Link: https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2023/08/ira-climate-billdiscounts-home-electrification/675013/

Please see link above for source text.

Link: https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2023/08/ira-climate-billdiscounts-home-electrification/675013/

Please see link above for source text.

August 14, 2023

Last April, I decided to break up with my gas company. It wasn’t me; it was them. Like so many other fossil-fuel companies, SoCalGas was lobbying against clean energy while it continued to spew carbon pollution into the atmosphere. Yet here I was, an academic who had devoted my life to advancing clean energy, still paying them money, month after month. I’d had enough.

But like a divorce after a long marriage, the process was even more complicated than I had thought. I had to remove all the appliances running on gas and swap them for clean, electric machines. Goodbye gas furnace. Goodbye gas stove. Goodbye gas fireplace. And good riddance. SoCalGas wasn’t my sole energy provider, but I vowed to go one step further and run my home without burning any fossil fuels at all.

In addition to my home renovation, I was also working on a much bigger decarbonization project last year: getting a climate bill out of Congress and onto President Joe Biden’s desk. Those efforts were repeatedly stymied— until out of nowhere, a year ago this week, the Inflation Reduction Act became law. By far the biggest climate bill in American history, the IRA is

stuffed with programs: hundreds of billions of dollars to spur clean-energy manufacturing in the United States, push coal plants into retirement, and clean up pollution. But the parts of the law that are most quickly changing the country are the incentives that make it cheaper for Americans to break up with fossil fuels. One home improvement at a time, I’ve seen firsthand just how transformative the IRA will be—and what is still needed to ensure that this law lives up to its full potential.

In a sense, my electrification journey started long before I vowed to part ways with my gas company. When I bought my electric vehicle six years ago, federal and state tax credits brought down the sticker price by $10,000. But, over time, many cars no longer qualified, making EV purchases more expensive up front. Last August’s law fixed that, providing new, more generous tax credits for both new and used EVs. If electric cars seem to suddenly be everywhere, this is a big reason. Even though rolling out the rules for these incentives has taken time, EV purchases have rapidly accelerated; in California, one in every four new cars sold is now electric.

America is finally realizing just how great these cars can be. As many other EV owners have learned, these cars are cheaper to charge than their gas cousins are to fill up at the pump, and they require less maintenance. Apart from replacing the tires, I think I’ve spent $150, total. And the best is yet to come: Starting next year, buyers will be able to get their EV refund at the dealership, instead of having to claim a credit when they file their taxes.

The IRA supercharged my electrification journey. These kinds of home improvements can be expensive, but they became significantly cheaper after many of the law’s provisions went into effect in January. From the beginning, I knew I wanted to cover my roof in solar panels. That way, I could generate clean energy for my house and car. I also got a battery that plugged into the solar panels so I could have backup energy at night and during a power outage. The IRA extended solar-panel discounts that have existed for decades, and applied them to the battery costs too. This essentially made the whole system 30 percent cheaper.

Over and over again, I was greeted with discounts. At the top of my wish list was a heat pump. These machines are like magic: They draw heat from the air outside (even in the winter!) to heat water, or heat and cool the air in your home, without directly using any fossil fuels. In January, I installed two heat pumps—one for water and one for the air—and I’ll get $2,000 back on my taxes next year. Last year, heat pumps outsold gas furnaces, and the IRA will undoubtedly increase that margin dramatically.

With a home decked out with solar panels and heat pumps, my goal was finally in sight. One of the last and most important decisions I made was to replace my gas stove with an induction cooktop and electric ovens. From a carbon-pollution perspective, this was not the biggest project. But for my family’s health, it was essential. A few months ago, I bought a small airquality monitor and started to observe with my own eyes what scientists have been telling us: Cooking with a gas stove is, by some measures, on par with secondhand smoke. No one is “taking away gas stoves,” but if you have one, you might consider replacing it. Your lungs will thank you. With an induction cooktop, my home is healthier. And did I mention that it boils water way faster? No wonder many chefs love them. They’re better.

Last month, when I received a refund check from SoCalGas, I knew I’d finally done it. I’d severed my last connection with the company. And thanks to the IRA, it was easier than I’d expected to fully electrify my home: When I file my taxes next year, I’ll save thousands. But my home is just one in this country. If we want to meet our climate goals, we’ll need a lot more people to go all electric, a lot faster. According to the electrification nonprofit Rewiring America, where I am a senior adviser, over the next three years we need the federal law to spur an additional 14 million clean purchases: heat pumps, solar panels, EVs, and more. And opting for clean energy at home is particularly important going forward. As climate change accelerates, our homes are becoming even more important refuges. Near the end of July, almost 200 million Americans were under a heat or extreme-weather advisory; a month earlier, 120 million people had been cloaked in thick smoke.

Even with the IRA, electrification journeys like my own can be challenging. Figuring out which machines to purchase, finding contractors, and paying for the up-front cost of new appliances can be a hefty burden In my case, the HVAC technician was extremely difficult to pin down, delaying the installation of my heat pumps by weeks. This is a common experience, because there’s a shortage of skilled workers. Other homeowners have found that some contractors, unfamiliar with modern technology, keep recommending a gas furnace even when a client says they don’t want one. Clearly, we have a ways to go on building up the electrification workforce, and unfortunately, that wasn’t a big focus of the IRA funding.

Although the IRA helps, swapping out all these electric machines is expensive. We cannot just electrify wealthier households and leave disadvantaged communities hooked on fossil gas, saddled with costs that will only grow as more people exit the system. The law continues the pattern of relying heavily on tax credits to support clean tech, including EVs and solar panels. Waiting a year-plus to get money back is a tough proposition for many households, even before you consider just how complicated filing taxes is. As a result, most solar adoption has happened in wealthier households.

Over time, such technology should get cheaper. The IRA includes about $50 billion in funding for low-income and disadvantaged communities. Most households will also soon be able to receive upwards of $10,000 to make climate-friendly installations, including insulation and induction stoves. Plus there’s an additional $7 billion for low-income households looking to install solar panels. The brilliance of the IRA is that the law is designed to build up clean manufacturing here in the United States, which will spur innovation and lower costs.

A year out, the IRA is like an infant that has just become a toddler: It’s still too early to tell exactly how it will grow up, but the signs, so far, are promising. We can see that in the numbers—there are now more EVs and more solar panels and, yes, many more heat pumps. But the law is so much

bigger than consumer incentives for clean machines. It’s also reshaping the economy, generating more than 170,000 new jobs and $278 billion in new investments in battery manufacturing, wind-turbine factories, and solar manufacturing plants. In another decade, the IRA—although not perfect— may prove to be an inflection point in America’s relationship with fossil fuels. Thanks to this law, millions more people will have electrified their homes, and our old relationship with the gas company will feel like a distant, bad memory. We’ll look back and wonder: Why did we put up with them for so long?

Leah C. Stokes is the Anton Vonk Associate Professor at UC Santa Barbara, where she studies climate and energy politics. She is a senior adviser at the nonprofit Rewiring America, and the author of Short Circuiting Policy

August 17, 2023

We need to tell everyone that houses are not zero carbon built from wooden sticks, steel nails, concrete, rebar, asphalt or steel shingle or clay shingles made from clay and cured in a natural gas furnace.

Furniture is not zero carbon no matter how it is manufactured.

Every body is ~18% carbon.

Food we eat is made using carbon to plant, grow and harvest the food and from carbon dioxide in the air.

Clothes are made using carbon in the energy source to manufacture clothes that are mostly from oil.

Cremation uses natural gas, or burial in a pine box, bodies decompose and release their carbon.

Carbon is the central atom for all life on earth, plants, animals, people, bacteria and viruses.

There is no other atom that is so central to life or living tissue.

In the beginning of planet Earth, carbon in the form of CO2 was about 100% of the atmosphere, the free oxygen atom was not there, but bound up with carbon as CO2. Gradually anerobic bacteria evolved, followed by the many species of plants to break down CO2 and provide us with the O2 for animal life. Life today is in a quasi stable state of reducing species, plants and bacteria, in symbiotic relationship with oxidizing species, ie animals.

Getting rid of carbon dioxide is a non-starter because of bigger and more powerful forces in nature driven by a combination of chemistry and biology.

I am disappointed that a university professor could be so mistaken and will no doubt leave generations of mistaken and delusioned students in her wake. ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Comment by Geert de Vries, mechanical engineer, physicist –South AfricaAugust 19, 2023

She is nearly there in her quest to break up with fossil fuels. Only needs to still remove some hydrocarbon-based items, like plastic insides (doorpanels, seats, dash …) and outsides (body panels, lights, window seals, …) of her EV including plastic connector at the end of her charging cable, plastic housing and internal components of her EV charger, including the wiring’s metal parts fabricated with fossil-driven machinery, including the copper cores itself since copper refining generates it own weight in CO2. All this has to go to stop her massive CO2 contribution to the atmosphere.

Also her EV’s tyres vulcanised with fossil heat, and not forget to scrape off the EV’s synthetics-based protective layers like paint and anti-rust. Remove also all plastic in- and outsides of her EV battery, there is a lot of it in there. Another major CO2 emitter to remove is the Lithium in the batteries because it is mined and transported with CO2 spewing fossil-driven means.

Next all plastic items in the house, all synthetic textiles but also cotton picked by fossil-fuel driven cotton pickers and wool sheared and woven with fossil-driven tools and machinery, jerseys self-knitted from hand-spun and hand-sheared wool is fine and can stay. After all, that is how people always did it, before 1800.

But all lubricants, all toiletry, health and medicine products, all made of hydrocarbons, have to go.

Followed by containers, buckets and other plastic kitchen items. All food prepared with fossil fuels be dropped. Including fossil-fuel-transported natural foods from, say, farmers markets. To be replaced by either not eating or organic self-gardening.

Using water arriving through plastic piping, pumped by fossil-electric motor-pump sets must be stopped. Fetch water from clean distant streams, but not with fossil fuel-intensive plastic or metal.containers, rather use natural items like calabash and coconut shells, or handwoven linnen bags.

Next candidates for removal are foam mattresses, furniture upholstery and floor coverings that contain synthetics made from hydrocarbons. Since all of them do, the remodelled house shall be rid of these.

And while remodelling her US house, she should also remove all outside and even inside walls made of wood dried in gigantic fossil-fuelled bulk wood dryers, or made of fossil heat-intensive fiber cement or hydrocarbonbased vinyls. Not forgetting all brickwork since bricks are baked with fossil heat. And remove glass windows since glass is made with fossil-fuelled ovens and liquid tin baths. There is always mud and dung to replace those obnoxious hydrocarbon-based products.

Lastly do away with cellphones, they are full of stuff that made CO2 somewhere. And spectacle frames and their lenses, whether glass or polycarbonate. If at all possible remove knee, hip and eye implants made with fossil-based synthetics. Titanium tooth implants too. Titanium has a high melting point and needs huge energy to refine and worse, all items made from it are fabricated with fossil-driven machinery. CO2-wise, titanium is terrible.

Oh, forgot, also remove shoes made of plastic, or leather cured with hydrocarbon-based acids and other dreadful chemicals. And yes, the plastic-housed router for internet has to go as well, not to mention the plastic keyboard of her pc.

The climate and environment today are very good, much better than 70 to 120 years ago. In some regions, human impact on the environment can be improved and wildlife habitat expanded. Cities can be redesigned so as to minimze wasteful transportation.

A modern very clean coal fired electric generating plant in Europe.

The graph on the next page shows the small amount of energy from natural gas that is used in residences. See the top pink box. Professor Stokes’ removing her gas appliences is in every sense meaningless for controling global warming and having a cleaner environment. This article is to satisfy herself, impress her academic peers, influence her students, and impress readers of The Atlantic Magazine. Kenneth Kok, nuclear engineer points out that Professor Stokes doesn’t realize that by switching from gas to electric appliances, she uses more, not less gas. It takes more gas to generate electricity and send it to her home than her gas appliances used. Variable, unreliable, not always available wind and solar generated electricity won’t be good for her modern life style either.

There are many similar academics. The American and European education systems suffers from lack of good teaching. John Shanahan, civil engineer.

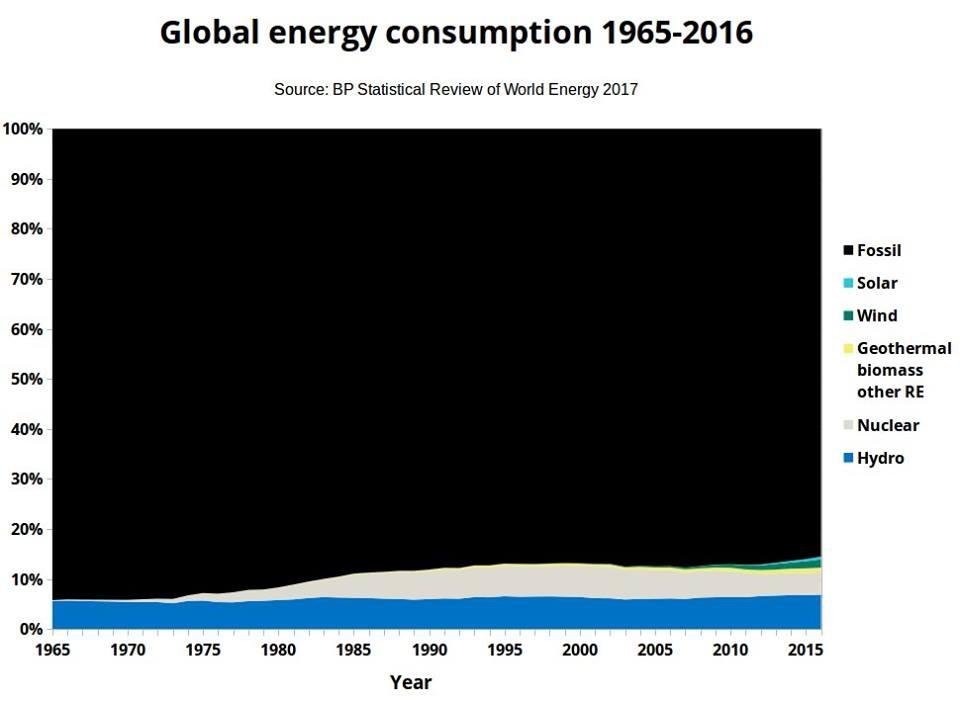

The graph below shows how fossil fuels have created the wonderfull modern world in the last two hundred years. Everything in our lives owes a tremendous debt to fossil fuels: garbage collection and recycling services, wind and solar electric generating facilities, ground, air, and ocean transportation, vacations, high rise buildings and elevators, Internet, smart phones, entertainment, universities where professors like Leah Stokes lecture, grade schools and high schools that prepare students to listen passively or enthusiastically to professors like Leah Stokes. The energy used from fossil fuels, black area below, is not going away any time soon.