RALPH ANDERSON

EXHIBITING AT JGM GALLERY LONDON

23 OCTOBER TO 30 NOVEMBER 2024

JGM GALLERY PRESENTS DIG AN EXHIBITION OF PAINTINGS BY GLASGOW-BORN ARTIST, RALPH ANDERSON.

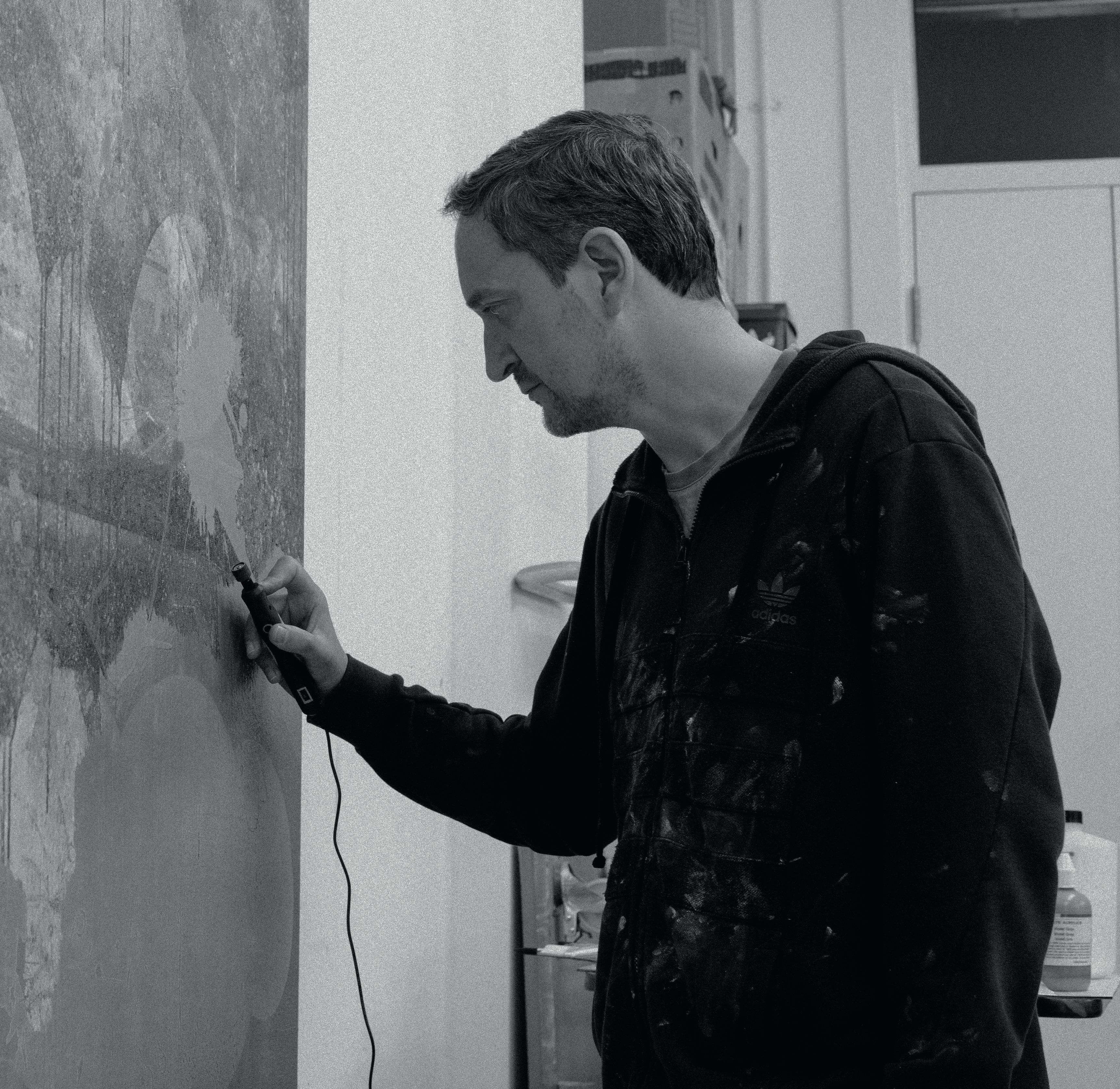

ANDERSON'S USE OF A ROTARY TOOL TO SAND DOWN LAYERS OF PAINT STRIKES A LINE OF CONTINUITY BETWEEN HIS EARLY AND CURRENT PRACTICE. THE EXHIBITION'S TITLE TAKES INSPIRATION FROM THIS TECHNIQUE. THE RESULTING SCRATCHES, INSCRIPTIONS AND HOLLOWS, WHICH FIGURATIVELY 'DIG' THROUGH THE SURFACE OF THESE PAINTINGS, ARE THE ARTIST'S PRIMARY MOTIFS IN THIS EXHIBITION.

ANDERSON REFERS TO THESE WORKS AS ECHO PAINTINGS, A TERM USED BY WALTER SICKERT TO DESCRIBE A SERIES HE MADE LATE IN HIS CAREER, IN WHICH HE WOULD APPROPRIATE BLACK AND WHITE ILLUSTRATIONS FROM MID-VICTORIAN JOURNALS, AND THEN TRANSFORM THEM INTO VIBRANT PAINTINGS. IN DIG , ANDERSON TAKES A SIMILAR CONCEPTUAL APPROACH, COPYING LANDSCAPES THAT HE PRODUCED IN 2006 AND 2007, THE IMAGERY AND ATTITUDE OF THESE EARLIER WORKS RESURFACING LIKE ECHOES OF THE PAST. AS THIS SERIES DEVELOPED, HE BEGAN TO INCORPORATE PHOTOGRAPHS FROM EVERYDAY LIFE, USING THIS NEW TECHNIQUE TO CONVEY IMPRESSIONS OF MEMORY AND TIME.

IN ARCHAEOLOGICAL TERMS, A 'DIG' DISPLACES LAYERS OF EARTH TO UNCOVER THE REMAINS OF HISTORIC CIVILISATIONS, AND THROUGH THIS ACT, RESTORE OUR CULTURAL MEMORY. IN THIS SENSE, ONE DIGS WHEN THERE IS SOMETHING TO RECOVER, BUT ALSO WHEN THERE IS SOMETHING TO BURY OR DISPOSE OF. ANDERSON'S PROCESS CAN BE UNDERSTOOD WITHIN THIS CONTEXT, AS A DIALECTIC OF BOTH ADDITION AND SUBTRACTION. BY EXCAVATING THE STRATA OF HIS PAINTINGS, AS SEEN IN THE ERODED FINISH OF LLANDUDNO PROMENADE , ANDERSON REMOVES HIS EARLIER MARKINGS WHILST CREATING A NEW IMAGE FROM THEIR REMAINS. HIS ABRASIVE TREATMENT DISTORTS FIGURES AND ARCHITECTURAL ELEMENTS, PERHAPS SUGGESTING AN IRREVERANCE FOR THE REALIST TRADITION. IT IS AS THOUGH HE CONSIDERS THIS MANNER OF REPRESENTATION TO BE A FRAGMENT FROM A GRADUALLY DISINTEGRATING PAST. YET, BY EXTRACTING FIGURATIVE FEATURES FROM BENEATH THE BLOTCHES AND STAINS OF PAINT, ANDERSON RENEWS THE RELEVANCE OF THE REALIST TRADITION, AS WOULD AN ARCHAEOLOGIST WITH THE ARTEFACTS OF AN ANCIENT CIVILISATION.

ABSTRACTION AND MORE TRADITIONAL GENRES, SUCH AS LANDSCAPE, PORTRAITURE AND STILL LIFE, HAVE AN ALMOST COMBATIVE RELATIONSHIP IN DIG , THE FORMER OVERLAPPING AND DISFIGURING THE OTHERS. AS TIME PASSES, THE MATTER OF OBJECTS AND BODIES DETERIORATE, AS DOES OUR MEMORY OF THEM. THE PAINTINGS IN DIG SHOW ANDERSON TO BE WORKING WITH AN INTEGRATED UNDERSTANDING OF THIS PROCESS, IN WHICH HE SIMULATES, THROUGH HIS ABSTRACTIONS, THE APPEARANCE OF THREADBARE FABRIC, A WORN PATINA OR OTHER FORMS OF NATURAL DECAY. HOWEVER, THE REAPPEARANCE OF TRADITIONAL GENRES IN ANDERSON'S PAINTINGS, UNCOVERED THROUGH THE 'DIGGING' PROCESS, DEMONSTRATES THEIR RELEVANCE TO HIS ARTISTIC PRACTICE.

JENNIFER GUERRINI MARALDI, DIRECTOR OF JGM GALLERY, SAYS THAT “ THE SUCCESS OF THESE WORKS IS THE REWARD RALPH DESERVES FOR CONTINUALLY PUSHING THE BOUNDARIES OF HIS PRACTICE. I AM CONFIDENT THAT THESE ECHO PAINTINGS WILL SOLIDIFY HIS PLACE AS AN ARTIST OF TRUE SIGNIFICANCE. ”

Ralph Anderson in his South London studio, 2024. Image courtesy of Julius Killerby.

FOREWORD

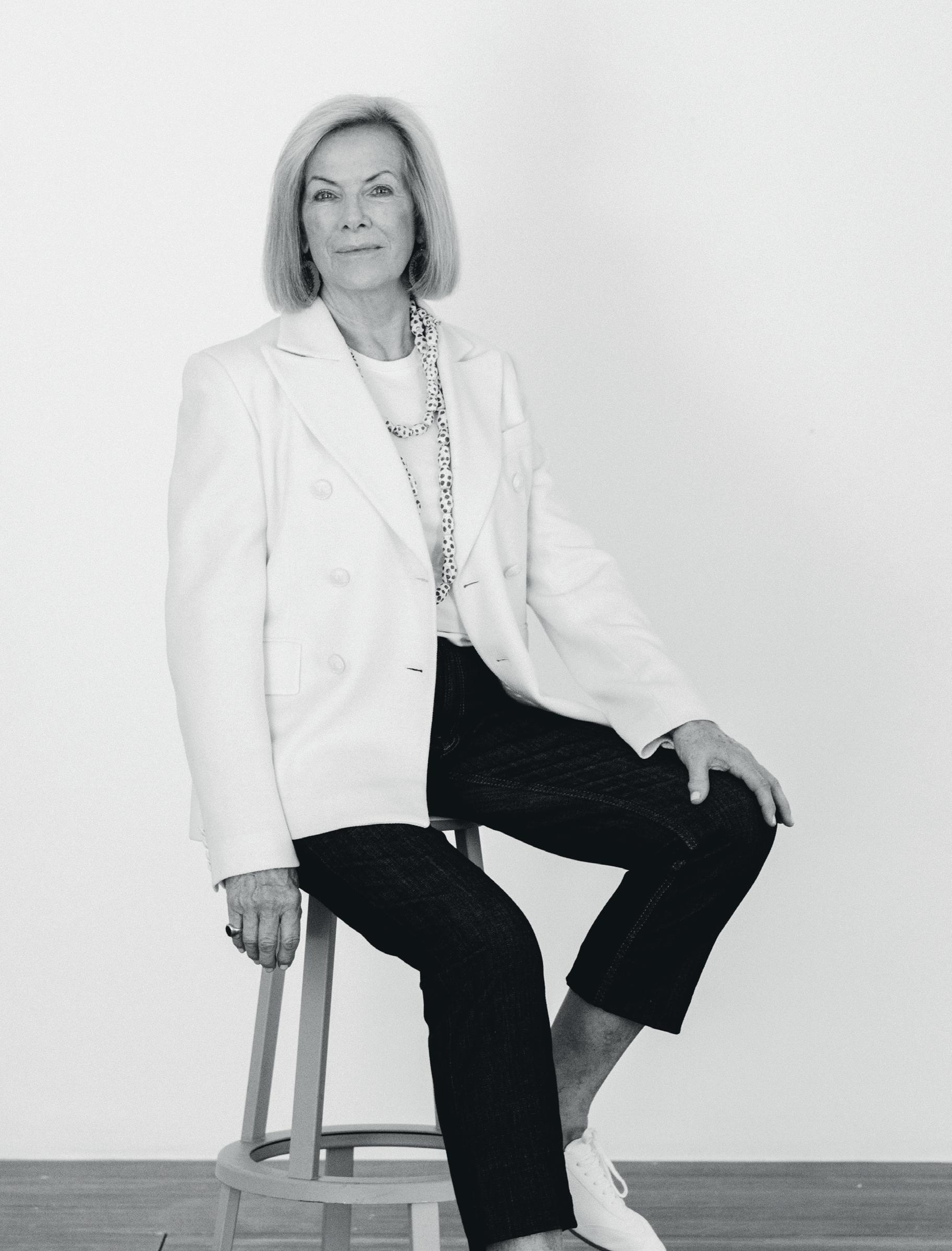

by JENNIFER GUERRINI MARALDI

RALPH ANDERSON was the first artist to join the JGM Gallery roster. In 2017 he exhibited Lucent Umbra , a dazzling suite of works, which in their quality and vision, set the tone for JGM. He was, in a sense, the first pillar upon which our gallery identity was built, and I could not be prouder to see him achieve what is, in my opinion, his magnum opus - the Echo Paintings.

Dig demonstrates Ralph's mastery of various styles and techniques. Though his oeuvre is characterised by the constant reconfiguration of these aesthetic languages, the paintings he creates are always distinctly his. That is, they are optimistic, conceptually deep, and flawlessly executed.

As their namesake suggests, I see echoes of lives lived in these paintings - mine, Ralph's, the audience's. In the powdered pigment and coarse surfaces, Ralph has found a profound metaphor for the accumulation of time and the indistinctness of memory. This indistinctness has another effect, which is to universalise the image, inviting the viewer to superimpose their experiences onto the painting before them. As Ralph says, “I might put meaning in, but I do not want that to dictate the way that the painting feels. Every viewer has their own history.”

The success of these works is the reward Ralph deserves for continually pushing the boundaries of his practice. I am confident that these Echo Paintings will solidify his place as an artist of true significance.

Jennifer Guerrini Maraldi, 2024. Image courtesy of Julius Killerby.

BY CHLOE REDSTON

ARCHAEOLOGY OF FORM

RALPH ANDERSON’S latest body of work, the development and culmination of previous approaches, is distinguishable for the singularity of the technique he employs. Drawing on familiar themes of landscape painting, and human relationships to environment, he begins with a representational image, gradually manipulating it through layers upon layers of paint, varying the colour, the tonality, at the same time attacking the surface with expressive, gestural marks – “messing with the canvas”. When the original image has been abstracted to the point of obscurity, Anderson commences the meticulous process of ‘excavation’. Using a rotary tool, he effaces the surface, gradually sanding through the many accumulations of paint in an experiential process which somewhat resembles the act of ‘digging’. The result sees the original image partially obscured by paint, only to be uncovered as an unfaithful echo. In the process of understanding Anderson’s work, the viewer is confronted by a series of antitheses, between that of the expressive and considered mark; rationalisation and obfuscation; memorialisation and erasure.

Originally titling these new works as his ‘Echo Paintings’, Anderson takes partial inspiration from the work of Walter Sickert, whose retrospective he encountered at Tate Britain (2022). Towards the end of his career (1930s), Sickert produced a series of works based on Victorian engravings and press-cuttings which he entitled ‘Echoes’. Retaining elements of flattened perspective and the stark tonal contrasts of simplified forms, his appropriation and transformation of black and white illustrations from forgotten journals into vivid images on the canvas, creates an almost abstract effect in his finished paintings. It is a similar dialogue between the ages, coupled with a disregard for a hierarchy of form, which so permeates Anderson’s new work. Building on themes explored in his previous solo exhibition at JGM Gallery, ID in which Anderson reproduced the abstract forms of urban graffiti found in his local South London environment by scratching and defacing the surface of a painted landscape, his initial approach to the series had its roots in pure abstraction, or rather, mark-making. However, somewhat influenced by the work of Sickert, Anderson began to revisit works from his own oeuvre, incorporating them into his new practice. The first example of this, entitled The Barn (2024), sees a representational image of a barn, painted some 20 years prior, “reverberating through history and re-emerging” as an echo in the present. It is not, however, a mere iteration of the past but rather transformed by a process which Anderson describes as “memories of an approach to making.” In his seminal essay, The Painter of Modern Life, often attributed to being one of Modernism’s founding texts, Charles Baudelaire recognises that past and present exist in reciprocal dialogue. He defines modernity as “the ephemeral, the fugitive, the contingent, the half of art whose other half is the eternal and the immutable. Every old master has had his own modernity.” In a Baudelairean sense, therefore, it is essential to look to the past in the pursuit of the definition of the present. In a similar vein, Anderson’s acknowledgement of the past, coupled with a unique blend of personal meaning, imbues his work with a heightened sense of contemporary relevance.

In each of the works in Dig there is a tension between the processes of memorialisation and erasure which is carried out by the similarly opposing expressive and measured forces, as in Llandudno Promenade (2024). Though initially representational, Anderson’s marks become gradually more evocative, using broad gestures to mark the canvas, subsequently adorning his work with an inimitable quality. This articulates a contrast of form: whilst stemming from the same inherent action of marking the surface, the urge to rationalise, introduced by hints of realism, is obscured and interrupted by the physicality of the asemic paint. These marks, which evade meaning altogether, instead favouring mere allusion in a deconstruction of representation, seem at times to destabilise rather than consolidate the past, even as they invoke it. In archaeological terms, a ‘dig’ displaces layers of earth and the deposits of time, to reclaim the remains of history – a metaphor which can be extended to Anderson’s work. His erasure of said marks is intentional; it is a calculated process. Though at first seemingly contrary to our presupposed associations of an inherently destructive act, his painstaking removal of layers of paint, often conducted over many months, becomes emblematic of a fragmentary recollection of the past. It is as though the gradual nature of the practice, combined with the haziness of the final product, enacts the indistinctness of memory. As such, the physical act of digging mirrors a psychological one, with Anderson grasping at the remnants of a forgotten past. The action simultaneously parallels the abrasive, and yet, revelatory process of archaeological excavation, creating a texture which mirrors that of patina, or perhaps, weathered walls, thus forming a double-edged allusion. This, paradoxically, lends the work an organic sense of construction, subsequently alluding to a generalised past via the lens of natural decay. Anderson therefore

establishes a tension between the at once generative and erosive power of the artist’s mark which plays out through a self-referential action.

The “archaeology of forms” which Anderson establishes within these works, coupled with the layering and indistinct blurring of said elements, further reinforces a dialogue which exists within his oeuvre. In Anderson’s words: “Archaeology is about uncovering; you are trying to understand and rationalise what you are finding. I think that the difference with what I am doing is I am uncovering my own marks, my own drawings. So, I know exactly what's there. I know what I'm going to uncover, but not exactly how it's going to play out.”

As such, Anderson situates an interpretation of his practice within the realm of personal experience. There is a point, however, at which Anderson is able to translate the individual into the collective. Though citing specific sources – a landscape favoured by Danish painter Asper Jorn in Julsø (2024), or the blurred figures in Llandudno Promenade (2024), or even the depiction of the artist’s wife, Alice Wilson, in Waiting for a Kingfisher (2024) – in each instance, Anderson, extricates the familiar and exalts it to the eminence of the memorable, the archetypal. For Anderson, “because it's a recognisable form in painting, it frees me to just throw paint at it and see what happens. For the viewer, it's also a recognisable object which makes it more approachable and allows them to enter the painting, and read into it whatever they'd like to.” In referencing the archetype, Anderson addresses the collective unconscious, leaving “the painting open – open to interpretation or just open to individual experience.” Just as the artist can be perceived as the translator of life, so too can we consider the task of interpretation as one of translation. At which point, artistic intention becomes somewhat irrelevant: “it doesn’t matter what the artists intend, or don’t intend, for their works to be interpreted.” Anderson appeals to ambiguity, an effect heightened by the inclusion of familiar genres of painting, and by his ‘excavation’ technique. Conversely, the experiential is transferred to the viewer. We are, in Anderson’s works, immersed within the composition – confronted by an untranslatable experience.

FOOTNOTES

Ralph Anderson (in conversation with the author), 2024.

Cf. Tate Britain, Walter Sickert Exhibition Guide (Tate Britain, 2022), https:// www.tate.org.uk/whatson/tate-britain/walter-sickert/exhibition-guide (accessed 27 September 2024).

Ralph Anderson (in conversation with the author), 2024.

Ibid.

Charles Baudelaire, The Painter of Modern Life (1863), in Jonathan Mayne (ed.) (trans.), The Painter of Modern Life and Other Essays (London: Phaidon, 1995), 13.

Mary Jacobus, Reading Cy Twombly: Poetry in Paint (Princeton University Press, 2016), 36.

Ralph Anderson (in conversation with the author), 2024.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Susan Sontag, Against Interpretation (Farrar, Straus & Giroux', 1966), 6.

In Conversation with RALPH ANDERSON

CR What led you to create this series, and what are your biggest inspirations and influences?

RA I find that a lot of my work has a natural progression, so this body of work is a development from previous series of works. I have been developing these paintings for at least two years now, and inspirations come from all over the place. I am not inspired by one specific painter or artist necessarily – my inspirations also come from life, as well as art.

CR Do you primarily work from photographs or life, and what effect does that have on the end result?

RA I mainly work from photography, rarely from life. Sometimes I make drawings from life but they rarely come into my art practice. I quite like working from photography just because it feels image based. People also relate to photography more and through it I can more easily play with the composition. So, even if I am working directly from a photograph or an image, I'll then redraw it, alter the composition, maybe take out or add things. But the basis is that photographic image.

CR How has your personal relationship to Scotland influenced your work?

RA I don't know. I mean, it has influenced me. It makes me who I am, I suppose, and I still spend a lot of time up there. That has probably influenced the landscapes in my work, and my relationship to them. So, I sort of understand nature and landscape. Growing up there, I was split between the city and the countryside. I used to live with my grandparents and they would always have me out chopping wood, or fishing, or walking in the hills. I grew up around nature, but also spent a lot of my childhood in the city as well. So I don't know... it provided a balance.

CR Does your approach to landscape painting offer a form of escapism?

process – adding that other element – brought this new meaning to the work, and brought it all together. So now I start off with the image and it becomes quite detailed work because that image has to hold all the various processes. While I'm doing that, I'm throwing paint on it, blocking whole colours out, messing with the canvas, dripping paint on it, rubbing it back. Then the whole painting transforms into something else. I'll then sand it meticulously, bit by bit, and take the surface off again. I love the result and what I am left with.

CR In archaeological terms, a dig displaces layers of earth to uncover the remains of historic civilisations. In this way, at least to me, the physical act reflects the psychological aspect of uncovering and reclaiming memory. What are your thoughts on the experiential process of excavation?

RA Yes, I agree with that. I want this relationship with time, memory and histories in the work, and obviously including imagery adds to that. In the excavation process, there's a relationship with archaeology but at the same time it's completely different because I'm uncovering things that I've done, that I've put on the canvas, that I've added to the painting. Archaeology is about uncovering; you are trying to understand and rationalise what you are finding. I think that the difference with what I am doing is I am uncovering my own marks, my own drawings. So, I know exactly what's there. I know what I'm going to uncover, but not exactly how it's going to play out. The surprise is what's going to happen to what I've done? How are all these other marks and spills and colours going to alter and distort the original image? I sometimes think of it as baking or cooking; I'm adding all of these ingredients, but I don't know what it's going to taste like at the end. It's quite a strange process uncovering what I've already done and seeing what happens. But it's a deliberate process of destroying that image and then seeing what's left.

RA Not for me. Maybe for the viewer, but for me it's about realism, not escapism. It's about conveying some thought of where we are, where I am. I don't do this to escape; I do this to be part of the world.

CR What is your process? How does this perhaps differ from, or rather represent, the culmination of approaches you have taken in previous years?

RA The process for this is, simply put, building layers of paint and then stripping it all back. This came from my last show at JGM Gallery where I was trying to develop a technique to convey these carvings on walls and benches. I went through lots of different processes and then eventually started using sanders and rotary tools to cut through the surface of the paint, and ever since then I've wanted to develop that technique. Initially, I was very much just going... I wouldn't say abstract, but they were just paint on canvas. I tried different ways of scratching through it, drawing with the sander, taking the whole surface off. Eventually, I came to the point where adding a representational image to this

CR To me, in your work, the process of destruction seems more measured than the gestural process of application. Would you agree with this?

RA Yes, absolutely. The destructive process is meticulous and time consuming, and I'm just taking paint, bit by bit, off the canvas, whereas the gestural process is instant. It can be done in seconds.

CR I guess this also introduces the idea of erasure as a generative process. There is this kind of tension at play between the layering of paint which obscures the image beneath and the revelation which occurs via its removal. Do you think your work therefore subverts the usual expectations of painting?

RA I hope so. All good painting subverts people's expectations, otherwise what's the point? You want to always be coming up with something new or doing something new with the medium. Erasure has been used before in art, but yes, it was a process I came across and it just seemed to speak to me. I also think

that one usually focuses on evidence of the artist's hand at work. The complete reverse of that is destroying the artist's hand. With my process, you just get these shadows of the artist's hand or of the brush mark.

CR Making reference to Walter Sickert's appropriation and transformation of black and white illustrations from forgotten mid-Victorian journals, you originally referred to these works as Echo Paintings. Aligning with this practice of blending past and present, in what way do you make reference to previous works in your own oeuvre?

RA There was a fantastic Walter Sickert exhibition at the Tate the year before last, which I went to see. I absolutely loved it. I have been influenced by his work ever since I started painting. I used to do a lot of landscape painting when I first left university. I was trying to do a painting a day, like, just doing very quick small landscapes, and I was always looking at the way Sickert approached painting. Fast forward 20 years and I am still influenced by his work. During that Tate show, however, I never knew about this series based on mid-Victorian journals. I knew about his later work, which I've always loved because it brought a kind of postmodern style to painting, back in the 1920s or 30s. And he'd started taking these prints from the Victorian era, and it was these which he referred to as Echo Paintings. I was developing these works at the time and it just clicked. I was like “Oh, that's brilliant”, and so the term stuck with me for a long time after that, and I then then started calling these works Echo Paintings. At the same time, because the original works that I was developing were all abstract, when I started putting landscapes and imagery into them, I immediately went to paintings I'd done maybe eighteen years ago. I was looking at an abstract painting, and then a painting of a barn I did in 2006 just popped into my head and I thought, “Oh, that would look great in this.”

So I quickly started repainting and revisiting these old works of mine. That’s the “echo”. It's the same thing that Sickert was talking about. He was talking about these works that had been reverberating through history and re-emerging fifty years later. For me as well, these old paintings suddenly came back through my work, doing this almost twenty year cycle. However, I did not just want to repaint everything I'd painted before. So I thought I'd better start putting new imagery in there.

RA I'd hope so. I feel the viewer always brings their own history to the work anyway. Some are paintings of my wife, there are others of landscapes that I know very well... at the same time, for a viewer that doesn't know that person or doesn't know that landscape, they know people. They know faces. So, they'll put their own history into that. Then there are others where I have been deliberately going back to standard genres of paintings, like flower painting or portraiture, where for me, because it's a recognisable form in painting, it frees me to just throw paint at it and see what happens. For the viewer, it's also a recognisable object which makes it more approachable and allows them to enter the painting, and read into it whatever they'd like to.

CR Leading on from that, what then do you think is the role of the viewer in the construction of meaning, and where does this place you as the artist?

RA The viewer is very important and I've always wanted to leave my work open to the viewer's interpretation. I am not a fan of dictating meaning in my paintings. There might be meaning there and I might put meaning in, but I do not want that to dictate the way that the painting feels. Every viewer has their own history. Every viewer has their own level of understanding of art. Maybe they’re complete novices, but I'd always hope that they get something from the painting. I am not painting for an educated crowd necessarily. I am painting for friends from school or family or people that never really bother with art. So, it's for everybody. In my approach, I'm always trying to leave the painting open – open to interpretation or just open to individual experience.

“ I think there's this direct relationship with graffiti and mark-making in my work, but also just this presence of wanting to decorate, or wanting to add a layer of richness to life."

CR So, do you think with these works in particular you are uncovering elements through the lens of your own personal memory?

RA Yes, absolutely. I feel art or the art practice goes round in circles, and I have just done this massive twenty year circle. I am making works that I was making back then, but at the same time I am making works that I was making five or six years ago. It's memories of an approach to making, because I think that always develops and changes. Suddenly, I felt I was back in my mid twenties doing landscapes again and remembering what dragged me to that kind of work in the first place.

CR Through the presence of familiar or even archetypal elements of still life or landscape painting, do you think that these recollections possess the ability to metamorphose into a collective one?

CR So there are a number of tensions and dichotomies at play within these works, one of them being between the abstract and the representational. The presence of the representational elements invites a rationalisation process, which is partially obscured by gestural asemic marks. I guess, aside from visually enacting the indistinctness of memory, or recollection, do you think this breaks down a notion of formal hierarchies which exist within art?

RA Yes, I'd hope so. It's such an old conversation, abstraction and representation, and, in a way, when I first started painting, or even when I was born, abstract art had been and gone. There was, then, when I was at art school, a massive resurgence in representational painting. It was obviously a big deal when abstract painting came along, but I feel that now it's a part of the landscape of visual language. Abstraction and representation are both different languages, different approaches, but they both say the same thing at the same time. For me, putting them both together is personally quite natural. I was not really trying to say anything with it or make a big deal about these two different ways of painting. Throughout my career, I have been a representational painter and I have been an abstract painter, and in my mind, they're both very similar things – making these objects and making these paintings that hopefully reverberate through art history, or relate to things I'm thinking about. I quite like the fact that I've now got this process where both can co-exist. I want these works, however, to be read as abstract paintings. The representational imagery in them, for me, it's just like another layer, rather than an element which makes it representational.

CR So, the process of erasure then becomes emblematic of a fragmentary recollection of the past, which, in my opinion, simultaneously mirrors the effect of weathered walls and surfaces – the end product kind of creates a double-edged

allusion. Do you think this therefore aligns the abstract mark with a kind of graffiti aesthetic, similarly blending formal hierarchies?

RA In a way, yes. That graffiti aesthetic is so much a part of modern visual language now. It's been present in my work for a long time, where I've kind of been trying to develop it, or bring it into “fine art”, for want of a better phrase. I just see it as part of so many visual languages out there. It's something that, as a painter, I can use or bring in as I please. You mentioned weathered walls – old light, the patina. There's these modern visual references but also old ones: a worn carpet, a tapestry, or just a weathered mural on a wall, rather than high end graffiti. A lot of these different visual languages come through my paintings, which I love, because painting now is such a traditional art form, but at the same time such a relevant and current one. So, playing those two things off each other, I find it quite fascinating.

CR Do you think then this also makes reference to any of your previous exhibitions?

RA Yes, slightly, I think. I have taken that avenue more than in any of my previous bodies of work. In my last show at JGM Gallery, ID there was obviously an overt reference to graffiti, but a very specific form of it where it wasn’t spray paint or what you'd immediately think of as graffiti. It was about mark-making and gouging these initials and names on bricks and benches. And I was just more fascinated about that really basic raw mark-making, rather than graffiti as such and that then related to the landscape. The other thing with modern spray paint graffiti is it can be washed off or it can disappear over time. Whereas these ones I was finding were about one hundred and fifty and one hundred and sixty years old, and they’d become part of the landscape. So, in that show, it was landscape painting but I was also trying to bring these stories of the landscape and the people into the painting. These new works might reference it, but that whole show brought on this process. This way of making, gouging, that sort of cutting through the surface, is what has been developed in these new works. In a way, it's still that sort of semi-violent, destructive aesthetic almost.

CR If we are to take the ‘archaeological dig’ as an extended metaphor for this exhibition, what I find quite interesting when you're referencing graffiti, especially with regards to your exhibition, ID and how you found things that were, let’s say, one hundred and sixty years old, is that even in Pompeii and places like that – literally places that have been frozen in time – there's evidence of graffiti.

RA Oh, absolutely.

CR There’s evidence of people doing exactly the same things, like tagging their names. It demonstrates this kind of continuation; people have always been the same.

RA Yes, we don't like rules or being told not to do something, or even clean surfaces. You walk into a brand new clean room, you want to make it your own. You don't want to just live in a blank box. That reference to one hundred and sixty years – I was finding all these things locally from walks around South London, so I was not going to find marks much older than that. But yes, if you went to Pompeii or any ancient site, you'd find mark-making. Builders leave their marks as well all over these places. We want to leave our mark. We want to leave our identity there. So, the fact that humans have been doing this for thousands of years is not surprising because we've not changed in that time. We still want to make things our own. We want to disrupt this mechanised world we're in. I think there's this direct relationship with graffiti and mark-making in my work, but also just this presence of wanting to decorate, or wanting to add a layer of richness to life. You could call that graffiti or you could just call that, I don't know, something…

CR Human nature?

RA Human nature, yes.

CR So, leading on from that Ralph, you've also created portraits of both yourself and your wife, Alice Wilson, using this process, one of which was nominated for the 2024 Scottish Portrait Award. How, if at all, does portraiture change the conceptual implications of your process?

RA Firstly, it was an amazing honour to be nominated for the Portrait Awards – it was a complete surprise! I find it fascinating because when I started making these, it was just landscape paintings or landscape imagery that I was using. Perhaps that was just natural because I've always painted landscapes. It felt like the obvious thing for me to do. It was only after about five or six of them that I thought, “Why don't I do a portrait?” I've never painted portraits that much before so by doing that, it just opened this whole new world. I love it because it's as though portraiture has got its own history, as do, obviously, people. Whereas, a lot of the landscapes, even though I've put figures in them, they are just empty landscapes and it is about the world we live in maybe rather than the people we are. So with these figurative works, it's more about people.

CR Well we look forward to seeing these new works hung in the gallery, come October. Thank you very much for your time, Ralph.

RA Yes, I look forward to it as well. Thank you, Chloe.

courtesy of Benjamin Deakin.

Ralph Anderson in his South London studio, 2024. Image courtesy of Julius Killerby.

Abstracted, 2024, acrylic on linen, 95cm x 95cm

Wonderland, 2023, acrylic on jute, 60cm x 45cm

The Motorway 2024, acrylic on jute, 26cm x 36cm

Speyside, 2024, acrylic on linen, 135cm x 100cm

ALPH ANDERSON'S painting, Self Portrait In A Hawaiian Shirt was shortlisted for the 2024 Scottish Portrait Award and as a result could not be included in this exhibition.

The 2024 Scottish Portrait Awards

Self Portrait In A Hawaiian Shirt, 2024, acrylic on linen, 46cm x 36cm

Anderson, The Motorway (detail),

courtesy of Benjamin Deakin.

Artwork Photography: Benjamin Deakin.

© 2024 JGM Gallery.

All rights reserved. ISBN: 978-1-7385394-5-1.

Front cover: Ralph Anderson, Harlech (detail), 2024, acrylic on linen, 31cm x 36cm.

Back cover: Ralph Anderson's tools, 2024. Editorial design: Julius Killerby. Photography: Julius Killerby.