ARCS

Community-engaged

Phase

WHERE

ARCS

Community-engaged

Phase

WHERE

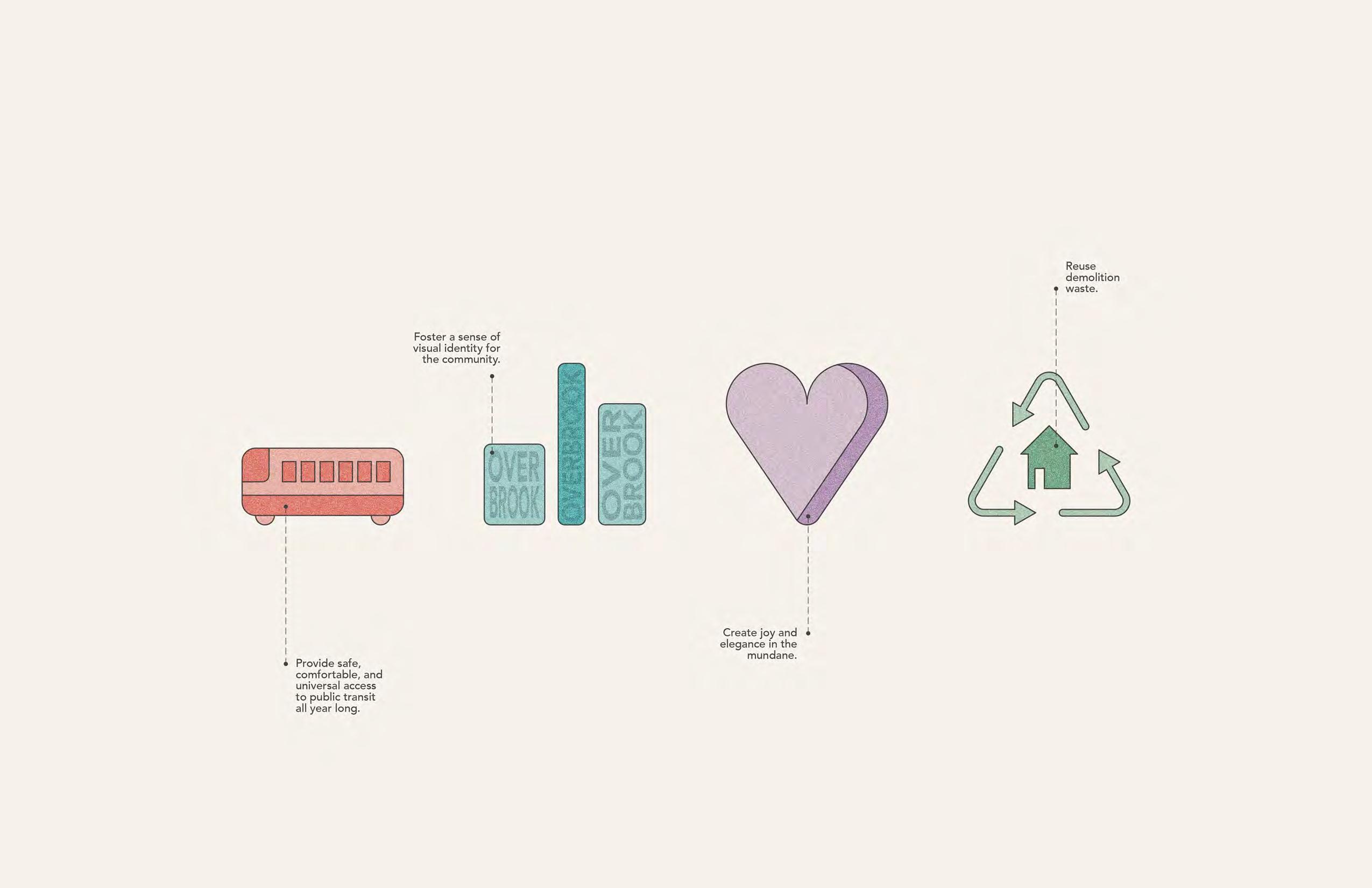

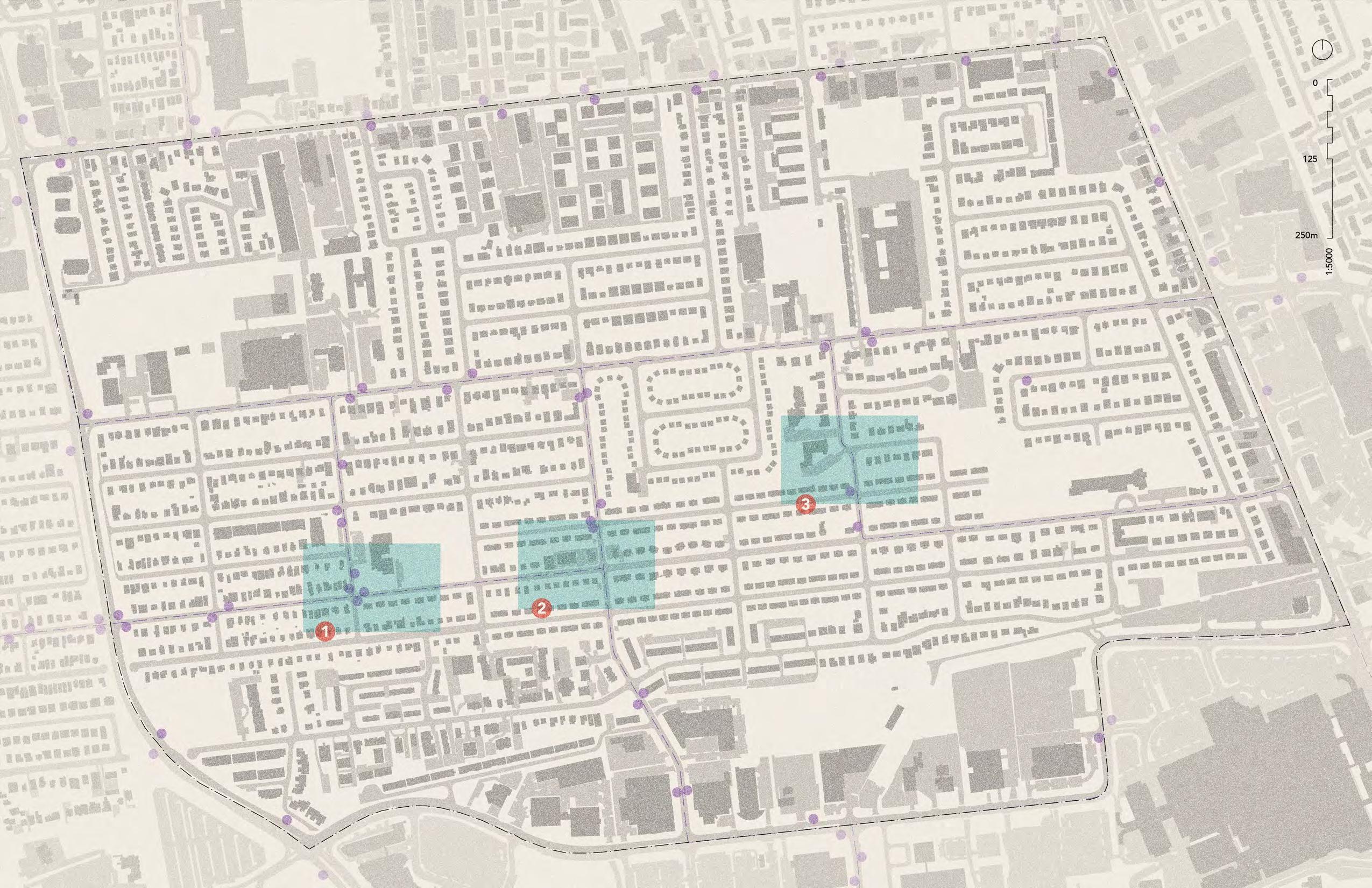

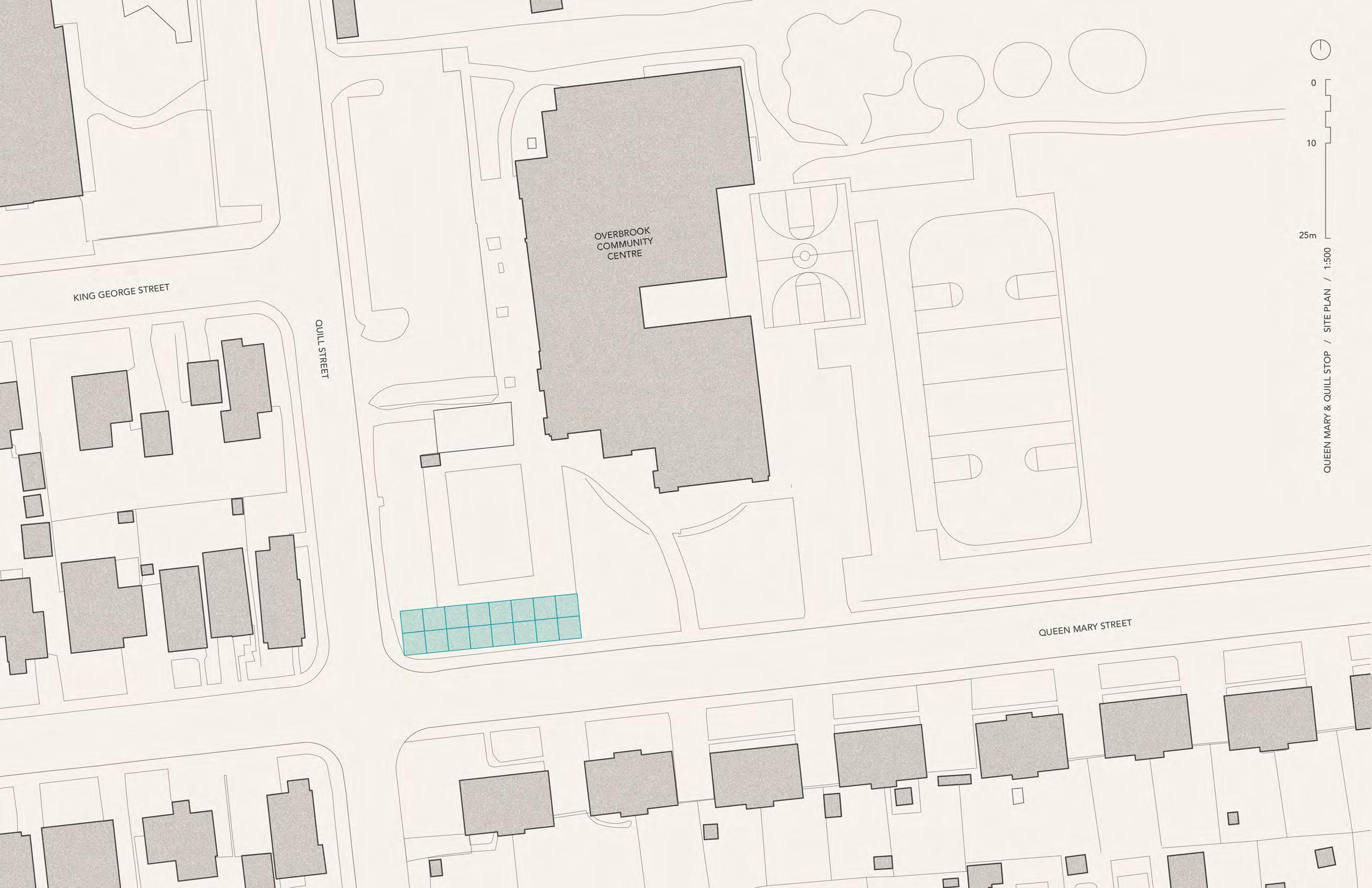

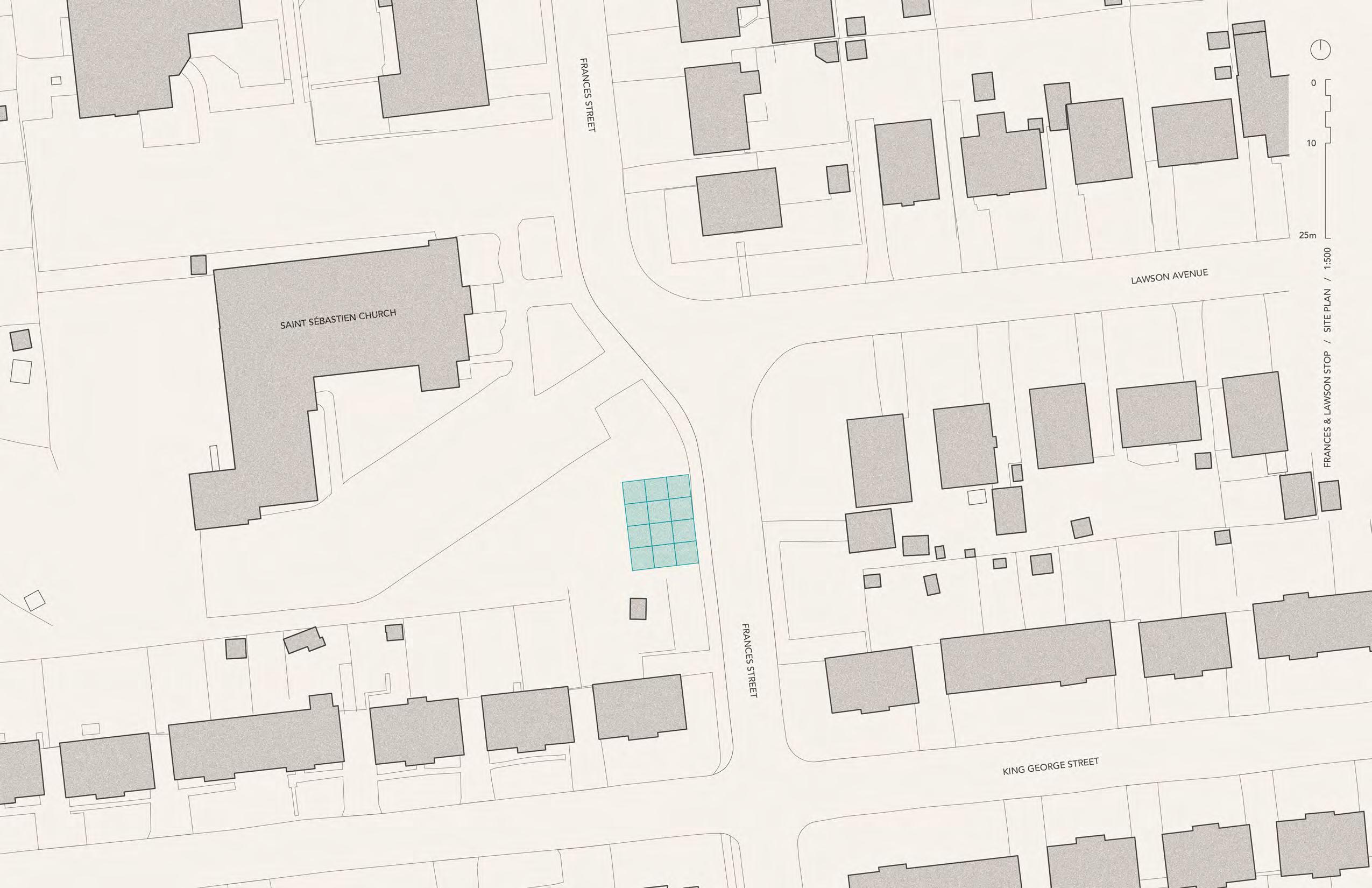

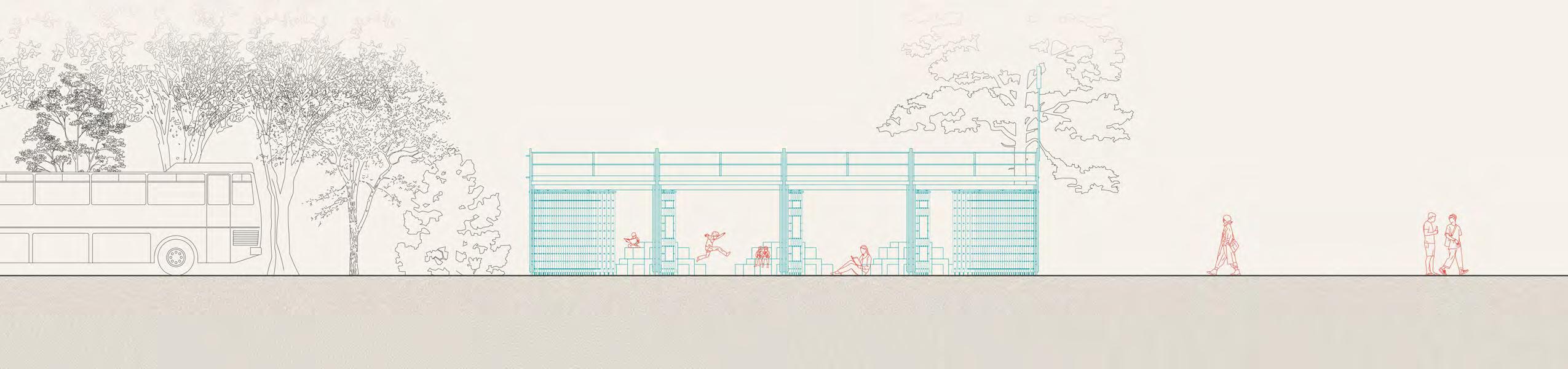

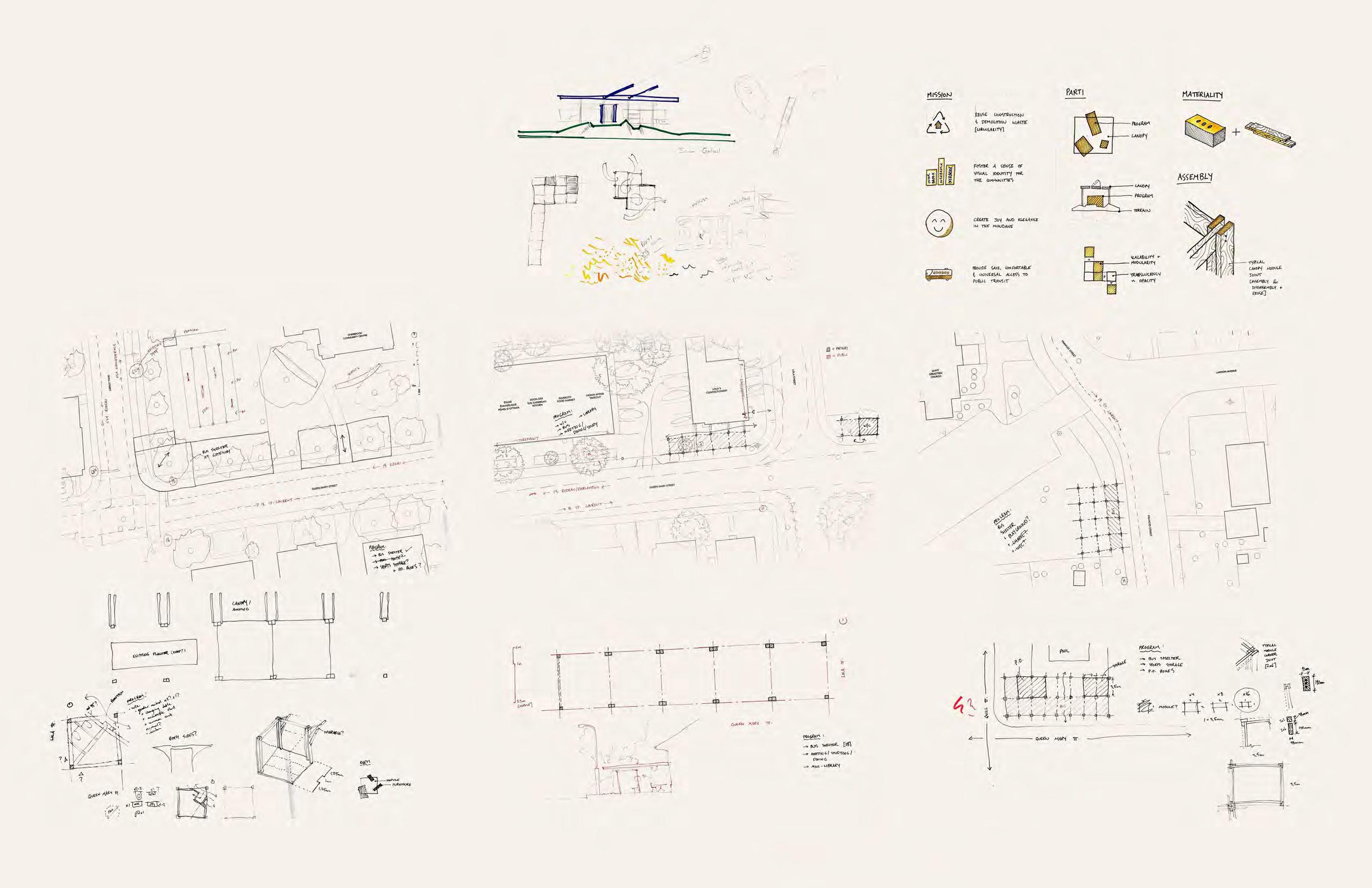

Following the research, storytelling, and documentation that took place in Phase I, the ease of access for Overbrook residents to Ottawa’s public transit network certainly stood out as a lacking service. The community is served primarily by the 18 and 19 routes, as well as several school routes, which use the city’s buses but are reserved for students, mornings and afternoons. Overbrook sits in an interesting spot in the city—just across the Rideau River from the downtown core and near a large transit hub like the St. Laurent Centre. However, its connectivity to the rest of the city leaves much to be desired, and its residents’ must still rely on cars for transportation, especially in the colder months.

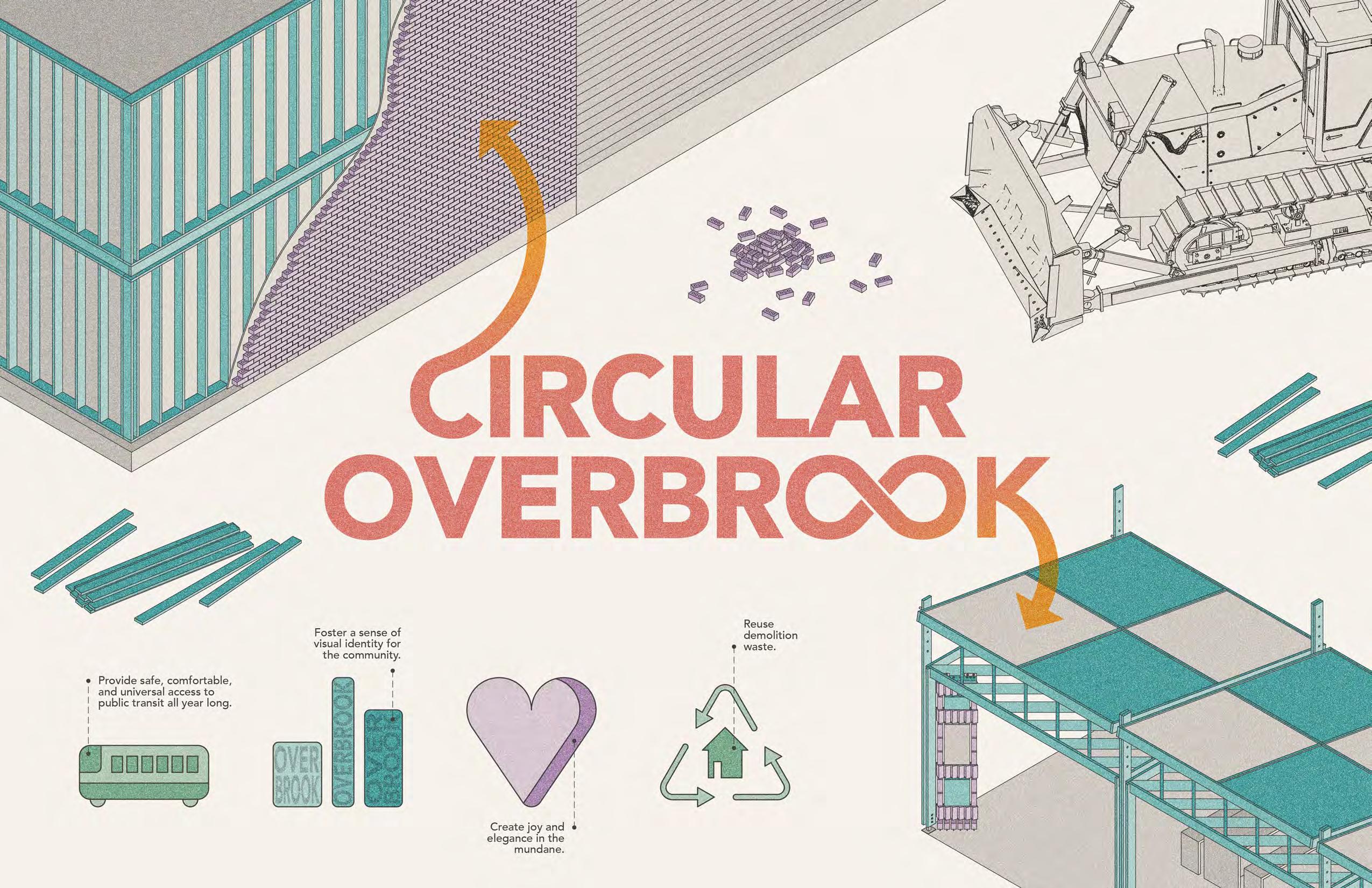

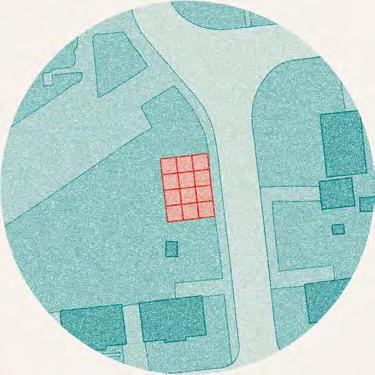

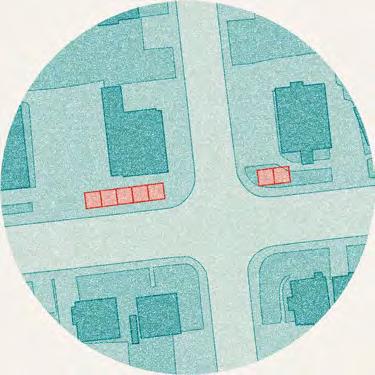

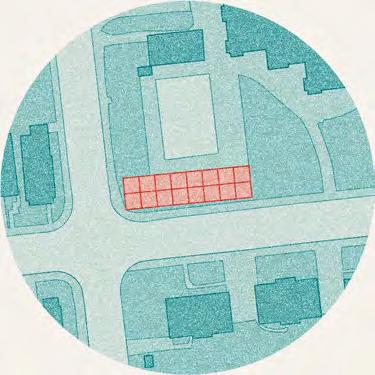

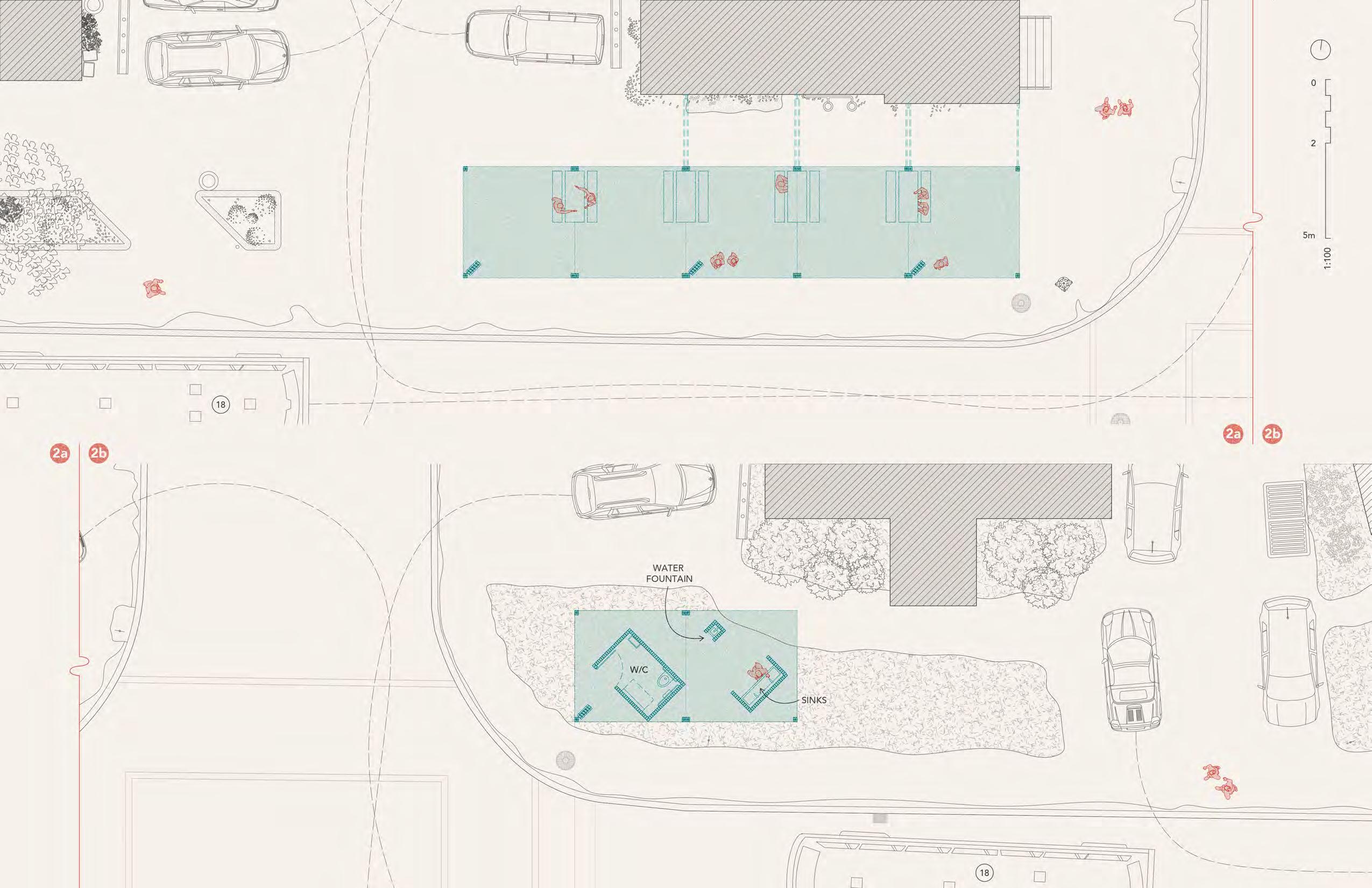

Circular Overbrook aims to make transit more accessible to residents of the community with an overhaul and expansion of its bus shelters. In addition, the project seeks to create a consistent, unique and recognisable visual identity for the community, setting it apart from other neighbourhoods of Ottawa.

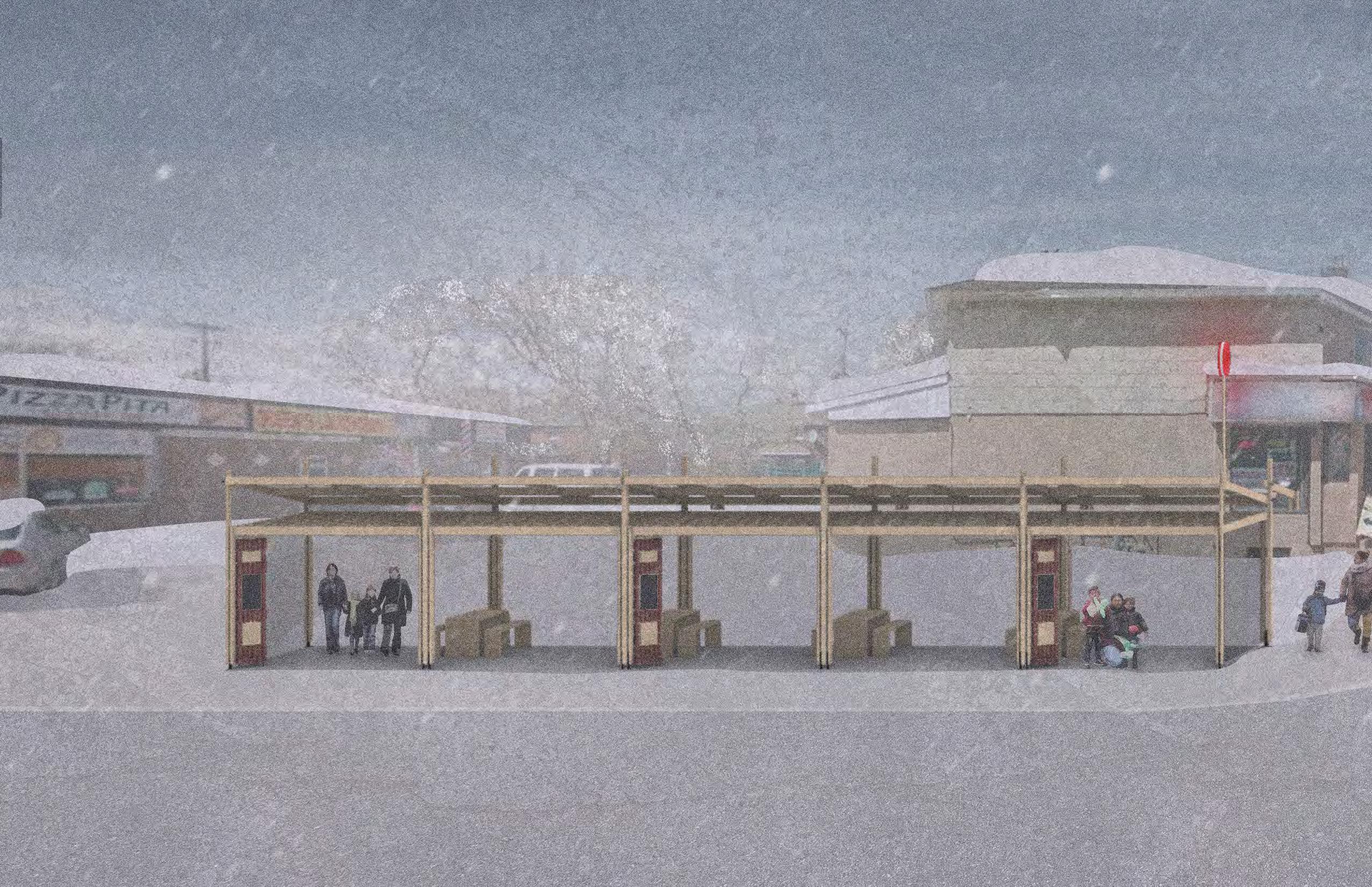

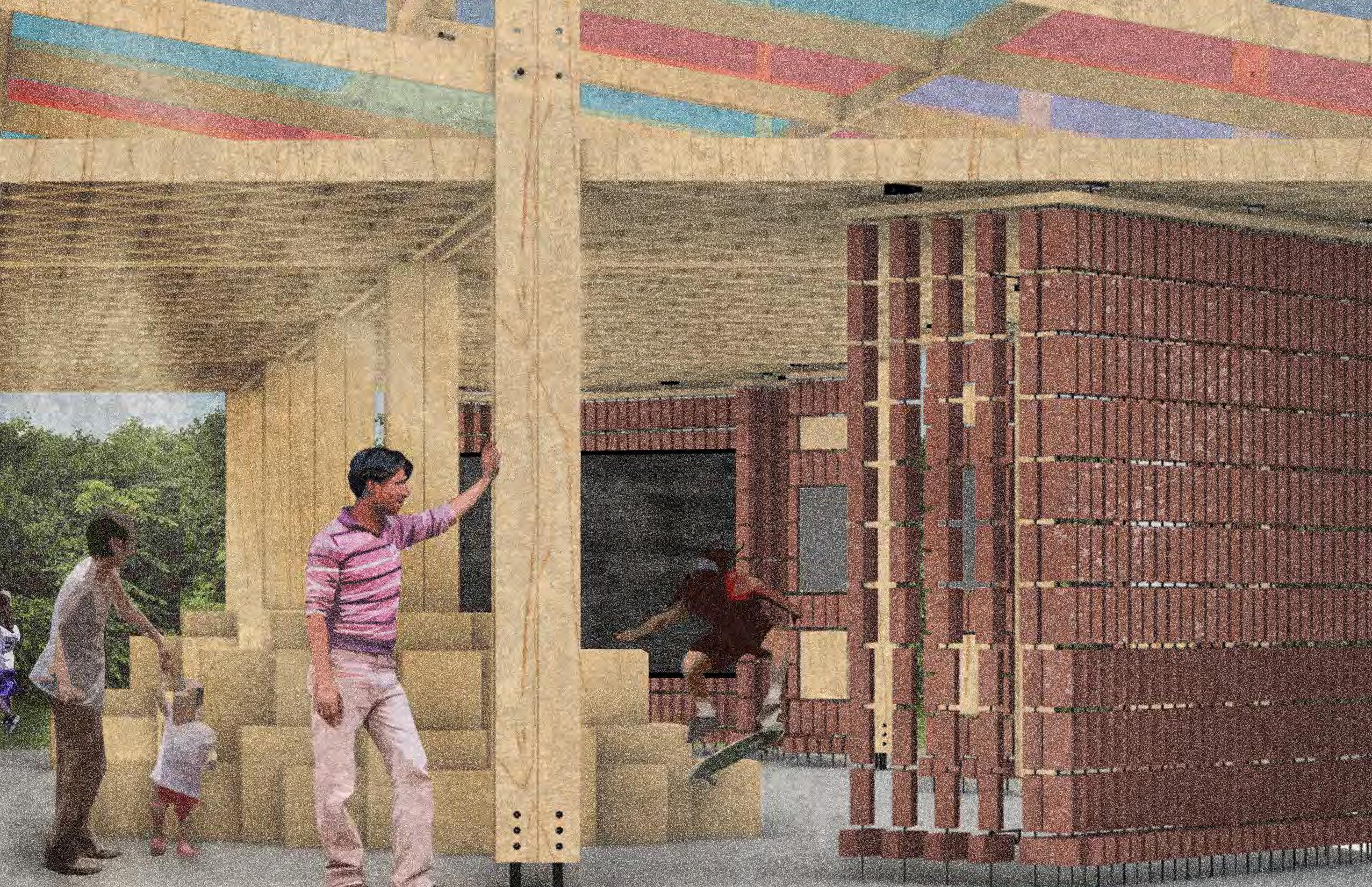

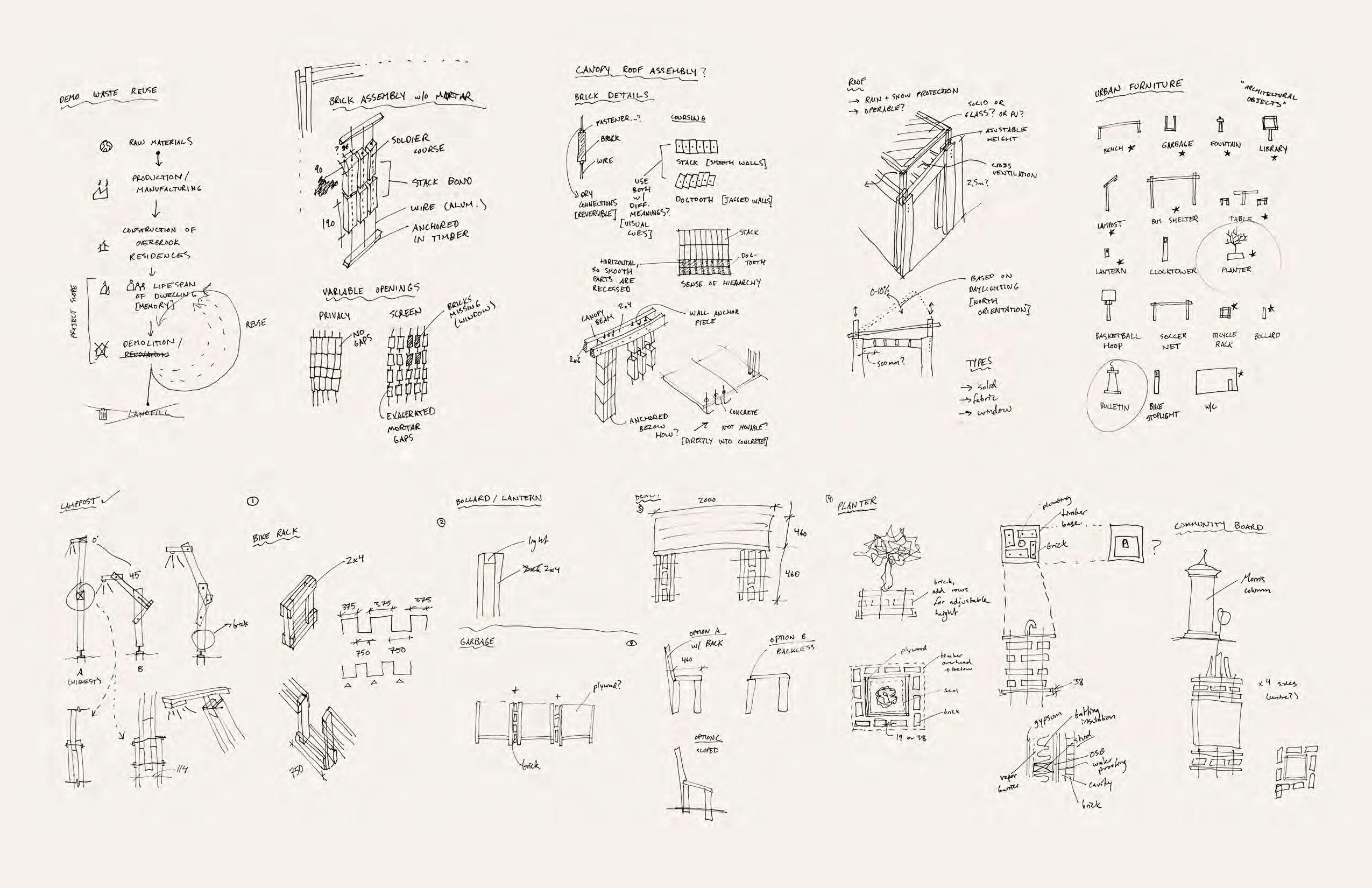

Overbrook is currently undergoing a gradual gentrification and densification, with countless new builds being completed after the partial or complete demolition of existing houses. These former dwellings serve as a palette of materials for the project: timber and brick. (For instance, there is currently an active application to the City to expand four OCH duplexes into quadruplexes on Prince Albert Street, stripping its four façades of all their bricks in the process.)

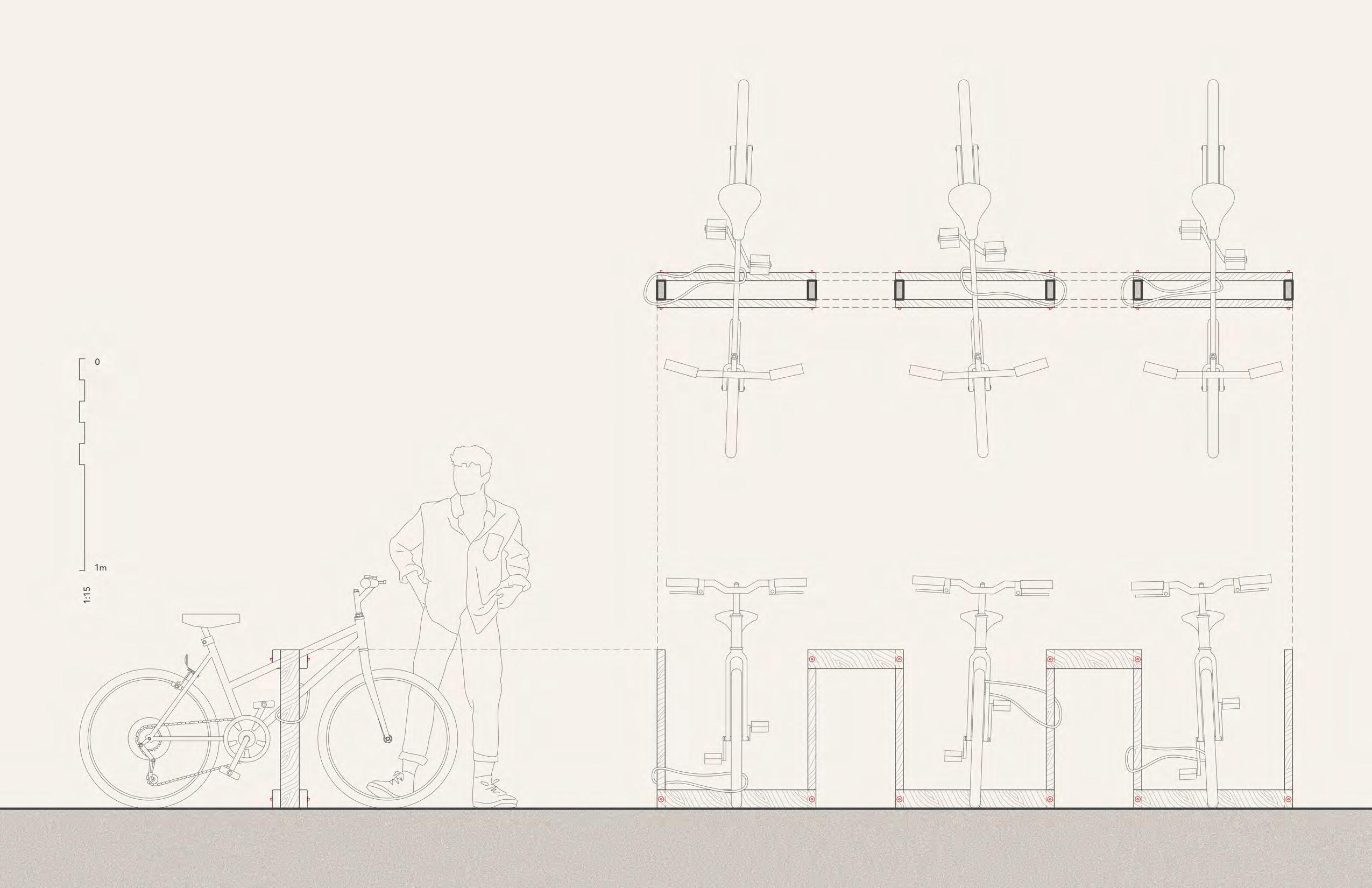

Circular Overbrook seeks to create a framework in which demolition and renovation waste is recuperated to be reused in the creation of small-scale interventions interspersed throughout the community. The project, veering away from a single intervention tied to one site, is instead an act of lowercase “a” architecture— ephemeral, and built for adaptivity, disassembly, and reassembly. In addition, it introduces circular principles to the micro-economy of Overbrook, and by extension, to the economy of Ottawa.

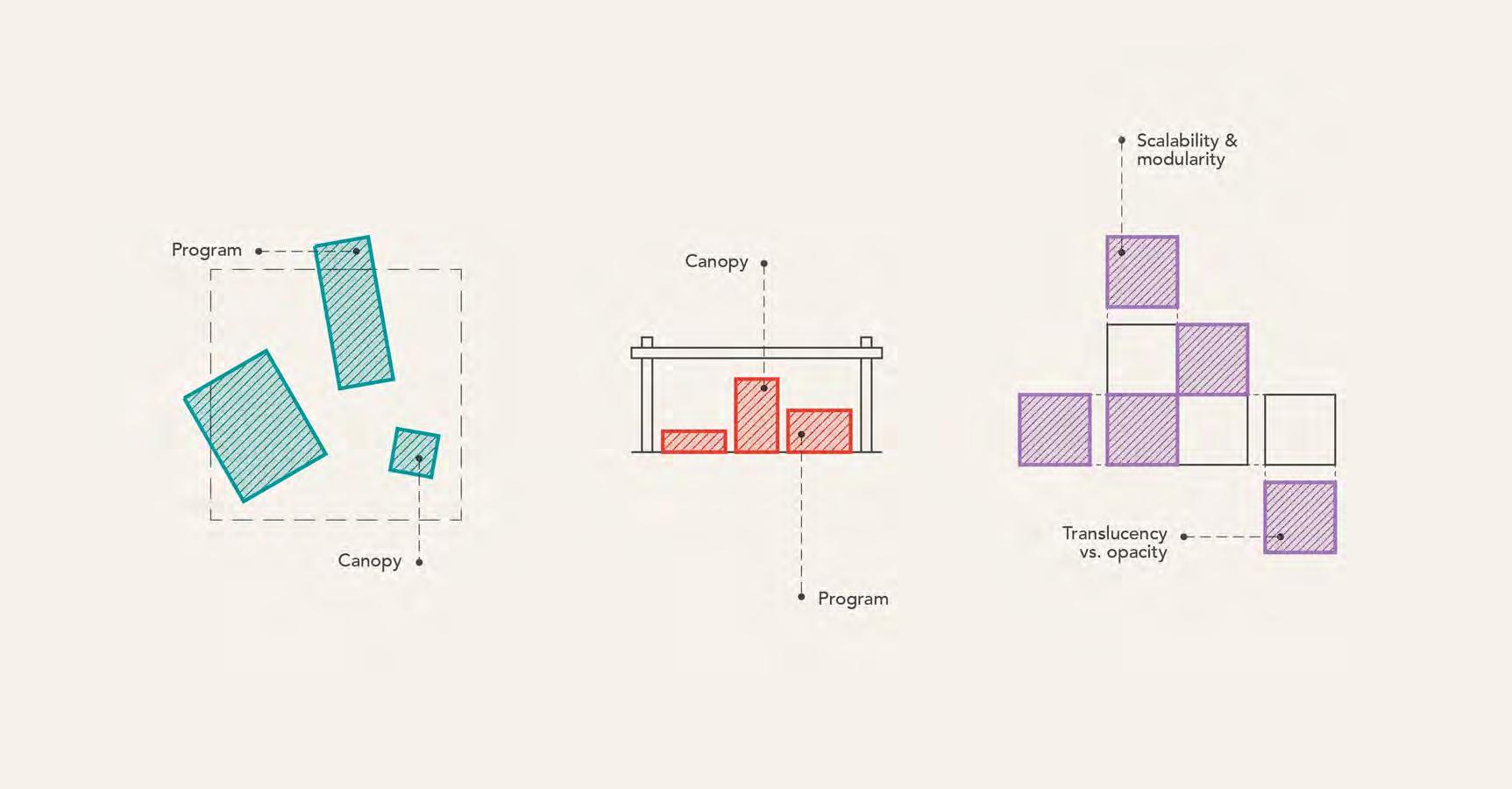

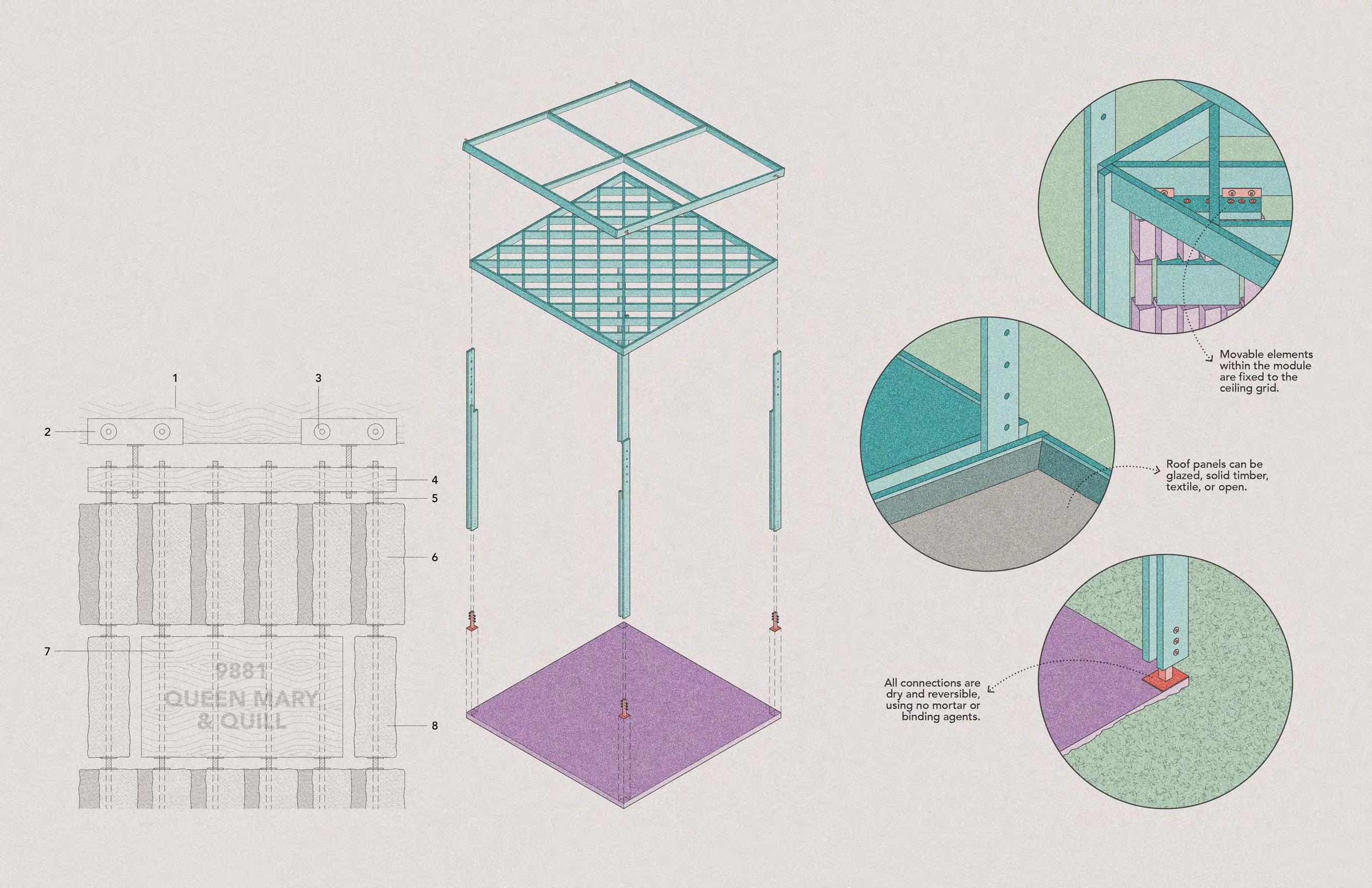

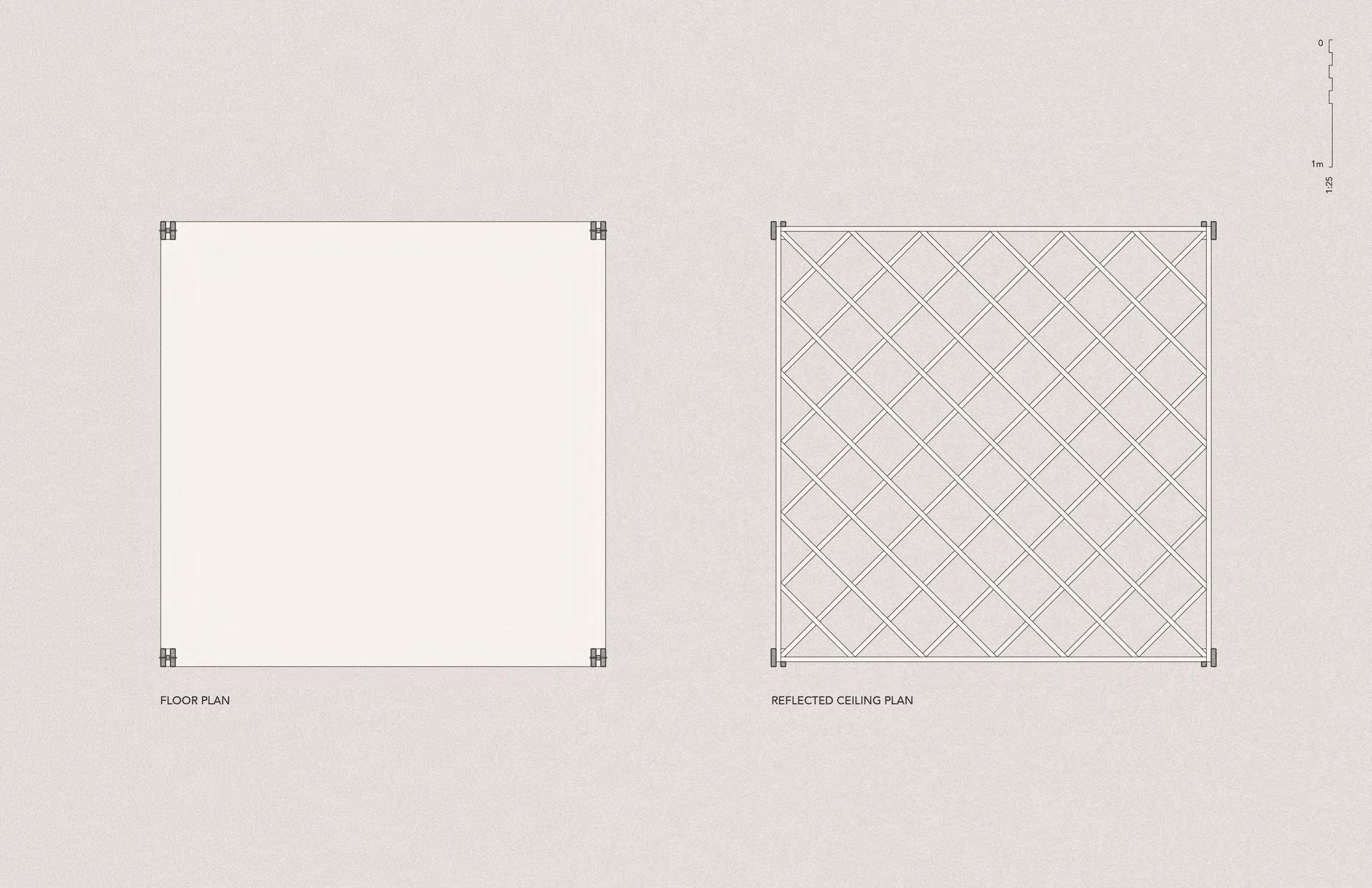

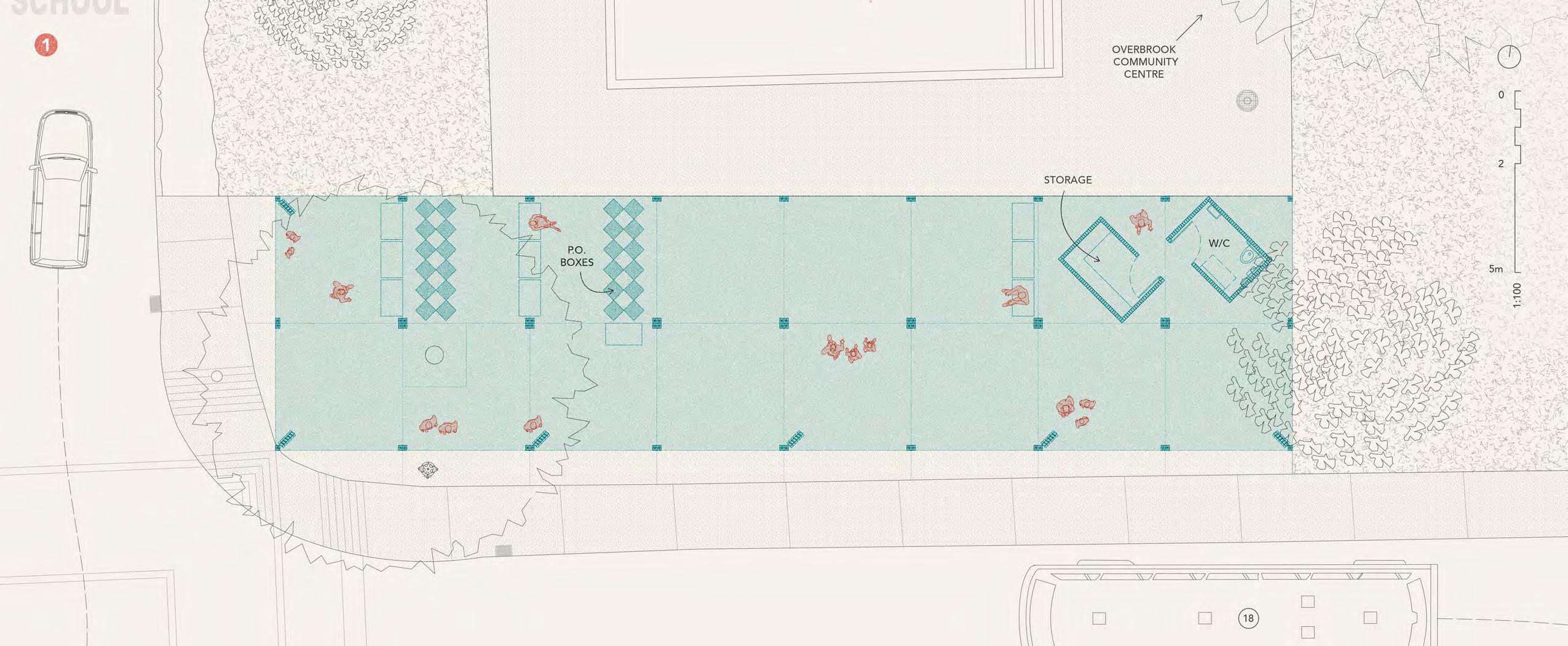

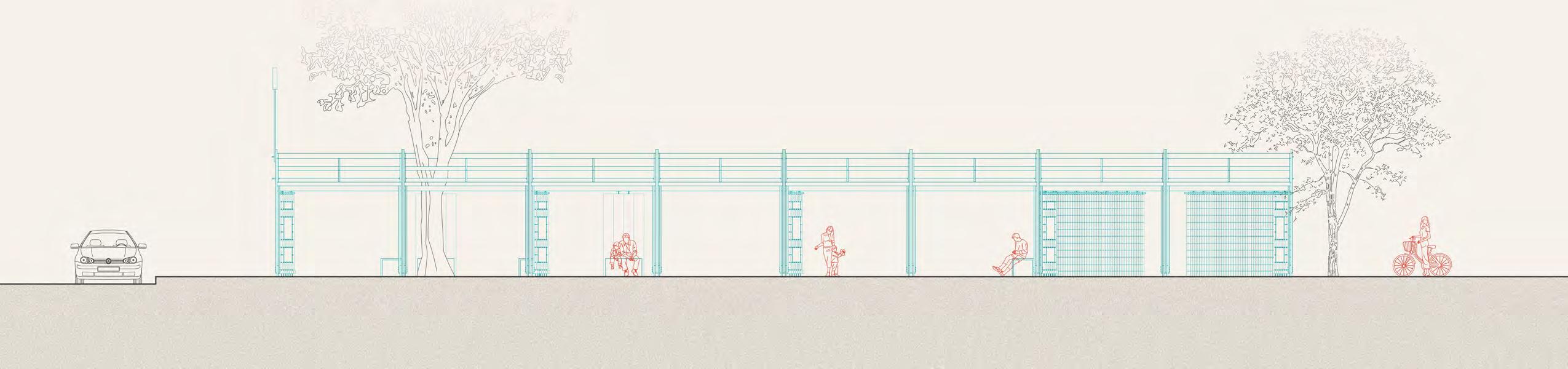

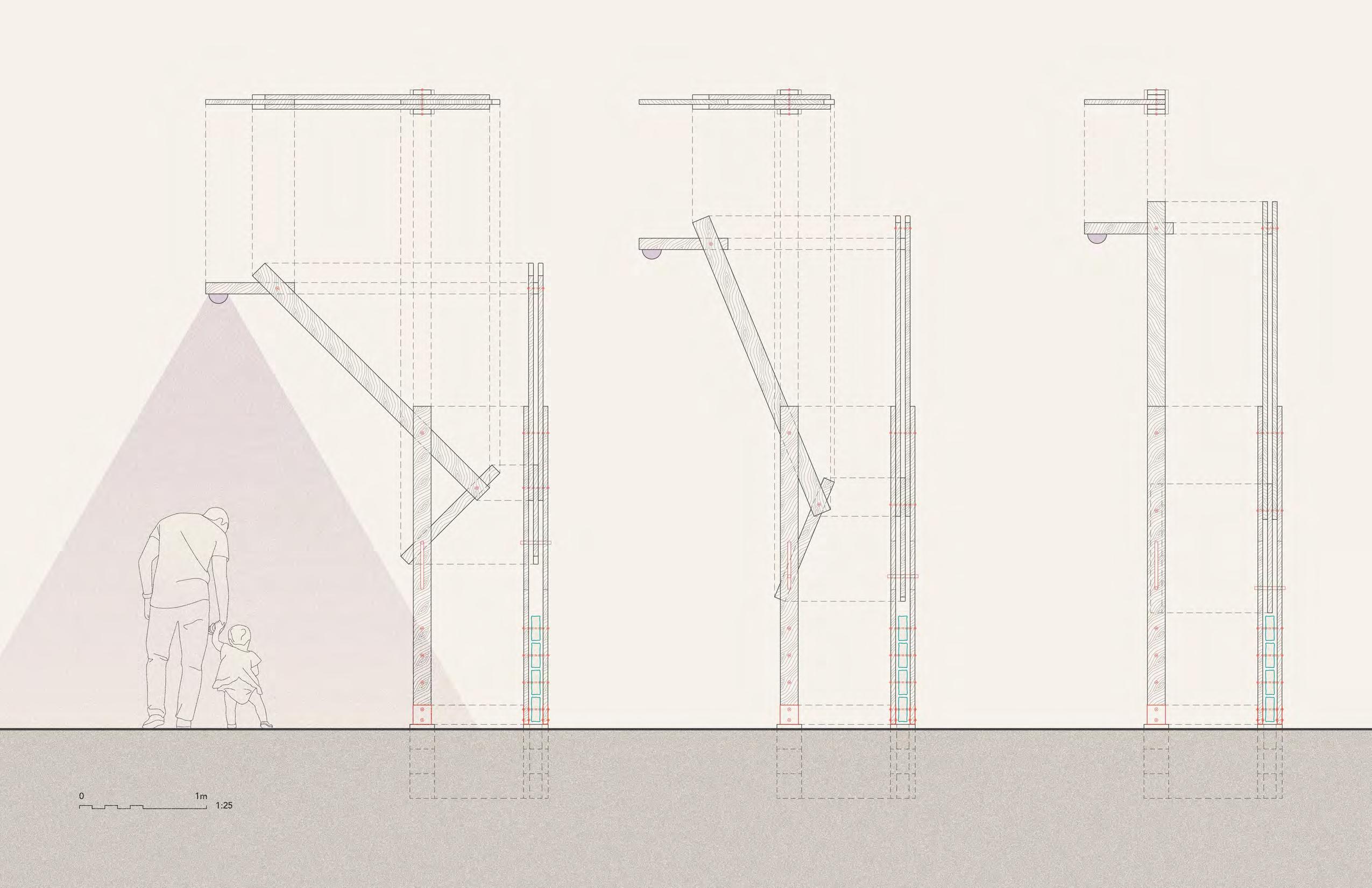

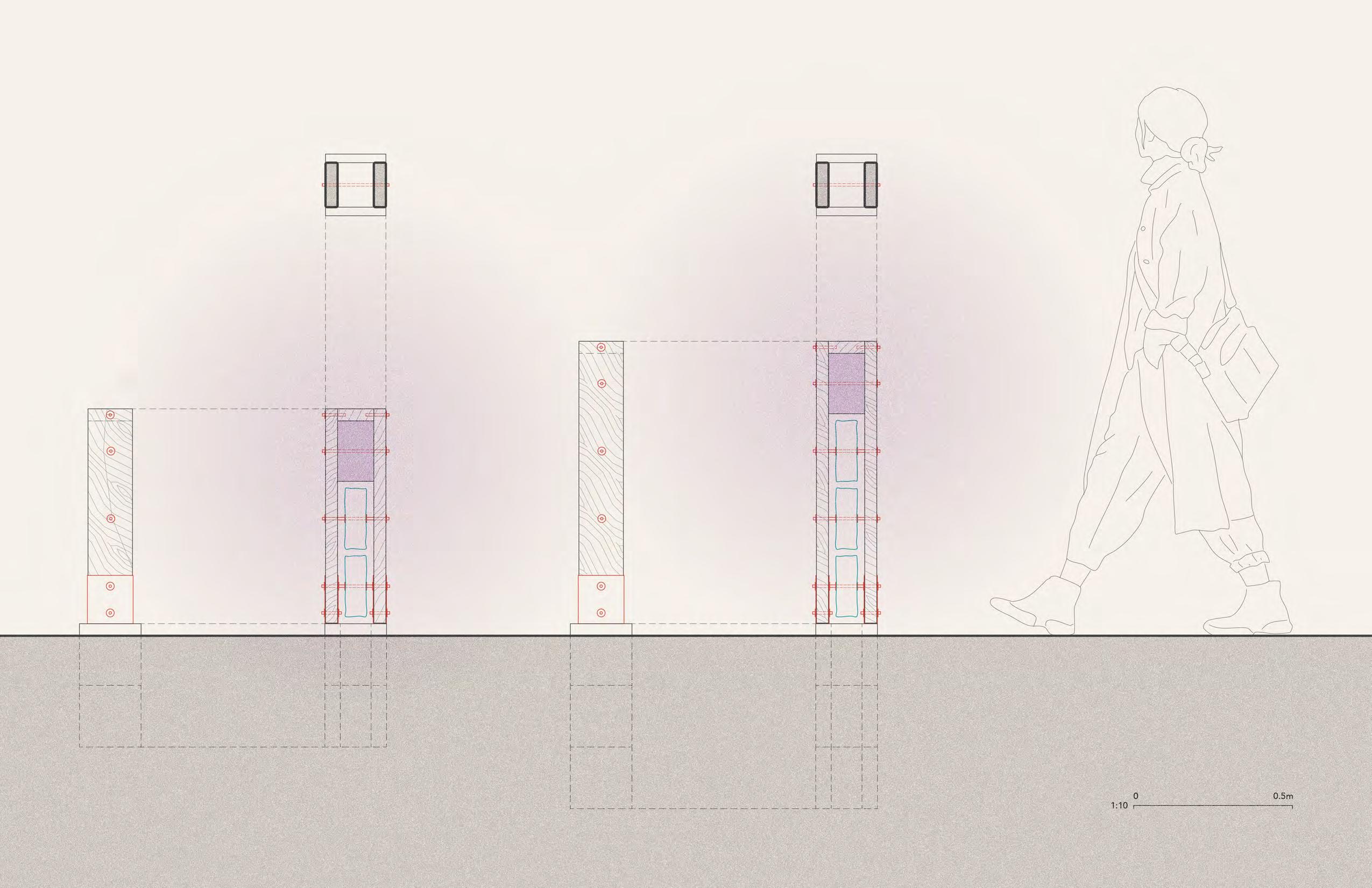

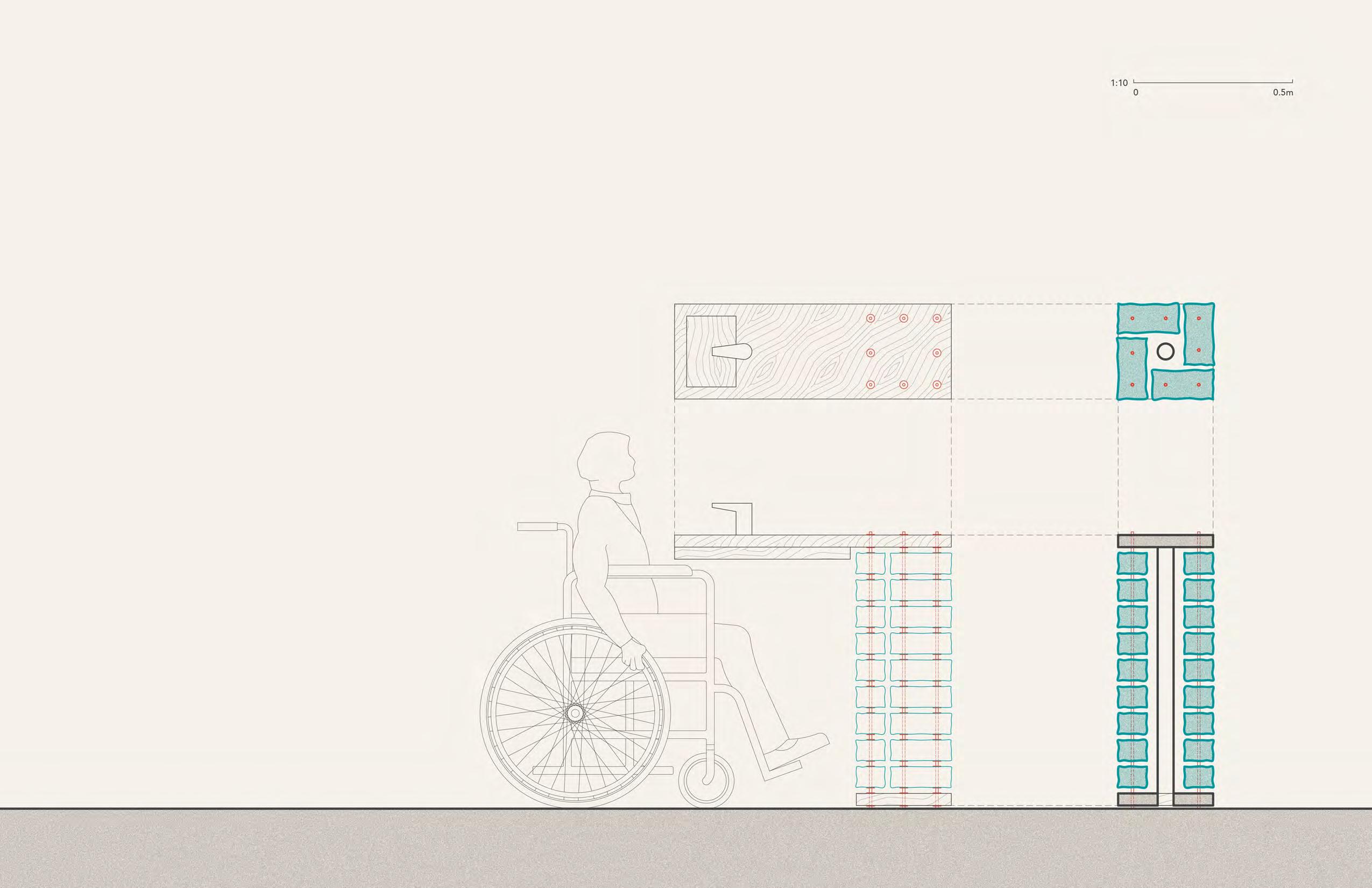

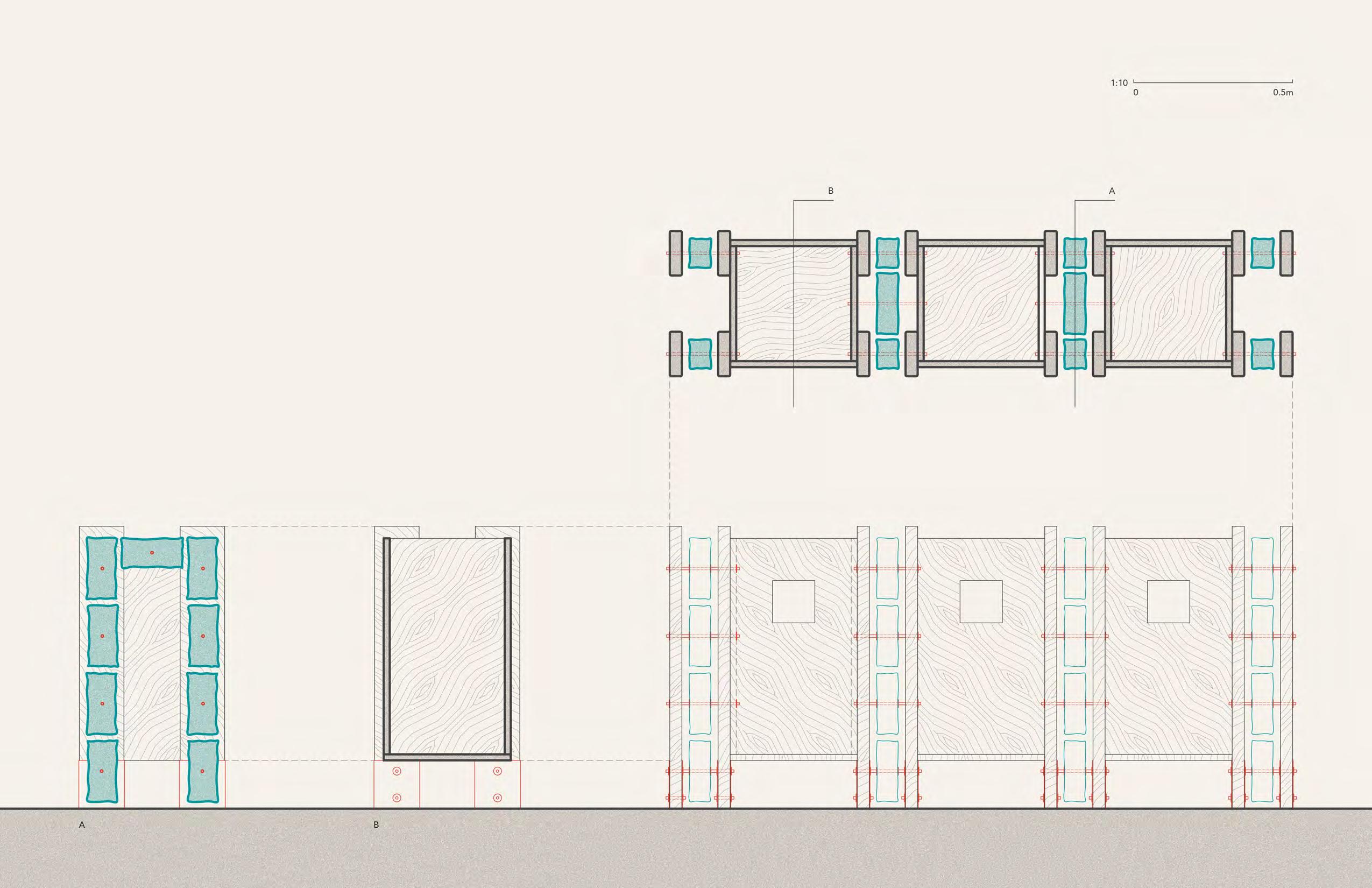

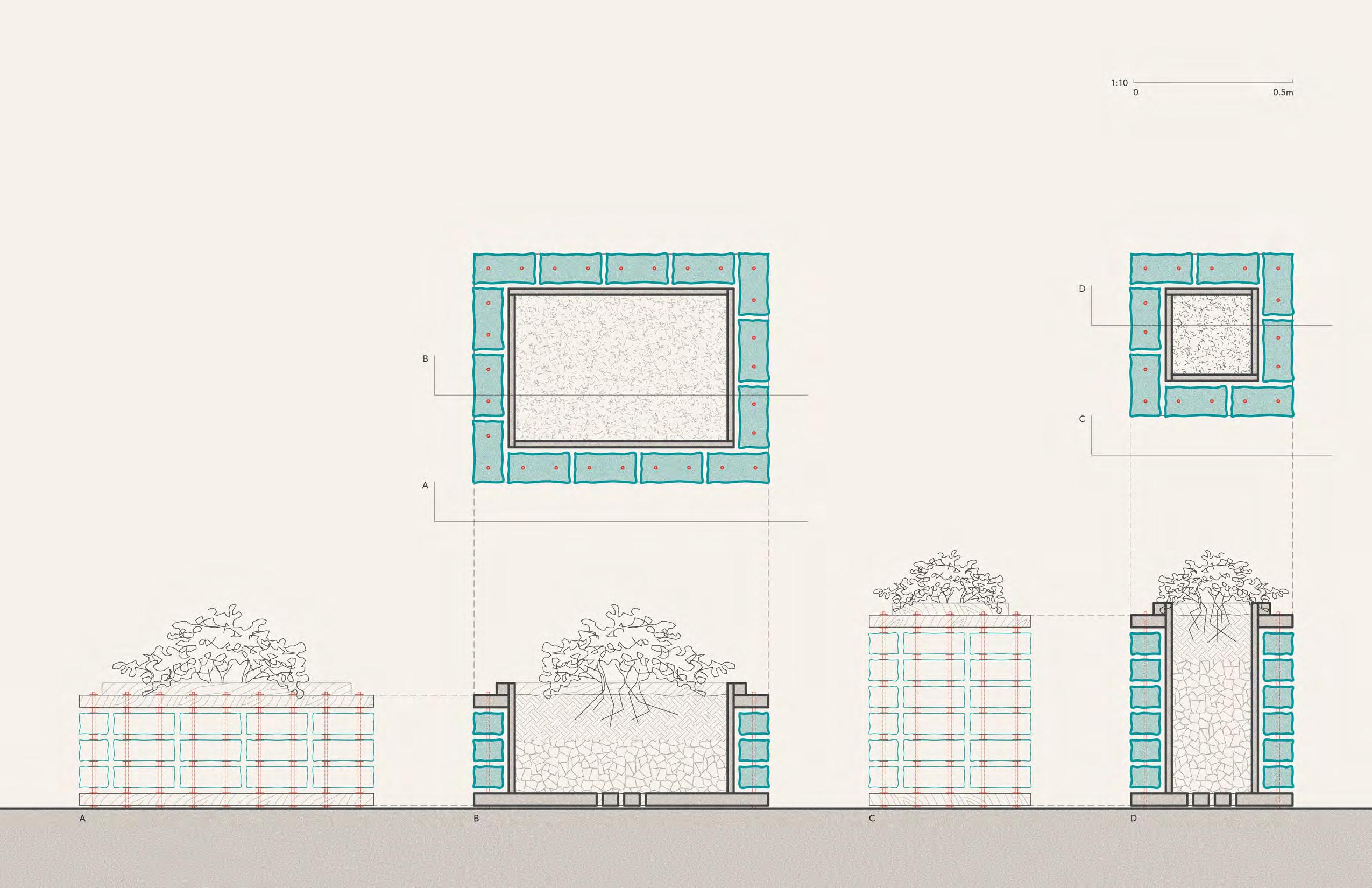

As illustrated in the following pages of this document, the project uses square timber modules as a base, which can be configurated in varying quantities and shapes depending on site, program, and demand. Under this canopy programmatic elements may be added as needed, making every intervention unique. Both the canopy and program components of the project use entirely dry, mechanical joints, which can be undone with ease. The brick, rather than cemented in place with mortar, is skewered and suspended. Matching street furniture for the project has also been conceived in this fashion. Thus, Circular Overbrook can be assembled, disassembled, and reassembled in perpetuity.

Although the many new builds create homes for new residents, the decades of life spent in the homes that one stood on those lots are erased without a trace. The collective memory of the residents and their network within Overbrook are severed at once.

In recuperating the materials that once made up these dwellings, collective memory is enhanced and prolonged. The bus shelters function on both literal and symbolic levels: in addition to providing access to public transit, shelter from the elements, and services such as restrooms and dining space, they act as an exhibit of sorts, showcasing lives spent in the community in its houses. In the shelters, timber framing and brick from former façades hang above and around you, like skin and bones of the living organism that is a home. The wood is aged and splintered, the bricks are chipped and stained—like scars and wrinkles.

Circular Overbrook is an amplification of collective memory, salvaged, and rerouted from the landfill back into the community—a kit of moving parts, given a second life. The project seeks to enrich the mundane experience of public transportation by creating a sense of belonging and pride through these interventions, evoking playfulness, comfort, elegance, and joy in their use.

Queen Mary & Quill

Queen Mary & Lola

Queen Mary & Quill

Queen Mary & Lola

1 Reused 2x6 ceiling canopy

2 Aluminum U-channel

3 Aluminum washer Ø 25 mm

4 Reused 2x6 cap piece

5 Aluminum wire Ø 8 mm

6 Reused brick, 20° dogtooth coursing

7 Information panel

8 Reused brick, stack coursing

[per module]

The project I have developed in the second phase of this term’s studio exists only due to the extensive community research done by me and my teammates and the guidance offered by community members in the first phase. In all my studio projects thus far, site analysis has been much briefer. In the usual order of things, I would be assigned a site and design a building I think would respond to the project brief to the best of my abilities. However, following the documentation in Phase I, it seemed less appropriate to choose a single site and impose an intervention on it.

This term, I chose a different approach. What does architecture look like without one single site? How can it accommodate an ever-changing program? How can it be disassembled and reassembled? How can it be enlarged, reconfigured, or reduced?

Addressing access to transit as a primary goal for the project allowed me to work in the smaller scale of bus shelters. I have enjoyed and feel that I’ve learned a lot from working at this scale and being compelled to consider finer details in my design, such as joints and assembly, in hopes of creating something that approaches a more modest, feasible proposal than in previous studios.

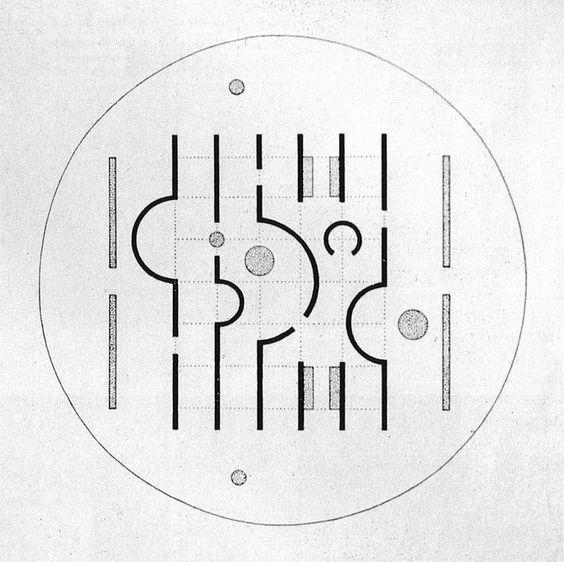

A Sonsbeek Pavilion

Arnhem, Netherlands

Aldo van Eyck, 1966

B Multipurpose Court at St. Mary’s School

Rajkot, India

playball studio, 2022

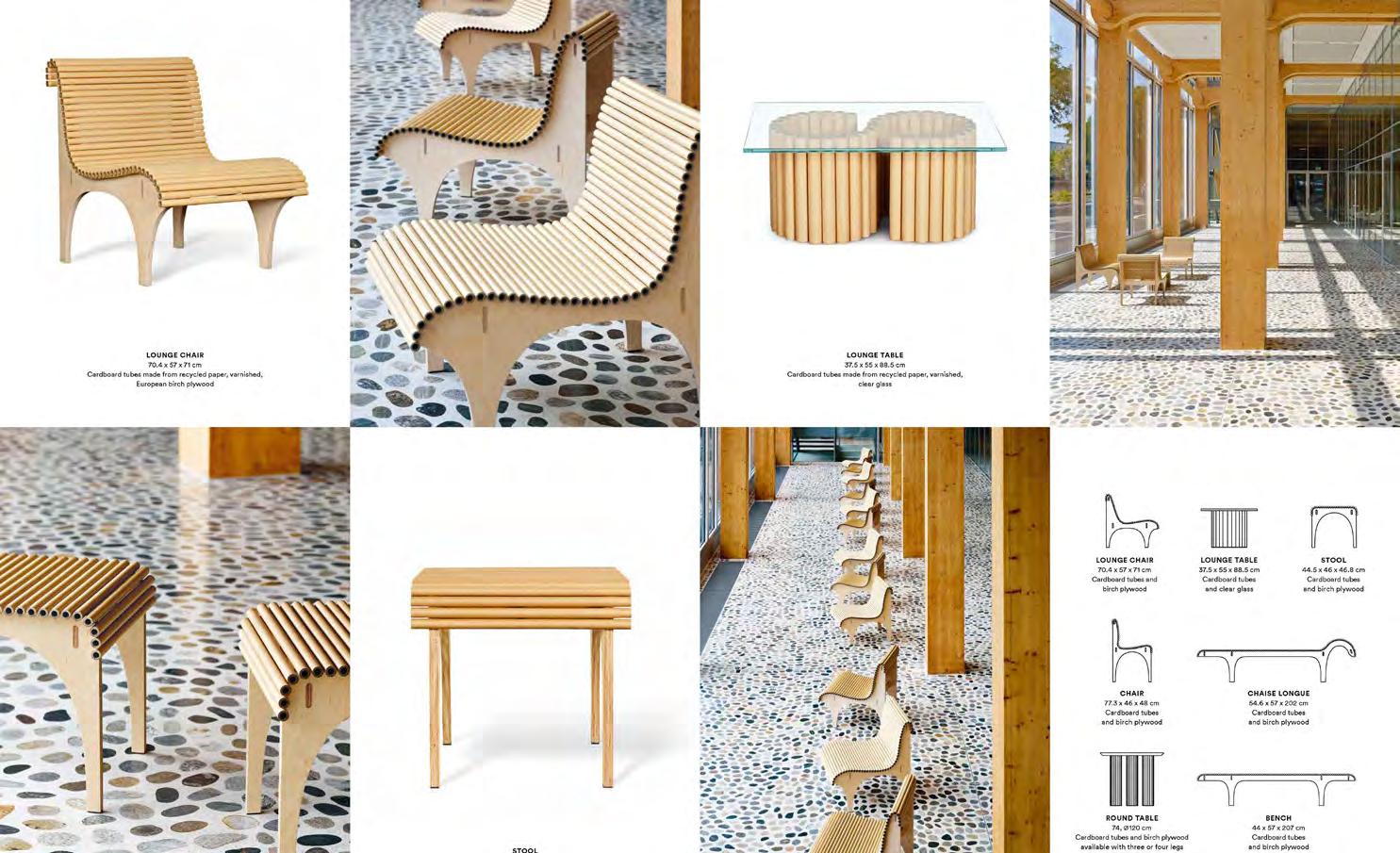

C Carta Collection

Shigeru Ban, 1998

D Plaza El Sol Renovation

Sestao, Spain

Ele Arkitektura / Tarte, 2021