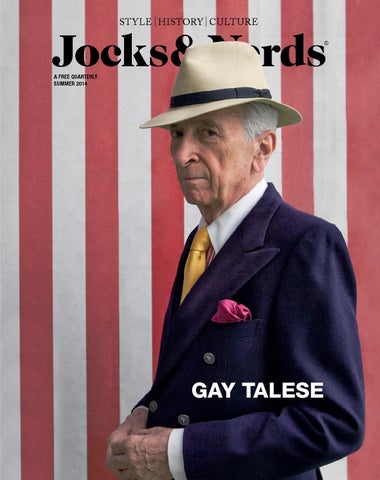

STYLE HISTORY CULTURE

A FREE QUARTERLY SUMMER 2014 VOLUME 1 ISSUE 11

©

“How people deal with failure is usually more interesting than how they deal with success.”

GAY TALESE www.jocksandnerds.com

STYLE HISTORY CULTURE

A FREE QUARTERLY SUMMER 2014 VOLUME 1 ISSUE 11

©

“How people deal with failure is usually more interesting than how they deal with success.”

GAY TALESE www.jocksandnerds.com