11 minute read

Where Scientists Meet

Kopchick Hall

Where Scientists Meet

By Mary Ann Slater

As a member of IUP’s Geoscience Department for the past 13 years, Katie Farnsworth knows all the research her students do in Weyandt Hall, the center of IUP sciences since 1966.

The students may be in a lab—extracting tiny fossils from aging rocks, modeling and measuring water f low using a stream table, or calibrating equipment for their field expeditions.

The catch is, according to Farnsworth and others in the John J. and Char Kopchick College of Natural Sciences and Mathematics, not enough other people are aware of what IUP science students are learning and accomplishing.

Some labs in Weyandt are dedicated to just one science, and students and faculty members have relatively few opportunities to share their research with peers in other disciplines. Collaborative spaces for discussing ideas and planning joint projects are limited. And, those outside the college are unlikely to see IUP’s budding scientists at work.

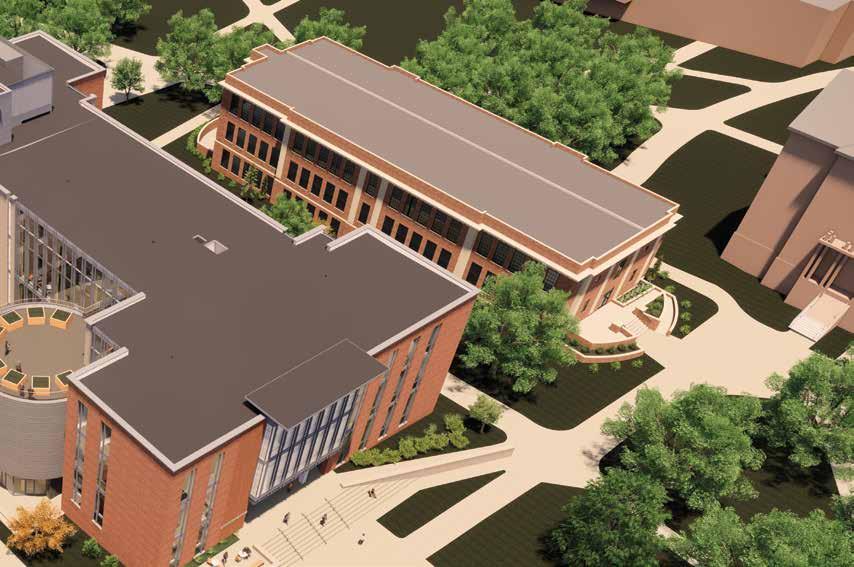

All of that is expected to change in coming years with construction of IUP’s new, $90-million science complex, Kopchick Hall. The building, along with the college it will house, is named for John Kopchick ’72, M’75 and Char Labay Kopchick ’73, who in April 2018 committed $23 million to IUP natural sciences and mathematics initiatives—the largest gift in school history. The building is set to open in 2023.

In September, university officials presided over the groundbreaking for the 142,536-square-foot building. That total includes 8,000 square feet of formal teaching space and 51,600 square feet of teaching laboratories and other spaces in which students will assist with faculty research. Other features include labs for anatomy and laser research, a planetarium, and a partial green roof for classes and research.

It’s the complex’s design that seems to excite Farnsworth and mathematics professor Rick Adkins the most. Both were part of a team of faculty members, staff members, and students who worked on the project with Pittsburgh architectural firm Perfido Weiskopf Wagstaff + Goettel. Their mission was to ensure that the building would be open and accessible to students and faculty members, that it would allow for more collaboration in scientific research, and that it would shine a spotlight on the achievements of IUP’s science students. “We wanted it to showcase the science that happens at IUP—to students, to other faculty around campus, and to members of the public, as they come to or pass through our building,”

Adkins shepherded the design process, acting as liaison between faculty and architect.

“The faculty were very committed to putting science on display and to furthering interactive student research within the building,” he said.

This participatory learning and collaborative spirit are key elements in science education today, Adkins said. Students majoring in chemistry need to be proficient in that subject, but today they also need to know how a biologist or environmental scientist looks at the world.

Deanne Snavely, dean of Kopchick College, reinforced that point, saying the building’s design dovetails with the trends of working in teams and on interdisciplinary projects.

“The big problems facing humans today are very interdisciplinary,” Snavely said. “You might have an engineer, a biologist, and a chemist, all working on a project together.

Kopchick Hall

Deanne Snavely

They need to be able to communicate and understand each other enough to see how to work together effectively.”

Snavely detailed several ways Kopchick Hall will encourage interdisciplinary cooperation.

One is the new building’s multi-user instrumentation laboratories. These labs serve students in different classes, even in different majors, because they allow for proper storage of specialized instruments that the student researchers can share. For example, some biology, chemistry, and physics classes may all use a spectrometer, an instrument that uses light to study the properties of materials.

Specialized scientific equipment can be expensive, sometimes costing $100,000 or more. Sharing equipment in these labs can help IUP control costs by avoiding duplication, and that savings may go toward the purchase of other equipment.

Another benefit is that students will be exposed to and more apt to use a wider variety of scientific instruments. “That is another very important aspect of the future of science—that there will be more and more instrumentation,” Snavely said. “Our students need to learn how to use these instruments and what to do with them. These multi-user instrumentation laboratories will make that possible.”

Snavely believes sharing equipment will promote better communication among students and faculty members, as well.

“When students and faculty go into this lab, they’ll talk to each other. They’ll say, ‘What are you doing?’” Snavely said. “People will learn more science, and they will interact with each other more through these laboratories.”

More collaborative experiences will also reduce barriers for students heading into careers or graduate programs, Farnsworth said. “When they get to locations where everyone is working together, where everyone is sharing equipment, they won’t have to learn those skills.”

Other design features in Kopchick Hall will help bring the work of IUP science students front and center. For instance, many labs will be visible through large windows. Adkins described how students will be able to navigate the building’s corridors and, as an example, peek into the environmental engineering lab to watch their peers work with a f lume, a specially engineered structure for studying wave motion and water f low.

Or, he said, they may pass the imaging laboratory and see students using the scanning electron microscope, which allows them to magnify tiny objects at very high resolutions and view them on computer monitors. These images will also be projected on large screens mounted in the hallways, so visitors to Kopchick Hall will see science on display.

Window-fronted labs will also border the Oak Grove, so visitors and students passing by can peer inside and see active learning.

Within the building, this glimpse into the work of others could spur future research collaborations. From the outside, it could change the way non-science majors view the world, Snavely said.

“So many people are sort of afraid of science,” she said. “They don’t know enough about it, and they want to stay away from science.”

Her hope is that seeing their peers at work in a biology or chemistry lab may pique their interest and cause them to try a science course.

The new science building also will have rooms that integrate lab and classroom spaces, which will help freshmen and sophomores especially to connect classroom learning and laboratory research.

“We definitely have a goal of engaging students early in their college experience in research activities, so they can be contributors to that laboratory work,” Adkins said. Those opportunities will make it easier for them to advance as upperclassmen.

Laboratories aren’t the only spaces designed with collaboration and communication in mind. Design committee members—largely at the request of students—also pushed for more informal areas for students and faculty members to meet and talk.

David Laughead, a December political science graduate from Ridley, was a biology student and the Student Government Association’s Kopchick College senator when he served on the building’s design committee.

The committee’s members were “very student led,” Laughead said. “Dean Snavely and Dr. Adkins worked with me to create a subcommittee to hear student concerns and what they wanted in the building.”

Chief among those requests, he said, was to make sure Kopchick Hall had adequate spaces for collaboration. In Weyandt, those areas were so few that science students often went to other buildings to work together.

The construction site in January, captured by a camera mounted on Wilson Hall. For a live view, go to IUP.edu/natsciandmath/kopchick-hall. Kopchick Hall will have alcoves in which students can study individually or work together, for example, on a PowerPoint presentation, syncing their laptops to an overhead monitor to visualize and share their ideas. They’ll also have access to common rooms adjacent to the labs.

“We wanted people to be able to walk out of the laboratories and find a place where they could sit and talk to each other,” Adkins said.

The complex will include rooms for tutoring and for students and faculty members to reserve for group projects. During vacant times, these rooms will offer space for students to study together.

Laughead is pleased with these features. “The new science building will have a lot more collaborative space,” he said.

While Kopchick Hall planners were cognizant of the needs of today’s science students, they were also aware that needs will change for future generations, Snavely said. The life cycle of an academic science building is about 50 years (Weyandt Hall is almost 55). IUP’s new facility will have to adapt to trends in science over a similar period.

“This building will be very f lexible,” Snavely said. “For example, the research labs don’t really have walls between them.”

Some labs will be divided into sections by lab benches—worktables that provide a surface to conduct procedures and space to store necessary equipment. Because the benches are mobile, lab space can be configured according to changing needs.

“As scientific disciplines change and as IUP’s focus on the sciences changes, you can expand this area or contract that area,” Farnsworth said. “You can reinvent the space for different initiatives.”

Snavely expects that interdisciplinary learning and collaboration in the sciences will only increase in years to come. She and her colleagues think the Kopchick College of Natural Sciences and Mathematics is ready for this future.

“You are not in a silo,” Farnsworth said. “You don’t do everything by yourself, especially in science these days. I want students to sit together and work, whether they are in class or out of class. That’s the future.”

For Kopchick College and its students, that future is looking bright.

Financially Speaking

Facing financial challenges, IUP announced in October an academic restructuring that would reduce its number of programs and employees (see page 5). Some have asked if funds earmarked for construction of Kopchick Hall could be used instead to save IUP jobs and programs.

In addition, Carl S. Weyandt Hall has served the IUP science community since 1966, and many of its mechanical, electrical, energy conservation, and safety systems have surpassed their life cycles. A feasibility study showed that bringing Weyandt to modern standards would be more expensive than building anew. The answer is no. The Pennsylvania Department of General Services, and not IUP, pays for construction of academic buildings, like Kopchick Hall. Of the building’s $90-million cost, IUP was required to raise $9.7 million, which came from private donors. Those funds have since become the property of the Department of General Services and have been used toward the building’s design and construction.

Rendering of the lower atrium

KEITH BOYER

Kopchick Hall’s west façade, facing the Oak Grove

Behind the Names

IUP’s new science building and the college it will house are named for John Kopchick ’72, M’75 and Char Labay Kopchick ’73, who in 2018 committed to the largest gift in IUP history.

John is a professor of molecular biology and the Goll-Ohio Eminent Scholar at Ohio University; Char is the assistant dean of students there. John also developed a compound that became the basis of the drug Somavert, used to treat a growth hormone disorder.

BRIAN HENRY

In addition to the Kopchicks, other alumni who have contributed to IUP science and mathematics initiatives are being honored with named spaces:

• Cejka Planetarium, named for Tim

Cejka ’73 and Debra Phillips Cejka ’73, whose gift fulfilled the Pennsylvania

Department of General Services requirement to begin the building’s construction. Members of the National

Campaign Cabinet for IUP’s Imagine

Unlimited campaign, the Cejkas chaired the campaign component focused on science and math. An IUP trustee, Tim retired as president of Exxonmobil

Exploration Company and vice president of Exxonmobil Corporation.

• Madia Department of Chemistry, named for Bill Madia ’69, M’71 and

Audrey DeLaquil Madia ’70, who, in addition to making a transformative gift, chaired the National Campaign Cabinet of IUP’s Imagine Unlimited campaign.

Bill retired after more than a decade as

Stanford University’s vice president for the SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory and after 33 years at Battelle. An interior designer, Audrey is the founder of Classic

Homes. • Anderson Rotunda, named in honor of

Bonnie Harbison Anderson ’80 and her husband, Steve, and in memory of her parents, Edward and Donna Harbison.

Cofounder and chief executive officer of Veracyte, a molecular diagnostics company, Bonnie served on the National

Campaign Cabinet of IUP’s Imagine

Unlimited campaign.

• Admiral’s Study, a tutoring room named in honor of retired Rear Admiral

CJ Jaynes ’79, M’82. A member of the

US Navy for 33 years, she was the first woman ever to achieve Aviation

Maintenance f lag rank. See more about her on page 33. m

Char and John Kopchick during the September groundbreaking