1 minute read

GOOD

“Why are all the men in the other room?” my sister asks. Too young to know that we don’t pass on invitations to them. Because it’s better this way. Just the spices, our Ma, her daughters, and their daughters. To sit in the kitchen is to endure that sweet warmth, to know the fiery ways a woman labors.

It is not that men don’t labor, or that we couldn’t use their help in this room. But, it’s the stove’s warmth that melts our confessions and shakes them loose. It’s an invite from the oil crackling in that cast iron skillet that seems to target daughters. This is why it takes nine women to pass the spices.

My aunt secretly shakes more cinnamon into the applesauce. She swears by extra spices and epidurals during labor. She describes the differences between the births of her two daughters, Explaining what it is like in that fluorescent hospital room. That cold room where one becomes a mother seems so uninviting, so different from the ones we’re in when our mothers invite us to know them. To warm up to their rages. To hear of their discarded passions, while warming the green beans is a different type of vulnerability. To be critiqued in your choice of spices while hearing descriptions of teenage romance takes the most feminine of invitations. This is not dinner table talk, what it is like to go into labor, but there is no doubt that its place is in the room where mothers recruit their daughters.

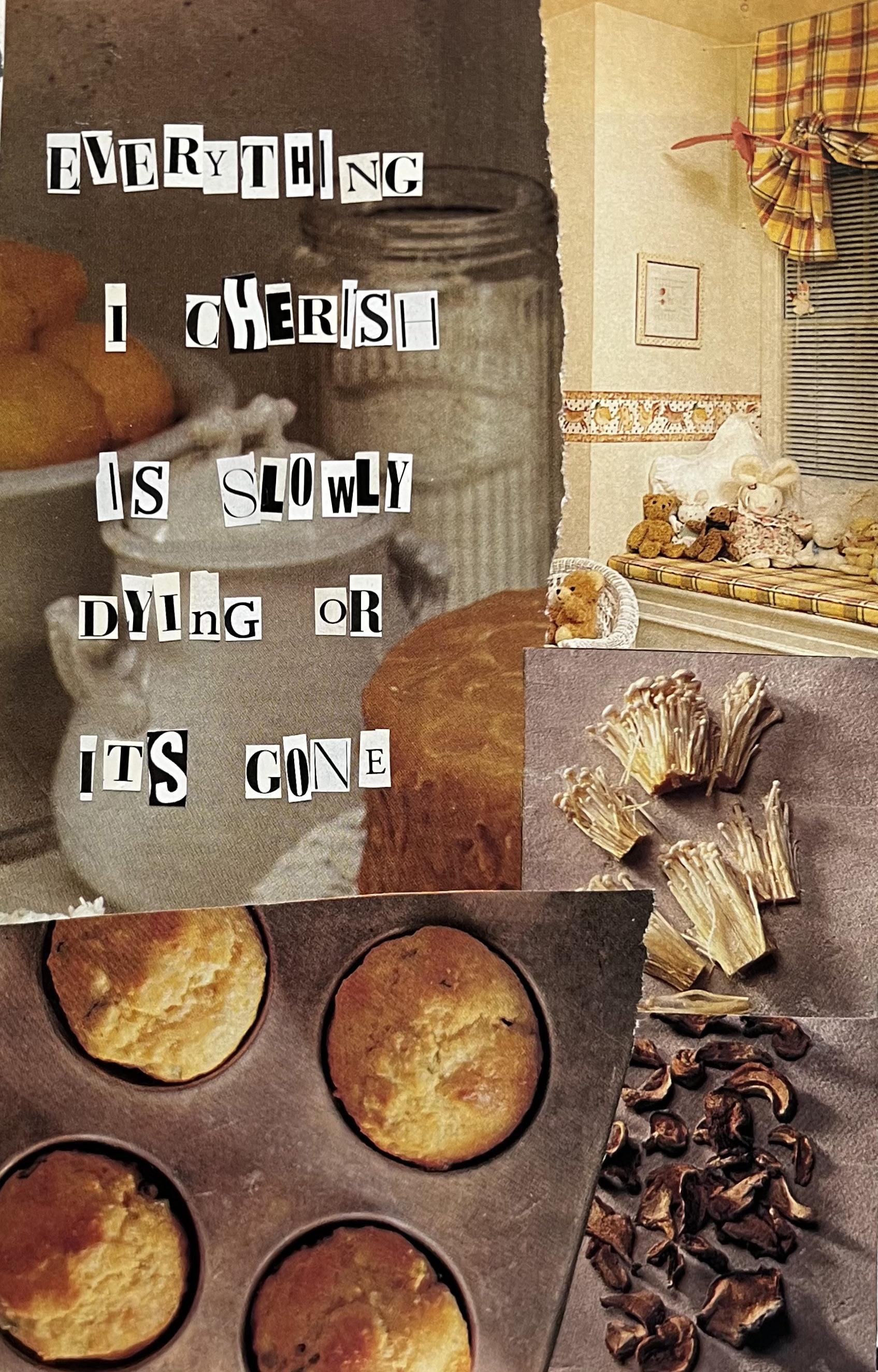

and it is cold like the floorboards in a home where the quiet swells and burrows into skin. the hydrangeas gave no sign that they would die. the cicadas have sung themselves to shells. summer is gone– don’t you hear the bombs? these clothes have lost the weight of you that filled them.

there is more grief than there is of me. I am fatal, a pilot rowing through zodiacs and the black. sifting through sand and salt. wounded in the eye. this atmosphere is godless and on earth it rains for us.