In good spirits

Alcohol-based businesses contribute to Upper Valley economy and tourism

Alcohol-based businesses contribute to Upper Valley economy and tourism

6 AUTO OUT OF SERVICE Vital Communities director shares her week of being without her car.

10 Q&A WITH DIS TILLERY Silos doubledown on Vermont made spirits with locally sourced ingredients.

16 BRE WING BUSINE SS Brewers, industry experts say other breweries streng then market

21 SPIRIT OF T OURISM Breweries, wineries and distilleries help fuel tourist economy.

: A TOAST Friends participate in a Wine 101 class at Putnam’s vine/yard in White River Junction. 4 ELEC TRIC AV ENUE Advance Transit is rolling out electric buses with reduced emis sions.

COVER PHOTOGRAPH: Natalie Looney, of White River Junction, examines the color of a glass of wine during a Wine 101 class at Putnam’s vine/yard.

PHOTOGRAPHS BY ALEX DRIEHAUS, VALLEY NEWS / REPORT FOR AMERICA

Specializing

Infant

Pre-

Largest

Eyeglass accessories

Designer & sport sunglasses

Medicare

It was a moment years in the making and one that everyone at Advance Transit (AT) had long been looking forward to.

In mid March, AT placed two electric buses in service to offer passengers a quieter ride with reduced emissions. These vehicles are the first set in a series of planned changes, with more electric vehicles slated to arrive by next year.

“Don’t you just love that new bus smell?”marveled AT Executive Director Adams Carroll as he stepped into one of the newly acquired electric buses around a month ago. Carroll, who rides AT regularly, was eager for his morning commute from his home in Lebanon to the AT office in White River Junction.

AT started to add hybrid buses to its fleet in 2011. In 2019, the nonprofit was awarded a $3 million grant from the Vermont Agency of Transportation (through support from the U.S. Department of Transportation) that helped accelerate its efforts to add electric buses. As the Valley News reported in July 2019, the federal grant was intended to reduce air pollution and decrease carbon emissions.

AT anticipates adding more electric vehicles to its fleet, including two more 35-foot electric buses in the summer of 2024, as well as three electric cutaways —vehicles used for paratransit service and Dartmouth College shuttles —in the future.

With better air quality comes improved health. In February 2023, the journal Science of the Total Environment published a study conducted in California by a team of researchers from the Keck School of Medicine of USC. Their work revealed that as electric vehicle adoption increased, air pollution levels and asthma-related emergency room visits decreased.

Indeed, there are many benefits to electric vehicles, from a smoother ride to a long-term environmental impact. The transportation sector accounts for 27% of greenhouse gas emissions, generating the largest share compared to other sectors, such as electricity production and agriculture, according to 2020 data from the United

In addition to the environmental and health benefits, electric buses provide a more comfortable ride. Without the traditional exhaust system and with fewer moving parts, e-buses perform more smoothly on the roads and with reduced noise. They also have lower operational costs compared to their petroleum-powered counterparts.

States Environmental Protection Agency. This stems primarily from the use of fossil fuels. Working with Green Mountain Power, AT aims to reduce these numbers for the Upper Valley through the implementation of electric buses.

In addition to the environmental and health benefits, electric buses provide a more comfortable ride. Without the traditional exhaust system and with fewer moving parts, ebuses perform more smoothly on the roads and with reduced noise. They also have lower operational costs compared to their petroleumpowered counterparts.

Some riders have noticed the difference and have commented on the quieter experience, drivers say. AT driver Chris Hartzell shares that while the buttons and switches on

electric and diesel buses are similar, “the new buses accelerate better and have greater power than the diesel buses. They ’re a lot smoother, a lot quieter and a lot easier to handle.”

After AT received funding, the COVID-19 pandemic and supply chain issues delayed the delivery of its electric buses. Soon after the vehicles arrived, in the fall of 2022, AT had to take steps to make sure the buses were road-ready, such as maintenance checks, driver training and the implementation of a new fleet monitoring software.

Additionally, AT is in the process of building an electric charging station. Scheduled for completion this fall, the charging station will be the most significant facility upgrade since AT’s building expansion in

2009. This operations center addition will accommodate the current electric vehicles and future ones, laying the groundwork to buy more e-buses and support long-term goals for more sustainable business practices.

“This is only the beginning,”Carroll said. “We’re excited about the impact that electric buses will have on the community and the overall effects on the environment. We look forward to growing the number of electric vehicles in our fleet over time.”

AT has long-regarded sustainability and environmental stewardship as key parts of the organization’s mission. The transit agency currently uses three hybrid buses in its fleet, as well as electric cars that function as driver relief vehicles. It has implemented systems that both reduce operating costs and produce real environmental benefits, such as actively harvesting rainwater that is used to wash buses. AT’s LEEDcertified facility also features a solar array and a system for recycling used motor oil into a heat source.

The organization’s commitment to sustainability and service is evident in the message displayed on the rear window of its electric buses: “Electric-powered. Community-driven.”

NORWICH,VT• 802-649-1234 •OFFICE@DG123

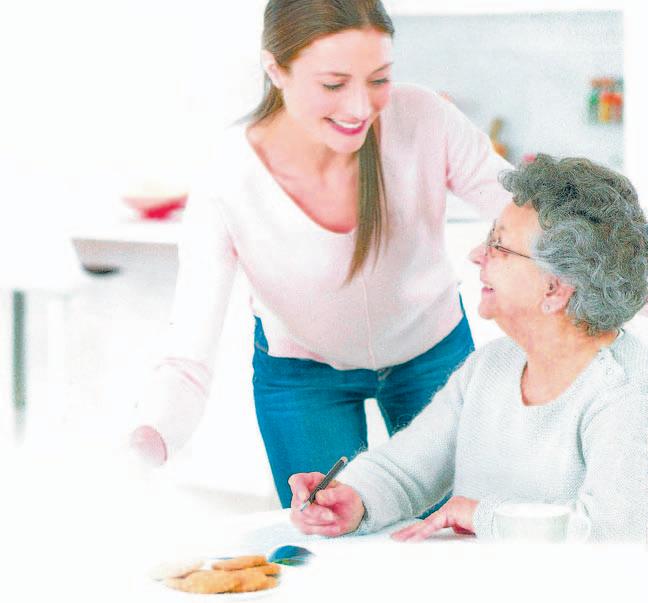

By REBECCA BAILEY Vital Communities Communications Director

By REBECCA BAILEY Vital Communities Communications Director

It all began one December dusk on a quiet back road when a deer met the front of our car.

My spouse and I were driving slowly, so the deer was able to scamper away, but our car suffered a cracked headlight and damaged front bumper. After calls and estimates, we were given a repair appointment in late February which would require leaving our car at the body shop from Monday through Friday —our only car, which we supplement with an e-bike and an aging truck we share with a neighbor.

No car? No problem, thought I. The Upper Valley has far more public transit than many people realize, and it’s growing. In the “four-town core”of Lebanon, Hartford, Hanover and Norwich, there’s Advance Transit (AT), which also serves Enfield and Canaan. Radiating out from the core are lines run by Tri-Valley Transit (TVT), with service along the I-89 and I-91 corridors north of the fourtown core, plus local trips in Orange and northern Windsor counties; Southeast Vermont Transit’s MOOver, with service along I-91 south of White River Junction, local trips in southern Windsor County, and the new MicroMoo ride-hailing pilot in the Town of Windsor; and Southwestern Community Services, serving Claremont, Charlestown, and Newport.

Most service takes place Monday through Friday, early morning to late afternoon, which doesn’t work for many transportation needs. But the schedule has been expanding: AT recently increased frequency along some lines and is exploring evening service. TVT now offers midday service to and from the core towns along the I-91 route, meaning you can go into the core for half the day instead of a full day, which makes the bus service good for doctor ’s appointments and shopping in addition to 9-5 job commutes.

TVT also has extended its routes in recent years. Residents of Strafford like me used to have to drive to Thetford or Sharon to reach the nearest bus stop. In 2021, however, TVT added the “Thetford Connector ”line linking the Thetford and Sharon Park and Rides, passing through South Strafford.

Although the Thetford Connector

and the Chelsea Extension (which runs between Sharon and Chelsea) were part of a service expansion to serve area high school students get to school, those lines also operate yearround and accept all passengers.

Leading up to my carless week, I was already an old hand at the bus commute from South Strafford to our office in White River Junction. I had established a tidy routine: Drive or e-bike to the South Strafford Park and Ride, catch the Thetford Connector at 7:48 a.m., get the Sharon Park and Ride at 8, leave on the 89’er South at 8:05, and arrive at the VA Hospital in White River Junction at 8:15. Ask the driver to drop me at the Greyhound Station instead, so I don’t have to walk the portion of Route 5 from the VA to the Sykes

Mountain Avenue roundabout, which has no sidewalk and two lanes to cross of cars streaming off the interstate. After that, the walk is fine, with pedestrian crossing lights at the roundabout and a continuous sidewalk along one side of Route 5.

Yes, the AT Orange Line goes from the VA to downtown White River Junction, but at that time of the day the next one isn’t until 8:43 a.m. So I always opt to walk from the Greyhound Station.

In the afternoon, however, an orange bus is perfectly timed to get me to the VA for the 4:50 p.m. 89’er to Sharon and the Thetford Connector, arriving in South Strafford at 5:21 p.m.

For my carless week, I would also use the bus to get to Chelsea Thursday evening to meet a carpool to an event in Montpelier. Since the next bus leaving Chelsea would not be

until 7:25 a.m. Friday, I would need to stay overnight with a friend in Chelsea and get a ride to the Friday morning bus to White River Junction —and our car.

So, I didn’t dread my carless week. I had a plan. Plus, public transit makes me happy. I like reading bus and train schedules. I like packing a backpack and choosing shoes and outerwear for a day on foot and riding public transit. I counterbalance the inconveniences of public transit by savoring the pleasures of not having to drive or find parking, getting more walking and reading time and supporting a system I feel is part of a better future for us all.

Monday

On a sunny Monday morning, I

drove our car to the autobody shop, crossed Route 5, and walked to the bus stop in front of the VA in time to catch the 7:43 a.m. Orange AT bus to the office. Easy peasy.

In the evening, when I boarded the 89’er at the VA, I asked the driver to radio the Thetford Connector and tell them I would be riding it. Why? Because it turns out TVT drivers keep track of who rides in the morning so they can make sure those riders get home in the evening. Since I hadn’t ridden in the morning, I needed to give word to the Thetford Connector driver to wait in case the 89’er was delayed.

I had learned how carefully TVT tracks its riders in January when I boarded the 89’er at the VA one stormy evening and the driver asked

if I was going to Strafford. Yes, but why was he asking? Because conditions on 132 from Sharon to Strafford were so bad, TVT had canceled the last Thetford Connector run. However, so I wouldn’t be stranded in Sharon, a TVT employee was coming from Randolph to drive me to South Strafford. That’s how seriously they commit to not stranding riders.

I was picked up by my spouse in the aging truck. Day 1 down.

Thursday

Days two and three were remotework days, so my next bus travel day was Thursday. In contrast to Monday, that morning saw the remains of a big sloppy storm. My spouse dropped me at the South Strafford Park and

I counterbalance the inconveniences of public transit by savoring the pleasures of not having to drive or find parking, getting more walking and reading time and supporting a system I feel is part of a better future for us all.

TR ANSPORTATION FROM 7

Ride, my backpack carrying not just my computer, but overnight supplies and a change of clothes.

Six inches of precipitation the consistency of melted cream cheese slowed traffic; for the first time in my TVT riding experience, the bus was late. But I knew the bus would come at some point because I am signed up to receive service alerts from TVT about changes and cancelations, and I had received none. When the bus rolled up, 12 minutes late, I asked the driver to radio the 89’er in Sharon to wait. He did, and I got my bus to the usual Greyhound

station detour stop.

On my return that afternoon, I asked the driver to radio the Chelsea Extension bus at the Sharon Park and Ride so the driver would know to wait for me. Boarding the Chelsea bus with three silent, exhausted-looking high school students, we made it to Chelsea at the scheduled time of 5:40 p.m., I met my carpool, and we went to Montpelier and back, ending with an overnight in Chelsea.

Friday

My Chelsea host decided she needed to go into the core of the Upper Valley, so we lingered over coffee

rather than rushing me to the 7:25 a.m. bus, and she drove me to work. In the late afternoon, it was time to pick up our car and head home. Inattentive to time, I missed the 4:03 p.m. AT Orange bus. I would have to walk —including that stretch of Route 5 I’d been avoiding.

You know how that turned out: I made it. (I wouldn’t be writing this if I hadn’t.) I watched for a break in the streams of cars from the interstate and traversed the off ramps, then hugged the Route 5 shoulder ‘til I reached the body shop driveway.

I picked up the car and headed home. Along with a repaired car, I had a few lessons to take home from

my not carless but certainly “less car ”week:

■ Using public transit successfully takes practice and planning.

■ Our local public transit is reliable and takes care of its riders.

■ Most people in the Upper Valley could replace some of their car trips with public transit rides.

But they can’t replace all of them, yet, and that makes it hard to have no access to a car.

The more we use the public transit we do have, the more it will grow into a real alternative to car dependency.

Three cheers for backpacks, sidewalks and sensible shoes.

Rt. 4, Enfield, NH 603-632-5757

195 Mechanic St., Lebanon 603-727-9153 www.vanessastonere.com

To Be Built by Seller/Builder with BUYER’S CONSTRUCTION LOAN or CASH. North Village parcel sited in the quintessential Shaker Village. Views and rights in common with others to Mascoma Lake! Rights to common beaches -Brother’s (Closest) & Bowl - on Mascoma Lake! Boat slips to Lease When Available. Canoe/Kayak Racks. Walk to Shaker Museum, Shaker Recreation Fields, Shaker Dog Park, Shaker Mountain & LaSalette. Build your ideal home in this beautiful setting!

NE-413662

Lempster/Goshen Gravel Pit Estimated 1,500,000 Yards of Material to include concrete sand, septic sand, sand, gravel, gravel stone & top soil. Circa 1900’s post & beam cape With Field Facing Deck. 60’ x 80’ Commercial Garage With 22 foot High Ceilings. 70.8 Acres of Open Pasture, Sugar Maples, Timber Land, Hiking/Snowmobile Trails & Gravel Pit. Dug Well & Septic System Service the Cape. Drilled Well & Septic System Service the Commercial Garage. All in one purchase for your own gravel business and homestead!!

v

v

v

OWNER.

This year we paid $117 million in patronage dividends.

Farm Credit East is customer-owned, which means customers share in the association’s financial success. This year, qualifying borrowers received $117 million from our 2022 earnings. That’s equivalent to 1.25% of average eligible loan volume and adds up to $1.3 billion since our patronage program began.

Discover the difference. No other lender works like Farm Credit East.

farmcrediteast.com 800.562.2235

v

v

v

v

v

v

v

Loans & Leases

Financial Record-Keeping

Payroll Services

Profitability Consulting

Tax Preparation & Planning

Appraisals

Estate Planning

Beginning Farmer Programs

Crop Insurance

By PATRICK O’GR ADY Valley News Correspondent

By PATRICK O’GR ADY Valley News Correspondent

Silo Distillery began operating in Windsor ’s Artisans Park in May of 2013. It was started by Peter Jillson and Anne Marie Delaney. Silo —a name chosen as grain silos are ubiquitous symbols of farms in New England and the Midwest —makes several unique spirits that highlight Vermont-grown ingredients.

Delaney recently offered some insights into Silo’s origin and its operation.

Question: How did Silo begin and why did you choose Vermont?

Answer: We decided to come to Vermont because Peter, an eighth generation Vermonter, wanted to do something that involved what was grown here in Vermont.

Q: So Silo uses Vermont ingredi-

ents?

A : Yes. We buy all our grain from a farm in North Clarendon where they grow corn, wheat and rye for us and deliver it in 50 lb. bags. We do everything here. We are also one of the few distilleries that make their own spirits and it has worked out really well.

Q: What are some of the spirits that Silo makes?

A : Silo makes vodka from 100% gluten-free non-GMO corn. We distill the vodka and infuse it with freshpeeled cucumbers from Vermont when they are available and a vodka infused with lavender flowers from a farm in Derby, Vt. We also distill a gin we call Windsor gin, adding juniper berries and angelica root with a gentle infusion of cucumber and

we make a cider using Vermont apples.

Q: Which of your spirits is the best selling?

A : The lavender vodka is the favorite vodka but the one we sell the most of is the maple whiskey. People associate maple syrup with Vermont so consistently that is our biggest selling spirit.

Q: Do you have plans to introduce any new spirits?

A : We are always learning and thinking about what else we can do so we are always experimenting. When strawberries come in (in Vermont) we get them locally and we make a lovely strawberry vodka. When raspberries come in in the fall we make raspberry vodka. So we are constantly doing seasonal vodkas. We also have done a whiskey from wheat called Aisling that is aged with ash wood and we make a bourbon whiskey we got a double gold medal for.

Q: What are some of the challenges to the distilling process to consistently produce a high quality spirit?

A : It really is the ingredients. The grain is consistently good and the water is from Windsor and it has a spring source. We bought the distilling equipment from Germany in 2010 and at the time it was the best distilling equipment available. We also have controls and alarms that go off if something goes wrong during the process.

Q: Can you explain how someone learns to be a distiller?

A : To learn the nuances and fine detail it takes a few years. Understanding the equipment and how each component works in concert requires practice. The secret of producing a quality spirit lies in making the correct head, hearts and tail cuts. Initially bitter tasting and pungent it becomes dry to the touch with a clean aroma. Then you know you have produced the best of the best. Peter is the distiller and has that now to a fine, fine point.

Bar Harbor Bank & Trust helped John Tauriello purchase Wallace Building Products in 2012. We continue to provide financing solutions tailored to his needs, which helps John stay competitive and keep up with demand. He was able to increase productivity with new equipment, and improved cash flow by using a line of credit. To see this and other success stories, go to www.barharbor.bank/success-stories. Call 603-843-6811 today to connect with our Commercial Banking team.

The one we sell the most of is the maple whiskey. People associate maple syrup with Vermont so consistently that is our biggest selling spirit.

By PATRICK O’GR ADY Valley News Correspondent

By PATRICK O’GR ADY Valley News Correspondent

When Dierdre Heekin began bottling wine at her Barnard winery La Garagista in 2010, she did not include the name of the grape on the bottles.

“When we started it was hard to get people to try a Vermont wine because there was a bias about that,”Heekin said. “So we started out by not putting the grape variety on the label because we didn’t want people to think about hybrid varieties at that time because they definitely thought it was something they were less interested in.”

Heekin said the bottles only introduced the wine as red, white, rosé or sparkling.

“We wanted people to drop those considerations (of asking) is this a Pinot? Is this a Chardonnay? Our goal was to make something engaging enough for people to want to come back,”Heekin said. The results have been what Heekin and other Vermont wineries had hoped for.

“Vermont wine has really taken off, particularly in the last five years,”said Heekin, who owns La Garagista with her husband, Caleb Barber.

While it may never surpass the reputation for wine in places like California, Italy or France, Northern New England is developing a following among wine lovers, thanks in large part to the development over the last 20 years of cold weather hybrid grapes.

Research at the University of Wisconsin, University of Minnesota and Cornell University led to several grape varietals for both red and white wine. The first vineyards were planted in New Hampshire in the early 1990s and in Vermont several years later. Today, there are about 20 winemakers in Vermont and 30 in New Hampshire —and that number is expected to increase with hardy varietals. Additionally, wine producers in colder regions could play a part in addressing climate change’s impact on the industry —which has already affected makers in California and France, among other locations.

“With climate change, hybrid varieties are becoming something important to that conversation,”Heekin said. “The work being done in Vermont and all over the Northeast is becoming a model on how we can start thinking about the future, which is an exciting time for us to be working in wine here in the Northeast.”

Heekin learned about wine from a hospitality perspective as the wine director at Osteria Pane e Salute, the Woodstock restaurant she owned with Barber. She then began making wine at home to learn about the fermentation process and that led to an interest in vineyards.

A flight of wines are poured for a Wine 101 class led by wine educator andsommelierVictoriaTuzetat Putnam’s vine/yard in White River Junctionlast month.Tuzetsaid sheplanstoexpand herclass offerings to go beyond the basics, focusing on topics like wines from specific regions or those made from particular grapes.

W INE FROM 12

“I have long been a firm believer that wine is made in the vineyard, not the cellar,”Heekin said. Heekin planted her first vines in Barnard in 2007.

“When I did that, I realized that was what I wanted to do,”Heekin said. “I wanted to be growing and making wine and be able to say what a place like Vermont has to say as a serious wine region.”

Today, La Garagista grows grapes in two vineyards in Barnard and two in the Champlain Valley area. The vineyard’s first vintage was bottled in 2010. The vineyard’s Italian name translates to mechanic —or woman who makes wine in her garage.

“That is how I began,”Heekin said.

The couple closed the restaurant in 2017to focus solely on the winery, which includes flower, vegetable and herb gardens.

With no pre-established rules for winemaking in Vermont and New Hampshire, Heekin said there’s more “creative freedom.”

“What is exciting about that is as producers we get to try all different kinds of traditional techniques in winemaking with these varieties to see how they respond,”Heekin said. “Techniques that

help these wines tell a story about where we live. For me, I have found every technique we have used has been interesting. Hybrids to me are very flexible. They don’t make just one kind of cookiecutter wine.”

Robert Elliott, president of the New Hampshire Wine Association and owner of Squamscott Winery in Newfields, N.H., said it has been a challenge to convince wine lovers to consider something besides well-known grapes like Chardonnay, Pinot Noir and Cabernet Sauvignon. Elliott said most people who consider a New Hampshire wine are not familiar with the names of the varietals grown in cool and cold climates.

“Many times a visitor will come in and ask for a vinifera varietal, such as a Chardonnay, or Cabernet Sauvignon, which we can’t grow,”Elliott said. “New Hampshire is a fairly new —and growing — wine producing region. Many visitors are surprised to learn that we can grow our own grapes and make many styles of white, red and rosé wines.”

New Hampshire state liquor stores have a section devoted to New Hampshire wines, which have won awards outside the state, Elliott said.

“We hope that when they buy it, they will want to visit the winery,”Elliott said.

The web site of the N.H. Wine Association, with

25 member wineries, lists 13 cold climate varieties, which likely do not resonate with most wine drinkers. These include white varietals such as Brianna, the newest white cold hardy grape; Cayuga, a French-hybrid grape; Chancellor; and reds such Frontenac and Marechal Foch, described as “the most popular and widespread red grape throughout northern states and Canada.”

Kendra Knapik, recently elected president of the Vermont Grape and Wine Council, which advocates for the state’s winemakers, said Vermont producers initially tried to apply the same processes to these new varietals that are used with well-known grapes.

“They were trying to make them into something else,”Knapik said

She credits Heekin and others with bringing a more natural and organic approach to growing the region’s grape varietals with less intervention.

“Dierdre helped teach that you can make really good wine from these different varieties if you let them show their true colors,”Knapik, who owns Ellison Estate Vineyards in Grand Isle, Vt., said. “So there is a new wave of winemakers that have this more natural focus.”

Elliott said for growing grapes there are three

distinct climates: hot, cool and cold. New Hampshire’s coastal area is cool but to the north and west, cold takes over.

Hybrid grapes for both red and white wines have been developed to not only survive temperatures as low as minus 45 degrees but also are resistant to disease caused by too much rain and humidity, conditions prevalent in the Northeast.

“Fungal diseases in grapevines are more prevalent in humid climates like Northern New England, so we try to help the vineyards become more naturally resistant to these diseases,” Heekin said. “Of course, we are working with varieties that already have some native resistance, so they have a leg up, but they are not immune, and the farming is often focused on methods to help the vines in humid circumstances.”

Wine as a story

Kelsey Rush does not grow grapes or make wine, but she is no less of an oenophile. About three months ago Rush opened Putnam Vine/yard in the historic 1930 railroad building in White River Junction that was previously home to the Engine Room. In her approach to wine, Rush looks beyond the taste of a good glass of wine to the story behind it.

“There are so many interesting stories with wine,”Rush said one morning at Putnam’s. “It is very easy —no matter what your intellectual passion is —to find some nugget with a bottle of wine and want to learn more about it. I think that curiosity is super interesting.”

Rush, a Dartmouth College graduate who returned to the area after several years in California’s health care tech industry, said she enjoys learning about wine as much as she does having a

glass. That interest led her to obtain her Court of Master Sommeliers certificate, which is awarded to those who have demonstrated an exemplary knowledge of wine.

“I did it mostly for fun,”Rush said. “I love tasting wine and the stories of winemaking. It felt like

I was drinking a story and I love that.”

Looking for a “passion project,”to share her love of wine and its history, Rush signed the lease on the space for Putnam’s about a year ago and completed all the renovations —including painting and wallpapering —herself.

Victoria Tuvet, the sommelier and wine educator at Putnam’s, said the business rotates out its monthly wine menu with a theme such as a California road trip, a color theme- red, white, rose, orange and more recently, southern hemisphere.

“It has been fun to pick and choose what we think would be interesting,”Tuvet said. “We also try to showcase women-owned or family-owned wineries.

“There is definitely an interest in learning more about winemaking here. People have a lot of questions.”

At Putnam’s, which also serves coffees, teas and regional craft beer, Rush holds wine tasting classes on what was a performance stage.

“We call it educational drinking,”Rush said. “We lean into that here. We have prepared stories and notes from all the glasses we pour. We want wine with a story behind it and only drink the people and stories we find interesting.”

Knapik, with the Vermont Grape and Wine Council, said Vermont wines have been featured in The New York Times, Travel and Leisure, and Food & Wine and that bodes well for the future of the state’s wine industry.

“We realize this could be an important industry for Vermont,”Knapik said. “It is an exciting time to be in Vermont winemaking and New Hampshire as well because there is renewed energy to embrace varietals grown here.”

Patrick O’Gradycan bereached atpogclmt@ gmail.com.

We all love beautiful sunny days. A time to be home enjoying family and friends. As we venture out onto our decks and patios, we realize the hot sun and UV rays can make our outdoor space uncomfortable.

SummerSpace® awnings will transform your sunny space into a relaxing shaded oasis. Join the thousands of families who have taken this journey with us. We invite you to explore all the possibilities of outdoor comfort! You work hard, and you deserve the home of your dreams.

Let us make your dream a reality.

Mark Babson did not wake up one morning and decide to open a craft brewery. He paid his dues in the industry for many years before starting River Roost Brewery in White River Junction in 2016.

“I got started the way a lot of people start,”Babson said in a phone interview. “I was a pretty avid home brewer.”

Realizing his hobby was becoming a passion, Babson took a job with Magic Hat Brewing in Burlington to learn the ins and outs of brewing. After a stint with another craft brewer, he struck out on his own.

“I was really into it and figured I could do it,”Babson said. “I had a line on some equipment and found a spot in White River Junction. It was pretty much a bare-bones operation. I had three fermenters. I ran the retail shop. My parents would come in to help. But it has worked.”

Today, Babson’s small brewery has gained a following locally and often sees mountain bikers, skiers and tourists stop by.

“We’re going through an expansion and will add a tasting room,” Babson said.

Babson’s success has been mirrored across New Hampshire and Vermont in the last 10 years with what can only be described as explosive growth in the craft brewing market. While not all who open a craft brewery succeed, failures of brewpubs, which serve beer that is brewed on the premises, have been more than offset by successes. And, according to the Brewers Association, profit margins can exceed 70%.

There were 4,800 craft brewers in the United States in 2015. Six years later that figure climbed 90% to 9,118. Vermont’s 68 craft brewers is the highest number per capita in the country, according to the Brewers Association. About 10 years ago, there were slightly more than 20. In New Hampshire that number has gone from less than 40 in 2016 to more than 100 today, said Jenn “C.J.”Haines, executive director of the New Hampshire Brewers Association.

The Brewers Association reports

Craft brewers, industry experts say neighboring breweries help strengthen markets, tourismVALLEY NEWS / REPORT FOR AMERICA —ALEX DRIEHAUS Edwin Roycepicks upcans to befilled with MásVerde, anIPA beer madewith citra andchinook hops,at River Roost Brewery in White River Junction last month. SEE BEER S17

the economic impact of craft brewing on the New Hampshire economy was $457 million in 2021 and in Vermont it was pegged at $408 million.

In most industries, that sort of a dramatic growth would raise fears of market saturation where too many of the same types of business means everyone loses customers and some end up closing. But not in craft brewing, Haines said.

In New Hampshire, there can be “pockets”in the state where one brewery opening is followed by others and —instead of seeing each other as competition —they collaborate as a group, Haines said, adding that brewers along the Seacoast hold a Seacoast Beer Week. Many communities, including Claremont and Lebanon, hold brew festivals each year.

“You can draw more people to an area to get them to do more and give them a reason to stay where there

are other craft brewers,”Haines said. “People tend to want to go from one to the next.”

Brewers like to experiment and come up with new tastes, which mostly depend on the type of yeast used, so it is likely a few craft brewers in one area will offer a wide range of the more than 50 craft brew styles.

Dave Albright, manager of Bright Side Brewing, which is owned by his parents, in the terminal building in Lebanon Airport, said with brewers offering something a little different, they don’t worry about losing business as much to an establishment nearby.

“This is not a typical business model like having five pizza places on one block,”said Albright, who left an accounting job to open Bright Side about a year ago after making extensive renovations. “A lot of people will come to the state and will target an area with five or six breweries and go around to experience

different beers.”

Bright Side hired brewer Bill Waddell, who previously operated a very small craft brewer in Springfield, N.H., as it prepares to begin on site brewing. The business now brings in craft beer. It purchased the brewing equipment from the former Seven Barrel Brewery in West Lebanon and has some of the equipment on site. The rest has been fabricated off site, though Albright was not certain when on-site brewing would begin.

Albright, whose father has done home brewing and was inspired to open Bright Side. explained that there are three main tanks for brewing: hot liquor tank, a mash tun and a boil kettle. Depending on what is being brewed and the alcohol content, Albright said it can take between two and four weeks to brew a beer to completion. The business has 12 taps and he expects to use them all.

While there may always be room for another craft brewer, Babson and

Haines say like any business venture, it takes hours of hard work and commitment.

“I think jumping in and opening a brewery would be tough without ever having worked in one,”Babson said.

After several years at Magic Hat, Babson went to work at a brewer in Woodstock, N.H., where they were putting in a 30 barrel brew house. His on-job education for brewing is one approach, but brewers also can learn how to brew by taking courses.

Haines said many who begin as home brewers and have friends who compliment the beer, make the mistake of thinking they can get a brewery off the ground while keeping a full-time job to pay the bills.

“What happens a lot of time is there is not the consideration of how much time you need to dedicate,” Haines said. “When that happens it slows the process. There is licensing, wastewater treatment, water and

BEER FROM 17

municipalities you have to deal with.”

Additionally, getting the equipment purchased and set up, buying supplies and marketing all require a lot of time.

“It is definitely a full-time job,”Haines said.

When Babson got a job at Magic Hat, he learned to do all aspects of the job from cleaning and filling kegs to brewing and fermentation.

“Brewing beer seems glamorous but you are wet a lot of the time,”Babson said. “You spend a lot of time cleaning; a lot of time with chemicals. It is also mechanical with pumps and hoses and troubleshooting problems. Then there is packaging and distribution.”

Both the New Hampshire Brewers Association and its counterpart in Vermont serve as advocates and promoters of craft brewers. They also weigh in on legislation that will help brewers. Each association also has “beer trails”for tourists that indicate where craft beers can be sampled.

Albright said he has found tastes differ depending on the area. In Burlington, for example, the younger crowd he saw favored sours, which has a more tart taste.

“I think it is really trying to figure out what people want,”Albright said.

With craft beer sales up 8% in 2021, despite the pandemic, it seems there will always be room for another craft brewer in New Hampshire and Vermont.

Patrick O’Grady can be reached at pogclmt@ gmail.com.

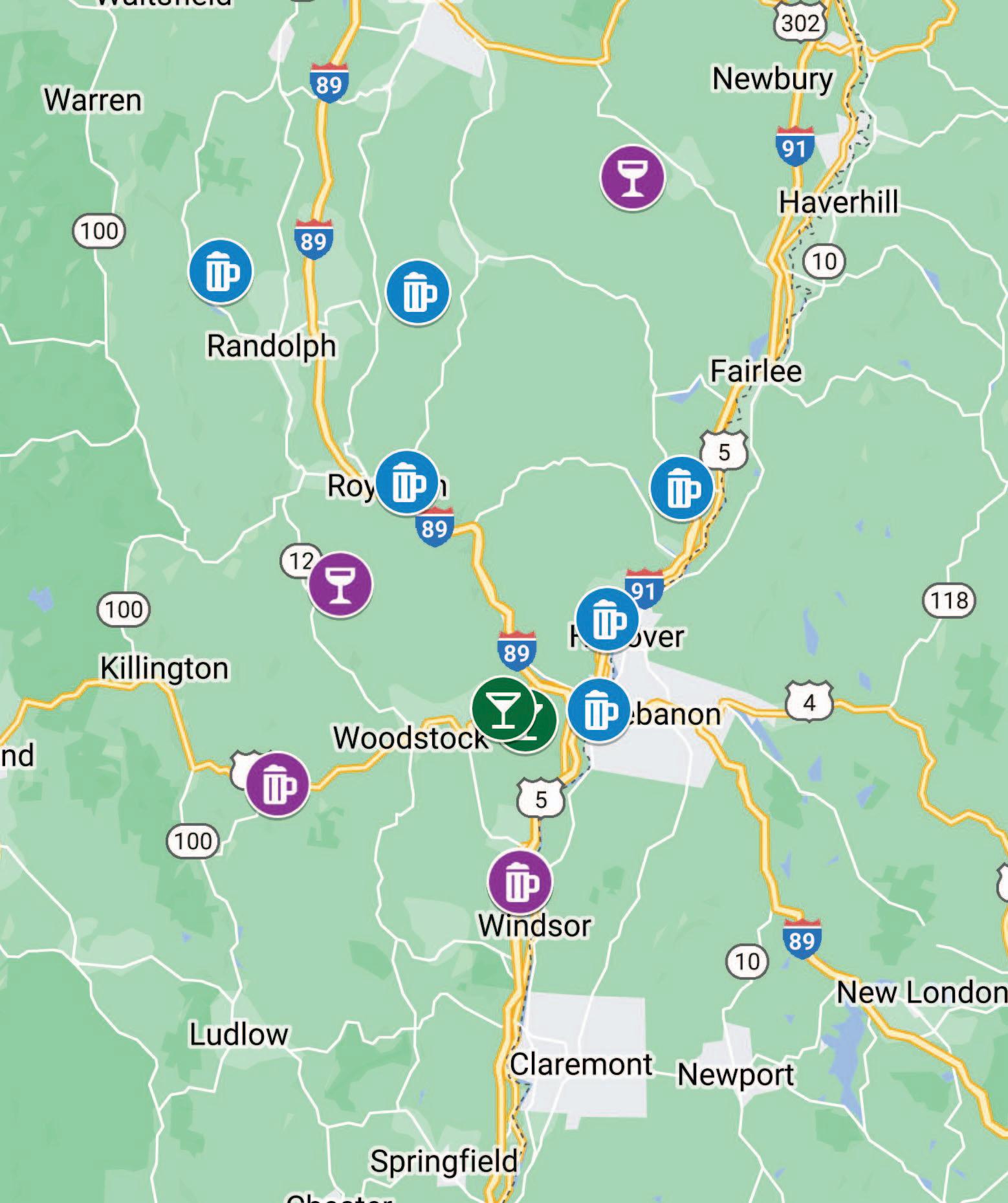

Both New Hampshire and Vermont have seen an explosion in the last few years of small breweries, wineries and distillers popping up. Besides crafting tasty new beverages, these businesses are having a big impact on both states’ economies and on the towns where they are located.

Although most of these businesses are small, typically with fewer than five employees, they are having big financial impact. According to the National Brewers Association, the craft brewing industry contributed $76.3 Billion to the U.S. economy in 2021 and more than 490,000 jobs across the country. In 2021, craft breweries contributed a whopping $456.5 million in New Hampshire and $407.6 million in Vermont.

In fact, Vermont ranked number one of all states in output per capita at $820.84. Currently, New Hampshire has 98 registered breweries and Vermont follows closely with 74 registered breweries.

However, beer is not the only choice if you enjoy locally crafted alcoholic drinks. The number of wineries and distilleries are growing in both states as well. The N.H. Winery Association lists 21 wineries and the Vermont Grape & Wine Council names 30 wineries in the state. Many use a variety of fruits to create wine, from growing grapes to using other fruits such as apples, pears or stone fr uits.

If patrons prefer a drink that’sa bit stronger or a mixed cocktail, they can try a New Hampshire or Vermont bourbon, gin or vodka from one of New Hampshire’s 10 distilleries or Vermont’s 20 registered distilleries.

And we haven’t begun to count meaderies or cideries.

Without a doubt, the numbers of these of businesses and their popularity show that New Englanders like their alcoholic beverages and even better if made locally. However these businesses are also credited with helping our towns and local economies. In fact, for many towns where a new brew pub or winery has opened, significant economic development has followed.

In an interview with BrewView, an online publication dedicated to craft alcohol, Vermont Commissioner of Economic Development Joan Goldstein explained the link. “In terms of tourism, it’s brilliant! People come to Vermont just to visit breweries and to taste amazing beer! Many breweries also occupy spaces that were otherwise vacant, which brings vibrancy in a village center or in a downtown. ... Local breweries and distilleries create jobs and help revitalize their local economy.”

As with any industry, making lo-

cal alcohol trickles into supporting many other related businesses. Many craft beer, wine and spirits makers start in their homes. Often their journey to selling their beverages begins at farmer’s markets. Sourcing their ingredients locally helps to support other local producers, including fruit growers for wine, for example.

When producers decide to take the leap to scaling up their operations, they need real estate and enough square footage to accommodate the large tanks or vats necessary to make several gallons at a time. This often leads to redevelopment of older commercial properties. Finding space large enough and at affordable rent has often seen these businesses locating in older buildings, usually in areas with cheaper rents and fixing the buildings up. For a municipality, it’s an opportunity to begin revitalizing an

Montview Vineyard

Brocklebank Craft Brewing Bent Hill Brewery

Fable Farm

Upper Pass Beer Company

Vermont Bike and Brew

W histlePig Whiskey Parlour

Long Trail Brewing Company

Jasper Murdock’s Alehouse River Roost Brewery

Vermont Spirits Distilling Co.

SILO Distillery

Harpoon Brewery Taproom

area that may have fallen into disrepair or to build on the vibe coming from the new business, attracting younger people, interesting new businesses and artists.

If you open to the public and serve alcohol, then you need food. This often results in collaborations with food producers or restaurants or food trucks. Sometimes a brewery serves their own food, such as L ebanon’s BrightSide Brewery or the Norwich Inn’s Jasper Murdock Alehouse. Others, such as Able Ebenezer Brewing located in an industrial park in Merrimack, N.H., have menus from local restaurants available for patrons to order food to be delivered there.

We all remember the television show “Cheers,”where as the theme song went “everybody knows your name.”These businesses often become our “third place,”a term first defined by sociologist Ray Oldenburg

in his book entitled “The Great Good Place,”where he defines the Third Place as a place where people spend their time aside from the first place (home) and second place (work). A social destination that attracts people to gather, to converse, to eat and to drink. These businesses contribute to a community’s vibrancy by becoming a place to gather and for social interaction. And in their travels to this destination, people often visit nearby businesses —buying food, a gift, running an errand, getting gas for the car —and spending money that supports numerous other local businesses.

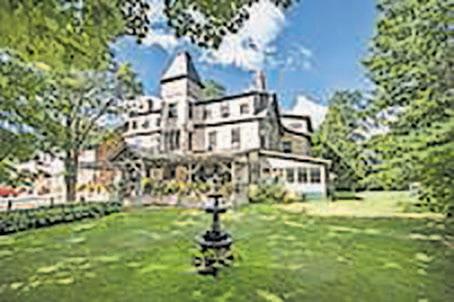

In some cases, the brewery, winery or distillery becomes its own event center, hosting events such as weddings, reunions and corporate gatherings. This in turn often leads to support for ancillary businesses, such as photographers, caterers, florists, musicians and event coordinators, among others.

SILO Distillery in Windsor is a

great example with its upstairs room that can be rented for bridal showers and other events.

Tourism is an important industry in both Vermont and New Hampshire. The outdoor economy of both states attracts visitors from all over. But what to do when the weather is not great? Our local breweries, wineries and distilleries are having an impact here as well by providing places to gather, tours to see how they make their products and, of course, for tastings.

Visit the state tourism websites of either Vermont or New Hampshire, and you find food and drink tours outlined. In the Upper Valley, we created our own “trail”of Upper Valley Adventures: Find it at tinyurl.com/ UpperValleyAdventures.

Whatever your preference in drink, making it a locally produced beer, wine, or liquor keeps the purchasing dollars circulating in the Upper Valley and supports many businesses, all in one sip. Cheers!

Deborah Hauser, director of strategic growthat FourSeasons Sotheby’sSouth Burlington, Vt., has been named chief operating officer of the real estate firm, which has locations in Fairlee,Hanover andNewLondon.

SKC Floral Design LLC,a florist and giftshop owned by Samantha Charles,has opened 34 Pleasant St.in Claremont. More information: skcfloraldesign.com.

Please submit business announcements viavnews.com/ Reader-Ser vices/Contribute/ Submit-a-Business-Announcement.For moreinformation, contactLiz Sauchelliat esauchelli@vnews.com or 603727-3221.

These businesses contribute to a community’s vibrancy by becoming a place to gather and for social interaction. And in their travels to this destination, people often visit nearby businesses —buying food, a gift, running an errand, getting gas for the car —and spending money that supports numerous other local businesses.A New York couple on vacation have lunch and a beer at Harpoon Brewery in Windsor in 2016. They wanted to try to avoid chain re staurants.