4 minute read

From Warfare to Woodworking

In the late 1800s, a doctor treating British troops in the Sudan wrote home to England that he was amazed at the severity of the wounds inflicted by the curved swords of the Mahdi’s soldiers.

The curvature of swords had been a matter for military discussion in many countries over at least as many centuries. It was recognised that a straight sword was the most effective for stabbing. The Roman sword was short and straight. Much later, the French chose a straight sword that was more than twice as long. It, too, was a poor weapon for cutting, but the fencing techniques that were developed for it made it highly successful because they focussed upon manoeuvres that would result in piercing the opponent’s anatomy with its point.

In the Middle East and Africa, the curved sword was much more common and while the warriors who used them may have lacked the finesse of a French swordsman, they were able to use these swords to terrible effect. The scimitar had such a pronounced curve that its point was barely useable but it was extremely effective in severing limbs from an opponent’s body. The sabre, while retaining the ability to stab, was also a powerful cutting weapon.

The greater efficiency of the curved sword when slashing arises from the slight movement that the curve imparts to the edge as it slices through flesh. The curve of a modern butcher’s knife has the same effect — an aid to the slicing action with which it is employed.

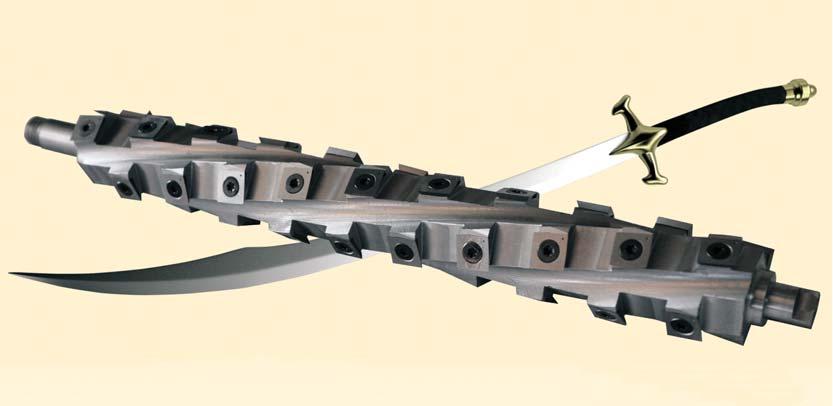

When fitted to a planer or thicknesser, a modern spiral cutter has a similar, though more pronounced effect.

The individual small blades are arranged along a helix which runs the length of the cutter block. On a very few of the cutter blocks, the blades are arranged to chop rather than slice, ie. their edges are aligned with the axis of the block. While the helix configuration eliminates the familiar scalloping that occurs with conventional cutters, it is only when the individual blades are aligned with the helix that the full potential of the system is achieved. The tiny blades now slice through the wood, shearing off shavings and all but eliminating the tear-out which is the natural consequence of a chopping action. This configuration is becoming known as ‘true helix’, presumably to distinguish it from the layout which still allows the cutters to present squarely to the wood.

Most of the planers and thicknessers now available in this region can be purchased with a spiral cutter and it’s doubtful if anyone who has used a machine fitted with one of these cutters would advise against selecting this option. The cost varies from a few hundred to more than a thousand dollars, but this would be repaid many times over during the life of the machine.

The benefits most often quoted for the spiral cutter are the lowering of waste by the rapid production of a smoother surface (generally equivalent to one sanded to about 150grit) and the elimination - or at least, vast reduction - of tear-out, as well as a significant reduction in noise (commonly to a level below 85dBA at which hearing protection equipment becomes mandatory).

Underlying these is the increased efficiency of the cutting action. It takes less energy to slice than to chop, the two very different cutting methods being reflected in the majority of the material caught by the dust extractor (Photo.1).

Machines which are purchased with a spiral cutter already installed offer the easiest way to take advantage of this new technology but for those who already own a machine with a conventional cutter, a Queensland company may be able to offer a solution. Over the past few years, Wood Craft Supplies has developed a series of spiral cutter blocks, each specifically tailored to suit one of the more than 50 machines which are currently covered by the company’s inventory.

The process of retro-fitting a cutter block necessarily varies from machine to machine, but the instructions supplied with each of them generally allows the work to be done by the owner without special tools. Some are quite simple, others more complicated.

One of the latest and most interesting retro-fits has recently been demonstrated at Timber & Working with Wood Shows. This is for the Makita 2012, arguably one of the most popular thicknessers ever sold in this region.

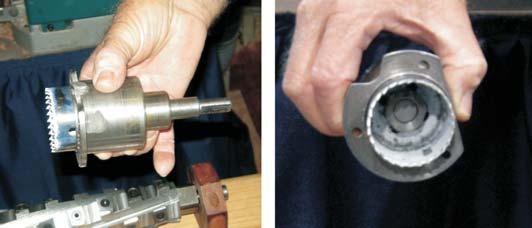

When devising a method for the installation of the new cutter block, Wood Craft Supplies found it would be necessary to change the shape of a hole in a die-cast section of the machine’s frame. This hole permits passage of the original cutter block which has flats ground on opposing sides to carry the knives. It will not, however, allow the new circular cutter block of similar diameter (Photo.2) to pass through.

The retro-fitting of spiral cutters on other machines sometimes requires a little work with a file but the amount of material that has to be removed in this case was considered more than appropriate to ask of a non-tradesman. The company has therefore produced a hole-saw jig, Photos 4 & 5, (the company calls it a Service Tool) which is being loaned to those undertaking the work.

Once the old cutter block and bearing have been removed, the jig can be fixed to the thicknesser using the available mounting screws to ensure it is in exactly the right location. After attaching a portable drill to the jig’s shaft, it takes perhaps 15 seconds to drill out the full circumference of the hole in the frame. The jig is removed and the cutter block and its bearings (either the originals or new) are then installed.

Probably the most interesting and important aspect of this relatively new cutting technology is that whether a machine is purchased new with a true helix spiral cutter installed, or one is retrofitted to a 20 year old machine, there is little, if any, difference in the results that can be achieved.

Article courtesy of Australian Woodworker Magazine

For carpenters, furniture makers or wood traders: The VacuMaster Wood is the ideal lever solution for the woodworking shop.