3 minute read

Drawing your attention to illuminated texts

By Arlene Stolnitz

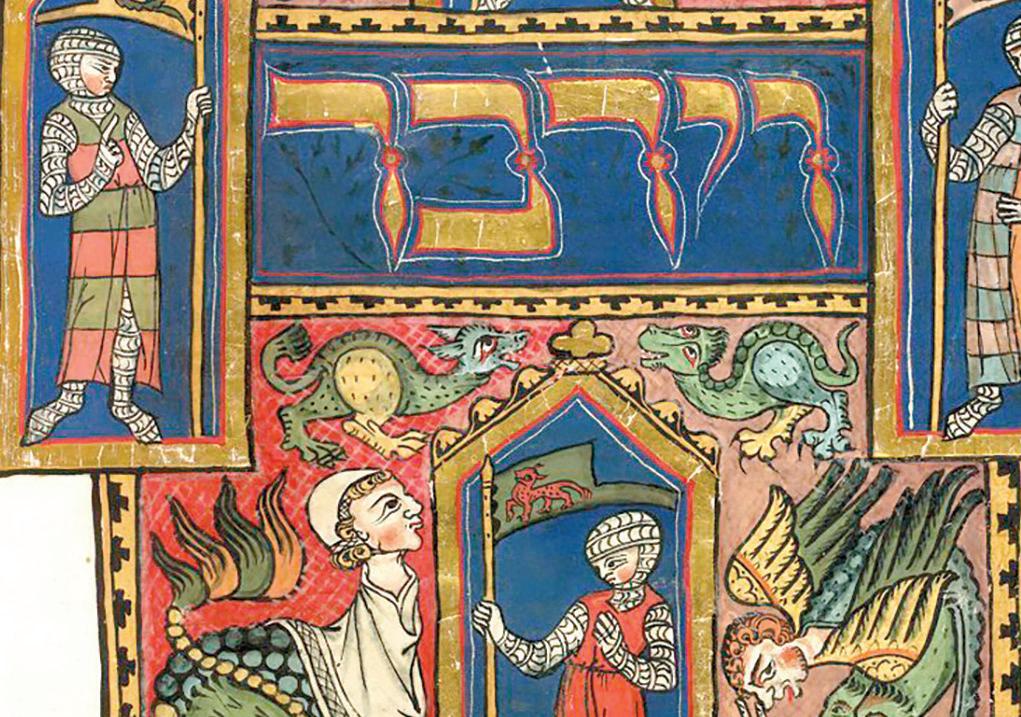

Just what are illuminated texts? My research revealed a fascinating history, mostly emanating from the medieval period. Illuminated texts were mainly commissioned by wealthy patrons. They were considered to be status symbols and were proudly displayed by their owners. These texts were decorated manuscripts, hand painted and adorned with precious metals in gold and silver.

Traditionally, the ban on any figurative decoration in Judaism has been a long-held view. But a question in my mind kept coming up! Although I knew about the biblical ban against graven images, the view about decoration of texts seemed excessive, and I wondered. So, I did some research, which took me back to biblical times.

According to what I read, artistic endeavor was very much appreciated in biblical times. God instructed Moses exactly how to decorate the holy Tabernacle. The Ark of the Covenant was to be modeled after the throne of God in heaven, adorned with precious stones and metals. Detailed descriptions as to the use of cherubim and other figures were explicitly described.

As I continued my research, further readings confirmed my question. In the Middle Ages, there was a change of thought about using artwork to express devotion. Our sages began to see art as a means of enhancing spirituality rather than as a detriment or distraction. They did not interpret the illumination of text as a violation of the ban on graven imagery. Communities in the Near East and Europe had become the center of creativity, and Jewish scribes and artists were influenced by these countries. They chose to adorn their Bibles and other religious documents with decorative motifs.

As we view these texts today, we can easily see the Muslim, Near Eastern, as well as Christian European influences.

Spanish-Jewish philosopher Profiat Duran (d. 1414) explains how art can inspire and stimulate holiness and learning:

“Study should always be in beautiful books, pleasant for their beauty and the splendour of their scripts and parchments, with elegant ornament and covers ... It is also obligatory and appropriate to enhance the books of God and to direct oneself to their beauty, splendour and loveliness. Just as God wished to adorn the place of His Sanctuary with gold, silver and precious stones, so is this appropriate for His holy books, especially for the book that is ‘His Sanctuary.’” (smarthistory.org)

While researching the topic, I became acutely aware of the use of micrography (see my last column) and how it was used in illuminated texts.

We are fortunate that many of these precious Judaic, Christian and Muslim artifacts have survived. They are housed in prestigious museums, including The British Library in London and The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

If you are interested in this subject — which I found fascinating — I suggest looking up information about a few of these illuminated texts. A complex, but interesting subject, there is much to learn about the history of our Judaic heritage.

• Lisbon Bible c.1482

• Duke of Sussex German Pentateuch c. 1425

• First Gaster Bible 9th, 10th C.E.

• San’a Pentateuch 7th-8th century C.E.

A future topic will cover the work of the scribe. I hope you will stay tuned!

Arlene Stolnitz, the “Jewish Music” contributor to Federation papers for the past eight years, has started a new series focusing on Judaic Folk Art. It will appear in Federation newspapers on an irregular basis. Stolnitz, a native of Rochester, New York, is a retired educator and lives in Venice, Florida.