we cannot just enter the market because this market was closed for so long. But given the interest of US exporters, we did reassess, and obviously all of this was triggered by the suspension of sanctions initially on the part of President Obama.

What benefits will Ex-Im Bank’s presence bring to Myanmar?

Ex-Im, as with the US government as a whole, is really here to encourage responsible investment into the country, and I think that our American

brand really is quite well known for the high standards that we’ve set for corporate social responsibility, and giving back to communities, as well as our very high standards in the environmental sector, and just trying to find an approach that is of mutual benefit.

I like to say that Ex-Im’s approach really is win-win. And the reason I say that is that besides the financing that we can provide for US exporters, we can also finance 30 percent of local costs. So for example if a power plant or a solar field is being developed here, there would need to be the construction costs, there would need to be the installation, there would need to be the staff training, so that would fall under local costs. So that 30 percent of the contract value is really a direct infusion into the local economy, and in fact the World Bank studies have shown that when foreign investment like [from] the United States is infused into an Asean member nation, the rate of GDP growth increases by about 3 percentage points per year. So that’s

really win-win. We’re interested, yes, in supporting US exporters, but it does result in infusion into the local economy that benefits the broader economic development of the country.

How do the currently suspended US sanctions against Myanmar impact your work here?

We’ve been focused [on the question]: “Given the environment, which included the suspension of sanctions, how can we maneuver? How can we do what we need to do to assess the environment and to open [Ex-Im Bank in Myanmar]?” This is the first step. Obviously, we’re now open in the sovereign sector. We hope that as conditions improve—as there is more rule of law, as there is more transparency, as there is more financial infrastructure; again, the conditions that can assure the businesses and US exporters that we will be able to be repaid—that we can expand our relationship. But right now we’re quite happy to be where we’re at, frankly.

Although financiers in Myanmar have been trying since 2012 to form the country’s first credit bureau, concerns about how much foreign involvement in the process should be allowed have delayed their efforts, bankers said in April.

The Central Bank of Myanmar aims to form the credit bureau to allow lenders to check the backgrounds of prospective borrowers, with assistance from the Credit Bureau Singapore, according to U Ye Min Oo, the managing director of Asia Green Development Bank.

“Though the Central Bank of Myanmar and bankers have been trying to form a Myanmar credit bureau since then [2012], now it’s been delayed by organizers because the CBM is having second thoughts about how to form it. [It is] considering whether or not to allow foreign participation,” he said.

Under the initial agreement made in 2012, the Credit Bureau Singapore was to take a 40 percent stake in shares of the yet-to-beformed bureau, and Myanmar’s Central Bank, along with domestic private lenders, were to take the remaining 60 percent.

Phone calls by The Irrawaddy to the spokesperson for the Central Bank of Myanmar went unanswered. —Kyaw

Hsu MonChina’s investment in Myanmar “plummeted” in 2013 to only US$20 million or 5 percent of the value invested in 2012, Chinese media reported.

And last year’s figure was a mere 1 percent of the value of Chinese investment in Myanmar in the peak year of 2010, said China Radio International.

“The rules of the game [in Myanmar] have changed. In 2011, a civilian government came to power. China’s plummeting investment coincides with the announcement of the 2012 foreign investment law,” the state broadcaster said, quoting the China Business News

newspaper.

“As for ranking of foreign investors, China lost the leading position for the first time in four years and dropped to around 10th,” the paper reported.

It said there was a degree of inevitability about China losing its No. 1 investor status with the ending of Western sanctions and a changing economic culture in Myanmar.

“Chinese companies need to understand the situation, change their mindset, put themselves in Myanmar’s position, use their own advantages so as to reenter the Myanmar market with competitiveness.” —William Boot

Trade across Myanmar’s land borders grew by more than a fifth last year, with goods being traded to and from China making up the majority of the trade, an official said.

U Than Aung Kyaw, director of the Ministry of Commerce, told The Irrawaddy that a massive 83 percent of the trade was across the border with China in the 2013-14 fiscal year. Myanmar also shares land borders with Bangladesh, India, Laos and Thailand.

Total imports and exports across all borders reached US$4.46 billion from April 2013 to March 2014, compared with $3.7 billion of trade in the previous year, he said.

The only official trade crossing on the China-Myanmar border is Muse in Shan State, opposite Ruili in China’s Yunnan Province. U Than Aung Kyaw said Myanmar was importing large quantities of Chinese-made home appliances, foodstuffs, electronics and construction materials.

According to figures provided by U Than Aung Kyaw, exports made up $2.7 billion of the trade through Muse, while imports hit $1.76 billion. U Than Aung Kyaw did not say what the large volume of official exports from Myanmar was made up of.

Trade through the Muse-Ruili border overshadows the rest of Myanmar’s border trade. There are five official crossings on the MyanmarThailand border. Trade through the largest crossing point, Myawaddy-Mae Sot, was worth just $290 million in 2013-14, but this was a rise of almost 9 percent on the previous year. —Kyaw

Hsu MonMyanmar’s economy is forecast to grow by an average 7.8 percent over the next two years.

The annual increase is predicted by the Asian Development Bank for the 2014-2015 and 2015-2016 financial years. It’s slightly higher than the bank’s estimate of economic growth during the financial year ended in March.

“Growth [in 2013] was supported by rising investment propelled by improved business confidence, commodity exports, buoyant tourism, and credit growth, complemented by the government’s ambitious structural reform program,” said the ADB in a statement in April.

Myanmar’s international investment profile was raised last year by several major factors, including the award of telecommunications licenses, airport construction bids, hosting the World Economic Forum on East Asia and staging the Southeast Asian Games, said the ADB report. – William Boot

Myanmar banned foreign fishing vessels from its waters from the beginning of April amid concerns about overfishing.

U HanTun, vicechairman of the Myanmar Fisherman Federation (MFF), said that large Myanmar fishing companies would also reduce their fishing operations at sea by 35 percent during April and May—the reproductive season for many marine species—to allow fish stocks to replenish.

Foreign fishing boats had been allowed to purchase permits to fish in Myanmar’s waters since 1989. In the 2013-14 fiscal year— which came to an end last month—around 40 foreign fishing boats were operating, according to the MFF.

Being landlocked and poor has always placed Laos at a disadvantage to its more powerful neighbors. The only body of water that offers Vientiane an international reach is the Mekong River, which flows through the heartland of Southeast Asia.

Now, that river, which laps the western fringes of the capital Vientiane, has become the staging ground for Laos to flex its diplomatic muscles. The secretive communist party that runs the country is even prepared to stand up to the region’s other, more powerful and wealthier communist-dominated regime—Vietnam.

An April summit of the four riparian countries that share the Mekong— Cambodia and Thailand, in addition to Laos and Vietnam—exposed the tension that has surfaced between these communist twins. Like Vietnam, Cambodia is also at odds with Laos over its determination to push ahead with plans for a new dam where the Mekong snakes through southern Laos, just over a mile from the Laos-Cambodian border.

“Though already being informed by the Lao side that work on the project will be started by the end of this year, both the Vietnamese and Cambodian sides have agreed that Laos should comply

with the 1995 MRC [Mekong River Commission] Agreement,” Nguyen Minh Quang, Vietnam’s minister of natural resources and environment, said at the closing press conference of the Second Mekong River Commission Summit, held in Ho Chi Minh City in April. “We [Vietnam and Cambodia] also recommend that Laos only begin work on the project after new rules come into effect.”

This is not the first time that Hanoi has been in such a huff with Laos over plans to build on the Mekong. Before the current project—the 260-megawatt Don Sahong Dam—became a cause for concern, the Vietnamese government expressed disapproval over the much larger Xayaburi dam, a 1,260-megawatt project being built on the river’s mainstream in northern Laos.

In fact, a January meeting of the four member countries of the Mekong River Commission (MRC) found Laos cornered, with even Thailand expressing reservations about the Don Sahong Dam. Nevertheless, Laos appears determined to forge ahead with the project by skirting around binding MRC agreements, including the one alluded to by the Vietnamese minister, which requires “prior consultation” and regional agreement on dams that could impact the Mekong’s flow.

“At the moment there is no consensus on the Don Sahong Dam, because three countries require the project to be subject to prior consultation since they have raised concerns about its impact,” Surasak Glahan, spokesman for the Vientianebased MRC, told The Irrawaddy. “Laos says prior consultation is not necessary because the volume of water that will be impacted by the dam will be small.”

Laos has stuck to this view since October, when it formally notified the MRC that it will proceed with the dam. Viraphonh Viravong, Laos’ deputy minister of energy and mines, declared at the time that it would not breach the 1995 agreement because the dam is not being built on the Mekong mainstream, but on one of the 17 channels in the Siphandone stretch, where the water flow through the channel accounts for

only five per cent of the river’s flow. Such a unilateral view ignores the case advanced by Vietnam about the dire consequences its rice bowl—the Mekong Delta—could face if dams are constructed on the mainstream. The flow of sediment down the Mekong into the delta is crucial for the 20 million people who live there. Nearly 90 percent of the rice Vietnam exports is grown in the delta. Loss of sediments from the Mekong exposes this 15,400-squaremile (40,000-square-km) flat, marshy terrain to saltwater erosion from the mouth of the river, which faces the South China Sea.

Cambodia, meanwhile, views the Don Sahong Dam as a threat to its much-needed fish stocks. A barrier on the only channel, the Hou Sahong, that is the chosen route for fish all year would impact migration, feeding and

breeding, “creating trans-boundary impacts,” notes the NGO Forum on Cambodia. It is a loss that would affect the diets of Cambodians, given that fish and aquatic resources provide for “76 percent of animal intake, 37 percent of protein intake, 37 percent of iron intake and 28 percent of fats intake of the Cambodian population,” according to a 2013 study by the Cambodian Fisheries Administration, a government agency. These Cambodians are among some 65 million poor people across all four countries depending on the Mekong for their sustenance. The river’s reputation as the world’s biggest and most productive inland fisheries waterway also makes it a money spinner. And between US$2.2 billion and $3.9 billion worth of fish is harvested from the river each year, accounting for nearly one-fourth of the world’s annual catch.

No wonder, then, that environmentalists are perturbed: Laos’ readiness to sink agreements with its neighbors over a shared international river demonstrates that national interests are still winning out over wider concerns. “This is a test of regional cooperation and it is failing,” Ame Trandem, Southeast Asia program director for International Rivers, a global environmental campaigner, said in an interview. “Laos is setting a very bad precedent about how to ignore the 1995 agreement.”

Activists fear the worst for the nearly 3,100-mile-long (5,000-km-long) river, which begins its journey in the Tibetan plateau, roars through southern China and touches Myanmar before heading south through the Mekong Basin. Laos, after all, has set its sights on building nine dams on the Mekong’s mainstream in its quest to become an exporter of hydropower to neighbors like Thailand.

Vientiane’s ambition to become the “battery of Southeast Asia” has been defended for economic and development reasons: The millions of dollars in foreign exchange it will generate will help raise the living standards of the third of its nearly six million population still mired in poverty. And its defiance on the diplomatic front has been attributed to the growing influence of China, which has already built four mega-dams out of a planned eight with little consideration (and no prior consultations) for downstream countries.

But this go-it-alone approach is coming at the cost of Laos’ “special relationship” with Vietnam, forged after US troops were defeated in the Vietnam War, and cemented by a 1977 treaty of friendship and cooperation.