PARKING MANAGEMENT for Smart Growth

RICHARD W. WILLSON

RICHARD W. WILLSON

RICHARD W. WILLSON

RICHARD W. WILLSON

Copyright © 2015 Richard W. Willson

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the publisher: Island Press, 1718 Connecticut Avenue NW, Suite 300, Washington, DC 20009

Island Press is a trademark of The Center for Resource Economics.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2014955500

Printed on recycled, acid-free paper

Manufactured in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Keywords: Community planning; curb parking; information technology; integrated parking management; maximum parking requirements; minimum parking requirements; mixed-use, transit-oriented development; multimodal transportation; off-street parking management; on-street parking management; parking best practices; parking demand management; parking reform; parking utilization; pricing parking; shared parking; sharing economy; strategic parking management

List of Figures xi

List of Tables xiii

Acknowledgments xv

1. introduction: What is a Parking Space Worth? 1

Parking as a Contested Space 8

Problems of Unmanaged Parking 11

Understanding Parking Behavior 14 Strategic Parking Management and the Future 16 Key Terms 21 Map of the Book 24

Conclusion 26

2. Parking Management Techniques 27

Origins of Parking Management 27

Basic Methods of Parking Management 29 A Framework for Organizing Parking Management Measures 35 Basic, Intermediate, and Advanced Parking Management 42 Parking Management Gone Wrong 45

Conclusion 51

3. creating a Parking Management Strategy 53

Planning and Strategy in Parking Management 55 Parking Management Stakeholders 60

Process for Developing a Parking Management Strategy 64 Process Pays 96

4. Managing an integrated, Financially Sustainable Parking district (by rick Williams) 97

Management Principles 98

Organizational Structure: Administration and Management 103 Defining the Role of On-Street Parking 105

Relationship of On- and Off-Street Parking Assets 108

Rate-Setting Policy and Protocols 109 Measuring Performance 112

5.

Identifying and Communicating the Integrated Parking System 116

New Technologies 125

Financial Analysis and Management 130

Conclusion 133

Best Practice: Individual Tools 139

Best Practice: Comprehensive and Coordinated Approaches 151

Global Perspectives 165

Best Practice Conclusions 168

6. implementing Strategic Parking Management 169

Politics and Community Participation 169

Setting Prices 178

Implementing Shared Parking Agreements 185

Accessible Parking and the Abuse of Disabled Parking Placards 187

Meter Equipment Pitfalls 189

Failure to Implement Coordinated Measures 190

Parking Enforcement 191

Greening Parking Operations 196

Conclusion 199

7.

A Paradigm Shift 202

Why Not Rely on Pricing Alone? 205

Strategic Parking Management and Smart Growth 207 It’s Time 216

References 217 Index 221

Figure 1-1 Wasted spaces at Angel Stadium in Anaheim, California 4

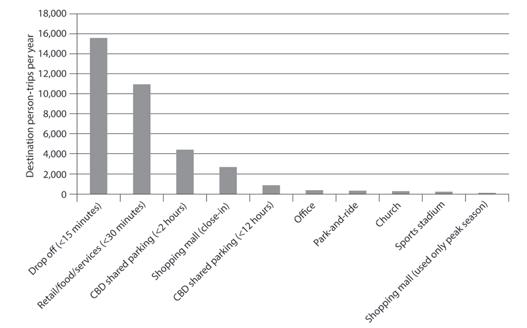

Figure 1-2 Person-trips served per year, by type of parking space 5

Figure 1-3 Relationship of use intensity and sharing 5

Figure 1-4 “Set it and forget it” parking management 6

Figure 1-5 Peak-hour bus lanes as a better use of curb parking in Los Angeles, California 9

Figure 1-6 The wastefulness of exclusive parking in Pleasanton, California 12

Figure 1-7 Shared parking in South Pasadena, California 13

Figure 1-8 Wasted shared parking opportunity 14

Figure 1-9 Crowded housing yields crowded parking in Huntington Park, California 15

Figure 2-1 Parking management concept map 31

Figure 2-2 Excessive parking rules in Culver City, California 49

Figure 2-3 Reserved parking wastes spaces in El Monte, California 50

Figure 3-1 Strategic planning process 60

Figure 3-2 Developing a parking management strategy 65

Figure 3-3 Space occupancy map for Redmond, Washington 73

Figure 3-4 Parking intercept survey form for Vancouver, Washington 80

Figure 3-5 Elements of a participatory workshop 85

Figure 4-1 Parking branding in Seattle, Washington 117

Figure 4-2 Graphic communication and branding in Burbank, California 118

Figure 4-3 Facility identification in Portland, Oregon 119

Figure 4-4 Facility presentation at the 4th and Yamhill garage in Portland, Oregon 121

Figure 4-5 Effective static signage in Seattle, Washington 122

Figure 4-6 Dynamic signage for parking options in Seattle, Washington 123

Figure 5-1 Parking design and aesthetics in Copenhagen, Denmark 167

Figure 6-1 Parking revenue for local improvement in Pasadena, California 176

Figure 6-2 Bicycle corral replaces curb parking in Highland Park, California 177

Figure 6-3 Parklet replaces curb parking in Highland Park, California 178

Figure 6-4 Autonomous solar electric vehicle charger and backup power supply 198

Figure 7-1 Wasted retail parking spaces in Claremont, California 203

Figure 7-2 Mass-produced parking in Los Angeles, California 204

Figure 7-3 1111 Lincoln Road mixed-use parking facility in Miami, Florida 214

Figure 7-4 Bicycle parking replaces vehicle parking in Cambridge, United Kingdom 215

Figure 7-5 Micro-units in a parking structure in Atlanta, Georgia 216

Table 1-1 The differing value of a parking space 3

Table 1-2 Benefits of strategic parking management 8

Table 2-1 Transportation, parking, and land use management across sectors 30

Table 2-2 Styles of parking management 36

Table 2-3 Organizations that manage parking 41

Table 2-4 Parking management by type of parking 43

Table 2-5 Parking management by systems and administration 45

Table 2-6 Parking management by organizational role 46

Table 2-7 Basic parking management in a commercial district 47

Table 2-8 Intermediate parking management in a commercial district 47

Table 2-9 Advanced parking management in a commercial district 47

Table 3-1 Local government stakeholders 61

Table 3-2 Private sector stakeholders 62

Table 3-3 Nonprofit stakeholders 63

Table 3-4 Individuals as stakeholders 64

Table 3-5 Parking issues by concern and organization type 70

Table 3-6 Types of parking management practices 83

Table 3-7 Types of evaluation results 93

Table 4-1 Comparison of business district off-street parking supply and occupancy 100

Table 4-2 Turnover and stall value in Vancouver, Washington 101

Table 4-3 Parking revenue performance in Laguna Beach, California 132

Table 4-4 Cost versus revenue in Temple City, California 133

Table 4-5 Break-even analysis for attended park-and-ride parking in Anaheim, California 134

Table 5-1 Effective parking management strategies 138

Table 5-2 Direct monetary measures 140

Table 5-3 Indirect monetary measures 144

Table 5-4 Direct nonmonetary measures 146

Table 5-5 Indirect nonmonetary measures 148

Table 5-6 Implementation measures 149

Table 5-7 Best practice strategy case studies considered 151

Table 5-8 Employer programs affecting parking quantity or use efficiency 160

Table 6-1 Top five parking myths 174

Table 6-2 Guidance for setting parking prices 180

Table 6-3 Procedures for adjusting prices 183

Table 6-4 A framework for considering the consumer tolerance of frequent parking price adjustments 184

Table 7-1 Smart growth and strategic parking management 208

In 2013, I wrote Parking Reform Made Easy to make the case that planners should reform minimum parking requirements. That book provides a method to recommend revision or elimination of minimum parking requirements. In giving book talks, it became obvious that failures of parking management impede parking requirement reform. Parking management increases parking efficiency and solves unintended impacts of parking requirement reform, such as parking spillover. Without it, local officials have no answer to stakeholder worries about parking shortages even though the number of parking spaces in the United States outnumbers the number of vehicles by a factor of more than three. The purpose of this book, therefore, is to help planners, local officials, business groups, and parking operators develop state-of-the-art parking management strategies that release the stranglehold that parking has on development patterns. Parking Management for Smart Growth shows how to create a strategic parking management program that is comprehensive, coordinated, and supportive of local goals.

I am indebted to parking consultant Rick Williams, a parking expert based in Portland, Oregon, who wrote chapter 4 and provided advice on the other chapters. I have worked with Rick on many parking consulting assignments and have learned a great deal from his goodwill, knowledge, and experience. Also, I am grateful to the dozens of consulting clients over the past thirty years who have given me insight into what works and how to get it implemented.

My former professor Donald Shoup spurred my interest in parking policy and supervised my UCLA dissertation on the responsiveness of parking demand to price. We all owe a debt to him for his brilliant parking research and his landmark book, The High Cost of Free Parking. I also want to thank Cal Poly Pomona students, Matthew Diemer and Aiden Irish, who provided research, editing, and images for this book. Thanks also to Cal Poly Pomona alum and parking research collaborator Arianna Allahyar, who provided images and insightful comments on the draft. I am grateful to UCLA colleague Elizabeth Falletta, who offered valuable suggestions. Finally, I benefited from financial support for this project from the Research, Scholarship, and Creativity Activity program at Cal Poly Pomona.

I am thankful for my wife and fellow urban planner, Robin Scherr, who tolerated my distraction with this book and provided rich insights on economic development and city management perspectives as well as excellent editing suggestions. My

children, Jenna and Maya, are still mystified by the role of parking in academic life but are tolerant and supportive.

Finally, I would like to thank my editor at Island Press, Heather Boyer, for her interest in the topic and her wise advice.

Parking can be a useful and user-friendly aspect of the land use and transportation system if it is treated as a valuable community asset. This book shows how to strategically manage parking resources and, in the process, make parking stakeholders happier and communities more sustainable and prosperous. In downtowns, the parking management agenda is to better use scarce and expensive parking resources with sophisticated shared parking arrangements, real-time parking guidance, and dynamic parking pricing. Parking management allows downtowns to reduce the total parking inventory while growing and prospering. In suburban areas, where parking is generously supplied, the parking management agenda is to introduce parking controls, parking pricing, and sharing arrangements so that current oversupplies of parking can be more fully used and also serve new development, slowing or stopping the growth of parking supply. Since the number of parking spaces in the United States exceeds the number of cars by a factor of more than three, strategic parking management can forestall building new parking for decades to come, saving the money and land for better uses, including parks, urban agriculture, child development centers, affordable housing, and tax-producing commercial spaces. Strategic parking management supports sustainable development.

On the surface (pun intended), the parking space is mundane. It sits passively, is often unsightly, and performs one function—storing a vehicle. Worse, it is empty much of the time. Residential parking is underused during the day when people are at work, and workplace parking is underused in the evening when people are at home. Yet parking is a central issue in community development and a big part of the daily lives of city administrators, residents, employers, employees, and retailers. Disparate stakeholders who agree on nothing else unite in their dissatisfaction with parking. For many, a free parking space is a right, and it should be available directly in front of their destination. So, while the parking space is passive, the opportunity and excitement lies in how it is used. Recognizing the importance of the “sharing” economy, in which technology facilitates frictionless sharing of resources rather than ownership, provides a model for parking management opportunities. Downtown curb parking

(on-street surface parking in the public right-of-way), for example, has always had qualities of the sharing economy—it is collectively owned, managed for efficient use, and used by many different people over the course of the day. The question is: how can sharing economy concepts make better use of existing parking?

The “worth” of a seemingly generic parking space varies. Some spaces serve dozens of parkers per day, whereas others are seldom or never used. A never-used parking space is worthless—in the sense of not serving any transportation purpose. At the same time, that parking space has onetime and ongoing costs for land, construction, administration, and maintenance. A recent estimate placed the annualized capital and operating cost of one space at $854 for a suburban surface lot, $2,522 for an urban three-level structure, and $4,363 for an underground central business district (CBD) space (Nelson\Nygaard and Dyett & Bhatia 2012). Parking also has opportunity costs, such as other forgone uses for that land or building area, and negative externalities, including polluted storm water runoff, heat island effects, and negative design impacts. Strategic parking management reduces the number of worthless spaces so that less total parking can provide the desired land use and transportation benefits.

Parking spaces have standard size characteristics, but the worth of each space depends on how it is used. Table 1-1 shows a variety of parking conditions, ranging from a parking space that is almost never used to a parking space that is used many times per day, most days of the week, and most months of the year. It adopts a metric of destination person-trips per space per year, which accounts for the days used per year, the arrivals per day, and the number of persons in each vehicle. For example, a shared parking space in a mixed-use district serves office workers during weekdays, shoppers on weekday evenings and weekends, and residents overnight. Such a shared space provides more value than a parking space at a sports and entertainment venue, which is used only on event days. Figure 1-1 shows a parking lot at Angel Stadium of Anaheim, in Anaheim, California. The lot is used only during baseball games and other events, and the spaces in the foreground may be used only when the venue is full. The major league baseball season includes eighty-one regular home games, and given that not all of the games sell out, the spaces in the foreground of the picture are used on even fewer days per year. Even when they are used, they are used for less than one quarter of the day. The rest of the time, this valuable land, located in the heart of Orange County, provides no economic or social use.

The varying worth of a parking space is not well understood by policy makers and the public, and too seldom are efforts made to maximize its value. Figure 1-2 displays an illustrative estimate of the number of destination person-trips per year served by a parking space to nonhome destinations, such as retail outlets or offices. Parking spaces serving land uses that operate throughout the year, and with fast turnover, naturally serve the greatest number of trips. Parking for short-visit retail and

Table 1-1. The differing Value of a Parking Space

Daily OccupancyTurnoverTypical Uses Served

Empty or seldom used Low any land use where more parking was built than used

Annual Destination Person-Trips per Space (illustrative) Value

<100

no value; opportunity cost for other uses of the land; negative impacts

Well used but only on certain days Low religious institutions, spor ts facilities 100–300 as above when not used; valuable to the specific use but not to the broader community

Well used on most days in certain seasons

HighShopping mall parking (if built to supply holiday period peak occupancy)

Closest to entrance: ~2,500

Farthest from entrance (only used during peak season): ~200

Valuable if close to the entrance; value declines with distance

Well used most days, all year Low Single uses: office buildings, parkand-ride facilities, residential uses

HighDowntown commercial parking with sharing between uses with short visits

~400 Valuable to the specific use but empty when the use is not active

1,500–30,000Maximizes the value of the space for multiple uses; requires parking management

food uses and CBD curb parking score highly, and occasionally used spaces such as a baseball stadium or the least convenient spaces at a shopping mall (which are used only a few days a year) score poorly. Figure 1-3 arrays intensity of use by level of sharing, showing the desired combination of high-intensity of use and high sharing. The arrows indicate the goal of increasing sharing and increasing intensity of use. This perspective emphasizes use value rather than seeing each space as having uniform attributes. In addition, low-use spaces are prime opportunities for shared parking since they are available much of the time. Understanding parking in terms of its use value in connecting people to trip destinations opens the door to a wide range of parking management strategies that increase efficiency and support community goals.

A generous parking supply at every site can preclude the need to manage parking, as each development site is a self-sufficient parking “island.” If there is plenty of parking available at every site, everyone can find a space, when they want and where they want. These assumptions are embedded in zoning codes, where minimum parking

requirements usually force developers to build more parking than they would if the market determined parking supply. This issue has been addressed by Shoup (2011b) and Willson (2013) but is not the focus of this book. Nonetheless, minimum parking requirements and parking management are inextricably linked. Excessive minimum parking requirements preclude the need for parking management. Conversely, minimum parking reform requires parking management to address such issues as spillover parking. Better parking management is the key to making parking requirement reform possible.

The problems of overbuilt parking have been chronicled by researchers who identify negative impacts on land use, transportation systems, economic development, and social equity. Further, the land use and transportation impacts produce negative environmental outcomes, as described later in this chapter. In response, cities are reforming zoning code mandates for private developer parking by eliminating requirements (Shoup 2011b) or reforming them (Willson 2013).

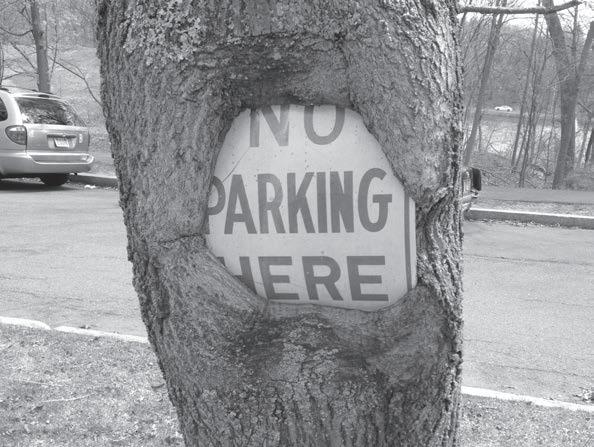

In searching for a way to explain the transition from emphasizing parking supply to emphasizing parking management, I found a tagline from an early infomercial

Figure 1-2. Person-trips per year, by type of parking space

Figure 1-3. relationship of use intensity and sharing

for smart

for a rotisserie cooker that says it best. The pitchman implored the audience to “Set it and forget it,” emphasizing ease of use in roasting a chicken. Frequently, public officials take a similar approach. They “set it” through high parking requirements or expensive public parking projects—and set it so high that there will never be a parking shortage—that way, they can “forget it” when it comes to parking management. “Set it and forget it” seems to have reached a new level in figure 1-4. Most cities do not leave parking signs so long that trees grow around them, but travel around your community and consider how long some parking regulations have been in effect with no change, despite the fact that land uses, demographics, travel patterns, and parking use change in a dynamic fashion. Programs to share parking, to coordinate between land uses, or to price parking are ignored. This impulse is understandable in both parking and cooking chicken—but this approach to parking lies at the center of livability problems in many communities. Seeking to “outsupply” parking use is a recipe for bad planning outcomes.

Figure 1-4. “Set it and forget it” parking management Image

Strategic parking management would not matter if plenty of low-cost land was available for parking construction. However, this is no longer the case in suburban areas, where land costs are higher than before, or in urban areas, where vacant land is rare, parcels are expensive, and land assembly is costly and problematic. A better course is to ensure that existing parking spaces are well used. Parking management reduces the need to build parking for future development and allows parking supply to be reduced if better uses exist for the land or building area. The latter instance occurs when on-street curb spaces are converted to parklets, bicycle corrals, sidewalks, outdoor dining, or bus lanes, and more productive land uses replace off-street surface parking. Finally, parking management improves the prospects for the development and use of alternative travel modes. For example, higher parking charges induce some travelers to walk, bicycle, use transit, or be dropped off.

This book provides a path forward for strategic parking management in a new era in which parking requirements are lessened or eliminated, under-used parking is eliminated, and multimodal transportation is improved. This era of tighter parking supplies requires strategic parking management. The book offers a set of tools and a method for strategic parking management so that communities can better use parking resources and avoid overbuilding parking. It helps stakeholders manage public and private parking resources so that the greatest benefit is gained from every parking space. Table 1-2 provides examples of the community benefits of parking management.

The benefits of strategic parking management are meaningful and extend beyond parking itself. Figure 1-5 shows a parking management strategy in the city of Los Angeles that prohibits on-street parking during rush hours to create a dedicated bus lane in the curb parking lane. Consider how many person-trips per day are accommodated with this bus lane, which speeds peak-hour bus operations, makes buses more competitive with driving, reduces bus operating costs, increases fare revenue, and moderates traffic. Consistent with the goal of efficiently using resources, the lane reverts to curb parking during off-peak hours, when congestion is lower and the bus does not have a travel time advantage from using an exclusive lane.

Strategic parking management memorializes goals, implementation commitments, and phasing. It offers a managed implementation process as well as stakeholder and public agency accountability. As with any plan or strategy, however, benefits are not limited to the direct outcomes. Strategic parking management also has benefits as a process: it brings stakeholders together to share concerns, educates stakeholders about parking management and broader community development issues, and coordinates the many parties involved in parking. This can lead to new forms of coordination and collaboration, new institutional relationships, and heightened deliberative capacity concerning parking. Finally, strategic parking management bridges product

Efficiently use existing parking Produces faster turnover in the most popular spaces and better use of lesspopular spaces. Pricing schemes produce vacancies on each block face. information systems guide parkers to available spaces.

avoid excessive expenditures on parking reduces the need to build additional public or private parking, which saves money and land, facilitates compact development, and reduces land consumption.

Enhance economic developmentSupports new business formation and business expansion by reducing the burden of providing parking. Districts with active parking management have a good image; access is easier. The parking experience is an integrated part of the experience in stores, restaurants, and businesses. improve consumer parking and access options. improve facility design and smart growth implementation.

Reduce traffic, safety, and environmental problems

Supports broad mobility management. Management tools reduce overall parking demand and cruising for parking—the process of circling for parking spaces. reduced cruising lessens vehicle miles traveled, congestion, and instances of distracted drivers, which makes pedestrians and cyclists safer. Parking management supports transit use, walking, and bicycling and lowers energy use, pollution, and greenhouse gas emissions. reduces total parking lessens stormwater runoff, water pollutions, and heat island effects.

Reduce conflicts between districts residential permit programs prevent intrusion by parkers destined for retail districts, medical centers, universities, and other activity centers. alternatively, parking can be allowed with pricing mechanisms that return revenue to neighborhoods.

generate revenue and improve social equity

Revenue from parking fees and fines is directed to parking, other forms of access, and district improvements. revenue can be used as matching funds for grants, and reduces prevalence of cross subsidies from nondrivers to drivers.

and process in generating ongoing management of parking resources and systems with real-time information, adjustment procedures, and coordination protocols.

Without parking management, parking is a free-for-all—a competitive sport—with arbitrary winners (those lucky enough to find a prime space) and losers (those who don’t find one). In mixed-use districts, shoppers, employees, and residents compete for the same spaces. The classic case is on-street parking in front of a store. The store owner may arrive first thing in the morning and enjoy the convenience of parking

there, as may the store’s employees. Over the course of the day, though, perhaps ten or fifteen customers could park in each of the spaces, or the space could be used by many more customers picking up bulky items or by trucks delivering inventory. Which of these is the better use? Without parking management, that question is not asked. Instead, parking is on a first-come, first-served basis, resulting in costly unintended impacts.

Parking is a contested space because many uses compete for the land or building area the parking occupies. An on-street parking space can be used for traffic lanes, bus lanes, bus stops, bicycle lanes, sidewalks, or sidewalk bulb outs. Tactical urbanists propose parklets, sidewalk cafés, performance spaces, and many other uses. Spurred by the “complete streets” movement, communities are considering the opportunity cost of devoting scarce public rights-of-way to parking. In the suburbs, urban designers, economic developers, investors, and real estate developers consider vast swaths of underused off-street parking and envisage other uses—parks and open space, bioswales, street-oriented infill development, mixed-use development, transit terminals, and the like.

Parking is also a contested space because it is an extension of the driver’s personal domain. Unlike walking, bicycling, or transit—where people share public spaces— drivers experience their car as an extension of personal space, a part of their home. Improvements in vehicle technology have reinforced this feeling. Drivers view the world through windshields that have dimensions similar to their high-resolution televisions, with windows up, air-conditioning or heat on, audio entertainment provided, and perhaps their e-mails being read to them. Considering these features and the time spent in the car, it is easy to see how this space is an extension of the driver’s home. Seen this way, a driver’s perspective when looking for a parking space is that what is at stake is the driver’s home, rather than finding storage for a “mobility machine.” The heightened emotions brought to parking issues highlight this critical perception. Parking conflicts are fodder for many forms of popular culture—stand-up comedians, episodes of the television comedy Seinfeld, and commentaries on the state of civility. The cable network Arts & Entertainment features a show called Parking Wars, which finds drama and entertainment in parking enforcement activities:

From the mean streets of the Bronx to the antics of outrageous characters on Staten Island to New Jersey’s capital city of Trenton, these independent towing companies face off with illegal parkers who go to volatile extremes to keep their cars from being towed. ( Parking Wars website 2013)

Presumably, parking enforcement relates to the “entertainment” rather than the “art” portion of the network’s name.

Unmanaged parking leads to undesirable community outcomes. The negative impacts fall into four categories:

• Land use. Unmanaged parking is correlated with oversupplied parking, since the lack of management leads public officials and developers to require or provide large supplies of parking for each development. Figure 1-6 shows a suburban area located along Interstate 580 in the San Francisco Bay area served by the BART Dublin/Pleasanton rail station. Each site provides enough parking to respond to its peak occupancy level. This reduces the density that can be achieved on each site and citywide. Large office complexes are surrounded by parking (only partially occupied), smaller-scale residential uses have spaces in garages, and corridors of commercial uses have surface parking. The separation of different land uses, such as office, retail and residential, means that parking resources cannot be easily shared between uses. The overconsumption of land associated with low density and a lack of shared parking leads to negative environmental impacts, such as consumption of valuable habitat, higher pollution, greater energy use, and increased water consumption. This is the land use and urban design legacy of the “set it and forget it” approach to parking.

• Transportation. Unmanaged parking is underpriced parking, which incentivizes ownership and use of private vehicles. Underpriced parking also undermines the economics of alternative transportation, including transit, walking, cycling, and shared rides. High levels of vehicle use increase regional vehicle miles traveled (VMT). Unmanaged parking also creates excess local VMT in urban areas as distracted drivers drive around (called “cruising”) looking for available spaces. It increases pollution, energy use, and greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, and has secondary impacts in such areas as groundwater pollution and ecosystem impacts.

• Economic development. Unmanaged parking is a drag on economic development. In suburban areas, the lack of shared parking lowers development potential by misallocating land to parking. In built-up areas, it is a restriction on reuse, infill development, and redevelopment. Business formation is slower since perceived parking problems affect city regulations. Built-up areas do not display a dominance of parking, but they have problems as well. Figure 1-7 shows a core district in the city of South Pasadena, California. In this incremental, fine-grained development pattern, parking does not dominate the streetscape. On-street parking is free, so it is difficult to find a parking space at times. The high occupancy of curb parking on popular streets makes

it feel as if there is a parking shortage when in fact there is not. Retail employees may outsmart the simple two-hour time limit for on-street parking and use the most valuable on-street spaces, moving their cars every two hours or hoping that enforcement is lacking. It makes no sense for employees to park in the most convenient on-street spaces, since perhaps a dozen or more shoppers could use the same space over the course of the day. Better parking management produces more retail sales and tax revenues because the business district is offering more convenient, closer-in parking spaces to shoppers.

Unmanaged parking also produces artificial parking shortages, such as when banks’ off-street parking is well used during the day but largely empty in the evenings and on weekends. If a resurgence of restaurants and bars occurs in historic structures that were built before parking requirements, the banks may notice that restaurant patrons are using their spaces in the evening. In response, they often put a chain across the lot entrance at night. Nighttime restaurant patrons find that on-street and public off-street spaces are full, so they park in surrounding residential neighborhoods, producing a community

backlash. The lack of shared parking agreements produces an artificial parking shortage. Figure 1-8 shows a typical lost opportunity—an off-street lot closed off to daytime users with a gate and a no parking sign.

• Social equity. Unlike land use and transportation, the social impacts of unmanaged parking are less visible. Unpriced parking privileges those with cars, and creates a cross subsidy in wages, and the price of goods and housing from those without cars to those with them. This is because expenditures are made to provide parking for those with cars, but those expenditures are paid by all shoppers and are reflected in lower wages and higher housing prices. Onstreet parking in residential neighborhoods such as Huntington Park, California, is jammed because of large households (and multiple households) in each unit and because some of the existing off-street parking may not be used

Figure 1-8. Wasted shared parking opportunity

Image source: Aiden Irish

for parking. Instead, garages may be used for storage or may be illegally converted to housing. The anxiety about parking, as well as complaints to elected officials, produces such reactions as increasing minimum parking requirements for types of housing that might experience high household sizes. This has the intended effect of discouraging development because of the high cost of construction. On-street parking is not managed and priced as the valuable public asset that it is. Figure 1-9 shows a neighborhood in Huntington Park, California, that has a high population density (19,270 persons per square mile in the 2010 census) in neighborhoods that were originally designed for lower population densities. The community therefore experiences extreme pressure on parking resources that calls for innovative parking management.

Parking use is the aggregation of individual driver responses to the parking facilities, services, rules, and pricing structures offered by private and public entities. Parking

behavior is largely predictable. Economic theory about “utility-maximizing” consumer parking behavior explains many of the choices as to whether to park, where to park, how long to park (duration), and the search method for finding a parking space. Parkers consider trade-offs between out-of-pocket parking price and proximity, parking search time, and parking convenience in deciding where to park. Parking is a part of a consumer decision-making process for the overall trip, which economists define as a derived demand. People demand transportation and parking spaces not for their own sake but, rather, because they allow participation in a desired activity, such as shopping, visiting a friend, or going to work. Because of this, we can assume that most drivers seek to minimize parking cost in balance with accessing desired activities, walking distances, convenience, and other factors, such as personal safety.

The implication of this economic theory is that drivers will respond to changes in price and the other factors in a relatively predictable way. Thus, we can be assured that changes in parking use rules, pricing, and supporting services can address spot parking shortages, complaints about finding spaces, and so on. Overall, the evaluative

research shows that basic economic factors, such as price and walking distance to the destination, explain a large part of parking behavior.

Having made a claim about the rationality of parking behavior, there is admittedly an irrational dimension as well. Rhetoric about parking includes statements such as “I’ve always parked in this spot,” “I don’t park in parking structures,” “the lack of parking is killing my business,” or “free parking is my right.” Typically, the economic concept of demand (how much parking would you consume at what price?) is lost, and stakeholders discuss their various parking “needs.” When the hyperbole gets thick, it is almost as if parking is elevated to the status of a human right. This, of course, is false reasoning, since any individual parking space is part of a multifaceted system of travel choices, residential location, work and shopping location, and so on.

Parking is a competitive sport for some, and for others, a way to channel generalized rage against perceived authoritative systems and society. Residents experience frustration in looking for spaces, and lower-income residents experience financial setbacks from tickets and vehicle impoundment. Ordinary people do not have any interest in understanding the policy framework for parking enforcement or the issues involved in setting up and maintaining an enforcement system. Therefore, parking management strategies have to address these qualitative and intangible issues as well as traditional economic reasoning.

Parking management should anticipate the future because economic, social, technological, and environmental conditions affect the types of strategies that should be used. Thinking about parking’s use value is an important step in creating better land use and transportation policy. This perspective is reflected in the transition from parking as a component of real estate to parking as a service that is responsive to neighborhood or district goals (Gander 2014). Even if a parking space is well used, however, that does not mean that it should exist. Parking spaces are often occupied because the deck is stacked against alternative transportation modes—they are not available or convenient. Communities with aggressive plans for transit and active transportation need strategic parking management to make those plans effective. This section reviews trends in economic organization, urban development patterns, the environment, culture and preferences, and technology.

Economic theorists describe much of the twentieth century’s economic organization as “Fordist,” using Henry Ford’s production line as an analogy to an era of mass pro-

duction of standardized goods. The emphasis was on the quantity produced in a costeffective way via mass production of identical cheap goods. Product differentiation, variety, and personalization were rare. Parking is not normally thought of in these terms, but it can be seen as supporting the agenda of mass production of automobiles, suburban expansion, and a consumerist economy. Following World War II, local jurisdictions forced developers to provide ample quantities of parking to support suburban development—parking was seen as an essential element of the transportation system, provided for all on the same terms and with no differentiation. Zoning codes mandated the “production line” of mass quantities of parking, which also meant that those spaces were offered free. The result of this approach was vast swaths of surface parking in much of suburban North America. Parking was part of the consumerist ideology in which automobile mobility was assumed to be the superior mode of personal transportation.

The current economic era is considered “post-Fordist,” referring to an economic organization appearing in the 1970s following oil price shocks, globalization, and privatization trends. This era emphasizes small-batch production, flexibility, specialization, integration of information technologies, and a general rejection of “one-sizefits all” approaches. Although these concepts are usually applied to the production of goods, the rise of parking management can be seen as part of this post-Fordist economic organization, in which flexibility is prized, goods and services are targeted to market niches, and technology is used to match the product (in this case, parking) to the consumer. An emphasis on things is replaced by an emphasis on services, communication, branding, and identity in the consumption of goods. Those growing up in this era are accustomed to choices in their consumption. Goods and services that are not “smart” are rejected.

Given this transition in the nature of the economy, strategic management is an essential element of all transportation systems. We are in the midst of a transportation reconceptualization, moving from a focus on building transportation infrastructure and turning it over to unmanaged use, to actively managing systems of access and mobility. For example, the introduction of high-occupancy toll (HOT) lanes provides drivers with an ability to trade shorter travel time for money, depending on their priorities. HOT lanes also reflect the management approach since tolls are set in real time to keep the facility from slow travel speeds that would lessen vehicle throughput. The ideas advanced here bring that same “smart” management approach to parking. This trend is accelerated by transformation brought about by the sharing economy, and technological innovation offers unprecedented tools for parking management. The future will bring more demand for smart parking services that respond to individual demands.

Parking production is largely determined by the minimum parking requirements in zoning codes. They specify how much parking must be provided with each new development or conversion of use. The greatest new parking construction per unit of development occurs in suburban development, where (1) parking requirements are high, (2) greenfield development patterns mean that development rarely replaces existing parking lots, (3) the greater center-line miles of roadway per unit of development provide more on-street parking, and (4) setbacks produce parking in driveways and aprons. Given these factors, the post–World War II suburban expansion was a period in which the number of parking spaces added per unit of development was highest. This development phase is the primary reason that parking supply exceeds the number of vehicles by a factor of three or more.

In contrast, urban development often occurs as redevelopment, brownfield development, or adaptive reuse. The four factors mentioned above are reversed. Parking requirements are lower or nonexistent, surface parking inventories are often displaced by development, development does not add on-street parking associated with new roadway construction, and denser land use patterns do not offer informal parking spaces. In addition, there are more alternatives to vehicle ownership in urban areas, because these areas have better transit systems, more walkable destinations, and more temporary vehicle use options. Development patterns have shifted toward urban redevelopment and infill in the last quarter century, as suburban expansion has been slowed by development regulations and environmental constraints. In contrast, the market for urban infill development has strengthened, and the real estate industry shows more interest and skill in generating dense, mixed-use infill developments. The annual pace of net parking additions is declining in most cities.

The shift in development patterns described above means that the rate of increase in total parking inventory is slowing and there will likely be a peaking of total parking supply in the future. The rate of this change will vary from city to city depending on each city’s circumstances, but the implication is a lower ratio of parking spaces to vehicles, which will require strategic parking management to get the most value out of each space.

Parking is complicit in many environmental problems, including such direct impacts as contributing to polluted groundwater runoff. It is the indirect impacts that are perhaps more significant, because parking facilitates private transportation and the associated energy use, air pollution, noise impacts, and the like. Environmental mitigation strategies have managed some of these impacts, but global climate change is the most pressing future environmental issue. Parking facilities serve private vehicle transpor-

tation that predominantly burns fossil fuels. The role of private transportation in total greenhouse gas varies by state, but it is one of the largest components of emissions. Because global actions to reduce GHG concentrations have not been effective thus far, drastic measures will be required in coming decades. Although the development of electric and alternative fuel vehicles that rely on renewable energy is a possibility, market uptake is slow and the existing fleet changes slowly.

As the problem of climate change worsens, governments may be compelled to adopt restrictions on private vehicle travel or to price such travel in a way that reflects the external costs of vehicle use. This, in turn, will reduce VMT and the use of parking. At the same time, more expensive parking creates an incentive for the use of transportation modes that are less carbon intensive. Parking management will be used to manage decreases in parking supply, on an absolute and per capita basis, as parking lots are converted to more productive uses. Those surface lots that remain will be called on to contribute to carbon sequestration through tree planting. Parking facilities will also be greened through green maintenance materials, rainwater harvesting, energyefficient lighting, water-efficient landscaping, and green cleaning products. Parking management also plays a role in climate adaptation. As local temperature increases and extreme heat events occur, parking lots will require shading to protect pedestrians from heat impacts.

Cultural trends are hastening changes in parking management. Many millennials prefer urban environments, embrace car-free lifestyles, delay getting a driver’s license, and exhibit preferences for walking, bicycling, and transit use. They are using technology to stay connected and to replace trips. At the other end of the age spectrum, baby boomers and prior generations are encountering physical limitations that curtail driving. The walkable, mixed-use environments that both groups prefer have different trip-making patterns—trips may be more frequent but shorter, with more transit, walking, or bicycle use. More time is spent in public spaces, coffee shops, and other meeting places. These shifts reduce parking occupancies, all else being equal. Those who do drive and park expect rich information on parking alternatives and prices, as is demonstrated in the proliferation of cell phone apps. The demand for differentiated parking markets, pricing, and service levels will continue to grow.

A current Cal Poly Pomona graduate student and a recent Cal Poly Pomona alumna assisted in research tasks for this book. Both are in their mid-twenties. The graduate student lives in Pomona, thirty miles east of downtown. He owns a car but uses it only when absolutely necessary. Cycling is his preferred mode of travel. The alumna lives in a close-in Seattle neighborhood and does not own a car, instead relying on walking, biking, and transit. For these two people, parking is outside of their direct

experience and concern. Rather, their focus is on the quality of transit service, the safety of bicycle routes, and good conditions for walking. This is a stunning change in culture, and a surprise to an older generation who learned during the suburbanization of America that plentiful cheap parking was essential to a thriving community. It is no longer true.

Recently, I asked students in an incoming graduate urban planning class about their planning focus, and the most frequent answer was “active transportation.” There is a clear trend away from automobile ownership and solo driving among young people. One view is that these young people will increase vehicle ownership as they age, but after having observed these social trends for over four decades, I find that these changes are more permanent and systemic than a temporary, age-specific phenomenon. Parking supply will diminish in importance as car-free lifestyles become more common, but parking management will be essential to manage use of the reduced parking supplies accompanying this transition.

Trends in technology and culture can hardly be separated because they exist in a dialectal relationship. Social and cultural needs beget technological innovation, and technological innovation accelerates and shapes cultural change. This two-way relationship is especially true in parking management. Technology is improving the parking experience with better information about space availability and price. It is also improving the performance of driving alternatives, such as temporary car rental programs, taxi competitors, autonomous vehicles, real-time ridematching, and real-time information on transit arrivals. These new services have the effect of lowering household vehicle ownership and lowering vehicle use for some trips. How fast this reduction occurs depends on whether a community has the size, density, and land use mix threshold to support them. In such locations, parking occupancy per unit of development will decline. In other locations, it will be decades before a concept such as car sharing is feasible. A final point about technology is that the increased demand for alternatives to driving makes the economics of providing alternative modes, such as transit and shuttles, more feasible since there is more robust demand and fare revenue.

Autonomous vehicles deserve special note because they could be thought of as countering the trend of reduced vehicle use by providing personal mobility for millennials who do not drive and for boomers who have stopped driving. Automobile makers are aggressively applying technology to keep private vehicles relevant. As the share of autonomous vehicles in the fleet grows, however, their impact on parking resources will be less than if they were traditional vehicles. Users of autonomous vehicles are less likely to own them, instead using them as car-share services. Their use will be more akin to taxi service than to driving one’s own car to work and there-

fore will reduce the ratio of vehicles per needed parking space. Each autonomous vehicle will be in use more of the time because it is shared by multiple users, reducing the number of parking spaces needed to accommodate such vehicles. Parking management tools will be used to efficiently ratchet down the parking supply as vehicle ownership declines.

Future technology will continue to affect the delivery and consumption of parking services. The first issue is the management of parking facilities themselves. The role of a parking structure, for example, will shift from a one-size-fits-all supply of parking spaces to an interconnectivity hub that provides traditional parking spaces and car-share spaces, specialized spaces (electric car recharging, bicycle parking), linkages to other access systems (bicycling, transit, or individual last-mile services), and other uses, such as energy production on the roof and ground-floor retail. Structures will be integrated in the urban fabric rather than representing a single-use edifice. Parking management will adopt new technology in space-occupancy monitoring and enforcement, allowing pricing policies that differentiate the price by vehicle size.

Parking management strategies will anticipate and aggressively adopt technology that makes better use of existing parking. The pace of change is quick, so forwardthinking, adaptable strategies will win out. Current complaints about parking “chaos” and a lack of certainty about space availability will be moderated by technological services that add parking options and make parking more predictable. Parking pricing and information available will be fully integrated into personal devices and in-car navigation, and there will be many ways to pay for parking. Traffic guidance and parking guidance will be integrated. In dense urban areas, the app-enabled practice of auctioning off parking services in real time will continue to grow.

These trends suggest that parking management will increase in the future and that it will be smarter and more strategic. Smart growth cannot happen without it. This reframing of parking from an object to a service is reflected in the view that parking should not be just an end point in a journey. Parking facilities are part of a suite of multimodal transportation facilities that serve mixed-use resources. As a parking reformer has said, “Parking has a central role in this mobility chain as a strategic enabler for intermodal concepts and a catalyst to foster community renewal” (Gander 2014). Parking must be considered in the context of car sharing, bike sharing, autonomous vehicles, city cars, electric vehicles, e-mobility, the smart grid (including vehicles to grid), intermodal services, and location-based services.

Parking terminology is often used loosely, and sometimes it is used strategically to advance an interest. For example, stakeholders commonly refer to a parking “need.”

Needs are generally elements that are basic to human survival, such as access to clean water, human rights, or shelter. Needs are essential or very important. We argue here that parking does not rise to that level, since there are many ways to get around and many locations to park.

A better term might be parking “want,” as the term want refers to things we desire (e.g., I want a convenient, low-cost parking space close to my destination). As for items that are not essential to human survival, the normal way to address wants is to use the economic concept of demand, which is a consumer’s desire and willingness to pay a price for a specific good or service. The tricky part about calling an observed parking occupancy “demand” is that the price of parking is frequently zero (either with no posted prices or with retailer or employer subsidies). The price is zero because zoning codes have mandated parking supply, and commonly the amount mandated is more than occurs even when the price is zero. The observed demand, therefore, is inflated by the zero price condition. If parking is priced at a cost recovery price, or priced to ration demand patterns, prices will be higher and demand will be lower. Because this is a common condition, we use the term parking use throughout this book to reflect that the occupancy level does not represent demand at a market clearing price in most cases. These distinctions may seem like dancing on the head of a pin, but they are important because there are strategic reasons why people talk about their parking “needs.” They are attempting to frame parking as an essential public good, a need that should be paid for by someone else.

Following are other key terms used throughout the book, drawing on standard industry practice and the International Parking Institute (2013):

• Access and Revenue Control (ARC)—systems that control access and manage parking revenue

• Accumulation—the peak occupancy level reached in a time period

• Attended parking—a process in which the parker drops a vehicle at a station and an attendant parks and retrieves the vehicle, parking in a normal space, stacking vehicles in tandem arrangements or in drive aisles, or parking in remote lots (also called valet parking)

• Automated Pay Station (APS)—allows for automated parking payment in centralized facilities (also called “pay-on-foot” or “pay-in-lane” machines)

• Automatic Vehicle Identification (AVI)—identifies a vehicle upon entry to a parking facility to allow access or exit

• Block face—the area of curb parking along one block, between two intersecting streets (e.g., a single city block would have four block faces)

• Curb parking—parking spaces provided on-street in the public right-of-way (same as on-street parking)

• Duration—the length of time parked (often reported as the average duration for a specific time lot or block face)

• In-car meter—equipment used in a vehicle to pay for parking (usually a hangtag) that is activated when the vehicle is parked and that charges against a fund deposited

• Multispace meter—freestanding parking meter equipment that is associated with multiple spaces, either on-street or off-street

• Occupancy—the number of spaces in a facility that are occupied at a given time divided by the total spaces in that facility (sometimes called utilization)

• On-street parking—parking spaces provided on-street in the public right-ofway (same as curb parking)

• On-street parking fees—charging a fee for parking in on-street facilities

• Parking cash-out—the offer made by employers to employees to receive the cash value of parking rather than using a parking space

• Parking demand—the number of occupied parking stalls at a particular moment in time under conditions of market pricing (in the absence of pricing, one cannot consider observed parking occupancy as demand because there is no market price)

• Parking in-lieu fee—a onetime or annual fee paid instead of providing coderequired parking; used for public construction of shared parking facilities or other access services

• Parking occupancy—the number of occupied parking stalls at a particular moment in time

• Parking pricing—charging the parker directly for using a space, using one of a variety of rationales for establishing the charge (such as operating cost recovery, amortized capital cost plus operating cost recovery, and rationing using variable pricing)

• Parking supply—the number of spaces available on a site or in a defined district

• Parking tax—a tax of paid parking, levied as a percent of the parking fee, or a tax levied on a per-square-foot or per-space basis

• Pay and display—a parking payment system in which the parker pays at a station in advance and then displays proof of payment in the parked vehicle

• Pay by cell phone—parking fees charged via a cell phone (can allow added time)

• Pay-by-plate—a parking payment system in which the parker pays at a pay station and enters the vehicle license plate number

• Pay-on-entry—a parking payment system in which the parker pays when entering the facility

• Pay-on-exit—a parking payment system in which the parker pays in the lane when exiting the facility (cashier or credit card payment)

• Pay-on-foot—a parking payment system in which the parker pays at a pay station before exiting the facility and then inserts proof of payment on exit

• Permit parking—a parking system that provides a permission (or credential) for certain groups to park in a designated area (e.g., neighborhood curb parking reserved for residents)

• Permitless parking—a parking system that uses license plate recognition to read preregistered license plates, providing the same function as a permit

• Scofflaw—a repeat parking offender

• Shared parking—a parking system in which two or more land uses share a parking resource because they have different occupancy times

• Single-space meter—freestanding equipment associated with a single parking space, on-street or in parking lots, that accepts either coins or credit cards

• Strategic parking management—a suite of parking management methods implemented to achieve synergy and to support community goals

• Transient—paying for parking on a short-term basis, such as a number of hours or a day

• Travel demand management (TDM)—a suite of travel incentives (e.g., carpool subsidies, ridematching) and disincentives (e.g., solo driver parking pricing) used to reduce the number of vehicles driven alone to work and to increase carpooling, transit, bicycling, and walking

• Turnover—the number of times a space is occupied by a different vehicle per unit of time

• Unbundling parking—charging for parking separately from charging for the rent of a rental apartment, office use, or other real estate

• Utilization—the number of spaces in a facility that are occupied at a given time divided by the total number of spaces in that facility (sometimes called occupancy)

• Valet parking—see attended parking

• Validation—providing a discount to the parker that is charged back to the business or entity giving the validation

Parking management is related to virtually all aspects of urbanization, so there is a need for boundaries in this analysis. The focus on parking management is embedded in two broader topics. The first area, access management, is important because parking occupancy is related to alternative modes of transportation. The more frequently

sites are accessed by walking, bicycling, transit, shuttle, drop-off, and taxi, the less parking is occupied. A full treatment of access management is beyond the scope of this book, but it is an important consideration in comprehensive planning (see, e.g., Tumlin 2012) and will be noted when it is germane. Second, parking management relates to parking requirements in zoning codes (Willson 2013) and to developer and property investor practices. This book deals with these interconnections by drawing in these two related issues as needed, but it keeps the focus on strategic parking management.

At its essence, this book explains how to develop and implement strategic parking management so that all of the pieces work together in a complementary fashion. Chapter 2 introduces the basic elements of parking management, showing how managing parking in a strategic, collaborative manner can (1) lower the ratio of parking spaces per vehicle and (2) more efficiently use existing parking spaces. This is done in a way that seeks to improve customer and stakeholder satisfaction with parking and alternative access.

Strategic parking management is a distinct way of doing business in which measures are implemented, evaluated, and modified over time. This iterative process responds to changing or cyclically adjusting conditions. Unlike parking construction, which produces a fixed, long-lasting improvement, parking management is flexible, reversible, and adaptable and should be thought of as an element of the resilient city, capable of adapting to changing conditions.

Chapter 3 lays out, step-by-step, a strategic planning process for parking management. The many stakeholders involved in the process mean that strategic parking management requires continual collaboration across private, nonprofit, and public entities. Chapter 3 addresses the community participation aspects of parking management, emphasizing methods to develop measures that are tailored to land use and transportation conditions in such areas as business districts, office parks, or residential neighborhoods.

Each community is at a different stage in terms of parking management. For some, the most basic time limits for on-street parking are the appropriate starting point. For others, advanced dynamic pricing schemes that alter parking price by block face, time of day, or season may be appropriate. Chapter 4 provides a practical guide to the steps and processes to manage an integrated parking supply, addressing issues related to setting prices and assessing costs and revenues.

Chapter 5 is a resource for understanding best practices in the individual parking management techniques as well as best practices in comprehensive and coordinated strategies. Although the focus of the book is North America, global best practices are also highlighted.

Implementation issues can trip up even the most advanced strategic parking

management ideas. Chapter 6 tackles key challenges: politics and community participation, technical challenges such as setting prices, implementing shared parking agreements, accessible parking placards and abuse, meter equipment issues, and coordination. It also provides advice on greening parking operations and enforcing parking.

Chapter 7 concludes by showing how parking management fits the broader planning and policy picture. With an eye to the future, it shows how parking management contributes to smart growth initiatives, including multimodal transportation, transitoriented development, integrated urban management, and next generation parking facilities.

The aim of the book is to guide practitioners to use the existing parking supply to produce the maximum community benefit and open the door to parking requirement reform and future shrinking of the parking supply. Obviously, the ratio of spaces per vehicle could never be 1:1, since private garages in single-family homes will never be shared by different uses, but many other forms of sharing are possible. Strategic parking management reduces the ratio of parking spaces per vehicle while increasing economic vitality and stakeholder satisfaction. Local public agencies and private-public partnerships should fully exhaust strategic parking management before resorting to requiring or building additional parking. This is a reversal of traditional practice, which mandates parking first (through ordinances and public parking construction) and then adopts minimal parking management techniques, if any.