14 minute read

PLOT TWISTER

IS TORNADO ALLEY STILL A THING? THAT’S A QUESTION THAT HAS FOLLOWED A RECENT LULL IN KANSAS TWISTERS. THE DECLINE MAY ONLY BE TEMPORARY, AND IT DOESN’T MEAN THAT KANSANS DON’T NEED TO HEED ALERTS ABOUT SEVERE WEATHER. BUT THEY MIGHT NEED TO START PAYING MORE ATTENTION TO FLOODING, WHICH KILLS FAR MORE PEOPLE EACH YEAR THAN TORNADOES, AND IS ON THE RISE.

BY: STAN FINGER

Advertisement

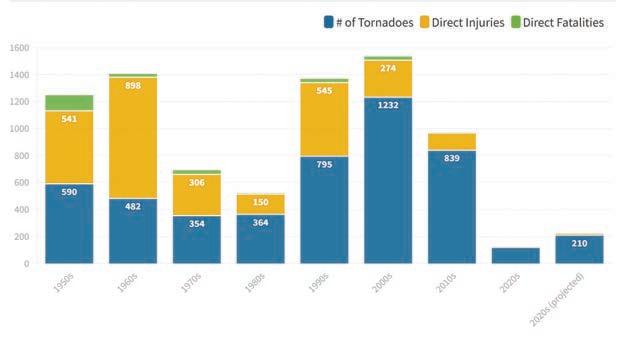

by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Over the past 30 years, Kansas has averaged 86 tornadoes a year. But since 2010, the Sunflower State has reached or exceeded that number just four times.

There were 37 tornadoes in 2021, only 17 in 2020 and 45 in 2018. Even taking into account the EF3 tornado that struck Andover last April, 2022 was quieter than normal for tornadoes, says Jeff Hutton, who served as warning coordination meteorologist for the National Weather Service branch in Dodge City until retiring in December. There were 63 tornadoes across the Sunflower State last year, well below the 30-year average.

tornadoes easy to see and track. The jet stream slows down in late spring and early summer, meaning tornadoes that form will typically be moving slower than they do earlier in the year.

“The idea was, ‘If you want to go see these tornadoes and learn more about why they have formed, you’ve got to go to this Tornado Alley,’” Dixon says. “And it was catchy. It was too catchy.”

Kansas already had a strong cultural connection to tornadoes thanks to “The Wizard of Oz” – after all, Dorothy is transported to Oz by a tornado – and that identity was cemented after “Twister” came out in 1996. (A sequel is planned for release next year.) The movie triggered an explosion of interest in storm chasing, launched a new industry – tornado-chasing tours, drawing people from around the world who are willing to pay thousands of dollars for the chance to see tornadoes up close – and spawned numerous cable television programs focusing on various chasers. Viewers everywhere saw chasers pursuing tornadoes around the Sunflower State.

“Everybody thinks they have their own microTornado Alley in their county, which is completely ridiculous,” Dixon says.

VULNERABILITY IN THE SOUTH, SOUTHEAST

As the new century approached, however, researchers began to recognize that areas east of the Great Plains had a much higher tornado risk.

“That word is pretty fraught and complicated, but … the odds of an individual citizen being impacted by a tornado were much greater in the eastern and southeastern part of the United States than we had ever considered before,” Dixon says.

The risks are higher, he says, because tornadoes are happening there more often than previously thought and they’re happening early in the calendar year, when the speed of the jet stream means tornadoes could easily be moving 50 to 70 miles an hour.

“These tornadoes that happen in north Alabama, if they are on the ground for 10 minutes, they’re probably going to travel 12 to 15 miles,” Dixon says, “where in Kansas, if you get a tornado for 10 minutes (later in the spring) it might travel a couple hundred yards. The footprint of the southeastern tornadoes was much greater.”

Residents in the South and Southeast are more vulnerable to bad outcomes because those tornadoes have a tendency to strike after dark, he says. Those areas also have far more people living in mobile homes and on terrain so hilly and filled with trees a tornado may not be visible until it’s very close.

Researchers have also done some important reevaluation, Dixon says.

“Looking back through our data, we think we’ve been having a lot of tornadoes in the Southeast, back to the ’70s or before,” he says. “We just were doing a bad job of documenting them. Because all research prior to that time had just counted tornado initiation points. They weren’t looking at the full path lengths of the tornadoes.”

A fresh example of Dixon’s point occurred on March 24, when a wedge tornado traveled 59 miles in Mississippi, decimating a small town and killing 26 people. A damage survey by the National Weather Service revealed the tornado was up to about three-quarters of a mile wide, was on the ground for about 70 minutes, and had maximum winds of 170 miles an hour, measuring EF4 on the Enhanced Fujita Scale. he says. But they still deliver rain, sometimes resembling monsoons.

IS TORNADO ALLEY DYING?

Flooding kills far more people every year than tornadoes.

The lull might only be temporary, but tornadoes have been occurring less frequently in Kansas.

Yet danger from severe weather, especially flooding, remains.

At the same time researchers were discovering the Southeast was more prone to tornadoes than previously recognized, they noted a decline in the number of tornado days in the Great Plains – particularly the southern Plains. On the days tornadoes occurred, however, the number of twisters was higher.

“It was a feast-or-famine kind of thing,” Dixon says.

The Dangers Of Flooding

While the number of tornadoes has diminished in the Sunflower State in recent years, the number of rain events has not. Those thunderstorms haven’t produced tornadoes primarily due to “a timing issue,” Hutton says.

The storms haven’t moved through when moisture and instability are ideal for spawning tornadoes,

“We do see a trend of people, when we’ve got a heavy rain event coming in, of just doing the ‘Oh, it’s just rain,’” Korthals says. “And they don’t really think, ‘I need to have the same level of alertness as if it was severe thunderstorms or especially a tornado-conducive environment.’”

People should take rain events and flooding threats more seriously, Hutton said, because floods kill far more people every year than tornadoes, hurricanes or lightning. And flood deaths are climbing too.

“We’re still getting way too many flooding fatalities” around the country, Hutton says. Those numbers “are actually increasing exponentially.”

Since 2000 and especially within the last decade or so, he adds, “We’ve got so many SUVs, fourwheel drive, all-wheel drive vehicles … and people think ‘Wow, now I have 21-inch tires and I can drive through that.’”

They don’t realize how little water it takes to sweep even large vehicles, such as buses and semitractor-trailers, off of a road, he says.

Urban flooding is a growing problem thanks to aging drainage systems, the rapid expansion of asphalt and concrete surface areas, and the resulting “heat island effect,” says meteorologist Kenneth Cook, who’s in charge of the Wichita branch of the National Weather Service.

“There’s more average rainfall around urban centers than there used to be,” Cook says. “That’s pretty widely agreed upon” among weather officials and researchers. “That could be from urban heat islands,” which are domes of heightened temperatures caused by the reflection of the sun’s heat off of concrete and asphalt.

In recent years, Cook says, many cities have seen their average annual rainfall increase by an inch or two. That increased rain results in more runoff into drainage systems built for much smaller population centers, and it’s a recipe for flooding.

“We’re seeing flooding in places we haven’t before, and water levels higher than they’ve been” where flooding has historically occurred, Korthals says.

“I don’t know what the answer is ever going to be” to get people to take the dangers of flooding more seriously, Hutton says.

In his annual severe weather awareness presentations – which for years were known as storm spotter training classes held early in the year to prepare people for tornado season –Hutton says he has made flooding the threat he focuses on first, offering illustrations of just how dangerous it is. By focusing on the impact flooding can have, he says, he hopes the message better reaches his audiences.

Flooding in Kentucky last summer killed at least 39 people and left thousands homeless, and heavy rains in California in January prompted widespread flooding and evacuation orders. Such events serve as a real-world reminder of how quickly flooding can threaten – and take – lives, Korthals says.

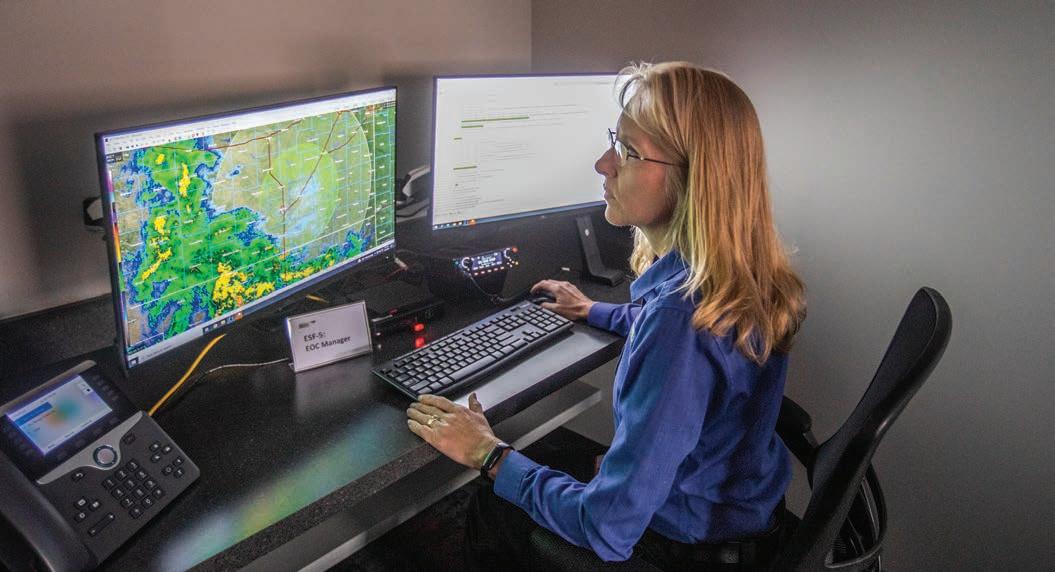

Advancements in technology could help address that, says Kim Klockow-McClain, a research scientist for the Behavioral Insights Unit at the National Severe Storms Laboratory in Norman, Oklahoma.

Researchers are already looking for ways to use GPS to plot multiple vehicles on maps overlaid with flood warnings and make those maps available to app users so motorists could be made aware of flooding threats before they come upon them, she says.

Such flood warning apps “are more complicated because we’re not just talking about a single point – like a storm coming at you,” she says. “You’re looking at something where it’s all this area around you, or water could be rising around you and you don’t know where it is.”

Thunderstorms with the capability of producing tornadoes are easier to observe because radar can readily detect their presence, she says. Flooding is something else, though.

“We don’t have water gauges on every point on the land surface … so we don’t have the ability to tell people where flooding is occurring with any precision. What we’re seeing is: People don’t know that they’re going to drive up on a flooded road until they’re upon it.”

At that point, Klockow-McClain says, there are two major problems:

1. People are “really motivated” to get where they’re going, so they may well risk driving through that flooded road to get home or pick up their children from school or practice. If they need to reroute, they needed to be planning for that an hour earlier.

2. If drivers turn around, they don’t know if it’s going to be any safer because they don’t know where the water in front of them came from. They can just as easily have water behind them or on the alternate route they’re planning to use.

The answer has to be providing people with the information they need far enough ahead of time to avoid getting into those conundrums in the first place, she says.

“It’s a complicated decision scenario that you find yourself in and you don’t have, necessarily, easy solutions. We encounter water on the road all the time. And if we want to do better at this, we really do need better detection technologies like what they’re trying to develop for cars.”

The technology being developed would allow “smart cards” in vehicles to communicate with one another to alert others to flooding.

“Imagine having a map display on your computer or on your dash, where if there are cars around you that are getting stuck in water, or having to go through like some high level of water, the sensors can detect that you’re going through that. If you were able to see that on a map, and it’s up ahead of you, imagine what you could do. You could look at that and say, ‘Route me somewhere else.’”

With more sensors in and near streams and floodplains, she says, emergency managers could start to take steps such as having warning signage alerting motorists and perhaps even closing roads ahead of time.

For example, the Kansas Turnpike Authority installed larger drainage culverts and warning signs at mile markers 116 and 118 south of Emporia, where deaths occurred 15 years apart. Six people – including five members of one family – died in a flash flood along Jacob Creek at mile marker 116 over Labor Day weekend in 2003. Torrential rains caused water to rise and cover the turnpike after sunset on that Saturday. A number of vehicles became stranded in the water and were swept away by a wall of water estimated to be more than six feet high.

One person died in 2018 two miles away when his vehicle hydroplaned off the turnpike after hitting standing water and went into the ditch, where surging floodwaters sucked his vehicle into a culvert.

Korthals says she agrees that more sensors are needed in flood-prone areas, and Butler County has requested additional sensors from the weather service. Such requests are on something of a wish list for emergency managers, she says, waiting for additional federal funding.

In 1998, flooding swamped south central and southeast Kansas after nearly 11 inches of rain fell in some locales. Augusta, above, was particularly hard hit. More than 550 homes, 200 mobile homes and 100 businesses were damaged. In the 12 counties that sustained damage, losses were put at more than $30 million, according to the National Weather Service.

A few years ago, the National Weather Service moved to the Wireless Emergency Alert system to issue flash flood warnings. It’s a public safety system that allows customers who own compatible mobile devices to receive geographically targeted text messages alerting them to imminent threats to safety in their area.

Chance Hayes, warning coordination meteorologist for the Wichita branch of the weather service, says officials there have been pleased with how the alert system has worked.

But there are limitations: Participation in the system by service providers is voluntary, and not every device offered by a provider has the capability of receiving the alerts. That creates the potential for one person to receive an alert and someone standing right next to them not getting it – simply because they use different providers or have different phones.

People who want to receive those public safety alerts should check to see if their provider participates and their phone is able to receive them, Hutton says.

There’s room for improvement in tornado forecasts as well, officials say.

According to the U.S. Department of Commerce, tornado forecast accuracy has fallen from 75% in 2011 to 62% in 2021 – a decline of more than 17%. Several times in that period, the accuracy rate dipped into the 50s.

Those statistics are misleading, says Mike Muccilli, acting severe program manager for the National Weather Service. The weather service separates longer track, stronger tornadoes – typically classified at EF2/EF3 and stronger on the Enhanced Fujita Scale – from weaker, short-lived tornadoes. Tornadoes that have winds of at least 136 miles an hour are classified as EF3 on a scale that goes up to EF5, a classification given to tornadoes with winds of more than 200 miles an hour.

“The National Weather Service is exceedingly successful in warning for these EF3-plus tornadoes and has either maintained or improved year over year in both probability of detection (accuracy) and lead time,” Muccilli says. “We have seen a decline in deadly tornadoes given the increased warning success and lead time for these stronger tornadoes.”

The probability of detection for tornadoes rated EF3 or higher from 2017 to 2021 ranged between 91% and 96%, Muccilli says. The lead time for these same years for EF3-plus tornadoes increased from 16.3 minutes to 20.2 minutes. The false alarm rate, meanwhile, has continued to drop and meets desired metrics, he says.

“The largely short-lived, low-end tornadoes do still remain a challenge, and statistics do show a relative plateau in both lead time and probability of detection for these,” Muccilli says.

There are naturally many more of the weaker, brief tornadoes, he says, and “every tornado is assumed to be life-threatening, even the ones that are hard to detect.”

But there are disagreements about how much lead time people need in advance of tornadoes, and whether earlier warnings are needed or even helpful.

Peer-reviewed research shows that the ideal tornado warning gives those in harm’s way 13 to 15 minutes to get to shelter, according to Mike Smith, a meteorologist who worked at Wichita’s NBC-TV affiliate for many years before leaving to establish WeatherData, a private forecasting service that has since been acquired by AccuWeather. Beyond 15 minutes, data shows, fatalities increase.

“That is counterintuitive,” Smith says. “But if you think about it, it only takes 30 seconds to gather up the kids and run into the basement. If you’ve got a storm shelter in your garage as some people do, or a safe room, that might take a-minute-and -a-half, two minutes. If you’re using a bathroom tub in the middle of the house, that may take three or four minutes to get everybody in the bathroom and a mattress into the bathroom. There’s really nothing that takes more than three, four minutes, if you’re home.”

Researchers are concerned current warnings don’t provide enough time for those who don’t have adequate sheltering options or have significant mobility issues. It could also include those who are picking their children up from school, Klockow-McClain says. Schools in Kansas commonly have tornado shelters, but that’s not always the case elsewhere.

“We know that there are some people – it tends to be the most vulnerable of our society – that lack that access to really good sheltering options,” Klockow-McClain says.

Current warning lead times aren’t sufficient for those vulnerable populations to get to proper shelter elsewhere, she says. She would like to see technology advance to where meteorologists could issue something in between a watch and vulnerable populations would have time to get somewhere safer.

Smith says he recoils at suggestions more layers are needed in the warning system, which he considers to already be too complicated and confusing – for meteorologists and the public alike.

“The whole purpose of the tornado watch is to give you advance notice so that you’ll be in a relatively good place when the tornadic thunderstorms arrive,” Smith says. “We have neither the science nor the technology to do accurate one-hour tornado warnings. That’s a fact. I don’t think we should try to get there. But if we wanted to try to get there, it would take a denser weather observation network than we have now.”

While the number of tornadoes and tornado days in Kansas and the Great Plains has declined over the past decade or so, Hutton and other officials aren’t ready to write Tornado Alley’s epitaph just yet.

“This sounds really, really familiar to a big old conversation that blew up around 1989 and 1990, that the central states are no longer Tornado Alley” because of a notable decrease in tornadoes over the previous several years, Korthals says. “Then, all of a sudden, we have the years of tornadoes, 1990 and 1991. ‘Oh, thank you, Mother Nature for clarifying that. We don’t know what we’re talking about.’”

Those two years saw a massive surge in tornadoes, including deadly EF5s that struck Hesston in 1990 and Andover in 1991.

This recent quiet spell for tornadoes may lure Kansans into a false sense of security, Hutton says.

Discussion Guide

1. How could the declining number of tornadoes affect perceptions of severe weather threats? What might make this an adaptive challenge?

2. What threats concern you the most in your own context? How do you know which threats represent the biggest danger?

“We’re going to catch one of the really, really bad years that Wichita’s going to get hit or Hutchinson or Topeka,” he says. “Some big metropolitan area’s going to get nailed eventually.”

While significant tornado outbreaks have at times prompted concerns that “this is the new normal” because of climate change, Hutton and other weather officials say research has found no meaningful connection between global warming and tornado development.

“Regardless of if we have global warming or not, there’s no evidence whatsoever” of such a link, Hutton says. “You can’t prove that it’s increasing or decreasing.”

Perhaps the most significant reason for that, he says, is that climate is a big-picture view of the weather that typically spans 30 years at a minimum, he says – and the formation of tornadoes is dependent on conditions being just right at a particular moment in time. That’s why persistent stories claiming global warming is driving increases in the number and intensity of hurricanes and tornadoes make him want to pull his hair out, Hutton says.

“It’s the most frustrating thing I’ve dealt with in my 39 years of forecasting weather,” he says.

While some types of extreme weather, such as heavy rainfall or extreme heat, can be directly attributed to global warming, “the role of climate change in altering the frequency of the types of severe weather most typically associated with the southern Great Plains, such as severe local storms, hailstorms and tornadoes, remains difficult to quantify,” according to the Fourth National Climate Assessment report from 2018.

Data over the last 30 years indeed shows the number of violent tornadoes is decreasing. The number of outbreaks isn’t increasing, either. Yet, rather than consigning Tornado Alley to the dusty pages of history, Hutton says, Kansans should simply be grateful for this relatively quiet stretch. It won’t last – Tornado Alley will one day reawaken.

“It’s going to come back,” Hutton says. “There’s no reason why it won’t.” by Jeff Tuttle

April 26, 1991, turned out to be a deadly day in Kansas after supercells developed in Oklahoma and moved northeast. Altogether 55 tornadoes formed that day. The most devastating one churned through Haysville and McConnell Air Force Base before striking Andover, killing 17 people and leveling 300 residences. By the time the tornado reached the Golden Spur Mobile Home Park in Andover, it had reached the F5 level on the Fujita scale.