Readers of the KW Magazine find that it achieves its objective, demonstrating the functional connection of various elements of culture to authentic worship. There is always an intentional illustration of how cultural elements such as language and music meet the objective The editor of the magazine is deliberate in providing delightful insights and inspirational case studies of how these elements connect with authentic worship. Scholars and students are always provided with stimulating information on which they can draw to advance their knowledge and enhance their work. o

As a Caribbean Contextual Theologian working globally, but researching regionally, this is precisely the kind of material I draw upon. There are fundamental and perennial questions problematic legacies of missionary hermeneutics, and the an African Caribbean Christian future, that emerge in this magazine. What I also appreciate is that good balance between intellect and imagination, rigour and creativity. o

The KW Magazine is a culturally literate publication. As such, is attuned to the socio-cultural nature of its location –amaica and the wider Caribbean - and thereby aware of the auses, influences and agendas at work that are contributing so much to the lack of flourishing of Caribbean people. The magazine begins with the lived realities of the reader The publication is not just about compiling knowledge. Instead, it seeks to convey what it means to be Christ-followers of African descent from a cultural perspective. In so doing, the publication is not seeking relevance but being relevant in contexts where biblicaltheological education has been borrowed, inherited and received. o

but we ’ re ba issue for yo focusing on la general, and the first ten New Testame feature Rev. leader of Testament tra What is your I mean, what learned to sp opportunity o you in that l does that hav y

Quite by chance (Yeah! Right! And this coming from the author of the book Godincidences!) we discovered that this year marks 100 years since the speakers of the Chichewa language, one of the primary languages in Malawi, got to hear God speaking to them in their mother tongue. In 1922, the Bible in the Chichewa language was published!

Another feature looks at a very special musical collaboration between three gospel artists. Hailing from three different countries connected by the Transatlantic Slave Trade, they sing each other's language, fostering unity through words and music.

We had help from Communication Studies interns this year, and you will

see a bit of their work in a couple of the articles. We hope to see much more involvement from young(er) people in the magazine, as we extend our relationships to high schools, colleges and universities. Look out for creative competitions, events, and other ways of connecting with each other. The aim of this publication is that we will get to know ourselves better, and get to know each other better, so that ultimately we will build deeper, more authentic relationships with our Creator.

This is the final issue of the KW Magazine in this format. Before you panic, though, I’m happy to tell you that we will be continuing with the mission of facilitating conversations about worship and cultural identity among people of African descent, both on the African continent and in the Diasporas. However, we will be communicating via Newsletter and Blog posts. If you have not yet subscribed, then please do so, here, so that you will not miss any of our exciting and informative posts: http://eepurl.com/gi01gv o

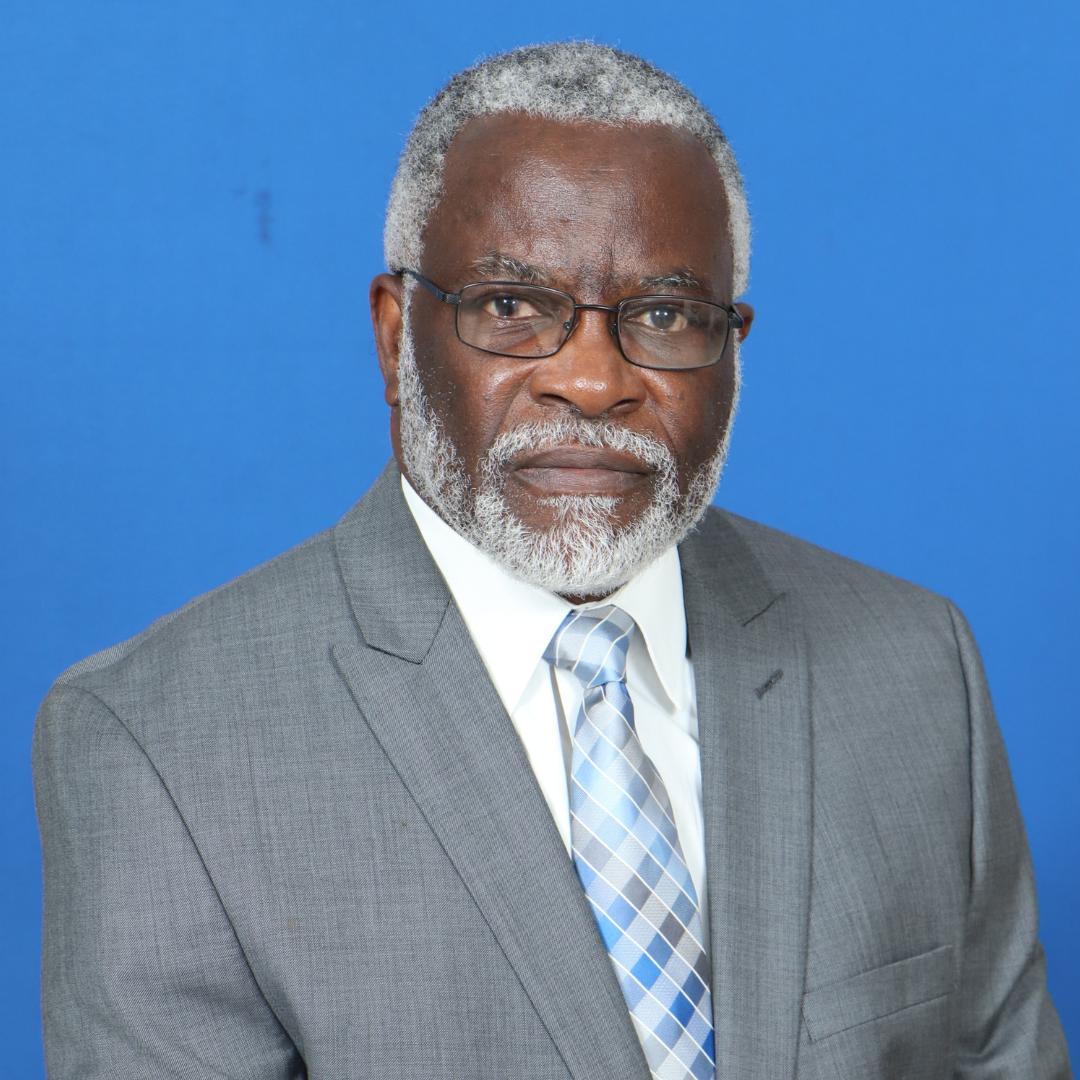

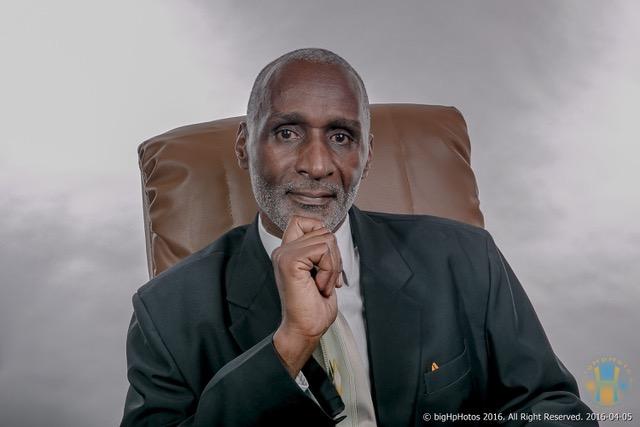

KW: Up until recently, we knew you as simply Bertram Gayle What is now your official title?

The Reverend Bertram Gayle it is! I am not big on titles, so I am perfectly fine with being called Bertram!

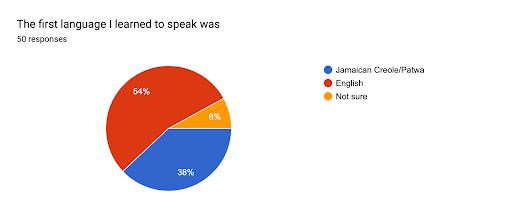

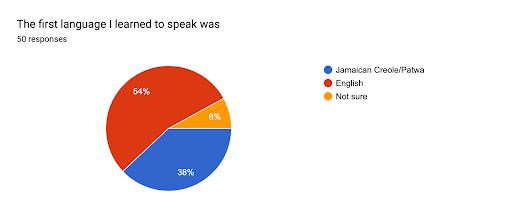

KW: What was the first language you learned to speak? What language was spoken in your home?

My first language is Jamaican (aka Patwa). This was the first and primary language of everyone in my home.

KW: You are well educated, having studied theology and linguistics and years of preparation for this current ministry. That required significant knowledge of the English Language

When did you develop this proficiency in English? Was it easy for you?

I did English courses in all the educational institutions I attended, except one, the University of the West Indies. Each of these institutions contributed to my proficiency in English. I did linguistics at UWI, so, though I didn’t do any of its English or foundation language courses, looking at the nature and structure of languages was a tremendous help. Also helpful were the three years I studied in Britain, and my training in translation. In retrospect, developing proficiency was somewhat difficult and long. I failed CSEC English! It would have been much easier, particularly in the earlier years, if my first language

was more intentionally and positively engaged I am not sure I have it all pat down yet, but I do manage to get by!

KW: You have almost broken the Jamaican internet with your appointment in the Anglican Church as well as with your focus on the Jamaican language and music in your ordination ceremony Was this your plan? At what point did you decide what the ingredients of this ceremony would be?

O yes! It was deliberate! I started thinking about the service soon after I was ordained a Deacon in 2021. Our services have a set structure or format There is no secret, therefore, with regard to the elements to be included. So, I didn’t begin from scratch. Though our services have set elements and a fixed structure, there is much room for creativity – in terms of language use, music style, wording of prayers, etc We always use a Psalm, for example, but it doesn’t have to be read. It can be chanted or sung! And there are various ways in which the Psalm can be read, chanted or sung. For any of our services to take off, then, one has to engage the set structure of the liturgy creatively – a simple, though not simplistic, creativity! In our tradition, we say, “Liturgy is work!” and work I did!

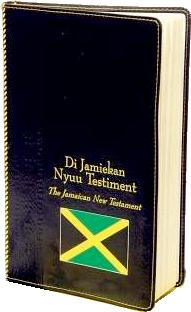

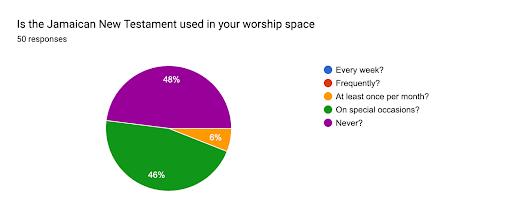

KW: How frequently do you use the JNT in your services in the Anglican Church currently?

I use the JNT in one form or another in most of the services I lead. I can’t speak to the frequency with which it is used by others in our denomination I can say though: my impression is that it tends to be featured in some of our churches primarily at Pentecost and at Christmas.

KW: What would you say is the primary reason you place such importance on the Jamaican language?

Definitely for communication! Jamaican is the language best understood by our people, so I engage the language for maximum results in the communicative process. Every other reason (its linguistic and cultural benefits, for example), though important, meaningful and dear to my heart, is secondary.

KW: We are extremely grateful to you for the leading role you played in delivering to us the Jamaican New Testament. What would you say were the main challenges in completing that project?

You are most welcome! I did enjoy my work. We faced several challenges. I briefly identify two such challenges –one is external to the language and the other is internal to it. First, there was (and continues to be) the issue of language attitude. Most Jamaicans, even many who have found it within themselves to affirm the language, display negative attitudes toward their language. They consider Jamaican

crude and, therefore, an inappropriate vehicle to communicate God’s word to us. This attitude is fuelled by misconceptions about the language and by its links to the experience of enslavement. So, we often hear people say, “Patwa has no rule!” or “It reminds us of a past we would rather forget.”

Secondly, there were languagerelated challenges Jamaican, like all other human languages, is primarily spoken. Unlike the European language to which most of us have been exposed, however, Jamaican doesn’t have a long history of being written This is to be expected, for, comparatively, Jamaican is a relatively new language and languages take onto themselves written forms years after they come into existence. It is for this reason the primary means by which people access the JNT is in its spoken form Reading and writing a language is a learnt skill; it’s not a natural linguistic behaviour. Seeing our people haven’t been taught this skill for Jamaican, we didn’t expect they’d be able to pick up a written text and read it off the bat like that There was also the issue of which variety of the language to use – from Kingston, Western or South-Western Jamaica, for instance. The Jamaican Language Unit, helped us in arriving at a decision. In addition to issues relating to the written and dialectal form of the language, we had to stretch the

language to communicate concepts or ideas with which Jamaicans are unfamiliar. With help from the Jamaican Language Unit, we also had to think more of the sound, word and sentence structures of the language.

KW: A cursory examination is revealing that only a small percentage of churches in Jamaica are currently using the JNT, even on special occasions. Why do you think this is so?

Why are more churches not using it?

A small percentage of churches use the JNT for reasons noted in the response to the previous question. Until we overcome the negative social attitudes toward the language, and the misconceptions that fuel them, we will continue to experience resistance to the use of the Jamaican Scriptures.

In addition, though the JNT is available in audio format, we are not so used to listening to the Bible read to us in the language in which it has been accessible to us for the longest while, English. What we seem to have done is to have developed an expectation to see a written text we can access by means of reading. The challenge is that we are not used to reading and writing the language, so the process frustrates many. This reality coupled with the fact that we harbour negative attitudes and ideas about the language, do not make us sufficiently motivated to put in the effort necessary to acquire literacy skills in Jamaican.

KW: What strategy would you recommend for getting more churches/ worship spaces to use the JNT?

Through a sustained promotion and engagement effort. Those of us who (can) read the JNT can use it more, especially in public spaces In my experience, the more people are exposed to the Jamaican Scriptures, the more they warm up to it. In using the JNT more frequently, we help to normalise its use in formal spaces. It also invites conversations that help us address misconceptions and negative attitudes.

We need to train people to read and write the language. Maybe we can start with readers – at least one from each church. We can build out from there. We can also have literacy competitions that make use of the JNT, and have Scripture engagement sessions or Bible Study groups in which people read, listen and interact with the JNT.

In other words, we need to engage the lessons God has taught us through marketing!

KW: What has been the most positive response to the use of the JNT in your ordination and subsequent services?

I have received several positive responses. It’s difficult to identify one as being the most positive. If I have to select one, however, it is that people said it helped them to connect in a way that was true to their identity. There

was no pretence, and people felt they could be themselves before God. I value this feedback, because I think worship and the worship experience are best when we lay ourselves bare before God, and remove those things that hinder us from offering worship from the depths of our being. These hindrances can be linguistic and cultural.

KW: What is your vision for the use of the JNT among Jamaicans? When do you think this vision will be realized?

My vision is for the JNT to become the default Scriptures we use in worship!

One of the realities that stood out to me when I was studying in Britain was that English and British culture were the default in worship. I was based in Wales, so Welsh was the default language among those who were predominantly Welsh speakers. My experience in Britain led me to contemplate seriously why Jamaican language and culture aren’t the default in Jamaica, my beloved home country! I am well aware of our complex history, but Britain, too, has a complex history of colonisation. They eventually got to the place where they threw off their colonial heritage and asserted their

own language and culture – or they so adapted their colonial heritage and transformed it into something that can today be identified as distinctively British. That is an important feature in the the story behind the English scriptures, for example. So, why do we think and act as if the adaptation process has ended, and we can’t have a church that is distinctively Jamaican?

I am afraid I cannot say that I know when this will be realised. We seem to be moving towards it slowly. I am not sure it will happen in my lifetime, but I think I will die knowing I played a small part in helping us becoming a church that truly reflects us.

KW: Tengk yu fi evriting we yu du! Waak gud an wan lov!

(Thank you for all you do! Live well and love everyone!)

Piis an lov! Tangks fi lisn tu mi! (Peace and Love! Thanks for listening to me!) o

“But a time is coming, and it is already here! Even now the true worshipers are being led by the Spirit to worship the Father according to the truth. These are the ones the Father is seeking to worship him. God is Spirit, and those who worship God must be led by the Spirit to worship him according to the truth.”

“Bot di die an taim de kom an it de ya nou wen di piipl dem we riili worship di Faada gweehn worship im ou di Spirit waahn dem fi worship an fram wie dong iina dem aat. Kaaz a dem de saat a piipl de di Faada a luk fa fi worship im. Kaa, yu si, Gad a spirit an dem we worship im mos worship im ou di Spirit waahn dem fi worship an dem mos dwi'it fram wie dong iina dem aat.”

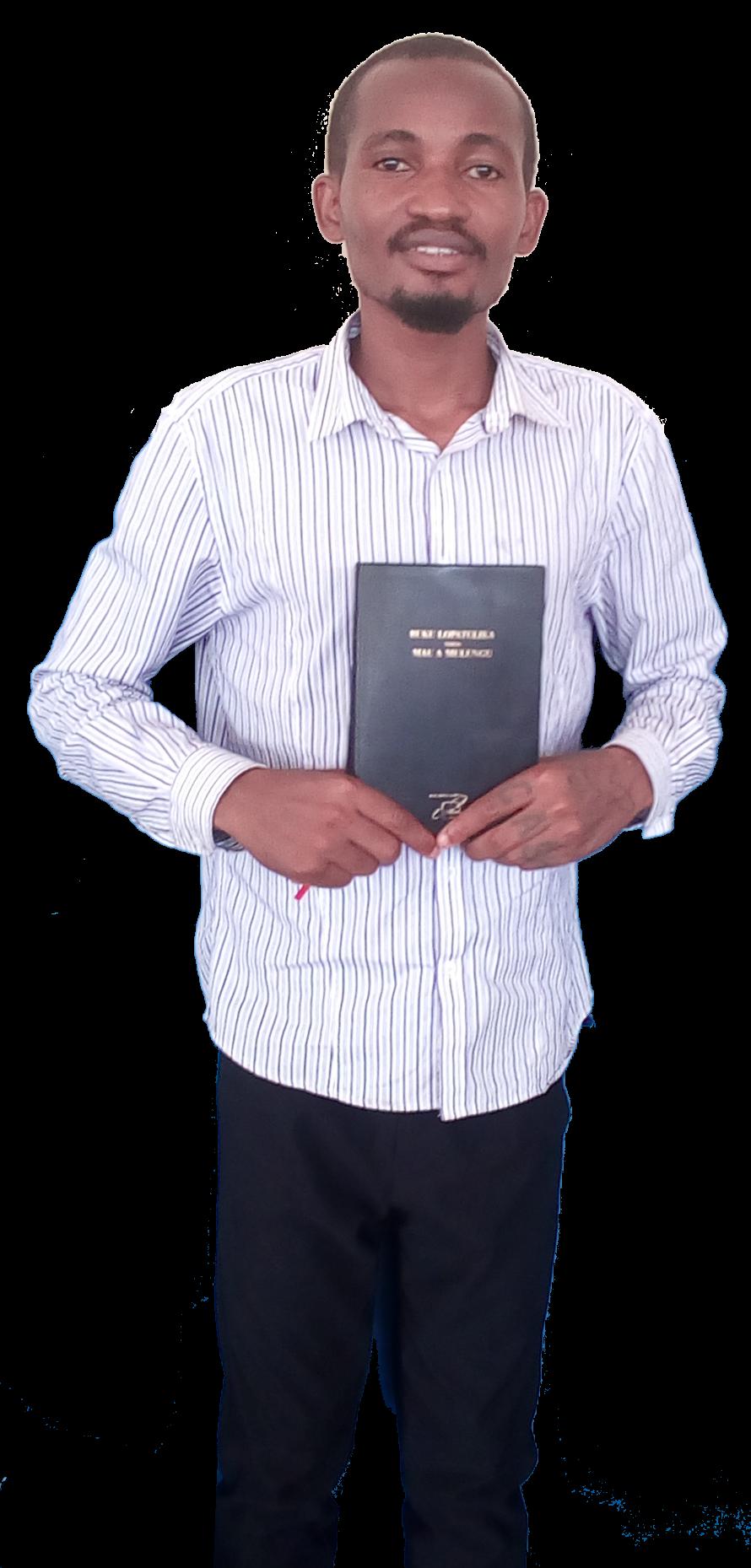

hile Jamaica celebrates 10 years of the New Testament in the Jamaican language, Malawi is celebrating 100 years since they received the entire Scriptures in Chichewa, their major traditional language! KW Magazine spoke with young Malawian musician/evangelist Reuben Liwewe, aka Zion Messenger, to get some of the details. Here is what he had to say:

"Buku Lopatulika ndilo Mau a Mulungu is the first Bible to be translated among all the languages in Malawi. The translation work took a long time - over 20 years - from the early 1900s to 1922. The translation work took place at Kaso, in Mvera, Dowa District. This work was done by The Dutch Reformed Church missionaries and notable Malawians. The Bible underwent orthography revision in 1936, and was revised

again in 1966. An Enlarged Edition was published in 1992 and recently there was a Text & Orthography revision in 2014.

Buku Lopatulika ndilo Mau a Mulungu is a literal translation, based on the Hebrew and Greek languages. It is a good Bible for those who would like to know what the original languages were like.

The translation has played a major role in church growth. People understand the Gospel using the Chichewa Bible. We also have a huge collection of Chichewa hymns and a lot of Chichewa gospel songs are being played in various 'media houses'.

When asked about class distinctions in the use of English versus Chichewa, Reuben confirmed that the upper class is attached to the use of English language while the lower class regularly uses Chichewa. However, the Church accommodates both classes by having two services - one in English and the other in Chichewa.

Unlike the situation in Jamaica, Reuben says he has not met any hindrance in the use of Chichewa in church. He says, “Malawi has the most welcoming people, and the church is playing a big role in spreading the gospel in remote areas as well as urban communities ” o

Connect with Reuben (Zion the Messenger) on Spotify at https://open.spotify.com/ artist/6dChod0Tmx9FmZmqk95lhQ?

O, gi Gad glory!

Gi Gad glory!

Me feel wan nudda part a me tomak open up!

Me tung free

Me a brede free

Me hed free

Me kyan swim an tun ober inna de water

An swing bout lakka fish

Me kyan dibe dung an cum up a blow bubble!

Me kyan larf an shout

Me kyan dance an a happy Me kyan shout plenti-plenti

Me happy

Me feel gud

Me feel gud gud gud!

Me ‘dialec’ loose out,

E get way E get way!

De chain an dem bus wey Bakra langwij min trap arwe E til ha sum arwe trap! But de chian bus wey!

Me say, de chian bus wey!

Arwe bus up de chian dem inna dis ya Wycliffe canfrance!

Arwe swing out de prison do wide-wide-wide Fu de prisna dem fu wark out.

Cum me peepl, tark u langwij’ Sing inna u langwij.

Open u heart an free up u mine

Open up u heart an tark inna u twang, U na prisna no mo

Dem min tek wey arwe langwij wen arwe cum fram Africa

Dem min tri fu mek arwe faget um anna tel u e na gud!

Na mek dem du um agen!

Tek bak u langwij an tark um free Rite um free- tink inna um free!

Jesas cum fu mek man free

E wan all smaddy fu hear E wud inna dem owan twang

E wan arwe fu hear E wud an hab um inna arwe mine

Fu arwe fu feel um deep inna arwe belly Wuk inna arwe pirit an wuk inna arwe hart Wuk deep inna arwe soal.

Jesas set arwe langwij free

A freedom dis ya Dis ya a de tru emansipashun arwe minna wiat fa, Dis ya, a wa go mek free fu tru!

T R A N S A T L A N T I C C O L L A B O R A T I O N

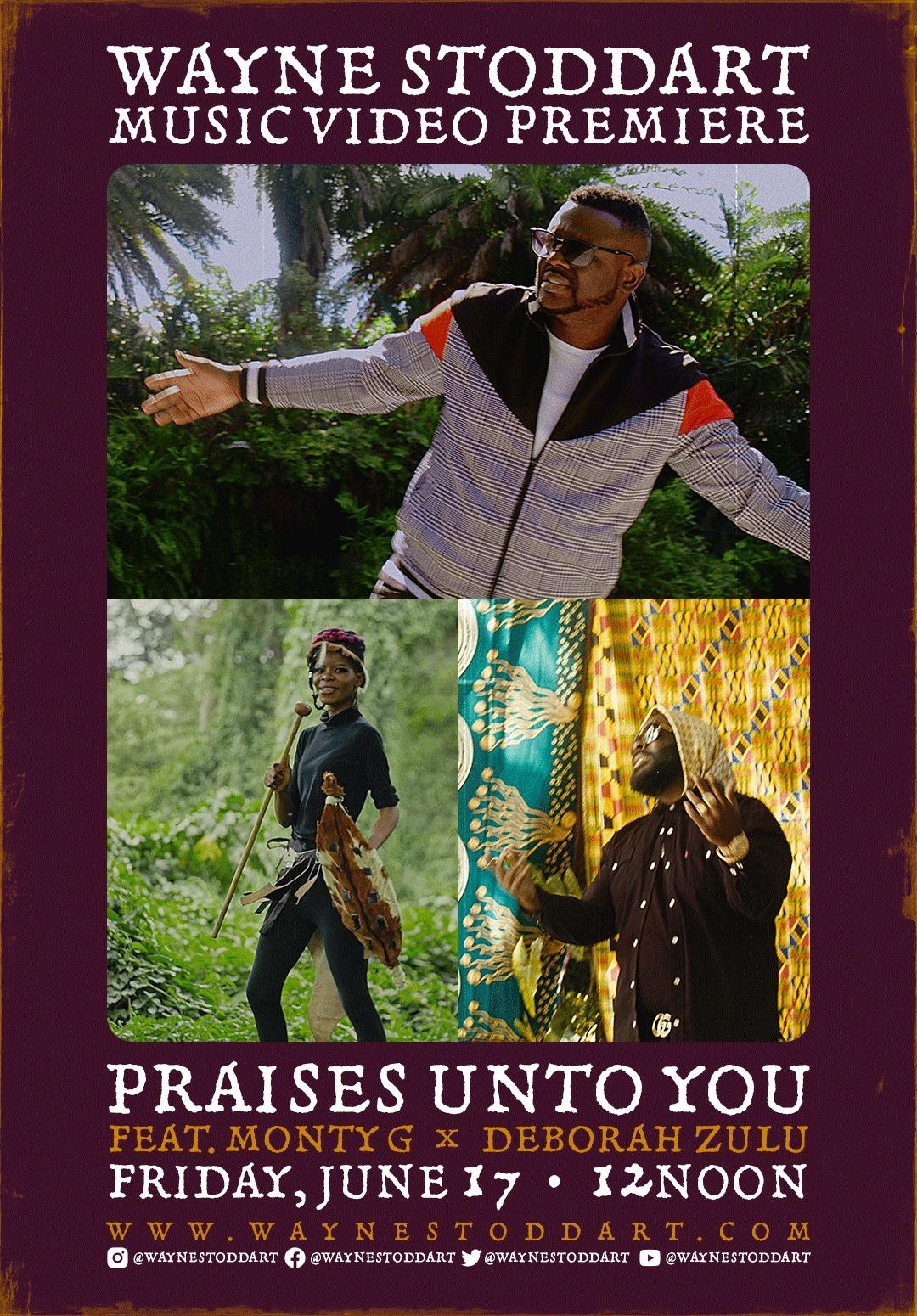

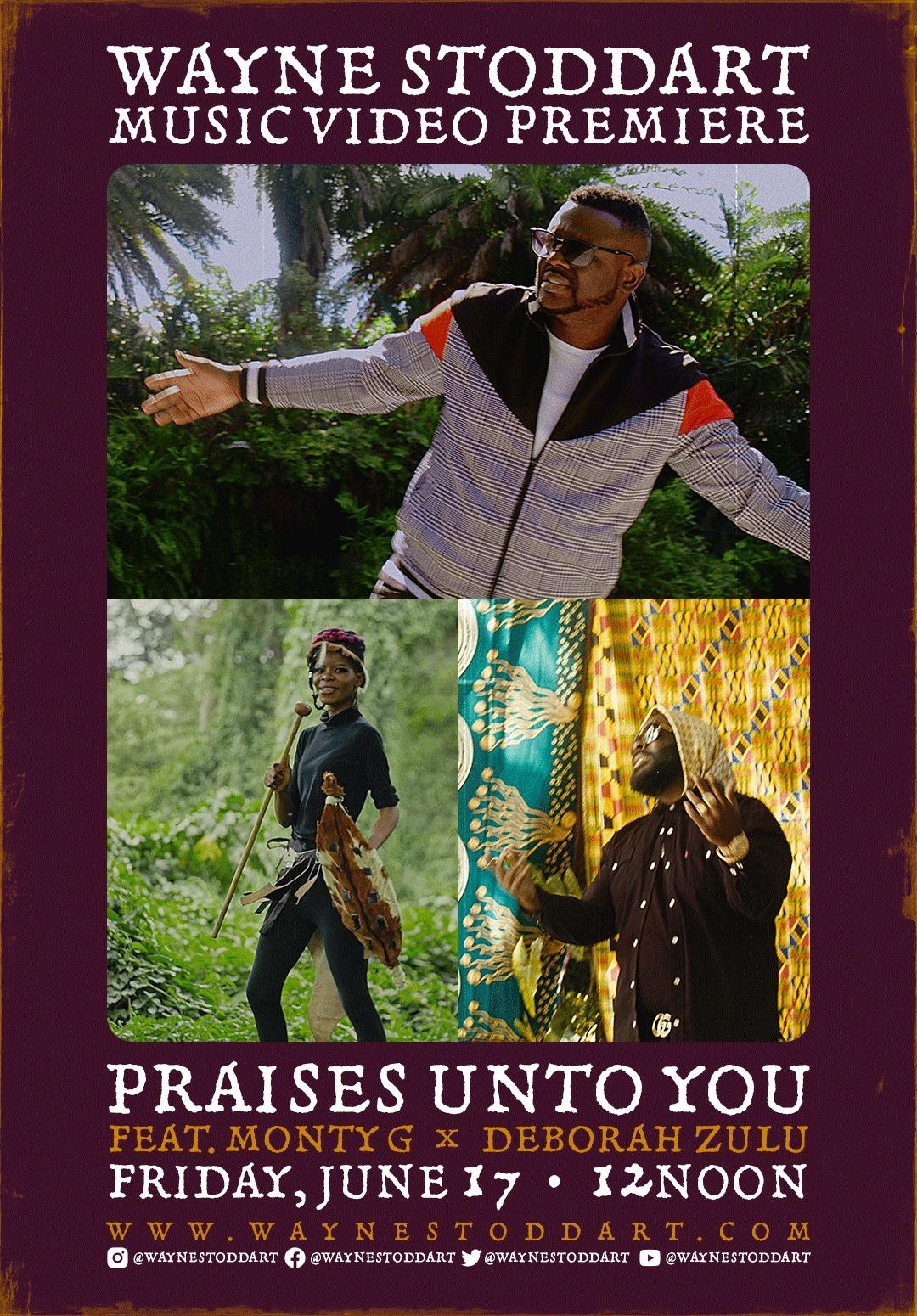

An exciting collaboration project was released on June 17, 2022. The song and video involving Jamaican Wayne Stoddart, Bahamian Ramont ‘Monty G’ Green and Zambian Deborah Zulu covers three languages and musical styles. It is simple, and yet intriguing, and drew the attention of the KW Magazine team because of its African-based multicultural mix.

We just HAD to get some information from the artists concerning this project!

writing of it a collaborative effort?

Wayne: For melody and lyrics, I sent my words and melody to Deborah and she added her Afro Rhythm, and switched around a few of the words to say it the ‘Afro-perfect’ way. Monty basically wrote his verse.

KW: Why did you choose these two artists?

Wayne: I felt they could bring the color and diversity I was looking for in this global praise offering

KW: What has been the response from the J a m a i c a n community?

Wayne: Everyone in the Jamaican community loves this song. It connects us to an authentic worship that stems from our root language and from the Bible (Psalm 108).

KW: Who wrote the song? Was the

KW: How did you feel including your heart language (Jamaican/Patwa) in

the production?

Wayne: It is amazing! Being able to use words from Psalm 108 and blend them with Jamaican Patwa and native motherland dialect... That was epic and timeless.

KW: What did you want to accomplish with this song?

Wayne: We are able to speak to each other's unique audience and fanbase all at once, crossing cultures and transcending genres.

Wayne.

KW: What has been the response from the brethren on the African continent?

Deborah: To hear Pastor Wayne Stoddart singing in our language is something my people are proud of.

KW: What was most challenging about this project?

KW: Why did you agree to do this collaboration?

Deborah: It was my desire to work on something with the Jamaican people and it happened to be through Pastor

Deborah: The most challenging part was when trying to put all interests together. As artists we each have a different touch and being featured on a song is something which must always showcase never hide the identity or the touch of each artist. The video part was interesting; having the beauty of all countries put together was another thing. In all this we simply wanted the best for our fans and I'm sure we gave it our best When they see Monty G, they will recognize him, Deborah Zulu will be recognized as well as Wayne, the owner of the song. Can you imagine putting all this together for a beautiful outcome? Indeed it was so challenging!

KW: Apart from the English parts, what is the name of the language you use in the song? Is it used in church music in Zambia?

Deborah: Bemba is one of the most common languages from the northern part of Zambia and yes, it is used in churches.

KW: What is your vision for the impact of the production on the African continent, America and the Caribbean?

Deborah: My vision is to see every nation sing praises and dance to this song. Let this song bring joy and the assurance of peace as nations sing along. It is praises for the nations!!!!!

continent of Africa?

Monty G: No

KW: How did it feel to minister alongside an African from the continent?

Monty G: It felt really great. It gives you a sense of connection.

KW: Where do you minister the most?

Monty G: I minister mainly in the USA and the Caribbean.

KW: How is it that you are the one who sings most of the Jamaican language in the song?

Monty G: Lol! That’s funny! I've been a DJ since I was 10 years old. I’ve been a student of Reggae music most of my life, so by now it is natural to me!

KW: What was the most significant thing about this collaboration for you?

KW: Have you ever ministered on the

Monty G: The unity between the three countries, and the connection through Christ. o

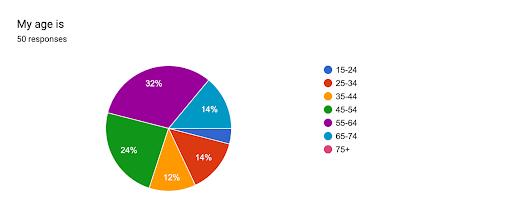

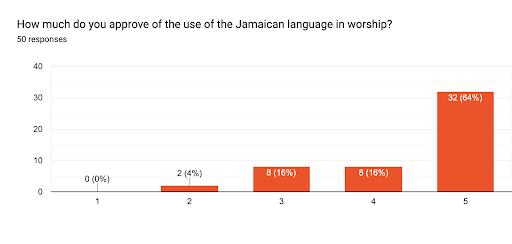

In this Vox Pop we wanted to hear from Jamaicans at home and abroad to find out whether they know about and are using the Jamaican New Testament. It turned out to be more of a mini research. Perhaps this is why getting people to complete the questionnaire was like pulling teeth! At some point, we would love to do a wider survey to get a fuller understanding of Jamaican people’s awareness of and attitude towards the use of the Jamaican New Testament. Nevertheless, this gives a fair overview Let us know what you think!

I should perhaps also say that the profile of the respondents may be a reflection of the people in my circles. This could be why most of them are older than 45 years, female, mothertongue speakers of English, living midtown or uptown and holders of degrees at some level It is significant that only one person identified themselves as living downtown/in the inner city. The expectation is that most of the people who live in the inner city are mother-tongue speakers of Jamaican.

15-24 - 4% 25-34 - 14 35-44 - 12 45-54 - 24 55-64 - 32 65-74 - 14 (72% age

GENDER

Female: 70% Male: 30%

THE F Englis Jamai Not Su

Secondary: 2% Skills Training College: 4% College/University: 42% Post-Graduate: 52%

Baptist: 13.8% (4) United Church: 13 8% (4) Non-denominational: 20.7% (6) Evangelical: 10.3% (3)

Uptown: 22% Downtown: 2% Midtown: 38% Rural: 18% Overseas/Other: 20%

Almost every week: 78%

Once per month: 14%

Frequently but not regularly: 4% Never: 4%

DO THEY KNOW THERE IS A JAMAICAN NEW TESTAMENT?

Yes: 90% No: 10%

Every week: 0% Frequently: 0%

At least once per On special occas Never: 48%

ON A S

1: 0% 2: 4% 3: 16% 4: 16% 5: 64%

DO THEY OWN A PHYSICAL COPY OF THE JNT?

Yes: 22% No: 74%

I had one but lost it/gave it away: 4%

DO THEY ACCESS THE JNT ONLINE?

Yes: 66% No: 34%

AFTER WATCHING A VIDEO OF A READING FROM THE JNT (THE BEATITUDES) , ON A SCALE OF 1-5, HOW CONNECTED DID THEY FEEL?

1: 0% 2: 2% 3: 18% 4: 26%

5: 54%

- (I have) An issue with a phrase such as ‘Bwai Pikni’ in reference to Jiizas

- None other than it should be commingled, wisely, with standard Jamaican English

- No objection per se. Only concerned that less conversant English speakers may not be sufficiently challenged to master the English language (the language of Business) if worship is predominantly in Jamaican.

- The competence of the reader

- It can be difficult to read Jamaican language as there is no standard spelling for the words. Also even though that's how the majority of the population speak they may not be able to read it, which may take away from connecting with God

- Not sure, because I am not use to hear Jamaican language in service

- I would love to see more use of the Jamaican language in worship.

In this year when we are celebrating 10 years since the launch of the Jamaican New Testament, we realize that there is still much more to be done to introduce the translation to the Jamaican people. The majority of people who know about the JNT approve of it. However, it is not being used in most churches, and even when it is being used, it is primarily reserved for special occasions. We look forward to an increase in usage over the next ten years! o

As a child growing up in rural Jamaica "Go pluck likkle Sersi (Cerasee) fi get you wash out,” is a phrase that my grandma would often use as she lamented on our sweets intake. Growing up in the Caribbean it was not uncommon for our grandparents to tell us about the benefits and various uses of 'bush medicine,' as it is commonly referred to Herbal Medicine is not unfamiliar to us in the Caribbean, as our African ancestors used herbs in healing and it

has been then passed down through generations. The West African slaves brought their herbal knowledge which was embedded within their culture with them across the Atlantic. Their herbal knowledge survived and has been adapted to the new environment, namely the Caribbean.

Cerasee is a bush medicine that I grew up with. It was my personal detoxifier. We used to pluck the 'Sersi' plant and eat the inside of the small orange fruit

that grew on the vines as children. Cerasee is commonly made into a tea and can be used dried or green.

To make the tea, we would boil the water, turn off the heat, and add the plant to the water, covering the pot and allowing it to steam/ brew for about 5 minutes. We would then have a warm cup of cerasee, despite the fact that it was bitter. The health benefits were endless and instilled in us from a young age

Cerasee tea is a bush tea made from the leaves and stems of the Momordica Charantia, or Bitter Melon plant. In the Caribbean, it’s used to treat multiple health conditions, including diabetes.

Health Benefits of Cerasee

l

Reduced cholesterol l

Reduced blood sugar and blood pressure l Eliminates parasites and worms l Helps with constipation, stomach distress, and digestion l Flush toxins from the body l Treat eczema and rash on the skin l Treat Menstrual Cramps

Leaf of Life, Lemon Grass (Fever Grass), Soursop, and Aloe Vera are all popular herbs in the Caribbean with numerous health benefits. Our forefathers used these plants to aid in the healing process, and they lived long and healthy lives. The relevance and importance of herbal treatments and natural medicines is a part of our culture and who we are. Let us continue to use the knowledge of our ancestors to lead healthy and fulfilling lives, relying on Mother Earth’s healing remedies. o

Prepared by Kayla Hutchinson, UTech Communications Intern.

Heathline.com/nutrition/ceraseetea-benefits

Whether it is Ebonics, Patwa, Pidgin, or Creole, all these languages matter for they express the cultures of people in a way that is peppered with their histories, traditions, spiritualities and local theologies.

Irs old, when I first e with the words of ers. Its impact was ter significance to st. It was well into overed that Jesus ean Aramaic, an of an oppressed raised its head, nces of colonised century or the 21st is marginalisation n the language of e language of the he powerful is aised, and the sed and oppressed ridicule as being would have been d have spoken reek. This was so ical, military and he Roman Empire as the ordinary

C Palestinian Jew first language or was an Afroasiatic Afrasian or Hamitoc Afroasiatic, is a of about 300 n predominantly in the Horn of Africa as related to the

same family of indigenous languages as North-Eastern Africa. The language of the first century colonisers was Greek and later Latin. The language of Hebrew was the language of the ruling priestly and legal classes described as Pharisees, Levities and Scribes However, Aramaic was the Lingua Franca of the Semitic world. It is interesting, that in sermons all over the Caribbean we hear preachers saying, “the Greek said this and that”. We seldom hear anyone quoting, “the Aramaic said”, although there were at least six versions of the Aramaic New Testament. That’s because we are still suffering from what I call ‘longcolonialism’.

There is a growing body of evidence pointing to the original New Testament being written in Aramaic rather than Greek. When the question was asked, “could any good thing come out of Galilee,” that could very well be due to the fact that Aramaic speakers from Jerusalem thought that Galilean Aramaic was crude and rough.

We note that in several cases Jesus is quoted speaking in the Aramai language in the Gospels. What is cle in these incidences is that it is alwa when Jesus is expressing intimat personal affection and compassio The most common Aramaic word used by Jesus is “Abba”, (Mark 14:36) as he addressed His Heavenly Father. We are reminded that “languages are more than just words; they connect

people, tell stories, convey wisdom and traditions as well as define who we are”.

So whether it is Ebonics, Patwa, Pidgin, or Creole, all these languages matter for they express the cultures of people in a way that is peppered with their histories, traditions, spiritualities and local theologies. God has spoken and continues to speak in the vernacular and indigenous languages of ordinary people. So, I wonder what was lost in the translations of the Bible into the language of the Grecians and the Anglo-Saxons? Hmmm o

Editor’s note:

See ‘Jesus and Aramaic’ K B Napier www.christiandoctrine.com/christiandoctrine/life-of-christ/1324-jesus-andaramaic visited 25 November 2022.

‘Government of Canada makes historic contribution to support indigenous languages in the North’ www canada ca/en/ canadian-heritage/news/2022/11/ government-of-canada-makes-historiccontribution-to-support-indigenouslanguages-in-the-north0 html# visited on 25 November 2022.

Ronald A. Nathan, is enior minister of the ard AME Zion Church, son, St Michael, ados He is a public ogian, author and writer an African Affairs and Black Theology.

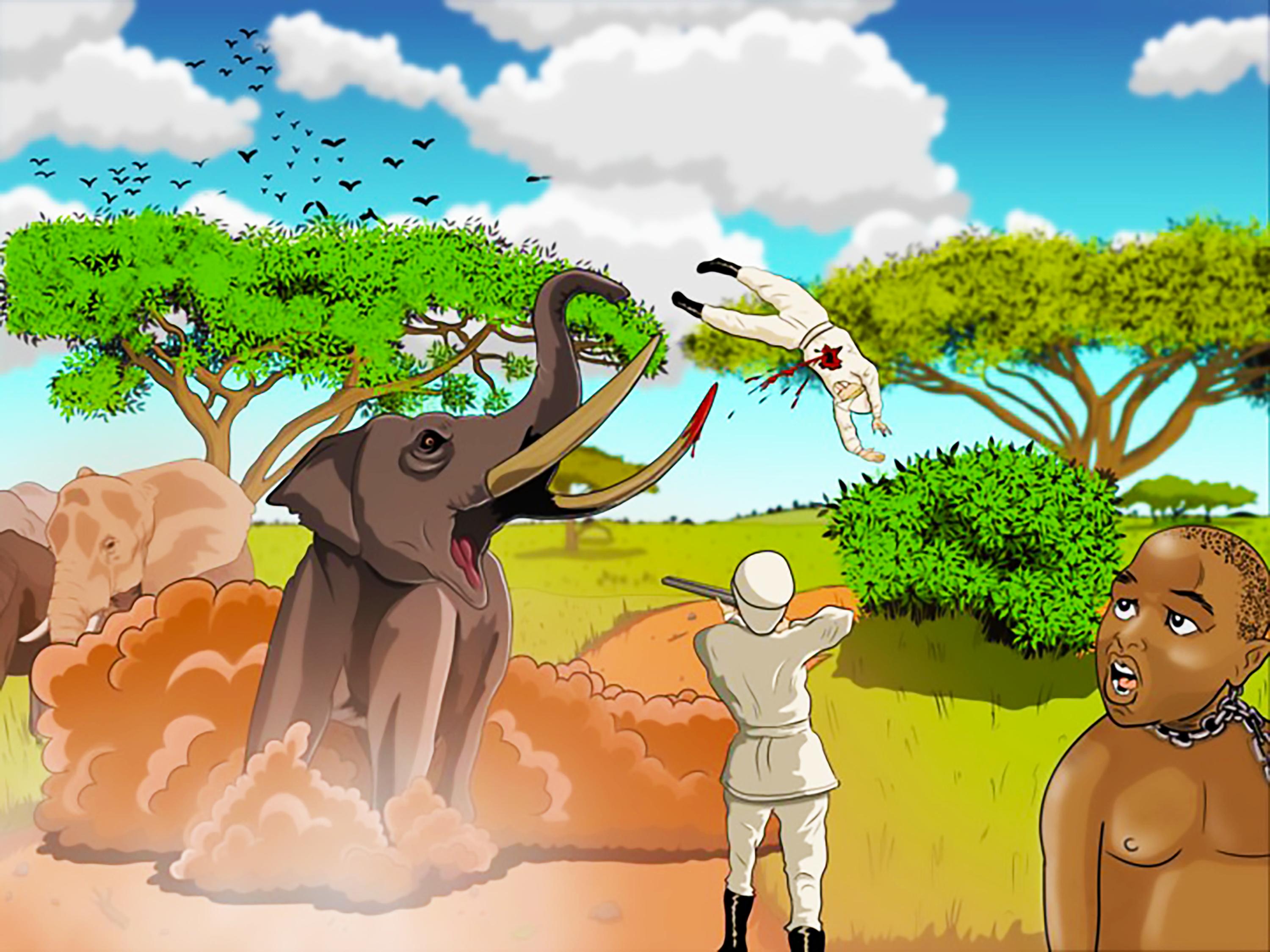

Setting: Enroute from a remote village in Nigeria, through its hinterland unto the West African coast; to somewhere on the Atlantic Ocean.

Oke came awake with a nagging thirst, a burning in his throat and his belly churning. He was lying on his side and could feel a tingling from his ankle to his hip bone.

For a moment of confusion, Oke wondered where he was and then the horror came flooding back. He shivered with renewed fear because if the march from bush

had been horrific, the trip into the big blue water had sent him completely out of his mind. Before the line of chained captives reached the coast, they were attacked twice and lost about 30 captives.

First, the line was broken through by an angry herd of elephants that suddenly emerged from the bush. They trampled the unfortunate women and girls who were in their path and when one of the white men shot at the gigantic female that led the herd, the enraged animal turned upon him and lifted him with a tusk that pierced him through. The animal flung him aside and then led her tribe away from the carnage.

Oke, from where he stood looking up at the giant creature, felt sure that he saw disgust in the mother elephant’s eye before she nudged her offspring with her trunk and led her charges back into the forest.

The slaver bled to death before they had gone another mile and three of the strongest men were unchained and made to dig his grave a few meters away from the narrow track that snaked like a vein through the African bush.

A day later, they walked into the path of a bunch of hyenas feeding upon the carcass of a leopard.

They had hardly gone a chain past the scavengers when a scream rent the air It was a mother who screamed for her small child who had been bitten savagely by one of the hyenas that had left the feasting party to trail the captives.

The vicious animal had torn a hole into the side of the little boy’s abdomen and he was bleeding profusely

To Oke’s horror, one of the white men, the very one who had snatched him from the river, turned and aimed his gun at the little boy The mother screamed again but this did not stop the monster and he shot the bleeding child to death, detached him from his coffle and threw him into the bush Oke descended into shock and walked in a stupor for the rest of the journey to the coast

Now he lay on his side in the darkness of the ship’s hold with only his nose, ears

and hands to help him to make sense of his surroundings. He heard a man groan next to him, heard a high- pitched cry respond and realized belatedly that the voice was his. As he opened his mouth to breathe, since his nostrils were clogged, he felt himself choke upon the hot fetid air.

Oke coughed and felt pain radiate from his ribs to his back. He knew he was desperately ill and longed for the calm, loving presence of his sister-mother. He also wished desperately that someone could explain where the monstrous ship was taking them. As a child, he had heard stories of people who had been snatched and taken away by slave raiders, never to be seen again and slowly, his despair settled over him like a cloak as he accepted that like the victims he had heard of in those fireside stories, he too had been snatched away and would never be seen by his loved ones again.

In the belly of the ship, Oke lifted his voice and wailed a sorrow chant. The sound was picked up by a male baritone in a far corner of the ship’s hold, returned to Oke by an assembly of male voices and soon the entire hold of the ship filled with the sound of the song. As the ship rolled and tossed on the waves of the Atlantic Ocean, the women heard the sound from the men ’ s waters and they answered in their own lament.

Oke stopped singing after a while and listened instead, taking comfort in the realization that his sorrow was not his alone. (To be continued). o

By Sylvia Gilfilian Educator & Author

"The song was 'Free, free, free! I have been set free, since I found the Man, the Man from Galilee!' She was flinging her arms up in the air, and she was swaying her body, and she was praising God."

In 2005, I did some recordings of the New Testament with a SIL [Summer Institute of Linguistics] missionary that was in Antigua. The one I did was from John with Jesus and the disciples in the boat who were frightened I went to one of the country churches to demonstrate what I was doing in bringing the Creole language to bear on the New Testament. To my surprise and utter delight, the pastorPastor Dexter Lawrence - dropped down on the floor and started to roll and laugh, and he said “Yu tingk a now wi want fi hear di Bible ina wi owna language?” He rolled all over the place! We were amazed at his response but when the Bible is read so that people understand it in their own language, they develop more interest and a greater love for the Word. This is because they hear God speaking to them in their own language. So it is something that I really do advocate that we do more often.

In my own ministry, I always try to speak as much as I can in the language of the local people to whom I’m speaking or teaching, even when I’m preaching here in Antigua, I find that people respond well, and seem to learn better.

A number of years ago - it might have been in the 80’s - I went to a crusade and I was really struck by a sister who was dancing so freely in an old

Caribbean way, as the music itself was Caribbean rhythms. The song was “Free, free, free! I have been set free, since I found the Man, the Man from Galilee!” She was flinging her arms up in the air, and she was swaying her body, and she was praising God. You could see that it was something happening between her and the Holy Spirit as she sang that song and thanked God for setting her free.

It’s not only the translation of the Scriptures into the Creole language, but our music too, which means a lot when we worship God in our own vernacular. Personally, I love the hymns, but I also love the worship and the praise in our own vernacular; our own language and our own rhythms. Again, I would like to say that I will always advocate for it because this is very necessary, speaking as someone who is interested in the culture.

I believe that we reach people much more easily in their ears, in their hearts and get their attention, when they hear anything to do with the Bible and God, in their own language. Their soul and their faith are engaged when they hear it! o

Iam Lloyd H. Millen, son of the late Ishmael and Dorcas Millen of Rosetta District in St. Ann, Jamaica. I came to faith in Messiah Jesus at age seven. Walking with Messiah, Jesus since then has been my life passion.

My first involvement with the Jamiekan Nyuu Testiment Projek was in July 16, 2008 I was selected by my denomination to attend a support breakfast for the launch of the project in Kingston, Jamaica. I was excited with the assignment. I saw it as an opportunity to voice my cynicism to the project. Like most Jamaicans I felt it

was a nonsensical waste of time and money.

At the time, I thought I loved the Jamaican PATWA It was great for us Jamaicans to express ourselves in daily life, and the performing arts, but to translate the Bible into PATWA was a totally different matter Like many others I saw it as an exercise in futility. I had accepted the view that PATWA was not fit for Bible translation. After all, the Jamaican Creole was an unofficial, none standardized, oral, exslavery language that was scoffed at, despised and denigrated by the intelligent. The opinion makers of

Jamaica abhorred the idea of the Bible in Jamaican Creole In hindsight, I realized that I was a victim of linguistic prejudice I discovered this linguistic prejudice was not confined to the PATWA It was indicative of the prejudice against the people of the language- the masses

On the morning of the launch of the project I started out for the Knutsford Court Hotel in New Kingston. As I entered the semi-full JUTC bus in Portmore St. Catherine, I ran straight into Messiah Jesus in the person of the Holy Spirit. He confronted me with these words, “Son, I have always spoken to my people in their own native language.” He then flooded my mind with the account of the Advent of the Holy Spirit on the Day of Pentecost recorded in Acts 2. His voice in my spirit was gentle, firm and convicting. His presence over me was so awesome, I began to weep. I wept all the way to the Hotel. I knew then that somehow, he had a plan for my involvement in the project, but I had no clue how.

I got to the hotel late because of a traffic delay. I would have been content to slip in at the back unobserved but was ushered to the front and seated a couple paces from the podium. I was captivated as I listened to the various presenters. The final speaker made an appeal for people to support the project. I offered myself to help where possible

Two weeks later the project coordinator, Bertram Gayle, invited me

to a training workshop. I was about to decline the invitation when the Holy Spirit reminded me of my July 16 experience and commitment I hesitantly consented to attend the training That event sealed my commitment to the mission.

I am absolutely thrilled to have been chosen by the Lord to be a part of this historic undertaking. This translation will have an eternal impact on the psyche and the history of Jamaicans globally. The Bible in the Jamaican tongue is revolutionary. Religion, politics, culture, and education in Jamaica are on the verge of a new day. The Bible in the Jamaican tongue will emancipate the people from mental slavery. To lose the people’s tongue is to lose their minds. The masses have not yet experienced the revolution, but like Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. I have a dream. I have a dream that one day Jamaicans everywhere will be liberated into the knowledge of the glory of Messiah Jesus through the acceptance of the Bible and the Gospel in the Jamaican tongue.

I have great joy delivering the Gospel, my sermons, motivational addresses and public presentations in the Jamaican Language. I am thrilled at the animated responses of youths and adults, learned and unlearned, urban and rural folks to the Jamaican language. I am amazed at the almost instant transformation of many from opposition to animated support as they listen to the reading and preaching of

God’s Word in their own national tongue.

Preaching and teaching the Scriptures in the Jamaican language has become a passion of mine. I have discovered that the use of the language in the formal space is very liberating to the hearers, especially those who struggle to manage the Jamaican English. The educated users of the Jamaican English are also captivated by the use of the language in the formal space by a speaker who knows and manages the language well. When the educated discover that one can deliver a public address, teaching lesson, or motivational speech with accuracy, proficiency, flexibility and humor, they are immediately disarmed of their obstinacy against the language It is

absolutely gratifying to observe the transformation.

There is still a great deal of opposition to the Jamaican New Testament. The stigma and opposition goes deep into the Jamaican psyche. Ideologies and attitudes are hard to change. But my dream urges me on. Our people may not fully appreciate the significance of God’s Word in our native language in my lifetime. However, I am absolutely convinced it is just a matter of time that the full impact of the translated Scriptures will be nationally felt. The trajectory has been fixed. It will not be invalidated. Jehovah’s hand is in it. It will prevail. o

Bishop Lloyd Millen, New Covenant Bible Chapel, St Catherine

Bishop Lloyd Millen, New Covenant Bible Chapel, St Catherine