Dazed Starling Unbound

Founded in 2021, The Dazed Starling: Unbound is the online literary journal of the Department of Modern Languages & Literature at California Baptist University.

Address correspondence to: Dr. Erika J. Travis, Managing Editor The Dazed Starling CBU, Modern Languages & Literature 8432 Magnolia Avenue Riverside, CA 92504 (etravis@calbaptist.edu)

The Department of Modern Languages & Literature offers a Master of Arts degree in English, Bachelor of Arts degrees and minors in English and Spanish, and a Bachelor of Fine Arts degree and minor in creative writing. To learn more about the programs and professors in the Department of Modern Languages & Literature, explore www.calbaptist.edu.

The Managing Editor would like to thank Dr. Chuck Sands, Provost of CBU; Dr. Lisa Hernández, Dean of the College of Arts & Sciences; Dr. James Lu, Chair of the Department of Modern Languages & Literature; Rosemary Welsh, Department Secretary; and all of those who offered their encouragement, guidance, and friendship during this publication process. The Dazed Starling is currently published with funds generously provided by CBU’s Department of Modern Languages & Literature.

©April 2021 Respective Authors

Dazed Starling Unbound

DS: Unbound 2021

Letter from the Editors

Dear Readers,

Thank you for joining us on our first launch of the Dazed Starling: Unbound. In years past, editors on the regular Starling Team expressed a desire for a diversified journal that explored alternate art forms from photoshop and lineart, to watercolor and acrylics. An online edition of the journal was a great way to do that, and those on the Unbound team utilized the sharp graphics of online media to explore colors and aesthetics to match the work.

To our writers and artists, thank you for contributing to this effort. It’s been a pioneering adventure but we think that the results paid off. We’re so pleased you were willing to share your artistic work with us, and we hope you enjoy!

To our readers, this is a new venture but we hope that with every year in the future, new themes and avenues can be explored on the Unbound with your support. Thank you for your readership and as you read we want you to experience people’s different interpretations of this year ’ s theme: “Unbound.”

Sincerely,

The Dazed Starling: Unbound Editorial Team

Elijah Tronti, Elisheva Keener, Faith Wicks, Gabrielle VanSant

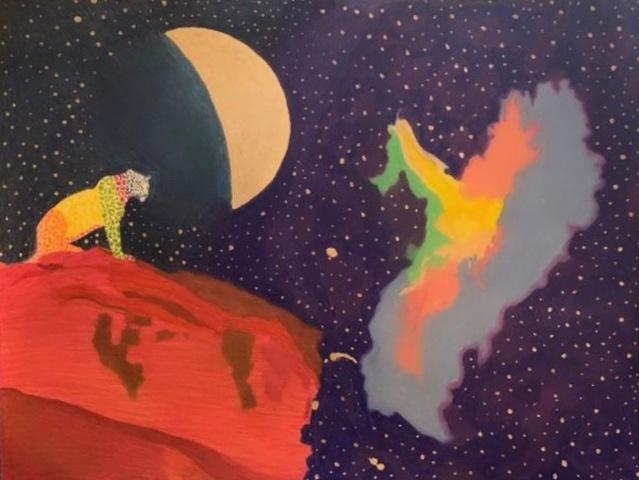

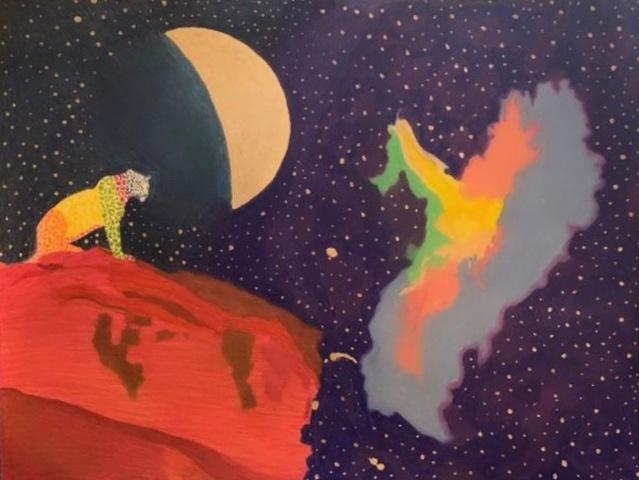

by Elijah Tronti

Language of Breath by Brandon Daily

When you call, I hear your breath-voice on the other end of the line, strong and heavy with air. Just breath, though there are words contained within the breath. I know it. Those nights, I hear them.

I can hear them still.

“Hello,” I say, the word like a question, like I’m not sure who might be calling at one or two in the morning. Still, I know it’s you. Every time, I know, and there’s a girlish giddiness that builds up within my stomach. Acidic, lightweight. There. And so, each night I wait by the phone, hoping for your call.

Why did you begin, this strange breath-voiced call? Wrong number? Or was I chosen?

Did you choose me? Perhaps you found my number written in faded ink on some discarded slip of paper? Or maybe you simply chose seven random digits and dialed. Either way, there is destiny to it all I know there is.

I’ve listened to your breath-voice enough over the past year to understand your language. I’ve become fluent, a scholar of those raspy sounds. The beauty is in the subtleties. The way your breath catches, even if for the shortest of milliseconds that lets you form your words. In this way, we converse . . .

Me asking questions—basic at first: Who are you?

BREATHHHS

Where do you live?

BREATHHHS

What’s wrong with your voice? You answering simplistic:

BREATHHS

Though strange and not English, not even a true language, I knew then what you said. Nothing,you were answering. Nothing is wrong with my voice. Nothing at all.

But now, my questions are more intimate. We are more intimate with one another. I close my eyes and my thoughts wander. I want to know your face, to look into your eyes. The darkness there, the light. I want to place my ear beside your mouth and listen to your breath-voice directly, hear your breath-whisper of love.

What’s your favorite memory? I asked you tonight.

In the rasp of breath, you answered: When I danced with my mother in the kitchen. It was summer and there was a blackout in the city and the room was lit by only a single candle and we danced in the kitchen barefoot to a tune my mother hummed. And I closed my eyes and lay my head against her chest.I was happy then. I say those last words aloud at the same time you breathe them into the receiver. It is as if, in speech, we ’ ve become the same, you and I, like looking at a stranger’s face and seeing a mirrored reflection of yourself.

Only recently I’ve realized that I’m dreaming in your language. Though, in many ways, I feel as if we all speak your language. As if it is the language of solitude and loneliness. The language of breath while we sit alone, separated from the rest of the world. And so maybe you aren’t really speaking foreign words or sounds. Maybe you ’ re right when you say there’s nothing wrong with your voice. Maybe it is my voice and yours and everyone else’s.

by Natalie Codding

Why Faeries Bite

by Sandra Rose Hughes

I understand why faeries bite. When you happen to be a creature of light, men want to catch you.

Men want to trap you in a jar, or tie a ribbon round your wrist, as if somehow your light and happiness will rub off on them. But faeries don't belong to anyone but themselves.

You cannot trap a faerie and imagine that they will bless you. They will bite you trying to escape, they will fight you, shattering their jars, or they will die just to spite you.

But the funny thing is, you shouldn't have to trap a faerie. They live to give light, after all. And if people don't see their brightness, no one will.

So sit quietly in the forest and wait. And if you're a gentleman, and you don't paw at them, they might just land on your shoulder and choose to share their light with you.

by Gabrielle VanSant

Knight in Dark Blue Armor

by Sandra Rose Hughes

It was the Yule of 2002. I arrived late, flustered, my breath constrainedYou were my blind date, Merely a smiling face in a photographI was barely ready to meet you at the table where you waited. Your warm brown eyes met my gaze, And you, in a dark-blue blazer and tie, Rose to greet me, to pull out my chair. You smiled a smile that said, “I’m here to take care of you, ” And I found that I could breathe again.

The room, and our table, was full of people, Lovely young women, jocular men- all laughing, talking, mingling. But you were my escort, focused only on me. “Do you need anything? We asked the kitchen to save you a plate. Here is the corsage I brought you. I tried to match it to your dress. Jennifer told me the color.”

We talked about the hospital where you still work And, when I babbled on about Dante and Faust, Virgil, and Mephistopheles, You nodded with understanding in your warm brown eyes. When I threw my fork across the table because I was telling a story too excitedly with my hands, you retrieved it for me.

You nodded with understanding in your warm brown eyes. When I threw my fork across the table because I was telling a story too excitedly with my hands, you retrieved it for me.

Later, when we rode back in my little white Dodge under a black sky, You noticed how empty my gas tank was. You convinced the gas station owners to open, Though they had just closed, You gave cash to the homeless men shuffling around the pumps, And you paid for, and pumped my gas for me.

I sat there in my car, watching you under the glow of the gas-pump lighting,

Like a princess who’d found a knight in dark-blue armor. I did not know if you liked me, Or if you were just as much a gentleman to all your dates. But something in my heart whispered, “I can breathe around him.”

Now, in 2021, with our fourth child on the way, In the house you built for me, In the life we ’ ve lived together for 16 years of marriage, Sometimes my breath is constrained by the duties, cares, responsibilities, of our life, But I still breathe easier when you walk in the door, And when you smile the smile that says, “I’m here to take care of you. ”

I still feel like a princess rescued by a knight in dark-blue armor.

by Natalie Codding

Remembrance by Jenna Wergedal

Although I will never forget you, the ocean is a never-ending cycle of thoughts.

Forgive me, if you are not forever in the waves.

Growth by Jenna Wergedal

Your petals may be plucked, But pruning gives you room

To grow again.

by Caitlyn Deutsche

by Nichole Stinson

Just a Note by Daphne

Kieling

Dear ,

I stopped counting the days, When the thought of seeing your face Was no longer what held me together.

Our future was not supposed to be written. Because the reality is, it was a fleeting narrative that kept me from truly living.

But now I am, so I guess the pain was worth it.

I still hurt, you know. A scrape of shame here and a gash of rejection there.

But it’s mostly my pride. How I thought after all this time that there was an upspoken agreement that the shoestrings of our souls were tied.

But I was wrong--and humility is a new look for me. That was something you wore so well.

I guess I’m writing this because I’m sorry I tried to make you fit inside my ‘Perfection’ box. The realness of you got clouded by the ‘Potential’ pedestal elevated in my thoughts.

Also, I just wanted to let you know that I’m the most free I’ve been in really long time.

Because you didn’t love me back, you allowed me to start calling my life and future ‘just mine’.

I know I have a lot more emotions and feelings to process-they may be different each passing day. I’m still confused if you did care for me or not--but regardless this is just a note to say, That by the abundant grace of God--I’m doing more than ok.

Sincerely, Me

Counting Days by Trevor Vals

It’s day one being stranded on this island after my plane crashed. I have plenty of supplies from my emergency packs to last me a few days, maybe weeks.

I sent a distress signal out before I crashed so someone should find me soon.

It’s day three. The island is beautiful. I never thought something like this could happen to me. God saved me.

It’s day eight and I’m running out of supplies. I was able to find a water source but got sick as soon as I drank it.

There’s been no planes or boats spotted and I’m not sure what to do when I run out.

I’m not sure how long I’ve been out here, but I’ve been out of food for three days.

I started eating some berries I found, and the island water is finally sitting with me.

The island is providing for me now.

by Elijah Tronti

by Natalie Codding

Bury the Bullets

by M. Faulkner

The yellow bulldozer plowed through the earth.Reddish clay folded over and upon itself like ocean waves. Disrupted worlds of plant and insect life rose and roiled to the surface. The machine pushed, the earth churned, until unseen, unnoticed, a thin box rolled up and took its turn on the crest of the giant earthen wave. For a moment it held its position, the rattle of its contents impossible to be heard above the din. Suddenly, it succumbed to the pressure, and the top flap broke forth spilling .38 caliber cartridges. They went unobserved. The sole evidence of its presence was a glint which sparked in the eye of a nearby worker who rubbed away the offending glare.

Men scurried around the construction site, each set to a task the foreman had given them that morning. Some held shovels, some moved gravel and mixed concrete, some operated heavy machinery, but all contributed to the clamor of shouts, grunts, blaring rap music, and the background sounds of the nearby ocean. A wrecking ball swung high in the air then plunged through the dilapidated, condemned beach house which stood on what would soon be a prime condominium spot. And the bulldozer continued to plow, plow the earth as though it knew what it was burying.A large, flowering bush was jerked up, roots and all. Other objects followed, but quicker than a blink, they were swallowed, dispersed, and rolled over by massive tire treads once again to be hidden beneath the surface.

A willow tree’s long ethereal strands waved in the wind and dark. Up they rose only to convulse then fall again a shaking sweep, then a plummet. Lightening streaked the sky, followed by an explosion of thunder, but the expected torrent of rain didn’t come. Occasionally a heavy pellet escaped the night clouds. Debris flashed in the chaos, clattering and skipping on the tin-roofed porch of the small, battered house. Inside, there was a clanking of jarred glass. The small shutters flew open, but it was not caused by an invading gust from the raging windstorm outside. A man stared into the dark, not feeling the cold blasts to his face, then he stumbled back to his seat and slammed an object onto the green speckled tabletop. The murky longnecked bottle on the kitchen table rocked unsteadily against the empty bottles beside it. One, two, three... and the clear one was just about empty also. It had taken all that dark afternoon to drain them—one deliberate drop at a time.

The man sat staring--a living statue. Who knew what he was thinking? Minutes passed. Then, as another frigid gust shrilly whined past the kitchen window, his thick finger began to move. Flicking the neck of the bottle, it kept time with each lazy, drunken bar he sang.

“Oh little hum drum baby of a boat, where, oh, where can this little tug float?”

The calm nursery rhyme didn’t match his actions, for suddenly his long arm raised high above his head then came down like the lightening outside. There was a smash of glass and the gravelly crunch of it underfoot. Stutters and noises of staggers. Curses. Kicks. More crashing. Grumbles as the broom closet was shut, the shutters shut, the storm muffled, the scraping of the vinyl chair... Then came the familiar toneless hum.

Renaldo watched what he could through the distant rectangle of the lighted kitchen doorway—his vision impaired from his vantage point above the rickety stairs. The young man watched but mostly listened to the drama below him

Only his father’s back and the edge of the kitchen table could be seen, but Renaldo could clearly hear the humming which droned on and on and on. The wind outside slowed. The rain finally came, and with it the sobs. His father leaned heavily on the broom handle he held in his hand, then he tipped off his chair and crumpled in the puddle of broken glass. Oblivious to the shards, he rocked back and forth in the fetal position.

The weeping eventually stopped but the humming resumed, humming, humming, humming like a drone bee. Mindless, toneless humming.

Renaldo hovered at the top of the stairs wishing for his mother. She had left, but who could blame her? If he remembered correctly, she was a small, frail woman, and who could stay in such a house?... Renaldo gritted his teeth...or was she a frail woman? Unlike himself, she hadn’t stayed in such a house.

Sitting on the landing, Renaldo watched the everrecurring nightmare of his life and was suddenly struck with a longing so strong it became hard to swallow a mother, siblings, a close friend, a warm body...

A heavy fragment, pushed by a gust of wind, smacked against the only window in the house--an elongated, vertical piece of patterned glass parallel with the front door. It was nearly the only unbroken thing left in the house.

Renaldo stood and ventured from his perch above the stairs, approaching the kitchen cautiously. The humming had

stopped. He entered the lighted room and warily bent over his father’s body, watching his chest rise up and down in erratic movements. Renaldo snorted. Curled up on the floor like a baby...and this man had been a soldier. Renaldo leaned over him, then squatted close enough to smell his fetid breath. He gingerly touched the broom handle that was clutched in the large, hairy hands. A jerk then a struggle followed, and incoherent words spilled forth. Renaldo scooped his thickset arm under his father’s as they struggled to rise. Renaldo towered a good six inches above him. Broad shoulders, a thickened muscled torso made strong by regular football practice.

Renaldo’s father looked feeble next to his almost adult son, but anger gave him bursts of power. He shoved Renaldo away. Then like a tsunami wave gaining momentum, he shoved him again, harder. Pain must have registered in the man ’ s mind, for he touched his back, and the scarlet he saw when he withdrew his hand enraged him like a shark in bloody water. Renaldo was not quick enough to escape the broom handle when it arced, but it was an alcohol-impaired swing, probably meant for his head, yet only clipping his wrist.

There it was again, the intense, focused glare that Renaldo never understood. His father was staggering drunk, but his eyes belied the innocence of his actions. A drunken swipe here and there that sometimes connected with a force full of misstep, but it was the eyes, the eyes that told of a concentrated passion. He wondered what it would be like to dive into such hatred and emerge with a pearl of an answer.

Was it serendipitous that the next morning just as Renaldo’s swollen wrist was throbbing at its fullest that he walked in upon his father fumbling with a bottle in one hand, a gun in another?

Renaldo shook and slowly stepped back.

by Bethany Steele

His father laughed as he waved the weapon. “Don’t leave, Renaldo. I’m not after you. ”

Renaldo looked him in the eye and saw that it was so. The cold hatred was not directed at him this time.

His father took a swig from the bottle with a palsied hand. A drop dribbled down his bristled chin. “Your old man is leaving. Stay and watch.”

His father’s hesitancy allowed Renaldo to utilize his football skills by tackling him and wresting the gun from his hand. On his way out the room, he swiped the case of cartridges from the dresser.

Renaldo disappeared for several hours until the early evening just before sunset. He circled the perimeter of the clapboard house and sat next to the sole bush on the property, a bush that had not been purposely planted, but persisted in flourishing just the same.

With a flat stone, he began digging in the softened ground. Ten minutes later he unearthed a trove of what most people would think was trash. A tie, its colors too muddied to recognize his father had worn it to his last failed job interview. A thick Swiss army knife. Images of a drunken fight in the parking lot, a man ’ s leg mutilated. A main artery cut so it was reported the next day in the media. A little bell belonging to a child’s bicycle. What a drawn-out court case that had been. Now the car would forever stay put rusting in the salt mist that made its way up the cliffs. There were two small caps, one belonging to a bottle of ammonia, the other to a jug of bleach reminders of the time he had found his father passed out in the tub. A dog’s collar Renaldo had seen the animal trot out of the yard and gleefully watched him go. Renaldo unearthed the last object a simple steak knife. He wiped the mud from the dulled blade. Palsied hands couldn’t

stop it from turning it into a deadly spear, but Renaldo had corroborated with his father’s story at the hospital, and they both had been allowed to return home, even if it was under a cloud of suspicion.

And now the box of cartridges. The gun itself had kissed the night ocean off the edge of the pier, but the box of ammunition was enough... Renaldo found himself grinning as he counted each one. He imagined with a strange, perverse pleasure all the holes that could have pierced his father’s flesh, and a deep cynical chuckle escaped his lips.

Darkness had descended, Renaldo re-covered his unlikely treasures and ventured back into his hellhole of a home. He frowned but took sick comfort in the fact that someone else suffered as much as he did.

The next morning, because his mind was troubled, Renaldo did what he had done before. After seeing his father passed out on the dirty sofa, he ventured into the kitchen and filled his pockets with snacks. That’s when he saw the new bottle in the cupboard, already opened. He poured just enough of his father’s vodka down the drain and replaced the missing liquid with water from the tap. Then he headed out. This time it was to the town of Gra---, a town not his own.

Anonymity was found in Gra--- as well as in its whitewashed church with its glorious statues of Peter and Paul which beckoned him to enter. He ascended the short, flat steps and through the middle of the symbolic triune doors. He made his way to the confessional booth and stepped inside.

Renaldo hated that his mind was burdened once again. He desperately needed to relieve his conscience. “Bless me, father, for I have sinned...”

They were only words, but he had found that confession was comforting and penance temporarily freed him from the weight of his spirit. But, as times before, he abruptly ended the ritual. Like a pelican about to take flight, Renaldo picked up speed. The priest, hearing his movement, burst from behind the screen with a cellphone in his hand. In four months Renaldo would be eighteen and would no longer feel the need to run, but until that time any detailed confession brought about the fear of the CPS.

“Wait!” the priest called. Renaldo momentarily slowed.

“If you let him, he will kill you!”

An elderly woman fingering her rosary gasped from a wooden pew. She squinched her eyes closed and leaned farther away from the aisle as Renaldo raced out.

The sky was windswept and clean, unlike his soul; the ocean breeze balmy. Gulls occasionally cawed above him, and an automobile whipped by on the highway that edged the ocean cliffs. After the long bus ride, it was an even longer walk home, but Renaldo had much to think about as he ate one of the four granola bars that he had shoved in his sweatshirt pocket that morning. Even after going to confession Renaldo did not feel the purity, the absolution that he had come to crave, and that annoyed him. Perhaps it was because he had not finished the ritual. That priest had said troubling things, things which left him disquieted and burdened even more, but Renaldo pushed it from his mind.

A quarter-mile inland, Renaldo approached the shack. The weeping willow was still, but a beer bottle mobile clinked lightly over the porch. Renaldo rubbed his forehead in consternation, then stopped. The tall, thin window by the door was smashed. Renaldo stood still for a moment, then for reasons he did not even understand himself, he bypassed the door and entered through the jagged pane. Natural light flooded in from all the opened shutters. Wooden floors creaked. He thought he heard laughter and turned his head toward the kitchen. It was empty. A few cabinet doors hung open. The grimy cotton curtain flapped in a breeze that should have been refreshing. A knife on the table, an empty soup can rolling on the floor on its side which seemed to have tipped from the overflowing trash.

Renaldo’s body tensed like it hadn’t since he was twelve years old. Was that laughter? He slowly turned, his eye catching an object on the mantle across the hall. Cheap paneling, a fireplace never utilized. There wasn’t much in the room, just a dirty sofa and another chair just as filthy. But something new caught his eye.

Renaldo slowly walked into the room wondering where the picture frame had come from. His hand retrieved the photo, and his finger traced the outline of a woman he knew he must know. A ripe stomach, and a boy sat on what remained of her lap. The creak above the stairs only slightly penetrated his daze of her beauty. With each thud of a step from the stairs beyond, his mind flooded with a new thought that penetrated this sacred bubble. The fetus: lost camaraderie. Where was he now? The woman: lost protection, lost touch, lost tenderness, lost joy. Why had she left him here? Renaldo’s breathing increased with each

by Natalie Codding

unrealized longing that swept over him. Roiling and broiling anger bubbled up from inside. The injustice of it all! With his free hand he grasped the edge of the mantle, his knuckles turning white with rage.

The footsteps halted just outside the room at the doorway.

Renaldo shook. “I could kill you, ” he growled, low, menacing. Without turning he looked up and into the cheap, frameless mirror that hung over the fireplace and peered at the image behind him. “I should kill you for all you ’ ve taken from me. ”

A haggard, hollow man stared back, his eyes, for once, empty and devoid of any emotion. Renaldo couldn’t stand to look at him anymore. As he turned away, he caught the reflection of his own eyes and was shocked to see them filled with the same concentrated hatred that had so often stared at him.

The picture frame he held in his hand fell to the ground, cracking. Renaldo snatched the mirror from the wall and threw it. There was a release. Now there truly was no unbroken thing left in the house. Renaldo found himself sobbing as his father turned and disappeared. Time stood still, so it seemed, but powerful thuds of a falling body sounded only moments later. Renaldo whipped around; the sobs sucked suddenly from his body in shock.

At the foot of the stairs lay the twitching form of his father. In a daze, Renaldo approached. The neck was bent at a wicked angle. He stared for a long time until the twitching stopped. Renaldo squatted and leaned over him. The acrid smell of alcohol was still strong. He went into mechanical mode and reached his long arms under his father’s and hoisted the dead weight until his father’s feet dragged, tip-

toed, on the wood floor. This time there was no struggle. How long he stood with the dead weight he did not know, but he made his way out the front door and dropped the body where it seemed fitting, by the bush that had sprouted when no one cared for it, the bush that kept watch over the cemetery of objects that he had buried over the years. Renaldo’s fingernails scraped into the semi-soft earth, uprooting the shallow grave of the tie, the caps, the knives, the bullets, the collar, the bell. He went back into the house and retrieved the frame of the woman and boy.

Renaldo put the objects back into the ground, patted the dirt over them, then stood. He went inside and found his father’s cell phone, but the battery was dead. So he went back outside and began walking. In a few minutes he would reach the trailer of his nearest neighbor where he could use their phone and call whoever it was one called when someone dies. Renaldo’s heart began to pound, but the horror that kept washing over his body was not at the death he had witnessed or the sudden loss of his only known living relative. The horror was that of the emotion he had caught in his own eyes. What he had so despised in his father’s eyes had been present in his own. He recalled his encounter with the priest that morning.

“Bless me, father, for I have sinned.”

Then his entire life story had poured forth until the priest, the first who had ever discerned his true sin, had asked what no other priest had asked before. It had always been, “You have not sinned, child. It is your father. Let me make a call to help you... ”

“It is commendable to try to keep your father from killing himself, but he will only try again. No amount of burying will change that. It is not safe for you. Let me give you a number to call...”

“But my guilt is heavy,” he would say.

“You are a victim. You are not seeing the situation clearly. You are not guilty of anything ... ”

So it had gone in such matters before, but this time this priest had peered into his soul. “There is much you could have done, child. Courage to report him. A man ’ s death has gone unpunished. How do you know your father has not killed again?”

Renaldo did not answer. After the fight, his father’s paranoia had increased.

“And why did you dilute the alcohol? If you were so concerned, you should have dumped it unabashedly down the drain.”

Again, Renaldo did not respond, but he knew the answer: a clearer mind would not be numb to pain.

The priest continued. “The tie, the bell, the dog’s collar you kept them all. You took great joy in his failures and agony, didn’t you? The bleach, the ammonia you opened a window to cleanse the room, but did you give what truly could have cleansed his soul? Help, hope, forgiveness, the gospel of the Heavenly Son? The knife, the bullets... why did you bury them?”

Renaldo could not face the truth, and as Eve had offered excuses and as Cain had lied, Renaldo did the same, “I buried them to save his life.” Then with more emphasis, “To save him from killing himself!” How noble it sounded.

"Taking one ’ s life is most certainly a sin, my child, but were you really attempting to save him? After all, you did nothing else afterwards.” The priest gave a tut tut behind the screen. “Oh, my child,” he sighed. “You yourself came because of your burden. You said it as you entered, ‘Bless me, father, for I have sinned.’ The Spirit has convicted you of your heart’s motive, of your bitterness. My child, it is obvious that you weren’t trying to save your father’s life. You were trying to punish him with the wretchedness of it.”

Renaldo didn’t stay for the Act of Contrition. He couldn’t say the opening words with any sort of sincerity. He couldn’t say the closing words with determination. So for that moment at least he determined that he wouldn’t lie. Instead, he ran like Jonah.

The sun beat down upon Renaldo’s forehead causing a rivulet of sweat to drip. The priest’s parting words echoed through his mind. “If you allow him, he will kill you!” Yes, Renaldo knew it to be true. The wicked laughter he had shown when burying the bullets, the years of silence covering his father’s misdeeds, the gleam reflected in the mirror... All the times he had seen his father fail. He had relished them, relished in his father’s misery, hiding tangible objects of the memories like buried treasure, unearthing them to feed his own disdain and hatred.

A sea gull squawked overhead as his neighbor’s double wide trailer came into view. A new, shaky future awaited him, and Renaldo had a choice to make. Would he allow his father to kill his soul?

“Get rid of all bitterness, rage and anger, brawling and slander, along with every form of malice. Be kind and compassionate to one another, forgiving each other, just as in Christ God forgave you. ”

Ephesians 4:31-32

by Elijah Tronti

Boundless by Gabrielle VanSant

I pour my thoughts into the pool

The stagnant faces mirror back

Indulgent water, drowning me

My pleads move not, unraveled spool.

. Caressing me, it starts to move

There’s something stirring in the deep

The lion’s breath shattered the edge

Glistening water breaking through.

. It tumbles, pours, it dances down

Memories, tears, happiness too

Released into the open air

Excitement entertains no bounds.

. My waterfall stays pouring there

With His release, ones always free

And now my voice roars thun’drously

Reflection bright as solar flares.

by Bethany Steele

Free TW: Self Harm by Selah

Kelly

11 years old.

Childlike thoughts, of ending a lot. She’s too young to know what’s wrong.

12 years old. She finds something sharp. Not sure why it helps, but she sure does it a lot.

13 years old. Her home splits in two. Taken from the only place, that she ever knew.

14 years old. Crimson arms, and hospital socks. Started on little white pick-me-ups.

15 years old. The last time that she, used a metal edge, and had to wear long sleeves.

16 and 17.

A struggle to keep clean, but new coping mechanisms, taught her how healthy she could be.

18 years old. In front of her school, she shares her testimony, for a hundred or two.

Younger girls, going through the same. Help her realize God’s plan, for making her this way.

19 years old. To college she goes. She never thought, she’d be alive to see her grow.

20 years old. And five years clean. It’ll always be a struggle, but she’s finally free.

In the Land of Si Se Puede

by Amber Boetger

Si se puede my Grandmother heard. She saw the signs, Exposed to American dream.

Yet she had no access.

Familial separations, New land degradations, Societal expectations

Pulled her to a realm Without.

Si se puede they chanted.

Grandmother picked strawberries in weathered field

Sweating, Laboring, Anguishing

Over luxuries

Untouchable.

Si se puede. This is America!

Grandmother chose love;

Hunched over, slapped, bunched into ruthless arms

Worked by the addict.

Si se puede! Woman of freedom!

Grandmother chained.

No honor, no color, husband’s presentational “valor”

Cries of My God! My God! Por que me has desamparado!?

In the land of Si se puede

by Bethany Steele

by Elijah Tronti

Moroccan Scrapbook

by Gabrielle VanSant

He rubbed her knuckles with the gentlest motion as the two lovebirds strolled down the sandy beach. The colorful skirt hugged her hips, brushed her legs, and danced along her ankles as the wet grains stuck to her feet and the hem. It looked as though they had just met and yet been together for years and years, souls that were meant to be melded. That was what it was like when souls attached. Josef loved every little thing about her. Her silky hair, the fiery spirit that kept the whole house warm.

People are sometimes born with the spirit of a wanderer, a jinn spirit. Aleice had that kind of magical aura. It emanated from her, like the magic of the desert. The desert could roll over buildings, lives, memories, and hide it from human eyes for years and years. The desert shifts, its sloping dunes pour over themselves in a scape that never can decide on a still expression. Aliece flowed as freely, eyes crinkled in a smile. Josef knew he must be the luckiest man in the entire world.

There, on the sand, he grabbed her hand, laughing as they ran. The tide tried to catch them, licking at their heels, but it could not. It splashed up onto the shore, spraying them lightly. They fell together, laughing on the sand. Neither one was serious in the least, and why would they be? Music spilled from every street, noises of throngs of people buying and selling and creating and living erupted here, there, everywhere.

These were the kind of parents that Monique Haliot was born to, at the end of the war. She was born into the era of peace and growth, when the sheikh still submitted to the French. To a toddler, the world’s dazzling hues still colored over the blights of reality. In Casa Blanca it was a fine place to grow up, near the coast. Clothes would hang on lines in between the apartments above the streets, creating shadows of color on the ground. The bright lights reflecting off of jeweled necklaces gracing long necks, fake or not, would create beams of light she thought of as faeries that flickered along the walls. She would grasp at the fruit from the stands.

The quick discussion of her mother and the shop owner would usually end with some sweet dates in her hands, chubby and small. These were fresh, juicy and plump, the kind that melted in a mouth with one decadent bite after another. Moroccan dates were ambrosia to all the children. But as they do, children grow, and the toddler that used to stumble over every stone and cry turned into a ten-year old child, mischievous and lively. Her face was full of exuberance as she ran with her friends, ducking under the rugs. The large cloths, beaten by the housewives, filtered dust down onto the children’s heads as they darted. The dull thuds sounded like drumbeats, marching to an unknown tune. Her parents would take her to the synagogue on occasion. They would enter right on time, sit close to the back, talk to their friends, worship and then leave. It was a simple routine, one that worked like a charm. G-d was a beautiful, untouchable, holy thing. When people were good and followed the Torah, then they would go to heaven and

commune with Y-hw-h, but until then, they had to be as good as they could be. Considering that their family ate orange chicken and couscous with a milky coffee in the evening, however, it’s safe to say that Monique, Josef and Aleice were not the most devout. They took her to see artwork, festivals, and taught her to love dance. Dancing brought her higher than the clouds, her imagination soaring as high as her heels could kick. Her feet landed rhythmically as she spun from room to room in the house, the hot sun shining on the floor as her small feet leapt to touch the spots of light. She would spin, move her hips, twirl her arms, and create the illusion of a willow in the wind, a sort of dance that drove right to the heart. Then, when the heat of the day would wane, and the sun shone its last sleepy red rays onto the rooftops, her friends knocked on the window. She slipped on shoes, push up the sill, and jump lightly down into one of the alleys. Her two best friends, Anita and Giselle, would sprint beside her. They ran, laughing, chasing after a ball. The group stayed together, and people still flooded the streets. Lamps were lit, people milled about, and the kids had no sense of fear. Her spirit lit with passion and zest for life.

That didn’t change in the classroom either. Her hand stuck in the air for the umpteenth time, wiggling her fingers around so that they wouldn’t go numb. Geography, history, language, it didn’t matter what subject she sat through. Her mind sorted any difficult study with ease, and everyone knew that. But it was history and language that forced her out of her seat and to the board every single time. She loved it so much, she would have to

answer. She yawned, stretching and arching her back for good measure. A few people snickered. The teacher, tired of trying to look for someone else, held out the piece of chalk to her.

“Je presume que vous avez un response, mademoiselle?” I assume you have an answer, miss? Monique bit the inside of her cheek to keep from smiling as she wrote an answer. Her cursive was scrawled, but still, the evenness of her letters and the way that she kept them straight made all the other children squirm in their seats. No doubt, when Monique gave a speech for the school, their parents asked them how come she excelled and they couldn’t. And yet, one flash of her merry smile and all animosity flew out the window.

“Correcte.” The teacher seemed almost bored at this point, scarcely looking up from the text to confirm the answer. Monique skipped home from school that day. She wiggled out of her uniform, smiled broadly at her parents, and flopped down onto her bed to read. Reading was toobland a word for what Monique experienced with learning. It was an adventure, a journey. Everything had something new and exciting to offer, and she was more than eager to figure it all out. She pulled out her English textbook.

“L’anglais.” She murmured, opening it. Her childish voice could be heard from downstairs, calling out broken English phrases.

“Au moins elle est entusiastique,” her father shrugged and looked at her mother, who smiled back at him.

The days of childhood are simpler than most. Perhaps that’s why they go by so quickly. Ball in the streets, dancing, the beach- it was a small paradise. She started pointing at things and saying them in English for practice.

“Rubbish bin.” She pointed to the container in the kitchen, her tongue twisting to make foreign sounds.

“Bien sur, Cherie.” Her mother encouraged her, and the girl’s dark eyes lit up at the praise.

Their little paradise went undisturbed. If, of course, undisturbed meant that the neighbors knocked on the door, irritated with the loud laughter from the house, only to find Monique telling an outrageous story and staying to listen. There was something about her face, the way that it changed as she spoke, the way that she smiled. Her smile grew as she did. Her round face lost that childhood puff to it, and her eyes grew sharper, more understanding. Hips flared and lips reddened with intelligent responses.

That child was gone, and out came a vivacious sixteen-year-old with curly dark hair, an upturned nose, and the biggest, darkest eyes one could think of. The boys of the neighborhood loved to try and catch her if they could, asking her to go out dancing with them. Sometimes she would nod, and other times her loud laugh as she refused made them grin despite the rejection. She teased consistently, but it was her giving nature that balanced her. People flocked to her because the joy inside bubbled out of her and spilled everywhere she went. As a child, she would chase the sunshine. Now, as a young woman, she was the sunshine.

What once was climbing out of windows in order to kick a ball in the streets, was now climbing out in colorful skirts, hair neatly done, and a touch of rouge on her cheeks. The clubs were bright with their shining lights, where the young people inside were swinging around and around in a wild dance. It was a new dance, called swing, and as the adults clicked their tongues, the young men and women kicked their heels. The billowy skirts showed a scandalous amount of leg, but it made the wild steps that much easier. They would giggle and laugh while young men in their button-down shirts would hold out their hands with roguish grins. Of course, Monique would be swept off her feet away to the dance floor, her bright smile attracting even more suitors. It was a funny game to her, a moment of careless youth, as she made sure to keep her distance just enough. It would be too much to say that she was a tease, but that smile that broke her lips like the sun through the clouds was a tease, of a kind. Soft music poured out of speakers coming from dark, velveted corners with large chaises to lounge on. Figures moved, mysterious, like a trance, on the edge of the noise and light. Spicy and warm smells permeated every corner, and in the middle of it all, Monique twirled and laughed.

Stepping from one gent to another, the young girl ensnared the hearts of her partners. Her friends twirled with their own young men, caught up in the merriment. There was no way that she could make patrons jealous because as Monique laughed, the entire atmosphere lifted. The lights shone a little brighter and the young men smiled a little more roguishly than before. Normally

Monique would coyly evade the men ’ s touch, but when she tired of dancing, she let one or two guide her to a chaise by the dance floor. She lounged on the velvet, her skirts fanned around her like a painted ivory fan.

The songs ended, and the dancing filtered down to a few people still swaying to some slower numbers. Monique and her friends let the music carry them out of the doors into the star-studded night, enveloped by the coolness of the air in contrast to the hot, sticky humidity of the dance hall. The air no longer vibrated with noise, and the walk home was full of whispered secrets, as friends do in the early hours of the morning. Nighttime brings the silence enough to think, and they poured their thoughts and dreams into that stillness, giggling under their breaths. With the morning heat came the hustle, the bustle, and the rubbing of tired eyes and smeared makeup. The excitement that had flooded her veins was now replaced with quiet contentment from the night before. Fried eggs with olives lured her out of bed, and down the stairs to the warm kitchen, her mother giving her a knowing smile and her father looking chagrined. Monique kissed his cheek anyway, and his stoic expression softened as she turned to retrieve her breakfast. The sunlight moved as she sipped her morning coffee. Rays of light would slowly move from the counter to the floor, the brightness warming her up. The Saturday involved a trip to the temple, and as she sat in the row with her parents, she met the sheepish eyes of her friends who, like her, had laugh lines and dark circles on their faces. No one dared to breathe a word about it even during the morning greeting. The tabernacle

soon filled with the routine singing, and Monique had to look straight ahead. One glance to the right or left would send her into peals of unladylike laughter. So she studiously stared ahead, and after the painstaking service, she swept off of the pew and into the warm day. Her friends were to meet with her at the corner, as the families parted to start walking back to their homes.

She wiggled her ears a little and her friends snickered at her, she could hear them. It garnered her favorite suppressed laughs. The day after, it was the wide eyes and the pleading grin that got her mother to cave to her whims. After all, the Sabbath was over, and the lack of school and possibility of a new dress fueled her begs.

“The bazaars, Mama! I have studied for so long a l’école. Might I go with them to the market? They’re the best on Sunday!” It might have been how quiet she was in tabernacle, and how diligently she was working on her schoolwork, but the nod from her mother and the look from her father made her squeal an excited thank you, and a with flurry of skirts as she rushed off to join her group. Skidding to a halt on the warm pavement, the other girls laughed as she tucked in those flyaway hairs that tried to fall out of her neat hairstyle Her hair still curled at the base of her neck though, no matter now neat she made it.

Then, it was off to the market.

The bright sun hastened their steps through the streets, seeking relief under the stalls’ canopies.

Rich reds, deep blues and saffron yellow danced in front of their eyes. Loud vendors called out for silver jewelry, loudly proclaiming in French that it was the best in Morocco that one could buy. The girls simply had to try

some on, draping it about their necks and pretending to be rich wives of sheikhs before handing them back to the shop owner, who rolled his eyes a little and paid no more attention to them.

They purchased little Mont Blancs at a café on the corner, looking at the people milling about the dusty streets from their table. Patrons ducked under shop canopies, eyeing the sun and finding the best deals. Kids played with a football in the road. The friends’ tiny forks dipped into their sweet treats, and as they gossiped on, their corner of the world seemed complete. Perhaps it was the merriment of the afternoon or the infection of youth, but the girls were more content to wander among the cloths and rugs and purses and rough-cut stones than anything else. It was a moment that they would remember for the rest of their lives.

Each African sunrise, and blazing day, will end eventually. Just as sure as the sun, it moves, and so must the people beneath it. At least, that was the idea when Monique tugged at her school uniform collar, as her teacher handed her the application form for some American scholarship, a Fulbright. She was comfortable and happy in Morocco, to be sure. Something inside her, however, stirred a bit in excitement. A spirit of adventure was calling, and it would not be denied. Her perspective changed over the next few weeks.

Being one of the smartest girls in school, she knew it meant she’d need to work if she wanted to secure that kind of opportunity.

And so she did.

Attitude never changing, Monique’s drive simply got that much more intense. Her teachers loved her infectious laugh, made an example, dubbed her an ideal student. Her cheek would redden a bit every time a teacher made a praiseworthy comment. After all, being a teacher’s pet earned one snickers in the hall. Unless, of course, one was Monique. To those laughs she would only laugh louder, which made it impossible for anyone to hold a grudge against her for it.

She got accepted.

Everyone knew that she would.

But it didn’t stop the painful twist in her gut when her friends gave her encouraging smiles, tainted by sadness. Her hugs and promises of letters did little to quell that pain. It was bitter, just like Arabian coffee. Her mother still encouraged her so, but Monique overheard the worried tones in those hushed voices when they thought she was asleep. She would be thousands of miles away, for four years.

Tears dripped onto her pillow some nights when she thought. Whether it was because a British comedy was on for her to practice with in the living room, or she was lost in her own thoughts, they fell. Happiness and sadness flowed together in one emotional stream.

And yet, every morning, she would still get up. She went to school, and she studied harder than she ever had before. She could almost taste the greasy burgers, could almost hear the sweet croon of the Beach Boys live. There were so many new things, that it was impossible not to

begin to get excited about going. The sadness could not overwhelm her, not when she’d come so far to see the world.Her mother caught her in the kitchen humming, “I wish they all could be California girls...” softly to herself as she dug her nose deeper into her book. Her older sister rolled her eyes and continued to cut the chicken at the sink for dinner. The untouchable summer, where every month was warm (some warmer than others) would soon fade as she traveled into the cool fall and then cold winters. Monique had never seen much snow before, but she watched those American musicals on the box television and imagined so.

She could imagine the feeling of snowflakes landing on her nose, melting from her frosty breath. The sky would be filled with dancing white, tumbling and swirling to the bare ground. The winter cardinals would chirp into the stillness of the trees, now decorated with the finest white fur coats. It sounded so peaceful, so different. The fireside would be warm, with a book and some hot chocolate. It contrasted the hot Middle Eastern nights, burning their way into her memories, her past branding her like red hot iron. She touched the walls of the apartment, the kitchen counters, the stairs, the passages of her childhood. She would miss this. But she could not help to long to catch those little wintry flakes of change on her tongue. Her leg bounced in anxiousness as she adjusted herself on the uncomfortable airport seat. Her mother’s warm hand clasped hers on one side, her fathers on the other. “I’ll come back.” She said with as much assurance as she could muster.

“Don’t run off with du American, ma belle fille.” Her

father said with a little wink. Her mother pretended not to see it.

“I

won’t.”

Somehow the words fell flat in the noisy, echoey hall. The heat of the sun outside was already masked by the cold, dry air conditioner of the terminal. It felt so out of place on her suntanned skin.

She rose from the airport waiting seat as a voice came over the noise, telling people to begin the boarding process, and her mother peppered her with kisses, and her father hugged her, so tight a squeeze that her chest ached. Monique hoped she’d squeezed back harder. Clutching her backpack to herself, she stepped out the door and into the sun once again, walking up the stairs into the plane. She slunk down into her seat. The weeks of packing and stressing and the passport were over. Her room was suitable for guests to use. Her photographs were laid flat against each other, tucked into a yellow manila folder. Somehow something so flat could hold an entire world of emotion.

As the plane took off, she shed a stray tear for home. As it rose higher and higher, she buried her face in her backpack. It still smelled like her father’s cigar smoke, and her mother’s lavender perfume.

It still smelled like the spices of a world that, whether she knew it or not, she would never belong to again.

by Caitlyn Deutsche

The Dazed Starling: Unbound About The Publication

The Dazed Starling: Unbound is an online publication of the Bachelor of Fine Arts in Creative Writing program at California Baptist University. Its goal is to extend CBU’s Dazed Starling student literary journal’s mission by offering an additional publication opportunity open not only to current CBU students but also to faculty, alumni, and friends of the university. The Dazed Starling: Unbound also seeks to extend the creative voice of The Dazed Starling student literary journal with additional emphasis on visual arts.

Each edition is thematic, and theme for the inaugural edition of The Dazed Starling: Unbound is “unbound.” In these pages we have welcomed various interpretations of this theme, including, but not limited to, the exploration of freedom, what sets us free, taking flight, the unlimited, escape from confinement (literal and figurative), going beyond expectation, etc.

https://blogs.calbaptist.edu/dazed-starling/