8 minute read

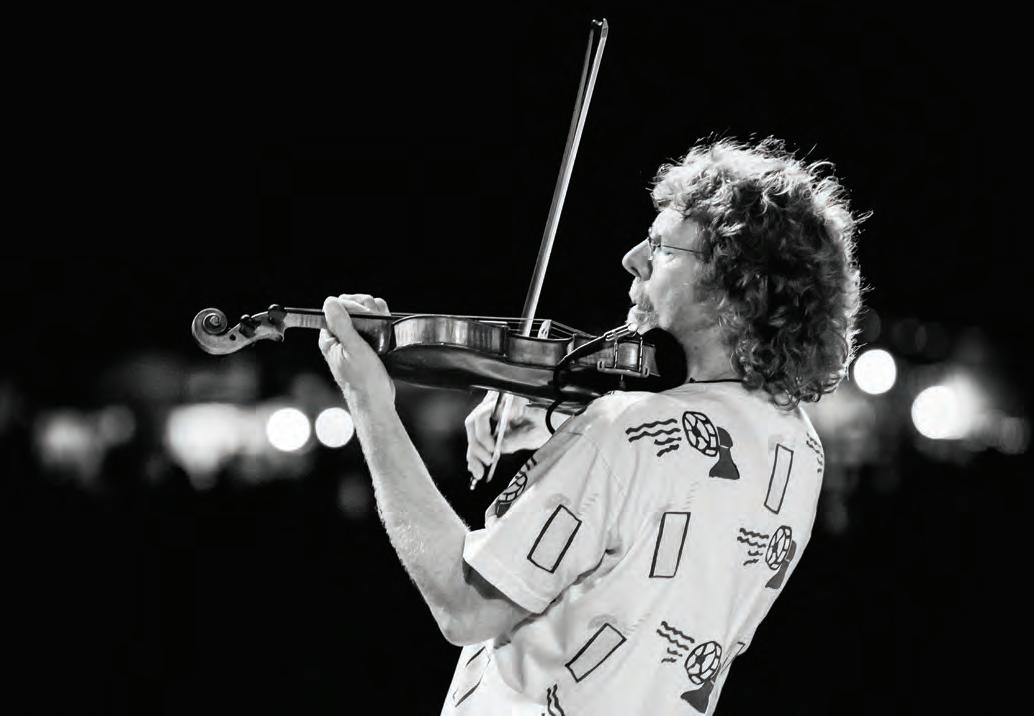

The Father of Newgrass

As the accolades roll in, Sam Bush keeps on making new music while he sets the stage for a new generation of bluegrass stars

BY PAM WINDSOR

It’s been a quiet summer for Sam Bush, who has missed getting out and touring in the wake of the coronavirus pandemic. The multi-Grammy-winning mandolin and fiddle player, known for his highenergy live shows, is a big draw on the festival circuit. He’s been a top act at the Telluride Bluegrass Festival in Colorado for nearly five decades and was looking forward to events in his native Kentucky.

“We missed seeing the people at ROMP in Owensboro, and this was going to be the first year we played at Bourbon & Beyond in Louisville,” he says. “We’re looking forward to the day we can get back out and see our friends again.”

He’s stayed busy with music projects at home and is now preparing to celebrate the induction of his New Grass Revival band into the International Bluegrass Hall of Fame. (The virtual induction is set for Oct. 1 during the IBMA Bluegrass Music Awards.) For Bush, who is known as the “Father of Newgrass,” the honor is both gratifying and humbling.

“It’s amazing to me to think that we, the New Grass Revival, have been put in the same company as the people we were directly influenced by,” he says. “It’s almost indescribable, because I didn’t know if it would happen in my lifetime.”

New Grass Revival got its start in 1971 and for the next 18 years helped guide the progressive bluegrass movement.

“When we started New Grass Revival, we didn’t think we were starting Newgrass,” Bush explains. “We thought we were reviving a style that the Osborne Brothers and Jim & Jesse, the Country Gentlemen and The Dillards already had going. People ask, ‘Did you all consciously try to change bluegrass music?’ No, we just played it like we felt it.”

The group used bluegrass instruments to incorporate sounds from rock and roll, rhythm and blues, and reggae.

“When I first heard the Bob Marley and the Wailers album Natty Dread,” Bush recalls, “what first attracted me was Bob’s staccato rhythm guitar playing. It reminded me very much of Bill Monroe’s chop, what mandolin players call the rhythm chop. It’s one of the things I still love most on the mandolin, playing rhythm.”

In addition to introducing new sounds, New Grass Revival songs featured lyrics that differed from the usual topics found in bluegrass.

“We weren’t writing about my little cabin home on the hill or memories of Mother and Dad, as in the traditions of bluegrass,” Bush says. “We were writing about modern-day subjects. And that, too, would make a change in the music.”

Original members of NGR included Bush on mandolin, Courtney Johnson on banjo, Ebo Walker on bass, and Curtis Burch on guitar. There were some changes in between, but by 1981, the lineup of New Grass Revival consisted of Bush, lead vocalist and bass player John Cowan, guitarist Pat Flynn, and banjo virtuoso Bela Fleck.

Now a close friend, Fleck considered Bush a musical hero at the time and was thrilled to join the groundbreaking group.

Photos courtesy of Sam Bush. SHELLY SWANGER PHOTOGRAPHY

“There was a great balance of highly arranged and highly improved music in the band’s repertoire,” Fleck says, “but the thing that I believe made it really stand out was the sheer intensity that the group played with. Sam used to riff on Ike and Tina Turner saying, ‘We never do anything nice and easy!’ But it was quite true. Even a Bill Monroe romantic waltz became an opportunity for emotional power.”

While Bush is credited with taking bluegrass in a new direction, his love of music is grounded in the traditional roots of the genre and an appreciation for the legendary artists who created it.

“I grew up on a tobacco and cattle farm outside Bowling Green,” Bush says. “I was very fortunate to grow up in a part of Kentucky where, if my dad would climb up on the roof and adjust the antenna, we could get the Nashville television stations, specifically WSM-TV with the Grand Ole Opry. That’s where my interest in bluegrass and country music came from. I got really turned on to Bill Monroe, Flatt & Scruggs and others.”

At the age of 11, Bush watched a young Ricky Skaggs play the mandolin on one of those TV shows and was inspired to play music. His dad, a musician, had both a mandolin and a fiddle, so Bush picked up the mandolin first, then later became proficient on the fiddle. He soon began making annual trips to Weiser, Idaho, to compete in the National Oldtime Fiddlers’ Contest.

“I came in fifth the first year, and then when I was 15, 16, and 17, I won. So, I was called the national junior champion,” Bush says.

In high school, he began learning other instruments. “I was just a sponge. I loved every kind of music.”

During his senior year, he began taking violin lessons from a professor at Western Kentucky University. He planned to attend college but got an offer from a band in Louisville to play guitar five nights a week and jumped at the chance. (In May of 2019, Bush received an honorary Doctorate of Fine Arts from WKU.)

That band was called Bluegrass Alliance. Soon after Bush took the job, guitarist Tony Rice joined the group, and Bush switched to playing the mandolin.

“I got to go back to the mandolin, which has always been my first love,” he says. “And out of that band came New Grass Revival, when four of us quit to form our own group.”

For nearly two decades, New Grass Revival pushed forward with an innovative style that created new trends in music. Fleck describes the band’s approach.

“I have always been most interested in the music that is on edge, between distinct musical idioms,” he says. “I’d even say that that is where growth and progress tend to reside—not dead in the center, but teetering on the edge of a form. New Grass Revival jumped off the cliff completely, and that’s exactly where it should have been.”

The group released a series of albums under different labels. One of its highest-charting songs was “Callin’ Baton Rouge,” later recorded by Garth Brooks.

New Grass Revival disbanded in 1989, and Bush went on to perform with a number of other artists.

“It’s been said through the years that, if you know how to play

We’ve missed you!

bluegrass, you can play anything,” Bush says. “And for the most part, that’s true because it’s led me to blend in with so many people. I’ve gotten to play jazz/rock with Bill Evans and Bela Fleck and the Flecktones. [He spent a year with Fleck’s group years after New Grass Revival.] I’ve played on John Prine and Guy Clark records, and they are two of the greatest songwriters I’ve ever known. I was in Emmylou Harris’ band for five years, then did a stint with Lyle Lovett.”

He later formed his Sam Bush Band, in which he is both musician and lead singer.

Bush has been honored numerous times for his accomplishments in music, including IBMA Mandolin Player of the Year Awards, and in 2009, he received the American Music Association’s Lifetime Achievement Award for Instrumentalist. He also was the subject of a 2015 documentary called Revival: The Sam Bush Story.

As the IBMA marks his contributions to bluegrass with the upcoming Hall of Fame Induction, Bush says the future of the genre is in capable hands.

“You have a lot of young people, some playing in the tradition of Bill Monroe, many trying to play like J.D. Crowe and The New South, and some playing like New Grass Revival,” he says. “The good part is musicianship has grown so much, and it’s not a good ole boy’s club anymore. There are some great ladies playing bluegrass and giving it a new thought pattern and musical approach. One of my favorites, Sierra Hull, is one of the greatest mandolin players you’ll ever hear. So, it’s in good hands because young musicians are taking it to new places.”

Hull, a Tennessee native who began playing mandolin at the age of 8, points to Bush as one of her strongest influences.

“Sam is so revered,” she says. “I learned early on he was someone I should pay attention to and not only because of his own music, but he’s also played on so many other people’s albums. Alison Krauss was one of my biggest heroes as a kid, and Sam’s on the very first Alison album I got called Forget About It.”

Hull first met Bush when she was 9.

“He sat down and jammed with me for well over an hour,” she remembers. “I think that says a lot about him and the influence somebody has at an early age.”

She’s also grateful to him for paving the way for others to play their own style of music.

“Without people like Sam having pushed the boundaries, I don’t really know where someone like myself would be as a musician,” Hull says. “I think his courage and vision to make new music has trickled down to the next crop of musicians.”

Bush is still creating new music and says his greatest joy comes in collaborating with others, whether with members of his own band or other musicians.

“I love getting to do this,” he says. “I hope I get to keep doing it for a long time. Each and every day is a blessing.” Q

NOW OPEN Accepting Reservations

Patio open overlooking the Ohio River

ADHERING TO CDC + KY STATE GUIDELINES FOR SAFE DINING EXPERIENCE

Live at the Hive ENTERTAINMENT

101 W. Riverside Drive Augusta, KY 41002 beehiveaugustatavern.com 606.756.2137