12 minute read

How do you decide a neighborhood’s future?

BY: KYLIE CAMERON

FAIRMOUNT SPRANG UP IN THE LATE 1890S, WITH CLOSE TIES TO ITS COLLEGE NEIGHBOR, NOW KNOWN AS WICHITA STATE UNIVERSITY. OVER A SERIES OF TRANSITIONS, WHICH INCLUDED FAIRMOUNT BECOMING A LARGELY BLACK NEIGHBORHOOD, THEIR RELATIONSHIP CHANGED. NOW DEVELOPERS WHO HOPE TO SERVE A GROWING STUDENT BODY ARE REMAKING FAIRMOUNT’S NORTHERN EDGE WITH HIGH-END STUDENT APARTMENTS. IS THERE A WAY TO RESOLVE STAKEHOLDERS’ COMPETING VISIONS FOR THE FUTURE?

Advertisement

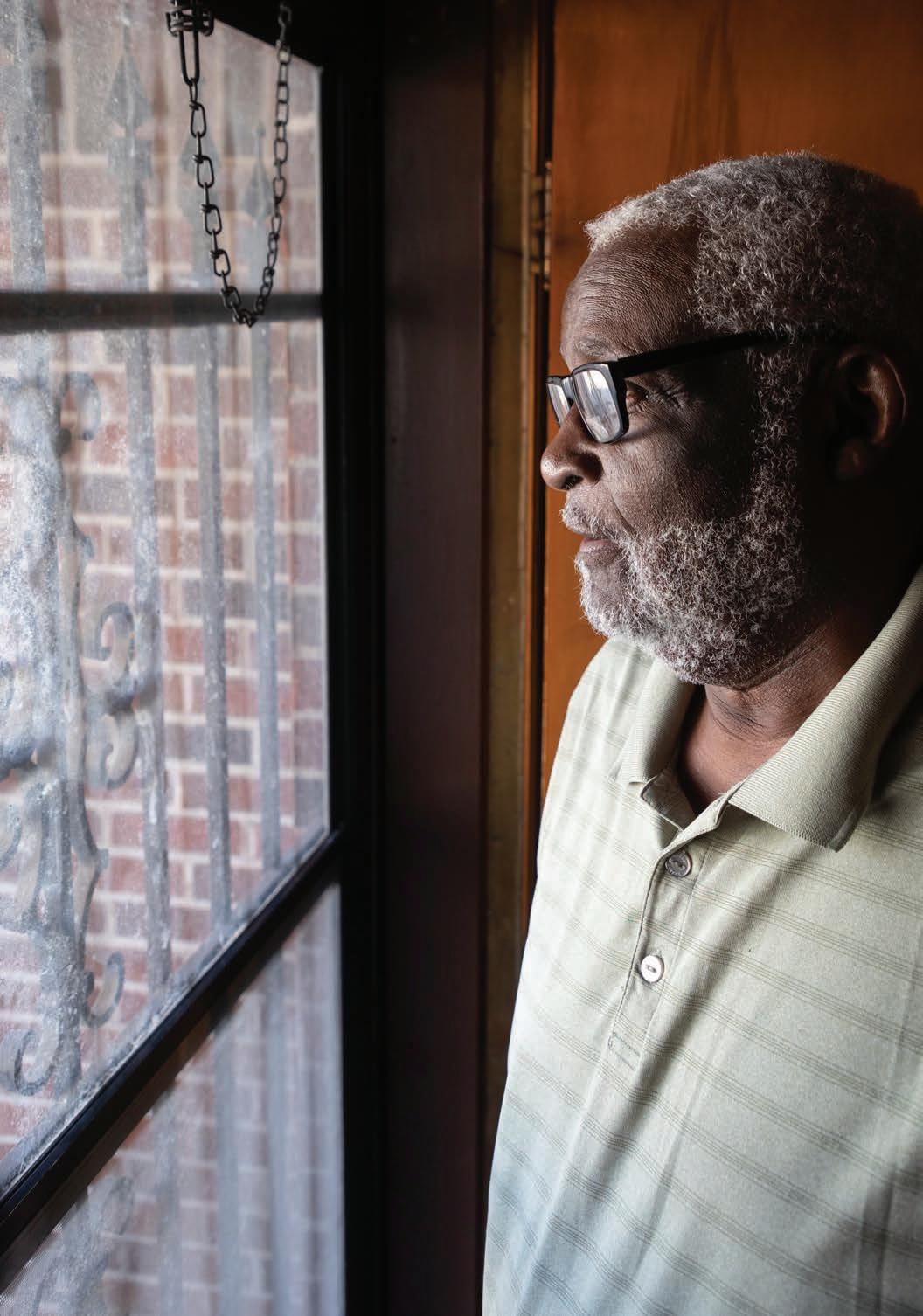

When Jim Maloney, 84, moved to Wichita’s Fairmount neighborhood in 1968, he was one of the first Black residents to live in the residential area, located directly south of Wichita State University’s campus.

There was only one other Black family on the block when he moved to 15th Street and Fairmount Avenue, on the western edge of an area that stretches from Hillside Street to Oliver Avenue between 13th and 17th streets in the city’s northcentral core. They moved soon after.

“It was predominantly white,” he says.

That soon changed. Efforts to desegregate housing and schools, and the phenomenon of white flight, resulted in more Black residents moving into the neighborhood and whites moving out, not only in Fairmount but in older urban neighborhoods across the country.

Today the largest percentage of residents in the neighborhood are Black.

These days, Maloney is watching another transformation unfold, the latest in a series of transitions that have continually remade Fairmount since its establishment in the late 1800s. In its beginnings, the neighborhood was directly tied to Wichita State, then known as Fairmount College. Several homes in Fairmount served as residence halls or housing for professors.

The changing eras can be seen in Farimount’s varied housing styles. Sprawling Victorian mansions pepper every few blocks with dozens of ranch-style homes in between.

Now, to the dismay of some residents – and the delight of others – developers are remaking the northern edge of Fairmount from low-income housing into luxury student apartments. For his part, Maloney says the changes represent an improvement.

“I like the change,” Maloney says. “I mean, it’s for the better, and it looks good.” its history and leaves room for homeowners, developers and the student population.

But the rate of change in the neighborhood is increasing, touching such pillars of the community as the Fairmount Congregational Church, which was once connected to the university.

The church served as a beacon to the community until 2019 when its congregation decided to move due to dwindling attendance numbers and structural issues with the building. It was one of the first churches to regularly broadcast religious messages over the radio. It was also one of the first in the nation to serve as a polling location, according to Wichita State’s special collections.

“People living in Fairmount may or may not always connect to Wichita State,” WSU history professor Jay Price says. “So Fairmount had been intertwined with the college for so many decades; now, those are two different communities.”

MULTIPLE STAKEHOLDERS, DIFFERENT VISIONS

Statistically, Fairmount is a diverse neighborhood, where 43% of residents are Black and 25% are white, according to the latest census figures. But the populations aren’t evenly dispersed. Most white residents live along 17th Street, directly across the street from Wichita State’s campus. The connection between the neighborhood and the college, while clear in the beginning, is now cloudy, in part because of the many stakeholders who own property directly south of the campus.

They have their own visions for what they want to see in the neighborhood, and differing ideas on how to accomplish it.

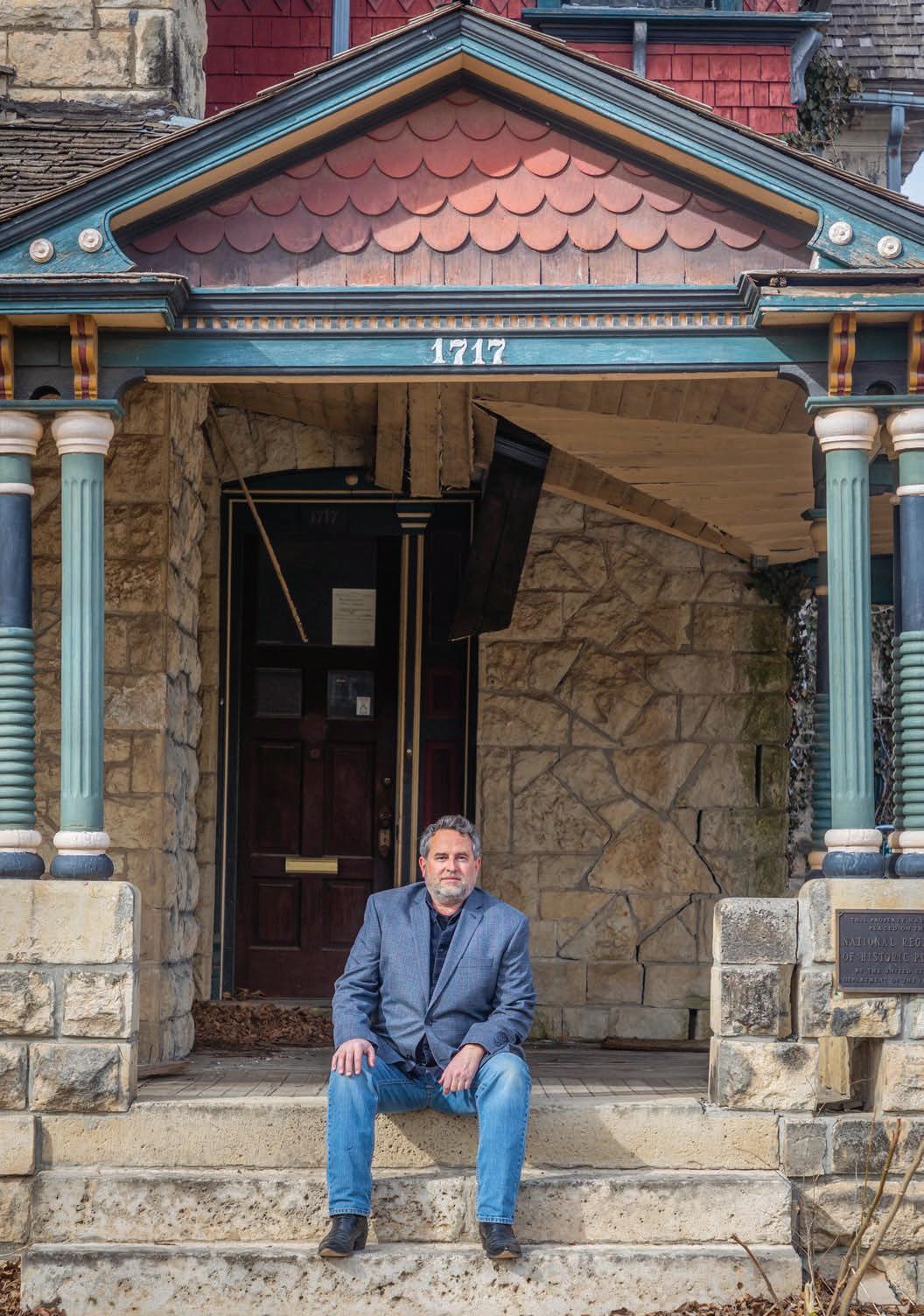

“So we started off fixing properties … one at a time. Duplex here, or four-unit building there, and 12 units and 25,” developer Mark Farha says.

A developer bought the church in 2020 and is turning it into an event venue – almost a metaphor for what is happening to the entire historical neighborhood.

Student housing, mostly high-end student apartments not associated with the university, now lines 17th Street. Before those apartments went up, modest brick quadplexes and other lower-density housing for students served as the north entrance to the neighborhood.

There’s a sense of uncertainty in the neighborhood, with historical boundaries, such as limiting development south of 16th, seemingly less permanent than they were a few years ago. That raises questions about how there can be a shared vision for the future of Fairmount that preserves

“Then here we are some 18 years later. … We’re nearing about 300 doors and plan to build several hundred more over the next few years.”

Farha began buying and developing properties in the neighborhood with his partners in the early 2000s because of the land’s proximity to campus. The group saw an opportunity in developing the area for student housing and renovating already

Jim Maloney, 84, one of the first Black residents to move into Wichita’s Fairmount neighborhood, has lived in the area for more than 50 years. He's seen his share of change over that time and is unperturbed by what's taking place currently. "I like the change," he says. "I mean, it's for the better, and it looks good." Photo by Jeff existing properties.

“Wichita State is attracting more students, and they’re on the map more and more every year,” Farha said.

But other developers are ushering in more sweeping changes. High Plains Development includes Todd Farha, who is Mark’s cousin, and other developers. The group recently demolished a cul-de-sac of quadplexes that were built decades ago.

Those quadplexes served as housing for international students and low-income residents. Multiple residents allege that after High Plains bought the properties, it let them go into disrepair.

Then residents were given 60-day notices to vacate so the group could build student apartments.

“I don’t think it’s a bad thing to … develop more and make nicer places,” Roosevelt Court resident Jacob Tollefson said last year, “but I feel like they probably could have been a bit more open about what they were planning on doing.”

Demolition began soon after residents vacated, and construction is well underway.

Now rents are rising in the area. In 2019, a two-bedroom apartment nearby went for less than $600 a month. Now, that same apartment, with some upgrades, is listed for $750 a month, according to Zillow data.

High Plains didn’t respond to multiple requests for comment.

Resident Push Back

In the normally quiet residential neighborhood, it’s hard to ignore the ongoing construction.

In Fairmount Park, which sits in the middle of the neighborhood and spans several blocks, construction noise echoes from a few streets over.

Decades ago, residents raised alarms about developers beginning to buy property between 17th and 16th streets, and began to worry about displacement, according to City Council member Brandon Johnson, whose district includes Fairmount.

“I get less – probably because people are displaced now – but I get less concern of displacement than I used to,” he says But back then, residents thought it was the university buying property.

“That fear wasn’t unfounded by the neighborhood,” Johnson says, “but that it wasn’t WSU, it was these developers that saw an opportunity adjacent to WSU.”

Jimmy Guinn lives at the corner of 16th and Fountain streets and says he’s lived in the neighborhood going on 40 years.

In a conversation with another Fairmount resident, Darryl Carrington, Guinn expressed his concerns about the university owning and developing property south of 16th Street, but Carrington quickly corrected him.

Still, Guinn is dissatisfied with the development.

“I don’t know who owns it, but whoever it is, they don’t care,” Guinn says.

“I bet they don’t stay here in this neighborhood.”

Property owners who don’t live in the area are also dissatisfied with the development.

On all sides of his residential property on Fairmount Street, Lonnie Barnes is surrounded by developments from Mark Farha, and now the proposed University Village project to the north. The University Village development is envisioned for property owned by WSU along 16th and 17th streets between Hillside and Oliver. The university owns about two dozen parcels south of 17th, but none south of 16th.

Barnes says the development that’s happening in the neighborhood isn’t reflective of the wider community.

“(The) community can’t afford them or even utilize them,” Barnes says. “They can’t afford office space in none of this. … It’s just kind of monopolizing and isolating the community.”

He’d like to see opportunities for residents and minority-owned businesses in upcoming development projects.

“I have more of a vested interest in bringing some things in here that our community could use as well and give us opportunities,” he says.

It’s still too early to tell what businesses University Village will attract.

Barnes also says developers and residential investors coming to the neighborhood and buying homes has contributed to blight.

“Back in the ‘80s and ‘90s in here, these were homeowners and well-kept, well-maintained houses,” Barnes says. “You drive through here now, you’ll see that a lot of these here are deteriorating.” As for the rental homes in the area owned by Mark Farha, he says most of the properties he owns have been rentals for years, meaning developers aren’t driving a transition away from homeownship.

“This neighborhood is 95% rental inventory to begin with,” Farha says. “So most of the houses and the land and buildings that we’ve bought, we’ve bought from other landlords.”

Many residents of the neighborhood have also made it clear they want 16th Street to serve as a dividing line between the neighborhood and new development.

In a recent zoning case, Mark Farha wanted to build multifamily townhouses at 16th Street and Vassar Avenue. After residents expressed their dissatisfaction with the plans, Mark Farha agreed to not seek rezoning of the area south of 16th Street.

“I still am hopeful that one day, we can design something that the neighborhood would feel is an improvement over the properties that you see here currently,” he says.

Seeing Good And Bad In Development

Maloney, who’s been in the neighborhood since 1968, lives two streets down from Barnes’ property, farther away from the construction. But he sees development in the area as beneficial.

“It was a college atmosphere in the first place,” he says. “Now everything is just college students, that’s the biggest change.”

With the development in the area, investors have taken notice and regularly send letters to residents offering to buy their homes.

Maloney just throws the letters in the trash, though. With new student housing, students also need a space nearby to hang out, shop and eat – which is what the University Village project aims to provide.

The proposed site for the mixed retail and office building sits across Holyoke Avenue from Kirby’s Beer Store – a “hole-in-the-wall” bar and music venue that’s been in the area for decades.

The university owns the land and has contracted with Lane4, a commercial real estate firm based in Kansas City, Missouri, to develop it. The project also brings another group with a vision for the area.

“It’s kind of a big ask, though, to ask for anyone to come in and put up their own money and take on all the risk of developing something without any type of guarantee by the university,” WSU general counsel Stacia Boden says.

“We’re not guaranteeing or even promising that we’re going to lease anything from them.”

Businesses along 17th Street see the change and influx of new residents in the area as beneficial. Fairmount Coffee sits next to High Plains’ new development, where Roosevelt Court once was. While a coffee shop for students, staff and those who find themselves in the area, it also serves as a Lutheran ministry.

“It’s kind of crazy now to see what has happened around us with the development,” says Paige Edgington, Fairmount’s director of outreach. “I think it’s very exciting from the aspect of what it means for the opportunity to reach out and engage more people.

“It is a lot of change – and change can be scary, too.”

People looking for business opportunities have also taken notice of the new development and the subsequent increase in traffic in the area.

Hussain Alghanem is hoping to open a new convenience store in the same building as Kirby’s Beer Store by early spring.

Alghanem says his store will offer some food and drinks, cigarettes and possibly expand to coffee, juice and slushies.

“It will be good business,” he says, “and then I see a lot of traffic, a lot of cars here.”

Blending Cultures

Darryl Carrington has walked the Fairmount neighborhood on a regular basis since 2005, when he moved from Compton, California.

On a crisp winter afternoon, Carrington points to homes on every block and has a story to tell about the homes and the people who used to live there.

Anyone who happens to be standing in their yard or driveway as he walks by is greeted and soon finds themselves engaged in conversation.

Crisscrossing the neighborhood through Fairmount Park, Carrington also picks up trash.

Through his advocacy and his work, it’s clear Carrington cares about the neighborhood –especially when it comes to getting Fairmount residents and the university to come together.

“The neighborhood and the communities are blending,” Carrington says. “The culture is blending.”

Carrington was once employed by the university to build community relations between the neighborhood and WSU.

His position was funded by a grant from the Kansas Health Foundation to create community engagement with Fairmount after the 2014 rape and murder of Letitia Davis in Fairmount Park.

(Full disclosure: The Kansas Health Foundation is the largest funder of the Kansas Leadership Center, which publishes The Journal.)

The grant for what the university called the Enough is Enough campaign ended in 2018. Carrington still continues that work on his own time, taking meetings with university administrators to bridge gaps between the neighborhood and the campus.

“17th Street is actually our longest border with a neighbor … and is our most impactful border,“ Carrington says.

With dwindling homeownership, though, it’s hard to get residents engaged like Carrington is, making it even more challenging for long-term residents to have a voice in Fairmount’s future.

“I think as people distrust government or feel like we’re going to do what we’re going to do anyway, you have less property owners or less homeowners there who really, truly are invested in the neighborhood,” Johnson says.

“And you have some renters that just say, ‘Well, if it gets too bad, I can move.’ ”

It’s a trend seen elsewhere in Wichita, as well. Membership in neighborhood associations has declined, which can lead to less engagement with local governments.

Many people who were once active in neighborhood associations have gotten older, which is apparent in the Fairmount neighborhood, with most homeowners well into retirement age.

“I don’t know what we’ll do when we leave the home,” saysMaloney, whose wife has dementia. “I’m leaving it up to our kids. … They got their own home. … I’ll let them handle that.”

Guinn, who lives on the opposite side of Fairmount from Maloney, has also left the ownership of his home up to his daughter.

“I hope and pray that she doesn’t sell.”

The aging population of the neighborhood is also clear in narratives told by Carrington. Some houses he points at, he’ll note that the owner has passed away, moved into an assisted living facility or simply moved away.

“Those days are gone,” Carrington says, reminiscing about relationships those homeowners had with each other. “But the work still continues.”

Discussion Guide

1. Who are the factions in this story? What do they value? What do they stand to gain or lose?

2. What would working across factions look like in this situation? And whose work is it to do?

The Fairmount neighborhood has had a long and significant history, but it's also a complicated one. As the once graceful old faculty homes were clearly losing their luster, a horrifying crime brought attention to the area. Now with real estate investment and gentrification on the rise, the community may be poised to pivot — a prospect that is seen by residents and observers as both unsettling and beneficial. Photos by Jeff Tuttle

SIGN UP FOR UPDATES

Sixty years is a long time. And not enough.

By: MARK MCCORMICK

The most common occurrence in our lives continues to fascinate – the passage of time. Each second, each hour, each day, time sprints, then walks, then sits.

This year will mark the 60-year milestone for a slew of iconic moments from 1963. I once had a boss who hated anniversary stories, but I love them. They offer us moments to catch our breath and to reflect on how much has changed, and how much hasn’t.

In April 1963, the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. sat in a Birmingham, Alabama, jail cell writing a letter responding to criticism from moderate clergy about his nonviolent direct-action campaign being untimely and his efforts, the work of “outsiders.”

King explained that he was there because injustice was there and that “injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.”

Continuing, King wrote: “We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly.”

Conversely, later that year, during a speech at the University of California, Berkeley, Malcolm X argued for racial separatism.

“Today, our people can see that integrated housing has not solved our problems,” he said. “At best, it was only a temporary solution, one in which only the wealthy, hand-picked Negroes found temporary benefit. After the 1954 Supreme Court desegregation decision, the same thing happened when our people tried to integrate the schools. All the white students disappeared into the suburbs.”

Only the nation’s political tumult could top its racial conflicts.

The Nov. 22 assassination of President John F. Kennedy shocked the nation, and the country received a second shock when Jack Ruby shot and killed Lee Harvey Oswald, the accused assassin, on live television, closing an important avenue of determining the scope of what had happened.