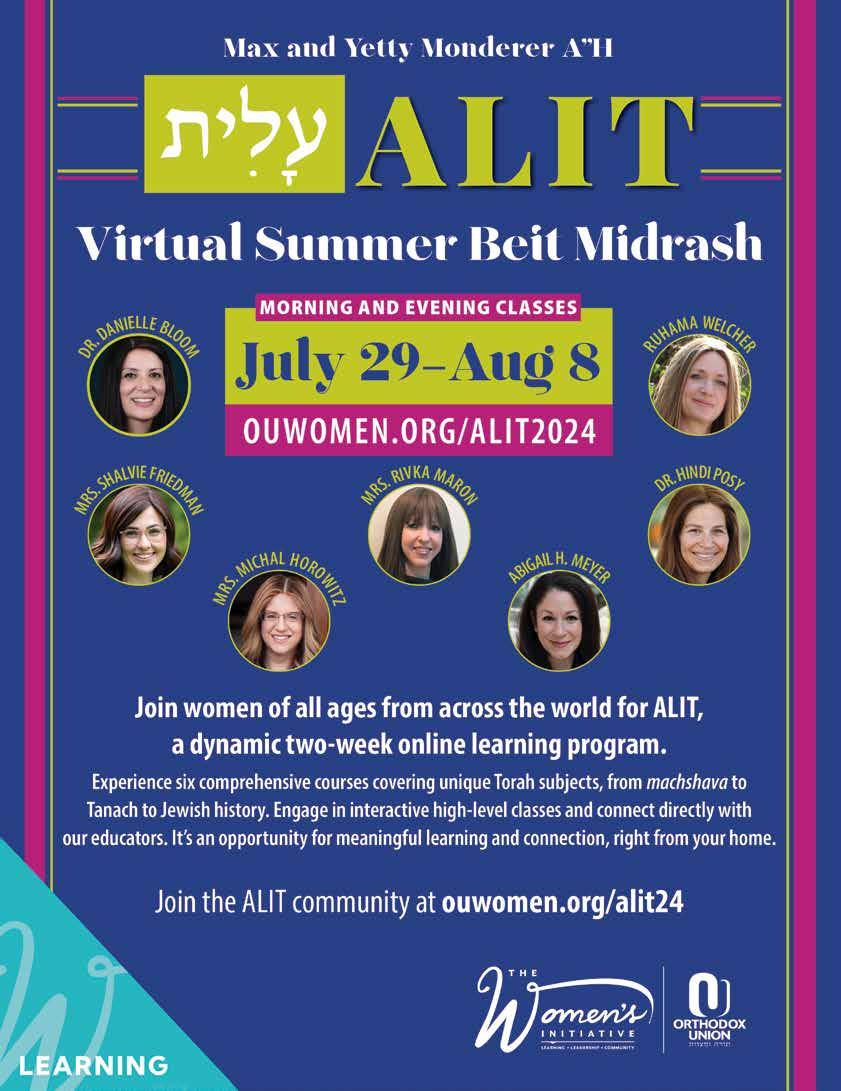

Summer 5784/2024 Vol. 84, No. 4 • $5.50 Religion

AVAILABLE NOW FOR PRE-ORDER The English translation of the incredible One Day In October is now available for pre-order exclusively from www.korenpub.com

FEATURES

COVER STORY:

Religion on the Battlefield What Does the Torah Have to Say about Military Ethics?

By Rabbi Dr. Shlomo Brody

Questions from the Battlefield Rabbi Dovid Bashevkin speaks with Rabbi Yosef Zvi Rimon

On the Frontlines with Rabbi Shlomo Sobol As told to JA staff

The Holiest Work A Conversation with Miriam Neumark Shalev of the IDF Chevra Kadisha’s Women’s Unit By Leah R. Lightman

A Different Kind of Battlefield

High Fashion, Higher Standards By Sandy Eller 14 16 21 30 32 38 49 52 54 68

Meet Israel’s warriors on the home front—IDF wives who exhibit extraordinary faith while juggling housework, jobs and toddlers

By Carol Green Ungar

PERSONAL ESSAY

Choosing Life: The Blessing of Caring for My Father By Viva Hammer

JUST BETWEEN US

The Dog that Doesn’t Bark By A. Schreiber

JEWISH THOUGHT

Modesty in the Modern Age: A Symposium By Bracha Poliakoff; Shifra Rabenstein, as told to Barbara Bensoussan; Josepha Becker; Dr. Zipora Schorr; Rabbi Reuven Brand; Alexandra Fleksher; Rabbi Yisrael Motzen; Gila Ross; and Rebbetzin Ruchi Koval, as told to Barbara Bensoussan

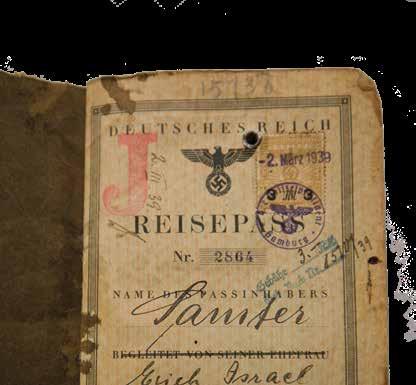

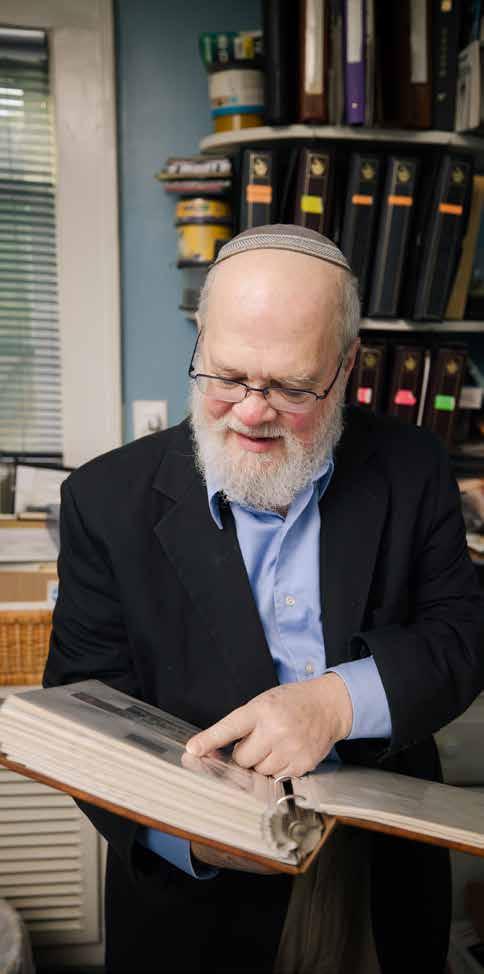

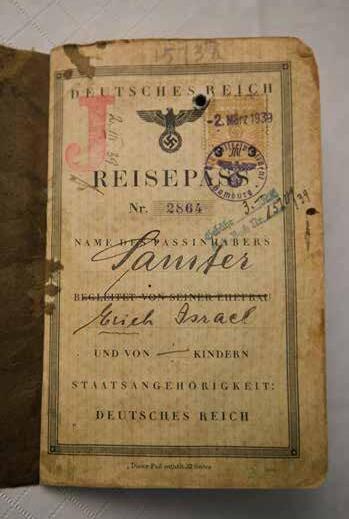

PHOTO ESSAY

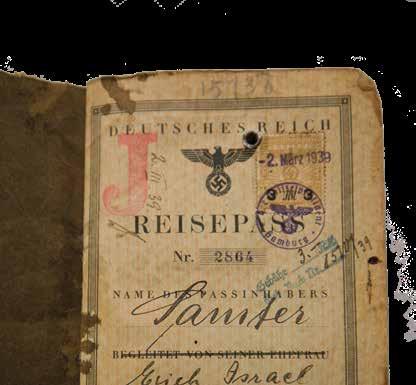

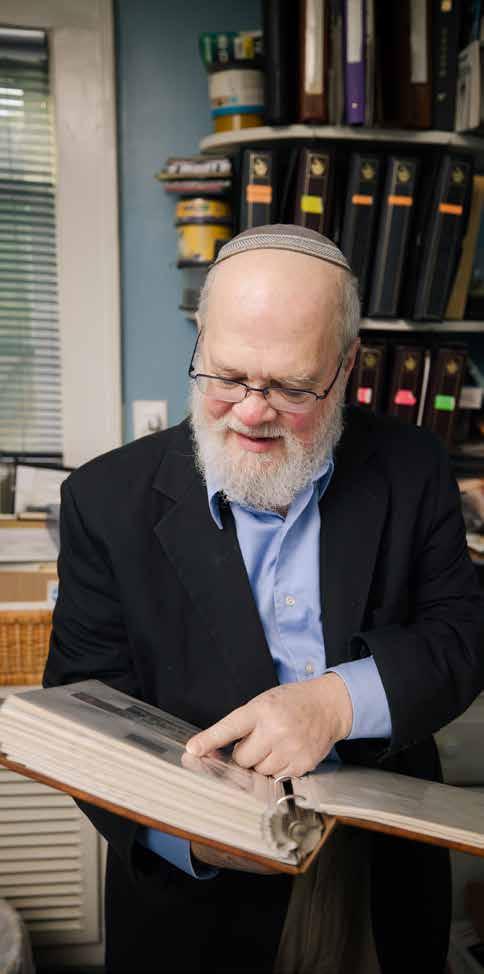

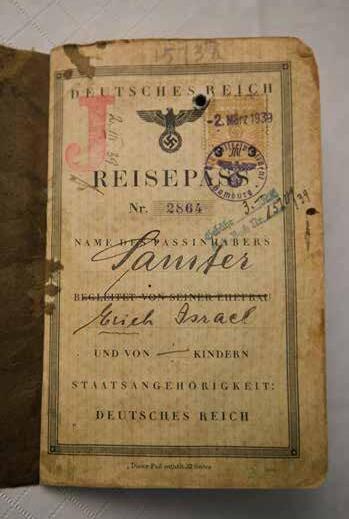

Holding Jewish History in Your Hand

LEGAL-EASE

A unique collection brings 2,000 years of Jewish life alive By David Olivestone

ON MY MIND

Is Compromised Tzenius the Cost of Being a Communal Leader? By Moishe Bane

DEPARTMENTS

LETTERS

FROM THE DESK OF RABBI MOSHE HAUER

An Inflection Point in Jewish Life—Mi va’Mi Haholchim

MENTSCH MANAGEMENT

What Are You Good At? The Art of Positive Feedback

By Rabbi Dr. Josh Joseph

IN FOCUS

A Lifeline for Israeli Teens By Chaim Pelzner

KOSHERKOPY

High Steaks: The Kashrus of Lab-Grown Meat

Talking with Rabbi Menachem Genack, CEO, OU Kosher 71 76 02 06 12 79 81

By David Olivestone 84 88 92 96 100 102 104

What’s the Truth about . . . Boiling Three Eggs?

By Rabbi Dr. Ari Z. Zivotofsky

THE CHEF’S TABLE

Taking it Outdoors

By Naomi Ross

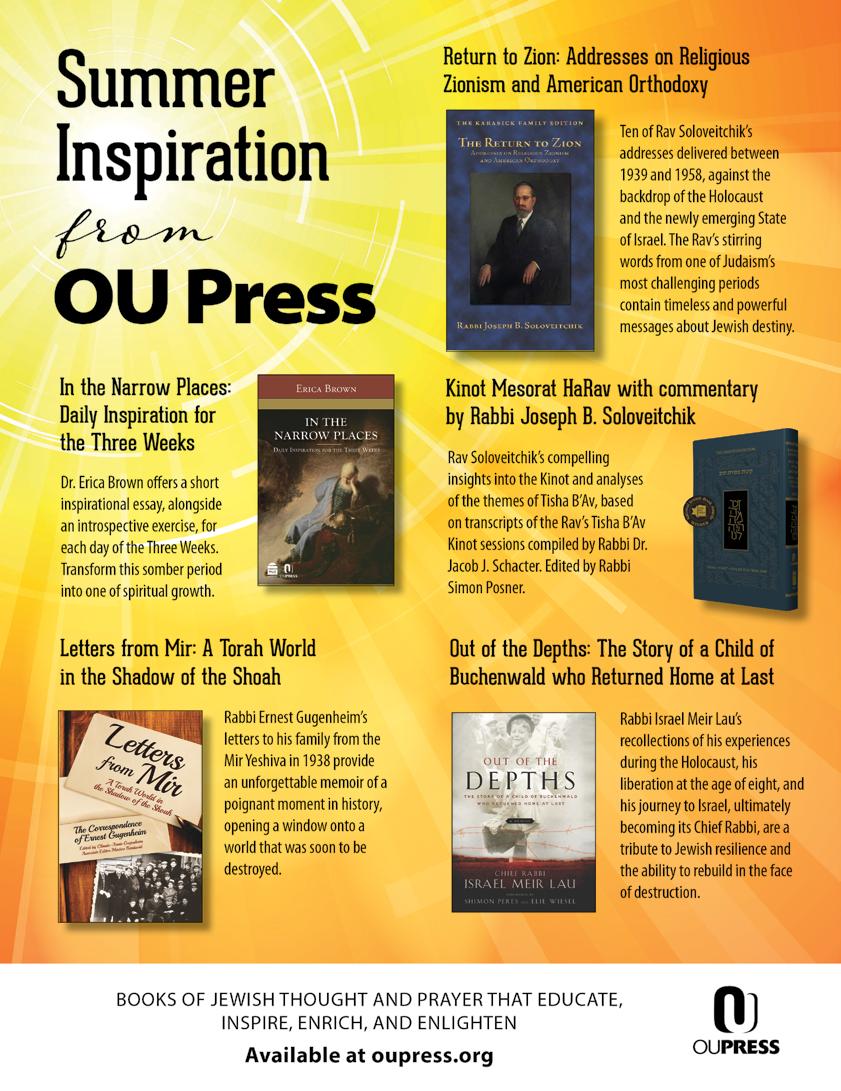

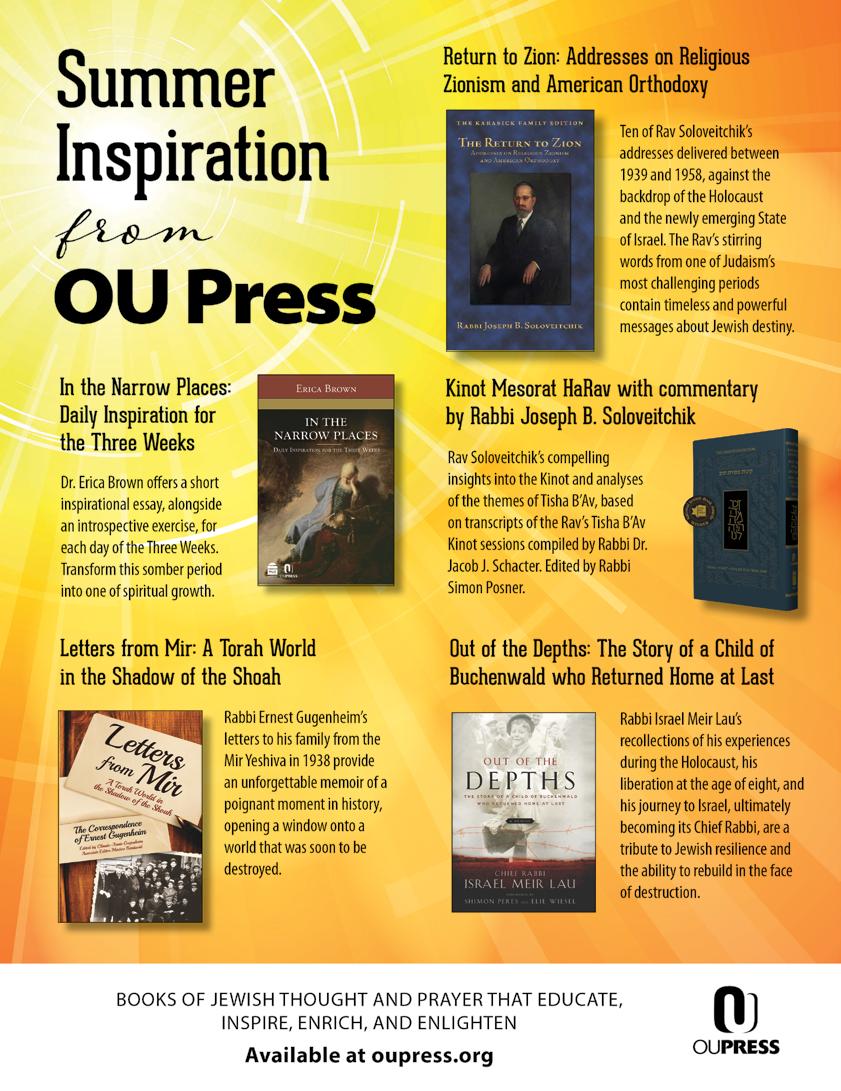

FROM OU PRESS Summer Reading Recommendations

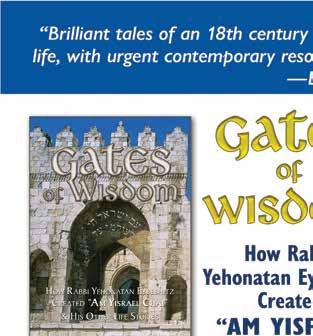

BOOKS

Rays of Wisdom: Torah insights that light up our understanding of the world

By Rabbi Mattisyahu Rosenblum, zt”l Reviewed by Rabbi Mark Gottlieb

Giving: The Essential Teaching of the Kabbalah

By Rabbi Avraham Mordechai Gottlieb Reviewed by Rabbi Yisrael Isser Zvi Herczeg

REVIEWS IN BRIEF By Rabbi Gil Student

LASTING IMPRESSIONS

Mah Shlomcha?

Cover Design: Bacio Design & Marketing, Inc.

Cover Photo: Ariel Jerozolimsky

1 Summer 5784/2024 JEWISH ACTION Jewish Action seeks to provide a forum for a diversity of legitimate opinions within the spectrum of Orthodox Judaism. Therefore, opinions expressed do not necessarily reflect the policy or opinion of the Orthodox Union. Jewish Action is published by the Orthodox Union • 40 Rector Street, 4th Floor, New York, NY 10006, 212.563.4000. Printed Quarterly—Winter, Spring, Summer, Fall, plus Special Passover issue. ISSN No. 0447-7049. Subscription: $16.00 per year; Canada, $20.00; Overseas, $60.00. Periodical's postage paid at New York, NY, and additional offices. POSTMASTER: Send address changes to Jewish Action, 40 Rector Street, New York, NY 10006. 71

Summer 2024/5784 | Vol. 84, No. 4

INSIDE

38 21

THE MAGAZINE OF THE ORTHODOX UNION jewishaction.com

DYNAMIC RELIGIOSITY

THE MAGAZINE OF THE ORTHODOX UNION jewishaction.com

Editor in Chief Nechama Carmel carmeln@ou.org

Associate Editor Sara Goldberg

Editor in Chief Nechama Carmel carmeln@ou.org

Associate Digital Editor Rachel Eisenberger

I enjoyed reading “Up Close with Rivka Ravitz” (spring 2024) and appreciate the contribution she and her husband have made to Israel and to Jews around the world. However, I respectfully disagree with her definition of Chareidi. When asked how she explained Chareidim to her secular colleagues, Mrs. Ravitz answered:

Assistant Editor Sara Olson

Rabbinic Advisor

Rabbi Yitzchak Breitowitz

Literary Editor Emeritus Matis Greenblatt

Book Editor

Rabbi Eliyahu Krakowski

Book Editor Rabbi Gil Student

Contributing Editors

Rabbi Yitzchok Adlerstein • Moishe Bane • Dr. Judith Bleich

Rabbi Emanuel Feldman • Rabbi Dr. Hillel Goldberg

Contributing Editors

Rabbi Sol Roth • Rabbi Jacob J. Schacter

Rabbi Yitzchok Adlerstein • Dr. Judith Bleich

Rabbi Berel Wein

Rabbi Emanuel Feldman • Rabbi Hillel Goldberg

Rabbi Sol Roth • Rabbi Jacob J. Schacter

Editorial Committee

Rabbi Berel Wein

Moishe Bane • Rabbi Dovid Bashevkin • Deborah Chames Cohen

Rabbi Binyamin Ehrenkranz • Rabbi Yaakov Glasser

Editorial Committee

Rabbi Avrohom Gordimer • David Olivestone

Rabbi Dovid Bashevkin • Rabbi Binyamin Ehrenkranz

Gerald M. Schreck • Dr. Rosalyn Sherman

Rabbi Avrohom Gordimer • David Olivestone

Rebbetzin Dr. Adina Shmidman • Rabbi Gil Student

Gerald M. Schreck • Rabbi Gil Student

Rabbi Dr. Tzvi Hersh Weinreb

Rabbi Dr. Tzvi Hersh Weinreb

I explained to them that the word Chareidi means to be afraid of change. Being a traditional Jew means keeping the traditions. I would tell them that my grandmother looked exactly like her grandmother and her grandmother exactly as her grandmother before that. We are averse to change because once you start making changes—even small ones—you don’t know where you’ll end up.

Copy Editor Hindy Mandel

Design 14Minds

Advertising Sales

Design Bacio Design & Marketing

Joseph Jacobs Advertising • 201.591.1713 arosenfeld@josephjacobs.org

Advertising Sales

Unfortunately, that attitude sounds defensive and will not resonate with today’s seekers of a dynamic, relevant religiosity. Chareidi means “fearful” as in fearful of G-d and fearful of crossing halachic boundaries. Learning to approach this fear amidst a plethora of nonobservance is incumbent on all of us seeking to find closeness to G-d in a turbulent world that competes with observance in a myriad of successful ways. Defining Chareidi as an old-school grandmother’s yarn will do little to instill confidence in those seeking truth in the Torah.

Subscriptions 212.613.8140

Joseph Jacobs Advertising • 201.591.1713 arosenfeld@josephjacobs.org

ORTHODOX UNION

Subscriptions 212.613.8134

President Mark (Moishe) Bane

ORTHODOX UNION

David Weissmann Atlanta, Georgia

President Mitchel R. Aeder

Chairman of the Board

Howard Tzvi Friedman

Chairman of the Board

Vice Chairman of the Board Mordecai D. Katz

Yehuda Neuberger

Vice Chairman of the Board

STANDING UP AGAINST ANTISEMITISM

Barbara Lehmann Siegel

Chairman, Board of Governors Henry I. Rothman

Chairman, Board of Governors Avi Katz

Vice Chairman, Board of Governors Gerald M. Schreck

Vice Chairman, Board of Governors Emanuel Adler

Executive Vice President/Chief Professional Officer Allen I. Fagin

Executive Vice President

Rabbi Moshe Hauer

Chief Institutional Advancement Officer Arnold Gerson

Executive Vice President & Chief Operating Officer

Senior Managing Director

Rabbi Steven Weil

Rabbi Josh Joseph, Ed.D. Chief of Staff Yoni Cohen

Executive Vice President, Emeritus

The accounts from Jewish students describing their recent experiences on campus (“Voices from Campus” [spring 2024]) were both disturbing and encouraging. While our universities have clearly become the epicenter and breeding ground for antisemitism in this country, it is encouraging that many Jewish students and Jewish organizations are standing tall and proud, despite the constant attacks and threats they face.

Managing Director, Communal Engagement

Rabbi Dr. Tzvi Hersh Weinreb

Rabbi Yaakov Glasser

Chief Financial Officer/Chief Administrative Officer

Shlomo Schwartz

Chief Human Resources Officer Josh Gottesman

Chief Human Resources Officer

Since October 7, I’ve concluded that the only safe place for Jews is Israel, and that at some point, we will all need to make aliyah. But in the meantime, I’d like to offer some advice based on my personal experience on how to deal with the crisis of antisemitism in our country.

Rabbi Lenny Bessler

Chief Information Officer Miriam Greenman

Chief Information Officer Samuel Davidovics

Managing Director, Public Affairs Maury Litwack

Chief Innovation Officer

Chief Financial Officer/Chief Administrative Officer Shlomo Schwartz

Rabbi Dave Felsenthal

General Counsel

Director of Marketing and Communications Gary Magder

Rachel Sims, Esq.

Jewish Action Committee

Executive Vice President, Emeritus

Gerald M. Schreck, Chairman

Rabbi Dr. Tzvi Hersh Weinreb

Joel M. Schreiber, Chairman Emeritus

Jewish Action Committee

Dr. Rosalyn Sherman, Chair

Gerald M. Schreck, Co-Chair

1. Don’t be afraid to engage and push back. When I was in college many years ago, the Israeli national basketball team was scheduled to play our varsity basketball team. Pro-Palestinian and radical leftist students pressured our team to boycott the game. I spoke with some of the players to convince them to play. The last thing one of them said to me: “We haven’t made up our minds yet.” But guess what? They showed up and played. Was I the one who changed their minds? Who knows, but my voice obviously didn’t hurt.

Joel M. Schreiber, Chairman Emeritus

©Copyright 2018 by the Orthodox Union Eleven Broadway, New York, NY 10004 Telephone 212.563.4000 • www.ou.org

©Copyright 2024 by the Orthodox Union

40 Rector Street, 4th Floor, New York, NY 10006

Telephone 212.563.4000 • www.ou.org

Twitter: @Jewish_Action Facebook: JewishAction

Facebook: Jewish Action Magazine

Twitter: Jewish_Action Linkedln: Jewish Action Instagram: jewishaction_magazine

2. Get involved in the political process. I’m in regular contact with my senators and representatives, thanking the ones who support us, and asking the others for their help. Every letter and phone call to your legislator is tallied, so don’t think your voice doesn’t count. The greatest fear of every elected official is losing an election.

2 JEWISH ACTION Summer 5784/2024

LETTERS

IS SPREADING ON COLLEGE CAMPUSES AROUND THE COUNTRY.

Touro, we are proud of our Jewish heritage—it is the foundation upon which our university was created.

a community dedicated to keeping you safe on campus in an academic environment where your values are respected, your professional dreams are nurtured and your success is paramount.

you want to go,

can take you there. TRANSFER STUDENTS: ASK US ABOUT OUR SAFE CAMPUS SCHOLARSHIP Contact robert.fogel2@touro.edu for more info YOUR UNIVERSITY YOUR VALUES

ANTISEMITISM

At

Experience

Wherever

Touro

3. Register to vote in the upcoming November election, and be sure to cast your ballot. As Jews and Americans we have the power of the ballot box, and we need to wield that power.

4. For those of us who want to help Israel during this crisis, I offer this: Go there! The best thing you can give Israel now is you. Donating money is nice, but being there to show your support does wonders, not only for the Israelis, but for your soul and your Jewish pride. This is our time to step up and help our fellow Jews.

Jay Lewis

York, Pennsylvania

“Voices From Campus” was simultaneously depressing and inspiring. Overt antisemitism grows on America’s elite college campuses, and the courageous response of Jewish students under attack, determined not to be modernday Marranos, is deeply inspiring. But they need outside support of their efforts.

Harvard student Isaac Ohrenstein noted how important an organized alumni voice can be. “Alums for Campus Fairness” provides such a voice. We have seventy-six chapters and nearly 55,000 individual members. Alums should visit https://www.campusfairness.org to easily join this effective, growing campus presence.

Richard D. Wilkins

Syracuse, New York Syracuse University Chapter Alums for Campus Fairness

THE BERACHAH ON GLUTEN-FREE BREAD

In Rabbi Eli Gersten’s response to letter writer Barbara Bolshon (spring 2024) about the proper berachah on gluten-free bread, he states: “Gluten-free bread, while shaped to look like bread, is not halachically considered lechem as it is not made from one of the five grains, and therefore its berachah is Shehakol.” While the bread in question was not made from the five grains, there are many gluten-free breads made today from the five grains (e.g., gluten-free oats), which would require a Hamotzi. For Pesach, gluten-free matzot made from the five grains are available, and require the berachah of Hamotzi.

Joe Offenbacher Chashmonaim, Israel

THE TIME HAS COME

Regarding the article “My Yarmulke” (spring 2024), OU President Mitchel R. Aeder wrote, “Wearing a yarmulke or a Magen David suddenly became fraught in many American cities” and “Administrators at a Jewish day school in California recently instructed first graders not to wear their kippot on a field trip, out of fear.” Have we, as Jewish people, forgotten the cycle of history that we have gone through since Egypt? For those who have forgotten, here is a recap: We settle in a foreign land, prosper and the locals start to persecute us. Egypt, Babylon, Spain, France, Germany, Russia and Poland are some examples. The rise in antisemitism across America (and other countries) is a sign and reminder from Hashem, telling us where we truly belong, as one nation: in the Land of Israel.

The time has come for rabbis and leaders in Jewish communities across the Diaspora to encourage members of their community to make aliyah or maybe even lead by example.

Oren Rimmon Modiin, Israel

CORRECTION

In “What’s the Truth about . . . Rashi Script?” (spring 2024), the caption under the image of a shekel coin identified the letters on the coin as shin-kuflamed, spelling “shekel.” This is incorrect. The three letters on a shekel coin are yud-hehdalet for “yehud,” which is the ancient designation for the province of Judea in the Persian Empire. Thanks to Dr. Lawrence H. Schiffman, professor of Hebrew and Judaic studies, NYU, for pointing this out.

Transliterations in the magazine are based on Sephardic pronunciation, unless an author is known to use Ashkenazic pronunciation. Thus, the inconsistencies in transliterations in the magazine are due to authors’ preferences.

This magazine contains divrei Torah and should therefore be disposed of respectfully by either double-wrapping prior to disposal or placing in a recycling bin.

WE WANT TO HEAR FROM YOU!

To send a letter to Jewish Action, e-mail ja@ou.org. Letters may be edited for clarity.

4 JEWISH ACTION Summer 5784/2024

M.A. in Jewish Studies

At the Bernard Revel Graduate School of Jewish Studies

World-Class Faculty

Generous Scholarships

Remote and In-Person

“Studying in a program with such a small studentto-professor ratio has enabled me to forge personal mentorship relationships with leading scholars and receive individualized support in my coursework.”

Rachel Rosensweig, 2022 graduate

Learn more about Summer & Fall Courses at yu.edu/revel/courses

5 Summer 5784/2024 JEWISH ACTION

FROM THE DESK OF RABBI MOSHE HAUER

AN INFLECTION POINT IN JEWISH LIFE— MI VA’MI HAHOLCHIM

By Rabbi Moshe Hauer

By Rabbi Moshe Hauer

On January 25, 2023, I [Rebecca Alpert], along with 9 other rabbis, representing another 265 rabbis from around the globe and every imaginable denomination, met with Secretary General António Guterres at the United Nations headquarters. You might think that we went to tell him what most Jews are presumed to believe, namely that the UN has it out for Israel and always treats the Jewish state unfairly. Nothing could have been farther from our minds. Rather, we went to thank him and the UN’s agencies for courageously calling out Israel for the humanitarian crimes they are committing in Gaza and to promote our cause: Ceasefire Now!1

While the actions of this group are on the fringe, groups like T’ruah2 and the affiliated organizations of the Union for Reform Judaism3 regularly make statements that call out the Israeli government, army and large sectors of its citizenry for their alleged extremism and thirst for never-ending war. These statements present their genuine sympathies for those killed and taken hostage on October 7 along with the demand for Israel to provide a fast track to Palestinian statehood without serious expectations for change in Palestinian behaviors and values. Rebuke of Israel is plentiful, while consideration of their security needs is scarce. The morality of Tzahal is frequently attacked and rarely, if ever, held up and recognized.

Many of us in the American Jewish community are pained by our apparent alienation from the students, faculty and administration of the universities in which we have long studied and invested. We are disoriented by the silence of our religious and civil rights colleagues beyond the Jewish community with whom we had consistently stood as allies but who apparently lost their voices on October 7. But what we are most distraught over are the growing differences among Jews. We appear to be at an inflection point in Jewish life, one in which the internal divisions within Klal Yisrael have grown beyond fundamental religious differences to contrasting conceptions

of “peoplehood” and its implications. While this change will not at all impact our firm commitment to support and protect all Jews, it will profoundly limit whom among them we see as our partners.

The Orthodox perspective on Jewish unity hinges on two core beliefs—which are in tension. Our firm belief in the Divinity and immutability of the Torah is a fundamental religious assumption that is not shared by those beyond Orthodoxy, preventing our collaboration on internal religious issues.4 At the same time, Orthodoxy believes as well in the immutability of Jewish identity, such that all Jews are responsible for one another, areivim zeh bazeh, 5 whatever their affiliation or level of observance; Yisrael af al pi shechata, Yisrael hu. 6 This latter belief has driven meaningful Orthodox partnership with a wide variety of Jewish groups on matters that impact the safety and material well-being of our people. And while there have been two centuries of intense debate within Orthodoxy over the appropriateness of partnership with the non-observant on material matters, the Orthodox Union follows the guidance of Rabbi Joseph Ber Soloveitchik7 and continues on the path charted by Rabbi Naftali Zvi Yehudah Berlin of Volozhin (the Netziv). In a classic responsum penned in 1879,8 the Netziv objected to the utter separation promoted by the school of the Chatam Sofer9 and advocated instead for all Jews to stick together as we face growing antisemitism. The Netziv noted wryly that the Torah compares the Jews in exile

6 JEWISH ACTION Summer 5784/2024

Rabbi Moshe Hauer is executive vice president of the Orthodox Union.

to the dust of the earth,10 while the prophet compares the nations of the world to the raging sea.11 Those raging waters would completely wash away the dust unless the dust clumps together into a hardened and indivisible rocky mass, in which case the worst that could happen would be for the rock to be carried by the waves to a different location; it would never be destroyed. Thus, wrote the Netziv, “how can we suggest separation from our fellow Jews when that will leave all of us vulnerable to being washed away, bit by bit, by the wave tides of antisemitism?!”

In my role representing the OU around a variety of communal tables, I have been blessed to build many meaningful relationships across the Jewish community and have found both friendship and outstanding partnership with many Jewish leaders from beyond the Orthodox community. That remains the case today, and it is a precious experience of achdut. Yet with some of those leaders, it appears that we are approaching or may have reached a point where the assumption of ongoing partnership is unfeasible, not because of religious differences but because our dissimilar approaches to defending the Jewish people are on a collision course. We remain brothers, but not assumed partners. To use a Biblical illustration invoked by the Netziv: Avraham demonstrated unconditional loyalty and commitment to Lot, risking everything to go to war to gain Lot’s freedom despite his clear rejection of much of Avraham’s value system. Unlike our current situation, Lot’s move away from Avraham’s belief system posed no danger to Avraham. He did not speak in Avraham’s name and advocate for positions that would endanger him. Lot was a harmless disappointment. Even so, that same Avraham who would do everything for Lot, felt that he could not continue to do things with him, electing instead to dissolve their partnership. Kal vachomer . . .

This is neither a new nor purely Orthodox issue; it has been grappled with for years by the broader Jewish community in determining who gets a seat at the Jewish communal

table. Is the Jewish Voice for Peace (JVP) welcome? What about J Street? Today, however, the cadre of Jewish officials and organizations that are embracing troubling positions and concerning approaches to “standing up for Israel” has grown beyond those organizations mission-driven to redirect the Israel narrative. This growth is not primarily driven by the establishment non-denominational Jewish organizations as their approach to these issues is practical and they clearly see the looming threats to the Jewish future. The trouble seems to consistently emanate from those who have elevated their universalism into a religious or pseudo-religious value that seems to overshadow the critical moral imperative to be our own brother’s keeper. These organizations are anything but antisemitic, but their approaches frequently appear to undermine rather than strengthen the security of the Jewish people. While we will often be pushing in the same direction, their mingling of values makes ongoing assumed partnership a mixed bag and unreliable.

We return to the question: What actions or beliefs make a Jewish group an unreliable partner in the enterprise of preserving the Jewish future? This is not a search for a national loyalty test, and there is no McCarthyistic plan to redefine the lines of Jewish community. Nor is there any interest in stifling debate or legitimate criticism of Israel. Rather than a philosophical exercise of defining the range of legitimate opinions, we must seek to clarify the practical consideration of identifying who is a reliable partner in our efforts to enhance the security and material well-being of Jews and of the State of Israel.

Perhaps the answer can be found in the words of the prophet Zecharyah (2:12), describing G-d’s instinctive protectiveness of the Jewish people: “Ki hanogei’a bachem, nogei’a b’vavat eyno— Whoever touches you, touches the pupil of His eye.” That is the perfect illustration of what true caring looks like. Rather than calculated, visionary and objective, it is reflexive, visceral and personal, exactly as we are with our

When any Jew anywhere is threatened, it should feel like someone has poked us in the eye.

immediate family. Between themselves, family members are often insensitive and critical of each other, but should someone from outside the family attack or insult those dear to us, we respond reflexively, viscerally and personally, as if someone had poked us in the eye. It should be no different when Jews anywhere are threatened: when any Jew anywhere is threatened, it should feel like someone has poked us in the eye. Building on this framework, we can suggest four positions and values that fail this test and would preclude ongoing assumed partnership on defending Jews and supporting Israel. Disagreeing with any of these is not illegitimate, but as we assemble the forces of uncompromised loyalty to Jewish survival, our partnership with those who fail on any of these counts would force us to dilute and curtail rather than enhance and strengthen our support for Israel.

1. We cannot assume partnership with anyone who aligns with those who seek to harm Jews.

Whatever opinion we may have of the current government, of its policies in Gaza or of the entire Zionist enterprise, there is no room for Jews to align themselves with those who seek to harm the Jewish people. This includes the Neturei Karta’s alliance with the Iranians, JVP’s alliance with SJP, the “Rabbis for Ceasefire” who congratulate the UN for their obsession with Israel, and those who make common cause with the groups creating a hostile environment for Jews on campus.

7 Summer 5784/2024 JEWISH ACTION

DEEPLY ROOTED VALUES THAT MOVE HISTORY FORWARD

8 JEWISH ACTION

2. We cannot assume partnership with those who do not prioritize Jewish self-defense and do not recognize Israel’s right to have the last word on its own security. We must all be concerned about harm to innocent civilians in Gaza, but we cannot partner with those who approach the threats to Israel “objectively” and advocate for the aspirations of Palestinians at the expense of securing Jews.

3. We cannot assume partnership with those who do not see and champion the goodness that permeates Israel, who seem more ashamed than proud of Israel, and who constantly question the justice of its cause, its culture and its morality. Israel is not perfect and we must be honest about its failings, but it is built on strong values, is the land to which the Jewish people are integrally and historically connected, and has an army dedicated in principle to decency and kindness that is setting an unprecedented high standard in its wartime efforts to reduce civilian casualties and provide humanitarian aid to the enemy’s general population.

4. We cannot assume partnership with those who fail to unconditionally support the existence and defense of Israel even when critiquing it. Israel must be and indeed is a place where everything is argued and debated, but those loyal to Israel will stand by it unconditionally, regardless of its specific legislative stances. For example, during the judicial reform controversy, Prime Minister Netanyahu came to the United Nations to address the malign and existential threat posed by Iran.

That was not the time for Jews to assemble outside the UN and declare the Prime Minister and the state undemocratic.

An astute colleague noted that much has been learned since October 7, both in Israel and in America. In Israel we have learned how connected we are even to those with whom we have significant differences, and in America we have learned how alienated we are from some of those with whom we had previously felt connected. That alienation is something we must sadly accept relative to our erstwhile external allies, but how can we allow it to impact the Jewish community internally?! This is a time when all of us must realize how much we need each other and must stand up for each other, when we are protective rather than objective, feeling viscerally and instinctively that hanogei’a bachem, nogei’a b’vavat eyno, whoever threatens Jews anywhere is poking me in the eye.

That is what peoplehood requires. That is what makes for reliable partnership.

Notes

1. Rebecca Alpert, “Rabbis for Ceasefire at the United Nations,” Contending Modernities blog, University of Notre Dame, https://contendingmodernities. nd.edu/global-currents/rabbisfor-ceasefire-un/.

2. https://truah.org/press/north- americanrabbis-and-cantors-call-on- presidentbiden-to-push-for-end-of-war-in-gaza/.

3. https://urj.org/press-room/moment-weare-future-we-pray.

4. In the words of Rabbi Joseph Ber Soloveitchik: “When unity must be manifested in a spiritual-ideological meaning as a Torah community, it seems to me that the Orthodox cannot and should not join with other such groups that deny the foundations of our weltanschauung.” Cited by Rabbi Bernard Rosensweig, “The Rav as Communal Leader,” Tradition vol. 30, no. 4 (summer 1996),

https://traditiononline.org/the-rav-ascommunal-leader/.

5. Sanhedrin 27b.

6. Sanhedrin 44a.

7. In the same essay, the author cites Rav Soloveitchik advancing an argument in 1954 that continues to be repeated by hosts of others: “In the crematoria, the ashes of Hasidim and anshei ma’ase (pious Jews) were mixed with the ashes of radicals and freethinkers. We must fight (together) against an enemy who does not recognize the difference between one who worships and one who does not.”

8. Meishiv Davar I:44. The Netziv wrote in response to an editorial in Machzikei Hadas, a journal produced by Rabbi Shimon Sofer of Krakow, son of the Chatam Sofer, whose author advocated for complete separation from the non-observant.

9. See, for example, the conclusion of Responsa Chatam Sofer 6:89.

10. Bereishit 28:14.

11. Yeshayahu 17:12.

Subscribe to our monthly digital newsletter for:

Web exclusive content

Gems from our archives

Articles from around the web

www.jewishaction.com/newsletter/

10 JEWISH ACTION Summer 5784/2024

MAIL 1m ago Jewish Action Your monthly newsletter has arrived! MAIL 4w ago Jewish Action Your monthly newsletter has arrived! MAIL 8w ago JewishAction

NEXT STOP PHYSICIAN ASSISTANT

FOR MORE THAN 50 YEARS, TOURO’S PHYSICIAN ASSISTANT (P.A.) PROGRAM HAS BEEN A POWERHOUSE IN THE EDUCATION AND TRAINING OF SKILLED AND DEDICATED P.A. PROFESSIONALS.

Graduates of our fully accredited P.A. programs in six different locations have a 100% pass rate on the licensure exams and enjoy successful careers at prestigious institutions in the fields of cardiology, dermatology, pediatrics, psychiatry, surgery and more. Whatever your goal, Touro can take you there.

11 Summer 5784/2024 JEWISH ACTION

touro.edu/poweryourpath

WHAT ARE YOU GOOD AT? THE ART OF POSITIVE FEEDBACK

By Rabbi Dr. Josh Joseph

By Rabbi Dr. Josh Joseph

Times have been hard. Even dark. Many years ago, I faced some dark times personally, and frankly, I was floundering. In those days I carried a checklist with me all day and the greatest satisfaction I had was crossing things off that list. I was busy and accomplishing a lot; my superiors were thrilled, and I received numerous dopamine hits as I crossed item after item off my list. Until, one day, I stopped myself and wondered, “Who would I be without this list? Who am I without these external validators?”

I found myself going down a dark rabbit hole of self-doubt, until my conversation with Tzvi,* a longtime friend. We were catching up and suddenly he turned to me and said, “Hey, Josh, you know what you’re really good at?” And he proceeded to describe an area in which he thought I excelled. Though I wish I could recall the specific point, I do not remember what he told me. Nevertheless, that tiny drop of feedback shot me right out of that rabbit hole and restored my sense of self.

A few weeks later, still aloft on that cloud of positivity, I was at a social function when I heard Tzvi walk over to someone and say, “Hey, David, do you know what you’re really good at?”

Oh well, I thought. I guess I’m not that special!

Psychologists have observed that not all emotions are created equal. We gravitate toward the negative far more than the positive. From Jim Collins’ work,1 to research done by Gallup,2 to articles from researchers at Yale and beyond, it is clear that we are more successful, happy and fulfilled when we know our strengths. As Ken Robinson notes,3 we can be our best, in our “element,” only when we find “the point at which natural talent meets personal passion.” Instead, unfortunately, “too many think they’re not good at anything.”

At times like these, not only do we get down on “life, the universe and everything,” but we can be down on ourselves. Try coming up with four weaknesses or areas in your life that could use improvement. Now try coming up with four strengths. Most people will quickly arrive at their four weaknesses and will take far longer to come up with a list of strengths. That’s where leaders, managers, parents and friends come in.

In a recent article,4 David Brooks refers to middle managers as “the unsung heroes of our age.” At a time of seemingly widening division and outright conflict, we need people who can struggle to resolve tension, who can promote belonging at home, with their teams at work, and within their communities:

So how do these managers work their magic? When I hear people in these roles talk about their work and its challenges, I hear, at least among the most inspiring of them, about the ways they put people over process, about the ways they deeply honor those right around them.

Brooks refers to their approach not simply as management, but rather as “ethical leadership.” The lesson here goes beyond its resonance with the conceptual—aligned with mentsch

management!—and impacts on the practical. While Brooks himself points to eight applications of ethical leadership, for many of us managers there exist manifold tugs on our limited attention— and thus we are unable to make the time to give positive attention to those around us. Classically, feedback is given once a year, or if something went terribly wrong. But imagine channeling our inner Tzvis and giving positive feedback regularly. It is likely that a good number of our employees are struggling like I was. Imagine what we could do for them, and ultimately what it could do for the company or organization, by letting them know, after they’ve just completed an endeavor you were genuinely impressed with, how great they are at that endeavor.

To be a mentsch, a manager should be giving consistent and honest feedback. The feedback can, of course, include areas that need to be improved on. But our employees will often already know where and how they are falling short. It is just as critical, if not more important, to share positive feedback as well.

Our incredible OU “people team”— the professionals in the Human Resources department—has pioneered a new feedback plan this year as part of our commitment to fostering a culture of ongoing feedback. We established five touchpoints throughout the year, including initial goal setting, two career conversation days and a mid-year check-in, culminating in a traditional performance review, all of which aim to create more opportunities for reflection, discussion and refinement of goals. The results? Managers and employees both benefit greatly!

In Parashat Vayechi, Yaakov famously switched his hands when giving berachot

Rabbi Dr. Josh Joseph is executive vice president/chief operating officer of the OU.

12 JEWISH ACTION Summer 5784/2024

MENTSCH MANAGEMENT

We can be our best, in our element, only when we find the point at which natural talent meets personal passion. Instead, unfortunately, too many think they’re not good at anything.

to his grandsons, Ephraim and Menashe. While one would expect him to place his right hand on the older grandson and his left hand on the younger, he actually did the opposite and crisscrossed his hands. Why not just switch the boys’ positions?

According to the Netziv, this teaches us that Ephraim surpassed Menashe in ruchniyut, in the spiritual realm, which is above the natural ways of the world. Menashe, however, was superior to Ephraim in gashmiyut, in all physical matters of the world.

Yaakov knew what he was doing, especially having learned from his earlier episode with Eisav. Rather than discount Menashe’s material and physical gifts and talent, certainly a necessity for the future of the nation, Yaakov kept him on his right. After all, he was still the firstborn! Yaakov therefore simply crossed his hands, placing his right hand on Ephraim’s head, to indicate that the blessing of spiritual leadership would be given to Ephraim.

When blessing our children on Friday night, in addition to giving them the traditional berachah, my wife and I try to point out to our children something specific they’ve accomplished or an aspect in which they aspire to grow and succeed. We try to channel the berachah toward something in particular. We tell them what they’re good at.

A few years after Tzvi helped me out, he was mulling over some life decisions and was questioning his own abilities. To that point it hadn’t occurred to me that although he had helped others with his suggestions, perhaps others hadn’t returned the favor. “You know what you’re really good at?” I told him. “You’re really good at telling people what they’re good at.” He looked at me, stunned, not knowing what I was talking about. So I explained—passing back to him the gift he had given me and my family and many others.

Whom will you bless next with their own gifts?

*Not his real name.

Notes

1. Jim Collins, “How To Find Your Personal Hedgehog Concept,” https://www.jimcollins.com/media_topics/PersonalHedgehog Concept.html.

2. https://www.gallup.com/cliftonstrengths/en/253790/science-ofcliftonstrengths.aspx#. To quote Gallup’s CliftonStrengths® founder Don Clifton, “Strengths science answers questions about what’s right with people rather than what’s wrong with them.”

3. Ken Robinson, The Element: How Finding Your Passion Changes Everything (New York: Penguin Books, 2009), 21.

4. “In Praise of Middle Managers,” New York Times, Apr. 11, 2024. https://www.nytimes.com/2024/04/11/opinion/middle-managersbusiness-society.html.

13 Summer 5784/2024 JEWISH ACTION

Religion

JEWISH ACTION Summer 5784/2024

COVER STORY

15 Summer 5784/2024 JEWISH ACTION

Photo: Ariel Jerozolimsky

What Does the Torah Have to Say about

By Rabbi Dr. Shlomo Brody

By Rabbi Dr. Shlomo Brody

What can our tradition teach us about military ethics and the questions facing Israel today? The prospect of Israel facing many months, if not years, of protracted battle against Hamas and Hezbollah in urban settings raises many strategic and ethical dilemmas. We’ll need to fight decisively against ruthless enemies while acting in a way that will preserve our moral standards and diplomatic standing. A careful examination of rabbinic responses to Israel’s first war against terrorists might help guide us in our difficult struggle.

It was a sweltering summer day in August 1982 when Rabbi Shlomo Goren, Israel’s Ashkenazic chief rabbi, dropped an ethical bombshell: Jewish law required Israel to allow combatants and noncombatants to flee Beirut. Israel was strategically besieging and bombarding the Lebanese capital. The goal was to uproot the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO), which had long terrorized the Jewish State from its northern border. The siege began several weeks into Operation Peace of

Galilee, later to be known as the (First) Lebanon War. Rabbi Goren adamantly supported the war as a war of selfdefense (milchemet mitzvah). Yet he cited the second-century rabbinic sage Rabbi Natan who, followed by the Rambam, ruled that the “fourth side” of a besieged city must remain open as an evacuation corridor. Doing so gives combatants an incentive to flee; otherwise, they might fight to the finish, at great cost to both sides. Beyond its strategic value, it is important to show mercy during war, even to the enemy side, since all humans are created in the image of G-d. No outsiders or supplies needed to be allowed into the city. Yet everyone must be able to run for their lives.

Rabbi Goren’s public ruling created a bit of a brouhaha. Who lets terrorists

16 JEWISH ACTION Summer 5784/2024

16 JEWISH ACTION Summer

Rabbi Dr. Shlomo Brody is the executive director of Ematai and the author of Ethics of Our Fighters: A Jewish View on War & Morality (Jerusalem: Maggid Books, 2023).

?

Photo: Chaim Goldberg/Flash90

Rabbi Shlomo Goren, Israel’s Ashkenazic chief rabbi at the time of the Lebanon War in 1982. Courtesy of the Israel Government Press Office/ Ya'acov Sa'ar

Rabbi Goren would deem this gesture a prime example of how Judaism can teach the world how to fight wars ethically. It was a great kiddush Hashem.

escape from the claws of the siege?

Rabbi Shaul Yisraeli, head of Yeshivat Mercaz HaRav, wrote a private letter against the chief rabbi’s ruling. He argued that the ancient sources were offering tactical advice but not bonafide mitzvot. At best, this humanitarian gesture was only required in a case of expansionist warfare. The Ramban and Sefer HaChinuch, for example, indicated that the “fourth-side open” rule only applied in discretionary warfare (milchemet reshut), but not in wars of self-defense. It is implausible to think we should do anything less than kill or capture terrorists who actively threaten us. Rabbi Yisraeli, however, did concede that noncombatants should be allowed out of the city. Other decisors went further than Rabbi Yisraeli: there is no halachic requirement to let anyone out of a siege unless the goal is to conquer the territory alone. Enemies need to be fought decisively.

The IDF, for its own reasons, left open two major escape routes from Beirut. The army had no interest in the PLO terrorists fighting to the last man. They certainly did not desire to harm noncombatants. An estimated 100,000 people fled the city. Soon afterward, the Reagan administration negotiated a ceasefire that allowed Arafat and thousands of his fighters to leave the city.

This wasn’t the first time the “fourthside open” rule was invoked to teach the ethics of war. In 1977, the eminent philosopher Michael Walzer published his classic book, Just and Unjust Wars

An affiliated Jew, Walzer cited the “fourth-side open” rule as a key element in removing an attacker’s culpability for noncombatant casualties in urban warfare. When you give people the

opportunity to flee, it shows that your intent is not indiscriminate killing.

A few years later, Israel implemented this religious teaching in practice, not just on paper. It was the first time in many centuries that Jews had power and could implement Rabbi Natan’s teaching, and they did not fail. Even during a just war, we try to minimize bloodshed. Trevor N. Dupuy and Paul Martell, two military historians who covered the war from Lebanon, later asserted, “We can think of no war in which greater military advantages were gained in combat in densely populated areas at such a small cost in civilian lives lost.” And this, they added, despite the PLO’s purposeful placement of its fighters within civilian territories. Rabbi Goren would deem this gesture a prime example of how Judaism can teach the world how to fight wars ethically. It was a great kiddush Hashem.

I’ve been thinking about Rabbi Goren’s position since Hamas’s brutal October 7th attack. Israelis are united in believing that the country must remove the threat of Hamas from its border. Yet they have not opposed their government’s attempts to forewarn Gazan civilians of impending attacks, or to create evacuation corridors from neighborhoods in which Hamas embeds its fighters (itself a war crime). Israelis want to minimize noncombatant casualties. The Jewish State’s enemies target its citizens, but Israel will not respond in kind.

These humanitarian gestures have not won the Jewish State—or Judaism—too many fans. Most outrageously, as of this writing in April, the International Court of Justice began legal proceedings against Israel for alleged genocide. The allegation is utterly false and disgraceful on many levels, as all decent people have noted. One element of the accusation bears closer attention. South Africa, in its indictment, cited a brief press conference statement by Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu that made a Biblical reference. He stated, “You must remember what Amalek has done to you, says our Holy Bible. And we do remember.” The indictment further cited videos of IDF soldiers chanting “wipe off the seed of Amalek” before they entered Gaza. The implication, as online outlets like Mother Jones alleged, is that Judaism is inspiring genocidal intent.

17 Summer 5784/2024 JEWISH ACTION

Photo: Israel Government Press Office

Minimizing civilian casualties is a religious imperative. Yet so is defeating an evil enemy that threatens our people. Selfdefense is also a “humanitarian” moral obligation, not just a matter of interests.

The allegation is preposterous. In the same press conference, Netanyahu stressed how much Israel is doing to avoid civilian casualties. Rhetoric invoking Amalek has been merely semantic and quite limited. As Rambam taught in both Mishneh Torah (Hilchot Melachim 5:4-5) and Moreh Nevuchim (3:50), the mitzvah of wiping out Amalekites only applies to that specific nation, and their identity has been lost. Leading figures like Rabbi Tzvi Yehuda Kook, zt”l and Rabbi Nachum Eliezer Rabinovitch, zt”l affirmed this mitzvah is not relevant and should not be applied to any contemporary conflict.

Yet the larger claim needs to be addressed: Does Judaism encourage a certain type of religious fundamentalism that leads to unfettered violence? Critics of Israel would like to say that Judaism, like Islam, has its own form of holy war that leads to indiscriminate killing.

Yet our Avot teach us otherwise. Midrashic passages about our Biblical forefathers indicate that Jewish law

prohibits targeting non-combatants amongst the enemy population. The Torah states that Avraham was petrified before going to war to redeem Lot from captivity. One midrash asserts that he feared killing righteous people amongst the enemy population; G-d had to reassure him that all of his victims would be culpable (Bereishit Rabbah 44:4). Perhaps for this reason, when the Torah tells us to put “all men to the sword” (Devarim 20:13) in war, Rabbi Saadia Gaon, the Netziv, Rabbi David Tzvi Hoffman and, most recently, Rabbi Yaakov Ariel of Ramat Gan, explicitly assert that this means to kill combatants. Non-combatants are not our targets.

A similar midrash asserts that Yaakov Avinu was distressed by confronting and killing the 400 men accompanying his vengeful brother Esav, even though Yaakov was acting out of self-defense (Rashi, Bereishit 32:8). While violence is justifiable in such circumstances, Rabbi Eliyahu Mizrachi speculates that Yaakov feared killing those who could have been

neutralized in a less lethal manner. The Maharal alternatively suggests that his concern was killing coerced combatants who had no intent to actually fight.

Following the rape of Dina, her brothers Shimon and Levi vengefully wiped out the city of Shechem. How could they kill so many people? The Maharal asserts that the brothers justified their actions by maintaining that in war, the entire nation is treated as a collective, combatants and noncombatants alike. Yet as Rabbi Ariel has argued, this comment may only justify why fighters would not be punished for incidentally killing civilians amongst the combatants. In the context of war, non-combatants are inevitably harmed. It does not justify, however, directly targeting innocents. Indeed, as Rabbi Asher Weiss notes, the same Maharal had argued that Yaakov feared he would be punished for killing Esau’s reluctant warriors, even though they would certainly be more culpable than noncombatant bystanders. Yaakov Avinu rejected learning any precedent from Shimon and Levi. As the Ramban and Rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch note, at the end of Sefer Bereishit (49:5-6), Yaakov censures his sons while on his deathbed, proving that the brothers’ actions were misguided.

The lesson was well-summed up by Rabbi Goren. “We are commanded . . . even in times of war . . . not to harm the non-combatant population, and certainly one is not allowed to purposely harm women and children who do not participate.” Similar sentiments were also expressed during the First Lebanon War by Rabbi Aharon Lichtenstein of Yeshivat Har Etzion, who asserted that strategists should consider expected enemy collateral damage before making decisions. Moral constraints remain relevant in wartime. This is our mesorah We should live by these values, both in 1982 and 2024.

So minimizing civilian casualties is a religious imperative. Yet so is defeating an evil enemy that threatens our people. Self-defense is also a “humanitarian” moral obligation, not just a matter of

JEWISH ACTION Summer 5784/2024

Photo: Michael Giladi/Flash90

@BARTENURABLUE

interests. Leaving the fourth-side open of a siege works best when you just want to conquer the territory or city and don’t care if the inhabitants flee. When this tactic allows terrorists to survive and regroup, it becomes morally complex, as we learned from the aftermath of the siege on Beirut.

In 1983, a year after the siege ended, many PLO fighters, including Arafat, made their way back to Lebanon to shore up support for their cause. They were now based in the port city of Tripoli but surrounded by splinter groups who had rebelled against the PLO. The UN, wanting to avoid another Lebanese civil war, negotiated a settlement to evacuate Arafat and his troops. Then, on December 6, 1983, Palestinian terrorists detonated a bomb on a Jerusalem bus. Six Israelis were killed. PLO loyalists and rebels both took credit for the attack.

Israel’s new defense minister, Moshe Arens, condemned the international evacuation plan for letting terrorists escape. “If a terrorist committed an atrocity, and a democratic country helped get him to a new location so he could commit more such acts, that is not something which those of us who accept democratic values can accept.”

Israel launched a naval blockade on the Lebanese coast and shelled PLO positions in Tripoli. The hope was that the rebel groups would further weaken the PLO. Others dreamed that they would even kill Arafat.

Instead, under immense American and European pressure, Israel opened the blockade. Arafat and four thousand loyalists were taken to safety in Tunisia. They would continue to terrorize Israel in the coming years. This time, Rabbi Goren was outraged at the Israeli government. In his mind, there was no requirement to allow the PLO fighters to escape since Israeli forces were located on only one side of the siege. The IDF was not responsible for the PLO’s predicament. If the PLO wants to flee, he quipped, they should ask the splinter groups for an escape route. The moral burden here does not lie with the IDF. To the contrary, allowing the PLO leaders to leave under these circumstances made no sense. Each PLO terrorist is a

“violent pursuer” (rodef) whom Jewish law mandates we neutralize before they kill someone else. They are threats to Israel that must be eliminated. The international community’s inability to grasp this basic point doesn’t change our moral obligation.

Jewish military ethics compel us not to target noncombatants and allow them to flee from the battlefield. Yet they also demand from us to unflinchingly act against threatening enemies, like the PLO leaders stuck in Tripoli. If Yaakov’s sons would have targeted the enemy combatants in Shechem, their actions would have been entirely legitimate. Israel, Rabbi Goren argued, had no moral right to compromise on Israeli security.

That criticism, of course, could also be launched against Rabbi Goren himself for having supported the IDF in letting PLO terrorists out of Beirut. Arafat and his comrades were also dangerous pursuers in 1982. If we hadn’t let them escape from Beirut, the argument went, we wouldn’t have been back in the same place in 1983. When you go to war, your priority must be killing your enemies. Otherwise, don’t bother fighting at all. Indecisive actions just drag out a war and its suffering, and don’t allow for decisive accomplishment of one’s strategic goals.

Rabbi Goren’s claim that the “fourthside open” requirement applies only when the same country (in this case, Israel) besieges all four sides seems overly legalistic. After all, the residents of Tripoli were seemingly also entitled to some humanitarian relief. The “fourth-side open” requirement isn’t much of a moral obligation if it gets waived simply because other warring parties are doing the dirty work. Yet one could retort that the law demands compassionate relief, but there are limits to what we can be obligated to do when we don’t fully control the situation. By returning to Lebanon, one might further argue, Arafat and others lost their right to flee again.

Ultimately, given its disputed status, it seems more compelling to conclude that the idea of leaving a fourth-side open is a general principle of Jewish

military ethics but not a bona fide commandment. Such an approach is a meaningful compromise to the heated disputes over the “fourth-side open” rule in rabbinic sources. The principle asserts that one should do everything they reasonably can to reduce the human costs of war, even on the enemy side. This includes allowing noncombatants to escape before the onset of hostilities and, when possible, during the conflict. Even combatants may flee, provided that this doesn’t overly undermine the war efforts. Yet it allows for important critical caveats, including preserving an element of surprise and ensuring the removal of the threat against the people. This remains our priority.

Judaism offers the world a multi-value framework for thinking about the moral complexities of warfare. It encourages, when possible, to allow the enemy to clear their people from the battleground. Its sound military strategy helps diplomatically, and most fundamentally, helps reduce unnecessary bloodshed. Yet our mesorah prioritizes the imperative of self-defense. Leaving sworn enemies alive so they can fight us again at a later point is a moral failing. Alas, diplomatic pressure and military limitations have repeatedly made that necessary. Yet we should resist, as much as possible, any outcome that prevents us from accomplishing our primary goal of protecting our people. This happened in 1983. One hopes this won’t be repeated in 2024.

20 JEWISH ACTION Summer 5784/2024

Photo: Nati Harnik/Israel Government Press Office

Rabbi Dovid Bashevkin speaks with Rabbi Yosef Zvi Rimon

COVER STORY

Summer 5784/2024 JEWISH ACTION

Photo: Ariel Jerozolimski

Rabbi Yosef Zvi Rimon is an internationally acclaimed posek, author, educator and lecturer. Individuals and communities from around the globe turn to him with complex questions in halachah, the responses to which have been pivotal in helping shape the contemporary Jewish world. Rabbi Rimon is president of World Mizrachi, rosh yeshivah of Lev Academic Center (JCT), chief rabbi of Gush Etzion and community rabbi of Alon Shvut South. Rabbi Rimon is the author of Hilchot Tzava, a practical guide to halachah for soldiers in the army.

Since October 7, he has visited with thousands of soldiers, answering their she’eilot and providing chizuk. Additionally, many hundreds of soldiers in Gaza, who are without cell phones due to army regulations, have sent letters to the rav with their questions.

After meeting countless soldiers and visiting dozens of bases, Rabbi Rimon says, “I have a suit jacket that I don’t ever want to take off except for dry cleaning—I have hugged thousands of soldiers wearing it; it is very holy!”

Rabbi Yosef Zvi Rimon at an army base.

Photos courtesy of the Office of Rabbi Yosef Zvi Rimon, unless indicated otherwise

Rabbi Dovid Bashevkin

What are some of the most frequently asked questions you have gotten since October 7 from soldiers?

Rabbi Yosef Zvi Rimon:

The most common question I receive is from soldiers in Gaza who have a short break and want to return home on Shabbat. Are they allowed to do so? To answer this question, one must take various things into account. One consideration is pikuach nefesh, saving a life, which overrides the restrictions of Shabbat. But in this case, since it’s wartime, it may not only be personal pikuach nefesh but also pikuach nefesh of the tzibbur, the public at large. The halachot during wartime are obviously different. Even if there is a slight possibility that a break will alleviate some of the soldier’s stress and help him be more effective when he returns to the battlefield, we can permit him to go home on Shabbat.

But suspending the laws of Shabbat depends on many factors. What exactly is going on in the war? How much time was the soldier on the battlefield? How long is his break? Can we give him a break at a different time?

There are lots of questions that need to be considered before allowing a soldier to go home on Shabbat.

I would like to share a story. At one point, a logistics officer called me and asked the following: Soldiers who had been in Gaza for some time were given an eighteen-hour break. They were being sent to an army center in Ashkelon where they would be able to shower, relax and visit with their family, and the next day they would return to Gaza.

They were told they could leave Gaza on Friday at noon and return on Shabbat morning. The question was as follows: Their wives, children and parents wanted to visit, but if they drove to see the soldiers in Ashkelon, they would not make it back on time for Shabbat. These soldiers hadn’t seen their family members for weeks and had no idea how long the fighting in Gaza would go on. If they got a break but were unable to visit with family, they might feel depressed and discouraged. For a soldier, mood and morale can have life-and-death implications. In light of the situation, according to halachah, could the families drive home on Shabbat?

I asked the officer if there was a possibility the families could stay in

Rav Rimon published this practical guide to the halachot of war that perfectly fits into the pants pocket of an IDF uniform. There is precedent for a sefer like this—the Chafetz Chaim wrote Sefer Machaneh Yisrael for Jewish soldiers in the Russian army.

a nearby hotel for Shabbat, but the IDF coordinator said the army could not pay for that.

It was Thursday evening when I was speaking to the officer, and I was in my car driving to another base. In general, when I travel to army bases, only my assistant is in the car with me. Often, a group [on a solidarity mission] accompanies me by bus. However, this particular time, members of a solidarity mission from Congregation

Rabbi Dovid Bashevkin, a member of the Jewish Action Editorial Committee, is the founder of 18Forty, a media site discussing big Jewish ideas. Some of the content in this article is from the 18Forty podcast entitled "Yosef Zvi Rimon: What Happens to Jewish Law During War?"

22 JEWISH ACTION Summer 5784/2024

THE HIDDEN LIGHT OF THE GALILEE

Bnai Yeshurun in New Jersey asked if they could accompany me in my car. The rabbi of the shul, who was seated next to me, heard the conversation. He turned to me and said: “We would be happy to pay for the hotel.” The shul ended up funding a wonderful Shabbat for our soldiers and their families. While the hotels were all closed in Ashkelon, we were able to find a guesthouse that could accommodate 180 people, including the soldiers, their wives and children. A team of volunteers brought food and toiletries, and even toys and books for the children. Thanks to the generosity of this Teaneck shul, these soldiers and their families were able to enjoy a very moving and meaningful Shabbat together.

The officer in charge, Yitzhak Schwartz, who managed to uplift the soldiers and their wives over Shabbat, was injured a few days later. Baruch Hashem, his life was saved, but he suffered a serious spinal cord injury. When I visited him in the hospital, he said: “Pray for me.” “Of course,” I replied. Then he told me: “Rabbi, pray that I get well soon. I have to go back to Gaza to be with my soldiers.”

RB: What a moving story! Can the Rav elaborate on any she’eilot related to tefillah and the battlefield?

I can personally attest that you can really feel the Shechinah [in the military camps]. I believe this is because it is a milchemet mitzvah, an obligatory war of self-defense, and G-d is with us.

RR: Yes, of course.

Minyanim are often set up in tents, and the army brings sifrei Torah for some of the minyanim. I was asked the following: Between fifteen to twenty chayalim come together for a minyan, but there are four chayalim who cannot come to the tent because they are required to remain at their posts some 200 meters (600 feet) away. Can the minyan bring the sefer Torah from the tent to those four soldiers and daven there with them? This way, they won’t miss keriat HaTorah.

Generally, one is not supposed to transport a Torah scroll from its usual location to be used in another location for temporary use. This is because it is considered disrespectful to take a Torah to those who need it; rather,

those who need it should come to the Torah. The soldier asked me what to do. I told them, “First of all, there is a machloket. What happens if you don’t go to the sefer Torah not because you don’t want to, but because you don’t have the ability to do so? Let’s say you are in jail; may one bring a sefer Torah to jail? There are Rishonim who permit bringing the Torah in such a case. There are other Rishonim who do not permit it. Secondly, perhaps in this particular case the sefer Torah might not be considered to have a set location, as it is housed in a tent in a war zone. Finally, we can argue the following: The Talmud Yerushalmi states that there is an exception to the rule: one can take a sefer Torah to an adam chashuv, a prominent person. Who is an adam chashuv? Usually, we

24 JEWISH ACTION Summer 5784/2024

Rabbi Rimon (center) visiting with soldiers.

. . . the world does not understand that our army has the highest level of morality. No one comes close to us in this regard.

would say a talmid chacham, a rabbi, the president of a country or some other high-level official. But I told him I believe that a soldier who sacrifices his life to protect Am Yisrael . . . he is the most significant adam chashuv And therefore, I said, it is acceptable to bring the sefer Torah to the chayalim.

RB: That is incredibly moving.

RR: Here is another question concerning tefillah that came up recently.

As you know, during the tefillah of Tachanun, the custom is to bow one’s head. The Rokei’ach writes that one should not bow during Tachanun if the room does not have a Torah scroll. He cites the verse in Yehoshua 7:6 as evidence of this: “Yehoshua thereupon rent his clothes. He and the elders of Israel lay until evening with their faces to the ground in front of the Ark of G-d.” Seemingly, bowing is necessary in front of the Ark of G-d [which can also apply when there is a sefer Torah].

One soldier asked the following: In our particular camp in Gaza, we do not have a sefer Torah with us. Should we bow during Tachanun?

Based on the Rokei’ach, there is room to argue that bowing is required in every place where there is a revelation of the Shechinah, as we find with Avraham Avinu (Bereishit 17:3) and in many other places in Tanach. The Torah itself attests that the Shechinah is found in a Jewish military camp, as the pasuk (Devarim 23:15) states: “Since Hashem, your G-d, moves about in your camp to protect you and to deliver your enemies to you, let your camp be holy; let [G-d] not find anything unseemly among you and turn away from you.” I therefore responded that they should bow even without a sefer Torah

With all the visits I have made to

military camps these last few months, I can personally attest that you can really feel the Shechinah there. I believe this is because it is a milchemet mitzvah, an obligatory war of self-defense, and G-d is with us.

RB: That’s remarkable. I imagine you also received some unique questions regarding mourning and burial?

RR: There were many questions. What happens if only parts of a body are found and a burial takes place? Does the family sit shivah? And if they sit shivah and the rest of the body is found a few months later, what then? Does the family sit shivah again? These are questions that have not been asked for decades.

What happens if there is no body at all, just blood? This occurred in the tragic case of Daniel Perez, Hashem yinkom damo, the son of Rabbi Doron Perez.

All of these questions are terrible, and for years we were fortunate not to have to ask such questions.

RB: Have soldiers asked questions that inspire you?

RR: Most of the questions soldiers ask me or the stories they share with me inspire me! They indicate the extraordinarily high moral caliber of our army. I’ll give you an example. Soldiers in Jenin had a mission to destroy the home of a terrorist. They went to the building and saw that they could destroy the apartment in ten minutes. But they stayed a few hours. Why? They realized that if they would proceed with their plan, they would damage the whole building. If they worked for an hour, they would destroy the terrorist’s apartment and damage two surrounding apartments. They ended up working for a few hours so that the apartment of the terrorist would be destroyed without damaging surrounding property.

To me, this is very inspiring because the world fails to understand that our army

26 JEWISH ACTION Summer 5784/2024

Photo: Abir Sultan/Flash90

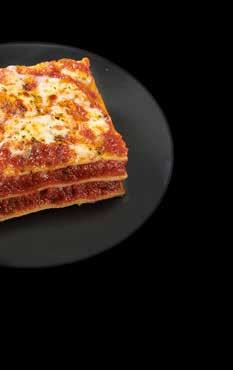

The best of Italian cuisine, ready-made and ready to heat

Savor Tuscanini’s irresistible Pronto Meals and enjoy an authentic Italian dinner, pronto. Open a box of pasta perfetta and taste the delicious culmination of a slow and meticulous culinary process. Heat and enjoy in 7 minutes. Pronto or not, here you go.

27 JEWISH ACTION

Macaroni & Cheese

Fettuccini

Alfredo

Spinach

Truff eMacaroni&Cheese Lasagna CheeseTortelloniwithMushroom A l fredo LA N D OF 350 + P A S SAT Find it in the freezer section

Tortelloni with BasilPesto

has the highest level of morality. No one comes close to us in this regard.

Those soldiers were in Jenin for a few hours. A few hours! I asked them: “If you stay a few hours, is it more of a risk?” They said, “Of course, it's a risk.” In this scenario, every minute in Jenin is a risk. I’m not sure they did the right thing—putting their lives at risk just to protect property. . . . But while I’m not convinced it was the right thing to do, one thing I am sure of—no nation, no army in the world, would do something like this.

Here’s another question that really moved me. A woman recently called me and said: “Rabbi, we are a young couple and we have been trying to get pregnant for a long time. I just got a positive answer that I’m pregnant.” I said, “B’sha’ah tovah!” Then she said: “My husband is in Gaza and he doesn’t have a phone, but once every ten days or so, he has access to a phone and then he has two minutes to talk to me. I know he’s going to call me in two more days. Rabbi, I long to tell him that I’m pregnant. I really want to, we’ve been waiting so long, but I don’t know if I’m allowed to. I know that the Rambam says that when a man goes to war, he should not think about his wife or his children, but only about the people of Israel.”

I ask you: is there another woman like this in the world?

What did I tell this woman?

I told her, “You know your husband better than anyone else. What do you think? If you tell him, will it make him feel stressed or will it make him really happy?” She thought for a moment and

said, “It depends on how I say it. If I cry, it will stress him out; if I say it happily, it will strengthen him.” I told her, “You have two days. Cry now, and stop crying in two days. When you feel that you can tell him happily, tell him.”

Rabbi, pray that I get well soon. I have to go back to Gaza to be with my soldiers.

So many people call me; I usually don’t know who they are or what happens after I give them a particular pesak. But some time later, a soldier called me. He said, “Do you remember a woman called to ask you how to tell her husband she’s pregnant? That husband is me! I want you to know how much it affected me. You really strengthened me and strengthened my motivation to fight—I have to protect my future child.”

RB: Last question. I’m curious what the Rav says to soldiers who don’t have the same resolve they might have had months ago at the beginning of the war?

RR: Indeed, we are in a very difficult situation. There are dead and wounded soldiers as well as hostages. We cry and we grieve. But in the midst of difficulty, one must constantly lift himself up and feel the greatness. We are the generation of redemption. We have seen so many miracles before our eyes, we know Hakadosh Baruch Hu is with us and that, with His help, we will win.

How do we know? Because throughout all of our history, every nation that tried to kill us is not here anymore. Vehi she’amdah—It is this that has stood by our fathers and us. Shelo echad bilvad amad aleinu lechaloteinu—For not only one has risen against us to annihilate us, but in every generation they rise against us to annihilate us. V’Hakadosh Baruch Hu matzileinu miyadam—But the Holy One, Blessed is He, rescues us from their hand. We know Hashem is with us, and with Am Yisrael unified, we are going to win.

28 JEWISH ACTION Summer 5784/2024

Soldiers in Gaza asked Rabbi Rimon if a sefer Torah could be brought to soldiers who could not leave their post. Photo: Phil Sussman/Flash90

No Need to Elbow Brown Rice Elbows Aside

No-mushy-no-gooey-flavorful-alt-flour pastas are here! Cook with Heaven & Earth’s surprisingly firm brown rice pastas, crafted by Italian artisans. Shaped with bronze-cut molds and slow dried at low temperatures, they hold their texture beautifully and absorb sauce nicely. Enjoy this better-for-you option as a main or side.

“love the texture, plus how I get the perfect al dente pasta in just minutes!”

-kosher.com

Heart.Works GLUTEN FREE

in Italy *See product packaging for recommended cooking time, as it may vary depending on the variety of pasta, such as penne, elbows, spaghetti, fettuccine, and rotini.

Crafted

Rabbi Shlomo Sobol received many she’eilot from members in his community serving in the Military Rabbinate, the Rabbanut Tzvait, who are involved in identifying and caring for the bodies of the murdered victims.

Photo: Nati Shohat/Flash90

As told to JA Staff

Rabbi Shlomo Sobol, rav of Kehillat Shaarei Yonah Menachem in the Buchman neighborhood of Modiin, leads a congregation comprised of some 350 families with roughly 200 soldiers. Jewish Action asked him to share some of the questions he’s received from his congregants who have been drafted over the past few months. Rabbi Sobol, who attended Yeshivat Mercaz HaRav and received semichah from Israel’s Chief Rabbinate, will often refer more challenging she’eilot to Rabbi Yaakov Ariel, Rabbi Asher Weiss or Rabbi Avigdor Nebenzahl.

I received quite a few requests for assistance from farmers in the South whose workers were drafted; without help, their crops were going to be ruined. We helped these farmers recruit volunteers, but we realized that some of the farmers were then selling the produce directly to consumers (leaving out the middleman) without taking terumot and ma’asrot. I suggested to the volunteers that they offer to separate terumot u’ma’asrot. In many cases it didn’t work. It was a challenging situation because we wanted to help the farmers, but at the same time we didn’t want people to eat produce from which terumot u’ma’asrot were not taken. I told community members that every time they buy produce from the North or the South (from a farmer or stand and not from a store), they must separate terumot u’ma’asrot themselves.

One of the more interesting questions that came up involved a soldier who was concerned about worrying his parents. He asked: “Am I allowed to lie to my parents and tell them I’m not in Gaza, even though I am?” I advised him to tell his parents the truth. And I added: “When you tell your parents, you should also get a berachah from them. A berachah from one’s parents is more significant than a berachah from a rebbi.” Even in times of war, there are she’eilot involving semachot, joyous occasions. A significant number of soldiers have asked about postponing their weddings. IDF soldiers often get a 24-hour break every few weeks. Soldiers ask me: “Should I get married during a break, or should I wait until after the war is over?” (At the start of the war, people thought it would be over in a few weeks or at most a few months.) Some soldiers ended up having backyard weddings while on leave for a day or two, and then returned to active duty.

30 JEWISH ACTION Summer 5784/2024

COVER STORY

As surprising as it sounds, I always tell engaged couples the same thing: “If you could make the wedding now, do it.” I sit with the kallah (whose chatan is in Gaza) and the two families and discuss it. Not everyone can make a wedding while on 24-hour leave from the army. Of course, in order to get married, one has to be in the right emotional state, so the most important thing is to verify that the kallah and chatan are prepared psychologically and emotionally for getting married in the midst of a war.

A few soldiers postponed their weddings. But many others did not.

There are valid reasons for not postponing a wedding. Rabbi Asher Weiss tells a remarkable story emphasizing this point. His rebbe, Rabbi Yekusiel Yehudah Halberstam, the Klausenburger Rebbe, who lost his wife and eventually all of his eleven children in the Holocaust, had an eldest son, Lipa. Nineteen-year-old Lipa, an ilui, was the apple of his father’s eye. Tragically, while Lipa did survive the Holocaust, he died of typhoid two weeks after the war ended. The Rebbe was crushed.

Rabbi Tzvi Hirsch Meisels, the Veitzener Dayan, who survived the war, shared with Rav Asher an incredible story, which Rav Asher had never heard from the Rebbe: In 1944, Rav Tzvi Hirsch was about to finalize the shidduch of his oldest daughter with the Rebbe’s son Lipa, when the Nazis invaded Hungary. The Rebbe decided to cancel the engagement party, which was scheduled for the following day, and wait for the storm to pass; no one could possibly have envisioned what the future held for Hungarian Jewry.

After the war, Rabbi Meisels heard that the Rebbe survived and was in the Foehrenwald DP camp. He quickly made his way there to reunite with the Rebbe. The first question the Rebbe asked the Veitzener Dayan was, “Did your daughter survive?” “Yes,” was Rabbi Meisel’s response, “and is Lipa alive?”

The Rebbe broke down crying and replied that Lipa had died a few weeks earlier. “Perhaps had we finalized that shidduch, the combined merit of two young tzaddikim would have kept Lipa alive.” The Rebbe deeply regretted pushing off the engagement.

For these young soldiers, says Rabbi Asher Weiss, leaving the army for a day or two and getting married is a great zechut. Hopefully, the combined merit of two young people planning to build a bayit ne’eman b’Yisrael will serve as a protection for both of them and enable the soldier to return home safely.

She’eilot have also come from members in our community serving in the Military Rabbinate, the Rabbanut Tzvait, who are involved in identifying and caring for the bodies of the murdered victims. A member [of this unit] told me that one of the most difficult experiences he had was collecting body parts and spilled blood for identification purposes, working for hours at this gut-wrenching job, only to discover later that all that he had collected belonged to a terrorist. Another righteous soldier serving in the Rabbanut Tzvait shared with me that before he began this type of work, a psychologist prepared him for what he would encounter. “You have to know that the smell of death is something you might carry with you for the rest of your life,” he told him. This soldier then told me something very powerful. “When I carried the body of a soldier, I didn’t smell death. I sensed the fragrance of Gan Eden.”

Members of the Rabbanut Tzvait asked if they could continue to collect bodies on Shabbat. Under normal circumstances, the answer would have been no. On Shabbat, a dead body is considered muktzah. But in the aftermath of October 7, it was an entirely different situation. For parents, finding out whether their child was alive or not was literally piku’ach nefesh It was a question of saving lives—the lives of emotionally distraught parents. Additionally, doing such work on Shabbat signified in a powerful way to fellow soldiers that we will work 24/7 to care for their bodies with dignity and respect should something, G-d forbid, happen to them.

Not surprisingly, I also received a lot of emunah questions—especially from those soldiers who dealt with the bodies. We all know that there is good and evil in this world, and while we all believe that Hashem runs the world, painful,

distressing sights are often too much to deal with. I don’t have the answers to those questioning their faith. I hug them. I sit quietly with them. Listening is always critical. I tell them: “We know Hashem is in charge of everything, and we believe in Him, but we are also allowed to complain to Him and to ask Him our questions openly and honestly.”

At the same time that there are questions, we also clearly see Yad Hashem. Even the very fact that the terrorists were able to do what they did was obviously the Divine Hand at work. It is inexplicable that the IDF—one of the strongest armies in the world—“died” for a few hours. Perhaps Hakadosh Baruch Hu wanted to reveal the strength of Am Yisrael. Many of us are in the habit of complaining about Millennials and Gen Z; the young generations spend so much time on smartphones, and we worry— what will be with them? But these young people suddenly rose up like lions, with mesirut nefesh and a light in their eyes, to defend Am Yisrael, exposing the diamond within the Jewish soul that was concealed all this time.

This is the ko’ach of Am Yisrael.

31 Summer 5784/2024 JEWISH ACTION

Photo: Oren Ben Hakoon/Flash90

32 JEWISH ACTION Summer 5784/2024