JUNE 2024

P. 14 Tying together past and present generations

P. 22 Iosepas’ story

P. 26 Stars above and islands below

P. 14 Tying together past and present generations

P. 22 Iosepas’ story

P. 26 Stars above and islands below

Scan to learn more about our team

NEWS CENTER: Box 1920 BYUH Laie, HI 96762

Editorial, photo submissions & distribution inquiry: kealakai@byuh.edu

To view additional articles, go to kealakai.byuh.edu

CONTACT:

Email: kealakai@byuh.edu

Phone: (808) 675-3694

Office: BYU–Hawaii Aloha Center 134

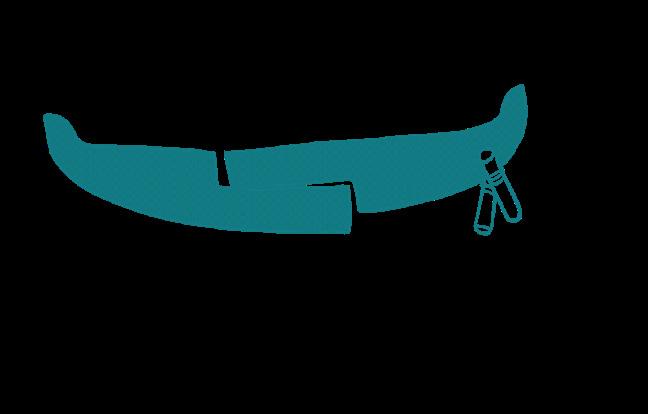

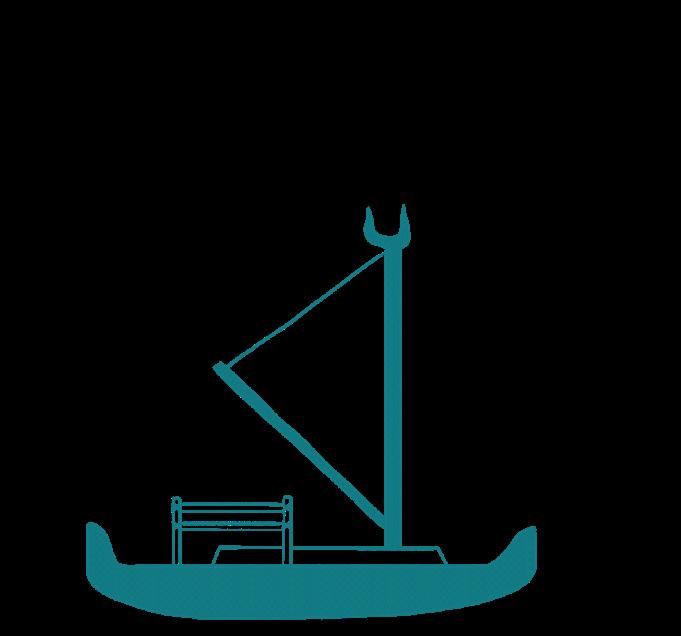

ON THE COVER: An above view of the Iosepa canoe. Photo courtesy the Polynesian Cultural Center. Graphics by Moevai Tefan.

BACK COVER: Iosepa’s first launch on Nov. 3, 2001 at Hukilau Beach in Laie. Photos by Mike Foley.

Make your own canoe insert created by Elinor Cash

The Ke Alaka‘i began publishing the same year the University, then called Church College of Hawaii, opened. It has continued printing for more than 65 years. The name means “the leader” in Hawaiian. What began as a monthly newsletter, evolved into a weekly newspaper, then a weekly magazine and is now a monthly news magazine with a website and a social media presence. Today, a staff of more than 25 students work to provide information for BYU–Hawaii’s campus ohana and Laie’s community.

© 2024 Ke Alaka‘i BYU–Hawaii All Rights Reserved

Ia ora na readers,

Growing up in Takaroa, an atoll of French Polynesia, the ocean has always been a big part of my life. My grandparents often shared stories of voyaging and how the warrior of my atoll, Moeava, went to war on his canoe named Murihenua. Those stories I thought were only possible in Disney movies. As I got older, they became more real and significant to me.

My first semester at BYU–Hawaii, I took an introduction class to Pacific Island Studies that made me realize the importance of canoes, va’a or wa’a respectively in Hawaiian and Tahitian. In class, we talked about Mau Piailug or Papa Mau, from Satawal, Micronesia. He was the last teacher of traditional voyaging. Papa Mau taught the team of Hokule’a, a Hawaiian double-hulled voyaging canoe, how to navigate the way their ancestors did. Learn more about him and his students on p. 26.

This issue of Ke Alaka‘i will take you on a journey through oceans, dreams and the past through photos and stories of voyaging the Iosepa canoe. My hope is these stories will help us realize the ocean does not separate the human family, but brings us together.

Learn the history of the Iosepa canoe and the significance of its name on p. 22. You might realize, like I did, that it takes a village to build a canoe and that past and present generations are all involved after reading on p. 14.

If you’ve ever wondered how to live on a canoe, learn more about daily tasks on p. 10. Each voyaging experience is different. Some can take an unexpected turn (p. 28) and others are like a fairytale (p.24).

Voyaging across the ocean requires experience and navigational skills that can be life lessons for all (p. 18,20). My biggest takeaway after creating this magazine is to respect and love the ocean because what it gives, it can also take away.

I hope what you read in here will inspire you to spread your wings and embark on many voyages. Stay safe and enjoy the ride.

Mauruuru, Ranitea Teihoarii Editor-in-chief

Crew members share details about their 2024 Iosepa launch and the importance of a crew acting as one

BY DARAVUTDY SI

The Iosepa sailed around Oahu in 29 days, and it was made possible by a united crew and community, said the canoe’s captain, Mark Ellis.

Ellis, the director of Voyaging Experience at the Polynesian Cultural Center, said the most important things for him to keep in mind as captain are his crew members and the canoe. “If it’s not safe for the crew or the canoe, we do not set sail,” he said. Weather is a key factor in determining whether or not to move, he said.

Someone always needs to be on watch while sailing, explained Ellis. He had a watch captain help him do this to make sure they sailed in the right direction, he said. There will also be a cook, a medical person and a person in charge of media, he added.

Mark Lee, a community member from Hauula, is the crew member in charge of media. He said he was given the task because

“It is very important for you to be humble and have trust and faith in your crew and your captain.”

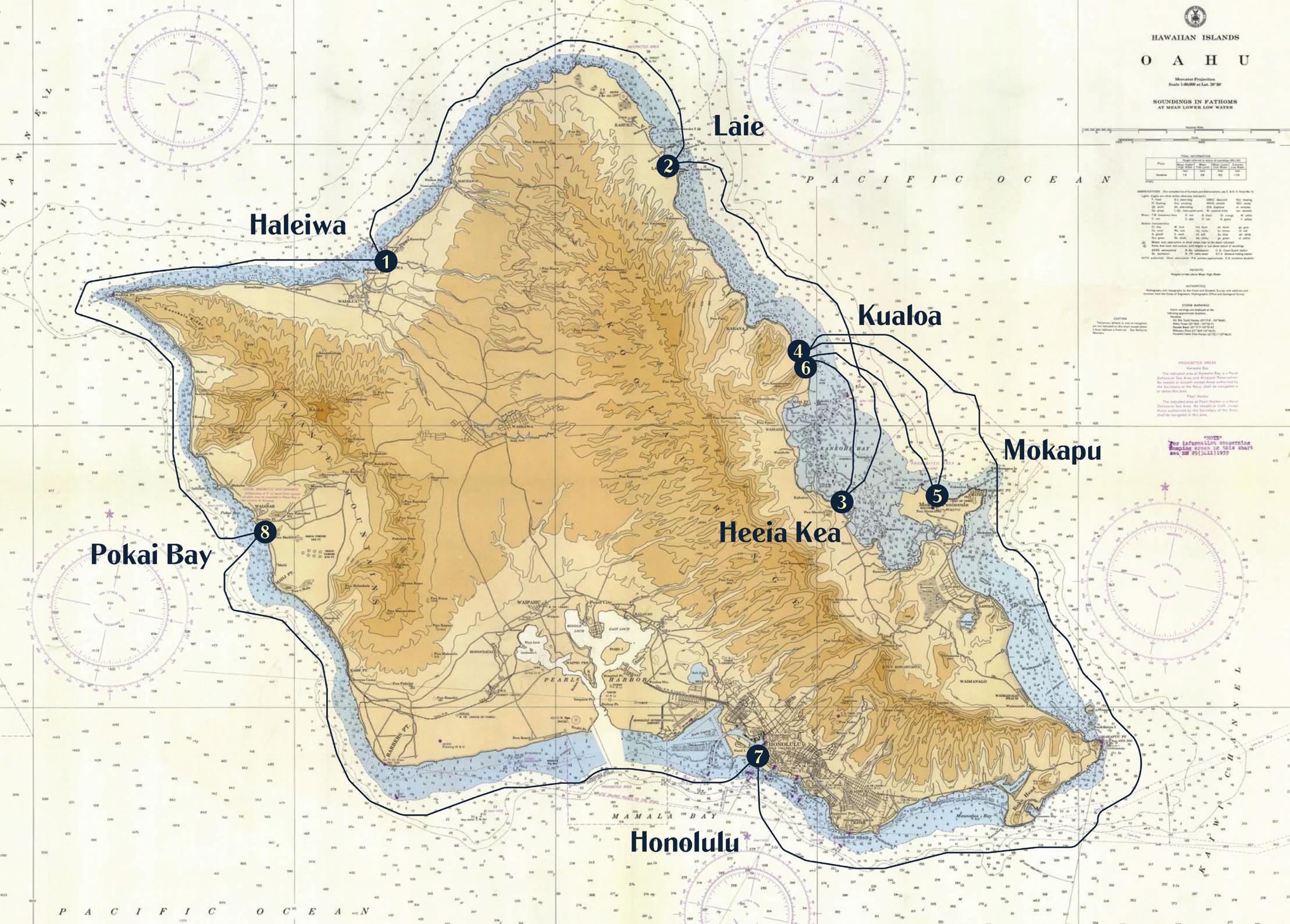

The journey around Oahu

Ellis and a crew of 12-to-13 people started their journey in Haleiwa harbor on May 30. The first day was a shakedown sail, said Ellis, to make sure everything was working perfectly. On June 1, they sailed from Haleiwa to Hukilau and then to He’eia Kea where they camped for two days. Ellis said they camped so as not to sail on Sunday.

On June 3, they sailed to Kualoa Beach for the Wa’a Traditional Voyaging Festival where there were other canoes from different parts of Polynesia. Ellis said of all the boats there, Iosepa was the only canoe made entirely out of wood.

The next morning, the crew engaged in recreational activities with the community. On June 10, they had an education day, said Ellis, because they “are trying to integrate voyaging and wayfinding into classrooms for students to learn more about the history of the canoe.” Ellis said they will be monitoring the weather for a few days before they continue to sail to the south side of Oahu.

“Our next stop will be at the Marine Education Training Center on the south-side of Oahu,” said Ellis. He added they will stay there for a couple of days before heading to Pokai Bay

of his experience as a professional photographer and doing underwa

-

ter photography. He will be documenting the voyage around Oahu, he said.

Another crew member, Jerusha Magalei from BYU-Hawaii’s Faculty of Education & Social Work, said the Iosepa is very important to her family because her father, “Uncle Bill” Wallace III, is the canoe’s founder. She said she will only go on one short leg of the entire voyage and will spend the rest of her time providing support from land because the Iosepa will be sailing close to shore the whole time.

Magalei said the trickiest part about sailing is finding a crew that works well together. “If your relationship with the crew is not good, you will have a hard time getting anything done,” she said. “It is very important for you to be humble, and you have trust and faith in your crew and your captain,” she explained.

“I am hoping this launch will bring the community together,” said Lee. He expressed his desire to help the people of the island become stronger. As part of this effort, there have been community work days, he explained, where people helped prepare the Iosepa and learned about its history.

in Waianae on the 19 and stay there for a few more days. “We will then end our trip back at Haleiwa on the 24 and get the canoe ready to pull out,” he said. •

Iosepa was the only canoe made entirely out of wood.

The captain of Iosepa answers questions about how sailors live on the canoe

BY MYCO MARCAIDA

From early-morning crew meetings to going into an anchor watch, a sailor’s life starts at 5 a.m., said Mark Ellis, director of Voyaging Experience at the Polynesian Cultural Center. He explained how day-to-day living works while on board a Hawaiian canoe.

They use a bucket to pull water from the ocean and then lather up with environmentally friendly soap.

The sailors are split into two groups. One group works while the other group rests until they switch. The working group re-ties and fixes lines and opens and closes the sails as needed. The resting group plays music and games or tells stories.

There is an area on the back of the canoe with a seat with a hole in it where sailors can do what they need to into the ocean. The seat is covered by fabric flaps on all sides for privacy.

Cooking on the canoe is similar to cooking while camping. They bring a portable stove and plan a menu so nobody gets bored of the food.

Generally, there is a crew of 12 sailors on the boat at any given time.

Anchor watch is when crew members are posted on lookout duty on a rotation throughout the night, says the Grenada Bluewater Sailing website. Community members volunteered to be part of the Iosepa’s anchor watch when the canoe was anchored at a port, completing sixhour shifts. They would jot down information about the canoe for the next batch of sailors, said Ellis. This is vital for the safety of the canoe, Ellis explained, in case of changes in weather, tide or a moving anchor. •

The Laie community gathered at Hukilau Beach to watch the Iosepa sail past

BY RANITEA TEIHOARII

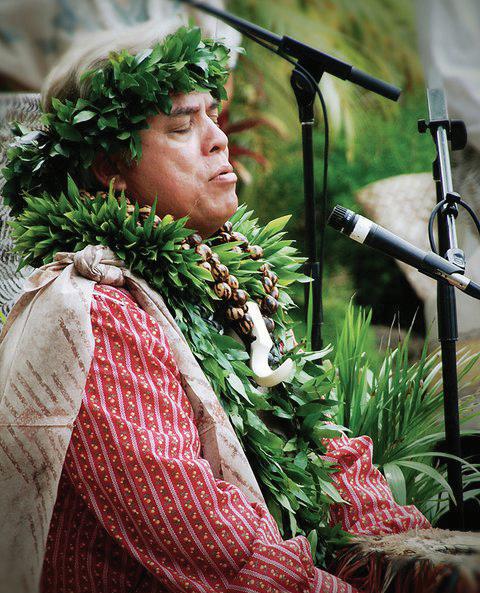

As the Iosepa passed Hukilau Beach, conch shells and Marquesan wooden trumpets were blown. Kela Miller, a community member with her own halau, created a pono, or peaceful, environment by directing the crowd’s attention to the Iosepa.

Halau Hula O Kekela led the crowd in songs and chants in honor of the boat’s passage on

June 1. Jerusha Magalei, an assistant professor in BYU-Hawaii’s Faculty of Education & Social Work and Iosepa canoe founder Bill Wallace’s daughter, offered a chant in Maori.

Holding hands in a circle, the crowd gave a prayer of thanks and a blessing on the Iosepa crew members to ensure their safety. •

Hiki Mai E Nā Pua’s deeper meanings continually influences generations throughout BYUH and the community

BY

Pioneer ancestors calling out to their descendants to come forward and listen to the voice of the Good Shepherd is what Hiki Mai E Nā Pua is about. The “mele,” or chant, was written by Kumu Hula Cy Bridges as a hula ka’i or entrance song for the Pioneers in the Pacific Celebration on Oct.7-11, 1997.

The celebration commemorated the 150 anniversary since pioneers arrived in Utah. It recognized the growth of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints with global members becoming greater than in North America.

It also focused on local pioneers whose contributions are significant in establishing the Church in their respective areas, such as the Pacific.

The chant was then incorporated into the Hawaiian studies program by the late William Kauaiwiulaokalani Wallace III, commonly known as “Uncle Bill,” and former director of the Jonathan Napela Center for Hawaiian Language and Cultural Studies at BYU-Hawaii. Since then, it is used during meetings, protocols and welcome ceremonies for visitors.

An empowering influence

“It is one of those chants that BYUH, as a whole, has embraced because the Hawaiian studies program embraced it in the beginning,” said Jerusha Magalei, Wallace’s daughter and

assistant professor in the Faculty of Education & Social Work.

Bridges and Wallace’s families “have intertwined for generations,” said Magalei. Bridges and Wallace were cousins, she explained, and they had a special connection that seemed like they were brothers.

Wallace had a desire to honor Bridges creation as well as cultivate an understanding of the kaona or deeper meanings of the chant for students, she said. This led Wallace to adapt Hiki Mai E Nā Pua for the Hawaiian studies program.

Alohalani Housman, dean and associate professor of the Faculty of Culture, Language, & Performing Arts at Jonathan Napela Center for Hawaiian & Pacific Studies, said there are usually kaona people find when they deeply understand mele.

“Everything is symbolic [about the chant],” said Housman. She said the chant brings an important message that connects descendants to their ancestors and serves as a reminder to follow the voice of the Lord.

“It serves as an encouragement to all of us to come forward. We can’t just stay where we are at. We need to continue to learn, progress, move forward and keep going all the time,” said Housman.

She said Hiki Mai E Nā Pua has become a foundation for the Hawaiian studies program because of its beautiful meaning. She said it is the first chant the Hawaiian studies majors learn when they come. She said it has also been incorporated in the program’s special kīhei ceremony, where the kumu, or teachers, tie the kīhei, or garment, to the student as a symbol of their mastery and knowledge of the Hawaiian language.

Magalei said the reach of the chant has extended past the Hawaiian studies program. People at “the Lahanuli Gardens also sing the chant as part of their protocol when students come or people from outside visit. The Social Work department also uses it, and some other classes use it in their own spaces,” she said. “I use it for my classes when I teach,” she added.

She shared as students sing the chant, her father Bill Wallace, hoped they would understand who they are. “They are these special and important adornments, leis or flowers of their ancestors, and what they do will reflect where they come from,” she said. “They are also representatives of the Savior,” she added.

Housman shared a meaningful experience she had when she was invited to be a speaker at a youth conference. She said the youth went to see a loi, which is a kalo or taro field, run by a BYUH graduate. To show respect to the place, she said they chanted the Hiki Mai E Nā Pua.

Witnessing BYUH graduates passing on the chant with the youth, she said, led her to realized Hiki Mai E Nā Pua’s empowering influence is not only felt at BYUH but also continues throughout the community.

When preparing for the launching of Iosepa, together with the hymn, “Pule Maluhia” which is “Secret Prayer, “Housman said every training and meeting opened and closed with the chant.

“It is a continuation of our beliefs, values, love and respect for Uncle Cy and Uncle Bill. It is always special to do it in their remembrance,” said Housman. She said it is also a way to show the relationship, respect and appreciation for those who have contributed so much to us. •

“[Keep] faith, go forward on a mission, share and exemplify His word and message, be a great leader and touch the lives of others with the truth and light of the Restored Gospel.”

- Kumu Hula Cy Bridges

Na pua in the first verse refers to the students who participated in the [celebration]. Most were BYUH students, however there were quite a number of others from the community. It could represent all of our youth.

“In the calm” identifies those who are members of the Church.

Hiki mai e nā pua i ka laʻi ē

Come forth oh children in the calm

Ke piʻ

mauna

And climb the high mountain

Haʻa mai nā kama me ka makua

Dance forward with your Father

La’ie was a place of refuge just as our families, church, communities, wards, stakes, schools or anything connected with the church should be in our lives. A place of refuge, with an element of healing and enlightenment where individuals can make positive changes in their lives. That would be “the calm” compared to the rest of the world.

Strive for the summit. Keep your standards high.

Ha’a is an archaic term for dance with bent knees. However, it also means to be humble, meek and unpretentious, which could be interpreted as having a broken heart and contrite spirit.

He wehi pūlama aʻo ke kupuna

A cherished adornment of the ancestors

E kaʻi mai ana, e kaʻi mai ana

Come forward, proceed forward

E hahai i ka leo o ka Haku ē

Follow the voice/word of the Lord

The cherish adornment refers to the adornment of the restored gospel of Jesus Christ. This was embraced by ancestors who were the pioneers of the church in the Isles of the Sea.

Ka’i also means to lead, direct, to lift up and another form of ka’i is huaka’i, a procession, journey or mission. As their mission in life continues, they would be a strong “ala-ka’i” or leaders.

Together, these lines mean to know Him and understand His teachings and His words.

Cy Bridge’s translation of the chant.

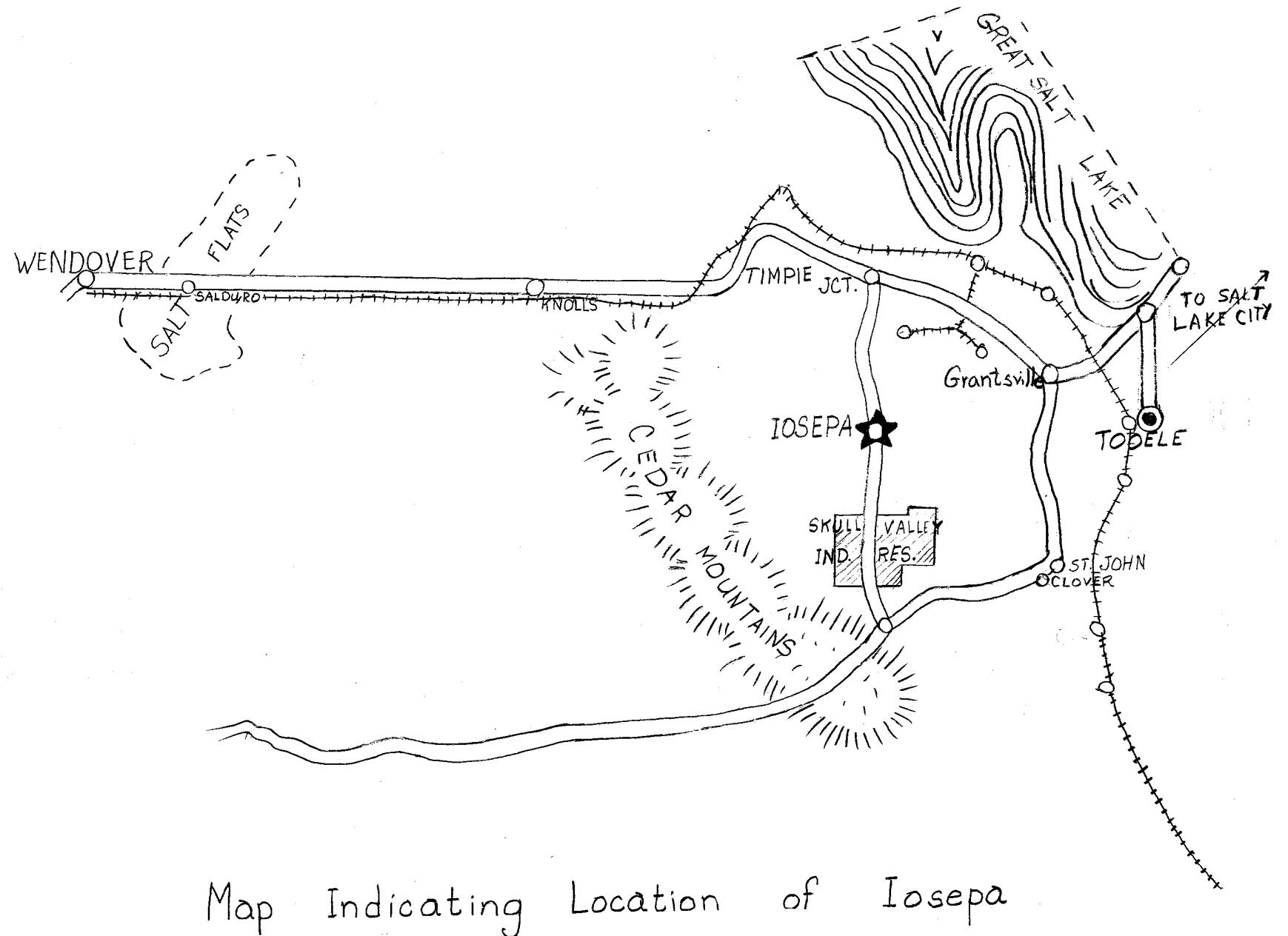

November 1, 2001

President M. Russell Ballard of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles dedicated and launched the Iosepa.

October 2001

Uncle Bill Wallace named the canoe Iosepa, following instructions he received in a dream of his Hawaiian grandfather.

March 2001

Kawika Eskaran, the master carver and captain for the upcoming voyage, together with Tuione Pulotu from Tonga, carver for the Tongan royal family, started to work on the logs.

February 7, 2001

Seven massive logs arrive at a vacant site managed by Hawaii Reserves, Inc. to be carved into a canoe.

Mid-1990s

The BYUH Hawaiian Studies Department, led by Uncle Bill Wallace, launched a project to build a canoe in the year.

Mid-1970s

The movement to preserve the Hawaiian legacy by reconstructing ancient canoes started with the building of Hokulea.

June 28, 2008

The Iosepa was showcased to the public at the PCC.

11 crew members, comprised of students from various countries, working every day to prepare the canoe for a journey.

15, 2016

The Iosepa launched from Hukilau Beach, but was short-lived as failed logistical plans prevented further sailing.

e n tday

May 30, 2024

Iosepa sets sail as part of the Festival of Pacific Arts & Culture.

The Festival of Pacific Arts & Culture is the world’s largest celebration of indigenous Pacific Islanders since 1972.

The Iosepa has been integrated into the Laie community over the years by teaching people how to sail

BY EMELIA MIKE

The Iosepa canoe last sailed eight years ago, says the Polynesian Cultural Center’s Instagram page. This year, in 2024, the canoe is voyaging again for the Festival of Pacific Arts & Culture. “The festival happens every four years, so they choose a different place to host it, whether Polynesia, Melanesia, or Micronesia,” said Mark Ellis, the director of Voyaging Experiences at PCC. “Hawaii is honored to host the festival from June 10 to the 15 this year,” he said. The eight years of not sailing was due to high maintenance cost, the COVID-19 pandemic and inconsistent weather, said Robecca Salleh, a sophomore from Malaysia majoring in biology, who works as a

demo guide at the Iosepa Section of the PCC. The canoe festival was the motivation that got the crew to get the boat back in operation, she said.

Ellis said the BYU-Hawaii canoe first launched in 2001 as a floating classroom to teach the students navigation through voyaging. The Iosepa has been a part of the community since it was first launched, said Roy Kaipo Manoa, the Hawaiian Village cultural expert & presenter at PCC. “I remember [the Iosepa] being out in the field where McDonald’s is now,” he said.

According to Manoa, William Wallace, also known as Uncle Bill, was the director of the BYUH Jonathan Napela Center for Hawaiian Language and Culture Studies. He used the Iosepa to teach students to respect the land and the ocean while using these resources. Manoa added, “As an islander, the sea has always been our refrigerator. If we needed something to eat, we would go to the sea together, and in return, we would pay respect by taking care of the ocean.”

This year the community came together and prepared the Iosepa for its journey, ensuring it is seaworthy for the festival, said Ellis. “We put in a lot of work, like repairing the inside and out of the canoe and varnishing it,” Ellis said. The sailing crew consists of BYUH students, faculty, PCC employees and community members. Training sessions were held twice a week to ensure competency among the crew, he explained.

Salleh said the canoe and those working on it have taught her no matter where people are from, their ancestors were intelligent people and the traditional knowledge that was passed down from generation to generation must be cherished.

Salleh shared her sailing experience saying, “I had the chance to present our beloved Iosepa at the Canoe Festival 2024 in Kualoa, and we chanted the Hiki Mai before we sailed it to the ocean.”

Salleh expressed gratitude for the knowledge she gained and for being able to teach others about sailing skills, such as navigating by the stars, learning sailing knots, and making ropes from natural materials. •

almost a decade of the canoe’s inactivity

BY KARL ALDRE MARQUEZ

Growing up, he has always respected and loved voyaging, said Mark Ellis from Nu’uanu, Hawaii, and the director of Voyaging Experiences at the Polynesian Cultural Center. He said the opportunity to sail the Iosepa is a once-in-a lifetime opportunity to represent his culture and be entrusted as the captain.

Ellis said his fascination with the ocean began during his childhood in Hawaii. He said growing up in a Hawaiian community, the sea is deeply revered as part of their culture and everyday lifestyle. When Ellis was 7 years old, he said he was fascinated with the Hōkūleʻ a, a double-hulled Hawaiian canoe. He said his lifelong intrigue about the canoe eventually aligned perfectly with his career aspirations.

“Upon seeing the vessel, I told my parents that I wanted to sail on it. Little did I know that it would be something that would happen in the future,” he said.

Besides his fascination with the Hōkūleʻ a, he said he was intrigued by his ancestors voyaging experiences. Getting a glimpse of what his ancestors did led to his curiosity about how his ancestors managed to voyage around the world without technology and modern tools.

As time passed, Ellis said education was his parents’ priority. He completed his undergraduate degree in organizational development and communications in 1994. Unsure of his path, he said he served a mission then became a flight attendant. Ellis said he went to graduate school at Utah State University, where he

studied instructional technology and design. “After graduate school, I received enormous offers to work at consulting firms in the tech industry and education. I entered a career, but my longing for the ocean and voyaging remained,” he said.

As his career progressed, he said his longing to voyage on the Hōkūleʻa slowly aligned with where he went.

For the past 10 years, he has been able to transfer to jobs that helped him feel close to his community. He became a voyaging educator and taught curriculum at Kamehameha School, he said. As part of the Moananuiakea voyage crew, Ellis said he also worked as a project manager for voyaging engagement, helping students and the community for Hawaiian voyages before becoming the director of Voyaging Experiences at PCC. “I am grateful for the experiences I had that led me back to voyaging,” he said.

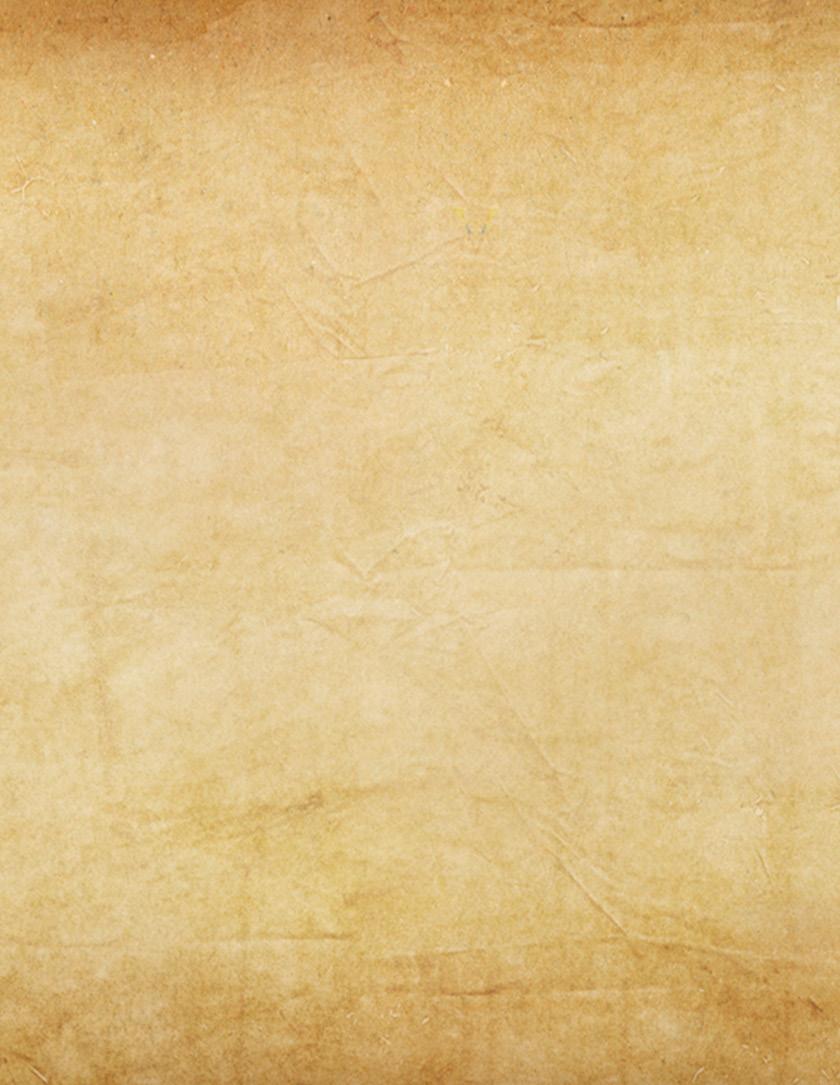

According to the Polynesian Voyaging Society’s website, Ellis first sailed on Wa’a Kaulua in 2007 and has been on several voyages since.

Ellis said he has sailed from Yakutat to Juneau, Ketchikan, Tacoma to San Francisco, and San Francisco to Ventura. He also sailed from Samoa to Aotearoa, Florida to Virginia, New York to Virginia and around the Galápagos Islands, he added.

The preparations for the Iosepa’s voyage were extensive, said Ellis. Since the canoe was first launched in 2001, he said it has undergone upgrades and repairs whenever it is set to sail. For this year’s voyage, he said the crew epoxied the whole canoe and made several upgrades in its body, ensuring the canoe was seaworthy and safe for crew members to sail.

Kalāhikiola Enos Haverly, a freshman majoring in political science from Hauula, said Ellis trained him to be part of the crew for the Iosepa voyage. Haverly said he had no sailing experience but was willing to learn and be

trained for the journey. The sail of the Iosepa was monumental for him because he had witnessed its inactivity for years, and seeing it sail again struck his interest in joining and being part of the crew. “Training for the voyage began in early January 2024, with sessions held twice a week for five months,” he said.

“I entered a career, but my longing for the ocean and voyaging remained.”

During his training, Haverly said he was reminded of the beauty of his culture. Being part of what their ancestors have done is very special for him, he added. “Growing up in Hawaii, I was exposed to Hawaiian culture. I spoke in Hawaiian, learned to read and write in Hawaiian before English and was taught to practice and love the culture including being on the water,” he said.

Throughout the training process, Haverly said he learned essential skills like knot-tying, assisting in basic canoe repairs, and navigation using natural elements such as the star compass, wave patterns, bird flight directions and wind directions. Under Ellis’s mentorship, Haverly said he learned to appreciate the ocean even more. Part of their training was spending as much time as possible in the sea to make the voyage comfortable.•

The Iosepa was named after several religious figures named Joseph

BY ANDREW QUIZANA & ABIGAIL HARPER

In the ancient annals of maritime history, where the whispers of the wind mingle with the crash of the waves, there exist stories of Polynesian canoes. The story of the Iosepa canoe is a testament the legacy of these vessels has endured with the seafaring culture of the people.

The story of these boats begins with the Polynesian migrations. Guided by the stars, constellations and swells, navigators traversed vast expanses of the Pacific Ocean, settling new lands and shaped the cultural landscape of the Oceanian region. At the heart of these voyages were the canoes – Polynesian vessels crafted with care from the resources of the islands. Made from towering trees and adorned with intricate carvings, these canoes were more than just modes of transportation; they were floating works of art, embodying the spirit and soul of the Polynesian people, said Herb Kawainui Kāne, co-founder of the Polynesian Voyaging Society.

One of the most remarkable chapters in the history of these canoes unfolded during the 19th century when the Pacific Islands were colonized. As indigenous cultures faced displacement and assimilation, the tradition of canoe building became more than just a practical skill – it became a symbol of resistance and cultural pride. “In the face of adversity, Polynesians continued to work on

their craft, passing down their knowledge and expertise from generation to generation, ensuring the flame of Iosepa Canoes would never be extinguished,” said Bill Wallace III, the first director of the BYUH Hawaiian Studies program and founder of the Iosepa.

The Iosepa, the Hawaiian word for Joseph, shares its name with Joseph F. Smith because of his connections to Laie and the Polynesian Utah settlement of the same name, says BYUH’s website. Iosepa also shares the name with other scriptural figures and people of significance to our faith, writes the website.

President M. Russell Ballard, the greatgrandson of Joseph F. Smith, dedicated and launched the Iosepa on Nov. 1, 2001.

When he was 15 years old, Joseph F. Smith was called on a mission to the ‘Sandwich Islands,’ the name used for Hawaii at the time, writes Eric Marlowe an associate professor in the Faculty of Religious Education.

Ten years before his mission call, Smith’s Father, Hyrum Smith, and uncle, Joseph Smith, were murdered by a mob at Carthage Jail. Two years before his call his mother died as well, leaving Smith an angry orphaned teenager. He later described his teenage years as being “a comet or a fiery meteor, without... balance or guide.” He wrote the mission to Hawaii “restored my equilibrium and fixed the laws...which have governed my subsequent life.”

On his mission, a woman named Naoheakamalu Manuhii nursed Smith back to health from a severe illness. She and her husband both received the gospel from the missionaries and, years later, Smith promised her she would live to see the temple built, says Marlowe.

More than 60 years later, Manuhii heard he was returning to visit the islands. She waited for days on the steps of the Honolulu mission house. She had gone blind, but when they arrived, she was waiting on the Honolulu pier and called out “Iosepa.” He ran and hugged her, saying “Mama, Mama, my dear old Mama.” By that time, he was prophet of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Marlowe wrote she brought Smith the best gift she could afford: A few choice bananas.

Smith passed away before the Laie temple was completed, but Manuhii was one of the first to attend. She was in her 90s and was carried through to receive her endowment and sealing to her husband. While in the temple, she heard Smith’s voice say, “Aloha,” when a dove flew through an open window. She passed away a week later and a statue of her resides next to the temple in her honor, says Marlowe.

A different kind of voyage

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, a Polynesian settlement was established in the distant land of Utah. In his thesis presented to the Department of History in Hawaii, Dennis Atkins said this colony was established by Hawaiian converts to The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints who faced discrimination and isolation in the main Utah settlements. Atkins added the colony was named Iosepa in honor of Joseph F. Smith and church leaders encouraged them to establish a community where they could live their customs, culture and religion without facing the prejudice they encountered in the other parts of Utah. “This community became a symbol of hope and resilience for Polynesian immigrants seeking for a better life. Despite being thousands of miles away from the ocean, the settlers of Iosepa remained deeply connected to their maritime heritage and culture, through crafting canoes from local materials,” he added.

According to his thesis, entertainment also became a significant aspect of their lives. Hawaiians performed traditional and songs

and dances, becoming popular entertainers in surrounding communities. Despite enjoying a generally happy and healthy community life, Iosepa faced challenges due to its isolation, lack of early telephone and mail services, and occasional illnesses including leprosy. A store was eventually established, easing access to necessities.

By 1917, twenty-eight years after its founding, the experiment of Iosepa came to an end, with most Hawaiians returning to the islands. The town’s lands, cattle, and improvements were sold, and its buildings were dismantled or repurposed.

“As we reflect on the epic journey of the Iosepa Canoe, we are reminded of the profound impact that these vessels have had on the course of human history,” said Mark Ellis, director for Voyaging Experiences. He said the canoes are more than just boats. They are symbols of courage, perseverance and the unbreakable spirit of the Polynesian people.

According to the Polynesian Cultural Center website, the legacy of the Iosepa canoe continued to grow, transcending geographical borders and cultural barriers. The canoe tells a story of exploration, resilience, love, and the enduring bond between humanity and the sea, says the website.

According to the Polynesian Voyaging Society website, canoes are made to perpetuate the art and science of traditional Polynesian voyaging and the spirit of exploration through experiential programs. They added these programs will inspire students around the world and their communities to respect and care for themselves and their natural and cultural environments. •

“ They are more than just boats. They are symbols of courage, perseverance, and the unbreakable spirit of the Polynesian people.”

Fa’afaite, built in 2009, sailed from Tahiti to meet the other Pacific canoes at the 2024 Festival of the Pacific in Hawaii

BY RANITEA TEIHOARII

Is the name of the Tahitian boat that was part of the same festival as the Iosepa. The name means, “The reconciliation of the Tahitian people across the islands of Polynesia, the link between all these islands and the reconnection to the Tahitian roots.”

Fa’afaite at a glance

Fa’afaite was built in Auckland, Aotearoa, in 2009 by Salthouse Boatbuilders. It was one of seven canoes funded by Dieter Paulmann, founder of Okeanos Foundation for the Sea, a company that works to preserve the ocean. They call the 7 boats Vaka Moana’s, meaning canoes of the ocean.

Crew member capacity: 16 people

Length: 22 meters - 72.2 feet

Width: 6.4 meters - 21 feet

Departed from Tahiti: May 12th, 2024

Arrived in Hawaii, O’ahu: May 28th, 2024

Equipment on the va’a

8 bunks on each hull

Storage for sails, ropes and other equipment in the front of the hulls

A private toilet

A small kitchen and an office for the navigators and captain

2 safety canoes

1 safety paddle or hoe

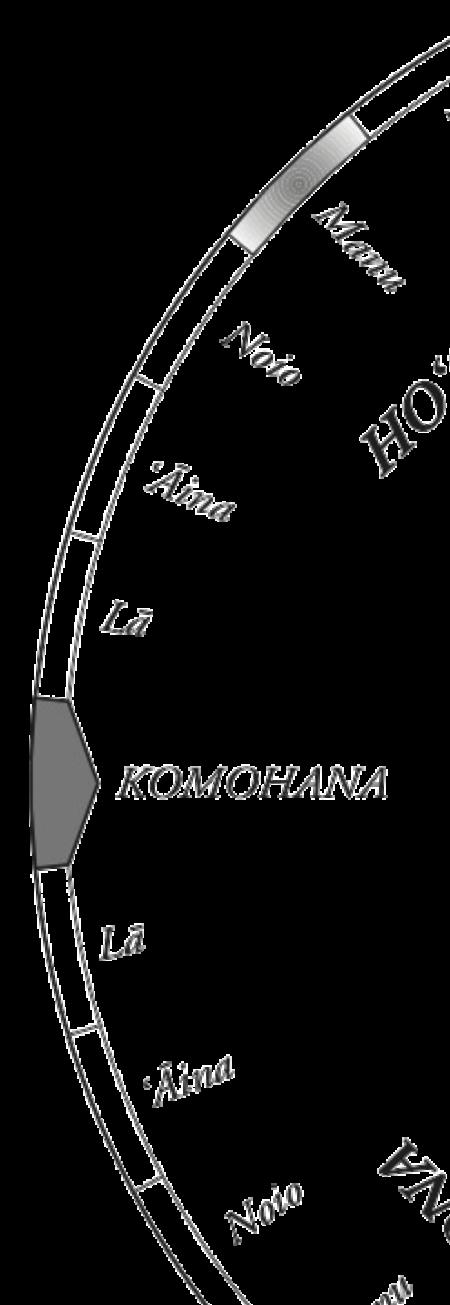

A star compass

Eliane Garganta, a crew member of Fa’afaite, said the crew had 10 women and 6 men on the voyage from Tahiti to Hawaii. She added the shape of the canoe was inspired by a Paumotu double-hulled canoe in Fakarava, Tuamotu Islands. “While the back of the canoe is elevated, the ‘īato or the front is flat to break through the waves,” said Garganta.

The journey to Hawaii was faster than they expected, she said, calling it a “blessed voyage.” As they crossed the equator, she said,

the clouds dissipated, showing a starry night sky and a calm sea. “ We took it as a sign of an opening door,” said Garganta.

Before the crossing to Maui, she said, “We saw a false orca, he was about four meters. And again, [for us] it was a sign of another door opening.” After the orca departed, the sea became agitated and the captain noticed different clouds, indicating nearby land, she said.

“As we got closer to what we thought was a light from another canoe, we realized it

was land,” said Garganta. Fa’afaite and its crew arrived at one of the Hilo– Big Island beaches at 3 a.m., four days earlier than expected. •

Fa’afaite, crew members and a star compass. Graphics by Yichi Lu.

Photos by Camille Jovenes

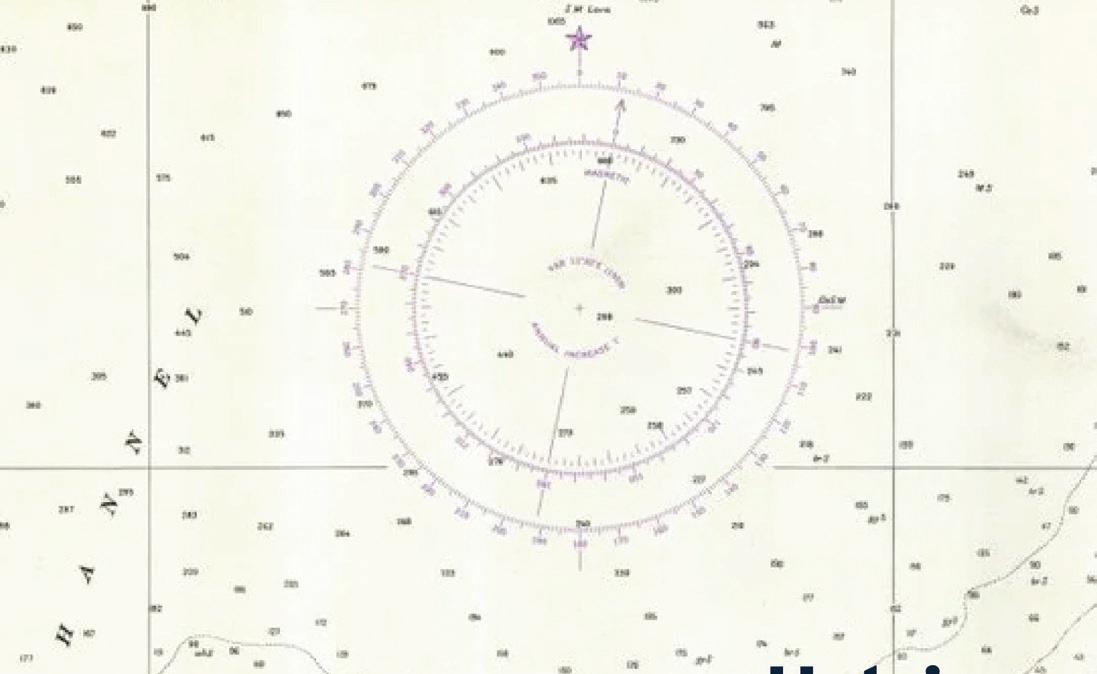

The sun, stars, waves and birds are used in Hawaiian navigation, says Iosepa’s captain, Mark Ellis

The ancient art of wayfinding was retaught to Hawaiians by a man from Micronesia who had faith in his ancestors’ knowledge. The lessons learned in navigation apply to our lives, as well as to sailing, said Mark Ellis, the director of Voyaging Experiences at the Polynesian Cultural Center and the captain of Iosepa.

Thousands of observations are made on the deck of a canoe every day, such as where the sun is setting or where the wind is heading, said Ellis. Those observations help make hundreds of choices, such as how to steer the canoe and whether to put up a bigger or smaller sail. “At sunrise and sunset, during the transition time of dawn and dusk, we answer two questions: Where are we in the phase of the earth? And what direction are we going?” he continued.

The only way to know where you are is to know where you sailed from, said Nainoa Thompson, the CEO of the Polynesian Voyaging Society. Ellis said all the concepts used to sail can be applied to life.

BY CJ SHINIHAH NOTARTE

Preserving traditional wayfinding

Ellis said he learned how to navigate from several people, but the Hawaiians first learned how to navigate from a man named Pius “Mau” Piailug, who was from Satawal, Micronesia. The first modern canoe was called Hokule’a, he said. “The Hawaiians built the canoe to prove the fact that our islands and our ancestors purposely navigated throughout Polynesia and the Pacific,” said Ellis.

The Hawaiians had a canoe but no navigator, he said. They searched the Pacific for a teacher and finally found Piailug, who agreed to teach them, said Ellis. “The Hawaiians asked Mau if he had been to Tahiti before, to which he answered, ‘No, but I trust in the teachings of my ancestors. I am only courageous because I have faith in the teachings of my ancestors. The concepts and my faith in my ancestors are what’s going to take us there,’” said Ellis.

Ellis said Piailug took the canoe and taught the crew members wayfinding using a Micronesian star compass that separates the horizon into 32 points. Ellis said navigators

stay awake up to 20 hours to monitor and observe their surroundings. He said a Hawaiian named Nainoa Thompson, who Piailug taught, gathered his knowledge and created the Hawaiian star compass, making it easier to understand. “We have this compass, and it teaches us how to put things in order,” said Ellis.

On the Polynesian Voyaging Society website, Thompson said, “You cannot look up at the stars and tell where you are… It all has to be done in your head.” He said the principle is easy, but it is difficult to do.

The North Star, or Hokupa’a in Hawaiian, will always be in the North, said Ellis. If the canoe is heading towards Hokupa’a, you are going North, he explained. If it is behind you, you’re heading South. If you look at Hokupa’a and stick out your right hand, to the right of your hand will always be East, and the left will always be West, he said. “This is a simplified concept of how we use the stars [to navigate],” said Ellis.

In the daytime they navigate by the sun, Ellis said. He said, “The sun rises typically in the East and sets in the West.” If you want to go North, the sun should rise on your right and set on your left, he explained.

When the clouds cover the sky or the sun is too high, Ellis said they use the wind and waves to navigate. He said the wind creates swells in the ocean. “If the sun is coming up and we still want to head North, we notice the wind coming from the East.” The wind causes the waves to pick up and drop the canoe, creating a rhythm, Ellis explained. He said, “When I was heading down to Galapagos Island from Panama on Hokulea, there were some big swells that were coming from the South. We were able to identify and hold onto that swell to tell our direction.” Thompson said Piailug told him, “If you can read the ocean, you will never be lost.”

Ellis said when they are getting closer to the islands, they look for land-based seabirds. He explained, “These birds live on land and fly out to the sea to eat, but every night, they return home.” He said if they spot this kind of bird and the sun is setting, it means the birds are going home. “We follow that bird to the

“I trust in the teachings of my ancestors. I am only courageous because I have faith in the teachings of my ancestors. The concepts and my faith in my ancestors are what’s going to take us there.”

island. In the morning, the birds wake up and head out from the island to fish and eat. So we go in the opposite direction,” he continued. Ellis said when birds are spotted, they start their search for an island. He said there are navigators on board who keep track of where they are heading and the crew member’s job is to steer the canoe in the right direction.

experimental educational programs that inspire students and their communities to respect and care for themselves, each other, and their natural and cultural environments.” Ellis said they offer classes and training and you can find more about it at hokulea.com. • Learn more

According to the Polynesian Voyaging Society’s website, its mission is to “Perpetuate the art and science of traditional Polynesian voyaging and the spirit of exploration through

BY MUTIA PARASDUHITA

Right before reaching Heeai Kea, Iosepa came across a capsized boat with three passengers holding onto the top of it, said Mahina Okimoto, one of Iosepa’s crew members from Laie.

“Iosepa came just in time. There weren’t any other boats in the vicinity, so had we not been there, they probably would have drifted in, hit the reef and gotten into a lot more struggle,” said Michael Horito, another Iosepa crew member from Hau’ula.

During the rescue, Horito said the Iosepa and the escorting boat connected a robe and threw it into the water for the boat passengers to hold on and get out. He added, “I was only making sure I was doing whatever was assigned to us while saving them. We also needed to make sure the Iosepa stayed safe.”

Horito added, “I heard [the people on the boat] were at the fishing tournament. They were working on the nets at the back of their boat [when] a large wave came and flipped it over. [They] didn’t have enough time to react. They had a radio, but it was ruined underneath [the water].”

“When the canoe is being put in a museum, people tend to think it was only the past artifact. But when it sails, it has the power to save, the same as Iosepa.”

Okimoto said not long after navigating the canoe from the calm water of Haleiwa toward Heeia, the weather turned cold. She explained the waves turned rough around Kahuku Point as the strong wind hit the ocean.” Iosepa was rocking up and down [causing] half of our crew members to get sick and throw up, but we still persevered and held our course,” she said. Five minutes after breaking through the rough waves, she said Iosepa encountered the capsized boat.

Kahia Walker, Iosepa’s quarter master from Hau’ula, said the boat was drifting in the ocean for a long time. “It’s about a mile from the shore, far enough for people to notice.”

“When the canoe is put in a museum, people tend to think it is only a past artifact. But when it sails, it has the power to save, the same as Iosepa,” he added. He took this accident as an example of a living gospel. “Iosepa needed to be in the water. Had it not been in the water, it wouldn’t have rescued the life that needed to be rescued,” he said. If the members of the Church are not ready to embark on the gospel, the people around them will fail to receive the blessings that are in store, said Walker. •

Koa trees are native to the Hawaiian Islands. Koa wood is known for its strength and unique wavy grain, making it extremely expensive.

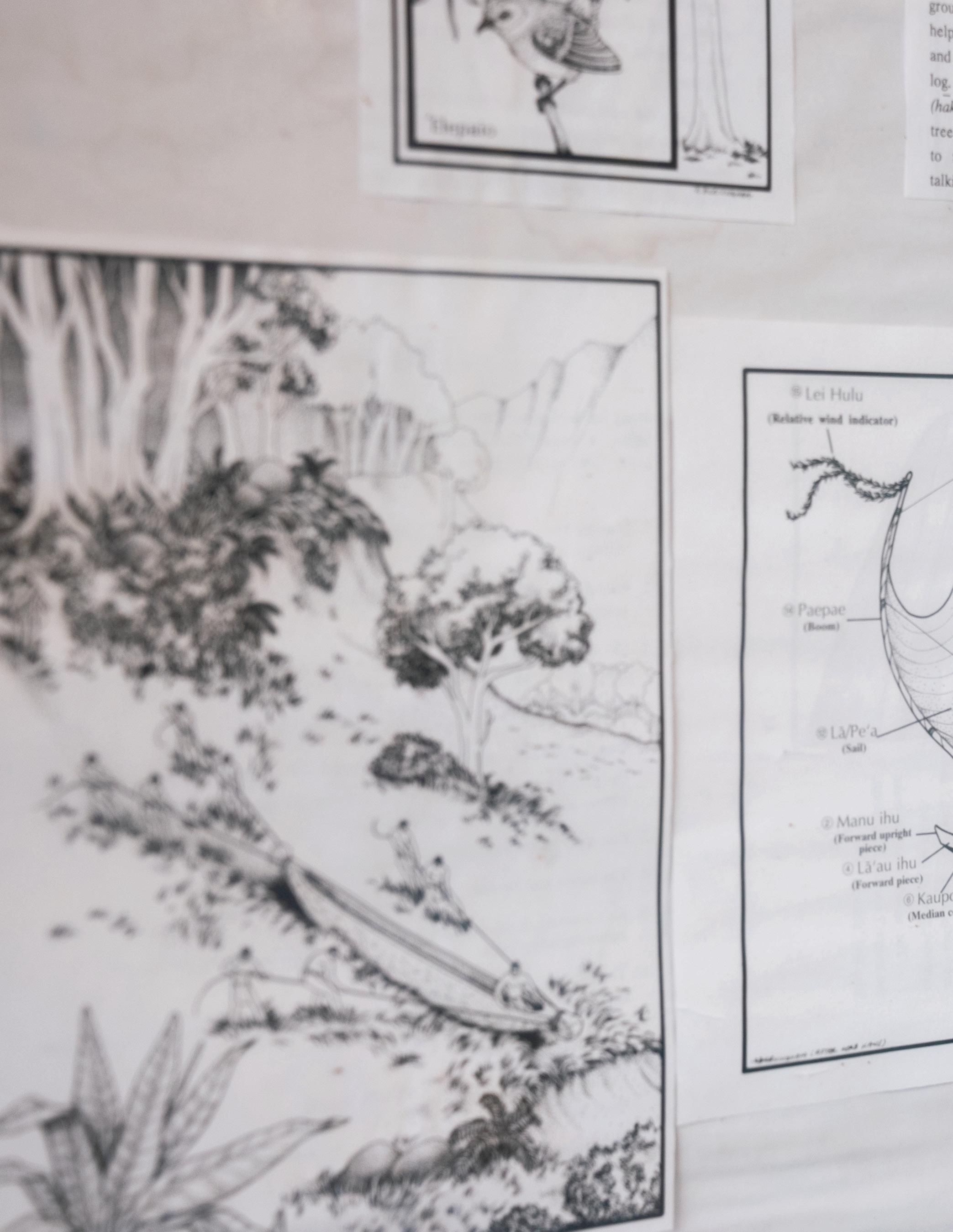

Ko’i are traditional carving tools used in the carving of canoes. There is a variety of Ko’i variations used for different steps in the carving process.

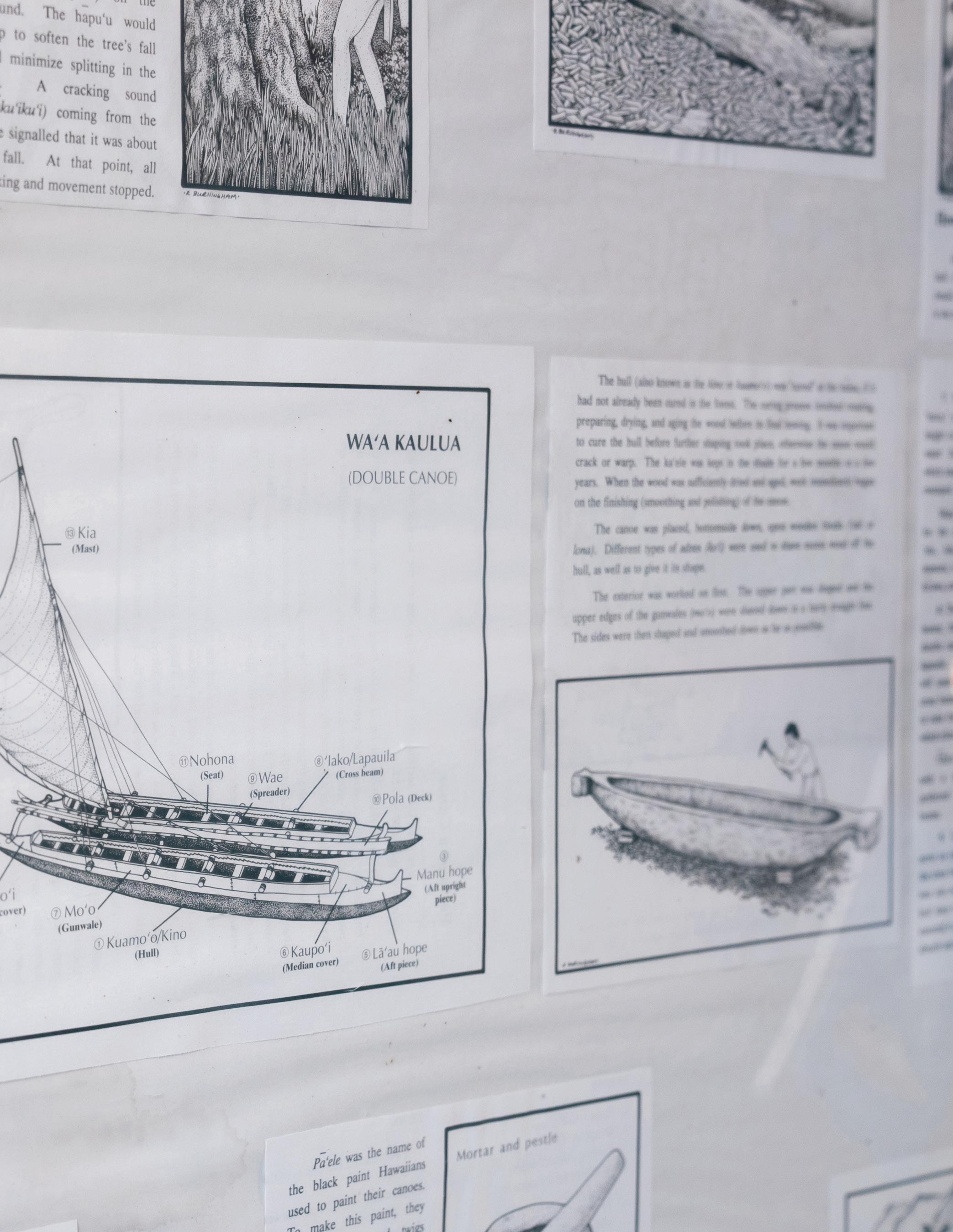

The Iosepa is made up of several pieces glued together. The master carvers didn’t use a blueprint, only relied on a model.

Iakos are in integral part of a canoe. They connect the two canoes together and must be strong enough to hold the crew and cargo.

The most difficult part of launching a canoe is getting it over the sand and into the water. The launch of the Iosepa was attended by over 2,000 people.

The union of two canoes is a sacred event as it is seen as two individuals becoming one unit, not unlike a marriage.

A total of seven logs of koa wood were harvested from Fiji and shipped over 3,000 miles to Laie, Hawaii. Six of the logs weigh over 6,000 pounds.

Master carvers Kawika Eskaran and Tuione Pulotu carved the main parts of the canoe from the koa logs. A combination of modern and traditional tools were used. Along with chainsaws and sanders, workers uses tools like ko’i.

Hundreds of community volunteers contributed their time and effort to building the Iosepa.

To connect the canoe, the team create iakos. Iakos are made from several sheets of pine wood glued together and bent in its unique load-bearing shape.

The two canoes were joined in a special ceremony held by BYUH Professor William Wallace. Then, the canoe was repeatedly sanded and painted with a special marine varnish to protect the wood from water damage.

When the Iosepa was ready to launch, an ahaaina, or celebration feast, was held. Afterwards, the boat was pushed by hundreds of community members into the water. The Iosepa then embarked on its maiden voyage!

Pictures from the

Iosepa’s first launch on Nov. 3, 2001 at Hukilau Beach in Laie. Photo by Mike Foley.