with Kentucky Explorer

College Majors Penned Literary Contest Winners

with Kentucky Explorer

College Majors Penned Literary Contest Winners

joins Crystal Wilkinson, Naomi Wallace, Ron Eller and David Dick as the 2025 Kentucky Writers Hall of Fame Inductees

Located in the heart of eastern Kentucky, Morehead State University ranks among the best public universities in the South. We’re recognized for our outstanding academic programs including business, education, nursing, and space systems engineering.

See for yourself why MSU is a top-ranked university. Schedule a visit or apply today!

Test your knowledge of our beloved Commonwealth. To find out how you fared, see page 6.

1. How many states are included in the region called Appalachia?

A. 9

B. 11

C. 13

2. Which Kentucky county is the farthest west in Central Appalachia?

A. Edmonson

B. Pulaski

C. Barren

3. True or False: In February 1964, Fred Hastings, a skydiver from Louisville, survived a 5,500-foot plunge to Earth despite the failure of his parachute.

4. Jackson Whipps Showalter, known as “The Kentucky Lion,” was a fivetime United States champion in which game?

A. Backgammon

B. Chess

C. Texas Hold ’em Poker

5. In February 1981, more than 13 miles of Louisville sewer lines exploded when what chemical was released into the system?

A. Kentucky moonshine

B. Sodium phosphate

C. Hexane

6. When Owen County native Abraham Owen Smoot died in 1895, his funeral was called the “most impressive witnessed in Pioneer Utah.” He was survived by two of his six wives and 17 of his 24 children. He was second mayor of Salt Lake City and an active leader in which religion?

A. Seventh Day Adventists

B. Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

C. Jehovah’s Witnesses

7. Abraham Owen Smoot’s greatuncle Abraham Owen (1769-1811), the namesake of Owen County and Owensboro, died at the Battle of Tippecanoe during which war?

A. French and Indian War

B. American Revolution

C. War of 1812

8. Paducah’s Imogene Audette Burkhart, a singer, dancer and actress, played the mother on which popular 1960s television series?

A. The Patty Duke Show

B. The Many Loves of Dobie Gillis

C. Gidget

9. Billie J. Farrell, the first woman to command the U.S.S. Constitution, is from which Western Kentucky city known as Atomic City?

A. Hopkinsville

B. Paducah

C. Henderson

10. Jackson County native Ezra Allen Miner (1847-1913)—also known as Bill Miner, the Gentleman Robber or Gentleman Bandit—is credited with which phrase related to robbery?

A. “Reach for the sky”

B. “Show me the money”

C. “Hands up”

© 2025, VESTED INTEREST PUBLICATIONS VOLUME TWENTY-EIGHT, ISSUE 1, FEBRUARY 2025

Stephen M. Vest Publisher + Editor-in-Chief

Hal Moss Associate Publisher + Business Editor

EDITORIAL

Patricia Ranft Associate Editor

Rebecca Redding Creative Director

Deborah Kohl Kremer Assistant Editor

Ted Sloan Contributing Editor Cait A. Smith Copy Editor

Jackie Hollenkamp Bentley, Jack Brammer, Bill Ellis, Steve Flairty, Gary Garth, Jessie Hendrix-Inman, Mick Jeffries, Kim Kobersmith, Brigitte Prather, Walt Reichert, Tracey Teo, Janine Washle and Gary P. West

BUSINESS AND CIRCULATION

Barbara Kay Vest Business Manager

Katherine King Circulation Assistant

ADVERTISING

Lindsey Collins Senior Account Executive and Coordinator

Kelley Burchell Account Executive

Laura Ray Account Executive

Teresa Revlett Account Executive

For advertising information, call 888.329.0053 or 502.227.0053

KENTUCKY MONTHLY (ISSN 1542-0507) is published 10 times per year (monthly with combined December/ January and June/July issues) for $25 per year by Vested Interest Publications, Inc., 100 Consumer Lane, Frankfort, KY 40601. Periodicals Postage Paid at Frankfort, KY and at additional mailing offices.

POSTMASTER: Send address changes to KENTUCKY MONTHLY, P.O. Box 559, Frankfort, KY 40602-0559. Vested Interest Publications: Stephen M. Vest, president; Patricia Ranft, vice president; Barbara Kay Vest, secretary/treasurer. Board of directors: James W. Adams Jr., Dr. Gene Burch, Gregory N. Carnes, Barbara and Pete Chiericozzi, Kellee Dicks, Maj. Jack E. Dixon, Bruce and Peggy Dungan, Mary and Michael Embry, Judy M. Harris, Greg and Carrie Hawkins, Jan and John Higginbotham, Frank Martin, Bill Noel, Walter B. Norris, Kasia Pater, Dr. Mary Jo Ratliff, Randy and Rebecca Sandell, Kendall Carr Shelton and Ted M. Sloan.

Kentucky Monthly invites queries but accepts KENTUCKYMONTHLY.COM

Regarding Bill Ellis’ article “What’s in a Name” (August issue, page 57), I have been searching for my “self” as long as I can remember.

Born in post-World War II France of a Huguenot mother (French) and a Jewish father (American). As far as I can tell, I am the only one through my generation who has attended college.

I spoke French at home, with some English on the playground, at school and at my friends’ homes.

At age 3, my father and mother brought me from France to the United States—Brooklyn Heights, specifically—where we lived for a year. We moved to West Babylon, New York, when I was 4 and to Memphis, Tennessee, when I was 10.

Language has always been

interesting and somewhat stressful to me, having been mocked as having a French accent in West Babylon, a New York accent in Memphis, a Southern accent at Harvard University, and an American accent in London. Somehow, I’ve acquired a “standard English” accent, which means that I belong nowhere and everywhere, at least within the U.S. Currently, no one can tell where I come from, a problem I have about others as well. For as a long time, I thought my name was Richard, pronounced “Ree’shar,” as they do in France and as my mother called me.

Is there, or should there even be, a consistent “I?” Aren’t we better off having “selves” that fit different environments (c.f. decoding, for example), or does this come at too high

a cost in the form of an unstable “true” self and the fear that we don’t know who we are or where we belong? Can psychology, through its scienceoriented perspective, help me determine who I am? Or am I fated to have multiple accents and roles reflecting not an “I” but rather a “them” we have labeled Richard—or Ree’shar, if you prefer.

Richard Lewine, Professor Emeritus Department of Psychological, and Brain Sciences University of Louisville

The photo of Merle and Cindy Heckman in the December/January issue, page 9, should have been labeled Zimbabwe, as Victoria Falls is located in that country.

We Love to Hear from You! Kentucky Monthly welcomes letters from all readers. Email us your comments at editor@kentuckymonthly.com, send a letter through our website at kentuckymonthly.com, or message us on Facebook. Letters may be edited for clarification and brevity.

Kentucky Monthly’s annual gift guide highlights some of the finest handcrafted gifts and treats our Commonwealth has to offer.

Even when you’re far away, you can take the spirit of your Kentucky home with you. And when you do, we want to see it!

“I am a Kentucky girl [from Lincoln County] currently living in the [Florida] panhandle,” Yvette (Greer) Maher writes, “but Kentucky Monthly always brings me home.”

Lauren and Chip Jones of Nashville celebrated their nuptials at Walt Disney World’s Swan Resort, with Lauren’s daughter, Madison (center, with magazine), and friends and family, including the bride’s parents, Sue-Sue and Steve Hartstern (far left), who live in Louisville.

Bill and Karen Mallonee of Owensboro, together with their children and grandchildren, took a trip to Maui to celebrate some milestone birthdays. Bill is shown here taking Kentucky Monthly to the top of 10,000-plus foot Haleakala for the view.

Lauren Green, right, who grew up in Mount Sterling and now resides in Texas, is pictured with her mother, Susan Webb, of Mount Sterling. They traveled to Nuremberg, Germany, where Lauren’s dad and Susan’s husband, Jim Webb, was stationed in nearby Bayreuth in 1969. More than 50 years later, Susan enjoyed showing Lauren the sites of the area, including their old house.

and

of Lexington visited Shanghai, China, while enjoying a Viking cruise.

Chuck Wolfe of Frankfort traveled to London and Vienna with son Zack Wolfe and grandson Harvey, who live in Manchester, Maryland. Chuck and Harvey are pictured with London’s famed Big Ben in the background.

Barbara Schmall, center, with her daughter, Anna Pray, and son Peter Kremer, all of Louisville, are pictured in Seville, Spain, at the Plaza de España.

Take a copy of the magazine with you and get snapping! Send your high-resolution photos (usually 1 MB or higher) to editor@kentuckymonthly.com or visit kentuckymonthly.com to submit your photo.

1. C. Appalachia includes 423 counties across 13 states, from Southern New York to Northern Mississippi; 2. A. Of Kentucky’s 54 Appalachian counties, Edmonson is the westernmost, while Panola County, Mississippi, is the westernmost overall; 3. True. His reserve chute caught enough air to slow his speed to 50 miles per hour before he crashed into a rain-soaked Indiana field; 4. B. The Mason County (Minerva) native won five chess championships between 1890-1909; 5. C. Hexane fumes were ignited by a tailpipe near the corner of 12th and Hill streets and rippled back to the Ralston-Purina Plant, sending manhole covers flying around the University of Louisville; 6. B. The Mormons; 7. C. Owen County, Indiana, also is named in his memory; 8. A. Burkhart, who changed her name to Jean Byron in Hollywood, played Natalie Lane from 1963-1966; 9. B. Farrell, a graduate of the U.S. Naval Academy, is from Paducah; 10. C. Miner, credited with British Columbia’s first train robbery, urged his gang members be polite and avoid killing anyone if at all possible.

For the first time, students in Kentucky can pursue careers in jobs like fashion designer and graphic novelist at an art college in the Bluegrass State that has been fully accredited.

The Kentucky College of Art + Design at 505 West Ormsby in downtown Louisville received accreditation status from the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools Commission on Colleges in December to award baccalaureate degrees. The action came seven years after the institution voted to separate from Spalding University with the goal of achieving accreditation.

their degrees more valuable and can help them in obtaining federal aid,” said Moira Scott Payne, president of the private, four-year nonprofit that received $5 million from the state last year.

Tuition at Kentucky College of Art + Design is about $30,000 a year. Twenty-nine students attend the college. Payne expects that number to increase. She said the college plans to secure a new campus in downtown Louisville.

For more information about the college, visit kycad.org

“Accreditation is significant for the students. It makes

The University of Louisville has announced author Mark Warren as the 2025 Grawemeyer Award for Education recipient. The University of Massachusetts Boston professor garnered the award for his book, Willful Defiance: The Movement to Dismantle the School-to-Prison Pipeline

The book details how grassroots organizing led to important declines in exclusionary discipline and more recent reforms to eliminate policing practices in schools.

“I’m honored to receive this award, and particularly gratified to see community-engaged scholarship recognized with the highest merit,” said Warren. “I thank my community partners, Black and Brown parents, students and community organizers, who worked with me to produce this book as part of a movement for educational justice.”

— Jack Brammer

The University of Kentucky’s College of Communication and Information just received a significant financial shot in the arm. Misdee Wrigley Miller, the owner of Kentucky-based Wrigley Media Group and LEX Studios, has gifted $2.5 million to help expansion and renovations for the college’s future home at Pence Hall.

“These innovative spaces will provide students the opportunity to not only learn but gain real-world experience, strengthening our state’s workforce and potentially boosting the economy of our community,” said UK President Eli Capilouto

The $32 million project will feature five classrooms, an auditorium, a seminar room, two computer labs, and various studios and gathering spaces. Construction is underway with an anticipated completion in summer 2025.

1 cooked chicken, boned + shredded (can stew chicken or use storebought rotisserie chicken)

2 tablespoons avocado oil

2 poblano peppers, seeded and diced

1 medium onion, diced

2 cloves garlic, minced

1½ teaspoons ground cumin

¾ teaspoon ground black pepper

1½ teaspoons chili powder

8 cups chicken broth or 2 32-ounce cartons low-sodium chicken broth or stock

1 14-ounce can diced tomatoes, undrained

2 tablespoons tomato paste

1/3 cup chopped cilantro, plus extra for garnish

6 fresh corn tortillas, cut into strips

Shredded colby jack cheese or cotija cheese, for garnish

Salsa verde, for garnish

1. Stew chicken in a Dutch oven over medium heat until cooked. Internal temperature should be 165 degrees. Strain chicken broth/stock, if desired. Skin, bone and shred chicken and return it to Dutch oven.

2. Heat avocado oil in a skillet and sauté peppers, onion and garlic.

3. Add sautéed vegetables, cumin, black pepper, chili powder, chicken broth, tomatoes, tomato paste and cilantro to pot with chicken.

4. Bring mixture to a boil over medium heat. Reduce heat to medium low, cover and simmer 30-45 minutes for flavors to blend.

5. Serve with selection of garnishes.

Note: I stew my own chicken and use the stock to make the soup.

In a month where the heart is the focus, these recipes feature ingredients to help keep your heart healthy—fresh fruit, lean proteins, healthy fats, whole grains, fiber, herbs and spices. These dishes prove that you don’t have to sacrifice flavor when eating healthy foods. — Merritt Bates-Thomas

Owensboro’s Merritt Bates-Thomas is a registered dietitian nutritionist (RDN) who has been sharing recipes with a healthier twist on WBKR-FM 92.5’s What’s Cooking since 2017. In May 2023, she joined ABC 25 Local Lifestyles to share recipes and tips for flavorful cooking. She also appears on CW7’s Daybreak Extra ’s “Joe’s Kitchen.” You can follow her on Instagram @thekitchentransition.

SERVES 4-6 SERVINGS

1½ pounds pork tenderloin

1 tablespoon extra-virgin olive oil + 2 tablespoons olive oil

1 teaspoon sea salt, or to taste

½ teaspoon black pepper, freshly ground

2 teaspoons Italian seasoning

2-3 cloves garlic, minced, or 1½ teaspoons garlic powder

Quinoa Pilaf

1 tablespoon olive oil

1 cup uncooked quinoa

1 large shallot, finely chopped

1 stalk celery, thinly sliced

1 clove garlic, minced

2 cups water

1 teaspoon salt

1 tablespoon fresh parsley, finely chopped

2 tablespoons pine nuts, optional

1. Preheat oven to 350 degrees with the rack positioned in the middle.

2. Trim tenderloin of fat and any silver skin and pat dry with a paper towel. Pierce tenderloin all over with a fork and rub with 1 tablespoon extra-virgin olive oil.

3. Combine salt, pepper, Italian seasoning and garlic or garlic powder. Sprinkle the mixture onto the tenderloin, then use your hands to rub the seasonings into the tenderloin until evenly coated.

4. Heat 2 tablespoons olive oil over medium-high heat in a large oven-safe pan (cast iron or a Dutch oven will work). Once oil is hot, add pork and brown on all sides (6 minutes total).

5. Bake uncovered for 20-25 minutes, flipping tenderloin over halfway through baking, until the center of the pork reaches an internal temperature of at least 145 degrees.

6. Transfer tenderloin to a cutting board and let meat rest for 5-10 minutes. Slice into medallions.

7. While the pork is cooking, rinse quinoa if instructed to do so on the box. If it recommends rinsing, place quinoa in a large sieve and rinse until the water runs clear. (Some brands don’t require rinsing.)

8. Heat 1 tablespoon olive oil on medium-high heat in a 1½- to 2-quart pot. Add shallot, celery and garlic, stirring occasionally until the chopped shallot is translucent but not browned.

9. Add quinoa and cook, stirring occasionally for a couple more minutes. You can let some of the quinoa get a little toasted.

10. Add water and salt. Bring to a boil and reduce the heat to low so that the quinoa and water are simmering while the pot is partially covered (enough to let out some steam). Simmer for 20 minutes or until quinoa is tender and the water has been absorbed. Remove from heat and stir in parsley and pine nuts, if using.

11. Spoon quinoa onto a serving platter and fluff up with a fork. Arrange pork medallions over quinoa before serving.

YIELDS 12 MUFFINS

1 cup carrots, peeled and grated

1 cup unsweetened applesauce

2 large eggs

¼ cup canola oil

2 teaspoons vanilla

1/3 cup light brown sugar

1 teaspoon baking powder

½ teaspoon baking soda

½ teaspoon salt

1 teaspoon cinnamon

½ teaspoon ground nutmeg

¾ cup all-purpose flour

½ cup whole wheat flour

¾ cup rolled oats

1/3 cup chopped walnuts, plus extra for topping, optional

1. Preheat the oven to 350 degrees. Line a standard 12-muffin tin with paper liners or grease with oil.

2. To a large bowl, add carrots, applesauce, eggs, oil, vanilla and brown sugar. Whisk together well.

3. Add baking powder, baking soda, salt, cinnamon and nutmeg to the carrot mixture. Whisk again to incorporate ingredients.

4. Add the flours and rolled oats to the bowl. Stir until just combined. Do not overmix, as this can result in dense muffins.

5. Fold walnuts (if using) into the batter.

6. Spoon batter into the 12 prepared muffin cups, filling about ¾ of the way. Top with additional walnuts, if desired.

7. Bake until the tops of the muffins are golden brown and a toothpick inserted into the center comes out clean, 20-25 minutes.

8. Allow muffins to cool in pan for 15 minutes before enjoying. Once cooled completely, store in an air-tight container in the fridge for 4-5 days or in your freezer for up to a month.

6 clementine oranges, peeled and separated into segments

2 apples, cored and sliced

2 pears, cored and sliced

1 large pomegranate, seeded

4 kiwis, peeled and sliced

3 tablespoons honey

2 tablespoons fresh lime juice from 1 medium lime

2 tablespoons fresh lemon juice from 1 medium lemon

2 tablespoons fresh clementine juice from 1 clementine

1. Wash all fruit well before peeling and cutting.

2. Mix together oranges, apples, pears, pomegranate and kiwis in a medium serving or mixing bowl.

3. Combine honey and citrus juices until well blended. Pour over the fruit and toss the mixture gently with a spoon to coat evenly.

4. Refrigerate until serving.

Naomi Wallace , who was born and raised in Louisville, is only the second American playwright to have a work added to the permanent repertoire of Comédie-Française, the 300-year-old French National Theatre. The other is Tennessee Williams . While Wallace’s work is better known in Europe and the Middle East than in America, that soon may change.

Frank X Walker and Crystal Wilkinson are two founding members of the Affrilachian Poets, an influential group of artists who highlight the often-ignored history and culture of rural Black people in Kentucky. Both have received national acclaim for their work.

Ron Eller was the first member of his Appalachian family to go to college, and when he studied history, he realized that his people’s history had been ignored. His career at the

University of Kentucky and his landmark 2008 book Uneven Ground: Appalachia Since 1945 have focused on changing that.

These four writers will be inducted into the Kentucky Writers Hall of Fame along with the late David Dick, who returned to Bourbon County after two decades as a CBS News correspondent to write 14 books, most about his beloved Kentucky.

The ceremony, which is free and open to the public, will be March 10 at the historic Kentucky Theatre in downtown Lexington. All four living inductees and Dick’s family plan to attend.

Learn more about these Kentucky literary icons in this special section, written by Tom Eblen , a former Lexington Herald-Leader columnist and managing editor who is now the literary arts liaison at the Carnegie Center for Literacy & Learning in Lexington.

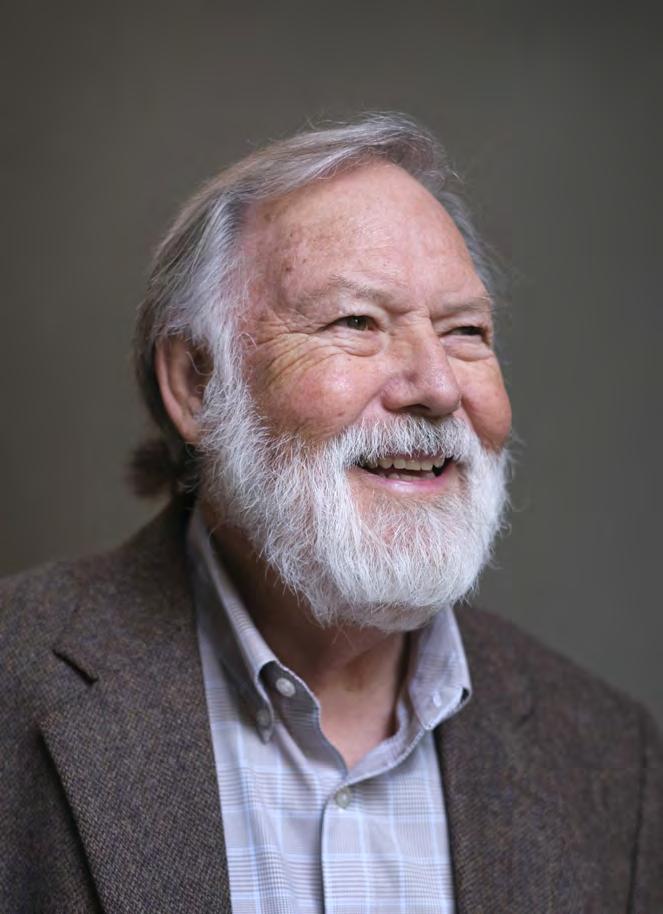

Frank X Walker was approaching middle age when he finally acknowledged his calling as a writer.

Walker, 63, had been writing since he was a boy, creating his own comic books. The whole time he was earning a living as a salesman, a visual artist and an arts administrator, he spent his free time writing poems and stories.

“But I never dreamed about being a writer,” he said in an interview. “What little I knew about writing convinced me that I wouldn’t eat, that it was a poor choice of professions.”

Walker eventually changed his mind. He is now a creative writing professor at the University of Kentucky and the author of 13 poetry collections and a children’s book. He has adapted his work for the stage, edited two poetry collections, and helped create educational and video resources for public television.

Walker received the Lannan Literary Fellowship in Poetry in 2005, and in 2013-2014, he became Kentucky’s first African American poet laureate. He received the NAACP Image Award for Poetry in 2014, the Lillian Smith Book Award in 2004, the Thomas D. Clark Literary Award for Excellence in 2006 and many other honors. He is the founding editor of pluck! The Journal of Affrilachian Arts & Culture .

Born Frank Wesley Walker Jr. in Danville, he graduated from Danville High School, winning awards in creative writing and visual art. But when he enrolled in the University of Kentucky, he majored in electrical engineering. It seemed like a good career path, but he soon realized he had no passion for it.

Walker sat out a semester of classes because a business he started that sold paraphernalia to fraternities and sororities was doing so well that he didn’t have time for both. When his mother found out, she shamed him into returning to UK. He switched his major to journalism and later to English. His passion was writing.

“I took every creative writing class I could,” said Walker, who studied under then-UK professor Percival Everett, whose novel James won the 2024 National Book

Award, and Gurney Norman, a 2019 Kentucky Writers Hall of Fame inductee.

“Gurney was the best writing teacher and humanitarian and community activist model for me that I could have possibly had,” Walker said. “Being in Gurney’s orbit, he had me reading so much. He really invested in my development as a literary person.”

As an undergrad, Walker wore eyeglasses like Malcolm X, whom he once portrayed in a play. “I also had hair then,” he said. “I had a certain political edginess about me, and all my friends just called me X. It was an honor.” He started using Frank X Walker as his pen name and eventually changed his name legally.

After graduation, Walker said the Knoxville News Sentinel wanted to hire him as a feature writer, but he felt uneasy about becoming that newsroom’s only Black journalist. Instead, he accepted an offer to direct UK’s Martin Luther King Jr. Cultural Center.

“By this time, I had started thinking of myself as a writer—not a poet, but a writer,” Walker said. “And then Nikky Finney showed up.”

Finney, who won the National Book Award for poetry in 2011, came to UK in 1989 as a visiting writer and then spent two decades on UK’s English faculty. She was inducted into the Kentucky Writers Hall of Fame in 2021.

Finney and several other local Black writers started gathering with Walker at the cultural center on Monday evenings to talk about writing and share their work. The group evolved into the Affrilachian Poets, which took its name from Walker’s first book of poetry, Affrilachia (Old Cove Press, 2000). He coined the word to describe the rich but often-ignored history and culture of Black people in Appalachia.

Walker still wasn’t ready to call himself a writer. The cultural center job set him on a career path in arts administration. He went to Purdue University to serve as assistant director of its Black cultural center, then returned to Kentucky to become vice president of the Kentucky Center for the Arts and director of the Governor’s School for the Arts.

“All that work at the governor’s school helping other

people realize their artistic output … reminded me how comfortable I was in that space,” he said. “I was a good administrator, but it also woke up the artist in me.”

Walker had written two books of poetry by this time, “but I knew I had more books in me.” He also knew that if he wanted a university teaching job, he would need at least a master of fine arts degree. Spalding University in Louisville was then starting what has become an acclaimed lowresidency MFA program in creative writing, and Walker was in its first graduating class, as were

Crystal Wilkinson and Silas House

Eastern Kentucky University hired Walker and House to start a creative writing MFA program there, but neither stayed long. Walker won the $75,000 Lannan Literary Fellowship, giving him enough money to write for a time. Then he took part-time teaching jobs at the University of Louisville and Transylvania University before joining Northern Kentucky University’s faculty.

In 2010, UK recruited Walker to teach in its Africana Studies program. He has been there ever since as a professor of Africana studies and creative writing. His wife, Dr. Shauna M. Morgan, is a poet and associate professor in those programs.

“Teaching also was something I never dreamt of doing,” Walker said. “But because I had great teachers, I think I passively learned what a good teacher was. Today, I think I’m a better teacher than a writer.”

Much of Walker’s poetry involves telling the history of Black Kentuckians through poetry, a story form exemplified in his latest book, Load in Nine Times (Liveright/ W.W. Norton, 2024). Its poems are narratives about slavery, the Civil War and Reconstruction based on historic artifacts of Black Kentuckians. The Frazier History Museum in Louisville is exhibiting 18 of those poems with artifacts that inspired them in its exhibit The Commonwealth: Divided We Fall

For Walker, studying history is a way of understanding the present. He thinks a good poem evokes emotions in readers—and leaves them with a memorable punch at the end. “It’s really important to me that the reader feel something,” he said.

Walker has spent years writing and rewriting a novel he hopes to publish eventually. He also is finishing two poetry manuscripts. One is about a century of racism through the lens of golf. The other is a third book about York, an enslaved African American who accompanied Meriwether Lewis and William Clark on their “Voyage of Discovery” through western North America from 1804-1806.

“After decades of believing that I wanted to be something else—even though I was already writing and making art—I thought that pursuing a dream meant it had to be hard, “ Walker said. “Writing was always easy for me. It was pleasure; it was not work.”

When Crystal Wilkinson was growing up on her grandparents’ farm in Casey County, there were no playmates nearby. So, she would walk to Indian Creek, talk to the minnows, and imagine what they might be thinking. Or she would climb the knob behind the house, look far into the distance, and wonder if another little girl somewhere was doing the same thing.

“Books became my companions,” she said in an interview. “As I was roaming around, I was thinking about stories. My grandmother always read to me. I could read before I went to school, and I loved reading and loved writing. I was always living in the mind, and I always had a notebook with me.”

Those early experiences have informed Wilkinson’s

career as a poet, short-story writer, novelist, essayist, creative writing professor and poet laureate of Kentucky (2021-2022). She was a founding member of the Affrilachian Poets, whose goal was to explore the rich history of Black culture in rural Kentucky that often has been ignored.

Wilkinson’s fifth book, Praisesong for the Kitchen Ghosts: Stories and Recipes from Five Generations of Black Country Cooks, made many lists of national best-sellers and best books in 2024. Her 2021 poetry collection, Perfect Black, won her the NAACP Image Award for Poetry. She has received many awards for her 2016 novel, The Birds of Opulence, and her earlier short story collections, Water Street and Blackberries, Blackberries

Wilkinson, 62, was born in Hamilton, Ohio, but spent

most of her childhood with her grandparents because of her mother’s mental illness. She loved writing and art but took high school classes in typing and shorthand because it seemed like a good path to a job.

She earned an art scholarship to Eastern Kentucky University, but art history classes bored her. “So, I majored in journalism and took all the creative writing classes Eastern had to offer,” she said.

After graduation and a brief career as an accounts receivable supervisor for a window-replacement company, Wilkinson landed a job writing obituaries and news notes for the Lexington Herald-Leader. She later became a public information officer for the city.

“I always had creative writing on the side,” she said. “I was so fascinated by the Carnegie Center—this idea of going from literacy to literary. I would run over from the city [office] on my lunch hour and sit in on [writer and artist] Laverne Zabielski’s class, do some free writing, and come back.”

Wilkinson became involved with the Affrilachian Poets, attended local readings, and went to the Appalachian Writers Workshop. While working in public relations at Midway College (now Midway University), she was accepted into a prestigious Hurston/Wright Foundation workshop in Virginia. She needed help with transportation there, so the college president loaned her his official Cadillac—“the biggest car I’ve ever driven.”

At that workshop, Wilkinson met her first agent, Marie Brown, who had worked with renowned author Toni Morrison. Brown helped Wilkinson publish Blackberries, Blackberries, which came out when Wilkinson was working as assistant director of the Carnegie Center.

“I always thought success would be if I had a short story published in a magazine I had heard of,” she said. But Blackberries attracted the attention of several publishers interested in future work. “The fire had been lit,” she added.

Wilkinson had always thought she was too shy to teach, but after working at the Carnegie Center, “the teaching bug bit me very hard.” After earning an MFA in creative writing in Spalding University’s first low-residency class, she

taught at Berea College and then joined the University of Kentucky’s creative writing faculty.

Wilkinson and her husband, Ron Davis, a visual artist and poet, started Wild Fig Books & Coffee in Lexington. The store’s name comes from the work of reclusive Lexington novelist Gayl Jones, whom Wilkinson has long admired but never met. Wild Fig closed in September 2018 and reopened in November of that year as a worker cooperative.

Wilkinson sees all of her writing as connected, as if ideas are running a relay race from one book to the next. Her central theme is Black life in rural Kentucky.

“I think one of the preeminent jobs of the Kentucky writer is to hold the complications of our life up to the light, even to pay honor to that in some way,” she said.

“Mainstream America has a homogenized, wrong view about Kentucky. I feel like we’re constantly trying to hold our experiences, or the experiences of our people, up as if to say to the rest of the country, ‘See! This, too, is Kentucky.’ ”

Wilkinson does most of her writing in her home office, on the couch with a laptop, or outside in warm weather. Before she begins, she seeks inspiration from a poem or a passage from a writer she admires. She has a long list of favorites, including Jones, Nikky Finney (her best friend), Joy Harjo, George Ella Lyon and Michael Ondaatje

Wilkinson currently is writing a book called Heartsick about her mother’s mental health challenges, which Crown plans to publish in 2026. After that, she has another novel percolating, along with a collection of short stories. Ideas are never in short supply.

“For me, ideas are like a Rolodex; I’ve got ideas rolling all the time,” she said. “But it’s not until something haunts me that I can write about it.”

Many of Wilkinson’s books are dark, and after Heartsick, her goal is to write something lighter. “I really want to find my funny bone again,” she said. “I want to leave behind a nuanced look at Black people in rural Kentucky. I think what I’ve been put here to do is hold Kentucky up to the light—my Kentucky up to the light— for everyone else to see. Not so much to judge but to say, ‘This, too, is Kentucky.’ ”

Naomi Wallace, the daughter and granddaughter of Louisville journalists, knew early that writing was the best way for her to express herself and her values. But she thought it would be through poetry.

After graduating from Hampshire College in Amherst, Massachusetts, Wallace went to the University of Iowa for graduate work with the idea of becoming a poet. “I had always told myself that I didn’t like working with other people, that I wanted to work alone,” she said in an interview.

“And it was so wonderful to discover that I was wrong about myself,” she said. “I may have wanted that, but what I needed was collaboration. I’ve become a better writer through collaboration. And theater is one of the most collaborative arts.”

Wallace, 64, has become one of the most acclaimed playwrights of her generation, the author of more than two dozen plays and a long list of projects on her horizon. Those include finishing a trilogy of plays set in Kentucky and writing the book for two Broadway musicals: Coal Miner’s Daughter, the Loretta Lynn story (co-written with Greg Pierce); and Small Town, based on John Mellencamp’s work, especially his 1982 hit “Jack & Diane.”

Wallace’s many awards include a MacArthur Foundation “genius” grant in 1999, an Obie Award (for offBroadway and off-off-Broadway theater), the Susan Smith Blackburn Prize, the Fellowship of Southern Writers Drama Award, the Horton Foote Award, an American Academy of Arts and Letters Award in Literature and the inaugural Windham Campbell Prize for Drama.

Her most famous play is One Flea Spare, about a wealthy couple and two intruders quarantined together in 17th century London during the bubonic plague. The play, which explores the clash of social, cultural and sexual boundaries, was made part of the permanent repertoire of Comédie-Française, the French National Theatre. Wallace is only the second American so honored by the 300-yearold theater company, the other being Tennessee Williams One Flea Spare had its American premiere at the Humana Festival of New Plays at Actors Theatre of Louisville in 1996.

Wallace’s other well-known plays include The Trestle at Pope Lick Creek, Slaughter City and In the Heart of America. In

1995, she published a book of poetry: To Dance a Stony Field (Peterloo Poets).

Wallace was born in Louisville and grew up with five siblings on a farm near Prospect, as well as in Amsterdam, the hometown of her Dutch mother, Sonja de Vries. Her father, journalist Henry Wallace, later became a civil rights activist. Her grandfather, Tom Wallace, spent most of his career in top editing jobs at The Courier-Journal and the Louisville Times. An ardent conservationist, he led a fiveyear effort in the 1920s to prevent construction of a hydroelectric dam that would have destroyed Cumberland Falls. Then he helped preserve it as a state park.

For more than 20 years, Naomi Wallace has lived in North Yorkshire, England, with her British partner, Bruce McLeod, and their three children. Until the COVID pandemic, the family spent every summer at Moncada, the 660-acre Wallace family farm near Prospect, most of which is under conservation easements and can never be developed. Wallace said she doesn’t get to the farm as often now that her children are grown, but “it’s always an anchor, a place of creativity for me. It lives inside me.”

After the Kentucky Writers Hall of Fame ceremony on March 10, Wallace will head to New York for the opening of The Return of Benjamin Lay at the Sheen Center in Greenwich Village. She co-wrote the play with Marcus Rediker, an Owensboro-born historian. It is based on his 2017 book, The Fearless Benjamin Lay: The Quaker Dwarf Who Became the first Revolutionary Abolitionist. The one-person show premiered last year in London with the same actor, Mark Provinelli

Wallace said she loves collaborative writing. She co-wrote The Girl Who Fell Through a Hole in Her Sweater with McLeod and Returning to Haifa, an adaptation of Ghassan Kanafani’s 1969 novella, with Palestinian playwright Ismail Khalidi. She and Khalidi collaborated again on Guernica, Gaza: Visions from the Center of the Earth, which was produced last fall in the West Bank city of Ramallah.

Wallace’s work can be controversial. After commissioning Returning to Haifa, the Public Theatre in New York refused to perform it. But censorship often happens quietly in theater, Wallace said, when companies simply decide not to produce a play. “While my work has been highly awarded, I’m not a highly produced playwright,” she said.

“For me, it’s not just about art,” Wallace said of her writing. “It’s about art as a part of envisioning a better world, a more just world. Artists have at times been on the front line of what they call speaking truth to power. Artists have also been the shock troops for colonialism and war. So, it really depends on who the artists are and their vision of what the world should be and how power should be shared.”

While she has long had a close relationship with Actors Theatre of Louisville, she said a former artistic director refused to perform a play it had commissioned because of fear that its references to the pharmaceutical industry might offend a corporate sponsor. That play—now titled The Breach, about a group of teenagers in 1970s Kentucky who reconnect in the 1990s—also includes content about sexual violence that she describes as “challenging.”

The Breach’s premiere was in France, translated into French, and it has been performed in London. But Wallace hopes to see it staged in Kentucky someday, along with two other plays—one she has written and another she plans to write this summer—that she refers to as her Kentucky Trilogy.

“Growing up in Kentucky and listening to people talk, that’s what gave me the foundation for the language I use

in the theater,” she said. “Someone was asking me, ‘Kentucky meant so much to you. Why did you leave?’ I said, ‘I’ve never left. I live in England, but I’ve never left Kentucky.’ The most powerful time for me about Kentucky was when I was a teenager. That is right there, all the time, with me.”

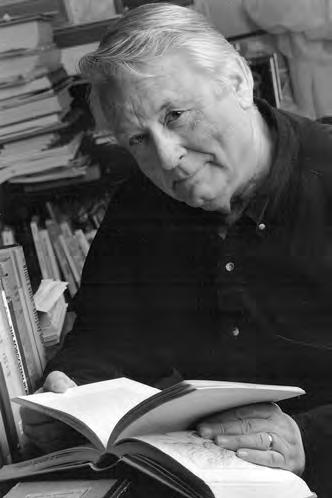

Ron Eller’s German and English ancestors were in Appalachia by the mid-1700s, and his Cherokee ancestors were there for millennia before that. As the first member of his family to go to college when he studied at the College of Wooster in Ohio in the 1960s, Eller was puzzled by his Southern history class.

“We haven’t studied anything about my people,” Eller told his professor. “My people didn’t own plantations and slaves.”

Instead of a paper on the plantation system, the professor assigned him to find out what had been written about Appalachian history. “I went to the library and could find absolutely nothing,” Eller said. Well, except for references to hillbilly stereotypes, many of which he had been hearing since his West Virginia family moved to Akron a decade earlier.

Then, on a shelf of new library books, Eller saw Harry M. Caudill’s Night Comes to the Cumberlands: A Biography of a Depressed Area. “It was the first book I ever read straight through,” he said. “Stayed up all night.”

The next morning, Eller took the book to his professor, who echoed many historians’ criticisms of Caudill as too anecdotal and not “academic” enough. Night Comes to the Cumberlands became a foundation for Eller’s paper—and an inspiration for the rest of his career as an author, historian and Appalachian studies pioneer.

“Harry was writing about the relationship of people and land and how that land has been used over time,” said Eller, who later would

replace Caudill as a professor in the University of Kentucky’s history department.

“I wanted to write the history of the region from the perspective of someone from the region,” he said. “History has always been about telling people’s stories. In my case, it has always been countering those popular national images of the mountains.”

Eller was born in 1948 in Annapolis, Maryland, where his father was in the Navy. He and his younger five brothers and sisters grew up in Akron and near Beckley, West Virginia, where their grandfather had walked from his North Carolina farm at the turn of the 20th century to work in the coal mines.

Eller benefited from good public schools in Akron, where his father operated a barbershop. He earned an academic and basketball scholarship to the College of Wooster. But the year he started college, the rest of his family moved home to West Virginia—a place they had driven back to every other weekend, nine hours each way, the whole time they lived in Ohio.

That Southern history class inspired Eller to change his major from physical education to history. He taught school for a couple of years to earn money for graduate school and enrolled in the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. His professor and first writing mentor was George Tindall, who won the Lillian Smith Book Award in 1969 for The Emergence of the New South: 1913-1945

Eller met his second writing mentor at Duke University, where UNC history students could take classes. Larry Goodwin had been a writer for the Texas Observer before starting Duke’s oral history program. It attracted many Black and Appalachian students, whose people had been largely ignored by traditional history programs.

“Larry taught me to write from the gut and to express what I really felt and to tell stories,” Eller said. “I could identify with the stories my fellow students were telling

about political power, inequality, poverty and social justice. I learned so much.”

Eller’s first book, Miners, Millhands and Mountaineers: The Industrialization of the Appalachian South, won the 1982 Willis Weatherford Award from the Appalachian Studies Association and the 1983 Thomas Wolfe Literary Award from the Asheville Museum of History.

His second book, Uneven Ground: Appalachia Since 1945, is a history of how economic development, exploitation and government programs both helped and failed the region. It also won the Weatherford Award as well as the Southern Political Science Association’s V.O. Key Award for the best book about Southern politics.

“For me, history was my window into understanding why things were the way they were today,” he said. “History has to be re-interpreted by each generation in their own context and their own set of experiences. That’s the way we progress and move ahead.”

Eller also has written more than 70 scholarly articles. He served for 15 years as director of the University of Kentucky’s Appalachian Center and was a Rockefeller Foundation Scholar. He chaired the Governor’s Kentucky Appalachian Task Force, was the first chair of the Kentucky Appalachian Commission and was a member of the Sustainable Communities Task Force of President Bill Clinton’s Council on Sustainable Development. He has won many regional leadership and service awards and was inducted into the University of Kentucky Hall of Fame in 2020.

“Most of what I have written has been an effort to correct the historical perspective,” Eller said. “The mountains were never as isolated as some have suggested. Appalachians were never pure Scots-Irish; they were always a mixed-ancestry people, just as the nation as a whole. Appalachia is not the other America. It is, in fact, America.”

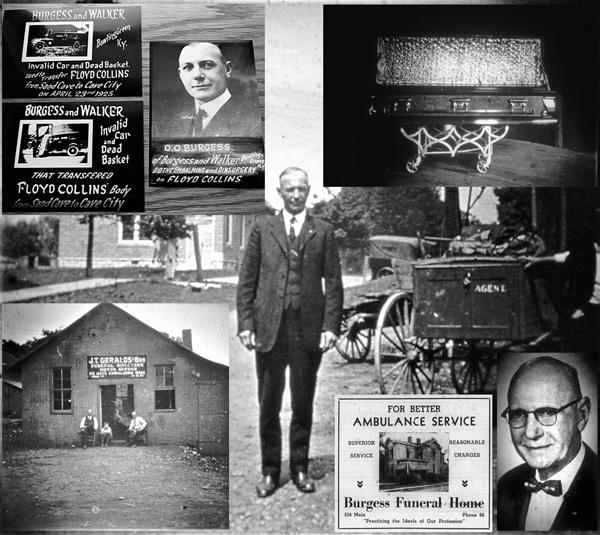

David Dick spent nearly two decades as a globetrotting CBS correspondent during the golden age of television news. Then he moved home to Bourbon County and launched several new careers.

Dick became a sheep farmer, the founder of two weekly newspapers and a University of Kentucky journalism professor and department head. He also published 14 books that attracted loyal readers across Kentucky and beyond.

Beginning with The View from Plum Lick in 1992, Dick wrote 11 books on his own and another three with his wife, Eulalie “Lalie” Dick. The topics ranged from his adventures covering wars in Latin America to his 17-year battle with prostate cancer.

Most of the books were about Dick’s beloved Kentucky, including Kentucky: A State of Mind (2005), Rivers of Kentucky (2001), Home Sweet Kentucky (1999), Let There Be Light: The Story of Rural Electrification in Kentucky (2008) and Jesse Stuart: The Heritage (2005).

“I think David’s contribution was his writing and language and how he applied it to the state … what his senses told him,” the late Carl West, editor of The (Frankfort) State Journal and founder of the Kentucky Book Fair, said after Dick died at age 80 on July 16, 2010. “He’ll be remembered for his literary effort.”

David Barrow Dick was born Feb. 18, 1930, in Cincinnati. His father, Samuel, a physician, died when he was 18 months old. His mother, Lucille, moved home with her three young children to Bourbon County, where five generations of her family had lived.

Dick, an Eagle Scout, graduated from North Middletown High School in 1948 and majored in English at the University of Kentucky. His studies were interrupted by United States Navy service during the Korean War. He completed a master’s degree in English literature at UK in 1964.

Before joining CBS News in 1966, Dick worked six years for WHAS radio and TV in Louisville. He was posted at CBS bureaus in Washington, D.C., Atlanta and Dallas, and spent a year as the Latin America bureau chief in Caracas,

Venezuela. He won an Emmy Award for his coverage of the 1972 assassination attempt on presidential candidate George Wallace, but he is perhaps best known for his coverage of the 1978 mass suicide of more than 900 cult followers of the Rev. Jim Jones in Guyana.

“We met one another in airports for a long time, and all we could think about was moving back to Kentucky,” Lalie Dick said. “It was the dream that kept us going.”

After retiring from CBS in 1985, Dick joined UK’s journalism faculty, which he led from 1987 to 1993. He was inducted into the Kentucky Journalism Hall of Fame in 1987 and UK’s Hall of Distinguished Alumni in 2000. Dick started newspapers in Montgomery and Bourbon counties that won many awards but didn’t survive long against established competitors. For 22 years, he wrote a column for Kentucky Living, the magazine of Kentucky’s rural electric cooperatives.

Dick was married to Rose Dick from 1953-1978. They had three daughters—Deborah, Catherine and Nell—and a son, Sam, a longtime broadcast journalist in Lexington. In 1978, David Dick married Lalie, a Revlon sales executive from Mississippi whose family had Bourbon County roots. The couple had a daughter, Ravy

Soon after returning to Kentucky, the Dicks took up residence on a farm one of his ancestors bought in 1799 and lived in a pre-1850 house built by a great-great-uncle. On several hundred acres along Plum Lick Road, the couple raised a large flock of sheep.

When Dick wrote his first book, the University Press of Kentucky told him it would take two years to publish, Lalie Dick said. He couldn’t wait that long. So, the couple started Plum Lick Publishing Inc., which produced most of their books. “We started putting cartons of books in cars and going places,” Lalie said.

The University Press published Dick’s historical novel, The Scourges of Heaven, in 1998.

“He was always in love with words and how they went together and how descriptive they were and what they meant. It was just in his DNA,” Lalie said. “He loved Kentucky with his whole being.”

"The Author Academy changed my life. With the opportunity provided, with the commitment of my mentor, I was able to establish the habits and minds et of a working author. The growth was enormous. I identify as a writer now."

-Cassie E. Brown, CCAA

Get the support you need to grow rapidly in your craft and prepare your work for publication. The Author Academy is open to adult writers of all genres and experience levels.

APPLICATIONS OPEN FEBRUARY 1 for more information visit: https://bit.ly/2025CCAA

kentucky monthly ’s annual writers’ showcase

FICTION

Nancy Gall-Clayton

Kacie Lawrence

Marie Mitchell and Mason Smith

OPENING

0F A NOVEL

Judith Hoover

Shirley Jones

Kacie Lawrence

Virginia Smith Logan NONFICTION

C. Ed Bryson

Vicki Easterly

Sheree Stewart Combs

Alex Berg

Timothy Kleiser

Mike Norris

Robert L. Penick

Catherine Perkins

Amy Le Ann

Richardson

George E. Robertson

Jack Stallins

Jessica Swafford

Eric Nance Woehler

Milkweeds ripple the face of the hill in a rash. If you claw deep, the dirt bleeds out a white powder. It is July now, and you know the next time you climb this hill you will be alone, and the hill will be either taller or shorter, and the sun –depending on the month –will be closer or farther away. If you were any type of religious, you’d take this to mean something or nothing. But you’re not. So you let the powder filter through your eyelashes and blink away what comes through. And thank God it comes through.

Jack Stallins

LOUISVILLE

Kacie Lawrence | KIRKSEY (CALLOWAY COUNTY)

Summer in the South commonly hangs on like a tick in a dogfight, and that summer would prove to be the hottest since 1934. Several major weather events had occurred that year, and by the first calendar day of fall, September 23, everyone and everything was over summer. The heatwave had been followed by drought, and in Kentucky, where livelihoods depended upon fertile fields, all anyone could talk about was the need for rain, until the body was found.

By Virginia Smith Logan | STANFORD

Budapest, Hungary

March 1944

In the weeks before my parents sent me away, I heard them arguing. Few words penetrated the wood between the second and third floors of our house in Budapest, but their tones seeped upward to invade the tiny bedroom I shared with Miklos and brought with them a palpable tension that twisted my stomach into knots. A discernible phrase occasionally echoed up the steep wooden stairway. I wanted to cover my ears to hide from the terror of their disagreement as I lay huddled on the corner of my thin mattress. Most of the words made no sense. What does a 4-year-old girl know of government and politics? Names like Sztójay and Lakatos meant nothing, though I shivered at the fear that saturated my mother’s ragged whispers.

By Judith Hoover | RUSSELLVILLE

December 1907

Both of her babies were down for their naps, and Clemente was at home with a bad cold that day, but the terrible tremor sent all four of them out the door headed toward the mines. Bessie grabbed little Orie, hitched up her skirt, and ran, repeating, “Oh my God, oh my God, oh my God,” all the way. Clemente sprinted ahead carrying Ivy, appealing all the while to “Madre di Dio.” Startled from their sleep, both children began to wail, a sound soon heard throughout the small town of Monongah, where every family had a miner missing behind the inferno of flames roaring from both mine entrances. Wives, mothers, sons and daughters appeared from all directions, held back only by the heat and smoke coming from these portals.

By Shirley Jones | BOWLING GREEN

Itiptoed across the front porch, shivering in my thin denim jacket, while balancing a heavy suitcase in one hand and a purse on my shoulder. Summer had lingered longer than usual this year, but tonight, the air held an autumn crispness that made my breath rise in soft billows. Above me, the full hunter’s moon bathed the sky in a warm glow that illuminated the gravel driveway leading from the house to the road—all the better for making my escape. As I reached the edge of the porch, I paused to scan the yard for wandering coyotes. A pack recently had moved into the area, driving Pa crazy with their constant howling. The thought of them roaming nearby made my heart race, fearing they might start yipping and wake Pa. I had come too far to have them foil my escape. Thankfully, they were still tonight.

By Marie Mitchell and Mason Smith | RICHMOND

Friday night fun in Central City, circa 1972, usually started with a high school basketball game and ended with Jackie and me driving around Muhlenberg County looking for adventure—whenever her mom let us borrow her 1968 Chevrolet Nova.

We often ended up at “the strip pits”—a large area that Peabody Coal Company had surface-mined and left looking like the radiation-blasted plains of Mars. But that was more entertaining than watching our equally dull classmates circle the drive-throughs in their parents’ cars, checking out who else was cruising around.

At first, there was nothing special about this one November night. After we reached the pits, we raced up and down the wide roadways designed for the giant, highcapacity dump trucks we called “ukes”—the yellow ones with the oversized 6-foot-high wheels.

It’s hard to believe, but driving at high speeds across the rough, gravely roads in total darkness between deep, water-filled, coal-spoil pits eventually lost its thrill. Before long, we grew bored—and low on gas. So, we started back toward town, planning to loop around Burger King a few times before our midnight curfew.

As we passed by a pit nicknamed Anchor Lake, so called because its shape resembled a ship’s anchor, I noticed something glowing in the water, or rather, under the water.

“What’s that?” I asked, pointing.

Jackie slowed from her normal 70 miles an hour—as fast as her mom’s Nova could manage on a level straightaway with a tailwind—to a sedate 45.

“Where?”

“In the lake.”

“Just a reflection, Artie,” she said dismissively.

“No,” I argued. “It’s a light. There’s no moon tonight.”

Jackie eased her foot off the gas, causing the car to sputter and slow from inertia and Muhlenberg County’s weird gravity anomalies. She leaned forward, gazing past me across the surface of the lake that now glittered with a soft yellow aura.

“Maybe someone missed a turn and plunged into the water?” Jackie guessed, suddenly slamming on the brakes and nearly flinging me into the windshield.

We climbed out into the nippy night. The Nova’s hot engine slowly ticked like a nearly wound-down grandfather clock. Nervously, we walked over to the pit. Kentucky’s Fish and Wildlife folks had forced Peabody Coal to stock the heavily polluted pits with fish, so an eyewatering stink of dead sea life filled the air.

As we stood there staring into the black water, the light shifted from yellow to green and then to rose.

“Whoa,” Jackie marveled, “that doesn’t look like submerged headlights.”

“It’s probably too late to rescue anybody, anyway,” I said. “Remember driver’s ed class—you only have about 60 seconds to get out.”

Our breath made puffs of condensation, and sleet stung my cheeks. Ice pellets that missed my face popped against my nylon windbreaker and baseball cap.

“Maybe the lights are from some sort of mining equipment,” Jackie suggested, pulling her parka more tightly around herself.

“Why would Peabody put a piece of equipment underwater?”

“Could be a testing device,” Jackie said. “Like the State sampling the water to see why all of their fish had died.”

That sounded reasonable at first. But why would an automatic sampling doohickey need lights? And how was it powered?

“More likely, someone’s pranking us,” I suggested.

We looked around for the jokester but saw only darkness.

“No one else is out here,” Jackie emphasized.

“Then what’s causing that?” I asked, motioning toward a huge, illuminated circle.

We remained mesmerized by the glowing water for a few more moments before my danger detector started to tingle.

“Let’s drive back to Riley’s Chevron and call the cops.”

“Right. Once they’ve had a laugh, they’ll make us take

breathalyzer tests. If Mom found out about that, she’d kill me.”

“You have a better idea?” I asked.

“We could toss rocks into the water and see what happens.”

“Seriously? Why don’t we just shoot at it?”

“Spoken like a true Kentuckian,” Jackie said. “But where’s your gun?”

So, six rocks later, including one near-boulder that Jackie heaved in with an underhanded toss, the pit’s water rippled. But the light remained stationary, quivering through the murky water.

“Well, that was disappointing,” Jackie lamented, a bit out of breath.

Just then, the object not only changed color again, but it nearly doubled in size while moving toward the surface—and us.

“Looks like we got its attention,” I said.

The light now formed a circle maybe 50 feet across, nearly filling the pit. The surrounding rocks reflected its flickering red color. The water’s surface started to boil as a massive, saucer-like metallic object surfaced.

“Let’s get out of here!” Jackie yelled as she raced to the car with me trailing behind.

Luckily, the Nova started right up.

Unlike most supernatural stories, though, that thing— whatever it was—didn’t follow us home. But as we peeled off, we witnessed a reddish-orange spacecraft streak into the sky from among the high walls of the mine, then vanish into the low clouds.

We drove in stunned silence to the police station without incident, Jackie gripping the wheel like a lifeline. We were too terrified to talk.

The cops called our parents to assure them we were okay. But here’s where things get wackier. Their clock read 2 a.m., while my watch indicated midnight. We’d lost two hours of time. Where did they go? What did we do? Neither of us could remember.

After the police had a laugh at our expense, they did

investigate but discovered nothing except our tire tracks and footprints. Case closed—for them.

But “the incident” and trying to account for the lost two hours after our sighting stressed us out. Plus, our classmates teased us mercilessly for months, which strained our friendship.

Neither of us returned to the strip pits again. By graduation, Jackie and I had drifted apart.

In college, I’d planned to major in business administration, maybe even go for an MBA, but my interests changed after that night. Instead, I became a college English professor. I read, researched and lectured on many topics, mostly dealing with paranormal phenomena. But I never managed to solve the mystery surrounding our eerie encounter, which radically changed my career trajectory.

Years later, our Alumni News magazine featured Jackie, who’d become one of the first women ordained into the Episcopal priesthood.

Jackie, a priest? Who’d have guessed? She’d excelled at math and science and was planning to study engineering, maybe join NASA and become an astronaut. How did she get from aeronautics to the priesthood?

Probably the same way I got from business into an English classroom—by wanting to make sense of our uncharted experience.

Our encounter was weird in the Old English sense of wyrd—that is, having great occult power, i.e. the power to control “fate, destiny or doom.”

Those lights have never been reported since that night, at least not in Muhlenberg County, although I’m sure teenagers still go looking for them. In fact, most nights before bed, I step outside and study the sky, seeking answers—especially on cold, cloudy November nights.

I’d be willing to bet that after she recites the evening office from The Book of Common Prayer, Jackie steps outside and does the same.

By Kacie Lawrence | KIRKSEY (CALLOWAY COUNTY)

McDougal Cemetery sits on a hill in the woods 10 miles outside of Murray. The single-lane road that one must take to get there is cut into the hill and is known to often wash out after a hard storm.

There are many ghosts here for Ellie. She remembers coming here with her parents as a child. Once, she had enjoyed how the cows in the field would come and watch them when they were there, standing in a row side by side chewing their cud like people eating popcorn in a movie theater. Behind them the land would roll for miles.

Now, the cows are gone, and there is a house that blocks the view. Ellie wonders if the people inside are watching her visit her family. She wonders if they are standing around chewing like the cows did.

There was a time that her family came to the cemetery about once a month. Mama would clean the graves of those they knew, pulling weeds, sometimes putting out silk flowers, but mostly, she’d just sit quietly. Daddy seemed unable to stand and watch, so he’d walk around. Ellie would follow, and together, they would make their way toward the back of the cemetery, where the graves became smaller, almost fading into the woods. Daddy would read out the names as he walked, noting whether or not they were relatives of someone she knew.

Now, Ellie walks through, noting some of the newer stones where a newly paved drive bends between a few old oaks. There are several covered in sprays of flowers, some with wind chimes, and two with stone benches for those who must come to visit long enough to need a place to sit. Now, in her 30s, Ellie recognizes many of the names much

more than she did as a child.

Ellie decides to wander around before visiting her family’s plot, the way she remembers doing when she was young. It doesn’t take long to reach the edge of the woods, where the stones are so worn by time she must wonder if it’s a grave or just a rock stuck in the mud. Some obviously were once smoother stones, but many are conglomerate red rock, reminding her of the gravel driveway that leads to the single-wide trailer she grew up in. There are no silk flowers, no benches or ornaments in this part of the graveyard. Ellie wonders when was the last time someone pulled weeds here.

“Which grave is the girl’s?” Ellie always asked Daddy as they wandered.

Daddy didn’t have to ask what girl. He just smiled and shrugged his shoulders.

“Probably one of the unmarked ones in the back. Those are the oldest graves,” he said.

Ellie thought so, too.

“Tell me the story again,” she would say.

It was the story she asked for every time they came to McDougal.

Daddy always made sure they were far enough away that Mama couldn’t hear them. Mama didn’t like Daddy’s ghost stories, especially when he told them at the cemetery, which she said was disrespectful.

“Back a long time ago, when your grandma’s grandmama was about your age, there was a church here,” he began.

He told her it was where a pavilion with the wooden picnic tables now covered in chipping white paint sat.

“When they’d get out of church, the grown folks would

talk, and the kids would play. Annie—that’s your greatgreat-GREAT-grandmama’s name—started playing with a girl about her size. The girl didn’t talk; she was real quiet like, but they ran around for a bit. Then Annie’s daddy told her to get in the back of the wagon ’cause it was time to go home. So, Annie jumped into the back of the wagon, and the little girl jumped up into the wagon too.”

“Did her mama and daddy not see the little girl or know she was there?” Ellie always asked, even though she’d heard the story more than once.

“Nah,” Daddy said. “Anyway, they started to pull the wagon away from the church, and Annie turned to tell her mama and daddy they’d picked up the little hitchhiker, but for some reason, they didn’t hear her, and they kept driving. When Annie turned around again to look at her new friend, she was shocked to see that the little girl no longer had a head.”

With this, her daddy always turned and looked at Ellie, his eyes going wide.

“Annie was too scared to talk or scream, but then, the little girl’s body just jumped off the wagon and waved goodbye. They say ever’ now and then, when people leave this place, they look in the mirror and see a headless little girl in the backseat.”

Ellie thinks of the story now as she looks at the nameless old graves. She wonders if there is really a small headless child underneath any of the stones here. The thought sends a chill up her spine and makes her nervously laugh out loud. She can’t help but peek over at the new house to see if she’s been caught—a woman laughing in a cemetery, alone.

While walking back toward the small area where a few stones carry her maiden name, Ellie spots a small white grave with a lamb on top of the stone, and she remembers another time here.

Daddy stopped in front of a small, rounded stone. He got down and tried to read the writing.

“This one here is a little kid’s grave. Do you know how I know?” he asked her.

She didn't. The letters and dates on the white stone had been impossible to make out.

“This little lamb on the top,” he said as he patted the lamb as if it were real.

Behind him, Ellie repeated his gesture and softly patted the lamb before following.

“You know, I think that might be Annie’s sister’s grave,” he said. “She died young. Her name was Americus. That’s a weird one, huh?”

Ellie looks now, many years later, but the name is even more faded and even less legible.

She continues to the spot where her mother used to pull the weeds around a small gray block. It’s much smaller than the ones around it, but the words are still clear.

Ellie sits down on her knees and pulls the tall grass that has grown up around the small stone and the ones around it, which have become more numerous with time. Before she goes, she makes sure to pat the small lamb yard ornament she once insisted on bringing to her brother’s grave, years ago, and she leaves a fresh bouquet of red silk flowers for Daddy.

She checks her rearview mirror over and over before she makes it home.

By Nancy Gall-Clayton | JEFFERSONVILLE, INDIANA

Nancy lived in Louisville from 1969-2009

Why did he have to stand right there, right in the doorway tapping his foot? Didn’t he realize we were in the middle of a poetry reading? Couldn’t it wait, whatever it was?

The instant the intent young woman finished reading her prize-winning poem about a child buried in a stillticking Mickey Mouse watch, the man stepped out of the doorway and into the room.

“Does anyone here have a blue Subaru parked out front?” he asked.

There was no response until a full minute later when I flung my white wool scarf around my neck, grabbed my coat, and pushed my way out of the crowded room.

“I apologize,” I said, trying to walk in step with him, “but I’ve lost my keys. They may be locked in the car.”

“Oh, great!” he exclaimed in dismay, lengthening his strides as if he were racing to reach the car before the sun disappeared into the horizon. “Do you belong to the auto club?”

“No,” I said, stopping abruptly, forcing him to turn back and face me. As he did so, I took one of his hands into both of mine. “And neither should you,” I added. “Auto clubs, why, auto clubs are …”

My voice drifted off as I tenderly stroked his hand and recalled my Brownie troop sitting cross-legged in a circle as we listened to our leader describe how to make name tags from macaroni and tree bark. In my vision, each Brownie in the circle was gradually replaced by one of those sleekly curved, oversized sedans from the 1940s.

“This auto club will now come to order,” honked the head auto, prompting the others to stop flapping their hoods.

“What?” the man asked me, withdrawing his hand.

“What did you say about auto clubs?”

“Just this,” I replied. “Don’t you think life is too short to spend any of it fretting?”

“But you’re blocking my car, and I’m late for a meeting!”

“Of?”

“Of?” he repeated the word as if I had addressed him in Swahili.

“A meeting of what?”

“Oh,” he exclaimed, understanding. “The Daniel Boone Club.”

“My point exactly,” I said. “How far would Daniel Boone have gotten if he had fretted?”

“Interesting,” he admitted after a pause.

Just then, we arrived at the Subaru. Living only blocks from the site of the poetry reading and not owning a car, I had walked over. My purpose in joining the man had been to teach him about tranquility and spontaneity, both of which he obviously lacked.

“You think that car is blue?” I teased.

“What color do you think it is?” he asked, a slow smile forming under his tidy mustache.

“Turquoise,” I said without hesitation.

“You’re obviously color blind,” he advised.

“Or perhaps you are,” I countered. “Say, why not skip that Daniel Boone thing and buy me a cup of coffee?” I tilted my head toward a rectangle of yellow light across the street.

“Well …” He sounded unsure.

“Haven’t you ever done anything on impulse?” I asked.

“I run a high school computer lab. What kind of example would that be?”

It turned out he hadn’t done anything on impulse during his first 27 years, but he began that night when he playfully touched my nose after Ellie, proprietor of the Irish Hill Café, brought us bowls of steaming mint-carrot soup and glasses of dark beer. When she shooed us out a couple hours later, we walked to my place and sat on opposite sides of a rickety kitchen table drinking coffee until the sun came up.

We called in sick and proceeded to the hall of justice, where we stood witness for a couple we’d never met, and they did the same for us. Later, he bought me a pearl ring, and I gave him huge jars of finger paint in primary colors. After supper, we packed my books and clothes into cardboard boxes and threw everything else in a dumpster. I moved into his apartment, of course.

We were good for each other, he and I. To my surprise, he cooked rather well and enjoyed it. I kept our home tidy, and after we found an ancient sewing machine at a yard sale, festive pillows and curtains brightened the place, often in shades of blue.

Most evenings, we walked in the neighborhood holding

hands, sometimes stealing a kiss, and once taking home a scrawny, ownerless puppy. We kept a game of chess going at all times, went to a lot of movies, and read The Wind in the Willows to one another. Our gentle lovemaking was like two clouds gracefully gliding through one another.

My husband soon resigned from the Daniel Boone Club and began attending poetry readings with me. Our lives seemed interwoven perfectly when, just days after our third wedding anniversary, he told me that he was considering an unsolicited job offer from one of the largest corporations in town.

“But you’ll have to wear suits,” I exclaimed miserably. “And navy-blue socks. You’ll have to work late and wear a beeper and start eating meat again and read computer magazines.”

“I already read computer magazines,” he reminded me.

“But you won’t have time to read anything else,” I said.

“It won’t be that bad,” he insisted.

“It will,” I predicted.

The theme at the next poetry reading was “our universe.” An earnest young man was halfway through a sonnet laden with alliteration and double meanings when I noticed a fretful woman standing in the doorway. She wore a navy-blue suit and had long red fingernails, the kind that are glued on, and she was unconsciously tapping them against the wall in a jittery rhythm.

“It’s all right,” I whispered, leaning over to kiss my sweet husband goodbye.

“Does anyone here have a blue Subaru parked out front?” the woman in the doorway asked.

Nudging him, missing him already but knowing that our destinies must diverge, I whispered, “Honey, that’s your cue.”

By Sheree Stewart Combs | PARIS

July 1967

Grandma Hettie and I settle in on the porch to break green beans. Neighbor women stop to visit, grab beans from the pan, and work alongside us. The rhythmic creak of the swing’s chains and the grind of the glider’s metal rungs create a cacophony to accompany the work. We swat sweat bees and dodge the dive bombs of dirt daubers. Dogs pant in the shade of the porch. Their thick tongues drip raindrops of slobber. Haunch-thin cats sway past them, tails raised, to rub against our sticky legs. Sweat glistens on the faces of the women and pools inside my shirt collar.

The mountains echo the ladies’ voices as I listen to familiar stories and the latest gossip. Sometimes, a racy joke sends them into peals of laughter, and I catch a glimpse of the young girls they once were. Girls who climbed mountains, rocked baby dolls and splashed in the creek, like me. I’ve seen them young in faded black-and-white photos but found it hard to reconcile the pictures with the women they have metamorphosed into. Their faces carry a more hallowed beauty in lines etched from years of hoeing corn in the sun, worried about their men working dangerous jobs in the mines or logging in the woods. When their faces bloom in glee, youth kindles old fires in their eyes. They are fierce, bent by hard times, but never broken. A shy, awkward girl, I yearn to be like them.

Grandma and I linger on the porch after night falls. I curl up in the glider. She sits in a chair so near I can touch her. Her white hair is twisted into a bun above the nape of her neck. The wildroot cream oil she rubs into it each morning perfumes the air when the wind rustles the leaves in the apple trees. My brown hair hangs like a curtain down my back. She’s 60, and I’ll soon be 12.

Raindrops plop onto the porch roof as Grandma weaves tapestries of her memories and wraps them around me, her first-born grandchild. She tells me of creeks she waded, babies she tended, her mother’s smile and Grandpa Obie’s grin. Her voice grows husky when she talks of the man with pools of brown in his eyes. She met him in 1927 in a boarding house, where she cooked meals for miners. A man of the deep earth and ancient mountains to whom coal dust often clung. I sense her mouth widen into a grin, eyes glaze with old desire, as she whispers, “Your grandpa sure was pretty.”

In a voice soft as snow, she speaks of burying their firstborn in a Caretta, West Virginia, coal camp cemetery, sorrow and longing for the baby trapped in her voice 40 years later. “He looked perfect, but he was blue and so cold,” she says. “I held him against me to try to warm him. He never drew a breath.” Her breath catches in her throat.

Grandma entrusted me to carry her stories into a future she’d never see. I know this now, but on those nights, I couldn’t imagine a world without her in it. She’s been gone since 1979, but I see us there, our hearts swollen in contentment. Generations of our people, conjured back to life by her remembrances, dance around us in the shadows.

By Vicki Easterly | FRANKFORT

It was 1962. We were in first grade, and it was Christmastime.

On Monday, Miss Moberley printed our names on slips of paper and placed them in a green basket. She walked the aisles between the desks, pausing at each desk for us to draw a piece of paper. Finally, she announced, “OK, children, you can look.”

I drew Tammy Baxter’s name. Tammy was a blue-eyed girl who wore her long black hair in braids with ribbons on the ends. I knew just what I would buy Tammy—a box of sparkly silver bows!

That night, I couldn’t sleep. I wondered who had drawn my name and what they would buy me. I imagined the baby doll with real hair I had seen at Woolworth’s or a colorful tea set. How could I wait until Friday, the day of the party?

Tuesday morning at recess, Miss Moberly asked me to stay behind after the others had filed into the gymnasium. When she began by calling me “sweetie,” I knew I wasn’t in trouble, but what came out of her mouth next was worse. Billy Joe Hill had drawn my name, she told me with pity. Billy Joe—the poorest kid in class, the boy without milk money, the boy with no hat or gloves. I understood what it meant to have Billy Joe Hill draw my name. My present might be something old, or I might not get a gift at all.

On Wednesday morning, Billy Joe rushed up to me, his ears stinging from the cold. His icy hands cupped my ear as he whispered a secret. “I got you a present, and it’s red!” he told me, barely able to contain his excitement. He ran to his desk, sat with his dimpled chin in his hands, and grinned impishly. I told Miss Moberly the secret about the red

present. With an air of condolence, she warned me not to be disappointed if it was something used. I felt like crying.

Every day, the girls whispered with joy about their gifts. I wasn’t feeling much joy. The boys teased Billy Joe mercilessly, especially since he forgot his lunch money every day that week, but he just kept on smiling.

Friday came. Miss Moberly served us Hawaiian Punch and cookies. She invited my mother to come and help, perhaps to soften my disappointment. Wild-eyed from punch and sugar sprinkles, we wiggled in our chairs. At last, Miss Moberly took one gift from under the tree.

“When I call your name, you may come and get your present. Debbie, Jimmy …” Then I heard my name. I trudged to the front and took my present from Miss Moberly. She smiled at me compassionately. The girls were squealing with delight. I waited until last to open mine. With dread, I peeled back the used paper until my present was visible.

It was red! A red porcelain poodle with a feathered hat that twisted off! Inside was perfume, and it was not used! I twisted off the hat and applied a generous dab behind each ear. It smelled like sugar plums! It was the best Christmas gift ever!