small specialty-focused hospital with a mission to serve the poor and afflicted citizens of

Laurie Levin is a Harvard

Manhattan with vision and hearing loss. Two centuries later, their dream has evolved into

University/UCLA-trained

one of the world’s leading centers for ophthalmology (EYE) and otolaryngology (ENT).

anthropologist and author who

Nevertheless, the same vision, mission, and values of its founders, Edward Delafield, MD,

specializes in non-fiction books

and John Kearny Rodgers, MD, still permeate the entire institution.

and institutional histories.

Dr. James C. Tsai

www.laurielevin.net

President, New York Eye and Ear Infirmary of Mount Sinai from the Foreword

1820

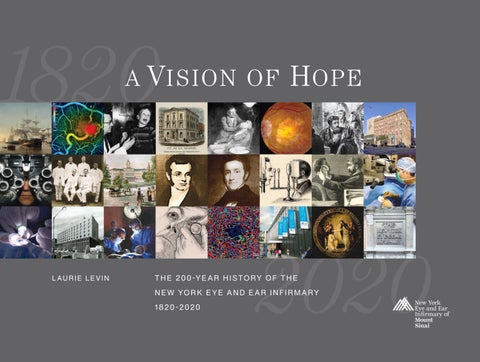

a V i s ion of

The esprit de corps of the NEW YORK EYE AND EAR INFIRMARY is legendary, based on vibrant fellowship, shared pride, and a deep sense of belonging. To be sure, bonds such these are rarely found on any standard job description. But ask insiders, especially those who have been there awhile, and they easily spell out what makes NYEE unique.

H ope

“The Infirmary has always been characterized by camaraderie and collegiality that you don’t find in other hospitals and academic departments. Ever since I started here as a resident in 1989, the rapport between physicians, nurses and staff has always made this a wonderful place to work, teach, and care for patients.”

9.281”

Dr. Paul Sidoti Professor and Site Chair for the Department of Ophthalmology “In a nutshell, the Infirmary’s mission gets into your blood: groundbreaking research and teaching excellence, which translates into superb patient care, all make me extremely proud to be part of its 200-year history.”

THIS BOOK ... honors the thousands of men and women of the Infirmary over the past 200 years who have dedicated their lives to repair and enhance the lives of so many grateful

L AU R I E L E V I N

ISBN 978-0-578-61431-1 ISBN 978-0-578-61431-1

volume of stories and facts, highlighting our first 200 years.

ScD (Hon), FACS, FASRS, CRA Surgeon Director and Retinal Service Chief, New York Eye and Ear Infirmary of Mount Sinai

Larry Zempel, Zempelworks.com

12.312 .125

9 780578 614311

Victoria Toro 45-year staffer in the Infirmary’s Social Work Department

Printed in USA

from the Introduction

3.875

2020

T H E 20 0 -Y E A R H I S TO RY O F T H E 1820 -2020

Dr. Richard B. Rosen Book and cover design by

“NYEE touches peoples’ lives every day, in the best ways possible—but it’s really a two-way street. My patients have impacted my life, put everything into perspective and taught me the true meaning of resilience.”

N E W YO R K E Y E A N D E A R I N F I R M A RY

90000>

patients. In the spring of 2020, we look forward to sharing this lusciously illustrated family

Arthur Tortorelli Technical Director at the Jorge N. Buxton, MD, Microsurgical Education Center since 1977

.75

12.312

3.875 .125

9.281”

NYEE 200

TWO HUNDRED YEARS AGO, two visionary physicians dared to dream—founding a

ABOUT THE AUTHOR