Committed to Jekyll Island

At Ameris Bank, our customers and the community are always at the center of everything we do. From big-ticket decisions to everyday services, we’re committed to serving our neighbors on Jekyll Island.

40 Off the Table

To understand the modern evolution of Jekyll Island‚ you need only look at turtle soup.

By Osayi Endolyn30 Catch Your Dinner (or Have Fun Trying)

Everything you need to know to pull off a DIY seafood feast.

By Josh Green56 Time and Place

Take a walk through the ages at the newly opened Mosaic‚ the Jekyll Island Museum.

By Josh

Green64 Long Gone Summers

Peppermint Land‚ Ski Rixen‚ and one really bumpy ride: Revisiting Jekyll’s boldest attempts to reel in tourists.

By Tony Rehagen46

How to Get Along with Gators

Jekyll’s alligators are more prolific—and closely monitored—than the average visitor might guess.

By Candice Dyer

By Candice Dyer

Stained glass at Faith Chapel.

Dear friends,

executive director

C. Jones Hooks director of marketing & communications

Alexa Orndoff

creative director

Claire Davis

Photography courtesy of Jekyll Island Authority unless otherwise noted. This magazine was published by the Jekyll Island Authority in cooperation with Atlanta Magazine Custom Media. All contents ©2019. All rights reserved.

publisher

Sean McGinnis

editorial director

Find us on social media:

@jekyll_island

@JekyllIsland

about

31 · 81

Published twice a year, 31·81 pairs stunning photography with thoughtful articles to tell the stories of Georgia’s unique barrier island.

Jekyll Island lies at 31 degrees north latitude and 81 degrees west longitude.

subscribe

To subscribe at no charge, sign up at jekyllisland.com/magazine.

To update your subscription information, email magazine@jekyllisland.com.

Kevin Benefield

design director

Cristina Villa Hazar

senior editor

Elizabeth Florio

art director

Liz Noftle

associate publisher

Jon Brasher

travel sales director

Jill Teter

production director

Whitney Tomasino

For generations of families‚ a summer vacation on Jekyll is a cherished tradition‚ and this is the time of year we prepare to welcome people of all ages back to the island they love. We also have the privilege of introducing first-time visitors to our island’s fascinating history and enchanting natural beauty—and helping them forge lasting memories of their own.

As faithful stewards of the island‚ we are charged with protecting Jekyll’s irreplaceable ecosystems and preserving its captivating historic places. Yet we must also serve the needs of visitors and residents. Having completed a carrying-capacity and infrastructure assessment last year‚ we now have a powerful tool to assist us in maintaining the delicate balance that’s at the core of our mission. The primary goal of the study was to examine the number of people‚ vehicles‚ and development the island can accommodate while still safeguarding its unique natural character. By monitoring this data‚ we can adopt a proactive approach to managing visitation while making Jekyll inviting and accessible to new generations so they can develop their own authentic connections to the island.

Speaking of development‚ Mosaic‚ the reimagined Jekyll Island Museum‚ opened in April and now serves as a base camp‚ educating visitors as they plan their explorations of the island. The museum’s modern‚ interactive exhibits tell compelling stories from thousands of years of human habitation on the island. Mosaic also encourages curiosity about Jekyll’s vibrant landscapes and the thriving wildlife populations they support.

I hope you will use Mosaic as a gateway to new discoveries on the island, whether on your first visit to Jekyll or your fiftieth.

Jones Hooks

Executive

Director, Jekyll Island AuthorityJEKYLL ISLAND AUTHORITY BOARD OF DIRECTORS

Michael

D. Hodges chairman St. Simons Island, GA William H. Gross secretary/treasurer Kingsland, GA Mark P. Williams commissioner, georgia dnr Atlanta, GAA.W. “Bill” Jones III Sea Island, GA

Robert

W. Krueger vice chairman Hawkinsville, GAJoy A. Burch-Meeks Screven, GA

Dr. L.C. “Buster” Evans Bolingbroke, GA

Hugh “Trip” Tollison Savannah, GA

Joseph B. Wilkinson St. Simons Island, GA

As faithful stewards of the island, we are charged with protecting Jekyll’s irreplaceable ecosystems and preserving its captivating historic places.”

Inspiration Aplenty

When I tell people about this magazine‚ I often get the same question. “Won’t you run out of ideas?” After all‚ Jekyll is a mere seven miles long and a mile-plus wide. I’ll admit I had the same concern for about five minutes. Then I sat down with Jekyll Island Authority staff members for an initial brainstorming meeting in 2016‚ and one look at their robust idea file laid my concerns to rest.

Jekyll owes its depth of history‚ in part‚ to the fact that a bunch of wealthy Northerners picked it as their private retreat in the early twentieth century. If you leafed through any of the previous five issues‚ you know the likes of J.P. Morgan and William Rockefeller had homes here. Thus little Jekyll has some big claims to fame—like hosting the financial summit that devised the Federal Reserve System (talk about a brainstorming meeting). In 1947‚ the State of Georgia bought the island and transformed it into a public paradise‚ adding midcentury flair to the Victorian scenery. One story we’ve been excited to tell since day one is about the bygone attractions of this era‚ including an amusement park called Peppermint Land (page 64).

Our deepest well of ideas is not Jekyll-specific‚ of course‚ and that’s nature. Yes‚ we write about inhabitants of this specific barrier island‚ including bobcats‚ rattlesnakes‚ and the 110 or so large alligators that call it home (page 46). But the magazine’s illumination of small things—Spanish moss and resurrection fern‚ tiny coquina clam shells and the humble sand dollar (page 16)—has shown the rewards of looking closely‚ wherever you are.

There’s one story I’d been dreading. Fishing is a big deal on Jekyll‚ but it’s not exactly my area of expertise. I’ve cast a line approximately three times ever. As we discussed the approach for a fishing guide‚ Meggan Hood‚ former senior director of marketing for the Jekyll Island Authority‚ said‚ “Let’s write a primer for the Elizabeth Florios of the world.” That sounded good to me—and kudos to Josh Green for pulling it off (page 30). His story makes me think I could at least have fun trying to catch my dinner‚ which I guess is the point‚ though a fish fry would be nice.

Elizabeth Florio Editor

1 Josh Green is a freelance journalist and fiction author who lives in Atlanta with his wife and daughters. His work has won top accolades in his native Indiana and

in Georgia‚ including a 2017 Atlanta Press Club award for magazine writing. A contributing writer at Atlanta magazine and editor of Curbed Atlanta‚ Green is working with his literary agent to market

his first novel. His book of short stories‚ Dirtyville Rhapsodies‚ was published in 2013.

2 Amy Holliday is an artist and illustrator using primarily traditional mediums such as graphite and watercolors. She loves illustrating all things related to the natural world‚ as she is passionate about conservation and environmentalism‚ and she hopes to inspire others through her work. She works from her cozy home studio on the edge of the Lake District in the North of England.

The Doctor Is In, Even When You’re Out of Town.

Our deepest well of ideas is not Jekyll-specific, of course, and that’s nature.”

MOSAIC, THE JEKYLL ISLAND MUSEUM

Now Open

Get an introduction to Jekyll’s teeming wildlife and rich history at the new Mosaic museum. The historic building, which underwent a $3.1 million transformation, displays a rotating mix of artifacts that visitors can explore through interactive displays and audio elements. The museum is open daily from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m., excluding major holidays. Tickets cost $9 for adults and $7 for children (free for kids three and under). Specialty tours of the museum and historic district are also available. jekyllisland.com/mosaic

Beach Village Music Series

First Saturday of the month‚ June–September Dance along to the soundtrack of summer at these free concerts on the Village Green. Bring a picnic and chair‚ or stock up on dinner at nearby shops.

Swim-In Movie

June 1, 30

What’s more fun than Summer Waves Water Park’s wave pool? Watching a movie in it! Get comfortable in an inner tube for a classic screening of Jaws on June 1‚ and laugh along with Trolls on June 30. Tickets are $15 and include entry to the park after 4 p.m.

Independence Day Celebrations

July 4–5

Shrimp & Grits Festival

September 20-22

Besides feasting on creative renditions of this Southern staple‚ scope out a thoughtfully curated artists market‚ hear live music‚ and sip craft brews.

Goblins on the Green

October 26

Trick or treat through Beach Village shops before settling in with candy for a screening of The House with a Clock in Its Walls

Georgia-Florida Golf Classic

October 31–November 1

The SEC rivalry comes to the island during this annual golf tournament‚ where the winner takes home a championship ring. tess malone

Movie on the Green

Last Saturday of the month‚

May–November

BYOB (bring your own blanket) for free movies on the Village Green. Family favorites include Ralph Breaks the Internet Mary Poppins Returns‚ Smallfoot‚ Aquaman and Bumblebee

Kick off the Fourth with the Independence Day Parade through the historic district; deck out a bike‚ pet‚ or yourself to compete for “Most Patriotic Person.”

Watch fireworks over the ocean after dark.

On the fifth‚ bring the kids for an afternoon of bounce houses‚ music‚ and waterslides on the Village Green at Red‚ White‚ & Bounce.

JEKYLL TOPS THE LIST

No. 1 “20 Best Places to Go in 2019‚” Money magazine No. 2 “19 Best Beaches for Families and Kids‚”

NBC’s Today show No. 10 (Driftwood Beach): “2019 Travelers’ Choice Awards - Best Beach‚” TripAdvisor

Club member John J. Albright owned Jekyll's PulitzerAlbright Cottage. Pictured here is his son-in-law, Laurence Hurd, circa 1930.

Red Bugs

In the 1920s, the best way to get around Jekyll was in a jaunty electric roadster

BY REBECCA BURNSBanish visions of Teslas and Prius Primes; the eco-friendly runabout favored by tobacco tycoon Pierre Lorillard and his fellow Jekyll Island Club members was an open-air buckboard. To get around the island‚ club members relied on these electric “cyclecars‚” affectionately known as Red Bugs.

The cars‚ which could reach speeds of twenty miles an hour‚ came to Jekyll at the suggestion of Jekyll Island Club carpenter Chris Nielsen‚ who when searching for bicycle wheels came across a company called Briggs & Stratton‚ maker of an electric vehicle called the Flyer. More like a souped-up go-kart‚ the Flyer featured a highly varnished wood frame and five wheels‚ the fifth at the rear to aid with steering and braking.

Nielsen and the club president ordered a test Flyer and soon the vehicles‚ which easily zipped over the oyster-shell paths of Jekyll‚ became all the rage.

The club kept several to rent out‚ but many families ordered their own.

The Flyer‚ which bore a closer resemblance to a modern dune buggy than to an enclosed car‚ was marketed as a cheaper alternative to larger cars. Gas-powered engines were later added. A 1917 ad in the Bainbridge‚ Georgia‚ Post-Searchlight touted the Flyer’s ability to get eighty miles to the gallon and its price of just $125.

Briggs & Stratton later sold the rights to a New Jersey company‚ which named the runabout Auto Red courtesy of

Bug. The cars were popular up and down the Eastern Seaboard at island resorts such as Jekyll. A version was even sold in France as “Le Red Bug.”

On Jekyll‚ club members were instructed to leave their automobiles at home. “It was keeping with the philosophy of getting back to basics‚ leaving the technology and stress of their modern lives behind‚” says Meggan Hood‚ former senior director of marketing for the Jekyll Island Authority. Business leaders happily traded their sedans and touring cars for these quirky little vehicles.

RIDE A VINTAGE RED BUG

At Jekyll’s new museum‚ Mosaic (see page 58)‚ you can test-drive the original Red Bug in a special exhibit on the vehicles. A replica cyclecar is equipped with a special seat that re-creates the bouncy feel of cruising on beach paths‚ while a screen “moves” you through island scenery at twenty miles an hour.

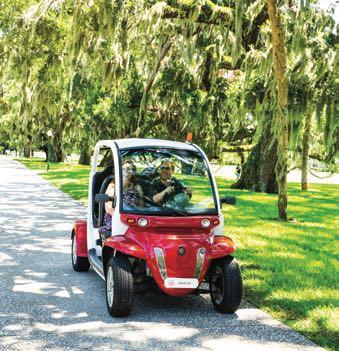

RIDE A MODERN RED BUG

Like a Rockefeller or Pulitzer‚ you can get around Jekyll on a Red Bug‚ albeit a modern version from local company Red Bug Motors. The street-legal electric carts are available with two‚ four‚ and six seats. Rentals start at $95 for twenty-four hours‚ with discounts for five-day rentals. redbugmotors.com

On Jekyll, club members were instructed to leave their automobiles at home.

Marsh Grass

It’s a golden refuge for life of all kinds

BY TESS MALONEThe brilliant hue of Spartina alterniflora in fall gives the Golden Isles their name‚ while the grass grows emerald in spring and summer. All year long‚ it sustains an abundant ecosystem.

Marsh grass feeds aquatic residents. Periwinkle snails and manatees munch on it‚ while fiddler crabs use it for shelter and make sure the snails don’t overindulge.

These aquatic residents‚ in turn‚ feed mammals and birds‚ from eye-catching roseate spoonbills foraging at low tide to covert mink.

Seafood restaurants can thank it for their catches. Dead grass washes up on beaches‚ providing a home for crabs‚ clams‚ oysters‚ shrimp‚ and fish.

It’s nature’s filter. Sediment in spartina traps pesticides‚ heavy metals‚ nutrients‚ and other toxins from the water.

Storms are no match. It acts as a buffer against erosion from heavy tides and hurricane damage.

It’s pretty‚ but don’t pocket it. Collection is illegal thanks to the Coastal Marshlands Protection Act passed in 1970.

Sand DOLLARS

BYSand dollars have more in common with people than you might think. Scientists have discovered that the genomes of humans and sea urchins bear notable similarities; they’re our closer kin than beetles‚ crabs‚ or clams. But in most ways they’re entirely foreign.

“If you want to be a stickler‚ their proper name is the five keyhole urchin‚ in the family of echinoderms‚ Latin for ‘spiny skin‚’” says Ben Carswell‚ director of conservation for the Jekyll Island Authority. “But most people‚ even naturalists‚ still call them sand dollars.”

They breed by broadcasting‚ in which males and females release thousands of sperm and eggs into the water‚ which connect and

develop into larvae. Thread-like appendages called cilia help the larvae move and burrow into the sand. When threatened‚ baby sand dollars clone themselves‚ a sort of evolutionary insurance.

These radial discs are abundant on Jekyll‚ especially between tides‚ when they might turn up by the half dozen within a few square feet. If you are beachcombing and pick up a brown one with tiny tube-like feet that feel like velvet fur on its underside‚ it is alive‚ and you are encouraged not to disturb it. “We want to send the message not to be wasteful of a life just because it’s

a simple life‚ and they are fragile when they’re alive‚” Carswell says. However, visitors are welcome to make souvenirs of the calciumbased skeletons‚ which are smooth‚ white‚ and brittle.

Living sand dollars spend their days tunneling into the sand and using their feet to sweep organic matter and single-celled organisms into their mouths. They in turn are preyed upon by fish‚ crabs‚ gulls‚ and rays. “Sand dollars are an important food resource‚” Carswell says—but don’t be fooled by their cookie-like shape. “So far I’ve never heard of anyone using them as bait.”

Living sand dollars range from gray-brown to dark purple and are covered in fuzzy hairs.

The sun-bleached skeletons we know them by represent a strange‚ simple life

CANDICE DYERBY TONY REHAGEN

In November of 2014‚ pilot Leslie Weinstein got a call about some passengers needing a lift from New England down to a winter home on Jekyll Island. But these were no ordinary snowbirds. The voice on the other end of the line was that of Terry Norton‚ founder‚ director‚ and veterinarian at the Georgia Sea Turtle Center. Norton informed Weinstein there were fifty sea turtles stranded off the coast of Cape Cod that needed immediate medical evacuation to Jekyll. If the animals didn’t make it to the turtle center soon‚ the members of an already endangered species might not survive.

Weinstein was the perfect man for the job. He was the son of a pilot and had grown up outside of St. Augustine, about 100 miles south of Jekyll. As a boy‚

he’d dig up turtle eggs from the beach and carefully move them to his family’s private sands‚ safe from hunters who sold the eggs as delicacies to local restaurants. He’d then carry the hatchlings in a bucket to release them in the ocean. As an adult running his own aviation business‚ Weinstein still had an affinity for the creatures. He arranged for three aircraft and three volunteer pilots to make the run and save the turtles—the largest single rescue mission of its kind. It would not be the last for Weinstein and company. Each year‚ beginning around November‚ hundreds of loggerheads‚ leatherbacks‚ hawksbills‚ and other species get caught in the dropping water temperatures of the North Atlantic. The cold-blooded reptiles can’t adapt and become “cold-stunned”—their body sys-

tems‚ including circulation‚ metabolism‚ and cognition‚ slow and eventually shut down. They are unable to swim south to warmer waters. Turtles Fly Too‚ as Weinstein dubbed his nonprofit‚ is a nationwide network of more than 500 aviators who volunteer their time and equipment to deliver sea turtles from danger all along the East Coast. They partner with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration to give the turtles a lift. Destinations include inland aquariums and research centers throughout Florida‚ but with its Georgia Sea Turtle Center and a population particularly attuned to protecting wildlife‚ Jekyll Island is a prime landing spot. Each year between twenty and sixty of the 500-plus stranded animals come to Jekyll‚ where they are treated and can convalesce until the water warms in March or they’re deemed healthy enough for release. The center has treated 238 cold-stunned sea turtles since its opening in 2007. “Our daily routines are shot‚” says

Michelle Kaylor‚ rehabilitation specialist at the center. “But even though it’s a ton more work‚ our folks are excited about cold-stunning season. The reward is in getting to see the animals get better and see them released.”

and gifts that are sure to evoke precious Jekyll Island memories for years to come.

32 Pier Road

912-635-2643

thecottageji.com

Open Water

BY REBECCA BURNSIn 1948‚ Pittsburgh Post-Gazette reporter Roy Sprigle traveled undercover through the South to report on life under Jim Crow. Three thousand miles into his journey‚ he reached Brunswick‚ only to learn that “along all the hundred miles of Georgia’s coast line with its scores of beautiful island and shore beaches‚ there’s not a single foot where a Negro can stick a toe in salt water.” Indeed‚ the fine for swimming in the ocean was $50. Not long before Sprigle’s arrival‚ three young women were arrested for simply trying to swim at a Glynn County beach.

“Georgia bought the fabulous Jekyll Island‚ playground of the Rockefellers‚ Whitneys and Bakers for $800‚000. It will build a great seashore resort for the citizens of Georgia‚” wrote Sprigle. “But there will be no accommodations for Negroes‚ despite pleas by most of the Negro organizations in the state.”

Two years after Sprigle’s visit‚

black residents of Brunswick petitioned the state for access‚ and in 1950‚ a portion of southern Jekyll‚ renamed St. Andrews Beach‚ was designated for blacks‚ becoming the first public beach in Georgia accessible to African Americans. Five years later‚ the state erected the “Colored Beach House,” which now stands as a historic landmark at Camp Jekyll.

Oral history exhibits at Mosaic‚ the Jekyll Island Museum‚ recount memories of Jekyll during the segregation era.

One features Jim Bacote who as a teenager testified in the 1964 class action lawsuit that led to the integration of Georgia’s state facilities.

As Georgia’s only beach available to blacks‚ St. Andrews developed a following of loyal vacationers and‚ with construction of the Dolphin Club and Motor Hotel‚ became a prime spot on the comedy and music “Chitlin’ Circuit‚” hosting acts such as Percy Sledge and Millie Jackson. To host a convention of black dentists‚ the state erected South Beach Auditorium in 1960. It was not until 1964‚ more than a decade after the opening of St. Andrews Beach‚ that the passage of the Civil Rights Act mandated all of Jekyll’s beaches be integrated.

Jekyll’s St. Andrews Beach was the first—and for years, only— section of Georgia coast accessible to African AmericansJekyll Island beachgoers in the 1950s

Ben Galland is a coastal Georgia boy‚ born and bred. The Brunswick business owner and photographer grew up on St. Simons‚ the lush barrier island where live oaks and white-tailed deer flourish. The natural beauty of his hometown and its less-developed neighbor‚ Jekyll‚ captured his imagination and set him on the artist’s path at a young age.

“Dad was an amateur photographer‚ so my interest started early‚” he says. The thirty-six-yearold majored in visual communications at Berry College‚ then spent six months studying photography in Florence. He honed his eye traveling around Italy on weekends with his girlfriend (now wife). “It was mostly street photography‚” he says. “Very urban. Lots of people.”

Fast-forward fifteen years. Galland and his wife are raising two children on St. Simons and celebrating the tenth anniversary of H2O Creative Group‚ the Brunswick marketing and design agency he co-founded. He handles all of the firm’s photography. “Fortunately I get to do exactly what I went to school for‚” he says. “But owning a small business can be draining. That’s when I find solace in my art.”

That art is nature photography. For the past decade‚ Galland has been documenting Georgia’s barrier islands for a series of books published by UGA Press. The series started with a book about St. Simons; one on Sapelo soon followed. In 2016‚ Galland reunited with Jingle Davis, who wrote the St. Simons book‚ to produce Island

Passages: An Illustrated History of Jekyll Island.

This engaging overview of Jekyll’s history and natural environment is written with a reporter’s flair—Davis was a longtime journalist at the Atlanta Journal-Constitution—and illustrated with Galland’s sumptuous photographs.

“Shooting St. Simons was easy‚” he says.

“Like second nature.” But the Jekyll project was different. The island was plenty familiar to Galland—his parents took him there as a child for

the occasional excursion or fancy dinner—but suddenly he was seeing it through new eyes. “The smaller population‚ the lack of development . . . They allow a certain serenity you don’t have on St. Simons. So much of Jekyll is pristine. And the parts that are developed are so well maintained‚ the architecture so beautiful. For the first time‚ I was seeing it all as a photographer. It felt like a brand-new love affair.”

Speaking of love affairs‚ these days Galland is playing around with drones. Overhead photography is his latest passion and will likely play a starring role in upcoming books‚ one about Cumberland Island‚ the other about tabby‚ the oyster-based building material integral to the history of the coastal South. Staying inspired—finding new ways to see old things—seems almost like a moral imperative to Ben Galland. “I’m not the type to stand on the street corner and protest‚” he says. “But there are many kinds of activism. I love our coastal environment. If a photograph of mine makes somebody feel the same way and think about our need to protect it‚ I’m very happy.”

“I like to watch them swim away. I’ve seen two get loosed [released]. They swim fast in the water, but on the land they are slow. Sometimes Dr. Terry [Norton, of the Georgia Sea Turtle Center] has to give them a push to get them going, and then they have to dive. But some turtles, like Shawny, can’t dive down. We call him ‘bubble butt’ because his bottom stays up in the air . . . They are endangered species and I just really love them and want to save them.” —gracie weber

As told to JENNIFER SENATOR • Photograph by BRIAN AUSTIN LEE

gracie weber, age seven, has visited jekyll island since she was three years old, and in 2018 she attended sea turtle camp at the georgia sea turtle center. gracie raised nearly $300 for the center by holding a fundraiser in her hometown of sugar grove, ohio, where she rescues stray box turtles.

How to CATCH YOUR DINNER

By JOSH GREEN Photography by GABRIEL HANWAY

A clueless fisherman from the big city attempts to reel in a feast on Jekyll

A clueless fisherman from the big city attempts to reel in a feast on Jekyll

’m

II’m not too macho to admit I rarely go fishing because‚ for one thing‚ I feel sorry for the fish. Getting caught by the lips can’t be pleasant. Another problem is that I have no patience. But the main issue is that I’m as clueless about fishing as an old man at a Fortnite convention. That much was obvious one December afternoon at Clam Creek Fishing Pier‚ off Jekyll’s northern tip‚ when I baited my hook with dead shrimp (easier than worms) and extended my telescopic rod‚ a dusty‚ rusted $20 Walmart contraption I’d found in my garage. It just kept stretching. It was the length of a shuttle bus—ridiculously‚ embarrassingly long—and meant for hauling in very big fish offshore. To make matters worse‚ a winter storm was unfurling off the choppy Atlantic. Hardly idyllic conditions.

Suddenly‚ though‚ I heard a “Bwaaah!” beside me. It was my wide-eyed eldest daughter‚ Lola‚ seven‚ wearing a Santa cap and flowered raincoat, clutching her tiny fishing pole. Through her missing front teeth she hollered‚ “I think I got one!”

And thus our clumsy‚ island-wide fishing and crabbing expedition had begun.

Before hauling my family down from Atlanta for our first Jekyll visit, I’d done some homework. Both Paul Medders‚ a friendly marine biologist with the Georgia Department of Natural Resources‚ and Captain Brooks Good of Coastal Outdoor Adventures pointed me to the pier as the island’s best spot for crabbing—and where a novice angler might get his bearings and hook a sheepshead‚ whiting‚ or flounder before trying the beaches. This barrier island‚ it turns out‚ is a treasure trove of wildlife. It’s the westernmost point on the

ETHICAL CODE IS JUST NOT BEING WASTEFUL.”

Eastern Seaboard‚ basically due south of Cleveland‚ Ohio. And as part of the “Georgia Bight‚” it’s a tucked-away cove of marshes‚ creeks‚ and tributary rivers‚ all richly productive environments for marine animals‚ fish‚ and shellfish.

Several Jekyll and St. Simons charter captains are available for offshore excursions. Good's company, for example, offers a two-hour family excursion beginning at $350. For kayakers‚ fishing (preferably with non-gigantic poles) is popular in creeks and marshes. Options abound‚ as Medders explained‚ for shore fishing as well‚ and it’s a “very common thing” for visitors (angling neophytes

included) to reel in enough fish‚ crab‚ or shrimp to feed themselves. “There’s a lot of good eating fish that can be caught at certain times of year in abundance‚” Ben Carswell‚ the Jekyll Island Authority’s director of conservation‚ told me later. But there’s a Golden Isles golden rule‚ so to speak. “The ethical code‚” said Carswell‚ “is just not being wasteful.”

All the supplies we needed cost about $66‚ including a yearlong fishing license. (Tip: buy the license on your smartphone and take a screenshot so you’ll instantly have a copy‚ in case DNR asks.)

Lola and I swung into the Jekyll Island Fishing

“THESt. Andrews Beach Park

Center next to the pier and bought the basics: a bucket ($7.99); frozen shrimp bait ($7.99 for a bag that would’ve lasted two days); filet knife ($7.99); a two-ounce sinker and small hook good for swifter tides (generously attached for me by the staff); a crab basket ($14.99 with weight and strings); and two bags of chicken necks ($2.99 apiece) for luring crabs. In and out in fifteen minutes.

Back on the pier‚ Lola fought and caught her first fish‚ lugging it up by herself. My voice recorder captured me sputtering this nonsense to her: “Yes! It’s a striper‚ or sheepshead. No‚ a pretty fish! A yellow fish!” Before she darted off to tell mom Lori and little sister Marley‚ four‚ I asked if she’d like to watch me try to clean it‚ as the pier has a measuring and cleaning station. Her face pinched at the very thought. So I wrenched out the hook and tossed back what Carswell later confirmed was a croaker‚ which are less commonly eaten and tough to clean anyhow.

Elsewhere, I’d slowly lowered the baited crab basket into maybe six feet of water near the pier’s pilings‚ checking it every fifteen minutes as advised. (Note: children can’t stop themselves from pulling up the basket every twenty-five seconds.) On my third check‚ a thrillingly large blue crab was down there! But it was on its back with legs not entangled‚ and it slid off‚ sadly‚ halfway up.

We moaned and moved on to a small bridge over nearby Clam Creek‚ another hot spot. But we’d missed high tide (check the free Go Outdoors Georgia app for tide schedules to avoid that)‚ and the water was too shallow. No crabs or fish but a grand view of golden marshes.

With cold rain starting to spit‚ we darted a few miles south to the brackish pond behind 4-H Tidelands

Nature Center‚ a kid-friendly spot with ADA-accessible docks. Both Medders and Carswell said it’s home to surprisingly large saltwater species‚ including the one-time state record pinfish. Within seconds of casting her shrimp‚ Lola nailed another croaker‚ and then another‚ both purplish and wonderful. Impatient Marley lugged the empty crab basket up and down‚ skimming her little fingers across the pond’s surface. (I later learned this is a known alligator habitat‚ and little fingers should stay safely out of the water. Oops.)

Our last stop‚ the true fiasco‚ was at the island’s southernmost point near Glory Beach Park‚ where skies darkened and waves crashed in cappuccino swells. (Tip: shore fishing is easier on days your daughter isn’t hollering, “I’m gonna get blown away!”) We were resolute to catch just one more fish‚ and . . . we didn’t. Shin-deep in oncoming tide‚ we laughed at the futility of trying to cast‚ although my ludicrous rod was finally in its element. When I noticed the girl was starting to really worry‚ longing for the sunny beaches she’d experienced the previous day while I was working‚ we tossed the shrimp into the sea and loaded up.

Final tally: Dad‚ zero bites (renegade crab notwithstanding). Daughter‚ three fish (enough for a sandwich or two‚ I’m sure). Six hours of hapless adventure. And one day we’ll never forget.

SO, WHAT’S SUP?

SUP fishing (short for standup paddleboarding) is for Jekyll visitors who prefer to combine adventurous exercise with their casting. Anyone with a basic grasp of SUP fundamentals can take tours offered by Golden Isles native Jason Latham‚ a professional standup paddle surfer ($65 per hour‚ all equipment provided).

Latham’s adept at finding fish around the island’s oyster beds‚ marshes‚ and manmade structures. He stores the hauls in a cooler that doubles as a seat‚ and tour patrons typically take home a meal’s worth. But the ultimate experience is a “Golden Isles Sleigh Ride”—hooking something big that tugs the board around‚ which “really gets your blood flowing!” says Latham. For bookings and more info‚ visit jlaysup912.com.

ALL THE BASICS FOR CATCHING (and eating) YOUR DINNER

FIRST STEP: Anyone sixteen and up who wants to catch something live in Georgia (including crab and shrimp) needs a license. They cost $15 per year for Georgia residents ($50 otherwise) and can be obtained at most tackle shops, by calling 800-366-2661, or online at GoOutdoorsGeorgia.com.

Fishing

Where: Jekyll is dotted with terrific shorefishing locations, from St. Andrew’s Beach and Glory Beach parks in the south to Oceanview Beach Park to areas near Driftwood Beach in the north.

When: All year. In general it’s best to fish when tides are not swiftly moving‚ either in or out. Sunshine and clearer waters help fish see the bait. But other anglers along Jekyll’s northern tip‚ as observed for this story‚ had no trouble filling buckets with fish during a stormy December day. Croaker and whiting especially tend to bite all year.

What: Whiting‚ redfish‚ flounder‚ croaker‚ small sharks‚ and stingrays—to name a few— are plentiful in most seasons and commonly hooked from beaches. Insider tip: large tripletail fish congregate off Oceanview Beach Park in summer‚ while spotted seatrout gather in channels during autumn’s first cool snaps.

Good to know: Be mindful of size regulations and bag limits. That information (and images of specific fish) can be found by searching “Georgia Fish Regulations” online.

Prep 101

• Once caught‚ store fish in ice water immediately to protect flavor.

• Using a sharp filet knife‚ remove head‚ guts‚ scales‚ and bones.

• For vacationers‚ a classic‚ easy means of preparing most fish is frying. Dip filets in icy water with salt, roll in a fish-fry mix (Zatarain’s makes a good one), and then cook in fryer with vegetable oil at 400 degrees until crispy.

Crabbing

Where: Experts advise crabbing off Clam Creek Fishing Pier or a small bridge over the creek a short walk to the east.

When: All year.

How: Tie a chicken neck or fish head in a weighted crab basket and drop from an elevated place into water at least a few feet deep. Tie off the basket and be patient‚ slowly raising it to check every fifteen or twenty minutes.

Good to know: Be mindful of pincers‚ of course‚ and minimum size requirements (five inches across the back for blue crabs‚ the most abundant and best for eating).

Prep 101

• Crabs will live for hours in a bucket with just an inch of water to keep their gills wet; ice isn’t necessary for storage. But for safe handling‚ stun crabs in ice water before cooking.

• Toss them in a pot of boiling water. Add Old Bay Seasoning to water‚ then cook for fifteen minutes or less.

• Remove the top shell with fingers and the triangular abdomen with a knife. Scoop away all but the white meat.

• Serve with melted butter.

Seining

Where: Jekyll’s most popular seining spot for catching a shrimp dinner is the shallows near St. Andrew’s Beach Park.

When: Recreational shrimping season spans from around June to late December.

How: It’s a two-person job; simply dip the net into the water and walk against the outgoing tide. Basic nets begin at less than $20 online.

Good to know: Be mindful of wasting bycatch‚ small fish and crabs that become entangled in the net and stranded onshore. These should be returned to the water.

Prep 101

• Use a large pot with two inches of water (or beer). Bring to a boil and keep on high while adding shrimp.

• Sprinkle generously with Old Bay‚ covering and checking every forty-five seconds. When shrimp start turning pink‚ stir.

• When all are pink‚ remove from heat and pour into a strainer before serving. Avoid overcooking shrimp— less pink is more.

Off theTable

How the disappearance of turtle soup, once an American culinary staple, reflects Jekyll Island’s modern evolution

BY OSAYI ENDOLYN

BY OSAYI ENDOLYN

In St. Louis, widowed housewife Irma Rombauer featured a recipe for green turtle soup in her best-selling tome, the Joy of Cooking first published in 1931. The 1975 edition was updated by Rombauer’s daughter, Marion Rombauer Becker, and is considered the classic among eight iterations that refined the matriarch’s quirky voice and cooking process. In it, she encourages the home cook to consider canned or frozen turtle meat to save time. Of course, “if you can turn turtles, feel energetic and want to prepare your own,” the recipe headnote says, just follow along. The

AAmong recipes for calf’s head soup and oyster gumbo, Abby Fisher included instructions for green turtle soup in her notable 1881 collection What Mrs. Fisher Knows About Old Southern Cooking. A formerly enslaved woman from South Carolina who’d launched an awardwinning preserving and pickling career in San Francisco, Fisher was unable to read or write, but she dictated her expertise with authority: “To two pounds of turtle add two quarts of water, put to boil on a slow fire and cook down to three pints.” The reader is instructed to place thinly sliced hard-boiled eggs at the base of a serving dish, add “a gill” or about half a cup of sherry wine, then pour the salt-and-pepper-seasoned soup tableside while piping hot.

home chef is forewarned that handling “these monsters,” which can reach 300 pounds, is not the typical domain of the residential chef. But if you must, “put them in a deep open box, with well-secured screening on top; give them a dish of water, and feed them for a week” to rid them of the waste of their natural habitats.

It can be difficult to reconcile the celebrated iconography of sea turtles throughout the Southeastern barrier islands with an American appetite that historically indulged in consuming the same species. Once considered a delicacy, turtle soup has become a rarity

breast in oyster sauce, baked bananas au Jamaica, and pineapple meringue pie, the menu included both “Green Turtle Clear au Amontillado” and “Diamondback Terrapin a la Maryland,” a Baltimore dish served with Madeira and sweet cream.

In America, turtle soup’s rich taste—generally speaking, a combination of alligator meat’s texture with duck’s gamey flavor—had won over fans from the perch of the presidency (Washington, Adams, Lincoln, and Truman) to the traveling set on railway dining cars on down to the Campbell’s soup crowd in the 1920s. In its finest settings, the slow-stewed preparation was served with a side of sherry that helped cut the fat while imbuing the dish with a sense of decadence. But the soup began to disappear from American menus, prompting some historians and culinary scholars to ask why.

One observation was that Prohibition in 1919 took fortified wine off the table, rendering one of the most important

since Fisher and Rombauer documented popular recipes of their day (as has mock turtle soup, often an offal-based version). But for much of the twentieth century, the dish held an esteemed place in haute cuisine and home kitchens alike. The Golden Isles were no exception.

Archives from the Jekyll Island Club reveal that turtles were regularly featured on the menu from at least 1912— President Taft was in office then; he adored turtle soup—to 1941. At a dinner celebrating a retiring official in 1914, the club pulled out all the stops. Along with English plum pudding, turkey

For much of the twentieth century, the dish held an esteemed place in haute cuisine and home kitchens alike.In 1903 Lucy Carnegie hosted a dinner on Jekyll for her brother-in-law, steel magnate Andrew Carnegie. Guests included Joseph Pulitzer, J.P. Morgan Sr., William Rockefeller, and Edward Stephen Harkness.

Above: A young girl herds turtles on Jekyll.

Below:

Opposite

ingredients unavailable and illegal. Historians have argued that the collective pause in (legal) alcohol consumption actually helped turtle populations rebound. As industrialization took hold following the Great Depression, Americans’ tastes were shaped by animal meat that was easy to farm, process, and cook: chicken, pork, and beef. Turtles sized appropriately for eating often yield just three to four pounds of meat, to say nothing of the intensive butchering process. Over time, turtles were considered too much work and in many areas retained the whiff of poorer, harder times.

One of the simplest explanations, however, came from Dr. David Steen, research ecologist at the Georgia Sea Turtle Center (GSTC) on Jekyll Island, who wrote definitively in Slate, “There aren’t enough turtles left to eat.” His 2016 opinion piece was a response to a Saveur essay by Jack Hitt from late 2015, in which Hitt accompanied a group of turtle hunters on their annual trek in southwestern Virginia. Hitt brought the reader along on a vivid “cooter hunt” replete with muskrat dens, muddy river water, and plenty of twang. “We were after big turtles with shells the size of dinner plates or steering wheels, heads the size of a man’s fist, and a mouth big enough . . . to guillotine a finger in one swift motion,” wrote Hitt. He linked Americans’ diminished taste for turtles with their tendency to anthropomorphize them into “a loveable cartoon character—see: Yertle, Franklin, Cecil, and Touché, not to mention Donatello and that whole gang.”

But Steen felt one key element of the conversation was missing. Sea turtles—such as the green ones that appear in myriad American cookbook recipes—are federally protected by the Endangered Species Act. About half of all turtle species, including freshwater turtles and tortoises, are threatened with extinction. According to Steen, we flat-out ate turtles into near nonexistence, an inevitable result of prizing eggproducing females for their tastier meat. “Turtle soup in the United States did not fade away simply because our palates changed,” he concluded. “Our taste for turtle soup exploded to unsustainable levels and caused the turtles to disappear first. They still haven’t come back.”

There were some who noticed the connection, however, almost twenty years before Steen’s article. When Scribner reissued Joy of Cooking in 1997 and

included the historic turtle soup recipes, activists were in an uproar. “Gather round the cookbook-burning bonfire, folks,” Heather McPherson wrote in the Orlando Sentinel then. “A bunch of turtle huggers are upset over the Joy of Cooking.” Times had certainly changed.

Nowhere has the attitude toward turtles changed more than on Jekyll. In 1950, three years after the State of Georgia purchased the once-exclusive island, the Jekyll Island State Park Authority Act limited development on the island to one-third of the land. In ensuing years, Jekyll would become a sanctuary not just for all manner of wildlife but for marine biologists, University of Georgia ecologists, and environmentally minded AmeriCorps volunteers. In 2007, the GSTC opened in a retrofitted power plant in the island’s historic district. Under the gaze of tourists, researchers study and document the turtle species present on the island, working to develop ways to aid in their protection. Visitors can join scientists on nighttime ride-alongs to see nesting loggerheads mid-crawl, watch veterinary procedures in action in the center’s operating room, or visit sick and injured sea turtles in the rehabilitation pavilion.

The GSTC hopes that through research, education, and basic intervention, they can help limit the destructive impact of habitat loss and other humandriven threats to turtle populations. For example, the Jekyll Island Causeway sees up to 400 turtle deaths each summer as female diamondback terrapins cross hightraffic areas to lay eggs. At the start of every nesting season, the GSTC places flashing “Turtle Crossing” signs and installs predator-proof nesting boxes; their work has saved some 2,500 terrapins over the last decade.

A January report from the science journal PLOS ONE says environmental efforts supported by the Endangered Species Act are having a positive impact on turtle populations. Steen, for his part, says success is when “you don’t need to worry about the conservation of a species blanking out due to anthropogenic threats.” Turtles aren’t well enough to be left alone yet, even if they’re off the dinner table. Well, mostly off the dinner table. Today, Pennsylvania allows limited hunting of its snapping

turtle, but only after the females have laid their eggs each season. In New Orleans, where diamondback terrapins can be hunted under specific regulations, turtle soup still appears at classic French-Creole restaurants like Uptown’s Upperline and Galatoire’s in the Quarter. It’s a sharp contrast to the mindset on Jekyll, where injured terrapins bask in an outdoor sanctuary and sure-handed guardians relocate turtle nests at risk of predation or tides.

Who can say what renders a species inconsumable?

Bluefin tuna and the Patagonian toothfish (also inaccurately known as Chilean sea bass) have been overfished for years, but that rarely stops seafood lovers from consuming them. If there’s one consistent trait of humankind throughout the centuries, it’s that we tend to put ourselves first. The proof is on our plates.

At the GSTC, Steen understands that most people define a species’ value in relation to what it does for us. An animal that spends much of its decades-long life submerged in water or hidden in swamps can be easily overlooked. But he wishes that wasn’t so. “We happen to be sharing this brief period of time with these fascinating creatures,” Steen said. “They’re the product of millions of years of evolution and we’re here at the same time.” That’s a marvel unto itself and good enough reason to lose your appetite.

Turtles aren‘t well enough to be left alone yet, even if they‘re off the dinner table.

HOW TO GET ALONG WITH

Alligators live in peaceful plenitude on Jekyll Island‚ and wildlife experts keep a closer tab on them than you might imagine. Still‚ some generous distance is good for everyone.

BY CANDICE DYER

BY CANDICE DYER

THE SCENE AT HORTON POND is eerily still. Even the insects are silent. Night herons roost like sentries in the trees‚ and on a platform in the water‚ a female alligator is holding an eyeball-to-eyeball staring contest with a turtle. The mood soon might be interrupted by a crunching sound as the gator devours the yellow-bellied slider‚ but for now‚ neither moves‚ prompting one visitor on the observation deck to wonder aloud‚ “Are these animals real or fake?”

Wildlife on Jekyll Island is decidedly real and unusually accessible‚ and its guardians urge visitors to adopt a policy of peaceful—and respectful—coexistence. “We don’t want people walking around in fear of alligators‚” says Ben Carswell‚ director of conservation for the Jekyll Island Authority. “At the same time we don’t want people harassing them‚ trying to catch them‚ or feeding them. Feeding them makes them unafraid of people and therefore all the more dangerous. We need to keep wildlife wild.”

Managing the relationship between gators and people is a critical mission for the Jekyll Island Authority’s wildlife team. While fatal alligator attacks are incredibly rare (there’s only been one ever in Georgia‚ in 2007), the potential for danger is always present—for both parties. “A fed gator is a dead gator‚” says wildlife manager Joseph Colbert. “If one becomes too aggressive we would have to put it down. We haven’t done that yet‚ but we keep it on the table as an option.”

The Jekyll Island Authority’s conservation department and Sea Turtle Center work to monitor the population and study the alligators’ movements‚ reproduction‚ and health. Initially‚ for five years‚ researchers surveyed thirty locations monthly with powerful spotlights that picked up the gators’ spooky red eye shine. As the project evolved, researchers mounted GPS tracking units on the animals, which collected valuable location data. They also notched their tails for identification purposes and took blood samples to gauge their health. The gators‚ who were not hurt during the process‚ were tracked for a year.

The GPS device collected location points every hour that could be downloaded remotely. “This revealed where we might have conflicts with people‚” says Gregory Skupien‚ who came to Jekyll as an AmeriCorps volunteer and stayed to write a master’s thesis on alligator conservation. Their findings? An estimated 110 alligators four feet or longer now call Jekyll home‚ though they have been known to venture as far away as St. Simons and Brunswick. The tracking

and identification marks enable wildlife professionals to see when an alligator shows up in an undesirable spot. “These are usually the unruly‚ energetic teenage gators who cause problems‚” says Carswell. For example‚ one might emerge onto a crowded beach‚ causing alarm. In that case‚ it is likely exhausted and trying to travel back to its preferred freshwater habitat; staffers can break out the treble hook and lend it a helping hand to get home. The system also reveals repeat offenders who are begging for food. About 18 percent of the calls to Jekyll’s wildlife hotline involve alligators‚ and half of those require a response from a park ranger or wildlife manager.

The GPS research ended in 2015‚ but the Jekyll conservation team continues to keep tabs on the animals through standard mark-and-recapture procedures. Though the population fluctuates‚ the gators tend to police themselves. “Large males and even siblings will take out other alligators‚ which keeps the population from exploding‚” says Colbert. “They don’t have predators to keep their populations in balance‚ and they won’t just allow thousands to grow up to compete with them‚ so they regulate themselves by being territorial and essentially fighting for space to survive.”

o look at one of these animals—Alligator mississippiensis—is to gaze deep into the primordial past. Gators have not evolved much since their ancestors emerged during the Cretaceous period 65 million years ago. The name “alligator” is believed to be an anglicized version of “el lagarto‚” or “the lizard” in Spanish‚ the language of early explorers and settlers in Florida.

Alligators are most active during mating season in the spring. “Around here‚ you can hear the males bellow‚” Carswell says. “It’s this low-volume rumble that’s almost ultrasonic‚

“WE NEED TO KEEP WILDLIFE WILD.”

“A FED GATOR IS A DEAD GATOR.”

vibrating on the surface of the water. Nesting season in July is an especially sensitive time when you take extra caution around alligators. Experts recommend giving them a berth of at least fifteen feet because the female is guarding a clutch of twenty-five to fifty eggs that are vulnerable to raccoons and possums. In fact‚ about a third of their nests end up destroyed by predators. During colder months‚ alligators burrow into berms to rest and conserve their energy. “They’re ectothermic‚ meaning they take heat from their surroundings‚” explains Jekyll park ranger Ray Emerson.

These are the type of facts visitors learn at Gatorology 101, an hourlong educational program through the Jekyll Island Authority’s conservation department. “During this hands-on experience‚ you will learn about the American alligator’s biology‚ behavior‚ history‚ and conservation while we demystify common misconceptions about these amazing reptiles‚” Emerson says. “We communicate the important message of: Don’t feed. Don’t approach. Don’t touch.”

Well, normally don’t touch. That rule does not apply to the center’s animal ambassadors. Jekyll has a special educational permit to house and show off alligators that have been raised in captivity. At the end of Gatorology‚ young Timmy‚ born at Orlando’s Gatorland zoo in 2016 and currently measuring about eighteen inches long‚ will pose with you and possibly smile for a selfie.

Jekyll’s wildlife experts know the importance of showing the softer side of these armored reptiles—of sharing‚ for example‚ that they are nurturing mothers who stay with their young for up to three years. Habitat destruction threatens all wildlife but especially gators. Because of their size—the largest Jekyll

gator found so far was eleven feet nine inches and weighed 600 pounds—they require more space to roam. They are often the first species lost when people and businesses move into their territory‚ causing a ripple effect down the food chain. As an apex predator‚ gators provide necessary checks and balances to populations of deer‚ raccoons‚ and foxes along with crabs‚ turtles‚ and terrapins. “We want visitors and residents to safely enjoy and learn from these amazing creatures for generations to come‚” Carswell says.

lligators are vital to the ecosystem‚ but they are inherently wild. A few extra precautions can keep you safe. On Jekyll‚ always control your pets and use a leash. “A dog is like ringing a dinner bell‚” Colbert says. Adds Carswell‚ “One of the good things about Jekyll is that almost no houses are next to ponds‚ so we don’t have too many pet issues.”

Golfers‚ take a mulligan rather than loiter around the edge of the water; alligators treat Jekyll’s twenty-four golf course ponds as their

personal lounges. Don’t be suckered in by tiny hatchlings—their protective mother is lurking nearby. And please keep your candy to yourself. “People are infatuated with feeding the gators marshmallows because they float on top of the water‚ or Skittles‚ but if we see that‚ we might get the Georgia State Patrol involved to shut it down‚” Colbert says with an emphatic nod. Feeding any wildlife is prohibited on Jekyll Island.

The best place to view alligators safely is Horton Pond‚ which furnishes them with their own sunbathing deck at a safe distance from people. “I’ve seen as many as three at a time congregated there‚” says Emerson.

Animal lovers should keep an eye out for Striker‚ Jekyll’s clever‚ gigantic celebrity gator. All of the locals have a story about Striker‚ who hangs out at the south end of the island and—according to legend—obeys the crosswalk signs at the roundabout. Like a tough guy at a bar‚ he has a big‚ noticeable scar from a boating accident. Presumably the boat got the worse end of that collision. The bacteria in pond scum helped his wound heal‚ so he keeps on trucking.

“Our mission is to preserve‚ promote‚ and educate about the rich diversity of species here‚“ says Emerson. “If we can get one person to respect and enjoy alligators properly‚ we’ve done our job.”

PLACE TIME &

The reimagined Museum of Jekyll Island offers a mosaic of artifacts across human and natural history

BY JOSH GREEN / PHOTOGRAPHY BY BRIAN AUSTIN LEE

BY JOSH GREEN / PHOTOGRAPHY BY BRIAN AUSTIN LEE

one breezy december afternoon at the eastern edge of Jekyll Island’s historic district, an unassuming white building that could pass for a country barn was abuzz with hammer pings and the shouts of construction crews. The workers had gutted the surprisingly airy, 9,000-square-foot interior to its inimitable bones. And if the wooden walls, towering fireplaces, and original double-hung windows could talk, they might recall: being built as the Jekyll Island Club Stables in 1897 for workhorses (and later automobiles) belonging to the likes of Joseph Pulitzer and the Rockefellers; serving as an inglorious storage facility for maintenance equipment and then a hardware store; and finally becoming a museum without air-conditioning or heat in the 1980s. That last incarnation had a paddock

(with pervasive equine odors) and a boxy theater in the middle that obliterated the space’s charms. Thanks to a $3.1 million renovation, the future of Mosaic, the Jekyll Island Museum, looks decidedly brighter. The goal of the project was to modernize the museum in function and flow while highlighting its architectural character, luring everyone from tykes to older history buffs and providing interactive, educational experiences that cover Jekyll’s history. Up to 50,000 annual visitors are expected to use the museum as a gateway to the historic district—and to a greater understanding of Jekyll’s distinctiveness. “It really is an excellent example of the kind of revitalization that’s been taking place on Jekyll for about ten years,” said Bruce Piatek, the Jekyll Island

Authority’s director of historical resources. “It’s the last piece, the last major redo in the historic district.”

Fundraising efforts for the public-private partnership, driven by the Jekyll Island Foundation, began in 2014. Joining more than 260 corporate, foundation, and individual donors, the Jekyll Island Authority contributed 1.1 million, while the Atlantabased Robert W. Woodruff Foundation donated another $750,000. The design will reflect what the name Mosaic signifies: various facets of Jekyll’s story—nature, history, ecology—compiled as a single narrative under one roof. Climate control means hundreds of artifacts can now be displayed at once.

STATE ERA Refurbished Studebaker

Among the first treasures to greet Mosaic guests will be a restored four-door 1947 Studebaker—the type of car a family might have used to cruise the new causeway into Jekyll in the 1950s. Accompanied by a vintage Jekyll postcard expanded into a mural, the vehicle will serve as an interactive photo op; guests can sit inside and enjoy period music and a couple of old radio ads, including one celebrating the causeway’s grand opening.

“We’re trying to put you in that setting,” said Piatek. “Initially, we were going to cut the poor [car] in half, but it was so pretty, we couldn’t.”

Inside, an array of sculpted migratory birds will dangle overhead as visitors work back through Jekyll history, beginning with Native American habitation. A circular playscape for kids will expand into the lobby and offer an oversized eagle’s nest and crawl-through marsh exhibit. Other pieces will include a Red Bug beach cruiser (see page 12), a 1740s reproduction sailboat, a dugout Native American canoe made of Jekyll pine, and a replica hull of the Wanderer one of America’s last documented slave ships, which landed on the island—that allows visitors to crawl inside and experience the inhumane conditions. The museum isn’t meant to stand in for real experiences—such as spotting actual bald eagles— but rather serve as a starter kit for exploring the island’s rich history and natural beauty.

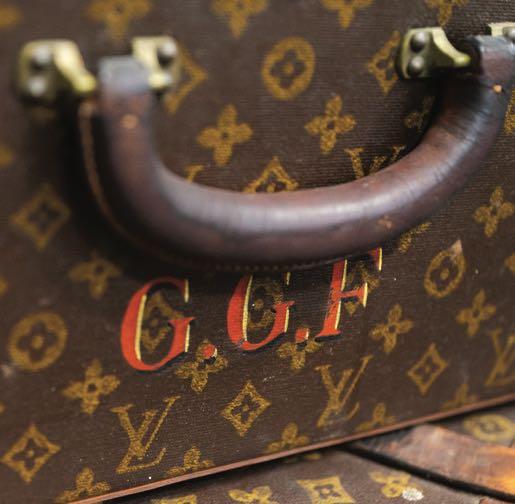

CLUB ERA Louis Vuitton luggage

Harking back to a time when one-sixth of the world’s wealth was represented on Jekyll each winter, this collection of leatherwrapped Louis Vuitton luggage (two trunks and a smaller valise) was as fashionable in name in the early 1900s as today. The pieces belonged to a Club family, the Jenningses of Standard Oil prosperity. Keep an eye peeled for old shipping labels still stuck to the sides.

PLANTATION ERA

DuBignon signet ring

This heirloom signet ring from the DuBignon family—French émigrés who owned Jekyll Island for about a century until the 1890s—was handed down through generations and donated to the museum. Made of flecked stone and gold, the ring depicts the couronnes des comtes crown, wheat, and laurel leaves representing victory, triumph, success, fame, prosperity, and peace. “We have very few artifacts from that time period, and it’s directly connected to the family,” said museum curator Andrea Marroquin. “It’s a neat piece.”

COLONIAL/ EUROPEAN ERA

Major Horton’s uniform

Authentic in colors and wool material, which was believed to whisk away sweat in sultry climates, this replica uniform mirrors what would have been worn by Major William Horton, Jekyll’s first English resident, at the oldest Colonial-era structure on the island, the 1743 Horton House. Horton rose from civilian ranks to second-in-command behind General James Oglethorpe, founder of the Georgia colony, and the mock regalia reflects that status.

NATIVE AMERICAN ERA

“Hidden in the Midden”

Anchoring the exhibit farthest from the entrance are re-creations of a Native American midden (refuse pile composed largely of oyster shells) and a thatched-roof cottage with mud and clay walls. Showing deposits by Archaic people from 4,500 years ago as well as ancestors of modern-day Creek tribes and other Native Americans, the three-dimensional midden provides an archaeologist’s perspective of deep sand, armadillo tunnels, even litter. A key message will be sustainability and stewardship, which the Rockefellers didn’t know to practice when they removed part of a shell midden in the 1910s to improve the marsh views at Indian Mound Cottage. Combined with a variety of artifacts, the installations will relay the story of bygone Jekyll residents who left no written record.

Jekyll Island has long been a vacation destination. Wealthy snowbirds flocked to its natural grandeur at the turn of the twentieth century. When the state took over the island in 1947, the goal was to lure the masses. It didn’t take long to realize this would take more than just sand, surf, and sunshine. On its way to becoming the serene refuge for families and sea turtles it is today, Jekyll saw several parks and amusement rides come and go. And while these attractions ultimately were razed, replaced, and largely forgotten, longtime island guests still have fond and funny memories—fading echoes of a time when Jekyll was still searching for its modern identity.

an amusement park . . . for turtles

In April 1956, Georgia businessman Harvey Smith built Peppermint Land, Jekyll’s first amusement park. Located on the ocean side of the island, just south of where Tortuga Jack’s currently stands, the red-andwhite-striped theme park featured a small Ferris wheel, a low-riding roller coaster, a miniature train, and go-karts. That last element was a big draw for local boys like Skip Adamson, who first moved to Jekyll in 1963, at age twelve. “At that age, being able to drive something with an engine was fun,” says Adamson. “They went pretty fast.”

The oval track of asphalt was lined with wooden rails to keep wayward speed demons on course. Each run of several laps cost 10 cents. “My dad owned the laundromat and he always collected the coins,” says Adamson. “One time I ‘borrowed’ a whole roll of dimes. I got in trouble. I’ve regretted it ever since.” The object of Adamson’s shame was shuttered and torn down in 1965, when Smith failed to secure a favorable lease with the state.

According to Adamson and other residents at the time, few people lamented the closing of the park, which had fallen into disrepair. But one surprising group of visitors surely missed it. In 1962, the park had to shut down several rides when a bale of baby loggerhead turtles squatted on the train tracks. It was August, hatching season, and the hatchlings were drawn to the park’s bright lights.

the ride that went downhill fast

Not long after Peppermint Land closed, the same beach-view area just across the road from the miniature golf course was host to a thrill ride that was way too swift for turtles—and many humans.

In the 1960s and 1970s, gunny-sack slides were all the rage. Riders would climb to the top of a steep, multilane slide, slip into or onto a burlap bag, and

send themselves screaming straight down. Jekyll’s Super Slide was several stories tall and made of metal. “It was silver and blue—an ugly thing,” says Lloyd Douglas, who moved to Jekyll in the mid-1950s and worked for the Jekyll Island Authority for forty years.

Adding to the eyesore were giant overhead lights that allowed sliders to embrace gravity late into the summer nights. “The lights were so huge,” says John Neidhardt, who has lived on the island since 1970, “you could probably see them from space.”

However, the Super Slide’s ultimate demise was left:

due less to being hard on the eyes than being hard on the body. The salt spray from the ocean made the thing even more slippery, and the dividers between the eight lanes were short and less than effective. Sliders rocketing some fifty feet downward side by side would almost always bump into one another before the first hump, which often slammed their backs and heads into the unforgiving surface. It was quite a cost for a joy ride that lasted just a second or two. “Several people got hurt,” says Adamson. “I think they closed it down pretty soon after that. It was crazy even for back then. It was dangerous—but it was fun.”

the only indoor pool around

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, many people on Jekyll believed a convention center would help bring in visitors. But the state legislature, thinking the island wasn’t quite ready for that, wouldn’t appropriate the funds. The government did, however, relinquish the money for a recreation center.

In 1961, construction of the Aquarama was completed on the southeastern side of the island, not far from where the current convention center now stands. The period Art Deco exterior, punctuated by its iconic triangular glass entry, covered what was billed as an Olympic-sized swimming pool—although locals knew that the dimensions came up a foot or two shy of the required fifty feet due to a shortfall in funding. Nevertheless, the pool was the first heated indoor pool in the region, and it attracted swimmers from all around the state. There were one-meter and three-meter diving boards at one end for the more adventurous, along with a kiddie pool for

little waders. At the time, more families lived on the island, with enough kids to form a local swim team—which at one time included Neidhardt.

“Having been in such a big room with that triangular roof, I can still smell the chlorine,” says Neidhardt. “It was heated so you could swim yearround. There was always a loud echo of people talking loudly bouncing off the concrete beams.”

The din of splashing and shouting wasn’t the only thing that grew beneath the steamy Aquarama ceiling. “With it being closed in, the place didn’t get a lot of sun,” says Douglas. “Algae grew pretty fast on the concrete. You’d have to scrub it with [cleaner]. The Aquarama was quite a chore to maintain.”

In the end, perhaps cleaning and heating and maintaining the huge facility became too much of a chore. Summer Waves opened in 1987, providing an alternative water-play destination for locals and tourists. In 1992, after three decades of service, the Aquarama was closed. It was torn down three years later.

what the heck is ski rixen?

Any beach town worth its weight in sand is going to offer water sports. Jekyll’s unspoiled beaches have always hosted swimmers, boaters, boogie-boarders, and the occasional surfer. But the ocean tends to be a bit choppy for water-skiing.

In the early 1980s, the solution was Ski Rixen, a European system of electrically powered metal cables that pull skiers. A twenty-three-acre pond was dug on the southwestern side of island, right behind where the 4-H Tidelands Nature Center now sits, adjacent to Summer Waves. Cables ran in a rectangle across the pond, about thirty feet above the water. Every few feet a skier, perched atop two skis or a wakeboard, would be thrown a rope that was hooked to a carrier and pulled one way or the other across the pond at speeds upward of sixteen miles per hour. “It was a lot harder to do than most people thought,” says Adamson. “It was slinging people off all the time. A few people I knew got pretty accomplished at it, but not many. I never tried it myself. I knew I’d break something.”

“It was very difficult,” says Neidhardt. “But once you learned it, it was fun. The cable was always moving; it never stopped. The key was to learn how to hold on without flying through the air.”

Of course, any Jekyll resident will warn that where there is a relatively calm body of water, there are uninvited guests. “Occasionally you’d hear about an alligator in the lake,” says Neidhardt. “But they never had an incident. I’d never seen one—until one was there.”

The attraction closed due to gator safety concerns after only a few years. Today there aren’t any skiers or cables on the pond, but it’s a popular fishing spot.

In the 1960s, the Jekyll Island Clubhouse signage had a distinctly retro look. After sitting out of commission for many years, the sign— including its original bulbs—shines on in Mosaic, the Jekyll Island Museum.

NATURE’S REVENGE

Wet footprints splash up the concrete stairs before you. As you climb‚ you notice the peaceful creek below‚ but excited screams from above pull you back to your fate. Within minutes you are at the slide’s summit‚ forty feet above Summer Waves Water Park. Down is the only way to go‚ but there are two ways to get there. Left to the blue Tornado or right to the red Hurricane? The lifeguards can’t seem to agree which is faster. You choose red‚ grip the metal crossbar‚ nod at the stranger on the other slide‚ and at the lifeguard’s command sling yourself into the open tube. Lying flat and compact‚ you cut the corners as the air and chlorine blast against your face. Seconds later‚ you reach the pool at the bottom and sit up to see your opponent arrived at the same time. You and your new friend race to the stairs to make another ascent. —tony rehagen

PATHS

find your way back...

...to a new tradition.

Year after year, their footprints appear on our sandy shores. They don’t return for the expected. They don’t stay for the same routine. They want to leave their prints on natural beaches, wander trails winding beneath wild canopies. Join them in the adventure. Find your way back. jekyllisland.com