potential A publication of Kennedy Krieger Institute

Bringing Back Kat Turning Trauma Around

From Fear to Resilience

Kid Warrior

Fighting to Walk Again

Language for All

How Words Can Change a Child’s Life

We are all born with great

potential .

Shouldn’t we all have the chance to achieve it?

A publication of Kennedy Krieger Institute Volume 17, No. 1 • Summer 2017

INSPIRING POTENTIAL With a Good Attitude, ‘Anything Is Possible’ How a teen with a spinal cord injury stays positive by giving back, encouraging others and looking ahead.

3

FEATURES

Letter from our

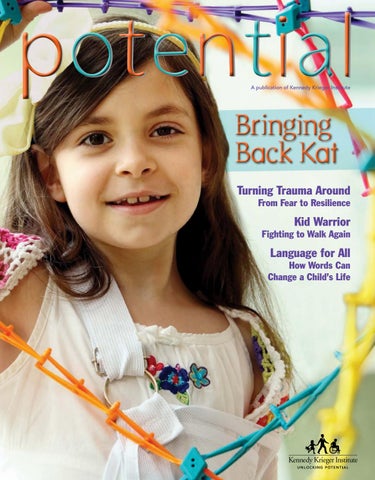

President At Kennedy Krieger Institute, we treat 24,000 patients a year. They come from other continents, countries and states, and from right here in Maryland and Baltimore. Often, they’re here because they’re not able to get the help and care they need anywhere else. This issue of Potential introduces you to a few of those patients. Doctors, therapists and other Institute specialists worked with Kat, 7, pictured on the cover, to help her recover from a traumatic dog attack that left her severely traumatized, with wounds all over her body and a paralyzed left arm. Recently, she started feeling the positive results of nerve surgery and therapy performed on her arm, and she’s looking forward to playing, unassisted, with Lego bricks again. We’re one of the top hospitals in the country for treating children with acute flaccid myelitis, an inflammation of the spinal cord, and that’s why a Pennsylvania doctor recommended that Sebastian be brought to our hospital right away. The disorder is rare, but it paralyzes children’s limbs, taking away their ability to walk and be independent. Rehabilitation therapy is long and arduous, but Sebastian, only 6, embraces his therapy with a superhero’s spirit. Mustafa, 8, is one of our newer patients and is hard of hearing. He was born abroad and lacked access to language for years. This past spring, he was seen for the first time at Kennedy Krieger, and he’s already learning American Sign Language. Julian, who’s entering his senior year of high school this fall, is also hard of hearing. He’s been working with our therapists and doctors since he was a child and is doing so well that he’s applying to college in the fall. This issue of Potential also features the inspiring stories of Zyaira and Sarah Todd. I hope you enjoy reading about their journeys, and I wish you well on the journeys that await you this summer and fall. As always, we’re grateful for your interest and support. Sincerely, Gary W. Goldstein, MD President and CEO On the cover: 7-year-old Kat, who is recovering from a spinal cord injury

Turning Trauma Around A mother-daughter pair finds resilience and hope at the Center for Child and Family Traumatic Stress.

4

Kid Warrior AFM may have taken away Sebastian’s ability to walk, but he’s fighting back—superhero-style—one step at a time.

6

Bringing Back Kat A team of specialists—and a loving family—helps a little girl heal in body and spirit.

8

RESEARCH FRONTIERS Mining Big Data for Clues to Autism Before precision medicine can be used to treat autism, more must be known about the genetic causes of the disorder.

11

PROGRAM SPOTLIGHT Language for All The DREAM Clinic helps deaf and hard-of-hearing children communicate their thoughts and feelings and let their personalities shine. 12

IN MY OWN WORDS From Patient to Teacher Kennedy Krieger once helped Amy Dykes recover from a brain injury. Now, she’s the teacher—at the Institute’s Fairmount Campus.

14

NEWS BRIEFS & EVENTS Kennedy Krieger in the news and upcoming Institute events. 15

POTENTIAL EDITOR

Laura L. Thornton ART DIRECTOR

CREATIVE SERVICES MANAGER

Sarah Mooney PHOTOGRAPHY

Amy Mallik

Robin Sommer

DESIGNER

DIRECTOR OF MARKETING

CONTRIBUTING WRITER

MEDIA INQUIRIES

Erin Parsons

Lisa Nickerson

Christianna McCausland

Stacey Bollinger

PROOFREADER

PUBLICATION INQUIRIES

Nina K. Pettis

443-923-7330 or TTY 443-923-2645

For appointments and referrals, visit KennedyKrieger.org/PatientCare or call 888-554-2080. Potential is published by the External Relations Department of Kennedy Krieger Institute, 707 North Broadway, Baltimore, MD 21205. Kennedy Krieger Institute recognizes and respects the rights of patients and their families and treats them with courtesy and dignity. Kennedy Krieger Institute provides care that preserves cultural, psychosocial, spiritual and personal values, beliefs and preferences. Care is free from discrimination based on age, race, ethnicity, religion, culture, language, physical or mental disability, socioeconomic status, sex, sexual orientation, and gender identity or expression, including transgender. We encourage patients and families to become active partners in their care by asking questions, seeking resources and advocating for the services and support they need. To update your contact or mailing information, email PotentialMag@KennedyKrieger.org. If you do not want to receive future communications from Kennedy Krieger Institute, you may notify us by emailing Unsubscribe@KennedyKrieger.org or visiting KennedyKrieger.org/Unsubscribe. © 2017, Kennedy Krieger Institute

For more inspiring stories, news and updates, visit PotentialMag.KennedyKrieger.org.

INSPIRING POTENTIAL

With a Good Attitude,

‘Anything Is Possible’ By Sarah Todd Hammer

How one teen with a spinal cord injury stays positive—and on track with her recovery—by giving back, encouraging others and looking ahead.

A

s our plane landed in Baltimore on Oct. 17, 2014, I couldn’t have been more excited. I reminded my mom that on the same day four years earlier, we’d landed in Baltimore for the very first time, only then, I couldn’t walk well, my arms and hands were really weak, and I was extremely nervous. This time, though, I was happy and jittery. That’s because I was headed to the Baltimore Running Festival to participate in the event’s 5-kilometer race as a member of Team Kennedy Krieger. I wanted to give back to the wonderful people who’d done so much to help me, and this was the perfect way to do that. When I was diagnosed with transverse myelitis—a rare neuro-immunological disorder that injures the spinal cord, causing paralysis and weakness—in 2010, nobody seemed to know what the disorder was except for the brilliant doctors and therapists at Kennedy Krieger Institute and The Johns Hopkins Hospital. They even knew how to treat it! Since my first visit, I’ve returned 12 times, each time accomplishing something special. On that October day in 2014, with the encouragement of my wonderful therapists, I crossed the Baltimore Running Festival’s 5K finish line, despite having a spinal cord injury and having been a quadriplegic only four years before. It’s one of my favorite memories of Baltimore, a city that holds so many memories for me that I will cherish forever.

When I was in Baltimore in 2012, I met another teen with transverse myelitis (also known as TM). Together, we wrote and published “5k, Ballet, and a Spinal Cord Injury” (she’s a runner and I’m a dancer), a double autobiography in which we each share our unique journey with TM up to 2012. The book’s success inspired a sequel—the newly published “Determination,” which continues our journeys up to 2014. As a thank-you to my therapists, nurse practitioner and doctors for helping me make such a splendid recovery, I am donating one-third of the proceeds from “Determination” to Kennedy Krieger’s International Center for Spinal Cord Injury.

Every time I’ve been to Baltimore, I’ve received excellent care, and that’s inspired me to want to do the same for others. One day, I hope to work as a doctor—perhaps as a neurologist, psychiatrist or oncologist—while writing books on the side. Throughout my journey, I’ve learned that it’s important to pursue your dreams and make them happen, no matter what obstacles may be thrown your way. Many readers have said that my books have helped them understand what having TM is like—whether they’re a friend or a parent of someone diagnosed, or simply someone interested in my story. Through my books, I’ve inspired others—especially those with TM—to be positive and believe that anything is possible when you have a good attitude. To learn more about Sarah Todd Hammer’s books, visit KennedyKrieger.org/SarahTodd. Sarah Todd Hammer, diagnosed with transverse myelitis as a child, is now a high school student and a published author. She would like to attend college and become a doctor.

PotentialMag.KennedyKrieger.org

3

G N I N TUR

A M U A TR D N U O R A

d hope n a e c n and resilie Finding enter for Child ss e at the C Traumatic Str d Family tianna McCauslan By Chri

ost s like m e i a r i a y rid ways, Z loves to r e h n many S . s l o he old gir te and d a 9-yeark s r e l , rol r mom her bike kes to help he But vorite. . She li a r i f a a h s i n e ow er ees rilled ch Kennedy Krieg ily g — k o o c e to Fam he cam hild and a C r o f when s r e s e's Cent , she wa Institut Stress in 2013 tic Trauma ent child. fer a very dif er have h t a f r e gh er itnessin ck, she and h ore a After w t t m heart a to Balti massive arisse, moved aira’s , Zy , Ch mother Virginia. Soon ealth were sh ral from ru ver her father’ anxiety and so on hy concern ed by separati chool. S s d y t n i c u o a and g to comp eserved djustin r a e y t b l d u l c i diff le a wou ntrollab e, Zyair r o c u t n a u n e by to hav nd then She was afraid a , t e i in a u q . e talked ntrums h a s t d r e n p a tem ght, ne at ni essed. o l a p e sle n str ice whe o v y b a b

I

4

s

Following a recommendation from her middle daughter, Charisse brought Zyaira to the traumatic stress center, where therapists evaluated both mother and daughter for trauma. They found that Zyaira suffered from anxiety over her father’s health and from her separation from him. She struggled in school due to a language disorder and because she was being bullied for being in special education classes. “When we first met, Zyaira was very shy and timid, and she denied her feelings—everything was always ‘fine,’” says Emily Driscoll-Roe, one of the center’s social work managers. “We really tried to help her put her thoughts into words, which was a struggle for her for many reasons.” Children, adolescents and their families are generally referred to the center, which was founded in 1984, for treatment of mood or behavioral symptoms, Social work manager Emily Driscoll-Roe which are often either works with Zyaira. caused or affected by trauma exposures. Typically, the children and adolescents seen at the center have experienced at least one form of trauma, such as the loss of a loved one, community violence, domestic or sexual abuse, a car accident, or stress related to immigration. The trauma compounds any clinical diagnosis a child or adolescent may also have. The source of a child’s or adolescent’s trauma may be in or near the home, and children, adolescents and their families often enter the clinic while experiencing a high level of stress, says Sarah Gardner, the center’s director of clinical services. “We create a strong partnership with parents and caregivers,” Gardner says, “so that they get the support they need to manage their stress and advocate for their children and teenagers in what can be very challenging situations and systems.” While treatments for a child’s clinical needs do exist, reminders of a past trauma may remain in a child’s environment. Zyaira couldn’t simply move to another school where there were no bullies, for example. For Zyaira, resilience was the key to success. “The biggest thing with Zyaira, and with all the kids, is to develop coping strategies,” Driscoll-Roe says. “We focus on building on a child’s strengths and having them participate in the process of finding what works for them when things aren’t going right.” Zyaira’s evaluation at the center identified school as a significant challenge. “Her school resisted adding services to her individualized education program [IEP], so we supported Charisse in her advocacy to help Zyaira get the services she needed through school,” Driscoll-Roe says. “I’ve also been going to the school to touch base with them in person to make sure her IEP is being met.”

Zyaira has been able to access a wide range of services throughout Kennedy Krieger. She went to the Center for Development and Learning for an assessment to better pinpoint her learning challenges. A neuropsychological evaluation provided new information that helped build her a stronger IEP. She attends individual and group therapy, and she takes medication to manage her anxiety. She participated in a social skills therapy group with her peers, and she receives reading support at the Child and Family Support Center. All of that has helped her engage more at school.

“Zyaira still has a lot of challenges, but they’ve given her the tools to get over some mountains. They’ve given us so much hope.” – Charisse, Zyaira's mom

Zyaira’s mother also attends therapy, at the Child and Family Support Center, which has been invaluable to her ability to support her daughter. “Kennedy Krieger opened a door for Zyaira and for me,” Charisse says. “I was in denial for a long time about what was going on. When I got frustrated with her, I’d get mad and walk away. Now I’m in therapy, and they showed me how I can change and what I can work on. Now, we try to talk things out and use all the tools Kennedy Krieger has given us.” Some of the tools Zyaira finds effective include squeezing stress balls (which she keeps inconspicuously in her backpack), deep breathing and positive visualization. Perhaps most importantly, she no longer uses baby talk and has learned to talk about her feelings without embarrassment and to speak with an adult when she needs help. “She’s learned to maintain a good attitude and has become outspoken,” her mother says. “It’s still hard for her to make friends, but she tries. And the kids still make fun of her, but she can defend herself better against the bullying.”

With the help of her therapists, Zyaira has learned to talk about her feelings without embarrassment.

Charisse hopes her daughter will make it through school. She’d love for Zyaira to attend college. Life isn’t easy for them, but it finally seems manageable.

“We’ve learned to be each other’s strength in tough times,” Charisse says. “Zyaira still has a lot of challenges, but they’ve given her the tools to get over some mountains. They’ve given us so much hope.” To contact the Center for Child and Family Traumatic Stress, visit KennedyKrieger.org/TraumaticStress, or call the designated intake line at 443-923-5980.

PotentialMag.KennedyKrieger.org

5

Kid WARRIOR AFM took away Sebastian’s ability to walk, but he’s fighting back—superherostyle—one step at a time.

Ask Sebastian what he wants to be when he grows up, and he’ll tell you: “A warrior!” It’s a fitting aspiration for a boy named after the patron saint of soldiers. But Sebastian is already a warrior. He fights every day to walk, gain strength, redevelop motor skills, and get back to the business of being a 6-year-old after developing acute flaccid myelitis (also known as AFM) last August.

Sebastian works on using his right hand again with Shannon Iuculano, his occupational therapist. 6

PotentialMag.KennedyKrieger.org

AFM is a condition that damages the part of the spinal cord controlling movement, often paralyzing arms and legs, particularly in the shoulders and hips. It does not always cause loss of movement in hands and feet, however, and it doesn’t affect cognitive functioning, explains Janet Dean, a pediatric nurse practitioner for Kennedy Krieger Institute’s International Center for Spinal Cord Injury (ICSCI). Its cause is not fully understood.

In the last few years, the number of patients admitted to Kennedy Krieger with a diagnosis of AFM has increased dramatically. Since 2014, Kennedy Krieger has admitted 17 patients with AFM to its inpatient rehabilitation program, while in the decade before that, it treated only 14 patients whose symptoms would meet today’s definition of AFM. In 2014, 120 cases of AFM were recorded in the U.S., and in 2016, that number was 138, according to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC). AFM’s rarity makes it difficult to study. Researchers think that one trigger for AFM may be a virus— possibly enterovirus D68, which typically causes only mild congestion, fever and pain. The CDC reports that other viruses—including poliovirus, West Nile Virus and adenoviruses—may also trigger AFM. AFM is often preceded by cold-like symptoms. Typically, an entire family will have a cold, but only one family member will go on to develop AFM, “and that puzzles AFM researchers,” says Dean, the Institute’s AFM expert.

Therapy Is the Key

Wild Imagination, Strong Spirit

Sebastian and his mom and siblings came down with a cold a couple of weeks before he developed AFM. Everyone else but Sebastian recovered, although initially, he seemed to be on the mend. But over the course of an afternoon, he went from being a little sleepy to not being able to move his legs and right arm at all. No specific virus has been identified as having caused Sebastian to develop AFM.

It takes kids with AFM a long time to see any progress, and only about 5 percent fully recover, Dean says. That makes any progress—however slight—very exciting. It also makes therapy an opportunity for Sebastian, who loves superheroes—Batman is his favorite, to take on some superhero-like tasks in real life.

For the next two months, Sebastian adhered to a rigorous activity-based restorative therapy (ABRT) routine while staying at Kennedy Krieger’s inpatient hospital. After discharge, he continued his intensive ABRT—initially for five hours a day, six days a week—at the ICSCI’s outpatient clinic.

At one of Sebastian’s earliest therapy sessions, a therapist who hadn’t yet worked with him asked him to start walking with the aid of knee immobilizers, while she held on to him from behind.

Kennedy Krieger’s AFM program is one of the best in the country, thanks to the Institute’s decades of experience in treating children and young adults with spinal cord injuries. Experience has shown that rigorous therapy—particularly physical, occupational and aquatic—can help patients regain some movement, Dean says. Some patients may be able to walk again, while others may regain only a small amount of movement. “Even a slight increase in head, hand or foot control can be monumental if it allows a child to drive a motorized wheelchair,” Dean says. ABRT includes patterned activities like picking things up and putting things down, and practicing walking while suspended in a harness over a treadmill. “We want kids practicing movement patterns again and again to help heal and reeducate damaged nerves and weakened muscles,” Dean says. The Institute also uses whole-body vibration therapy, in which a child stands—with assistance—on a vibrating plate. The vibrations “help muscles contract without having to rely on the spinal cord,” Dean says. “Even if a child cannot walk, we want him or her to practice standing,” which stretches muscles and joints and helps bones stay strong. A big part of rehabilitation is getting kids ready to return to their everyday lives. Occupational therapists help children improve arm and hand strength and coordination, and they help children relearn basic tasks— like dressing and brushing teeth— and school skills like writing, drawing and using scissors. Other members of the Institute’s AFM team include physical therapists, recreational therapists, speechlanguage pathologists, child life specialists, psychologists, social workers, doctors and nurses. Right: Sebastian now walks with the aid of a walker and a knee-immobilizing device. Opposite, top: Sebastian works with his physical therapist, Meredith Budai, and with rehabilitation technician Jack Luttrell.

Sebastian hadn’t walked since developing AFM. His mom, Christa, figured the therapist would soon see that what she was trying to get Sebastian to do was unrealistic at the time. But Sebastian surprised his mom, and before she knew it, he’d walked across the therapy room, with the aid of his therapist, right into her arms. If Superman could fly in a comic strip, Sebastian could walk in real life. “All of a sudden, I saw that maybe all of this therapy really could work,” Christa says. Now, Sebastian walks with the aid of a walker and a knee-immobilizing brace. After weeks of occupational therapy, Sebastian, who is right-handed, was finally able to use his right hand again. Then, during breakfast one morning, he started flexing his right biceps muscle. His new-found flexing ability seemed to come out of nowhere—and it made that breakfast a meal to remember for the whole family. “It was just as unexpected,” Christa says, “as if a fork had started walking across the table!” One of the reasons Sebastian has made such great progress is that his family is very involved with his recovery, says Meredith Budai, his physical therapist. His siblings are always ready to help him out, and when they join him at therapy, “he’s really excited to show off his therapy equipment and how well he’s walking.” Another reason is Sebastian himself—and his wild imagination and indefatigable spirit. “With Sebastian, we can turn what we call ‘ work’ into something fun and exciting,” Budai adds, “even when it gets harder and even more challenging. “He’s a very resilient little boy”—a warrior fighting to be a kid again—and his dedicated team at Kennedy Krieger is right there with him, helping him win his toughest battle yet. To learn more about acute flaccid myelitis, visit KennedyKrieger.org/AFM. 7

Bringing Back Kat How a team of specialists—and a loving family— helped a little girl heal in body and spirit.

8

Ask 7-year-old Kat what she wants to do when she grows up, and she’ll tell you, as if on cue, “To help hurting children and make them happy!” Kat—short for Katarina—knows a lot about being happy. She loves playing with her friends, dancing, gymnastics, Legos, animals, the beach, and her close-knit family, which includes three doting older sisters. But Kat also knows about hurting. Just before Christmas 2015—only a day before she turned 6—she was attacked by two large dogs. The unprovoked attack ripped all five nerves that extend down the length of her left arm from their roots, paralyzing the arm. It also injured her spinal cord, fractured her skull and left her with wounds all over her body. “Kat technically died on the helicopter ride to the hospital and had to be revived,” says her mom, Sandy, who was seriously injured while trying to save her daughter. Kat was transported first to a hospital in Virginia, near where the attack happened, Dr. Eboni Lance checks in with Kat. then to The Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore for further treatment, and then to Kennedy Krieger Institute’s inpatient hospital, a few blocks away from Johns Hopkins, to begin the long process of rehabilitation. Her wounds were extensive, and her pain was excruciating. Her left arm’s nerves had suffered the worst possible kind of nerve injury, and nerve pain is far more intense than that of a flesh wound, explains Dr. Eric B. Levey, director of Kennedy Krieger’s Pediatric Pain Rehabilitation Program, and one of the doctors on Kat’s care team. But it was Kat’s trauma that really worried Sandy. When Kat arrived at Kennedy Krieger, “even though the doctors had saved my daughter’s body, her mind was still trapped in the trauma,” Sandy says. “She would just stare, blankly, her words frozen, her actions [those] of someone trying to escape from something horrifying.” Hospitals and doctors’ offices naturally became trigger points for post-traumatic stress disorder. Sandy was suffering from PTSD as well, and she worried how she’d help her daughter recover. Dr. Eboni Lance, a pediatric neurologist and one of Kat’s two attending doctors—the other was pediatric neurologist Dr. Joanna Burton, knew that caring for Kat also meant caring for her family members, “all of whom had experienced significant trauma,” she says.

Dr. Lance briefed members of Kat’s care team about Kat’s and Sandy’s conditions and kept them up to date as Kat’s physical and emotional therapies progressed. It would have been too traumatic for Sandy to have to talk about the attack every time Kat had an appointment. The extra effort paid off: “It allowed me to step back from what was going on so that I could just be Kat’s mom”— not her medical history chronicler, too.

Kat and her occupational therapist, Gayle Gross.

Ultimately, Kat’s care team included doctors, nurses, therapists and specialists from the Institute’s nursing, behavioral psychology, rehabilitation, child life, and physical and occupational therapy departments, and from Johns Hopkins’ surgery, plastic surgery and neurosurgery departments. Once, when Sandy was sitting at a conference table with several doctors discussing her daughter’s care plan, she started tearing up. Sandy recalls the doctor sitting next to her grabbing her hand and holding on, giving Sandy the emotional support she needed to get through the meeting.

Fairies to the Rescue One of Kat’s first tasks was to get up and walking again. She needed to keep her muscles moving so they wouldn’t atrophy, but her mind was still so stuck in the memory of the attack, and she was in so much pain, that she had little desire to do anything. Kat’s therapists took a playful approach: They dressed up like fairies, dancing around Kat in her wheelchair, encouraging her to take those first, painful steps, Sandy says. Kat’s nurses filled her room with stuffed animals, changing “She would just stare, the animals’ locations every day to make the room more interesting and blankly, her words less frightening. frozen, her actions Kat’s psychologists had some of the hardest work to do. “When PTSD took over, Kat would hide, toss her chair, pull my hair, and go back to that moment of survival,” Sandy says.

[those] of someone trying to escape from something horrifying.” – Sandy, Kat’s mom

Her psychologists figured out that she liked checklists, so they developed a checklist of different coping mechanisms Kat could use when she felt anxious. “Kat’s family was really great at encouraging Kat to try out all of the different coping strategies—like deep breathing—that we recommended,” says Dr. Christi Culpepper, a psychologist at Kennedy Krieger. >>

Opposite: Kat, surrounded by some of the members of her care team: from left to right, child life specialist Shereé Sheffer, pediatric neurologist Dr. Eboni Lance, occupational therapist Gayle Gross and educational specialist Patty Porter PotentialMag.KennedyKrieger.org

9

Bringing Back Kat (continued from page 9)

One day, while Kat was having her blood pressure taken—a big PTSD trigger for her—she looked at the checklist and asked the nurse, “Can you give me a minute, please? I’m having a hard time.” Now, more than a year later, Sandy says, “we don’t need the checklist anymore.”

No Place Like Home

Over the past few months, after nearly a year of rigorous occupational therapy, Kat’s started to get some feeling back in her left arm, and she can wiggle her left fingers a bit. She’s excited about the prospect of using her arm again, Sandy says. When Kat returned to school last fall, headaches and nerve pain kept sending her to the nurse’s office. Dr. Lance arranged for Patty Porter, one of Kennedy Krieger’s educational specialists, to work with her teachers to schedule rest breaks throughout the day. The breaks keep Kat from developing so much pain that she spends all day in the nurse’s office.

Kat’s trauma was so acute that Dr. Lance made the decision to discharge Kat from the inpatient hospital only about Child Life specialist Shereé a month after she’d been Sheffer works with Kat. admitted. “The best move, for her and her family,” Dr. Lance says, “was going home and continuing her recovery there.” It was better for her family, too. Sandy and her other daughters had become so traumatized by everything that had happened that they were having trouble just walking back to their car in the parking garage. Kennedy Krieger’s security guards “were always ready to escort us,” but it remained a daily stressor. Being at home helped Kat—and her family—turn a corner. “A big part of Kat’s continued success has been the support she gets from her parents and sisters,” Dr. Lance says. “Without that, I don’t think she would have had the success that she’s had in her recovery.” Before Kat left the hospital, her occupational therapists trained Sandy in the therapies Kat would need to continue doing. Dr. Lance helped arrange for additional therapy appointments closer to Kat’s home, and she encouraged Sandy to call her whenever she had any questions. By April 2016, Kat was ready for a nerve transplant to try to restore some function to her paralyzed arm. Johns Hopkins surgeons Dr. Alan Belzberg and Dr. Richard Redett took nerves from her leg and used them to attach nerves from the right and left sides of her neck to damaged nerves in her left arm, explains Dr. Frank Pidcock, Kennedy Krieger’s vice president of rehabilitation.

Kat reads a book with educational specialist Patty Porter, left, and her mom, Sandy.

Attending school was crucial to Kat’s recovery, says Dr. Lance, who didn’t want Kat getting used to staying home all day. By the time her birthday rolled around again, Kat was back. To celebrate, she donated her birthday and Christmas gifts to kids at Kennedy Krieger. She wanted to help the kids feel a little better during what’s supposed to be a festive time of year. Kat still has a long recovery ahead of her, but as she gave away her gifts, she was no longer a little girl wracked with fear and pain. She was a strong girl, happy to be getting her old self back, and ready to help other kids get their lives back, too.

Watch a video about Kat at KennedyKrieger.org/Kat. To learn more about some of the departments mentioned in this story, visit the following websites for more information: • Behavioral Psychology Department: KennedyKrieger.org/BehavioralPsych • Child Life/Therapeutic Recreation Department: KennedyKrieger.org/CLTR • Inpatient programs: KennedyKrieger.org/Inpatient • Occupational Therapy Clinic: KennedyKrieger.org/OccupationalTherapy • Pediatric Pain Rehabilitation Program: KennedyKrieger.org/PainRehab • Pediatric Rehabilitation Continuum: KennedyKrieger.org/RehabCenter • Physical Therapy Clinic: KennedyKrieger.org/PhysicalTherapy

10

PotentialMag.KennedyKrieger.org

RESEARCH FRONTIERS

Mining Big Data for Clues to Autism By Christianna McCausland and Laura L. Thornton

I

magine that it’s sometime in the future, and a child is being diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder, also known as ASD. A doctor samples the child’s DNA and sends the results to a laboratory. Within days, the child’s doctor knows not only which of the child’s genes have ASD-related mutations, but also where the “on-off” switches for those mutations are. The doctor prescribes a treatment to fix the mutations, and the child develops neurotypically. It may sound far-fetched, but it could be possible, someday. To get there, doctors and research scientists need to know a lot more about ASD-related mutations than they currently do. There’s a large absence of genetic data on ASD. Dr. Jonathan Pevsner is determined to help fix that. A researcher at Kennedy Krieger Institute’s department of neurology, he recently published a massive bioinformatics study crunching previously collected DNA data on close to 10,000 people with ASD— including 2,400 children—and their family members, with the help of data analysis software tools that he and his colleagues designed specifically for the task. In keeping with previous observations, Dr. Pevsner’s study identified thousands of new, or “de novo,” ASDrelated mutations. De novo mutations are not found in an individual’s mother or father and are, therefore, of great interest as possible catalysts for disease, Dr. Pevsner explains. Dr. Pevsner and co-author Donald Freed (then a graduate student working in Dr. Pevsner’s lab) also discovered several hundred so-called “mosaic” ASDrelated mutations never before identified. Mosaic mutations occur during a person’s development, either before or after he or she is born. They are neither inherited nor found in every cell in the body—the later the stage of

development during which the mutation occurs, the fewer the cells with the mutation. While the cells of a person with mosaicism are not all exactly alike, those cells nevertheless fit perfectly together to form a person—just like the many-colored tiles of a Roman mosaic comprise a picture. Mosaicism could explain, Dr. Pevsner says, why in some sets of “To confront autism and identical twins, one twin has ASD while the other does not. make progress, we need to Naturally, “finding these mosaic mutations,” Dr. Pevsner says, “is like looking for a needle in a million haystacks.” So far, he’s searched only blood-based DNA samples. Brain-based DNA samples, he says, could yield even more mutations.

know what we’re dealing with. Our research helps to make a little more sense out of the big puzzle that is autism.” – Dr. Jonathan Pevsner

Mosaicism also causes Sturge-Weber syndrome, Dr. Pevsner and his colleague Dr. Anne Comi—who directs Kennedy Krieger’s Hunter Nelson Sturge-Weber Center—discovered several years ago. The syndrome often features a large birthmark on the face, and it can cause strokes and seizures. Since that discovery, Kennedy Krieger researchers have been developing treatments for children with the syndrome. Identifying and finding out more about ASD-related mutations, mosaic and otherwise, can ultimately lead to precision medicine treatments—like the treatments now in development for kids with Sturge-Weber syndrome—designed specifically for kids with ASD. To learn more about autism initiatives at Kennedy Krieger, visit KennedyKrieger.org/ AutismResearch. To learn more about the Institute’s Center for Autism and Related Disorders, visit KennedyKrieger.org/CARD.

Read Dr. Pevsner’s article in “PLOS Genetics” on ASD-related mutations at KennedyKrieger. org/Pevsner1. Read more about his work on mosaicism and brain disease in a “Science” article at KennedyKrieger.org/Pevsner2. To learn more about Dr. Pevsner’s research, visit his laboratory’s website, KennedyKrieger.org/Pevsner3. 11

PROGRAM SPOTLIGHT

Language for All

M

A Kennedy Krieger clinic helps deaf and hard-of-hearing children get the treatments and services they need to communicate and let their personalities shine.

ustafa’s parents had always known their son was smart. But because of his limited access to language early in his life, they had a hard time getting others to believe it.

At age 3, Mustafa’s doctor in Yemen, where he was born, determined that Mustafa was deaf. Doctors fitted him with hearing aids, but the window for language acquisition—during which he might pick up Arabic, his family’s native language—was quickly closing. A few years later, his family moved to the Washington, D.C., area. Their new public school system evaluated Mustafa, determined that he was both deaf and intellectually disabled, and placed him in a program with students with similar diagnoses. As time went on, Mustafa, now 8, seemed to learn more while at home with his family than at school. “He just wasn’t in the right program,” his father, Sakher, says. “We knew his learning was delayed, but we still thought he could do better.” Mustafa’s parents found a new audiologist, who recommended a trip to Kennedy Krieger Institute’s Deafness-Related Evaluations and More (DREAM) Clinic. Then, one day earlier this year, Mustafa and his parents traveled to Baltimore to meet with Dr. Rachael Plotkin, one of the clinic’s three clinical neuropsychologists, for an evaluation that would change their lives.

‘The Little Clinic That Could’ Dr. Jennifer Reesman founded the DREAM Clinic within the Institute’s neuropsychology department in 2010. Although it’s a small clinic, it’s always had a big impact on the children and families it serves—and it’s the largest of its kind in the country.

I Love Learning!

“We’re the little clinic that could,” says Dr. Reesman, the clinic’s supervising neuropsychologist. From the start, the clinic has given children who are deaf or hard-of-hearing the opportunity to receive a full evaluation, referrals for other services, and training on how to communicate with others—whether through American Sign Language (ASL), spoken language, assistive technology or some other form of communication. Patients and their families fly to Baltimore from all over the country and around the world for evaluations at the clinic. Nowhere else can children receive so many services and have direct access to language, says Dr. Reesman, who, along with Dr. Plotkin, is fluent in ASL. Left: Eight-year-old Mustafa, who lacked access to language in early childhood, is learning American Sign Language at Kennedy Krieger. Language is opening up a whole new world for him. Above, top: Mustafa practices signing with neuropsychologist Dr. Rachael Plotkin. Above, bottom: Mustafa zips through a nonverbal reasoning task during an evaluation with Dr. Plotkin.

12

The clinic also collaborates with other Kennedy Krieger departments and—when appropriate—refers patients to other programs, such as the Institute’s Audiology, Assistive Technology, and Speech and Language Outpatient clinics. This interdisciplinary approach ensures that patients receive the best and most inclusive care possible.

“We want to understand the unique situation of every one of our patients. Our goal is to give children access to whatever they need to make their way in the world, and to ensure that they receive excellent care.”

The Right Diagnosis While Mustafa is just beginning his journey, Julian is gearing up to start his senior year at a mainstream high school, where he participates in choir, theater and band— he plays percussion—and is president of the anime club. “He’s on track to go to college,” says his mother, Tiffany. Julian has been hard of hearing since birth. He received hearing aids early on, but they seemed to have no useful effect on him. Doctors thought that was because he was hard of hearing, but his family suspected there was more to it. Every diagnosis seemed wrong to Tiffany.

– Dr. Jennifer Reesman

Language Opens Doors Dr. Plotkin and her team of graduate-level trainees evaluated Mustafa in the clinic and conducted a school observation earlier this year. What they found proved his parents correct: Long-standing language difficulties masked Mustafa’s strong cognitive potential. Because of inconsistent access to sound and language over the course of his childhood, Mustafa had not been able to demonstrate his learning and knowledge, and had, as a result, been misdiagnosed as having an intellectual disability. “Ask him his age, and he couldn’t answer, but give him a visual puzzle, and he’d figure it out,” Dr. Plotkin says. Mustafa’s situation is not unique. “Many of the children we evaluate have been misdiagnosed—often with intellectual disabilities,” Dr. Reesman says. Dr. Plotkin and her team recommended that Mustafa’s family and educational program focus on developing his functional communication skills via the Picture Exchange Communication System (also known as PECS), which facilitates communication through pictures. Mustafa picked it up very quickly and now uses it to communicate with his teachers, family and friends. He’s also starting to learn ASL, with Dr. Plotkin’s help. “With a consistent language at home and at school,” Dr. Plotkin says, “Mustafa will likely be better able to learn and demonstrate his potential even more quickly.” Dr. Plotkin is also facilitating the transfer of Mustafa’s schooling to the Maryland School for the Deaf by the start of the 2017–2018 school year. Mustafa’s family is excited about his progress. “Dr. Plotkin sees the potential in my son, and she’s gone above and beyond to help him,” Sakher says. And Mustafa’s face lights up when he sees Dr. Plotkin and they start signing— talking—with one another. Language is opening up a whole new world for him.

Julian, a rising high-school senior, meets with neuropsychologist Dr. Jennifer Reesman.

When Julian was 3, his pediatrician suggested an evaluation at Kennedy Krieger, where he received a diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder and—for the first time—the treatments he needed. Julian “All that Julian needed to be worked with specialists at Kennedy Krieger’s able to shine and be himself Center for Autism and was to find the right people. Related Disorders, and Dr. Reesman He found them at Kennedy guided him toward a Krieger, and they’ve been better understanding of how he learns best. family for a long time.” She worked with – Tiffany, Julian’s mom Julian and his family members and teachers to develop a plan for his education that would ensure his needs were met and keep him on a path to success. “Finding Dr. Reesman was a huge milestone for us,” Tiffany says. “We’d had a hard time finding specialists who could differentiate between how Julian’s hearing loss was affecting him, and how his other conditions were affecting him. Dr. Reesman was able to zoom in on exactly what we needed to do for him”—something the clinic does for its patients every day. To learn more about the DREAM Clinic, visit KennedyKrieger.org/DREAM. PotentialMag.KennedyKrieger.org

13

IN MY OWN WORDS

From

Patient to

Teacher By Amy Dykes

Kennedy Krieger once helped Amy Dykes recover from a brain injury. Now, she teaches the lessons she learned as a patient to her students at the Institute’s Fairmount Campus.

W

hen I was 18 and in my first semester of college, surgeons removed a large tumor from my brainstem and cerebellum.

The surgery was successful, but side effects were similar to those of a traumatic brain injury. I developed cerebellar cognitive affective syndrome, which disturbed my executive functioning, spatial cognition and language skills. I developed sympathetic storms, in which—for no apparent reason—I’d be thrown into a state of extreme agitation and hypertension. I lost most of my reflexes and developed hallucinations and insomnia. My doctors transferred me to Kennedy Krieger Institute, where days became weeks, and weeks became months. My neurological recovery was very slow and my future was uncertain. But my doctors, nurses and therapists were incredible. They continued to tolerate my unfiltered verbal outbursts and echolalia. As a last resort, I was put on a new drug. Within hours, I started turning the corner. Ten days later, I went home. In six months, I was back at college.

My care team members at Kennedy Krieger were always there for my family and me in the months and years that followed. My educational specialist worked with my college’s disability office to arrange for special accommodations. My social worker guided my parents through the process of caring for a child with a disability until I’d fully recovered. Doctors and therapists continued to offer suggestions, and family therapy was always available for my parents, brothers and me. I graduated from college with degrees in elementary and special education. I taught for two years in the public school system, but I wasn’t satisfied. I knew that I needed to move forward. The tools that my doctors, nurses and therapists had used with me at Kennedy Krieger had changed my life, and I wanted to use those tools to help students with special needs. When I saw the job opening for a teaching position at Kennedy Krieger’s Amy, abo Fairmount Campus, I surgery, in ut three months aft a custom knew I had to apply for -made w er her Kennedy hee Krieger’s it. My dream of working inpatient lchair at hospital. at Kennedy Krieger came true when I began teaching seventh- and eighth-graders with autism in August 2016. I felt like I was coming home. Teaching at Kennedy Krieger has been nothing short of amazing. By tapping into the interests of each one of my students, I’m able to engage with them and deliver education to them at their level. My students are quirky, very bright and—yes—at times difficult, but when tough moments happen, my colleagues fully support me. We work together in the best interests of our students. I love that Kennedy Krieger is such a positive place to be, and that its employees respect each other so deeply. I’ve learned that staying positive, patient, determined and persistent is the best way to meet one’s goals, and I try to model this for my students. As my first school year at Kennedy Krieger came to a close, I was more proud of my students than they’ll ever know. I was also proud of myself. In going from severely impaired patient to educator, I’d closed my own loop, moving on to help others just as I’d once been helped.

Amy Dykes began teaching at Kennedy Krieger’s Fairmount Campus in August 2016. To learn more about Dykes’ experience as a Kennedy Krieger patient, visit KennedyKrieger.org/AmyD. To learn more about Kennedy Krieger’s school programs, visit KennedyKrieger.org/SchoolPrograms.

NEWS BRIEFS & EVENTS

Kennedy Krieger Institute Named a Top Baltimore Workplace...AGAIN! In November, the Baltimore Sun recognized Kennedy Krieger Institute as one of the top large-size employers in the Baltimore metropolitan region, based on the results of the newspaper’s 2016 Top Workplaces survey. This was the second year in a row in which the Institute received this honor. Kennedy Krieger was also named the Top Workplace for Meaningfulness. Thanks to all Kennedy Krieger employees for making the Institute a truly inspiring place to work!

Santa Needs Helpers! Nov. 24–26, 2017 Maryland State Fairgrounds Plans are quickly coming together for Kennedy Krieger Institute’s Festival of Trees, the largest holiday-themed festival of its kind on the East Coast. We are looking for organizations and individuals interested in: • Sponsoring the event • Donating an item for the silent auction • Volunteering at the event • Setting up a Happy Holidays • Entertaining the crowds Fund page to help families from onstage in need • Designing a tree, wreath or gingerbread house for sale • Providing shopping opportunities as a vendor

To learn more, call 443-923-7300 or visit FestivalOfTrees.KennedyKrieger.org.

Fundraise Your Way Do you have a major milestone coming up? Are you looking for a unique way to give to Kennedy Krieger Institute? Anything can be turned into a fundraiser! Whether you’re collecting donations in lieu of gifts for a life milestone, cycling or running in a race, teaching yoga, baking, golfing or cutting off your hair, you can do what YOU want to support the more than 24,000 children and families for whom Kennedy Krieger Institute provides care each year.

To learn more or to get started, visit KennedyKrieger.org/FundraiseYourWay.

Join Team Kennedy Krieger at the Baltimore Running Festival

A ROARing Success More than 1,000 people took part in Kennedy Krieger Institute’s annual ROAR for Kids event at Oregon Ridge Park in Cockeysville, Md., on April 29. The 5K run, low-mileage walk and family festival raised nearly $130,000 to support research programs at Kennedy Krieger Institute. Congratulations to Landon Brown, who won the fourth annual ROAR for Kids Cara Becker Youth Fundraising Award by raising more than $2,300 for the event! And, thanks to all the sponsors, participants and volunteers who helped make this event possible!

Hats & Horses Raises $285K for New Technologies at Kennedy Krieger The Derby-themed Hats & Horses Benefiting Kids at Kennedy Krieger Institute event—which included a silent auction, seated dinner and dancing—raised more than $285,000, thanks to the sponsors, auction donors and more than 300 guests of the May 5 event. Event proceeds will help defray the costs of acquiring new rehabilitation technologies. Hosting the event was the Women’s Initiative Network for Kennedy Krieger, a volunteer organization dedicated to raising awareness of and resources for the Institute by promoting and facilitating volunteerism that assists families whose children are patients at the Institute. To learn more about WIN, visit KennedyKrieger.org/WIN.

Saturday, Oct. 21, 2017 • M&T Bank Stadium Sign up now for Kennedy Krieger Institute’s Baltimore Running Festival Charity Team, and help raise funds for individuals with spinal cord injuries. By registering with Team Kennedy Krieger, you’ll be committing to raising at least $250 for the Institute. Joining the team comes with a ton of perks, including free race registration, an additional Team Kennedy Krieger Under Armour shirt, bag check on race day, and so much more.

To learn more, get involved and stay connected, visit KennedyKrieger.org/Connect.

To join the team or for more information, visit KennedyKrieger.org/BaltimoreMarathon. PotentialMag.KennedyKrieger.org

15

NON-PROFIT U.S. POSTAGE

PAID

PERMIT #7157 BALTIMORE MD

707 North Broadway Baltimore, Maryland 21205

Help us find the keys to unlock her potential. When you give to Kennedy Krieger Institute, you’re helping us find the keys to unlock the potential of kids like Kat. Your gift will support groundbreaking research that brings hope, and innovative care that transforms lives. Thank you so much for your support!

Donate today using the return envelope inside this issue, or online at KennedyKrieger.org/PS17.

Kennedy Krieger’s Montgomery County Campus is moving! Kennedy Krieger Institute’s Montgomery County Campus has served children on the autism spectrum and those with other developmental challenges for the past 10 years. To allow enrollment at the campus to grow, we’re moving into a new school space this fall, complete with a playground and sports fields. Renovations are underway, and we’re raising funds so we can provide our students with everything they’ll need to fulfill their potential. To donate, use the enclosed envelope in this issue or visit KennedyKrieger.org/School.