5 minute read

Through the Looking Glass Again

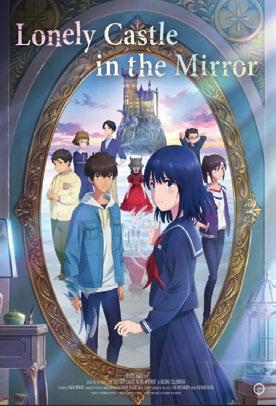

A young heroine finds a shelter from bullies in Keiichi Hara’s new animated feature Lonely Castle in the Mirror.

- By Charles Solomon -

Bullying is a serious problem children face, especially in Japanese schools. According to the Mainichi newspaper, more than 600,000 incidents of bullying were reported to the education ministry in 2021. The number of “serious incidents” that produced long absences and even suicides rose to 705.

Kokoro, the heroine of Mizuki Tsujimura’s best-selling novel Lonely Castle in the Mirror and Keiichi Hara’s new animated adaptation, is the victim of one of those “serious incidents.” After being terrorized by her classmates, she refuses to return to Yukushina #5 Junior High School — or leave her house. Kokoro spends long, dreary days watching TV, napping and eating the lunches her mother prepares — until one day, the mirror in her room begins to glow mysteriously.

Echoes of Alice

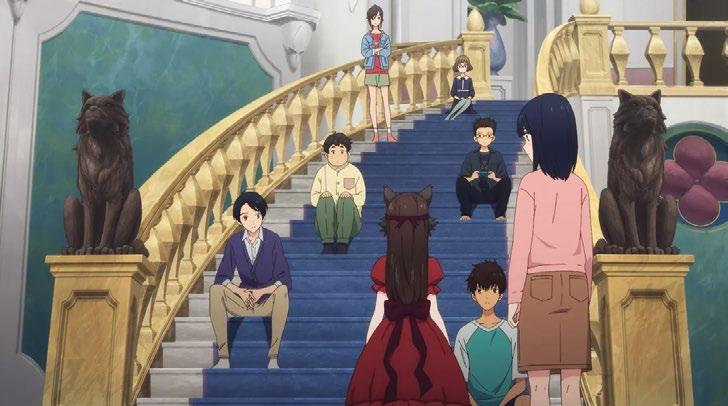

Kokoro passes through the mirror, like Alice through the Looking Glass, and finds herself in a mysterious castle where six other children with similar problems have been summoned. A masked girl who calls herself the Wolf Queen makes two crucial announcements: 1) The castle will exist for only a finite time and 2) whoever finds the key hidden within it will have a single wish granted — any wish.

Hara discussed the film in a recent interview conducted via email. He discovered the novel when he was approached by Shochiku Studio: “I received a request from the producer there saying, ‘We want to make this novel into an animated movie.’ I accepted, so I read the book for the first time.“

Tsujimura’s novel is arguable too long — more than 350 pages in the English translation — and somewhat repetitious. Condensing and shaping the story required major efforts by Hara and screenwriter Miho Maruo. “The length was the most difficult part when I visualized the novel,” Hara explains. “If we were to depict all the material about all seven children, it would not have been possible to fit it into the two-hour film, so we focused on the episodes involving Kokoro, the protagonist of the original book. I pared down the episodes of the other children and their home environments as much as possible for the movie.”

Like Makoto Kobayashi, the junior high school suicide victim in Hara’s highly praised Colorful (2010), Kokoro begins as a rather unlikable character: bored, diffident and bitter. Her wish would be to make the girl who led the bullies suffer. Transforming her into a heroine who could win audience’s sympathy and hold their interest for two hours posed additional challenges.

“I think this is where a film director can demonstrate his or her power most effectively,” Hara says. “It was a test for me as a director, to convincingly portray the transformation of an initially unsympathetic child into a credible main character. I think we were successful.”

But if Kokoro seems unlikable initially, it’s partially a reflection of the trauma she’s experienced. Hara realized that while he need- ed to make Kokoro more sympathetic, it had to be clear she wasn’t merely a petulant adolescent. The audience had to understand the pain she suffered from her classmates’ attacks — because it reflected a very real problem.

“I’m aware that bullying is a very serious problem,” he states. “I think it’s really unfortunate that children who have only lived for 10 years or so are desperate about their future. Bullying existed when we were kids, too, but there are differences between then and now. Today, on top of in-person bullying, I think bullying using social media is increasing. We hope that through this film, we can help dissuade kids from making the worst decisions.”

Tsujimura describes the Lonely Castle as “a castle from a Western fairy tale with a magnificent gate.” Kokoro and the other kids never see it from the outside, and the author doesn’t give the reader much of a sense of the architecture. Creating a look for the castle was left to Hara and designer Ilya Kuvshinov (The Wonderland).

“I asked Ms. Tsujimura if she had a visual image of the castle — for example, an old castle in Germany,” Hara explains. “She told me she didn’t have a concrete image, so I came up with my own. It shouldn’t be a luxurious castle since it’s for kids with problems. I thought the exterior should be a rugged medieval-style castle built for battle. On the other hand, I imagined the interior to be gorgeous and spacious with European furniture. That’s how I asked Ilya-san to make it. In terms of where the castle should be, I thought it would be interesting to build it in a real place called ‘Ball’s Pyramid,’ which is a rock 572 meters tall sticking up in the Australian sea that I happened to see on TV.”

The forbidding towers were built in CG and the drawn characters had to be integrated into the backgrounds. “I don’t have a very detailed knowledge of CG, so I sometimes end up making requests of the CG team that are impossible,” Hara admits. “I get involved in making an animated film roughly once every three years, and each time I’m amazed by the dramatic progress of the technology. At the same time, I learned that some of my requests take a very long time and a lot of work.”

As the small group of outcasts spends time together, they discover they have more in common than they initially realized. How could they all have attended Yukushina #5 Junior High School yet never encountered each other in the real world? For the first time, Kokoro and the others learn to trust and care about their fellow students. Their shared bond gradually replaces their individual wishes. Can they find a way to thwart the Wolf Queen’s rules and preserve their friendships, even after the castle ceases to exist?

A Labor of Love

Looking back over the unusually long production time Lonely Castle required, Hara reflects, “This film took a long time to make — five and a half years — and many things happened during that time. Takashi Nakamura, who was originally supposed to oversee art direction, passed away suddenly. One of the producers gave birth to a child. I felt the changes in the lives of the people who were involved in the making of this film. I was also surprised to turn 60 years old myself!”

“I’ve been very lucky to be able to live my life only working on films,” he concludes. “Lonely Castle in the Mirror has grossed more than ¥848 million (about $6.3 million in U.S. dollars) at the box office worldwide. It’s become an important work for me in that respect. I may have disappointed my investors and myself with my past films, but I’m grateful to have been able to make this one. The theme of this film is relevant not only in Japan, but also in the rest of the world. I’m looking forward to seeing how people perceive it overseas and how they respond to it. I have no worries, just excitement.” ◆

Lonely Castle in the Mirror is one of the features in the competition lineup at the Annecy Festival in June. GKIDS will release the movie on June 22 and 23 in select U.S. theaters.