12 When Books Can Speak: A Glimpse into the World of Sefarim Collecting By Eli Genauer

16 A Passion for Rare Sefarim: Q & A with Rabbi Eliezer Katzman By Bayla Sheva Brenner

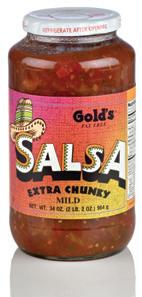

22 People of the Book: Five Hundred Years of the Hebrew Book From the Beginning of Printing Until the Twentieth Century By Akiva Aaronson Reviewed by Gil Student

24 When Leaders Fail Healing from Rabbinic Scandal By Yitzchak Breitowitz

44 Rabbis at Risk: What Can Be Done? By Barbara Bensoussan

50 Halachah and the Fallen Rabbi Q & A with Rabbi Hershel Schachter By Avrohom Gordimer

54 The Pioneers of Gush Katif— Ten Years After the Disengagement Section written and translated by Toby Klein Greenwald

58 Healing in the Aftermath of Trauma: Livnat Farjun

60 From “House of Faith” to Building the Negev: Yedidya Harush

64 A Child of Gush Katif: Yael (Cohen) Haramati

66 The Miracle Worker Behind JobKatif: Rabbi Yosef Zvi Rimon

68 On and Off the Beaten Track in the Gush Katif Museum By Peter Abelow

To Sleep, Perchance to Dream By Shira Isenberg

Meatless Meals During the Nine Days By Norene Gilletz

88 Torah MiEtzion: New Readings in Tanach–Bemidbar Edited by Rav Ezra Bick and Rav Yaakov Beasley Reviewed by Francis Nataf BOOKS

90 To Fill the Sky with Stars: Women Explore Their Midlife Challenges and Triumphs Edited by Miriam Liebermann Reviewed by Yael Zoldan

or Outreach: The Perennial Dilemma By Martin Nachimson

Cover design: Josh Weinberg

What’s the Truth About A Woman Bentching Gomel? By Ari Z. Zivotofsky

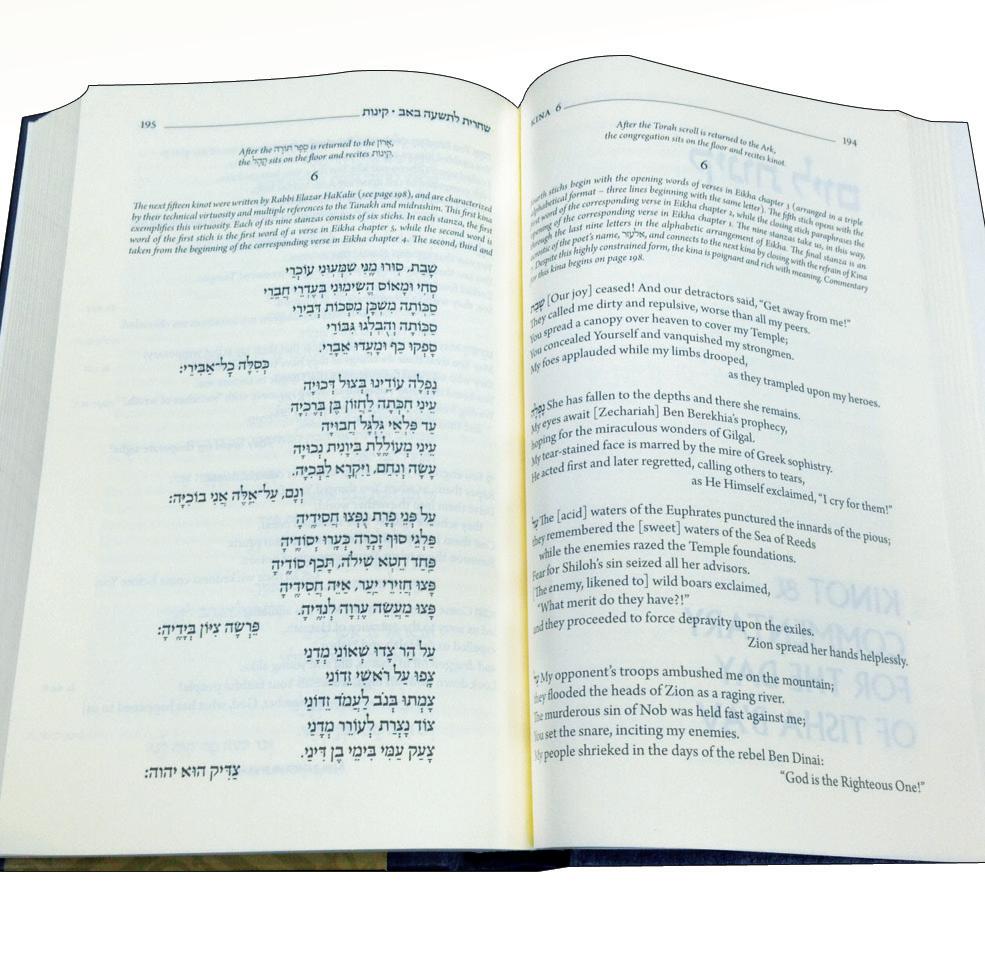

Making Tishah B’Av Personal By Steve Lipman

Jewish Action seeks to provide a forum for a diversity of legitimate opinions within the spectrum of Orthodox Judaism. Therefore, opinions expressed do not necessarily reflect the policy or opinion of the Orthodox Union.

g Alan Krinsky’s article on davening properly (“Pray or Play?,” winter 2014) is wonderful.

Too many of us are concerned with finding the “fastest minyan in town.” We are casual with our tefillot and, for many of us, davening is viewed as a tedious experience.

Rav Gedaliah Eisemann, the late mashgiach of Yeshivas Kol Torah in Yerushalayim, once said: “I’ve seen a lot of eccentric people, but I never saw any of them daydreaming while reading a newspaper. Why? Because they find it interesting. We have to make our davening and learning interesting by keeping it fresh and engaging!”

Extending Krinsky’s sports team metaphor, what about having a “coach’s” inspirational speech before each “game”? Shul rabbis should offer a brief and relevant message or insight before davening—twenty to thirty seconds long. This should be done before and even during davening.

BORUCH LEFF

Baltimore, Maryland

g While I enjoyed Bayla Sheva Brenner’s article about Jewish genealogy (“Jewish Genealogy: The Journey to Oneself,” winter 2014), I found it to be too focused on the Ashkenazic American experience. With the exception of one woman of Syrian descent, all of the vignettes Brenner shares are of descendants of European Jews seeking to bridge the gap from the old world to the new. The web site she recommends, JewishGen, does not even offer a search option for countries outside of Eastern Europe. The fascinating journey of the many diverse Sephardic communities, including anusim (those

forced to convert) and communities scattered after the Inquisition, merit attention as well.

REBECCA DREISINGER

New York, New York

g I appreciated Bayla Sheva Brenner’s article on Jewish genealogy, having experienced similar exhilaration when conducting my own family research. I’ve worked for several years teaching genealogy as a supplement to limudei kodesh classes, and students love the class and the journey of discovery. Our L’dor Vador class also helps my students contextualize everything else they learn, making it that much more meaningful. I encourage all Jewish day schools to incorporate genealogy into their curricula.

JEFFREY SCHRAGER

L'dor Vador Educational Services

Dallas, Texas

Holding the Arba Minim

g When I receive my Jewish Action, the first place I flip to is Rabbi Ari Z. Zivotofsky’s column. I enjoy the selection of topics and the accurate references. However, I think that the article, “What’s the Truth About . . . the Arba Minim?” (fall 2014) is misleading in its conclusion.

In the Mishnah Berurah 651:11, the Mechaber uses the word “l’chaber” when referring to holding the lulav to the etrog during the na’anuim. The Mishnah Berurah brings the story of Rabbi Menahem Recanati, which Rabbi Zivotofsky mentions. However, Rabbi Zivotofsky does not recount the story accurately. Rabbi Recanati points out that the day following his dream [which he interpreted as referring to the arba minim], he observed a Jew waving a lulav without the etrog, and he understood that all four species must

THE MAGAZINE OF THE ORTHODOX UNION www.ou.org/jewish_action

Editor in Chief Nechama Carmel carmeln@ou.org

Assistant Editor Rashel Zywica

Literary Editor Emeritus Matis Greenblatt

Book Editor

Rabbi Gil Student

Contributing Editors

Rabbi Yitzchok Adlerstein • Dr. Judith Bleich

Rabbi Emanuel Feldman • Rabbi Hillel Goldberg

Rabbi Sol Roth • Rabbi Jacob J. Schacter

Rabbi Berel Wein

Editorial Committee

Rabbi David Bashevkin • Rabbi Binyamin Ehrenkranz

Mayer Fertig • Rabbi Avrohom Gordimer • David Olivestone

• Gerald M. Schreck • Rabbi Gil Student •

Rabbi Dr. Tzvi Hersh Weinreb

Director, Design & Branding Carrie Beylus

Design Deena Katzenstein

Advertising Sales

Joseph Jacobs Advertising • 212.787.9400 arosenfeld@josephjacobs.org

Subscriptions 212.613.8146

ORTHODOX UNION

Executive Vice President/Chief Professional Officer Allen I. Fagin

Executive Vice President, Emeritus

Rabbi Dr. Tzvi Hersh Weinreb

Senior Managing Director

Rabbi Steven Weil

Chief Communications Officer Mayer Fertig

Chief Financial Officer/Chief Administrative Officer

Shlomo Schwartz

Chief Human Resources Officer Lenny Bessler

Chief Information Officer

Samuel Davidovics

President Martin Nachimson

Chairman of the Board

Howard Tzvi Friedman

Vice Chairman of the Board

Mordecai D. Katz

Chairman, Board of Governors

Henry Rothman

Vice Chairman, Board of Governors

Gerald M. Schreck

Jewish Action Committee

Gerald M. Schreck, Chairman

Joel M. Schreiber, Chairman Emeritus

©Copyright 2015 by the Orthodox Union. Eleven Broadway, New York, NY, 10004. Telephone 212.563.4000 • www.ou.org.

be held together; he does not note that there must be a slight space between the lulav and etrog.

Furthermore, Rabbi Shlomo Ganzfried, in the Kitzur Shulchan Aruch, says, “We turn the etrog over and holding it close to the lulav, with no separation between them, we wave them towards the four points.” Rabbi Ganzfried states, “shelo yehiyeh peirud beineihem.” He mentions this twice in this paragraph. Therefore, it seems to me, as I’ve observed since childhood, that one should have the etrog touch the spine of the lulav while holding them with both hands and waving the lulav.

Atlanta, Georgia

g I thank Rabbi Israel Robinson for his letter. In my article, I did cite a story regarding a dream of Rabbi Menahem Recanati. Rabbi Robinson is correct that my presentation of the story was imprecise, and in the story, as cited by the Taz, Be’er Hateiv and others, the guest, in fact, did not have an etrog at all.

In the article, I also quoted an idea attributed to the first Belzer Rebbe that when bringing the etrog in the left hand near the lulav in the right hand, a slight space should be left between them. Rabbi Robinson, while agreeing with the main premise of my article that the etrog and lulav should be in separate hands, suggests that the idea of leaving a space is specious and that the etrog should, in fact, touch the lulav

Permit me to elaborate on this specific point, which was addressed in a more limited manner in the original article. The Shulchan Aruch (OC 651:11) instructs one to “join the etrog to the lulav” (“lechaber”). He does not explicitly comment on whether they should touch or if there should be a space between them.

The Mishnah Berurah (651:48) simply reiterates the Shulchan Aruch’s instructions that the etrog should be “mechubar” to the lulav, without elaborating. The Kitzur Shulchan Aruch (137:1) twice says to bring the etrog near the lulav (“mekarvo”) so that there should not be a separation between them (“peirud beineihem”).

The Aruch Hashulchan (651:9) says that the two hands should be brought near each other for the purpose of joining the etrog with the other three species and, God forbid (“chalilah”), that they should be separated from each other. The Chayei Adam (148:7) writes similarly. It seems to me that the language used in all of these sources is ambiguous regarding whether the lulav and etrog have to actually touch. I think the import of the rulings is that in light of the fact that the etrog and lulav are in different hands, one can potentially hold them far apart, and thus these sources instruct that they should be held near one another. None of these sources explicitly state whether or not they should touch. On the other hand, the idea that I mentioned in my article, that they should be close but have a small space between them, is, as cited in my footnote, from the Kuntras Ha’Acharon (Ta’amei Haminhagim, sec. 792, p. 347). He states this explicitly, based on the Bel-

Meet Zvi Goldstein, a current MTA High School senior enrolling in Yeshiva University. Zvi is coming to Yeshiva University for the countless opportunities to engage with top Roshei Yeshiva and world-renowned faculty. With 150 student clubs, 16 NCAA sports teams and hundreds of activities, lectures and events throughout campus, YU has something for everyone.

Picture yourself at YU. #NowhereButHere

zer Rebbe. In contrast, the Kaf HaChaim (OC 651:106) quotes the Radvaz as saying that he was careful not to let his fingers separate between the lulav and etrog. Minhag Yisrael Torah (651:18) quotes opinions that the etrog should be touching the aravot, which are on the left side, or alternatively, that it should actually touch the lulav.

In summary, one fulfills his obligation whether the arba minim touch or are merely close to each other and both approaches have support in the sources.

g Professor Nathan Aviezer mentions three people in his article “Replying to Richard Dawkins” (spring 2015): Dawkins, Krauss and Hawking. All argue that science has eliminated a Creator. While the science involved is quite sophisticated, the arguments against a Creator are, in many respects, quite primitive, as we can see from the straightforward explanations provided by Professor Aviezer. (More detailed arguments are available in the literature.)

One might characterize Dawkins as a scientist, evolutionist, atheist and enemy of religion. He not only argues that religious belief is wrong, as would any atheist, but also that religious belief is an evil that needs to be eradicated.

[Religious] morality demands the presence of a great gulf between Homo sapiens and the rest of the animal kingdom. Such a gulf is fundamentally anti-evolutionary. The sudden injection of an immortal soul in the timeline is an anti-evolutionary intrusion into the domain of science . . . . You can kill adult animals for meat, but abortion and euthanasia are murder because human life is involved . . . . I think a case can be made that faith is one of the world’s great evils, comparable to the smallpox virus but harder to eradicate (Richard Dawkins, “When Religion Steps on Science’s Turf; The Improbability of God,” The Free Inquiry Magazine 18 [1998]).

And why is religion and faith so terrible? Because it values human life over other forms of life. The essential issue for Dawkins is the “sudden injection of an immortal soul,” without which humans are just another version of animals. Hence, euthanasia and infanticide and all sorts of other behaviors become perfectly rational and acceptable. We can poke fun at the almost childish “proofs” from science that there is no higher being. But belief in these proofs has no real impact on our lives. Rather, it is in the claim of a superior moral philosophy that would not only turn us into physical animals by definition, but would turn us into animals in behavior, where Dawkins and his like are to be strongly opposed.

MORRIS ENGELSON

Los Angeles, California

g Professor Aviezer asserts that “both Darwin and Rav Hirsch viewed evolution as the mechanism used by God to produce the animal kingdom.” He cites the fol-

Meet Miriam Libman, a current Yeshiva University senior. Miriam will be graduating with a degree in accounting and will begin her career at Ernst & Young in the fall. She is among the 90% of YU students employed, in graduate school or both—within six months of graduation.* With nearly double the national average acceptance rates to medical school and 97% acceptance to law school and placements at Big Four accounting firms, banks and consulting firms, our numbers speak for themselves.

Picture yourself at YU. #NowhereButHere

lowing (Collected Writings of Rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch, vol. 7, p. 264):

If the notion of evolution were to gain complete acceptance by the scientific world, Judaism would call upon its adherents to give even greater reverence to God, Who in His boundless creative wisdom, needed to bring into existence only one amorphous nucleus and one law of “adaptation and heredity” in order to bring forth the infinite variety of species that we know today.

However, this is not a verbatim quote from the Collected Writings. Rav Hirsch’s actual words are:

Even if this notion were ever to gain complete acceptance by the scientific world, Jewish thought, unlike the reasoning of the high priest of that notion, would nonetheless never summon us to revere a still extant representative of this primal form as the supposed ancestor of us all. Rather, Judaism in that case would call upon its adherents to give even greater reverence than ever before to the one, sole God Who, in His boundless creative wisdom and eternal omnipotence, needed to bring into existence no more than one single, amorphous nucleus and one single law of “adaptation and heredity” in order to bring forth, from what seemed chaos but was in fact a very definite order, the infinite variety of species we know today, each with its unique characteristics that set it apart from all other creatures.

Rav Hirsch adds that “this would be nothing else but the actualization of the law of ‘lemino,’ the law of species, with which God began His work of creation. This law of lemino, upon which Judaism places such great emphasis in order to impress upon

its adherents that all of organic life is subject to Divine laws, can accommodate even this ‘theory of the origin of species.’”

Nowhere in those words is an expression of agreement with the theory of evolution. The words only say that if the theory is accepted universally by the scientific community, one could look at it as describing a Divine wisdom utilized during the creation of animal species. This doesn’t mean that Rav Hirsch looked at the creation of the animal kingdom that way.

In the sentence just prior to those above, Rav Hirsch explicitly expresses his view on the veracity of the theory. After asserting that man’s attempts to explain natural laws “does not alter his moral calling,” Rav Hirsch tells us the following:

This will never change, not even if the latest scientific notion that the genesis of all the multiple of organic forms on earth can be traced back to one single most primitive, primeval form of life should ever appear to be anything more than what it is today, a vague hypothesis still unsupported by fact

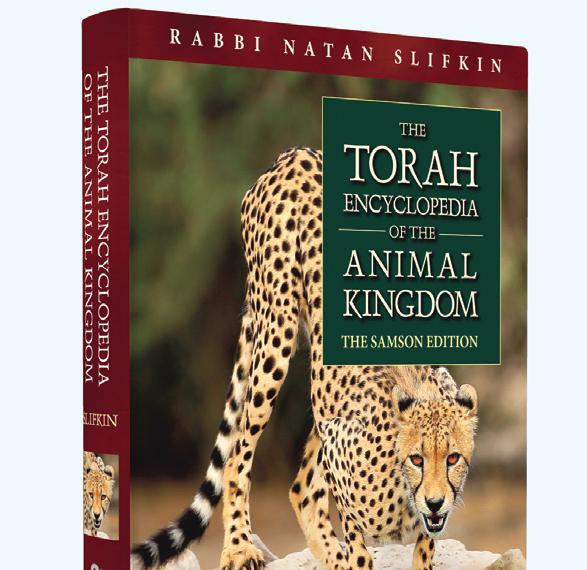

With such unequivocal skepticism, Rav Hirsch cannot serve as a source of support for the theory of evolution. Rabbi Natan Slifkin agrees that Rav Hirsch “personally did not believe in evolution” (www.ZooTorah.com/ controversy/BetechAffair.pdf).

Rav Hirsch’s intent was to offer a way for those who

supported the theory to pursue a Torah-observant life. However, he personally did not support it.

YISRAEL KASHKIN

Passaic, New Jersey

g Nowhere in my article did I state that Rav Hirsch accepted the theory of evolution. In fact, Rav Hirsch’s view on this matter is of minor importance because Rav Hirsch was not known for his expertise in science. The greatness of Rav Hirsch lay in the realm of Torah. Therefore, the important question—the question that I did discuss—is whether Rav Hirsch thought that the theory of evolution is consistent with Torah hashkafah Rav Hirsch gave a clear, affirmative answer to this question, writing that if the theory of evolution “were ever to gain complete acceptance by the scientific world . . . in that case, Judaism would call upon its adherents to give even greater reverence than before to the one, sole God . . .”

Rav Hirsch indeed thought that the theory of evolution was “a vague hypothesis, unsupported by fact,” a view shared by many scientists before Gregor Mendel’s genetic theory became known. In Rav Hirsch’s time, no one could explain heredity or mutations, the backbone of the modern theory of evolution.

Rav Hirsch viewed evolution (“if accepted by the scientific world,” which is the case today) as the mechanism used by God to produce the animal kingdom, writing that God “needed to bring into existence only one single, amorphous nucleus and one single law of heredity to bring forth . . . the infinite variety of species that we know today . . . .”

This point of view, known as “theistic evolution,” is accepted by many Orthodox Jews, including me.

g Reading “From Homemade to Store-Bought” by Carol Ungar (spring 2015), I noticed that the author states, “Another important job was making rosl, a now-almost-unknown pungent crimson-colored beet broth that was considered the height of gourmet cuisine in Eastern Europe.”

I have been making horseradish this way for forty years now (though I did not know it was called rosl until I read the article). Making this “beet juice” on Purim each year starts my Pesach preparations. Far from being forgotten in my family, making this homemade horseradish is an annual event for me, and my family and friends look forward to my horseradish each Pesach.

DENNIS HALPIN

Houston, Texas

YU enables you to grow and deepen your understanding of, and commitment to, Jewish life at a top tier college while discovering your passions and beliefs and forming lasting friendships. With student programs across our campuses and worldwide, YU takes a global approach to learning, education and values, creating a full college experience.

A YU education is not out of reach. Over 80% of students received help with tuition last year, with over $45 million in scholarship and financial aid awarded.

Picture yourself at YU. #NowhereButHere

Martin Nachimson

There was much hand-wringing when the Pew Research Center’s “A Portrait of Jewish Americans” was first released in October 2013. We all bemoaned the devastating intermarriage rates among the non-Orthodox (at 71.5 percent), and the slow but steady erosion of American Jewish life.

On the positive side, the Pew report affirmed what many of us already knew: American Orthodoxy has experienced a remarkable resurgence. With our high birthrate and very low intermarriage rate, our community is vibrant, strong and growing.

And yet, the report also made it very clear that we have our own problems to contend with. While our retention rate is impressive at 83 percent, it means that nearly 20 percent are dropping out of religious life.

We invest an average of $300,000 to educate a child Jewishly (including camps, the gap year in Israel, et cetera). With such an extraordinarily high investment, a loss of close to 20 percent is nothing short of alarming. What are we doing wrong?

This, in fact, relates to a question we at the OU face all the time. Should we invest our limited dollars in keeping Orthodox youth committed or in reaching those who know little or nothing about their heritage? Do we focus on kids who resent the restric-

tions of Shabbat or do we focus on those who have never experienced a Shabbat at all? Whose needs are more pressing? Which is a better “investment” yielding better “returns”?

Obviously, we cannot evaluate the sacred work of saving neshamot on a spreadsheet. We cannot put a price tag on keeping our young people in the fold, on ensuring we produce committed Torah leaders, on working to build a strong and vibrant future for Torah Judaism.

And yet, we must make decisions. At NCSY, the world’s most successful Jewish youth organization, we have historically recognized the need for both in-reach and outreach. Indeed, as one NCSY leader recently told me: “There are very few kids on any religious level who don’t need NCSY.”

Why do yeshivah kids need NCSY? As Rabbi Micah Greenland, international director of NCSY, puts it, there is the “magic of NCSY.”

Every summer, we bring more than 1,000 kids to Israel on summer programs. More than 600 of them are, in fact, yeshivah kids who attend NCSY Kollel (where my grandson is planning to go this summer), Michlelet, GIVE and other such programs tailored to their specific needs. Recently, in fact, we have begun exploring more ways to transport the “magic” of our wildly successful summer programs for yeshivah kids into year-round programming. We are also expanding our single-gender programs. Just recently, 4G, an all-girls’ program in the Midwest, hosted NCSY’s first-ever allgirls’ Shabbaton.

But making inroads in reducing the drop-out rate means we must continue to follow NCSYers as they graduate high school and reach young adulthood. Each year, roughly 2,500 students graduate from Modern Orthodox high schools across North America. Between seventy and eighty percent of them end up

attending secular college campuses. In the uber-questioning, uber-liberal atmosphere of the college campus, religious students are exceptionally vulnerable to grappling with, and yes, even losing, their faith.

We help NCSYers transition into college life by connecting them to Jewish life on campus. Our regional offices around the country keep in close contact with twelfth graders, helping them with their choices and guiding them to Jewish resources on campus. One such resource is a program I am particularly proud of: the Heshe and Harriet Seif Jewish Learning Initiative on Campus (JLIC), currently found on twenty-two campuses throughout North America. JLIC places rabbinic couples on campus to help students navigate the various challenges of campus life. Due to the enormous need for such a program, JLIC is growing. Reaching a lot more than just NCSY alumni, JLIC programs and community leadership involve nearly 4,000 Jewish students each year. Through our JLIC programs, run with the invaluable assistance of our national partner, Hillel—the Foundation for Jewish Campus Life, Orthodox kids have Torah role models who not only organize Chanukah parties and Megillah readings on campus, but also serve as confidants at a particularly sensitive time in their lives.

Do our in-reach programs work? When I hear that a yeshivah kid who was about to give it all up is now a leader in an NCSY region, or when I hear that a beit midrash on a secular college campus is full with students studying Torah each night, I think, “Yes, it is working.”

But until the drop-out rate in our community is at zero percent, we cannot afford to sit back and relax. Until then, we have much work to do. g

By Gerald M. Schreck

Our editorial board thought long and hard before going ahead with this issue’s somewhat controversial cover story, “When Leaders Fail: Healing from Rabbinic Scandal.” Members of the board were concerned: Could we handle this delicate subject matter with the right combination of erudition and empathy? Could we address the issue from all angles— psychological, emotional, spiritual and halachic? We knew, however, that when Rabbi Yitzchak Breitowitz, a maggid shiur at Yeshivat Ohr Somayach in Jerusalem and the former rabbi of the Woodside Synagogue in Silver Spring, Maryland, accepted our invitation to write about the topic, it would be handled intelligently, compassionately and sensitively.

Why did we decide to cover this disturbing, even demoralizing, topic despite the angry letters that will inevitably follow? Because it’s necessary. When a scandal occurs involving a rabbinic leader, the psychological and spiritual repercussions are profound. Oftentimes, congregants and community members even those who were

not closely connected to the rabbi in question are deeply traumatized. There is pain and a sense of betrayal. Some may begin to question their faith. Some may begin to reject the idea of rabbinic authority. Make no mistake: rabbinic scandals can and do result in a form of communal trauma.

In the days of the Beit Hamikdash, there were rituals to help the community cope with the trauma of sin. In his wonderful new book, Covenant & Conversation on Leviticus: the Book of Holiness, Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks describes the ritual of the two goats, the sair l’azazel and the sair laShem, that were part of the Yom Kippur service. One of the reasons for this “immensely powerful and dramatic ceremony” was so people would “feel and symbolically see the sins carried away to the desert, to no-man’s land.” The ritual was therapeutic. It gave people hope; it conveyed to them in a very concrete way that sin whether on a personal or on a communal level does not stain one forever.

Judaism, Rabbi Sacks writes, “is a religion of hope, and its great rituals of repentance and atonement are part of that hope. We are not condemned to live endlessly with the mistakes and errors of the past.”

These same core ideas of teshuvah, recovery, and spiritual rehabilitation come up again and again in Rabbi Breitowitz’s wide-ranging and deeply thoughtful essay. Sometimes leaders may fail, but that should not cause us to succumb to hopelessness or despair.

Nowadays, we have no Beit Hamikdash, and we can no longer experience the cathartic eradication of aveirot via the sair l’azazel; so how are we to cope with the consequences of sin both on

a communal and on a personal level?

The Torah, of course, provides an answer. In Parashat Naso, Rashi asks the following question: “Why is the topic of the nazir juxtaposed to the topic of sotah?” He famously responds:

“To teach you that anyone who sees a sotah in her destruction should refrain from wine.”

When one observes the disgrace of the sotah, he should commit to become a nazir. Why? Because witnessing the consequences of aveirah could, God forbid, help “normalize” sin in one’s mind and desensitize him to depravity.

“Become a nazir,” the Torah tells us. In other words, erect even greater, taller, more fortified fences so that you yourself don’t falter.

What should our personal and communal response be when we hear about a rabbinic or communal leader who stumbles? Perhaps we should respond by doing our best to strengthen ourselves spiritually, by recommitting ourselves to learn even more Torah and do even more mitzvot, and by deepening our own resolve to live a more authentic religious life.

We are truly honored to publish Rabbi Breitowitz’s nearly 6,000-word essay, which many of us on the editorial board feel, myself included, is one of the most important articles we have published in the pages of this magazine.

It is our hope that Rabbi Breitowitz’s stirring words will help bring some level of peace, hope and psychological and spiritual closure to those among us still suffering from scandals that have affected their synagogues and their communities. g

Eli

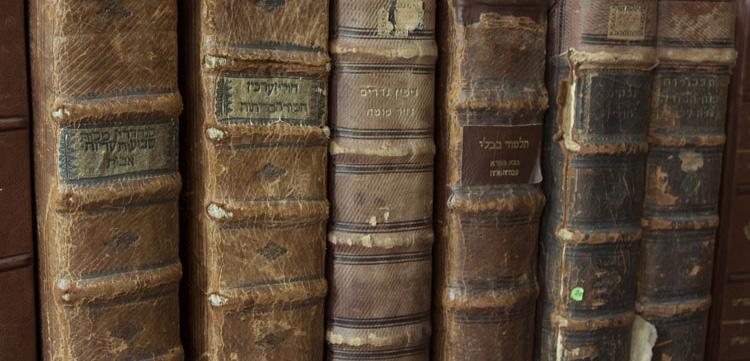

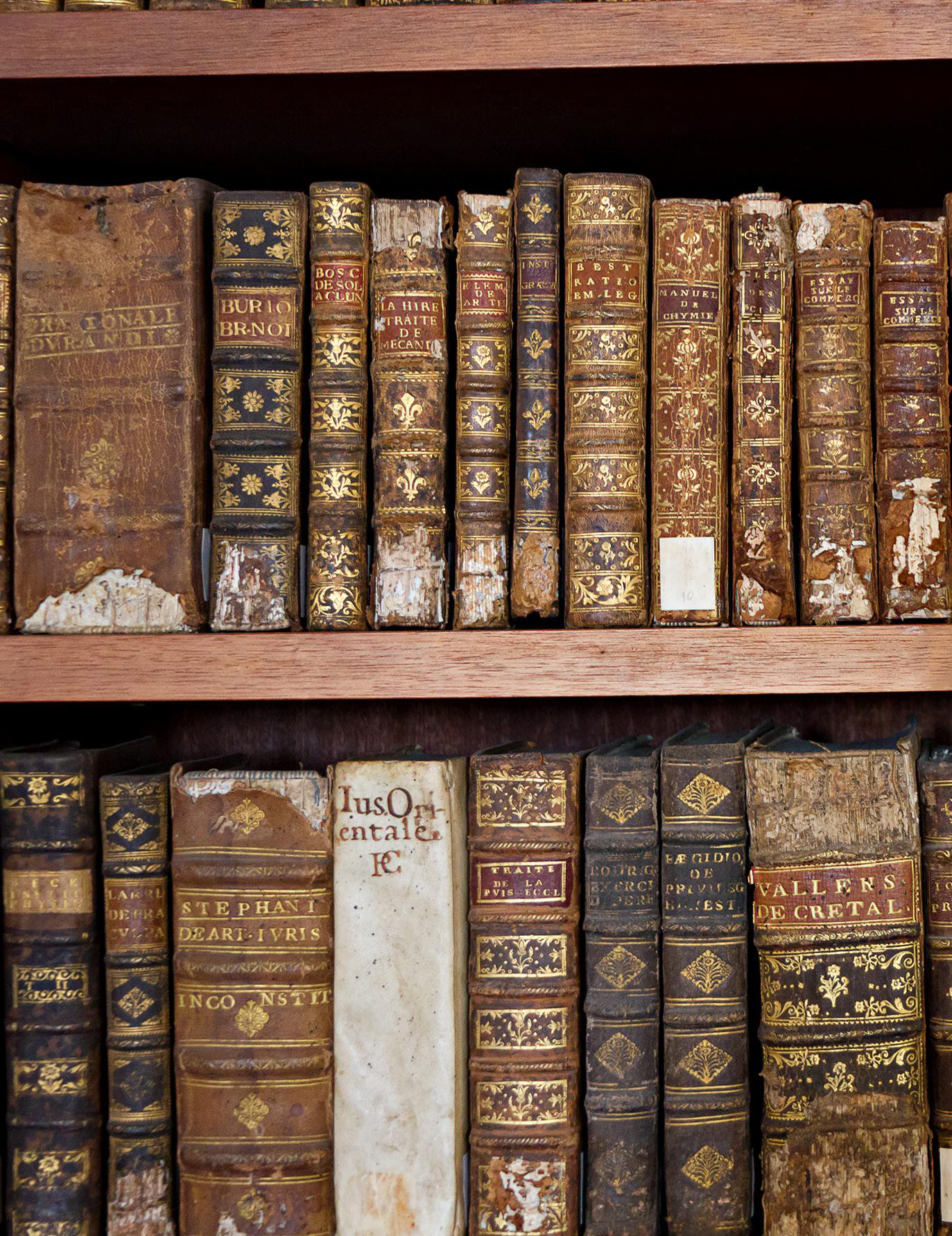

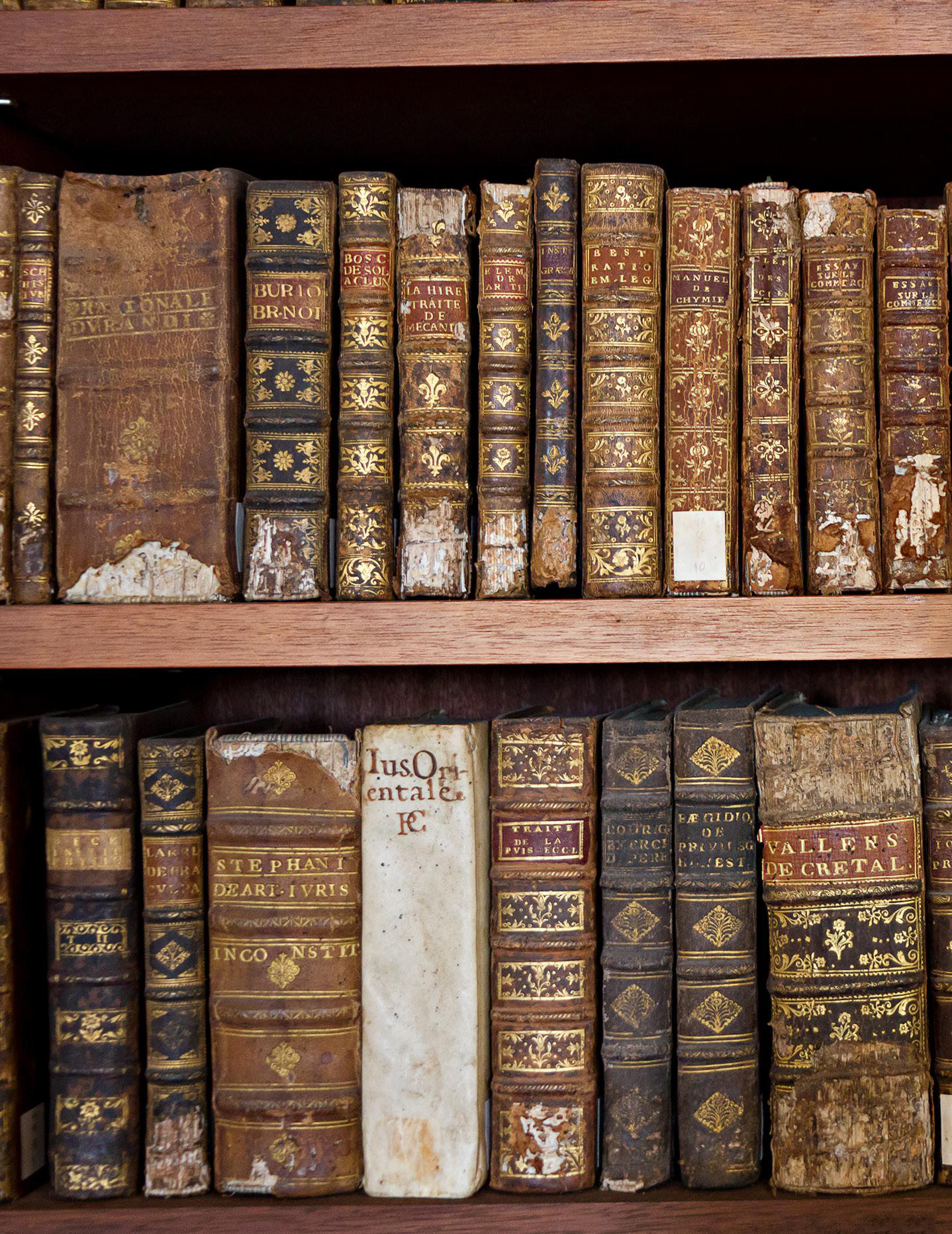

t all began with one book.

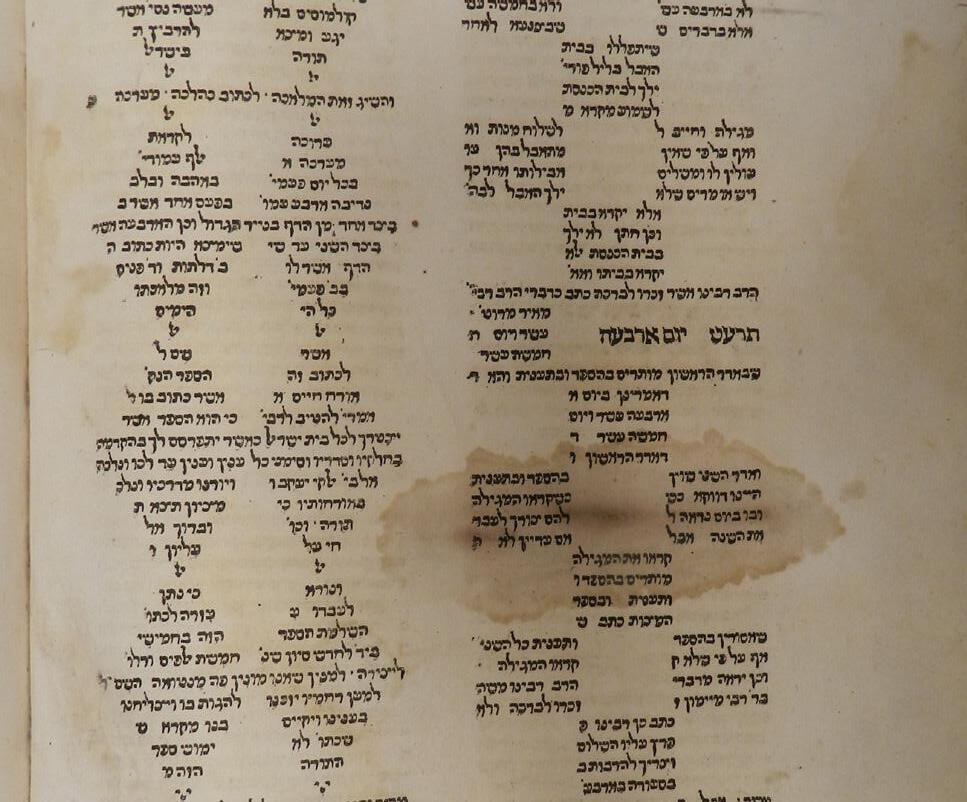

A Gemara actually—a 1735 edition of Tractate Moed Katan, a gift from my beloved father-in-law, Dr. Eric Offenbacher. Ultimately, this Gemara led to my developing a passion for collecting antique sefarim, a hobby I have been very involved in for the past decade.

What is it about old sefarim that fascinates me? The books themselves speak. They tell the story of Hebrew printing. They tell the stories of their long-deceased owners. Take, for example, the Gemara that got me started on my journey. It was printed in a city whose Jewish community dates back to the thirteenth century—Frankfurt am Oder (not to be confused with the more well-known city of Frankfurt am Main), sixty miles east of Berlin and situated on the Oder River. Three separate editions of the Talmud were printed there between 1697 and 1739. When the edition I own was printed,1 the printing house was owned by Professor Johann David Grillo, a non-Jew, as noted in the Gemara’s title page. (In those days, it was common for gemaras to be printed in printing houses owned by non-Jews.)

Eli Genauer is a businessman, community volunteer and book collector living in Seattle, Washington, where his family has lived for over 100 years. He has written extensively about his collection both online and in scholarly journals, and delivered a talk on his research at the 16th World Congress of Jewish Studies.

TheGemara had originally belonged to my wife’s

The 1735 edition of Moed Katan, printed in Frankfurt am Oder, that started the author on his journey of collecting antique sefarim.

great-great-grandfather, the well-known antiquarian dealer and Jewish philanthropist Selig Goldschmidt (1828-1896). A resident of Frankfurt am Main, Mr. Goldschmidt was a supporter of Rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch.2 A lifelong philanthropist, he shied away from honor, and only asked that he

merit to be buried next to his rav. A visitor to the Jewish cemetery in Frankfurt today will notice four tombstones set apart from the rest—those of Rav Hirsch and his wife, and those of Selig Goldschmidt and his wife.

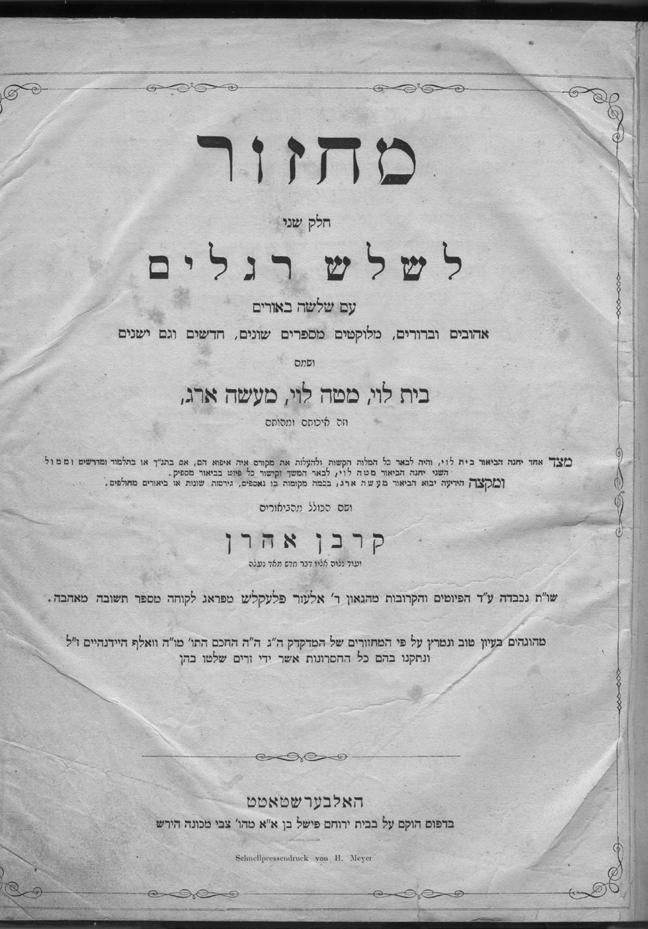

Another one of my treasures is a machzor for the Shalosh Regalim printed in Halberstadt, Germany, in 1860 and owned by Reuben (Robert) Goldstein. The machzor, one of only

A machzor for the Shalosh Regalim owned by Reuben (Robert) Goldstein, who, along with his wife, Anna, and their eight children were the first permanent Jewish settlers in Alaska. They arrived in Juneau in the early 1880s, a few scant years after the town was established.

fourteen Hebrew books ever printed in Halberstadt, 3 features the following inscription: “Reuben Goldstein, Juneau, Alaska, February 4, 1900.” Apparently, Reuben Goldstein, his wife, Anna, and their eight children were the first permanent Jewish settlers in Alaska. They arrived in Juneau in the early 1880s, a few scant years after the town was established. Prior to settling in Alaska, Goldstein had operated businesses in Montreal, Winnipeg, Seattle and other cities.

The books themselves speak. They tell the story of Hebrew printing. They tell the stories of their long-deceased owners.

He started out in Juneau in the fur trade business but then discovered that no mineral claim had ever been filed for the twenty-nine acres of land lying underneath the commercial business district of Juneau. The Alaska State Library records that:

In 1886, [Reuben Goldstein] filed a mineral claim on the town site of Juneau.4 The public discovered this fact in 1888 when the Secretary of the Interior awarded a little over 29 acres of Juneau to Anna. The citizens became so enraged over the prospect of losing their homes and property they called a public hearing and decided to either hang Goldstein or throw him in the bay

[newspaper clipping from San Francisco Call, Nov. 28, 1888]. The case was taken to the General Land Office (Goldstein vs. the Town Site of Juneau) where it was decided in favor of the town. From there it went to the Supreme Court and then referred to the Interior Department. The claim was determined valid. The land was thought to be worth between $900,000 and $1,000,000 and apparently Goldstein settled for a sum of money instead of the land.

Goldstein passed away in 1900.5 Since there was no Jewish cemetery in the area, his body was sent 1,000 miles by boat to Seattle, Washington, where he was buried in the cemetery of Chevra Bikur Cholim. The fact that the family, went to such lengths to bury him in a Jewish cemetery says much about their connection to the Jewish community, despite their living in the Jewishly isolated city of Juneau. Interestingly, despite the judgment against the town, the townspeople seem to have held no grudge against the family as one of the children, Issie Goldstein, served as mayor of Juneau for three terms. Can’t you picture Reuben Goldstein davening from this machzor in the Alaskan town of Juneau around the turn of the twentieth century?

Traveling to the other end of the Pacific Ocean, we meet the Lubliner Rebbe of Bnei Brak, Rabbi Avraham Eiger (19142002), whose signature appears in a Masechet Nedarim I own that was printed in Shanghai in 1943. Many tractates of the Talmud, along with other scholarly books, were printed in Shanghai for students of the Mir and Slobodka yeshivot who sought refuge there during the Holocaust.6

The edition I own bears the inscription “shayach l’habachur Avraham Eiger” (this book belongs to the young man Avraham Eiger). Rabbi Avraham Eiger, who was born in Warsaw in 1914, was a direct descendant of the famed Talmudist and legal authority Rabbi Akiva Eiger of Posen. Rabbi Avraham Eiger studied with his cousin, the Admor of Lublin, Rav Azriel Meir Eiger, who in 1939 encouraged him to leave Poland. He joined a group led by the Amshinover Rebbe that eventually made it to Lithuania. There he was one of the few thousand fortunate Jews who received transit visas issued by the heroic Japanese vice consul in Lithuania, Chiune Sugihara. Along with Yeshivas Mir, Rav Avraham spent much of the war in Shanghai, and most likely it was there that he acquired the Gemara under discussion. After the war, he married, and along with his wife, made aliyah. He settled in Bnei Brak in 1955.7 This edition of the Gemara, printed while the Holocaust was raging in Europe and learned by refugees whose lives were shattered by war and deprivation, attests to the spiritual resilience of the Jewish people. Even though their lives were in upheaval, the refugees knew that gemaras had to be printed, that Torah study had to persist.

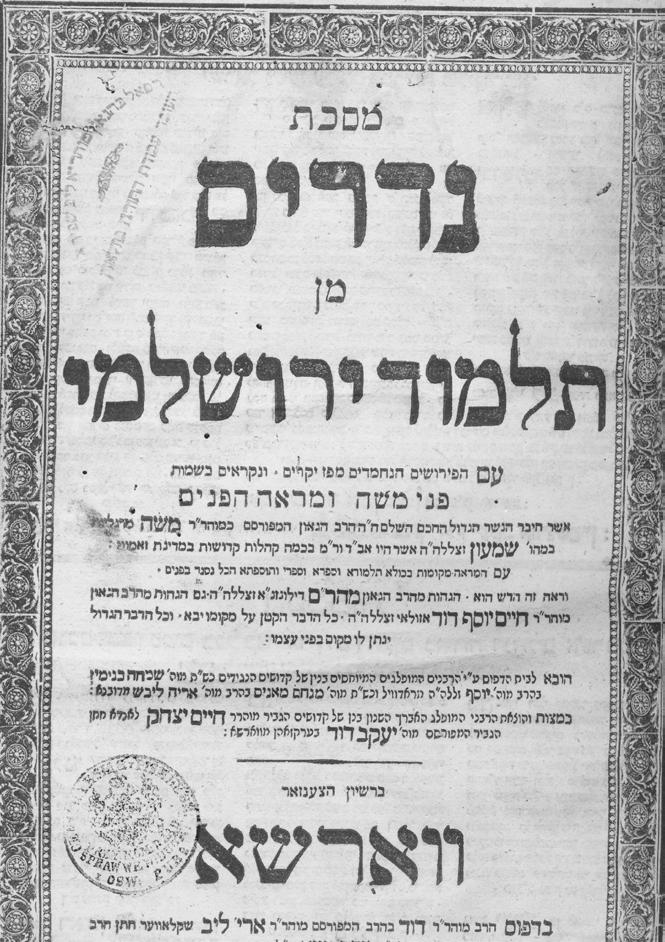

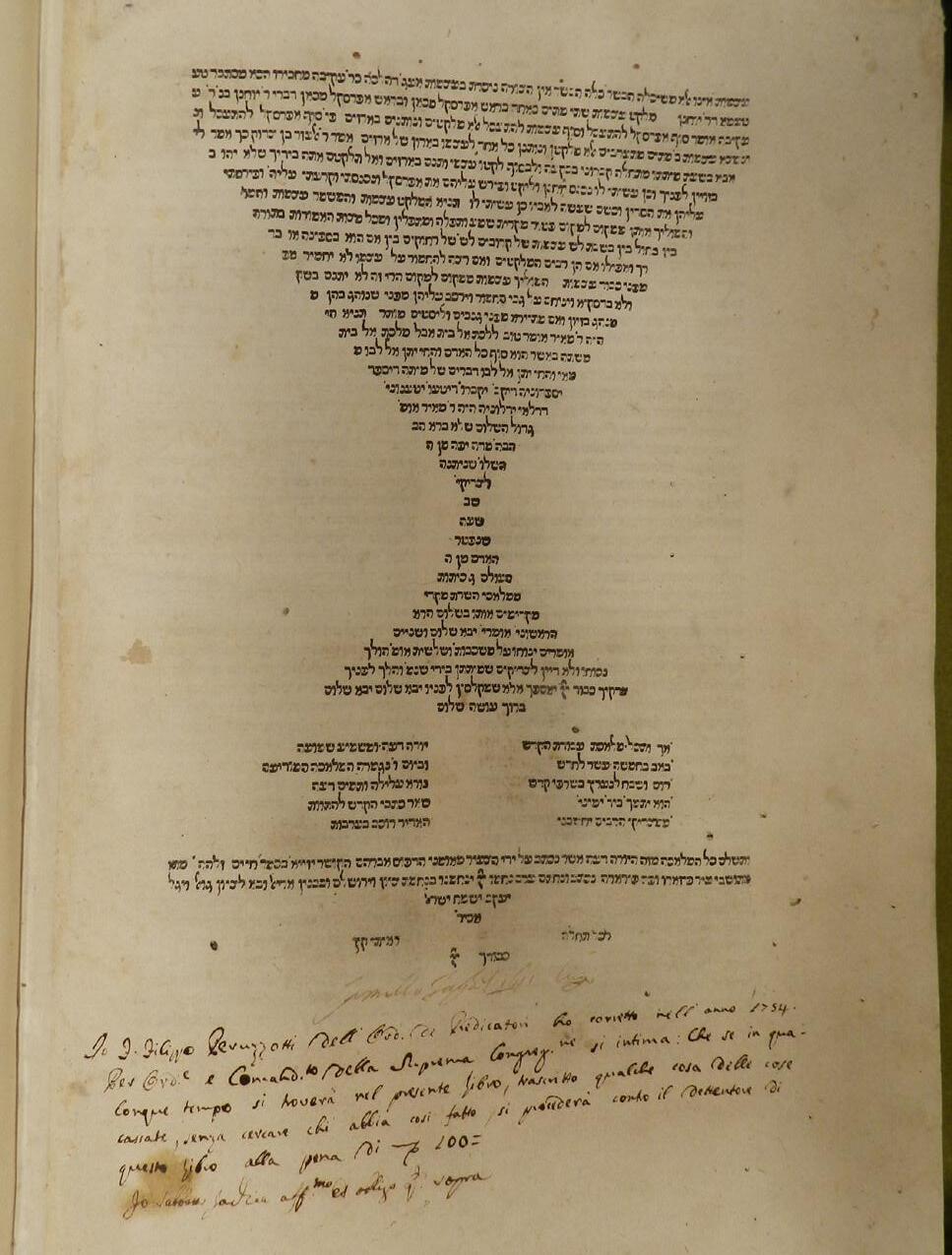

Another cherished sefer in my collection is the Jerusalem Talmud, Tractate Nedarim, printed in Warsaw in 1837.

The stamp on the title page indicates that it belonged to Rabbi Raphael Shapira (1837-1921), rosh yeshivah of Yeshivas Volozhin from 1899-1915, “Ha’oveid avodas haTorah b’Volozhin” (who is engaged in the service of the Torah in Volozhin). Rabbi Shapira was the son-in-law of Rav Naftali Tzvi Yehuda Berlin (the Netziv). He married the Netziv’s daughter, Sara Rasha, when he was fifteen. Their daughter Lipsha eventually married Rabbi Chaim Soloveitchik, making Rabbi Shapira the son-in-law and father-in-law of two of the most preeminent scholars of Lithuanian Jewry.

I bought this particular sefer because of the special relationship my family had with Rabbi Shapira. My maternal grandfather, Rabbi Avraham Rosen, arrived in New York on March 18, 1922, leaving my grandmother and three small children behind in Poland. When he got to Ellis Island, he was detained for a few weeks because he had to appeal to the US government for permission to enter.8 The government allowed clergy into the country even without citizenship papers, but officials needed to verify that his rabbinic ordination was valid. The officials had never come across Rabbi Raphael Shapira, the name of the rabbi who conferred semichah to my grandfather. Finally, they consulted with

Masechet Nedarim printed in Shanghai in 1943. Many tractates of the Talmud along with other scholarly books were printed in Shanghai for students of the Mir and Slobodka yeshivot who sought refuge there during the Holocaust.

Listen to Eli Genauer speak about sefarim collecting at www.ou.org/life/history/savitsky_genauer/.

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6.

FOCUS, FOCUS, FOCUS. Try to narrow down the area you would like to pursue. For example, some people like old Haggadahs; others prefer first editions of Chassidic books or early printed gemaras , and still others antique siddurim.

USE A BIBLIOGRAPHY SITE such as hebrewbooks.org, which has thousands of books. You can actually see what the old sefarim look like, including ones that go back to the 1500s. Similar to other researchers, many collectors rely on Google—both in Hebrew and English—to get started in researching subjects. Bibliography listings of major Jewish libraries such as the Israel National Library can be especially helpful.

SHOP ONLINE! Believe it or not, eBay has a multitude of offerings of old sefarim. I check the listings there frequently. Nowadays, acquiring old books is much easier than before in that many books are available online.

MAKE IT PERSONAL Check the libraries of friends and family. You would be surprised at what you find.

GOING ONCE, TWICE… It is now much easier to access auctions of old sefarim. Collectors often participate in online auctions conducted by large Jewish auction houses in New York and in Israel. Some popular sites and auction houses are JudaicaUsed.com, virtualjudaica.com, Kestenbaum & Company, Asufa and Kedem auction houses.

SPREAD THE WORD When people know you collect old sefarim , they let you know when they come across something.

Jerusalem Talmud, Tractate Nedarim, printed in Warsaw in 1837. The stamp on the title page indicates that it had once belonged to Rabbi Raphael Shapira, rosh yeshivah of the Volozhin Yeshiva from 1899 to 1915.

one of the prestigious rabbis in New York at the time and asked about the legitimacy of rabbinic ordination from Rabbi Shapira. The rabbi answered, “That’s who I got my semichah from.” My grandfather and his family were spared from the Holocaust because of Rabbi Shapira. It’s not surprising that I feel a very special connection to this sefer. Investigating sefarim and their owners is a pastime that takes me around the world and through the centuries—in a virtual sense. I have “met” fascinating individuals whose sefarim now grace my library shelves—from simple Jewish laborers to prominent rabbis, from Jewish communities ranging from Warsaw to Shanghai. Each and every one of the sefarim I own has a story or stories behind it. Each and every one is a piece of Jewish history, a tangible link to our rich and illustrious past. g

Notes

1. Rabbi Raphael N. N. Rabinowitz in his classic book on the early printed editions of the Talmud, Maamar al Hadpasat HaTalmud (History of the Printing of the Talmud), ed. A.M. Habermann (Jerusalem, 2006), 117, decries this particular edition because it lifted many innovations from the 1720 Frankfurt am Main edition, ascribing these additions to their own scholarship.

2. Information from both family tradition and from a book about Selig Goldschmidt written by his son, Meier Selig Goldschmidt. It was translated into English and distributed to members of the family.

3. Yeshayahu Vinograd, Otzar Hasefer HaIvri, under “Halberstadt.”

4. See www.juneau.org/library/museum/index.php.

5. Reuben Goldstein also holds the distinction of having a valley in Juneau named for him: Goldstein Gulch.

6. Printing the Talmud: From Bomberg to Schottenstein, ed. Sharon Liberman Mintz et al. (New York, 2006), 292.

7. An obituary for him on the web site Dei’ah VeDibur in 2002 notes that in Shanghai “Rabbi Avraham Eiger was widely recognized as a ben aliyah. It was known that he would check all of his food for bugs by sunlight.”

8. I assume my grandfather was referring to some kind of visa allowing him to emigrate to the US.

BY BAYLA SHEVA BRENNER

Expert collector Rabbi Eliezer Katzman, a consultant and appraiser of Judaica and Hebrew books for Kestenbaum & Company, has also worked for Sotheby’s, Christie’s and other auction houses. Rabbi Katzman, who lives in Brooklyn, New York, has appraised the collections in the Rare Book Room of the Mendel Gottesman Library of Hebraica/Judaica at Yeshiva University, the collection in the Jewish Public Library of Montreal and the rare books and manuscripts of the Annenberg Research Institute in Philadelphia. He has published many scholarly articles on Jewish history, Jewish law and bibliography and serves as associate editor of Yeshurun, one of the foremost scholarly biannual publications on Jewish law, history and bibliography.

Jewish Action: Tell us about your extensive library of rare sefarim and how you became involved in collecting.

Rabbi Eliezer Katzman: I own an eclectic collection of about 10,000 sefarim. Originally I bought sefarim for my own learning. If I had to prepare a shiur and needed a sefer, I couldn’t go hunting for it in shul late at night. [But] my interest in rare sefarim began with my father, Rabbi Asher Katzman,

who was a rosh yeshivah at Yeshiva Torah Vodaath. He had between 30,000 and 40,000 sefarim. I inherited the bug. A lot of the sefarim I have are from him; others I bought on my own.

JA: Where do you keep your vast collection?

RK: I have sefarim filling my garage, shed and basement. A young collector called me once, lamenting his shalom bayis problems; there was no room left

Bayla Sheva Brenner is senior writer in the OU’s Communications and Marketing Department.

in his house. He had run out of shelf space and began piling sefarim on all of their chairs. His wife complained that there was no place to sit. He solved the problem by purchasing the Otzar HaHochma digital library that has approximately 71,000 sefarim scanned in page after page. He told me it saved his marriage.

JA: What are the most important factors when assessing a sefer’s market value?

RK: The first factor is obviously age. The rarest books are known as incunabula—books printed before 1501, when printing was in its infancy. Jewish incunabula are especially rare. For example, a Jewish book printed in 1492 is worth considerably more than a non-Jewish book from the same period. The Jewish people studied their books throughout the exiles, so complete, intact Jewish books are extremely rare. Jewish books were often burned over the centuries—another reason they are rare. There were books printed right before the Holocaust, most of which were destroyed by the Nazis. Those that survived are very valuable.

Currently, I write the descriptions of the sefarim and manuscripts featured in the Kestenbaum & Company catalogs. The catalogs describe the importance of each sefer,

when it was printed, its condition and what it’s worth. If a famous person wrote marginal notes in a sefer, it increases the sefer’s worth. A sefer that once belonged to Rav Moshe Feinstein that contains his notes is worth much more [than a sefer without notes]. Rabbi Baruch Frankel-Teomim, known as the Baruch Taam [1760-1828], the father-in-law of Rav Chaim Sanzer, wrote notes in the margins of all his sefarim. Recently, Rabbi Baruch Shimon Schneerson, the son-in-law of Rabbi Dov Berish Weidenfeld, the Tchebiner Rav, published a collection of the Baruch Taam’s marginal notes on various sefarim.

There are two categories of rare Jewish books: printed sefarim and manuscripts. Many people view a letter or manuscript by a Chassidic rebbe or the Chofetz Chaim as intrinsically holy. [Nowadays,] a handwritten letter by the Chofetz Chaim . . . is worth approximately $20,000. Even a typed letter with only his signature may be worth a few thousand dollars.

[To command a high price,] a sefer has to be complete; a book missing a title page is worth substantially less. It should be in good condition (not wormy). Noncollectors often assume that older books are in worse condition than later ones. But that’s not necessarily the case. After 1860, chemicals were added to paper. That’s why books from later periods often have brittle pages. The paper used in earlier books rag paper remains fresh.

Another factor that determines the value of a sefer is the element of mystique. For example, a siddur was published in Amsterdam with the kabbalistic commentary of Rabbi Yeshaya Horowitz, known as the Shelah HaKadosh. There’s a haskamah (letter of approbation) in the siddur from the Bach, who writes that anyone who prays from this siddur will have his prayers answered. Collectors pay a lot of money for it. The Shelah probably meant that anyone who studies his commentary and adheres to the suggestions will be answered. But people will pay between $20,000 and $30,000 for the siddur.

First editions of Chassidic sefarim also command high prices. Chassidim like to have a connection to their rebbes and their dynasties. In the town of Slavuta, Ukraine, Rabbi Moshe Shapiro was the town’s rabbi and printer. He was a descendant of the famous Chassidic rabbi, Rabbi Pinchas of Koretz, a disciple of the Ba’al Shem Tov. Chassidim view any sefer printed by the descendants of his family as imbued with inherent kedushah. For example, a Tehillim printed in Slavuta could go for $5,000. They are in great demand, especially by Skverer Chassidim, who are willing to pay top dollar for them.

JA: How do collectors go about finding rare sefarim?

RK: When I was growing up, there were still sefarim stores on Manhattan’s Lower East Side that sold many out-of-print sefarim. There was a time you could get [these works] at a relatively low price. In Eretz Yisrael today there’s a rapidly growing industry of book dealers selling antique books and manuscripts. There are a lot of sheimos and old sefarim found in many of the old houses in Yerushalayim. I know a book dealer in Israel who finds out when a home is being demolished and makes a deal

The rarest books are known as incunabula—books printed before 1501, when printing was in its infancy. Jewish incunabula are especially rare, says Rabbi Eliezer Katzman, an expert in Hebraica and Judaica. Seen here is an example of Hebrew incunabula that is very valuable. Colophon of Arba’ah Turim: Orach Chayim, published in Mantua, Italy, by Abraham Conat, ca. 1476. Images courtesy of Yeshiva University, Mendel Gottesman Library.

with the builder to give him entry to the attic before the structure is torn down. He’s discovered many ancient sefarim and letters this way. [He recently discovered] precious items owned by Rabbi Zundel of Salant, who lived in Jerusalem in the mid-1800s. In 1948, when the Old City was destroyed, a number of his sefarim survived and were preserved by members of his family. A recent auction featured letters and articles that belonged to him.

JA: With the advent of the Internet and digitization, does actively building up one’s physical library really make sense?

RK: In the past, if someone needed certain sefarim, he had to go to four or five different libraries. Some were found only at Oxford University or the British Museum in England or at the National Library of Israel at Hebrew University in Jerusalem. In America, some of the researchers use the library at Yeshiva University and the Jewish divisions at The New York Public Library and at Harvard University. Harvard has one of the largest collections of Hebrew books—about 60,000 to 70,000 works. The Library of Congress also has a large collection. Nowadays, you can go to a site called Hebrewbooks.org, which has about 50,000 digitized sefarim. One can also purchase CDs containing thousands of sefarim. However, there is a tremendous advantage to having access to a physical sefer. Not everything is on the Internet, and some people enjoy holding a 300-yearold sefer in their hands; it enables them to feel a greater connection to the author and the time period.

JA: What do you think of those who collect sefarim primarily as a hobby, but not for personal study?

RK: They say of collectors in general that it’s the excitement of the hunt [that drives them].

One of the foremost collectors of rare Jewish books is Jack Lunzer, a retired industrial diamond merchant in London, who has one of the most valuable collections in the world—some 13,000 Hebrew works. In 2009, Sotheby’s exhibited a portion of his massive library, which included the most prized work of his collection, the first complete printed Shas, known at the Bomberg Shas. It previously belonged to King Henry VIII. As is well known, the king didn’t have any male heirs and wanted to annul his marriage so that he could remarry and attempt to have a son. [In order to legitimize his divorce,] an advisor informed him that he may find a solution in the Talmud. He ordered a copy of the first Shas, printed in the early 1500s. He received a deluxe edition, bound especially for the king. Eventually, he gave it to the Church of England. Mr. Lunzer wanted to own this Shas and was initially unsuccessful in convincing the church to sell it. He bought the original charter of Westminster Abbey and persuaded the church to sell him the Talmud in exchange for the charter.

JA: Do you have any favorite sefarim?

RK: One of my favorites is the mussar sefer Marpe Lashon (Healing of the Tongue) by Rabbi Raphael HaKohen, rabbi of Hamburg, Germany. In his youth, Rabbi Chaim Volozhin was one of his disciples. He is famous for his responsa and chiddushim on the Talmudic tractates of Kodshim. The sefer, printed in 1790 in Altona, Germany, covers topics such as teshuvah, humility, tzedakah, Yom HaDin and various other topics. Although I already owned subsequent editions, as the sefer had been republished in Vilna and after that, in America, I decided to buy the original for two hundred dollars. Later, when comparing the editions, I observed that the Vilna edition didn’t have the lengthy introduction found in the original, as well as divrei Torah from the author’s son and son-in-law. After further comparison, I noticed that the chapters on tzedakah and humility, which were around twenty pages in the original, were only two pages long in the reprinted versions.

This sefer was one of Rabbi Aharon Kotler’s favorite sefarim; he quoted from it many times in his lectures. He also had difficulty trying to make sense of what the author was saying due to these incomplete chapters. I approached Rabbi Binyamin Zeilberger, rosh yeshivah of Bais HaTalmud in Brooklyn at the time, who had reprinted the sefer from the Vilna edition. I showed him the original edition and told him about the missing fifty pages. In 1987, he printed the full version of the sefer from my copy, thanking me in the introduction for giving him the original text. This shows the importance of

obtaining original editions and comparing them to subsequent editions.

JA: Are there many collectors such as yourself out there?

RK: There used to be a chevrah of collectors that included both rabbis and ba’alei batim who possessed large private libraries. Rabbi Shlomo Freifeld, zt"l, owned a large library. I assessed it after he passed away. There’s a story told that he and Rabbi Berel Perlow, an avid collector of newly published sefarim, saw each other at Biegeleisen JS Books, a popular sefarim store in the Borough Park section of Brooklyn. Rabbi Freifeld put his arm around Rabbi Perlow and quipped, “Reb Berel, we’re like two drunks in a bar.”

They say the Gerrer Rebbe, known as the Imrei Emes, also had the bug; he had one of the world’s largest libraries. Much of his collection disappeared during the Holocaust. He was once in Krakow in an old sefarim shop and climbed up a ladder to the top shelf, hunting for rare sefarim. He came down covered in dust. The owner of the store asked him, “Rebbe! Iz dos nisht ah yetzer hara ozoi vi alla yetzer haras?” (Is this not a yetzer hara like all the other yetzer haras?) He responded, “You’re right, but it’s a kosher yetzer hara.”

JA: Were you ever subject to significant danger while acquiring sefarim?

RK: I personally wasn’t, but I know people who were. My father-in-law, Rabbi Chaim Uri Lipschitz, former editor of the Jewish Press, was friends with Rabbi Harry Bronstein, who founded the Al Tidom Association, established to help Russian Jewry struggling behind the Iron Curtain. As an experienced mohel, he traveled to Russia many times to perform brissim and to train mohels there. During these trips, various people came to him, asking him to smuggle their manuscripts out of Russia. One of these requests came from Rabbi Yitzchok Isaac ben Dov Ber Krasilschikov, also known as the Gaon of Poltava. He gave Rabbi Bronstein his manuscript on Rambam while he lay in the hospital on his deathbed. He also made him promise to publish his monumental twenty-volume commentary on the Yerushalmi he had worked on. [An extraordinary talmid chacham, Rabbi Krasilschikov authored a massive commentary on the Yerushalmi in Moscow between the years 1952 and 1965. This was, of course, illegal in Communist Russia.] Because of the illegal brissim, Rabbi Bronstein was arrested and tortured by the KGB. He subsequently suffered a heart attack. He miraculously survived and returned to America. He worked hard for many years to obtain the manuscript on the Yerushalmi. [In 1980, the first volume of Rabbi Krasilschikov’s commentary on Tractate Berachot was finally published. The printing of Rabbi Krasilschikov’s colossal commentary on the

Colophon of Arba’ah Turim: Yoreh De’ah, published in Mantua, Italy, by Abraham Conat and completed in Ferrara by Avraham ben Hayim, ca. 1477. The handwritten portion on the bottom of the page was written by a censor.

Yerushalmi is an ongoing effort, currently overseen by Rabbi Chaim Kanievsky.]

JA: What is the future of the sefarim industry?

RK: It continues to grow. There were more sefarim printed in the last few years than in any prior period. Moshe Biegeleisen of Biegeleisen JS Books stated recently that in just three weeks he got eighty new sefarim. It’s much easier to publish books with computers. One can do a lot by himself at home.

JA: How do current sefarim reflect contemporary Orthodox life?

RK: There are many more sefarim published in English today than in previous generations, obviously with the many [Anglo] consumers in mind. In Eretz Yisrael numerous scholarly sefarim are constantly being published, as well as the more popular sefarim containing stories and parashah-related insights that families could share at the Shabbos table. The most popular books of this genre are written by Rabbi Yitzchok Zilberstein, Rav Elyashiv’s son-in-law. They are best sellers both in Israel and in America. I’m sure that, despite all of the new technologies, frum Jews will continue to value and utilize the actual printed word, especially on Shabbos and yom tov. A sefer is a more personal, hands-on connection to previous, current and future generations of Torah scholars. g

Five Hundreds Years of the Hebrew Book From the Beginning of Printing Until the Twentieth Century

By Akiva Aaronson Feldheim Publishers New

York, 2013

231 pages

Reviewed by Gil Student

The Internet is only the latest, and probably not the last, of many information upheavals due to technology. An important change began over 500 years ago with the invention of the printing press. This new method for mass-producing books quickly altered the political and religious face of Europe. Jews, traditionally devoted to literacy and study, were early adopters of printing technology and suffered less upheaval than their Christian counterparts.

In a fascinating and richly illustrated new book, People of the Book: Five Hundreds Years of the Hebrew Book From the Beginning of Printing Until the Twentieth Century, Akiva Aaronson traces important Jewish developments

along the path, from Rashi’s Torah commentary, the first dated Hebrew book (Italy, 1475), through the Survivors’ Talmud published in 1948.

In the mid-1400s, Johannes Gutenberg invented the mass production of books through the printing press. Metal letters—movable type—were assembled onto a page. Ink made from vegetable oil rather than water, which does not stick to metal, was applied to the typeset page. Paper, which had been recently invented, was placed into a press in which the typeset page covered with ink was pushed onto the paper. With this combination of inventions, the new technology of the printing press could produce books in large volume. While some lamented the loss of the art of handwritten books, their apprehension could not stop the spread of inexpensive, mass-produced books. In explaining all this and more, Aaronson includes delightful and enlightening illustrations of early printing presses and books.

Printing was developed in Germany, but Jews were excluded from the industry by the local guilds. However, when the technology made its way to Italy, Spain and Portugal, Hebrew printing exploded. The first fifty years of printing, from 1450 to 1500, are called the period of incunabula. During that time period, there were twenty-nine active Hebrew printing shops, nearly one-fifth of all known printers at the time. With a literate and learned population, the Jewish community enjoyed a high demand for affordable books.

Each printer had to carve out his own letters what we call fonts today but regional characteristics can be easily seen. Ashkenazic printers used more square letters and Sephardic printers used rounder letters, each following the practice of scribes. Hebrew vowels proved a unique challenge; additional metal type had to be included for each vowel. Numbering of pages appeared in the early 1500s—the first Hebrew book with page numbers was the 1509 Constantinople edition of Rambam’s Mishneh Torah.

The house of Soncino was one of the earliest and most important Hebrew printers, and its name still resonates

today, over 500 years later. The first Hebrew book published by a member of the Soncino family was the Babylonian Talmud, Tractate Berachot, in 1483, likely the first printed volume of the Talmud. While the volume lacked page numbers, it contained Rashi’s commentary on the inner column of the page and Tosafot on the outer column. This format remains to this day.

In the short time between the invention of the printing press and the Jewish expulsion from Spain in 1492, Hebrew printers in Spain published many books, including the first printed Haggadah and both Rashi’s and Ramban’s Torah commentaries. In approximately 1491, Rabbi Yaakov Baruch ben Yehudah Landau’s Sefer HaAgur was published in Naples. This was the first Hebrew book published in its author’s lifetime.

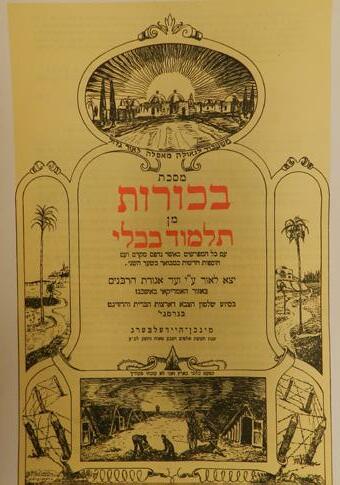

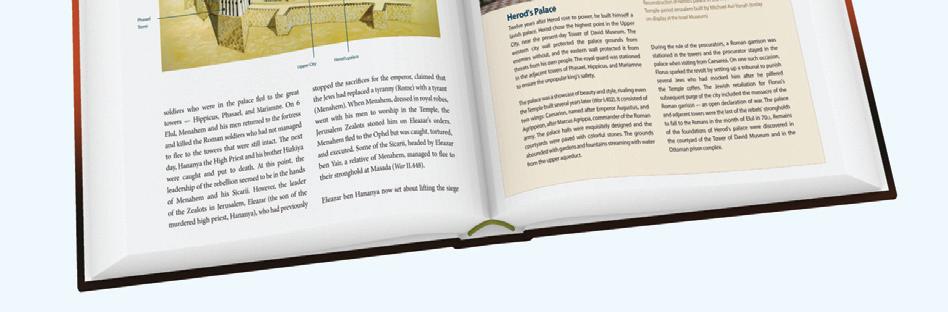

Title page of Masechet Bechorot, published by the Agudath HaRabanim in the American Zone in Germany with the help of the US Army and the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee, in 1948. Known as the “US Army Talmud” or the “Survivors’ Talmud.”

In the first half of the 1500s, printing ended its pioneer phase and became an established industry. Trade developed, texts became standardized and printing flourished. In 1516, Soncino’s greatest

competitor began publishing in Venice. Daniel Bomberg, a wealthy Christian, used the most accurate texts and the finest materials to print what quickly became the standard edition of basic Jewish texts. He published the first Tanach, the Hebrew Bible, with chapters and verses (and with the books of Shmuel and Divrei HaYamim each divided in two).

With the exception of prayerbooks, the Pesach Haggadah is the most published Jewish book, with about 5,000 editions having appeared since printing was invented.

His Mikra’ot Gedolot, the Rabbinic Bible, is still the basis for what is used today. And between 1520 and 1523, Bomberg published the first mass-produced, complete set of the Babylonian Talmud, which introduced pagination that

continues to this day.

Aaronson continues telling the stories of great books and printers throughout the centuries. Sulzbach, Roedelheim and Vilna are only some of the important places where publishers made Jewish history. In the early 1700s, stereotyping was developed, in which plates were made of complete pages. This not only reduced the cost of printing, but also allowed for easier reprinting of subsequent editions since the plates could be stored. The Industrial Revolution in the mid1800s brought with it mechanical iron presses that were faster and easier to use.

With the exception of prayerbooks, the Pesach Haggadah is the most published Jewish book, with about 5,000 editions having appeared since printing was invented. The earliest known printed Haggadah is from Spain, printed around 1482, with no vowels, commentary or

illustrations. The first printed Haggadah with commentary was Rabbi Yitzchak Abarbanel’s Zevach Pesach, published inConstantinople in 1505, not long after the author’s death. The Prague Haggadah of 1526 was the first Haggadah printed in Northern or Eastern Europe. It includes vowels and more than sixty illustrations.

Aaronson tells the story of the sefer with enthusiasm and color. He discusses censorship, halachic controversies and more. His story takes us into the twentieth century with Feldheim and Shulsinger Brothers in New York and the Soncino Press of London, concluding his historical survey with the publications immediately after the Holocaust. Technology has since grown in leaps and bounds. Digital printing has become fairly common and Internet storage of books, including publication directly online, is growing. The history of the sefer continues. g

By Yitzchak Breitowitz

In Bernard Malamud’s novel The Natural, an extremely talented ball player, Roy Hobbs, is discovered to have taken a bribe to throw a baseball game. He is barred from baseball for life and all his records are expunged. In a poignant final scene, a young boy turns to Roy with pleading eyes and says, “Say it ain’t so.” But Roy cannot. He simply weeps.

In many ways, this novel is a metaphor for the loss of innocence, for the sadness of discovering that those we thought were paragons of virtue and greatness are flawed, for the sense of betrayal as we are cast adrift by those in whom we put our trust and faith. In many ways, this metaphor aptly describes a crisis that is spreading within the Torah community.

We live in the era of the fallen hero—indeed the tragic hero who is destroyed by the fatal flaw that lies within. In all walks of life, people whom we admired have disappointed us with their failures and weaknesses. We have become disillusioned and cynical. Unfortunately, even within the Torah camp, leaders in whom we placed our trust have betrayed us. And while the overwhelming majority of rabbis, teachers and spiritual mentors perform their tasks with integrity and commitment— and we should never make the mistake of condemning the many because of the sins of the few—many of us have lost faith in the very people who are supposed to inspire us in our faith. We see them engulfed in sexual scandals, child abuse, political intrigue, bribery and fraud. Some are accused of direct wrongdoing, others of cover-up and dissembling. Many have lost faith not only in those who are supposed to transmit Torah but, to some degree, in the goodness and morality of the Torah itself. God’s name and His glory quite literally have been besmirched, the very definition of chillul Hashem.

In some ways, this cynicism and loss of faith may be a greater tragedy than even the very real pain suffered by innocent victims (a pain that I certainly do not want to minimize in any way). The tragedy of cynicism presupposes that everything is tainted. Nothing good is real. No one is sincere. Everything is a gimmick. Everyone is a charlatan and a faker. And what is the use of pretending otherwise? These attitudes suck up hope the way a fire sucks up oxygen. They destroy spiritual strivings. They destroy hope for the future. They engender passivity and bitterness and ultimately become a self-fulfilling prophecy of defeatism and hopelessness. It is precisely at this juncture that we have to take stock and articulate some basic simple principles.

The great Rabbi Moshe Chaim Luzzatto writes in the

introduction to the Mesillat Yesharim that he will be restating obvious principles that are known by all but are often forgotten in the pressures of the moment. And while his claim of a lack of innovation may be untrue, I humbly admit that this article will contain few chiddushim (novel thoughts). Sometimes, however, there is value in restating the obvious. Let me start with two basic points.

First, do not condemn the Torah. Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel once famously remarked that it is a big mistake to judge Judaism by the behavior of Jews. The Torah is greater than any one person or institution. The fact that we do not always live by its ideals cannot be an indictment of the ideals themselves.

Second, we live in an imperfect world. People are not all white and pure, nor are they all black and tainted; people come in an infinite variety of grays. The fact that we—all of us—are capable of great sin does not exclude the possibility, and the reality, that we are capable of great good. And indeed, the good that we accomplish is not forfeited by the evil that we perpetuate. As a result, we ourselves must avoid the arrogance of smugly sitting in judgment over the weaknesses and failures of others and, chas v’shalom, even gleefully rejoicing in the “downfall of the mighty” (an attitude that is quite evident on the Internet).1 Demonizing the other can sometimes be a convenient excuse to avoid our own cheshbon hanefesh (personal accounting), one that is necessary to make our communities safer, and ultimately, holier. Thus, whatever mussar I may offer, and it may occasionally sound harsh, does not come from a place of moral superiority or self-righteousness. It is not intended as a personal attack on others. I offer these thoughts as an introspective reflection directed to myself and to any others who may be interested—an enumeration of some things we can do as a community, a listing of pitfalls to be avoided and some assorted thoughts of comfort and chizuk as we face difficult and painful times.

First and foremost, the Jewish community has a solemn responsibility to make its sacred spaces—shuls, mikvaot, yeshivot, day schools and camps—safe. If people have been

Since April 2010, Rabbi Yitzchak Breitowitz has been a maggid shiur at Yeshivat Ohr Somayach in Jerusalem and rav of Kehillat Ohr Somayach. Prior to his family’s aliyah, he was the rabbi of the Woodside Synagogue in Silver Spring, Maryland, and associate professor of law at the University of Maryland.

harmed physically, emotionally or financially, their pain must be acknowledged and addressed. They should not be dismissed as troublemakers. Our children and our adults must be protected, and those who legitimately seek to protect those in need should not be disparaged or ignored. And if recourse must be had to the secular authorities and the legal process, then so be it. Any attempt to invoke the law of mesira to shield serious abuse is misguided, if not downright evil. This is axiomatic.2

This is not the problem of any one specific synagogue or institution. It is a problem that the entire community must face. There is an element of collective guilt in the fact that we as a community allowed these abuses to occur, did not respond to the problems that were brought to our attention, ignored them, swept them under the rug. If a corpse is found near a city, the elders of the city as representatives of the community are guilty for failing to take steps that would have ensured the safety of the victim. They too are designated “spillers of blood” and they too need atonement. (See Devarim 21:1-9 and Mishnah Sotah 9:6.) We are precisely in the position of those elders.

But fixing the problem, truly fixing it, will take more than simply ensuring that bad behaviors will not reoccur. There is a history that needs to be addressed. Communities and individuals have suffered profound psychological dislocations that cannot be ignored. People have a deep sense of being violated—physically and emotionally. There is pain, anger, rage and confusion. These feelings do not just disappear by making improvements and simply moving on as if nothing ever happened. A person who suffers a vicious amputation by someone he or she admired and even loved is not restored by a prosthesis. The victims—past and potential—have voices that must be heard and respected, concerns and feelings that deserve articulation. There are, of course, laws of lashon hara, and I am not necessarily envisioning full public exposure in the media (though this happens anyway), but at least within the limited community of responsible leadership, those who were harmed must be able to speak.3

Both rabbis and laity must be educated as to what behaviors are normal and acceptable so that they (we!) will be able to evaluate whether a given behavior is outside that norm. Otherwise, people literally do not even know whether they

have been wronged; they are the proverbial child who cannot even ask the question. To the degree consistent with halachah, the appropriate standards should not be pronouncements issued ex cathedra. The offended and vulnerable populations must have a significant role in formulating these standards. This is important because they have first-hand knowledge of the problems and abuses. But equally important, such participation partially restores their sense of respect and dignity that had been so ruthlessly stripped away. It is our responsibility to “have their backs,” so to speak, and we must convey to and convince the victims that we are there for them—a daunting task since we have dropped the ball so many times in the past.

At the same time, however, one must look at the total picture. What needs to be fixed must be fixed, but do not throw out the good with the bad. We must be careful not to exaggerate. First, the halachic requirements of judging people favorably and giving them the benefit of the doubt continue to exist. These halachot have not vanished (although a school or shul may take provisional temporary steps to prevent possible endangerment or abuse in the interim investigative period). Second, portraying the rabbinate or Torah educators, or both, in a uniformly negative light when the vast majority of rabbis and Torah teachers perform their tasks with excellence and

As one moves further and further away from the cultivation of a private intimate relationship with the Almighty, as one's persona becomes the dominant aspect of his inner reality, one's spiritual life becomes increasingly empty.

commitment is not only a scurrilous and libelous attack on dedicated people who try to serve Hashem and His people with great devotion, but is a tremendous disservice to Am Yisrael, causing many to lose respect for Torah leaders and for the Torah itself.

While even a single victimized child or adult is one victim too many, and while we as a community must try to vigorously uproot any vestige of these improprieties, the solution is not the tarnishing of a noble institution. In the superheated atmosphere of the Internet, everyone is guilty until proven innocent and indeed quite often, is guilty even after being proven innocent. In this world of hyperbole, gossip, unsubstantiated rumors and personal vendettas, a casual reader might conclude that the rabbinate, and indeed the entire Torah community, has run amuck, is utterly devoid of any semblance of morality and is nothing less than the modern incarnation of Sodom and Gomorrah. This does not reflect reality, and it is important that our children know this.

Moreover, we must avoid using the personal sins of individual rabbis as a basis for attempted overhaul of halachah. For example, many are now calling for significant changes in the time-honored halachic procedures of how female candidates for conversion should immerse in the mikvah. Without addressing the substance of these proposals, it is clear that they have nothing to do with the mikvah scandals that have erupted. As far as I know, there

have been no scandals involving these procedures and changing them would have no effect on the wrongdoing that actually took place. Calls for this type of reform are offering “solutions” to nonexistent problems and do little to fix the existing ones. They are subtle attempts to disparage halachic tradition and halachic authority. Proceed with caution.

Most of the recent scandals—not all—involve abusive or exploitive treatment of women. Many, not all, of these problematic encounters started quite innocently in the context of counseling, spiritual advice and the like. What is needed is a code of ethics, a “fence” of sorts that would prevent benign encounters from escalating. No better code of ethics exists than the Shulchan Aruch itself. Counterintuitively, a rabbi may fail to apply the Shulchan Aruch to himself (and after all, who is going to correct him?). Even with the most noble of intentions, this is an enormous mistake with devastating consequences.

There are very good reasons why halachah prohibits the seclusion of a man with a woman and, in response to the plethora of litigation based on sexual harassment, these reasons have been appreciated even by secular culture.4 The laws of yichud (seclusion) and negiah (affectionate physical contact) reflect the reality that sexual attraction is a very potent, powerful and somewhat uncontrollable force, and we have the responsibility to ensure that certain lines are not crossed.5 The Shulchan Aruch generally prohibits flirtatious or intimate talk between men and women, even if the technical strictures of yichud and negiah are not violated.6 Emotionally intimate talk can easily lead to improper physical contact, or at the very least, emotional manipulation. I do not mean to draw a pejorative comparison between Modern Orthodoxy and the Chareidi/Yeshivah/Chassidic world. I am painfully aware that scandals have emerged from all camps. Nor am I suggesting the desirability of total gender separation. For good or for bad, that is not the world we live in, and it is important for women to have a rav with whom they can consult and interact in a comfortable way. But overly familiar, flirtatious, suggestive behavior is playing with fire. It can easily get out of hand, and even when it does not, it can be easily misinterpreted. Such behavior is dangerous to a rabbi’s reputation, can lead to grossly inappropriate behavior and can irretrievably damage the relationship with his own spouse. Comments about a woman’s looks, weight, attractiveness or desirability are simply inappropriate under virtually all circumstances. Any personal reference that makes a woman

uncomfortable should not be said at all. The dedicated male seminary teacher who wants to have an intense tete-a-tete with a student to help her discover the infinite richness and beauty in her soul may or may not be starting off with the best of intentions, but he is heading down a path of destruction either way.

A rabbi might justifiably feel that his intentions are leshem Shamayim, that his sole desire is to help a person in need, that he is beyond the baser instincts that may drive “regular” people astray. This was precisely the mistake of Shlomo HaMelech, the wisest of all men. He too thought he was above temptation. He too thought that the Torah’s rules against accumulating wealth and excessive wives should not apply to him because he was in no danger of losing his bearings and straying. And he discovered that we are all vulnerable and weak, that we can all fail, and that is the very reason we all need to adhere to the bright lines of the halachic system.7

We live in the era of the fallen hero, indeed, the tragic hero who is destroyed by the fatal flaw that lies within. In all walks of life, people whom we admired have disappointed us with their failures and weaknesses.

Chazal tell us “Do not fully trust yourself until the day of your death” (Avot 2:4). Yochanan served as a righteous kohen gadol for eighty years, and yet at the end of his life became a Sadducee.8 Shlomo HaMelech was the wisest of all men and thought he was immune to temptation, yet he succumbed. On the holiest day of the year, Yom Kippur, the kriyat haTorah of Minchah is the parashah dealing with forbidden sexual relationships—adultery, incest, bestiality. Given the exalted state we reach on that day, such a reading seems an odd choice. Should we not focus on something more spiritually edifying and inspirational? The answer is, that is exactly the point. At the very height of our spirituality, at the apex of our accomplishments, we need to be acutely aware of our capacity to fail. We can never take our spirituality as a given. As righteous as we may think we are, indeed, as righteous as we may in fact be, we can easily slip and need to be vigilant. When we as rabbis are arrogant, smug and overconfident in our religiosity or Torah knowledge, and feel a sense of personal superiority over the people we have pledged to serve, it is precisely at that point that we will fail. “Pride comes before the fall” (Mishlei 16:18).

The story is told about an extremely pious individual who took every conceivable precaution to eradicate chametz from his home on Pesach.9 As he sat at his Seder joyous and confident that he had completely fulfilled the Torah’s commandments, he sees to his utter shock that