T R Y

THE SPACE IN BETWEEN

MASTER OF ARCHITECTURE THESIS THE UNIVERSITY OF SYDNEY School of Architecture, Design and Planning Isabella Harris

W O M E N H E A L I N G W O M E N H E A L I N G C O U N

This Studio Thesis is submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the Master’s of Architecture, University of Sydney School of Architecture, Design & Planning.

This certifies that the contents of this studio thesis, to the best of my knowledge, is my own work and has not been submitted for any degree or other purposes. I also certify that the intellectual property for the content of this studio thesis along with curated artefacts (images, photographs, drawings and the like) are the work of the author unless otherwise stated.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are warned that the following thesis may contain images and references to deceased persons.

This thesis also references information on intergenerational trauma and family/domestic violence, alongside profiles of victim-survivors.

3

P E R S O N A L A C K

T

I would like to express my gratitude to the Mudgee Local Aboriginal Land Council for their openness to engaging in and with this design project. In particular, I wish to acknowledge Aleisha Lonsdale for her ongoing sharing of knowledge, vision and time throughout the codesign process. Mostly, I am thankful for the relationships forged within this codesign process and the experiences these have created to build my understanding of Aboriginal culture and wisdom. This knowledge will remain with me as I transverse Country, both as participant and designer.

I am also grateful to the Mudgee and surrounding community (service providers and individuals) for the participation and perspectives offered when gathering insight to the project ambitions, within the realities of a regional context. To the women who shared their stories and experiences of trauma- your courage and voice has been instrumental in bringing this project design to where it sits today.

I want to express my gratitude for the direction, advice and encouragement given by Dr Chris Smith and Dr Michael Mossman, of the University of Sydney School of Architecture, Design & Planning, during this Master’s Studio Thesis. I also acknowledge the guidance of the Architecture and Design Faculty through past stages of research, which have informed this project.

My award of the Sibyl Leadership Grant from The Women’s College, University of Sydney, enabled to be present within community and engage authentically in the codesign process with Mudgee Local Aboriginal Land Council.

I would also like to thank my partner Nathan and mum Kate, for their continuous support, patience and belief in me, over the past five years.

5

N O W L E D G M E N

A C K N O W L E D G M E N T O F C O U N T R Y

For generations, the traditional custodians of my project site, Mudgee (Moothi) have lived an abundant and sustainable lifestyle. I acknowledge the Wiradjuri Nation and the Mowgee peoples, among all Aboriginal peoples, and pay my respects to the Elders past, present and emerging for their ongoing care of these lands and waterways.

As traditional owners of the Munna Reserve, the Mowgee peoples for thousands of years, have thrived within the many reaches of this ecosystem. I recognise this land was, is and always will be Aboriginal Land.

On these lands, I recognise the changing and evolving nature of Country and the ways in which local First Nations communities and their ecologies have responded and adapted to these changes throughout time.

Country is a living, breathing entity with an enduring Spirit, which informs the environment we design with now and into the future.

7

D E S I G N B R I E F

Regional NSW offers a site to explore diversity in unity and multiple co-existing relationships with community and country, while co-envisioning healing spaces. Travelling from the assumed known, we engage in reflexive processes, working with opportunities to address the tension and complex histories, internal /external, macro /micro, visible and felt. Your designs become contributors to the collective consciousness through a holistic awareness of systemic design principles located in this contemporary social movement of transformation. The project calls for the conceptualisation of catalytic cultural hubs including and not limited to; education, creative, gallery and exhibition spaces for engaged community dialogues surrounding regenerative issues.

This thesis studio aims to provide an architectural offering for healing (theory to practice) to the regional community of Mudgee, acknowledging the crucial nexus of national cultural issues, intergenerational violence/trauma of First Nations peoples and the public health crises of domestic violence, specifically against women and children in rural New South Wales. Co-envisioned and codesigned with the local Wiradjuri Community, artists, victim-survivors and practitioners, The Space In Between, poses a perspective to real, complex, uncomfortable issues and histories, macro and micro, and presents an opportunity to heal through relationships, built on common and shared experiences. These experiences are diverse, authentic, purposeful experiences of coexistence and nourishment; women healing women, healing Country. The Space In Between is a vision for voice, treaty and truth for women and children outside of an urban context, on Wiradjuri Country in Mudgee NSW. It draws on the knowledge of all women across Country, to advocate for and incite, through intimate reciprocal relationships with all matter, healing and regeneration.

The thesis draws on my previous research, Then, Now, Next, Rediscovering Future Design: Rediscovering opportunities for ultimate design. Realigning human centred design through the construct of the womb, 1 which looks toward ecological flourishing through experience, as opposed to objects in an architectural space; the opportunity to build a responsive and responsible culture of architecture. One which sustains all in our ecology. It presents a call to foster pertinacious action of care and to imagine every opportunity to seek spaces in between for new learning.

The previous research centred on experience and relationships within the womb facilitates the research of this body of work. Learnings and unlearnings, through a slow procession toward architectural clarity, are established through the wisdom and voice of landscape, Aboriginal people and community to inform the design. The programs of a Women’s Housing Community (temporary housing), Wellness and Knowledge Hubs and a Community Exchange situate the cruciality of engendering intimate and responsive placemaking, through reciprocal relationships and experiences of knowledge and nourishment, to flourish. This design process intends to provide insight to a experiential framework for architectural design and architectural response, as a catalyst of hope, for healing across the broader micro and macro communities of our nation.

9

A B S T R A C T

C O N T E N T S

Key Terms 13 Preface 14

Introduction 17

How did we get here?

Project Framework: The Womb, The Nest, A Basket 20 The Womb 23

Concepts and Theory: Experience Over Object

The Nest: Fragments of Learning 27

Fragment 1: What We Know 28 Research Methodologies 29 The Research 30

Intergenerational Trauma & Family and Domestic Violence

Fragment 2: Context of Time 36

Fragment 3: Site Analysis: Munna Reserve 47 Location

Fragment 4: Flora + Flora Assemblages 50 Environmental Report Geology

Biodiversity Services

Fragment 5: Materiality 60 Mycelium Bricks Rammed Earth Glass Innovations

What Became Known 70

Fragment 6: Qualitative Data 71 Survey Interviews

Housing Plus Mudgee Community Health Health Professional Community Co-Design with Mudgee Local Aboriginal Land Council Establishing the principles

Fragment 7: Ethnographic Research 78

Journey Maps of Victim Survivors

A Slow Procession Of Possibility 91

Fragment 8: Emu In The Sky 92

Fragment 9: Moments With Country: Prospect + Refuge 96 Mapping

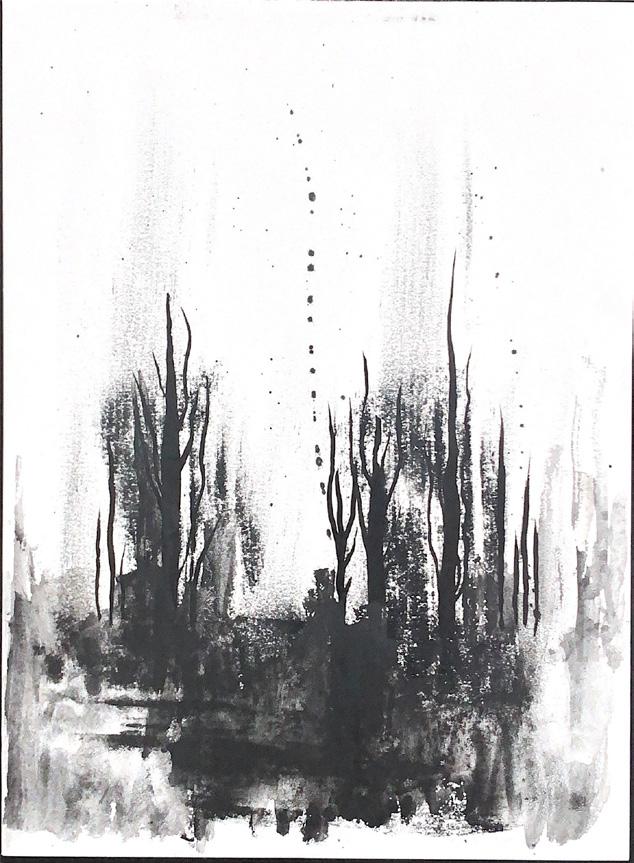

Atmosphere of Place 104

Fragment 10: Stillness + Sitting 105

Learning, Unlearning & Affirmations 108 Stakeholders Conceptual Statement Principles

Aboriginal Led Trauma Informed

A Basket: An Architectural Response 118 Initial Schema Concept Models

An Iterative Process: Capturing Moments The Project At This Point Schema Women’s Community + Housing The Space In Between Women’s Wellness + Knowledge Hub, Administration Hub and Community Exchange Women’s Wellness + Knowledge Hub Administration Hub Community Exchange

New Design Considerations

Weaving + Yarning 188 From Now to Next 194

This thesis is a holistic representation of the process undertaken from concept to architectural response. To honour the extensive research and both the procession on and with Country and the relationships developed with stakeholders, all documentation has been curated within. It is encouraged that you, as the reader, review the document in its entirety. Alternatively, you may choose to read the Learnings, Unlearnings and Affirmations review, at the conclusion of the Nest Phase. This will provide insight to the knowledge gained through the research, informing the architectural response.

Additionally, curated field notes, survey data, interview transcripts and digital representations are made accessible via a website. Please scan the QR code at end of the thesis.

11

K E Y T E R M S

Domestic Violence:

This thesis will use the term ‘domestic violence’ when referring to any and all forms of violence/abuse in intimate partner relationships and family relationships/households. There are many terms in the Australian landscape, many of which definitions overlap, when working in this sphere. Domestic violence is the most commonly used in the media, at this present time, and has had greatest social awareness. Using a term that is known by most, is integral to raising awareness of the public health crisis Australia as a nation faces.

Intergenerational Trauma:

This thesis uses the term to discuss the intergenerational and transgenerational impacts of traumatic experiences; specifically of the impact of colonisation on First Nations peoples. This term also extends to the affects of domestic violence for Indigenous and non Indigenous women and children.

Womb: Phase one of the thesis; a conceptual architectural framework developed from previous research. The Womb is presented as the archetype for future design.

Nest: Phase two of the thesis; a fragmented research phase

Basket: Phase three of the thesis; the design project development from the Womb and Nesting phases- an assemblage of fragments.

The Space In Between: is a common or collective shared space of experience and engagement between and with all matter.

Country: The term used by Aboriginal peoples to describe the lands, waterways and seas to which they are connected. The term contains complex ideas about law, place, custom, language, spiritual belief, cultural practice, material sustenance, family and identity.

Healing: The process by which acceptance, acknowledgment, truth and regeneration take place for all to flourish.

13

“On almost every front, our world is under enormous stress. We are not at ease with each other, or our planet.”2 UN Secretary-General António Guterres

In 2020, during COVID-19, I returned from university, to my home in regional NSW to undertake my studies and find comfort and solace, in what I knew and what was known, amongst the societal chaos and growing uncertainty for the future. I was able to experience nourishment, an intimate spatial experience of place, drawn from my memories and fragmented moments of conscious and unconscious being, carried from the relationships I had formed over time. Relationships with all matter; My family, the sentience of their nearness in all forms of manifestation; a consolation.

My garden, constancy in the abundant supply of odd shaped vegetables and ripened fruits; the intertwined branches of the plum tree just beyond the house- a playground to the wrens, providing hours of screen time, whilst I stretched my still legs beyond the boredom boundary of my bedroom window. Sweet orange syrup cake, handmade gnocchi and the family tradition of secret sauce making. Cockatoos screeching in the late afternoon, worn, chipped tiles on the fire hearth; scars of familiarity And images of my grandfather preparing for a wintery night. Then, the sunlight that perches at the edge of my bedding, edging toward my pillow on the crisp, frosty mornings of July.

Amongst these moments during COVID-19, I peered in to view the reckoning across our globe, our nation; an interlude to a moment in time that united all humanity temporarily within a space, for just a breath. Here, vulnerability to nature within our shared ecological sphere was apparent. Within that sphere, it was, as it has been, the marginalised, who were most impacted and continue to be

P R E F A C E

impacted by the economic and health implications of that crisis, in the short and long-term. Whilst COVID-19 may have provided an awakening for some, our global community has been a silent audience to divisions and inequalities throughout time and continues to do so.

It was at this time that I began to reflect deeply on the role “architecture has played in this production,”3 and to question how we arrived in this socio-cultural and socio-political space. My own personal experiences of family and domestic violence and growing up in regional NSW, consciously and unconsciously, had anchored my interest in architecture, for its propensity to create a spatial justice ambition focused on inclusion, accessibility and experience.

And so, in the wake of COVID-19, in 2020, I began my journey to seek knowledge and understanding about our beginnings in order to understand our future, through an architectural lens. In this process, I undertook research, which contributed to the beginnings of my Honours Thesis: Then, now, next, rediscovering future design: Rediscovering opportunities for ultimate design & Realigning human centred design through the construct of the womb 4 Triangulating of Philosophy, Science and Architectural Theory, which as a speculative theory, became a catalyst for further personal research focused on the ancient knowledge of Aboriginal peoples and culture to inform sustainable design practices. This research postulated that the creation of inclusive design manifests through collective relational experiences, between all matter, in the common space between our differences, The Space In Between. This previous research has informed this Master’s Thesis and is a continuation of knowledge sharing and relationship in a codesign space, to create a new architectural narrative.

15

N T R O D U C T I O N

How did we get here ?

We live in a society, built on a patriarchal hierarchy where socio-economic stance is and has been the most valued commodity of the western world. It is a space where it seems less important for people to know who they are, or to value connectedness with and within spaces, than to know where they are within the status-quo, creating inauthentic spaces and place-making. Capitalism and consumer-centric lifestyles have historically resulted in socio-cultural, sociopolitical and environmental injustices-such as poverty, homelessness, racism, domestic violence, intergenerational trauma and climate change. Our global and local experiences of connectedness have “been created in part, by globalisation, but it is globalisation, which is driven by a patriarchal society and capitalism.”5 This ideology is focused on objects; personal wealth over experiences of wellness and health. These norms (socio-cultural/political/economic and environmental) have created binary divisions between our ecologies, human and environmental (living and nonliving), resulting in spaces of exclusion, locally and globally. “When binary oppositions become the focus, a universal societal view becomes inauthentic and inequitable. Diverse ideals, values and people, identifying outside the binary pairs, or deemed inferior within the binary pair, are not considered or acknowledged in terms of their needs and consequently are marginalised”6 by society and community spaces. This exclusion is the dis-ease of an engineered society.

Whilst Australia is geographically distant from the rest of the world, the impacts of societal and environmental neglect, alongside the COVID-19 pandemic are mirrored in our own national ecology; the desecration of First Nations people and Country, as a direct result of colonisation. The stories of disillusion and experiences of trauma and generational suffering for the marginalised of our communities and of Country. Aboriginal people of Australia, the custodians of Country, the Wiradjuri Nation and the Mowgee people of Mudgee, alongside Country itself, have suffered atrocious acts of violence, desecration and torment at the hands of a patriarchal society. For First Nations People, the long term impacts of this treatment, (these truths) are present today in, high rates of incarceration, child removals, youth detention, poverty, drug and alcohol addiction and domestic violence. For our environment, for Country, the devastation is evidenced in the ecological responses of climate change and extreme weather markers.

On reflection, we are reminded that sovereignty has never been ceded. The Uluru Statement from the Heart (2017)7, is a transformative, urgent call to all Australian people, for the recognition, voice, treaty and truth of Aboriginal Peoples. It distinguishes three extremely important proposals, which

17

I

have been previously noted in historical artefacts8 and which are not too much to ask:

1. A First Nations Voice enshrined in the constitution

2. A Makarrata9 Commission and

3. A process of truth telling.

It is intended that these proposals will see future reforms of treaty and truth and constitutional rights of First Nations People. Whilst the current federal government, under the leadership of Prime Minister Anthony Albanese, has recognised the call publicly (May 2022), only time will tell of such resolve. Australian political history has shown on many occasions such calls are met with ‘red tape’, dismissal, ignorance and disregard.10

The Uluru Statement, full of collective spirit, prompts us as people, as Australians, as designers, to engage deeply and listen carefully to First Nations peoples as the true custodians of the land on which we taken. This priority is furthermore highlighted as our world ecology continues to face the conflux of ongoing crises that threaten the very being of all. The Sustainable Development Goals Report 202211 by the United Nations state that, the “2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development is in grave jeopardy due to multiple, cascading and intersecting crises.”12 COVID-19, climate change and conflict dominate the space of now and their impacts, that of our future. “To put the world on track to sustainability will require concerted action on a global scale.”13

Therefore, “the dismantling of the western canon and patriarchal values is essential for the future of our society and environment; our existence.”14 A critical shift in ethics (socio-cultural/political/ economic/environmental) must be grounded in experience over object, as presented in Harry Francis Mallgrave’s, From Object to Experience: The New Culture of Architectural Design 15 This thinking will be explored through architectural response, as the convergence of fragmented knowledge in the research phase between and with the Aboriginal community and various stakeholder groups identified. Looking forward, protecting the vulnerable and marginalised of our communities, macro and micro is an essential priority. Women and children continue to be at the forefront of socio-cultural inequities and violence.16 “Women and girls experience the greatest impacts of climate change, which amplifies existing gender inequalities and poses unique threats to their livelihoods, health, and safety.”17

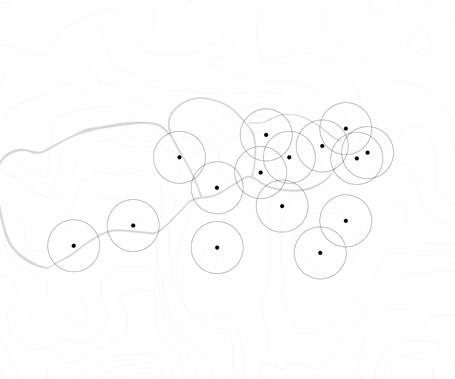

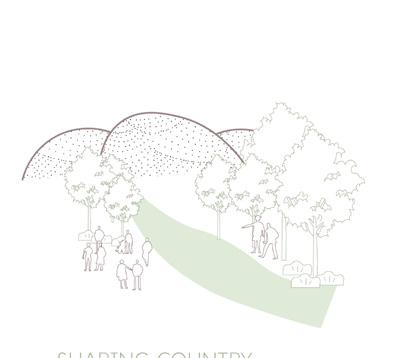

Anticipating change is borne from knowledge attainment and is pivotal in all aspects of architectural design, across the arts, science and humanities fields. How will we use past knowledge to anticipate our survival given the benightedness of our western society? Acknowledging, drawing and acting on the wisdom of our First Nations peoples, the keepers of Country, is critical to move us to an informed and considered mindset of stewardship for our sustainable future. Codesign is centric to this project and an initial step toward healing Country and the community of Mudgee. Codesign is a process undertaken throughout and beyond the project to build authentic opportunities for change through shared vision, knowledge and responsibility. The process of codesign with Mudgee Local Aboriginal Land Council is represented in adjacent diagram…

This thesis studio, grounds itself in regional NSW and aims to situate the truth about the injustices and trauma faced by women, throughout time, to dismantle the narrative of His-Story, through The Space In Between; a space of inclusive, relational experiences, which nourish and heal. It is essential that architectural activism is centred through reciprocal relationships with Country. Here, Aboriginal voice, courage, culture and knowledge sharing are asserted and authored, through respect and agency of codesign, and will engender healing through intimate and responsive place-making.

Codesign is a generative process built on shared knowledge and lived experiences. Respectful engagement of critical stakeholders, as equals, is situated as the central nexus for this project, as authentic codesign.

19

The relational elements of Womb, Nest and Basket, are symbolic representations, which form the framework of project procession, through fragmented phases of theory, conceptual thinking, research, experience and design. Each is integral to the curation of what is known and what we know, to envision new catalysts of opportunity in relational design, for all to heal and flourish.

The Womb, centres the theory phase and presents the concept of the womb, as an archetype. An inclusive space of relational experiences, identified as The Space In Between. These experiences build on previous fragments and moments that form our identity, either inherited through DNA, epigenetics, or lived through sensory engagement, memory and atmosphere; all anchored in a relationship of coexistence and function. This phase establishes what is known about the womb and its phenomenology, as a collective archetype, creating contextual experiences and is based on previous research presented in my Honours Thesis.18

The Nest phase predominantly represents the merging of research methodologies and subsequent data; historical, cultural, social, scientific and ethnographic in nature. Indigenous histories, cultures and oral storytelling are centric to this project and enabled through knowledge sharing and the codesign process with Mudgee Local Aboriginal Land Council. Like the assembly of a nest, the research combines fragmented elements of lived and inherited experiences. What is known at a macro level of the socio political, environmental and cultural sphere, alongside what we come to know at a micro level, through engagement and deep listening to all stakeholders, human and non human.

The Basket represents the design phase; the architectural response and programs informed through the previous phases of the Womb and the Nest; the fragments of theory, philosophy and research and the relationships forged in this ontological space. It weaves the fragments of being and knowing, of deep listening, voice and imagination, for what it can become to one and many: intimate, responsive and healing place-making.

P R O J E C T F R A M E W O R K: T H E W O M B , T H E N E S T A N D A B A S K E T

21

T H E W O M B T H E N E S T A B A S K E T

T H E W O M B

“To look back to our past and the spaces of our collective beginnings as humans, is to look to the womb.”19

If we look back to our very beginnings, our genesis, we look to the space of the womb. An archetype to flourish, which all humans are with and within.

23

My previous research, Then, Now, Next: Rediscovering Future Design,20 explored the world and spaces in which we inhabit, design and coexist; spaces that are patriarchal, capitalist and consumer-centric, creating divisions and binaries amongst the local and global.

A space of inclusivity, the womb does not discriminate against sex, gender, race, religion, socioeconomic or socio-political status. Rather, it provides a triadic space of function, coexistence and nourishment and at the core of their intersection relational experiences as depicted in the below image. As an archetype, the womb provides for the collective needs of all humanity and through reciprocity to individual needs of the fetus, as responsive engagement. In the initial collective nexus, the womb is a common spatial form that exists in between our conception and birth, despite and between our differences.

The significance, in light of the context of experiences of trauma (intergenerational and domestic violence) is that, “the womb must be acknowledged in order to reclaim its prominence in a metaphysical time, as the sphere of modernity, amongst the dis-ease of societal psychosis.”21 Placemaking, like the centric anchor of the womb, creates spaces to which we gravitate. Places which provide security and where our well being is optimised. Sources of truth. Places where we are accepted and what we know about ourselves forms part with and within our unconscious and conscious selves- a containment of knowing and unknowing. We are all formed and develop within a womb. We are born from a womb. The womb harnesses and preserves life.

As a conceptual persuasion for inclusive design, the womb focuses on experiences (over object) which nourish through reciprocal relationships and the purpose of space. Supported by the research of Kristen Myers and David Elad, in Biomechanics of the Human Uterus, 22 “the womb adapts to the demands of the developing human and is endogenous in nature. It provides an adaptable interior environment, responsive to the needs of the fetus, as well as providing protection through its biological and physiological forms.”23 It is an ecology that creates identity through sensory experiences, deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA24), genomic imprinting25 and the socio-cultural lineage of parents- inherited experiences of memory, such as trauma and known as epigenetics.26

These fragments, relational experiences lived, inherited consciously and unconsciously, create our identities, yet in order to understand identity and flourish as an ecology, all must be anchored in relational experiences of knowledge and nourishment, known herein as, The Space In Between.

T H E W O M

B

“To truly know ourselves, we must first know and celebrate each other, our humanity, our earth. To be with and within, we must focus on experiences of inclusion. Nourishment and coexistence, over the object, which defines and excludes. For, as we teeter together, on the edge of potentiality, as designers, from theory to practice, everything is possible, in The Space Between.”27

The Space In Between is one foregrounded in reciprocal relationships. It is the common or collective shared space of experience and engagement, between and with all matter. In architectural terms it establishes experiences of knowledge and nourishment, as opposed to the object, created through architectural responses to stakeholders (human and non human), as centric to responsible and sustainable design. Living systems make sense of the world through relationship and emotion and thus, as depicted by Mallgrave, “emotion becomes integral to perception and action,”28 a cognitive process which induces memory making and cognitive responses to place-making. In Indigenous cultures kinship and relationship to all, centres cultural traditions of story through songlines in the space in between now and then. In First Knowledges: Songlines, The Power and Promise, 29 Margo Neale states the significance of relational knowledge to Aboriginal identity. “Songlines are foundational to our being- to what we know, how we know it and when we know it.”30

The Space In Between reimagines opportunities for building a shared efficacy toward healing. It bridges the dis-ease, dis-stance and dis-connectedness between dualisms or binary oppositions, created through the western cannon of patriarchy, capitalism and marginalisation. It postulates the space between objects and moments in time and place, where experiences are created.

In this thesis design project, Women Healing Women, Healing Country draws on the convergence points of relationships in The Space In Between throughout the process. That is, the space of codesign with Mudgee Local Aboriginal Land Council (MLALC), between concept and program and the shared experiences of trauma experienced by women (Indigenous and non Indigenous). A space where understanding the commonalities of trauma and violence (scalable, e.g. domestic to national) allows for the development of connections in which individuals, families and communities are enveloped and can heal through relationships, Country and culture.

As living entities, we are relational beings. Creators of our stories, shared and personal. We are keepers of the moment, of moments and experiences which define us, which are with and within us. These experiences create knowledge which enable us to flourish. “We need to move from our insular defining spaces, to venture into our common space. To align the naturally mirrored and common ecologies of the womb and earth. To unite for the survival of life.”31

25

H E S P A C E

N B

T W

N

T

I

E

E E

The Space In Between

27

T H E N E S T

T H E N E S T: F R A G M E N T S O F L E A R N I N G

What We Know- Historical & Scientific Research

Like the assembly of a nest, the research combines fragmented elements of lived and inherited experiences to be shared. The nest, much like the womb, provides nourishment and agency through intimate relationships of refuge and prospect and knowledge building. Nests remain and provide an ontological space for other birds and species, local use & reuse of materials creating stewardship. Reciprocity of relationship within the ecology is paramount.

Research and experiences, much like the composition of the nest inform: identity- inherited (DNA and epigenetics) and lived (memories), conscious and unconscious, place-making and decision making. These shape our being and engender relationships to connect, empower and heal.

R E S E A R C H M E T H O D O L O G I E S

A hybrid approach to knowledge creation and explorative design, intertwines quantitative qualitative research methodologies to bridge the gap of complexity between what is known and unknown, to what became known. This thinking explored by David Wang and Linda Gorat in the text, Architectural Research Methods, and known as “Experimental and Quasi Experimental Research.”32 This form presents the anticipation of what lies ahead and what is happening in the precise moment. This project draws on such an approach, whereby a range of research methodologies, inclusive of a thorough literature review, were undertaken to develop insight into the experiences and impacts of trauma (intergenerational and family and domestic violence), alongside building authentic knowledge of the site and about Indigenous histories and cultures, environmental understandings and relational engagement with stakeholders-human and non human. The research undertaken included historical, scientific and environmental research, historical and contemporary oral storytelling, qualitative and quantitative data sets and ethnographic studies, through interviews and procession on site, over thirteen weeks. The research sits in parallel with future focused reports such as the international United Nations Sustainable Development Goals33 and the National GANSW Designing With Country Paper 34

Ethnographic Participant Reference

Participant 1

Housing Plus Mudgee Staff Member

Participant 2

Mudgee Community Health (MHC) Care worker

Participant 3

Psychologist and Health Care Professional

Participant 4

Participant 5

Participant 6

Participant 7

Participant 8

Victim Survivour “Jessica”

Victim Survivour “Emily”

Victim Survivour “Lucy”

Victim Survivour “Tia”

Victim Survivour “Gemma”

29

T H E R E S E A R C H

Intergenerational Trauma & Family and Domestic Violence

“The control and abuse never ends. …The other day I posted a photo at a cafe having lunch and tagged the location so people knew the last place I was in case something happened to me. I try to validate my child constantly, teaching him to break the cycle and that it isn’t his responsibility to keep both of his parents happy. ……The physical distance between him (ex-partner) and I has done wonders for my mental health, but I still feel unsafe. It’s ‘when’ something happens, not ‘if’. I am in constant fear that he will do something to me.” Participant 5, Victim Survivor35

A local community survey, Gathering Insight: Family and Domestic Violence in Regional NSW,36 of Mid-Western Regional Council residents, was conducted between August-October 2022, to gather insight into availability and utilisation of family and domestic violence services, experiences of the services and to gather data related to needs of victim survivors in short and long term circumstances. In addition, Interviews37 with service providers, members of the Mid-Western Regional Community, and representatives of the local Aboriginal community, were also undertaken to establish a broader context of understanding. Data which supports the research below is represented statistically and as annotations within the text boxes below. Complete survey data and interview transcripts are accessible through the Project Digital Archive.38

Domestic Violence in an Australian context is nothing short of a public health and welfare crisis. Women and children are disproportionately victims/victim-survivors to domestic violence, with First Nations women, women with disabilities, pregnant women and rural/regional women, more likely to be victims to domestic violence, as highlighted by Anne Summers in her report, “The Choice: Violence or Poverty.”39 Statistics from a report by the Domestic Violence NSW Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Women’s Steering Committee40 also indicate that domestic violence occurs at higher rates in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities than in the general population, with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women are thirty four times more likely to be admitted to hospital for family violence related injuries and five times more likely to be victims of homicide, as a result of domestic violence than non-Indigenous women. The report by Summers,41 also indicated that domestic violence is the leading cause for homelessness amongst women and children.42 Although the conversation around domestic violence in Australia is gaining traction, these conversations are not at the forefront of constitutional reform, policy making and provision of services.

Interviewer: How does Mudgee Community Health (MCH) engage authentically with the Indigenous community in regards to providing services for domestic violence?

Participant 2: We don’t see as many Indigenous clients as non-Indigenous clients. Unfortunately, MCH doesn’t have a dedicated Aboriginal health worker position. The Integrated Care Worker covers Indigenous communities around the area. Also none of the community services in Mudgee have particular Aboriginal programs, which is concerning.43

Women and children from all backgrounds, experiencing intergenerational trauma and domestic violence in regional Australia, face multiple and specific contextual challenges, incomprehensible to those in urban settings. Isolated and within small communities, access to sufficient support and services is inadequate and inconsistent, leaving many women destitute, homeless, financially unstable and unable to provide for their children. More often than not, these women return to a domestically violent household in order to survive44; the paradox of safety and survival. Many surveys, interviews and reports45 identify that the women and children of rural/regional Australia, dealing with domestic violence, are continuously subject to inadequate support and access to services; when there are services available, they are either limited, have long wait times, or are not specific to their needs. Often there is a lack of information or misinformation in the community about the types of support available, with many women unaware of what may be available to them. This is often exacerbated by the stigma associated with domestic violence and the reluctance of victims to ask for help, in fear of future implications to their safety, wellbeing and social engagement.

Participant 3: Domestic violence services often can’t help people with exactly what they need. And they will often say that. Unfortunately, I have sent clients to these services and they have had little to no assistance.46

Survey: 42.3% of those surveyed stating they did not seek domestic violence services because:

“shame-not wanting people to know”

“I am unable to get there and don’t have access to a phone of my own and when I called the police once , I was taking my life into my own hands.”

“I attempted to find help but wasn’t sure where to go”47

Survey: Of those who did access domestic violence services 62% disagreed or strongly disagreed that their needs were met.48

31

Furthermore, a recent report from ANROWS titled, A deep wound under my heart: Constructions of complex trauma and implications for women’s well being and safety from violence, 49 identified that “In Australia, one quarter of women subject to gendered violence report at least three different forms of interpersonal victimisation in their lifetime…Being exposed to multiple, repeated forms of interpersonal victimisation may result in complex trauma, which involves a range of traumatic health problems and psychosocial challenges.”50 Intergenerational trauma and the interconnectedness of lived experiences are formed in the realities of genocide, outlined by Tanya Tarlaga in the text, All Our Relations: Indigenous trauma in the shadow of colonialism.51 “We have come from a history of genocide, and genocide is about the deliberate annihilation of a race…It is trauma on a more massive scale-psychologically, physically, spiritually, culturally.”52

Generally, women experiencing intergenerational and complex trauma, are often expected to manage a siloed approach to accessing services, which is often difficult to navigate, financially inaccessible and lacking in personal care. Amongst the key recommendations of the ANROWS report was a need for coordinated and consistent services, as essential in providing support for women in these circumstances and the embedding of “trauma-informed care within a holistic wellbeing framework that integrates mental, physical and psychosocial wellbeing.”53 The implications of intergenerational trauma for children is, according to Taralga, “...characterised by normative instability…They are born into social exclusion and are not only at risk of suicide, they also face higher rates of sexual abuse and self destructive behaviours.”54

Survey: 80.8 % of survey participants indicated that they expected centralised services to be included in a Women’s Refuge and educational centre, with 69.2 % of participants indicating that consistency was fundamental to their current and future needs.55

“There is a missing link between I need to leave now and I have somewhere safe to go.”56

In 2016, the Personal Safety Survey (PSS), referenced in Summers’ report, stated an estimate of “275,000 Australian women suffered physical and/or sexual violence from their current partner. Of these women, 81,700 (30 percent) had temporarily left the violent partner on at least one occasion but later returned. Mostly they returned because they still loved their current partner, wanted to work things out, or the partner had promised to stop the threats and the violence (69,000 or 85 percent). But for around 15 percent of these women (12,000*), the reason for returning was that they had no money or nowhere else to go. Returning to their violent partner seemed a better option to being homeless or trying to subsist in poverty.”57 The choice for women fleeing

domestically violent environments is unfortunately limited; to flee and more than likely become homeless, or to stay and continue to face the violence. This ultimatum is exacerbated by location and contextual resources; fundamentally, women in regional areas have nowhere to go.

Interview with Housing Plus Staff58

Interviewer: What housing options are available in Mudgee currently for women and children facing domestic violence?

Participant 1: None. There is nothing at the moment. The closest housing option is in the Blue Mountains or Orange. Dubbo and Forbes are average.

Interviewer: So a minimum of 2 hours away to access any housing options.

Participant 1: There is one short term housing stay in Bathurst, well Kelso, but it is always occupied.

Interviewer: And that’s still 1 and half hours away.

Interviewer: What sort of support is available at the moment through housing plus and other services?

Participant 1: We are working out more affordable housing options, introducing support for workers for budgeting and up-skilling. In 2016 the Women’s Domestic Violence court fund started. Prior to this, women were having to report abuse and return to an abusive household.

Interviewer: Yes, this was exactly the experience my mum and I had back in 2014.

Participant 1: Yeah there were no support services back then, I mean there still isn’t a great deal now due to state funding and business capacity. Housing Plus is more a referral service rather then a case management service. There are so many gaps along the journey.59

Hannah Robinson’s article, “No one will hear me scream: Domestic Violence in regional, rural and remote NSW,”60 highlights the severity of domestic violence in regional areas.

“Across Australia, people living in regional, rural and remote communities are 24 times more likely to be hospitalised as a result of family and domestic violence than people living in major cities.”61

Mudgee, on Wiradjuri Country, ‘a nest in the hills’, the picturesque weekend getaway, world class wineries, a hidden secret; part of the Orana Region, one of two communities with the highest rates of family and domestic violence for any geographic region in New South Wales.62 These regions also have the highest numbers of domestic violence incidents occasioning grievous bodily harm.63 According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics,64 in the period between July 2017 - June 2018,

33

there were 599.3 domestic apprehended violence orders (AVO) rate per 100,000 population in the Mid-Western Regional Area (Mudgee local council area) compared to 307.8 domestic apprehended violence orders (AVO) rate per 100,000 population in Sydney.65 Coming out of the COVID-19 pandemic and with greater awareness and voice around domestic violence, AVO statistics have increased across the board. Between June 2021 - July 2022, there were 686.3 domestic AVOs rate per 100,000 population in the Mid-Western Regional Area and 358.1 domestic AVOs rate per 100,000 population in Sydney.66

“As a psychologist and with my professional career history, I think there is a societal responsibility to rehabilitate men, who more often than not are the perpetrators, as well.”67 Participant 3-Health Professional

Participant 2: At the moment, we don’t have an early intervention service, but Dubbo and Bathurst do. I provide domestic violence support, to mostly women and children. We do have counselling services and within Community Health there are mental health services but domestic violence is not their core focus.

Interviewer: What specific domestic violence services are provided?

Participant 2: **** and I run a domestic violence group called Sharkcage. It is an 8 week educational program. This is for people who are safe and want to learn about types of abuse and rights in an effort to educate people about abuse.

Interviewer: So there is a gap between leaving a violent situation and reaching a stage like attending Sharkcage. What sort of housing options do MCH refer people too?

Participant 2: The accommodation thing is a massive issue. It’s ridiculous, there is no refuge, people often have to leave town. Closet refuge used to be in Katoomba or Bathurst. There are a few community members that are interested in the social and affordable housing sphere but haven’t had much traction.68

The comparison between rural and urban areas in this context highlights the need for accessible services in regional areas to be of equal quality and quantity to that of urban cities. The urgency consolidated in the survey data and interview transcript.

Survey: 52% of respondents said they had accessed domestic violence services, however 94% of these respondents stated that the services they accessed were in fact inadequate, unhelpful and they had to push for any support.69

Interviewer: And how long is the waiting time for any accommodation?

Participant 1: How long is a piece of string? Where are you applying for, what type of property are you needing? It is endless.

Interviewer: Yeah wow okay. What is the process to access housing?

Participant 1: You used to be able to just rock up to the refuge, hop on a bus or get on a train. People are often reliant on relationships between other services. Now, you have to present yourself to Barnardos. They then make an assessment of your situation and will refer you on to particular service providers. It’s all about the assessment.70

35

C O N T E X T O F T I M E

Every moment in time sits in the context of now, with wisdom built on yesterday, in the anticipation of tomorrow.

For the people of the Wiradjuri Nation, time is not measured in linear form, but rather circular, without a beginning or end. Time is situated by events within the context of now, a space of considered focus.

D R E A M T I M E

Dreaming is part of social, religious, political and economic life for Aboriginal people as referenced in First Knowledges: Design by Alison Page and Paul Memmott.71 The knowledge, values, traditions and law are shared through oral histories, storytelling, ceremony, dance and song. This knowledge provides a structure, which sits in the present and by which, Aboriginal people view and interpret the world.

During the Dreaming, ancestral spirits, who appeared in many forms, came up out of the earth and down from the sky to walk on the land, as travelers and hunters and with consideration, they carved the land formations across Country. They also created all the people, animals and vegetation that were to be a part of the land and laid down the patterns their lives were to follow. These spirit ancestors gave Aboriginal people the lores and customs of their culture. When their work was completed the ancestral spirits went back into the earth, the sky, the waters, in diverse forms appended to their people. Dreaming stories form part of Songlines, the knowledge system of Aboriginal people today.72

To the Wiradjuri people, Baiame is the creation ancestor and the Skyfather. He is seen in the Orion constellations of the night sky. He descended from the sky to land and gave form to the land, creating rivers, mountains and forests. He also gave Aboriginal people their laws, traditions and culture. There are many dreaming stories about Baiame, associated with different clans across Nations and all Aboriginal people.

37

FRAGMENT

2

T R A N S N A T I O

N A L

From the earliest of times, people have used the sky to ground their spirituality, cultures , thinking and values. “Constellations: common global meanings”, Cosmos Magazine73, represents this as, “Constellations of stars have assisted people in shaping their own ongoing narratives and cultures to make meaning of life on the land. Even though we live under one sky, we all do not see the same sky, at the same time.”74

The constellations however, are what connect all people, all matter. Common patterns between Greek and Aboriginal cosmology, such as Orion and Baiame, create relationships through story and symbol.

N A T I O N A L

Baiame is the creation ancestor and the Skyfather for many Aboriginal people and their Nations. He is seen in the Orion constellations of the night sky. He descended from the sky to land and gave form to the land, creating rivers, mountains and forests. He also gave Aboriginal people their laws, traditions and culture.75 There are many dreaming stories about Baiame, associated with different clans across Nations and all Aboriginal people.

January 26th, 1788 marks a time in history of devastation, for First Nations people, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders. Captain Arthur Phillip of the British Royal Navy, as commander of the First Fleet, led 11 ships into Botany Bay, New South Wales. Sydney Cove in Port Jackson became the first site for colonisation and violent conflict, disease, displacement and exile for the people of the Eora Nation.

39

U R B A N

The Wiradjuri people are known as the people of the three rivers: the Wambool (now known as the Macquarie River), the Galari (the Lachlan River, from which the electorate takes its name) and the Murrumbidjeri (the Murrumbidgee River). Wiradjuri country is the largest in NSW,and the second largest within Australia as indicated in the AIATSIS “Map of Indigenous Australia.”76 The “Gugaa” (Goanna) is the overarching totem for the Wiradjuri Nation. It is the symbol that connects all people, past and present, of Wiradjuri land. For the Wiradjuri people the Emu in the Sky has great significance to the way they live and engage with Country.

“Many aboriginal groups across Australia recognise the ‘Emu in the Sky’, a dark figure stretching across the Milky Way…The emu is observed as it changes position from season to season. The changes closely relate to knowledge of both cultural matters and the resources linked to the Emu.”77

As documented by the National Museum of Australia Defining Moments Timeline,78 1794, marked the first acknowledged massacre of Aboriginal people by colonisers, known as the Hawkesbury Massacre, in a quest to obtain rich fertile soils for grazing and occupation. With increasing convict populations and harsh drought induced climate, Governor Lachlan Macquarie was focused on increasing the settlement’s capacity to produce its own food. His focus was on grain based agriculture to create a food supply for people and stock. Spurred on by capitalist ideologies, landholders continued to build stock holdings. Colonisers continued to expand their search for pastoral areas in a march to increase personal wealth and landholdings. In 1813 William Charles Wentworth, William Lawson and Gregory Blaxland, crossed to Blue Mountains to seek land for these purposes. Bathurst,west of the Blue Mountains, was established as a colonised town in 1815. For the Wiradjuri people the impacts were unfathomable, with unrelenting violence, displacement and insurmountable deaths.79

41

D O M E S T I C

The Mowgee clan are the Aboriginal people who lived on Country, now known as Mudgee and its surrounding areas. The Mowgee women’s totem is the Wedge Tail Eagle (Maliyan) and the men’s totem is the Crow (Waggan). Wiradjuri Country, 80 by Larry Brandy explains that the Wedge Tail Eagle is Australia’s largest bird of prey and is most visible in the night sky of winter. Whilst, the Crow is best seen in the evening sky during the summer months.

In 1822, William Lawson traveled from Bathurst to Mudgee and declared that Mudgee was the ideal pastoral grounds for agriculture. George and Henry Cox, moved cattle from Bathurst to Mudgee and they established themselves on the property known as Menah; an Aboriginal name meaning ‘place.’ After a short period of time, the relationship between the Mowgee people of the Wiradjuri Nation and the settlers became strained and as stated in Stephen Gapps work, Gudyarra: The First Wiradjuri War of Resistance- The Bathurst War,81 “...when there was ‘interference’ with the women, the warriors’ hostility was aroused. Warriors drove the armed stock men away, released cattle from the yards and killed numbers of sheep.”82 The Cox family responded with a counterattack which took place at Menah. In 1824, an assault on a young Aboriginal woman of the Dabee clan resulted in the men of the tribe burning down a hut and killing the stock men responsible, as well as live stock. The Dabee people were taken by surprise in an attack in the Brymair Valley. Recounts from Gapps book tell of the details pertaining to the massacre which, has had impact on the representation of Aboriginal people in the Mudgee region today; “very many sad scenes, when a war of nearly extermination was declared…An immense number of the natives, men, women and children, were slaughtered at Mudgee.. In the long reach of water at Dabee.”83 Details of the devastation and violence were never recorded and to this day are very rarely spoken of in Mudgee. In a conversation with Aleisha Lonsdale, Mudgee Local Aboriginal Land Council chairperson, she stated that “the people of Mudgee are not ready and may never be ready to learn of these atrocities. What is far more beneficial, is moving forward to create harmonious relationships in the present.”84

The town of Mudgee was gazetted and in 1841 and the township was established and marked by early architecture. The growth of Mudgee and the surrounding areas was the direct result of gold discovery at Hill End. Mudgee became a central hub for trade and travel routes to and from Sydney. The population increased from 200 to over 1500 people in 1861. During this time, the town infrastructure also developed to include churches, a school, post office, police station, court house and town hall.

Increasing colonisation and the introduction of diverse agriculture propelled the economic development of the township during the late 1800’s. Specifically the introduction of wool, merino studs and viticulture. Discovery of coal outside Mudgee, in the small township of Ulan, in 1924 has been an economic driver for nearly 100 years. Coal exploration has expanded across three sites and encroached on the ecology and sacred sites of Country. Ecological destruction through introduced species, farming, mining, viticulture and the use of air borne chemicals has led to decreased populations of native animals, destruction of watering holes and landscapes, impacted the health and well being of the community and represents an overall devaluation of Aboriginal culture. During COVID-19, the region drew many tree changers to the area, in search of a less urbanised environment. Tourism has continued to thrive in the region, with Mudgee being voted the top town for tourism nationally in 2021 and 2022.

43

According to the Mudgee Local Aboriginal Land Council, The Munna Reserve has always been a place of recreation and knowledge sharing, for both Aboriginal and non Aboriginal people. Sharing knowledge is central to Aboriginal culture. The site has been impacted by infrastructure development, the Mid-western Regional Council waste facility and more recently, housing sub divisions. The site however, continues to be significant to the local community through engagement with younger generations. Oral histories and walking together with Country, is critical in ensuring knowledge is shared, for the greater good of the ecology. Currently, the site is utilised as a gathering place for the Aboriginal community and an educational experience for local school children. Community are invested in ensuring education about bush medicine, landcare and regeneration is realised to protect and sustain Country for the future. The following Dreaming story for this site ironically connects to the proposed site program of refuge and healing for women; a call to address the global and local public health crises of trauma and domestic violence against women and children.

(This transcription has been provided by Aleisha Lonsdale, niece of Uncle David Maynard and Chairperson of Mudgee Local Aboriginal Land Council 2022). This story was found in the AIATSIS archives and had been recorded in an old diary of a non Indigenous landowner85 as ‘a legend of the Mudgee Aborigines.’86 The story was transcribed by Wiradjuri man, Uncle David Maynard.

“A long time ago, a young woman was stolen by a man of another tribe and carried away to her far off wurley.

She was not content in her new home and seized the first opportunity to escape. As she was trying to make her way across the mountains to her own tribe a peculiar adventure befell her. She wandered on and on through the bush, not certain as to the direction her steps were leading her, but always climbing higher until at last she reached the moon.

She was fortunate in coming to a part of it that was thickly inhabited not by man, of whom she was afraid, but by kangaroo rats, possums, bandicoots and other small creatures of which she was particularly fond. It did not take long to secure these and having put them in her gunny bag she resumed her march. One morning as she was trudging along she came upon the camp of the man in the moon. As soon as he saw her, he wanted her for his own and he rose and gave chase.

She was too fast for a heavy man who spent most of his time sitting down, so he called his dogs and sent them after her. She thought that her end had come and in fright let fall the gunny bag when out jumped all the imprisoned creatures which scattered in all directions and no sooner than the dogs saw them they forgot the woman and chased after them. These creatures became the stars of the milky way.

By good fortune the terrified woman ran downwards in a straight line for her home, which she reached footsore and weary, but full of her wonderful story which she soon told the tribe.

Henceforth speculation concerning the man in the moon ceased and everyone believed that he was a black man and that the dark spots at his back are his dogs.”

45 M

I C R O

FRAGMENT 3

S I T E A N A L Y S I S

Munna Reserve, Mudgee

47

WIRADJURI NATION

M U D G E E

Mudgee, sits on Wiradjuri Country, in the Cudgegong River Valley, in the Central Tablelands of New South Wales. From conversation with MLALC, the name ‘Mudgee’ derives from the Wiradjuri language. Mudgee (Moothi), translates to resting place or nest in the hills, alluding to rising mountains and their volcanic history capped in basalt lava flows; some 17 million years old.87 Geographic and geological references are also given to the surrounding towns, as part of the strong culture of place-making for Aboriginal people; Lue (a chain of waterholes), Gulgong (a gully) Wollar (a rock waterhole), Menah (flat country) and Cooyal (dry country). The custodians of the land are the Mowgee and Dabee people of the Wiradjuri Nation, whose sacred cultural and tool making sites, such as Hands on Rock, The Drip and Babyfoot Cave remain as significant sites today.

The Cudgegong River, integral to the town, is a perennial stream and forms part of the Macquarie catchment of the Murray-Darling basin. The river rises from the western slopes of the Great Dividing Range within Wollemi National Park to the east, flowing generally in a westerly direction. The Cudgegong River is foundational to a series of fourteen tributaries, before reaching its confluence with the Macquarie River at Lake Burrendong. The natural variability of the river system overall (and during flooding and drought) drives diverse and productive ecosystems. Over time, plants and animals adapted to flourish through different parts of the wetting and drying cycle, however, subsequent damming of the river, in the upper sector at Windamere Dam, has resulted in significant flow changes along the river into the tributaries, impacting these river channels and vegetation. Surrounding the basalt peaks are sandstone ravines and cliff ridges, alongside dry forests and rain forest gorges and broad valleys which spill out into alluvial flats, rich with sediment. This Country has formed the majority of agricultural land in the region.88

49

F L O R A + F A U N A

“There is no place without a history, there is no place that has not imaginatively been grasped through song, dance and design, no place where the traditional owners can not see the imprint of sacred creation.”89 Deborah Rose

An Environmental Report supplied by MLALC- R. Mjadwesch, Flora and Fauna Assessment.90

The site, Munna Reserve, is located 3 kilometres north west of the township of Mudgee and was reclaimed by the Mudgee Local Aboriginal Land Council, through Native Land Title in 2019.91 The site is significant to the Wiradjuri people today, as a space of spiritual nourishment, bush tucker, gathering and knowledge sharing. Historically it is recognised as a recreational space for both the local Aboriginal People and the colonisers. The site is 29 acres and is densely vegetated with both native and introduced flora. It shares a boundary with the local tip and all boundaries are marked by fencing, which have cutaways to accommodate animal migration across and beyond the site.

FRAGMENT 4

A S S E M B L A G E S A C R O S S T H E S I T E

- White Box Grassy Woodland: This area of the site is dominated by White Box (Eucalyptus albens), with a second canopy of Blakely’s Red Gum (Eucalyptus blakelyi) and Yellow Box (Eucalyptus melliodora) to the west of the site. Additionally, a large part of the study area is Box-Gum grassy woodland, a community of species which is listed as endangered under the NSW Threatened Species Conservation Act 1995 and the Commonwealth Environment Protection & Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999. Sub canopies provide a sparse representation across this area of the site, whilst groundcover is dominated by grasses, native and introduced. Assorted herbs are also found amongst the groundcover, alongside Chocolate lilies and orchids. Other sections of the woodland are dominated by Apple Box (Angophora floribunda). There is evidence of robust regeneration around existing older and mature trees. A subcanopy is Cherry Ballart (Exocarpos cupressiformis) and Black Cypress (Callitris endlicheri) supports a grassy understory.

- Wetlands: A diverse group of sedges92 and rushes can be located in the wetland area and around the small dam to the western side of the site. These reeds are traditionally used by women in basket weaving crafts and include native and noxious plant species.

- Fauna: Fauna identified on the site include: Common Eastern Froglet, Shingleback lizard, Echidna, Ring-tailed Possum, Brush-tailed Possum, Eastern Grey Kangaroo, Red-necked Wallaby, European Rabbit, Deer and Red Fox. An abundance of avian species seek refuge across the site, including but not limited to: Sulphur-crested Cockatoo, Little Lorikeet, Eastern Rosella, White-throated Treecreeper, Willie Wagtail, Brown Thornbill, Noisy Friarbird, Golden Whistler, Pied Butcherbird and Currawong.

The following site analysis focuses on the geology, biodiversity, land zoning and services. Whilst this analysis is a traditional way to understand the site, engaging on site with both environmental scientists and Aboriginal community gave greater insight to the site limitations: close proximity to the tip, no existing infrastructure, no access to town water supply, introduced non native species impacting Country and opportunities: gathering and kinship to learn about Country on site, proximity to town, connecting with local schools to teach Aboriginal culture to the broader community, native species located on site, flora to extend weaving and bush tucker education.

51

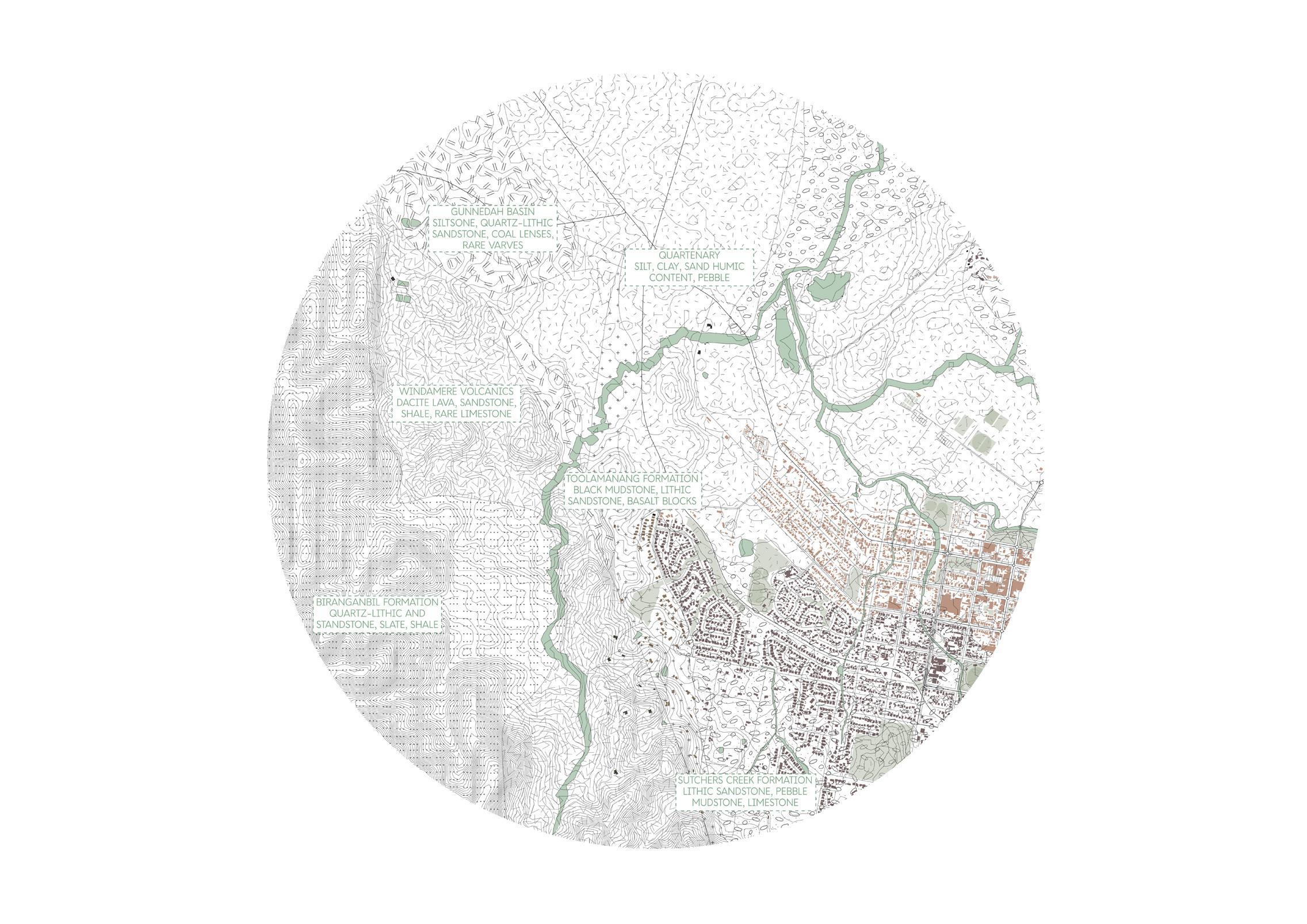

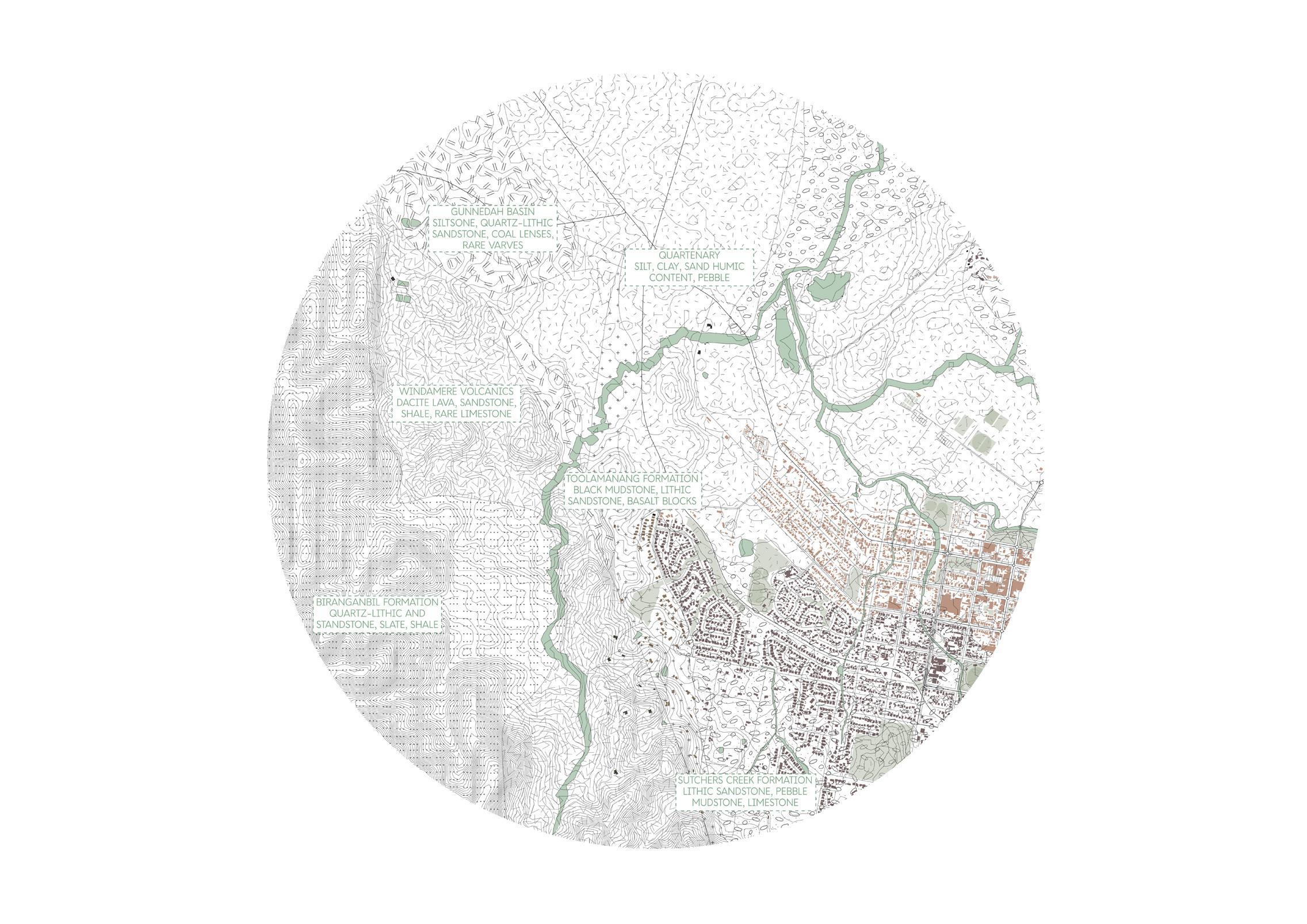

RIVER + CREEK WAYS STVD: WINDAMERE VOLCANICS DQS: SUTCHERS CREEK FORMATION STT: TOOLAMANANG FORMATION QA: QUARTENARY SSB: BIRANGANBIL FORMATIONS PE: GUNNEDAH BASIN CZA: CAINOZOIC PUBLIC GREEN SPACE NEW SOUTH WALES MID WESTERN MUDGEE WIRADJURI

The geology mapping and site analysis focuses on the physical build up of Country’s grounding foundations.

Mudgee and surrounding areas, are rich in many natural resources such as coal, gold, lead and silver, which has seen exploitation and great destruction of Country and many sacred First Nations sites.

Natural sediments such as windamere volcanics (volcanic sandstone, autoclastics, shale, rare limestone), biranganbil formations (quartz-lithic, feldspar-lithic, quartz sandstone, siltstone, slate and shale), quaternary (silt, clay, sand, sporadic pebble) sutchers creek formation (sandstone, mudstone, limestone), gunnedah basin (siltstone, sandstone, conglomerate, coal lenses) and cainozoic (quartz, gravel, sand, silt, clay) build up the geology of the Mudgee area and highlight the significant geographical history of the site.

The diverse geographical makeup of the site and greater area highlights the fragmented, historic layers that are embodied as part of Country; an ongoing, fragmented representation of what was and will be the Country we exist with and within.

53 G

E O L O G Y

VISUALLY SENSITIVE LAND GROUNDWATER VUNERABLE LAND HIGH BIODIVERSITY SENSITIVITY FLOOD PLANNING LAND MODERATE BIODIVERSITY SENSITIVTY ACTIVE STREET FRONTAGE NEW SOUTH WALES MID WESTERN MUDGEE WIRADJURI

B I O D I V E R S I T Y

The biodiversity mapping and site analysis focuses on the western division of Country by government, local councils and other boards, defining what is and isn’t considered of high value, catering to developers, planners and investors, aided by the federal governments Biodiversity Offset Scheme93

Much of the classified high biodiversity and visually sensitive land is defined as the hills, escarpments and dense bush to the south west of the town- the least developed land within the area. However, with increased tourism and mining booms, large parts of the land is slowly being acquired and zoned for industrial and residential purposes.

Aleisha Lonsdale (MLALC) in collaboration with corresponding authour Jessica Mclean, Shadow waters: making Australian water cultures visible, 94 unpack the Indigenous concept of shadow waters. Through this text and conversation, Aleisha explained that shadow waters are the waters that we can not see, yet still hold equally great significance and value to First Nations culture and Country as water which is visible on land. These shadow waters nourish and provide for Country as they adapt to environmental changes. Hence, the classification of such shadow waters as ‘moderate sensitivity,’ is anchored in a western view in only valuing water which can be seen and profited from.

55

E3 R5 R1 R2 RU4 RU1 C3 RE1 R3 B4 SP3 SP2 B3 E1 N S E W MUDGEE CAERLEON PUTTA BUCCA LAWSON CREEK RIVER + CREEK WAYS RE1: PUBLIC RECREATION C3: ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT R1: GENERAL RESIDENTIAL R2: LOW DENSITY RESIDENTIAL R5: LARGE LOT RESIDENTIAL RU4: PRIMARY PRODUCTION SMALL LOT RU1: PRIMARY PRODUCTION PUBLIC GREEN SPACE IN2: LIGHT INDUSTRIAL B3: COMMERCIAL CORE SP3: TOURIST SITE: MUNNA RESERVE NEW SOUTH WALES MID WESTERN MUDGEE WIRADJURI

W A T E R W A Y S + Z O N I N G

Political charged and seen as an economic driver in western philosophy, water and land within the region has been conquered and divided by colonisers and council bodies for over 200 years. Such divisions and zonings have severed and damaged First Nations deep connections and physical relationships to Country and sacred sites across the region.

All though the Australian government claims to working toward a new way of governing land and water through the “Empowering Communities Design Report,”95 initiative, specifically in regional areas, Traditional Owners and Local Aboriginal Land Councils often have faced many difficulties in owning, controlling and managing their own Country. Colonised communities in Australia are often grounded and imposed upon significant water systems for First Nations communities.

“Indigenous rights in water are not adequately recognised by Australian law and policy. This is largely because Indigenous and non-Indigenous perspectives of water and its management differ greatly. This creates difficulties as non-Indigenous laws and management plans separate land from water and generally regard water as a resource available for economic gain. As water is predominantly considered only for its consumptive value, its use and regulation is limited and restricted by governments to industries or individuals willing to pay the highest price.”96

57

FIRST NATIONS SERVICES COMMUNITY HEALTH SERVICES NEW SOUTH WALES MID WESTERN MUDGEE WIRADJURI

S E R V I C E S

Community and health services within Mudgee are limited and under staffed, often resulting in the inability to support local community. The nature of these service models means that they are unsustainable and insufficient for the community in which they are located. Mudgee is part of one of two regions with the highest rates of domestic violence in New South Wales.97 “First Nations Women, women with disabilities, pregnant women and rural/regional women, more likely to be victims to domestic violence .”98

General services in the area such as St Vincent de Paul, Barnardos and Mudgee Community Health are localised to the town CBD and are within walking distance of one another, close other facilities and waterways, making them quite accessible for those without motorised transport.

First Nations targeted services are located on the outskirts of the town’s CBD in the industrial area; isolated and difficult to access.

The Central West has a large Indigenous population, yet access to Indigenous services is inadequate when compared to the quantity of other services in the area and physically inaccessible for most. The locality and lack of services speaks volumes to the little respect and recognition of the history and truth of the region and greater Australia.

59

FRAGMENT 5

M A T E R I A L I T Y & C O N S T R U C T I O N

Materiality for architectural design, on this site, Munna Reserve, has geographical, political, historical, and cultural considerations. Materiality represents art, science and service in both Aboriginal culture and architectural design and is a response to and with the relationship between the environment, design and users. Through conversations with Aleisha (MLALC) on site, consideration of the resourcing and materiality was key when analysing the short and long term impacts to ecologies, macro and micro. Knowing the extremes in local climate, alongside learning about organisation of landscape and the abundance of natural resources currently available on site (or potentially on site), further research was undertaken to analyse and develop understanding of natural materials. This perspective focused on embodied energy, thermal capacity, sustainable use, connection to Country and participant experience.

For Aboriginal peoples, relationship with materiality is relationship with Country. Aboriginal culture and spirituality embraces all matter as living. Materials found on, with and in Country, are extensions of the body and were gifted from ancestors to be used, adapted, recycled and shared. These “..objects were traded along the Songlines hand to hand, Country to Country...”100 As materiality is one with all matter, it forms identity and must not be removed without permission.

Learning in this codesign space focused on mutual knowledge building between the community and I. Bridging technologies past with those in the present and future were conversational frames. Part of the process I valued throughout these discussions was the passive ‘interrogations’ to build knowledge and to question a western way of thinking around new innovations. That is, to look for evidence and action beyond the page of material that ‘tells’ of successes or benefits.

E X P L O R I N G M A T E R I A L I T Y

Honouring relationship with Country is central. Understanding the macro (urban), meso (building) and micro (materials) scales of this project, is essential in designing, constructing and delivering a building which considers impact for a sustainable future and aims for a circular economy. This process aims to challenge the processes and products which contribute to climate change, waste management, biodiversity loss and pollution.

61

“Now that we are coming to terms with the finality of earth’s resources, perhaps we should be reassessing what is ‘primitive’ and what is ‘advanced.”99 Alison Page

Regenerative Tectonic Architecture

2014 saw the initial innovative and design thinking behind mushroom bricks as sustainable, regenerative architectural material for buildings and spaces. Architect David Benjamin, NY, from the firm The Living, was inspired by a manufacturing company, Ecovative, founded in developing practical and economic uses for the mushroom spore mycelium.101 Working closely with Arup, the bricks were developed and resulted in a structurally sound material to produce the Hy-Fy; an architectural installation that won MoMA PS1 Young Architects Program. (Figure 1)

Figure 1.

Mycelium is the fibrous tissue (hyphae) of fungi and is the medium through which reciprocal relationships are formed with plant matter. Mycelium engages with other plants, underground and in exchange for sugars, shares other essential nutrients, via their root systems.102 By nature mycelium are social organisms, according to Doctor Suzanne Simarad, whose life work is focused on the symbiotic relationship between plants and fungi. Simarad outlines in Exploring How and Why Trees Talk to Each Other, plant kinship, both in DNA and care given through mycelium, in order to heal and flourish. A correlation between the plant and human ecologies draws significance to creating experiences to nourish, amidst our current ecological threats. 103

Mycelium presents natural solutions that could replace conventional building materials such as brick, concrete, plastics, particle board and insulation, while being more efficient, more ecologically responsible and cost competitive.104 When harvested and mixed with a substrate the composite may be formed into bricks or panels, dried, and used as strong building material, as discussed in Emerging Materials: Mycelium Brick, by Ilvy Bonnefinn.105 The mycelium brick can be cultivated over a four week period, creating an efficient product in both the context of time and accessibility.

Janet McGaw, Alex Andrionopoulos and Alessandro Liuti, in their research paper, Tangled Tales of Mycelium and Architecture: Learning From Failure, identify properties and additional uses of mycelium as a building alternative in bricks, panels, insulation and flooring.106 The report highlighted that in addition to being water, mould, fire and termite resistant, and a lighter mass than concrete, mycelium is also the most natural and ancient form of polymer. It shares properties similar to synthetic polymers without the toxicity and environmental impact.107 Therefore, Its binding capacity is an ideal eco-solution for adhesives. This material also exhibits an exceptional thermal mass and acoustic properties.

M Y C E L I U M B R I C K S

As a completely organic substance mycelium building products harness a circular economy reducing embodied energy. This is particularly observable in the process from inception to end of life. Mushrooms /fungi may be grown on site, combined with crop waste (to act as a substrate) from the Mudgee community-grape mark, coffee grounds and other agricultural waste, such as lucerne, then moulded and dried on site through both passive and traditional drying methods, cast at approximately 90 degrees. This process reduces fossil fuel use and at end of life the product is 100% biodegradable and may be returned to the landscape, without any impact.

Whilst this innovation on materiality has been gaining momentum, there is opportunity for further experimentation in both material compositions and form, particularly as an authentic consideration for this project. To explore the process of cultivation, texture and properties, I undertook an experiment to grow mycelium to the end product of a brick. Information about the process of cultivation was provided by Russell Whittam, from Aussie Mushrooms.

A C T I O N R E S E A R C H

Cultivating a mycelium brick A visual map

To explore the process of cultivation, I undertook an experiment to grow mycelium to the end product of a brick.

Mycelium spores (Ganoderma Stayaertanum/Australian Reishi) + substrate (grape marc) + substrate (lucerne) + humidity + time = brick

1. Prepare mould and workspace by swabbing in alcohol and wear a mask to prevent contamination

2. Inoculate the substrate with mycelium. Mix thoroughly.

3. Pack the mycelium/substrate into a mould. Tighter packing will produce a smoother end product.

4. Place the mould into a plastic bag and seal. Mycelium requires oxygen to grow. Seal the bag and store between 20-24 degrees celsius , in a dark space.

5. Let it grow- approximately four weeks

6. Bake at 90 degrees celsius for 4 hours to stop the growth and cure the brick.

63

Mycelium spores Substrate: Grape marc

Substrate: Lucerne Mycelium Brick

Figure 2.

Cultivating Mycelium at 2 weeks

Cultivating Mycelium at 3 weeks

Cultivating Mycelium at 4 weeks

Addressing Site Limitations & Opportunities with Mudgee Waste and Recycling Facility

One of the constraints of Munna Reserve, identified in the previous site analysis, is that it shares a boundary with the waste and recycling facility (the tip, as referred to by locals). This has proven, through my research, to be another opportunistic catalyst for regenerative design and an extension into healing Country.