10 minute read

Civil Rights in Indiana

Our Fight for Civil Rights

in Indiana

March 15, 1965:

More than 400 marched on Philadelphia Street for civil rights and held a courthouse service for James Reeb, a minister and activist killed in Selma, Alabama.

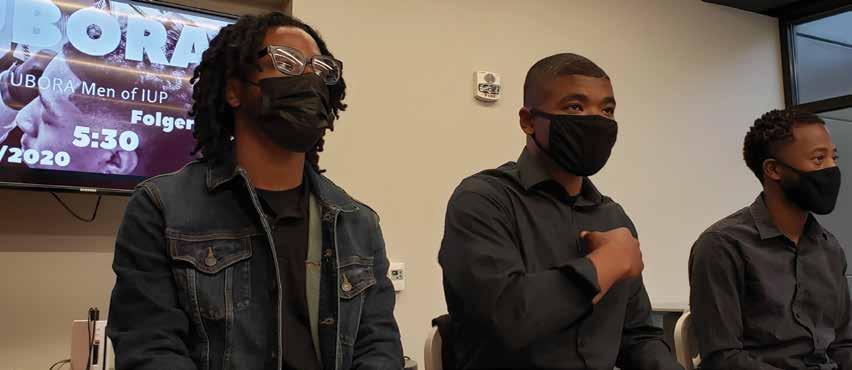

June 3, 2020 (at right):

Roughly 170 gathered in downtown Indiana to support the Black Lives Matter movement and to protest George Floyd’s death at the hands of Minnesota police.

INDIANA GAZETTE

MICHELLE RAYMOND,

THE PENN

Edith Cord in the 1970s

Retired Faculty Member Shares Her Story

By Edith M. Cord

In 1962 my husband, Steven Cord, and I were hired at Indiana State College, now Indiana University of Pennsylvania. Steve joined the Social Studies Department and I the Department of Foreign Languages. Steve was born and raised in New York City. I was originally from Vienna, Austria, and I had managed to survive religious persecution in Nazioccupied Vichy France. Indiana had a small Jewish community, mostly composed of merchants. We learned later that Jews had only recently been allowed to join the Indiana Country Club.

Steve’s large department served as an umbrella for all the social sciences: history, sociology, political science, philosophy, and economics. Eventually the department broke up according to each specialty, but at the time it allowed members of various disciplines to get to know one another. Under the leadership of its chairman, Raymond Lee, the department was very collegial. We became friends with Esko Newhill, sociologist, and his wife, Ruth. We learned from them that housing was segregated in Indiana, and most members of the small Black community, left over from the Underground Railroad, were restricted to living in a rather run-down neighborhood called Chevy Chase. We learned that when Lyman Connor, who was African American, was sent to Indiana as the local administrator for the state’s Health Department, he was not able to buy housing in town, and he and his family had to settle in Chevy Chase.

The Newhills invited us to join them and their Unitarian friends for Sunday brunches at a little pizza shop on the edge of campus. Civil rights were the topic of the day. Our conversations about civil rights led us to get

involved at the local level. Since most of us were academics, the first thing we did was establish a fund to provide scholarships for any post-high school education or training for young Black people from Indiana County. Esko and I were involved with that effort. We approached Earl Handler, a local attorney and future judge. He was supportive of our efforts, and he did the paperwork to create a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization named the Human Relations Committee of Indiana County. We now had official status, and contributions to the scholarship fund were tax deductible.

The 1960s were the time of sit-ins, especially in the South. In 1964, three civil rights workers were murdered in Mississippi by members of the Ku Klux Klan. Two were young Jewish men from New York, and the third was an African American man from Mississippi; all were working for CORE (Congress of Racial Equity). These events prompted our decision to hold a memorial march on Philadelphia Street. We received permission to hold the march, and three blocks of downtown Indiana were closed to traffic for a couple of hours. Our march was well attended by many members of the faculty and by a few townspeople, including Jane McGregor and Clarence Stephenson and his wife, Marcella. My husband and I decided it would be safe to take along our two young daughters, ages 7½ and 5½. Both still remember the solemn march. We started on Ninth Street and headed toward the old courthouse on Sixth Street. The merchants came out of their stores and stared at us. On the steps of the courthouse, there were speeches, followed by singing led by a young woman from the local Black community. She had a lovely and powerful voice. After that, we disbanded without incident.

Margaret Pratt, the wife of Willis Pratt, president of the school, had organized a club for faculty wives called the Dames Club. It was purely social, with many events for the women and a few for couples, like the annual Christmas party, or for families. The club organized a pool party at the local swimming pool. The community pool, which our realtor had shown us with pride, was closed to Blacks. It was in Mack Park, on a piece of land donated by the prominent

Mack family. I should add that in 1963, the year after Steve was hired, the History Department hired a Black professor, Robert Vowels. The organizers of the pool party went to the pool administration to ensure that the Vowels family would be allowed to swim on that day. They had chosen a Monday, when the pool was closed to the public. When a few of us learned of this arrangement, we protested. We did not want to patronize a segregated facility. The party was canceled. This earned me the hostility of several faculty wives, who asked me why I picked on them. I, who love swimming, stopped going to the pool after that incident.

Meanwhile, the federal government had started to pass laws making it illegal for public facilities to bar Blacks. A woman from the local Black community volunteered to work with us. She went to the pool, accompanied by Steve and Esko, who served as witnesses as she was refused access to the facility. This gave us legal grounds to challenge the policy. What did the management do? It converted the pool into a private club. This meant that, legally, we had no recourse.

But we did not give up. To put pressure on the community, we decided to involve the churches. We prepared a petition asking that the pool be integrated. It was to be distributed to all the churches in town, and there were about 50. This job fell to Steve. He went from one church to another, and most ministers took the petition. The pool issue was now a big topic, but the town did not yield until the students got involved. They threatened to boycott local businesses

Groundbreaking for the Chevy Chase Community Center, along Fifth Avenue in Indiana, April 1971. From left: Daniel McDivitt, Frances Helman, Idus Jones, Dorothy Merritt, Norah Zink, Velma Matthews, Agnes Johnson, Lyman Connor, and Homer Isenberg.

if the pool was not integrated. At that point, the matter came before the local chamber of commerce, and the pool management had to yield.

While this was going on, we decided to continue our efforts to inform people and get them to change their minds. We decided to create a speakers’ bureau. That became my project. I approached my colleagues at the school. I explained what we were doing, and to their credit, everyone I approached was willing to share his or her expertise. The list of speakers grew each year. I publicized the speakers’ bureau in the local newspaper. While the speakers donated freely of their time and expertise, we asked that organizations that hired the speakers donate to the scholarship fund. In this way, the speakers’ bureau fed the scholarship fund. Requests for speakers came from many sources: youth groups, church groups, civic groups—the list was long.

The topics were varied, each professor drawing on his or her own experience and specialty, and they were interesting. Norah Zink, retired chair of the Geography Department, spoke about her work in Africa. A biology professor asked whether there was a biological basis for race. Several professors spoke about the treatment of Blacks in textbooks or in literature. My husband, Steve, talked about the postCivil War period of Reconstruction. The dean of the School of Natural Sciences and Mathematics, who was Black, addressed class differences within the Black community. One member of the local Black community, a prosperous, middle-aged family man with a successful business, shared how he was treated in town. That one was hard to listen to, as I empathized with his humiliation. Clarence Stephenson, a member of the Unitarian Fellowship from Marion Center, spoke about the early Black history of Indiana County. Eventually the topics broadened. For instance, Reverend William Richard Jr., who was blind, spoke about living with handicaps.

Housing was another issue, as discrimination was not limited to Blacks. One professor, Don-Chean Chu, wanted to buy a house in Shadowood, a pleasant housing development outside town. But he was Chinese. Someone took the initiative of circulating a petition to keep the Chus out. When this petition reached our friends the Trubitts, who lived in Shadowood— Allen Trubitt was a member of the Music Department—they tore it up and circulated a counter-petition to allow the Chus to buy a house in their neighborhood. In the end, they were able to buy the house.

While this was going on, we continued to think of ways to raise the educational level of our fellow citizens who were Black. We knew that academic setbacks start in the early grades, so we decided to create an after-school study center. Most Black children went to East Pike Elementary School, which was integrated. Working with the teachers at East Pike, we decided to provide academic support for any child, regardless of race, from grades 1 to 4. After the John F. Kennedy and Martin Luther King Jr. assassinations, a community center was built in Chevy Chase. It was named the Kennedy-King Center by the local residents, and our tutoring was held there after school. We prepared snacks consisting of juice and cookies before students and tutors settled down to work. We provided a tutor for each child. That required an extraordinary effort of scheduling—before computers and cell phones—as we felt that the children needed individual attention.

The tutors were faculty wives such as Betty MacIsaac, who was a specialized reading teacher; Joy Mahachek, a retired math professor; Barbara Brody, wife of an owner of the beautiful department store in Indiana; and many more, too numerous to mention. Eventually the School of Education became interested in our efforts, as the country was moving in the direction of integration; many students from the Elementary Education Department, along with a few honor students from the local high school, became tutors. In 1980, the School of Education also helped organize an integrated Halloween party. The idea was to give children of many backgrounds a chance to have fun together.

Change happened slowly. It took persistence, but it happened. We fought for integration, not separation. The goal was to level the playing field and to give everyone a better chance at the American dream, in which everyone can live in a free and prosperous society. I am glad we did what we did, because it was the right thing to do. I have faith that we will “live in a nation where [we] will not be judged by the color of [our] skin but by the content of [our] character,” to quote the famous words of Martin Luther King Jr. m

COURTESY OF EDITH CORD

Edith Cord in 2019

About the Author

Edith Mayer Cord taught foreign languages at Indiana State College and IUP from 1962 until 1979, when she left academia for the financial services industry. Certified as a financial planner, she retired in 2006 to write her first book, Becoming Edith: The Education of a Hidden Child (2008). That and its followup, Finding Edith: Surviving the Holocaust in Plain Sight (2019), detail her experiences growing up in Europe during World War II and evading religious persecution. During that period, she lost her father and brother in Auschwitz, and she was deprived of schooling for six years. In 1952, shortly before coming to the United States, she earned her licence ès lettres from the University of Toulouse. She and her late husband, Steven, who retired from the IUP History Department in 1987 after 25 years of service, had three children, and she is now a grandmother to seven. Living in Columbia, Maryland, she is a frequent speaker on her life experiences and on how to rise above difficult circumstances, transcend hatred, and protect freedom.