www.irrawaddy.org TheIrrawaddy November 2014 Vietnamese Food in Elegant Setting

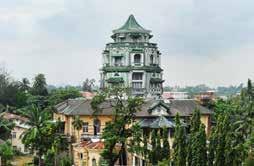

Lim Chin Tsong’s Lavish Palace

WHOSE NEWS? Information wants to be free LET IT BE DR. SAI SAM HTUN LOOKS AHEAD NAGA HILLS: FORGOTTEN FRONTIER

Taunggyi Festival: Magic and Loss

No.86/A, Shin Saw Pu Road, Sanchaung Township, Yangon. Tel. 09 450013761 E-mail : info@lanacha.com www.lenacha.com Nacha Restaurant Nacha Spa Opening Hour 10 am. to 10 pm. beauty and wellness Authentic Thai foods by a Thai chef Relax your mind, your spirit, and your body and embark on a journey of well being. ......... .........

Irrawaddy

Irrawaddy

Feel the superior boutique-style living, which blends modern and oriental culture, together with a peaceful atmosphere in the heart of Chiang Mai. On Sirimangkalajarn Road, Soi 1, near the shopping, business and art district around Nimmanhaemin Road, our facilities include a swimming pool with a saltwater chlorination system, fitness, a green area and parking. S Condo is the perfect choice for a convenient lifestyle.

Feel the superior living of boutique style which blended Modern with Orientral culture. The charm of peaceful atmosphere in the heart of “Chiang Mai” at Sirimangkalajarn Rd. Soi 1, nearby attractions shopping, business and art district at “Nimmanhaemin Rd.” A perfect choice for convenient lifestyle. Loose your self in our facilities swimming pool with salt clorinated system, fitness, green area and 100% parking.

672 4214 / +66 (0) 53 219 300

4 TheIrrawaddy November 2014 +66

www.scondocm.com

(0)81

scondosales@gmail.com

Sales

at

Soi.11

Sirimangkalajarn Soi.1 Chiang Mai “ S CONDO” Residential Condominium Project Owner: Prattana Properties And Healthcare Co.Ltd. Registered Capital : 50,000,000 Baht. Managing Director : Mr. Surat Leenasirimakul Type of Project : 1 building, 7 storeys with 48 Residential units Location : 7 Sirimangkalajarn Rd. Soi.1 Suthep , Muang District, Chiang Mai 50200. Land Title Deed No: 19774 Approximate Land Area : 1-0-79 Rai. Construction Permission: 305/56 Construction Begins : November 2013 Expected Completion : July 2015. The Project will be registered as a residential condominium upon completion. Swimming pool , fitness , car park are common property of Condominium Juristic Person Regulations. The owner of each condominium unit will pay for common area and sinking fund expenses as stated in the Condominium Juristic Person Regulations.

Gallery

Nimmanhaemin

–

THAILAND CHIANG MAI

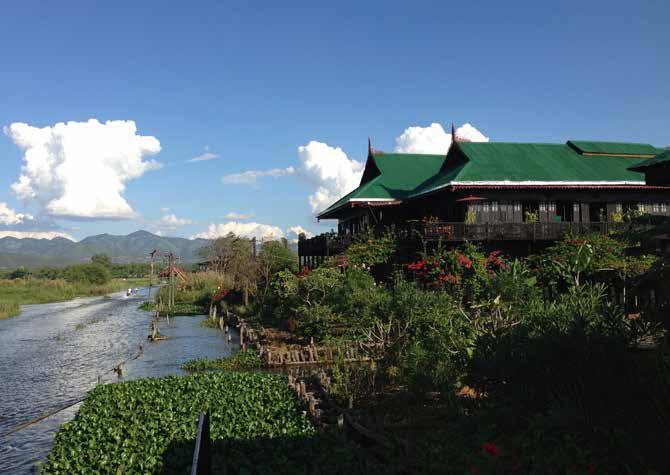

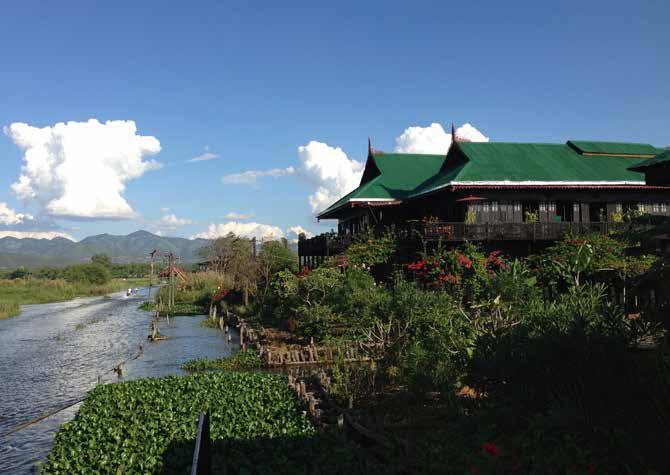

5 November 2014 TheIrrawaddy Magyizin Village, Inle Lake, Shan State, Myanmar Tel & Fax: +(95-81) 209055/ 209364/ 209365/ 209412 Mobile : (95-9) 525 1407, 525 1232 A restful retreat to nature on Inle Lake surrounded by Shan Hills Preserving our heritage to transmit to the future generation as received from ancestors Inpawkhon Village, Inle Lake, Shan State, Myanmar. Reservation: +95 - 9 4931 2970 Mobile: +95 - 9 528 1035 Email: intharheritage@gmail.com ADVERTISEMENT

November 2014 No. 1-A / 3, 28th Street, Between 52nd x 53rd Streets, Mandalay. (One block away from Rupar Mandalar Resort) Tel: 09-910 48506, 09-500 2151 www.littlemandalay.com E-mail: littlemandalay@gmail.com ...truly Mandalay ...simply quaint... 2014 Winner of ‘Certificate

Excellence’

TripAdvisor ‘A little bit of Mandalay’ Tavern + Restaurant Try the taste that makes “A little bit of Mandalay” the right choice in Mandalay. • Restaurant since 2002 • Tavern with 24 Twin Rooms • Restaurant capacity 180 Pax • Myanmar and Chinese Cuisines • Home-cooked curries & more • Packed Lunch Boxes available for Cruises & late flights.

of

by

Irrawaddy

Irrawaddy

TheIrrawaddy

The Irrawaddy magazine has covered Myanmar, its neighbors and Southeast Asia since 1993.

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF: Aung Zaw

EDITOR (English Edition): Kyaw Zwa Moe

ASSOCIATE EDITOR: Sandy Barron

COPY DESK: Paul Vrieze; Andrew D. Kaspar; David Kay; Feliz Solomon

CONTRIBUTORS to this issue: Aung Zaw; Kyaw Zwa Moe; Kyaw Phyo Tha; Bertil Lintner; Zarni Mann; Christopher Ian Smith; Kyaw Hsu Mon; Andrew D. Kaspar; Ma Set Hsu; Marie Kesavatana Dohrs; Dani Patteran; William Boot

PHOTOGRAPHERS : JPaing; Sai Zaw; Hein Htet; Steve Tickner.

LAYOUT DESIGNER: Banjong Banriankit

SENIOR MANAGER : Win Thu (Regional Office)

MANAGER: Phyo Thu Htet (Yangon Bureau)

REGIONAL HEADQUARTERS MAILING ADDRESS: The Irrawaddy, P.O. Box 242, CMU Post Office, Chiang Mai 50200, Thailand.

YANGON BUREAU : Building No 170/175, Room No

806, MGW Tower, Bo Aung Kyaw Street (Middle Block), Botataung Township, Yangon, Myanmar.

TEL: 01 388521, 01 389762

EMAIL: editors@irrawaddy.org

SALES&ADVERTISING: advertising@irrawaddy.org

SUBSCRIPTIONS: subscriptions@irrawaddy.org

PRINTER: Chotana Printing (Chiang Mai, Thailand)

PUBLISHER LICENSE : 13215047701213

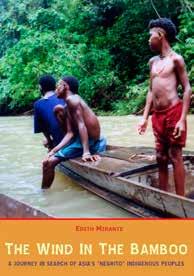

8 TheIrrawaddy November 2014 Contents 10 | In Person Dr. Sai Sam Htun 12 | Quotes and Cartoon 14 | News Highlights 16 | In Focus 18 | Viewpoint The parachute effect LIFESTYLE 55 | Festival Of Joy And Loss The spectacular floating fire balloons of Taunggyi 60 | Tech: Gaming With A Side of Culture A determined team of videogame developers is creating games with a distinctly local edge 64 | Books: Hanging on, Just In search of some of Asia’s leastunderstood indigenous people 66 | Restaurant: Vietnamese Class An atmospheric eatery serves fresh, traditional fare in a sophisticated setting 68 | Backpage: A Movie for Our Times ‘‘The Monk’’ enjoys continued success

Vol.21 No.10

ILLUSTRATION : Bagyi Lynn Wunna 2014

www.irrawaddy.org TheIrrawaddy November 2014 Vietnamese Food in Elegant Setting

Loss WHOSE NEWS? Information wants to be free LET IT BE

Lim Chin Tsong’s Lavish Palace Taunggyi Festival: Magic and

DR. SAI SAM HTUN LOOKS AHEAD

NAGA HILLS: FORGOTTEN FRONTIER

FEATURES

20 | History: The House on an Island

A flamboyant Chinese tycoon left behind a lavish colonial-era palace

24 | Border: The Forgotten Frontier

On the Myanmar-India border, a history of insurgency and regional rivalry continues to resonate

28 | Society: Elephants of the Valley

A compassionate couple have created a lush green sanctuary for former working elephants

32

|

Environment: Old Ways of the Future

The traditional practices of Kayin villagers in northern Thailand could be part of the solution to a very modern problem, a study finds

36 | COVER Whose News?

The government's plan to keep the state as a dominant player in daily newspapers does not match the nation's democratic aspirations

BUSINESS

45

|

Automobiles: Too Many Turns

Frequent policy changes are hurting the car industry, says Dr. Soe Tun of the Farmer Auto Showroom

48 | Energy: Kyaukphyu SEZ

Winners of special economic zone contracts could decide fate of grand project

50 | Signposts: Boost for Rice Exports

REGIONAL

52 | Malaysia: Royals Flex Political Muscle

The role of the sultans goes beyond the ceremonial

9 November 2014 TheIrrawaddy

P-20

P-28 P-55 P-60

‘The Only Way Is Forward’

As Coca-Cola and PepsiCo roll into Myanmar, one of the country’s most powerful beverage companies is busy strategizing its own next move. Loi Hein, a Yangon-based company that dominates the local purified water market with its popular Alpine brand and which is also behind Blue Mountain soft drinks, expects its annual revenue to grow more than five times over the next decade, in part thanks to partnerships with multinational firms.

Its chairman, the physician turned entrepreneur Dr. Sai Sam Htun, tells Irrawaddy reporter Samantha Michaels how he’s dealing with foreign competition and why he’s supporting a football club that’s losing US$1 million a year, while also sharing his thoughts on politics and refuting any suggestion that his success is linked with cronyism.

Let’s start with some numbers. What sort of profits does Loi Hein bring in?

Our business is growing dramatically— it’s moving quite fast in 2014, we’ll reach $100 million in revenue this year. For profit margins, we usually have about a 10-15 percent net margin from revenues.

What’s your market share in the beverage industry?

Gradually in 10 years’ time our market share in the water business has increased to 60-65 percent. But during the past two years, a lot of people have come to play in the water market—not big [companies], but some small and medium ones—so we had to give up about 5 percent of market share in water. Still, my business overall is growing. Water is growing about 25 percent [annually], soft drinks about 40 percent, energy drinks about 50 percent, and we are optimistic because we expect [greater] spending power from Myanmar’s middle class, which is currently only 2 million people, compared with Thailand’s middle class of about 25 million people.

With the lifting and suspension of economic sanctions, CocaCola and PepsiCo have come to Myanmar. How are you dealing with the competition?

They’re still building up their own infrastructure, building up their own brands, so it hasn’t had much impact on our soft drinks. In the future if Pepsi and Coca-Cola fight each other, maybe that will have an impact on us, but we don’t know. If they really come, they may stay in the premium sector, like A and B [upper and middle class consumers], so we will go into the rural areas, staying in the C and D sector [working class consumers]. That’s what we’re planning for the future, if they really come, because they are so powerful that they can paint the whole country in blue and red, so we have to prepare for that.

Would you ever consider partnering with one of these beverage giants?

We were discussing this, but their requirements and our requirements are not the same. Coca-Cola came

and wanted everything of us, which is impossible because my water business has already partnered with Nestlé. They wanted us as one unit, but by that time it was too late.

You already sell drinking water, energy drinks, soft drinks and juices. What’s next?

Since we partnered with Asahi [a Japanese brewery and soft drink company], we will automatically go into beer, either manufactured in Thailand and brought here, or manufactured here. We are also going into dairy: fresh milk and maybe yogurt.

Is there anything missing in the local beverage market?

Nobody is manufacturing natural juices in Myanmar. A lot of drinks come from Thailand, some from China, but we can do import substitution. That’s why we are building a new factory at the moment, which may produce natural juices in 2014 as a substitution for Thai imports. If we finish according to schedule, I think it will be the first [factory] for natural juices in Myanmar.

What are your company’s growth targets?

Since our middle class is growing and the country is opening up, we expect our market size to grow 10 times over the next 5-10 years for our water, soft drinks, energy drinks and other beverages. For revenue, in five years’ time we must go to about $350 million. In 10 years, we can expect about $600700 million.

I heard that once you hit a certain target, you might hold an initial public offering?

I’m still not sure whether an IPO is good for growing our family business—I’m undecided.

Are you planning to expand into banking, insurance or property development?

Maybe microfinance—a purely financial

IN PERSON

10 TheIrrawaddy November 2014

company, but not a bank, so we can finance other companies. We are trying to get a license.

You’re also involved with Myanmar’s national football league, as the owner of the Yadanarbon club. The games are televised, but are you making any money?

We lose about $1 million a year. It [the league] has been going since 2009, and we keep losing money. We charge $1 for tickets but people don’t come to watch. In foreign countries you pay $30 to go to the football stadium. One day if our people can afford it, we will charge $3, and if foreign brands come it won’t be difficult to get $1 million sponsorships to do their branding. Right now is the beginning of multinational [firms] flowing into Myanmar, but we expect one day we will get a sponsorship, TV rights and spectators, and we will break even or make a profit.

But if you’re losing so much now, why stick with it? Is it a personal interest? Are you a football fan?

I should say yes, it’s a personal passion. It’s spending money, it’s just a passion, it’s not about making money.

Lets talk politics. What election results in 2015 would be most beneficial for businesses?

I honestly think a coalition [government] would be best at the moment. For the stability of the country, we need this compromise and a coalition for the next five years. If you take the example of a neighboring country for democracy, when parties fight each other there is no positive result: In Thailand, ultimately the same thing happened [there was another military coup this year]. We don’t want our country to go back the same way.

Loi Hein was very successful under the former government, which may lead people to assume you had a connection with officials to start your business. Has this been a problem?

Not at all, my conscience is very clean … I don’t make money from the government.

I don’t sell products or machines to the government, I don’t sell arms to them. I develop a product, create the market and make money out of the market, and that’s why my conscience is very clear. Also, [my company’s] growth under the military was quite small, but growth during the past three years [under the current government] has been very fast, especially in 2013 and 2014 because of the entry of multinational [companies].

What are your views of the current economic outlook?

The Myanmar economy is quite exciting. Everyone says there is big potential. Whether it is real or not, we have to judge. A lot of investors are quite positive because of the developments in oil and gas, the special economic zones, foreign banks coming in. Many people may have a negative view, and they can have that view. But because of all these things, we are positive. Our country has only one way to go, and that is to grow business. So, we are optimistic, we are excited. There will be some challenges, but we will go forward, there is no choice.

PHOTO:

11 November 2014 TheIrrawaddy

Dr. Sai Sam Htun places a hand on the ornate ship’s steering wheel that sits in his office.

STEVE TICKNER / THE IRRAWADDY

“The President told Prime Minister Prayuth that the Myanmar government accepts that one has to respect Thai law when in Thailand, but he stressed that the Thai government must ensure truth, justice and objectivity in the investigation, to which the Thai premier agreed.’’

—U Zaw Htay, director of the President’s Office, referring to the arrest of two Myanmar migrant workers for the murder of two backpackers on Koh Tao in Thailand.

“We want to make the point that members of the LGBT community should be proud, and we wish to correct wrong messages being spread by popular media.”

—U Hla Myat Tun of the Colors Rainbows civil society group.

“The Myanmar army need to push DKBA troops out of areas near the dam site in order to start [construction] work. They also need to clear KNLA [Karen National Liberation Army] Brigade 5.’’

—Paul Sein Twa of Salween River Watch, which has claimed that a planned dam is behind recent conflicts in eastern Kayin State.

ILLUSTRATION:

THU YEIN CARTOON 12 TheIrrawaddy November 2014 Err... Um

QUOTES

KYAW

Thai Murder Probe Criticized

allegedly beaten and threatened with electrocution after refusing to confess to the murders during a police interrogation. Several other Myanmar migrant workers on Koh Tao who were among those questioned by Thai authorities also alleged police abuse.

Prisoners Released

A small number of political prisoners were among thousands of people granted amnesty by the Myanmar government in October.

A statement by the President’s Office, released on Oct. 7, announced that 3,073 prisoners would be granted freedom on account of their “good manners” and in accordance with the Constitution.

The Thai police investigation into the murders of two British tourists on Koh Tao in southern Thailand in September was roundly criticized after allegations emerged of the torture and illtreatment of Myanmar suspects.

Two Myanmar migrants, Ko Zaw Lin and Ko Win Zaw Htun, are suspected of murdering Hannah Witheridge, 23, and David Miller, 24, on Koh Tao in Thailand’s Surat Thani province on Sept. 15. Their pre-trial hearing began on 14 October.

The two migrants were

In a statement released on Oct. 7, London-based rights group Amnesty International called on Thai authorities to “ensure an independent and thorough investigation into mounting allegations of torture and other ill-treatment by the police, and respect the right to a fair trial” for the two Myanmar suspects.

President U Thein Sein reportedly asked for “justice and fairness” in handling the case during his meeting with Thai Prime Minister Prayuth Chanocha in Naypyitaw on Oct. 9. — Saw Yan Naing, Kyaw Kha and Reuters

Among the thousands released were 3,015 Myanmar nationals and 58 foreigners, the statement said.

The release came just over a month before Myanmar hosts a summit of leaders from the Association of Southeast Asian Nations that US President Barack Obama and other world leaders are expected to attend.

At least three political prisoners were among those released as well as at least eight former highranking military intelligence officials jailed after a 2004 purge that followed the ousting of former spy chief Khin Nyunt by then-Snr.-Gen. Than Shwe.

The Myanmar group, Assistance Association for Political Prisoners, said about 73 political prisoners are believed to still be in detention. —

Zarni Mann and Reuters

NEWS HIGHLIGHTS ADVERTISEMENT 14 TheIrrawaddy November 2014

PHOTO: REUTERS

Police measure footprints near the murder scene on Koh Tao.

Karen Cooperation Agreement Heralds Uncertainty

commander of a small Karen splinter group, the KNU/ KNLA Peace Council, also joined the agreement.

Irrawaddy Founder Among Press Freedom Awardees

In mid-October, commanders of different Karen armed groups vowed publicly to begin military cooperation in the face of growing government army operations in southeastern Myanmar.

On Oct. 14, Karen National Liberation Army (KNLA) Vice-Chief of Staff Gen. Baw Kyaw Heh and Karen National Defense Organization (KNDO) leader Col. Nerdah Mya signed an agreement with Gen. Saw Lah Pwe, the head of the Democratic Karen Benevolent Army (DKBA), in which they pledged to cooperate militarily. Col. Tiger, a

However, the following day, Saw Roger Khin, chief of the KNU department of defense, sought to distance the organization’s political leadership from the agreement. He said in a statement that the KNU leadership was not involved and that the agreement “was signed by the KNLA vice-chief of staff and the commander of the KNDO… through their own ideas.”

The agreement was potentially significant as it would further cooperation between the KNU and the DKBA. The latter is a Buddhist Karen group that broke away from the KNU and joined the government in 1994 after falling out with the KNU’s predominantly Christian leadership. —Nyein Nyein

Aung Zaw, the founding editor-in-chief of The Irrawaddy, was among four international journalists awarded the Committee to Protect Journalist (CPJ)’s 2014 International Press Freedom Award. The award is an annual recognition of courageous reporting and acknowledges the work of journalists who have faced imprisonment, violence, and censorship. This year’s other awardees were journalists from Iran, Russia and South Africa.

CPJ Executive Director Joel Simon said “the journalists that CPJ will honor with the International Press Freedom Award are undeterred and unbowed. They have risked all to bring us the news.” The CPJ noted that The Irrawaddy, like other Myanmar media, “still comes under pressure from the current Burmese government.”

Just days after the award was announced, The Irrawaddy’s website was defaced by hackers calling themselves the “Blink Hacker Group.” The Irrawaddy’s home page was replaced with a message accusing it of supporting “jihad and radical Muslims.”

The cyber attack was linked to The Irrawaddy’s coverage of nationalist Buddhist monk U Wirathu’s trip to Colombo to attend a convention organized by a controversial Sri Lankan Buddhist group. —The Irrawaddy

Thai PM on Two-Day Trip to Myanmar

Thailand’s newly installed Prime Minister Prayuth Chan-ocha visited Myanmar on Oct. 9-10, his first official overseas visit since assuming the top job.

The recently retired general met with President U Thein Sein in Naypyitaw, where the two leaders discussed pushing ahead with the stalled Dawei Special Economic Zone (SEZ) project in southern Myanmar, migrant labor issues, and plans to develop economic zones in border areas.

Slated as Southeast Asia’s biggest industrial estate, the Dawei SEZ,

which also includes a deep-sea port and highway, railroad and oil pipeline routes to Bangkok, has faced numerous challenges—not least of which are local grievances over forced evictions and the project’s heavy environmental impact.

A handful of Myanmar activists in Yangon turned out to protest during the Thai prime minister’s two-day trip against the arrest of a pair of Myanmar migrants accused of murdering two British tourists on southern Thailand’s Koh Tao in September. —Yen Snaing

15 November 2014 TheIrrawaddy

A soldier from the KNLA [right] greets a DKBA counterpart at a military base in 2011.

PHOTO: THE IRRAWADDY

PHOTO: THE IRRAWADDY

Thailand’s Prime Minister Prayuth Chan-ocha salutes members of the Royal Thai Army after a handover ceremony for the new Royal Thai Army Chief in Bangkok last month.

PHOTO: REUTERS

The Irrawaddy’s founding editor-in-chief, Aung Zaw.

16 TheIrrawaddy November 2014

Worried Parents

Daw May Thein, left, and U Tun Tun Htike, parents of Ko Win Zaw Htun, one of two Myanmar workers suspected of killing British tourists in Thailand, pass the time at a monastery outside Yangon on October 16. Relatives of the two Myanmar suspects who were arrested in Thailand's beach island Koh Tao for killing two British tourists said on October 16 that their sons had been arrested unjustly by Thai police. They were planning to travel to Thailand to meet their sons.

IN FOCUS

17 November 2014 TheIrrawaddy

PHOTO: REUTERS

From Top Brass to a Bureaucratic Class

Decades of military appointments to key positions in government have left Myanmar’s administrative apparatus in tatters

By KYAW ZWA MOE / YANGON

By KYAW ZWA MOE / YANGON

Gen. Ne Win died 12 years ago, but the dictator’s disastrous legacy lingers on in Myanmar. One of the worst aspects of his decades-long rule: a “parachute policy”—so called in Myanmar for the way in which high-ranking military officers are dropped in from above to preside over ministries and other administrative departments—that has destroyed the administration of government in the country.

If this particular policy had not been so assiduously implemented over the years, Myanmar might not have been dragged into the political, economic and social abyss that has left the country one of Asia’s poorest.

The appointment of active and retired military officials to various positions of power, from low-ranking ministerial bureaucrats all the way up to the presidency, is a rare practice in governance globally—with good reason.

When Gen. Ne Win staged a coup in 1962, he came to power determined to reorganize the whole administrative structure, which had been a largely civilian-dominated system since the country’s independence in 1948.

When Myanmar’s inaugural government took the reins of the former British colony in January 1948, the country’s first premier U Nu formed an overwhelmingly civilian cabinet. Out of 19 cabinet ministers,

only three were active or former military officers. Nearly 85 percent of the cabinet was occupied by civilian ministers.

In 1952, after the country’s first parliamentary election, U Nu’s party won again and his newly formed government was comprised of 22 cabinet ministers. This time, among them were only two former military officials.

VIEWPOINT

18 TheIrrawaddy November 2014

From 1948 to 1962, a similar ratio of civilian and military officers in governments was maintained—the exception being a two-year spell from 1958 to 1960, when U Nu handed over power to Gen. Ne Win’s interim government.

As a result of this civilian rule, the cabinets were diverse, and skillful professionals and administrators predominated. The governments of

this era also appointed many ethnic ministers in respective ethnic regions of the country.

But Gen. Ne Win’s 1962 coup brought about a U-turn. As chairman of the Revolutionary Council regime, he formed an eight-member cabinet comprised of seven high-ranking military officials and one civilian, U Thi Han, who was responsible for the ministries of foreign and labor affairs.

From then on, Gen. Ne Win’s cabinets would be dominated by military men. At times, his government lacked a single civilian minister. Even after a constitution was approved in 1974, active and retired military officials occupied every key position of government.

This is not to say that governments over this period were rotten to their cores. Professional and competent administrators existed, but always working under active or retired military personnel who had little or no knowledge of their respective areas of responsibility. You can imagine the morale problem this would breed. You can imagine why good brains would leave the country for better opportunities abroad.

The 2013 book “Strong Soldiers, Failed Revolution” found that from the mid-1970s to the end of the 1980s, 94 percent of cabinet ministers in Myanmar were active or retired military officers. The Japanese author Yoshihiro Nakanishi compared the country with Thailand, where military appointees constituted roughly 25 percent of the Cabinets during those years.

Nakanishi estimated that between 1972 and 1978, the military transferred about 2,000 of its officers to various ministries as well as to the powerful local People’s Councils of the Burma Socialist Programme Party, which was founded by U Ne Win.

“The decreased influence of the civil service in Burma [Myanmar] was inextricably linked with the increased influence of the military officers,” Mr. Nakanishi writes.

U Ne Win systematically destroyed Myanmar’s civilian administrative apparatus and in its place entrenched a military alternative that held back

the country’s progress for nearly half a century. All successive regimes, up until 2011, followed his model.

Perhaps even more troubling, the incumbent U Thein Sein’s quasicivilian government has effectively still been applying this policy. In today’s “reformist” administration, active and retired military officials continue to hold key ministerial posts and other high-ranking positions of power.

When U Thein Sein formed his quasi-civilian government in March 2011, he appointed 29 active or retired military officials as ministers in his 36-member cabinet. It was not surprising, but the decision was proof positive that U Thein Sein has continued to apply U Ne Win’s “parachute” policy.

Although the general-turnedpresident has reshuffled his cabinet several times over the past few years, at least 29 former generals and highranking military officials still occupy key ministry posts.

This interference in politics by the military for decades has brought about the systematic gutting of the country’s administrative apparatus.

U Thein Sein seems to have no intention of overhauling this failed policy for the preferable alternative— appointing the right people to the right places, without favoring those from his military clique. He has had ample time over the past three years to do this.

Parachute appointments in governments of Myanmar are likely to continue, not only for cabinet ministers but also even for the country’s top job. No one doubts that U Thein Sein became president in 2011 with the blessing of his boss, ex-supremo Snr-Gen. Than Shwe.

Though Myanmar has opened up to some extent since 2011, the government largely remains a cabal of military leaders dressed in civilian costumes.

As long as this parachute policy remains in effect, Myanmar is unlikely to be steered by its leadership toward the good governance and democratic rule that many have fought for decades to attain.

19 November 2014 TheIrrawaddy ILLUSTRATION:

Kyaw Zwa Moe is the editor of the English-language edition of The Irrawaddy.

BAGYI LYNN WUNNA 2014

The House on an

HISTORY

Island

A flamboyant Chinese tycoon left behind a lavish colonial-era palace

By AUNG ZAW / YANGON

When the writer and former British civil servant Maurice Collis decided to return to Myanmar in 1937 to visit Shan State in the north, he first stopped in Yangon where he was invited to stay at a “house on an island.” In his book “Lords of the Sunset,” Mr. Collis described enjoying excellent paintings by famous Myanmar painter U Ba Nyan in a house with porcelain, Persian carpets, bronze drums, a waxed floor and a white poodle. The house was built by the wellknown Chinaman Lim Chin Tsong, the author briefly noted.

Lim Chin Tsong was a Chinese tycoon who successfully built a business empire on rubber cultivation, textiles and the oil, rice trading, mineral mining and banking sectors. He was the son of a Chinese Hokkien migrant from Fujian province in China. His father, Lim Soo Hean, came to Yangon in 1861 and began trading rice and selling agricultural products.

Lower Myanmar was then ruled by the British who were preparing to take over the upper part of the country still ruled by King Mindon. In British-ruled Yangon, business was competitive and Lim Soo Hean soon discovered his main limitation: a poor education. He was unable to communicate in English with foreign merchants—either Indians or Europeans.

He then sent his 16-year-old son, Lim Chin Tsong, to St Paul’s College in Yangon to study but did not live to see his beloved son take over his work and build one of the most successful businesses in Southeast Asia.

21 TheIrrawaddy

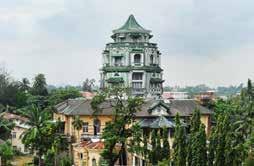

The palace left by Lim Chin Tsong features a mix of Eastern and Western architectural styles.

PHOTO: STEVE

TICKNER

At 18-years-old, Lim Chin Tsong assumed his father’s business after Lim Soo Hean passed away in 1885— the year British troops marched into the grand Mandalay Palace and detained the king and queen before sending them into exile. The whole of Myanmar was then under British control.

The young and energetic Lim Chin Tsong began to grow the business empire, buying ocean-going vessels, exporting rice and expanding his shipping business to Singapore, Penang, Hong Kong, Guangdong, and Amoy (now known as Xiamen).

Among businessmen of that era, the Chinese tycoon was regarded as talented and strategically minded, using the trademark “Xie De” to denote many of his business ventures and products. He soon managed to secure a deal with Burma Oil Corporation (BOC), a large oil company based in the United Kingdom, and was appointed as the exclusive product agent for the region. His involvement in the oil industry saw his wealth flourish and he became one of the richest Chinese tycoons based overseas.

Lim Chin Tsong was flamboyant and showy but he was also known to be generous in his philanthropy projects, donating money to establish schools for students to learn English and to build a hospital for women in Yangon.

In 1905, he and his business partners established Anglo-Chinese Boys’ and Girls’ Schools in Yangon. Two years later, he built his own school officially known as the Lim Chin Tsong School.

One is delighted to learn of the Chinese tycoon’s genuine efforts to upgrade education at the time, particularly when many in Myanmar today learn only about the exploitative practices of greedy Chinese businessmen in the country.

The Lim Chin Tsong School, located in downtown Yangon, employed teachers from England on decent salaries and produced many Englishtrained graduates, some of whom were Chinese students from Hong Kong and Macau pursuing their education in Yangon, according to some historical records.

Lim Chin Tsong also served as a member of the Legislative Council of Myanmar. In 1919, he was awarded the Order of the British Empire for his fundraising efforts during World War I. He was also a prominent member of the Rangoon Turf Club and the Lim Chin Tsong Polo Cup endured even after his death.

In 1917, Lim Chin Tsong began to build a magnificent and lavish residence in Yangon near Kokkine Road, now Kaba Aye Road. The fivestorey structure of red bricks and

green tiles was built to resemble the Fu Xiang pavilion in the Yihe Yuan (Summer Palace) of Beijing but in fact, the building featured a blend of Eastern and Western architectural designs. It took more than two years to build at great cost—some reports suggested a figure of around 2 million rupees.

Materials and craftwork for the

November 2014

PHOTO: THE BURMAH OIL CO LTD.

HISTORY

As the palace approaches one hundred years old, its potential future as a heritage building is being discussed.

residence were imported from China and Italian designers, as well as famous British painters, were invited to design the interior. Ernest Procter, an English designer, illustrator, painter and husband to the artist Dod Procter, were among those invited to decorate the residence.

The opulent house was then known

as the Lim Chin Tsong Palace and among locals it was called “Chin Chaung Nan Daw” or Chin Chaung palace. There were no records of how many fancy parties were thrown at the palace but when Georges Benjamin Clemenceau, a French statesman, visited Southeast Asia, including Myanmar, in 1920, Lim Chin Tsong was known to have

entertained him at the residence.

Lim Chin Tsong’s success hit a speed bump when in 1921 the British government banned the sale of rice, except to India, and soon the market collapsed. Some also suggested that his flamboyant ways caused the BOC to withdraw his exclusive agent rights, which incited him to seek ways to undermine the company. Suddenly, he was broke. He sold his possessions— even his Rolls Royce cars—and began borrowing money from friends. In his final days, the once rich Chinese tycoon was a broken man. In 1923, three years after the inauguration of the Chin Tsong residence, he passed away.

The palace first went to a Japanese creditor (under Japanese rule in Myanmar from 1941-45, the residence housed the All Burma Broadcasting Station), then to Indian businessman and then to the Myanmar government in 1950 when it was turned into a state guesthouse named Kanbawza Yeiktha. Currently, the Fine Arts Department under the Ministry of Culture maintains an office and an arts school within the building.

The house that saw Lim Chin Tsong’s downfall, and many ups and downs in the country, has stood throughout the decades. Now children who live in the area play nearby and stray dogs harass the odd curious visitor. Some nervous officials at the Ministry of Culture would not allow visitors to take pictures. Inside the hall and on the second floor, one can no longer see paintings and other decorations that have perhaps been removed. Lim Chin Tsong’s former residence seems ready for a genuine facelift.

Recent news suggests that the Ministry of Culture will grant Chin Tsong Palace heritage status and renovate the building as it approaches its 100th anniversary, Kyaw Nyunt, director of Yangon Region’s Archaeology, National Museum and Library Department, recently told The Irrawaddy.

The late Lim Chin Tsong who made a significant contribution to colonial Myanmar, not least through some outstanding education projects, would be delighted to learn of the recognition.

23 November 2014 TheIrrawaddy

PHOTO: THE BURMAH OIL CO LTD.

Lim Chin Tsong and his wife, Tan Guat Tean (Daw Po U), in Colombo, Sri Lanka, in 1920.

The Forgotten Frontier

There is no shortage of coverage in local as well as regional media of the ongoing armed conflict in Myanmar’s Kachin State in the north, the activities of the heavily armed United Wa State Army (UWSA) in the northeast or the still volatile situation in areas of Kayin State along the border with Thailand. However, hardly a word is written about the host of armed rebel groups that are active in some of the country’s wildest and most remote mountain ranges which form the more than 1,600 kilometre-long border with India. Yet, this is where the rivalry between Myanmar’s two mighty neighbors, India and China, has often played out and where there is potential for even more trouble in the future.

In the mid-1950s, a rebellion broke out among ethnic Naga tribesmen in India’s northeast. Being a predominantly Christian tribe of Mongol stock, they did not feel that they belonged to India and demanded independence. Not surprisingly, they received support from India’s archenemy Pakistan and training facilities were provided in what was then East Pakistan, now Bangladesh. But more significantly, much more aid came from China.

In 1959, the Dalai Lama fled to India after a failed uprising against the Chinese who had invaded his homeland, Tibet. Asia’s two giants were on a collision course and, three years later, China attacked India and a short but fierce war was fought along a disputed border in India’s northeast.

From 1967-76, nearly 1,000 Naga rebels trekked from northeast India through northern Myanmar to China,

By BERTIL LINTNER

By BERTIL LINTNER

where they received military training. They were sent back to India equipped with assault rifles, light machine-guns, rocket launchers and other modern Chinese weapons. The Naga were escorted by rebels from the Kachin Independence Army (KIA), which, in return for their services, kept some of the Chinese weapons.

Various other insurgent groups in India’s northeast also sought Chinese

assistance. In the early 1970s, about 200 Mizo rebels—a tribe then fighting for self-determination in what is now the state of Mizoram—were trained in China; in 1976, a group of insurgents from the Indian state of Manipur made it to Tibet, where they received political training and some military instruction; and in the late 1980s, rebels from the state of Assam attempted to reach China through northern Myanmar, but

Soldiers from the former National Socialist Council of Nagaland (NSCN) in Naga territory in Myanmar in 1985.

On the Myanmar-India border, a history of insurgency and regional rivalry continues to resonate

24 TheIrrawaddy November 2014 BORDER

PHOTO: HSENG NOUNG LINTNER

ended up staying in areas controlled by the KIA—which trained some of them in guerrilla warfare.

It was clear the rebellions in India’s northeast were not solely an internal affair and that Myanmar, the land in the middle of the two regional powers, would inevitably be drawn in. This became even more evident in the 1970s when the Indian army managed to drive the Naga rebels out of their bases on the Indian side of the border. They regrouped in the rugged Naga Hills of the northern Sagaing Region. There, beyond the reach of the Indian army, they could launch cross-border raids into India.

Myanmar’s military, preoccupied with ethnic insurgencies elsewhere in the country, paid little attention to the Indian Naga who linked up with a group of Naga in Myanmar led by S.S. Khaplang. Manipuri as well as Assamese rebels also sought sanctuary on the Myanmar side of the border.

The only fall-out came in 1988 when the Naga from Myanmar, simply tired of being treated as serfs by their Indian cousins, drove them out of the area. The National Socialist Council of Nagaland (NSCN) then split into two factions: the National Socialist Council of NagalandKhaplang (NSCN-K), led by Khaplang, and the National Socialist Council of Nagalim Isak-Muivah (NSCN-IM), the Indian faction led by Isak Chishi Swu and Thuingaleng Muivah which adopted the name Nagalim, a new term for a “greater Nagaland” encompassing the state of Nagaland as well as most of Manipur, a chunk of Assam, and the Naga Hills of Myanmar. In July 1997, the NSCN-IM entered into a ceasefire agreement with the Indian government and in 2001, the NSCN-K did the same. In April 2012, NSCN-K also struck a ceasefire deal with the Myanmar government, making it the only insurgent group to have ceasefire agreements with the governments of two sovereign states.

But none of this means that the conflicts are over. Hundreds of rebels from various outfits in Manipur as well as the once powerful United Liberation Front of Asom [Assam] (ULFA) are based at Khaplang’s headquarters at Taka near the Chindwin River, north of

25 November 2014 TheIrrawaddy

A female soldier is one of hundreds of rebels from different separatist groups who are based at Taka camp, the headquarters of the National Socialist Council of Nagaland-Khaplang, near the Chindwin River north of Singkaling Hkamti in northern Sagaing Region.

PHOTO: RAJEEV BHATTACHARRYA

Singkaling Hkamti in Sagaing Region. As late as December 2011, the Indian journalist Rajeev Bhattacharyya, who had trekked to Taka, observed ULFA forces taking delivery of a major consignment of weapons that most probably had been smuggled to the base from China. According to other sources, there is a booming trade in weapons acquired along the SinoMyanmar frontier that are smuggled via Mandalay and Monywa to the Indian border. Old stocks from the UWSA’s vast arsenal of weapons and other military equipment have also been found in areas along the IndoMyanmar border.

In late 2012, it emerged that the Myanmar army had obtained Swedishmade 84mm Carl Gustaf rocket launchers most probably supplied by India and intended for use against the

ULFA and other Indian insurgents. They were instead employed against the KIA and a major scandal ensued during which questions were raised in Sweden’s parliament and the Indian ambassador in Stockholm was summoned by the Swedish foreign ministry for an explanation. Ultimately, India submitted a report stating that the weapons, which according to their serial numbers had been delivered by Sweden to India, had not been transferred to Myanmar through conventional channels, and New Delhi promised the Swedes that it would not happen again. For years, India has urged Myanmar to close down the camps that insurgents have established inside Myanmar’s Sagaing Region, but to no avail. It is clear that fighting India’s rebels is not a priority for Myanmar’s military.

And China? When ULFA commander Paresh Barua is not inspecting his troops at the Taka camp, he is in China. Obtaining weapons there does not seem to be a problem. Beijing appears to reason that if India can shelter one of its main enemies, the Dalai Lama, then Barua is welcome to stay in China. The situation promises to become even more entangled as the NSCN-IM continues to express frustration over the direction that 17-year-long negotiations with Indian authorities are headed. Barred from entering Khaplang’s area, NSCNIM cadres in October this year were reported to have been scouting the hills east of Manipur for potential new sanctuaries in anticipation of a breakdown in talks.

New Delhi, of course, wants to see peace established along its entire border with Myanmar so it can implement its so-called “Look East Policy”—aimed at linking India with the booming economies of Southeast Asia. Myanmar’s Wild West may be almost forgotten in today’s discussions about the country’s ethnic issues, but the number of armed groups in the area with conflicting agendas makes it the country’s messiest frontier.

“It is clear that fighting India’s rebels is not a priority for Myanmar’s military.”

caption

26 TheIrrawaddy November 2014

PHOTO: HSENG NOUNG LINTNER

BORDER

A hill-top village in the Naga Hills in northern Sagaing Region was the headquarters of the former National Socialist Council of Nagaland in 1985, and is now thought to be abandoned.

Elephant FEATURE

A compassionate couple have created a lush STORY and PHOTOS CHRISTOPHER

Elephant Valley

green sanctuary for former working elephants

IAN SMITH / KALAW TOWNSHIP, SHAN STATE

Five-year-old elephant Ko Chit toots his trunk in happiness while receiving a bath from Ko Puri and a mahout.

ALL PHOTOS: CHRISTOPHER IAN SMITH

Far out of earshot of the honking vehicles that wind their way down the teak-tree-lined Golden Highway, deep in southern Shan State’s Green Hill Valley, the river is almost all I hear as it rushes past. That is until Ko Chit, the youngest of the bunch at the Green Hill Valley Elephant Camp lifts his trunk out of the water and lets off a few loud toots.

“He’s happy,” smiles Ko Puri—who takes care of the elephants at the camp across from Magwe, a village in Kalaw Township— before rattling off a seemingly unending stream of elephant facts, statistics and history. I turn back to the four-ton bull and take advantage of his calm demeanor to get a close look at his aged and smooth tusks.

Ko Chit has a lot to be happy about. He’s been dubbed the luckiest elephant in Myanmar by U Ba Kyaw Than, the camp’s veterinarian. Trappers hunting for a white elephant in northern Myanmar accidentally snagged Ko Chit instead, and, under U Ba Kyaw Than’s supervision, relocated him to Green Hill Valley. Soon after arrival, one of the older

female elephants adopted him as her own, and at a mere five years old, Ko Chit will never have to work a day of hard labor in his life.

Aside from Ko Chit, Green Hill Valley Elephant Camp’s six other elephants are all retired loggers. In 2011, U Ba Kyaw Than’s niece Ma Tin Win Maw and her husband Ko Htun Htun Wynn opened this camp with ethical treatment of animals as their top priority. Having worked in the tourism industry for decades as tour guides, they had seen firsthand the physical, political and tourism changes that were shaping Myanmar.

From the patio of their solar-powered, ecofriendly community cooperative camp and replantation center, Ko Htun Htun Wynn explains how, with the opening of the country, lots of different kinds of tourism will become available in the coming years. He believes that there’s lots of room for different sectors to grow and operate in a variety of different ways, but if the country is really going to benefit, then it is essential for the industry to adopt ethical and sustainable

30 TheIrrawaddy November 2014

FEATURE

Aged from 5 to 65, most of the elephants at Green Hill Valley are retired loggers and need special medical care.

“The ethical treatment of animals is the sanctuary's top priority”

standards. The Green Hill Valley Elephant Camp hopes to show how adhering to these standards is possible in Myanmar, with the aim of ultimately influencing the tourism industry as a whole.

It’s an ideal that is welcome, as recent cutbacks on the amount of logging permitted in Myanmar will leave a growing number of elephants unemployed. It is assumed that NGOs and the private sector will move to fill the gap by creating elephant sanctuaries and other acceptable alternatives for these elephants, but these efforts are currently far smaller and more isolated than the illegal animal-trafficking industry. The trade is particularly active along the Myanmar’s border with Thailand, as was highlighted by a recent report from wildlife campaign group TRAFFIC.

Since many elephant camps in Thailand have faced criticism for their own ethics and the living standards of their animals, Ko Htun Htun Wynn strongly believes there is a need for Myanmar authorities to closely monitor the companies and organizations that will be starting up camps in the coming years.

“We won’t use elephants as entertainment. We will not do demos or have them play football or paint things…. We invite people to participate in giving care to the elephants. They can feed and bathe them, have a short ride on their back from the river, even hug and kiss them, but no circus things,” explains Ko Puri.

Besides trying to influence future elephant tourism, the camp is taking a more direct approach to addressing environmental issues by asking each visitor to plant a tree. The replantation is not for the purpose of a future harvest, but rather to establish a secondary forest. This is all very fitting, since in 1975 U Ba Kyaw Than worked for the Myanmar Timber Enterprise, which in the past employed more than 20 elephants to heavily log this exact area. The camp administration believes there’s no more appropriate place for reforesting than the land they’re working on and which they call home.

Teak and silver oak sprout in the center’s nursery, just down the stony path that leads to housing for mahouts. Since 2011, more than 6,000 trees have been replanted in the area. Ko Htun Htun Wynn also talks about how the small village of Magwe has taken notice. With 350 villagers living at the base of the camp’s entrance, the potential for local gains from the tourism industry was clear from the beginning, when the elephant camp donated a school to the village.

Like the camp, the school has been growing, and Ko Htun Htun Wynn hopes this will show how ethical practices can benefit not only the business side, but also the community. He also hopes the ideas of conserving and protecting the environment will spread with a cultural exchange. When the villagers see foreigners from around the world planting trees, it helps to emphasize the need to take care of the land, the community and Myanmar’s future.

The ultimate hope is that businesses across all industries, fueled by a coming tourism boom, will see the same sustainable benefits both in terms of profits and nurturing the country.

November 2014

Old Ways of the Future

The traditional practices of Kayin villagers in northern Thailand could be part of the solution to a very modern problem, a study finds

By ANDREW D. KASPAR / YANGON

By ANDREW D. KASPAR / YANGON

As climate change becomes a growing global concern, the quest for new ways to use land resources more sustainably is gaining in urgency. What many researchers are discovering, however, is that some of the best answers can be found in practices that have existed for centuries.

This was the conclusion of a June report from the Indigenous Knowledge and Peoples Network (IKAP), based in Chiang Mai, Thailand. Based on a study of the farming and forestry techniques

practiced among some ethnic Kayin in northern Thailand, the report documents a way of life that is helping to mitigate climate change, reduce soil erosion, and protect biodiversity.

For many in Thailand and other parts of Asia, these findings fly in the face of conventional wisdom, which has long characterized “hill tribes” as poor stewards of increasingly scarce resources. In particular, the slashand-burn method of clearing land for cultivation practiced in many remote regions has been blamed for releasing

vast quantities of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere and producing a sometimes deadly haze that afflicts urban centers and less-populated areas alike.

What the IKAP report found, however, is that traditional practices, rooted in the Buddhist and animist beliefs of Kayin residents of the village of Ban Mae Lan Kham in northern Thailand’s Chiang Mai Province, are often ideally suited to ensuring the long-term preservation of forests, while also providing sustainable livelihoods.

32 TheIrrawaddy November 2014

Rotation of labor: Kayin villagers cooperate to share the hard work of cultivating many useful species among the hill paddy.

ENVIRONMENT

PHOTO COURTESY KESAN

Among the customs that the report highlights are rotational farming, the protection of forests situated between mountains to aid the journeys of spiritual beings, and the sparing from the ax of trees wrapped with the umbilical cords of newborns (the latter practice is said to protect the offspring to whom the umbilical cords once served as lifelines). Areas that house ancient ruins are also left undisturbed, as are burial grounds and other spaces considered sacred.

For the 658 Pgaz K’Nyau, or Kayin, inhabitants of Ban Mae Lan Kham studied in the report, these TajDuf, or constraining rules, serve to “guide the people’s every life practice in utilizing or taking care of the ecological system in suitable and balanced ways.”

The report, based on research conducted from October 2012 to October 2013 in a village tract that covers an area of about 3,100 hectares, finds that these traditions “have proven to be sustainable and in line with climate change adaptation and mitigation strategies even though communities

are not aware or conscious of ‘climate change’ causes and effects.”

A centerpiece of these sustainable land management practices is an eightyear crop-rotation cycle that avoids the soil erosion, nutrient depletion and ecosystem damage that result from more intensive use of the land.

Although slash-and-burn is still a part of this cycle, the study found that the Kayin system maintains the balance between carbon storage and carbon emissions, and also has an added advantage: By giving trees a chance to grow large enough that the timber can be harvested for construction purposes, villagers are able to profit from their conservation.

Indigenous people’s traditional forest knowledge is increasingly viewed as one front in the battle to reduce carbon emissions on a warming planet. A 2007 report from the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change found that indigenous knowledge is “an invaluable basis for developing adaptation and natural resource management strategies in

response to environmental and other forms of change.”

Could Myanmar also benefit from the wisdom of its indigenous approaches to land use? That depends.

According to Saw Paul Sein Twa, director of the Thailand-based Karen Environmental and Social Action Network (KESAN), many of the values held by the Kayin studied in the IKAP report are shared by their ethnic brethren on the Myanmar side of the border.

“The beliefs are the same because culturally we are attached,” he said, adding that recognition of customary land tenure rights was essential to the survival of traditional Kayin agroforestry practices.

“Without that, surely there will be big problems in the near future. I don’t know how well [Myanmar’s] reforms will go, but we can see that more and more development projects and government expansion of its administrative areas is really competing for land with local communities.”

33 November 2014 TheIrrawaddy

ADVERTISEMENT

Whose News?

The government’s plan to keep the state as a dominant player in daily newspapers does not match the nation's democratic aspirations

By KYAW PHYO THA / YANGON

By KYAW PHYO THA / YANGON

ILLUSTRATOR: BAGYI LYNN WUNNA 2014

On a sunny late monsoon day in September, Myanmar’s Information Minister U Ye Htut was taking questions from local journalists and international media observers who packed the Chatrium Hotel’s ballroom in Yangon.

Many in the audience on the opening day of the two-day “3rd Conference on Media Development in Myanmar” expressed skepticism over the government’s plan, first canvassed in 2012, to transform state-owned daily newspapers into public service media. The state-owned Myanmar Radio and Television (MRTV) is also to be transformed into a public service broadcaster.

When one gentleman said that “there is no public service print media in other countries,” the former lieutenant colonel responded: “No, what you said is not true. They exist but are just not successful. But here in Myanmar, we are determined to make it a success.”

However, independent media representatives, including the country’s Interim Press Council, have raised concerns over the newspapers plan and have labeled it unnecessary. They see it as a way to keep the military regime-era propaganda papers afloat, and they seriously doubt the minister’s intentions.

After five decades of strict media censorship since Gen. Ne Win staged a military coup in 1962, Myanmar’s Ministry of Information (MOI) abolished pre-publication censorship of the press in 2012. A year later, the ministry also allowed the publishing of private daily newspapers, while it kept publishing its state-run dailies.

At present, there are three stateowned dailies: two in the Myanmar language—Kyemon (The Mirror) and Myanma Alinn—and one in English, The Global New Light of Myanmar. The English-language paper was

relaunched as a joint-venture with Myanmar firm Global Direct Link in October. All three papers are under the control of the MOI.

A Bad Legacy

In the past the papers made no disguise of their role as government mouthpieces, especially during the period of

the former military dictatorship that ran the country for more than two decades after 1988. Until U Thein Sein took office in 2011, the papers were known for their uninhibited views on political matters. Sustained media salvos were launched against political dissidents and armed ethnic rebels who were portrayed as “destructive elements” that were trying to “disintegrate national solidarity and the Union.”

38 TheIrrawaddy November 2014

COVER STORY

Unsurprisingly, thanks to Daw Aung San Suu Kyi’s rising popularity at home and abroad after 1988, the Myanmar democracy leader was frequently personally attacked. For a time, serialized articles about her appeared almost daily in the papers. In an example of how petty things could get, in a July 7, 1996 story about the opposition leader that appeared in Kyemon, the author, Sein Jittu, refused to use the Nobel Laureate’s full name. She was referred to only as “Daw Suu.” “She is not entitled to use her father’s name,” the author contended, contrasting how Gen. Aung San fought for the country’s independence from Britain, while his daughter went on to marry a British man.

In another article published the same month, Daw Aung San Suu Kyi was addressed as “Myo Pyat Ma” (meaning a woman who causes disgrace and has no loyalty to her race) in reference to her marriage to a foreigner. Another writer said that “she has become part kalar [a derogatory term for foreigners, especially those of Indian descent] by marrying a kalar, joining his family and behaving like a kalar.”

Ethnic armed groups were also a top target of the military government’s propaganda attacks. For three straight months in 1995, following Myanmar army attacks against the Karen National Liberation Army (KNLA), the military wing of the Karen National Union (KNU), the state-run newspapers published cock and bull stories under the title “What is KNU?” A total of 33 stories hammered out the standard message that ethnic armed struggle was undermining national solidarity and would lead to the disintegration of the Union of Myanmar. Then KNU leader Bo Mya was addressed as “Nga Mya.” Nga is an archaic Myanmar prefix that was mostly used by Myanmar kings and high-ranking officials in the old days to denote a “servant” or “slave.”

Beyond these propaganda articles, readers found few informative stories in the state-run papers. Front pages were often splashed with bland

39 November 2014 TheIrrawaddy

Readers’ patience was sorely tested by ‘news’ stories featuring long paragraphs listing only the names of officials.

PHOTO: JPAING / THE IRRAWADDY

articles on humdrum events such as opening ceremonies for schools, roads and bridges by high-ranking military officials. Readers’ patience was sorely tested by long paragraphs in which every official in attendance was named. As a result, many people tuned in to the Myanmar services from the BBC or VOA and exiled Myanmar media for alternative news. The staterun papers were useful mainly to check the “Obituary” section to learn of the death of friends.

A Bumpy Beginning

Aproposed Public Service Media (PSM) bill was published in state-run dailies in May 2013. The then Deputy Information Minister U Ye Htut said that the proposed bill was drawn up with the support of international organizations including the UN Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization and other local and foreign experts. Though the draft covered both print and broadcast media, it was the proposals regarding state print media that have most come under fire, especially from international media watchdogs, journalists and Myanmar’s Interim Press Council.

In a June 2013 statement on Myanmar’s PSM draft, London-based freedom of expression advocacy group ARTICLE 19 said there was no justification for spending public money on public service newspapers, since the aim of enabling a diversity of opinion and information would be better achieved by ensuring that newspapers operated freely.

Myanmar expert Bertil Linter told The Irrawaddy that the PSM model that the MOI seems to be following is that of Singapore, where the government controls news through its own paper, The Straits Times. “No country in the world with a free press has ‘public service newspapers,’ - that’s just a euphemism for a governmentcontrolled press,” said the Swedish journalist, before adding that those international organizations helping the ministry, once infamous for its

40 TheIrrawaddy November 2014

PHOTO: HEIN HTET / THE IRRAWADDY

PHOTO: HEIN HTET / THE IRRAWADDY

COVER STORY

PHOTO: HEIN HTET / THE IRRAWADDY

press censorship, to draft the PSM bill were “naïve and don’t know what they are doing.”

Members of Myanmar’s Interim Press Council have rejected the PSM bill’s stipulation that 70 percent of funding for public service media outlets would be derived from public funds (the other 30 percent is slated to come from advertising, assistance

from development organizations, newspaper sales and donations). They also disagree with the inclusion of print media in the PSM draft, as they say there are few, if any, public service newspapers funded by governments in other countries.

“We don’t need ‘public service’ newspapers,” said U Thiha Saw, a member of the council. “It [creates]

unfair competition because 70 percent of the budget is from the government, while private newspapers are struggling from their own pockets.”

Since privately-owned dailies hit newsstands, most have struggled to stay afloat. Some have even shut down, thanks to high production costs, low advertising demand and smaller market-share compared with the state-funded government dailies of today. Government newspapers also have nationwide printing presses that allow them to distribute their papers to remote parts of the country. In contrast, private dailies are mostly restricted to selling papers in the main cities. The three state-run dailies have a combined circulation of more than 320,000 while the more popular private newspapers only sell about 80,000 copies per day, the Associated Press reported earlier this year.

U Pho Thauk Kyar, a veteran journalist and vice-chairman of the

41 November 2014 TheIrrawaddy ADVERTISEMENT

Since privately-owned daily papers hit the newsstands, most have struggled to stay afloat.

Interim Press Council, said statefunded public service newspapers were inappropriate for a country like Myanmar with a fledgling democracy.

“The government should cooperate with private dailies to promote press freedom. Instead, they are now trying to compete with them. It’s totally wrong,” he said. “If they want to create public service media, they could do it with broadcast media, like in other countries.” Establishing public service broadcast media could be a positive development, the vice-chairman added, as these outlets could air content such as educational programs that private outlets often ignore.

Serving the People?

Despite the criticism, the MOI submitted the PSM bill to parliament in March this year, but it still hasn’t been discussed. A separate draft law, the Television and Radio Bill, which paves the way for public service broadcasting only, was approved by the Parliament’s Upper House in midOctober and is now due to be debated in the lower house.

In defense of public service newspapers, U Ye Htut said during the media development conference in September that state-run papers have been in a process of change for

the last three years and now cover a wider range of topics, including social issues such as labor disputes and HIV. Sometimes they even do a somewhat better job than private dailies, he claimed.

“Let me tell you frankly, when we uncovered a suspected Ebola case in Yangon in recent months, did any private newspapers report the health warning from the Ministry of Health for three days as we [the state-run newspapers] did?” the minister asked rhetorically.

Although U Ye Htut has trumpeted the state-run papers’ capacity to serve the people, the papers have yet to be seen to fully follow some tenets of the government’s own “Code of Ethics for Public Service Media,” compiled by the government-appointed five member PSM overseeing body— the “Newspaper Governing Body”— established in October 2012. In particular, the government dailies appear to be falling short in their responsibility to “timely and accurately inform the public of the matters occurred in the human society,” as described in the code of ethics.

In late August, when the Yangon Regional Government announced that its multi-billion dollar city expansion plan was to be led by a little-known Chinese company, the MOI-owned newspapers remained silent. It was only after the plan drew broader media criticism that the papers published a story, seven days later, which said that the project would reopen for tender. When the project was suspended on Sept. 26, this news was nowhere to be found in the state-owned newspaper editions published the following day.

When local and international controversy arose over Myanmar migrant workers’ alleged involvement in the killing of two British tourists on Koh Tao in southern Thailand in September, all three governmentowned papers were late to weigh in on a story that had become a hot national issue.

Though the Irrawaddy made repeated attempts to contact U Ye Htut, the presidential spokesman was unavailable for comment.

42 TheIrrawaddy November 2014

“Though there have been changes, they are still putting out news that comes from upstairs.”

—U Thiha Saw

PHOTO: SAI ZAW / THE IRRAWADDY PHOTO: JPAING

/ THE IRRAWADDY PHOTO: JPAING / THE IRRAWADDY

U Pho Thauk Kyar

U Ye Htut

COVER STORY

U Thiha Saw

Skepticism

UYe Htut’s vow to transform the state-owned papers has failed to impress many journalists.

U Pho Thauk Kyar said such a transformation was impossible, even if U Ye Htut were the president. “Make no mistake, Myanmar people have lost faith in state media as it has cheated and pushed people into the information dark ages since 1962. Given their past coverage, does [anyone really] think the MOI could change it in the next 50 years?” asked the 83-year old, who has spent the better part of his life as a journalist.

“I explain this to the country’s president as well as to the Parliament speakers from both Houses whenever we meet,” U Pho Thauk Kyar added, referring to the Interim Press Council’s frequent meetings with the country’s top leaders.

U Thiha Saw said that, looking at the current coverage in the state-run newspapers, it seems they are writing for the government rather than the people. “Though there have been changes, they are still putting out news that comes from upstairs.”

That take was perhaps borne out in the way Myanmar’s state media reported on the recent pro-democracy protests in Hong Kong. In the early days of Hong Kong’s Occupy Central protests, the government dailies ignored the story. When an article finally appeared after public criticism, the piece was merely a compilation of pro-Beijing reportage under the headline “Critics Slam Unlawful Protests in Hong Kong.”

Responding to online commenters who questioned the way state media was portraying the protests, U Ye Htut acknowledged on his Facebook page that he had issued a directive to state media organs on Oct. 2 that the

news must be presented sensibly and in accordance with journalistic ethics. Part of that code of ethics was that news reporting must not interfere in the internal affairs of other countries.

U Pho Thauk Kyar said that if the government wanted to develop public service newspapers, the aim was mainly to present its own point of view. “Don’t forget what they said in the past: fight the media by the media,” he said, referring to the former military government’s mission to publish propaganda articles attacking unwanted international reportage on Myanmar.

ARTICLE 19 has recommended that the state-owned print media be privatized and that the PSM bill be reformed to only provide for a public service broadcaster. U Thiha Saw agrees. “What the government should do is to return the papers to the people. They were all private dailies before they were nationalized after 1962.”

43 November 2014 TheIrrawaddy

ADVERTISEMENT

Business

Frequent policy changes are hurting the car industry, says Dr. Soe Tun of the Farmer Auto Showroom

By KYAW HSU MON / YANGON

By KYAW HSU MON / YANGON

ALL PHOTOS: SAI ZAW / IRRAWADDY

AUTOMOBILES ENERGY SIGNPOSTS ENERGY: Kyaukphyu SEZ's uncertain future

Yangon — Import restrictions under the previous military government ensured car prices in Myanmar were among the highest in the world. Now, under the current quasi-civilian government which took power in 2011, restrictions have eased and car prices have fallen dramatically. Legislation has, however, often been less than clear, as car import policies have been frequently changed. The Irrawaddy’s Kyaw Hsu Mon spoke with Dr. Soe Tun, director of Farmer Auto Showroom and a member of the Automobile Dealers Association, on the state of the country’s car industry.

What was the car industry like before recent policy changes?

Before the new government allowed the opening of automobile showrooms in Myanmar, the price of imported cars was incredibly high. Car prices in the country should have been noted in the Guinness World Records as the most expensive.

How have government policies on imported cars changed?

Within two years after the government allowed car imports to Myanmar, import policy has changed about 10 times. The changes in policy have led to losses for people [importers and consumers]. If we calculate the amount, there may have been more than 1 billion kyat [roughly US$1.008 million] lost due to changes in import policy.

Import policies have had many steps. First, car owners who owned models that were more than 20-years-old were allowed to import newer models. Then the government allowed everybody to import cars. Now, cars over 20-yearsold are being taken off the road [for safety].

What is the state of the market today?

There are a lot of imported cars on the market, but only in Yangon. Beyond Yangon, there are only low-cost automobiles for use in rural areas. Import taxes are also still ensuring the price of imported cars remains high.

46 TheIrrawaddy November 2014

BUSINESS INTERVIEW

PHOTO: JPAING / IRRAWADDY

Is it true that the government will only allow left-hand drive vehicles to be imported to Myanmar soon?

It has been more than two years since the Ministry of Industry and the Myanmar Engineering Society began drafting the Myanmar Automobile Act, said to be submitted to parliament soon. Our Automobile Dealers Association representatives also participated in drafting the act. Through our discussions, we have concluded that the government should only allow imported cars that comply with the traffic rules in Myanmar.

Have you heard about some car brokers importing badly damaged cars?

I heard that there were some brokers [who did this]. Three brokers imported badly damaged cars last year and the government took action against them. They were unable to uncover some

of the individual importers but the registered companies involved were blacklisted. Now there are almost no damaged cars being imported.

What types of imported cars are the most expensive in Yangon and what are the most in demand?

In Myanmar, there are two kinds of people in the market to buy a car, the middle class and the elites. The elites are used to buying a variety of expensive cars such as Rolls-Royces. But at present, sports cars are not permitted to be imported.

Are used Japanese cars still in strong demand? What about other well-known international models?

South Korean, Japanese, American, German and Chinese car dealers have recently opened showrooms in Yangon. Only 1,000 new cars have been imported among the 300,000 to

400,000 cars imported to Myanmar so far. Importers of brand new cars are mainly targeting government ministries to buy their models. Recently, the South Korean brand KIA has been leading the new car market. These cars have been granted some tax exemptions and therefore they can sell at lower prices. Actually, international automobile companies are not yet coming to invest in Myanmar. Only dealers and subdealers are entering the market. As long as the basic wage of most people remains low, the market for brand new cars will not grow in Myanmar.

For people wanting to buy a good second-hand car, what should they buy?

For Yangon use only, I would recommend a Honda Fit or a Toyota Vitz which both consume less fuel. For rural use, it seems the Daihatsu Hijet trucks and the Suzuki carry trucks are in high demand.

47 November 2014 TheIrrawaddy ADVERTISEMENT

Kyaukphyu SEZ: Economic Reality or Pipedream?

Winners of special economic zone contracts could decide fate of grand project

By WILLIAM BOOT / YANGON

The development of a special economic zone (SEZ) around Kyaukphyu in Myanmar’s Rakhine State could move closer to reality before the end of the year with the naming of the winners of tenders to develop factories, new housing and infrastructure.

Twelve foreign and domestic firms have been shortlisted by the SEZ development committee, which failed to name any of them in a supposedly open process, but which sources said include Chinese, Singaporean and Indian businesses.

China continues to be seen as pivotal to the successful development of the Kyaukphyu SEZ, despite cooling business relations between Naypyitaw and Beijing.

First, President U Thein Sein’s suspension of the massive Myitsone dam on the Ayeyarwady River upset China and, more recently, negotiations have broken down over the construction of a railway line from Kunming in southwest China’s Yunnan Province across Myanmar to Kyaukphyu.

China and Singapore were the target of recent roadshows seeking to

attract investment in the Kyaukphyu SEZ. The promotion included a sixminute video extolling the virtues of Kyaukphyu, currently an undeveloped backwater where promises by China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC) to provide 24-hour electricity supply to the local population remain unfulfilled, said the Rakhine Social Network Information Center, a local NGO.

CNPC has built crude oil and gas pipelines running from Kyaukphyu through Magway Region, Mandalay Region and Shan State to China, as well as an oil transhipment terminal for tankers docking with oil from Middle East and African suppliers.

Arakan Oil Watch, an NGO which monitors developments around Ramree Island where the terminal is sited, believes Kyaukphyu could become a base for a marine services sub-industry to provide engineering, supplies and maintenance support for the numerous offshore oil and gas exploration blocks recently awarded to a clutch of international companies.

The SEZ promotional video said that the Kyaukphyu SEZ will provide an important Indian Ocean link for China, northeast India and some countries of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN).

PHOTO: SOE

/

48 TheIrrawaddy November 2014

MYINT

THE IRRAWADDY

BUSINESS ENERGY

Construction on Yanbye (Ramree) island in late 2012

“Kyaukphyu is uniquely positioned to serve as a trade corridor connecting these three economies with a combined population of 3 billion people,” the video said. “It will play a vital role in unlocking the potential of the [Myanmar] hinterland.”

A Chinese state-owned firm heads a partnership appointed in March to promote, advise and coordinate the Kyaukphyu SEZ. Naypyitaw named a group led by CPG Corporation of Singapore, however, this firm was bought in 2012 by China Architecture Design and Research Group, China’s largest state-owned engineering design and services company.

Kyaukphyu is seen by China’s strategic planners as a key element of the so-called BCIM Corridor, for Bangladesh-China-India-Myanmar. The BCIM is a pet project of Beijing’s and was promoted by China’s President Xi Jinping on a state visit to India in September.

A pivotal place in the BCIM corridor would be Mandalay, linking Kunming in Yunnan Province with northeast India and on into Bangladesh. But observers also see the BCIM idea as instrumental in facilitating Chinese access to the Indian Ocean.

The BCIM is a grand plan for China to “gain access to multiple coastal zones that are considered crucial for the next-generation Chinese economy,” commented India’s Telegraph business newspaper.

Economists and foreign policy

analysts are divided over whether a Kyaukphyu SEZ is viable in the near term. Meanwhile, work progresses on the country’s first SEZ, with Japanese investment, at Thilawa adjacent to Yangon.

An SEZ around Kyaukphyu would need considerable investment in basic infrastructure such as electricity and new road, rail and port communications.