TRUE FICTION

CURATED BY JULIUS KILLERBY

WITH TEXT BY ANTONIA CRICHTON-BROWN

KONSTANTINOS ARGYROGLOU

CAI ARFON BELLIS

SHANE BERKERY

MINA FAIRCHILD

HUDDIE HAMPER

GALA HILLS

JULIUS KILLERBY

RICHARD LEWER

TOM NORRIS

CAYETANO SANZ DE SANTAMARIA

JGM GALLERY PRESENTS True Fiction an exhibition of works by ten figurative artists.

True Fiction explores the means through which the exhibiting artists abstract their subject, so as to convey a deeper and more wholistic understanding of it. Partly inspired by JGM Gallery's summer exhibition, Revelation & Concealment , which sought to uncover hidden aspects of the natural world, True Fiction turns instead toward the anthropocentric, examining the ways in which texture, composition and line, amongst other formal elements, may divulge complexities in the figure beyond superficial representation. It is the aim of this exhibition, as Francis Bacon once said, to “... trap appearance without making an illustration of it... ” and to affirm this as one “... of the great excitements of being a figurative artist... ” (Francis Bacon, in conversation with William Burroughs, 1982).

In his charcoal drawings, Pleasure Peak and Off The Top Rope and his heavily impastoed oil painting, Dance Dun Cai Arfon Bellis depicts innercity London raves. Often produced on location and in the midst of this communal commotion, Bellis blends exceptional draughtsmanship with the spontaneous interactions he has with those around him. Bellis translates accidental collisions or the spillage of someone's drink into figurative abstractions, which he uses to emphasise or blur the individuality of his subject, and to capture the dynamism of the event.

The degree to which Shane Berkery deviates from realism is in many

ways analogous to the indistinctness of memory. It is in the ways we embellish or forget aspects of our personal narrative that Berkery believes the most compelling imagery is to be found. In Induced Levitation the detailed rendering of certain objects, such as a toaster and pot lodged on the kitchenette bench, dissipate into preliminary outlines and sketches. Proportions are skewed and certain objects take compositional precedence over others. Paradoxically, this style of representation, though less than factually accurate, feels more vivid, for it mimics the ways in which the viewer might recall events from their own life. Moreover, the positioning of the figure − face down and suspended inches from the floor − charges this piece with the supernatural, and the omission of the subject's face induces a subtle trepidation in the viewer.

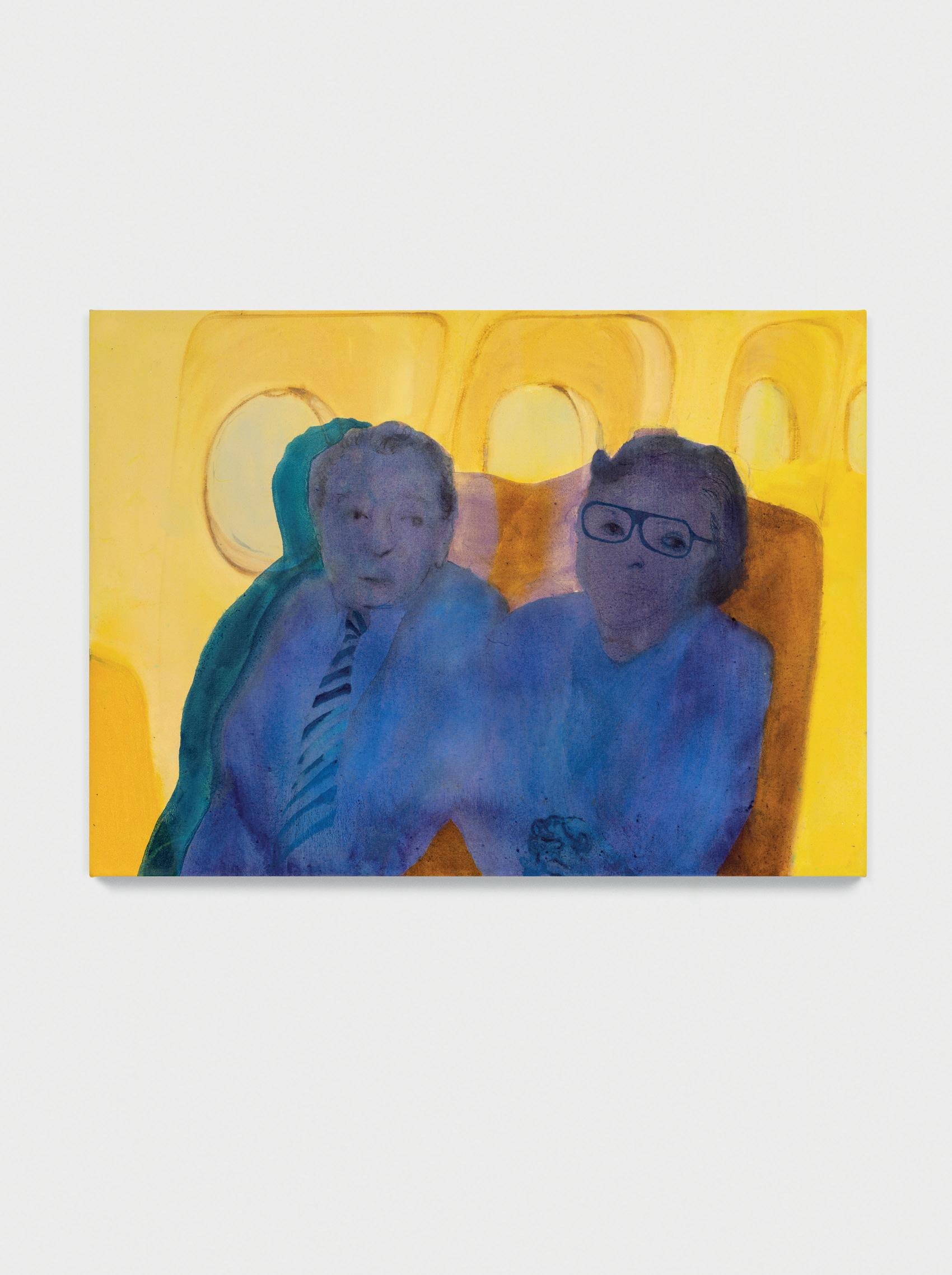

Memory and the way it can, within the mind's eye, intensify or distort past events, is also a key aspect of Konstantinos Argyroglou's largely autobiographical work. Painted with a pseudo-naivety, Aeroplane Memory, Beyond Myself and Grandpa's Easter Dinner possess a tender aesthetic that is consistent with their representation of moments from the artist's childhood. Blotched watercolour markings often contrast with hardedged forms, such variations in the application of paint reminiscent of a domestic arts practice or the world viewed through a child's gaze. As with Berkery's work, there is a correlation between this style of figuration and the vagueness of memory.

The Tempest , a ceramic vessel depicting figures within a landscape, marks

a significant stylistic progression for Tom Norris, wherein he combines the expressive mark-making that defined much of his earlier work with a newly adopted collage process. The collaged sections, often cut from photographs, are representational, however, as fragments they deny the viewer a complete impression of the original image. They thus appear like windows amongst the forested landscape which dominates much of the vessel's remaining surface area. Their disconnection from each other and from the rest of the gesturally rendered composition, establishes them more as formal, rather than representational, components of the work. In this way, Norris prioritises an overall harmonious aesthetic, rather than an image that invites narrative rationalisation.

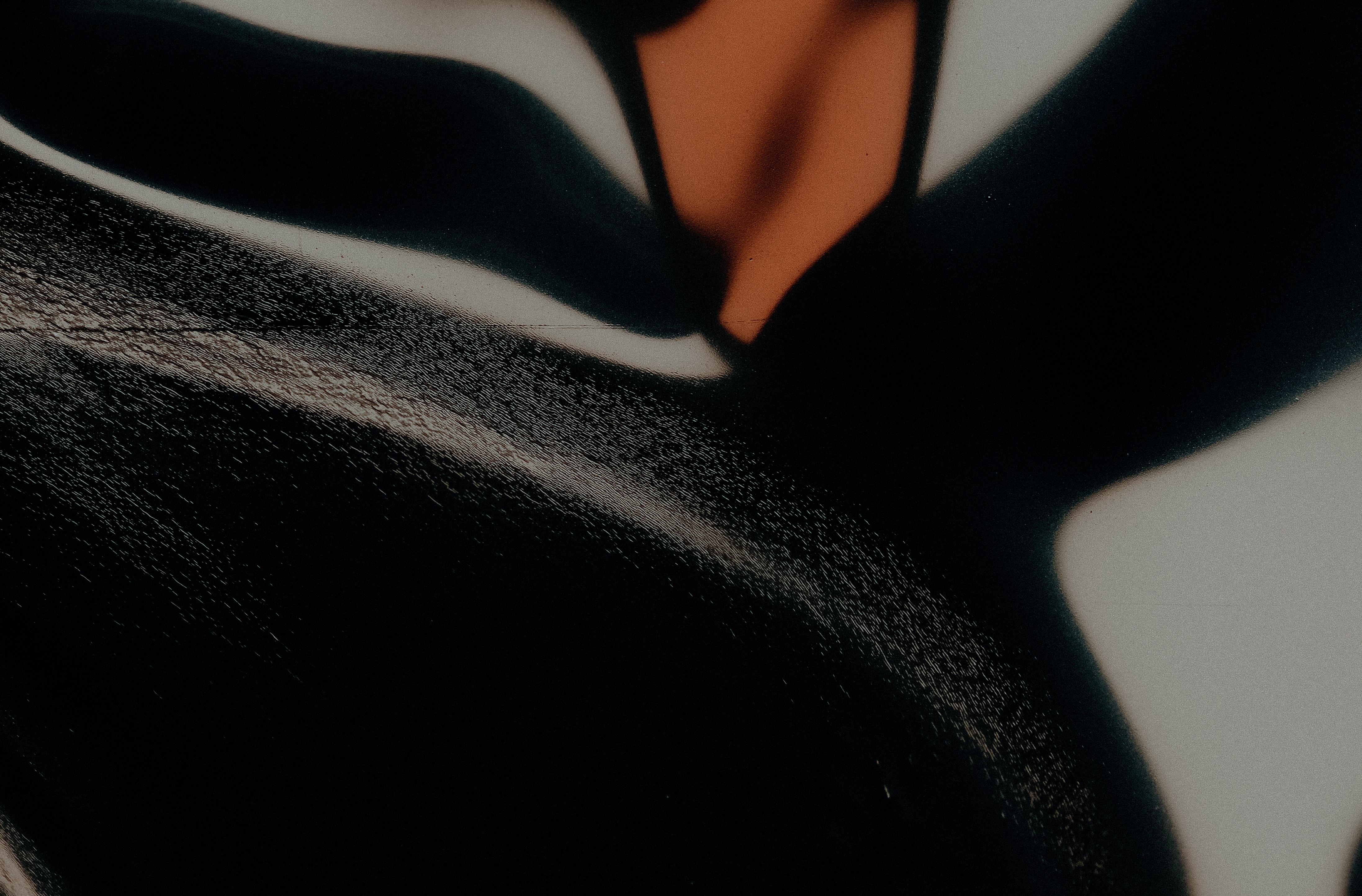

Titling her photographs with haikus − Circles In The Sand , Mirror The Spiralling Feet and In The Clouds Above − Mina Fairchild takes inspiration from a Japanese poetic tradition which emphasises simplicity, intensity and directness of expression. These images of a figure in a landscape, enveloped within a tempestuous fan of silk, achieve this and more. The subject's outline takes on an auratic quality and she almost blends into the landscape around her. This is in many ways consistent with haiku poetry, which predominantly addresses the natural world and our connection to it. In an interesting inversion of this tradition, however, Fairchild presents these images in a distinctly industrial guise: black and white film photography on sheets of aluminium. In this there is an intriguing contrast between form and content.

In Simius , Gala Hills sublimates her childhood remembrances and daydreams into an idealised, imagined world. Ostensibly perturbing aspects of the image − the approach of a bear, a spectral squirrel monkey, or the voyeuristic gaze of a male figure − are offset by Hills' feathered brushstrokes and scumbling, as well as the optimistic palette of light greens, blues and pinks. That is, danger is presented to the audience, but through Hills' style of figuration, in a tongue and cheek way. The composition recalls Diego Velazquez' Las Meninas wherein the Infanta Margarita is dotingly attended to by members of the Spanish court, as she herself breaks the fourth wall, staring out toward the viewer. In Simius , this eye contact with the central figure − perhaps representative of the artist as a young girl − establishes her as the mediator between the real and the unreal, the pictorial logic of this monumental canvas and the world inhabited by its audience.

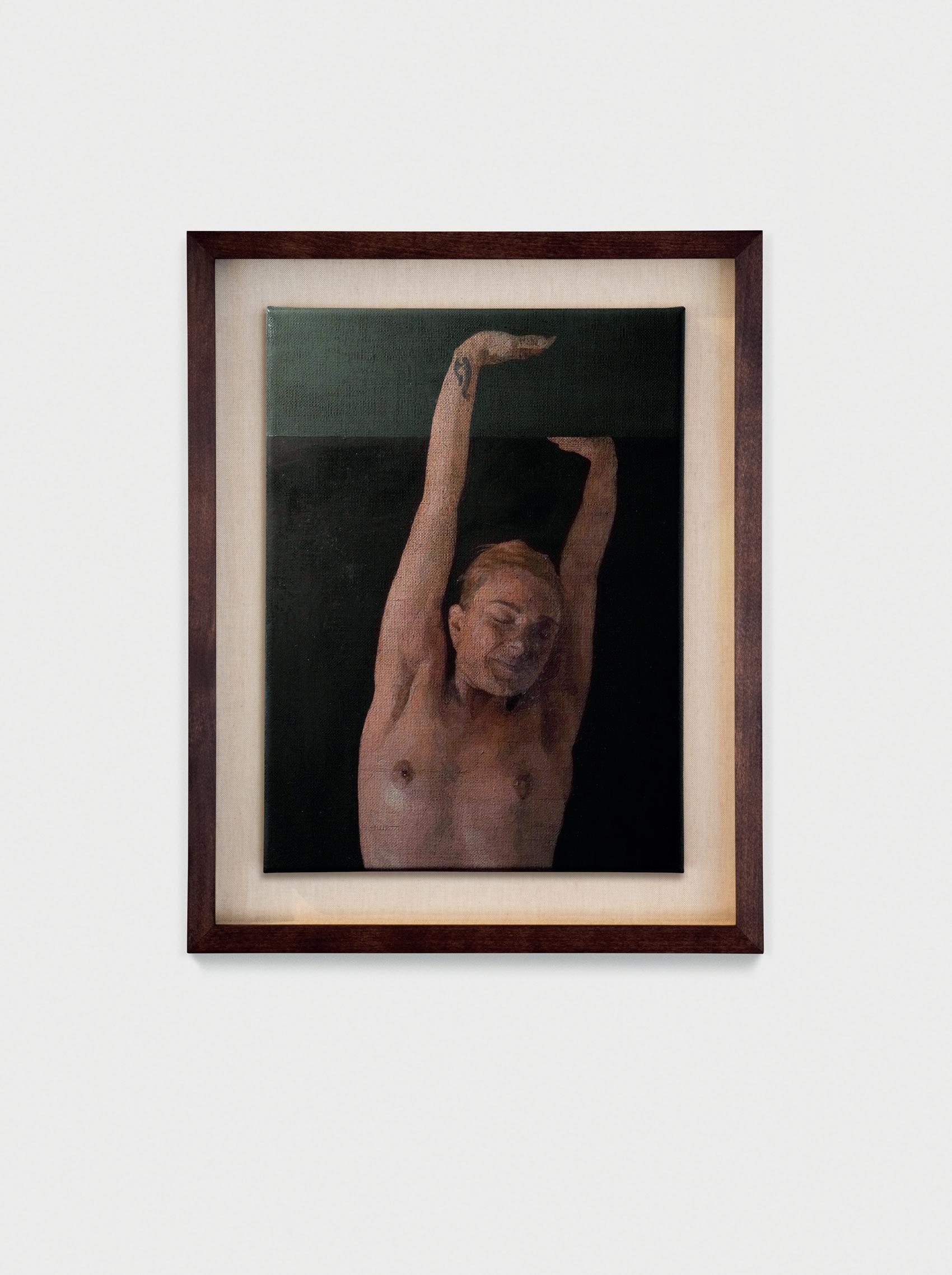

By covering his subject's head in Social Fabric I Julius Killerby makes an abstraction of the face, but one which corresponds with his sitter's facial features. In this way, he balances the anonymity of the subject with a representational depiction of them. This anonymity, moreover, universalises the figure, perhaps prompting the viewer to put themself in the subject's shoes. People pushed to painful extremes feature in much of Killerby's recent work. Explorations of this theme are intended to capture that which he believes to be most distinct about humanity − the capacity to transcend suffering and instinct through abstract thought. Though apparently secular images, these works are thus informed by Christian iconography and depictions of martyrdom. The compositional conventions of these traditions − that of a pyramidal structure, imbued with a sense of ascension − are also utilised in Self Portrait , in which the artist's visage is blurred, capturing him in a moment of heightened sensation. The shadow − conspicuously static in comparison to the animated figure that casts it − serves as a poignant reminder of the dualities inherent in human existence, and the states of being we have the capacity to experience and transcend.

Cayetano Sanz de Santamaria's work, First Fruits For The Son Of Bachué ,

is dominated by the side profile of a colossal Brahman bull, which the artist deifies as the son of Bachué, a Goddess in Muisca mythology. Originating from the Altiplano Cundiboyacense, a high altitude plain in modern day Colombia, the story of Bachué's son describes a virile being which, prior to procreating, was nourished with the first fruits of the season. Through Sanz de Santamaria's lens, the story takes on an especially eerie quality. Upon an Arcadian grassland, three emaciated figures tend to the bull, two of them bearing fruit, the other caressing his side in a gesture that seems to both glorify and objectify the beast. Through their ritualistic masks, the eyes of these skeletal caretakers appear dumbfounded, a distinct contrast with the dignified and penetrating gaze of the bull, literally Godlike by comparison. As with Gala Hills' work, eye contact with the viewer establishes the bull as the painting's focal point, and the preeminent character in this magical realist imagining.

Creatures of the earth, often on the brink of maturation, are a recurring subject for Huddie Hamper, a painter and printmaker from Chatham, Kent. We find these animals in transitory moments, often alluded to by their surroundings as much as their physical form. In White Deer , Hamper depicts a deer encountered at night in a landscape so flat and vast as to see the earth's curvature in it. Bioluminescence exudes from Hamper's subject, its liminality further underscored by a slight contrapposto stance and the image of a younger deer behind. He thereby emphasises the impermanent nature of the representation before us, and in his luminous and vaporous style, finds an analogue for the inevitable passage through stages of growth, change and, by implication, inevitable decline. Parallels are found with Hills and Santamaria's animalian dreamscapes, where archetypal figures are not presented as stringent icons, but are ambiguous and encourage multiple readings.

Richard Lewer's 14 October 2023 presents a poignant scene, featuring a solitary figure in a central Australian landscape, accompanied by three dogs. Produced in the context of the 'No' vote to Australia's Voice referendum, which the artwork's title explicitly references, Lewer's painting on brass is imbued with melancholy and pathos. The despondent central figure departs from the foreground, her turned back creating separation from the viewer, which thus suggests her alienation from Australia's political body. She instead withdraws into a vibrant landscape, the energy of which is enhanced by the sheen of the underlying brass. That is, Lewer uses this landscape as a metaphor for the figure's connection to the natural world, a symbolic approach to painting that is very much consistent with the spirit of Indigenous contemporary art. Inspired by several journeys made by the artist into East Pilbara and Gunbalunya in East Arnhem Land, alongside members of the Parnngurr community, 14 October 2023 is an archetypal example of Lewer's practice, wherein he frequently combines personal narrative with broader societal implications.

True Fiction ultimately addresses the rich terrain between abstraction and representation, demonstrating the ways in which the exhibiting artists, through their deviations from literal depiction, convey ideas relating to memory, psychology, perception, time and politics, amongst a variety of other themes. In these figurative abstractions, the audience is offered equivalents for the uncertainties and mysteries of life, through which a more immersive and authentic connection to the world around us might be possible.

− Written by Julius Killerby ESSAY BY ANTONIA CRICHTON-BROWN

Konstantinos Argyroglou, Grandpa's Easter Dinner (detail), 2023, ink on paper, 38.5cm x 28cm. Image courtesy of the artist's studio.

THE TEN ARTISTS in True Fiction are, in the words of curator and fellow exhibitor, Julius Killerby, “uni ed by their shared belief in the enduring strength of guration.” In his introduction to the exhibition’s catalogue, Killerby further expands on the artists’ connection to one another, identifying the abstract elements in each of their diverse practices and, more broadly, in every depiction of a gure taken from life.

Artists who represent aspects of reality across eras have toyed with the threshold which guration shares with abstraction, creating images which appear to simultaneously reconcile the two forms and locate the tension between them. e contrasts of linear and painterly qualities, for example, in Velázquez’s Portrait of Innocent X (1650) – the moments of volume and sculpting in the sitter’s face, versus the emulsi cation of his white alb – illustrate the entanglement of guration and abstraction in paintings of gures from life. In the period following World War II, however, guration and abstraction were polarised in Western art theory; the in uential American critic, Clement Greenberg, equated abstraction with modernism, a culture of growing individualism and its liberation from the austerity and constraints of gurative representation. e contemporary revival of guration suggests a cultural shift towards humanism and the body as a site for the e ects and expression of wider social and political issues.

Killerby interprets line, shape, colour, and texture as revelatory tools for the artists of True Fiction used to generate meaning and emotional depth in their work, and to allude to signi cance beyond a plain illustration. Lewisham-born Cai Arfon Bellis, for example, begins his oil paintings depicting the Grime scene’s nightlife with bursts of gestural line work drawn in charcoal on canvas, evoking the frenzied motion and viscous swell of dancing bodies. Bellis says that these preliminary drawings are collages of the observational ones he makes on-site; the set of reference images he works from are often “the scribbly ones,” or those that are indexical and non-objective. Line and the scu ed marks of Bellis’ drawings are the residue of his collisions with other ravers in the crowd – events so transitory as to otherwise have been forgotten. Marks such as these give context to the reality from which they were made and are therefore a physical record of its time, space and relationships. Bellis compresses these indices through paint into groups of caricature revellers, MCs and DJs, transforming something visually abstract into allusions to their origins.

is process of amassing gures from abstract marks is paralleled in the practice of the ceramicist, Tom Norris, and the painter Konstantinos Argyroglou. Norris references the phenomenon pareidolia – the human mind’s proclivity for organising and making patterns from nebulous imagery. His vessel, e Tempest, integrates a nal on-glaze transfer of photographic images in a third ring: a bucolic scene, an owl, the face of a cat, a pheasant and boar. ese representational images are nestled within veils, drips and smears of colour, which could resemble marks made through contact with the skin of the artist’s hands and ngers. e tactility of these gestures points self-re exively towards Norris’ moulding of the vessel by hand and his apprehension of gures from his abstractions. Norris clari es the content of his work through this process of layering raw material, colour and gure. Argyroglou takes a similar approach to painting. His representations of photos from his family albums and bathtime as a child rest on a groundwork of watercolour blots and stains which re ect the uidity of memory. Secondary washes of diluted oil paints summon gures and objects from these backdrops that, while solid to a degree, also seem to slip lazily away.

Shane Berkery and Killerby’s works share common ground in their skilful and illusionistic rendering of the human gure. However, both also demonstrate a criticality towards the misleading nature of realism, Berkery through un nished kitchen utensils and soft edges of the suspended gure face-down in Induced Levitation (2024), and Killerby through the tessellations, colour elds and negative space which frame his gures. Killerby leaves evidence of his brushwork, for example, in the background of his Self Portrait (2024) emphasising the atness of the surface onto which he projects his contorted head. As he is concerned with humanity’s physical and emotional extremes, Killerby also shows an awareness of the limitations to what a painted image can recreate from reality. e absence of identifying features in both Killerby and Berkery’s depictions of the human gure are also echoed in Richard Lewer’s back view of Kartujarra woman and contemporary artist, Bugai Whyoulter, and in Mina Fairchild’s photographic series of a gure masked by a silk fan. is anonymity renders the subject

universal, allowing the viewer to nd themselves in these artists’ images.

Animal allegories which allude to myth, dreams, fantasies, and identity connect the work of Gala Hills, Cayetano Sanz de Santamaría and Huddie Hamper. Hills suggests that, for her, painting is in part a space in which she can begin to question female genderism and femininity. She particularly empathises with the bear because of its behavioural complexities, and its degradation and maltreatment by the early church. It is a motif which has assumed an integral place in the composition of her practice. In Simius (2024), Hills unfurls an elaborate series of re ections between portraits of herself and animals, which suggest a correlation between the cultural connotations of these creatures and her biography. e intercessory gure of the girl at the centre of Hills’ work develops this sense of mirroring between the artist and the imaginary vaults of this painting. Sanz de Santamaria’s masked gures likewise operate as bridge-builders for the viewer’s entry into his personal mythologies. Hamper, conversely, has an initial resistance to autobiographical readings of his work, yet so ingrained is the horse archetype and its cultural signi cations – including the primal self and unbridled power – in the collective unconscious that one can speculate on some re ection of the artist in his subjects.

e formal, psychological, political and allegorical abstractions in the works brought together in True Fiction convey a desire among the exhibiting artists to make images which express some essence of contemporary life. A proverb of the twentieth-century German artist, Max Beckmann, reinforces the reciprocal relationship of guration with abstraction in reaching for this essence: “ e important thing [in art] is rst of all to have a real love for the visible world that lies outside ourselves as well as to know the deep secret of what goes on within ourselves. For the visible world in combination with our inner selves provides the realm where we may seek in nitely for the individuality of our own souls.” Artists like Hamper may lament over times in which a visual vocabulary was commonly shared, yet the language of gure that runs through all these artists’ work is one over which the audience may ultimately connect.

− Written by Antonia Crichton-Brown

FOOTNOTES

Julius Killerby, in conversation with the author, 15 November 2024.

Julius Killerby, True Fiction introductory text, October 2024.

Clement Greenberg, “ e New Sculpture”, Art and Culture: Critical Essays (Boston: Beacon Press, 1961), 139-145.

Cai Arfon Bellis, in conversation with the author, 1 November 2024.

Tom Norris, in conversation with the author, 1 November 2024.

Konstantinos Argyroglou, in conversation with the author, 1 November 2024.

Gala Hills, in conversation with the author, 31 October 2024.

Max Beckmann, “Letters To A Woman Painter”, 1948 (lecture delivered at Stephens College, Columbia, Missouri, January 1948), trans. Mathilde Q. Beckmann and Perry Rathbone, College Art Journal 9, no. 1 (Autumn 1949): 40.

Huddie Hamper, in conversation with the author, 15 November 2024.

ARTISTS IN CONVERSATION

IN THE WEEKS PRECEDING TRUE FICTION, ANTONIA CRICHTON-BROWN SAT DOWN WITH THE EXHIBITING ARTISTS TO DISCUSS THE UPCOMING SHOW. THE CONVERSATIONS WERE AN OPPORTUNITY FOR THE ARTISTS TO DISCUSS THEIR WORK, ITS CONTEXT, AND THE THOUGHTS & PROCESSES SURROUNDING IT.

WHAT FOLLOWS IS A TRANSCRIPT OF THEIR CONVERSATIONS.

ANTONIA CRICHTON-BROWN Why do you use watercolours and oils, and what about these mediums make them appropriate for representing the subjects you choose to depict?

KA I use watercolours, rst of all, because they have the capacity to dry fast and to create stains and marks, which for me is very important because it’s as if the memory has been made solid. It creates a stamp. e materiality of this memory is then later washed with oils on top, which are very diluted with a lot of white spirit. is makes the materiality of the memory solid and sti , and the stamp in watercolour, which dries very quickly, creates these dreamy and quite vivid effects. is idea of stamp making, and the solid materiality of the memory that is then washed, came from a painting which I made in 2022, called Water Pockets. I create these stamps – these drawings with watercolour – on the oor. When I do the initial drawing for a painting I always work on the oor. It was very watery and when the work dried, it created this quite watery painting. So this technique came from that piece – the Water Pockets painting – in which I made three portraits on one canvas. Later on, I washed it with lots of layers of oil paint and it created a very dreamy scene.

ACB In relation to your previous work, I’ve noticed you used to paint images of carcasses and heads stitched together but that you have since departed from these subjects. Why?

KA During my BA, I was experimenting a lot and I used medical textbooks and photographs of people who had been in surgery with facial and bodily dis gurements. is idea came from my interest in people who look di erent: people who have been in accidents, victims of war, people who have been sick, and they required a speci c surgery called skin aps, which I then studied and which informed these paintings. Back then, I was also very interested in World War II soldiers, which most of them – after the war – had their face totally dis gured and were using facial prosthetics. I also cast some prosthetics in a project back then. en, when I got into the RCA and I was writing my dissertation, I was thinking about why I was interested in those people.

I thought that this perhaps suggested that I may have a di erence as well. And my di erence in this case was my memories and my dyslexia, and how being a dyslexic learner a ected my childhood. My childhood is the stepping stone in my practice. Most of my works are of children and are mostly self-portraits. Dyslexia shaped my childhood years very much, but I also wanted to concentrate on the happiest memories that I have, which are from before I was six years old. After that, I got into school and it was a nightmare for me, especially for a dyslexic boy in Greece in a very competitive school, with a mother who is divorced. When you are a child, you don’t remember everything. You remember certain events and these events tend to leave a stamp in your mind and in your soul. But then these memories, because they are of events from many years ago, they are also washed away. So, the paintings are exactly the way that I perceive my memories.

ACB Can you describe some of your childhood memories?

KA What I do remember about my childhood is the time that I had to myself. One of the places that I spent time alone was in the bath in the evenings.

It’s one of the places that I depict very often in my paintings. Another thing that might be worth mentioning here is that, in my paintings, very often I depict an object or a place. It could be a ball, it could be a balcony, it could be a chair. ere is a gure and an object. is idea came from Winnicott’s theory of transitional objects. Transitional objects are objects that children form attachments to when they are separated from their mothers’ breast. I see the objects in my paintings as very close to me. For example, a metal chair that was found in my dad’s home. Another painting, Aeroplane Memory, Beyond Myself, has an aeroplane with my grandparents. All these objects are signi cant to me in some way and they could also signify a speci c object that my family is emotionally attached to. e objects are not painted with watercolour; they’re painted with oil. For instance, in Aeroplane Memory, Beyond Myself the object there could be the aeroplane, or it could be the windows, or even the glasses of my grandmother. e place is the most important part for me. I began this painting when I started dating my current partner and at that time I was exploring my grandparents’ past in ways I hadn’t before. at is, their love from the beginning. I was very in love and I wanted to explore these memories of my grandparents. So, I went on a trip to Athens to inform my work and I found a picture of both of them on the plane. I found this magical because it was around the same time that I did my rst trip with my partner, and we went on the plane together and were sitting next to each other. Immediately when I saw the picture I said, “Oh, that could have been me.” I loved it. It was very touching.

ACB What do you think the relevance of your family portraits are to viewers beyond yourself?

KA I took the exploration of memory beyond myself into the memories of my family and how their family, their childhood, their years, their life in uenced my childhood. Very often, the way that parents grow up informs the way that they bring up their kids. In the new series of works I have done, I have been looking at my family’s past and my family’s photographs and my partner’s photographs. It goes beyond myself because I was looking at how their past and their memories inform mine. I consider how other people’s thoughts, experiences and memories may relate to me. Even in some of my partner’s memories, I see a re ection, which I depict in my paintings. Another vital thing in my practice is the act of storytelling. Every time that I go back to my family home, my Mum has a story from the past to tell me. You are informing your future and your current state with the past. I always look back. I like to look back. If you don’t look back, you don’t – in a way – acknowledge the journey. And the journey is the most important part.

happening in Lewisham. It also bled into a lot of Grime and Garage that came out of the borough. So, I simply use ‘Soundsystem culture’ for two reasons: one, to honour and respect the origins of where it came from, which was Jamaican Toasting sounds culture; and because of its links to Lewisham, which is heavily Caribbean populated. I also use ‘Soundsystem culture’ as a term because it’s a very particular style of community music. Sound systems essentially came from people throwing house parties because they couldn’t get into the clubs. ey didn’t feel represented and so they started building their own sound rigs and their own speaker systems so that they could throw their own parties and play their own music. And the music I’m attracted to all comes from that community spirit of “we’re going to make-do-and-mend.” Grime – the genre that I initially grew up with and started making work about – that came from them (young people) looking at their older brothers and older sisters going to these Garage raves dressed up to the nines. And they were fourteen and fteen at the time and would want to get into these spaces but couldn’t, so they had to make their own spaces. at’s when you see the rise of stu like Pirate Radio. e more time I spend in those communities, the more I value that attitude of “We’re going to nd a space for us, for our music, and we’re going to come together to do it.”

ACB It seems to me that your work then assists in telling the story of a community that is underrepresented in mainstream art worlds. Would you agree?

CAB at's the thing that keeps me going. We all take for granted how wonderful it is to have those places you can go to, to let go and be a part of something bigger than yourself. In Jeremy Deller’s Everybody In e Place (2018), he makes this really interesting comparison between chapel and the religious experience of sound, which can be really heavily echoed in a lot of the underground early community sounds, like the techno scene coming out of Detroit. It’s not a coincidence that a lot of Grime MCs coming out of Britain come from gospel church backgrounds. And I think clubbing and raving have now been through decades worth of besmirchment. I used to get feedback that my work was very aggressive, very boisterous and quite angry. At New Contemporaries (at Camden Art Centre) this year, for example, I was compared a lot to the War painters like David Bomberg. It was a strange experience for me because my work is about this beautiful comradery, if anything. roughout my time, I’ve realised that perception came from people who had never experienced spaces like those I depict, or that form of joy. And so now I see it as almost like a barman’s handshake; it’s for the people who know. ey understand, they recognise, and it reaches them in a di erent way to how it reaches other people.

and the paintings I make become almost like a curated night’s line-up. I’ll set up my sketchbooks as the reference points and then I will collage the rhythms and the movement of my drawings together, almost like referencing the experience of strobe lighting, where you get these ickers of images popping.

SHANE BERKERY

ACB Who or what do you look to for inspiration?

SB I have been looking at a lot of work by the Old Masters. Something that I have taken from seeing a lot of those works was the detail in the darkness and how the darkness is an actual feature. ere are lots of blacks and browns and nuances within the darkness. It captures a sense of space while not being space at all and you have the gure oating in the foreground. ere’s something about that which I wanted to bring into my own work. I am also drawing from things that happen within my own mental space, like memory, dreams, and the things that I consume, like painting. My most recent painting was taken from Caravaggio's Supper at Emmaus at the National Gallery. It was imperative that I had the ability to do the rendering. I always thought that it was important to be able to do that rst – having the skill, and the freedom of whether to use it or not – rather than being dictated by what you can or can’t do. I went to the Philip Guston retrospective at the Tate three or four times. ere’s something very freeing about his work. You can see the energy that it takes to make his paintings. You can see the painting becoming.

"WE ALL TAKE FOR GRANTED HOW WONDERFUL IT IS TO HAVE THOSE PLACES YOU CAN GO TO, TO LET GO AND BE A PART OF SOMETHING BIGGER THAN YOURSELF."

-

ACB What mainly interests you in terms of subject matter?

CAI ARFON BELLIS

ACB What does ‘community’ mean to you and what do you hope to celebrate about ‘Soundsystem culture’ in your work?

CA ‘Soundsystem culture’ is a very broad term. I use it because it’s very descriptive of UK electronic music and its origins. A big draw for me, for making my work, is my upbringing and where I come from – growing up in Lewisham. I was very lucky to come from a very rich musical heritage. Saxon sound system –that was a very pivotal dub sound system in New Cross which bled into what was

ACB Who or what, would you say, has most impacted your work?

CAB My move towards drawing was really important. I was a photographer for a long time and, when I started painting, I was painting from my photographs. A really quite pivotal moment was when a tutor at the Slade asked me, “What are you doing that the photographs aren’t?” at’s when I started my sketchbook process of going into the spaces and doing observational drawings on site, because you then get these lovely messy bits, the hints and suggestions of someone walking through the crowd. I think my work became a lot more about the experience of a place rather than what it looked like. I’ve always loved Basquiat, and I was introduced by a tutor to the term ‘indexical marks’, which is the context of the space or the index that references the space. I think a lot of people, when I say I do the drawings on site, they think I’m at the back or I have an elevated space or I’m by the DJ, but I’m really in the crowd, in the middle, getting pushed and jostled about. When I’m in the studio, the drawings that I work from are the scribbly ones that I can’t quite make out because these capture the essence of a particular night and the rhythm of the crowd. e larger scale works

SB I’ve been trying to capture this idea of where a painting lives in your mind and how it exists there. When you experience a painting and when you move away from it, it’s not like you see it as an object that oats in your head. You have the space you saw the painting in and that interacts with your experience, with your memory, with the environment inside your mind. So, I am looking at how you experience memory or, more speci cally, how you experience internal imagery. I am slowing down and trying to look at how things appear in the mind: it’s the nebulousness of a eeting image, like an overlay of what you see. I am trying to capture the sensation of an image appearing in your mind. My mind sometimes races and these images are eeting and vague. Sometimes you get these incredibly vivid moments, like when you’re falling asleep. By trying to capture that, I’m trying to hopefully – in the viewer – evoke that sensation. In the painting process, I use photography to reconstruct and emulate. e piece in the show, Induced Levitation, originated from a very vivid dream that I had. It was a nightmare that ended in sleep paralysis. rough photography and Photoshop, I recreated it and then drew from that image. I paint from the drawn image, and I refer back to the photography and the drawing. I am trying to reconstruct that feeling but also an awareness of its construction. Photography does that. A lot of memories I have are based on photos and they are almost like false memories because there’s no way you would remember it. Photography, in this way, seems to me to be a type of construction.

ACB What do you think is the relationship between memory and photographs?

SB ey’re completely intertwined now, especially because we all have cameras in our phones and everything is recorded. You can’t really tell what’s in your brain, what’s from the event or the images of it. I think that’s an interesting thing to ponder on.

CAI ARFON BELLIS

ACB Can you tell me why you started painting from photographs your grandfather took in Japan in the 1950s and 60s?

SB My grandad lived in Japan and worked in Mitsubishi. He took a bunch of these photos of his colleagues and family and all of them are in black and white. A lot of the pictures were candid photos, not posed and just snapshots of the time. Seeing these photos, I guess I felt this false sense of nostalgia. I felt like I was there. I look quite like my grandad so I could see myself in these photos. It was this transportation that interested me rst. rough the imagination, you have a separate experience from what is depicted or what is captured in the photo, to then what is captured in the painting. So, it’s almost not about what is there. My work is about the function of the various images that we interact with. It’s about how an image enters your mind and how that stays there and what form it takes when it’s in your mind.

ACB What do you get out of painting?

SB When I see artists present the same kind of work time after time in their exhibitions – when it’s all very homogenous – personally, I very much react against that. I always consider each painting not as the nal piece but a step towards what I want to get at. I start the painting a di erent way each time. It’s not like I have a xed process. It’s very much about trying to nd something new. It doesn’t have to be a big step every time. e most ful lling part of painting for me is after nishing a piece and then working on your next one and looking back at the painting that you just nished. It’s this object that you feel slightly detached from. It feels separate from yourself, like an autonomous object that has all this history. at satisfaction of something having been created is what I love about painting. More and more, the process is what’s im-

portant to me. I’m approaching it more as a meditative practice: to look at these memories and images in my mind and being conscious about trying to interrogate that image and interrogate how it works.

MINA FAIRCHILD

ACB I am interested in why you chose to print on aluminium sheets for your works in True Fiction What is your process like in general, and what is the conceptual rationale for it?

MF My photographic practice is documentary, opening portals to moments in my experience of life. I never set up my photos, only sense them in the moment and capture them on lm. With lm photography, I relinquish a lot of control over what is happening, preferring to experiment with the image afterwards, in the darkroom or digitally. As I explored the images (Circles In e Sand, Mirror e Spiralling Feet and In e Clouds Above) in Photoshop, I found this interesting light on the horizons and pushed the grain until the details were revealed. My art practice is an investigation into the essence of the materials I work with. As to why I printed these works on aluminium sheets, I was inspired by my mum's recent exploration of printing photographic work on brushed aluminium. Photographic work can be fragile in its materiality, and so the metal reinforces these images to withstand time; through which emerges a deep contrast which reminds me of how I feel living in large brutal cities: soft inside but with a hardened outer body.

ACB You are also presenting a bronze sculpture in this exhibition. How does that piece tie into your practice? Is there a relationship between the photography and your sculptural practice?

MF For True Fiction I will be exhibiting a recycled bronze sculpture of a deer's antlers. Having worked with metal for around three years now, I specialised this year in learning bronze and aluminium casting. One morning, I was researching how to cast bone into bronze and I left my house in Peckham and just happened to nd a deer skull on the side of the road, in a box with a note, which read “My name is Cecil. I am looking for a new home.” So, I took it to my university workshops and presented the project idea to my technicians. None of us had ever worked with bone so it was a new and exciting project for everyone involved. I had to take the skull and its antlers through two di erent processes in order to cast them in the limited facilities that we had. Working with organic material is such a di erent experience as you are aware that there was once a life encased within what you are holding. As I separated the antlers from the skull with an angle grinder, clouds of bone whirled around me. I was immersed in the life of this animal who had, in some sense, become a sacri ce to my art. e process was very heavy but I held myself in gratitude and wonder. I just had to trust that I would be able to create what I envisioned so that the sacri ce was worthy. Although the skull is not present in this show it is important to acknowledge that the process for casting it was very di erent. With the antlers I created wax copies using silicon moulds, which were then taken through the lost wax casting process. With the skull however, we actually red the bone within the ceramic shelling. We then poured the molten bronze into the shell. e material of the inside of the ceramic shell transformed from bone to dust to metal. To me this felt like alchemy.

ACB I love that idea of the sacri cial element because it suggests that you are deeply in tune with the objects and materials that you are working with. You are thinking not only of the current state

Opposite: Gala Hills, Simius 2024, oil on calico canvas, 137cm x 254cm. Image courtesy of the artist's studio.

Mina Fairchild, 2024.

Image courtesy of the artist's studio.

of the deer, but also its past life and how it will exist in the future, and honouring that.

MF Yes, the project was de nitely an honouring of the deer. I gave many thanks and, as she had found me, I knew I was held in safety for transforming the animal.

ACB We've touched on it brie y, but I get this sense that your practice is very much about contrasts between hardness and softness. Your photographs (Circles In e Sand, Mirror e Spiralling Feet and In e Clouds Above), for instance, are titled with haikus, a Japanese poetic tradition that has a lot to do with the natural world, but as we've discussed, these works are printed on a surface (aluminium) with quite industrial connotations. What interests you about this juxtaposition?

MF I would say that poetry is probably the most grounding part of my practice because it's a way that I can express my feelings very directly. e photographs in True Fiction were taken during a retreat in Norfolk where we entered a deep meditative state, hosting medicine ceremonies and connecting to the stars and the sea. One night we danced on the sand and drew with our feet and hands, our torches igniting the patterns in the dark. e following morning the clouds mirrored the patterns we had made and circles were forming in the sky. We felt such a deep connection to the universe and so the haiku, “Circles in the sand, mirror the spiralling feet, in the clouds above”, re ects this. is year, I also experimented with engraving seven of my poems into metal sculptures. My poem, “da city makes me hard” was fragmented into three separate sculptures. It was an interesting process engraving the words into a material which, again, is going to withstand time. It's really emphasising the sentiment of those words. I'm showing how deeply I'm feeling these emotions that I'm literally carving them into the surface of metal. In the same way that the photos printed on aluminium will stand the test of time, so too will the poems.

HUDDIE HAMPER

ACB What to you makes for a good image? Can you reference a particular example and describe what you see in it that makes it so e ective?

HH e rst image that comes to mind is e Massacre at Chios by Delacroix, which I saw for the rst time in the Louvre’s major retrospective of his work in 2018. It was one of the rst large scale paintings that really blew me away. It felt so dynamic, probably in a similar way to e Raft of the Medusa where you have all these bodies going o in di erent directions and leading lines. I like compositional aspects that I nd dramatic. I remember in Delacroix’s diary he says, “ e rst merit of a painting is to be a feast for the eye.” When you look at e Massacre at Chios you can understand why someone who thought that would paint something like this; there’s so much going on, there are so many elements, there’s so many di erent relationships between people in the painting. Your eyes wander around it for ages trying to work out what’s going on.

ACB Do you think there’s a strong correlation then between images that work both compositionally and formally, and images that have emotional e ects?

HH Yes, because they (the formal aspects) are the container for what you’re trying to say. It’s like what van Gogh said about getting good at drawing: “It is working through an invisible iron wall that seems to stand between what one feels and what one can do.” at’s taken from his letters. e formal qualities of painting are the container for what you are trying to express because they are the language, they are the words. Line, form, colour – those are the things that you can really grapple with in painting, those are the tools you have to try and convey or reveal something. In talking about it, I realise that I’ve used the term ‘dynamic’ and I’m trying to work out what I actually mean by that. I guess ‘dynamic’ is to do with motion.

ACB You seem like such a traditionalist and so many of your references are classical ones. What does ‘tradition’ mean to you, and how does it bear on your work?

HH It goes back to those formal aspects in painting that we were talking about. ere were points in time – in history – where there was a greater emphasis placed on formal elements of painting. ey were taught. It gave a structure

to things. I think painting is fundamentally about the image and with a lot of the work I see now, I don’t really like the image. I don’t really connect with it on an aesthetic level. I think probably as a society, we’ve moved away from aesthetic sensibilities. Just look at the kind of buildings that are being built now. You look at the world that people are making and it’s not – to me – one that I think is very aesthetic. And I do think, to a certain degree, that contemporary art re ects that.

ACB A word that I think of when I look at your paintings of horses and boys on horseback is ‘nostalgia’. It feels like you are harking back to a past that is no longer accessible, or perhaps so far away from your intimate context where you are now – in the city, in London.

HH I do also paint portraits of people I know.

ACB Yes, but you paint from photographs. What is more nostalgic than looking at a photograph?

HH A lot of those photos have been taken speci cally as reference images for painting. I understand what you’re getting at, but the reason for what I paint is more about me not being interested in depicting the here and now, for instance, a building in London or a speci c place. It’s nice, I think, when things can feel a little more expansive than that. As soon as you put an iPhone in a painting, or as soon as you are reading a book and it has a very speci c contemporary cultural reference, I nd it limiting. It takes you out of it. For me, I want the story to seem like something that could be more than what is on the surface. I don’t want the context to be absolute. It needs to still be quite abstract for me. I’m pushing for a broader interpretation in my work. With the gures on horseback moving through landscapes and water, at the time – when I’m looking at those images and references – I don’t have a rm conceptual idea. It’s a lot more subtle than that. In retrospect, in going back, in looking at work I’ve done, I can try and unpick or understand why I’ve chosen those images, why I’m interested in them and what is going on psychologically for me. But at the time, you could say it’s intuitive. It’s a process of working through stu . I like avours that are subtle. Noticeable, but subtle.

ACB What, to you, is the value of gurative painting?

HH I think communication is important. What painting, or art, or writing, or music, or dance, or any of those things can do is to connect people in a way that you can’t really do through talking. Painting is a form of communication that is nonverbal. So I suppose that would be part of its utility. I think aesthetics are important. Beauty is a re ection of harmony and balance and that's how everyone wants to feel internally. It can be very moving and I think painting can make you feel that way.

GALA HILLS

ACB Whose work in uences you – either visual, musical, literary, or otherwise – and why?

GH My in uences have changed since the past summer. Lately, they’ve been a lot more literary. I’ve been looking a lot at Tove Jansson, who is known for the Moomins but I’ve been reading Notes from an Island (Jansson) and she had this idea of a self-made world that she seems to believe in but also sort of doesn’t. She is sceptical of her own fairy tale, but she also has this very pragmatic approach to it, and I’ve been really inspired by that. Also, Alfred Wallis – the artist and sherman from St. Ives – has been a recent in uence. I’m from Devon in the West Country and I have been thinking about what art from there looks like. His work comes from quite a functional, practical lifestyle, being a sherman…

ACB It then seems like there are two quite opposing forces at play for you in your work, as if you’re juggling the imaginary with the pragmatic, the tangible with the intangible. Would you agree?

GH Yes, de nitely. I don’t think that the imaginative aspects would really work if there wasn’t a reason for them. Using the imagination as a method to access something… to access memories or emotions that I would not be able to access otherwise… that is what’s pragmatic about it. I was diagnosed as autistic quite late in my life and one of the questions prior to the diagnosis was “Did you prefer ction or non ction as a child?” and I wouldn’t say that was really

Huddie Hamper in his studio, 2022. Image courtesy of Nick Clement.

the right question to ask because I think I made the non ction into ction and vice versa. e way I work is that I do a lot of reading and a lot of research, but it is also imaginative and playful at the same time… at’s part of Tove Jansson’s work. She did children’s books, but they are grounded in her real life as well. It’s a merging of something fantastical with something real.

ACB Although your practice spans a variety of mediums, you are very consistent with the imagery you use. It’s as if you are world-building and dressing stages for your characters. Would you agree?

GH I like your insight that some of my paintings look like theatre sets. I feel limited when what I am making is just a painting or just a design. I like things to have multiple functions because it allows me to jump to the next thing, and then the next. Recently I made a bear mask that you can wear. It’s made out of fake fur and other stu . In itself it’s an object and has a performative element, but it also allowed me to ‘see’ *laughs* through the bear’s eyes, if that makes any sense. It sounds a bit pretentious, but I think it allowed me to access parts of the work (Simius) that I couldn’t have without it. I look at this process as steps towards the next work. Functionally, it helped me learn how to draw a bear from any angle. It was a really good exercise.

ACB What does the bear symbolise for you?

GH rough doing more research into bears I learned that they are very unconventional animals. ey are very sophisticated, and they will do completely contrary things. e main thing I can think of is that half of the year they are herbivores and then for the rest of the year they are carnivorous, based on food scarcity. ese animals have such complex social behaviours that they can be both things. e drawings I made were like being inside a bear, of being eaten but also of a creature that is almost nurturing and has maternal feelings. ere’s fear but there’s also comfort, together in one. ere’s this great book called e Bear: History of a Fallen King (Michel Pastoureau). It details the history of bears in Western Europe. It talks about how medieval scholars had three animals who they deemed to be sinful. e word ‘simius’ means ‘similar’, and ‘simian’ means ‘monkey’, or ‘ape’. Imitation is a sin in Christianity, so these animals – bears, monkeys and pigs – were all deemed too similar to humans… and so there was supposedly something wrong about them. ey were too human… which means that they are bad *laughs*.

ACB You seem to draw a lot on folk and vernacular forms. Can you elaborate on where these come from and what inspires you about them?

GH I did a lot of research into print making and pattern making in the Weimar Republic, and a handmade aesthetic achieved through manufacturing processes… and obviously William Morris and the Arts and Crafts movement. I was fascinated by them and the power of making patterns. Connecting it with my own life, there was an old woman that I used to visit in the town that I grew up in who taught me how to embroider, and this practice feels like it’s something that is at risk of being lost. I know a lot of people here on my course (at the Slade School of Fine Art) who really enjoy learning how to weld, or how to forge, or how to actually make things. It feels like a really wonderful revival. When you learn how to do those things, it feels like you can change the world around you – your immediate environment – through these craft processes.

JULIUS KILLERBY

ACB In previous years, you have made suites of work that focus on particular themes, such as isolation and seclusion through the visual metaphor of the island. What would you say is your current thematic focus? How do you consistently represent this theme in your work? What has in uenced this theme becoming the axis for your work? Why do you think this theme has a wider relevance besides its resonance in your own life?

JK I would say that I always try to explore the psychology of my subject, either through the deviations I make from super cial representations of them, or through the implications of their surroundings, as was the case with the paintings I made of gures on an island. My current theme, broadly speaking, is the power of abstract thought over our more base instincts, and gures in moments of pain is predominantly what I’ve used to try and express this idea. My interest in this came from a conversation I had with a social psychologist, Sheldon Solo-

mon, in which we were discussing Ernest Becker’s idea that fear of death is what motivates almost all our actions, on a subconscious and conscious level. ough the themes I explore in my paintings do not focus speci cally on this, it denitely prompted my appreciation for the power of the human psyche. I’ve also come to think that this is possibly the most distinguishing aspect of humans and what perhaps even distinguishes us from the rest of the matter in the universe, all of which seems to obey predictable patterns and laws. Humans seem uniquely capable of reacting variably to the situations that befall us.

ACB Many of your paintings are examples of close portraiture, of notable gures and those you have encountered and formed relationships with over your life. Yet often, while you use these gures to work from, your portraits seem to be more de-familiarised than intimate portrayals. Would you agree? Why do you choose to depict people with whom you are familiar, and why do you then make portraits that are somewhat de-individualised?

JK I would say that a part of my practice includes portraits of people in which I am speci cally trying to capture their character. But for my more thematic work, I do make a point of depersonalising and de-familiarising the gure so that they have some kind of relevance to the viewer, beyond simply being an accurate portrayal of the subject's features. I think that much of the best art comes from the reconciling of a very personal narrative with a universal sentiment. I made a series of paintings in 2018, for example, which were of people who I knew very well. I would not paint their pupils, however, because I was trying to convey the idea that technology, and the modern world in general, was having a depersonalising e ect on us as a species. I thought that if the eyes are the window to the soul, then their absence could perhaps be used to signify a soulless age. e omission of the eyes was also a vague reference, I guess, to Ancient Greek and Roman sculptures, which have had a big in uence on my practice. By making this reference, I was trying to freeze the gures in time, or capture the idea that they, because of the world around them, had become inanimate shells, rather than living and breathing people.

ACB Why have you chosen to bring together the ten artists for this show? Can you elaborate on what you see in their work that connects them?

JK I think that all the artists in this show are in some sense uni ed by their belief in the enduring strength of guration. I feel that a lot of art, speci cally in the last one hundred years, has been art about art, and sometimes only seems interesting within its own context, or by the comparisons one can make between it and the art movement that preceded it. Much of it almost seems like art made for an art history book, rather than art about, and for, people. is isn’t to say that paintings without a gure do not say something about the human condition. A landscape, for example, reveals something about humanity because it is a view of the world as it appears from a particular vantage point, and from the perspective of a particular individual. It’s also not to say that art about art doesn’t say at least something about humanity, but I think that what really unites the artists in this show is a sincere approach to uncovering something deeper about humanity. is is also, I think, an inexhaustible subject. Its artistic manifestations are as unique and varied as people are.

ACB What to you is the main function of a painter? What is their role societally?

JK I haven’t really given this too much thought. I guess to try and gure out the societal purpose of a painter, one could look to the e ect that paintings have on society. Many people would say that our natural evolution seems angled toward AI and our gradual assimilation with various technologies. is certainly seems to be true, at least in part, but what I see as a more interesting aspect of our evolution is our gradual accumulation of varied points of view, which is certainly something that art contributes to. I think that society is always susceptible to committing more and more heinous crimes. History shows that if someone can think it then they will do it. But I also think that today we are armed with more perspectives than people had thousands of years ago. For all their artistic and philosophical achievements, people in Ancient Greece, for example, did not have the bene t of paintings by Francis Bacon, van Gogh, they did not have Enlightenment ideas, nor did they have movies like Schindler’s List or Mr Jones, which I think lend 21st century audiences a greater appreciation for the horrors we are all capable of, and a more wholistic understanding of humanity. So I think art has the potential to further the evolution of our self-awareness, as individuals and as a species.

ACB Can you talk me through your process in working through a painting?

JK I will usually work from a photograph, but I will also do a sitting with the subject if I have the opportunity to. Sometimes I use a grid to scale up my drawings, but other times I don’t, as the grid can occasionally give the image a rigid feeling. I also believe that the painting should say something more than the photo, or else what’s the point, so the mistakes inherent in drawing without a grid, such as skewed proportions, can sometimes be a positive. I then paint the picture in oils, sometimes using glazes.

RICHARD LEWER

ACB is will be the rst exhibition of your work in London. Can you describe your experience working in the Australian and New Zealand art worlds and comment on what you perceive their relationship to the global art world to be? How do Australian and New Zealand artistic concerns match or diverge from concerns in places beyond their national borders? How do Australian and New Zealand politics impact both artistic practices internally and, more specically, your own?

RL It's funny because when I recently visited London I went to Frieze and I suppose not having more familiarity with some of the exhibiting artists and galleries meant that there was a bit of context missing, at least for me. Whereas here, in Australia, the art world is a lot more insular and everyone knows each other, more or less. It's so far away and it's so removed from the rest of the world that you start to look more inward. I am very conscious of this insular perspective, in both my work and my life in general, so I think it's vital to step outside of those things. I am originally from New Zealand and have now lived in Australia for about twenty-eight years or so. Coming here (Australia) really was a big jump for me. Exhibiting overseas is now something that I de nitely want to pursue more. I feel as though I've had this time here, been to the outback numerous times, explored a lot of Australia in general. It's only now that I feel I've talked about what's happening here and really now need to look further a eld.

ACB e title of your work in True Fiction references the day which saw over 60% of voters in Australia vote against altering the constitution to add a formal Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander advisory body to Parliament. What were your thoughts on the referendum?

RL I was just gobsmacked. Being from New Zealand, I was of course aware of the KĪngitanga, a Māori movement that arose in the late 19th century to give a voice, albeit in a non-constitutional capacity, to the Indigenous New Zealand population. is is almost exactly what people were asking for in the 'Voice' referendum, and so to think that the country voted ‘No’ just makes you think how far behind we still are. It was outrageous.

ACB In what way do you think your painting, 14 October 2023, responds to this issue?

RL e best times that I have spent in Australia have been in the outback, although they've also been the hardest. Going into the outback allows you to actually meet Indigenous People and hear what their concerns are. With 14 October 2023, I wanted to have a snapshot of a daily occurrence, which would be going to get bush turkey, kangaroos or camel for dinner. Out there, you can't go down to the supermarket to buy dinner. You've got to catch it. These eighty year old ladies, who basically run the community, they'd be at the studio at eight in the morning and then at three o'clock would go hunting for dinner. That was what we did for a month. In certain situations it was mind-blowing the kind of conditions and situations they would have to endure, though they would never complain. The painting was just a snapshot of Bugai Whyoulter − one of the artists − whilst she was walking her dogs, as we were about to go light a fire.

ACB Is that burning done so as to rejuvenate the soil?

RL No, they in fact do it to draw out the camels and kangaroos from hiding, and these res can be absolutely massive, but they have such a sound understanding of the winds and the land. I was really hungry one day, and there was this girl who was writing on her painting, and she couldn't write her name and I was feeling a bit sorry for her. We were out the back and she goes, “If you are hungry we can go and dig up some witchetty grub.” I then thought, if I was out

here alone, I would be dead in hours, and I was stupid enough to feel sorry for someone who was just struggling to write their name. I thought, I bet she feels sorry for me because of how helpless and pathetic I am in that environment. Anyway, eating these witchetty grubs, I was thinking there's no way I am going to be able to eat that, but then I ate it and it actually reminded me of Camembert cheese. It was really nice, you know.

ACB I know it must be hard, but if you could summarize what it is you learned from this experience, what would you say?

RL I think one big thing was learning to slow down. My usual daily life is quite manic. Everything becomes a bit of a rat race, whereas there you slow down because you have to. e heat is a big part of this but you also have to take in your surroundings. ere was one time when I was attacked by wild dogs, and if I'd learned the signs beforehand, I wouldn't have been attacked. It sounds cliché but you do become one with the landscape a lot more. You learn to observe the weather, the wind, the heat. Everything is dictated by your surroundings, rather than you trying to dictate your surroundings.

TOM NORRIS

ACB You are one of two artists exhibiting sculpture in True Fiction. Why do you choose to work in 3D with ceramic stoneware and what does this medium bring to your practice that others, say painting on a plane surface, do not?

TN ere’s something in the tactile and physical aspect of it being threedimensional that really appeals to me. I’m attracted to known forms and things that exist within our lives as objects, that resonate or have a hook on us already. Sculpture feels more ingrained in our lives, rather than something that is abstract, that is separate, two-dimensional, framed or re ned. ere’s something about making in that way that leaves it open-ended for me, as a maker of an object, but also in it being round. It (sculpture) evolves and develops organically, more so than something that’s more constructed as an image, like painting. at sense is hopefully understood by the viewer. ere's also the idea of the image being rebuilt. You nd it by walking around it. ere’s an interplay of the images on the vessel. It opens up all sorts of formal questions as well. You have three dimensions to play with and it does not have to all be there, present on the rst glance. Your interaction with it is an additional aspect of the work. Each aspect of the process I have an actual, tactile hand in, which de nitely plays into how the images are revealed or concealed… it’s being less clever than a painting. It’s being more true to how we experience memory perhaps. It’s less revelatory and more intuitive. It occupies a physical space rather than depicting space.

ACB You have said that this work, e Tempest, is about shelter or hiding. Can you elaborate on this?

TN at can extend as highfalutin as you like. It could be all about the agrarian process or the need to organise. It’s about being human really. ere’s a deep-seated need for protection and introspection as a person and these objects hold a psychological weight within our lives. ey (vessels) point toward or denote security, I suppose. at points toward their functionality: it speaks of home and home speaks of the idea of being secure, in a nest. It’s all held in the same language. e title of the work is e Tempest so there’s themes of unrest and con ict. e imagery calls towards that a little bit, emphasising the need for intimacy and seclusion. It’s a space for comfort and contemplation a little bit as well. I am very interested in the idea of revery. I spoke about that a little with my last exhibition at JGM Gallery, Also Rises, what that mental space – or a home or safe space – can do for a person in the sense of dreaming, or thinking ahead, or a prophetic idea of something else. I’m reaching maybe a little bit too far there… ere’s also the painting by Giorgione that I’m interested in. ere’s a duality to things that you think of when you say the word ‘tempest’. Obviously, there’s Shakespeare and also this rather obtuse painting. e narrative is scraped away and hard to nd, which is unusual for the time (early sixteenth century). I’m interested in that illusional vagueness – the tightening and loosening of ideas in that work… ‘Tempest’ is also a storm… e whole thing is a reference to itself as well. A vessel is a cocoon-like structure that resembles something organic. It has the potential to hold, so I thought e Tempest was a tting name to hold those ideas both physically and poetically. e idea of the vessel also mirrors the idea of fertility and the female form. ere’s an analogy there as well.

ACB And do you go back to imagery of the mother and nurture regularly?

TN I suppose it’s pulling on a thread that’s present in the work most of the time. e nature and the foliage and the forest could be an extension of the same idea… it’s its own habitat and shelter. I’m interested in that kind of feeling. Again, revery – walking through a forest and being held by nature. So that would be something that is in most of the work I make, but also explored a bit more, or pulled on a little tighter in this work. ere’s a con ict or uncertainty, a utopia or dystopian idea within a natural environment. I try to play around with the disappearing of the gure, that loosening and tightening of gurative and abstract forms.

ACB When you say “loosening and tightening” I think of the moments of intensity you nd in painting in terms of application. Can you expand on that concept?

TN Yes, there’s a term, ‘pareidolia’, which is the phenomena when your brain sees something and recognises an image… sees faces in a tree, for example… there’s something similar with the way we look at abstractions, where you lean towards seeing something representational or nding a pattern. ere’s a bit of that as well… seeing an image within something that is innately abstract.

ACB When did you start using the transfer technique that you’ve recently developed?

TN I was working with a painter on a collaboration, and I was surprised at how little the medium can do for you in terms of how it looks when it’s completely nished. e chemicals and pigments that you’re working with are always slightly di erent (working with ceramics), which is not true to a sense in painting. When oil paints dry, they change a little bit but that’s exaggerated when working in ceramic because it goes through a metamorphosis – a physical change – from materials. It changes from clay to the permanence of ceramic. ere’s an irreversible change. I lean towards not being pinned down on the images that I’m making, so that opportunity to add in a collage element gives me another chance to change things a little bit and not let it harden up so soon. e on-glaze technique is a third ring, which is a relatively low ring. All you’re doing is heating up the basilica, the glass. It’s already shiny, and then you can put these photographic images on which is also bringing in something that is quite solid and recognisable. It’s also a way of playing around with the formal elements, like colour and tone. It gives you the opportunity to think meticulously around what images you are referencing and how this can resonate with the theme of the work. You can draw in historical references at this point. ere’s an opportunity to put some more personal photographs in. Something like that can leak out a little bit, something that points it (the work) in its last direction. So, the transfer technique is a further stage of working.

ACB What do mythologies and allegories convey that representations from real life do not?

CSDS Well, it comes from my admiration of storytellers, of us humans being storytellers since the beginning of time and passing our reality on through stories – something that our children are going to remember. Myths and legends stay in our minds but also speak about the truth of what it is to be human. Humans try to decipher human nature – human spirit – through stories. Even though they are just stories, they speak about the realities of being a human, of how to survive in this strange world and gure out our feelings. I guess I use mythologies to capture the absurdity of reality, but also to discern how much meaning we can nd in the absurd. All the creatures and characters in my work seem so full of humour, but once you read the title, you start automatically to put meaning into it. I think that’s life in its everyday continuum: nding meaning in these random things that are happening. You map the world around you with stories. I feel art is my tool to explore whatever is deep in my mind and in my soul, and that ends up being connected to ancestral beings – humans that lived before us. at’s why I love mythology and history, because they make that map of who we are clearer in a way.

ACB What comparisons do you see between the mythologies of the di erent cultures?

CSDS Something that is very beautiful about Colombia is although we had a terrible past – the colonial past – there ended up being this marriage of mythologies and cultures. ere are similarities between di erent cultures’ mythologies, mostly with ideas of fertility, maternity, creation, and gods that become animals. at’s why I also love painting animals because I can see that all these ancestral cultures made gods into animals. e animals that I depict become representations. Some can be mythological representations of animals that already have a certain meaning. But there is also something nice about creating your own mythology with animals that mean something to you. I have always had a respect and a fascination for animals and I share this in my paintings constantly. It’s a way of putting animals on a higher pedestal.

ACB Can you relate the particular myth you were inspired by to paint First Fruits For e Son Of Bachué?

CSDS Yes. In this particular myth, a goddess appeared from a lake. She was the mother of agriculture, the goddess of water and fertile land. She came out of the lake with her son, Bachué, who she tasked with populating the earth. So, in some way, I am speaking about the virility of the male god, of the bull. I grew up with bulls (brought up by Santamaria's father for bull ghting) on a farm in Bogota, Colombia, so these creatures for me represent that virility, that masculinity, that strength. Bull ghting can be a very bloody art form. But I advocate for it because the bulls are truly honoured and cherished. ey grow up on our farm as kings. For ve years, they have the best life. en they have one really shitty day and if they prove themselves, they continue to be the stud for reproduction, to continue their bloodline. If not, they die, and we consume the meat. Bull ghting actually comes from the Minoan era where bulls were considered gods and so they could not just die for meat consumption. ere had to be a whole ritual behind it. So that’s how bull ghting came to be. And I’d rather see that than this senseless, horrible way of food production and animal production where they (the bulls) go to a slaughterhouse. ey’re in the dark and grow up in their own faeces. It’s horrible, as opposed to all the beauty that goes around the bull ght and the honour of the bull.

ACB Can you tell me about the symbolism of the masked gures in your work?

CSDS e masks are very inspired by traditional Colombian masks, which were themselves inspired by African masks. So they represent a lineage of cultures that inspire other cultures. ese new masks are like a new visual vocabulary for me because before I used to do mostly Colombian masks. I wanted to see what would happen if I started to create my own mask, my own language, to get inspired by the past but make it into something that became more of a signature in my paintings. e whiteness and the dark eyes are like a skull, representing death and the way that we deal with it, live with it and get used to it. And how that fear of death also makes you live. In First Fruits For e Son Of Bachué the

masked characters represent the thin line between life or death. ey’re also there to serve this need of spreading the seed of reproduction. e painting is intended to laugh a little bit at that instinct: that male instinct to spread the seed. ese alienlike creatures also speak to your subconscious. It’s a way for you to enter the painting, almost like an invitation to be with Bachué.

ACB It almost seems as though the masked gures are convoys for the bull.

CSDS Exactly. at’s a good way to put it. ey’re guides. at came also from reading e Tibetan Book of the Dead and how you should stop looking at death as a terrifying notion, and more like a guide: something to guide you through, and give you an appreciation for, life, to raise your morals, to see things from another perspective. I think these masks are a way of reconciling with my fear of death. I really like life. I enjoy living. As a painter, I think I have so many things to paint

"YOU HAVE THE SPACE YOU SAW THE PAINTING IN AND THAT INTERACTS WITH YOUR EXPERIENCE, WITH YOUR MEMORY, WITH THE ENVIRONMENT INSIDE YOUR MIND."

and so many things that I want to explore as an artist. Every time I get in a plane I think “If this went down right now, there are so many things I couldn’t do and create.” It’s more of a sadness of not living than a fear of death. e low beaks and the eyes are also very inspired by e Great Plague mask. I put this fear of getting sick into the mask and represent it through these creatures. It’s also very absurd. ese humans are like metahumans, full of history, like the humans that we fear to become mostly. ey’re like our ancestors.

ACB What is your relationship to Colombia, and how do you represent this in your work?

CSDS Colombia is a very passionate country. People embrace passion, love, poetry, romanticism. So, there is a lot of that in my work – a lot of colour, passion, and poetry. Interestingly, leaving Colombia to study abroad has made me more in touch with it. Colombia has also had a very violent past. Sadly, it’s had a civil war that went on for

- SHANE BERKERY

almost six years and we’re now in the whole peace process. So, it is a very turbulent country with a sad past, and a lot of Colombian artists from the past generation have made art about it. ey tend to be very political, and for good reason. I tend to be more positive, though the beauty and the darkness represent so much of being a Colombian painter. I grew up in an absolutely beautiful place that has so much biodiversity. My real expertise is our nature and animals. I think as part of a younger generation of Colombian artists, I have the privilege to show the beauty of Colombia instead of talking too much about the di culties that went on in the past, at least for now.

Right: Shane Berkery, 2024. Image courtesy of the artist's studio.

Top left: Cayetano Sanz de Santamaria, First Fruits For The Son Of Bachué 2024, oil on canvas, 80cm x 110cm. Image courtesy of the artist's studio.

CAYETANO SANZ DE SANTAMARIA

Cayetano Sanz de Santamaria, The Terrible Price Of Knowledge (detail), 2024, ink and watercolour on paper, 11cm x 15cm. Image courtesy of the artist.