7 minute read

Muslim Canadians in the Coming Decade

Muslim Canadians in the Coming Decade Can Muslims move beyond the mosque?

BY KATHERINE BULLOCK

Advertisement

Unhappy with the thought of being conscripted by the Ottomans to fight in Yemen, Bedouin Ferran moved from the Levant to Canada in 1907. In 1909 a Catholic priest renamed him “Peter Baker.” The Indigenous communities in the Northwest Territories, where he worked as an itinerant trader, nicknamed him the “Artic Arab” or, somewhat confusedly, the “Jew.” The local barber and hotel owner, where he often ate while in Fitzgerald, dubbed him the “Black Turk” for his curly black hair.

An enterprising man, one of his claims to fame was keeping the fresh fruit that he sold from freezing. Another one was his 1964 election to the Northwest Territories Legislative Assembly.

A Muslim Arab when there were few Muslims in Canada, we know little about his self-concept as a Muslim, except that his funeral was conducted in 1973 at the Al Rashid mosque in Edmonton — Canada’s first mosque. We also know him to be an enterprising and hardworking man who took the racism he faced in stride.

When he traveled alone on his sled with his dogs, camping out amidst snow glistening on pine tree needles and the track ahead, a vast expanse of sky above, did he connect with his Creator?

Many of us can identify with the feeling of being the lone Muslim in our city, school or workplace. Many of us know the struggle it

takes to reestablish oneself in a new country faced by cultural and language barriers; to smile and carry on in the face of racism, to pass on such qualities as faith, hard work, entrepreneurship and law-abidingness to the next generation.

Since Baker’s arrival in 1907, Muslim Canadians have recognized the need to provide each other the support and mutual assistance commended by Prophet Muhammad (salla Allahu ‘alayhi wa sallam), who stated, clasping his fingers together, “Verily, the believers are like a structure, each

part strengthening the other” (“al-Bukhari,” hadith no. 467; “Muslim,” hadith no. 2585).

Just like the Muslims who migrated to Madina, Canadian Muslims’ first step was to build a mosque to provide a space for daily and Friday prayers and to serve as its spiritual heartbeat. The mosque circulates the oxygen of connection to God through prayer, the vitamins and minerals that give the energy to work and contribute to families and the wider society, the sustenance to support teaching and educating children, the sinews to bind together in mutual assistance and the platelets that stop the wounds of racism.

So what do we do when Muslims don’t come to the mosque? Is the lifeblood that circulates from it carrying toxins or unable to nourish those Muslims?

A 2011 study by Dr. Ihsan Bagby, chair of ISNA U.S.’s Masjid Development Committee, found that many youth, women, converts, minority ethnicities and African-American Muslims feel unwelcome or uncomfortable in mosques. Subsequent research, including a well-known 2014 documentary “Unmosqued,” corroborates this. The U.S. trends are found in Canada as well. Many of these groups stop attending and either live Islam alone or try to establish their own communities.

If we are responsible for all community members and for ensuring that everyone is flourishing, then we need to pay more attention to the unmosqued. Mosque-only solutions to community problems are necessary, but not enough.

Social science studies have identified two clusters of long-term trends, which I call “changing patterns of authority” and “youth struggles.” As only a handful of Muslims are addressing these trends’ fallout strategically, we need to focus on understanding the issues and identifying solutions to these systemic, deeply rooted trends that both contribute to the unmosqued phenomenon and undermine mosque-centric efforts to address community needs.

CHANGING PATTERNS OF AUTHORITY Karim H. Karim’s 2009 study “Changing Perceptions of Islamic Authority among Muslims in Canada, the United States and the United Kingdom” (https://irpp.org/podcast/

changing-perceptions-of-islamic-authority-among-muslims-in-canada-the-unitedstates-and-the-united-kingdom) looked at how Muslim communities are adapting to modernity as Western citizens and what role religious authority played in their adaptation.

Focus group members, when asked about local imams, the scripture and Islamic norms such as the Sharia, cited various problems, among them imported imams who didn’t understand local conditions and many mosques not allowing critical discussions, skepticism and dissent. This latter reality had led many to seek their own answers.

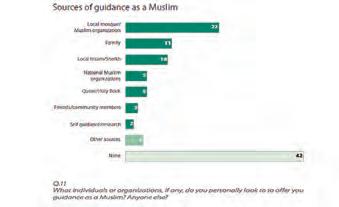

These trends are corroborated by the 2016 Environics survey of national Canadian Muslim opinion (see Keith Neuman, “The Muslim Experience in Canada,” pp. 38-39). Many celebrated that higher numbers of under 45s were attending a mosque for non-prayer purposes, but overlooked the 43% who said they attended for prayer once a month or less, only at special times or never [see Neuman, chart 3].

While 22% of interviewees turned to their “local mosque” as a source of guidance, as many as 42% said they look to “none” as a source of guidance. In the Canadian context, this is around 420,000 people. And 41% and 42% of interviewees, respectively, were not very satisfied with or unaware of youth or family programs.

Sources of guidance

Satisfaction with local community

In sum, local communities reach about one half of the Muslims through mosquebased programs. Obviously, more attractive mosque programs are needed, as well as serious investment in non-mosque programs, perhaps also by non-mosque associations, if we want all Muslims to flourish, unite more deeply and allow more people to experience the guidance provided by the Quran and Sunna.

YOUTH STRUGGLES

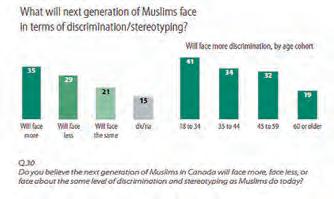

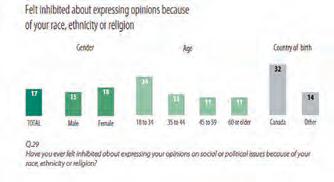

The Environics survey also highlighted some perhaps unrecognized youth struggles. In general, a sense of belonging to Canada was very strong for 55%, but only 45% among women and 41% for youth (aged 18-34). A full 78% of the Canadian born, and 54% of youth, cited discrimination as their local community’s most important issue, compared to 28% for those aged 45 and older. Moreover, 41% of youth and 50% of the Canadian born expect to face more discrimination in the future. Finally, 24% of youth felt inhibited about expressing their opinions due to race, ethnicity or religion; this figure was 32% among the Canadian born.

Next generation face

Feel inhibited

Clearly, many youth feel despair, cast out and isolated from their communities; unsure of their connection to the place in which they live; and uncertain about their future and ability to be empowered, express themselves and live their lives to the fullest.

All of these are connected to one’s self-esteem, a high level of which is essential for mental wellbeing. Wellbeing is, in turn, connected to one’s ability to function and do well as a contributing citizen. If a mosque preaches that “the West” is a toxic environment, that Canadians hate Muslims, that we are always victims of discrimination or of the “unbeliever,” can we expect a young person to have a positive sense of self? And if this is the case, then why are we living here? Why should we care about our city and ourselves?

We must help our youth feel that they belong to Canada; to help them handle discrimination; and provide effective counseling, self-defense classes, self-esteem and empowerment. We need to teach and guide them on how to not give up, provide coping tools, address discrimination and bystander training. And if they are unmosqued, we need to find ways to reach them with these and other programs.

These Environics charts cover a lot of information. While Muslims should be optimistic and feel reassured by the high number of those feeling proud of their Muslim and Canadian identities, as well as their connection to Canada and their sense of the future, we also have to ascertain the trouble spots when planning our institutions and their programs. Many non-mosque activists bemoan the amount of money spent on brick-and-mortar structures that stand empty for most of the day.

I have pointed in this article to the longterm, systemic and deeply rooted difficulties many Muslims face. Such challenges undermine mosque-centric efforts to address community needs.

Baker lived at a time when there were no mosques. If we say establishing a welcoming mosque with programs that cater to everyone, instead of to a select group, is a given, then let’s take our communities to the next level: fund and support organizations and programs that are non-mosque centered while working on the mosque. As a psychotherapist friend puts it, “Instead of calling them to us,

Katherine Bullock, Ph.D., is lecturer in Islamic politics at the University of Toronto.

let’s go to where they are.” ih