17 minute read

Volume Volume Volume Volume

AS A GROWING LATINO POPULATION PUTS ITS STAMP ON THE ECONOMY AND CULTURAL LIFE OF WYANDOTTE COUNTY, QUESTIONS REMAIN ABOUT HOW TO FOSTER MORE CIVIC ENGAGEMENT AMONG COMMUNITY MEMBERS. DESPITE FUELING THE COUNTY’S POPULATION GROWTH, HISPANIC AND LATINO RESIDENTS OCCUPY JUST FIVE OF THE 46 SEATS ON THE COUNTY’S LARGEST GOVERNING BODIES, AND ATTITUDES ABOUT VOTING CAN VARY WIDELY. A SET OF SMALL EXPERIMENTS OFFERS HOPE FOR ENSURING LATINOS ARE BETTER REPRESENTED BOTH LOCALLY AND STATEWIDE, BUT A WILLINGNESS TO REACH OUT TO FRIENDS, FAMILY AND NEIGHBORS MIGHT BE KEY TO INCREASING CIVIC PARTICIPATION OVER THE LONG HAUL.

As Melissa Oropeza campaigned door to door last fall for a seat in the Kansas House of Representatives, she wanted to make sure she reached out to fellow Latino voters in Wyandotte County.

Advertisement

But like most candidates with modest campaigns, Oropeza, along with her daughter, knocked only on the doors of registered voters who had participated in recent elections. To do otherwise would be a waste of valuable time.

The result, against her best intentions: The vast majority of prospective constituents that her campaign contacted in the 37th District were white, even though nearly 4 in 10 residents of the district are Hispanic, according to Ballotpedia.

“I was surprised it was a small number, smaller than I would have liked to have seen,” Oropeza says of the Latino voters she spoke with. “It’s unfortunate that they’re not represented at the polls, or that I couldn’t knock on those doors because I had such a small campaign. But that is a goal of mine – to reach out to those who are unregistered or undecided.”

It turned out that Oropeza, a Democrat whose great-grandparents emigrated from Mexico, did not need a groundswell of Latino support. She easily won her race in the Democratic stronghold with nearly 60% of the vote, becoming the first Latina to represent Wyandotte County in Topeka. Nevertheless, Oropeza and other leaders are eager for more of Wyandotte County’s Latino residents to become engaged voters. Without their participation, they fear, the county’s surging Latino and Hispanic population risks being underrepresented in important policy matters such as taxation, law enforcement, immigration, health and housing.

“Your vote is your voice,” Oropeza says. “And if you don’t have your voice, then nobody will ever hear you.”

Voter outreach activists can provide ample anecdotal evidence that underscores experiences like Oropeza’s. But to determine exactly how many Hispanic and Latino residents are expressing that voice at the ballot box is difficult to measure –whether in the U.S., Kansas or Wyandotte County.

Voter registration applications do not ask for a person’s race or ethnicity, so analysts rely on surveys and census data to make broad but imprecise observations about the voting habits of Hispanics and Latinos. Still, these analysts can detect trends and patterns. A Pew Research Center analysis of the 2018 midterm elections, for example, shows that 40% of eligible Hispanic or Latino voters in the United States cast a ballot that year – up from 27% in 2014. Despite that growth, Hispanic and Latino voting activity still lags behind the general population. According to the same Pew analysis, voting rates among eligible white and Black voters were more than 10 percentage points higher.

Several voter outreach activists told The Journal that Latino and Hispanic voting behaviors in Wyandotte County and Kansas likely mirror national trends. And all agreed that there remains a large pool of eligible Hispanic and Latino voters to tap. “We can tell when we go canvassing. We can tell when we poll,” says Aude Negrete, former executive director of the Kansas Hispanic and Latino American Affairs Commission. “When you go door to door, those precincts that have a high concentration of Latinos in Wyandotte County, we find that a lot of them are not registered and that there is a lack of engagement.”

While Latino Americans like Negrete and Oropeza are quick to say that one’s ethnicity cannot predict voting preferences, and that Latinos and Hispanics do not comprise a monolithic voting bloc, both believe that it is important to attract more Latino and Hispanic voters in order to elect candidates who understand their experiences and can address their unique needs. The very health of their communities, they say, depends on it.

“It’s not about just one person or one group. It’s about ensuring that everyone in a community has more prosperity or a better quality of life,” Negrete says. “It’s about having barriers addressed and targeted. It’s about engagement and communication that allows for a more prosperous community.”

Flexing Economic Muscle

No story about Wyandotte County is complete without noting the radical political changes at the turn of this century that ushered in a new era of economic growth. Decades of population loss had cratered its tax base. Kansas City, Kansas, struggled to keep up with basic maintenance and services. Blight and crime increased. Then in 1997, voters approved the consolidation of the

Kansas City and Wyandotte County governments, a move credited with creating a healthier political environment that has attracted new development, such as Kansas Speedway, along with new residents. Indeed, over the last two decades the county has seen a modest 6.7% population growth.

But that story fails to tell how the county’s Hispanic and Latino residents have contributed to its growth. In fact, without their presence, it’s likely that in recent years Wyandotte County would have lost more residents and the taxes they generate. Since 2000, its number of Hispanic and Latino residents has doubled; at nearly 56,000, they represent roughly a third of the county’s total population. Meanwhile, in the last decade its white and Black populations have been noticeably dropping.

Despite their increased numbers, Hispanic and Latino residents occupy just five of the 46 seats on the county’s largest governing bodies: the Unified Government’s Board of Commissioners, the Kansas City, Kansas Board of Public Utilities, the Kansas City, Kansas School Board, the Kansas City Kansas Community College Board of Trustees, and the county’s 16 elected district court judges. That under-representation is echoed across Kansas: Although Latino and Hispanic residents make up 12.7% of the state’s population, they hold just six seats in the 125-member House of Representatives (two from Wyandotte) and none in the 40-seat Senate.

Political under-representation aside, Wyandotte County’s Latino communities are flexing their economic muscle. Consider the Central Avenue corridor in northeast KCK. Two decades ago the 13-block stretch of storefronts, apartments and churches was notorious for urban blight: a smattering of empty buildings, high crime and a gathering spot for prostitutes and drug dealers. In the 1990s and early 2000s, a number of buildings were razed, leaving large swaths of weedy vacant lots.

The area still wrestles with crime, but it is not rampant as it once was. Today, those empty storefronts are largely filled, most of them sporting signs in Spanish. Some of the vacant lots have finally been developed. Restaurants, bodegas, Mexican bakeries, tortillerias, law offices, party supply venues and wedding shops line the street. Surrounding residential neighborhoods are bouncing back; property values are increasing.

“Central Avenue was a mess,” says Irene Caudillo, the outgoing president and CEO of El Centro Inc., a nonprofit organization that offers several services designed to improve the lives of Latino residents. “It was actually scary to drive through. Now I’m having lunch there at least once a week.”

A similar renaissance is occurring throughout the city’s urban core, especially along the commercial corridors of Kansas Avenue, 7th Street Trafficway, 18th Street, and Minnesota and State avenues. The county’s south of the border cuisine has even garnered national attention, thanks largely to a Taco Trail campaign launched by the Kansas City Kansas Convention and Visitors Bureau. The impact of this growth is significant. The Central Avenue Betterment Association, a nonprofit organization that promotes economic development and community engagement in the area, estimates that businesses within these urban corridors – 60% of them Latino-owned – employ 3,000 to 4,000 people. Grocers and restaurants alone are responsible for $8 million to $10 million in sales every month.

“There is not a single person who has generated any of that,” says Edgar Galicia, the Central Avenue Betterment Association’s executive director. “It’s the whole community, the residents of the area, and their will and ambition to improve their quality of life on their own.”

Perhaps the best expression of this economic growth is the city’s annual Dia De Muertos event – a daylong celebration on Central Avenue that’s held the first Saturday of November. Taking its cue from the joyous tradition of honoring the dead, the event features food tents, music stages, vendors and nonprofit booths. In between are dozens of “ofrendas,” altars that serve as offerings to the dead, often with the loved one’s photo surrounded by objects they cherished. The sidewalks come alive with women and girls in elegant dresses and bonnets of brightly colored flowers. They’ve painted their faces to look like that of a skeleton, signaling that they have taken on the guise of La Catrina, the doyenne of Dia De

Muertos who comforts the living with the fact that death is the great equalizer, not something to fear.

The celebration reaches its climax with an afterdark parade that features Catrinas, floats and banda musicians making their way along Central Avenue. Some 20,000 people from across the Kansas City region cheer them on, nearly triple the number who attended the event when the association launched it in 2016.

“The more positive activity generated, the less negative activity we get,” Galicia says. “That’s the philosophy behind all the festivals and all the business investment along Central Avenue. We generated quite a bit of strategies to promote that good. So people take notice and continue pushing and continue investing.”

Jose Rodriguez, board chair of the betterment association, believes that events like Dia De Muertos open conversations about the increasing influence that Wyandotte County’s Latino businesses and residents have on the broader community – and that the area’s politicians are paying attention.

“It’s an opportunity to engage with the mainstream,” Rodriguez said that day as he was about to announce the winner of the Dia De Muertos Catrina contest. “Our hope is to spark some type of interest, from citizens to elected officials.”

Rodriguez has lived in the United States for more than 30 years, after arriving with his parents when he was 6 years old. He couldn’t have known it at the time, but that marked the beginning of a decades-long journey to become a U.S. citizen. When he finally swore allegiance to the country he’s called home for nearly his entire life, he had the peace of mind that comes with knowing that no one could ever, for any reason, deport him. But more importantly, he felt a responsibility to vote, which he did for the first time in last August’s Kansas primary.

“To actually cast a vote and walk out, that was a big moment of pride,” says Rodriguez. “I thought of all those questions on the citizenship test. You know, all your rights and responsibilities. That was on my mind. I had to do it.”

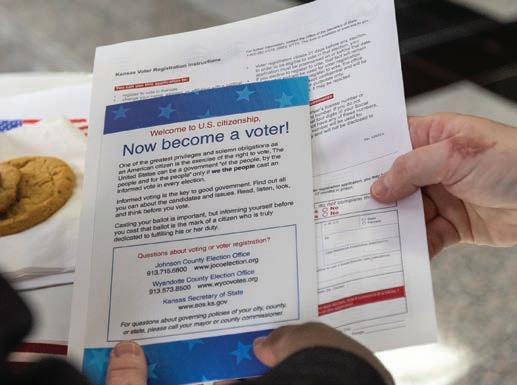

So, too, for Fernanda Reyes Goldman. Last November, Goldman went to the Robert J. Dole Federal Courthouse in Kansas City, with more than 100 immigrants from 44 countries to participate in the same naturalization ceremony that Rodriguez had just months earlier. In unison, they stood in the courtroom of U.S District Judge Holly L. Teeter, raised their right hands, and swore to protect the U.S. Constitution against all enemies foreign and domestic.

The oath they took did not require them to vote, of course, but that newly acquired right was on Goldman’s mind. A Mexican immigrant who moved to the United States to marry her husband more than seven years ago, Goldman, like nearly everyone else in the courtroom, had endured years of paperwork, bureaucracy and waiting. But she had one more task ahead of her: register to vote. “It’s very important to have a voice,” she says. “Definitely, everyone needs to vote.”

And the data indicates that Goldman, like other naturalized citizens, will be more likely to vote than her U.S.-born counterparts with Central and South American ancestry. With an estimated foreign-born population of more than 16%, the majority from Latin America, the path to greater civic engagement for many Latinos in Wyandotte County truly does begin with becoming a citizen. A national study of the 2018 midterm election by the Pew

Research Center, for example, found that more than 44% of Hispanic naturalized citizens cast a ballot compared with 39% of their U.S.-born counterparts. But the barriers to becoming a citizen deter many foreign-born residents from even trying, whether they have a work permit, green card or are undocumented. The citizenship test, the cost, the possible need for legal representation, the long wait, the language test – these and other hurdles make it easier for some to just lie low.

Karla Juarez is intimately familiar with this barrier – both professionally and personally. As executive director of the nonprofit Advocates for Immigrant Rights and Reconciliation, she has participated in voter outreach efforts. As the daughter of immigrants, and an immigrant herself, Juarez embarked on a 10-year journey to become a citizen. First came the application for a work permit. Four years later she applied for a green card. Five years after that, she paid the $725 required for the citizenship application and secured a lawyer through a nonprofit organization because she didn’t want to leave anything to chance. Three times a week for a month, she studied for the civics and language test applicants must pass – 10 questions randomly selected from 100 she’d studied.

And it was worth it. When she learned she’d aced the test and that she would soon be sworn in as a U.S. citizen, she teared up. “My whole journey flashed before my eyes, how hard it had been, how long I had waited,” she recalls. “That was all I ever wanted, along with a college degree. This is my country. I grew up here. This is all I know. I couldn’t think of living in Mexico, even though I’m very happy to be a Mexican.” And when she finally cast a ballot in the August 2020 primary, it was a cause for celebration. “I posted it on my social media! First time voting!”

‘THE LOUDER YOU SCREAM’

Juarez and other activists in the Latino community are under no illusions about what it takes to spur more civic engagement. No one can suggest to a working mother to simply add “become a citizen” to her list of tasks for the day. And some immigrants are willing to live with work permits or green cards and the restrictions those documents carry, along with the risk of deportation if they commit a crime. Juarez says she’s tried, for example, to encourage her mother and stepfather to apply, but they’re reluctant. They’re nervous about the history, civics and language test, even though Juarez doesn’t think they need to be. “I keep telling them that they should become citizens,” she says. “The voting piece. That’s huge.”

But as Latino and Hispanic activists in Wyandotte County know, not everyone appreciates “the voting piece” – at least not enough to cut through the many other barriers to voting they face. Some live in mixed households – documented and undocumented residents under the same roof –and don’t have voting role models. Others speak little English and don’t have a good grasp of the political environment because there remains a dearth of Spanish-language campaign literature (not to mention Spanish-speaking candidates). Some are politically apathetic. And some don’t want to draw attention to themselves, even if they are here legally.

“I’ve got people I’ve known for years who don’t give a damn about politics or what’s going on,” says Kansas Rep. Louis Ruiz, among the longest serving Latino members of the Kansas House. Ruiz was first elected to Wyandotte County’s 31st District in 2004 and is also the nominal head of the small, but slowly growing Latino Legislative Caucus, all House Democrats. (Oropeza’s election increased its size to six.)

“When I talk to these people about voting, they say, ‘That’s for others,’” Ruiz adds. “And it hits me more when I hear that from Latinos. For them to tell me they don’t want to be involved or don’t care, that bothers me more than when the average white guy says it. Because that’s my culture, and we have so much at stake.”

This apathy applies to not only immigration issues, but issues related to education, health care and taxes. All citizens need to raise their voices, Ruiz says, because “the louder you scream, the more you’re apt to get services or be listened to.” Despite his frustrations, he understands why many are reluctant to do that, especially recent immigrants. Ruiz recounted the story of his grandfather, who came to the United States in the first half of the 20th century. “He used to say, ‘Be reverent and respectful. No matter how they treat you, don’t draw attention to yourself.’ I said, ‘Yeah, right, that’s going to work.’ But that’s how he grew up. He knew his barriers and what he needed to do to survive.”

Indeed, fear can prevent many Latino citizens from making such a public gesture as voting. They may be here legally, but their relatives or even members of their own household may not. Irene Caudillo, of El Centro, is among those who say a climate of racism and xenophobia – along with politicians who exploit those prejudices – can be enough to keep someone from going to the polls. “When you get these kinds of swings where the rhetoric becomes very intense, we feel like we have to pull back, and it almost feels like we’re starting over,” Caudillo says. Young people of voting age, she adds, “may be reluctant to sign up and do anything that might jeopardize someone in their family. That includes registering to vote.”

The Power Of Relationships

Just as he spares no words when talking about apathetic voters, Ruiz is blunt about his party’s efforts to engage more Latinos. “The Republicans hit the Latino population harder than the Dems do,” he says. “Democrats take Blacks and Latinos for granted. I’ve seen that on the national level. They were very minimal in terms of what they’re nurturing.” This could change in Kansas, he says, with Juan Luengo recently named chair of the state Democratic Party’s Hispanic Caucus. “He’s working it hard and emphasizing outreach,” Ruiz adds.

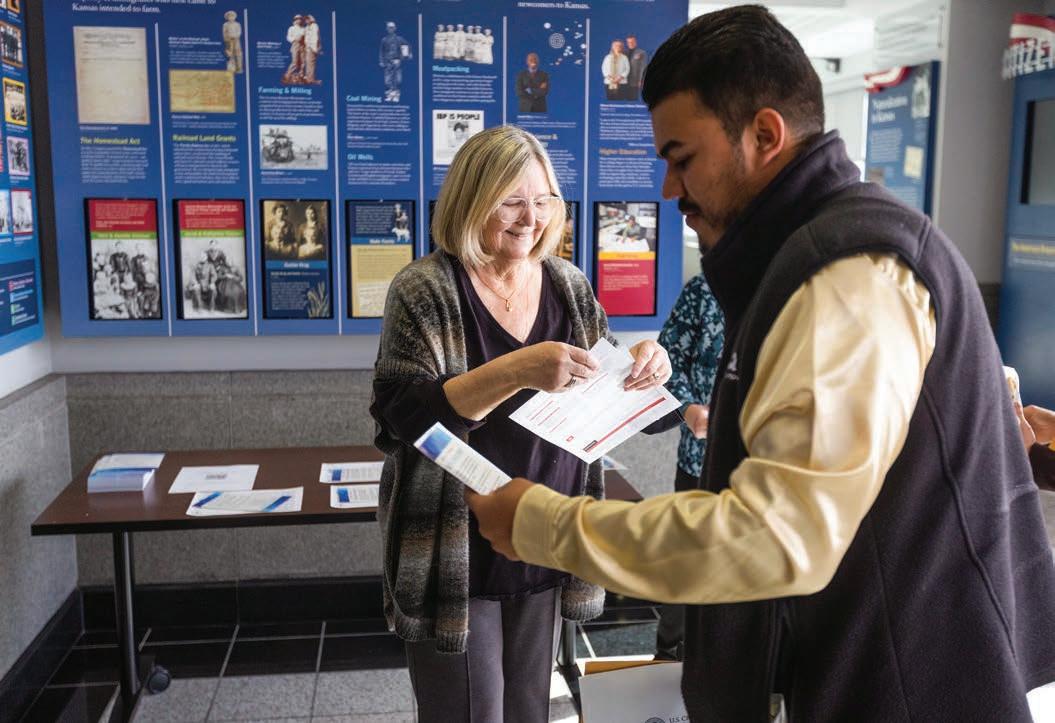

But no matter who is doing the outreach – Democrats, Republicans or nonpartisan organizations – the effort to not only register new Latino voters but get them to the polls requires time, patience and resources. And a lot of knocking on doors – knocks that must happen during campaigns, but also outside the context of campaigns.

“You don’t just build a relationship on one knock,” Caudillo says. “You go and you go back. And you have to ask questions: ‘What candidates have come knocking? What information have you received from candidates? Would you be interested in joining a forum where you can hear these folks?”

At Advocates for Immigrant Rights and Reconciliation, Karla Juarez has received support and a model for outreach from The Voter Network, a Kansas nonprofit organization. The Voter Network promotes an approach called

“relational organizing” to increase voter turnout. The premise driving its work is simple: People are more likely to vote if they have a friend, relative or neighbor encouraging them. “We think our partners and the people who are living and working and breathing in their communities are the best people to talk to the folks around them about voting or politics,” says executive director Lindsay Ford. “That feels intuitive, but it’s not really been incorporated into retail politics.” (Full disclosure: The reporter of this story is friends with Ford and used to work for her.)

Juarez took this message to heart during the 2022 elections and created a team of voting ambassadors. These people know the specific barriers to voting that their friends and relatives may be facing even better than Juarez does. Aiding her efforts is a Voter Network program that features an app that makes it easy for people to build their own cadre of voters and helps them “adopt” other voters. Ford says that program, called Voter to Voter, recruited 88 volunteers in 2020 to reach out to more than 2,000 prospective Latino and Hispanic voters in Kansas. More than half of the people they contacted voted in the November election and had likely never cast a ballot before.

“It’s not about changing hearts and minds,” Ford says. “It’s about changing behavior. People don’t usually change their behavior because they get a postcard in the mail. Those work only on people who already vote, but have little impact on people who aren’t voting or not voting regularly.”

Just as it takes a high level of organization to bring Latino voters to the polls, cultivating new Latino political leaders requires similar efforts. Delia Garcia is among those making that effort. Garcia, who recently served as secretary of labor under Gov. Laura Kelly, was the first Latina elected to the Legislature in 2004. After leaving the Kelly administration, she started a Washington D.C.based consulting firm that focuses, in part, on promoting Latino and Hispanic leadership.

“We can’t wait for other people to save our communities,” Garcia says. To that end, in 2021, she and others used a $25,000 grant from the Kansas Health Foundation (which funds the Kansas

Leadership Center, publisher of The Journal) to start a nonpartisan pilot project aimed at training prospective Latino/Hispanic political candidates. Of the eight who received the training that year, four were elected to municipal offices in Liberal, Topeka and Overland Park. One candidate for the Kansas City, Kansas School Board lost her race.

The pilot proved to Garcia that a relatively small investment can make a difference. But much more will be required, both to train future political leaders and to register voters. “We’re going to have to do the work all year round, every year,” she says.

Following The Engagement Path

As Wyandotte County’s leaders lay the groundwork for greater Latino civic engagement, they have one demographic fact working in their favor: With nearly 28% of Wyandotte’s total population under 18, the county is among the youngest in Kansas, a statistic driven largely by Latinos. Nationally, according to the Pew Research Center, 32% of all Latinos are under 18; nearly 60% are 33 years old or younger. No other racial or ethnic group comes close to those shares. In Wyandotte County, the Kansas City, Kansas School District underscores this trend: More than half of its students are Latino.

Juarez, herself a millennial, says it will be crucial to engage those young Latinos, not just to encourage them to vote, but, as they get older, any children they may have. “It goes back to the subject of people not having good role models,” she says. Inspiring more young Latinos to become civically engaged increases the chances that they’ll pass that value down to their children.

Caudillo is a living example of how that works. “My parents took us all when they went to vote,” she says. “It was important to them. They showed it, shared it and expressed it. I have voted since I was 18 years old. When my kids turned 18, they voted.”

Organizers recognize that building relationships with the younger Latino generation will require delivering messages that resonate with them. Of course, those messages must be tailored to the person, another example of how the relational organizing method can be so powerful. For Negrete, the motivation was all about chipping away at the barriers that make life challenging for so many Latino residents, especially recent immigrants.

“I can tell from being a first generation immigrant, the barriers you have are determined by pure luck,” she says. “I don’t think that’s fair. I don’t think it should be up to luck whether or not your kids have a good school or the needs of your community are being met. When I realized that civic engagement and communication and building bridges was a big path to justice and a more prosperous community, that’s when I became more engaged.”

Discussion Guide

1. How would you diagnose the situation when it comes to Latino political representation? What aspects of the challenge are technical? Which are adaptive?

2. What does leadership look like in this situation?