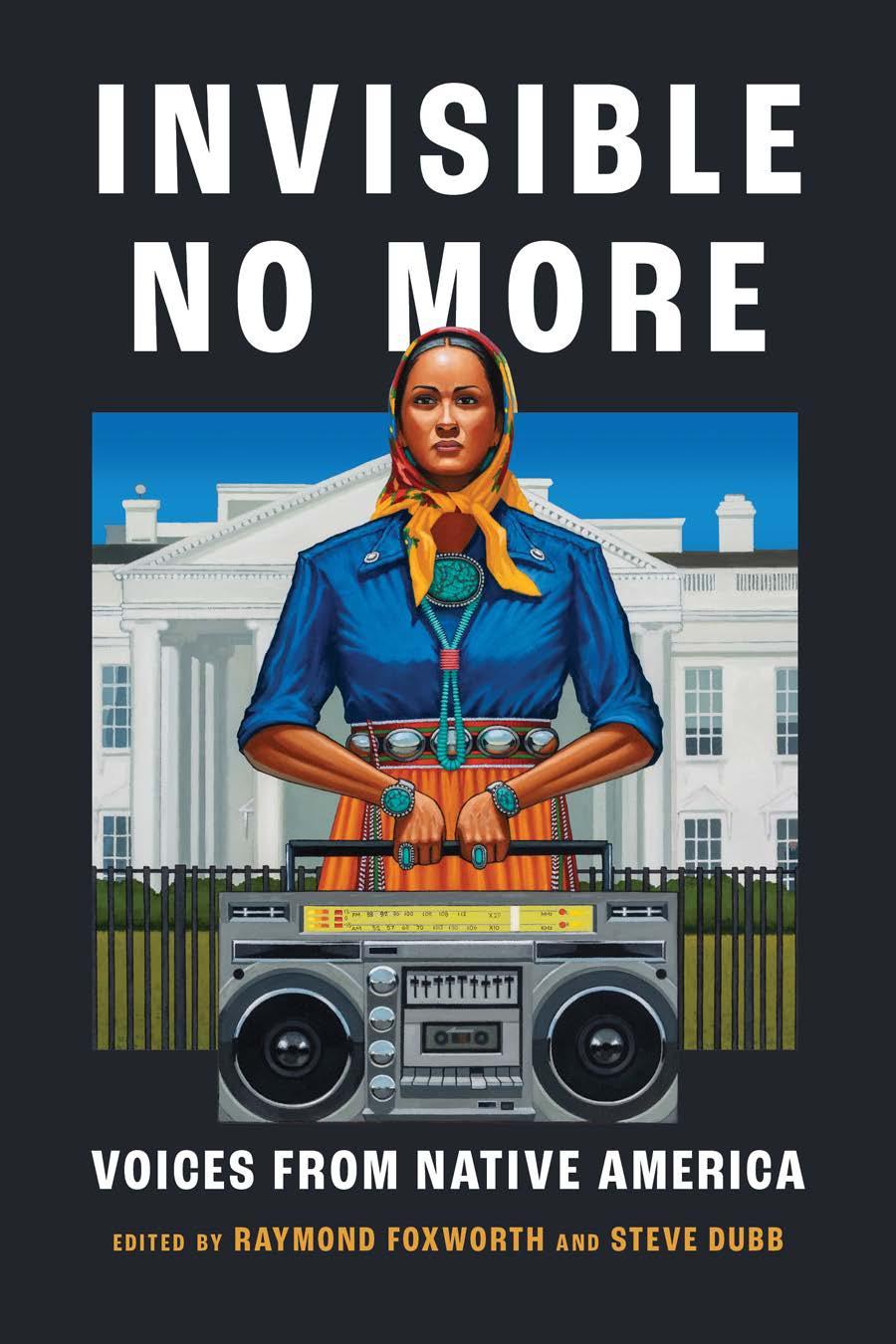

Invisible No More

VOICES FROM NATIVE AMERICA

Edited by Raymond Foxworth and Steve Dubb

© 2023 First Nations Development Institute and The Nonprofit Quarterly

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the publisher: Island Press, 2000 M Street, NW, Suite 480-B, Washington, DC 20036-3319.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2023935909

All Island Press books are printed on environmentally responsible materials.

Manufactured in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Generous support for the publication of this book was provided by the Surdna Foundation.

Keywords: Native American, Indigenous, philanthropy, nonprofit, communitydriven finance, economic justice, environmental justice, leadership, climate change, food justice, food sovereignty, sovereignty, Native American nonprofit sector, Native Hawaiian, Alutiq, Cheyenne, Cheyenne River Sioux, Choctaw, Coast Salish, Hopi, Kiowa, Lakota, Muckleshoot, Navajo, Ojibwe, Oneida, Pawnee, Pueblo, Tlingit, Food systems, Native American history, Native American studies, organizational theory, public administration, nonprofit management

Foreword: “We Are Not Invisible!” by Michael Roberts xi Acknowledgments xvii Introduction 1 Steve Dubb Part I Indigenous Perspectives on Philanthropy 15 Chapter 1 Philanthropy and Native Communities: Toward a More Just Future 19 Raymond Foxworth Chapter 2 Building on Our Strengths: Centering Native People and Native Languages 27 Brooke Mosay Ammann, Valerie Segrest, and Lisa Wilson Chapter 3 Challenging Harmful Philanthropic Practices 44 Sarah EchoHawk and Trisha Moquino Contents

viii contents Chapter 4 Envisioning a Healthy Relationship between Money and Power 56 Sarah Kastelic and Sherry Salway Black Part II Protecting the Environment 71 Chapter 5 Fire, Forests, and Our Lands: An Indigenous Ecological Perspective 75 Hillary Renick Chapter 6 Our Bodies Are the Front Lines: Responding to Land-Based Gender Violence 88 Annita Lucchesi Chapter 7 Fisheries and Stewardship: Lessons from Native Hawaiian Aquaculture 95 Brenda Asuncion, Miwa Tamanaha, Kevin K. J. Chang, and Kim Moa Chapter 8 Fire and the Coast Salish Three Sisters 111 Samuel Barr Chapter 9 The Pendulum of Climate: A Hopi Story 122 Monica Nuvamsa Chapter 10 Heathy Land, Healthy Food, Healthy People: A Cochiti Invitation to Join Us at the Table 130 A-dae Romero Briones Part III Indigenous Perspectives on Environmental Justice 137 Chapter 11 Preserving Our Place: Isle de Jean Charles 141 Chantel Comardelle Chapter 12 Reconciling the Past May Be the Only Way to a Sustainable Future 151 Trisha Kehaulani Watson-Sproat

contents ix Chapter 13 An Indigenous Vision for Our Collective Future: Becoming Earth’s Stewards Again 176 Native Peoples Action Chapter 14 Regeneration—from the Beginning 197 A-dae Romero Briones Part IV Building Native Economies, Toward an Indigenous Economics 207 Chapter 15 Advancing Economic Sovereignty: Lifting Up Native Voices for Justice 211 Raymond Foxworth Chapter 16 Moving beyond the Five C s of Lending: A New Model of Credit for Indian Country 221 Jaime Gloshay and Vanessa Roanhorse Chapter 17 Rewriting the Rules: Putting Trust Lands to Work for Native American Benefit 230 Lakota Vogel Chapter 18 Helping Native Business Owners Thrive: How to Build a Supportive Ecosystem 237 Heather Fleming Chapter 19 Building Community through Finance: A Wisconsin Native CDFI’s Story 249 Fern Orie Chapter 20 Radical Economics: Centering Indigenous Knowledge, Restoring the Circle 257 Vanessa Roanhorse Afterword Building a House of Knowledge 267 Carly Bad Heart Bull

About the Contributors 273 About the Editors 281 Sources 283 Index 287 x contents

We Are Not Invisible!

I grew up in Ketchikan, Alaska. My neighborhood—Deermount, Park and Woodland—was not designated as an official Native village. This area south of Ketchikan Creek in the highly segregated town of Ketchikan differed in many ways from the traditional Native village of Saxman, which was just south of town. But, for all intents and purposes, my neighborhood was a Native village in that it was made up almost entirely of Tlingit, Haida, and Tsimshian households from other Native villages across Alaska, including Hydaburg, Metlakatla, Craig, Kake, and Klawock, where my family was from.

Despite my cobbled-together Native village of aspiring middle-class Native households, much of the life in my neighborhood resembled that of other Native villages—smokehouses were found in most backyards, families argued and held grudges about past slights and injustices, fishing nets wintered in front yards, and the food traditions of hunting, fishing, and foraging carried on and supplemented the incomes and sustenance of almost every household.

xi

FOREWORD

Aside from joining my brother at the beach or along the creek fishing, my favorite food activity growing up was berry picking. For me, it was the sweet reward of blueberries, huckleberries, and Southeast Alaska’s favorite—salmonberries. But I was not the most accomplished berry picker. I mainly stayed on well-traveled streets and sidewalks and picked-over paths and backyard patches, and my yield at the end of hours would often only be a few handfuls of fruit.

And then one day, for some reason, I was up in the early morning, and I watched as a steady stream of Native grandmas and aunties walked past my house with their berry-picking cans. These cans were threepound coffee containers with tethers made of discarded nylon stockings, so they could be hung around their necks and free up both hands for picking. When these grandmas and aunties passed back by my house a few hours later, each and every one of them had two or three cans filled to the brim with salmonberries—enough for pies, multiple jars of jelly, and more. They had my attention.

The next weekend, with a newly constructed berry-picking can around my neck, I followed these experienced ladies to a large thicket of salmonberry bushes along the creek. Among the brambles were yearsold paths created by these grandmas and aunties, marking the way for others to follow.

I share this story because, as Native people, we all look to our grandmas and aunties—our ancestors and even our contemporaries—to point the way forward. We have a keen eye for knowledge and tradition and learning what can only come from experience. In a nutshell, or in this case a berry bucket, that is what this book is all about. It’s about capturing deep knowledge held by Native peoples.

Equally important, this book is about giving voice. Well, not actually “giving” voice, because voice is not mine to give. Nor does voice belong to the editors of this book or to First Nations Development Institute (First Nations). People, including Native people, own their own

xii foreword

voices. But sometimes those voices need amplification. And this book, Invisible No More: Voices from Native America, is an attempt to do just that—make the invisible visible—amplifying the voices and knowledge of Native peoples and Native practitioners.

I have spent a thirty-year career at First Nations championing the idea that Native people matter and Native knowledge matters—as much as and not less than others. And for more than four decades now, First Nations has focused on asset-based development for, with, and by Indian Country. We believe that this is incredibly important—because the appropriated use of American Indian assets in the United Stated has created one of the world’s wealthiest economies. This, of course, has had a negative impact on American Indian economies and communities. And it has exempted Native Americans from the rights to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness that are enjoyed by non-Native Americans.

I am constantly amazed that, two decades into a new century, we are still subjecting Native people to deliberate mistruths and falsehoods, rendering them invisible in American society. How is it that now, when information is more readily available than at any other time in history, we continue to be content in our ignorance of Native people and communities?

Ambivalence occurs when individuals hold contradictory feelings or opinions about someone (or some groups of people). Willful ignorance is simply the idea that, in the face of correct information, individuals tune out or dismiss truths, and instead rely on preexisting knowledge to nullify facts. People in Native America know that, at all levels of American society, there is both ambivalence and willful ignorance when it comes to learning accurate information about Native people and communities. This book’s authors hope to push back on the ambivalence and willful ignorance held by too many Americans, including many of the people who represent philanthropic institutions.

The authors featured in this book represent some of Indian Country’s

foreword xiii

best thinkers. More importantly, each and every one of them are “boots on the ground” practitioners who have dedicated most of their professional lives to the betterment of Native communities. They have borne witness to and have been instrumental in the creation of incredibly creative solutions for not just Native communities, but communities more broadly. And they have accomplished this in an environment in which private philanthropic funders have done their best to ignore, underfund, and—through their inaction—deem Natives as not relevant. Although many of the authors in this collection toil in anonymity and are largely invisible outside of Indian Country, they all have been and continue to be “in it to win it” for Native communities and for making the lives of all Native peoples better. Their knowledge, both new and old, is worth lifting up. Their voices are worth amplifying. The benefit of their sharing reaches beyond the Native communities they serve, and they hold wisdom and offer solutions that benefit the world as a whole.

The authors in this volume challenge those who sit in the boardrooms of philanthropic institutions to dismantle and reimagine the way they do business, and to adopt a way that centers the voices of communities normally excluded from philanthropy. Moreover, the voices in this book offer new perspectives on the economic and environmental crises we are grappling with today. Globally, inequality has grown inexorably, and wealth has been further concentrated in the pockets of the wealthy. Moreover, critical resources needed to sustain human life, like water, are being depleted, as are forests and other natural ecosystems. Native people have been at the forefront of reimagining capitalist models of development, honoring the value of our nonhuman relatives, including land, animals, water, etc. Native people in the United States and across the globe have known that Western development models are not sustainable. The voices in this book speak to these crises and offer critical solutions, and these are the voices that we must elevate and listen to if we are going to create a more equitable, sustainable, and just world for us all.

xiv foreword

The voices in this collection also offer a stark contrast to the predominant narratives about Natives people that romanticize the Indians of the past but ignore Native peoples of the present and future. This collection of essays offers a new narrative—one grounded in Native history and Native values. It is one that gives Native people and Native practitioners visibility, and one that suggests a strong call to action. The crises that individual authors speak to in this book are not crises created by them or the communities they come from. They are crises created by a Western society that has viewed land and the environment as theirs to exploit and wealth as theirs to hoard and use for power and the exploitation of workers and communities. Nonetheless, Native people continue to be optimistic and offer solutions to solve global problems. The question remains: Will Americans listen?

All of this is what we hope to give readers in Invisible No More: Voices from Native America. It is yet another gift from Native America to America itself. I hope you cherish it with the same intent as that with which the gift is given.

Michael Roberts Longmont, Colorado

foreword xv

Acknowledgments

This book is not just a partnership between the two of us as editors, but it is also the product of a multiyear collaboration and partnership between two organizations, First Nations Development Institute (First Nations) and Nonprofit Quarterly (NPQ). The relationship began with an article authored by Ray (and edited by Steve) that was published in NPQ in 2018: “Busting Philanthropy’s Myths about Native Americans.” That theme was expanded the following year into a series of articles, organized by First Nations and published in NPQ. And that led in turn to three additional series of articles on environmental and economic justice work in Indian Country.

At First Nations, when we approached NPQ with the idea of an article series in 2018, we were surprised at the positive reception of the idea. The idea for the series grew out of many conversations with community leaders and allies in philanthropy. The biggest cheerleader was Hester Dillon, then at the NoVo Foundation. Originally, First Nations approached another philanthropic publication with the idea of an article series, and they wanted us to draft a larger memo to effectively convince

xvii

them of how these articles would fit with their so-called diversity, equity, and inclusion goals. First Nations discussed this frustrating response with Hester and she stated emphatically that “if you have to convince them now that this is a good idea, they are not aligned with your goals and values.”

She was right. A few weeks later, First Nations pitched the idea to Ruth McCambridge and Steve Dubb at NPQ. They enthusiastically said, “Yes, this is a great idea!” The original series we pitched was to include as authors both funders and Native community leaders. Ruth at NPQ was the first to say that the beauty of this series is hearing from Native community leaders, not philanthropy. She, too, was right. At First Nations, we cannot adequately express our gratitude to Hester, Ruth, and Steve for their support and belief in this project and seeing the fundamental importance of raising Native voices in this sector.

Moreover, we also wish to thank Cassandra Heliczer, NPQ’s magazine editor extraordinaire. In 2020, Ruth convinced Ray to serve as a guest editor with Cassandra for an issue of the magazine. Chapters 8, 9, 11, 12, 13, and 14 were all originally published in the Nonprofit Quarterly print magazine, and they all reflect Cassandra’s editing hand.

The idea for organizing a collection of essays into a book emerged in early 2022. At the beginning of that year, Cyndi Suarez, who had become editor in chief at NPQ a year earlier, encouraged staff to submit proposals of material that might work as a book. Out of that conversation came the idea that maybe NPQ could work with First Nations to create the volume that became Invisible No More.

This is a first-of-its-kind book project—elevating the voices of Native community leaders doing amazing work in the Native nonprofit sector—so the authors who have contributed to the various series of articles deserve special recognition. When First Nations first reached out to many of the authors, they were surprised—initially reluctant, yet excited to share their voices, perspectives, and work. One of First

xviii acknowledgments

Nations’ early observations was that any reluctance that the authors expressed came from witnessing and experiencing the systemic exclusion of Native voices in the nonprofit and philanthropic sectors. But given our experience in working with the many brilliant thinkers and leaders across Native America, we have always known that Native leaders have a vision for the future of their work and their communities, and a vision to make the world a better place for the future of Indian Country. The leaders who contributed to this volume stepped outside their comfort zones to express their perspectives, frustrations, and ideas for work in the nonprofit and philanthropic sectors. Thank you for sharing your brilliance! This book only highlights a few of the brilliant minds in Indian Country; there are many more brilliant Native people doing critical work in their communities to advance Native life in the face of colonialism. We thank all these leaders for the work they continue to do!

Both NPQ and First Nations want to also acknowledge others who deserve special recognition. At First Nations, we thank the late (and much beloved) Randal “Randy” Blauvelt and Amy Jakober, who helped provide input and edited many early versions of the essays that appear in this book. Mike Roberts, A-dae Romero Briones, Catherine Bryan, and Jackie Francke suggested some of the authors we might include. Also, of course, A-dae has been critical to this project. She has not only been a contributor but has also helped recruit writers for this book, specifically Monica Nuvamsa and Samuel Barr. Similarly, Allison Jones of Common Future played a similar role in recruiting Vanessa Roanhorse’s contribution in chapter 20. We also thank Joel Toner, publisher of NPQ, for his expertise, guidance, and encouragement in advancing this project. And we thank Craig George for allowing us to utilize his beautiful art for the cover of this book.

There were many times when it felt like the book might never get published, but at each step there were champions who helped keep the book on the path toward completion. Internally at NPQ, in addition to

acknowledgments xix

Cyndi and Cassandra, a critical champion was NPQ’s former managing editor, Michelle Rada, who encouraged Steve to pursue the project. At one critical point, Sarah Wentzel-Fisher, who is executive director of the Quivira Coalition in New Mexico and was part of a fellowship cohort with Steve in 2018 and 2019, suggested a few ways for Steve to continue to pursue the project at a point when it was not clear that a publisher would be found.

While the idea for the book goes back to January 2022, it wasn’t until the following summer that we connected with Island Press acquisitions editor Erin Johnson, who was willing to take a chance on this curated collection. Erin believed in the book and helped move heaven and earth to make the book a reality. Thanks, too, of course, to the entire Island Press team that has backed this project.

Also helping along the way were our philanthropic supporters—the Surdna Foundation, the Henry Luce Foundation, the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative, the Claneil Foundation, the Nell Newman Foundation, and the Kresge Foundation—whose support enabled us to pay writers stipends and make the cost of publication affordable.

Last, but not least, we would like to express our thanks to Carly Bad Heart Bull, who wrote the afterword to this collection. As Carly writes near the end of her contribution, the authors “have shared these gifts with us. It is now up to us to go out and do something with them.” May it be so.

xx acknowledgments

Introduction

Steve Dubb

They have assumed the names and gestures of their enemies, but have held on to their own secret soul, and in this there is a resistance and an overcoming, a long outwaiting.

— N. Scott Momaday (Kiowa), House Made of Dawn1

At its heart, this volume lifts up a wide range of vital stories from Native American leaders and organizations. There are many reasons that Raymond Foxworth and I decided to organize this collection. One reason appears right there in the title: Invisible No More. It is long past time to end the invisibility of Native Americans and make Native American voices accessible to a broad popular audience.

This book also is a product of a much broader movement among many people from within the 574 federally recognized Indigenous nations (and the many more that remain unrecognized).2 In fact, the authors in this collection are among the leaders of a rising social, political, and cultural movement that has swept many Native communities. N. Scott Momaday’s writings, cited above, form part of a broader cultural

1

movement. The American Indian Movement (AIM) was founded in 1968, the same year that Momaday’s Pulitzer Prize–winning novel was published.3 A year later, AIM activists began a nineteen-month occupation of Alcatraz Island, garnering national attention.4

The official federal policy regarding Native Americans in the 1950s and 1960s was known as “termination”—and it meant exactly what it sounds like it meant: federal government policy sought to terminate tribal nations and end Native sovereignty entirely. One tactic the federal government used was to offer free one-way tickets for Native Americans to move to “relocation cities” like Portland, Oregon, and Minneapolis, Minnesota. An estimated 100,000 people were moved in this way. This is one reason why two-thirds of Native Americans today live “off the rez” in urban areas.5

Native American organizing such as AIM forced an end to federal termination policy, which was legislatively reversed in 1975 when Congress passed the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act.6 Additional policy gains followed. It is worth reflecting on how recent some of these victories are. It was in 1978 that the Indian Child Welfare Act and the Indian Religious Freedom Act were passed. The former was designed to keep Native American families together and is currently facing a Supreme Court case challenge.7 The latter is a potent reminder that until 1978 Native Americans on reservations lacked the legal right to openly perform sacred ceremonies.8

Subsequent policy wins include the 1988 Indian Gaming Regulatory Act and the 1994 Equity in Educational Land-Grant Status Act. The latter established federal support for what is today a network of thirty-five tribal land-grant colleges with a combined student enrollment of 23,000; a recent study found that each dollar invested in a tribal college returns $5.20 in economic benefits to Native nations.9 As for gaming, a study published in the Journal of Economic Perspectives found that gaming generated $28 billion in revenue by 2013, up from $100 million

2 invisible no more

in 1988, but cautions that “the accumulated economic and social deficits on reservations” far exceed gaming revenues.10 Indeed, as coeditor Raymond Foxworth has noted, not only is the distribution of gaming revenues among Native nations highly uneven, but the per capita gap in income between Native and non-Native Americans far exceeds—by a factor of ten or more—any conceivably sustainable annual profit-distribution scheme.11

In recent years, Native communities have also increasingly mobilized politically. On an international stage, this was evident at the internationally prominent pipeline protests at Standing Rock beginning in 2016.12 Mobilization also occurred at the ballot box, with Native voters playing a decisive role in swing states such as Arizona and Wisconsin in the 2020 presidential election. Native American voter turnout in 2020 reached record highs and six Native Americans were elected to Congress, a record number and three times the Native congressional delegation that existed just two years earlier.13

Again, it is remarkable how recent all of this is. The first two Indigenous women elected to Congress, Deb Haaland (Laguna Pueblo) and Sharice Davids (Ho Chunk), assumed their seats in January 2019. In 2021, Haaland left Congress to become secretary of the interior— the first Native American cabinet official in over two centuries of US history.14

Making the Invisible Visible

What is meant by invisibility? It is certainly no secret that North America—or Turtle Island, a common Indigenous name for the continent, particularly among the Algonquian and Iroquois nations15—was settled by Indigenous peoples many millennia before European settlers arrived. But mainstream (read White) US society has often refused to “see” this.

Often, Native Americans have been treated as vestiges of the past, not living people today.

introduction 3

And even when looking at the past, the historical account is regularly distorted. The violence of genocide, including the seizure of an estimated 1.5 billion acres (over 2.3 million square miles) of land and the forcible relocation of people onto reservations, is downplayed, if not denied altogether.16 The so-called Indian boarding schools, which explicitly sought to separate Native children not just from their parents but their culture (“Kill the Indian, save the man” was the refrain of Colonel Richard Henry Pratt, founder of one of the most famous of these schools in Carlisle, Pennsylvania) are also typically ignored.17

Instead, often what passes for “history” are warmed-over myths, such as Thanksgiving narratives that offer, as Lower Brule Sioux member Jordan Daniel kindly puts it, a “very romanticized, whitewashed education,”18 or Hollywood Westerns that have regularly employed “the dual stereotype of the noble Indian and the bloodthirsty savage.”19

Meanwhile, millions of Native Americans today often remain unacknowledged. As a social studies teacher said to an Education Week reporter in a segment broadcast by PBS NewsHour a few years ago, “When you tell [students] that Native people are still here in America, they’re like, ‘Oh, we didn’t know that.’”20

Challenging Invisibility in Philanthropy

This invisibility has major consequences throughout US society. This volume does not purport to cover all aspects of this, but it does make a valuable contribution in showing how Native nonprofit institutions and Native nonprofit leaders are actively challenging that invisibility in the philanthropic world. Nationally, in the United States, in 2021 total philanthropic giving totaled $484.85 billion; in terms of assets, that year foundation assets exceeded $1.3 trillion.21 There are, in short, considerable resources that could make a significant difference if philanthropy adequately resourced the obvious leadership emerging from Native communities.

4 invisible no more

Unfortunately, far too many in the philanthropic world have failed to step up for Native communities. For example, a 2020 study produced by Native Americans in Philanthropy and Candid, a leading nonprofit sector research firm, noted that while 2.9 percent of Americans are Indigenous, between 2002 and 2016 only 0.4 percent of foundation grant dollars served Native Americans.22 A more recent survey conducted in the spring of 2021 by the Center for Effective Philanthropy (CEP), found that—even though Native communities experienced greater levels of economic stress and the highest rates of infection and death from the COVID-19 pandemic23—only 11 percent of 256 surveyed foundations made significant funding commitments during 2020 and 2021 to Native-serving nonprofits.24 The CEP research team correspondingly titled the report that resulted from their survey Overlooked.

Moreover, if one looks at funding for not just “Native-serving” but also “Native-led” organizations, then the level of philanthropic support is even more limited. For instance, a 2018 report from First Nations Development Institute that examined grantmaking from 2006 to 2014 found that “the majority of grant dollars awarded annually in support of Native American causes are awarded to non-Native-controlled nonprofit organizations. ”25

Even when foundations do make grants, stereotypes often color what is and is not funded. One Native leader cited in the CEP report noted that a foundation program officer had told their group that “they couldn’t fund us because the participants in our program were successful emerging leaders. We interpreted that as, ‘They just want to fund drunk, starving Indians on the reservation or on skid row in the city. They’re not interested in what Native American leaders can contribute to the rest of society.’”26 Such examples are disturbingly common. As one contributor, Trisha Moquino (Pueblo of Cochiti), notes in this volume, “We often feel ashamed and traumatized for thinking that our community goals to heal and thrive on our own terms do not match nicely with the broader goals of philanthropy (or people in philanthropy).”

introduction 5

Hidden in Plain Sight

As the late baseball great Yogi Berra famously said, “You can observe a lot by watching.”27 Many in philanthropy and elsewhere may not be watching, but if they were to do so, they would observe a wide range of Native American solutions that carry considerable relevance not just for addressing local needs, but also global challenges. This speaks to one more critical motive behind the creation of this volume, which is to illustrate how Native individuals and organizations are leading dynamic movements for social, economic, and environmental justice.

Simply put, in a world facing mounting crises around economic inequality, the global climate emergency, and environmental degradation, many of the most innovative solutions to these challenges are being developed in Indigenous communities. Often these solutions derive from Indigenous value systems, cultural traditions, and an ethic of stewardship.

But these solutions—and the creativity that lies behind them—are also, in large part, the product of marginalization. While innovation is often depicted as emanating from high-tech firms, when it comes to far-reaching social change, more often than not innovation comes from people who have a lesser stake in the status quo and who are therefore less constrained by present-day myths. As Tarig Hilal, a British-born social entrepreneur working in Africa, observes, “Constraints drive innovation. Faced with the challenges of exclusion, people invent. The solutions that they create not only represent solutions to their own problems, but often have far wider applications.”28

As will be seen in the essays that follow, the authors in this volume are not academics. They are not just writing about solutions. They are instead writing about solutions that they themselves are implementing in their own communities. Reading this collection provides a window

6 invisible no more

into the rich world of cultural, social, environmental, and economic innovation that is spreading across Native America.

How This Collection Was Assembled

This collection results from a partnership that developed between First Nations Development Institute (First Nations), where Raymond was serving as vice president, and Nonprofit Quarterly (NPQ), where I work as a senior editor. When we first connected, we discussed how NPQ, which hosts social justice conversations, might partner with First Nations to run a series of articles on the relationship between Indian Country and philanthropy.

At first, the idea was to ask philanthropic leaders to write about how their foundations were supporting grantmaking in Indian Country and highlight what others could learn from their experiences. But out of our conversations emerged a different approach; why not provide a forum for Native leaders to speak directly to philanthropy?

Of the authors in this volume, mine is the sole settler voice. And I grew up with the same myths that I write about here; for example, when I was six and seven, I participated in a YMCA-sponsored program known as “Indian Guides” that clumsily appropriated Native American culture (and has fortunately been discontinued).29

My first exposure to working in Indian Country involved my participation in a project known as the Learning/Action Lab for Community Wealth Building. This project, which I worked in between 2013 and 2016, was with the Democracy Collaborative, a former employer of mine. Our team sought to help Native communities to use employee ownership and social enterprise strategies to build and retain community wealth. Funded by the Northwest Area Foundation, we worked with two urban Native groups (in Portland, Oregon, and Minneapolis, Minnesota) and three reservation-based groups. In the process, I saw

introduction 7

the cultural rebuilding that was occurring in real time, as many Native leaders, who were often the first in their generation to go to college, were building new worlds by combining contemporary practices with restored Indigenous cultural traditions.30

In short, my personal experience persuaded me that an approach that offered stories directly from Indian Country would generate stories worth reading and would resonate with NPQ’s readership. As it happens, the first series was so well received that First Nations and NPQ decided to co-produce three more series over the next two years—each tackling a different theme, which here are organized as the sections of this book.

The process was as follows: First, we would agree upon a common theme. Then, First Nations—mostly Raymond, but sometimes his colleague A-dae Romero Briones—identified the authors and topics and would help individual authors (or author teams) develop their stories. Then, after First Nations had completed its review, NPQ (often me— but sometimes my colleague Cassandra Heliczer) would work with the authors to edit and refine the articles for publication.

By early 2022, Raymond and I realized that the richness of the content merited the broader audience that this volume could attract. In putting together this collection, however, we asked authors to update and revise their contributions into the chapters that exist here. We have also, where appropriate, added new voices that complement these contributions. And in section introductions, we have added text to connect the articles with each other and the broader conversation.

Organization of the Work

We have organized the book into four sections. The first section, “Indigenous Perspectives on Philanthropy,” offers a series of seven contributions, organized into four chapters, that speak to the central problem of invisibility; highlight the importance of language recovery to cultural rebuilding; identify how philanthropy has often, whether intentionally

8 invisible no more

or not, undermined Native community building; and offer principles for building more trust-based, reciprocal relationships.

The next section, “Protecting the Environment” focuses on Native American environmental preservation efforts in a variety of locations. In this section, our authors write about Indigenous management techniques for caring for forests by using controlled fires; the struggle against the Dakota Access Pipeline, including analysis of the interconnection between environmental and gender justice; the effort to restore historical Hawaiian fishery management practices; Hopi attempts to maintain desert agriculture amid climate change; and a reconceptualization of the food system rooted in Cochiti Pueblo practices of land stewardship.

The third section, “Indigenous Perspectives on Environmental Justice,” builds on the second section, but with a more explicit focus on climate justice and the often-complicated relationship between the formal (often White-dominated) environmental movement and Indigenous groups. From Hawai‘i to Alaska to an island in Louisiana in which the Choctaw community has seen 98 percent of their island home disappear due to rising sea levels, the writers in this section offer critical insights on the connections among vision, culture, policy, and environmental justice.

In the final section of the book, “Building Native Economies: Toward an Indigenous Economics,” the authors recast and redefine what is meant by “economy.” The root words of economy (eco and nomos) mean “management of home (eco being the Greek root for “home” and nomos the Greek root for “management”).31 The authors here part from this broad notion of “economy” and offer their visions for an Indigenous economy that is rooted in justice that decolonizes Native communities and creates self-sustaining Indigenous economies.

The themes of the chapters in this section range from tackling the issue of financing development on trust lands to supporting Native business ownership to developing Native community finance to restructuring

introduction 9

entire lending models and even the entire economy to place notions of multigenerational thinking and regeneration at the center.

Let the Conversation Begin

In short, this book is animated by the belief that narratives rooted in Indigenous experience have much to contribute to a recalibration of the economy, the environment, and human relationships—both for Indigenous communities and beyond. We hope this collection speaks both to Native and non-Native audiences. It is, of course, impossible to reflect the true diversity of over 500 different Indigenous nations, but we hope that members of Native communities feel that they are “seen” in this volume. And we hope that non-Native readers “observe a lot by watching.”

A few final notes: In this book, we seek to challenge narratives about Native Americans that have been central to dehumanizing them. We hope that after reading this collection that the energy and vital role played by Native leaders and organizations in today’s social change movements, especially in the fields of environmental and economic justice, is obvious. And we hope that the publication of this volume is not a one-off, but instead will spark far greater interest and new platforms for Native communities, so many of whom are offering leading-edge thinking for how to build a sustainable world.

We also hope that this book is widely read not just by students of Native America, but policymakers and philanthropists as well. We know that tensions and hostility over land and natural resources have shaped relationships between the federal government and Native nations across the continent. We hope that the authors in this collection inspire a deepening conversation of what decolonization means and what decolonization requires. The reciprocal practices lifted up by many of the authors really do offer some paths forward—if the wisdom of the authors is heeded.

10 invisible no more

Lastly, this book also highlights Indigenous solutions that are key to solving some of the current global crises around inequality, climate change, and environmental degradation. Beyond the individual offerings of the authors, the call here is to move beyond the walls that separate culture, economy, and environment, as if these were distinct, disconnected spheres. Fundamentally, the call for stewardship, the call for righting the wrongs of colonization and for supporting Indigenous sovereignty, and the call for sustainable environmental practices, are really calls to all readers to recognize that interconnected nature of the world we live in—and to act accordingly.

Notes

1. N. Scott Momaday, House Made of Dawn (New York, NY: Harper Row, 1968).

2. Bureau of Indian Affairs, “Indian Entities Recognized by and Eligible to Receive Services from the United States Bureau of Indian Affairs,” Federal Register, January 29, 2021, https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2021/01 /29/2021-01606/indian-entities-recognized-by-and-eligible-to-receive -services-from-the-united-states-bureau-of.

3. Gale Family Library, “American Indian Movement,” Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul, MN, September 6, 2022, https://libguides.mnhs.org/aim; The Pulitzer Prizes, “The 1969 Pulitzer Prize Winner in Fiction,” Columbia University, New York, NY, n.d., https://www.pulitzer.org/winners/n-scott -momaday.

4. Loretta Graceffo, “The Spirit of the Indigenous Occupation of Alcatraz Lives On, 50 Years Later,” Truthout, November 20, 2019, https://truthout.org/arti cles/the-spirit-of-the-indigenous-occupation-of-alcatraz-lives-on-50-years -later.

5. Max Nestarak, “Uprooted: The 1950s Plan to Erase Indian Country,” APM Reports, Minnesota Public Radio, Minneapolis, MN, November 1, 2019, https:// www.apmreports.org/episode/2019/11/01/uprooted-the-1950s-plan -to-erase-indian-country.

6. National Congress of American Indians, “Seventy Years of NCAI: From Imminent Threat to Self-Determination,” NCAI, Washington, DC, n.d., https:// www.ncai.org/about-ncai/mission-history/seventy-years-of-ncai#1970.

7. Eva Lopez, “‘Keep Our Families Together’: A Law That Protects Native

introduction 11

Families Is at Risk,” American Civil Liberties Union, New York, NY, November 21, 2022, https://www.aclu.org/news/racial-justice/icwa-a-law-that -protects-native-families-is-at-risk.

8. Dennis Zotigh, “Native Perspectives on the 40th Anniversary of the American Indian Religious Freedom Act,” Smithsonian Magazine, November 30, 2018, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/blogs/national-museum-american-indian /2018/11/30/native-perspectives-american-indian-religious-freedom-act.

9. Bradley Shreve, “Joe McDonald on the Passage of the 1994 Land-Grant Act,” Tribal College Journal of American Indian Higher Education 30, no. 3 (spring 2019), https://tribalcollegejournal.org/joe-mcdonald-on-the-passage-of-the -1994-land-grant-act/; Genevieve K. Croft, “1994 Land-Grant Universities: Background and Selected Issues,” In Focus, Congressional Research Service, Washington, DC, January 4, 2022, https://sgp.fas.org/crs/misc/IF12009.pdf; Marcella Bombardieri and Dina M. Horwedel, “For Native Americans, Tribal Colleges Tackle the ‘Present-Day Work of Our Ancestors,’” Center for American Progress, Washington, DC, November 18, 2022.

10. Randall K. Q. Akee, Katherine A. Spilde, and Jonathan B. Taylor, “The Indian Gaming Regulatory Act and Its Effects on American Indian Economic Development,” Journal of Economic Perspectives 29, no. 3 (summer 2015): 185–208, quote on p. 199, https://pubs.aeaweb.org/doi/pdfplus/10.1257/jep.29.3.185.

11. Raymond Foxworth, “Busting Philanthropy’s Myths about Native Americans,” NPQ, August 27, 2018, https://nonprofitquarterly.org/busting-myths -native-americans.

12. Alexis Celeste Bunten, “Indigenous Resistance: The Big Picture behind Pipeline Protests,” Cultural Survival, March 3, 2017, https://www.culturalsurvival org/publications/cultural-survival-quarterly/indigenous-resistance-big -picture-behind-pipeline-protests.

13. Erica Belfi, “Native Americans Elected to U.S. Congress,” Cultural Survival, November 23, 2020, https://www.culturalsurvival.org/news/historic-number -native-americans-elected-us-congress.

14. Sofia Jarrin, “Indian Country Begins to Witness Real Signs of Justice,” NPQ, March 17, 2021, https://nonprofitquarterly.org/indian-country-begins-to-wit ness-real-signs-of-justice/.

15. Amanda Robinson, “Turtle Island,” updated by Michelle Filice. In Historica Canada, The Canadian Encyclopedia, Toronto, November 6, 2018, https:// www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/turtle-island.

16. Claudio Saunt, “The Invasion of America,” Aeon, January 7, 2015, https:// aeon.co/essays/how-were-1-5-billion-acres-of-land-so-rapidly-stolen.

12 invisible no more

17. Steve Dubb, “Recalling the Violence of the ‘Indian School,’ 200 Years after Its Founding,” NPQ, March 7, 2019, https://nonprofitquarterly.org/recalling-the -violence-of-the-indian-school-200-years-after-its-founding.

18. Samantha Chery, “These Native Americans focus on family amid Thanksgiving’s dark history,” Washington Post, November 19, 2022, https://www .washingtonpost.com/lifestyle/2022/11/19/thanksgiving-native-americans.

19. Martin Berny, “The Hollywood Indian Stereotype: The Cinematic Othering and Assimilation of Native Americans at the Turn of the 20th Century,” Angles, October 2020, https://journals.openedition.org/angles/331.

20. Education Week and PBS Newshour, “How Teachers Are Debunking Some of the Myths of Thanksgiving,” PBS NewsHour, November 20, 2018, https:// www.pbs.org/newshour/show/how-teachers-are-debunking-some-of-the -myths-of-thanksgiving.

21. National Philanthropic Trust, The 2022 DAF Report (Jenkintown, PA: NPT, 2022), https://www.nptrust.org/reports/daf-report/.

22. Native Americans in Philanthropy, “Native Americans Are 2.9% of U.S. Population but Receive 0.4% of Philanthropic Dollars,” November 17, 2020, https://nativephilanthropy.org/2020/11/17/native-americans-are-2-of-u-s -population-but-receive-0-4-of-philanthropic-dollars.

23. Raymond Foxworth, “Philanthropy’s Role in Reinforcing Settler Colonialism,” Center for Effective Philanthropy, Cambridge, MA, 2022, https://cep .org/philanthropys-role-in-reinforcing-settler-colonialism.

24. Ellie Buteau, Hannah Martin, and Katarina Malmgren, Overlooked (Part Two): Foundation Support for Native American Leaders and Communities, Center for Effective Philanthropy, Cambridge, MA, 2021, http://cep.org/wp-content /uploads/2021/07/CEP_Overlooked_Native_American.pdf.

25. Raymond Foxworth and Benjamin Marks, Growing Inequity: Large Foundation Giving to Native American Organizations and Causes, 2006–2014 (Longmont, CO: First Nations Development Institute, 2018), 2, https://www.firstnations .o rg/wp-content/uploads/publication-attachments/Growing%20_Inequity _%28WEB%29.pdf.

26. Ellie Buteau, “Funders Remain MIA for Many in Asian and Native American Communities,” NPQ, February 15, 2022, https://nonprofitquarterly.org /funders-remain-mia-for-many-in-asian-and-native-american-communities.

27. Carrie Fox, “You Can Observe a Lot by Watching,” Mission Partners, Rockville, MD, January 26, 2022, https://mission.partners/theintersection/you -can-observe-a-lot-by-watching.

28. Tarig Hilal, “Innovating from the Margins,” Medium, April 24, 2019, https://

introduction 13

medium.com/swlh/innovating-from-the-margins-1390057e6ee. For Hilal’s biographical details, see his LinkedIn page at: https://www.linkedin.com/in /tarighilal.

29. John Keilman, “Indian Guides, Princesses Must Drop Indian Theme or Leave YMCA,” Chicago Tribune, September 19, 2015, https://www.chicagotribune .com/suburbs/la-grange/ct-ymca-indian-princess-met-20150918-story.html.

30. Regarding the project, see: Stephanie Gutierrez, An Indigenous Approach to Community Wealth Building: A Lakota Translation, The Democracy Collaborative, Washington, DC, November 2018, https://base.socioeco.org/docs/com munitywealthbuildingalakotatranslation-final-web.pdf.

31. Adrienne Maree Brown, “Murmurations: Building a Compassionate Economics,” Yes! Magazine, February 17, 2022, https://www.yesmagazine.org/opinion /2022/02/17/murmurations-building-a-compassionate-economics.

14 invisible no more