AGE

THE

Winter 5780/2019 Vol. 80, No. 2

IN THE DAF DIGITAL

NEW! MASTER’S IN SPECIAL EDUCATION

WURZWEILER SCHOOL OF SOCIAL WORK

Gain hands-on experience teaching children with disabilities.

Grow as an educator with personalized support from your instructors.

More at: go.yu.edu/wurzweiler/special-education BUILDING TOMORROW, TODAY Learn the skills you need to educate every child.

Master inclusive classroom practices and curricula development. Learn

Winter 2019/5780 | Vol.

PROFILE

Searching for Heather Dean

By Toby Klein Greenwald

COVER STORY: The Daf in the Digital Age Introduction by Gil Student

Behind the Daf

Discussing Daf Yomi with some of the most distinguished maggidei shiur

Interviews by Dovid Bashevkin and Sholom Licht

Up Close with Dr. Henry Abramson Interview by Sholom Licht

In Teir Own Words— How Daf Yomi has changed lives

Tweeting the Talmud

By Binyamin Ehrenkranz

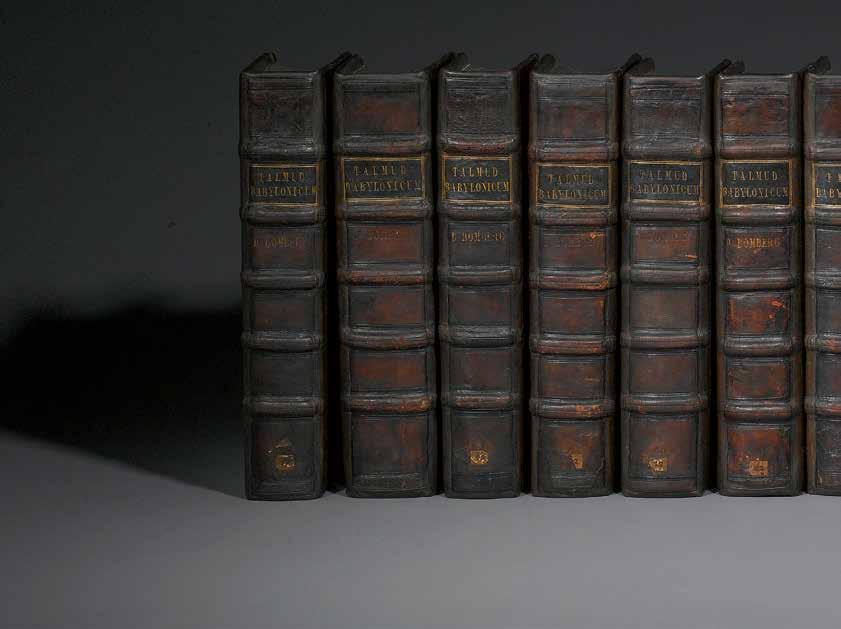

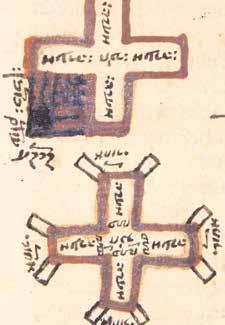

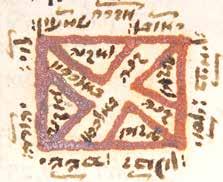

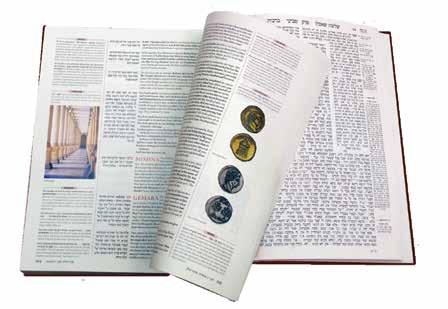

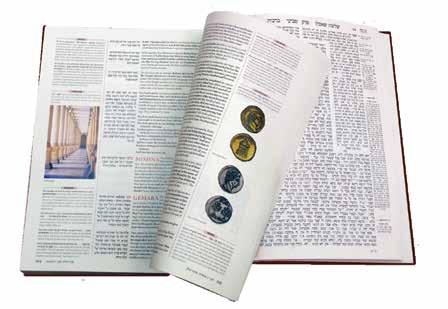

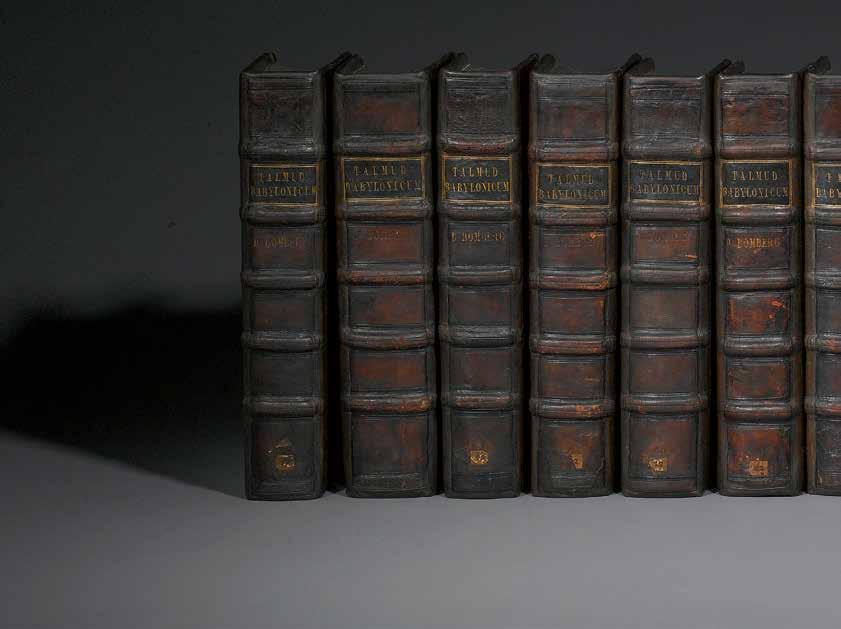

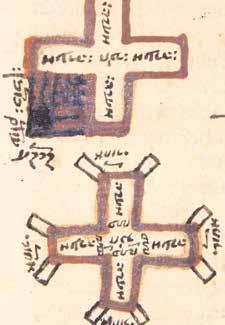

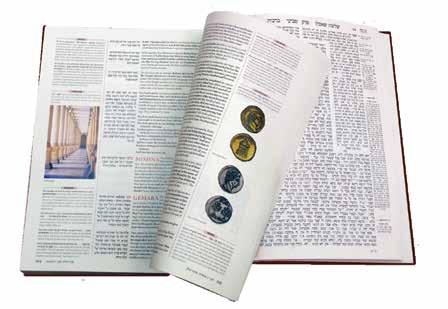

Printing the Shas

Commemorating the 500th anniversary of the printing of the Bomberg Talmud

By Michelle

Chesner

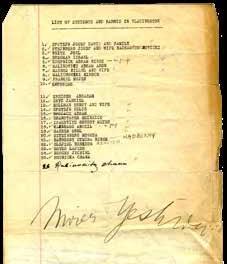

HOLOCAUST

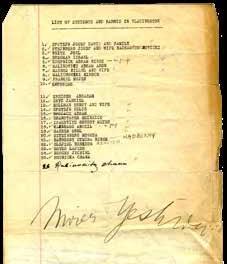

A Discovery Sheds Light on Rescue

Eforts During the Holocaust: Letters from venerable gedolim published for the frst time

By Susie Garber

Te Kestenbaum Rescue

Eforts: An Analysis

By R. Licht

INSPIRATION

Chanukah: I See the Light

By Hillel Goldberg

SPECIAL SECTION:

Death and Dying: the Jewish View

Meet Rochel Berman

A volunteer for the chevra kadisha, Berman has spent decades engaging in the ultimate act of chesed. As told to Leah R. Lightman

REVIEW ESSAY

Hope, Not Fear: Changing the Way We View Death

By Rabbi Benjamin Blech

Reviewed by Elizabeth Kratz

DEPARTMENTS

LETTERS

PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE Can We Survive Community Harmony?

By Mark (Moishe) Bane

FROM THE DESK OF ALLEN I. FAGIN

Te Intolerance of Tolerance

CHAIRMAN’S MESSAGE

By Gerald

M. Schreck

JUST BETWEEN US

Should You Put Your Kid on a Diet? Ten Points to Tink About By Dina Cohen and Rachel Tuchman

LEGAL-EASE

What’s the Truth About . . . Jews Counting Years Starting From Creation?

By Ari Z. Zivotofsky

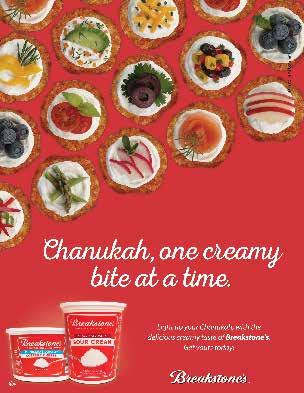

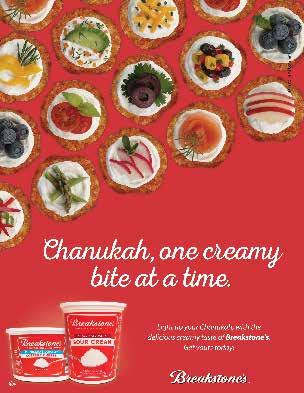

THE CHEF’S TABLE Say “Cheese!”

By Naomi Ross

INSIDE THE OU

Compiled by Sara Olson

INSIDE PHILANTHROPY

Compiled by Marcia P. Neeley

BOOKS

A Father’s Story: My Fight for Justice Against Iranian Terror

By Stephen M. Flatow

Reviewed by Dov Fischer

Te New American Judaism: How Jews Practice Teir Religion Today

By Jack Wertheimer

Reviewed by Yitzchok Adlerstein

LASTING IMPRESSIONS

A Family Treasure

By Sarah Rindner

Cover: Aliza Ungar

Jewish Action seeks to provide a forum for a diversity of legitimate opinions within the spectrum of Orthodox Judaism. Therefore, opinions expressed do not necessarily refect the policy or opinion of the Orthodox Union.

1 Winter 5780/2019 JEWISH ACTION Jewish Action is published by the Orthodox Union • 11 Broadway, New York, NY 10004 212.563.4000. Printed Quarterly—Winter, Spring, Summer, Fall, plus Special Passover issue. ISSN No. 0447-7049. Subscription: $16.00 per year; Canadian, $20.00; Overseas, $60.00. Periodical's postage paid at New York, NY, and additional offces. POSTMASTER: Send address changes to Jewish Action, 11 Broadway, New York, NY 10004. INSIDE 23 22 1 6 76 78 02 06 10 14 80 92 97 105 112 115 120 88 30

38

72 80 97 16 92 72

42

46

FEATURES

52 70

2 76

80, No.

3 Winter 5780/2019 JEWISH ACTION Discover Your Future at Touro’s Lander College of Arts and Sciences in Flatbush Touro is an equal opportunity institution. For Touro’s complete Non-Discrimination Statement, visit www.touro.edu For information contact Rabbi Justin Gershon 718.252.7800 ext. 59299 or 59399 or admissions.lander@touro.edu 1602 Avenue J, Brooklyn SPRING SEMESTER Starts Jan. 30 APPLY NOW! Outstanding Record of Admissions to Graduate & Professional Schools Accelerated Accounting CPA Program Financial Aid & Academic Scholarships for Qualified Students Honors Options in Health Sciences & Computer Science Career Placement with 2 Annual Job Fairs Separate Schools for Men and Women

anyone who wished to fll his morning hours with Torah study. Afer establishing the fagship branch of Agra D’Pirka at Knesses Bais Avigdor in Flatbush, and witnessing its remarkable success, he opened Agra D’Pirka branches in other New York communities including Boro Park, Kew Gardens Hills, Williamsburg and Monsey. Branches were also launched in Lakewood, New Jersey; Baltimore, Maryland; and Miami Beach, Florida, with plans to open new branches in West Palm Beach, Florida, and Los Angeles, California.

Any treatment of this subject should include Agra D’Pirka.

Chaim Fuhrer Administrator

Agra D’Pirka Brooklyn, New York

BURYING A FETUS

We applaud you for publishing Rabbi Elisha Friedman’s article “Burying a Fetus and a Dream” (fall 2019). Tis moving article is a further indication that the Orthodox world has fnally begun to acknowledge the pain and difculty associated with pregnancy loss, and that it afects men as well as women.

But we found one aspect of the article troubling. Rabbi Friedman writes, “I marveled, because Jewish tradition has given us a wise, if painful, framework to process miscarriage. Standing at that anonymous grave all those years later, I knew something I could never have imagined back when I experienced my own loss: that despite the searing pain of that miscarriage, it was wise that I had been encouraged not to name my child and bury her, but to move on.”

Based on our two experiences with second-trimester pregnancy loss, we have drawn diferent lessons. Mourning for such a loss is not incompatible with “moving on.” On the contrary, having time and space for healthy mourning can help a couple become ready for another attempt at conception, and assist them in caring for any children they already have. Additionally, openness about the loss allows for other people to get involved and provide support.

With our frst such experience, we were too shocked to think constructively about what would be best for us. We simply let the doctors do what they needed to do and mourned by ourselves. Tese turned out to be poor decisions.

Unfortunately, we faced the same situation a few years later. We knew this time to reach out for help. Sara delivered the baby and was able to hold him. Our rabbi did not advise us to refrain from naming our child, and we did give him a name. Tis act gave him an identity as a human being and as a potential life. Te burial was handled by the chevra kadisha, but Sara was there when it took place, accompanied by a friend. (Alan was not able to go, as he is a kohen).

We respect Rabbi Friedman’s perspective and his means of coping. However, we would caution readers that his is by no means the only Torah-true pathway to deal with such a loss.

Rabbi Friedman’s moving and valuable contribution will surely be comforting to many fellow parents who sufered a perinatal bereavement. However, it should not leave the misimpression that halachic tradition requires leaving the parents out of the process of naming and burying the nefel [a fetus that dies in the womb or is born dead].

For example, Rabbi Aharon Lichtenstein, zt”l, strongly objected to a chevra kadisha preventing parents from being present at the burial of their child.1 In 2014, a joint directive of Israel’s Ministry of Health, the National Insurance Institute and the Ministry of Religious Services2 required the chevra kadisha to ofer the parents the opportunity to be at the burial [of a nefel]. Te United Synagogue, a union of Orthodox shuls in England, created a “Guide for the Jewish Parent on Miscarriages, Stillbirths & Neonatal Deaths,”3 which notes:

“Some parents fnd it too difcult to be present for the burial whereas others derive a certain sense of comfort from being there. Both approaches comply with Halachah and every family should do what they feel is best for them. Some close relatives or friends might also attend but it is not usual to have a large gathering of people at such an occasion” (p. 6).

Surely the bereaved parents’ rabbi, who knows their needs, should be the one counseling them on issues such as whether they or the chevra kadisha choose a name for the nefel and who should attend the burial.

Parents bereaved by a perinatal death react in many of the same ways as do those who sufer the loss of an older child, but society responds diferently, especially in the traditional Jewish community. Tere is no communitysupported funeral and no shivah where people could come to express their sympathy and encouragement. As a result, there may well be disenfranchised grief. Indeed, lack of social support is among the predictors of the development of complicated grief afer such loss.4

True, many bereaved parents would prefer dealing with their loss in private. But many might well appreciate social support at that dark moment. Public recognition and expression can be as simple as arranging for Maariv at the home of the bereaved or learning a mishnah or two followed by Kaddish deRabbanan.5 Bereaved parents need not take of their shoes or sit on a low stool to be comforted by caring friends and family who stay aferwards. Keriah is not required for the death of a nefel, but the berachah is independent of keriah and may be said b’Shem u’Malchut for this death, as the parents are indeed saddened by the news.6 Te parents can also be reminded that it would be appropriate for them to attend Yizkor each holiday if they wish.

We should be aware of the varied opportunities available to comfort those bereaved by such a loss.

Notes

1. Rabbi Avraham Stav, Kachalom Yauf 74 (Jerusalem, 2010), 39. Te volume discusses halachic and hashkafc issues regarding this bereavement.

2. Te details are available at https://www.health.gov.il/ English/Topics/Pregnancy/Pages/Loss_of_baby.aspx.

3. See https://www.theus.org.uk/sites/default/ f les/still%20birth%20singles.pdf.

4 JEWISH ACTION Winter 5780/2019

Alan and Dr. Sara Goldman University Heights, Ohio

4. A. Kersting and B. Wagner, “Complicated grief a fer perinatal loss,” Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience 14, no. 2 (June 2012): 187-94.

5. On the general issue of women saying Kaddish, see my review of “Kaddish, Women’s Voices,” Hakirah 17 (summer 2014): 165-178, http://www.hakirah.org/Vol17Wolowelsky.pdf.

6. Rabbi Aaron Felder, Yesodei Smachos (New York, 1976), 2, n. 12, quoting Rabbi Moshe Feinstein, zt”l

Joel B. Wolowelsky Brooklyn,

New York

Editor’s Note: Dr. Joel Wolowelsky is the author of To Mourn a Child: Jewish Responses to Neonatal and Childhood Death (Brooklyn, 2013).

NechamaComfort is an organization supporting families sufering miscarriage, stillbirth and early infant death. We know the pain Rabbi Friedman so eloquently describes.

At NechamaComfort, we have found that couples can be helped tremendously by immediate support at the time of loss and by being ofered choices. If they want to, they can pick a name for their baby that is meaningful to them, have organized grieving time and know where their baby is buried so they can put up a matzevah (stone marker) at the grave and stand and cry for their terrible loss. Halachah allows for all of these things.

It is crucial to train rabbis, doctors and hospital staf so that they know how to be supportive and helpful. Communities can also be educated on how to embrace a sufering family and allow space for both the joys and the sorrows of building a family. NechamaComfort provides professional training and community awareness programs to make sure no one is lef to sufer alone.

Te goal is not to “get over it” but to “move through” the sufering and to fnd a meaningful way to incorporate the loss into the story of your life. Whether the loss happened yesterday or years ago, it is never too late to be supported by those who understand what you are going through.

Reva Judas, founder and director, NechamaComfort

Sharon Barth

Ellen Krischer

Esther Levie

Teaneck, New Jersey

Editor’s Note: OU Executive Vice President, Emeritus, Rabbi Dr. Tzvi Hersh Weinreb recalls being told by senior rabbis in Baltimore that the custom in some communities in pre-Holocaust Europe was to give stillborn children uncommon names, such as Abaye for males and Zilpah for females.

2 in 3 Jewish people are carriers for a devastating genetic disease

Jewish genetic diseases are preventable through carrier screening

Genetics professionals recommend expanded testing panels that include many more diseases than Dor Yeshorim offers for anyone planning to start or add to their families

5 Winter 5780/2019 JEWISH ACTION

TO SEND A LETTER to the EDITOR, email ja@ou.org Ensure a bright and healthy future for your family

JScreen has transformed access to genetic testing:

Did you know...

404.778.8640 INFO@JSCREEN.ORG Learn more and request a kit at JScreen.org

Online, at-home, available nationwide Screening done on saliva Highly subsidized Genetic counseling by phone to discuss results

CAN WE SURVIVE COMMUNITY HARMONY?

By Mark (Moishe) Bane

Confict within the Jewish community is ofen due to challenges to the religious essence of Judaism and to the binding nature of Torah and rabbinic authority. But history is also replete with instances of discord within the Orthodox community itself, despite all factions sharing a common commitment to Torah observance and values. Sometimes such Orthodox divisiveness is caused by petty jealousies, greed and insecurities. But other times, battles within the Orthodox world rage over truly substantive ideological issues, albeit within the contours of Torah and the mesorah

Although there is currently no shortage of disparate, ofen conficting, religious attitudes and practices within the American Orthodox community, it seems that the friction between various sectors is less intense nowadays than in earlier decades. Signifcant ideological clashes within the American Orthodox community are increasingly rare; even when disagreements do arise, the volume of the battles seems to be fairly mild compared to some of the more explosive ideological conficts of the past. Each sector appears content to leave others to follow their own path in avodas Hashem, notwithstanding how misguided the path may be viewed.

Is Communal Tranquility Attributable to Religious Apathy?

It would be nice to believe that the current relative harmony among American Orthodoxy is the product of increased righteousness and maturity. Or perhaps American Orthodoxy is circling the wagons in response to mounting anti-Semitism and to secular society’s assault on religious observance and values. A more frightening possibility is that the tranquility is a refection of religious apathy. Afer all, vigorous religious confict is ofen an expression of authentic ideological passion. People tend to engage in ideological battles only when they feel the cause deeply and personally.

Some might even argue that religious ideological battles have a positive impact. As long as conducted

respectfully and appropriately, religious confrontation is not only an expression of true passion but also tends to enhance the participants’ religious commitment and growth. Certainly, confict motivated by authentic religious commitment is less troubling than the calm born of ideological indiference. When children disagree and bitterly fght about how their elderly parents should be cared for, the parents are surely pained. But such familial discord is certainly preferable to indiferent children, readily ceding to their siblings’ views while shrugging their shoulders and walking away mumbling “whatever.” Fortunately, it cannot be credibly suggested that American Orthodox Jewry is religiously indiferent. To the contrary, the commitment to religious observance and values of the community, as a whole, is truly admirable.

• Orthodoxy in general continues to thrive in Torah study and commitment to Torah values. Moreover, increased Torah knowledge and understanding are engendering an enhanced and increasingly attentive approach to mitzvah observance.

• Te frum community’s deep commitment to living a Torah lifestyle is clearly evident when considering the economic demands, and resulting lifestyle sacrifces, entailed in raising an observant family.

• As a whole, the community has retained, if not enhanced, its emunah, its profound faith in God.

6 JEWISH ACTION Winter 5780/2019

PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE

Mark (Moishe) Bane is president of the OU and a senior partner and chairman of the Business Restructuring Department at the international law firm Ropes & Gray LLP.

Tis dedication is particularly stunning in light of the ongoing state of hester panim (the lack of explicit manifestations of God’s presence) that has been imposed since the destruction of the frst Beis Hamikdash (Temple). Tis hester panim has plagued the Jewish people through centuries of massacres, pogroms and expulsions, reaching a crescendo in the Holocaust. And yet we are ma’aminim bnei ma’aminim, devout believers, children of believers. Hardly the stuf of religious apathy. • Te Orthodox community has embraced holiness, manifest through its commitment to marriage, family and communal benevolence. Te community’s elevated holiness is all the more extraordinary in light of the incessant bombardment of society’s perspectives and priorities that are antithetical to Torah values, the infuence inherent to the integration of Orthodox Jewry into society’s social and commercial structure and the alluring temptations of materialism and immodesty pervasively accessible through technology. As a whole, the community is manifestly committed to Torah Judaism. Tus, it should be apparent that American Jewry’s relative lack of discord is not due to an absence of religious commitment and passion. How then can we understand American Orthodoxy’s relative internal tranquility? Tis conundrum is compounded when considering the ofen bombastic conficts raging within the Israeli Orthodox community.

Admittedly, the ideological strife in Israel can be attributed to factors and infuences not found in America. Tese include the IDF draf and its religious exemptions, the Ofce of the

Chief Rabbinate and the multiple and intensely socially segregated Orthodox educational school systems. And of course there is the ubiquitous role of Israeli politics and the resulting entanglement of Israeli Orthodoxy with religious political parties. Nevertheless, the absence of these factors in America cannot alone explain the diminished American Orthodox infghting.

Individualism or Collectivism

A signifcant distinction among social cultures is how they balance individualism and collectivism. Individualism emphasizes the primacy of each human being, placing the interests of the individual ahead of those of the community. Collectivism, by contrast, regards the aggregation of people into a community as the grander expression of humanity, prioritizing the interests of the collective ahead of those of any individual.

Te dichotomy between individualism and collectivism extends beyond public policy and philosophy to inform how people perceive their own identity and purpose. Terefore, it infuences life choices. Is their primary identity dictated by their personal distinctiveness or by the society or community with which they associate? Are their goals and aspirations focused on personal achievements and independent expression, or on the successes and accomplishments of the group?

In any society, healthy people’s psyches and aspirations will include aspects of both their individual and communal identities. Te allocation between the two, however, is typically infuenced by the culture of the society in which they dwell.

Rather than viewing individualism and collectivism as contradictory or

competitive, Judaism recognizes each as representing distinct dimensions of Torah values, each being integral to a healthy and productive Jewish life.

For example, halachah addresses when one’s personal interests must take priority, and when deference to communal concerns is advisable. Certain mitzvos can be observed as an individual, while others can be performed only as a community. In the Beis Hamikdash, may it soon be rebuilt, most of the daily and holiday services were performed on behalf of the collective community, but there were also contributions and services due from each individual.

In mystical terms as well, a Jew’s relationship to God must be developed on both planes. Each Jewish soul is both independent and interdependent, and thus, one Jew’s spiritual growth afects the entirety of the Jewish people. On Yom Kippur we repeatedly chant Vidui (the confession prayer) for our individual failings, but in each instance, we then chant it a second time collectively, for our community’s defciencies. Individualism and collectivism should not subsume or override the other.

American culture recognizes a role for, and the value of community, but generally weighs heavily in favor of the individual. American society’s emphasis on individualism is refected in its focus on personal aspirations and wants. Self-actualization is a linchpin of American culture, which encourages people to be who they are, feel as they feel and live the life they experience as being most authentic. In fact, restricting one’s self-expression or personal aspirations to accommodate communal sensitivities or needs is regarded as weak and pointless.

Unbridled individualism ofen results in attitudes that are antithetical to Torah, such as narcissism and selfshness. It foments boundless expectations and demands for individual entitlements, encompassing the widest of spectrums, from how to live to when to die.

Western culture increasingly seeks to diminish the role of God and religion in society and in private life. Perhaps individualism is encouraged because

7 Winter 5780/2019 JEWISH ACTION

Each Jewish soul is both independent and interdependent, and thus, one Jew’s spiritual growth affects the entirety of the Jewish people.

it not only promotes individual needs above the will of the collective, but also creates a mindset that elevates individual needs above the will of God.

To be sure, individualism as an ideology has positive efects. It has resulted in exceptional levels of creativity, entrepreneurship and personal achievement. Individualism trains one to look past the blur of humanity, focusing on the worth of the individual. Perhaps this social outlook is responsible for the American dedication to addressing the needs of the disadvantaged, as well as those with special needs and disabilities. And, perhaps in a bizarre sort of way, the American culture of individualism may also be responsible for the increased harmony among segments of American Orthodoxy.

Is Communal Tranquility Attributable to Individualism?

Te Orthodox community comprises various communal segments forming an amalgamated whole. Are these segments individual pieces that stand on their own but happen to create a collection, or is each communal segment intrinsically interwoven, attaining its true signifcance by joining with other segments to create the holistic fabric of Torah Judaism?

Tose with a collectivist mindset view the Orthodox world as a composite, with each sub-community’s current state and future fate afected by every other segment. In this view, each group is understandably troubled, if not ofended, by another’s attempt to radically “innovate” or to depart from past practices or halachic standards. Te deeper the provocation, the more intense the response. Tis indignation stems from a deep sense of communal achdus and cohesiveness, a recognition of our mystical connectedness that makes us all both spiritually dependent upon, and responsible for, one another.

Tose with an individualistic mindset, by contrast, view each sub-community as independent, as an island. In this view, sub-communities care little about one another since there’s no appreciation of an interconnectivity or interdependence between the groups and no sense of one group having an efect on another. No segment need be perturbed by the

practices and religious views of another. In fact, they feel it is inappropriate to be judgmental of others since each group is on their own, unafected by the others and entitled to do as they please. When one sub-community, for example, adopts an unprecedented or deviant practice or religious view, others are likely to merely shrug their shoulders, move on and mumble “whatever.”

Can Orthodox Jewry Survive Internal Tranquility?

Tus, we must ask: Does the lack of strife among American Orthodoxy refect brotherly love and respect or does it signify a sense of alienation and detachment? Indeed, sometimes the absence of communal tension may strike us as attractive, but should not be a cause for celebration since it reveals simple indiference.

Te Jewish community cannot survive a “harmony” that is the byproduct of apathy and detachment among fellow Jews. If we lose sight of our spiritual interdependence and interconnectivity, we forfeit one of the seminal foundations of Judaism.

Midrash Rabba (Parashas Emor 30:12) describes four categories of Jews: the pious scholar, the non-pious scholar, the non-scholarly pious person and the Jew who is neither pious nor a scholar. Tis disparity and inconsistency raises

questions regarding the viability of the Jewish people. In His eagerness to preserve our special nation, God advises that as an antidote to our vulnerability, each sector of the Jewish people should bind itself to the other three and by doing so, each will redeem the other. Trough this bond, the Shechinah, God’s Holy presence, will pervade His people. Internal strife within the Orthodox world is distressing and painful, and yes, it is wonderful if such conficts have generally subsided. But we are sufering a fate far more devastating than internal confict if the absence of discord is, in fact, due to indiference, inertia and the failure to comprehend our interdependence. Our survival as a vibrant people, and our relationship with God, is dependent on our recognition of how intertwined our fate is and how interconnected we are as a people. Admittedly, this recognition may lead to confict. But if we also recognize that our connection to the Almighty is dependent on our preventing the inevitable ideological strife from compromising our bond with our fellow Jews, we can surely engage in such battle while preserving our respect and love for one another. Klal Yisrael can thereby survive, if not fourish, within the tensions that ensue when brothers and sisters truly care about one another.

8 JEWISH ACTION Winter 5780/2019

WANT TO HEAR FROM YOU!

If we lose sight of our spiritual interdependence and interconnectivity, we forfeit one of the seminal foundations of Judaism.

WE

To send a letter to Jewish Action, e-mail ja@ou.org.

The INTOLERANCE of TOLERANCE

Ihave never before, in the pages of this magazine, directly addressed the resurgence of blatant anti-Semitism both here in the US and abroad. I’m not certain why. Perhaps because the subject is simply too painful. Perhaps because the search for solutions is so seemingly intractable. Perhaps because the now daily reminders that the scourge of vicious hatred has not departed from our midst dulls our sensitivity and mutes our outrage.

But I now feel compelled to speak, and, in so doing, to address not just the purveyors of hate—that would be easier, albeit futile—but those that tolerate anti-Semites; that disclaim their message but defend their right to advance it; that, in the process, enable them to spew hatred of Jews and the Jewish people—ofen under the blanket protection of “free speech.”

Pittsburgh and Poway are but examples—perhaps the most frightening and brutal examples— of a resurgent anti-Semitism that is engul f ng our country. According to a recent survey conducted by

the American Jewish Committee, nearly nine out of ten American Jews (88 percent) say anti-Semitism is a problem in the US today—almost 40 percent call it a very serious problem. Nearly a third of the Jews polled have avoided publicly wearing, carrying or displaying things that might identify them as Jews; a quarter have avoided places or events out of concern for their safety; a third reported that Jewish institutions with which they are a f liated have been targeted by anti-Semitic attacks, gra fti or threats. Not a day goes by without the report of anti-Semitic incidents in communities throughout America; swastikas painted on, and in, school buildings and playgrounds; at Duke University, where a swastika was painted over a mural honoring the victims of the Pittsburgh synagogue shootings; at UCLA, where the administration gave tacit approval to the National Conference of Students for Justice in Palestine, whose ranks include leaders who have tweeted such statements as “let’s stu f some Jews in the oven,” and “every time I read about Hitler, I fall in love all over again”; in multiple Brooklyn neighborhoods, where acts of anti-Semitic violence against Orthodox Jews have become commonplace—shul windows smashed and pedestrians violently assaulted. My purpose here is not to chronicle these heinous acts. Rather, I want to explore how civil society has, by its actions or its failure to act, enabled such conduct to slowly work its way beyond the fringes of our society, both lef and right, and in f ltrate the mainstream of our social fabric.

Let me illustrate: Earlier this year, videos surfaced on social media showing high school students in Garden Grove, California, giving the straight-arm Nazi salute while singing

a German military song. One could, I suppose, write of such conduct as the prankish, sophomoric actions of uneducated youth. But what I found particularly distressing was the reaction of the mainstream press as the videos went viral. T is conduct, regardless of intention or motivation, was pure, unadulterated anti-Semitism; the type of conduct that should have been immediately and universally condemned. But when USA Today reported on the incident, the response was equivocal: “[t]aking disciplinary action sends a direct message about whether hate will be tolerated, but at the same time raises questions of freedom of speech.” Freedom of speech—the tolerance of intolerance.

Tere is nothing new or unique about anti-Semitism. What is shocking, however, is the degree to which the mainstream of civil society—not the radical fringes of right and lef , but our core institutions and opinion makers— academics, public intellectuals and journalists—have blithely tolerated the most blatant acts of intolerance.

Several weeks ago, Columbia University invited the prime minister of Malaysia, Dr. Mahathir Bin Mohamad, to address its Global Leadership Forum. Dr. Mohamad is a notorious, self-proclaimed anti-Semite and Holocaust denier.

Among his vile pronouncements:

“I am glad to be labeled anti-Semitic.”

“Today the Jews rule this world by proxy. Tey get others to fght and die for them.”

“You cannot even mention that in the Holocaust it was not six million [Jews who died].”

“ Te Jews are not merely hook-nosed, but understand money instinctively.”

But despite this history—known to all—one of the world’s most prestigious universities extended an invitation to an outspoken, vile anti-Semite to address its students.

A fer news of this invitation became public, I wrote the following to

10 JEWISH ACTION Winter 5780/2019

FROM

THE DESK OF ALLEN I. FAGIN

Allen I. Fagin is executive vice president of the OU.

Columbia’s president, Lee Bollinger: I am an alumnus of Columbia College, Class of 1971. I have been an active Columbia alum, having served for several years on the Columbia College Board of Visitors. I currently serve as a member of the Board of Directors of the Columbia-Barnard Hillel.

As so many Columbia alumni, I was shocked at Columbia’s decision to permit Prime Minister Mohamad of Malaysia to speak at the University. Tere is no dispute whatsoever that the Prime Minister is a rabid anti-Semite and a Holocaust denier. Giving him a forum at Columbia is simply inexplicable. Speaking at any University . . . particularly Columbia . . . is a privilege, not a right. I had always felt that Columbia in general, and you in particular, sought by its conduct and its decisions to live the values that it seeks to inculcate in its students.

I call upon you, even at this late date, to place these values that we all cherish so dearly above all else, and to cancel this misguided appearance.

President Bollinger’s ofce responded, in relevant part, as follows:

You are correct that I fnd the anti-Semitic statements of Prime Minister Mahathir to be abhorrent, contrary to what we stand for, and deserving of condemnation. Nevertheless, it is in these instances that we are most strongly resolved to insist that our campus remain an open forum and to protect the freedoms essential to our University community.

T is is the tolerance of intolerance. “Protect the freedoms essential to our University community.” But what of the freedom to be sheltered from vili fcation based on one’s religious identity? Must an “open forum” include the right to slander and abuse?

In his speech, the Malaysian prime minister defended his absolute right to preach hatred: “When you say ‘you cannot be anti-Semitic,’ there is no free speech. I am exercising my right to free speech. Why is it I can’t say something against the Jews? . . .”

So there we have it. A rabid

anti-Semite was granted license to spew his venomous remarks at the invitation of one of America’s most prestigious institutions. And his right to do so defended—tolerated—by one of America’s foremost intellectuals. Not by a street thug ripping of an Orthodox woman’s wig while she walked with her children on a Brooklyn street; not by a group of ignorant teenagers giving a Nazi salute around a swastika made of beer cups; not by a group of white supremacists in Charlottesville chanting “the Jews will not replace us.” No, this defense of permissible hate speech was from the president of Columbia University, the same institution that hosted the Jew-hating president of Iran, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, in 2007. At least then, President Bollinger had the moral courage to take the stage in advance of Ahmadinejad’s address, introducing him by noting that the Iranian president exhibited “all the signs of a petty and cruel dictator,” and adding that by denying the Holocaust, Ahmadinejad was “either brazenly provocative or astonishingly uneducated.” But not this time. Now, with anti-Semitism rearing its ugly head across our nation and beyond, the president of Columbia University deliberately chose to tolerate the intolerant.

Our mainstream media has likewise contributed to the tolerance of anti-Semitism. How vividly do we all recall the April 2019 publication by the international edition of the New York Times of a despicable cartoon depicting a blind, kippa-clad President Trump being led on a leash by a dachshund with the visage of Prime Minister Netanyahu, a Star of David prominently displayed around its neck. Te cartoon’s message was crystal clear: Israelis—Jews—are so in control of world a fairs that they could lead American presidents wherever they wish and have them blindly and obediently follow.

T is latest in a cascading series of ofenses by the New York

Times prompted op-ed columnist Bret Stephens to write:

Imagine, for instance, if the dog on a leash in the image hadn’t been the Israeli prime minister but instead a prominent woman such as Nancy Pelosi, a person of color such as John Lewis, or a Muslim such as Ilhan Omar. Would that have gone unnoticed by either the wire service that provides the Times with images or the editor who, even if he were working in haste, selected it? Te question answers itself. And it raises a follow-on: How have even the most blatant expressions of anti-Semitism become almost undetectable to editors who think it’s part of their job to stand up to bigotry?

Our American democratic tradition, rooted in First Amendment values, has seemingly placed the right to speak freely above all other societal norms. But one must question whether such a hierarchy of values in fact fosters the democratic and pluralistic ideals that we aspire to or whether it simply legitimizes conduct that carries within it the seeds of the ultimate demise of democracy itself.

In a recent opinion piece published in the New York Times, entitled “Free Speech is Killing Us,” Andrew Marantz decried the efects of ubiquitous, unregulated, hate-f lled pronouncements on social media, tolerated by our infatuation with free-speech protections:

Noxious speech is causing tangible harm. Yet this fact implies a question so uncomfortable that many of us go to great lengths to avoid asking it. Namely, what should we—the government, private companies, or individual citizens—be doing about it?

Nothing. Or at least that’s the answer one ofen hears from liberals and conservatives alike. Some speech might be bad, this line of thinking goes, but censorship is always worse. Te First Amendment is frst for a reason. . . .

Free speech is a bedrock value in this country. But it isn’t the only one. Like all values, it must be held in tension with others, such as equality, safety and robust democratic participation. Speech should be protected, all things

11 Winter 5780/2019 JEWISH ACTION

being equal. But what about speech that’s designed to drive a woman out of her workplace or to bully a teenager into suicide or to drive a democracy toward totalitarianism? Navigating these trade-ofs is thorny, as trade-ofs among core principles always are. But that doesn’t mean we can avoid navigating them at all.

Indeed, our right to say whatever we want, wherever we chose to, is not limitless. First Amendment protections have never applied to the private sector—only to government action. And even our First Amendment jurisprudence is bounded. As Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. famously observed, no one is free to shout “f re” in a crowded theater. Libel and slander are actionable. Incitement of violence and child pornography are all forms of speech, and yet we prohibit them without fear that the very foundations of our freedom will come crashing down.

Jewish law likewise places limits on “free speech.” Tere is a Torah prohibition against gossip: “Do not go around as a gossiper among your people” (Vayikra 19:16). Lashon hara is a subset of this broader prohibition. As the Rambam explains: “ Tere is a far greater sin that falls under this prohibition [of gossip]. It is ‘the evil tongue,’ which refers to whoever speaks despairingly of his fellow, even though he speaks the truth” (Mishneh Torah, Hilchot Deot 7:2). Whoever speaks with an evil tongue, the Talmud teaches us, it is as if he denied God (Arachin 15b). In the last century, Rabbi Yisrael Meir Kagan, zt”l, the Chofetz Chaim, devoted much of his enormous Torah scholarship to the laws of speech, and the avoidance of lashon hara.

And for many Western democracies outside of the United States, hate speech is routinely banned as inimical to social order. Recently, for example, a German neo-Nazi—the former leader of the far-right National Democratic Party—was convicted of Holocaust denial by a German court. He appealed his conviction, arguing that a ban on Holocaust denial was a violation

of his human rights. Te European Union Court of Justice upheld his conviction, holding that denial of the Nazi slaughter of six million Jews was “not a basic human right.” Te court found that promotion of Holocaust denial “could not attract the protection for freedom of speech” incorporated in the European Convention on Human Rights, as such statements ran “counter to the values of the Convention itself.”

Columbia University’s President Bollinger is surely not an anti-Semite, and Columbia University is not an anti-Semitic institution. Yet in their zeal to pray at the temple of free speech and academic freedom, they have become enablers. Teir position is cowardly and morally repugnant. Tey have tolerated intolerance, and in the process sacri fced the very freedoms that we cherish and that they seemingly seek to foster.

In a seminal essay entitled “Repressive Tolerance,” noted philosopher Herbert Marcuse wrote as follows:

In the past and diferent circumstances, the speeches of the Fascist and Nazi leaders were the immediate prologue to the massacre . . . But the spreading of the word could have been stopped before it was too late: if democratic tolerance had been withdrawn when the future leaders started their campaign, mankind would have had a chance of avoiding Auschwitz and a World War . . . When tolerance mainly serves the protection and preservation of a repressive society, when it serves to neutralize opposition and to render men immune against other and better forms of life, then tolerance has been perverted.

T is was, I believe, the true intent of our Founding Fathers—to balance the liberties we cherish, including the right to speak our minds and freely express our views, against the rights of every citizen to live in safety, free from persecution and the gnawing insecurity of organized hatred and vili fcation.

In August 1790, President George Washington wrote a now-iconic letter to the Hebrew Congregation of Newport, Rhode Island. Te letter is remarkably short—only 340 words— but its impact on American history has been profound. In it, President Washington reassured those who had fed religious tyranny that their lives in the nascent American nation would be forever altered; that religious “toleration” would give way to religious liberty; and that the power of the state would never be used to interfere with matters of belief or religious practice.

It is now no more that toleration is spoken of as if it were the indulgence of one class of people that another enjoyed the exercise of their inherent natural rights, for, happily, the Government of the United States, which gives to bigotry no sanction, to persecution no assistance, requires only that they who live under its protection should demean themselves as good citizens in giving it on all occasions their efectual support. We pine for a society that gives to bigotry no sanction. We long for a society that gives to persecution no assistance. Tose who seek to ful f ll this great vision can no longer tolerate the intolerance that surrounds us.

12 JEWISH ACTION Winter 5780/2019

Anti-Semitic political cartoon that appeared in the international edition of the New York Times in April 2019. Illustration: Antonio Antunes/Expresso, Lisbon, Portugal/CartoonArts

THAN JUST A PERFORMANCE WWW.EITANKATZ.COM | 718.770.7973 | INFO@EITANKATZ.COM

By Gerald M. Schreck

“Never before in Jewish history has it been so easy to learn a blatt gemara as it is today.”

Te above line could have been written in 2019, but it was actually written in 1997 in an article published in the now-defunct Jewish Observer entitled “New Technological Frontiers in Dialing the Daf,” by Rabbi Eli Teitelbaum. Te creator of the famed Dial-a-Daf program, Rabbi Teitelbaum goes on to explain just how easy it is to learn the daf on the phone: “Just punch in the masechta code and the blatt number on your nearest phone and you are instantly connected to a master Rebbe who’ll explain the daf loud and clear.”

Te Dial-a-Daf, for those old enough to remember, was run from the basement of Rabbi Teitelbaum’s two-story house in Boro Park. According to a New York Times article on Dial-a-Daf, the phone system could accommodate a few hundred calls an hour, and most of the users were in the New York metropolitan area.

It’s hard not to chuckle when reading these lines. How far we’ve come in making learning the Daf easy, available and accessible! Tere’s a vast and impressive array of digital resources on the Daf that have made Daf Yomi a possibility for thousands who could have never even contemplated committing to it. As Dr. Henry Abramson, who writes and produces the “Jewish History in Daf Yomi” video series, a project of the OU’s Daf Yomi Initiative, says in

CHAIRMAN’S

MESSAGE

his interview in this issue with Jewish Action author Sholom Licht: “We are living at a moment of great opportunity in Jewish history . . . it is a ‘Gutenberg moment.’ We’re at the cusp of leveraging a new technology that has incredible implications for the Jewish people.”

I began studying the Daf thirty-four years ago, and I have my good friend Steve Savitsky, a former OU president, to thank for encouraging me to embark on this life-altering journey. Back in 1985, I visited Steve at his ofce and noticed the large volumes of Gemara arranged on the bookshelf. “Why do you have these volumes at work?” I asked. “I travel a lot for work,” he said. “What a better way to spend your time in the air than doing the Daf?” His words hit home. Even though I was running my own public relations frm and had a growing family at the time, I decided to take the plunge and commit to studying the Daf.

But this was the '80s—there was no Internet, no Gemara apps, no ShasPod. With the incessant demands of my career and family, I couldn’t manage to make a daily shiur. So I contacted Rabbi Mayer Apfelbaum, a”h, who became my “savior.” Rabbi Apfelbaum was the ingenious innovator who started the frst Torah tape lending library. Every month I would drive to his Boro Park home, which housed thousands upon thousands of audiocassettes with shiurim on the Daf from some of the best maggidei shiur at the time, and get a stack of new tapes, which I would return a few weeks later. I am forever indebted to Rabbi Apfelbaum and his legendary library for enabling me to stay on track and not give up on the Daf. I am also grateful to another friend of mine who made my journey into the Daf so much easier: Rabbi Meir Zlotowitz, a”h. Te Shottenstein Edition of the Talmud is my constant companion as I navigate the daily Daf. With the coming Siyum, I will have the tremendous zechus of having gone through yet another Daf Yomi cycle—I am grateful to Hakadosh Baruch Hu for continuing to give me the ability to persist in this lifelong quest of Torah study.

Before signing of, I would like to take

the opportunity to introduce you to the newest members of the Jewish Action Editorial Committee. Astute readers will have noted that our masthead has, for past few issues, included the following new names: Deborah Chames Cohen, Dr. Rosalyn Sherman and Rebbetzin Dr. Adina Shmidman. Deborah Chames Cohen, a partner at Kluger, Kaplan, Silverman, Katzen & Levine in Miami, is a seasoned family law attorney who is very involved in her local community. Dr. Rosalyn Sherman is a clinical psychologist who maintains a practice in Manhattan and serves as an adjunct associate professor in the Mental Health Psychology Department at Ferkauf Graduate School of Psychology at Yeshiva University. Rebbetzin Shmidman, who has spent years teaching Judaic studies to high school students, is currently the director of the OU’s Women’s Initiative and rebbetzin of the Lower Merion Synagogue in Bala Cynwyd, Pennsylvania. Each of these highly accomplished, talented women brings a unique and valued perspective to our robust editorial team. With their varied backgrounds and expertise in the felds of education, mental health, law and communal service, our newest Editorial Committee members help support our mission to enrich our readers Jewishly by providing articles that inspire and enlighten and provide an honest, open perspective on Jewish ideas, culture and thought not found elsewhere. Finally, I am grateful to Rabbi Yitzchak Breitowitz, senior lecturer at Ohr Somayach and a popular teacher at the OU’s Seymour J. Abrams Jerusalem World Center, who has taken on the role of rabbinic advisor for the magazine. Rabbi Breitowitz needs no introduction to our readers—he has been published in these pages numerous times—and his brilliance and wide-ranging knowledge in so many areas are well known in the Orthodox world. We are honored to have him on the Jewish Action team.

14 JEWISH ACTION Winter 5780/2019

Gerald M. Schreck is chairman of the Jewish Action Committee and an honorary vice president of the OU.

Beetology™ juices artfully layer the mild favor of organic beets with the delicate sweetness of ripe fruits and the bright favors of wholesome vegetables. It’s refreshing at any time of day. Your customers will be beeting down your door to try them!

Delights the Palate

No Preservatives or Additives

No Artifcial Colors or Flavors

Not from Concentrate

Refrigerated

For more information, contact dbuxbaum@kayco.com

15 Winter 5780/2019 JEWISH ACTION

Searching for Heather Dean

In a new memoir, a former entertainment journalist shares why she gave up a glamorous career to pursue newfound dreams in Israel

By Toby Klein Greenwald

By Toby Klein Greenwald

Apoised, statuesque woman enters the main hall of the OU Israel Center in Jerusalem. She is about to launch her memoir, Searching for Heather Dean: My Extraordinary Career as a Celebrity Interviewer and Why I Left It. The audience waits, rapt with curiosity, as she peruses her notes before she begins speaking.

A highly successful celebrity interviewer, Heather Dean has conducted more than 1,500 interviews with the likes of Robert Redford, Brad Pitt, Isabella Rossellini, Harrison Ford, Reese Witherspoon and Martin Scorsese. (And for this article, she gave a personal interview to Jewish Action!) But the most inspirational stories in her book are her own, written with sparkling wit and emotion—and no sugarcoating. Her bottom-line message: “Remember who you are.” For Dean, it took about thirty-five years to discover exactly who she is.

Born and raised in the affluent Cleveland suburb of Shaker Heights, Dean had a fascination with TV. This obsession, along with not wanting to be one of the “cool kids,” led her to spend hours watching, analyzing and dreaming of working in the entertainment industry.

“I used my tenure as a teenage social outcast to hone my skills as a perceptive observer of people,” said Dean, who shared that she would often be invited to braid the hair of other girls, but not invited to their parties. Her experiences also helped her to be empathetic later in life to young people who consider themselves outsiders

Growing up, Dean attended Hebrew school, which lef her uninspired. Moreover, she found the Conservative synagogue services “maddeningly and mind-numbingly endless.” She felt that being shown flms about Judaism on Shabbat, being driven to synagogue and being allowed to write and cook on synagogue premises on Shabbat was a classic case of “Do as I say, not as I do.” “It certainly didn’t have a positive efect on me,” she says.

A Rising Career

One summer, while visiting her parents who had moved to Portola Valley, California, Dean was accepted as an intern at People Are Talking, San Francisco’s highest-rated morning TV talk show at the time. She loved being part of the team and getting her foot in the door. She saw many women in senior- and executive-level production positions who were making important decisions. People Are Talking Producer DeAnne Hamilton gave her the following advice: “Go for it. Just go for it.” Te lesson in courage served her well.

“That life-altering summer [internship] was ultimately bittersweet. I could foresee a future in broadcasting that looked promising. It was also the summer my mother learned she had cancer,” she writes in her book.

“She broke the news to all of her children in the most nonchalant of ways . . . I didn’t want to pry details out of her if she wasn’t ready to tell us more. In any case, I preferred the cold comfort of denial to the hard truth that she might leave this world in the near future.”

Dean returned to Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, and convinced the school to let her spend her last semester as an intern; subsequently, she was accepted by MTV in Manhattan as one of three news department interns, marking the fulfillment of a dream. She moved up the totem pole, eventually becoming a premier entertainment journalist working for E! Entertainment Television, the Associated Press News Radio and other television networks.

Dean has positive things to say about some of the celebrities she interviewed, even as she grew, over time, to reject their lifestyles and choices. Thus we learn that neither George Harrison nor Sinéad O’Connor displayed “an ounce of arrogance”; Rosie O’Donnell “avoided speaking unkindly about other people”; and Robin Williams was “totally open

with you . . . Throw him a topic, and he’d weave a hilarious tapestry.”

She joined a press junket to Houston for the release of the Hollywood drama Apollo 13, met with the leads and director, declared Tom Hanks “a mensch” and quoted him as saying, “About every five years, I’ve gone through some sort of process of reexamining where I was in life, as a man, as an actor . . .”

Nevertheles, the more Dean spoke to actors, the more she witnessed their constant battle to stay young, relevant and successful. “I have been told by such stars as Madonna, Gary Oldman and Drew Carey that fame and popularity do not solve your problems, nor do they wipe out your inner insecurities and struggles.”

Toby Klein Greenwald, a regular contributor to Jewish Action, is a journalist, playwright, poet, teacher and the artistic director of a number of theater companies. She is the recent recipient of the Lifetime Achievement Award from AtaraThe Association for Torah and the Arts for her “dedication and contributions in creative education, journalism, theatre and the performing arts worldwide.”

17 Winter 5780/2019 JEWISH ACTION

PROFILE

Fame and popularity do not solve your problems, nor do they wipe out your inner insecurities and struggles.

Today, Heather Dean produces a popular weekly podcast for Aish.com.

JA: What was the most moving or exciting interview you did from your old life and from your new life?

HD: From my old life, it was the first time I interviewed Mike Wallace of 60 Minutes. Knowing his reputation and the fear he strikes into people . . . but within one minute I could tell, this man is a pussycat, and he gave the most professional interviews because his sound bites were clear and concise. In my new life, I would say Rabbi Berel Wein, because, in the religious Jewish world, he is admired by people from all streams, and through his TV show Ask the Rabbi he reaches a broad spectrum of Jews. He has a depth of scholarship in history and the Bible, and is a giant in our times. He’s also very humble.

JA: What advice do you have for a would-be journalist/interviewer?

HD: Know the body of work of the person you’re interviewing—or at least read or watch whatever they are promoting. Be nonjudgmental in your everyday life, and your interviewees will pick up on that vibe and speak more freely.

JA: What would you say to someone who is thinking of going into broadcasting or the performing arts?

HD: It’s tough, because you will be expected to work on Saturdays. Going into that field in the frum world? I’d say, welcome to the club, and know there is already a [creative] community that will help you grow professionally.

JA: How does one retain humility in that world, even in the frum world?

HD: Have kids! . . . When you’ve had that kind of a day that your career gets a [positive] bump, you have to remember you’re an eved [servant of] Hashem. Remember who you really are.

JA: If you could meet any of these celebrities again, what would you ask them today?

HD: I would ask Oprah about spirituality, not because she’s so famous, but because she’s so influential. [When I interviewed her] she was a joy, stayed on topic, had a rich vocabulary. . . . I’d ask her about her spiritual journey. She has overcome a great deal of adversity.

JA: What guidance do you have for those who become Torah-observant, regarding family relationships with those who are not?

HD: To be very accepting. . . . Don’t have high hopes that you’ll change any minds. Rather, hope that they will accept you on your journey.

Dean’s memoir Searching for Heather Dean: My Extraordinary Career as a Celebrity Interviewer and Why I Left , which she presented at a book launch at the OU Israel Center in September.

Dean had always been a very spiritual person, but the heartbreaking diagnosis of her mother’s cancer, as well as her own struggle with health issues, was a turning point. She writes in her book, “I couldn’t change my mother’s situation, nor heal her, but this ‘detour’ and concern about health was the necessary catalyst for me to make some major lifestyle changes of my own.”

After her mother’s death in 1995 following a long illness, Dean fell into “an emotional fog” and sought counsel from a rabbi. A friend gave her a list of four local rabbis on Manhattan’s Upper West Side, where Dean lived at the time. She called the first one on the list, Rabbi Avraham Goldhar, who, along with his wife Yocheved, became mentors who shepherded Dean on her spiritual journey.

One day—amid a life busy with movie screenings, Broadway shows, comedy gigs and dress rehearsals of Saturday Night Live—Dean realized that she had no one to interview. It was Rosh Hashanah, and all of the celebrities’ publicists “were in Temple!”

Dean went home, dressed modestly, and walked to Aish HaTorah New York, where she had previously met with Rabbi Goldhar (wondering all the while what the word “Aish” on the building meant). “So I won’t enjoy myself,” she recalled thinking, “but I’ll kill some time.” Amazingly, she discovered that, although she had not read or spoken Hebrew in twenty years, she was able to follow the service—something she attributed to “an act of God”—and she even recognized some of the melodies. “Despite myself, I found myself fighting back a tear.”

She began to attend classes at Aish, although she was sure she would not go as far as observing Shabbat, keeping kosher or regularly attending synagogue. She thought of herself as pro-God and anti-religion. “I was already on a spiritual path that was a philosophical path,

18 JEWISH ACTION Winter 5780/2019

Satisfying Crunch with Uncompromising Flavor

Our delicious Gluten Free crackers are crispy and irresistible. They’re uniquely made from potatoes instead of soy, corn or rice and they’re absolutely, positively, 100% Gluten Free.

19 Winter 5780/2019 JEWISH ACTION

GLUTEN FREE

Original · Toasted Onion · Pepper · Everything absolutelygf.com \absolutelygf @absolutelygf Absolutely reach out to Laura to get more information at lmorris@kayco.com perfect pair with your chanukah dips

but not adhering to any rules. The only rituals I adhered to were taking a shower every morning after a race walk in Central Park and then getting dressed while listening to The Howard Stern Show.”

So another Yom Kippur came and went, and she didn’t fast. “I perceived myself to be a ‘good person’ who didn’t require atonement. I knew I wasn’t perfect, but I figured I was also far from being a sinner.”

But Dean continued to question and investigate. “I consulted with [a religious woman] who used to be a staunch feminist, about male-female relationships, wondering, for instance, how realistic being shomer negiah is in this day and age. The next hurdle was handling twenty-five hours of Shabbat.”

Dean writes about falling for a non-Jewish man and walking away from the relationship, even though, at that point, she was not yet fully Torah-observant. During a pivotal conversation with Rabbi Goldhar, he described some of the potential conflicts that could arise over religious issues, asking Dean, “What long-term goals do you share?”

Writes Dean: “[It was a] simple question, but it had me stumped. Who could think of long-term goals when the present was so all-encompassing and delightful?”

Subsequently, Dean met her then-boyfriend at a Starbucks, but “he didn’t take the bait” when she told him that she “could only be in a relationship with a man who was either Jewish or interested in learning about Judaism.” He smiled and stayed silent. Then the tears came. She writes, “It was the hardest goodbye to a man I had ever said.”

Although Dean had been to Israel a number of times as a young girl, as she attended more and more classes at Aish, she decided to join a few of Aish’s trips to Israel. It was during a trip in 1999 that she knew she was ready to make some dramatic changes.

She writes: “Nothing prepared me for the exquisiteness and majesty I would feel from seeing the Golan Heights with my eyes and . . . my soul.”

“We were going north along the road bordering Jordan . . . and the further we went north the more it impacted me,” she said. “I was already praying

from a siddur, and the Morning Prayers [talk] about the goodly land; . . . it was connecting the prayer book to the land. That’s spirituality—seeing the actual land and knowing that Hashem made good on His promise.”

Back in the States, New Year’s Eve 1999 arrived on a Saturday, and Dean had “an invite to almost every party in town.” But instead of spending it at “the party of the century,” Dean, who had started attending Shabbat services regularly, made a fateful decision: She spent New Year’s Eve at Aish, enjoying a lovely Shabbat meal and dancing with women singing Yibaneh haMikdash. “That’s how I brought in the new millennium. I decided to celebrate a new era in a way that joined me with my fellow Jews, my spirituality and my identity.” She searched inside herself and finally declared, “I could be so much more.” It was a seismic shift for her. And regarding God, she writes: “He waited until I made this decision—with a full heart.”

Eventually, Dean decided to study Torah at Neve Yerushalayim in Israel. “I was happiest when I was in a Torah class.” Yet, she still felt that she had

20 JEWISH ACTION Winter 5780/2019

Dean presenting a workshop on the “Power of Podcasting: Promoting Your Published Work with Successful Podcast Interviews” at the Jerusalem Women’s Writers Seminar in 2018. Photo: Reuven Ansh Photography

a foot in two worlds. “It would take me many years to figure out how to meld the best of both of my lives.”

While living in Jerusalem, Dean found a role model in Rebbetzin Chaya Levine, a woman steeped in chesed while balancing family and work responsibilities. And as Dean met more and more people like the rebbetzin on her new journey, the more she felt they engendered more meaningful experiences than she’d ever had interviewing celebrities. (Years later, Rebbetzin Levine became an even greater role model to Dean, exemplifying great faith and nobility when her husband, Rabbi Kalman Levine, was murdered in the terrorist attack at a synagogue in Har Nof in 2014.)

A New Chapter

When she felt ready, Dean joined the shidduch scene in Israel, and was introduced to Andy Haas. Te

two hit it of, and got engaged in Israel, where they planned to live.

Dean felt her mother’s presence at their wedding, held in New York a few weeks later, and felt like all of the numerous phases of her life were coming together “in a glorious crescendo.”

“Part of accepting a life of Torah and faith in God means knowing that both our gifts and our challenges are given to us for a reason,” Dean writes in her book. “Nothing God does is random, arbitrary or without purpose.”

Reflecting back on her career while at the book launch, Dean says, “It really was a lot of fun and an extraordinary career. But here we are in Jerusalem, and [it’s] a more meaningful life than anything outside the Land of Israel and outside of Torah Judaism can provide.”

Dean and her husband were blessed with several children, all of whom were born when Dean was already in her forties. She

spent a few years as a full-time mom—enjoying every minute it.

Once her children became school age, Dean decided to return to broadcast journalism, using her talents and skills to spread Torah. She hosted Israel News Talk Radio’s Conversations with Heroes and The Modern Jewish Home. Presently, she produces a popular weekly podcast for Aish.com called At Home in Jerusalem, where she interviews Torah personalities on Judaism, family life and other issues.

She quotes Rabbi Noah Weinberg, zt”l, on the question: What is real happiness? “Happiness is appreciating what you have—counting your blessings.”

She concludes her book by recalling a sentiment from Pirkei Avot 4:1: “A rich person is a person who enjoys what he has . . . I’m aiming for that.”

21 Winter 5780/2019 JEWISH ACTION

Schedule your visit at youngisraelwh.org/visit or by contacting visit@youngisraelwh.org or 860-233-3084 Average Commute Time 7 minutes Affordable Housing Vibrant Shul Lower Cost of Living Robust Job Market here! I M A G I N E Y O U R F A M I L Y Incredible Tuition Subsidy Eruv, Mikveh, Kosher Food Thriving Jewish Life O N E V I S I T and you will love West Hartford, CT Come join us for a w d! INCREDIBLE SUBSIDIZED TUITION AT THE NEW ENGLAND JEWISH ACADEMY! Grades K-1: $5,000 Grades 6-8: $9,500 Grades 2-5: $7,500 Grades 9-12: $12,000

IN THE

DAF DIGITAL AGE

The Talmud is the lifeblood of the Jewish people and Daf Yomi exempli fes the mass reconnection to that source of faith and guidance we experience in our age. With all the challenges of the Internet age—the constant distraction; the onslaught of information; the radical openness to everything sacred and unholy; the challenges to our personal and family sanctity—the open page of the Talmud looks both the same and very di ferent than in past years. Te new tools available to us, the audio-visual-textual commentaries available to beginner and expert alike, ofer people with di ferent skill sets entry to the challenging text of our tradition. Many recent thinkers have compared the Talmud to the hyper-linked text of the Internet in many ways. While there is some truth to this abstract comparison, a contrast in the other direction deserves our attention as well. In many ways, Daf Yomi is the opposite of the Internet. “ Te Daf” begins with Berachot 2a and continues for 2,711 pages until it concludes with Niddah 73a. Of course, you can start anywhere in the middle, particularly at the beginning of any of the thirty-seven masechtot. But it has a discrete beginning and end, followed by a siyum celebration and return to the beginning. In contrast, the Internet

has no entrance or exit. Every article contains links to many others. Every person has his own beginning and only stops when other concerns beckon. Even an individual never enters or exits his social media feed at the same place twice. Daf Yomi approaches a f nite text with in f nite depth. Te Internet, like the universe, constantly expands.

Te Daf, like its name, is an experience of the page. We study the text, perhaps with additional tools when available, but always remaining on, or at least returning to, the page. Te Internet has no anchor, sending you across the globe with endless links. YouTube videos move from one to the next, sending the user down the winding path of an ofen ba f ing algorithm. Social media giants desperately try to keep users on their platforms, generally to little avail. Te constant movement of the Internet keeps users in motion, circling across the span of information. Te Daf contains an internal speed limit and single direction—always forward, onto the next page at a uniform pace.

Finding explanations of the Daf requires efort. Some commentaries can be found encircling the text, but locating the illuminating entry in Sefer HaMitzvot or responsum of the Chatam Sofer requires skill and no small measure of Divine

assistance. Alternate opinions on the Internet lie a Google search away. No opinion is too large or too small to lack a contradictory view, readily available to anyone with the time and interest to delve into the maze.

Perhaps most importantly, learning the Daf generates community. Even if you do not attend a shiur where collegiality naturally grows, merely studying the same page as thousands of others creates instant connections. Many wedding table conversations begin, not with the awkward questions about hometown and occupation, but with “did you see today’s Daf?” As social scientists have adequately documented, the Internet causes isolation despite its focus on “communities.” Te falseness of online persona, the distraction from real life, the super fciality of the relationships detract from meaningful community life.

When used healthily, the Internet can be a strong tool for life and for learning the Daf. In these pages, we explore how Daf Yomi can transform lives and how digital tools can enhance and deepen that experience.

THE

Introduction by Gil Student

Rabbi Gil Student writes frequently on Jewish issues and runs Torahmusings.com. He is a member of the Jewish Action Editorial Committee.

BEHIND the DAF

DISCUSSING DAF YOMI WITH SOME of the MOST DISTINGUISHED MAGGIDEI SHIUR

Q: How did you come to start teaching Daf Yomi?

Rabbi Moshe Elefant: Many years ago, I attended a Daf Yomi siyum where Rav Mordechai Gifer, rosh yeshivah of Telz Yeshiva in Cleveland, Ohio, was one of the speakers. In his inimitable way, Rav Gifer said that in Europe, a “Shas Yid” was someone who had gone through the entire Shas. I can’t convey the idea the way he did. But he said that you didn’t have to be a rav or a rosh yeshivah to be a Shas Yid; you could have been an ordinary “ba’alebos” (lay person). But if you were a Shas Yid, it was considered a real status—a real achievement. Once I heard that, I knew I wanted to be a Shas Yid.

Around thirty years ago, I began teaching a Daf Yomi shiur at 5:40 every morning for members of a shtiebel in Brooklyn near my house. I am about to fnish my fourth cycle.

Fourteen years ago, the OU, being ahead of the curve, decided to launch a Daf Yomi shiur online, which was a revolutionary project at the time. In addition to delivering my early morning shiur at the shtiebel, I began recording a Daf Yomi shiur at home, or on occasion, at the OU headquarters in Manhattan, that is broadcast online. Today, about 2,000 listeners tune in from all over the world, including North America, Israel and Europe—and even places like Gibraltar and South Korea.

Rabbi Moshe Elefant is chief operating ofcer of OU Kosher and a maggid shiur for the OU’s Daf Yomi webcast (which attracts 2,000 participants daily, making it one of the most popular online Daf shiurim in the world).

Rabbi Yisroel Edelman: Te Young Israel of Deerfeld Beach started a Daf Yomi shiur some thirty years ago. Initially, there was resistance because there was no consistent maggid shiur and the participants weren’t coming regularly. But a few shul members persisted, and baruch Hashem, the shiur began to fourish. Back when the shiur started, many of the Deerfeld

23 Winter 5780/2019 JEWISH ACTION COVER STORY

Interviews by Dovid Bashevkin and Sholom Licht

Rabbi Dovid Bashevkin is director of education for NCSY and a member of the Jewish Action Editorial Committee. His most recent book is Sin a gogue: Sin and Failure in Jewish Thought (Boston, 2019).

Sholom Licht is a freelance writer living in Queens, New York. He received his BA from Bar-Ilan University and MA from the Bernard Revel Graduate School of Jewish Studies.

Beach residents did not even live here year-round, so attendance was an issue. Today, a signifcant portion of the community lives here year-round.

I started delivering the Daf Yomi shiur when I joined the shul eleven years ago. Nowadays, during “the season,” we have more than 100 participants coming to the shiur. It’s probably one of the largest Daf Yomi shiurim in the country.

Rabbi Yisroel Edelman is rav of the Young Israel of Deerfield Beach in Florida.

Rabbi Aryeh Lebowitz: Fifeen years ago (two cycles ago), before the siyum, Rav Dovid Willig came over to me and Rabbi Shalom Rosner—we were learning together—and said, “You both have shuls; you really should be giving a Daf Yomi shiur.” We told him we didn’t think there was enough interest “No one’s going to come,” we said. But he persisted. Eventually we both started giving Daf Yomi shiurim in our shuls and, baruch Hashem, it worked out very well for both of us.

Rabbi Aryeh Lebowitz is the rav of Beis HaKnesses of North Woodmere in New York.

Q: Does learning Daf Yomi change one’s appreciation of Gemara?

Rabbi Lebowitz: Doing the Daf gives one a better appreciation of the cadence and rhythm of the Gemara.

Even if one doesn’t remember every Gemara he learns, he develops a sense of how the Gemara uses terminology and ideas and what types of questions the Gemara would ask. To really understand any [kind of] learning, one needs to get a broad picture of the language of that discipline.

Rabbi Elefant: Ofen when one learns Shas, the topics can be very esoteric, such as Zevachim, Menachos Temurah.

In Kerisos, which we are currently learning, there doesn’t seem to be any topic in the frst fve blatt [Yiddish for daf] that relates to everyday life. It’s usually at this point that Daf Yomi learners start to feel tired.

Even when the Gemara seems to be dense and enigmatic, I try to point out how it does, in fact, relate to our contemporary lives. For example, we recently came across a discussion in the Gemara that centers on how much of a korban needs to be consumed. I pointed out that this is the source for the halachic concept of kezayis (a Talmudic unit of volume). From this Gemara, we learn how much we need to eat in order bentch, et cetera. So I always try to incorporate halachos that apply to daily life.

However, one needs to recognize that even when a Gemara has little to do with one’s day-to-day life, learning Gemara over time gives one a certain way of thinking. Afer learning Gemara so many times, you start to think like the Gemara, which is tremendously valuable in and of itself.

Rabbi Edelman: What’s very geshmak [enjoyable] about learning Daf Yomi is that you get a feeling for the entire masechta. When one learns in yeshivah, he tends to be focused on the daf that he’s learning. But each masechta has its own complexion, its own favor. When you learn the Daf, it’s true you may not remember

24 JEWISH ACTION Winter 5780/2019

Rabbi Elefant’s webcasts are available on the OU’s new All Daf app.

After learning Gemara so many times, you start to think like the Gemara, which is tremendously valuable in and of itself.

Rabbi Moshe Elefant Photo: Kruter Photography

Rabbi Moshe Elefant

the details, but you get the fow and the favor of the masechta.

Q: What advice would you give to someone who is starting to learn Daf Yomi? What can one do to get the most out of Daf Yomi? And, as a follow up, is the Daf for everyone?

Rabbi Lebowitz: Come up with a system of chazarah (review) and review the material properly. It’s probably the best thing you can do.

Afer each section, I take a bird’s-eye view. What did this section just say? And for each amud (one side of a page which is only half of the daily page), I write down three or four sentences that summarize that section. If you can’t summarize the idea in a sentence, you probably don’t have the clarity that you need.

Rabbi Elefant: Currently, you no longer need to be present at a physical Daf Yomi shiur. Tere are plenty of shiurim online, and so a Daf Yomi learner has no reason to fall behind. If you’re going on

When it comes to learning the Daf, it's important to think of it as one daf at a time. You should not look at it as a masechta or a seder at a time or as learning all of Shas; thinking of it as one daf at a time makes it much more manageable. And then eventually it just starts piling on, and over time, you will complete a mesechta and then a seder, and eventually all of Shas.

— David Katz is an operations director for a multinational company and is in his third cycle teaching Daf Yomi at the Young Israel of Memphis in Memphis, Tennessee.

As told to Binyamin Ehrenkranz, a member of the Jewish Action Editorial Committee.

vacation, take your Gemara on the road with you and listen to a shiur. People ofen say to me, “I learned this masechta and that masechta and I really don’t remember them. So maybe I should abandon the Daf?” Te question is, “So what are you going to do instead?” If you stop learning the Daf, will you take on a diferent shiur with the same kind of consistency and commitment?

Regarding the fast pace of the Daf,

I’m not convinced that the people who are learning at a slower pace are remembering more. So if they’re not remembering more, what have they accomplished? Tey have given up the consistency and commitment [of Daf Yomi], they have given up the opportunity to go through all of Shas, and what has been the payback for it?

Of course, the Daf isn’t for everybody. Certainly, if you are learning in yeshivah or kollel full time, you are not a Daf

25 Winter 5780/2019 JEWISH ACTION

THE CHANUKAH GIFT THAT WILL LIGHT UP EVERY SHABBOS the NEW shabbos reading light VISIT OUR WEBSITE FOR MORE INFORMATION AND TO PURCHASE SHABBOSLITE.COM patent pending E-Z SLIDE SHUTTER™ FLEXIBLE GOOSENECK DESIGN CRISP BRIGHT WHITE LED LIGHT DESKTOP MODEL HAS USB PORT TO CHARGE PHONE TRAVEL MODEL HAS CLIP FOR EASY POSITIONING CAN BE USED WORLDWIDE Shabbos Readng Light! 2019 ACCLAIMED AS THE BEST

Yomi candidate. But for those of us who spend our days working, I can’t think of a better way to learn Torah consistently.