COOPERATIVE STRATEGIES

Desgin and Urban Ecologies Studio 1 | Parsons School of Design

Desgin and Urban Ecologies Studio 1 | Parsons School of Design

In Fall 2023, witnessing the increasing frequency of climate emergencies such as heatwaves, flash floods, torrential rains and the aftermath of COVID19 pandemic in NYC that had its start in Spring 2020, it became more clear that our networks and systems are underprepared to support the most vulnerable members of our communities. In this studio course we explored social and environmental justice issues with a particular entry point of Housing Development Fund Corporations (HDFC) Coops in LES and South Bronx and public and semi-public spaces surrounding them. The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated existing inequities in communities in NYC and provided a preview of potential future challenges that will deepen with the climate crisis, depletion of natural resources, housing crisis, and others.

The impact of climate change and the pandemic proved that we need to consider critical urban infrastructures in a broader sense that will support residents in various ways. The pandemic has interrupted all the ecologies in our city —health, food, housing, business, education, mobility —at once. It also revealed that the impact was disproportionately on Black and Latinx communities and low-income areas. In order to get to a better state than prepandemic, better-prepared interventions at all scales are necessary. That would require a multi-faceted effort to assess the local damage, understand community resiliency, develop recovery policy and programs, and distribute resources evenly for their implementation for a better “new normal”. In the environmental context, we need, as theorist Max Liboiron points out, pollution is a systemic act of violence where suggestion is shifting the conversation from blame to accountability (Liboiron, 2021). These efforts, therefore should challenge the inequality that has characterized the development of cities and prioritize the needs, priorities, and visions of those traditionally excluded in the production of the city by working closely with those communities.

New York City (NYC), climate change is magnifying the underlying challenges in the city, beginning with housing but extending to every activity that makes the city functioning. We are seeing more often and intense weather abnormalities, we are also seeing more often than not the response operations being overwhelmed or mismatched with the need of the communities that require the support most. Environmental justice frameworks, with all the development that made the approach in tune with the impact on communities, offer a more comprehensive approach to addressing environmental issues, aiming for fairness in the distribution of environmental benefits and burdens (Shepard et al, 2002; Bowen, 2002). This approach highlights the capacity of individuals and communities to adapt to changing circumstances, aligning with the adaptability principle.

Cooperative strategies, considering multiplicity of voices and needs, are crucial for addressing disparities and promoting a better future for all residents. Community-based organizations, active grassroots groups, and community leaders have been vital in navigating crises due to their close connections to the communities;

their rapid response efforts in the provision of food and medical help, organizing against eviction, advocating for access to food, shelter, medical care, and open spaces. Some of these community groups have shifted their activities to adapt to the emerging needs of their community members. Integrating cooperative approaches within environmental justice frameworks helps us ensure equitable outcomes in environmental decision-making processes.

Design is often overlooked in the climate context, as Kian Goh elaborates “[design] – is often the platform through which contesting spatial agendas are visualized and prioritized”. (Goh, 2021;17) Design and urban ecologies Studio 1 is structured as a transdisciplinary studio in which students work in teams to develop design frameworks aimed at speculating on alternative spatial formations, participatory frameworks, and environmental strategies, as well as new models of ownership, property, community organizations, and innovative social and ecological relations. Students choose an urban territory in the New York City in which they discover urgencies as well as opportunities and create partnerships with local organizations to understand specific possibilities for urban transformation. Subsequently, student teams develop design scenarios, strategies, proposals and projects in collaboration and in coordination with local partners, while also considering issues such as the impact of global flows on regional economies and resources.

Students in Urban Ecology Studio 1 develop an understanding on current urban issues impacting New York City, learn to identify relational connections of various urban actors, extract insights, and develop design frameworks and strategies to positively impact in line with social justice values. Using different urban methodologies, students inquire local social, economic, environmental, spatial and political processes working closely with residents, community leaders, grassroots groups, and nonprofits involved in social and spatial justice. Collaborating with external partners, students work in teams through a particular framework and scope, students get a broader understanding of urban ecosystem as well as local implications of community and city plans, as well as local needs and visions. Considering insights from research, external partner(s) visions, local pressing issues and priorities among residents, students identify potential areas of intervention and envision a number of actionable design strategies and propositions to facilitate and carry out local efforts and visions. New approaches, methodologies, ideas, and tools are needed to generate novel ways to build capacity to pursue long-term recovery and resiliency plans that incorporate community perspectives.

Community-based organizations, active grassroots groups, and community leaders have been vital for our students to understand the context of these crises from the community perspective. These groups have the most current insight on the needs, given their direct connections to the communities and individuals; their rapid response efforts in the provision of immediate needs such as food and medical help, organizing against eviction, advocating for access to food, shelter, medical care, and open spaces.

External collaboration for Studio 1 can take different forms. Most often, this collaboration provides an initial entry point to urban issues and NYC with a scalar viewpoint. This view is through the external partner’s connection to its community, their issues and also understanding the larger systems that they are a part of. In Fall 2023, Urban Ecologies Studio 1 collaborated with United Housing Assistance Board, UHAB1 to explore and cultivate innovative community-driven approaches to long-term recovery and resiliency. We received contributions from other organizations, such as the NYC Environmental Justice Alliance, South Bronx Unite and city agencies, such as the NYC Department of City Planning and Emergency Preparedness, to better understand the challenges, particularly around environmental justice, physical and social infrastructures, and resources available to the public. Interactions with community-based organizations help comprehend local communities' challenges and strengths. The course arc transitions from research to design, emphasizing social justice-driven design frameworks and culminating in the development of propositions that support community needs and environmental justice.

The Urban Homesteading Assistance Board, or UHAB, grew out of the self-help housing movement. UHAB was founded in 1973 and started by working with self-organized groups of tenants to convert homesteading projects into limited-equity cooperatives that are affordable in perpetuity and owned by their tenants. Our primary contacts for Fall 2023 were Emily Ng and Rania Dalloul from UHAB, and we are indebted for their generosity and depth of knowledge for this cohort’s work. We have visited the UHAB office, listened and learned about the ongoing work on housing and environmental justice issues, their historical background in NYC rooted in the housing justice movement, and their future vision for housing coops. Studio 1 students conducted archival research at UHAB, and visited UHAB member buildings in Lower East Side and Harlem and talked to the residents. The site visits provided

1. Housing Development Fund Corporations(HDFCs) are affordable housing co-ops legally designated to provide housing to low-income people in New York City. These co-ops are collectively owned and operated by their residents (“shareholders”) who democratically elect a board every year, and make collective decisions about their expenses, energy needs, and roles in the building. Instead of rent, HDFC shareholders pay a monthly maintenance fee. These fees fund the daily operations of the building. HDFCs house majority people of color, and are most often run by women of color. HDFC co-ops offer a model of decommodified, community-controlled housing. (Source: UHAB website What are HDFC coops? https://www.uhab. org/our-work/coop-support/whats-an-hdfc/#:~:text=Housing%20Development%20 Fund%20Corporations%20(HDFCs,people%20in%20New%20York%20City. And oral history of UHAB https://interferencearchive.org/podcast/audio-interference-78-oral-history-of-uhab/

insight to the individual history of these buildings, and residents’ connections to the neighborhood and their community as well as providing insights on UHAB’s latest work in responding to climate change in the building level. UHAB has been spearheading an energy-efficient future for a city where carbon emission reduction should be aimed at every level. UHAB’s work at the cooperatives has been focusing on insulation, installation of heatpumps, and shifting fuel to solar for energy by providing affordable options for the coop residents.

Following UHAB and neighborhood visits Studio 1 also received insights from the Department of City Planning. One of our guest presenters, Michael Marrella provided City’s preparation efforts for waterfront planning and climate resiliency. Information on the city level provided multi-agency efforts and strategies to reduce impact of climate change which provided the studio teams to consider the resources and gaps where they can position their design propositions.

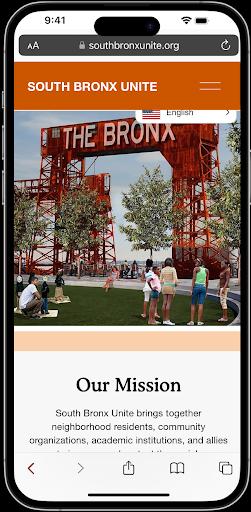

Studio 1’s last neighborhood field trip has been to South Bronx and with generous insights from South Bronx Unite, an umbrella organization that came together came together to unite neighborhood residents, community organizations, academic institutions, and allies to improve and protect the social, environmental, and economic future of Mott Haven and Port Morris, which have, the highest rates of air pollution in the country.Their work covers a broad range of environmental justice advocacy and communty development work. Combining action with citizen-led science. A tour with Mychal Johnson provided a clear understanding of the organization’s work and very limited public open spaces in South Bronx for the residents. Leslie Vasquez, and Arif Ullah from South Bronx Unite also have been very valuable resources for Studio 1 students.

Based on their research for secondary and primary data resources, through fieldwork and visits students decided to focus on three thematic areas and locations, Project teams have been as follows:

Group 1

Aqdas Fatima, Lauren Leiker, Zoe Moskowitz + Chey Socheata

Group 2

Soraya Barar, Isabelle Groenewegen + Rhaynae Lloyd

Group 3

Avery Crower, Leah Roy + Natalie Temple

Design and Urban Ecologies Studio 1 in Fall 2023 created 3 projects that stemmed from the semester-long inquiries. Group 1, explored heatwaves as slow-onset disasters, its impact, and city and community response, Group 2, focused on narratives of climate justice from South Bronx and demonstrated how to use research for advocacy, third and last group inquired lack of public open spaces in Queens and explored how to approach co-design for these areas

Shepard, Peggy M. et al "Advancing environmental justice through community-based participatory research." Environmental Health Perspectives 110.suppl 2 (2002): 139-140.

Liboiron, M. (2021). Pollution is colonialism. Duke University Press.

Goh, K. (2021). Form and flow: The spatial politics of urban resilience and climate justice. mit Press.

From our beginning research stages we learned quickly that applying for environmental justice and climate adaptation funding and support is a very complex process for individuals and community members. It required a long process of preparation, registrations and many constraints that come along with it. Funding also has restrictions and allowable cost to fit with the guideline from the grants system. Community organizations often fill in gaps to provide individual support such as budgeting plans, technical advice, annual reports and many more services for residents to navigate this system.

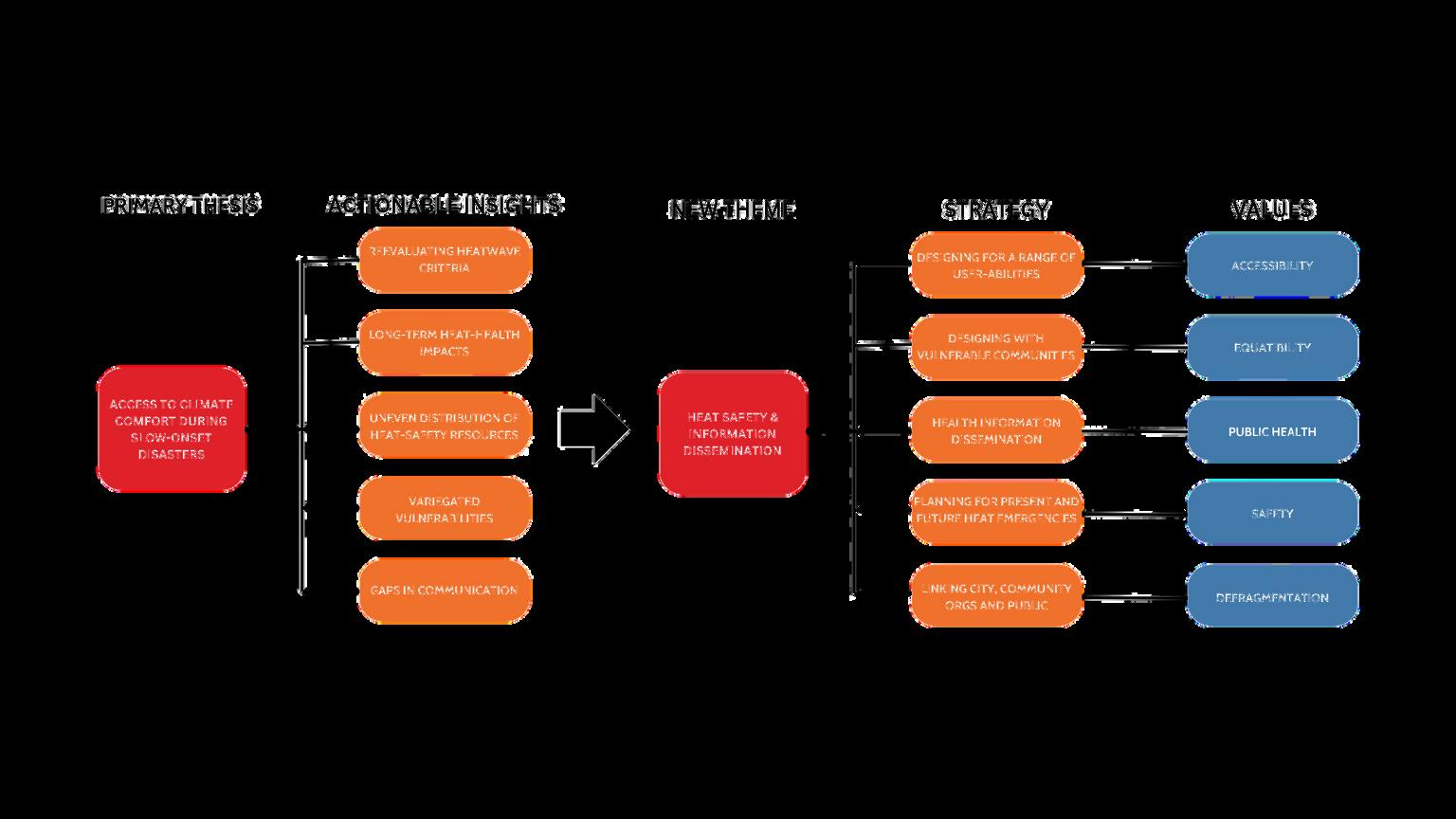

While there are several stakeholders involved in the climate management and disaster preparedness space in NYC, there is an evident disconnect in the ways that their strategies and planning are communicated, implemented, and distributed across communities. One such evident gap is the disconnect between the formation and implementation of government policies related to climate. Additionally, There are gaps in communication & lack of opportunities for dialogue & feedback between individuals, community organizations, and New York City agencies. Information is spread across resources and hard to locate.

For example, a representative from the NYC Emergency Management Department revealed that there are no specific physical documents or leaflets aimed at warnings and information regarding heatwaves, and often cooling centers or other community organizations involved in heat management often end up producing their own resources. In addition, he spoke about how there are separate departments within the city government that are either responsible for addressing heat emergencies or for public communication regarding climate resources - these departments don’t have established channels of communication.

Beginning in the 1960s the state and city level governments have released several plans and policies as responses to hurricanes, heatwaves and other climate related disasters. In addition, the city also has many plans and programs that add to the climate change discourse and make suggestions for improving city resiliency as well as the mitigation of the impact of climate change. However, these plans and policies are usually presented as “visionary documents” rather than regulatory plans. While there is a broader impression of the city moving towards climate protection, especially with ambitious plans such as the OneNYC 2050 plan, the implementations and on-ground practicalities are few and far between. These plans, or more accurately, visionary documents serve predominantly highincome communities and/or areas of high real-estate speculation and development.

According to the OneNYC plan, for example, the city plans to reduce emissions from a 2005 baseline by mandating that all large, existing buildings implement retrofits to be more efficient and lower emissions, reduce emissions including more renewable energy, expanded energy efficiency in buildings and reduced reliance on fossil fuel vehicles. In addition, the plan proposes cleaning up vehicle fleet and implementing congestion pricing. However, there is little information on the progress or implementation of these goals or whether they have been updated. In addition, while these targets are generalized across New York City, there is a lack of consideration for variations in vulnerability to climate disasters, particularly in relation to socioeconomic inequalities, and little explanation for how these are being addressed through such plans.

Similarly, the NYC waterfront plan claims to focus on equity, resilience, and the health of the city’s waterfront. However, this plan has no legal weight and its contents are only intended as suggestions. The plan also competes with community-based plans like South Bronx Unite’s community waterfront plan, which is produced out of the needs of the community and more holistically addresses climate change and resiliency.

While visiting the South Bronx and meeting with Mychal Johnson, a founding member of South Bronx Unite, we discussed the concentration of polluting facilities, last-mile warehouses, and truck routes that pervade the South Bronx community. The detrimental impact these polluting facilities have on residents are only exaggerated when coupled with the evident lack of green space and access to public land in the South Bronx. Through further investigation, including primary research and discussions with community members and leaders, we recognized that this inequitable use of space and uneven development was evidence of racist and discriminatory housing policies and predatory zoning practices. While redlining may no longer be actively practiced, the South Bronx continues to bear the burden of discriminatory policies, exemplified by the new congestion-pricing plan that threatens to exacerbate traffic congestion and air pollution on the already overburdened Cross-Bronx Expressway. Additionally, new realestate speculation and luxury development projects are privatizing more and more of South Bronx’s public land and green space, thus making it inaccessible to long term residents and community members.

In communities that have experienced systemic disinvestment from NYC’s governmental structures, the provision of necessary resources, aid and support has fallen on community organizations, activist groups, and organizers. Government and city organizations are largely focused on search and rescue in the face of disasters. Large established non-government organizations, like the Red Cross, tend to accept only monetary donations because household items need to be cleaned, and sorted which, for them, takes up more time than its worth. These structures leave a void of resources and assistance for communities struggling with lack of electricity, water, heat and food and a need for immediate relief. In the absence of government facilitated assistance communities themselves become the first responders and care-takers.

Additionally, in regards to public land and green spaces, in the South Bronx, the majority of these spaces are tended to by active community members and historical grassroots organizing practices. These spaces not only serve as aesthetic measures for the community but also provide refuge from the pollution and heat as well as hold educational and cultural events.

SOURCE: National Geophysical Data Center, NOAA, 2021

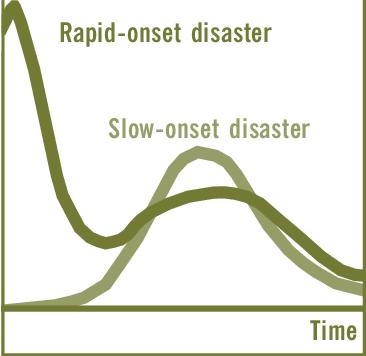

With rising global temperatures, New York City is becoming increasingly susceptible to long-term impacts of slow-onset disasters, i.e. environmental disasters that occur gradually over a long period of time. Alongside, the city has a stretched history of dangerous and consequential heatwaves, with heatwaves becoming recognized as threats to public health in the early 1900s. Despite so, the city still does not seem to adequately inform preemptive and future planning endeavors to ensure protection from slow-onset disasters.

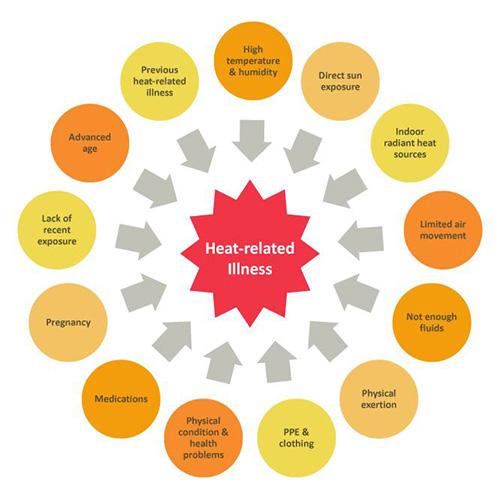

One of the greatest climate risks faced by New York City is an increased frequency of extreme weather events, particularly periods of high heat. In addition, temperatures during summer months have been consistently higher in the previous few years, with 2023 proclaimed to be the hottest year on record. This poses the risk of a slow-onset heat disaster. Such disasters typically lack the urgency, communication, and interventions necessary to keep vulnerable populations safe and sheltered, which becomes concerning considering that on average, each year there are 370 heat-related deaths in NYC. With heat becoming a consistent risk, it is necessary to evaluate the criteria and measures used by the city to declare heat events and their capacity to respond to them through prolonged periods of high temperatures.

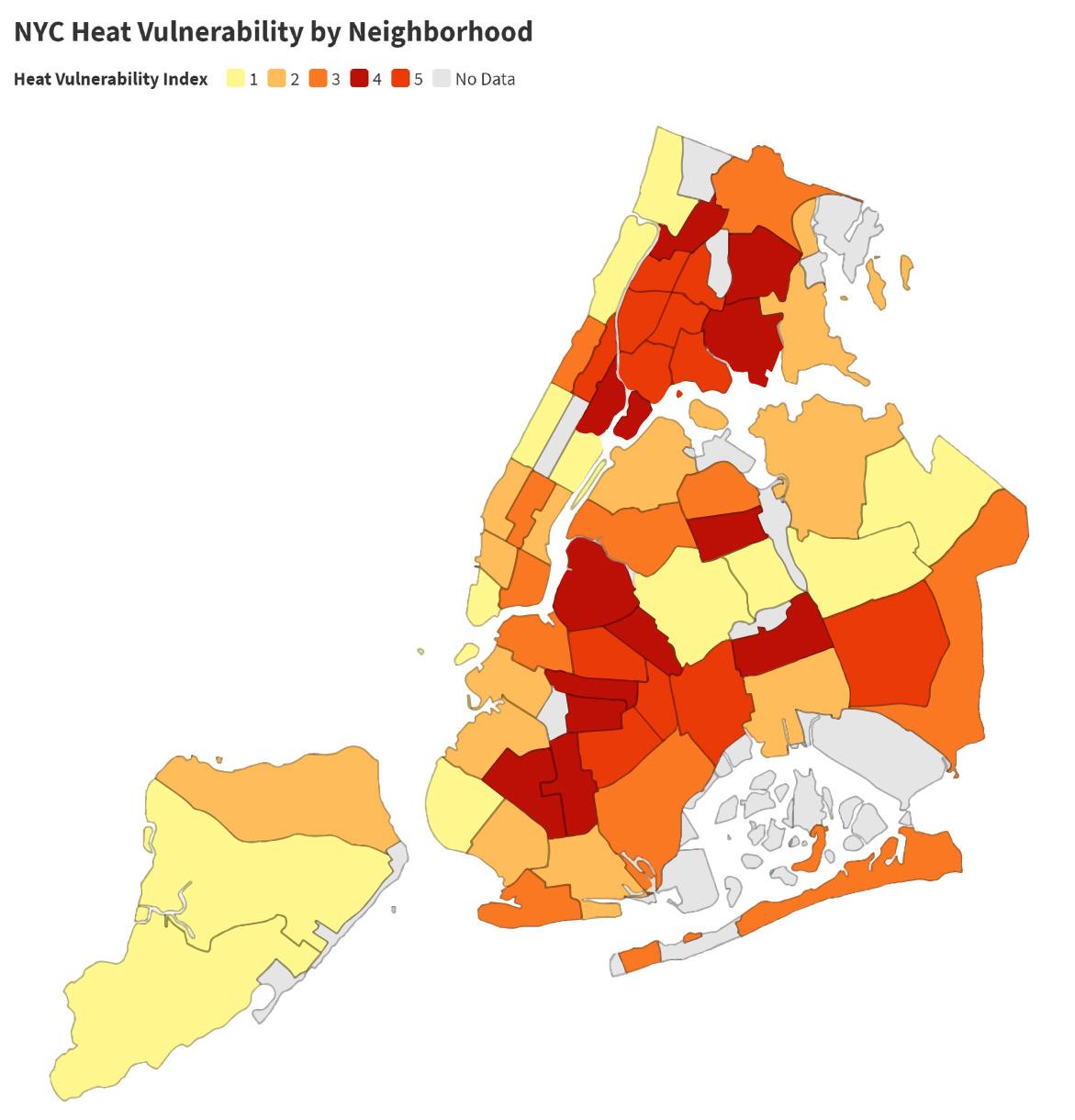

According to NYC guidelines, a heatwave consists of 3 consecutive days with temperatures of at least 90 degrees Fahrenheit, and a heat advisory is issued when the Heat Index is forecasted to reach 95 degrees to 99 degrees for two or more consecutive days or 100 to 104 degrees for any length of time. However, according to the American Geriatrics Society, when the temperature climbs above 80°F, older adults need to take precautions to avoid ailments due to excessive heat. Additionally, the city’s heat vulnerability index outlines that low-income neighborhoods like Mott Haven, Port Morris, and Hunts Point in the South Bronx, are at higher risk of heat-related problems and experience more intense heat due to infrastructural and socioeconomic differences. Yet, heatwave protocols, which are declared city-wide, often fail to capture such vulnerabilities associated with microclimates and socioeconomic inequalities.

Additionally, the city’s categorizations of heatwaves are based on temperature and heat index readings instead of more accurate measures such as wet-bulb globe temperatures, which more accurately account for the risks associated with higher humidity levels.

The amenity effect can be understood as the phenomenon wherein the presence of amenities in a neighborhood, environmental or otherwise, tends to decrease affordability within the area. Without measures aiming to mitigate the amenity effect, these projects are likely to eventually lead to gentrification and displacement of current residents, particularly those living in affordable housing and marginalized communities.

This effect is most predominant in neighborhoods with histories of systemic disinvestment, including formerly redlined areas where people of color have been excluded from property ownership and generational wealth accumulation. Historically, these neighborhoods have been excluded from many forms of investment. However, as real estate speculation grows, investments in amenities such as parks, public spaces, and plazas increase. These new amenities are often followed by rising rental prices in areas with low homeownership rates, and without community involvement or consideration of this impact in the design process ,this often leads to gentrification. This can be acutely seen in the South Bronx neighborhood of Mott-Haven Port Morris where parks and green spaces have historically been a rarity. Real estate speculation continues to gain momentum in this neighborhood, and so does the amenity effect, as new privately owned green spaces are created, continuing to deny long-term residents access to their neighborhood’s waterfront.

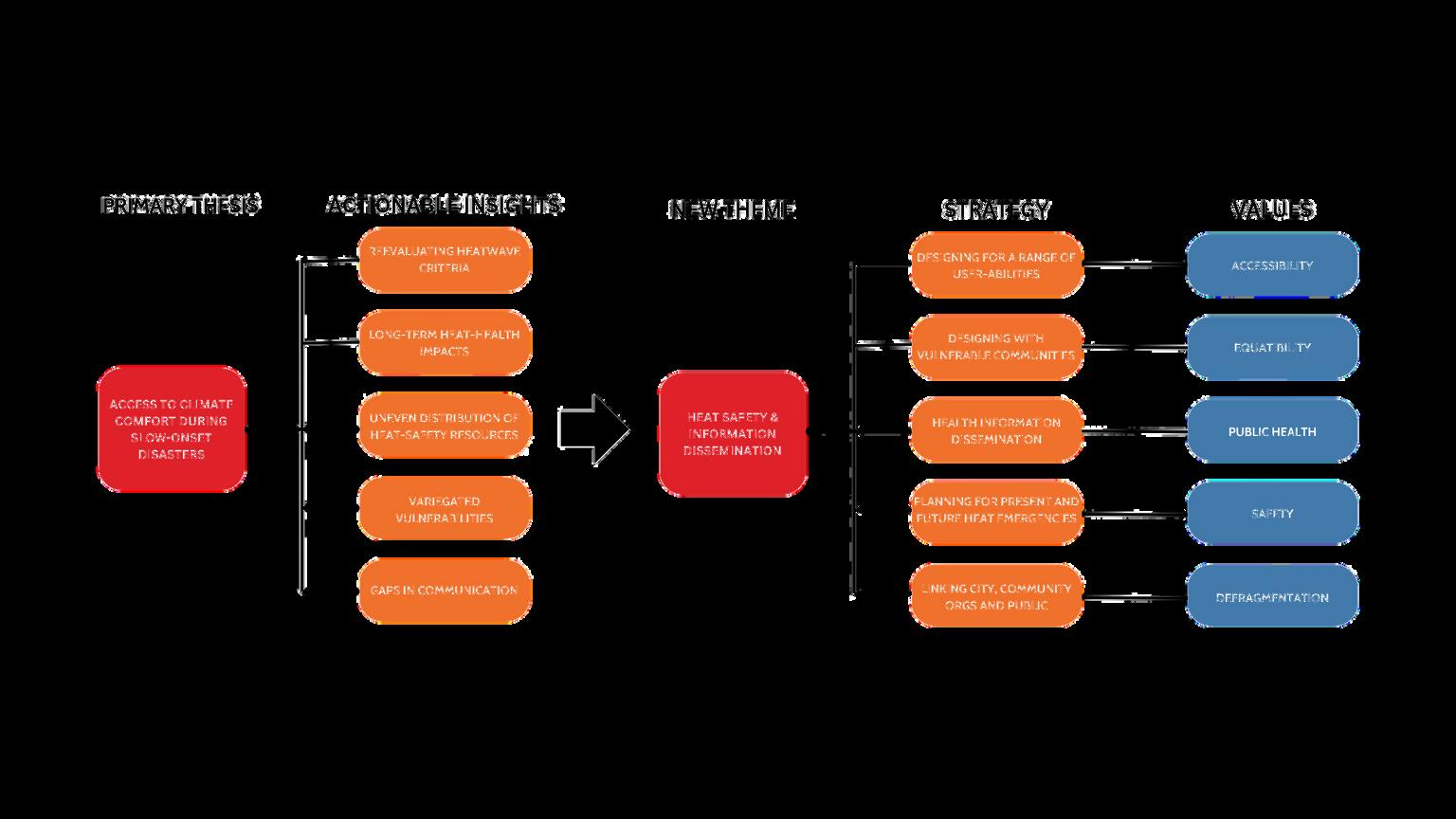

aqdas fatima, lauren leiker, chey socheata + zoe moskowitz

One of the greatest climate risks faced by New York City is an increased frequency of extreme weather events. Prolonged periods of extreme temperature are a slow onset disaster. Due to the velocity that slow onset events are felt, they typically lack the urgency, communication, and interventions necessary to keep vulnerable populations safe and sheltered. Additionally, prolonged periods of temperature are often left out of policy and planning initiatives.

Our project will focus on slow onset periods of extreme heat. Within New York City, emphasis is placed on heat waves and heat advisories. Due to this, long term factors and consequences are often overlooked. We have been seeing consistently high temperatures throughout our summers, and recent years have broken previous highest temperatures.

While there are heatwave management strategies in place by the New York City government, they often put the responsibility on individuals to protect themselves. Additionally, these resources are created by multiple agencies that lack internal communication with each other and the communities that are suffering. This project aims to provide a resource for community members and organizations with an accessible communication channel and essential data.

This project is community driven and centered. Our deliverable includes a digital application with a goal to improve the heat management landscape through a few factors: Designing for a range of user abilities, sourcing and providing community driven experiences, dissemination of health information, linking community organizations with the public for streamlined communication, and filing in the gaps of heat safety infomation and data.

Low-income neighborhoods suffer from some of the highest levels of HVI (Heat Vulnerability Index) and prolonged periods of heat due to a plethora of factors. This is due to historical urban planning policies, outdated infrastructure, minimal funding, and an absence of green space. Additionally, these areas lack communication resources in periods of slow onset extreme heat. Due to this, we decided to pilot our project in the South Bronx.

Our research began with learning and defining what temperatures trigger a heat wave and heat advisory in New York City. A Heat Wave consists of three consecutive days with temperatures of at least 90 degrees farenheit. A Heat Advisory is when the "Heat Index" is forecasted to reach 95 to 99 degrees farenheit for two or more consecutive days or 100 to 104 degrees farenheit for any length of time. The "Heat Index" is an estimate of how it feels when air temperature and humidity are combined.

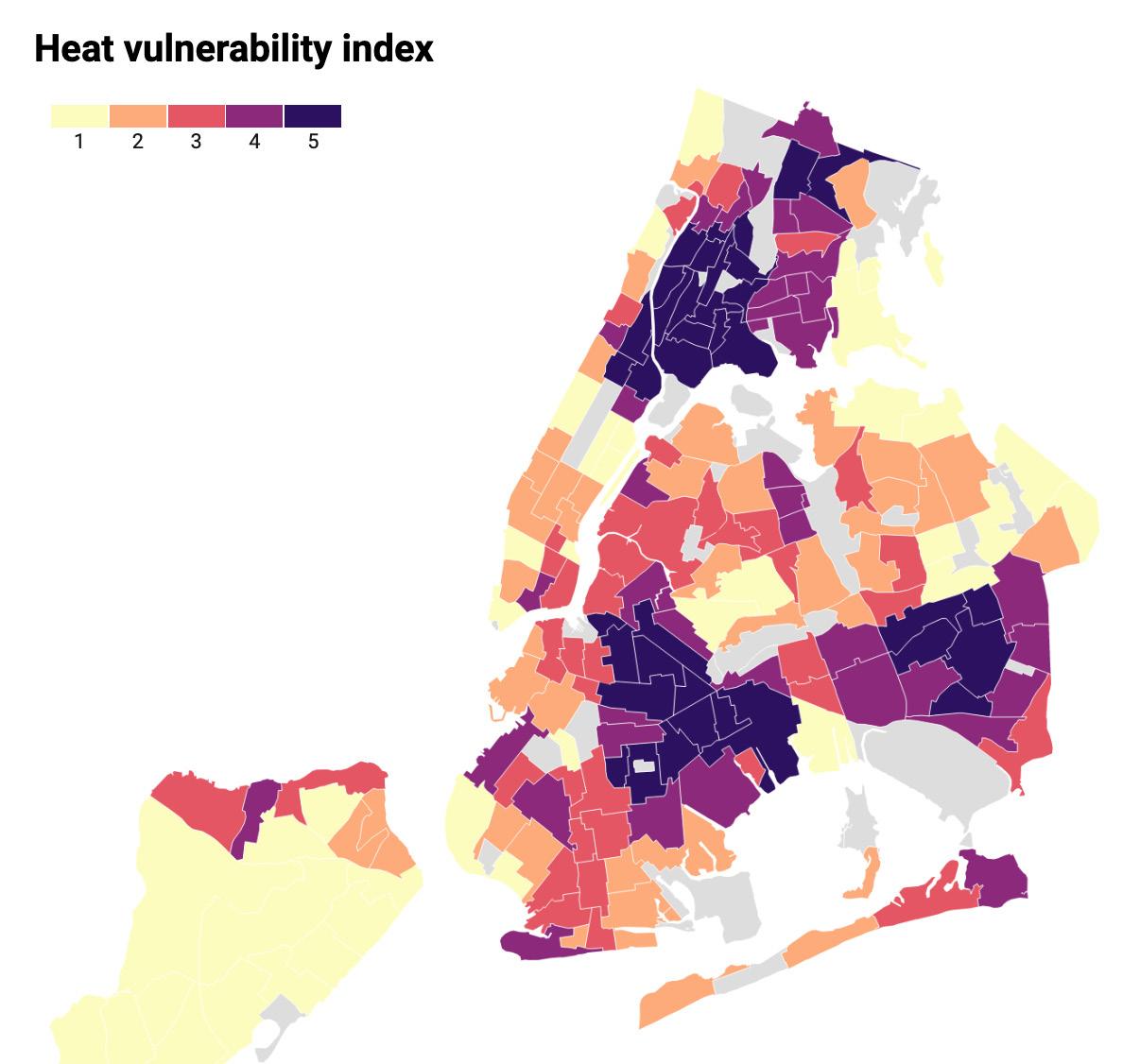

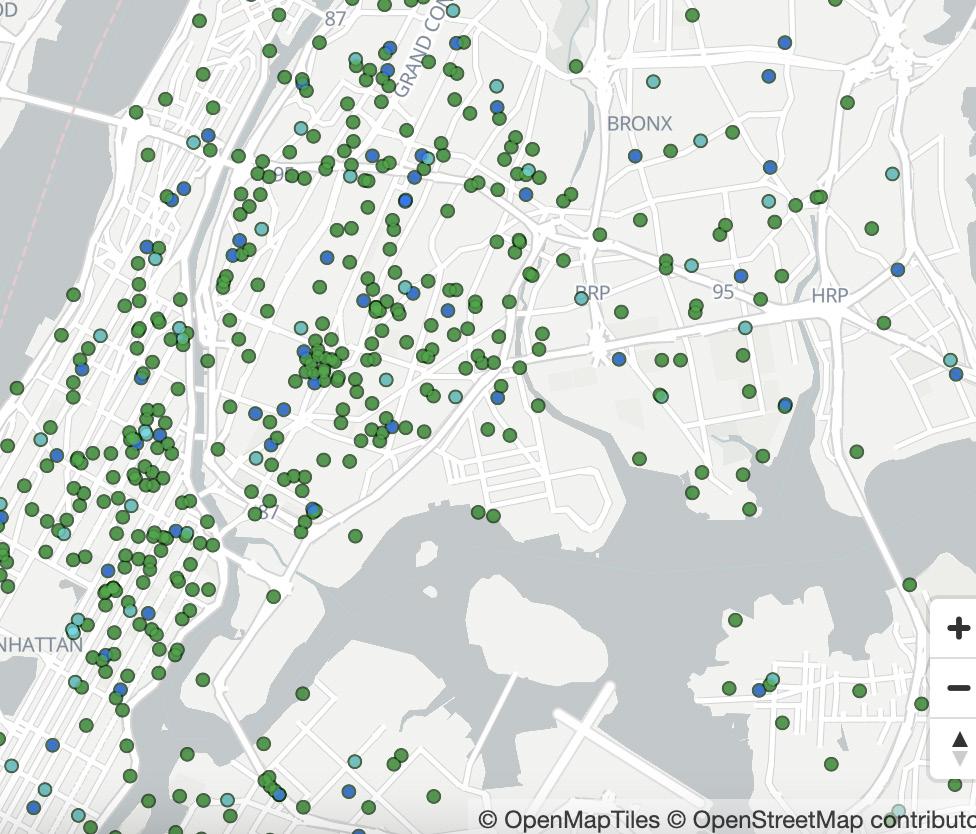

The map on the right shows the "Heat Vulnerability Index" or HVI in New York City. The data that is used to calculate HVI includes social and economic factors such as surface temperature, green space coverage, access to home air conditioning, and the percentage of residents who are low-income or non-Latinx Black. Neighborhoods are scored from one to five, with one being the least amount of residents at risk for suffering or dying during extreme periods of heat and five being the highest amount.

Looking at the HVI Map below, we can see there is a discrepancy in how certain boroughs and neighborhoods in New York City experience extreme heat. In low-income neighborhoods like Mott Haven, Port Morris, and Hunts Point in the Bronx, the HVI is represented with the darkest purple - a level five. However, in areas with a higher income population, like the Upper West Side and the West Village, the HVI level is represented in yellow - a level one. Due to this uneven distribution of heat, residents that live in areas with high HVI levels experience hotter days at a larger frequency.

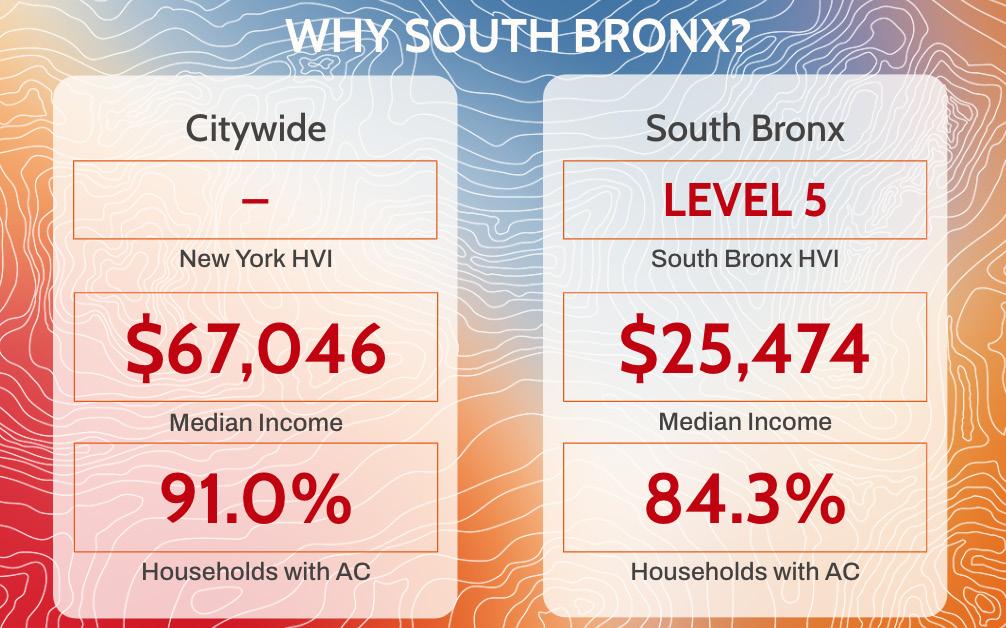

The data on the image to the left compares the South Bronx neighborhood of Mott Haven to city wide averages on HVI, Median Income, and Households with Air Conditioning. These metrics were taken from the Environment & Health Data Portal. We can notice a stark differences in Median Income (about $42,000) and a 7% difference in Households with Air Conditioning.

Due to a plethora of historic and man-made factors, the South Bronx suffers from prolonged periods of heat.

1. Decades of redlining and segregation have caused the area to become structurally underdeveloped.

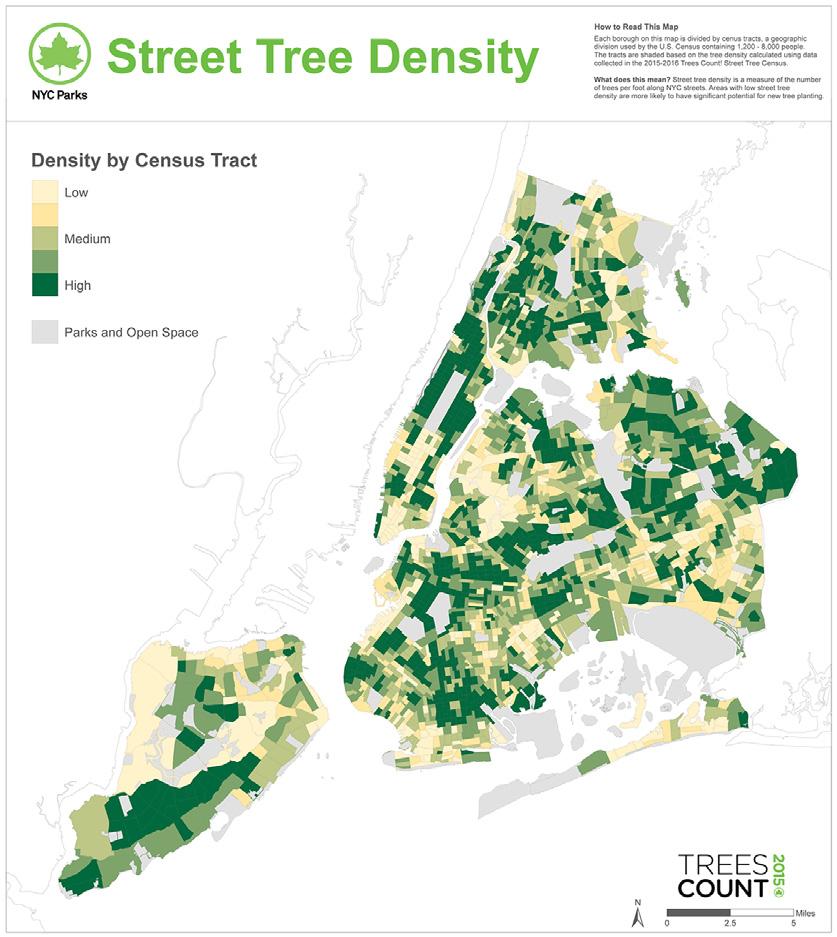

2. Lack of greenspace, parks, and shade coverage factors in to temperatures being anywhere from 1-7 degrees higher during the day and 2-5 degrees higher at night.

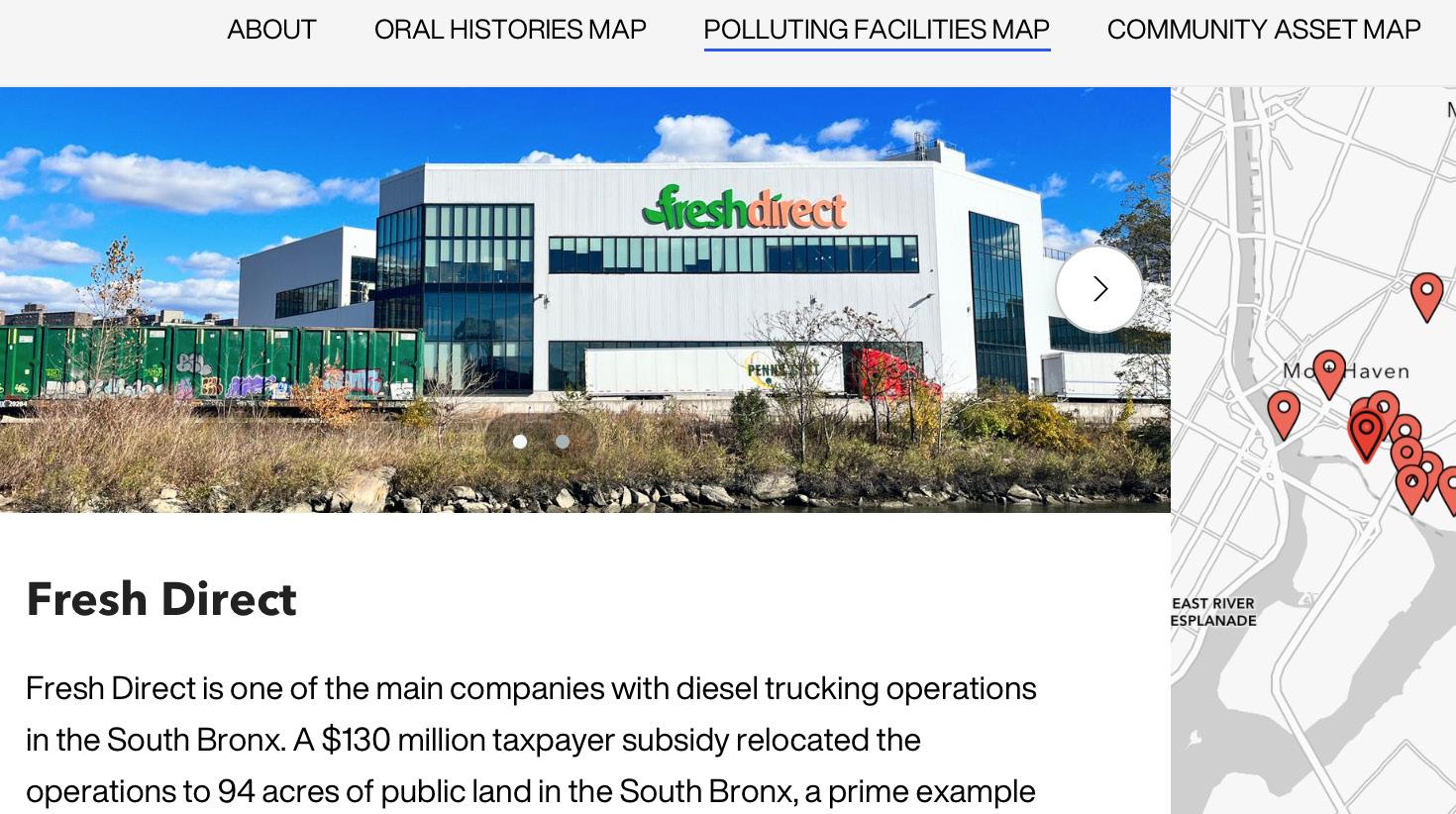

3. Expressways and industrial businessess create more waste heat & CO2. Two of the largest polluters are the Cross Bronx Expressway and Fresh Direct.

4. There are not enough cooling centers in the South Bronx Area.In the summer of 2023 there was one to serve the entire Mott Haven and Port Morris neighborhoods.

5. Pollution from waste heat increases temperature and asthma rates. The South Bronx has some of the highest asthma rates in the state.

6. There is no direct channel of communication to New York City government officials from community organizations or individuals to assist with extreme heat management.

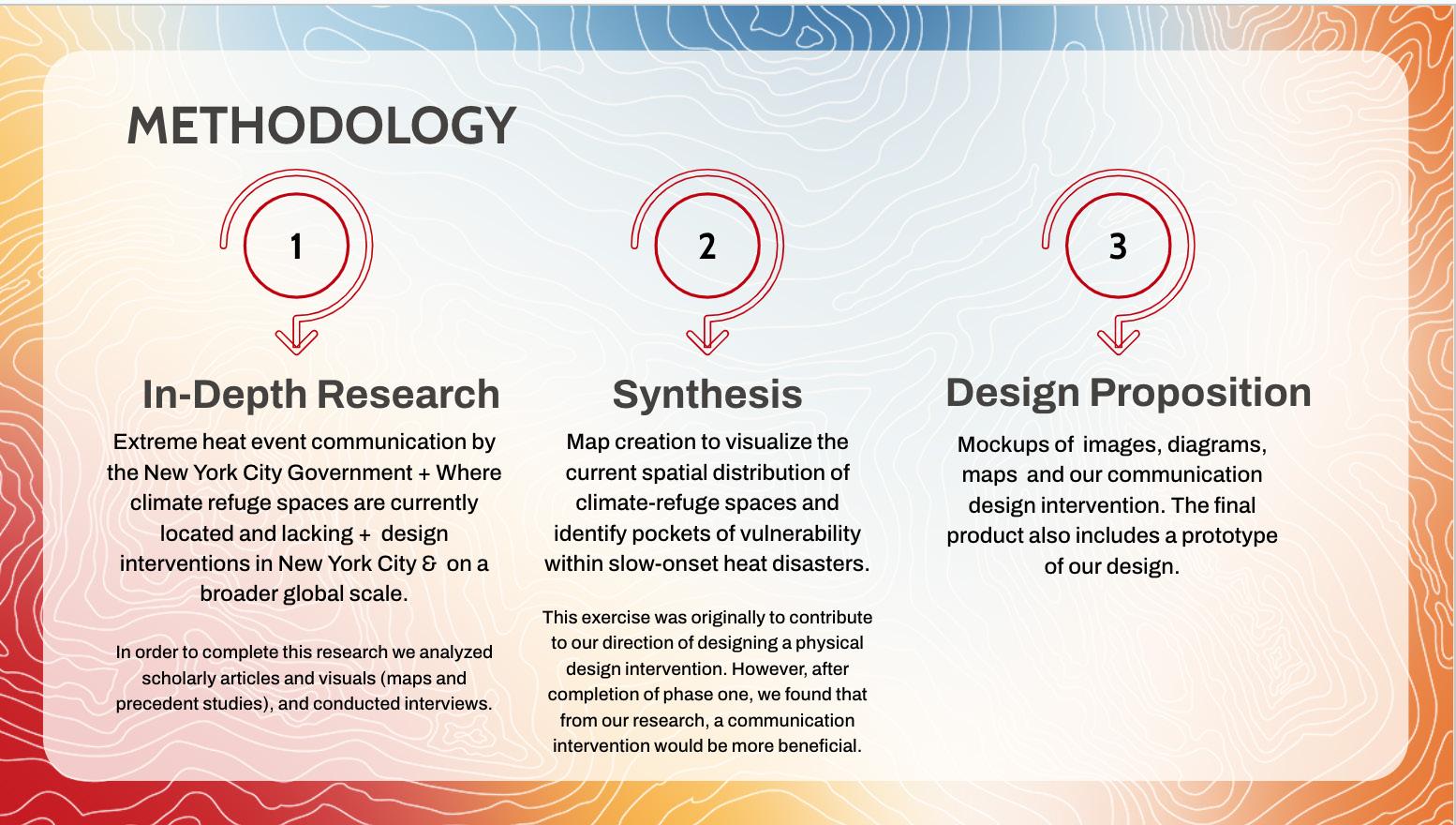

For our project process we began with wanting to research how vulnerable populations access climate refuge during slow-onset disasters. Additionally, we wanted to create a design intervention that could be utilized during prolonged periods of extreme heat. This led us to our actionable insights that were developed from the scholary articles analyzed and interviews conducted. After our research was conducted, we shifted focus to create a communication intervention as this was what community organizations and individuals were lacking in their communities. We developed our strategies as a guide for our final deliverable and related each point to one of our values.

Our preferred outcome envisions two audiences for the project. The first including individual residents and the second being community organizations. For individuals, we want to bridge the gap in communication about extreme temperature from NYC Government and local organizations. Additionally, we want to give users the opportunity to contribute to community sourced data. Ultimately, users should be able to learn and plan more about the cooling measures available in their area. For community organizations, the application is an opportunity to share information with users and collect community driven data on the hyperlocal level. This provides a greater understanding of where to distribute resources, specifically for groups that have limited resources to begin with.

There were three major limitations we faced during our project development. Our experience with creating and designing a mobile application was minimal and self taught. Secondly, the project focused on prolonged heat events but the our research was conducted during the fall and winter months. Lastly, we had a limited amount of time to speak with community members, agencies, and individuals to obtain extensive information. In total we developed and finished this project in 8 weeks.

The values represented in our application are Equity, Accessibility, Safety, Public Health, and Defragmentation. Equity focuses on providing data and health information to all individuals regardless of socioeconomic status or race. Accessibility focuses on building features with a variety of user abilities in mind and aims for data transparency when providing information to community organizations. Safety involves understanding the levels of risk that vary within populations and locations suffering from extreme heat. Additionally, the short and long term health effects. Lastly, Defragmentation includes bridging the gaps in communication and heat data between cities, groups, individuals.

There are invisible Impacts of extreme temperature. Heat can put stress on municipal and organizational systems as well as compound high energy use and isolation.

There are gaps in communication & lack of opportunities for dialogue & feedback between individuals, community organizations, and New York City agencies. Information is spread across resources and hard to locate.

Many of the solutions for extreme temperature events are placed in the individuals responsibility rather than a larger system of care. The individualized approach of protection and preparation leaves a large population vulnerable.

Specifically in the South Bronx, there is a lack of accessible cooling facilities. Parks, gardens, waterfront space, libraries, and emergency services lack during events of extreme heat.

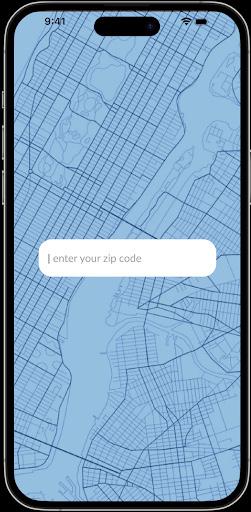

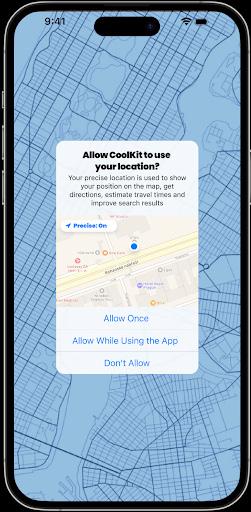

CooKit is a protoype mobile application designed for community organizations and community members. The applications purpose is build accessible communication channels, provide data provision and data collection, and address digital inequalities. In specific, community organizations will be able to utilize the application to channel resources and aquire data while community members can access resources

HeatHelp Chatbox:

The HeatHelp Chatbox is a chat bot that will operate based on a produced list of frequently asked questions. Users will be able to enter their questions into the chat box, and will be guided with answers to frequently asked questions.

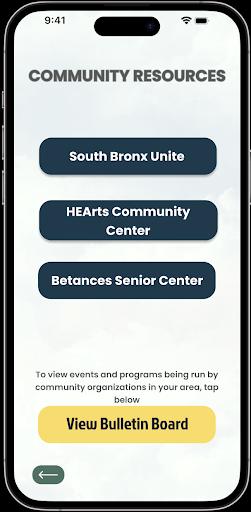

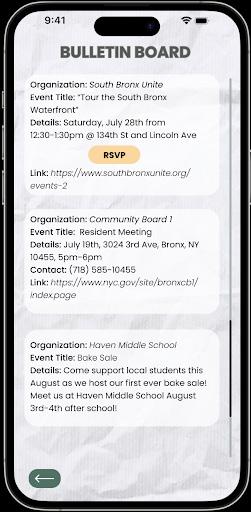

As the app requires a zip code input, this page provides community resources available within the user’s zip code area. As the zip code entered here is for the South Bronx, this page links users to the various organizations working in the South Bronx such as South Bronx Unite and the HEArts community center. The page also allows for users to tap into a bulletin board, which contains posts by community organizations regarding events and notices.

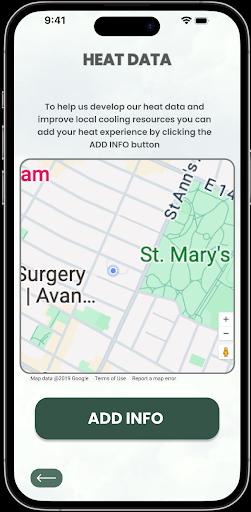

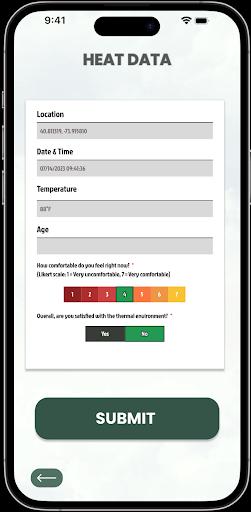

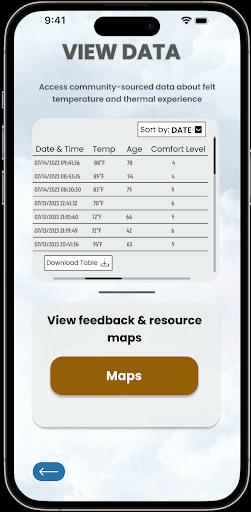

The heat data tab is a feature that allows for crowd sourcing heat data by asking users to add information regarding their heat experience through a survey form. The main page explains why this data is being connected, and users can use the button at the bottom of the page to fill out a form at their location. The form assesses heat experiences through Likert scale and binary coded questions, and autogenerates information on location, temperature, and date and time. Once the user clicks submit, this information gets attached to their pinned location, and is accessible on the map. In addition, this map is accessible through the maps tab on the resource page. Heat Data collected through this tab will also be accessible in table form when users log in through the community organization tab.

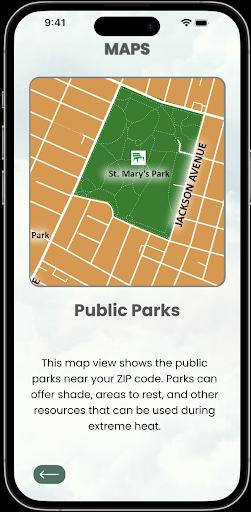

The last tab in resources is titled Maps. This tab provides access to maps that were generated by our team. These maps identify locations of resources that can help with self-regulation during periods of extreme temperatures outdoors, such as, public parks, shaded areas, libraries, and community centres. The maps can be scrolled through and zoomed in and out for easy visibility. As with the resource page, these maps are generated based on the zip code entered by the user. In addition, the maps tab also links to a dat map generated from the Heat Data tab.

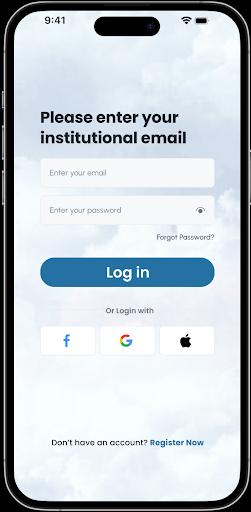

For community organizations that use the app, we included a login feature, to add a layer of security between the community-sourced data and those that might wish to access it. This section of the app has two main pages: a place to access the crowd-sourced data and a place to upload information and resources for the community. In the access tab, we have options to both view and download the information from the “Add Info” tab in the individual user facing section. In the upload tab, there are options to add events or resources to the bulletin board, or to add information about their organization for the “Community Resources” section.

Community Profile:

For community organizations that use the app, we included a login feature, to add a layer of security between the community-sourced data and those that might wish to access it. This section of the app has two main pages: a place to access the crowd-sourced data and a place to upload information and resources for the community. In the access tab, we have options to both view and download the information from the “Add Info” tab in the individual user facing section. In the upload tab, there are options to add events or resources to the bulletin board, or to add information about their organization for the “Community Resources” section.

Future Use:

While this app is focused on extreme temperature as it relates to heat, we also envision a similar interaction of this project that would be utilized during the colder months, especially during freezing or near freezing temperatures. This way, users would be able to learn about resources in the community about the cold, as well as use the app when seeking refuge during times of low temperatures. Many of the organizations that we held discussions with had done previous work on heat because of their focus on climate injustice and the disparate effects of climate change on communities, but did not have a direct focus on extreme cold. However, given their connection to the communities in which they worked, and their communication and collaboration with residents, the work of educating and supporting people during both ends of extreme temperatures means that our work would be greatly rooted in the ethos of community activism and environmental justice.

We want to extend a special thanks to Evren Uzer for facilitating us throughout this project, and to the wonderful people we interviewed who took out time to help us develop our theoretical framework and understand the landscape of heat management in NYC.

+ anna mc culla + william pappas, NYC emergency management department

caleb smith, WeAct

david calvart, hdfc co-op resident

mychal johnson + leslie vasquez, south bronx unite

michael marrella, NYC department of city planning

wendy brawer, collective for community, culture, & the environment

Amorim-Maia, A. T., Anguelovski, I., Connolly, J., & Chu, E. (2023). Seeking refuge? The potential of urban climate shelters to address intersecting vulnerabilities. Landscape and Urban Planning, 238, 104836.

Bian, G., Gao, X., Zou, Q., Cheng, Q., Sun, T., Sha, S., & Zhen, M. (2023). Effects of thermal environment and air quality on outdoor thermal comfort in urban parks of Tianjin, China. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 30(43), 9736397376.

Boumaraf, H., & Amireche, L. (2021). Thermal comfort and pedestrian behaviors in urban public spaces in cities with warm and dry climates. Open House International, 46(1), 143-159.

Fraser, A. M., Chester, M. V., & Eisenman, D. (2018). Strategic locating of refuges for extreme heat events (or heat waves). Urban Climate, 25, 109-119.

Hamstead, Z. A. (2024). Thermal insecurity: Violence of heat and cold in the urban climate refuge. Urban Studies, 61(3), 531-548.

Jacobs, B., Schweitzer, J., Wallace, L., Dunford, S., & Barns, S. (2018). Climate adapted people shelters: A transdisciplinary reimagining of public infrastructure through open, design-led innovation. Transdisciplinary Theory, Practice and Education: The Art of Collaborative Research and Collective Learning, 257-274.

Johansson, E., Yahia, M. W., Arroyo, I., & Bengs, C. (2018). Outdoor thermal comfort in public space in warm-humid Guayaquil, Ecuador. International journal of biometeorology, 62, 387-399. Lander, B. (2022). Overheated, Underserved: Expanding Cooling Center Access. Comptroller.nyc.gov. https:// comptroller.nyc.gov/reports/overheated-underserved/

Madrigano, J., Lane, K., Petrovic, N., Ahmed, M., Blum, M., & Matte, T. (2018). Awareness, risk perception, and protective behaviors for extreme heat and climate change in New York City. International journal of environmental research and public health, 15(7), 1433.

Maretto, M., Gherri, B., Chiovitti, A., Pitanti, G., Scattino, F., & Boggio, N. (2020). Morphology and sustainability in the project of public spaces. The case of the historic centre of Viterbo (Italy). The Journal of Public Space, 5(2), 23-44.

Nouri, A. N. L. D. S. (2018). Addressing urban outdoor thermal comfort thresholds through public space design.

Oliveira, S., & Andrade, H. (2007). An initial assessment of the bioclimatic comfort in an outdoor public space in Lisbon. International Journal of Biometeorology, 52, 69-84.

Peng, Y., Feng, T., & Timmermans, H. J. (2021). Heterogeneity in outdoor comfort assessment in urban public spaces. Science of the Total Environment, 790, 147941.

Santos Nouri, A., Costa, J. P., Santamouris, M., & Matzarakis, A. (2018). Approaches to outdoor thermal comfort thresholds through public space design: A review. Atmosphere, 9(3), 108.

Tavares, S. G., Sellars, D., Mews, G., Dupré, K., Cândido, C., & Towle, S. (2020). Public health and wellbeing in public open spaces through climate responsive urban planning and design. The Journal of Public Space, 5(2), 1-6.

Vukmirovic, M., Gavrilovic, S., & Stojanovic, D. (2019). The improvement of the comfort of public spaces as a local initiative in coping with climate change. Sustainability, 11 (23), 6546.

Wilson, E., Nicol, F., Nanayakkara, L., & Ueberjahn-Tritta, A. (2008). Public urban open space and human thermal comfort: The implications of alternative climate change and socio-economic scenarios. Journal of Environmental Policy and Planning, 10(1), 31-45.

soraya barar, isabelle groenewegen + rhaynae lloyd

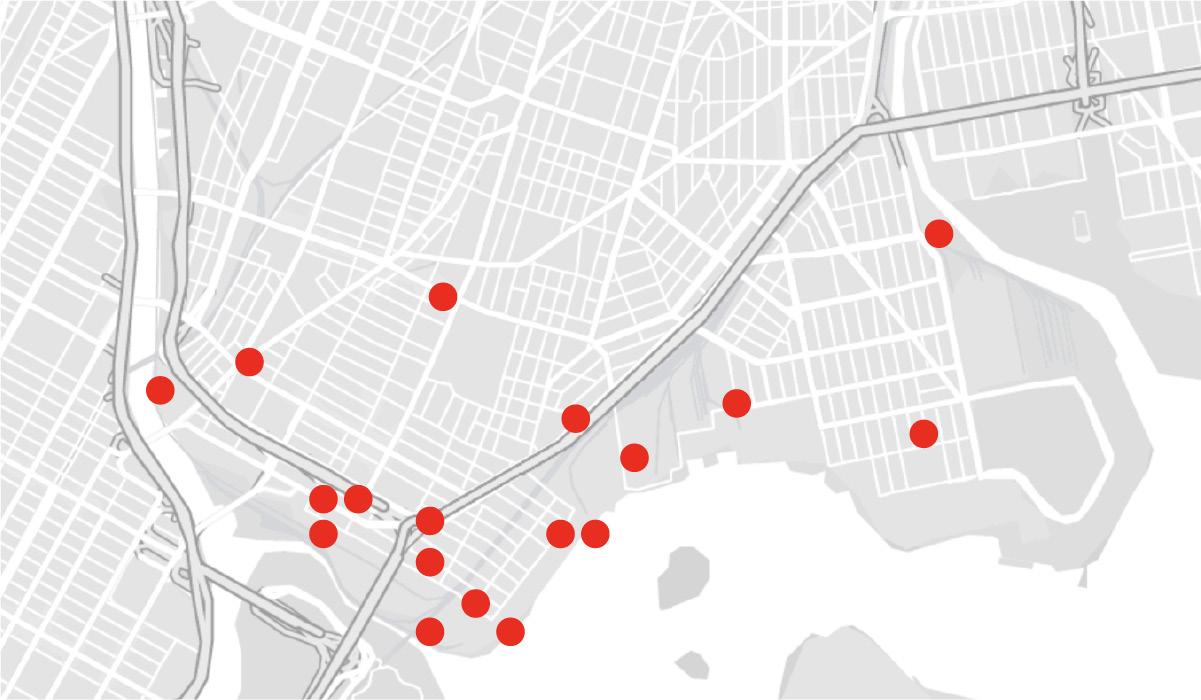

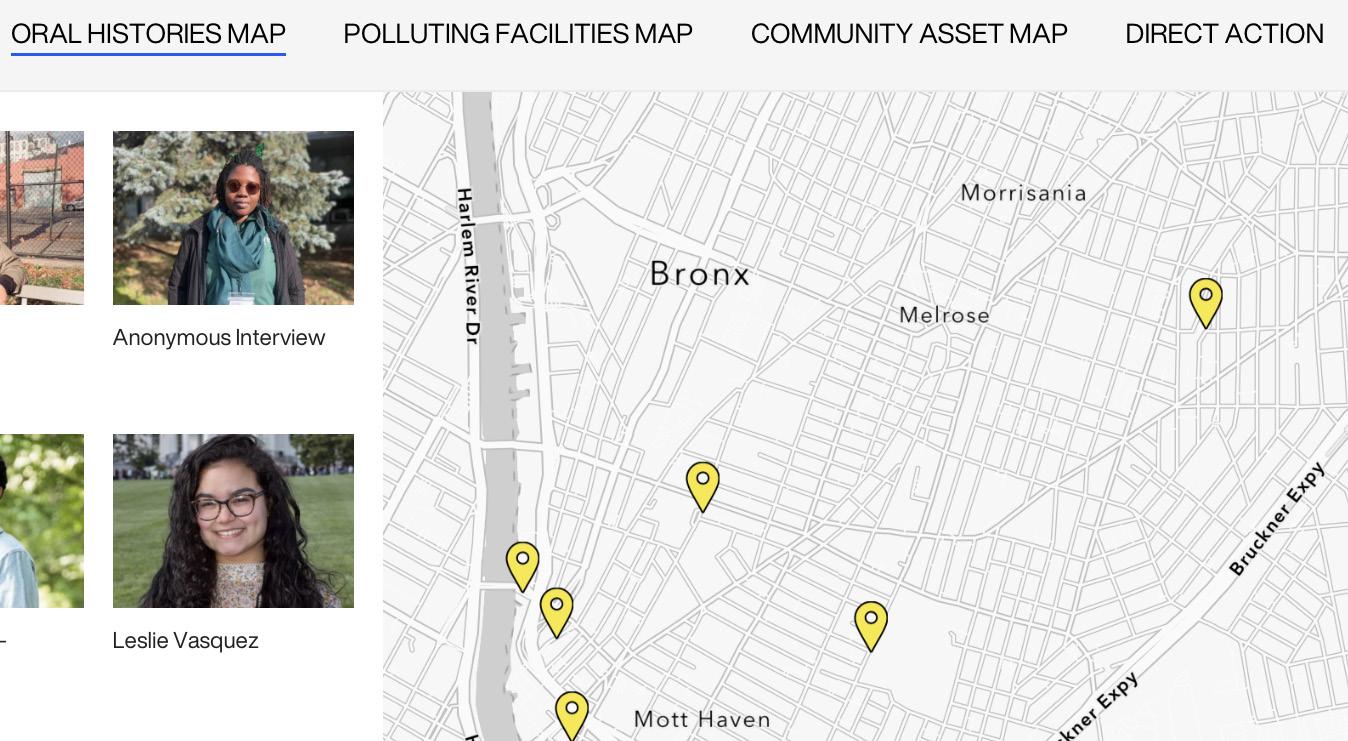

The output of our Studio 1 class is a series of oral histories mapped across the South Bronx and published online via Story Maps. The audio map details the lived experiences of South Bronx residents and activists (often they are one and the same). We have created this map as a means to add personal detail to the data and statistics that reflect the negative environmental health impacts of living in an area blighted by high air pollution and extremely high asthma rates.

The intention is for posters disseminated across the city to lead curious New Yorkers to our website, offering the opportunity for education on environmental racism from those experiencing it. We have an oral history map, a polluting facilities map, a community resources map, and a page dedicated to direct actions listeners can take to engage with South Bronx based activists on tackling this issue.

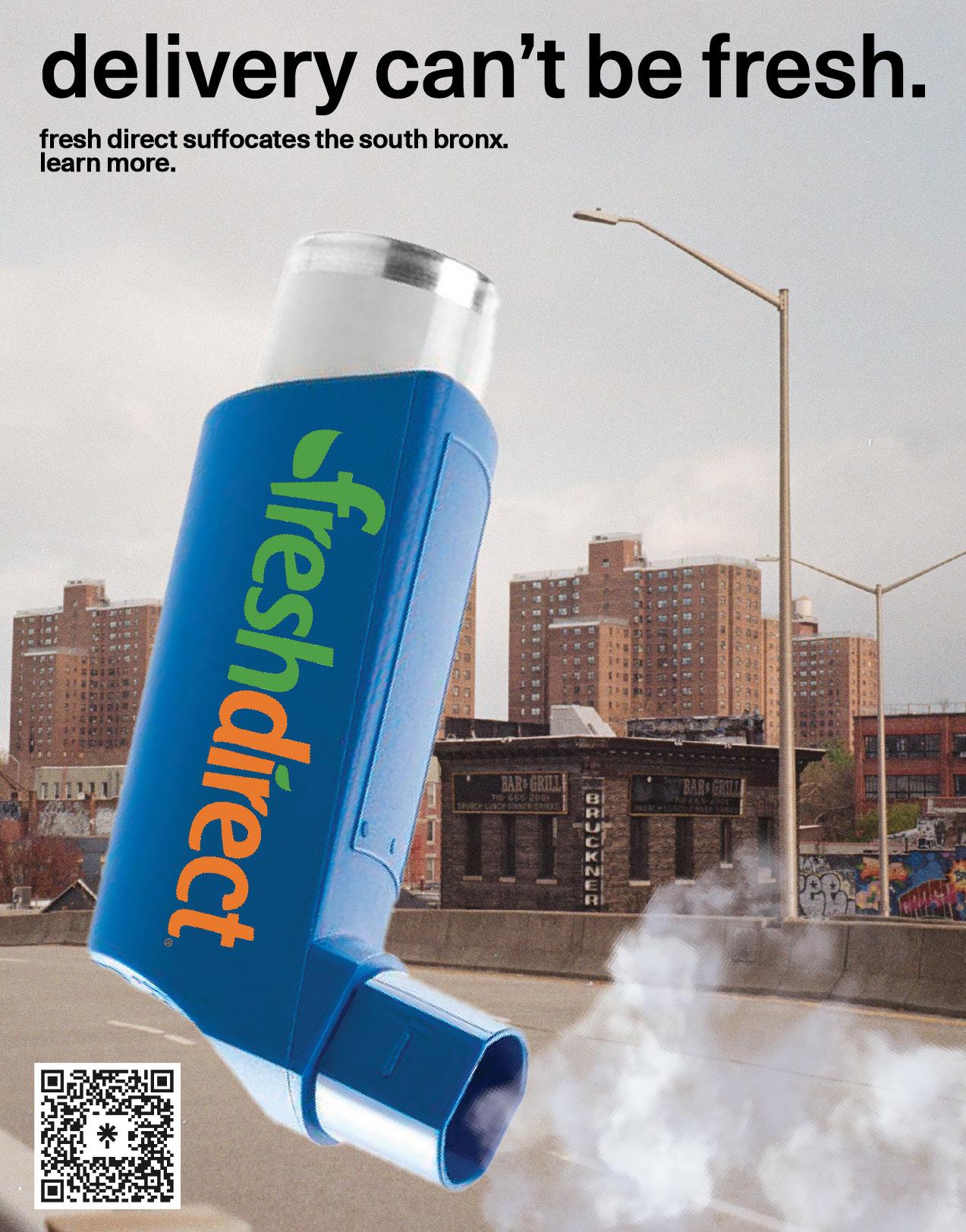

Due to the history of city-level neglect of the South Bronx, many local residents have become grass roots advocates for the health of their community, expressed by the presence of organisations such as South Bronx Unite (SBU). SBU put up a strong battle against the placement of grocery delivery corporation Fresh Direct’s operations on 94 acres of public land in the South Bronx, financed in part by a $130 million dollar tax-payer subsidy.

In fact, it was through Mychal Johnson, one of SBU’s co-founders, that we were privy to the environmental injustices that South Bronx residents experience as a result of such placements; high rates of air pollution and asthma can be traced to the significant presence of trucking routes in the area and compounded by a lack of public green space. Sitting with Mychal in the Maria Sola park, a parcel of abandoned land made verdant and lush by the community despite its highway-adjacent location, was an allegory for the history of the area. Residents look after themselves while being consistently overlooked by city-level actors in favour of profit making construction and business deals.

While there is a lot of data on how air pollution and other environmental issues affect the health of residents in the South Bronx, we rarely hear the stories behind the numbers. How could we develop a design intervention that would raise awareness for this complex issue when so much has already been done by community activists? Recognizing that it is the dehumanization of minoritized groups that allows for city and state-level neglect and disinvestment, we wanted to develop an oral history project that used storytelling to make the impacts of air pollution in the South Bronx more visible/audible.

South Bronx residents detail their personal experience of poor air quality and intersecting environmental injustices, conveying how these issues negatively affect their quality of life. The experiences of community activists are also recorded to reflect the ongoing legacy of grass-roots action taken by residents to improve their own livelihoods in the face of neglect by government actors.

This project ultimately serves as an advocacy tool for communities who disappear behind data and statistics and as a recognition of the underrepresented grass-roots work community members have undertaken historically and now.

Health equity and issues of environmental justice and racism are inextricably linked. These linkages create cycles of generational harm that impact entire communities' quality of life. The South Bronx is a clear example of these linkages and of how systemic neglect, environmental injustice and racism impact individuals and communities as a whole.

The Bronx is the northmost borough of NYC. It is a peninsula that borders the Hudson, Harlem, and East Rivers. Residents are cut off to their waterfront due to highway routes along the Bronx’s borders.

The South Bronx is a neighborhood that includes communities south of the Cross-Bronx Expressway and west of the Bronx River. (1) Mott Haven and Port Morris are the two main neighborhoods of the South Bronx, with the former also being known by the alias “Asthma Alley.”(2)

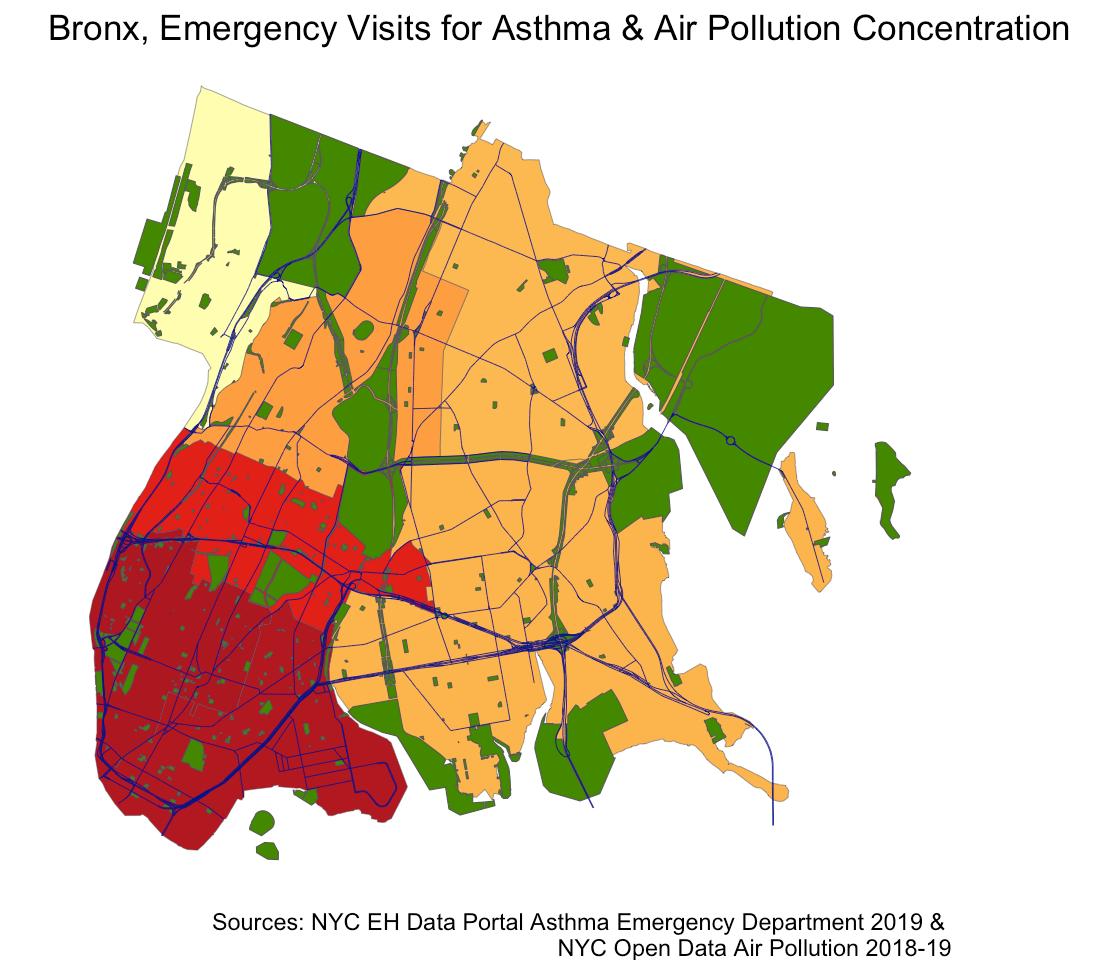

Multiple studies corroborate residents’ lived experience of asthma and other common health issues being caused by environmental injustices. Excessive pollution caused by industrial activity and the emissions from the major trucking routes that cut through the borough contribute to poor health outcomes for residents. Not to mention the dearth of public space, accentuated by the trucking routes cutting off access to the waterfront.

Construction of the Cross Bronx Expressway was built under the rule of Robert Moses starting in 1948. More than 60,000 people were directly displaced by its construction - the most of any single infrastructure project in American history.(3) The resulting reduction in property value and the lure of suburbia resulted in white flight.

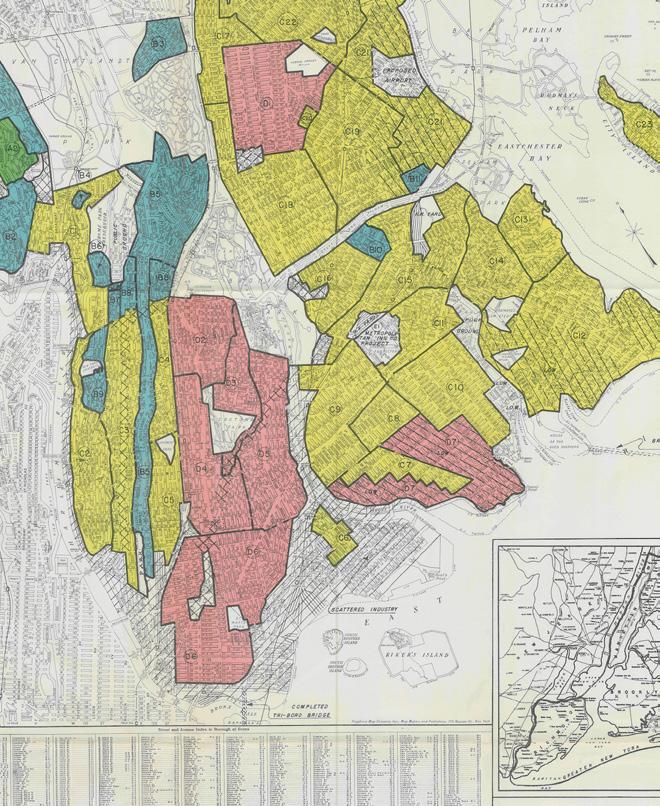

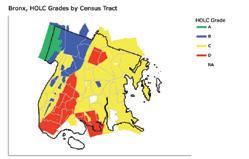

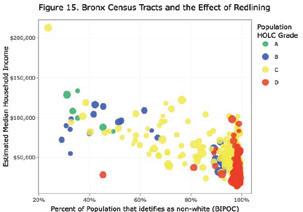

The residents that remained in the Bronx after the construction of the expressway were largely black and brown and their mobility was further constrained by the implementation of racist housing policies and redlining. Redlining was a racist government practice in which the government created maps determining and assigning grades to a neighborhood’s investment worthiness based on race in the late 1930s. The grades were color coded: A was green and “Best”, B was blue and “Still Desirable”, C was yellow and “Declining”, and D was red and “Hazardous”.

The Morrisania neighborhood of the South Bronx was given a D rating and the following remarks were made about the area, “There is a steady infiltration of negro Spanish and Puerto Rican into the area. Population is very unstable and the relief load is heavy. Section is very congested with considerable small business scattered everywhere. One of the poorest areas in the Bronx.” These gradings and remarks about specific neighborhoods and census tracts based off of racist assumptions and stereotypes still impact the area today. (8)

Pollution Advantage is a term coined by professor Christopher W. Tessum to denote the racial disparities between pollution exposure and the consumption of goods and services within the United States. His accompanying report reveals that black Americans are exposed to 56% more pollution than they cause and Hispanics are exposed to 63% more pollution than they cause. However, non-hispanic white people are exposed to 17% less pollution than they cause; this is what the study defines as a “pollution advantage”.(5) This research is tangibly expressed through the environmental health injustices experienced in the South Bronx, which has higher rates of pollution than New York City the Bronx as a whole(6), Asthma rates three times higher than the city average(7), An average life expectancy four years shorter than other parts of the city(7), and a 39% black and 60 % hispanic population(6)

Air pollution in the South Bronx has many sources; emissions from the Cross Bronx Expressway Traffic, Waste Transfer Stations, Peaker Power Plants, and last-mile truck facilities. One of the most visble and symbolic sources of pollution advantage is the Fresh Direct operational facility in Mott Haven. From here, trucks deliver fresh produce to wealthier parts of the Bronx and NYC. However, the air and noise pollution emitted from this vehicle activity is concentrated in the South Bronx, which is also ironically one of the most food insecure parts of NYC; in 2017 only 4% of South Bronx residents eat 5 or more fruit and vegetables a day vs. 11% in NYC. (9)

While the relationship between air pollution and asthma is not fully understood, evidence implies that air pollution can suppress the immune system's ability to differentiate harmless allergens from dangerous viruses or bacteria, causing an inflammatory response when it is not necessary. There is a positive correlation between having low-income and dying from asthma. This can be attributed to a variety of factors, including higher exposure to pollutants in poorer neighborhoods. Consequentially, in the South Bronx neighborhoods of Hunts Point-Mott Haven and High Bridge- Morrisania, asthma-related emergency department visits among 5 to 17 year-olds were nearly 20 times higher than the rates of asthma-related ED visits among the same age group residing in Bayside-Little Neck, a wealthy neighborhood in Queens.(14)

The background context and research detailed above forms the backbone of our secondary research on the historic and ongoing legacy of environmental racism in the South Bronx, with a focus on air pollution’s impacts on respiratory health (see above).

Environmental racism is a critical issue we want to amplify and we also want to acknowledge that history, culture and arts play critical roles in the success of past and contemporary grassroots activism. This juxtaposition is what inspired us to centre the project around creative and collaborative storytelling presented in an audio visual format.

Before developing this design concept, our initial research honed in on the creativity and resiliency that was so critical to the success of the squatting movement during the fiscal crisis of the 1970s and beyond. Our initial site of interest was the Lower East Side, however introductions to Frank Morales, a pastor whose involvement in the squatting movement spanned stints in both the lower East Side and the South Bronx, opened up the geographical scope we considered.

The South Bronx is an important area to focus on, particularly because of its historic neglect and active disinvestment by government officials, but also because of its rich history of creative activism; the Puerto Rican gang turned civil rights organisation The Young Lords took over Lincoln Hospital in 1970 to demand better healthcare for what it described as “a butcher shop that kills patients.” (10) The Young Lords were also active in the squatting movement, which inhabited vacant buildings during an era of rampant evictions and homelessness. They acknowledged that for officials to listen, a radical intervention was required.

While housing is still a pertinent issue, our choice to focus on environmental health stems from the urgency with which we must address the global climate crisis with local solutions that make sure not perpetuate the existing inequities of our current extractive-capitalist system.

In order to emphasize the environmentally triggered health issues faced by South Bronx residents, while ensuring we do not inadvertently reduce them to victims, we adopted a desire-based research framework. This framework, coined by Unangax̂ scholar Eve Tuck, centres on the importance of documenting wisdom and hope alongside loss and despair. Opting to record the oral histories of residents gives them the space to air grievances as well as share positive stories regarding their lived experience in the South Bronx. We also believe that by allowing residents to speak, we get closer to letting them be heard on their own their own terms and with a more creative outlet that acknowledges the quality of self-expression that is so critical to arts and culture.

Once we embarked on developing our project, our primary research method was on-site interviewing. We approached residents in their local parks, described the intention of our project, and asked if they would be willing to participate. Upon their agreement, we asked a set of questions that offered space to describe their background, their neighbourhood, and their lifestyle. We then asked more focused questions depending on if they had asthma and/ or were involved in community activism. We also set up scheduled interviews with with Leslie Vasquez of South Bronx Unite, Melinda Figueroa and her colleague from Bronx GreenUp, and Ammayra Alvarez-Gorgurewicz, a member of a UHAB co-op.

All question sets included inquiring as to what an environmentally healthy and just South Bronx would look like. In doing so, we covered not only present day problems and solutions, but also desires for the future. These should be listened by those with decision making power to gain a deeper understanding of what residents of the South Bronx actually want.

The combination of background and active research we undertook led us to some primary and secondary insights, detailed on the next page.

The goal of this project was and continues to be creating an interactive, educational, and motivational audio map to generate awareness and action on the environmental burdens put onto minortized and marginalized communities like the South Bronx. We have achieved this by recording and making accessible the oral histories of those willing to share the struggles and potential solutions communities have experienced and conceived of in response to poor air quality and intersecting environmental injustices.

Our original goal was for our project to be in collaboration with South Bronx Unite, contributing to their existing work on raising awareness of environmental injustice in the South Bronx and advocating for positive change. Time and resource constraints prevented this from occurring at the outset, however Leslie Vasquez, Clean Air Coordinator at SBU, features as an interviewee in our project. Furthermore, we will be in communication regarding how their work on developing a similar oral history map might take inspiration from, and build on our existing work. We are also in communication with South Bronx Unite and Leslie about how our story map may be embedded onto their organization’s website.

Primary Methods:

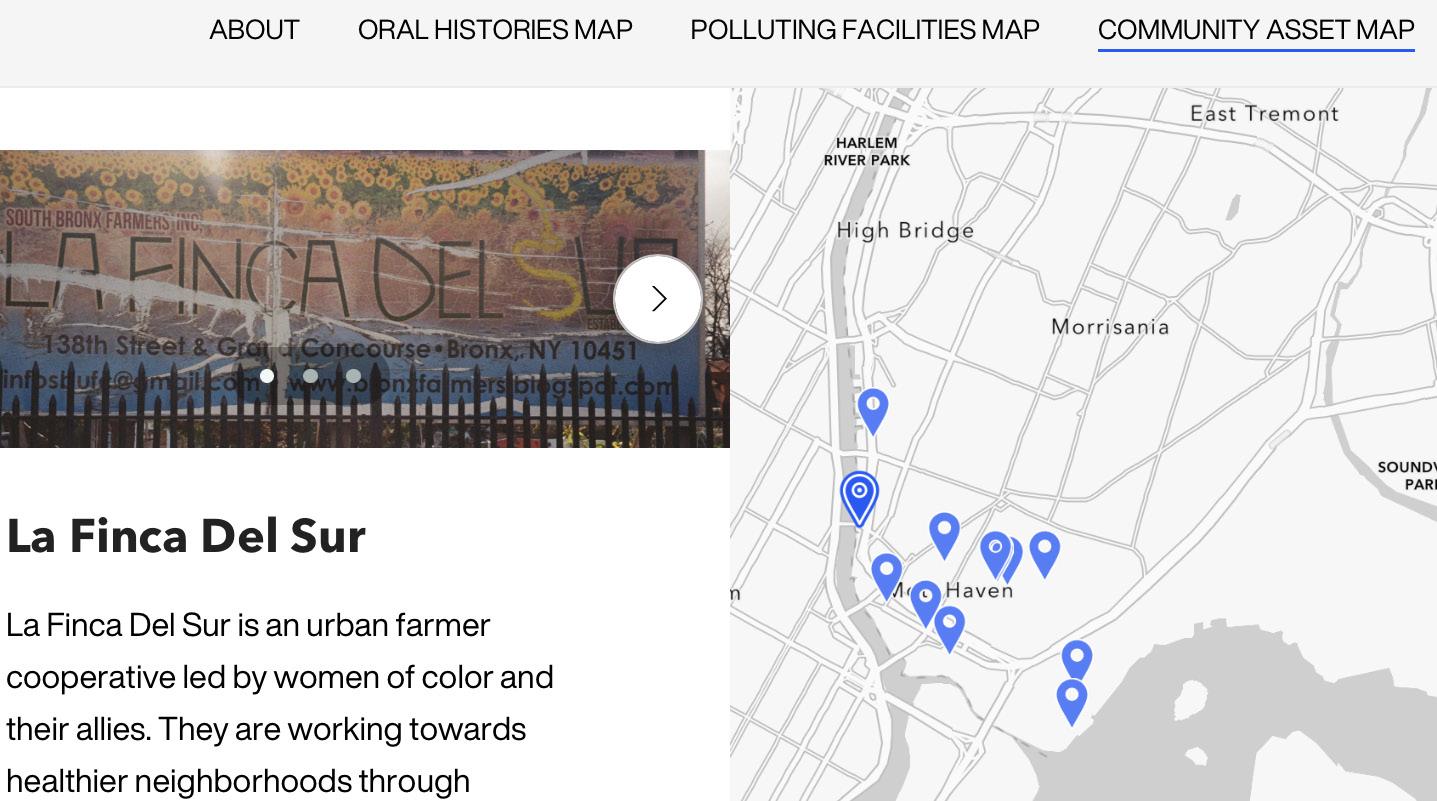

- Site visits to South Bronx community events; Finca del Sur Community Composting + the annual South Bronx Community Banquet.

- Interviews with residents + community activists (see right).

- Video and photographic footage of the area and of residents.

Upon our first visit to the South Bronx, we were confronted with the sheer number and concentration of polluting facilities and truck routes juxtaposed with a stark lack of public green space. This insight was corroborated by further research and our own data analysis and visualization.

We also recognized that the current situation was not created in a vaccum but was an extension of racist housing policies such as redlining and zoning, that turned the neighborhood into a manufacturing area where black and brown people lived but were prevented from buying homes and building generational wealth due to high mortage rates in "Hazardous" areas. This was part of a larger history of disinvestment in the South Bronx

The fact that the best-kept and most beautiful parks we came accross were lots revitalized and tended for by residents rather than city employees was a reminder that grass-roots engagement and activism is the lifeblood of the community. Not only do these parks exist as green space for residents to have some respite from the concrete and smog, but also as venues for all sorts of educational, cultural, and artistic events.

Secondary Methods:

- Data visualization + analysis

- Scholarly + news articles (refer to appendix for more inforn).

- Information from South Bronx-based organizations (see stakeholder diagram).

Futher desk research and operational researvh such as interviews with South Bronx residents revealed that where there is investment in the neighborhood, it benefits private entities. Conversely, this investment has a negative impact on residents by way of construction and increased business-related traffic increasing pollution. As Leslie Vasquez notes, "residents pay for the area they live in with their health."

Despite the issues residents expanded on in their oral histories, all of them had a great pride for the culture of the South Bronx, citing food, fashion, and - critically - community. It is in part due to this pride that they want to see other people, including those with decision-making power, recognize what the South Bronx already has to offer and invest in the community by making it liveable for current residents.

To articulate the existing challenges and preferred outcomes with regards to envrionemntal health in the South Bronx, quotes presented here have been pulled from oral histories that express both the difficulties and the desired solutions to these issues that residents envision. Our role in achieving the preferred outcomes is to help raise awareness of environmental justice and health issues in the South Bronx. We aim to contribute to the existing arsenal of evidence that makes an unequivocal case for increased investment in community based solutions instead of pandering to dislocated corporate interests.

"The South Bronx has one of the highest asthma rates in the whole country. And that is due to the fact that we have so much polluting infrastructure concentrated in one single area. So the residents that live in Mott Haven and Port-Morris, are very prone to having some kind of respiratory illness."

"I would say we have really bad air quality. I was born with asthma, and I'm pretty sure it's because I was born in the South Bronx. We do have noise pollution, but also extreme heat, sometimes."

"When you think about the 0.6%, of green space funding that we have for the whole city, they're not going to prioritize the South Bronx, because they don't seem they don't see that as something that will cause a direct impact in our community. And they don't see that our community is in dire need of change, and funding and resources."

"I know that we can't stop traffic, we need to have people come through we have businesses, I understand that, but it seems very congested in this area."

"I feel like there could always be more [green spaces]. There's still like places that are landfills and, you know, it really just takes people starting the movement to you know, complete the vision. I think it should also be, you know, a safe environment for kids to just run around and play."

"we want to be able to provide that data and justify to legislators and to larger agencies who do provide this funding, so that we can be prioritized soon, because that needed to be happen yesterday."

"An environmentally just South Bronx looks like more green spaces are open, open spaces for people to be just be able to get away from the noise, a lot of the noise that comes from traffic."

"You know, if you're gonna come here and you know, build a high rises and whatnot, you know, make it fair, you know, have something there for you know, the people that do live in the area."

We used a free version of Story Maps to build our website. It offered the opportunity to add text, audio, and visual media to maps of the South Bronx - context that was crucial to the success of our project. However, we were limited by the free features. For example, ideally we would have created a map with color coded pins that showed the location of oral histories, polluting facilities, and community assets all in one place to provide a more comprehensive context of the area. Instead, we have three maps for each aspect. Tabs at the top of the website page will guide you to each section of the website; detailed below.

Our 'About' page states who we are, the conditions of our project i.e. part of a graduate class, and w

The 'Oral Histories Map' provides accounts from South Bronx residents who have experienced and/or are working to combat the effects of environmental racism in the South Bronx, with a fous on asthma and respiratory health. Each pin identifies the onsite location of our interview or where the storyteller lives. Each story is accessible as an audio file and a transcript, and includes specific quotes and a trasncript summary. Our intention is for this qualitative data to add a deeper layer to the data and statistics organizations use to make their case for investment in the existing communities of the South Bronx. We also want these stories to offer non-South Bronx New Yorkers the chance to hearfirst-hand accounts of the injustices felt there, and spur them to join in the action. Finally, we would like for residents hear their story and see it as connected to the stories of other residents.

The above map marks the polluting facilities that are concentrated in the South Bronx. Clicking on a pin will provide more information on that facility. It is for residents and greater NYC to better visualize the high concentration of pollutants in the area

The community assets map offers a visualisation of where public space is located and includes proposals for how community organizations have envisioned public space for the benefit of residents. It also serves to emphasize the ratio of public space to polluting facilities in the area. This is an instance where layering the maps would have been particularly useful.

We will continue to accept oral history submissions after the completion of our class project deadline. We choose to do this, acknowledging that for this resource to be useful to the community, it should be updated and remain accessible. The form, partly pictured on the right, provides detailed instructions on how to submit an oral history to our site.

Our method of outreach was to put posters around the city (see right), which would guide those interested to the site via QR. Visitors have the opportunity to engage in direct action. Direct Actions are recommended by community activists we speak to.

This project was a steep learning curve, we were engaging directly with an area with which we had no prior familiarity - all project members had been in New York less than a year.

We were aware that this lack of an existing relationship to the land and to the community was a hindrance. For example, getting enough people to tell us their story was difficult without having existing contacts, especially as there is a valid mistrust that residents have of people outside the South Bronx coming in to glean information without following through.

Furthermore, the South Bronx is majority Latinx/Hispanic and no one on our team speaks proficient Spanish, limiting our capacity to interview Spanish speakers.

All this boils down to our main limitation, which was time. If we had more time, we would have arranged to collaborate with a Spanish speaker who could serve as an interviewer. We also would have developed a deeper relationship with the community through attending events and getting to know the people and place better.

Furthermore, we were quite limited in scope focusing primarily on asthma as an outcome of environmental racism in the South Bronx and how that is an outcome of lack of public space and high concentrations of air pollution. However, there are many more intersecting issues at play - such as food insecurity and housing instability - that we might have explored further with more time.

Nevertheless, this project was a successful pilot and a proof of concept for how mapped oral histories might be used in the South Bronx and elsewhere to highlight environmental injustices and get closer to better understanding and thus tackling them.

We are in conversation with South Bronx Unite to explore how they might adapt our Story Maps to do a similar oral history map, as a qualitative component to the air pollution data they are collecting from monitors placed at strategic locations in the South Bronx.

After the Winter Break, we will add some more stories recorded over zoom from activists within the South Bronx community. We will also continue to update the oral history map as we receive oral history submissions.

mychal johnson + leslie vasquez, sbu siddarth motwani, bronx river alliance nybg bronx green up

interviewees: leslie vasquez, andrew + luna, ammayra alvarez-gorgurewicz, melinda figueroa, joann dicent, anonymous nybg employee

1. Partida, R. (2023, December 11). The South Bronx’s economy grows amid challenges. Mott Haven Herald. http:// motthavenherald.com/2023/11/29/the-south-bronxs-economy-grows-amid-challenges/

2. Scientists and community leaders seek to clear the air in the South Bronx. Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health. (2023, October 3). https://www.publichealth.columbia.edu/news/scientists-community-leaders-seek-clearair-south-bronx

3. The cross bronx expressway. SEGREGATION BY DESIGN. (n.d.). https://www.segregationbydesign.com/the-bronx/thecross-bronx-expressway

4. Plan to transform the cross bronx expressway gains momentum. Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health. (2022, October 3). https://www.publichealth.columbia.edu/public-health-now/news/plan-transform-cross-bronxexpressway-gains-momentum

5. Tessum, C.W.; Apte, J.S.; Goodkind, A.L.; Muller, N.Z.; Mullins, K.A.; Paolella, D.A.; Polasky, S.; Springer, N.P.; Thakrar, S.K.; Marshall, J.D.; et al. Inequity in Consumption of Goods and Services Adds to Racial–Ethnic Disparities in Air Pollution Exposure. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019

6. Grocery Depot brings increased traffic to the South Bronx. Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health. (2022, October 3). https://www.publichealth.columbia.edu/news/grocery-depot-brings-increased-traffic-south-bronx

7. Public health equity. SOUTH BRONX UNITE. (n.d.). https://www.southbronxunite.org/public-health-equity

8. Ortigas, R. (n.d.). What exactly is redlining?. Inequality in NYC. https://rayortigas.github.io/cs171-inequality-in-nyc/

9. NYC Food Policy Center (hunter college). (n.d.). https://www.nycfoodpolicy.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/ FS10567_2017.pdf

10. Narvaez, A. A. (1970, July 15). Young Lords Seize Lincoln Hospital Building. The New York Times. https://www. nytimes.com/1970/07/15/archives/young-lords-seize-lincoln-hospital-building-offices-are-held-for-12.html

14. Disparities among children with asthma in New York City. New York City. (n.d.). https://www.nyc.gov/assets/doh/ downloads/pdf/epi/databrief126.pdf

In the vibrant tapestry of New York City, a pressing concern often eludes the spotlight—the insufficient availability of accessible public spaces tailored to the diverse needs of its communities. This oversight is further compounded by a lack of neighborhood amenities that can uplift localities without triggering displacement. Long Island City, Queens, emerges as a microcosm of this overarching problem, grappling with an undue share of social and environmental challenges. Here, an evident scarcity of parks and green spaces persists, despite attempts to address the issue through the development of new open spaces south of the Queensboro Bridge. The rapid densification of the neighborhood, however, brings forth a new challenge—the burgeoning population exerts significant pressure on an already inadequate park system. To exacerbate matters, a concentration of New York City’s elevated infrastructure in Queens and the Bronx, home to a substantial percentage of the city’s Black and Brown population, manifests as elevated highways and transit lines that carve through communities, creating spaces characterized by dim lighting, noise, and an overall undesirable atmosphere.

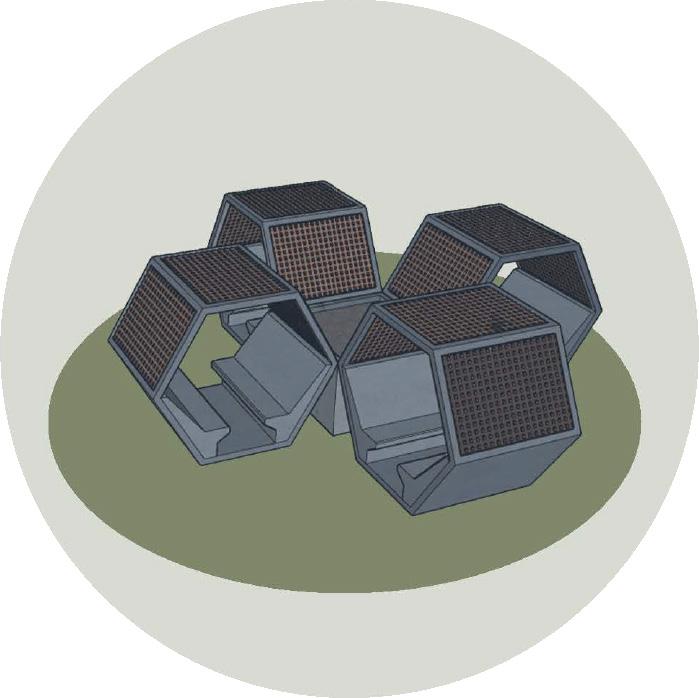

Beneath the imposing structures of elevated highways and transit lines lies an unnoticed reservoir of potential—underutilized public spaces waiting for transformation. Globally, initiatives like the Design Trust for Public Space’s “Under the El” project in NYC have embarked on addressing this very challenge. Simultaneously, the impactful efforts of grassroots organizers and organizations in New York City and the broader United States underscore the necessity for a resource tailored to community-based initiatives. Hence, our primary objective is to craft a comprehensive resource, providing grassroots organizers with insights into the untapped potential within seemingly lifeless and wasted spaces. T

his Adaptable Toolkit is a companion piece to our research booklet, a practical guide designed to empower grassroots organizers and smaller community-based organizations with the tools and insights needed to reimagine underutilized spaces under elevated infrastructure. Born from the culmination of extensive research and a passion for fostering inclusive, community-centric spaces, this toolkit serves as a beacon for those seeking to catalyze positive change for these spaces at a local level. The toolkit is not merely a collection of theoretical concepts but a practical road map grounded in real-world examples and case studies from around the globe.

As we explore the nuances of community-led initiatives, our toolkit introduces a strategic framework for envisioning and implementing pilot projects. It is not a prescription but a versatile instrument, offering a dynamic array of concepts, definitions, and practical considerations. It serves as a catalyst for dialogue, encouraging collaboration and community-driven decision-making. Through prompts, printable materials, and valuable insights, it equips you with the knowledge to navigate the complexities of the site context, stakeholders, jurisdiction, rules, and guides.

As you embark on this transformative journey, may this toolkit serve as your compass, guiding you through the intricacies of community engagement, sustainable design, and the reclamation of spaces that hold the promise of new legacies.

We began our secondary research by delving into some of the community assets that we had touched on in the first research phase, beginning with a deeper exploration of community gardens. Pulling from our experiences visiting community gardens in several of New York’s boroughs and conducting additional research on the origins of the community garden movement in the 1970s, we realized that community gardens serve as a quintessential example of the re-imagination of overlooked spaces into valuable community assets that we were seeking. As such, we used mapping resources from the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation to explore the distribution of community gardens and other green spaces across New York City’s boroughs, noting a distinct lack of both in certain parts of the Bronx and Queens.

We continued by examining additional models wherein underutilized or unlikely spaces had been re-imagined and transformed, focusing on instances which seemed to align with the values and practices of community garden stewardship. This exploration led us to discover initiatives like the NYC Department of Transportation’s Open Streets and Plaza Programs. These efforts strive to foster safer, more accessible, and community-centric public spaces, centering community engagement and neighborhood activation in their approach. At this point, we came across a project entitled “Under the Elevated,” a joint initiative by the Design Trust for Public Space and the New York City Department of Transportation completed in 2015.

The groundbreaking study undertook the substantial task of mapping and taking an inventory of all elevated transportation infrastructure in New York City. Ultimately, they found that in a city that seems to be chronically lacking space, there are in fact nearly 700 miles of elevated transportation infrastructure, and subsequently, as many miles of underutilized space below. Comprising 40% of New York’s subway lines, including numerous rail routes, these elevated structures were primarily built during two key periods: elevated rails during the late 1800s and early 1900s, and major arterials like highways and expressways from the 1930s to 1960s. These construction endeavors, largely driven by private enterprises and federal investments, were expedited without community input. fa

The advent of elevated railway systems and infrastructure in cities like New York brought about a paradoxical existence—where bustling transportation routes above juxtaposed with life below, shaping an environment rife with contrasting realities. These elevated tracks inadvertently left a mark on the urban landscape and the communities they traversed, disrupting communities, plunging streets into darkness, dropping debris and soot, and posing imminent safety hazards. The remnants of this historical imposition, the physical dangers of navigating neglected spaces beneath elevated infrastructure, as well as the social implications of communities fractured by expressways, continue to influence the urban fabric of contemporary NYC, underscoring the challenges faced by communities dwelling beneath such infrastructure and the enduring impact on the city’s social and cultural tapestry.

The realization of untapped potential lying within the spaces under elevated infrastructure presents a compelling opportunity for the City of New York. In the hectic landscape of NYC, a pervasive concern that often remains inadequately addressed is the unequal access to quality public spaces that genuinely cater to the diverse desires of local communities, as demonstrated by the stark discrepancies in the distribution of community gardens, parks, and open spaces in general across the city.

Having looked into the dynamics and impact of community gardens, and having extensively studied the Under the Elevated project, we decided to expand the scope of investigation to include additional case studies of “El-Space’’ projects, both within and beyond the New York City context. By developing a set of lenses through which to examine each case study, we sought to dissect the critical factors contributing to the success of el-space projects and distill valuable insights that could inform and inspire similar endeavors.

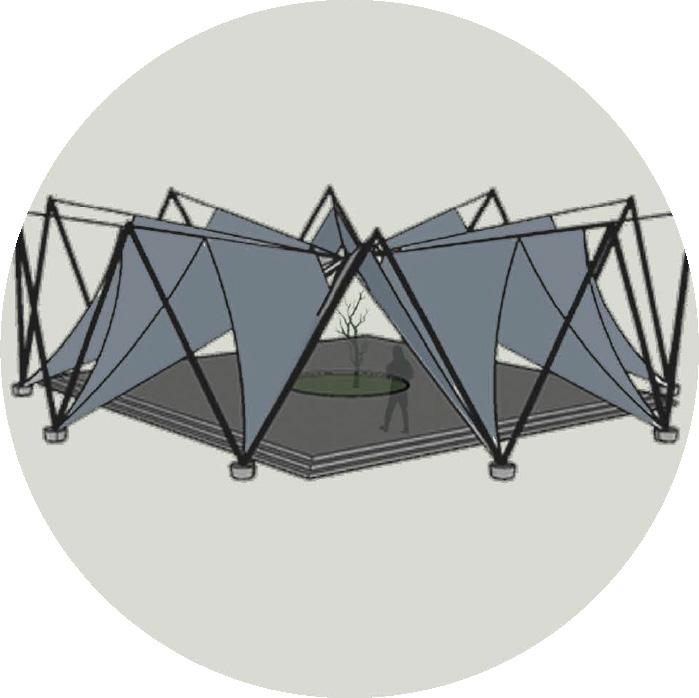

In the multifaceted journey of our project, we traversed distinct phases to systematically address the challenges and opportunities inherent in reimagining spaces under elevated infrastructure. Our initial phase involved meticulous research, identifying gaps in community assets across New York City, exploring the potential of underutilized spaces, and honing in on a specific target audience. Moving into the second phase, we delved into case studies through the lenses of community engagement, thematic focus, and actionable insights. These insights were then harnessed to formulate and refine a pilot project, with a strategic selection of the pilot location setting the stage for the subsequent steps.

As we transitioned to the third phase, community engagement took center stage. Our team conducted immersive sessions at the pilot location, fostering a deep understanding of the community's needs. From this foundation, multiple design interventions were conceptualized to breathe life into the underutilized spaces. The culmination of our efforts materialized in a comprehensive research booklet, a tangible output showcasing the wealth of insights gathered throughout this process.

In the final phase, our focus shifted to existing toolkits, identifying gaps and deficiencies. We undertook the task of crafting a toolkit designed to foster ethical and inclusive community engagement and design. This toolkit stands as a versatile resource, featuring adaptable, printable materials tailored for use by individuals, public agencies, and community organizations. Through these well-defined phases, our project seamlessly progressed from exploration to tangible outputs, with each stage contributing to a holistic approach in reimagining spaces beneath elevated infrastructure.

"Under and Untapped" emerged as a solution to New York City's dearth of accessible open spaces, offering a toolkit designed to empower community-based organizers. At its core, the initiative strategically utilizes the underutilized spaces beneath elevated transportation infrastructure.

Central to the project is a commitment to ethical community engagement, emphasizing inclusivity and authenticity. The toolkit becomes a medium for communities to actively participate in the revitalization process. This approach goes beyond mere physical revitalization; it fosters a sense of community ownership and connection.

By targeting existing infrastructure, the initiative not only maximizes impact but also promotes environmental sustainability. The toolkit serves as a comprehensive resource, equipping organizers with practical models and detailed design guidelines.

The initiative stands for community-driven revitalization, offering a practical and ethical blueprint for organizers seeking to make a meaningful impact on the urban landscape.

"Under and Untapped" encountered practical limitations, primarily constrained by time and resources. The project faced challenges in engaging diverse communities, struggling to fully understand and incorporate various perspectives due to limitations imposed by time constraints.The project team, working within the constraints of academic timelines and resource limitations, found it challenging to establish deep connections with diverse community groups.

Our goal is to develop a versatile toolkit for creating equitable and usable spaces beneath elevated infrastructure in New York City. This comprehensive resource will be adaptable for use by various organizations, empowering community-based groups, individuals, and public agencies. By offering flexible strategies, guidelines, and case studies, we aim to democratize the process of revitalization. The toolkit's design prioritizes inclusivity and tailoring solutions to diverse community needs, promoting equity in urban development. Ultimately, we aspire to catalyze collaborative efforts, fostering a more vibrant, inclusive, and user-friendly urban environment across different neighborhoods in the city.

Infra-Space 1 is a pilot project led by the Massachusetts Department of Transportation (MassDOT) as part of a statewide initiative to revitalize areas beneath elevated highways. These spaces are often characterized by inaccessibility, darkness, noise, and a disruptive impact on the urban fabric. The primary goal of the project is to transform these neglected areas by introducing multimodal connections, enhancing safety and comfort through new uses and lighting, and incorporating significant environmental improvements.

Infra-Space 1 showcases a high level of community engagement by addressing detrimental characteristics through participatory design. The project’s objective is to repair the urban fabric as a result of community input, ensuring that multi-modal connections, enhanced safety, and innovative design solutions align with the needs and aspirations of the local residents. The inclusion of public programming spaces in maintenance further highlights a commitment to fostering community-driven transformations and creating spaces that resonate with the people who use them.