50TH ANNIVERSARY

COLLEGE OF FOOD INNOVATION & TECHNOLOGY

INNOVATION & TECHNOLOGY

Fifty years redefining the nature

and future of food.

Fifty years redefining the nature and future of food.

50TH ANNIVERSARY COLLEGE OF FOOD INNOVATION & TECHNOLOGY

CFIT 50

CFIT 50

FOOD & TECHNOLOGY

50TH COLLEGE

FALL 2023

CONNECTIONS

MEANINGFUL CONNECTIONS

One of the great things about the JWU community is that its members −students, faculty, alumni and sta −stay connected and help one another whenever they can.

One of the great things about the JWU community is that its members −students, faculty, alumni and sta −stay connected and help one another whenever they can.

As a JWU graduate, you’re in a unique position to assist your fellow alumni, today’s students, professors and, ultimately, the university in many ways:

•Mentoring current students

As a JWU graduate, you’re in a unique position to assist your fellow alumni, today’s students, professors and, ultimately, the university in many ways:

•Speaking to students on campus

•Mentoring current students

•Providing professional development to alumni

•Speaking to students on campus

•Assisting with university fundraising e orts

•Providing professional development to alumni

•Assisting with university fundraising e orts

Let us know how you’d like to be involved! Update your JWU Alumni

Connect profile to become a mentor, or share your involvement preferences. Scan the QR code below to begin!

Let us know how you’d like to be involved! Update your JWU Alumni

Connect profile to become a mentor, or share your involvement preferences. Scan the QR code below to begin!

Visit jwuconnect.com

Visit jwuconnect.com

MEANINGFUL

JWU MAGAZINE SPRING 2023

2

This special issue celebrates the 50th anniversary of JWU’s College of Food Innovation & Technology and the College of Hospitality Management. We highlight the evolution of both colleges and will feature our traditional sections in our fall magazine.

2 MISE EN PLACE

The College of Food Innovation & Technology celebrates a golden anniversary as it looks to change the world with future-forward programs.

8

TRUE NORTH

Since its 1971 founding, the College of Hospitality Management has evolved from training travel agents to inspiring agents of change.

16

INDELIBLE COMMITMENT

Kitchen ink is so ubiquitous it can look like a job requirement. For chefs who create ephemeral meals the skin is a lasting canvas.

Cover: Fifty years of progress at CFIT Photos by Mike Cohea & the JWU Archive

16 8

Mise En Place

The College of Food Innovation & Technology celebrates a golden anniversary with future-forward curricula aimed at changing the world with food

By Denise Dowling

“After being freed from the concentration camp, I decided I was going to be a cook. I never wanted to be hungry again as long as I lived.” — Robert “Moshe” Nograd ’99 Hon.

Nograd was the kind of teacher who inspired “Yes, chef” devotion. The late culinary dean emeritus was a survivor of Auschwitz who understood — more than most — that nourishment is literal and metaphorical.

As the College of Food Innovation & Technology (CFIT) celebrates its 50th anniversary this year, Nograd, who was appointed dean in 1987, would be proud of its evolution as an institution dedicated to sustaining the world through food.

One of Moshe’s proteges from the ’70s is former associate professor Linda Kender ’76, ’97 M.A.T., who retired in 2020. She recalls the early days in a Culinary School Stories podcast hosted by former North Miami Campus Culinary Chair Colin Roche, Ph.D. “When I enrolled in 1974, there were maybe a dozen females in the entire school and the only female chef around was Julia Child,” says Kender. “The first thing Culinary Director Franz Lamoine said was, ‘You’re welcome to come to school here but there’s no such thing as a female chef.’

“We didn’t really have textbooks then, they were more like pamphlets,” she adds. “The culinary labs actually fed the students; when kitchens ran out of food your table was stuck with chicken liver omelets! Chef [Edward] Flattery taught garde manger and everyone feared him,” says

Reality Bites

Back-of-the-house, sharp knives are at play, orders pile at a staccato pace and burning is learning. While some industry members blame sta ng shortages on a trend of people motivated by fame rather than a passion for cooking, JWU alumni and faculty agree there is little room for attitude — or Kardashian egos — when collaboration is critical.

“I grew up watching Julia Child,” Emeril Lagasse ’78, ’90 Hon., told Eater. “When I was approached to be on the Food Network it was like a dream. Okay, there’s going to be a network about cooking and shopping and wine, 24 hours a day?

Kender. “If you didn’t learn your recipes you were out. He would line us up like soldiers and each student had to recite the recipe for chicken galantine: ‘Okay, you go, first three ingredients, okay you, next three.’ It was learning by intimidation.”

While that teaching method may be extinct, lab rules remain strict — a rehearsal for back-of-the-house pressure cookers. “If you miss more than one class, you’re done and have to take the class over again,” Jorge de la Torre, a culinary dean of the Denver Campus for nearly two decades, told Westword magazine. “We don’t allow any body piercings or facial hair, with the exception of a mustache; no makeup or jewelry; and uniforms have to be perfectly ironed. We try to teach people that there are no excuses — that you have to come to class prepared and have your mise en place. We teach, but don’t coddle, and we hold very high standards … I tell my students that the restaurant is about the only place where you let a perfect stranger give you something to put in your mouth — and those customers are fully trusting that you’re clean, sanitary and ethical.”

The kitchen symphony requires precise teamwork — camaraderie that fosters a unique student-mentor bond. “I used to ask my students, ‘What was the best advice you ever received?’” Kender recalls.

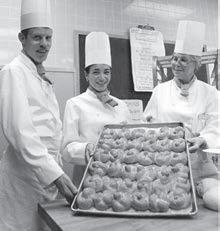

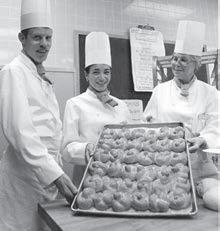

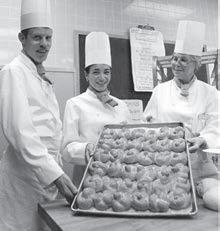

Kender and Moshe Nograd

Come on, that’s, like, impossible.” The programs jettisoned Lagasse and others into household names; however, fame was a byproduct, not the kite they chased. “I’m involved in a lot of aspects of culinary education, from college to high school,” he adds. “I want to be with people who want to be in the business — not so much to be on TV or have their face on a box. This is a crazy business, not a 9-5 job. When people come to work with us, it’s like, ‘Look, if you want to be famous, then you’re in the wrong place. If you want to learn how to cook or be a restaurateur, then you’re in the right place.’ I can teach really anybody how to cook if they have the passion and desire to learn. If they have that, then it’s much easier for me to teach them than pulling them up the mountain.”

2 Spring 2023

Linda

“For me it was ‘Shut up and show me.’ The best advice I gave? Find a mentor. I found mine in Moshe Nograd. We spoke every morning until he became dean emeritus. After he left Moshe would still call me up and say, ‘Linda, give me the advice du jour.’ ”

Kender’s food safety expertise was in demand when restaurants were shuttered by COVID-19 restrictions — and CFIT’s interdisciplinary pedagogy was an advantage. Legal compliance, cost control, negotiation and risk management proved critical for chefs and restaurateurs as they jockeyed for relief funds, volleyed with landlords and implemented stringent food safety protocols.

insecurity. It is no coincidence that last fall the White House hosted its first Conference on Hunger, Nutrition and Health in 50 years, celebrating a food-focused policy platform designed to change the way that people eat. “Food is a practical tool to make the world better,” says CFIT Dean Jason Evans, Ph.D. “If you change the way food makes its way through the system from start to finish, you really can change the world.”

AGENTS OF CHANGE

The pandemic also highlighted nutrition’s role in disease management and prevention — and the dire need to address food

FIT FOR A QUEEN CITY

It was a win-win. In 2001, the city of Charlotte was eager to revitalize an uptown neighborhood and boost its economy. At the time, JWU operated campuses in Charleston, South Carolina, and Norfolk, Virginia, to train hospitality staff for cruise ships and U.S. Navy vessels visiting those ports. Both campuses required costly infrastructure work, and JWU was searching for land near Charleston’s waterfront to expand the campus. It was then that a Bank of America executive made a play to woo JWU to Charlotte.

Then-JWU President Jack Yena met with representatives from Charlotte, the state of North Carolina, Bank of America (BOA), and Compass Group, among others. “They made [Yena] “an offer he couldn’t refuse,” recalls Jerry Lanuzza ’91, dean of the culinary program at JWU Charlotte. The offer included a deal on land in a BOA uptown development and hotel ownership. By 2004, the campus was ready to launch and JWU later shuttered its Charleston and Norfolk campuses.

Evans continues to expand the depth and breadth of CFIT’s interdisciplinary programming, which spans Johnson & Wales’ seven colleges. Arts & Sciences, for example, o ers such courses as Food Writing and the Politics of Food, Human Security &

crowd to more independently-owned restaurants offering modern cuisine based on local ingredients. And the transformation transcends restaurant walls: Faculty are members of Piedmont Culinary Guild, which unites culinary operators and

farmers, and Optimist Food Hall boasts a culinary incubator plus many alumni-helmed small restaurants. Even NASCAR fans are more discerning about how they refuel.

Lanuzza, who has worked for JWU since 1994, was part of the opening team and its first culinary department chair: “When we’re out to eat and people learn we work for Johnson & Wales they’ll say, ‘You guys have had such an impact on the city!’ My standard answer is ‘You’re welcome!’ ” Charlotte , ranked the eighthfastest growing city in the country, is skewing younger. “Many graduates stay in the city,” he says. “The ones from 10 years ago are now executive chefs and restaurant owners so their impact is really being felt.” Local palates have become more daring as dining options have grown from chain restaurants and steakhouses catering to the business

Culinary Nutrition and Applied Food Science specialties (plus culinary electives available to entrepreneurship students) have fostered partnerships with the North Carolina Research Campus and the NC Food Innovation Lab. Students teach Sanger Heart Institute patients how to modify recipes to make them heart-healthy; they create videos and lead demos for a nutrition program on the economic value of healthy eating and how to stretch one ingredient for multiple meals. JWU also co-sponsors the city’s BayHaven Food and Wine Festival, which “celebrates African-American foodways and the industry makers who make them possible.”

The campus has expanded to offer more than 20 bachelor degree programs, from accounting to psychology. According to Lanuzza, Charlotte’s state-of-the-art facilities, curricula and faculty offer a distinctive education: “I don’t have chef instructors, I have professors who used to be chefs,” he explains. “There is a difference. We invest in making them better teachers and developing curriculum scaffolding and sequencing.”

4 Spring 2023

Jerry Lanuzza

L-R: Branden Lewis with Jason Evans

Social Justice. Combined with CFIT’s forward-looking specialties such as Culinary Sustainability, graduates are prepped for culinary adjacent roles beyond a restaurant kitchen. They might manage food supply chains, draft public health regulations, create plant-based cuisine products or found a cooking school to stem food insecurity.

“This kind of work on real-world issues distinguishes CFIT from other schools,” says Assistant Dean of Culinary Relations & Special Projects Thomas J. Delle Donne, ’04, ’07 M.A.T. “We give them the research and the tools to really think on their feet, to be problem solvers and change agents.”

which works with school districts to fundamentally change what students eat.”

This holistic approach is symbiotic with the College of Health & Wellness (COHW), which infuses programs with a culinary flavor. “JWU can appeal to anyone interested in the nexus between food and nutrition,” says Evans. A Performance Cuisine class, for example, embodies that duality: Students employ their knowledge of nutrition, biochemistry, anatomy and physiology to develop individual assessments and menus for di erent types of athletes.

“Our students come in with this genuine belief that they can save the world,” says associate professor Branden Lewis, Ed.D., ’04, ’06 MBA. “They feel like the planet is broken and they can fix it.” Lewis spearheaded the Sustainable Food Systems bachelor’s degree, which expanded on the Wellness & Sustainability concentration added in 2011. It is designed to prepare students to understand the social and moral implications of our food systems. In one of the major’s core courses, Sustainability and the Culinary Kitchen, students tour farms and board fishing vessels to learn the role of community and purveyor partnerships.

CFIT continues to buttress programming around degrees in Culinary Nutrition, Dietetics and Applied Nutrition, and Culinary Science, which rolled out in

In COHW’s new Exercise and Sports Science Lab, student and faculty clinicians and dietitians utilize data to individualize fitness, therapy and nutrition plans for injury prevention, maximum recovery and performance, while researchers can tailor their discoveries to the fields of health and wellness.

THE NEXT HALF-CENTURY

“Technical skill building is still essential to our model,” says Evans. “As a comprehensive university, JWU has the flexibility to support that training with our interdisciplinary approach. Our labs incorporate richer stories around the ingredients and their historical and anthropological culture. “A big priority moving toward our next 50 years is increasing opportunities students have after graduation,” he adds. Some will go into traditional cooking, but CFIT is also evolving into policy and food management. For example, a degree partnership with the Roger Williams University School of Law speaks to food systems in law and policy. Culinary Sustainability, meanwhile, concerns big picture concepts such as how the food system functions and the implications for ecology and community.

2016–17. Food as medicine programs o er doctors-intraining opportunities to learn about food’s health benefits alongside culinary students. JWU hosts Tulane University medical students for a month while the Nutrition Club works with aspiring physicians from Brown University.

“I want to ensure that food and health connection is also apparent in K–12 and students have experience in institutional dining — the pillar where lifelong dining habits are built,” says Evans. “We’re connecting students to opportunities with nonprofits like Brigaid,

Entrepreneurship opportunities since the pandemic have multiplied and become more accessible, from food trucks to cloud kitchens and food distribution channels. CFIT’s Ecolab Center engenders full-scale product development, including the regulatory approval process. Competitions and projects o er safe spaces for students to build an entrepreneurial skill set. “They are honing and launching skills that go far beyond what students might get in traditional labs or classrooms,” says Evans. “It’s a safe space to take risks — and to fail. What we’re doing and will continue to do is in recognition of the nobility of food, with broad programming plus rich content and context to spark new interest in food as a lifelong career.” JWU

To support the College of Food Innovation & Technology visit alumni.jwu.edu/cfit50

Bears & Blizzards

Strolling yearbook lane — with black and whites of the days when ice sculpture was sport and gelatin molds were art — makes us wish we were there: hunkering in the dorms and heating bathwater in cooking pots during the Blizzard of ’78; road tripping to D.C. to provide food service for President Reagan’s inauguration; and elevated fun at the Vail Campus in Colorado.

The “Garnish Your Degree” program, o ered in the ’90s, was an accelerated associate degree program in culinary arts for college graduates. With campus at 8,150- feet altitude, so students commuted via chairlift to kitchens atop Vail Mountain. If they missed the last chairlift of the day after “scholastic” wine tastings, classmates might have to be snowmobiled back to base. Jenna Johansen ’98 (whose ex-husband and former Denver Campus Professor Mark DeNittis proposed with a salami ring) recalls watching a family of bears traverse the grass slopes below as students ascended the lift to class. That afternoon a thunderstorm pelted the mountain, forcing the lifts to close. Forty students, certain they would meet bears, hustled down the mountain on foot, “wet boxes of cake in hand, chef coats on, soaked from head to toe in freezing Vail rain, and headed straight to our restaurant jobs.”

5 www.jwu.edu

{ {

Since its inception half a century ago, CFIT has continued to evolve and redefine both the nature and meaning of food.

From cutting-edge cuisine to advanced nutrition, food management, dietetics, culinary nutrition, science and sustainability, to the politics of food, human security and social justice, CFIT has led the way.

This vision has influenced the scope and future of food, expanding its power to improve our lives in profound ways.

Congratulations on becoming the thought leader in the culinary field that you are today.

Happy anniversary CFIT. Well done.

6 Spring 2023

8 Spring 2023

Since its founding in 1971, the College of Hospitality Management has evolved from training travel agents to inspiring agents of change.

By Sam Eifling

TRUE NORTH

COHM students put their training into practice by running the JWU-owned Doubletree Hotel on the Charlotte Campus.

9 www.jwu.edu

Photos by Mike Cohea and the JWU Archives

CURRICULUM THAT KEEPS STUDENTS ONE STEP AHEAD OF INDUSTRY NEEDS.

AS THE COLLEGE OF HOSPITALITY MANAGEMENT passes a landmark birthday — 50 years of educating future hospitality professionals — it’s worth noting what has changed, and what has not, for the students of Johnson & Wales. The changes for students studying to run hotels and organize travel mirror the broader evolutions in those fields. Some shifts in hindsight seem positively tectonic: the ways technology has transformed what it means to be a travel agent or the revolutions in how Americans eat, drink and gather.

Other changes happened more slowly. When she began teaching at JWU in the late ’70s, Caroline Cooper, Ed.D., made a point each year of asking first-year students their earliest memory of eating in a restaurant. Many students had fresh memories of dining out for the first time in their late teens.

Restaurants simply weren’t a place where people went as often, and when they went, they were less apt to bring kids. It took roughly a decade before students’ standard answer was that their first time in a restaurant was too early for them to recall. “I’d always get around to the question,” Cooper, now retired, says today. “Because I’m just fascinated.”

From the earliest days at the college, the pedagogy always flowed from real-world experience. It’s not simply interesting to consider a time before

10 Spring 2023

children in restaurants; rather, that sort of data point has all sorts of implications for curriculum. Who the customers are at a restaurant, hotel, tour business or event space will inform successful strategies. Hospitality students want to provide them with an amazing experience, because it was probably some experience, at some point in their life, that drew them to pursue a career in hospitality in the first place.

“Hospitality students generally have empathy — they’re a happier group to begin with,” Cooper says. “They want to enjoy life. They wouldn’t be in this field if they didn’t want to impart good things. It never has been a field where a parent will say, ‘I want you to go into the hotel business.’ Or, ‘I want you to go into travel and tourism.’ A Johnson & Wales student knew they wanted to be in the field, day one.”

At that time Johnson & Wales had three divisions: the business college, the culinary college, and continuing education. Hospitality programs were nested inside the business college. It was the late Peter Van Kleeck, a Cornell University graduate, who organized hospitality into four constituent focuses: hotel management, food service management, travel and tourism, and recreation and leisure event management. True to Gaebe and Triangelo’s vision of a career-focused institution, the school was known for placing students in practical settings as soon as possible and attracted the sorts of students who would work a part-time job during the year.

JWU EXISTED long before the hospitality program, but the push by then-president Morris Gaebe ’98 Hon., the late JWU chancellor emeritus who died in 2016 at the age of 96, was a defining event in the history of the school. In 1947, along with Edward Triangelo, Gaebe bought the 33-year-old business college from its founders, Gertrude I. Johnson and Mary T. Wales. To keep enrollment up, the entrepreneurs scoured want ads, honing their curriculum to keep their students one step ahead of industry needs. Their early ’70s bet on a hospitality program proved successful. The inaugural class numbered 141 at their enrollment in 1973. Ten years later, enrollment topped 3,000.

(Students in the ’80s, for instance, did practicum work at a university-owned and-run hotel — a tradition that continues today on the Charlotte Campus, home to the JWU-owned Doubletree Hotel.) In turn, the students never were too keen on instructors who lacked industry experience.

Johnson & Wales College became Johnson & Wales University in 1988 and gained regional accreditation in 1993 from the New England Commission of Higher Education. It was in the early ’90s as well that the hospitality division — having outgrown the other business college divisions combined — split into its own college, a transition overseen by Irving Schneider as dean before he

“HOSPITALITY STUDENTS GENERALLY HAVE EMPATHY, THEY’RE A HAPPIER GROUP TO BEGIN WITH,” COOPER SAYS. “THEY WANT TO ENJOY LIFE.”

Above – Images of the program from the ’80s & ’90s and an early picture of the Harbor View complex.

Below (L-R) – Debra Cormier ’11 MBA, Courtney Dial ’11, and Ann Dwyer ’07, at the SEEM Conference Alumni Panel.

Below right – Charlotte students undergo hospitality training.

11 www.jwu.edu

“TRAVEL IS FATAL TO BIGOTRY AND PREJUDICE.”

became president of the Providence Campus. Cooper was assistant dean at the time, and took over as dean in 1995. By the time of her retirement in 2012, the college was drawing plaudits as a national top-10 hospitality program, recognition that boosted student recruitment and placement.

OVER THOSE YEARS, it wasn’t just the restaurant-going habits of incoming students that shifted. The travel industry was in full upheaval, technologically and culturally. In the ’70s and ’80s, JWU got a huge boost from — of all things — the cruiseliner sitcom “The Love Boat.” Campy, flirty, packed with guest stars, the rom-com made travel look like a bu et of poolside fun and black-tie dinners. Applications to the college skyrocketed. It didn’t hurt, too, that airline deregulation after 1978 made air travel cheaper and more accessible than ever before.

In those days the typical graduate was probably working toward becoming a travel agent, or once those jobs began receding, a tourism o cial or director. The college continued to innovate in nudging students into the world to explore and learn. In 1990 the Los Angeles Times reported on the e orts of undercover JWU students who sussed out the travel-worthiness of major destinations. They had just vetted Atlantic City, New Jersey, where four faculty advisors oversaw 13 students who logged their visits to some 700 di erent establishments and attractions in the tourism mecca, turning up several service problems along the way. Paul Lacroix, then-chair of the Travel & Tourism Department, told the Times: “The 1980s was a

marketing era. Everyone went marketing. Now we have the customers, and my question to students is, ‘What do we do with them?’ I think the ’90s is going to be an era of service. I think it’s a very natural follow-up to what has happened in the ’80s.”

JWU’s International Travel & Tourism Studies Chair Michael Sabitoni ’82, ’92 M.S. joined the college in 1992 as the director of travel internships, in the heyday of corporate travel agencies. The program centered on a working travel agency JWU owned, and was designed to impart the basic skills of the trade — booking a flight, car or hotel. “Those really were the days of living la vida loca for travel agents,” Sabitoni said. “That’s where everyone would go for leisure travel, corporate travel.”

Internships thrust students into the working world, to acclimate them to the ticklish business of interacting with real travelers. In the early ’90s, a passenger arriving at the airport outside Providence would see, as they descended the escalator, an information booth bearing a JWU logo, sta ed by students 6 a.m. to 11 p.m., 361 days a year. If that traveler were in town for a trade show, they might also encounter working students at the convention center; if they were inclined to visit the Rhode Island State House, they’d bump into students working there as well, walking grade schoolers through portrait galleries.

“Johnson & Wales provided me the autonomy to really be creative to deliver based on our roots,” Sabitoni says. “And that is experiential education. We evolved from owning our own hotels, travel agencies and our retail store. That spirit is still alive today in our curriculum, which has always been the bedrock of the College of Hospitality Management.”

WITHIN A DECADE, the web had made it a snap for anyone with a laptop to essentially become their own travel agent. And as the

12 Spring 2023

Mark Twain

Left – A familiarization tour to India

Above – COHM grad Yijie Bao ’22

Right page – A FAM Tour to Ecuador led by professor Ti any Rhodes.

methods by which people arranged travel evolved, so did their expectations about what travel entailed. Once the sort of rare, jubilant event that perhaps restaurant meals had been, air travel brought a host of perils as it got cheaper, threatening local cultures, economies and ecosystems. Even teenagers came to realize that the sorts of vacations their parents or grandparents may have enjoyed in the “Love Boat” era needed to be reimagined for a world that valued sustainability. Naturally, the college adapted as well, and now posits the potential of travel and tourism to bring positive change to developing destinations.

“The students today, that’s what they care about,” says Ti any Rhodes, an associate professor of Adventure & Sustainable Tourism. “They’re living in a world that they’re seeing get blown up. These students want to a ect good in the world. And maybe hospitality changed from a position of taking care of the customer first to a position of, let’s take care of the community. Let’s take care of all stakeholders.”

As Rhodes spoke, she was preparing to take a group of students on a Familiarization Tour. A ectionately known as FAM tours, the

journeys give students responsibility for organizing components of the group adventure — dining at sustainable restaurants, visiting economically and environmentally responsible attractions. They learn to manage risk, to evaluate where their money goes and how to communicate and guide a group. Rhodes was readying students for a FAM trip to Jordan (and encouraging them to download “Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade” onto their phones for the flight, to prepare for seeing Petra). Past destinations have included the likes of Zimbabwe, Morocco, Brazil, Argentina, Ecuador, South Africa, Cambodia, Vietnam and Thailand.

“Mark Twain said that travel is fatal to bigotry and prejudice,” Rhodes says. “I always tell my students that we actually are in an industry that can change the world. We are global. We have a lot of economic power.”

REACHED MORE THAN 30 years after he predicted in a national publication that the 1990s would be an era of better service, Paul Lacroix, who retired from JWU in 2001, looked back and o ered a reassessment. The 1990s did turn out to be an era of service, he says.

“WE ACTUALLY ARE IN AN INDUSTRY THAT CAN CHANGE THE WORLD. WE ARE GLOBAL. WE HAVE A LOT OF ECONOMIC POWER.”

13 www.jwu.edu

“INDUSTRYWIDE THERE’S A LOT OF OPTIMISM ABOUT WHERE WE’RE GOING.”

Hospitality at large competed fiercely over service quality, then became complacent, and then su ered a huge blow in the Great Recession. The 2010s were an era that launched budget airlines and budget hotels. Many hospitality colleges that had sprung up in the boom times shrank and shuttered, Lacroix says, because they were merely preparing students to be able to get a job. “Many of those schools that were training for jobs are now closed,” Lacroix says. “They did not survive. JWU, Cornell University, University of Houston — the classic ones, they survived. They were still training for careers.”

Hospitality education su ered another blow during the pandemic. Classes built to prepare students for hands-on experience had to move to Zoom. Nationwide, college enrollment fell. And the College of Hospitality Management continued to evolve as global events shook higher education as well as travel, dining, concerts and all the rest. The Sports, Entertainment, Event — Management (SEEM) students in particular have seen the demands on their specializations ratcheted all the higher.

14 Spring 2023

Above – Sheila C. Johnson ’14 Hon., founder and CEO of Salamander Hotels and Resorts, speaks to students and faculty about her experiences in the hospitality industry.

Below – Students attend lectures in the Providence SEEM Lab.

Right Page – Students at a Bigelow Tea Craft Cocktail Recipe Contest.

The prime goal for those entering that industry, says associate professor Lee A. Esckilsen, chair of the SEEM program, was to deliver an exceptional guest experience, whether they’re running a basketball franchise, managing a concert venue or planning a wedding. Now more physical concerns are equally important to consider. “How do you create an environment that keeps everyone safe and secure, without making people feel they’re watching an event with policemen standing over their shoulder?” Esckilsen says. “And how do you do this and still monetize it? It’s an interesting dynamic that we’re educating them for.”

Then again, the sorts of students drawn to those fields have always been detail-oriented, punctual and committed to maximizing the moment. If ESPN says the puck has to drop at 7:05, that’s when the hockey match must start. If Bruno Mars’ sound check takes longer than expected, you still have 18,000 fans on-hand who need pretzels and working water fountains. Students tend to arrive with a passion for sports or music, be that creative or analytical. It’s up to the instructors, Esckilsen says, to stoke those flames while also preparing them to manage an operation that has infinite possibilities bounded by firm constraints.

What’s true in events is the same, after all, of what’s true for a great restaurant meal, a life-changing trip or a blissed-out hotel stay. We’re all here for a good time. And then, we’re not. The pandemic underlined for Americans how fragile — and vital — restaurants, hotels, concerts and other events are if we take them for granted. Along with his colleagues, Bryan Lavin ’11 MBA, an associate professor in the International Travel & Tourism Studies Department, is training the new generation of students to see sustainability as a practice by which communities can invest in and protect their local businesses, to ensure they survive in lean times — no matter what the world throws at them.

“Tourism is back, travel numbers are massive, there’s a ton of demand out there and now there’s a huge need for trained professionals in the industry,” Lavin says. “The students who pushed through the pandemic are positioned to walk into excellent roles. Industrywide there’s a lot of optimism about where we’re going.”

COVID-19 accelerated many of the changes already afoot in the hospitality industry, forcing educators once again to grapple with how to prepare students for the preferences of a new generation.

The fundamentals, Sabitoni says, were already sound. The college has been preparing students for the tech-forward tastes of Millennial and Gen Z customers — people who expect great service, who want to access it via apps and screens, and who will let Tripadvisor, Yelp and Google know if they had a two-star experience. “Everyone’s a critic nowadays,” Sabitoni said. “We learned that even before the pandemic.”

More than ever, interactions with customers carry the potential for online blowback, of reputational damage to a business or brand. The savviest students, then, have to notice and keep pace with customers’ evolving tastes and expectations. For educators, that’s a two-way street. Sabitoni, for one, used to bring a case of bottled water to class for his students. Over the years he watched fewer and fewer students reach for the water, as they opted for reusable water bottles. Once again, students’ values were shifting, this time toward sustainability. The professor read the room and stopped bringing the plastic. Today when the professor lectures on sustainability, he has his own aluminum water bottle beside him. JWU

{To support the College of Hospitality Management visit giving.jwu.edu/ hospitality-management

15 www.jwu.edu

“If there is a universe that relies on rituals as heavily as that of cooking and food preparation, it’s probably tattoos,” according to a VICE article about the book “Knives & Ink: Chefs and the Stories Behind Their Tattoos.” “Getting something permanently inked on your body is a physical and emotional rite that spans from original idea to finished result — often with a lot of discomfort. The same can be said of what a good chef goes through each night in the kitchen.”

In an industry that celebrates noncomformity, tats are a trademark of individuality — and commitment. Chefs with ink above the shirtline or on the hands aren’t looking for a job in corporate America.

16 Spring 2023

a

GO AHEAD. SEE IF YOU CAN MATCH THE CHEFS TO THE TATTOOS. THE ANSWERS MAY SURPRISE YOU. 3 4 1 2 5 6 7 8 C D A B E F G H

T

oo s

ANSWERS: 1D) Alice Dewees Stone ’25

2E) Derek Wagner ’99 3A) Brianna Schmoyer ’24

4F) Catherine Doyle ’03

5B) Mario Limaduran ’14

6C) Kelly Dull ’08 7G) Lydon Olivares ’23

8H) Skyler Hanka ’15

8 Abbott Park Place, Providence, RI 02903

CHANGE SERVICE REQUESTED

Join the Mary & Gertrude Society and make a commitment to JWU’s legacy and future.

Together, we will power an educational experience rooted in excellence and driven by purpose. e Mary & Gertrude Society proudly recognizes the unwavering commitment of donors who have generously supported Johnson & Wales University for three or more consecutive years.

To learn more or join the Society before our fundraising year ends, visit giving.jwu.edu/maryandgertrude

JOIN JOHNSON & WALES IN CELEBRATING 50 YEARS OF CULINARY EXCELLENCE

For half a century, graduates of the College of Food Innovation & Technology (CFIT) at Johnson & Wales University have transformed the American food landscape as chefs, product developers, nutritionists, entrepreneurs and thought leaders.

To celebrate the university’s contributions to culinary education and culture, JWU will be hosting a 50th Anniversary Gala. Enjoy a night lled with renowned chefs, industry leaders, classic and re-envisioned recipes, and festive entertainment.

Save the date: September 29, 2023

For more details please head to alumni.jwu.edu/c t50

NONPROFIT ORG. U.S. POSTAGE PAID JOHNSON & WALES UNIVERSITY

Mary Wales

Gertrude Johnson