HIDDEN TREASURES

GEOMETRY AND NATURE BETWEEN PAST AND PRESENT

KESKINER

KENT ANTIQUES

ISLAMIC & INDIAN ART ORIENTALIST PAINTINGS

KENT ANTIQUES

ISLAMIC & INDIAN ART

ORIENTALIST

Flat 3

107 Queen’s Gate

London, SW7 5AG

England

tel. + 44 (0) 20 7370 2914

mob. + 44 (0) 7887 985951

info@kentantiques.com

www.kentantiques.com

GEOMETRY AND NATURE BETWEEN

PRESENT

HIDDEN TREASURES

PAST AND

PAINTINGS KESKINER

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

First, I would like to thank former Sotheby's Middle East Deputy Chairman and contemporary art specialist Roxane Zand, for kindly accepting to curate our stand at TEFAF Maastricht 2024. Our collaboration for a new project inspired us for the concept of our stand and this catalogue, titled: “HiddenTreasures:Geometryand Nature Between Past and Present”. I would also like to thank Conrad Shawcross, Ben Johnson, Timo Nasseri and Ebtisam Abdulaziz for their most valuable contribution to our project and consigning their works to our stand at TEFAF.

We are indebted to many distinguished experts and scholars for their assistance during the preparation of this catalogue. Special thanks are due to Dr. Julian Raby who has generously shared his opinion on various matters. We are grateful to Persian and Indian miniature painting specialist Margaret Erskine for preparing the catalogue entries of the miniature paintings. We would like to thank René Bouchara for designing our stand and emphasizing the perfect harmony and dialogue we aimed to create between the classical and contemporary art works.

I would also like to take this opportunity to express my thanks to my brother Dr. Bora Keskiner who did extensive research and wrote the texts. The effective presentation of the art works would not have been possible without the participation of Mr. Peter Keenan, Mr. Richard Harris, and fine art photographer Mr. Richard Valencia.

Mehmet Keskiner Director

PREFACE

If music is considered a universal language, so is geometric abstraction whose origins lie in the laws of nature, and which early Islamic art brought into the visual canon as far back as the 7th century CE.

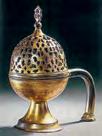

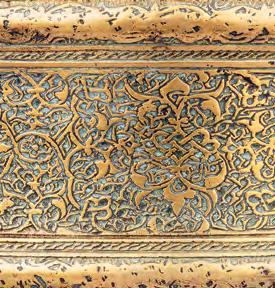

Islamic-inspired geometric abstraction has long been admired for its intricate patterns and motifs that have captivated artists, scholars, and audiences around the world. Rooted in the rich traditions of Islamic culture, it draws heavily from nature and demonstrates a profound connection to the natural world. From the elaborate geometric designs adorning architectural marvels to the delicate patterns found in manuscript illustrations, there is a deep reverence for the divine order and mathematical structure that underlies this beauty. Whether in Iznik ceramics or Ottoman textiles, in Islamic metalwork or Mughal miniature painting, we witness the presence and homage to nature.

At the heart of geometric abstraction is the principle of 'unity' - a holistic worldview that has inspired artists to seek harmony and balance in their compositions. Geometric patterns, commonly featuring stars, polygons, and arabesques, are meticulously crafted to reflect the mathematical precision and infinite complexity of natural forms, not only symbolizing the eternal nature of divine order but also mirroring the repetitive patterns found in nature, from the petals of a flower to the crystalline symmetry of snowflakes, from the spiralling patterns of seashells to the tessellating formations of honeycombs. Highlighting the underlying structures and rhythms found in nature, the intricate interplay of shapes and symmetries reflects the order and balance observed in an organic environment. We see the interconnectedness

of all creation, mirroring the interconnectedness of natural phenomena and the universe itself.

The enduring legacy of geometric abstraction and its relationship to nature continues to influence contemporary art and design around the world. Artists from both Middle Eastern and Western traditions have long drawn inspiration from geometric patterns and natural motifs - we only have to look more closely at the post-War movements of Opt Art, Constructivism, De Stijl, and Kinetic Art - even Bauhaus and Cubism - to see this quiet tide of influence. The transcendent allure of this type of abstraction continues to resonate across cultures, inspiring new generations of artists to seek meaning and inspiration in it.

Kent Antiques is proud to present a curated show based on this over-arching, unifying theme that underscores cultural commonality rather than separation. We look at the extraordinary creations of British artist Conrad Shawcross RA whose emphasis on the mathematical foundations of spatial order through the measure and relationships of forms has received global acclaim. Evolving from his earlier experimentation with grids and repetition, Conrad's more recent work (Patterns of Absence (MS20D17∆) painted and mirror polished stainless steel, mechanical system 200 x 200 x 16 cm.) explores the play of refracted light, the power of negative space, and the patterns generated through the lens of reflective metals. Dialoguing with Conrad's work, is a highly intricate piece by German-Iranian artist Timo Nasseri (STUPA Sculpture, Steel, magnets 3 + 1AP Artwork size, 19.0 x 19.0 x 74.0 cm) that references the convergence of architecture, philosophy and spirituality.

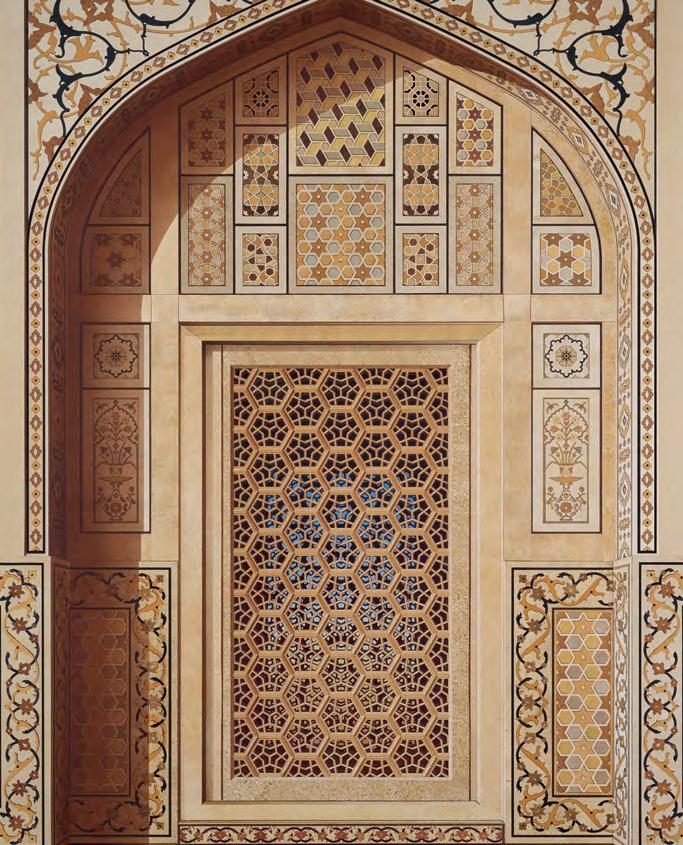

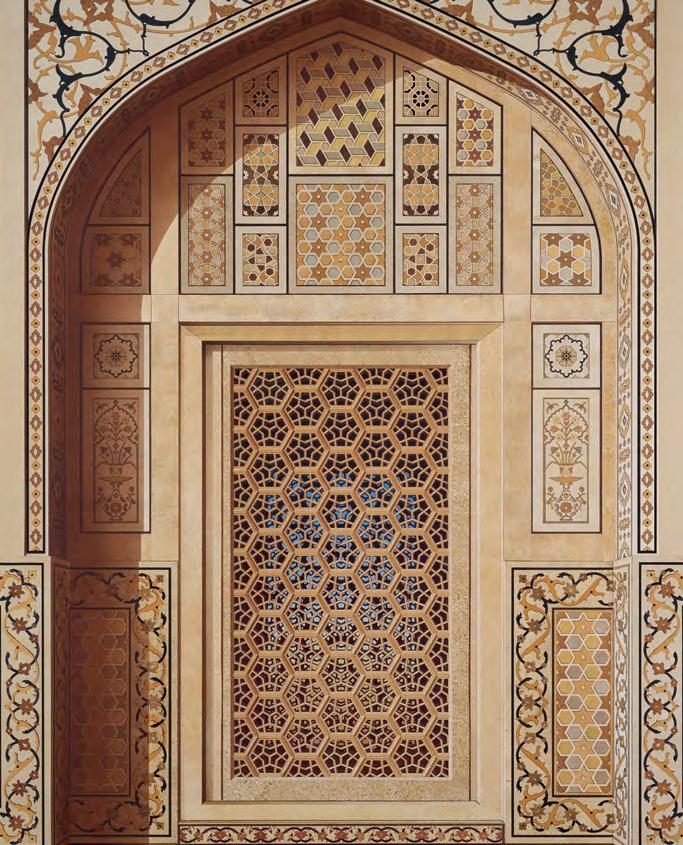

The work engages with the mystical and meditative qualities of this ancient structure, inviting viewers to contemplate impermanence, the nature of existence, and the interconnectedness of all things. Blending, yet contrasting beautifully with the former two intricate works, is a stunning bold composition in blue by US-based Emirati artist, Ebtisam Abdulaziz, that focuses on the role of colour in invoking feelings of tranquillity, depth, and infinity. Associated with the natural world's most prevalent colour (the sky and the sea), Ebtisam plays with shade and intensity with the same artistry as Vasarely, yet injects an added layer of symbolism. Another extraordinary work, this time by British artist Ben Johnson, encapsulates in its magnificent scale and stunning realism - a coup de force of hyper-realism yet with greater depth and homage to the iconic building it depicts than what we associate with hyper-realism. Known for his architectural paintings and his love of geometry and harmony, Johnson’s I'timad ud Daulah - Jaali brings to life the smallest detail, drawing in the viewer as if by 'virtual reality'. To view the threedimensionality of the STUPA 'skyscraper' against the twodimensional representation of a detail from the exterior wall of the Mughal emperor Jahangir’s grand-vizier I'timad ud Daulah’s (d. 1622) tomb, is a unique privilege which enhances the appreciation of both works.

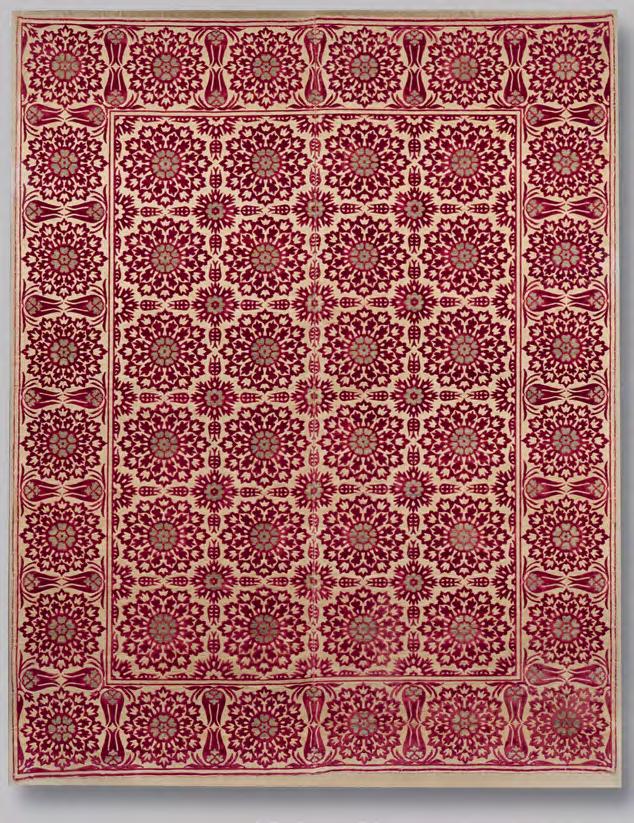

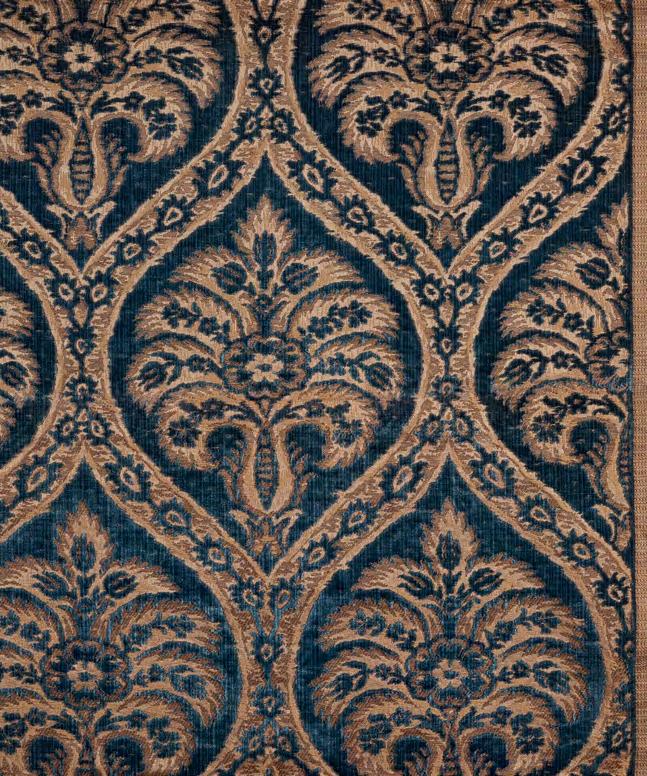

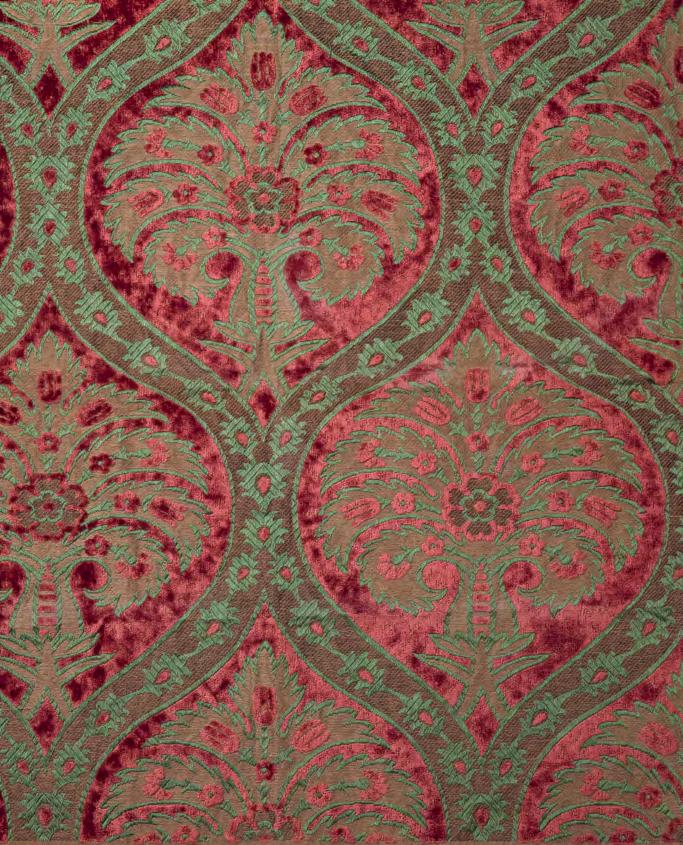

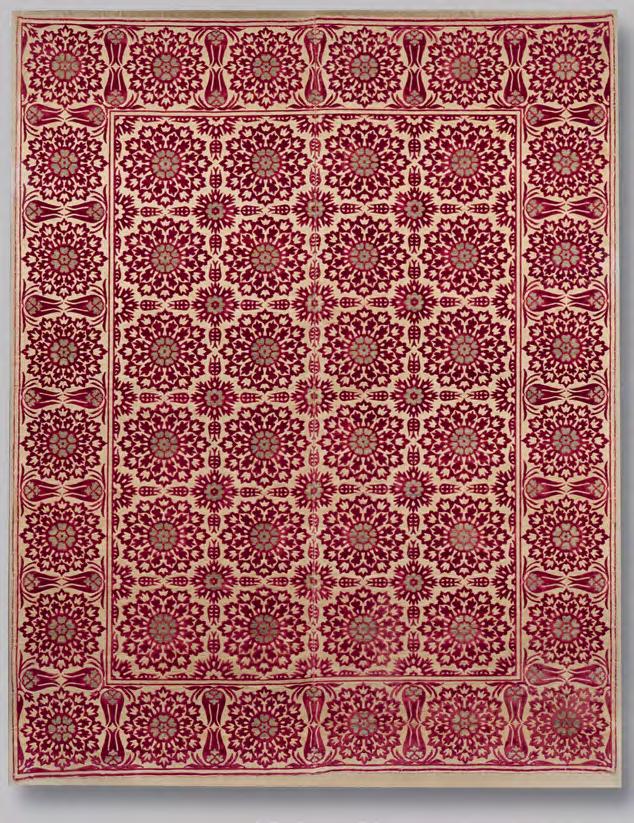

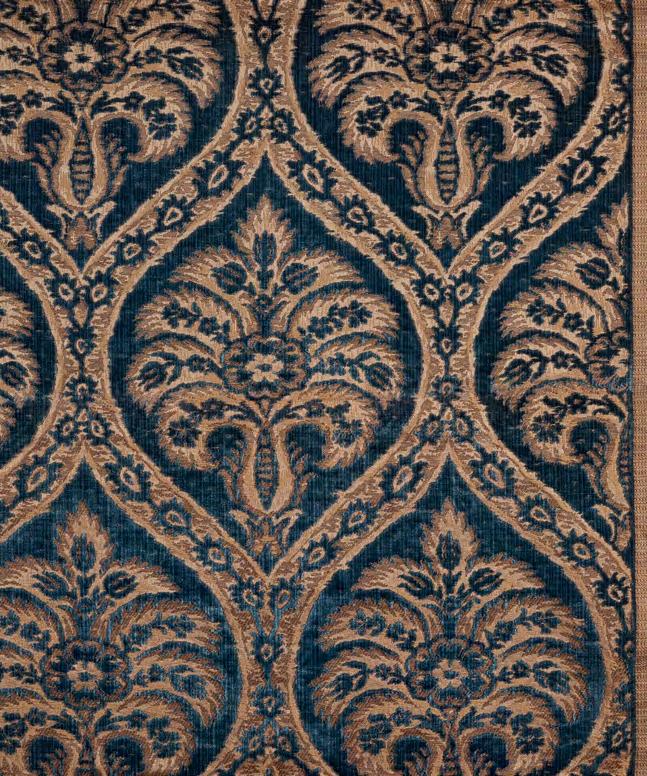

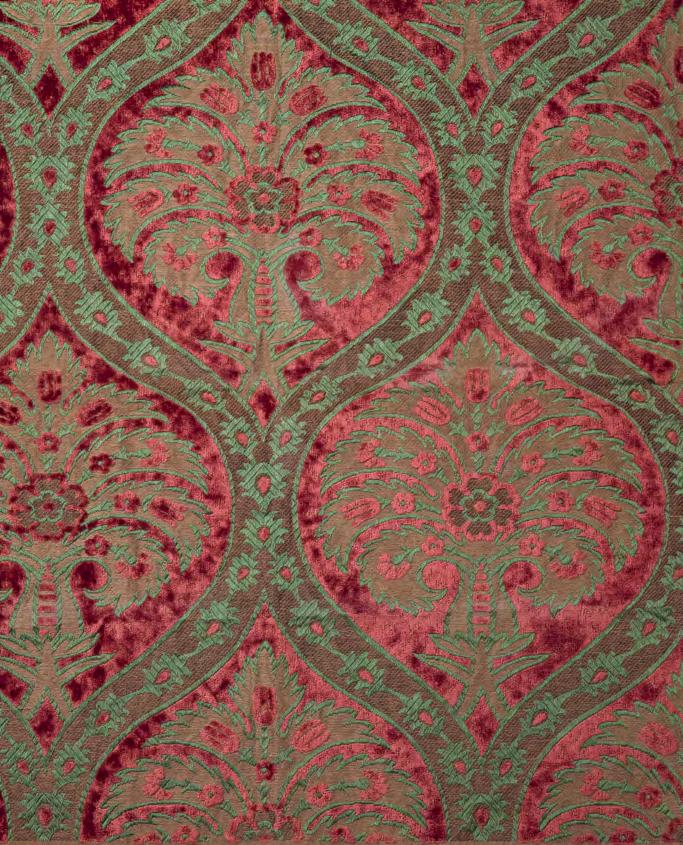

4

Kent Antiques encourages the juxtaposition of the classical and the contemporary as the discerning way to collect and to live with artefacts. Among the classical art works specially selected for their dialogue and harmony with the contemporary works, there is a stunning Iznik pottery hexagonal blue and white tile, previously acquired from the collection of Baron Alphonse Delort de Gléon (1843-1899). An extremely fine 17th century Ottoman voided silk velvet panel with gold and silver thread, from the famous Appleby collection, has a strikingly powerful design remarkable for its geometric symmetry and stylized tulips. A rare and important panel of three Iznik tiles produced for the imperial chamber of Sultan Murad III (1574-1595), with an impeccable three-generation provenance (from the collection of Dr. Jules Froment (1878-1946) is a brilliant example of combining elements of symmetrical design and stylized nature.

The dissection of time-lines is often arbitrary, and appreciating artworks for relationships, stories and shared symbols rather than just periods is far more rewarding. Our world is composed of shared atoms, shared experiences and shared historic evolutions. What better celebration of these commonalities than to observe the journey of humanity in a holistic and over-arching way?

Roxane Zand

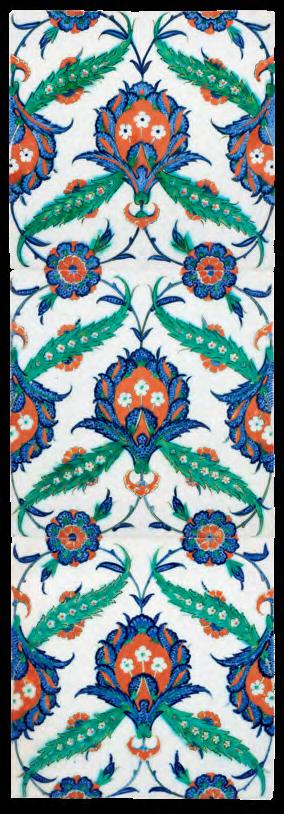

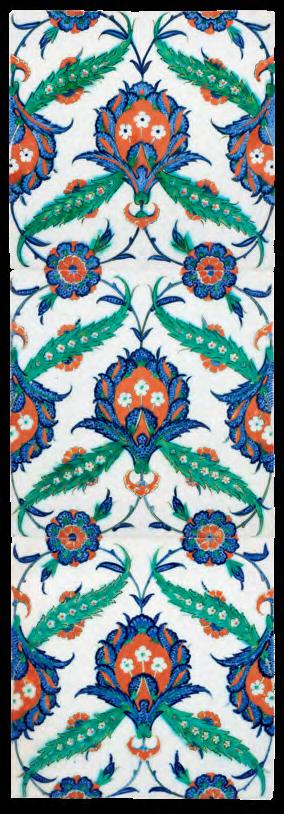

1 RARE AND IMPORTANT PANEL OF THREE IZNIK TILES PRODUCED FOR THE IMPERIAL CHAMBER OF SULTAN MURAD III (R. 1574-95)

Ottoman Empire

Circa 1575

Attributable to ‘Master

Mehmed of Iznik’

Dimensions: (Each Tile)

25 x 25 cm.

Panel of three Iznik tiles, painted under transparent glaze in coral red, cobalt blue and green, each finely decorated with a central composite hatayi blossom and two saz leaves emerging from their base, outlined in black, on a brilliant white background.

The present Iznik tiles are identical to those used for decorating the walls of the imperial chamber of Sultan Murad III (r. 1574-95) [Sultan III. Murad Sofası] in the Topkapı Palace, Istanbul. Please see, Ara Altun & Belgin Arlı, Tiles – Treasures of Anatolian Soil – Ottoman Period, Kale Group Cultural Publications, Istanbul, 2008, pp. 105108. This chamber, which constitutes the oldest structure preserved today within the palace, was built in 1578 by the famous Ottoman court architect Sinan on the site of the former chamber of Sultan Süleyman the Magnificent, which was previously damaged by fire.

The tiles from the privy chamber of Sultan Murad III are especially important because the name of the tile master and year of their production are known. The master’s name Mehmed is recorded in an imperial decree, dated 1575, when tiles were ordered by Sultan Murad III from Iznik (Ara Altun & Belgin Arlı, ibid, p. 107).

We find Iznik tiles featuring the same design in museum collections around the world. Among these the tile panel in the Gulbenkian Museum (Inv. No. 1663) can be mentioned. Please see, Maria d’Orey Capucho Queiroz Ribeiro, Iznik Pottery and Tiles in the Calouste Gulbenkian Museum. Lisbon, 2009, p. 118. Also see, In Harmony –The Norma Jean Calderwood Collection of Islamic Art, Harvard Art Museums, 2013, p. 197, No, 43.

The saz leaf, seen on our tiles, is an important motif frequently used by the artists in the Ottoman court atelier. The first representative of the saz style at the Ottoman palace was Şahkulu, an artist brought from Tabriz by Sultan Selim I (r. 1512-1520). This style was a departure from the classical miniature painting, characterised by pictures drawn with a brush in black ink, featuring long pointed leaves, giving birth to the term ‘saz leaf’. Paintings in the saz style may remind a thick forest with intertwined curved leaves and khatai blossoms. In fact, the word saz, used to mean ‘forest’ in the Dede Korkut stories, that

dates back to the 10th or 11th century. For further information please see, Motif from the Sadberk Hanım Museum Collection (written by Turgut Saner, Şebnem Eryavuz and Hülya Bilgi), Sadberk Hanım Museum, Istanbul, 2020, p. 106.

There are many hypothesis about the origin of the khatai motif. One of these is that this motif was created by an artist who travelled from Herat to China, or that it was inspired by the lotus, but all agree that the name derives from Hitay, a region of China. For further information please see, Motif from the Sadberk Hanım Museum Collection (written by Turgut Saner, Şebnem Eryavuz and Hülya Bilgi), Sadberk Hanım Museum, Istanbul, 2020, p. 104.

The present tiles are rare and important examples of the art of Ottoman Iznik pottery with their perfect design, vibrant colours and brilliant firing.

Provenance

Dr. Jules Froment (1878-1946) Collection by repute.

Then by descent, Professor Roger Froment (1907-1984) Collection Ex-Odile Froment Benoit Collection

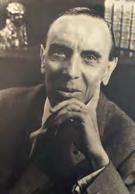

Dr. Jules Froment (1878-1946)

The first collector of the Froment family, who first owned the present three Iznik tiles, was Jules Froment, a famous French neurologist. During World War I he was stationed at Rennes, where he treated soldiers. He worked as a professor in Lyon, and he published his medical research on neurology. He died in 1946.

Professor Roger Froment (1907-1984)

Professor Roger Froment inherited the present tiles from his father’s collection. Roger, like his father, became a doctor by profession. He developed a deep interest in Islamic art in the early stages of his career. First, he was interested in Persian carpets. His interest evolved and he became fascinated by the beauty of Islamic manuscripts, ceramics, and textiles. These three fields constituted the heart of his collection. Over the years, he improved a good taste, developed firm knowledge and a good eye for fine Islamic art works. His collection expended as he followed the advice of prominent Islamic art dealers such as Jean Soustiel.

Roger managed to pass down his love and passion for Islamic art to his daughter Odile and his son-in-law. After Roger’s death, when they inherited his works of art, they cherished this collection with a similar enthusiasm. The present panel of three Iznik tiles is coming from this family collection which was lovingly collected, looked after and enjoyed by successive generations.

8

Professor Roger Froment (1907-1984)

Dr. Jules Froment (1878-1946)

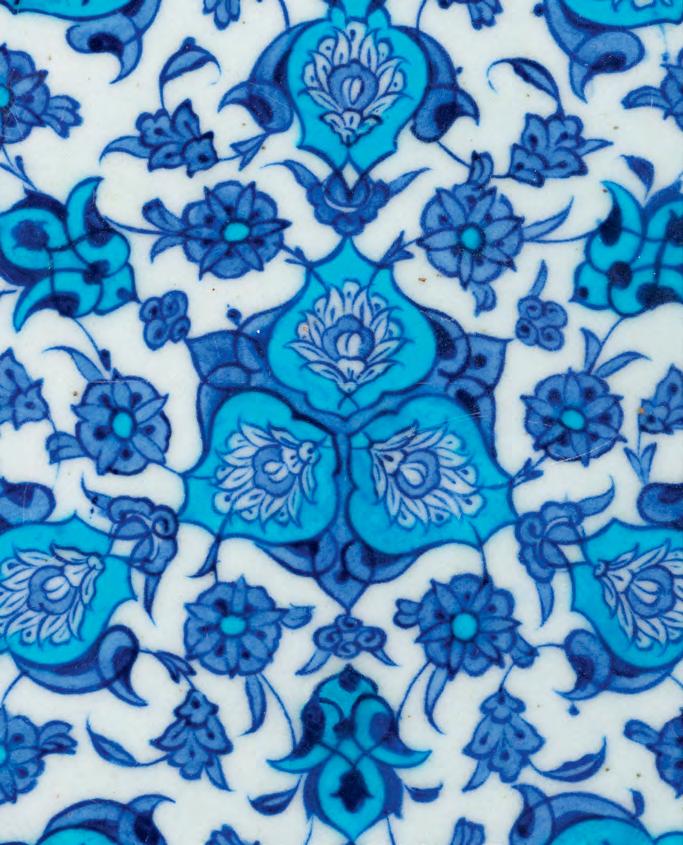

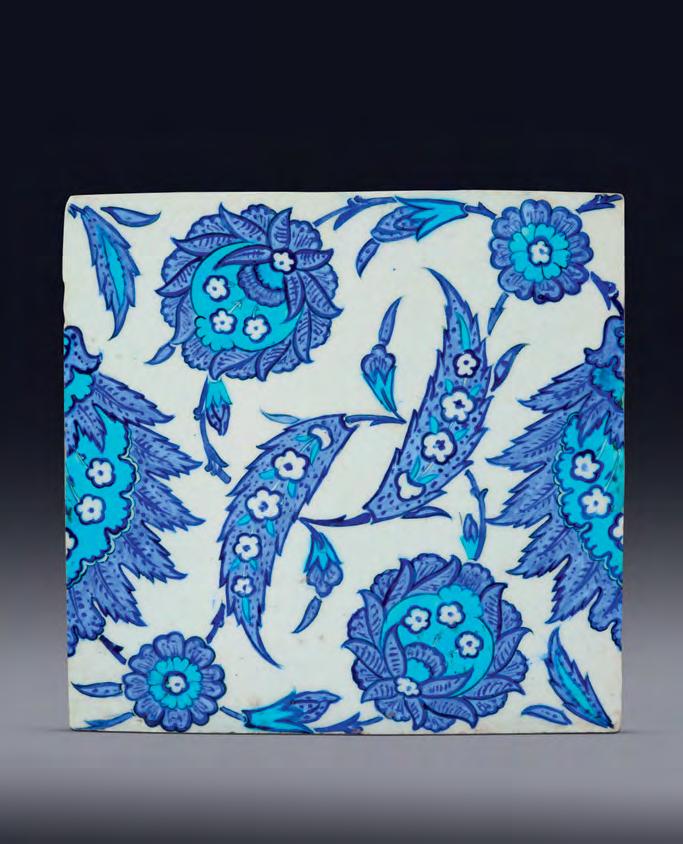

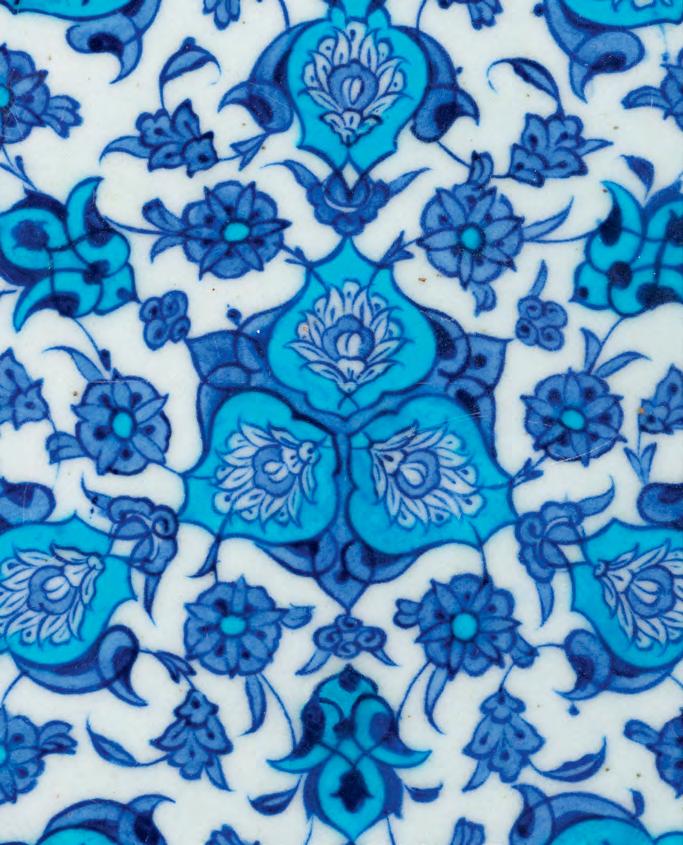

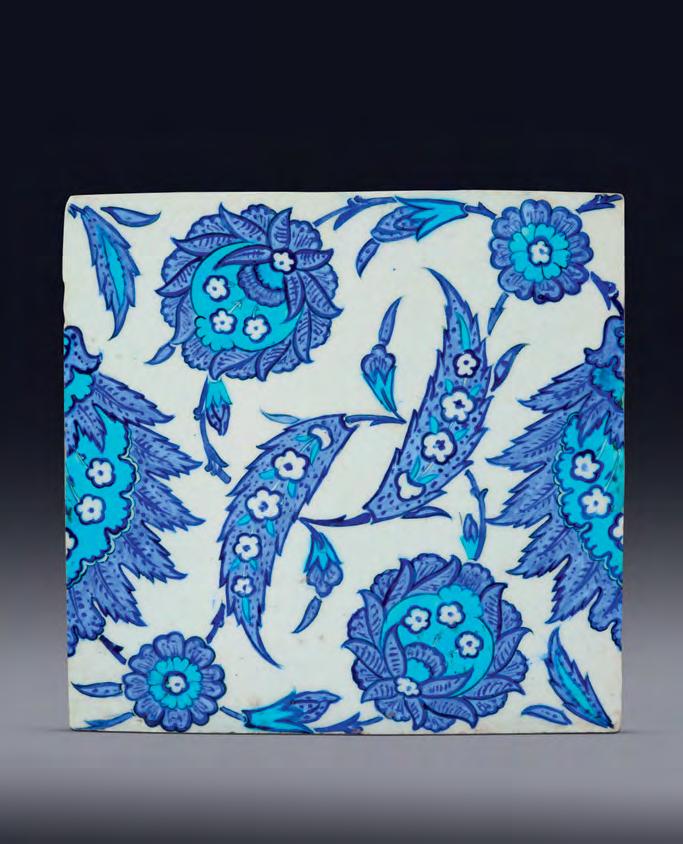

2 IMPORTANT IZNIK BLUE AND WHITE POTTERY TILE

Ottoman Empire

Circa 1545-1550

Dimension: 26 x 26 cm.

Fritware, painted under clear glaze with cobalt blue and turquoise; the composition consists of intertwined saz leaves and khatai blossoms, each decorated with white flower heads.

The combination of cobalt blue and turquoise seen on the present tile can also be found on the famous Sünnet Odası (Circumcision Room) tiles in the Topkapi Palace Museum, Istanbul. Especially the saz leaves and khatai blossoms on the side panels of the Circumcision Room tiles feature similar use of cobalt blue and turquoise. Please see, Ahmet Ertuğ and Walter Denny, Gardens of Paradise – 16th Century Turkish Ceramic Tile Production, p. 81.

An important Iznik ‘Damascus style’ dish with similar cobalt blue and turquoise is published in our gallery’s 2017 catalogue Kent Antiques Islamic and Indian Art – Works of Art from the Islamic World and Orientalist Paintings, London, 2017, No. 18.

Comparable Iznik dishes and footed bowls similarly decorated with khatai blossoms in cobalt blue and turquoise, produced between 1545-1550, are published in Nurhan Atasoy & Julian Raby’s Iznik – The Pottery of Ottoman Turkey, Alexandria Press, London, 1994, pl. 352 and pl. 358.

Three Iznik tiles, identical to the present tile, are in the Louvre Museum (Inv. No. AD 5971/1, AD 5971/3, AD 5971/4), Paris. Please see, https://collections.louvre.fr/en/ark:/53355/cl010332784

A counterpart of the present tile is published in Couleurs d'Orient - Arts et arts de vivre dans l'Empire Ottoman, Catalogue d'exposition, Villa Empain, Fondation Boghossian, Bruxelles, 18 November 2010 - 27 February 2011, p. 47.

A similar tile decorated with saz leaves and flower heads is found in the Cincinnati Museum. Counterparts of the Cincinnati tile are found in the Rüstem Pasha Mosque in Istanbul. See, Ara Altun & Belgin Arlı’s Tiles – Treasures of Anatolian Soil – Ottoman Period, Kale Group Cultural Publications, Istanbul, 2008, p. 183, fig. 204.

This is a rare tile displaying wonderful precision in outlining and colours which is a result of masterful brushwork and excellent firing.

Provenance

A. Jacob Collection (1942-1988), Paris.

10

3 IMPORTANT IZNIK POTTERY HEXAGONAL BLUE & WHITE TILE

Painted under clear glaze with cobalt blue and turquoise; the composition consists of intertwined blossoms and flower heads. This tile belongs to a small group of Izniks produced around 1530 which are closely related to the famous Circumcision Room (Sünnet Odasi) tiles in the Topkapi Palace, Istanbul. Our tile bear aesthetic and stylistic similarities with the hexagonal blue and white Circumcision Room tiles. Please see, Ahmet Ertuğ and Gardens of Paradise – 16th Century Turkish Ceramic Tile Production, Ertuğ & Kocabıyık,

The present example presents a striking resemblance to a group of eight identical tiles in the Louvre Museum (inv. no. OA 7456/14, OA 7456/16, OA 7456/19, OA 7456/21, OA 7456/22, OA 7456/24, OA 7456/27, OA 7456/29), all previously in the collection of Baronne Alphonse Delort de Gléon (1843-1899). The name ‘Gouron 16’ is inscribed on the reverse of the present tile, in reference to Marcel Gouron-Boisvert, an architect involved in the designing of the Delort de Gléon villa in Cairo where Iznik tiles were used to decorate the interiors. Please see, Mercedes Volait, Antique Dealing and Creative Reuse in Cairo and Damascus 1850-1890, Brill, 2021, p.157.

becoming a dominant feature in Karahanid, Ghaznavid, Fatimid, Abbasid, Andalusian Umayyad and Mamluk art and above all becoming popular in Anatolia, also known as Rum, from which the name rumi derives. Some outstanding examples of rumi motifs are found in Anatolian Seljuk stone carving and woodwork usually combined with lotus and palmette motifs.

An identical Iznik tile is in the Ashmolean Museum (E.A. 1978.1536). Please see the link: http://jameelcentre. ashmolean.org/collection/6/653/834

Another identical example is in the Harvard Art Museums, please see the link: https://harvardartmuseums.org/collections/ object/216298?q=1960.102

The last of the recorded comparable Iznik tiles is in the Ömer M. Koç Collection. Please see, Hülya Bilgi, AteşinOyunu–SadberkHanımMüzesiveÖmerM.Koç KoleksiyonlarındanİznikÇiniveSeramikleri, Vehbi Koç Vakfı, İstanbul, 2009, p. 96, cat. no. 29.

Provenance

Ex-Private French Collection, Purchased from Galerie Moreau-Gobard, between 1960-1980.

The rumi motif has a special place in the history of Ottoman decorative elements. This motif is called rumi by the Ottomans, islimi by the Persianate dynasties and arabesque by the Europeans. There are divergent views on the origin of the motif, some regarding it floral in origin, others as zoomorphic, such as the theory that it derives from the wings of birds or mythical animals in central Asian art. The motif developed in Samarra in the 9th century and spread to the Islamic lands,

By repute acquired from the collection of Baronne Alphonse Delort de Gléon (1843-1899). The name ‘Gouron 16’ is inscribed on the reverse of the present tile, in reference to Marcel Gouron-Boisvert, an architect involved in the designing of the Delort de Gléon villa in Cairo where Iznik tiles were used to decorate the interiors. Please see, Mercedes Volait, Antique Dealing and Creative Reuse in Cairo and Damascus 1850-1890, Brill, 2021, p. 157.

Marcel Gouron-Boisvert

French architect Marcel Gouron-Boisvert was born in 1840. He graduated from the École des Beaux-Arts de Paris. He went to Egypt in 1872 to work on the construction of the equestrian statue of Muhammad Ali Pasha in Alexandria. He worked on the Zogheb Palace in Alexandria. Marcel also worked -together with his friend Charles Guimbard- on the designing of Saint-Maurice’s House in Cairo. Iznik tiles, like the present one, were reused in these interiors to decorate door frames and surroundings. See for example the photograph in ibid, p. 162, Fig. 123.

12

Portrait of Baron Delort de Gléon, 1883 Gunnar Berndtson (1854-1895),

A corner of architect Ambroise Baudry’s Studio at his house in Cairo, undated [After 1876], After Mercedes Volait, Antiques DealingandCreativeReuseinCairoand Damascus 1850-1890, Brill, 2021, p. 162.

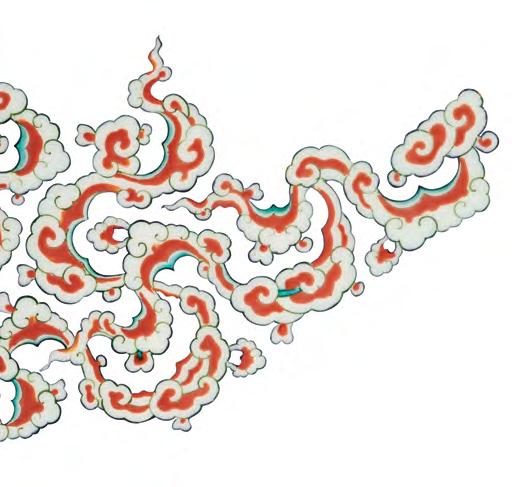

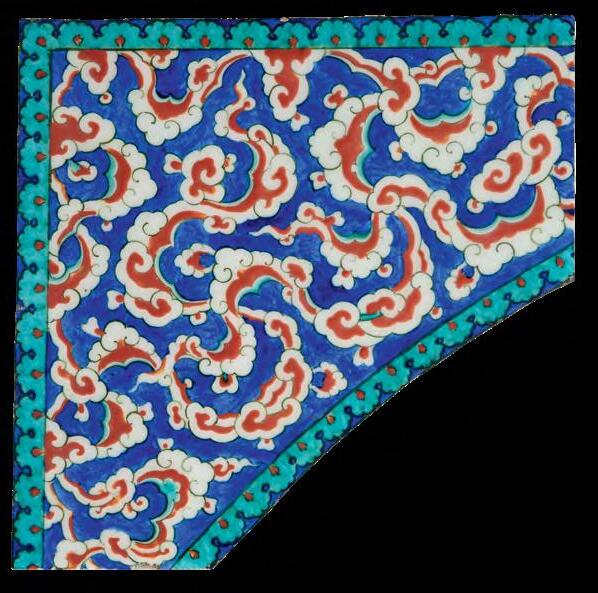

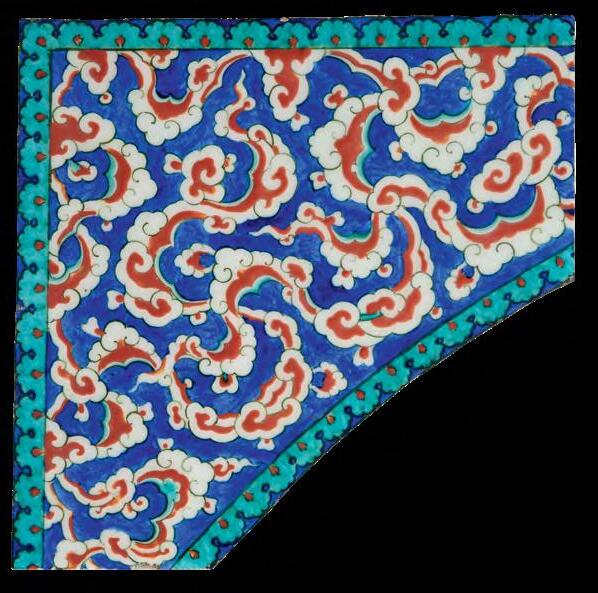

4 LARGE IZNIK POLYCHROME POTTERY TILE SPANDREL

Ottoman Empire

Circa 1580

Dimensions: 29.9 x 30.5 cm.

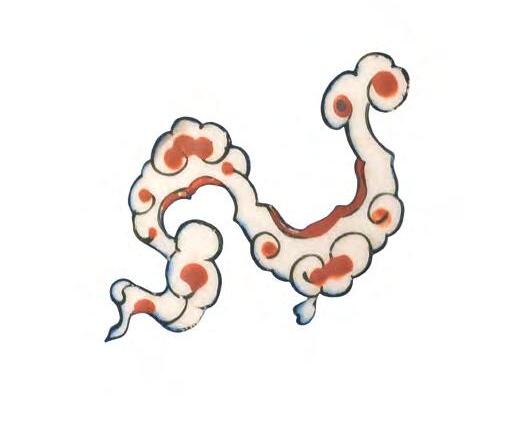

The cobalt-blue ground decorated under the glaze with coral red and white Chinese cloud bands, within turquoise and cobalt-blue lobed borders, intact.

Decorated spandrels were in use in Turkish interior decoration from as early as the Seljuk period, for example those from the Kubadabad Palace in Beyşehir which are in stucco and decorated with peacocks. Iznik tiles later became a popular method of decorating interiors. Iznik tile spandrels exist in several museum collections in Istanbul, New York, Copenhagen, Paris and Kuwait.

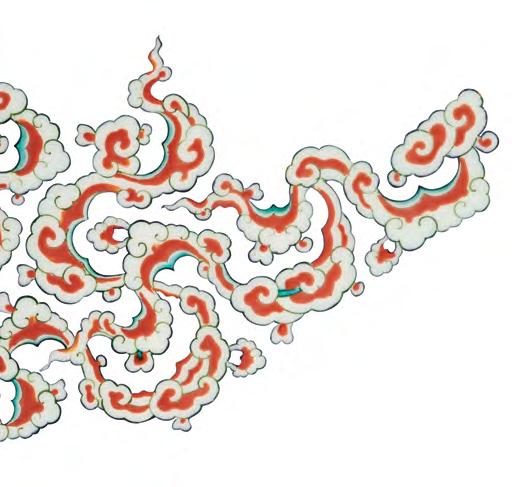

The Chinese cloud was one of the main motifs from the Ottoman decorative repertoire and its was frequently used by the court workshop during the 16th century.

A tile panel decorated with grapes and spring flowers on the east and west walls of the Takkeci Ibrahim Aga Mosque in Istanbul features corners with similar aesthetic. These corners are decorated with white Chinese cloud on a coral red ground. Please see Belgin Demirsar Arlı & Ara Altun’s Tiles: Treasures of Anatolian Soil – Ottoman Period, Kale Group, Istanbul, 2008, p. 264, Figs. 301.

The present tile is important both for its size and its jewel-like colours.

Provenance

Private UK Collection

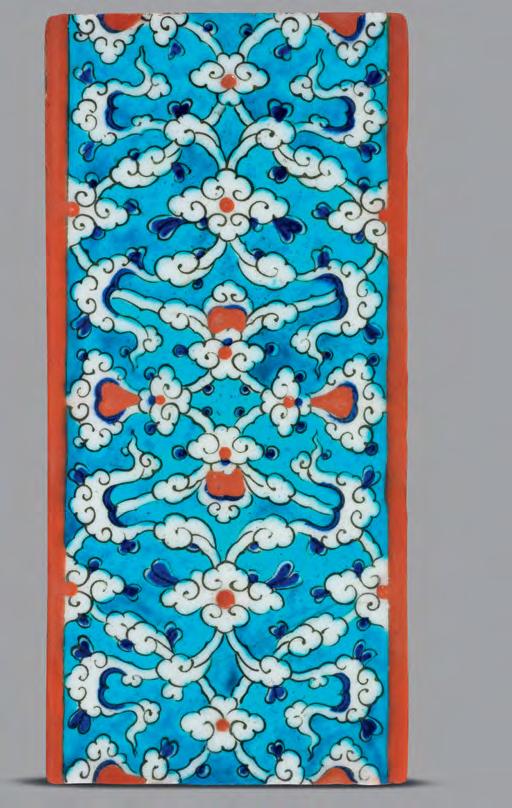

Ottoman Empire

Second Half of the 16th Century

Dimensions: 26 x 12.5 cm.

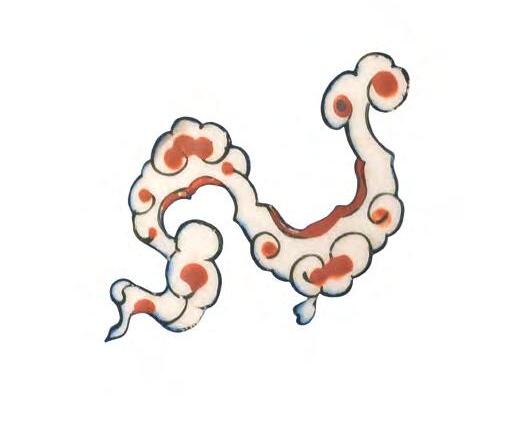

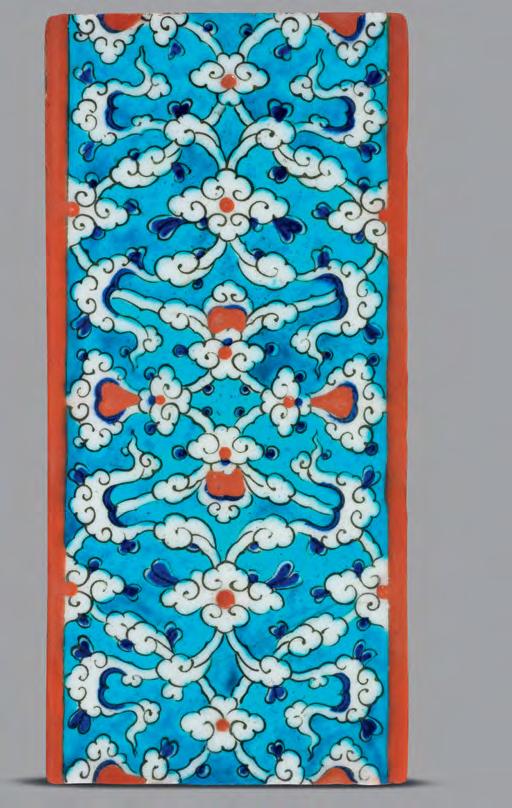

IZNIK POLYCHROME POTTERY BORDER TILE DECORATED WITH CHINESE CLOUDS

Painted under clear glaze with coral red, blue, turquoise, decorated with intertwined white Chinese clouds with coral red dots and bands on both sides. Loops of the Chinese clouds are highlighted with coral red.

The Chinese cloud or ‘stylised cloud band motif’ is one of the most favoured motifs of the Ottoman decorative repertoire; frequently used by the artist members of the palace workshop (nakkaşhâne) in the 16th century. Chinese clouds were widely used to decorate Ottoman ceramics, textiles, manuscripts, carpets, glass and woodwork. In Chinese art, this motif is primarily associated with the strength of the dragon and sometimes represents the smoke coming out of its mouth. However, in Ottoman art, it was generally interpreted as a stylized white cloud in the blue sky.

İnci Ayan Birol, “Tezhip”, TürkiyeDiyanetVakfıİslam Ansiklopedisi, vol. 41, 2012, pp. 65-68. In the present example, for instance, this appears to be the reason why the potter used blue for the background and white for the clouds.

The cloud band motifs were much favoured also by Timurid and Akkoyunlu artists. Diverse cloud motifs found in miniature paintings of the Herat and Shiraz schools, on ceramics, metalware and carpets appear to have been adopted and reinterpreted by Ottoman artists. For further information please see, Motif from the Sadberk Hanım Museum Collection (written by Turgut Saner, Şebnem Eryavuz and Hülya Bilgi), Sadberk Hanım Museum, Istanbul, 2020, p. 118.

Comparable border tiles decorated with white Chinese clouds, similarly with red in loops, can be seen in situ in the Süleymaniye Mosque, Istanbul. Please see, Ara Altun & Belgin Arlı’s Tiles – Treasures of Anatolian Soil – Ottoman Period, Kale Group Cultural Publications, Istanbul, 2008, p. 170. Iznik border tiles, decorated with similar Chinese clouds can also be found in the Louvre Museum, Paris (Inv. No. UCAD 5967/22 and UCAD 5967/28). Please see the links, https://collections.louvre.fr/en/ark:/53355/cl010332711 and https://collections.louvre.fr/en/ark:/53355/ cl010332717.

Provenance

Ex-Private French Collection. Ex-Odile Froment Benoit Collection.

16 5

Photograph of the present tile taken in 1994 with other pieces from the Odile Froment Benoit Collection.

6

RARE AND FINE IZNIK POLYCHROME POTTERY BORDER TILE

Ottoman Empire

Circa 1580

Dimensions: 26.5 x 6.5 cm.

Painted under clear glaze with coral red, blue, turquoise and green. Intertwined white Chinese clouds are decorated with coral red dots and outlining. Two loops of two Chinese clouds at both ends of the tile are highlighted with green. The design is bordered by turquoise lines running on both sides.

The Chinese cloud is one of the most favoured motifs of the Ottoman decorative repertoire; frequently used by the artist members of the palace workshop in the 16th century. Chinese clouds were widely used to decorate Ottoman ceramics, textiles, manuscripts, carpets, glass and woodwork. In Chinese art, this motif is primarily associated with the strength of the dragon and represents the smoke coming out of its mouth. However, in Ottoman art, it was generally interpreted as a stylized cloud in the sky. İnci Ayan Birol, “Tezhip”, Türkiye Diyanet Vakfı İslamAnsiklopedisi, vol. 41, 2012, pp. 65-68. In the present example, for instance, this appears to be the reason why the potter used blue for

Ottoman Empire

Circa 1575-1580

Diameter: 36 cm.

A LARGE IZNIK DISH WITH FLORAL DECORATION FROM THE REIGN OF SULTAN MURAD III

IZNIK POLYCHROME POTTERY DISH DECORATED WITH RED ROSES AND BLUE SAZ LEAVES

Fritware, decorated in the ‘saz leaf and rosette’ style in coral red, blue, green, black, with a central rosette surrounded by symmetrically organized blue tulips, red roses and blue saz leaves. The rim decorated with stylized wave motifs.

Besides its exceptional size, the present dish features a very rare design which gathers different floral elements used in the Ottoman court workshop in the 16th century. Iznik dishes uniting such a variety of motifs, including tulips, roses, saz leaves surrounding a central palmette, are rare.

In the 16th century flowers gained an increasingly important role in the Ottoman decorative repertoire. Besides being a constant part of daily life, grown in gardens everywhere, from palaces to humble homes, flowers had a determining place in the decoration of Iznik ceramics, Ottoman imperial silks and velvets, manuscript illumination, miniature painting, metalwork and woodwork. Among these, tulips, roses and saz leaves became especially predominant during and after the reign of Sultan Suleyman the Magnificent (r. 1520-1566). The head of the court studio, master Shah Kulu and his successor Kara Memi introduced an extraordinary variety to the single and combined use of flowers; particularly tulips, roses and saz leaves. The design of the present dish is a perfect example of the mature phase of this evolution, under the reign of Sultan Murad III (r. 1574-1595), which displays the ideal balance and harmony created between these different elements.

A comparable Iznik dish with floral decoration in the Ex-Adda Collection (Racham Cat. 108) is published in Julian Raby & Nurhan Atasoy’s Iznik: The Pottery of Ottoman Turkey, Alexandria Press, London, 1989, pl. 482. A second comparable Iznik dish with blue saz leaves and floral decoration is in the Gulbenkian Museum, Lizbon. See, Julian Raby & Nurhan Atasoy, Iznik: The Pottery of Ottoman Turkey, Alexandria Press, London, 1989, pl. 697.

Provenance

Private Italian Collection

7 20

Ottoman Empire

Second Half of the 16th Century

Diameter: 30 cm.

IZNIK POLYCHROME POTTERY DISH DECORATED WITH BUNCHES OF SPRING FLOWERS

AND BLUE

TULIPS

Fritware, underglaze painted in cobalt blue, coral red, green, black. Decorated with bunches of red and blue spring flowers, the rim with blue double-tulip motifs and flower heads.

In the Ottoman period flowers, decorating the present dish, were a constant part of daily life, grown in gardens everywhere, from palaces to humble homes. Flowers were blessed reminders of the gardens of heaven. Foreign travellers and ambassadors who visited the empire frequently remarked about this love of flowers. The 17th century Ottoman writer and traveller Evliya Çelebi describes how vases of roses, tulips, hyacinths, narcissi and lilies were placed between the rows of worshippers in the Eski Mosque and the Üç Şerefeli Mosque in Edirne, and how their scent filled the prayer halls. As depicted in the present dish, vases of flowers adorned niches in the walls, dining trays and rows of vases were placed around rooms and pools. For further information please see, Motif from the Sadberk Hanım Museum Collection (written by Turgut Saner, Şebnem Eryavuz and Hülya Bilgi), Sadberk Hanım Museum, Istanbul, 2020, pp. 86-90.

The tulip, repeatedly used in rim of our dish, has a symbolic meaning in Ottoman art. The letters of the word tulip (Lâle [ هللا]) in Turkish and Persian are the same letters used for writing the word Allah [ الله] (God). These two words have the same numerological value in the abjad system (a decimal alphabetic numeral system in which the twenty-eight letters of the Arabic alphabet are assigned numerical values). Tulip is one of the leading decorative elements in Ottoman art; frequently used together with roses, hyacinths, saz leaves. It is also used with khatai blossoms as can be seen in the present tile. Tulip also played a role in imagery

in Ottoman poetry. In many poems, tulip leaves are likened to the cheeks of the beloved. The word lāleh-khad (lâle-had), often used in Ottoman poetry, means ‘tulip-cheeked’. Tulips were among the most favoured motifs used in the Ottoman court workshops in the 16th century. The name ‘tulip’ is thought to have derived from the Turkish word tülbend (from the Persian word دنبلد [dulband]) -meaning ‘large cotton band which is used in the making of turban or headgear’- because of the fancied resemblance of the flower to a turban.

A comparable Iznik dish decorated with almost identical bunches of spring flowers, is in the Louvre Museum (Inv. No. 7880/70), Paris. Please see, Julian Raby & Nurhan Atasoy, Iznik: The Pottery of Ottoman Turkey, Alexandria Press, London, 1989, p. 234, pl 425. The present dish is a rare and important example reflecting both the high quality and awe-inspiring creativity achieved by of Iznik potters.

Provenance

Ex-Dr. Joseph Chompret Collection. (The present Iznik dish is recorded in Dr. Chompret’s personal collection register, in page 47.)

Dr. Chompret was born in Paris, in 1869. The son of a country doctor, he chose a medical career and obtained his medical degree in 1893. He specialized in stomatology, and invented the ‘syndesmotome’. For many years he was head of the Saint-Louis hospital in Paris. He was a great collector. He was interested in old cutlery, pewter, ivory and medieval enamels. However he was very enthusiastic about ceramics and his collection of French earthenware, Italian majolica and Middle Eastern ceramics is renowned. Doctor Chompret was also a great friend of museums. The Ceramic Museum of Sèvres received 280 pieces, and the Musée des Arts Décoratifs 339 pieces from Dr Chompret’s collection. Between 1931 and 1956 he was the president of the Friends of Sèvres (Amis de Sèvres) association. He died in 1956.

8 22

Ottoman Empire

Second Half of the 16th Century

Diameter: 26.2 cm.

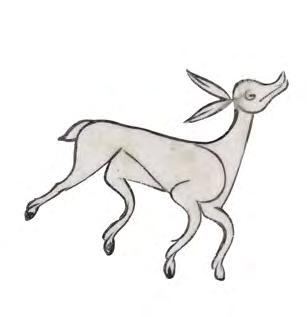

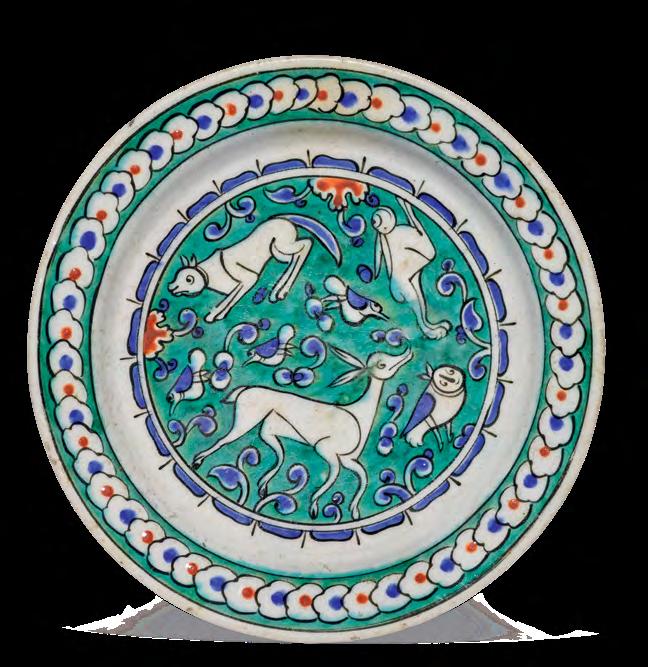

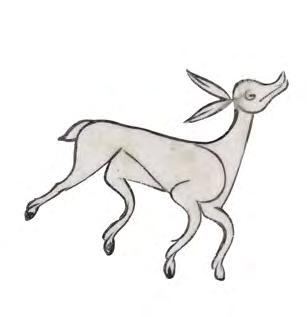

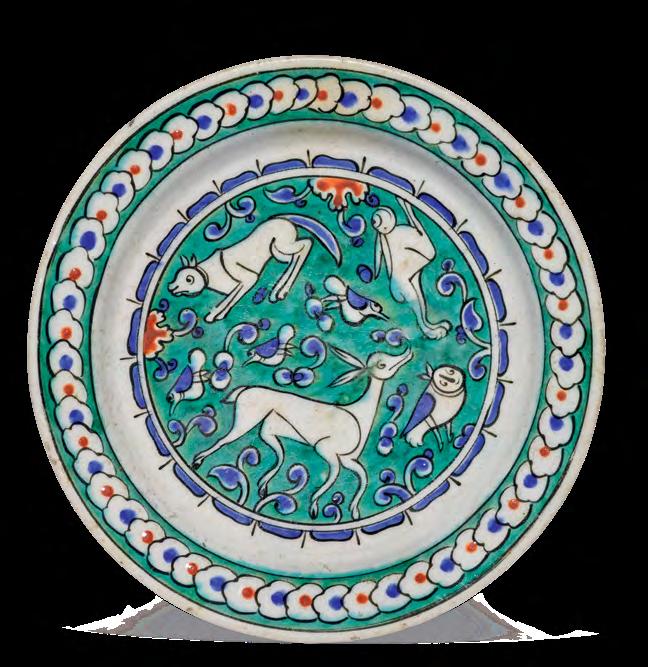

IZNIK POTTERY DISH DECORATED WITH AN OWL, A DEER, A DOG, A HARE AND THREE BIRDS

Of shallow rounded form with everted rim, painted in cobalt blue, green and red with black outlines, the circular central medallion decorated with a deer, an owl, a hare, a dog and three birds interspersed with foliate motifs, the medallion encircled by a frieze of stylised petals, the rim with a frieze of alternating blue and red rosettes on a green band, the reverse with alternating stylised foliage motifs. The bold effect of the bright green ground is heightened by the potter’s decision to leave the cavetto blank, providing breathing room for the composition.

Depiction of wild animals is part of an old iconographic tradition in Anatolia and the present aesthetic can be stretched back to figural Seljuk art. In Ottoman art some of the earliest depictions of animals are found on Iznik ceramics in the 1520s and 1530s. Probably the most famous examples are those on the Sünnet Odası (Circumcision Hall) tiles, in the Topkapi Palace, Istanbul.

Nurhan Atasoy and Julian Raby in Iznik: The Pottery of Ottoman Turkey state that “the animals of the ‘greenground group’ were a collection of the exotic and the mythical. There were coursing dogs, deer, hares, ducks, monkeys, lions, horned snakes, simurghs and confronted harpies. The style has affinities with the ‘animal chase’ which was a favoured motif in Seljuk metalwork. The mixture of real and fantastic animals was, however, characteristic of the Balkan ‘teratological’ style, and although there are few precisely comparable objects, it was probably Balkan precious metalwork which inspired the Iznik potters.” For further discussion and the illustration of a closely related Ottoman silver tankard which shows dogs chasing hares please see, Nurhan Atasoy and Julian Raby, Iznik: The Pottery of Ottoman Turkey, Thames and Hudson, London, 1989, p. 276, Fig. 617.

A closely related dish is in the Musée National de la Renaissance, Ecouen (inv. no. ECL 8362), presenting an almost identical central medallion and border on a turquoise ground. Please see, Frédéric Hitzel et al. Iznik – L’Aventure d’une Collection, Musee National de la Renaissance – Chateau d’Ecouen, Paris, 2005, p. 283. A similar dish in the Benaki Museum (inv. no. 11148) follows an analogous iconographical structure with animals depicted in the medallion and a green ground. Please see, John Carswell, Mina Moraitou and Melanie Gibson’s Iznik Ceramics at the Benaki Museum, Benaki Museum - Gingko, London, 2023, p. 121.

An Iznik tankard, similarly decorated with animals on a green ground, was sold at Christie’s London, for £157,250. Please see, Art of the Islamic and Indian World sale, 6 October 2011, Lot. 319. Looking at the group as a whole, one cannot help but wonder whether not just those noted above, but indeed the majority of the group were done by the same inventive artist, with the slight differences accounted for by a development in his style over time. The small number of surviving pieces is such that it is certainly possible that these may be the work of a single individual.

Provenance

Léon-Edmond-Marie Bachelier (1862-1947). To his granddaughter Marie Lucy Giraud (b.1910), thence by descent.

Collection Guillaume Ephis (Collection Label on the Reverse).

24

9

10

FINE AND IMPORTANT IZNIK POTTERY DISH DECORATED WITH CARNATIONS, TULIPS AND

SPRING BLOSSOMS

Ottoman Empire

Second half of the 16th Century

Diameter: 32 cm.

Underglaze painted in dark lavender blue, coral red, green, black. Decorated with carnations stemming from a miniature vase, surrounded by symmetrically arranged tulips and spring blossoms; the rim with stylized wave motifs. In the colour scheme of Iznik pottery, the dark lavender blue in the present dish is very rarely used.

The tulip has a symbolic meaning in Ottoman art. The letters of the word tulip (Lâle [ هللا]) in Turkish and Persian are the same letters used for writing the word Allah [ الله] (God). These two words have the same numerological value (66) in the abjad system (a decimal alphabetic numeral system in which the twenty-eight letters of the Arabic alphabet are assigned numerical values). Tulip is one of the leading decorative elements in Ottoman art; frequently used together with roses, hyacinths, saz leaves. It is also used with khatai blossoms as can be seen in the present dish. Tulip also played a role in imagery in Ottoman poetry. In many poems, tulip leaves are likened to the cheeks of the beloved. The word lāleh-khad (lâlehad), often used in Ottoman poetry, means ‘tulipcheeked’. Tulips were among the most favoured motifs used in the Ottoman court workshops in the 16th century. The name ‘tulip’ is thought to have derived from the Turkish word tülbend (from the Persian word دنبلد [dulband] -meaning ‘large cotton band which is used in the making of turban or headgear’- because of the fancied resemblance of the flower to a turban.

A similar Iznik dish in the Benaki Museum (inv. no. 11138) follows an analogous

iconographical structure with carnations stemming from a miniature vase. Please see, John Carswell, Mina Moraitou and Melanie Gibson’s Iznik Ceramics at the Benaki Museum, Benaki Museum - Gingko, London, 2023, p. 77. The present dish is a fine and important example of Iznik ceramic production, displaying a truly iconic aesthetic and presence with its vibrant colours and brilliant finish.

Provenance

Sir Christopher Cockerell (1910-1999), C. B. E., F. R. S., Acquired before 1962.

SIR CHRISTOPHER COCKERELL (1910-1999) CBE, FRS

Sir Christopher was born on 4 June 1910 in Cambridge, the son of Sir Sydney Cockerell, the dynamic Director of the Fitzwilliam Museum and Florence Kate Kingsford, known for her collection of illuminated manuscripts. Having read mechanical engineering at Cambridge University, Cockerell returned to research radio and electronics, later joining the Marconi Wireless Telegraph Company. At just twenty-seven he was made Technical Head of the Aircraft Research and Development Section. His next move in 1948 was to boat design and it was in December 1955 that he took out a patent, the first of 59, to cover what he described as “neither an aeroplane nor a boat nor a wheeled-land vehicle” – the hovercraft which is now used worldwide in over seventy countries. Although best remembered for the invention of the hovercraft, Sir Christopher did, in fact, have nearly a hundred patents to his name, earning him a place amongst the great British inventors and engineers of the twentieth century. Despite engineering being an allconsuming, innate part of his life, he was a man of many talents and interests which included a love for Antiquities as well as Ottoman ceramics.

26

Sir Christopher Cockerell (1910-1999)

11

IZNIK POLYCHROME POTTERY DISH DECORATED WITH TULIPS

AND SPRING

BLOSSOMS

Ottoman Empire

Second Half of the 16th Century

Diameter: 32 cm.

Fritware, underglaze painted in blue, coral red, green, black. Depicting tulips and spring blossoms on a red ground. The rim decorated with stylized wave motifs. The bold effect of the vivid coral red ground is heightened by the potter's decision to decorate the cavetto with green and blue palmettes.

The tulip has a symbolic meaning in Ottoman art. The letters of the word tulip (Lâle [ هللا]) in Turkish and Persian are the same letters used for writing the word Allah [ الله] (God). These two words have the same numerological value (66) in the abjad system (a decimal alphabetic numeral system in which the twenty-eight letters of the Arabic alphabet are assigned numerical values). Tulip is one of the leading decorative elements in Ottoman art; frequently used together with roses, hyacinths, saz leaves. It is also used with khatai blossoms as can be seen in the present dish. Tulip also played a role in imagery in Ottoman poetry. In many poems, tulip leaves are likened to the cheeks of the beloved. The word lālehkhad (lâle-had), often used in Ottoman poetry, means ‘tulip-cheeked’.

Tulips were among the most favoured motifs used in the Ottoman court workshops in the 16th century. The name ‘tulip’ is thought to have derived from the Turkish word tülbend (from the Persian word دنبلد [dulband]) -meaning ‘large cotton band which is used in the making of turban or headgear’- because of the fancied resemblance of the flower to a turban.

The present dish is rare in terms of its design. The vivid coral red, for which Iznik is so famous, is rarely used so profusely. The combination of white, light green and blue creates a graceful balance. The intertwining curves of the tulips and spring blossoms bring a sense of movement that contrasts with the still calmness of the palmettes and wave motifs in the cavetto and the rim. The small blue tulip buds, in groups of tree, symbolize the circle of life, fertility and abundance. In the Ottoman period flowers were a constant part of daily life, grown in gardens everywhere, from palaces to humble homes. Flowers were blessed reminders of the gardens of heaven. Foreign travellers and ambassadors who visited the empire, frequently remarked about this love of flowers. The 17th century Ottoman writer and traveller Evliya Çelebi describes how vases of roses, tulips, hyacinths, narcissi and lilies were placed between the rows of worshippers in the Eski Mosque and the Üç Şerefeli Mosque in Edirne, and how their scent filled the prayer halls. For further information please see, Motif from the Sadberk Hanım Museum Collection (written by Turgut Saner, Şebnem Eryavuz and Hülya Bilgi), Sadberk Hanım Museum, Istanbul, 2020, pp. 86-90.

12 RARE AND IMPORTANT IZNIK POTTERY DISH DECORATED WITH ROTATING BLUE HARES

Ottoman Empire

17th century

Diameter: 26.5 cm.

Fritware, underglaze painted in blue, coral red, green, black; depicting five running blue hares. The rim decorated with stylized leaves.

Depiction of animals is part of an old iconographic tradition in Anatolia and the present aesthetic can be stretched back to figural Seljuk art. In Ottoman art some of the earliest depictions of animals are found on Iznik ceramics in the 1520s and 1530s. Probably the most famous examples are those on the Sünnet Odası (Circumcision Hall) tiles, in the Topkapi Palace, Istanbul.

Nurhan Atasoy and Julian Raby in Iznik: The Pottery of Ottoman Turkey state that the animals from this group were a collection of the exotic and the mythical. There were coursing dogs, deer, hares, ducks, monkeys, lions, horned snakes, simurghs and confronted harpies. The style has affinities with the ‘animal chase’ which was a favoured motif in Seljuk metalwork. For further discussion please see, Nurhan Atasoy and Julian Raby, Iznik: The Pottery of Ottoman Turkey, Thames and Hudson, London, 1989, p. 257.

A related Iznik vase, featuring running blue hares, is in the Benaki Museum (inv. no. 49), Athens. Please see, John Carswell, Mina Moraitou and Melanie Gibson’s Iznik Ceramics at the Benaki Museum, Benaki Museum - Gingko, London, 2023, p. 118.

An Iznik dish, similarly decorated albeit with running blue foxes, is in the Ömer M. Koç Collection. Please see, Hülya Bilgi’s AteşinOyunu–SadberkHanımMüzesiveÖmerM. KoçKoleksiyonlarındanİznikÇiniveSeramikleri

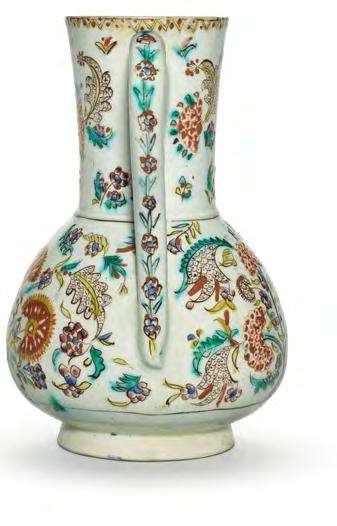

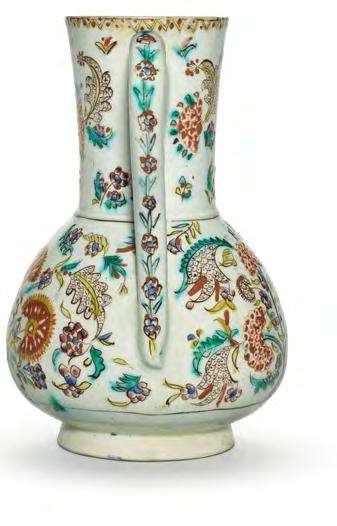

Ottoman Empire

18th Century

Height: 17 cm.

KUTAHYA POTTERY JUG DECORATED WITH CARNATIONS AND SPRING BLOSSOMS

With a globular body, long slightly flaring neck, straight cut rim and curved handle, decorated in blue, green, yellow, manganese purple and red with black outlines, with stylised carnations and spring blossoms interspersed with foliage motif, the rim decorated with a zigzag dotted band, the handle painted with a band of spring flowers, drop-shaped maker’s mark to the underside.

The city of Kütahya lies outside Istanbul, in the far north-west of Turkey. Along with Iznik, Kütahya was one of the great centers of Ottoman ceramic production. Colourful and imaginative, the tiles and vessels produced by the potters of Kütahya are highly collectible examples of Ottoman art. In the 18th century, one of the principal forms produced in Kütahya was jugs like the present one. A diverse range of these jugs were produced for the daily use of the Ottoman elite.

A Kütahya jug decorated with similar spring blossoms is published in Bernard Rackham, Islamic Pottery and Italian Maiolica, Faber & Faber, London, 1959, pl. 99a, no. 244.

The drop-shaped maker’s mark is published in the list of Kutahya maker marks in Garo Kürkman’s Toprak, Ates¸, Sır – Tarihsel Gelis¸imi, Atölyeleri ve Ustalarıyla Kütahya Çini ve Seramikleri, Suna ve Inan Kıraç Vakfı, Istanbul, 2005, p. 266.

13

Maker’s Mark at the Bottom

Ottoman Empire

Signed: Hafiz Muhammad

Rashid

Dated: 1296 A.H. / 1878 C.E.

Dimensions: 19.5 x 12.5 cm.

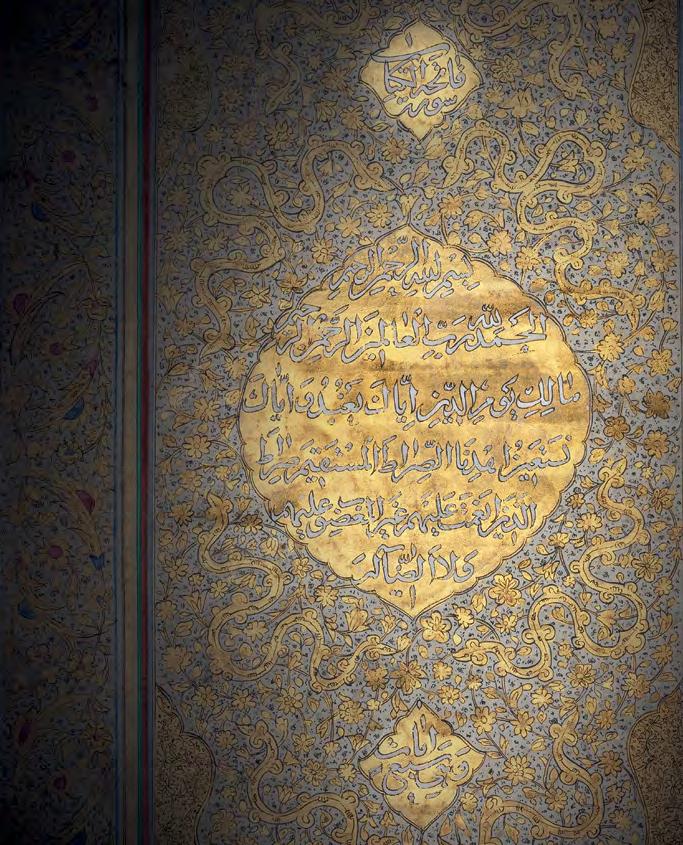

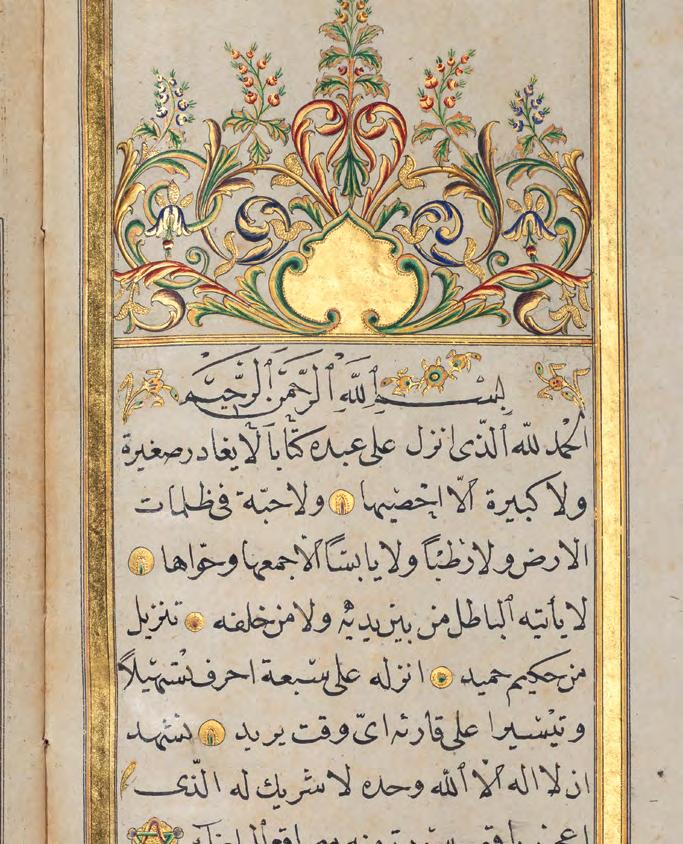

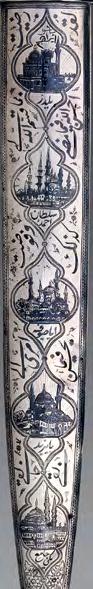

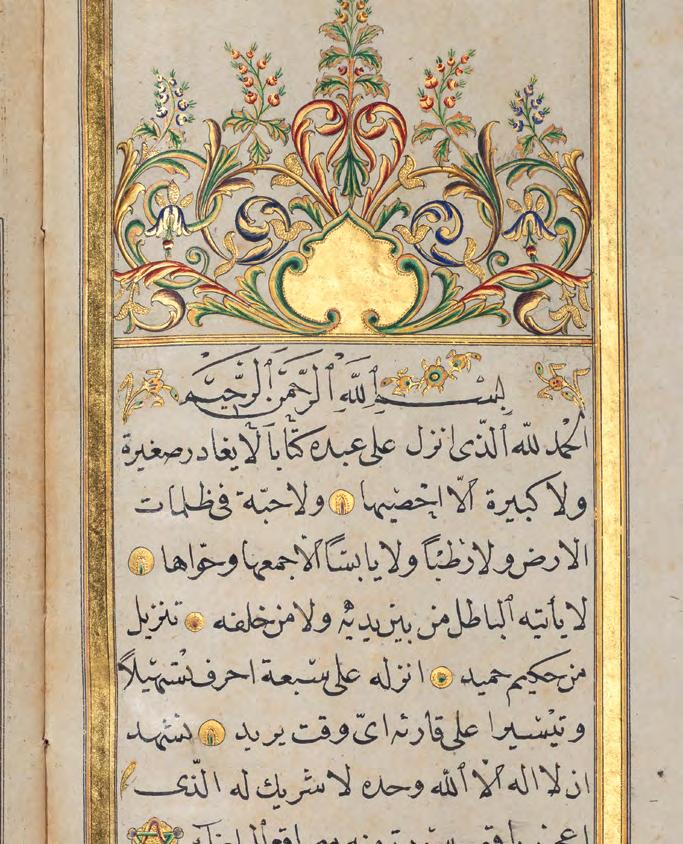

QUR’AN RECITATION DIPLOMA WITH A PEDIGREE LINE STRETCHING BACK TO PROPHET MUHAMMAD

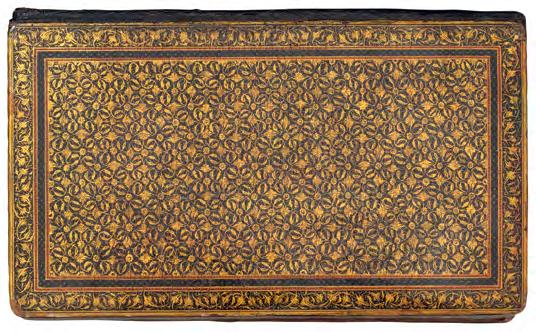

RARE OTTOMAN QUR’AN RECITATION ( QIRA‘AT ) DIPLOMA GRANTED AND COPIED BY HAFIZ MUHAMMAD RASHID, THE IMAM OF SULTAN ABDULHAMID II (R.1876-1909)

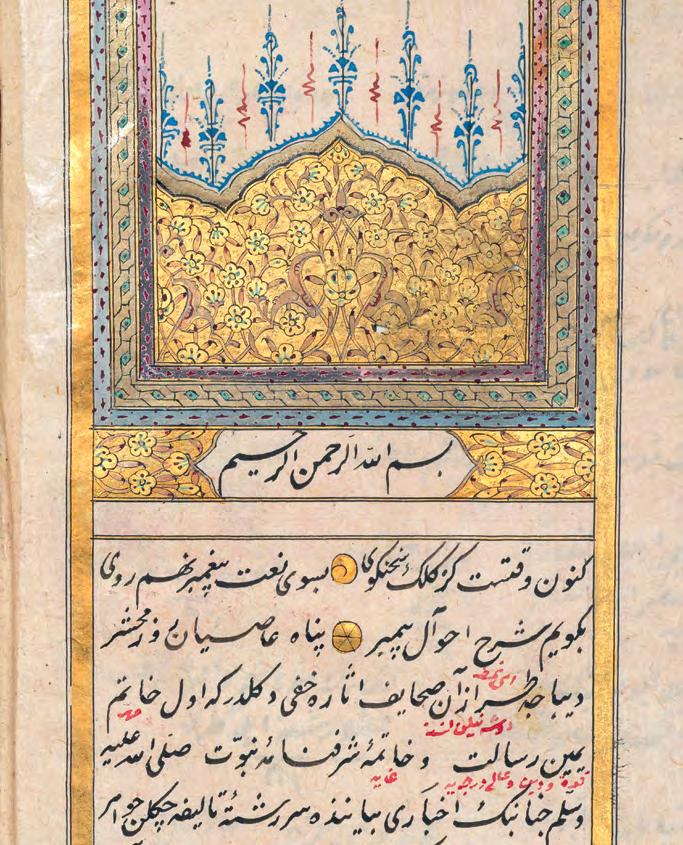

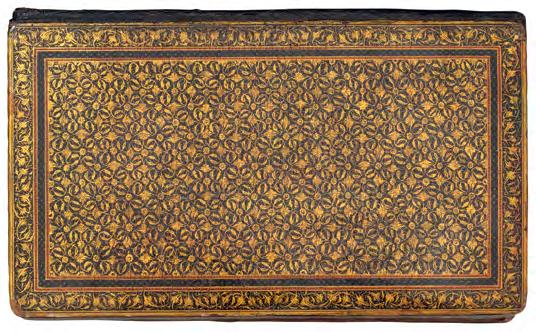

Arabic manuscript on paper, 11 leaves, 2 fly leaves, 15 lines to page, frontispiece illuminated in gold, red, green, purple pigments; written in naskh in black ink, ruled in gold and black, verses/sentences/phrases separated by gold roundels, in its original gilt, green leather binding.

The present manuscript is a rare Qur’an Recitation (Qira‘at) diploma granted to Hafiz Ismail Hakki b. Suleyman by Hafiz Muhammad Rashid, the imam of Sultan Abdulhamid II (r. 1876-1909), dated 1296 A.H. / 1878 C.E.

In the text of the diploma, the pedigree line of Hafiz Muhammad Rashid’s Qur’an recitation masters is listed as follows, stretching back to the Prophet Muhammad:

Hafiz Abdullah Efendi imam of the Ayasofya Mosque

Hafiz al-Hajj Mustafa Istanbuli, imam of the ShebSafa Kadin Mosque

Hafiz al-Hajj Ahmed Efendi, imam of the Nusretiye Mosque

Hafiz Ahmed al-Hifzi Khalid al-Naqshbandi Sheikh al-Qurra’

Al-Sayyid Mustafa AL-Naqshbandi al-Muwaqqit

Sheikh Omer bin Khalil al-Boluvi

Sheikh Hasan bin Hasan al-Busnavi

Al-Hajj Sheikh Ali al-Viidini

Al-Hajj Ahmed al-Sufi al-Kastamuni

Al-Sheikh al-Hajj Muhammad al-Na‘imi

Al-Sheikh al-Hajj Husayn bin Murad al-Erzurumi

Hafiz Ali al-Mansuri

Al-Sheikh al-Sultan Mizahi

Al-Sheikh Sahhaz al-Yamani

Muhammad al-Buqri

Sheikh Abd al-Rahman al-Yamani

Nasir al-Din al-Talavi

Sheikh Zakariya al-Ansari

Fakhr al-Din al-Dharir

Muhammad bin Yusuf al-Jazari

Abi Muhammad Abd al-Rahman al-Baghdadi

Abi Abdullah bin Abd al-Khaliq al-Misri

Sheikh Abi al-Hasan al-Shatibi

Abi al-Qasim al-Umavi

Imam al-Qurra Abi Umar

Abi al-Fath Faris

Qalun al-Madani

Abi Ja‘far Yazid

Ibn ‘Abbas

Abi Bin Ka‘b al-Harzaji

PROPHET MUHAMMAD

Hafiz Muhammad Rashid’s seal at the end of the colophon bears the signature of the seal-maker ‘Majdi’.

Provenance

Ex-Private French Collection.

34

14

Ottoman Empire

Signed: Osman al-Uwaisi Khadim al-Khirqah al-Sharif (the keeper of the Mantle of the Prophet Muhammad)

Dated: 1196 A.H. / 1781 C.E.

Dimensions: 20 x 13 cm.

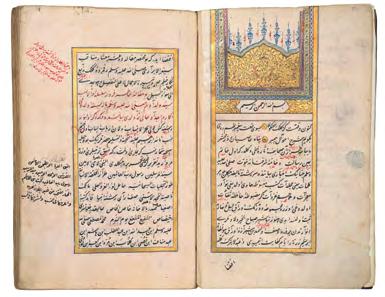

THE LIFE OF THE PROPHET MUHAMMAD (SIYAR NABI) COPIED BY OSMAN AL-UWAISI, THE KEEPER OF THE MANTLE OF THE PROPHET MUHAMMAD

DURRAT AL-TAJ FI SIRAT SAHIB AL-MI‘RAJ (THE PEARL OF THE CROWN ON THE LIFE OF THE PROPHET MUHAMMAD, THE MASTER OF ASCENSION TO HEAVEN)

Manuscript on paper, 144 leaves, 2 fly leaves, 17 lines to page, frontispiece illuminated in gold, red, green, blue, pink pigments; written in nas-ta‘liq in black and red ink, ruled in gold and black, in its original gilt, brown leather binding.

This is a rare copy of the first Siyar Nabi text written in Turkish, by the Ottoman court poet Veysi (15611628). It is copied by Osman al-Uwaisi Khadim al-Khirqah al-Sharif (the keeper of the Mantle of the Prophet Muhammad). First volume of two.

The present manuscript is the history of the Prophet Muhammad’s life, including the following sections:

The genealogy of Prophet Muhammad

The discovery of the Zam-zam well

The marriage of the Prophet Muhammad’s father

Abdullah to Aminah

The names and titles of Prophet Muhammad

The birth of Prophet Muhammad

Prophet Muhammad’s journey to Damascus

Prophet Muhammad’s marriage to Khadija

The restoration of the Holy Ka‘bah

The beginning of the revelation of the holy Qur’an

The first Muslims and Prophet Muhammad’s invitation to Islam

Caliph Umar’s convertion to Islam

The Mi‘raj of Prophet Muhammad

Prophet Muhammad’s teachings of prayer

The convertion of the Ansar to Islam

- The Hijra of Prophet Muhammad to Medina.

THE CALLIGRAPHER: OSMAN AL-UWAISI, THE KEEPER OF THE MANTLE OF THE PROPHET MUHAMMAD

Sayyid Osman al-Uwaisi b. Sayyid Muhammad Said b. Osman, better known as Osman al-Uwaisi was the Sheikh of the Hirka-i Sherif Camii (the Mosque of the Mantle of the Prophet – ar. al-Burdat al-Sharif-) in the Fatih district, Istanbul. He was the great-grand-son of Shukrullah al-Uwaisi, who brought the Burda (the mantle of the Prophet Muhammad) to Istanbul on Sultan Ahmed I’s (r. 1603-1617) order. Shukrullah al-Uwaisi was a successor of Uwais al-Qarani (d. 656) who received the mantle of the prophet as a personal gift from from Caliph Umar and Caliph Ali on the command of Prophet Muhammad. Osman al-Uwaisi was an eminent calligrapher particularly celebrated for his mastery in the nas-ta’liq script. He studied calligraphy under the supervision of master calligrapher Dedezade Mehmed Said Efendi (d. 1749). The date of his death is unknown.

Provenance

Private French Collection. The manuscript was part of the collection of a famous French orientalist bookseller founded in 1930 and active until 1977.

15

36

16

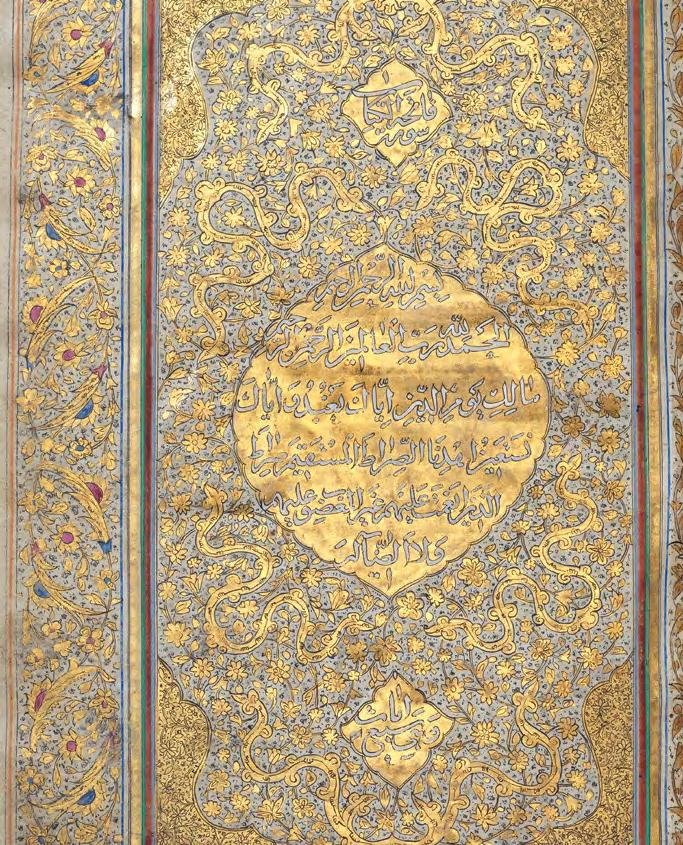

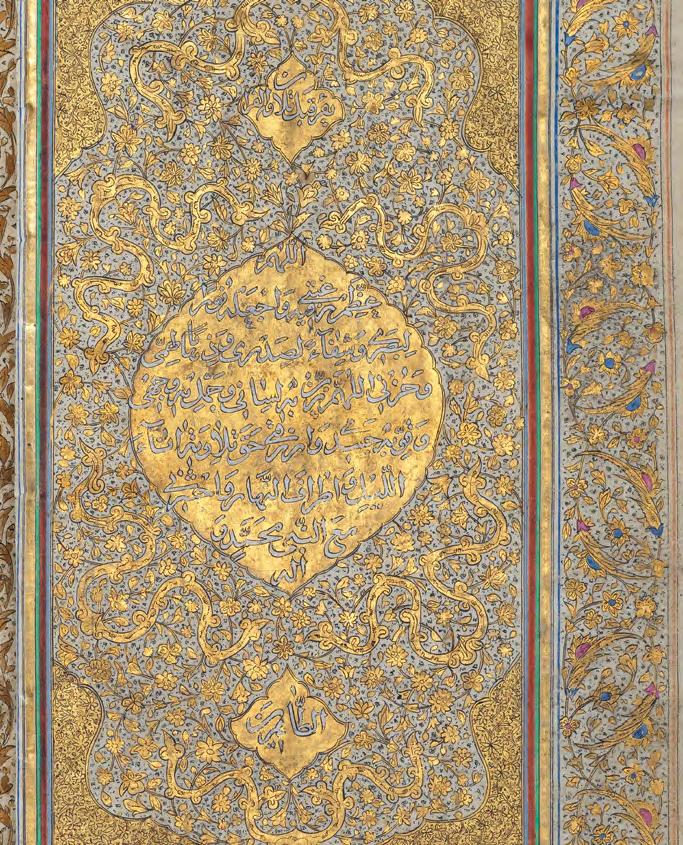

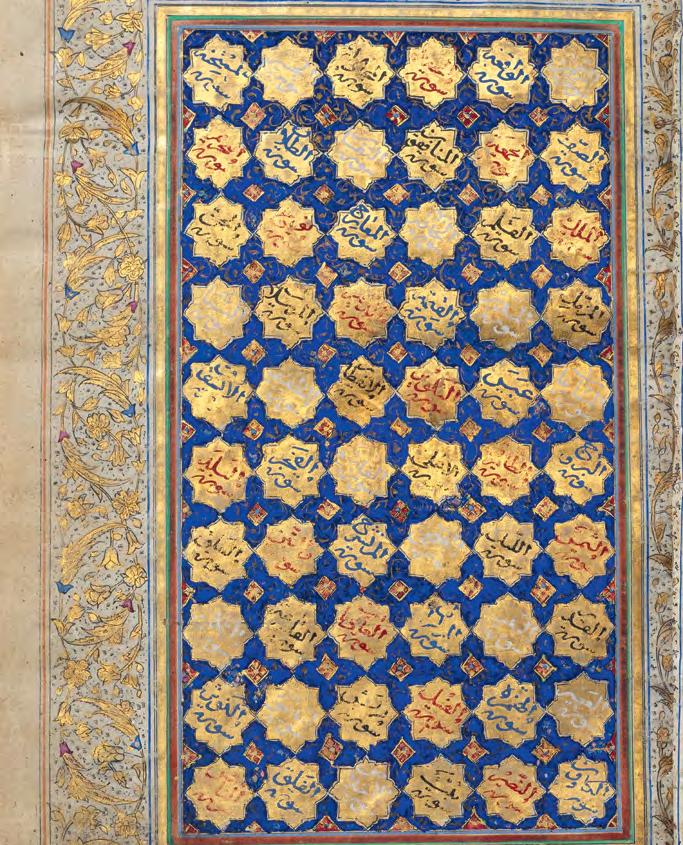

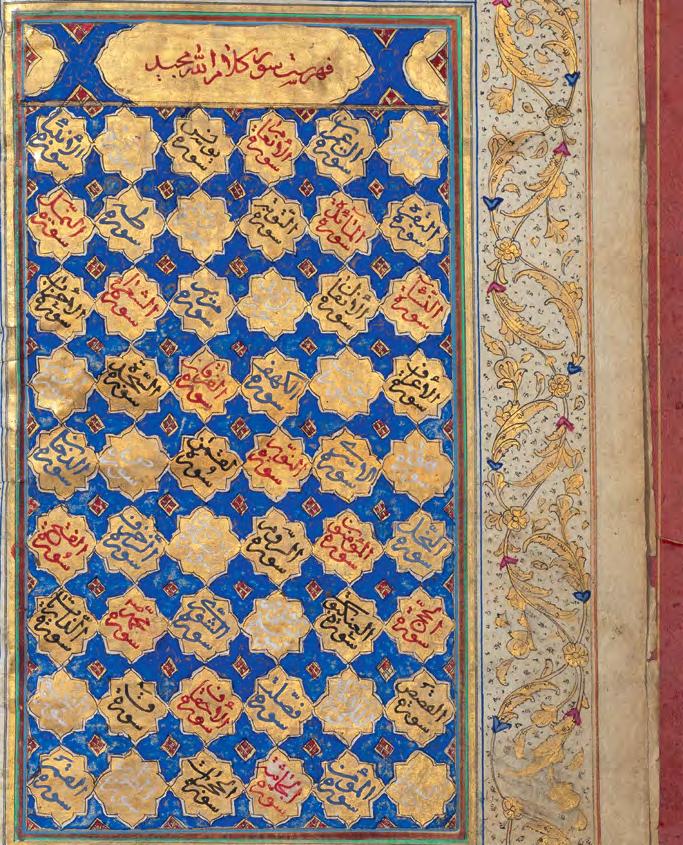

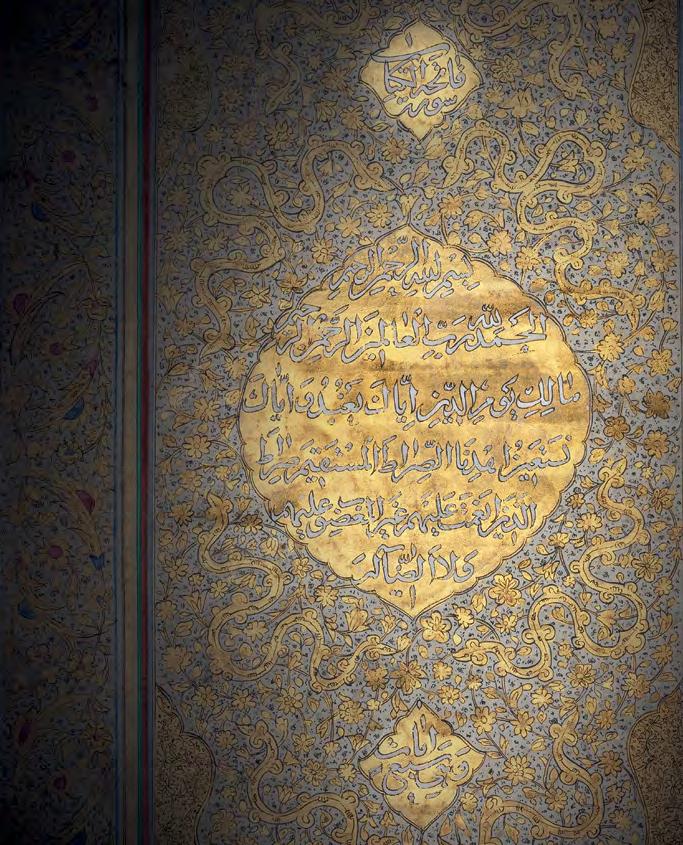

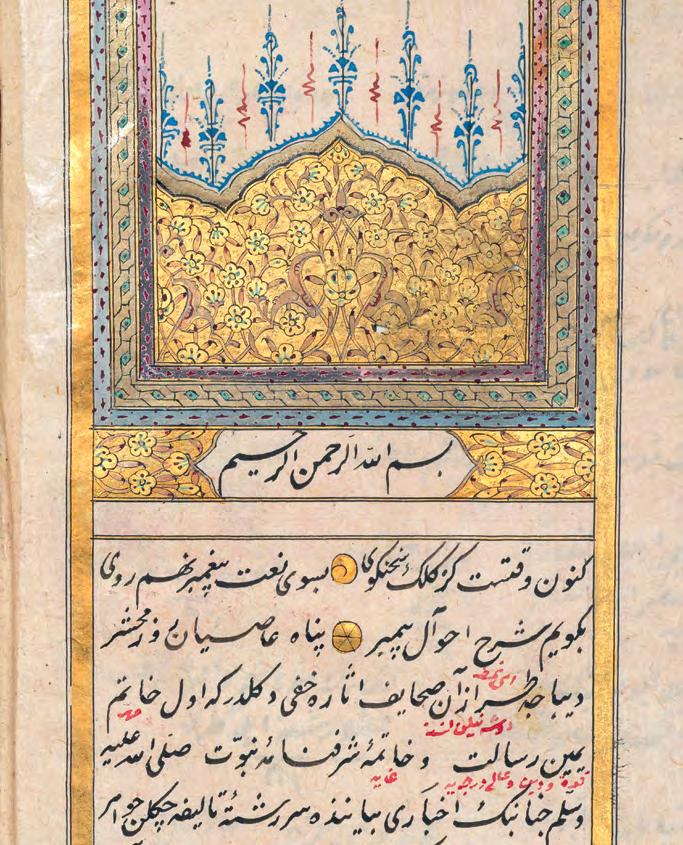

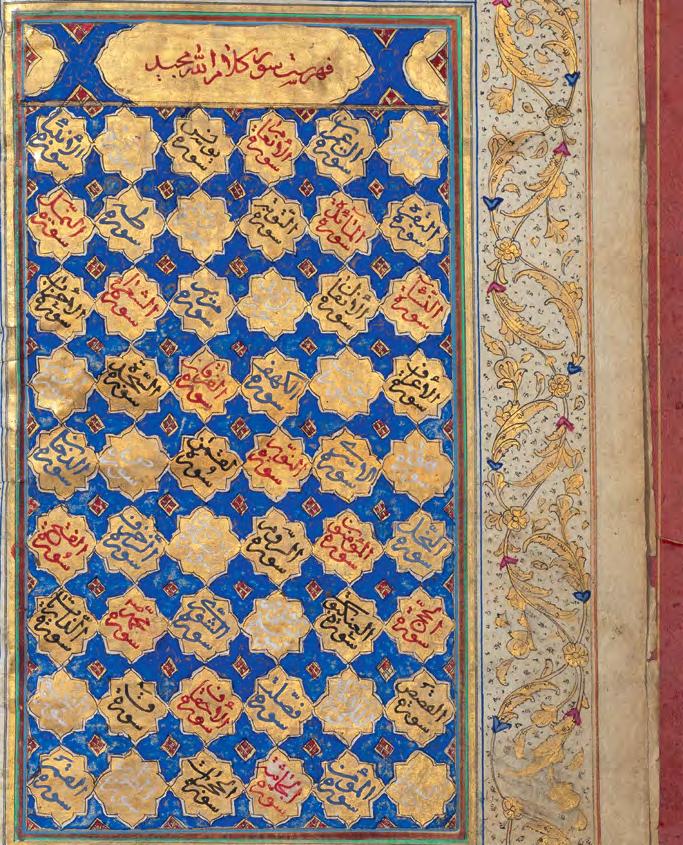

IMPERIAL

QAJAR QUR’AN COPIED FOR NASIR AL-DIN

SHAH’S SON-IN-LAW PRINCE MUAYYAD AL-DAVLA (D. 1912)

Qajar Persia

Signed: Ismail bin Visal

Dated: 1278 A.H. / 1861 C.E.

Dimensions: 17.5 x 10.5 cm.

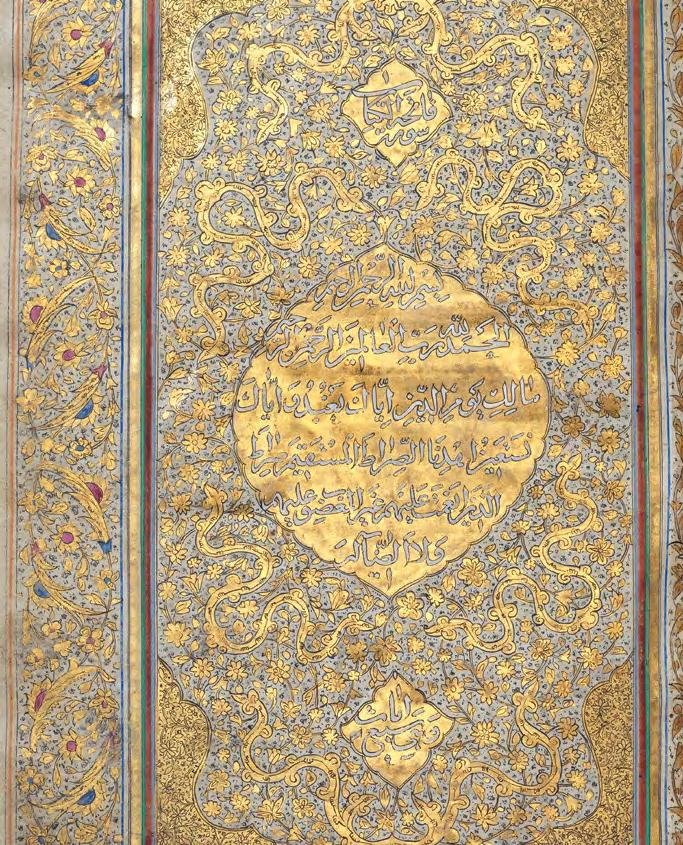

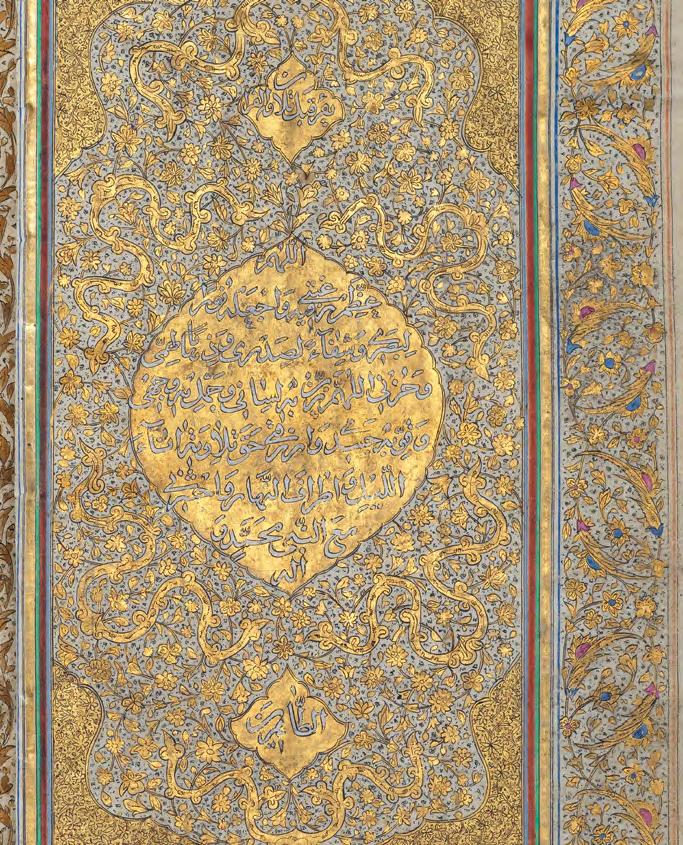

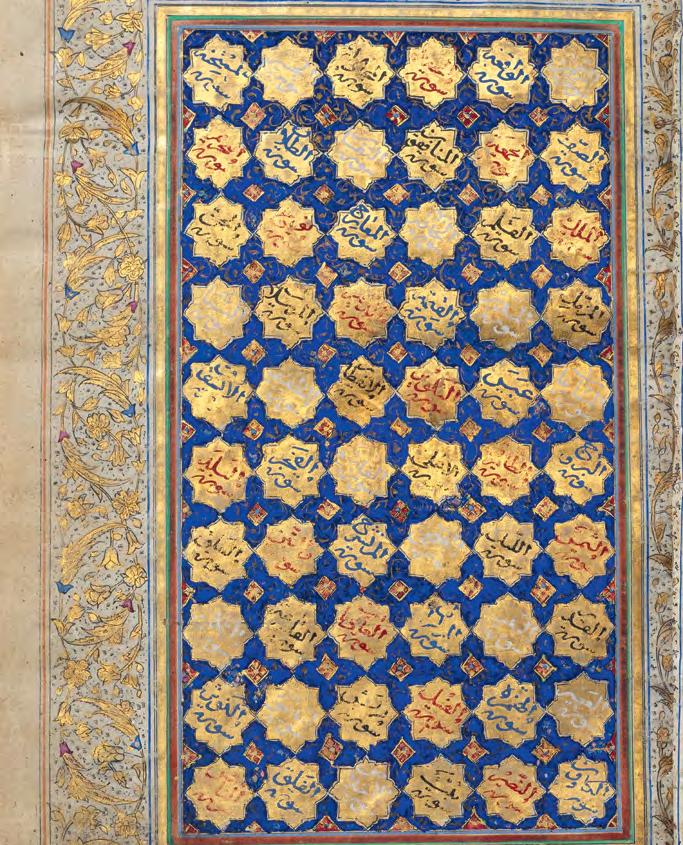

Manuscript on paper, 240 leaves, 2 fly leaves, 19 lines to page, opening with three consequent double pages with the index, prayers and the Surat al-Fatiha and the beginning of Surah al-Baqara lavishly illuminated in gold and polychrome pigments; written in naskh in black ink, ruled in gold, red, green; surah headings illuminated in gold and polychrome, verses separated by gold roundels, in its original lacquered binding.

The dedication above the colophon line:

“Hasb al-amr-i Navvab-i Mustatab Ashraf-i As’ad-i Vala

Shahzadah Muayyad al-Davla Dama Jalalahu Tahrir Shud”

(Written on the command of the most esteemed and exalted Prince Muayyad al-Davla may his glory be perpetual).

Ismail b. Visal Shirazi (d. 1869)

Muhammad Ismail b. Visal was born in 1246 A.H./1830 C.E. in Shiraz. He was the fifth son of the famous Qajar court calligrapher and poet Muhammad Shafi’ Visal Shirazi. Ismail himself was also a poet and used the pen-name ‘Tavhid’. He became a master calligrapher. He was praised especially for his skill in naskh script. His calligraphic works can be found in museums and private collections around the world. He died in Shiraz in 1286 A.H./1869 C.E.

Prince Mirza Muayyad al-Davla (d. 1912)

Qajar Prince Abu al-Fath Mirza Muayyad al-Davla (d. 1912) Abu al-Fath Mirza Muayyad al-Davla was a Qajar prince who held a number of governorships. His father was Sultan Murad Mirza Husam al-Saltana, who likewise occupied a succession of government posts. He was married to Princess Afsar al-Davla, daughter of Nasir al-Din Shah by his first marriage, and was thus a brother-in-law of Kamran Mirza Naib al-Saltana, who was for many years governor of Tehran. His first appointment was to the governorship of Yazd in 1287 A.H./1870 C.E., followed by that of Isfahan a few years later; he held both these posts on behalf of his father. In 1293 A.H./1876 C.E. Husam al-Saltana was appointed governor of Kirmanshah and Kurdistan, and he delegated the administration of Kurdistan to his son. Muayyad al-Davla was transferred from Kurdistan to Zanjan in 1299 A.H./1881 C.E., where he remained for four years until a further move took him to Gilan. During his two years’ governorship of Gilan, he gave temporary refuge to the revolutionary Mirza Aqa Khan Kermani before he fled Iran for exile in Istanbul (Nazem-al-eslam Kermani, Tarikh-i bidari-i Iranian: Muqaddema, ed. `A. S. Sirjani, Tehran, 1346 /1967, p. 13). He was sporadically reappointed to the governorship of Gilan for the following five years, until in 1310/1893 when he was definitely reassigned to Khorasan. According to Muhammad Hasan Khan I’timad al-Saltana (Ruz-nama-i khatirat, ed. I. Afshar, 2nd ed., Tehran, 1971, p. 874), he established a strict government policy after his arrival in Mashhad, and the period of his governorship appears to have been marked by recurrent turbulence. Again according to I’timad al-Saltana (ibid., p. 951), he hoarded grain and imposed extortionate taxes. Despite his wife’s energetic intercession with Nasir al-Din Shah, he was dismissed from his post on 5 Muharram 1313/29 June 1895. In 1325/1907 he was appointed to the governorship of Fars. He died in 1912 and was buried in Qum.

Provenance

Property of a lady

Private French Collection. inherited from her family in the beginning of the 19th century.

38

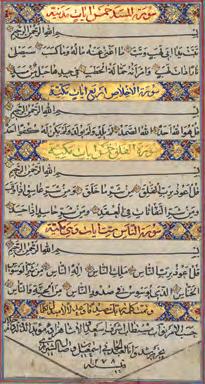

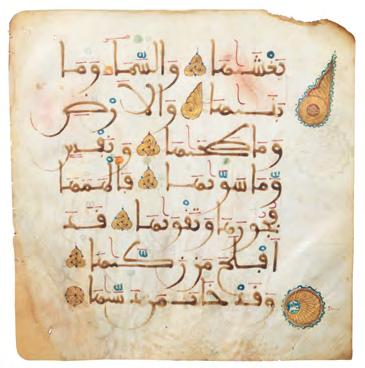

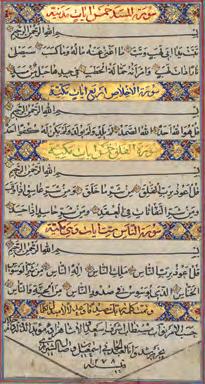

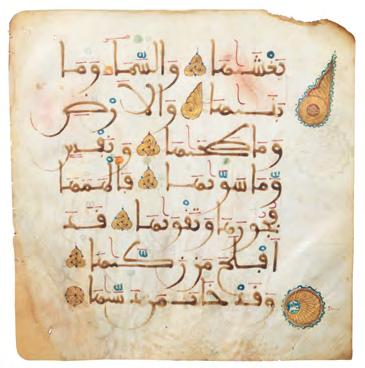

17 RARE QUR’AN FOLIO IN MAGHRIBI SCRIPT WITH GOLD SURAH HEADING

Southern Spain or Morocco

13th Century

Dimensions: 27.2 x 26.4 cm. Sepia, blue, red ink and gold on vellum.

Folio in square format vellum inscribed on both sides with seven lines, in maghribi script in sepia ink, diacritics and vocalization in red, blue and gold. The verses separated by gold and polychrome illuminated motifs in various rosettes, palms, and marginal illuminations marking the divisions of the text. The surah title inscribed in gold letters in kufic script with a marginal medallion illuminated with palmettes in the extension.

The Text:

The Qur’an, Surah al-Balad, verses: (end of) 19 and 20. Followed by Surah al-Shams verses: 1-3 and -on the reverse- Surah al-Shams verses: 3-10.

Translation:

“… In the name of God, the lord of mercy, the giver of mercy. By the sun in its morning brightness and by the moon as it follows it, by the day as it displays the sun’s glory, and by the night as it conceals it, by the sky and how He built it, and by the earth and how He spread

it, by the soul and how He formed it, and inspired it [to know] its own rebellion and piety. The one who purifies his soul succeeds.” The Qur’an, translated by M. A. S. Abdel Haleem, Oxford University Press, 2004, p. 423

The large curves of the free-flowing maghribi script bring lightness while retaining an aspect of solemnity from the formal, majestic kufic. Calligraphy in the western part of the Islamic world was not regulated by the same rules regulated in the east. The fourteenth century historian Ibn Khaldun informs us that calligraphers from the Maghrib were trained to write whole words rather than separate letters, as was the tradition in the east. They retained a freedom of interpretation while seeking an overall balance on the page through intrinsic awareness of proportion. For further discussion please see, From Cordoba to Samarqand – Masterpieces from the Museum of Islamic Art in Doha, Musée du Louvre Editions, 5 Continents, 2006, p. 162.

A folio from the same Qur’an is published in the exhibition catalogue, The Unity of Islamic Art, The King Faisal Foundation, Westerham Press, 1985, No. 11, p. 28.

Provenance

Ex-Private French Collection, Paris, formed between 1975-2000.

44

18

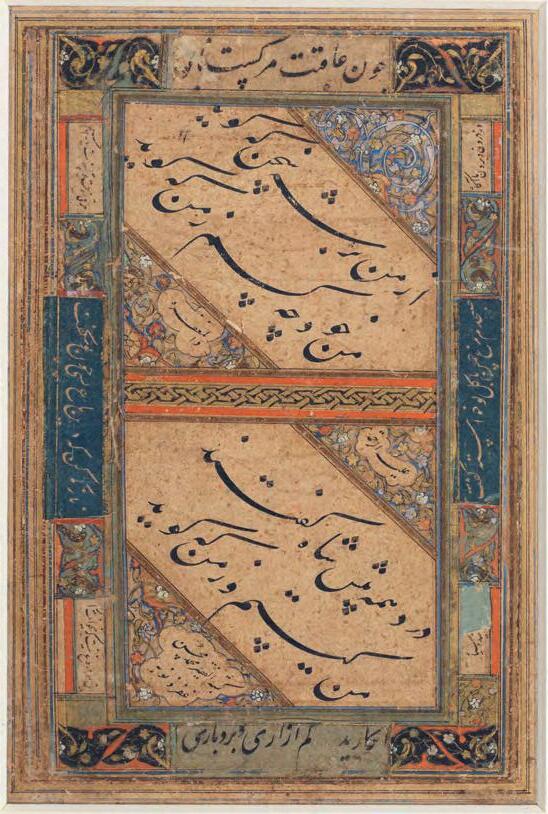

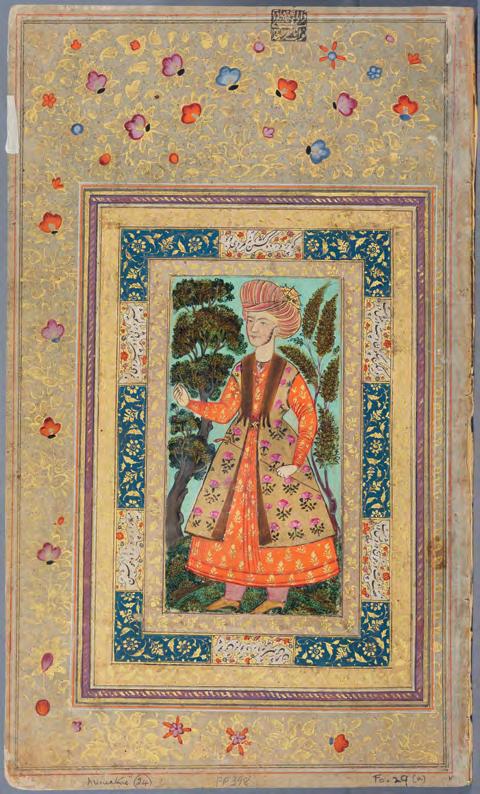

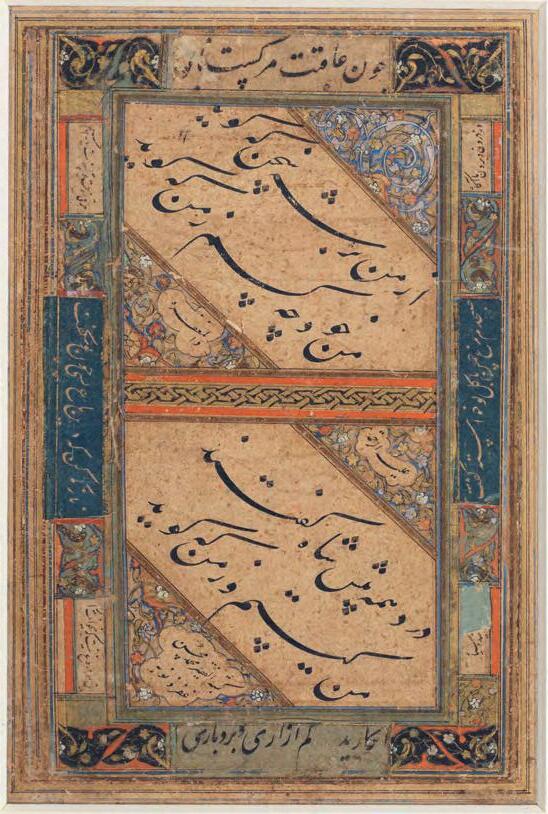

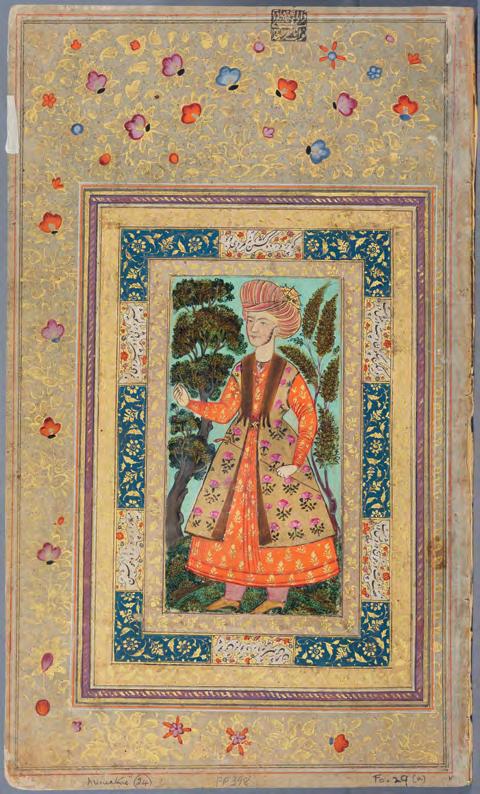

PORTRAIT OF PRINCE DANIYAL MIRZA AND ILLUMINATED CALLIGRAPHY MOUNTED ON A ROYAL MUGHAL ALBUM PAGE

Mughal India

Circa 1600

Page size: 30.8 x 20.4 cm.

Painting size: 13.7 x 8.3 cm.

Calligraphy size: 15.5 x 8 cm.

A portrait of Prince Daniyal (1572 - 1605) standing facing right, wearing a striped orange turban and transparent jama embroidered with gold zari, a talwar in his right hand and a katah tucked into his patka, a rondache on his left arm, sprigs of flowers in the background, drawing on paper with the use of colours and gold, Mughal or Deccan, c. 1600, mounted on a seventeenth century Mughal album page with cartouches of nasta’liq calligraphy and illumination in colours and gold, an erroneous inscription in nasta’liq script naming the subject as Abdullah Khan Uzbek at bottom, a quatrain of Persian poetry written in nasta’liq script with illumination in colours and gold signed by Muhammad Muhsin on reverse.

Prince Daniyal was the third son of the Mughal emperor Akbar (r. 1556-1605) and much favoured by his father, sharing a love of poetry which he wrote himself with many of his poems in Persian and Hindi. Daniyal was also an able general and was

made Viceroy of the Deccan in 1599, leading several Mughal campaigns having previously been appointed a governor to Allahabad in 1597. His early death from alcoholism at the age of thirty-two in 1605 was followed seven months later by the death of Akbar.

The Painting

The exact whereabouts of where this painting was executed is fascinating to ponder with Prince Daniyal’s campaigns in Allahabad and the Deccan. Jahangir, as Prince Salim and heir to Akbar’s throne, established a school of painting c. 1600 -1604 at Allahabad where his younger brother had been governor. From there we know that Prince Daniyal moved onto the Deccan. Mughal artists were certainly on the move at the turn of the seventeenth century and it is clear with the calligraphy by Muhammad Muhsin on this album page, Prince Daniyal was a keen and valued patron. Several portraits of him are known and as a son of Akbar and younger brother of the future Mughal emperor Jahangir, he would have been a popular subject for Mughal artists. One portrait with an inscription to the Mughal artist Manohar, c.16001605 is in the Kevorkian album in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. A further portrait , again inscribed to Manohar, c.1600-1605 is in the Walters Art Gallery, Baltimore (W.668, fol.28). One example in the National Gallery of Canada (23557) depicts Prince Daniyal holding a bow and arrow during his time in the Deccan, c. 1603. Another is in the Bodleian Library , Oxford (Douce Or. a.1, folio 29a) and a third in the British Museum (1920,0917, O.13.34), signed by Muhammad al-Samarqandi. These latter three portraits all depict Prince Daniyal facing right and are mounted on royal album pages with borders in colours and gold.

Portraits were usually painted with the sitter facing in profile rather than directly towards the artist, giving a historical record to the subject’s presence at the Mughal court. Such fine portraits of Mughal royals and courtiers mounted in royal albums with fine specimens of calligraphy were of great significance and were frequent commissions during the seventeenth century, keeping the Mughal studios well occupied, giving vivid backdrops to the Mughal courts and the reigns of its monarchs. Generating a curiosity that lasts to this day.

The Calligraphy

It is clear from the quatrain written in fine nasta’liq script by Muhammad Muhsin that this fine album page was destined for a royal patron who might well have been Prince Daniyal.

The Persian Quatrain on the reverse reads:

دیوگ هک نخس هش رب نم زا

دیوگ هک نخس مسک هچ دوخ نم

دنتفگ هاش شیپ همه درد

دیوگ هک نم ز و متسیک نم

Translation of the Persian Quatrain: [Oh you!] the one who talks to the emperor about me...

Who I am, myself, am I someone about whom he shall speak?

And they mention my need in the presence of the emperor.

Who am I, am I someone about whom he shall speak?

The Ottoman historian Mustakimzade Suleyman Sadeddin Efendi recorded Muhammed Muhsin in his famous Tuhfe-i Hattatin (biographies of Muslim calligraphers). According to Mustakimzade, Muhammed Muhsin studied calligraphy under the supervision of the famous Shaybanid court calligrapher Mahmud b. Ishaq al-Shihabi (d. 1583) who worked for the Uzbek ruler Ubayd Khan in Bukhara, and after his death in 1539, for Shah Husayn Balkhi Shihabi. Please see, Tuhfe-i Hattatin, Istanbul, 1928, p. 724.

Muhammad Muhsin appears to have sought patronage under Prince Daniyal (1572-1605) and other members of the Mughal court in the early years of the 17th century, during which the present album folio was produced. The folio brings the portrait of Prince Daniyal and Muhammad Muhsin’s calligraphy together. The calligraphy is clearly addressed to a person who has been mentioning the calligrapher’s needs to the emperor (the word ‘shah’ is used twice).

The person whom Muhammad Muhsin addresses in his calligraphy is most likely Prince Daniyal who appears to have talked to his father, the Mughal emperor Akbar (r. 1556-1605) about the calligrapher and his poverty.

The calligraphy was probably presented to Prince Daniyal as a sign of the artist’s gratitude which made its way into a princely album from which this folio is coming from.

The last line of the quatrain, “Who am I, am I someone about whom he shall speak?”, is taken from the last chapter of the famous Timurid poet Abdurrahman Jami’s (d. 1492) Haft Avrang. Here, the use of this line from Jami’s poem is understandable since the Mughal ruling elite saw the Timurids as their ancestors and they greatly admired Timurid culture and literature.

Bibliography

M.C. Beach, The Grand Mogul Imperial Painting in India 1600-1660, Williamstown, Massachusetts, 1978, pp. 18, 19, 33, 76 and 135.

Toby Falk and Mildred Archer, Indian Miniatures in The India Office Library, London, 1981, no. 5. pp. 48 and 360.

S. C. Welch, A. Schimmel, M..L. Swietochowski and W. M. Thackston, The Emperors’ Album, New York, 1987, no. 18.

Linda York Leach, Mughal and Other Indian Paintings from the Chester Beatty Library, London, 1995, pp. 140, 152, 242, 292, 333 and 373.

E. Hannam, Eastern Encounters, Four Centuries of Paintings and Manuscripts from the Indian Subcontinent, London, Royal Collection Trust, 2018, no.15, (RCIN 1005018).

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank Margaret Erskine for writing this article on the present miniature painting.

Provenance

Private French Collection, Paris. Terence McInerney, New York, 1997.

48

Calligraphy on the reverse

19

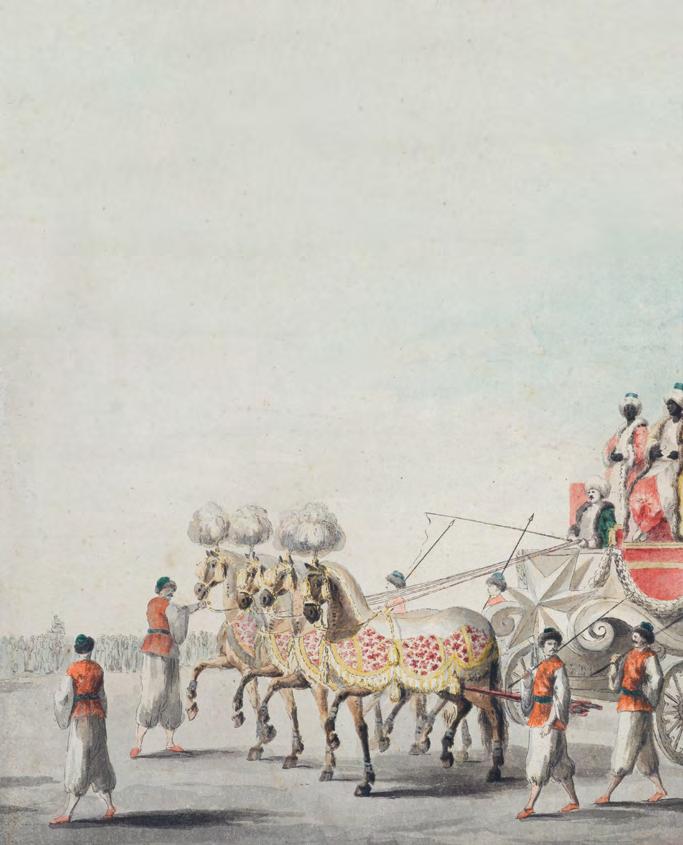

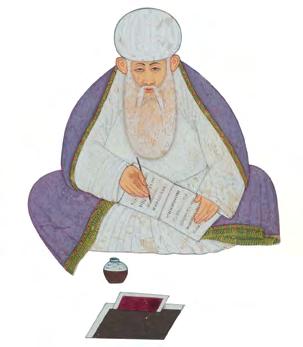

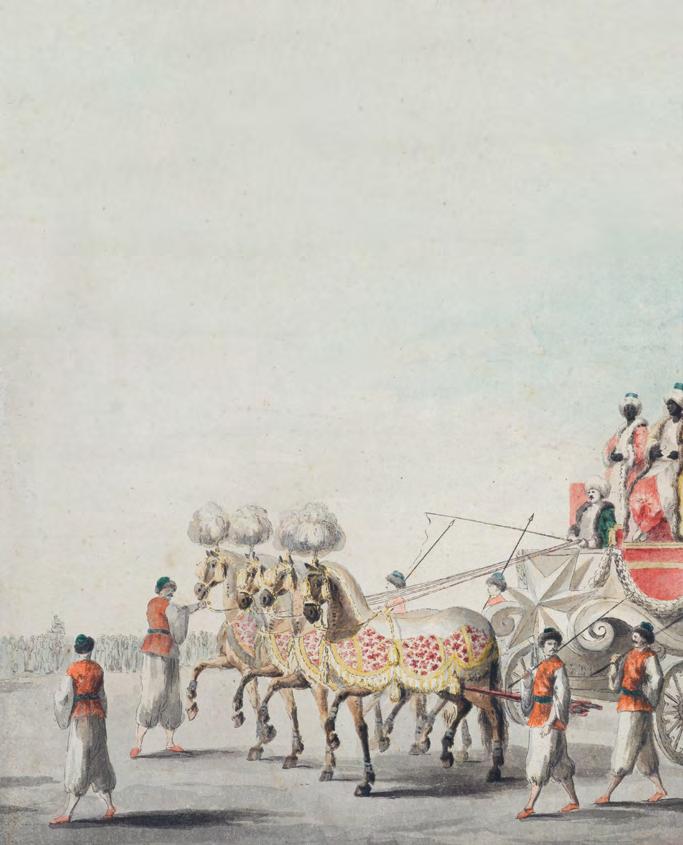

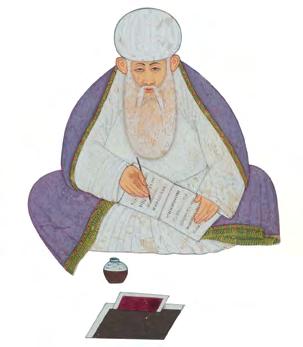

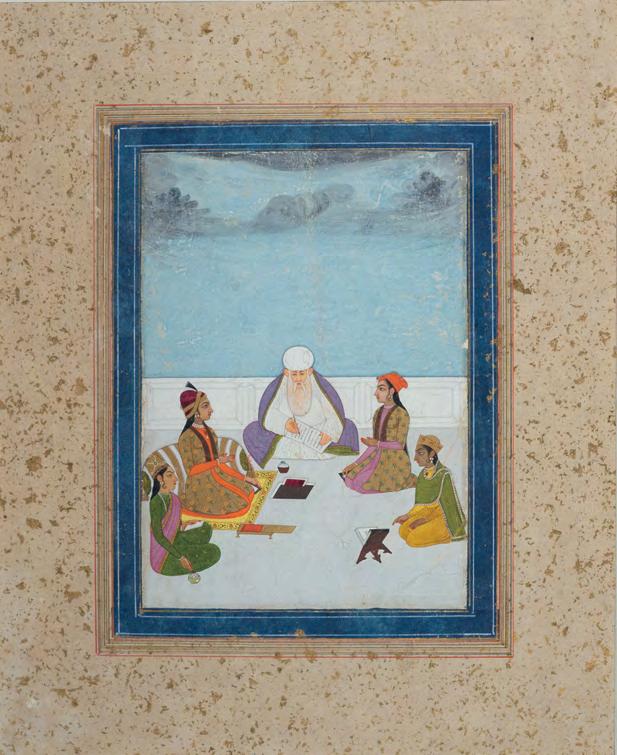

A MULLAH SEATED WITH MUGHAL PRINCESSES

Lucknow

Circa 1780

Dimensions: 40 x 28.8 cm.

Gouache on paper heightened with gold, blue border with white margin rules. A mullah seated in discussion with two Mughal princesses on a terrace. The mullah dressed in white writing in a text, both princesses adorned with pearls and jewels and wearing turbans decorated with jewels and an aigrette, their floral furtrimmed brocade jamas over long robes. Two female attendants kneeling in the foreground.

Patronage of the arts flourished at Lucknow under Nawab Asaf ud-Daula, the ruler of Lucknow between 1775 and 1797. Although as a ruler, Asaf ud -Daula had little real political power, owing to the tight grip of the British at this time, impressive monuments were built including a great mosque and lavish palaces during his reign in the last quarter of the eighteenth century. The thriving cosmopolitan community of Lucknow, where there was no jizya (an abolished poll-tax on non-Muslims), welcomed Europeans, native artists and calligraphers; particularly those from Delhi who sought studios away from the declining Mughal court. Terrace scenes in a traditional Mughal style, were particularly popular during the eighteenth century and this charming depiction of a Muslim mullah with his young disciples is such an example, illustrating well how painting thrived at Lucknow under Asaf ud-Daula.

Further reading

Toby Falk and Mildred Archer, Indian Miniatures in the India Office Library, London, 1981, pp. 135-188.

J. P. Losty and Malini Roy, Mughal India - Art, Culture and Empire, London, 2012, pp. 149- 201.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank Margaret Erskine for writing this article on the present miniature painting.

50

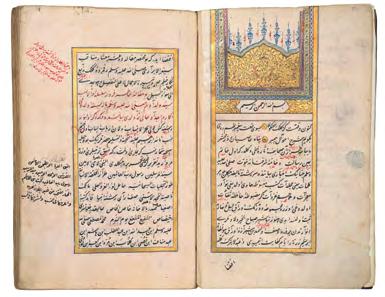

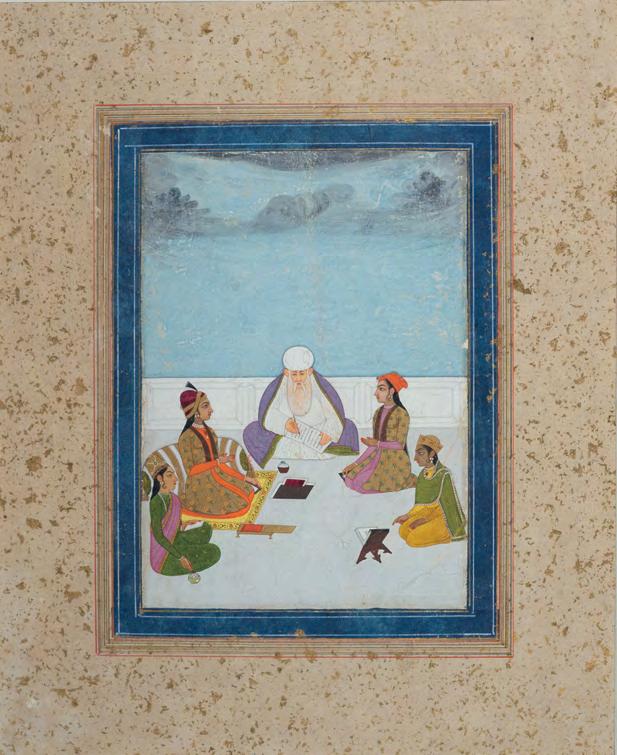

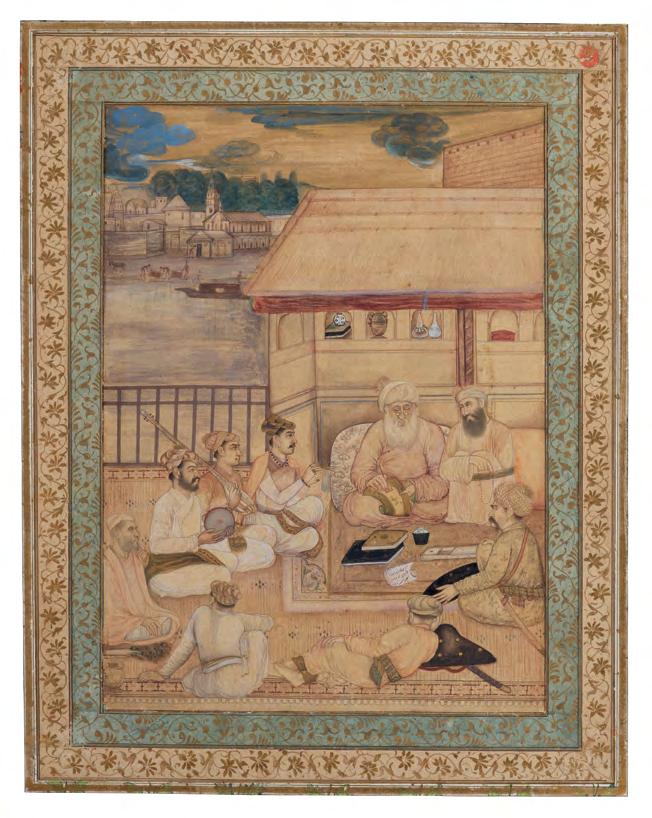

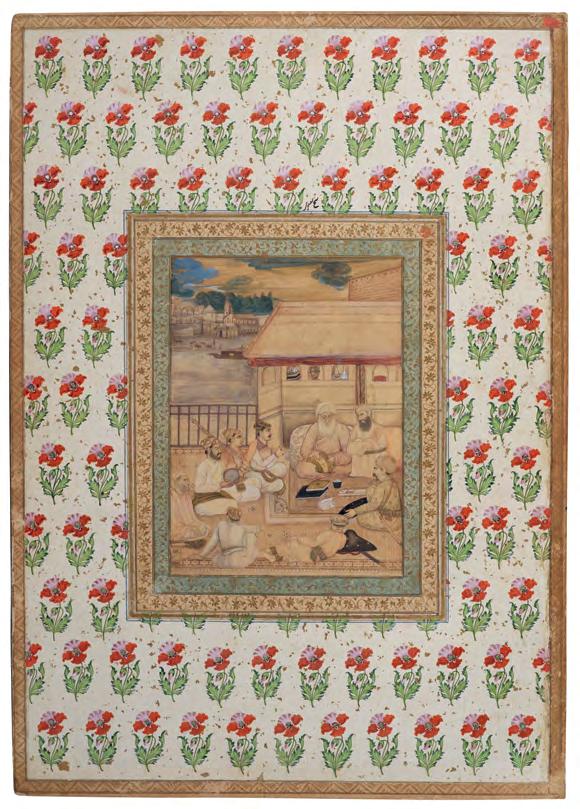

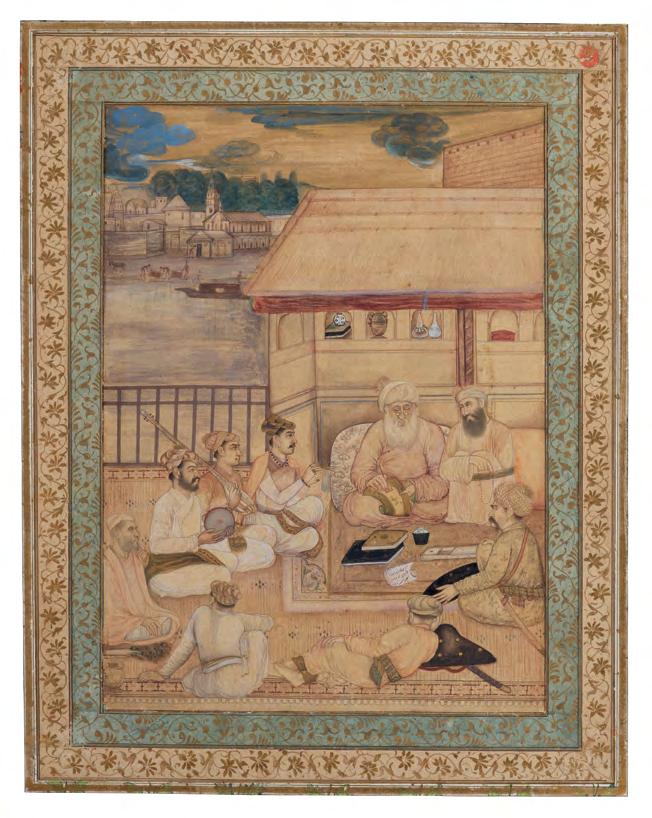

20 A YOUNG PRINCE SEATED WITH A MYSTIC, AFTER GOVARDHAN

Mughal India

Second Half of the 17th Century

Painting: 21.2 cm x 15.6 cm.

Calligraphy on reverse:

16.4 cm. x 8.6 cm.

Album page: 52.4 x 37.3 cm.

A young prince seated with an elderly, bespectacled mullah, followers and musicians in a hut close to a lake, boatmen at work on the lake with a town in the background, the musicians playing a tambourine and a tambur, all of the group seated around the elderly mullah depicted with a long-flowing white beard, holding a scroll which bears the Arabic words “Birr-lillāh” (Benevolence belongs to God), two of the followers lounging in the foreground, drawing on paper with use of colours and gold, mounted on an 18th century Lucknow album page with gilt decorated floral borders and an inscription in black script, outer border with a bold floral decoration depicting poppies, six lines of nasta’liq calligraphy on reverse which is from the Preface of the Shah Muhammad Muzahhib Album (Dibāche-i Muraqqa‘-i Muhammad Muzahhib).

ARTIST

Govardhan was a major artist at the Mughal court with many of his works now in public and private collections across the globe including the seventeenth century Kevorkian album now in the Metropolitan Museum, New York. This miniature painting is clearly by a close follower of Govardhan with many of the painting’s attributes fitting well with his distinctive, noticeable style.

He served three generations of Mughal emperors and the Crown Prince Dara Shikoh, his career flourishing over many decades from 1595-1640. Having been born a khanazad, as one born in the Mughal palace, Govardhan trained at an early age towards the end of the sixteenth century in the studio of Akbar (r.15561605) before working at the Allahabad studio of Prince Salim, Akbar’s successor later to become the Mughal emperor Jahangir (r.1605-1626). His reputation was particularly well established during the reigns of Jahangir and Shah Jahan (r.1626-1666) earning him an important place as a Mughal master, leaving a legacy after his death for later artists to follow. This exquisite fine drawing on paper with the soft palette heightened with colours and gold with shadowing of the faces is a fine example typical of Govardhan’s style. The depiction of two devotees lounging in the foreground facing the mullah with their backs to the viewer is another particular feature. Govardhan’s ability to draw each figure in great detail and to capture the respect and regard given to religious figures is clearly shown in this particular painting, reflecting well his distinctive style and important position at the Mughal studio over three consecutive reigns of the Mughal empire. He was an able teacher to his followers. Totally captivating.

SUBJECT

A gathering of learned students including a young prince around an elderly teacher is a common theme in Indian miniature painting, clearly depicted in this Mughal work after Govardhan. The group gathered in a hut indicates the mullah’s holy status and the lakeside situation in a watery setting adds to the tranquillity of the scene.

The location may well be Dal Lake in Srinagar, Kashmir, an area occupied by Dara Shikoh during his prince hood. The two musicians depicted reflect the position of the young prince and the other figures with books, pens and scrolls, seated in earnest discussion add to the ambience of the subject.

Crown Prince Dara Shikoh (1615-1659), the favourite son and heir of Shah Jahan, was an enlightened scholar interested in both the mysticism of Islam and Hinduism. His intellect cannot be underestimated and his untimely death at the hands of his ambitious brother Aurangzeb took the Mughal dynasty on a different course. From an early age Dara Shikoh had developed an interest in religion and philosophy. He later went onto study Sufism and with his sister Jahanara Begum became a disciple of the Qudi Sufi mystic Mulla Shah. He also took great interest in Hindu texts, producing a Persian translation of the Sanskrit Upanishads. Dara Shikoh was also an accomplished calligrapher and patron of the arts, giving great support to Mughal artists and their studios. The subject adds to the beauty and meaning of this painting, following well in the interest in mysticism in seventeenth century India.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

For further reading and comparisons:

R.H. Pinder-Wilson, A Persian Translation of the Mahabharata, British Museum Quarterly 20, no 3, London,1956.

E. Binney, The Mughal and Deccani Schools, Indian Miniature Paintings from the Collection of Edwin Binney 3rd, Portland, 1973, no 56.

T. Falk, Rothschild Collection of Mughal Miniatures, P&D Colnaghi & Co Ltd Exhibition Catalogue, London, 1976, no 103.

A.K. Das, Mughal Painting during Jahangir’s Time, Calcutta, 1978, pp. 75, 88,95, 125, 148, 158, 172, pl.29.

M.C. Beach, The Grand Mogul, Imperial Painting in India 1600-1660, Williamstown, Massachusetts, 1978, pp. 118-125, pls. 22, 41 and 62.

S.C. Welch, India! Art and Culture, New York, 1985, Nos 158-160.

S.C. Welch, A. Schimmel, M.L. Swietochowski and W.M. Thackston, The Emperors’ Album: Images of Mughal India, New York, 1987, no 76.

R. Crill and K. Jariwala, The Indian Portrait, London, 2010, no 21.

J.P. Losty and M. Roy, Mughal India Art, Culture and Empire, London, 2012, pp. 105, 124-128, figs. 57, 76 and 79.

M. Fraser, Selected Works from the Stuart Cary Welch Collection of Indian and Islamic Art, London, 2015, cat. 16, pp.66-67.

C. Glynn, Y. Rice and William W. Robinson, Rembrandt and the Inspiration of India, Los Angeles, 2018, pl. 6.

E. Hannam, Eastern Encounters, Four Centuries of Paintings and Manuscripts from The Indian Subcontinent, Royal Collection Trust, London, 2018, no.33.

A young prince with mystics, Aga Khan Museum, Toronto, AKM 498.

The Edith and Stuart Cary Welch Collection, Sotheby’s, London, 25 October, 2023, lot 20.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank Margaret Erskine for writing this article on the present miniature painting.

Provenance

Ex-French Private Collection, Paris.

54

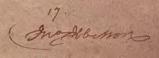

21 A PORTRAIT OF A YOUNG NOBLEMAN, POSSIBLY SAFI KHAN

Mughal India

Circa 1680

Painting: 16.5 cm. x 10.7 cm.

Including borders:

25.5 cm. x 19.6 cm.

A young nobleman standing facing left holding a rose sprig, wearing a striped, yellow jama and a yellow turban decorated with a jewelled sarpech, a sword and shield hanging from his floral patka, flowers including irises and grass at his feet, gouache on paper, mounted on an album page with gilt decorated borders, an inscription in English on reverse with a reference to the name Ibbetson.

This charming, delicate seventeenth century Mughal miniature painting of a young nobleman against a plain background with flowers at his feet is a fine example of Mughal painting executed during the reign of Aurangzeb (r. 1658-1707) with all the qualities of Mughal portrait painting established during the reign of Shah Jahan (r. 1627-1658). It bears many similarities to a likeness of Safi Khan, a mansahbdar working at the court of Aurangzeb.

For a comparable portrait of Safi Khan from the Johnson Album compiled by Richard Johnson (1753-1807) now in the British Library, formerly in the India Office Library, see, T. Falk and M. Archer, Indian Miniatures in the India Office Library, London, 1981, no. 123 (iv). Also see, Emily, Hannam, Eastern Encounters, Four Centuries of Paintings and Manuscripts from the Indian Subcontinent, The Royal Collection Trust, London, 2018, nos. 35 and 36.

Provenance

The Ibbetson Collection

The interesting inscription on the reverse of the painting connects the portrait to the Ibbetson family and possibly Sir Denzil Charles Jelf Ibbetson KCSI (18471909). The Ibbetson family moved to Australia where Sir Denzil spent part of his early life before arriving at Cambridge to take a second degree in mathematics at St John’s College. In 1870, he arrived with his bride Louisa Coulden in India, taking up a post in the Punjab. In his later career he served as Chief-Commissioner of the Central Provinces and Berar from 1898-1899. He was appointed LieutenantGovernor of the Punjab in 1907 and made a Knight Commander of the Order of the Star of India (KCSI) in the 1903 Durbars Honours List. During his time in India, he made a significant contribution to the understanding of the Indian census and caste system. He died in London, in 1909.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank Margaret Erskine for writing this article on the present miniature painting.

56 Inscription on the reverse

22

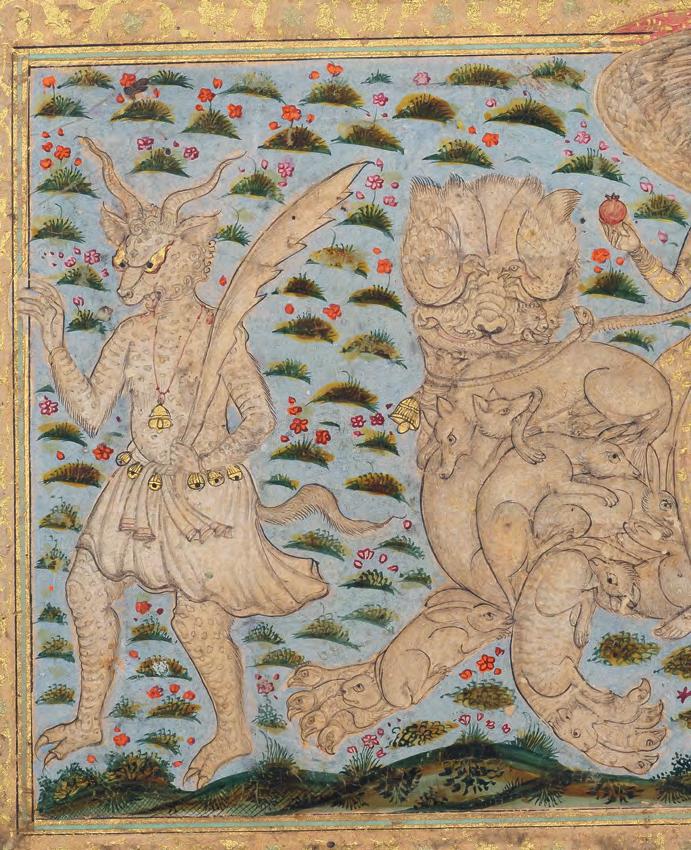

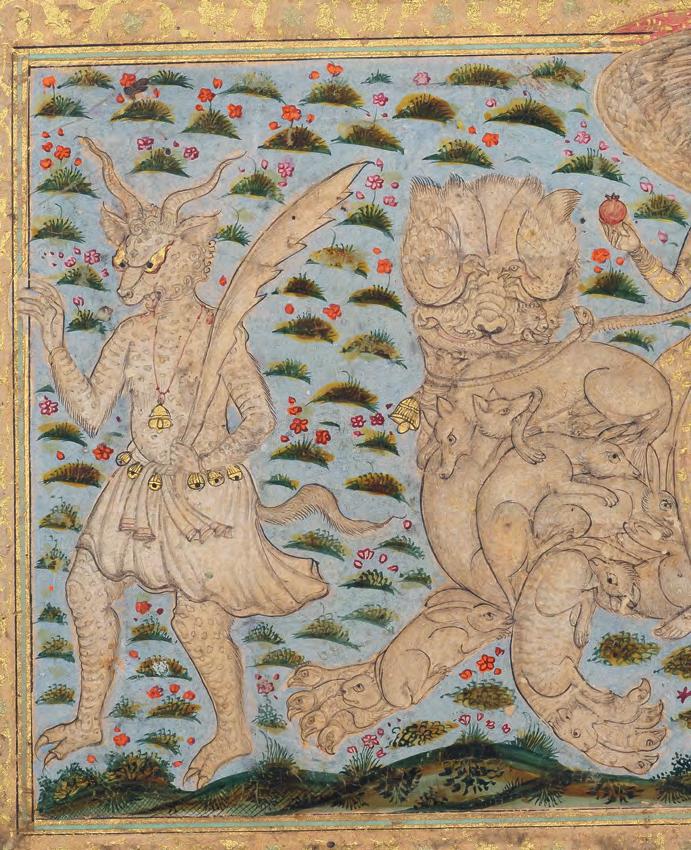

ALBUM FOLIO WITH A YOUTHFUL COURTIER WEARING A SAFAVID STYLE TURBAN AND A COMPOSITE LION

Deccan

Late 17th Century

Dimensions: 32 x 19 cm.

The square seal on the margin: Navvab Nasiri Sayyidi Dara Ali Bahadur

1231 A.H. (1815 C.E.)

A youthful courtier standing in a landscape, wearing a striped Safavid-style turban and a fur-trimmed floral coat over an orange jama, trees in the background, gouache on paper; verso an angel astride a composite lion made up of animals and birds led by a horned demon, drawing on paper, mounted on an album page with gilt-decorated borders and panels of nasta’liq calligraphy.

This Deccani miniature painting is an excellent example of the connections between the courts of the Deccan and Safavid Iran and the influence particularly on Deccani artists. Shah Abbas the Great of Iran moved his capital to Isfahan in 1598 establishing an important political and cultural centre frequently visited by the ambassadors of Europe and Asia, leading to a major dialogue in the seventeenth century between the continents, including at the end of the seventeenth century a brief period between Iran and Golconda in the Deccan. By turn Persian artists including Sheikh Abbasi and his sons Ali Naqi and Muhammad Taqi were influenced by Mughal and Deccani artists working in the Deccani studios. The Deccan was rich with mines of gems and cotton growing areas, enriching wealthy patrons who would have commissioned such a likeness as this youth wearing a turban taken from across the seas and lands of Safavid Iran.

Composite subjects are not uncommon in Indian miniature painting and jangling bells, horned-figures are frequently taken from Iranian inspired iconography. Demons (divs) often appear in Persian literature with composite figures as in Nizami’s Tale of the Turquoise Pavilion.

The angel riding the composite lion appears to be a pari, winged creatures renowned for their beauty. The word pari originates from Middle Persian, “parig”, and the root “par ”, which means wing. The iconography of ‘a pari riding a lion’ has a strikingly similar reflection in Western art: ‘a winged Dionysus riding a lion’. A famous example is a mosaic detail, from the House of the Faun in Pompeii. The pari holds a pomegranate, a symbol of fertility, abundance and prosperity in Persian, Turkish and Indian culture. Pomegranates are still broken in the new year as a sign of hope for prosperity.

Further Reading

E. Sims, Five Seventeenth Century Persian Oil Paintings, P&D Colnaghi & Co Ltd Exhibition Catalogue, London, 1976, |pp. 223-232.

M. Zebrowski, Deccani Painting, London, 1983, p.195.

T. Falk and M. Archer, Indian Miniatures in the India Office Library, London, 1981, pl. 7, p. 76, no 68f.21v and p. 220, N. N. Haidar and M. Sardar, Sultans of Deccan India 1500-1700, New York, 2015, p. 23, p.291, pl. 168.

E. Hannam, Beyond the Page, London, 2023, Nos. 19 and 20.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank Margaret Erskine for writing this article on the present miniature painting.

Provenance

Navvab Nasiri Sayyidi Dara Ali Bahadur 1231 A.H. (1815 C.E.) (His square seal is stamped on the margin).

Private UK Collection.

58

Shiraz, Persia

Second Half of the 16th Century

Dimensions: 26.2 x 17 cm.

Opaque pigments heightened with gold on paper.

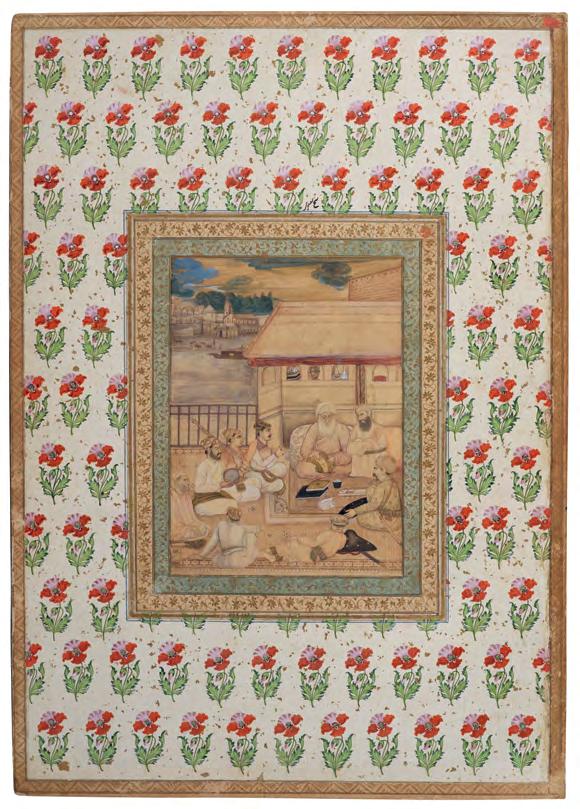

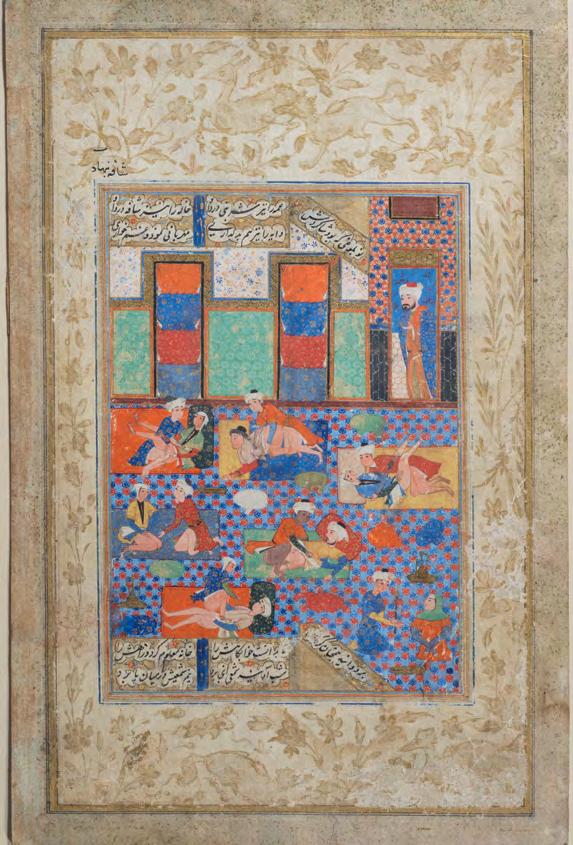

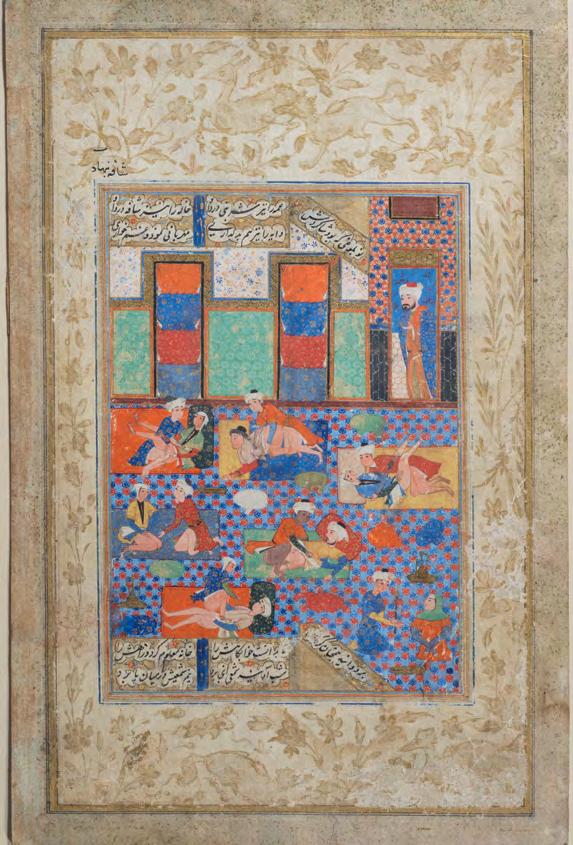

AN EXTREMELY RARE EROTIC ILLUSTRATION OF A POEM BY SA‘DI SHIRAZI (D. 1292 CE)

Ink and opaque pigments heightened with gold, depicting lovers including a figure in a distinctive black hat, in various coupling positions in a brightly coloured and patterned tile interior, with two lines of Persian nasta’liq above and below within cloud bands on a gold ground, and diagonal line of the same above and below, outer border decorated in gold with animals on a floral ground.

Ostensibly, this single folio was part of a manuscript of the collected works (Kulliyāt) of the renowned Persian poet and mystic, Sa`dī of Shiraz (d. 1292 CE). The painting is partially framed by five couplets that belong to a short narrative poem (masnavī) that is found in the little-studied and unpublished collection of Sa`dīs obscene works (khabīsāt), which are featured prominently in the earliest manuscripts of the Kulliyāt (please see, D. Inge`Aesthetics of Desire in Medieval Persian Poetry).

The poem, which comprises seventy couplets, recounts the story of a handsome young man who marries an uncomely and ill-mannered woman. Upon experiencing an erotic fiasco during their first night together, the young man begs his father-in-law to allow him to divorce his wife. The father rejects this request by telling the young man that he would have to spend time in jail in order to pay back his daughter’s dowry. After thinking at length about his miserable condition, the young husband resorts to the uncanny

expedient of seducing and sexually subjugating his wife’s entire family and entourage, without discriminating between women and men of any age. Being the only family member who has not been assaulted by the young man, the father consents to the divorce of the couple with no further hesitation. The five couplets quoted in this folio pertain to the central part of the poem, which offers a detailed description of the orgiastic spree undertaken by the young man. As is often the case with Sa`dī’s obscene works, in these lines, explicit descriptions of sexual acts are juxtaposed with delicate similes and metaphors that are drawn from the poet’s inimitable lyric style.

Whereas the poem, line by line, offers a list of the young man’s sexual encounters with the members of his wife’s family in chronological order, the painting portrays all of them simultaneously. The young husband occupies a different timeframe in each section of the painting. While his physical features appear to be always the same, different erotic settings are distinguished by different garments.

At the centre of the painting, as a variation of the erotic scenes, the young husband appears to have a darker skin colour. Moreover, instead of having sex with a beardless male or female youth, the darker boy seems to be penetrating a bearded man. A man with similar facial features and hair appears on the top right of the painting. One could assume that this adult male is the visual depiction of the young man’s father-in-law who, in the versified plot, fears the sexual intentions of his daughter’s husband after having been made aware of the erotic tumult he has brought to his family.

Stylistic features of this painting suggest that it was produced in Shiraz between the 1560s and the 1570s CE. Visual representations of Sa`dī’s erotic verses (and, in general, of obscene poetry) are extremely rare before the 17th century. Nonetheless, a manuscript of Sa`dī’s Kulliyāt copied in Shiraz in 1566 (British Library, Add. 24944) presents a painting that is similar to the present one and illustrates exactly the same erotic poem.

A second related miniature from a Kulliyat-i Sa‘di, dated 939/1532 (Topkapi Palace Museum Library, R. 926, Fol. 22b), is published in Lale Uluc’s Turkman

62

23

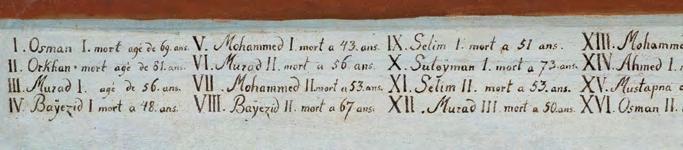

Governors, Shiraz Artisans and Ottoman Collectors: Sixteenth Century Shiraz Manuscripts, Turkiye Isbankasi Publications, Istanbul, 2006, p. 219.